The Functions of Myth in Mangrove Ecotourism Development in Ibu Kota Nusantara, Indonesia

Abstract

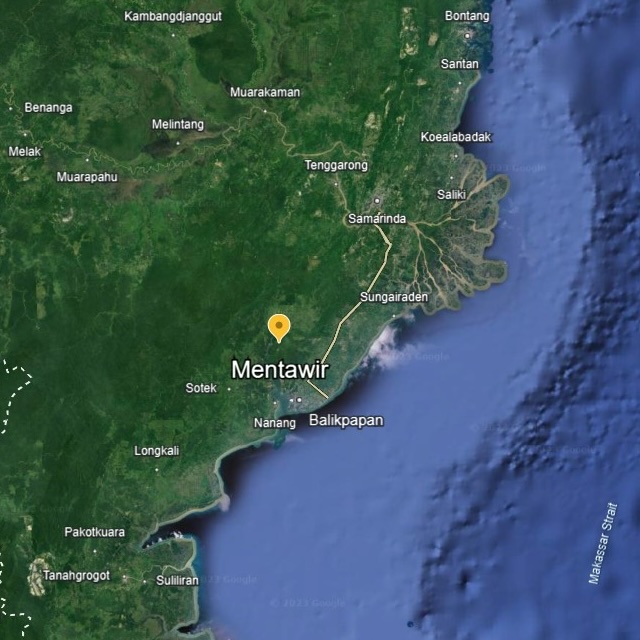

The mangrove area in Mentawir Village has the potential to be developed into an ecotourism site in Nusantara Capital City (Ibu Kota Nusantara or "IKN"), Indonesia. Apart from the mangrove conservation area, some myths add to the tourist attraction of IKN. Various myths continue to live and develop in the lives of the Paser indigenous people in Mentawir Village (Sepaku District, East Kalimantan Province, Indonesia). The functionalization of the myth is expected to support mangrove ecotourism. So, how can existing myths affect the use of mangroves to support the development of mangrove ecotourism in IKN? Ethnographic data collection conducted through participatory observation and in-depth interviews can reveal the existence of myths that affect the use of mangroves in people's lives. The results showed that three myths developed in Mentawir Village: the myth of yellow mangroves (lemit mangroves/bakau lemit), the myth of the Mentawir River (Sungai Mentawir), and the mystery myth of the peace stone (misteri batu perdamaian). Using the Malinowski cultural functionalization approach, it can be seen that these myths can support the development of mangrove-based ecotourism and creative economy as IKN tourist attractions that can support community welfare.

Keywords

mangrove, myth, ecotourism, Ibu Kota Nusantara (IKN), Paser

Introduction

Myths are part of oral traditions passed down from generation to generation in people's lives. Myths are passed down from generation to generation. There are many countries and ethnic groups that use myths for cultural life, both individually and socially. Al-kadi (2023) states that myths can play a role in social and political life and even show national identity. From the results of previous research, myths still play a role and persist in the community that supports them. For example, Alatinga et al. (2021) state that traditional public belief in the truth of the meaning of myths is still very strong. Meanwhile, Waitt (1999) provides information that myths survive in a community because of efforts to defend indigenous communities, such as those related to environmental myths, hoping that the environment will be protected from people who would destroy it. In another study, Al-kadi (2023) stated that myths persist because there are myth speakers and the belief that myths are part of belief itself.

The use of various myths is still ongoing today in various parts of the world, such as in the religious, social, economic or trade domains, learning media in educational institutions (both formal and informal), health, entertainment, as well as material in dozens of scientific research as well as part of sources ecotourism in an area. Honzíková et al. (2023) found the role of myth as a medium for weather forecasting, supporting agricultural practices, and religious ceremonies in Czech. Aulia Rahman Alhaq & Murwonugroho (2022) provide information on the characterizations in myths used to design snacks in Japan as a trade strategy to attract consumers. Perbawasari et al. (2022) stated that health myths can improve people's health in Pangandaran, West Java, based on local perceptions of the usefulness of mythical objects. Purnani (2014) stated that the Reog Ponorogo myth can be useful for educational institutions in instilling cultural values in children through language and literature learning materials. Nosov (2023) found that oral literature is entertainment for Chinese society and a lesson in behaving effectively in social and state life. Meanwhile, Qiu et al. (2022) emphasized that the myths of society are part of an interesting tourist resource, both for research material and for ecotourism-based tourism. Research on tourism in the world was conducted in 76 countries on five continents: Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Europe, Australia, Canada, the United States, the Netherlands, Poland, Japan, China, Australia, Malawi, Ecuador and Jamaica.

In this regard, the Paser traditional community in East Kalimantan, part of world society, still maintains and utilizes myths to support their life activities. This statement can be proven by Aisyah (2020), who noted that the Paser community used pamali to educate generations. Paser people know besoyong (mantra) in every activity to ask for safety (Kristanti, 2019). Besoyong, a large activity, can improve the community's economy by bringing in tourists from various corners. Istianingrum & Retnowaty (2018) explain that the Paser people know the Tipong Tawar mantra in agricultural rituals. The benefit of this mantra is that it is part of society's projection system towards social norms.

Paser people are indigenous communities living in the area of North Penajam Paser Regency (Regional Regulation of North Penajam Paser Regency Number 2 of 2017 concerning the Preservation and Protection of Paser Customs [Peraturan Daerah (Perda) Kabupaten Penajam Paser Utara Nomor 2 Tahun 2017 tentang Pelestarian dan Perlindungan Adat Paser], 2017). Currently, in North Penajam Paser Regency, especially Sepaku District, the Nusantara Capital City (IKN) development process is underway. The construction of IKN, which carries the concept of a future smart forest city, is expected to consider and empower local wisdom, especially ecological myths still developing and believed by the Paser indigenous community to protect and preserve the environment.

In the lives of Paser indigenous people, especially in Mentawir Village, Sepaku District, North Penajam Paser Regency, myths are still known. In Mentawir Village, at least 3 myths are still alive: the myth of yellow mangroves (lemit mangroves/bakau lemit), the myth of the Mentawir River (Sungai Mentawir), and the mystery myth of the peace stone (misteri batu perdamaian). These myths tell of mangrove plants connected with the life of sacred predecessors. The plant containing this myth is located in the Balikpapan Strait. It is in that place that ceremonies related to mangroves are held. There are still active speakers who master the myth with all its supporters. The strong belief in the mangrove myth affirms the identity of the Paser people, who have powerful predecessors. The existence of powerful ancestors in the mangrove area has caused the myth of mangroves not to disappear in the community of speakers. This condition has a positive effect, namely mangrove preservation because the local community takes good care of the relics of glorified ancestors. A form of conservation carried out by the community is to utilize mangrove resources that stretch along Balikpapan Bay. They produce various creative products that can support the welfare of residents.

Mangrove forests as one of the tropical ecosystems that are threatened with extinction must be preserved (Susilo et al., 2023; Lillo et al., 2022). The myth and use of mangroves are interesting to research because, based on field surveys, there is evidence that the expanse of plants can attract tourists. Various creative products made from mangroves must be kept from the attention of the government and tourists, both domestic and foreign. Previous research illustrates that mangroves support the source of community welfare (Yasser et al., 2021). These sources of welfare include protecting biodiversity (e.g.fish) that benefits fishermen. Risky (2022) states that mangroves in Balikpapan are attractive to tourists. Rahman & Pansyah (2019) found that people can cultivate crabs in mangrove areas. However, research that takes mangrove objects has yet to review the use of these plants as interesting processed materials, both in how to process them and recognize their taste. Even though this study is an opportunity for researchers from within and outside the country, this research team tried to explore the myth of mangroves in the lives of the Paser people and explore knowledge in mangrove processing without destroying their habitat.

By paying attention to the social, cultural, and environmental landscapes of the community, especially mangroves that bring disaster mitigation and welfare, the development of ecotourism and creative economy in the IKN area is a solution for cultural preservation amid sustainable development (Rahayu, 2022). Mangrove protection, in this case, is a priority. Therefore, public education on maintaining environmental ecosystems by empowering the knowledge of local communities is important (Mutaqin et al., 2021). For biological habitats not to become extinct in the IKN area, mangrove forests must be preserved (Eni & Sudarwani, 2021).

Mangroves, which provide various benefits for various people's lives (Buenavista & Purnobasuki, 2023), in Mentawir Village often functioned in the realm of the creative economy by processing these plants into various industrial products, such as syrup, tea, coffee, dodol, and cold pupur. In addition, the existence of mangroves is an attractive tourist destination. Through functionalizing mangrove myths in Mentawir Village, ecotourism (based on ecology and tourism) in the IKN area can be developed. By involving tourism awareness groups (kelompok sadar wisata/pokdarwis) in the village, various creative products of local communities can be produced to improve the economy. Thus, the mangrove myth can be used as a medium to protect biodiversity while supporting sustainable IKN development.

The mythology of mangrove cultural ecotourism, if processed, worked on, and created, will certainly meet the needs of people's lives. In the theory of cultural functionalism, the culture of ethnicity will survive when it can meet the basic human needs contained in it. So, can the existence of myths affect the use of mangroves in people's lives? What are the functions of mangroves, and how are they utilized? How can the three myths in Mentawir Village be used to support the development of mangrove ecotourism in IKN? Thus, in general, this research aims to describe the existence of myths that can affect the use of mangroves in people's lives; describe the function and utilization of mangroves; and describe the myth of yellow mangroves (mangroves lemit), the myth of the Mentawir River, and the mystery myth of the peace stone that developed in Mentawir Village, Sepaku District, East Kalimantan.

Materials and Methods

Malinowski's Cultural Functionalism

Malinowski states that myths have meaning and function in the lives of those who tell them. Myths are not fiction but a fact of energy believed to have occurred in ancient times (Malinowski, 2014). Myths are indispensable in primitive cultures because they express beliefs, maintain and uphold morality, guarantee ritual efficiency, and contain rules of thumb to guide man. Therefore, myth is an important element in human civilization (Malinowski, 2014). In Malinowski's functionalism, myth serves to satisfy the essential, even biological, needs of the survival of the culture in question (Strenski, 1992).

The idea of cultural functionalism addresses the cultural needs of the owners. Malinowski states that by necessity, the system of the human condition in a cultural setting and its relationship with the natural environment is necessary for the survival of groups and human organisms (Piddington, 1960). Culture is said to fulfil fundamental human needs because in this culture, various traits are born that are needed by every individual or human, such as biological, psychological, and instrumental needs. These needs are considered important for human life because they must be met by every human being, whether individual or in a community or society. Culture has a role in fulfilling human biological and psychological needs. According to Malinowski (1960), 7 basic biological and psychological needs influence scientific and positivistic cultural responses, as seen in the following table.

| Num. | Basic Needs | Cultural Responses |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Metabolism | Commissariat |

| 2 | Reproduction | Kinship |

| 3 | Bodily Comfort | Shelter |

| 4 | Safety | Protection |

| 5 | Movement | Activities |

| 6 | Growth | Training |

| 7 | Health | Hygiene |

Malinowski (1960) compiled a table of basic needs that included (1) metabolism, (2) reproduction, (3) bodily comfort, (4) safety, (5) movement, (6) growth, and (7) health. These basic needs strengthen the cultural survival of an ethnicity. On that basis, basic needs can be used as a foundation for processing myths in developing mangrove cultural ecotourism in Mentawir. The mythological, nuanced cultural aspect can be used as a reference to the process of mangrove ecotourism in Mentawir. Myths embody basic human needs, namely comfort and security, so Paser people tend to perform rituals for salvation. Ritual is a cultural negotiation with the supernatural so that human life is endowed with salvation.

Functionalism holds society as an interdependent organic entity (Strenski, 1992). Culture is a tool humans use to overcome environmental problems to meet their needs. The elements are unified, interdependent, and organized in economic, political, legal, and educational cooperation activities in families, clans, local communities, tribes, and organized teams (Malinowski, 1960). In this connection, Malinowski suggests that the analysis of cultural institutions be based on their functions that support the salvation of human life. In processing the myth of ecotourism in Mentawir IKN, a special strategy is needed to integrate cultural aspects, especially myths.

When cultivating mangrove cultural ecotourism, it is necessary to stick "to grasp the native's point of view, his relation to life, to realize his vision of his world" (Urry, 1995). Field notes called "diaries" are needed in excavating myths as thick descriptions to explore the meaning and function of myths with detailed explanations to understand significant and complex cultural implications. With ethnographic data in the excavation of myths in the Mentawir Beach area, it is expected to realize residents' creativity when processing mangrove ecotourism into a tourist commodity. The community utilizes the natural wealth of mangroves in Mentawir to meet their needs, especially in developing ecotourism and the creative economy of mangroves in the form of innovative products produced by the local community. For example, a creative economy that can empower the myth of yellow mangroves combined with rituals will be a tourist attraction.

Research Methodology

This research uses a cultural functionalism approach with all elements of culture that can finally be seen as fulfilling the basic needs of the community's citizens (Kaberry, 2002). This research was conducted in Mentawir Village, Sepaku District, North Penajam Paser Regency, on June 1-20, 2023. The locus was chosen because, based on initial information obtained in the village, the community still believes in many myths. The research team went directly into the field by conducting documentation, participatory observation, and in-depth interviews. The data that has been collected is cross-examined through triangulation of sources (informants) to make it more convincing. The informants involved in this research are shown in the following table.

| Informants | Position in The Community |

|---|---|

| Informant 1 | Prime Minister of the Paser Sultanate |

| Informant 2 | Paser Traditional Institution |

| Informant 3 | Paser Traditional Defense Laskar |

| Informant 4 | Community Figure of Mentawir Village |

| Informant 5 | The Deputy of Social, Cultural, and Community Empowerment for The Nusantara National Capital Authority (NNCA) |

| Informant 6 | Department of Culture and Tourism of North Penajam Paser Regency |

There were six participants in this research. All informants are men. Informants were selected using a purposeful sampling method, namely by assuming that the selected informants were very informative (information-rich cases) (Patton, 2014) regarding the mangrove myth in Mentawir Village. These six informants represent various stakeholders in the Paser traditional community structure.

In this case, the interviewer asked the interviewee a question (Lexi Moleong, 2007) about various ecological myths that live and develop in the Paser indigenous community in Mentawir Village. Research data collection uses in-depth interviews and conservation to obtain valid data. This technique is carried out in a flexible, familiar, and familial manner, which is expected to pry and capture the honesty of informants so that actual information is obtained. In the interview, researchers asked informants about the myth of yellow mangroves, the mystery of the peace stone, and the Mentawir River. Before conducting an interview, researchers make interview guidelines that contain several questions related to the research theme so that the subject matter obtains data. Interviews were conducted with community leaders and tour guides in Mentawir Village. Paying attention to the following conditions is necessary to get valid data from informants; (1) informants are community leaders who understand and have much experience with problems related to mangrove myths, (2) informants are indigenous people of Mentawir Village who are the object of research targets, and (3) informants are leaders of the Paser indigenous community who understand ecological myths that develop in Mentawir Village.

Observations are also carried out in collecting data, interpreted as systematic observation and recording of the phenomena studied (Sutrisno, 2004). This observation method was used to obtain data about the Mentawir community, especially regarding people's perceptions of existing myths. When making observations, researchers come directly to the research location, make observations, and record the data obtained so the data can be processed or analyzed later. The results of observations are also immortalized in the form of pictures, namely photos and videos. The data obtained in observations include the myth of yellow mangroves, the myth of the peace stone, the myth of the Mentawir River, and local creative products from using mangroves.

Documentation methods are used to obtain data to complement and strengthen previously obtained data. The documents referred to in this study include all archives collected while the research is ongoing, either orally, in writing, or pictures or photos. Researchers use mobile phones to record video, sound, and photos to pray for data deemed necessary to be captured so that there is concrete evidence to see. The documents in this study are in the form of photographs related to research problems, namely myths in Mentawir Village and various creative products from these plants. The data is expected to support and strengthen what is obtained from observations and interviews.

The validity of the data is an important factor in research. Therefore, it needs to be checked before analysis is carried out. So, the data collected during the study must strive for stability and correctness. Data validity is especially useful for determining whether data will be used as a research source. The validity of the data in this study was obtained through triangulation. Triangulation is a technique of checking the validity of data that utilizes something other than that data as a comparison (Lexi Moleong, 2007).

The stages of data analysis carried out are: (1) data from the interview recordings are transcribed in written language roughly without paying attention to punctuation, (2) the data from the transcript is integrated and adjusted to the recordings, (3) the results of the initial transcript are then corrected and punctuated properly and correctly, (4) after the transcript data is collected in the form of Indonesian writing, it is then categorized for analysis related to the function of myths in Mentawir Village in the development of ecotourism and creative economy of IKN based on the perspective of Malinowski cultural functionalism.

Results and Discussion

The Existence of Myths in Mentawir Village

This paper uses cultural functionalism to work on the magical, ritual, and mythological aspects of cultural owners, namely the Paser indigenous community. Cultural aspects of ecological myths in Mentawir Village can be processed and created in the development of ecotourism and IKN's creative economy. Local people's belief in myths is part of local people's beliefs in religious myths of the Iden religion in the past. The ecological myth here is still visited and told, and the place is maintained, as well as being a guide for local people by obeying the prohibitions contained in the myth. The functionalization of the ecological myth of the Paser indigenous community in Mentawir Village is carried out to support the development of ecotourism and the creative economy of IKN by utilizing mangroves in local creative products, such as coffee, tea, syrup, cold pupur, which are supported by various parties for their sustainability, such as the government, pokdarwis, culturalists, tourism managers, and the community.

In a focus group discussion held by the research team with local residents, one informant stated that they believed in the existence of myths in everyday life.

"The myth has something to do with nature conservation. For example, in Paser, some trees, such as banyan, ironwood, and puti trees, are thought to be inhabited by spirits. So, the trees are big. So, I remember when I was a child, I went with my parents into the forest. The forest is not an ordinary forest but a virgin forest. The wilderness has no traces of humans at all. Opening the route still uses a machete. Never mind, companies, even humans, do not enter. However, my parents and I managed to enter. We were with several groups of families. There, you will find big trees whose roots are like walls. According to the Paser people's myth, do not pee there, don't hit them, or the residents will get angry. Many like that. When this is done, it can result in headaches and fever (the FGD activity on June 13, 2023)."

Mentawir Village, Sepaku District, is included in the IKN development area. The Mentawir Village area is in a protected forest area that is used as a nursery for Mentawir, a nursery for millions of tree seedlings to restore the function of Kalimantan's natural forests in the midst of the construction of IKN, which carries the future smart forest city. In Mentawir Village, there is a mangrove forest conservation area managed by PT Inhutani I UMHT Batuampar Mentawir. This area has the potential to be developed into IKN ecotourism with the charm of mangrove forests in the middle of the waters of Balikpapan Bay, kelotok boats for fishermen who are looking for fish, stalls in the middle of Balikpapan Bay that provide drinks and snacks, and views of the port where raw materials are transported for the construction of IKN. The existence of myths in Mentawir Village also supports Mentawir's ecotourism attraction, including the myth of yellow mangroves/bakau lemit, the mystery of peace stones, and the Mentawir River.

The myth of yellow mangroves is still developing and is believed by the Paser indigenous community, even by other people, namely the Bugis who currently inhabit the Mentawir area. Based on the narration of one of the Paser traditional leaders, according to the beliefs of the Paser indigenous community who used to live around the area which is now included in the administration of Sepaku District, North Penajam Paser Regency, there used to be a yellow mangrove tree which was the place where King Tondoi's Nalau dried clothes (clothes and pants). Nalau King Tondoi is the King of the Kingdom of Padang Kero, which was once the center of civilization in the upper reaches of the Telake River and Kendilo River (now both rivers are included in the administration of Long Kali District and Muara Komam District, Paser Regency). It is said that once around the yellow mangrove, it was a very crowded village, and almost every month and year, the Belian Paser ritual was carried out to worship the gods and ancestral spirits of the Paser community who still adhered to the ancient Paser religion, namely the celebration of "Iden". However, one day, the village disappeared and is occult until now. The belian ritual is usually carried out by chanting the besoyong mantra to ask for salvation from the god and ancestors of Paser, establishing a panti, providing offerings, and carrying a crocodile-shaped jakit as a symbol of the God Tondoi, the ruler of the water realm. Sesajen Belian Paser there are various types of native chickens with certain feather colours; various types of cakes numbering around dozens, including Jaja Onde-onde, Jaja Cudar, Salong, Jaja Petri Mendi, Jaja Sagon, Jaja Pais Pisang, Jaja Sanggar, and others; yellow rice; and perapen (Paser's distinctive incense made of kerembulu wood which has a distinctive smell). The following quote shows the results of the research team's interview with one of the Paser traditional community leaders.

"According to the local beliefs of the Paser indigenous people, who once inhabited the area now under the jurisdiction of Bumi Harapan Village, Sepaku District, North Penajam Paser Regency, there is a significant historical claim associated with the yellow mangrove or lemit mangrove tree. It is believed that this tree was where Nalau Raja Tondoi, the King of the Padang Kero Kingdom, used to dry his clothes (trousers and clothes). The center of civilization of this kingdom was located in the upper reaches of the Telake River and Kendilo River, which are currently under the administration of Long Kali and Muara Komam Districts, respectively, in Paser Regency. It is said that in the past, the area surrounding the Mangrove Lemit was a bustling village, and every month and year, the Belian Paser ritual was held to worship the gods and ancestral spirits of the Paser community who still adhere to the ancient Paser religion. The "Iden" celebration was the most crucial event in the ancient Paser religion, and it was celebrated annually (Interview on July 10, 2023)."

Apart from the yellow mangrove myth, another myth has also developed in Mentawir Village, namely the Mentawir River. Mentawir River is located not far from the mangrove forest conservation owned by PT Inhutani I UMHT Batuampar Mentawir. According to the narration of Mentawir Village community leaders, from the myth that developed, the Mentawir River used to be called the Mentawar River because it could be used as an antidote. When people who are sick with itching, smallpox, or cold heat enter and bathe in the Mentawir River, it is believed to be cured. Therefore, the Mentawir River was finally referred to as the Antidote River. Until now, the myth of the Mentawir River is still believed and used. In ancient times, the Paser indigenous community annually held a belian ritual on the Mentawir River. In the belian ritual, besoyong (a mantra) is spoken, and offerings are presented to the god and ancestors of Paser. There are various offerings in the belian ritual, such as in the belian ritual that is usually carried out; for example, there are 7 kinds of chickens, yellow, red, black, white, grey, bori (striated), and green. The chicken served with the offering is a chicken that is released, and there is a live chicken. Usually, what is released is a black or white chicken. Its meaning, that is, as a tribute to ancestors and a plea for salvation, does not get disturbed. In addition to chicken, there are also various kinds of traditional cakes, such as apam, cucur, rengas fruit (shaped like a crescent moon from flour filled with core), mendut, klepon, white porridge, red porridge, lemang, and others. These offerings are placed in bamboo baked. After serving, a mantra is recited, some of the offerings are presented and handed over as offerings to the ancestors. In this case, the traditional community has given rations to the ancestors, while the rest can be taken home and eaten.

Apart from the myth of the yellow mangrove forest and the Mentawir River, in Mentawir Village there is also the myth of the mystery of the peace stone. The mystery of the peace stone is on the edge of a paved road in Mentawir Village which previously the road was still dirt. The stone that stands firmly on the edge of the road is marked with the words "The Mystery of the Peace Stone" ("Misteri Batu Perdamaian") in white so that passers-by can easily recognize it. This stone is the entrance to the bamboo forest area that leads to the Mentawir River. Because of its location far from the city center and the road to Mentawir Village, which was not good in the past, when there was a visit from officials, for example, during the visit of the Regent of Tanah Grogot in 1987, the community felt happy and honoured. Currently, the location of the road is paved and good, although road access to Mentawir Village in some places has holes because of oil palm access.

Based on the narration of the source, the myths that develop in the community about the mystery of this peace stone always appear in human-shaped appearances, both in the morning, afternoon, and evening. This stone is called the mystery stone of peace because every time people pass by this stone, there are sightings of supernatural beings. In order not to disturb people, traditional rituals were often held here by the Paser Balik indigenous community. However, the current generation is no longer implementing it because the Balik indigenous community living in Mentawir Village is not too much compared to the past. Currently, there are residents living in Mentawir Village from Bugis, Paser, Buton, Madurese, Javanese, Sundanese, and Padang. The following is a witness from a local resident of Mentawir Village regarding the myth of the mystery of the peace stone.

"So, on this stone, which is called the mystery stone of peace, a human-shaped appearance always appears, both during the day and evening, sometimes in the morning. Here, the mystery of the peace stone is written because every time people pass by, there are apparitions. So that it does not disturb people, it is safe, and the guards are not ignorant, rituals are often performed in this place. (Interview on June 11, 2023)."

The existences of ecological myths in Mentawir Village, such as the myth of yellow mangroves, the Mentawir River, and the Mystery of Peace Stone support the development of ecotourism and the creative economy of IKN. The creative economy is able to empower yellow mangroves, the Mentawir River, and the mystery of peace stones combined with rituals can be a tourist attraction. Rituals in ecological myths are performed to ask for blessings and salvation in order to realize people's basic needs of comfort and security. Ritual is a cultural negotiation with the supernatural so that human life is endowed with salvation.

Local People's Belief in Myths

The local community's belief in ecological myths that developed in Mentawir Village is related to the religion of the Paser people in ancient times, namely the Iden belief. In the religion of Iden, four gods are venerated as gods, namely Dewa Sengiang, who rules the spirit realm and is symbolized by white; The god Tondoi, who rules over water and heirlooms and is symbolized by yellow or called the god of welfare; The god Longai symbolized by black; and Lord Nayu who is symbolized by the colour red or called the god of thunder. The Paser indigenous community believes in these gods, embodied in various rituals as a tribute to these gods—one of the rituals still going on is the Belian ritual. Through the belian ritual accompanied by the soyong mantra, mulung—the leader of the belian ritual—can communicate with the gods and ancestors (Nafisah, 2021). Soyong mantra is a form of mantra that is sacred (Mustikawati, 2020). There are various types of belian rituals based on the goals to be achieved, namely medical belian, village cleaning, thanksgiving after harvest, pay nadar, and others.

The community's belief in ecological myths in Mentawir Village can be seen from myths used as guidelines for local communities in carrying out activities. One of them is the prohibition (pamali) in the myth. Around the Mentawir River, pamali or prohibition develops, which, if violated, will have destructive consequences. The prohibitions, namely not to bathe naked in the afternoon, no wagging of hair after bathing men and women, and not dry black clothes around the Mentawir River. If this prohibition is violated, it is believed that the ancestors will appear, visible later. As a result, ancestral spirits will later reprimand the violators, which can cause illness or disaster. If it is reprimanded, to cure it, it is necessary to carry out rituals led by traditional figures by spraying. Keteguran (kepuhunan) also applies to the culture of the Paser indigenous community, namely the nyantap culture. When offered coffee or food, we refuse because the stomach is still full so as not to be stubborn (kepuhunan); the food is taken a little and swept/touched on the limbs, which can be on the cheeks, neck, and others. However, when we forget that we have been offered, we can lick our palms to avoid kepuhunan. Until now, the Paser community and other local people living in Mentawir have still believed in the ecological myth around the Mentawir River.

People's belief in ecological myths that developed in Mentawir Village can be shown from places where the sources of these myths are still told, visited, and maintained. According to Paser traditional leaders, the Belian ritual at the location of yellow mangroves is rare and no longer carried out by the Paser Balik indigenous community. Until now, this myth is still believed to be a sacred mangrove tree, sacred mangroves. As the name implies, this mangrove tree is yellow constantly. Yellow mangroves look different from the green mangrove forests in Balikpapan Bay. To mark it as a sacred tree, rows of yellow mangrove trees were hung with yellow flags as a sign of respect for Lord Tondoi, the ruler of water, where Nalau King Tondoi dried clothes (clothes and pants). With this myth, the existence of the yellow mangrove myth is preserved.

The myth of the Mentawir River is also still being told, visited, and preserved. Bamboo forests are still beautiful to get to the Mentawir River. The paths are still trails along the way because a permanent road has yet to be made to the Mentawir River. People's belief in the Mentawir River as an antidote for various diseases, such as itching, smallpox, cold heat, and others, is ongoing, likewise with the mystery of the peace stone in Mentawir Village. Stories of sightings of supernatural beings in the rock developed and were believed by the public. Its existence becomes something that attracts the curiosity of tourist visitors if it is later developed as an IKN ecotourism. If empowered, rituals, myths, and mythical location sources will attract visitors. According to the informant from Department of Culture and Tourism of North Penajam Paser Regency who were interviewed on June 8th, 2023, it is essential to investigate the myths prevalent in the North Penajam Paser region in order to promote tourism there.

Of the three ecological myths that developed in Mentawir Village, the existence of yellow mangroves, the Mentawir River, and the Mystery of the Peace Stone shows its connection with the belief of Iden in ancient times who believed in supernatural powers, belief in gods who ruled the universe. In these places, belian rituals were often carried out as a form of respect for the gods to ask for blessings and salvation by using soyong mantras and offerings led by mulung or Paser traditional figures. These rituals and myths are still believed to meet basic needs and support the survival of the Paser indigenous community to provide safety and comfort in living life. Cultural rituals in ecological myths that develop in the Paser indigenous community can be processed by combining them with tourism and economic aspects, ecology for developing ecotourism and a creative economy in Mentawir Village.

The Meaning of Myths for the Development of the Creative Economy of Mentawir Village

Mythical empowerment for ecotourism development is needed with the involvement of supporting structures so that they are functionally integrated. Malinowski's structural-functional approach explains that myths as part of the culture will achieve conservation and sustainability if every necessary system remains supportive, such as culturalists, tourism managers, communities, and local governments to develop mangrove ecotourism in Mentawir Village. These supporting structures synergize for the sustainability of myths that support the development of ecotourism and the creative economy of Mentawir Village.

The empowerment of myths in developing mangrove ecotourism in Mentawir Village is supported by community involvement. The community also provides supporting facilities, such as lodging for visiting tourists. Although still limited, accommodations are provided in Mentawir Village, for example, Lamale Homestay. According to the owner, his inn has been rented by visitors several times, either for tourist purposes, work visits, or research. In Mentawir Village, a Tourism Awareness Group (Pokdarwis) Tiram Tambun, a community institution that maintains and develops the tourism sector in Mentawir Village, has also been formed. This Pokdarwis Tiram Tambun supports the development of mangrove ecotourism in Mentawir Village by utilizing the wealth of natural resources in the form of mangroves. Chairman of Pokdarwis Tiram Tambun, Pak Lamale, stated that Mentawir Village has mangrove resource potential. When he attended mangrove processing training, he was interested in processing and developing local creative products from mangroves. Therefore, he brought and practiced making mangrove products from Yogyakarta mangrove experts. Mr. Lamale and the people of Mentawir Village make various products from mangroves, such as syrup, tea, coffee, cold pupur, and dodol.

One of the mangrove fruit products developed by Mr. Lamale is coffee products. This coffee product is made from mangrove fruit called Rhizophora Mucronata. The mucronata fruit used is an old fruit. When it is old, there is a neck-like part that separates the stem from the fruit. If the fruit is removed, shoots will appear, which will later become leaves and stems, while roots will appear at the bottom. If the fruit is young, it is still being prepared for planting stems. If somebody removes the fruit, it will break and not live. Mr. Lamale also did the seeding by placing the mangrove trunk in a polybag. After a month, a few leaves will grow, and at the age of four months, the mangrove trunk is ready to be planted in salt water. Because it is very widely available in the Mentawir Village area, Mr. Lamale and the community use it by processing it into coffee. If all this time, mangrove fruit fell alone and was not used, now it can be used as a coffee product.

The production of mangrove coffee involves the initial step of scraping the fruit and carefully removing the outer layer, which has a brown colour, with a knife. After the cleaning process, the fruit is sliced into small pieces, with some parts of the internal components discarded. These small fruit slices are then immersed in water, undergoing a soaking process. If a continuous stream of water is used, the fruit needs a full day and night to soak thoroughly. However, if water is used in a basin, the soaking process may take longer, possibly spanning two days and nights, as the water needs to be replaced multiple times until all traces of the sap are gone. After that, the fruit is dried under the sun to facilitate the drying process. Once completely dry, the fruit is roasted and ground. This results in the fruit being transformed into a powder-like substance, which is then sifted. To achieve a coffee with a distinct aroma, the powdered mangrove coffee is blended with robusta coffee in a ratio of 70:30, where 70 represents the mangrove coffee, and 30 refers to the robusta coffee. After that, mangrove coffee is packaged into bottles labeled Kopi Mangrove "Lamale".

Syrup products are derived from the fruit of mangrove trees, specifically the pidada fruit (Sonneratia caseolaris in Latin). As stated by one of the informants, individuals residing in coastal areas typically incorporate pidada into their diet. This culinary creation is commonly enjoyed with the addition of salt, soy sauce, flavorings, and chili. Mangrove syrup comprises water, pidada juice, thickening CMC, and citric acid. The process of transforming pidada into syrup involves the initial step of cutting the fruit. If there are any black spots on the fruit, it indicates the presence of caterpillars, which necessitates discarding it. Subsequently, the pidada fruits are pre-cut, meticulously washed, and then ground. Once the grinding process is completed, the pidada is transferred to a basin and subsequently squeezed through a sieve. After that, the pidada is boiled, and once it reaches boiling point, sugar is added in a ratio of 1:1. Following the cooking process, the syrup is filtered and placed in packaging bottles, with a shelf life that can extend up to one month. Consumers have the option to customize their orders depending on their preference for sweetness or sourness. If a slightly sour taste is desired, the composition of pidada can be increased while reducing the amount of water.

The Pokdarwis of Mentawir Village also engages in the production of mangrove products, specifically tea bag products. These tea bags are derived from a combination of mangrove leaves, jaruju leaves, and tea. Historical accounts from the informant reveal that in ancient times in Mentawir Village when tea bags were not yet available, cloth was used as a filtration method for the tea. The cloth would be subjected to hot water, and the resulting liquid would be poured into glasses. If the tea remained in a brown hue, the cloth containing the tea could be suspended and used for another round of tea preparation. In order to make the most out of the abundant jaruju mangrove leaves, Mr. Lamale and the residents of Mentawir Village have taken to producing tea bags. The packaging of these tea bottles proudly presents the various benefits of mangrove tea jaruju leaves, which include anticancer properties, antibacterial effects, anti-inflammatory properties, relief from cough, skin healing capabilities, worm prevention, and crucial compounds for the body.

The product of jaruju leaf mangrove tea has achieved the third position at an international level during the MSME exhibition held in Bali. The advancement of mangrove commodities necessitates the involvement of supportive frameworks, including the government, entrepreneurs, and local communities, in order to surmount the various obstacles encountered, such as financing, production locations, production apparatus, marketing promotion, and distribution. As per the source, in order to establish a cottage industry, a dedicated production facility is necessary to process the goods and store the raw materials, as opposed to the current practice of utilizing one's own home. At present, the production equipment stands prepared, comprising tea bag wrapping presses, tea bag wrapping containers, and tea filling implements for the tea wrapping containers.

However, the packaging container and design of the product have yet to be prepared. Subsequently, it is planned that a single container of jaruju leaf mangrove tea will be filled with twenty-five packets, priced at Rp10,000.00 due to its classification as a rare commodity. As a prerequisite for products with extensive market reach, the jaruju leaf mangrove tea products are also subject to meticulous halal certification. Presently, the marketing of mangrove products is undertaken by Mr. Lamale, specifically through independent promotion. One instance of such promotion occurs when there are visitors or guests accommodated at his residence, at which point he extends an offer of mangrove products to said guests. Maintaining a stock of mangrove products at his place of residence, which also serves as the venue for the Pokdarwis Tiram Tambun Secretariat of Mentawir Village, he ensures their availability. Moreover, during exhibitions or meetings, he consistently brings along mangrove products for showcasing and selling them.

Functionalization of The Mangrove Myth in Developing Ecotourism in IKN

The myth of the yellow mangrove, which originated in the Paser Balik community, is a tale that persists due to the presence of yellow mangrove trees. These trees are where Nalau King Tondoi used his magical abilities to dry clothes, resulting in the transformation of the originally green mangrove leaves into a vibrant yellow hue. This myth continues to be embraced not only by the Paser Balik community but also by the Bugis people residing in the vicinity of the Mentawir area. To signify the sacredness of this yellow mangrove tree, a yellow cloth is ceremoniously placed upon it.

The yellow mangrove myth assumes a crucial role in the conservation of the mangrove forests in Mentawir and Balikpapan Bay. The vital role of myth in the life of the Paser Balik and surrounding communities is in line with the findings of Honzíková et al. (2023), Aulia Rahman Alhaq & Murwonugroho (2022), Perbawasari et al. (2022), Purnani (2014), and Nosov (2023) who unravel the critical role of myths in the lives of their people.

The alleged significance of yellow mangroves in the conservation of mangroves in Balikpapan Bay serves as a means to safeguard biodiversity and promote sustainable IKN development (Rahayu, 2022). The commitment to protecting mangroves, as expressed by Mutaqin et al. (2021), can be achieved by actively preserving this myth surrounding yellow mangroves.

Aligned with Malinowski's functionalism theory, which asserts that myths must address fundamental human necessities encompassing clothing, food, safety and comfort, shelter, and love, it can be argued that this myth about yellow mangroves fulfils human needs, particularly in terms of clothing and food, as it has become a livelihood source for fishermen (Rahman & Pansyah, 2019; Risky, 2022). Furthermore, the local community has developed various processed products derived from mangroves, such as mangrove syrup, mangrove coffee, mangrove cold powder, and mangrove tea.

Moreover, the mythical role of yellow mangroves in preserving mangrove forests contributes to the development of an ecotourism industry and creative economy within IKN. According to the informant from the IKN Authority, who presented at the FGD activity on June 13, 2023, it is imperative to cultivate, nurture, and advocate for a culture that is conducive to tourism. It is because the IKN development prioritizes the social, cultural, and environmental aspects of the community, particularly in relation to mangroves, which offer disaster mitigation and welfare amidst ongoing development.

Conclusion

The functionalization of the ecological myth of the Paser indigenous community in Dewa Mentawir is undertaken to provide support for the advancement of ecotourism and the creative economy of IKN. The myths present in Mentawir Village that are currently evolving and embraced by the local populace include the myth of bakau lemit/yellow mangroves, the enigma of peace stones, and the Mentawir River. The locals' belief in ecological myths that have flourished in Mentawir Village is closely linked to the religious practices of the ancient Paser people, specifically Iden's faith in the rituals performed within these myths. The belief in myths is demonstrated by the presence of myths that serve as guidelines for the local community in their pursuits, such as the prohibitions/pamali outlined in these myths, which elicit reprimands/puhunan when transgressed. Furthermore, the locals' faith in ecological myths is also evidenced by the continued narration, visitation, and preservation of the sites from which these myths originated. The community's involvement in the production of mangrove-based products such as tea, coffee, syrup, dodol, and cold pupur contributes to the advancement of ecotourism and the creative economy by empowering the ecological myths of Mentawir Village.

Strengthening the local culture through the development of tourist destinations rooted in local culture is of great significance amidst the development of IKN. With the influx of thousands of workers and migrants to IKN, it has become a site of cultural contestation among multicultural communities hailing from diverse cultural backgrounds. The abundance of ecological myths in Mentawir Village can be harnessed to bolster the development of IKN's ecotourism. This research lends support to the conservation of mangroves as a tourist attraction of IKN and the creative economy of mangrove products. In this context, culture thrives by fulfilling the needs of people's lives through sustenance, beverages, and comfort. Rituals and myths, serving as cultural products, become distinctive features and strengths in attracting visitors, particularly when complemented by innovative mangrove-based products. The development of ecotourism necessitates the collaboration of various stakeholders, including visitors, cultural enthusiasts, entrepreneurs, micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), the government, and the local community, all of whom are capable of showcasing the natural riches of the mangroves and the integrated cultural products derived from ecological myths, thus establishing IKN as an ecotourism destination renowned worldwide.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Head of the Archaeological, Language, and Literature Research Organization, as well as the Head of the Language, Literature, and Community Research Center at the National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia, for the opportunity given to conduct this research. The authors also wish to express heartfelt thanks to the reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

References

- Aisyah, S. (2020). Makna dan Fungsi Pamali Masyarakat Suku Paser Kecamatan Long Ikis Kabupaten Paser (The Meaning and Function of Practical Community Interest Paser District Long Acts Paser). Jurnal Bahasa, Sastra Dan Pembelajarannya, 10(2), 139. https://doi.org/10.20527/jbsp.v10i2.9372

- Al-kadi, T. T. (2023). The Mythologist as a Virologist : Barthes ’ Myths as Viruses natural , eternal , and thus universal . In this process of signification , As a semiotician , Barthes attempts the Saus behind the surface the id meaning Saus Saussure em the sign ’ s the Sauss.

- Alatinga, K. A., Affah, J., & Abiiro, G. A. (2021). Why do women attend antenatal care but give birth at home? a qualitative study in a rural Ghanaian District. PLoS ONE, 16(12 December), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261316

- Aulia Rahman Alhaq, & Murwonugroho, W. (2022). Metamorfosis Mitos Gaya Jepang Pada Elemen Visual. JSRW (Jurnal Senirupa Warna), 10(2), 228–245. https://doi.org/10.36806/jsrw.v10i2.135

- Buenavista, D., & Purnobasuki, H. (2023). People and Mangroves: Biocultural Utilization of Mangrove Forest Ecosystem in Southeast Asia. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2023.12.2.07

- Eni, S. P., & Sudarwani, M. M. (2021). Pemilihan Pusat Pemerintahan dengan Konsep Kota Berkelanjutan Menggunakan Variabel Ekologi Lingkungan. C035–C042. https://doi.org/10.32315/ti.9.c035

- Honzíková, J., Krotký, J., Moc, P., & Fadrhonc, J. (2023). Weather Lore (Pranostika) as Czech Folk Traditions. Heritage, 6(4), 3777–3788. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6040200

- Istianingrum, R., & Retnowaty, R. (2018). Mantra Tipong Tawar dalam Tradisi Upacara Pertanian Dayak Paser sebagai Proyeksi Kehidupan Masyarakat. KULTURISTIK: Jurnal Bahasa Dan Budaya, 2(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.22225/kulturistik.2.1.351

- Kaberry, P. (2002). Malinowski’s Contribution to Fieldwork Methods and the Writing of Ethnography. Routledge.

- Kristanti, R. (2019). Besoyong Dalam Pesta Adat Belian Paser Nondoi di Kabupaten Penajam Paser Utara Kalimantan Timur. Selonding, 14(14). https://doi.org/10.24821/selonding.v14i14.3139

- Lexi Moleong. (2007). Metodologi Penelitian Kualitatif. PT Remaja Rosdakarya.

- Lillo, E., Malaki, A., Alcazar, S. M., Rosales, R., Redoblado, B., Diaz, J. Lou, Pantinople, E., & Nuevo, R. (2022). Composition and diversity of Mangrove species in Camotes Island, Cebu, Philippines. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2022.11.1.11

- Malinowski, B. (1960). A Scientific Theory of Culture and Other Essays. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Malinowski, B. (2014). Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays. Read Books Ltd.

- Mustikawati, A. (2020). Mengungkap Kearifan Lokal Mantra Soyong Masyarakat Paser. Kantor Bahasa Kalimantan Timur, January 2020, 220.

- Mutaqin, D. J., Muslim, M. B., & Rahayu, N. H. (2021). Analisis Konsep Forest City dalam Rencana Pembangunan Ibu Kota Negara. Bappenas Working Papers, 4(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.47266/bwp.v4i1.87

- Nafisah, A. (2021). NONDOI BELIAN TRADITIONAL CULTURE AS A PRESERVATION OF SOCIAL VALUES OF LOCAL CULTURE IN PENAJAM PASER UTARA DISTRICT. ISOLEC Internasional Seminar on Language, Education, and Culture. https://isolec.um.ac.id/proceeding/index.php/issn/article/view/101

- Nosov, D. (2023). How to Defeat a Demon: The Function of the Oirat Folk Narrative About Burning the Female Devil. Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics, 17(1), 126–132. https://doi.org/10.2478/jef-2023-0009

- Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. SAGE Publications.

- Peraturan Daerah (Perda) Kabupaten Penajam Paser Utara Nomor 2 Tahun 2017 tentang Pelestarian dan Perlindungan Adat Paser, (2017). https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/79033/perda-kab-penajam-paser-utara-no-2-tahun-2017

- Perbawasari, S., Sjoraida, D. F., Anisa, R., & Masrina, D. (2022). Sosialisasi Pemanfaatan Mitos dalam Komunikasi Kesehatan kepada Masyarakat Desa Selasari Pangandaran. Amalee: Indonesian Journal of Community Research and Engagement, 3(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.37680/amalee.v3i1.1065

- Piddington, R. (1960). Malinowskis Theory of Needs. In Man and Culture: An Evaluation of the Work of Bronislaw Malinowski.

- Purnani, S. T. (2014). Mitos Asal-Usul Tarian Reog Ponorogo dan Pemanfaatannya sebagai Materi Pembelajaran Sastra di SMA.

- Qiu, Q., Zuo, Y., & Zhang, M. (2022). Intangible Cultural Heritage in Tourism: Research Review and Investigation of Future Agenda. Land, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/land11010139

- Rahayu, N. H. (2022). Safeguard Lingkungan “kota dunia untuk semua.” STANDAR: Better Standard Better Living, 1(2), 52–56.

- Rahman, M. Z., & Pansyah, D. (2019). Pemberdayaan Ekonomi Masyarakat Pesisir Melalui Pemanfaatan Hutan Mangrove untuk Budidaya Kepiting Bakau Desa Eat Mayang Sekotong Timur Lombok Barat. Jurnal Kajian Penelitian & Pengembangan Pendidikan, 7(2), 1–10.

- Risky, P. (2022). Strategi Pengembangan Ekowisata Mangrove Berbasis Masyarakat dalam Menarik Kunjungan Wisatawan di Kampung Baru Kabupaten Penajam Paser Utara. Jurnal Inovasi Penelitian, 3(2), 494–495.

- Strenski, I. (1992). Malinowski and the Work of Myth. In I. Strenski (Ed.), Malinowski and the Work of Myth. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400862801

- Susilo, N., Koestoer, R. H., & Takarina, N. D. (2023). Disclosure of mangrove conservation policies in SEA: Bibliometric content perspectives. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2023.12.2.08

- Sutrisno, H. (2004). Metodelogi Research 2. Yayasan Penerbit Fakultas Psikologi.

- Urry, J. (1995). A History of Field Method. In Ethnographic Research: A Guide to General Conduct (Vol. 175, Issue 5, pp. 313–314). Academic Press Limited. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198705000-00016

- Waitt, G. (1999). Se faisant naturaliser le primitif. Tourism Geographies, 1(2), 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616689908721306

- Yasser, M., Hendri, Simarangkir, O. R., Irawan, A., & Sari, L. I. (2021). Indeks Nilai Penting Ekosistem Mangrove di Kelurahan Kampung Baru Kecamatan Penajam Kabupaten Penajam Paser Utara. Berkala Perikanan Terubuk, 49(2), 1122–1130.