Islands as legible geographies: perceiving the islandness of Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland)

Ilisimatusarfik/University of Greenland, Greenland

Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada

Island Dynamics, Denmark

agrydehoj@islanddynamics.org

Abstract

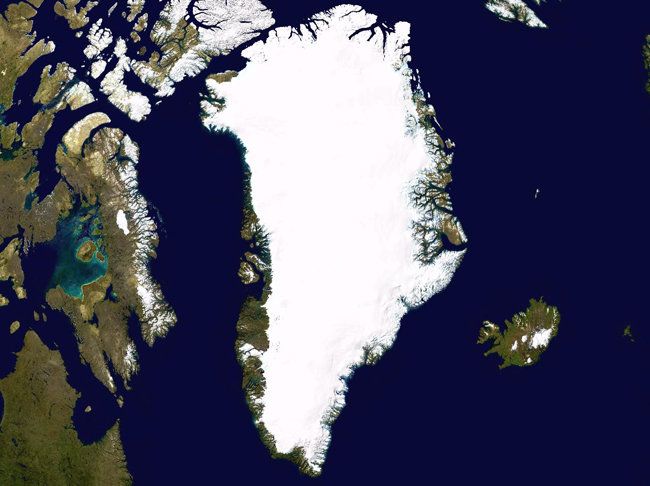

Despite considerable research within the field of island studies, no consensus has yet been reached as to what it is that makes islands special. Around the world, islands and archipelagos are shaped by diverse spatialities and relationalities that make it difficult to identify clear general characteristics of islandness. This paper argues that one such ‘active ingredient’ of islandness, which is present across many forms of island spatiality, is the idea that islands are ‘legible geographies’: spaces of heightened conceptualisability, spaces that are exceptionally easy to imagine as places. The paper uses the case of Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland) to show how island geographical legibility has influenced a territory’s cultural and political development over time, even though Kalaallit Nunaat is such a large island that it can never be experienced as an island but can only be perceived as an island from a satellite or cartographic perspective. I ultimately argue that islandness can have significant effects on a place’s development but that it can be difficult to isolate these effects from other factors that may themselves have been influenced by islandness.

Keywords

archipelagos, Greenland, islands, islandness, Kalaallit Nunaat, legible geographies

Introduction: What makes islands special?

The field of island studies has never succeeded in coming to a consensus regarding this question. This may in part be due to the field’s at-times uncomfortable bringing together of diverse disciplines: Tropes of islandness may differ widely between, for example, literature studies and economic geography. It may also relate to the field’s bringing together of researchers from diverse regions of the world: Characteristic elements of islandness in, for example, Oceania may not be shared in the Mediterranean, Atlantic Canada, the Persian Gulf, East Asia, the South Atlantic, and the Swahili Coast. Furthermore, the emergence of urban island studies, extending an island studies approach to ‘island cities’ such as Guangzhou, Mombasa, and Mumbai (Su, 2017; Steyn, 2015; Swaminathan, 2014), must surely dash any easy association between islands and ‘insularity’ or peripherality. It is thus possible – and indeed, preferable – to recognise the diversity of island spatialities (Grydehøj, 2017).

In this paper, however, I discuss one common – though still not universal – attribute of islands, one ‘active ingredient’ of islandness that, in interplay with other factors, produces a special island effect across many forms of island spatiality. Specifically, islands represent ‘legible geographies’, spaces of heightened conceptualisability, spaces that are exceptionally easy to imagine as places. This paper will explore how islands function as legible geographies through the case of Kalaallit Nunaat (in English, Greenland), a subnational island jurisdiction (SNIJ) of Denmark.

Imagining islands

Much has been written on the role of islands within the human imagination (Ronström, 2013; Baldacchino, 2012; Gillis, 2007; King, 1993, p. 14). It has also been widely recognised in the literature that part of what makes islands so attractive is their illusory knowability and comprehensibility (Royle, 2014, p. 155; Lowenthal, 2007, p. 210; Grydehøj & Kelman, 2016). The unambiguous water borders that characterise islands allow us to trace them in our minds. This is equally the case for an oceanic island such as Tristan da Cunha (Schällibaum, 2017), for a near-shore island such as Saaremaa (Cottrell, 2017), and for islands in the city with abundant fixed links such as Hong Kong (Leung et al., 2017) – though less so for island cities that have merged with the mainland through land reclamation, such as Macau (Sheng et al., 2017).

As Lynch (1960, p. 47) notes in his landmark study of how people navigate in and experience the city, water boundaries – such as those produced by a river or the sea – represent ‘edge elements’ that serve as “important organizing features, particularly in the role of holding together generalized areas.” That is, hard boundaries help us make sense of our environment. Significantly, this role of water borders is only partly experiential. In Lynchian terms, we may see a ‘landmark’, follow a ‘path’, move within a ‘district’, or enter into a ‘node’ (Lynch, 1960, pp. 47-48) – all categories that help us create and imagine the ‘contents’ of a city. In contrast, ‘edge elements’ such as walls and water serve to exclude the outside world, to draw mental boundaries around these contents. For Lynch, all else being equal, the cities in which people feel most comfortable are those cities that are most ‘imageable’. Vale (2018) notes, following Lynch, that islandness can produce a form of ‘territorial legibility’.

As Riquet (2016, p. 152) suggests, the ‘monarch-of-all-I-survey’ trope in island fiction frequently mistakes the ability to see an entire island with the ability to know it. The ability to circumambulate a small island (to walk all around its coastline) grants a feeling of comfort and security, a feeling of knowing a place – even if you really do not. We believe we can know where an island begins and ends.

The Holy Island of Lindisfarne off the coast of Northeast England can possess far more symbolic significance than could a mainland heritage site of similar type and size. Lindisfarne’s islandness infuses it with meaning and allows it to comprehensively occupy its own space: We presume to know not only where the island ends but also where the mainland fails to extend. This is not to say that only island places can hold symbolic significance; it is simply to say that, all else being equal, islandness eases this process. This is not merely a Western phenomenon; islands play a special role in some non-Western cultures as well (e.g. Suwa, 2007; Luo & Grydehøj, 2017).

It is easy to be dismissive of such acts of mental islanding, yet to recognise that we are attracted to island spaces through a quirk of human psychology is not to deny that this quirk of human psychology has real-world consequences. A constant negotiation is underway between island reality and island representation, without the one being more ‘true’ than the other (Hong, 2017; Ronström, 2013). The ways in which we imagine and represent islands have a wide range of impacts. As shall be discussed using the case of Kalaallit Nunaat below, this is true even in contexts in which a place’s islandness can only be perceived in an abstract and indirect manner, that is, for example, when an island is so large in size as to render circumambulation or visible perception of islandness impossible.

How Kalaallit Nunaat became an island

Kalaallit Nunaat is famously the world’s largest island in terms of land area (2,166,086 km²). In fact, however, Kalaallit Nunaat is an archipelago composed of the world’s largest island (with the exception of Australia) ringed by a great many small islands. Nevertheless, not all of the territory’s 56,000 residents regard it as an island or an archipelago. People who do not live on Kalaallit Nunaat are much more likely to regard it as an island than people who do live there. The questions must thus be raised: Who should be the arbiter of islandness? Do foreigners and, in some cases, societal elites have the right to proclaim a place an island on another people’s behalf? Can there ever be any point to or justification for trying to convince people that they do indeed live on an island? We shall sidestep these thorny questions for the time being and instead consider how some people’s tendency to read Kalaallit Nunaat as an island has had real world effects. (It is necessary to note that my own positioning may be a limiting factor in my analysis, inasmuch as I live in Denmark, undertake periodic work in Kalaallit Nunaat, and am American – rather than Danish or Kalaallit – by birth and upbringing.)

Islands are perhaps most frequently defined as ‘pieces of land surrounded by water’ (e.g. Island, n.d.), yet different cultures have different conceptions regarding islands. There is, for example, a shared Northern European conception of islandness (Ronström, 2009), with the British, Irish, German, Dutch, Nordic cultures, and so on possessing generally compatible thoughts and words concerning islands. It is thus, for example, that the English ‘island’ and the Danish ‘ø’ are more or less exact synonyms. In these cultures, an association has developed between islands and remoteness. A piece of land may need to be surrounded by water to be an island, but in practice, many people will only consider a piece of land to be a ‘real’ island if it is somehow distant to or peripheral from the centre of cultural, political, or economic power. Thus, the English island city of Portsmouth is not generally considered to be an island, yet the Isle of Wight across the Solent strait is most definitely an island. Similarly, although residents of Copenhagen (the capital and largest city in Denmark) might reluctantly admit that some of the city’s small constituent islands are islands or might joke that the larger island of Amager – across the harbour from the city centre – is an island, most Danes do not truly think of these places as islands. Nor is this simply a matter of these islands being connected to other places by bridges: After all, few Danes would contest that the bridged islands of Langeland and Møn are indeed islands. In the Western imagination, islands tend to be wild or rural, not densely urbanised. Alternatively, we can more easily imagine a place as an island if we imagine it to be marginalised: As Hayward (2018) shows, many residents of Canvey Island in England’s Thames Estuary have embraced a sense of urbanised – even heavy industry – islandness, in part on account of Canvey’s place at the margins of a global city in a changing Britain. The sense of marginality or isolation as crucial to islandness can be foregrounded in debates regarding not just transport infrastructure such as bridges (Baldacchino, 2007; Leung et al., 2017) but also communications infrastructure (Brophy, 2017).

The same is not true in Chinese culture, where islands were traditionally associated with remoteness but where the word dao (岛) can today be applied with ease to both central and peripheral pieces of land surrounded by water. The reasons for these kinds of differences run deep. As Owe Ronström (2009) has pointed out, the primary Germanic words for ‘island’ have shared Indo-European roots that link islands to water; in contrast, the Chinese dao is etymologically linked with mountains (Luo & Grydehøj, 2017). Despite such differences, a great many cultures around the world have developed ideas of islands as special and distinctive.

Furthermore, around the world, there is a tendency for people who live on relatively large islands or islands with large populations not to regard their own places as islands but to regard other similar places as islands. Thus, for example, like the Kalaallit (Greenlandic Inuit), many British, Taiwanese, Madagascans, Japanese, and Indonesians do not truly feel that they live islands, yet they may be comfortable with labelling these other places as islands. Islandness is thus relational: An island is only an island if it is brought into relation with a mainland (including perhaps a larger island that serves as a mainland).

Similarly, people can mentally create archipelagos by constructing power relationships between multiple islands. This is not to say that a ‘piece of land surrounded by water’ may not be an island from a purely technical standpoint, only that, for islandness to make a social difference, someone needs to first think of a place as an island in relation to somewhere else. One complex example of this has recently been described by Lee et al. (2017), who show how the archipelagic relationality of Taiwan’s Lieyu island is undergoing change relative to shifting power relations in Lieyu’s interactions with Kinmen Archipelago, mainland Taiwan, and the Chinese island city of Xiamen.

This brings us back to Kalaallit Nunaat. When we regard Kalaallit Nunaat as an island, we may be doing so from a Northern European, Danish perspective rather than from an Inuit, Kalaallit perspective. It may be that conceptions of islandness differ between the Kalaallit and the Danes as well as that Kalaallit and Danes posit different forms of relationality between Kalaallit Nunaat and Denmark.

Nor should we necessarily find this surprising. The prehistoric peoples and later the Inuit themselves who arrived in Kalaallit Nunaat from the northwest and worked their way down and around the coast had long been travelling across a series of islands of various sizes, traversing sea and mountain and bog and ice. For them, islands would be normal; islands were the only thing they knew. Indeed, Kalaallit Nunaat may have been experienced as a continent, an anti-island – an utterly impassable expanse, relative even to the enormous neighbouring Umingmak Nuna (Ellesmere Island) and Qikiqtaaluk (Baffin Island). (For analyses of the prehistoric migratory processes that resulted in Greenland’s present-day Inuit populations, see e.g. D’Andrea et al., 2011; Friesen & Arnold, 2008; Gulløv & McGhee, 2006)

Norse settlers began arriving in Kalaallit Nunaat in 985 CE (Buckland et al., 2009; Gulløv, 2008). Unlike the earlier and later settlers from present-day Canada, the Norse were coming from a situation of Icelandic-Norwegian relationality and would have possessed a Norwegian cultural understanding of island-mainland relationships. Yet the Norse – with their settlement limited to regions in the island’s south and southwest – would not have realised that Kalaallit Nunaat was an island. Kalaallit Nunaat would have been someplace else – certainly peripheral to and remote from the centres of culture in Iceland and mainland Scandinavia, but too large and unmanagable to be conceptually ‘islanded’.

Thus, for the vast majority of the 4500 years or so since Kalaallit Nunaat was first settled, it was not an ‘island’ in any meaningful sense. Kalaallit Nunaat is only ‘the world’s largest island’ today because we know that it is an island, a point of geographical fact that was only conclusively proven by Robert Peary’s expedition to the north of the island in 1891. Today, Kalaallit Nunaat – which is still connected by ice to other landmasses at some times of the year – truly is an island on the map, a place that we recognise as an island from a cartographic or satellite perspective. The island’s ‘place on the map’ may itself be significant inasmuch as Kalaallit Nunaat is granted oversized prominence in the common Mercator projection of the globe (Battersby & Montello, 2009, p. 276).

The importance of Kalaallit Nunaat’s island status

Kalaallit Nunaat’s status as an island has, however, become important over the past century. Perhaps most obviously, Kalaallit Nunaat’s legible geography has made it easier for Danes to ‘territorialise’ the island, to think of this enormous, distant place as somehow belonging to and with Denmark.

Islands such as Kalaallit Nunaat may be peripheral and remote in the Western imagination, but they are not just peripheral and remote. They are also places that are exceptionally open to feelings of distant ownership, to expressions of possession (Lowenthal, 2007). The Danish ‘love for Greenland’ (Grydehøj, 2016) is partially rooted in the fact that Kalaallit Nunaat is, as an island, exceptionally loveable. Would Denmark have been interested in and capable of legally transforming Kalaallit Nunaat from a colony into a high-level municipality in 1953 had Kalaallit Nunaat simply been a chunk of the North American mainland, something resembling Labrador or even the entire Labrador Peninsula? It is no coincidence that, as the era of decolonisation began in 1950s, it was the most populous and the mainland territories that became independent first. Island sovereignty came long afterward in most of the Caribbean and the Pacific – and for many islands and archipelagos, it never came at all (Baldacchino, 2010).

Yet Kalaallit Nunaat’s islandness, its self-containment, has arguably had advantages for Kalaallit as well. Around the world, islands are generally said to possess close and cohesive communities. It may be theorised that this is in part because the remoteness, peripherality, and isolation with which islands are associated are attributes that encourage close communities: Residents of remote islands rely upon and are familiar with their fellow community members in a different way than are people who live in mainland cities. Similarly, in the past, transport difficulties meant that many islands developed cultures that diverged over time from those of other islands and distant mainlands. These attributes are to some extent true for remote and peripheral communities on the mainland as well though: For instance, villages in the Andes or the Himalayas cannot be said to be any less isolated from centres of cultural, economic, and political power than can comparable island communities.

Denmark may not have been inclined to hold onto Kalaallit Nunaat were Kalaallit Nunaat not an island, but equally it may be that Kalaallit would not feel like Kalaallit per se were Kalaallit Nunaat not an island. It is Kalaallit Nunaat’s islandness – its iconic outline, its deceptively straightforward view as seen from the satellite eye – that makes it a single, coherent space. Such a simplified vision of Kalaallit Nunaat allows our minds to momentarily forget that the northeast portion of the territory and the entirety of the island’s interior are unpopulated as well as that none of its numerous towns and settlements are connected by road. The vast majority of Kalaallit Nunaat’s land area is currently covered by ice year round. My own experiences of discussing the island with Kalaallit suggest that virtually all narratives of Kalallit territoriality and identity are coastal; the interior of the island has little practical and emotional meaning to most Kalaallit (though it is of course possible that this will change if a warming climate leads to an increasingly accessible island interior). Nevertheless, few would think to draw a map of Kalaallit Nunaat that only included the dots of coastline where people actually live. Kalaallit Nunaat would not exist in the mind as Kalaallit Nunaat were it not an island. It is Kalaallit Nunaat’s island cohesion and comprehensibility, its legibility, that provides an identity for Kalaallit as Kalaallit, rather than simply as this category’s constituent ethnic groups (Kalaallit, Tunumiit, and Inughuit), important though these continued cultural distinctions may be.

How else can we explain the unique sense of nationalism in Kalaallit Nunaat relative to other Inuit territories? One need only glance across Baffin Bay to see the alternative. The predominantly Inuit territory of Nunavut (Canada’s largest province by land area) would perhaps be in a stronger cultural and political position if it consisted solely of islands, rather than consisting of islands and vast tracts of sparsely populated mainland territory. Nunavut’s obscure borders – its mix of island, mainland, and sea – defy conception. Lacking ‘natural’ borders, Nunavut is an illegible space, and the place is more difficult to imagine as territory. Efforts to create a sense of a distinctive Nunavummiut identity face greater geographical barriers than is the case for the creation of a Kalaallit identity. This does not mean that Nunavummiut identity does not exist; it just means that Kalaallit identity possesses geographical advantages. It is thus perhaps unsurprising that Nunavut’s political leadership is focused not on the creation of an independent Nunavut but instead on the strengthening of pan-Inuit and pan-Indigenous politics across the Arctic (Jacobsen, 2017).

It is both because islands are easy for people on the mainland to imagine possessing and because islands are easy for islanders to imagine as self-contained that there exists an odd tension in the way in which islandness affects politics: Islands are simultaneously more likely to be regarded as distinctive places than are similar units of continental land (Holmén, 2017) but are also more likely to still be legally linked to a larger mainland state than are places with similarly distinctive place identities, simply because formal decolonisation occurred in mainland regions earlier than in island regions (Baldacchino 2010). This is the paradox not just of disputed islands such as Taiwan but also of places such as New Caledonia, Anguilla, Niue, Åland – and Kalaallit Nunaat.

Kalaallit Nunaat is an island because people imagine it as an island, whether they are aware of it or not.

Archipelago-building processes in Kalaallit Nunaat

The above discussion has sought to show that people – both insiders and outsiders, both Kalaallit and Danes – sometimes find it convenient or attractive to imagine Kalaallit Nunaat as an island. This may clash, however, with lived experience of Kalaallit Nunaat. That is, although Kalaallit Nunaat is often imagined as a single, unitary island, it is not frequently experienced as a single, cohesive space. This is hardly surprisingly, given the large size of Kalaallit Nunaat’s main island; the presence of numerous towns and settlements on small, offshore islands; and the fact that none of the archipelago’s towns and settlements are connected to one another by fixed links (roads, bridges, tunnels, etc.). Strong centre-periphery dynamics exist within Kalaallit Nunaat (Grydehøj, 2014). Indeed, the complex relationships between the smallest of these urban areas, the larger towns, and the capital ‘city’ of Nuuk (population 17,316) suggest the workings of archipelago-building processes (e.g. Lee et al., 2017; Hayward, 2012a,b) – the construction of a network of island-island, island-mainland, and island-sea power relationships that cause people to group certain islands together with one another. Archipelago building is a selective process, including some places and excluding others. The towns and settlements of south, west, and north Kalaallit Nunaat are conceptually linked with those of culturally and geographically distant east Kalaallit Nunaat and not linked with those of culturally and geographically closer Qikiqtaaluk in Nunavut.

Analysis and conclusion

Despite all of the above, it is important to reiterate that not all Kalaallit regard themselves as living on an island or in an archipelago. This reinforces the wider argument that although some effects associated with island and archipelago status may depend upon people recognising or conceiving of their own place as an island or an island within an archipelago (e.g. Pigou-Dennis & Grydehøj, 2014), other effects may occur independent of island or archipelago self-perception.

Such an analysis, however, risks overstating the importance of islandness. As we have seen, it is difficult to disentangle the specific effects of island status from cultural, historical, political, and even scholarly factors. The simplest explanation for why Kalaallit Nunaat towns such as Qaqortoq, Nuuk, Ilulissat, Upernavik, and Tasiilaq are grouped with one another but not with those of Inuit Canada hinges upon Kalaallit Nunaat’s and Nunavut’s divergent histories of colonisation and decolonisation (see Loukacheva, 2007). Even if these colonial processes were and are influenced by Kalaallit Nunaat’s island status, this influence cannot be identified as the sole or even dominant reason why any particular outcome has occurred. In the words of Baldacchino (2004, p. 278), “islandness is an intervening variable that does not determine, but contours and conditions physical and social events in distinct, and distinctly relevant, ways.” Our search to identify what it is that makes islands special should not drive us to believe that a place is only an island; at most, a place can be an island as well as many other things. It is thus that we can say that Kalaallit Nunaat is an island as well as an archipelago – but also that it is a colonised territory, has an Arctic environment, is part of the Inuit cultural region, has a welfare state, has strong transport connections with Europe but not with North America, and so on.

Islandness can be an important factor in a place’s cultural, political, environmental, economic, and social development over time, but it is never the only factor. By considering the case of Kalaallit Nunaat, I have sought to highlight some ways in which the legible geographies of islands can prove significant, perhaps most obviously by strengthening feelings of distinction and possession. Although I have been approaching these common ways of perceiving islands as a ‘quirk of human psychology’, this does not make the effects of this ‘islanding’ process unreal. The ways in which people frequently and throughout history have conceptually isolated and territorialised easy-to-read island geographies have indeed made an impact on the ways in which both islanders and mainlanders live their lives.

References

- Baldacchino, G. (2012). The lure of the island: a spatial analysis of power relations. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 1(2), 55-62.

- Baldacchino, G. (2010). Island enclaves: offshoring strategies, creative governance, and subnational island jurisdictions. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Baldacchino, G. (2007). Fixed links and the engagement of islandness: reviewing the impact of the Confederation Bridge. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 51(3), 323-336.

- Baldacchino, G. (2004). The coming of age of island studies. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 95(3), 272-283.

- Battersby, S.E., & Montello, D.R. (2009). Area estimation of world regions and the projection of the global-scale cognitive map. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99(2), 273-291.

- Brophy, J.E. (2017). Reiterating the boundary: community discourse in light of proposed technological change on Vinalhaven Island, Maine, USA. Island Studies Journal, 12(1), 187-206.

- Buckland, P.C., Edwards, K.J., Panagiotakopulu, E., & Schofield, J.E. (2009). Palaeoecological and historical evidence for manuring and irrigation at Garðar (Igaliku), Norse Eastern Settlement, Greenland. The Holocene, 19(1), 105-116.

- Cottrell, J.R. (2017). Island community: identity formulation via acceptance through the environment in Saaremaa, Estonia. Island Studies Journal, 12(1), 169-186.

- D’Andrea, W.J., Huang, Y., Fritz, S.C., & Anderson, N.J. (2011). Abrupt Holocene climate change as an important factor for human migration in West Greenland. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences, 108(24), 9765-9769.

- Friesen, T.M., & Arnold, C.D. (2008). The timing of the Thule migration: new dates from the western Canadian Arctic. American Antiquity, 73(3), 527-538.

- Gillis, J.R. (2007). Island sojourns. Geographical Review, 97(2), 274-287.

- Grydehøj, A. (2017). A future of island studies. Island Studies Journal, 12(1), 3-16.

- Grydehøj, A. (2016). Navigating the binaries of island independence and dependence in Greenland: decolonisation, political culture, and strategic services. Political Geography, 55, 102-112.

- Grydehoj, A. (2014). Constructing a centre on the periphery: urbanization and urban design in the island city of Nuuk, Greenland. Island Studies Journal, 9(2), 205-226.

- Grydehøj, A., & Kelman, I. (2016). Island smart eco-cities: innovation, secessionary enclaves, and the selling of sustainability. Urban Island Studies, 2, 1-24.

- Gulløv, H.C. (2008). The nature of contact between native Greenlanders and Norse. Journal of the North Atlantic, 1(1), 16-24.

- Gulløv, H.C., & McGhee, R. (2006). Did Bering Strait people initiate the Thule migration?. Alaska Journal of Anthropology, 4(1-2), 54-63.

- Hayward, P. (2018). Salt marsh synthesis: local politics, local identity perception and autonomy initiatives on Canvey Island (Essex, UK). Island Studies Journal, 13(1), 223-234.

- Hayward, P. (2012a). Aquapelagos and aquapelagic assemblages. Shima, 6(1), 1-11.

- Hayward, P. (2012b). The constitution of assemblages and the aquapelagality of Haida Gwaii. Shima, 6(2), 1-14.

- Holmén, J. (2017). Changing mental maps of the Baltic Sea and Mediterranean regions. Journal of Cultural Geography, 35(2), 230-250.

- Hong, G. (2017). Locating Zhuhai between land and sea: a relational production of Zhuhai, China, as an island city. Island Studies Journal, 12(2), 7-24.

- Island (n.d.) Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/island

- Jacobsen, M. (2017). Nunavuts nye regeringsleder: Jeg har altid set op til Grønland. Sermitsiaq, 18 November. http://sermitsiaq.ag/nunavuts-nye-regeringsleder-altid-set-groenland

- King, R. (1993), The geographical fascination of islands. In D.G. Lockhart, D. Drakakis-Smith, & J. A. Schembri (Eds.) The Development Process in Small Island States (pp. 13-37). London: Routledge.

- Lee, S.H., Huang, W.H., & Grydehøj, A. (2017). Relational geography of a border island: local development and compensatory destruction on Lieyu, Taiwan. Island Studies Journal, 12(2), 97-112.

- Leung, A., Tanko, M., Burke, M., & Shui, C. S. (2017). Bridges, tunnels, and ferries: connectivity, transport, and the future of Hong Kong’s outlying islands. Island Studies Journal, 12(2), 61-82.

- Lowenthal, D. (2007). Islands, lovers, and others. Geographical Review, 97(2), 202-229.

- Loukacheva, N. (2007). The Arctic promise: legal and political autonomy of Greenland and Nunavut. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Luo, B., & Grydehøj, A. (2017). Sacred islands and island symbolism in Ancient and Imperial China: an exercise in decolonial island studies. Island Studies Journal, 12(2), 25-44.

- Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. Cambridge, MA & London: MIT Press.

- Pigou-Dennis, E., & Grydehøj, A. (2014). Accidental and ideal island cities: islanding processes and urban design in Belize City and the urban archipelagos of Europe. Island Studies Journal, 9(2), 259-276.

- Riquet, J. (2016). Islands erased by snow and ice: approaching the spatial philosophy of cold water island imaginaries. Island Studies Journal, 11(1), 145-160.

- Ronström, O. (2013). Finding their place: islands as locus and focus. Cultural Geographies, 20(2), 153-165

- Ronström, O. (2009). Island words, island worlds: the origins and meanings of words for ‘islands’ in north-west Europe. Island Studies Journal, 4(2), 163-182.

- Royle, S. A. (2014). Islands: nature and culture. London: Reaktion.

- Schällibaum, O. (2017). Narrating islands: fragmentation and totality as figures of thought in Raoul Schrott’s work. Island Studies Journal, 12(2), 291-302.

- Sheng, N., Tang, U.W., & Grydehøj, A. (2017). Urban morphology and urban fragmentation in Macau, China: island city development in the Pearl River Delta megacity region. Island Studies Journal, 12(2), 199-112.

- Steyn, G. (2015). The impacts of islandness on the urbanism and architecture of Mombasa. Urban Island Studies, 1, 55-80.

- Su, P. (2017). The floating community of Muslims in the island city of Guangzhou. Island Studies Journal, 12(2), 83-96.

- Suwa, J.I. (2007). The space of Shima. Shima, 1(1), 6-14.

- Swaminathan, R. (2014). The epistemology of a sea view: mindscapes of space, power and value in Mumbai. Island Studies Journal, 9(2), 277-277.

- Vale, C. (2018). Understanding island spatiality through co-visibility: the construction of islands as legible territories – a case study of the Azores. Shima, 12(1), 79-98.