Takarajima: A Treasured Island: Exogeneity, folkloric identity and local branding

Southern Cross University, Lismore, Australia phayward2010@gmail.com

Kagoshima University, Kagoshima, Australia

Abstract

This article examines the manner in which local identity can be constructed on small islands from the selective prioritisation and elaboration of exogenous elements that become localised by this process and can subsequently function as a brand within contemporary tourism markets. The particular analysis of identity motifs on Takarajima island that we expound examines aspects of the relationships between folklore and contemporary media and references contemporary debates concerning archaeology’s interface with folklore and popular culture in the context of (non-scientific) ‘treasure hunting’.

Keywords

Takarajima, Exogeneity, Folklore, Identity, Local branding, Captain Kidd, Treasure hunting

Introduction

Takarajima is the southernmost island of the sparsely populated Tokara group of islands that stretches between the Amami islands, to the south, and Satsunan islands, to the north. The population of the island has declined significantly over the last sixty years from a peak of around 560 in the mid-1950s and now numbers around 115 on an island of about 7 square kilometres.1 In this article we consider aspects of the culture and folklore of the island, the prominence accorded to exogenous elements in this and the manner in which local identity – or, at least, the local identity that islanders currently chose to represent to outsiders – manifests itself in the early 21st Century. Much research on island cultures is premised, to varying extents, on perceived indigeneity, specific local character and/or and localising enterprises as the defining aspects of local identity. At its worst, this can lead to a romanticism and/or exoticisation of ‘island difference’. This chapter provides an alternative perspective by examining a contemporary island society – and its various folkloric inscriptions – that emphasises exogeneity as a defining attribute of its history. While Takarajima is not unique in this regard, such an emphases on exogenous elements and events as (interrelated) historical/folkloric ‘pivots’ and contemporary identity markers merits discussion and merits the island’s placement in a spectrum of identities that is often perceived within a more restricted bandwidth.

Along with folklore, archaeology offers an important perspective on island histories and, fittingly in this regard, discussion of the relationship between folklore and archaeology (as separate but intersecting evidential accounts of the past) has been a minor current in the latter discipline over the last two decades (as evidenced by the contributors to Gazin-Schwatrz and Holtorf’s anthology Archaeology and Folklore, first published in 1999 and re-published in a second edition in 2012). John Collis’s contribution to the anthology is particularly pertinent to the subject of this chapter through its consideration of the relationship between archaeology and popular culture. One of his main concerns is to consider the manner in which “popular beliefs, including folklore” have entered into archaeology “at a number of different levels”; variously forming the basis of paradigms, providing “parallel interpretations” or, most troublingly for him, providing “ideas which are completely antithetic” to the discipline (1999: 126). Whilst acknowledging that archaeologists “cannot pretend we are some sort of neutral arbiter without our own cultural baggage and without our own ideology” (ibid); he noted that reconciliation between the folkloric (and other popular cultural fields) and archaeology is not always possible; before asserting that “dialogue with those holding different views and approaches can enrich our presentations of the past” (ibid). Underlying his discussion is an unease about the impact of archaeology on the folkloric/popular histories of communities, especially when archaeological evidence and interpretation function to debunk or diminish prominent local beliefs in past events and/or myths of origin. Pointing to the manner in which contemporary popular culture often tends to selectively interpret and represent aspects of folklore in order to provide representations of the past (which, in turn create a new contemporary folkloric ‘layer’ with a sometimes disjunctive fit with its predecessors); Collis identifies that:

The distinction between folklore and popular culture thus becomes muddled. Those transmitting the oral tradition may not be aware of the origin of what they are assuming to be some sort of accepted truth (ibid: 128).

Collis’s ruminations are relevant for our discussion with regard to two ‘muddles’ concerning Takarajima. The first is the interrelation of local folklore and popular culture and the infusion of the former by elements of the latter. The second is more oblique and concerns the problematic absence of unambiguous archaeological evidence to support various folkloric accounts of local history and – simultaneously – the prominence of hidden, lost and/or concealed material artifacts as key elements of the identity narrative of Takarajima’s contemporary society. The majority of our discussions in this chapter weave their way through the relationship between artifacts and the artifice of folkloric memory re-inscribed, re-interpreted and reconstituted by popular culture and made manifest in contemporary treasure hunting practices (despite the lack of any archaeological evidence to encourage the activity).

Locale, history and lore

While archaeological evidence suggests that the present-day island of Tokara was inhabited around 5000 years ago during the Jomon (Neolithic) period,2 when sea levels were lower and the land area of the Tokara and Amami islands was more extensive; it is unclear whether habitation of the islands has been continuous since then. The earliest written records of any detail are those compiled by the Satsuma officials who were sent to the region during the Shimazu clan’s expansion from Kyushu southwards in the mid-late 1500s but reference to the population of Takarajima date back to around 700 AD. This date is significant as the local population currently has a distinct account, ‘folkloric perception’ and/or ‘myth of origins’ that identifies the current population as descended from the Heike (also known as Taira) clan of main-island Japanese samurai who fled south through Kyushu and the Tokara archipelago3 in the late 1100s after being defeated by a rival clan in a naval battle in 1185. The historical veracity of their being such a clan and of their being defeated is well established. What is open to question however is the particular account that identifies that they relocated to Takarajima (and/or perhaps, some other of the Tokara, Amami and Okinawa islands). The reason for this uncertainty is that information is taken from a famous Japanese saga Heike Monogatari (‘The Tale of the Heike’). This saga is not so much a measured historical account as an impressionistic narrative that may – at least in the version that exists today – have been serially embellished and adapted; since prior to its first written versions it comprised an oral tale that was disseminated and historically perpetuated by itinerant biwa (Japanese lute) playing bards known as biwa hōshi. The written version most commonly used as a basis for modern reproductions of the text was compiled in 1371, close to 200 years after the actual events occurred.

Given that archaeological and historical evidence suggests that the northern Ryukyu region (comprising the present day aggregations of Okinawa, Amami and Tokara) shared a distinct and viable culture – known as Ryukyu Jomon – in the period between c5000 BC and AD 900 (Ito, 2005) and that an active network of inter-island trading of kamuiyaki stoneware was evident in the period between 1000 and 1300 AD (Pearson, 2007); it seems likely that Takarajima (of all the Tokora islands) might well have been inhabited at the time of the alleged Heike arrival, since it has fresh water, areas of relatively flat arable land and abundant marine food resources close to shore. This raises various questions. Even if we take the arrival of the Heike on Takarajima in the late 1100s as a historical fact, several issues and ambiguities occur. The first is that if the island was inhabited, what happened to the populace when the Heike arrived? Were they entirely displaced? Or killed? These scenarios are possible but somewhat unlikely as the samurai were, by definition, samurai (rather than farmers or fishers) and would presumably have needed some support (or at least training and knowledge transfer) to survive in their new location. So, again, speculating, it is likely that under scrutiny the local ‘foundation myth’ might at least need modification to identify the origin of the present-day community and cultural identity of Takara as that of a combination of Heike and pre-existent Takarajimans. (And here we are putting ‘on hold’ the question of whether any Heike did in fact arrive and/or whether it may have only been a few stragglers) (Fig. 1).

Whatever the nature of the origins of the present-day Takarajiman community, its minimal contemporary inter-connection with Amami is striking. Linguistically – and with specific regard to dialect patterns that have progressively become less marked over the last seventy years - there is a (relatively) steady north/south language shift in Japan from the Yaeyama islands, through Okinawa and Kyushu up to the ‘standard’ Japanese of Honshu. In this model, the boundary between the Amami and the Kagoshima/Satsuma dialect zones is located between Amami Oshima and Takarajima. This is highly defined barrier with little linguistic interchange across the divide. This boundary is also a cultural one. The distinct style of folk song known as shima uta that is prevalent in Amami, for instance, is not present in Takarajima. Indeed contemporary Takarajimans actively seek to distance themselves from their immediate southerly neighbours in favour of identification with mainland Japan, an affinity that they understand as premised on their Heike ancestry. Indeed, there is evidence that this boundary is socially ‘policed’ in various ways. During fieldwork in 2009, for instance, we identified one Takarajiman (whose mother was from Amami) who could play Amami shima uta music. In conversation, he told us that he was discouraged from playing shima uta in public or, even, in private. Similarly, the daughter of a woman who was originally from Amami who relocated to marry a Takarajima male told us that her mother was heavily discouraged from visiting her home island during her life, despite the fact she could see it from high points on Takarajima, a situation which caused her considerable grief.

During our fieldwork we were unable to identify any noticeable differences between Takarajiman and standard Japanese speech. Interested to explore whether this was a contemporary phenomenon we talked with older islanders, inquiring as to what local dialect forms they may have recalled from their youth. The older residents were consistent in their responses that they grew up speaking standard Japanese and did not recall that there had ever been any distinct dialect on the island. There was also a further twist to this. When asked whether they thought main island Japanese would perceive them to have a distinct accent, two older islanders replied in the affirmative. One identified that their accent would be perceived as similar to refined Kyoto Japanese and another identified that it would sound like Miyazaki dialect (again reflecting the islanders’ belief in their Heike origins). Discussions with teachers at the local school (on placement from Kyushu) were illuminating in that they declared that they could not identify any deviation from standard Japanese in their school students’ speech.

In terms of other cultural forms, while older islanders identified that Takarajima did possess a small corpus of local songs in their youth, they related that, with one exception, these were now forgotten. Interestingly, they expressed no particular regret over the loss of this repertoire nor recalled there having been any efforts to preserve it. The one exception to this expired repertoire was a song that two older male islanders agreed to try and recall and eventually performed for us entitled Tokara Kannonshu.

The song’s lyrics and title refer to one of the island’s principal cultural heritage icons, the Kannon. During earlier periods of greater population, the Kannon and other local deities were celebrated in a number of shrines across the island. Faced with a declining population in the 1970s, four statuary representations of local gods (Amaterasu-oomi-no-kami – the Shinto Sun Goddess and three syncretic Shinto-Buddhist incarnations of earlier Shinto spirits – the Kazamoto-gongen, Megami-gongen and Hachiman-gongen) were relocated to and secured in a location (known as Chinju-daimyoujin4) near the main village. In the years immediately following their relocation there were regular celebrations at this location led by Shinto priests but these have now ceased and people are only encouraged to visit at special occasions in July and November. Unlike the aforementioned deities, the Kannon has remained prominent on the island and separately housed. The Kannon is a Buddhist entity that embodies and symbolises compassion. It arrived in Japan and South East Asia as Buddhism diffused from India in the 6th Century and became popular throughout Japan in the Asuka Era (538–710). While the entity was originally male, many later representations are of a female figure. The Kannon is materialised in three Kannonsama (statues) on Takarajima (see figures below) (Figs. 2 and 3).

The three statues represent separate historical moments. The first, wooden artefact (Fig. 4) is now aged, decayed and very much a relic of the belief culture of a formerly more extensive island population. Local folklore describes that the statue once had either green jewels or gold inlays as eyes, which it lost (one at a time) in an unspecified period. Through a process of association, these have been understood to have originated from one of two sources, either from treasure brought by the Heike, then concealed and now ‘lost’; or else from European buccaneers (discussed further below). The second stone artefact is showing signs of surface decay but is still part of a used shrine while the third is situated in a bright, fresh and well-maintained setting. The trio represents a continuity of local beliefs but of the three, the depleted materiality of the wooden figure suggests a tantalising link to an earlier, more vibrant cultural moment that is open to a variety of present-day interpretations. The lyrics of the sole surviving local folk song, Tokara Kannonshu, written from the point of view of a male protagonist, inscribe the Kannon within island life as a sacred/magical deity capable of providing those who honour her with a spouse in its opening stanzas5 and then go on to reflect on the sadness experienced by those islanders who have to leave to work elsewhere,6 and also caution against romantic involvements with non-Takarajimans.7 In this song – and its title – the Kannon stands for and symbolises the home island, its heritage and history.

Igirisu encounter

The Tokuguwa shogunate that ruled Japan between 1603 and 1868, introduced a policy known as Sakoku (literally ‘locked country’) that prohibited trade, travel and related contact between Japanese residents and foreigners (with the exception of a small group of highly regulated contacts with Ryukyuan, Korean, Chinese and Dutch traders through prescribed ports). This policy remained in place until decisively broken by the incursion of a fleet of US ships led by Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853. As might be expected from a country located on a chain of islands in the north-western Pacific, Japan’s exclusionist policy was tested by a series of incursions by western ships in the 18th Century, which were peacefully rebuffed. Tensions over Japanese refusals to trade rose in the early 19th Century, with military clashes between Russian and Japanese forces occurring in the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin in 1804–1805 and again in 1811; and with an armed raid on Nagasaki to obtain supplies by the British frigate Phaeton in 1808. Another conflict arose on Takarajima in July 1824, when a ship, identified by an official report8 as a British vessel of around 200 tons, arrived offshore. Seven crewmembers came ashore in a rowing boat, were met by members of the Satsuma garrison and communicated by sign language that they wished to obtain cattle for provisions. When the garrison members rejected their request, the ship’s party withdrew only to return later in an attempt to seize cattle by force. A skirmish resulted in which one of the ship’s crew was killed. This incident took place on a slope now known as Ingirisu Saka (‘English Hill’) and is commemorated by a local monument (Fig. 5). When reports of this incident arrived in the Japanese Imperial Court they were the trigger for an intensification of Japanese resistance to incursion under the provisions of the Ikokusen Uchiharairei edict of 1825, which instructed Japanese forces to repel all unauthorized foreign vessels by force.

There is also a question concerning the identity of the mariners involved. Their identification as English appears to arise from two factors: (a) that one of the Japanese recognised the language of the sailors as English [which is interesting since it is unlikely that any islanders or the low-level guards stationed on the island would have had any familiarity with English at this time] and (b) that at least one of the mariners wore a red military jacket of the type worn by the British army at the time. The latter point is however far from conclusive. If the ship was a whaler or sealer it would have been unlikely to have had British army personnel as part of its crew. Similarly, if it were a naval vessel it would be unlikely to have ‘red-coats’ on board unless a particular military campaign was underway. Given that there were no uniform codes on commercial ships such as whalers and sealers it is possible – if somewhat unlikely – that a member of the ship’s company would have worn an army jacket that they had somehow acquired. Another option is that, particularly given their propensity to wear a veritable bricolage of fancy clothing, the individual(s) concerned were members of privateer/pirate crews. The violent action against the islanders doesn’t give any significant clues however since both whaling/sealing and pirate ships commonly used force against communities they encountered, especially if they didn’t get their own way. The ambiguity about the status and action of the ‘English’ leads to convenient cross-association (and confusion) with a third important exogenous cultural association with the island: that of Captain William Kidd.

Just Kidding? Pirate myths and island identity

William Kidd (1645–1701) was a Scottish maritime adventurer who engaged in both privateering (British-endorsed piracy against enemy ships) and conventional (i.e. ‘freelance’) piracy during the 1680s and 1690s in the Atlantic and Indian oceans. The latter part of his career, prior to his arrest by British authorities in Boston in 1699, is the best known. Following a sustained period in the Indian Ocean, ranging between Madagascar and (present-day) Indonesia, he returned to the Caribbean and then the New England coast of North America, where he attempted to counter piracy charges and disperse some of his booty. Upon his arrest, his captor, Lord Richard Bellomont, British Governor of Massachusetts, New Hampshire and New York, became convinced that a portion of Kidd’s booty had been hidden and made various attempts to track it down. While an amount was deposited by Kidd on Gardiners Island (off the eastern tip of Long Island), this was rapidly located by Bellomont, but he and others remained convinced that Kidd had hidden substantial amounts elsewhere.

This belief has been inflated and embellished in a process of folkloric development with a variety of possible treasure locations being identified in New England, Nova Scotia, the Caribbean and further flung locations.9 The earliest identification of Takarajima as the site of Kidd’s treasure appears to have been in 1936 in the monthly US magazine in article written by Harold T. Wilkins (identified in the article as author of the book Modern Buried Treasure HuntersModern Mechanix [1934]). The article contains a description of the island on which Kidd’s treasure is buried, a map of an island10 and a vague location for it. In one of the more interesting asides in Wilkins’ lurid account of his discovery of the map he notes that the map “might well have formed the original of the delightful treasure island chart which R.L.S [i.e. Robert Louis Stevenson] and his young relative Lloyd Osborne, drew and faked for Treasure Island! ‘ (1936: 157). The language here is significant, the “might well” and exclamation mark stressing the tentative nature of his remarks but (at the same time) offering a tantalizing suggestion that there may have been some actual connection between Kidd’s alleged map and the island it represented and the map and location of the fictional ‘Treasure Island’ of Stevenson’s novel (1883). Articles reporting the main points of Wilkins’ article and reproducing its map appeared in the Tokyo Nichi-Nichii and Yomiyiuri newspapers in February 1937. (While few main island Japanese would have had any perception of a resemblance between the island depicted and that of remote, southerly Takarajima; the Yomiyuri made the connection explicit, proclaiming, “Treasure Island, it’s in Japan!” (NB note that despite the different alignment of the compass roses in the two maps below, the islands represented do have distinct similarities) (Fig. 6).

Claims for Takarajima as the location for Kidd’s buried treasure have subsequently been circulated in English language publications and websites, such as Fanthorpe and Fanthorpe (2009, p. 181). While various attempts have been made to locate the treasure, none has been found. This is unsurprising. The identification of Takarajima as the location of Kidd’s horde is highly problematic since – unless historical records have been lost or were originally fabricated – Kidd never ventured into the South China Seas. Another folkloric embellishment of the Kidd account recounted to us in 2009 on Takarajima has similarities with the 1824 incident, in that some accounts have Kidd requesting cattle from the islanders and then staging an attack when these were not granted. In contrast to the historical incident, the attack is recalled as successful and Kidd’s party is supposed to have burned a number of Takarajimans to death in a limestone cave before hiding their treasure in another.

Unlike the violent encounter with British mariners in 1824, which has been memorialised in the form of a small plaque and park (Fig. 5), the more folkloric association with Kidd’s visit has been primarily represented pictorially in island maps (see Fig. 7) designed for tourists and, in one notable case that we encountered on the island, via bodily illustration, as a tattoo (Fig. 8).

Given the above, we were interested to investigate the reasons for the identification of Takarajima as the location of Kidd’s treasure and the role this perception had in local culture during our fieldwork on the island in 2009. Interviewing islanders of various ages we established the following:

- (1)

- The oldest islanders that we interviewed (who were in their 70s) recalled that they were aware of the Kidd association with Takarajima as children (i.e. during the 1940s) from family and social interaction; which suggests that the association may have been established prior to that period (if their recollections are correct);

- (2)

- There is no local evidence of Kidd’s visiting the island;

- (3)

- That there were varying degrees of skepticism about the story and its veracity within the community;

The obvious characterisation to make here is that the Kidd connection is a folkloric – rather than historical-factual – one. This characterisation, of course, does nothing to diminish the significance of the Kidd connection but does contextualise it. In attempting to understand the rationale behind the association we researched and uncovered what we tender here as a plausible explanation.

In the absence of detailed historical accounts it cannot be ascertained when perceptions of Takarajima as the location of Kidd’s treasure were first established in Japan but one possible cause might be the cross association of the Kidd myth with a more modern fictional representation of piracy: Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel Treasure Island. The book was first published in London in 1883 and drew upon established tales of pirates and pirate treasure that had developed in the 1700s and early 1800s that had been previously addressed by writers such as Charles Kingsley in At Last: A Christmas in the West Indies (1871).

Stevenson’s book (or, more precisely the general theme of pirates and buried treasure) formed the basis of a Japanese language text that appeared twelve years later (Miyai, 1895) in four-part serial form in a monthly literary club journal entitled Bungei Kurabu and was subsequently re-published in single volume form in several different editions. Of particular interest to us was the title given to it: Shinsaku Takarajima. ‘Shinsaku’ means ‘new’ but it is obviously the latter word that is of most significance for this article. Takara-jima is a compound word. ‘Jima’ is fairly straightforward, meaning island (an alternative spelling pronunciation of ‘Shima’). The meaning of ‘Takara’ is more intriguing. The earliest written rendition of the name of the (actual) island discussed in this article occurs in the Nihon Shoki, an historical work dating back to 720, which refers to the island as Tokara (Toshima-Son Shi, 1995: 561). A Korean map dating back to 1471 also refers to it as such (ibid: 550). But by the Edo period (17th Century), the island’s phonetic name became associated with the Japanese word takara, with historical accounts identifying the island as Takarajima and the island chain as Tokara (ibid: 561).11 Takara has several inter-related meanings that offer various explanations of the island’s name. One is that the island itself is ‘treasured’ and worth ‘treasuring’. And this is indeed a credible explanation given the island’s arable land, abundant seafood resources and water (particularly in contrast to the more northerly Tokara islands). The second commonly understood usage facilitates exogenous association, since ‘Takara-jima’ can be literally translated into English as ‘Treasure Island’.12

Shinsaku Takarajima wasn’t a translation of Stevenson’s novel but rather a ‘re-imagination’ that localised the novel’s themes and centred the narrative on a Japanese boy bequeathed a treasure map by his deceased sea-captain father, who embarks upon a series of maritime adventures around a mysterious small island, fighting pirates and eventually finds the treasure. The association of (the actual) Takarajima island with (latter-day) pirates is, to some extent, congruent with regional history since there is folkloric record of a band of pirates led by an individual from Miyazaki prefecture named Yosuke Azuma plaguing the Tokara islands and southern Kyushu in the period 1573–91 (ibid: 497). It is difficult to ascertain how prominent folkloric inscription of these activities was in regional culture prior to the Meiji restoration and the opening up of Japan to several hundred years ‘backlog’ of international cultures. But, at the very least, it is possible that the popularity of the Japanese translation of Stevenson’s book offered a specific interpretation of and understanding of the term takara that allowed both Japanese in general and Takarajima residents in particular, to form a very specific sense of what the term ‘Takarajima’ might mean.

For the sake of our argument we’ll offer a hypothesis at this point that ‘Takarajima’ (the actual island) acquired perception of itself as associated with Stevenson’s fictional Treasure Island (cross-associated with the history of Kidd’s exploits) at some point after the publication of the ‘Bungei Kurabu’s’ translation/adaptation in 1895, perhaps as a result of the previously discussed aside in Wilkins (1936) and the publication of articles referring to this in the Tokyo Nichi-Nichii and Yomiyuri in 1937; and that this intensified some time after the youth of our older interviewees (in the 1940s).

Macleod offers a stimulating analysis of factors and processes by which individuals or groups create or change “a representation of a cultural group and associated place” (2013: 1). He terms this cultural realignment and defines this as referring to:

the marketing of images and branding of a group of people, dwelling place or cultural site; the promotion or reorganisation of tangible and intangible heritage; as well as the written description of such phenomena where the specific intention is to realign the subject matter. (ibid)

While Macleod’s study primarily addresses contemporary and functionally directed efforts to modify cultures so as to gain market advantage in tourism; there are elements in his characterisation pertinent to our study of a more protracted and more diffuse realignment of heritage aspects and locational branding on Takarajima. Drawing on Macleod’s formulation, we might ask what advantage might acquisition of a folkloric connection to Kidd and Treasure Island have for its community? A variety of explanations are possible, of which we would argu these are the most plausible:

- (1)

- For a community that already had exogeneity as a clear marker of its difference from its southern neighbours it was a further confirmation of that difference – and a further element of historical colour and glamour in the island’s internal ‘identity myth’;

- (2)

- In the post-War era, with the development of tourism, it offered a ‘brand advantage’ for the island against its competitors.

The first possible explanation is difficult to prove one way or another but there is evidence to support the second. This concerns the manner in which while the older islanders recall growing up with an awareness of the Kidd connection they perceived it to have become more prominent and understood more ‘historically’ (rather than folkloristically) in recent decades. Here another factor comes in. While the first Japanese version of the Shinsaku Takarajima narrative was published in 1895, the story and name were significantly revived in Japanese popular culture with the publication and considerable popularity of a volume that is widely recognised to have pioneered the popularity of manga (‘comic book’) narratives with Japanese children. As Kinko (2005: 466) has elaborated:

In the years following the end of war, there was a rush to found new manga magazines… The majority of Japanese people were hungry and poor right after the war; they were not satisfied with the government politics, and had fears and uncertainty about the future. The country was devastated, and the people were starving for entertainment and humor [and] Manga was easily affordable (2005: 466).

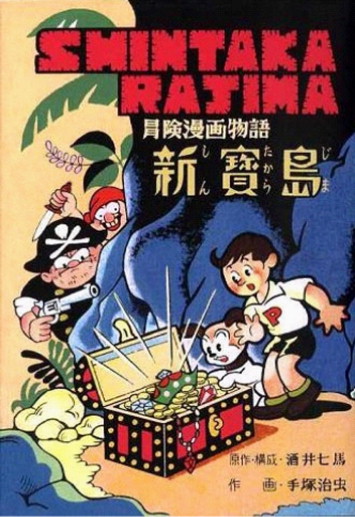

Tezuka Osamu’s Shin Takarajima,13 published in 1947, was a 200 page long visual narrative that sold 400,000 copies on initial publication that displayed “cinematic techniques” that were a significant influence on subsequent manga artists (ibid). In this regard, we might ascribe to Tezuka’s text a dual (affirmative) role: first, reinforcing and popularising Takarajima as ‘Treasure Island’ in a historical-mythological sense; and, second, associating the (very under-developed and pre-modern) Takarajima island with the most contemporary and fashionable Japanese form of the immediate post-War era (Fig. 9).

Prior to the 1960s Takarajima and the rest of the Tokara islands were highly inaccessible, with no regular ferry routes to or from main island Japan or Okinawa. The introduction of ferry routes and jetties on the Tokara islands as part of a central government initiative facilitated easier access to the islands for northern tourists and prompted a vogue for southern island tourism in the late 1960s/early 1970s that brought the first tourists to Takarajima. An NHK TV documentary first broadcast in August 1971 as part of the series Shin Nihon Kiko (‘New Travels in Japan’)14 shows a dramatic contrast between fashionable, mini-skirted female Japanese tourists and Takarajima islanders dressed in traditional peasant clothing. More interesting for the focus of our analysis is that one of the activities offered to tourists was scrabbling around in the sand, following a map and trying to unearth Kidd’s treasure on an island beach. Broadcast on national TV and featured in subsequent tourist promotion, we can see how the ‘Treasure Island’ association was promulgated in Japanese mass media and how it was productive for islanders to accommodate the association themselves. The association was boosted further with the production of a feature film adaptation of Stevenson’s novel (directed by Hiroshi Ikeda) entitled Dobutsu Takarajima (1971) and also a 26 part anime television series directed by Osamu Dezaki, entitled Takarajima (1978), adapted from Stevenson’s original novel. The interaction between fiction and folklore continues. In 2006, for instance, during an extended Japanese TV ‘telethon’ broadcast on NNS (entitled ‘24 Hour Television ‘Love Saves the Earth’ 2006), studio sequences were interspersed with shots of people frantically digging for treasure on a beach on Takarajima’s east coast, using the map ‘discovered’ in 1936 as a guide.15

Eclipse(d) expectations

In July 22nd 2009 the Tokara Islands were ideally situated to observe a brief total solar eclipse. In the year leading up to this there was much expectation in the archipelago that substantial numbers of tourists would arrive to view the phenomenon. While these eventually amounted to little more than an additional trickle on top of usual summer visitation, it gave the island the opportunity to spruce up its signage and self-representation. The main manifestation of this was the design of a new map, reproduced on signage outside the village hall and available as a postcard (Fig. 7), on sale at the island post office (representing the only postcard of the island available for purchase). The image notably represents a pirate era sailing ship off the island’s North West coast.

Such local representations continue to guide visitor expectations and subsequent representations. In 2011, for instance, the website ‘Outdoor Japan’ further embellished local folklore with the following account:

A pleasantly cool breeze, the sound of transparent water flowing by, outside the strong rays of a hot sun beat down. Moving further and further back into a limestone cave, looking for treasure…

This is Takara-jima, Treasure Island. The name of the island really is Treasure… I don’t want to give away the exact location, but it’s between Kyushu and Okinawa… The reason I don’t want to give too much information goes back to May 23, 1701. On that date in Scotland, just as he was about to be executed, the famous pirate Capt. Kidd shouted, “I have hidden treasure,” but the executioner paid no attention and carried out the sentence without hearing Kidd’s explanation.

More than 200 years later, in 1937, some confidential information arrived in Japan in a letter from the U.S. According to Kidd’s log, the letter said, he had buried some treasure taken in the South China Sea in the Nansei Islands. The description of the location of the treasure was in a depression known as Shi-no-Tani (Death Valley), in a place where an active volcano continuously spews poisonous gas. On the east side of Takara-jima is a place just like this, called Kyogamine. There are any number of limestone caves here—ideal hiding places. Many, many treasure hunters have come to this spot but, as yet, no treasure has been found. (Unattributed, 2011: online)

This brief item is highly inventive – fast and easy with historical facts (such as wrongly identifying Scotland as Kidd’s place of execution, citing passages that weren’t in any copy of a log that has come to light etc., identifying a beautifully mysterious Shi-no-Tani (Death) Valley and pretending to be coy about the actual location of the island.

Implications

In his classic study of the development of Indonesian national identity, Benedict Anderson (1983) coined the term ‘imagined communities’ to refer to national populations who had no chance of ever meeting or knowing any but the tiniest fraction of their population. The situation is the opposite in Takarajima (as in many other minimally-populated small islands), as members of the population do meet and know each other. But this doesn’t mean that the island community’s identity isn’t also ‘imagined’ indeed our research suggests that, on Takarajima at least, the imagination is also complex and contentious. In the case of Takarajima, the weaving of exogenous elements – in the form of Heike myths of origin, encounters with British ships during the Sakoku era and western pirate stories – re-mediated through various forms of Japanese popular culture that embody modernity and then re-inscribed and refracted through internal and external tourist-orientated discourse has formed an imagined identity marker for the community. This serves to distinguish the population of a small, remote island as both ‘special’ and connected to global historical networks that belie any consideration of it as marginal, underdeveloped and/or obscure. The pirate treasure connections are thereby ‘treasured’ as cultural assets as important as any doubloons that might be unearthed by a lucky future fortune hunter (despite the lack of archaeological evidence to support such ventures). As geographically isolated as the island is, its folkloric connectivities to external elements continue to be important aspects of how it imagines itself in and represents itself to the world. These aspects confirm Macleod’s contention that islands are particularly “vulnerable” to cultural realignments that promise to facilitate brand advantage in a competitive marketplace (2013: 3) where remote islandness is not, in itself, a premium attraction. While the everyday activities of the subsistence lifestyle followed by the majority of contemporary Takarajimans does not involve active invocation of exogenous mythologies and associations; these elements provide an intangible heritage that distinguishes the island from its neighbours and that can be easily mobilised to represent the island to visitors.

Endnotes

Tokara-Kannonshu wa musubi no kami yo

Nanado maire ba tsuma tamoru.

Tokara-Kannonshu ga tsuma tamoru nara

Washi mo mairo ka nanado-han.(Tokara Kannonshu is a deity dedicated to marriage.

After seven visits you will be given a wife.

If Tokara-Kannonshu can give you a wife.

I will also visit, seven and a half times.)

Tokara deru tokya namida ga deta ga

Kojima sugireba uta-gokoro.

Tooku hanarete yuku mi no tsurasa

Ato ni nokorite naku bakari.(When I left Tokara, tears came to my eyes.

But after we passed Kojima, I felt like singing.

How sad to be far away from my island

Left alone and crying all the time.)

Horecha naran yo takoku no hito-nya

Sue ga karasu no naki wakare.(Don’t fall in love with people from other places

It will end with you parting in tears.)

References

- Amamigaku Kanko Linkai, 2005 Amamigaku Kanko Linkai Amamigaku: Sono Chihei to Kanata. Nanpou Shinsha, Kagoshima (2005)

- Anderson, 1983 B. Anderson Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, London (1983)

- Collis, 2011 J. Collis Of ‘The Green Man’ and ‘Little Green Men. A. Gazin-Schwartz, C. Holtorf (Eds.), Archaeology and Folklore (second, revised edition), Routledge, London (2011), pp. 126-132

- Fanthorpe and Fanthorpe, 2009 L. Fanthorpe, P. Fanthorpe Secrets of the World’s Undiscovered Treasures. Dundurn Press, Toronto (2009)

- Ito, 2003 Ito, S., 2003. The position of the Ryukyu Jomon culture in the Asia-Pacific region. Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association Bulletin 23 (Taipei Papers v1), 63–66.

- Ito, 2005 K. Ito A history of manga in the context of Japanese culture and society’. J. Popular Culture, 38 (3) (2005), pp. 456-475

- Kingsley, 1871 C. Kingsley At Last: A Christmas in the West Indies. Macmillan, London (1871)

- Kumamoto Daigaku Koukogaku Kenkyu-shitsu, 1994 Kumamoto Daigaku Koukogaku Kenkyu-shitsu (1994), Tokara Retto no Koukogaku-teki Chousa (An Archaeological Investigation of the Tokara Islands), Kagoshima: Toshima-mura Kyouiku Iin’kai, pp. 6–15.

- Macleod, 2013 D. Macleod Cultural realignment, islands and the influence of tourism. Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island, Cultures, 7 (1) (2013), pp. 1-19

- Osamu, 1947 T. Osamu Shin Takarajima. Shogakukan Creative Inc, Tokyo (1947/2008)

- Pearson, 2007 R. Pearson The early medieval trade on Japan’s southern frontier and its effect on Okinawan state development: grey stoneware of the East China Sea. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 11 (2) (2007), pp. 122-151

- Stevenson, 1883 R.L. Stevenson Treasure Island. Cassel and Company, London (1883)

- Unattributed, 0000 Unattributed, nd. “Takarajima” the Treasure Island. <http://home.f01.itscom.net/yaeno/Cap.Kidd05.html>.

- Unattributed, 2011 Unattributed, 2011. High tide: Treasure Island (Takara Jima) Outdoor Japan n38, online at: <http://outdoorjapan.com/magazine/column_details/380>.

- Wilkins, 1934 H. Wilkins Modern Buried Treasure Hunters. Philip Allan, London (1934)

- Wilkins, 1936 Wilkins, H.T., 1936. MAPS Spur New HUNT for Kidd Treasure. Modern Mechanix, November: 42–45, 152–155, 157, 166, 169.

- Yoshida, 2008 Reiji Yoshida, 2008. Tezuka — keeper of ‘manga’ flame: classic ‘47 work’s reprint fuels debate over originator of modern cartoon craze. Japan Times November 19th – online at: <http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20081119f1.html>.