Art and the Senses for Ocean Conservation

Abstract

This paper considers the role of art in ocean conservation. Drawing on the presentations and work of two artists featured in the One Ocean Hub Art and Emotions webinar hosted during the UN World Ocean Week, the paper focuses specifically on the sensorial nature of art and of human beings and the role that art can play in advancing ocean conservation. The main argument offered is that ocean conservation plans and policies should consider the importance of humans to ocean conservation, the importance of human artistic endeavour to ocean activism and finally the importance of the sensory to human experience. Acknowledging and recognising the importance of human sensory experience in relation to the sea, can nuance existing discourses of ocean use and benefits, revealing human priorities and potential obstacles to conservation. Third, by leveraging human sensory expression through art, ocean conservation advocates may be able to refine and produce more effective communication for ocean conservation. Finally, recognising the sensory (and the artistic) is key to reorienting humanity as it enters a post-anthropocentric age, marked by dramatic ecological change.

Keywords

Ocean Conservation, Sustainable Development Goals, Sensory Ethnography and Art

Introduction

According to Rayner, Jolly and Gouldman (2019: Abstract), “The ocean economy is large and diverse, accounting for around US$1.5 trillion of global gross value-added economic activity. This is projected to more than double by 2030.” The success of the ocean economy however, and achievement of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 (United Nations 2015b), depends on timely mitigation of environmental impacts on the oceans. In this regard, the European Union Agenda 2030, the African Union Agenda 2063 and the regional preparatory meeting of the Pacific Island’s Forum in 2020, all endorse the importance of conserving the oceans for future generations. Africa’s Agenda 2063 (2015: 3) specifically states that the Blue Economy:

…shall be a major contributor to continental transformation and growth, through knowledge on marine and aquatic biotechnology, the growth of an Africa-wide shipping industry, the development of sea, river and lake transport and fishing; and exploitation and beneficiation of deep sea mineral and other resources.

While one cannot deny the importance of sustainable ‘use’ of the oceans for economic benefit, the current international agenda for the oceans tends to focus on the delineation and exploitation of oceanic resources. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) for example, provides a comprehensive legal framework addressing the demarcation, management and policing of the world’s oceans (Vrancken and Tsamenyi 2017). But as Ifesinachi, Nelly, Nelson, Uku, Elegbede, and Adewumi emphasise, such demarcations and “large scale BE initiatives prioritize economic gains at the expense of environmental degradation and the exclusion of local communities”, (Ifesinachi et al. 2020: Abstract). Like Gee however, this article argues that, the “…oceans are also social spaces, communication spaces, and cultural spaces—and they play an important role in how we as humans understand ourselves as communities and individuals”, (Gee 2019: 24) and:

…there are fundamentally different ways of seeing the ocean. The first is the practice of regarding the ocean as a collection of material, tangible entities, resulting in particular spaces composed of physical-material facts—such as ocean currents, water depth, water temperature, and flora and fauna. The second is the understanding of the ocean as a visual phenomenon, referring to the appearance of the ocean as we see it. The third…is the sea not as a space but as a place— moreover, a place that can generate deep-seated attachment and with this, care. (Gee 2019: 38)

Thus, the oceans are (as Deloughrey, Neimanis and others cited further on show), much more than an exploitable resource. They contribute to and advance human artistic and sensory experience of the ocean and alternatively grounded ethics of conservation. Thus, in this article, I call for the foregrounding of artistic, indigenous and sensory discourses on ocean management for long-term ocean sustainability and the democratisation of ocean ‘use’.

The discussion presented shows that the oceans and coasts are matrices through which humans share complex, emotive and sensory experiences of the natural environment. Humans use aesthetic communicative practices (fine art and sculpture) to communicate their engagement with and experiences of the oceans and coasts. Emotive and aesthetically stirring, the art produced intends to elicit sentiment (i.e. nostalgia, sadness) and has the potential to advance conservation-oriented behavioural change. The art produced also stimulates alternative narratives of the oceans and coasts, challenging universalising, ungendered, hegemonic and secular policies.

Inspired by Escobar’s (2018) concept of a global ‘pluriverse of knowledges’, the article considers the UN’s construction of inclusion and diversity and its implication for Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14, Life below Water. A brief critique of SDG 14 is offered, noting its focus on natural science approaches to ocean conservation. The discussion shifts attention to emerging ‘wet ontologies’, analytical framings of the oceanic, which in inspire and in part, showcase human aesthetic and sensory engagement with the oceans. Presently, these ‘wet ontologies’ consider the ocean’s symbolic aspects, human biological connection with the oceans and water, feminine metaphors of the sea and the role of the oceans and seas in shaping historical and political experiences. By considering the aesthetic and sensory, this article adds to these discussions, foregrounding human bio-cultural engagement with the oceans and coasts, as well as the possibilities of such engagement for the conservation of these natural assets.

A Pluriverse of Knowledges

Mignolo (2012) and de Sousa Santos (2014) have long advocated for a radical transformation of society, perceiving such change as necessary to the restoration of marginalised epistemologies and peoples. For such change to take place, or at least, for greater equality to prevail, they argue that there is urgent need to acknowledge, recognise and foreground our collective ‘pluriverse of knowledges’. Reviewing pertinent literature, it is proposed in this article that despite calls for the inclusion of culture in sustainable development initiatives, UN SDG 14, as well as its targets and indicators are overly focused on natural science means to address ocean conservation. Moreover, references to the inclusion of indigenous peoples and perspectives in development (and ultimately ocean conservation) remain primordial, failing to consider the hybridisation of populations and the multiply situated perspectives and epistemologies which they produce. The emergence of art and humanities research on human/social interaction with the oceans and seas, are therefore important as these emphasise shifting, intersubjective as well as culturally situated identities.

A Scientific Sustainable Development?

In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development released a report entitled Our Common Future (World Commission on the Environment and Development 1987). The report defined sustainable development and discussed why it is globally imperative. Now commonly referred to as the Brundtland Report, the document states that sustainable development is ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’. The Brundtland Report was not however, the first word on sustainable development. Swain (2017: 3) notes that “About 56 years ago, the OECD Convention (Article 1), targeted Sustainable Development, to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in member countries, while maintaining financial stability, and contributing to the development of the world economy. By the early 1970s OECD began to focus on all three pillars: economic, social and environmental.” He further adds that,

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), were the dominating development paradigm at the beginning of this century. With the MDGs approaching 2015, the Rio+20 summit in 2012, set up an Open Working Group (OWG) with representatives from UN member countries that was mandated to create a draft set of goals. The objective of these goals was to provide continuity to the MDGs and motivate policymaking on both the national and local scale towards sustainability. Unlike the MDGs that had been criticized for being set in an ad hoc, insulated manner, the SDGs are a result of the largest consultation process, resulting in 17 main goals and 169 sub-targets…that were unanimously approved in September 2015. (Swain: Ibid)

With regards to SDG 14, ten targets and ten indicators are identified. The targets are:

- Reduce marine pollution

- Protect and restore ecosystems

- Reduce ocean acidification

- Sustainable fishing

- Conserve coastal and marine areas

- End subsidies contributing to overfishing

- Increase the economic benefits from sustainable use of marine resources

- Increase scientific knowledge, research and technology for ocean health

- Support small scale fishers

- Implement and enforce international sea law

Swain indicates that the SDGs have been heavily criticised for being too broad and difficult to implement. This is especially concerning when one considers that the aim of the SDGs in general, is to advance democracy and inclusion, and to end poverty. Reflecting on the targets of SDG 14, I would add that the SDG is not only broad, it advocates mostly for the use of natural science to address ocean conservation issues. The broadness of it also creates an impression that ‘inclusion’ is a relatively simple and politically uncomplicated process.

As I show in the following discussion, there is deep history of human engagement, as well as complex creativity and materiality that makes inclusion a multidimensional and thoroughly complex process. The earliest modern humans lived on and traversed the coasts of southern Africa, there is strong evidence of pre-Socratic and early Greek cosmological philosophies of the place of the oceans in a human-divine universe and more recently, ethnography of human efforts to traverse the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, and of transoceanic slave trades and imperialist naval battles. The oceans have always featured in human history, cosmology, sustenance and artistic expression. This ‘pluriverse of knowledges’ and the experiences, ideas and material culture produced are hardly noted in the SDGs.

For decades already, indigenes have responded to international development efforts to ‘include’. Many have called for the inclusion of culture in development (World Secretariat of UCLG 2013), while others have pursued decolonisation and the decolonisation of knowledge tout court (Steinman 2016: 219-236). Considering indigenous conceptions of nature and university in the Amazon, Arias (2019: 1) states that, there, “parity, complementarity, cosmological, community life, respect and ritualism”, define orientations to nature and the universe. In making this statement, Arias indicates not only that indigenes in the Amazon share philosophies of conservation; they also share in this philosophy with other indigenes worldwide.

The International Congress in Hangzhou, China (UNESCO 2013), further emphasised the importance of including culture to achieve meaningful, long-lasting change. In this document, culture was used to refer to groups with well-defined ‘traditions’, values and practices. However, SDG 14, its ten targets and indicators make no mention of culture. Henderson (2019: 6) states that, “as people and communities remain at the centre of development, there is a growing awareness that the arts, humanities and social sciences have a key role to play in the development of effective [ocean] management strategies, especially if those strategies are going to be sustainable”.

The presence of people but lesser focus on culture challenge inclusivity and ultimately effective ocean conservation research. Marine spatial planners, whose contribution is highly relevant to the achievement of SDG 14, are now seeking ways in which to include a diversity of knowledge forms and stakeholders in ocean conservation. Equally, fisheries programmes are acknowledging the importance of cultural traditions and behavioural change on fish stocks and marine biodiversity. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations 2015a) provides the next feasible opportunity for member states to reconsider and refine the SDGs. The 2030 Agenda is more focused on human development goals and if more nuanced understandings of culture and inclusion are added to it, the agenda will be better placed to achieve an inclusive conservation approach to managing the future that lies ahead.

Watery Futures and Sensory States

Deloughrey and others noted in this article, propose that Earth’s future is a ‘watery’ one, as the world will be affected by sea-level rise, climate and weather change brought about by fundamental changes in the world’s ecosystems. Sensory ethnography documents evolving, intricate, sense-influenced human behaviours in culturally defined landscapes. The work also critiques disregard for the senses and advocates for the democracy of the senses and ultimately, the democratisation of global society (Howes 2003).

Attention to the sensory emerged after the ‘ethnographic turn’ in anthropology, as researchers came to realise that their seemingly ‘objective’ research was extractive and oppressive (Clifford and Marcus 1986). A conclusion reached, is that all humans are subjective, living, sensory beings and social encounters are intersubjective and political, producing a sort of ‘participant-sensation’ (Laplantine 2015). The feminisation, decolonisation and de-territorialization of the social sciences deepened the discussion, drawing attention to the sensual, contingent, gendered and transversal nature of human existence, as well as humanity’s sensory history.

In recent times, climate change and increasing inequality has further focused attention on human values and the ways in which these influence conservation. Linking biology, culture and values, Rock, Sima and Knapen (2019) state that, “Although well advanced in terrestrial environments, we are only just beginning to consider how human values are to be understood in the context of socio-economic and environmental management of marine spaces” (Rock et al. 2019: 1). And that:

…we need to more actively acknowledge the diversity of human relationships with the ocean – both personal and collective, historical and contemporary… understanding our changing relationship with the ocean is critical for future decision-making processes about sustainable marine management of its resources, ecosystem services, and wider dimension of health.’ (ibid: 1)

Hayward (2012) proposes further refinement, specifically that we conceptualise island societies and places located in waterways and along coasts and peninsulas, as aquapelagos. These are multispecies and transmaterial spaces constituted by human interaction in a combined terrestrial and aquatic environment (Hayward 2012: 3). Such spaces produce unique possibilities for interaction and ultimately human perception and experience of aquapelagic worlds. Citing Bennett (2010:iii), Hayward argues that humans interact with other ‘vibrant’ matter in their environments and that a ‘vibrant materiality’ co-exists with humans. This materiality is active, responsive and equally shaping human experiences. By offering the concept of aquapelagos, Hayward encourages a view of aquatic environments and of human societies in them as integrated and mutually implicating. The concept also contributes to Escobar’s (2018) argument for a pluriverse of knowledges, as Hayward’s concept suggests that epistemologies are not merely produced by humans but that knowledge foundations exist beyond human intention and are apparent in agential material and immaterial forms.

The idea of Earth and its species as a functional, symbiotic whole was first elaborated in natural science via Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis (Lovelock 2009). Thoroughly debated, the hypothesis was adopted and reflected in the Amsterdam Declaration and subsequent agreements for terrestrial conservation. Similar ideas have found purchase in the environmental non-governmental organizations noted by Hamilton Faris (2019) but have yet to percolate into global ocean conservation policy.

The situation is difficult to comprehend because scholars have been discussing the natural condition of humankind for some time. Laplantine (2015) called for an end to categorical thinking and the complete separation of humans from nature and their natural selves. Deloughrey (2017: 34) has documented the rise of transoceanic and oceanic imaginaries, tied to the de-territorialization of thinking, climate change and the inevitability of ‘watery futures’. A multispecies, post-human, post-linear concept of time was emerging, calling for new ways of thinking about human relations with the oceans and seas. Deloughrey says, that:

No longer relegated to aqua nullius, the ocean is now understood in terms of its agency, its anthropogenic pollution and acidity, and its interspecies ontologies — all of which suggest that climate change is shaping new oceanic imaginaries’ (Deloughrey 2017: 34).

Articulating a humanities paradigm for analysing life with water (as opposed to a scientific analysis of life below water), scholars approached the oceans as both matter and archive (Neimanis 2012), visibly observed, constituting history and global relations and yet, also as a substance within us, producing a ‘Hypersea’ (Schulte Mcmenamin and Mcnemanin 1996).

Reflecting on the post-human multispecies world, Braidotti states that:

Humanity [is now] re-created as a negative category, held together by shared vulnerability and the spectre of extinction … struck down by environmental devastation, by new and old epidemics, in endless ‘new’ wars, in the proliferation of migrations and exodus, detention camps and refugees’ centres.’ (Braidotti 2016: 17)

The recasting of humans as a vulnerable common-place species caught in new futures involving pandemics and new modes of multispecies engagement, emphasise their embodied nature and call for attention to different kinds of diversity. Bringing these thoughts together, it can be said that humanity is at a particular juncture in the consideration of itself, and its place in the world. No longer perceiving themselves as omnipresent or separate from nature, humans (especially in the West) are now conceding that they may be an integral part of nature and that resolving the environmental crisis may involve deeper and wider considerations than that which appears in international development policy. Because of the shifting situation, this article, in part argues that the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development needs amendments to its principles, targets and indicators for the meaningful and ecologically relevant inclusion of all humans in the global conservation endeavour. Attention to inclusion and multidimensional nature of human beings is important to effective and sustainable conservation efforts.

In the following part of the article, two artistic lenses are offered, through which I consider the ways in which a sensory experience and environmental conservation are pursued. It is proposed that art is a culturally and socially situated communicative practice that elicits a range of human sensory experiences to compel diverse perceptions, experiences of and responses to conservation. To frame the findings, I use a reflexive ethnography and sensory analysis to consider how the artists and their art forms convey information about human relations with the sea and my own responses to these art forms. A preliminary conclusion is that those who are not in policy circles, engage with the issue and advancement of ocean conservation differently, through diverse media, not just text and talk.

Fine art and Sculpture

In June 2020, celebrating the United Nation’s World Oceans Week, the One Ocean Hub a UK Grand Challenges Research Project, launched a webinar entitled the Art and Emotions. The aim of the webinar was to introduce development professionals and a general global audience to the interconnections of art and emotions and the role of art in ocean conservation. The event was attended by hundreds of participants across the globe. The data collected for this article is partly based on the webinar and information derived from two of the artists. Secondary data is also scrutinised in relation to the work of Yahgulanaas and Nuku. The data is analysed partly by using the reflexive ethnographic approach, which is that the author considers her own subjective responses to the artwork, as well as the responses of audience members.

The two artists whose work is analysed here are: Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, an artist and elder of the Haida community in Canada and George Nuku, a Maori sculptor. Considered in general terms, the artists demonstrate that art can and does easily elicit a range of human emotions, galvanising people to become more mindful about environmental activism and ocean conservation. However, as proposed here the work elicits much more than emotional response, it provides insight into differently conceived worlds, suggesting possible entry points for international bodies such as the UN as they seek to engage with a pluriverse of knowledge forms for ocean conservation. A brief overview of Haida and Maori histories and cultures is necessary before proceeding to the interviews and further analysis.

Oceanic Indigenous Peoples: The Haida and Maori

The Haida peoples have occupied what is today known as the archipelagos of the Queen Charlotte Islands of Canada and southern parts of the Prince Wales Islands in Alaska for more than 10,000 years. Haida culture is rich, complex and artistic. Historical accounts of the Haida draw attention to their ceremonial ritual known as the Potlatch, a series of events that involved the amassing and distribution of goods and property mostly by ‘high-caste’ villagers related to the chief’s family. The Haida are described as exogamous and historically participating in a communal lifestyle. Being blessed by an abundance of seafood, the Haida participated in sea otter and fur seal hunts, smoking and storing salmon and other fish in elaborate bentwood boxes for the lean winter months.

European settlement and war against the Haida in the 1800s, led to the devastation of the population. European diseases afflicted the Haida and forced them to leave their ancestral villages. The Christian European settlers also banned the Potlatch rituals, as they associated these with pagan beliefs. Subsequently, totem poles, also associated with the Potlatch, diminished (Porter 2017). Fewer people were involved in the carving of totem poles and bentwood boxes. In the late 1800s however, Chief Albert Edward Edenshaw and subsequently, Charles Edenshaw (his son), revived the art of carving and other artistic forms. Michael Nicoll Yaghulanaas, the artist interviewed for this paper is the grandson of Charles Edenshaw (Canadian Museum of History, online).

The Haida are archetypally aquapelagic (Hayward 2012). As already stated, they historically led a rich aquapelagic existence, fishing, fur seal hunting, subsisting on a variety of marine sea life and creating from this existence with the sea, a complex narrative and artistry that indicates the symbiosis of humans, marine life and immaterial things.

Although critiqued for producing an overly homogeneous view of complex social groups and identities, the work of the anthropologist, Alfred L. Kroeber notes that the Northwest peoples, including the Haida, have several characteristics in common with the world’s oceanic indigenous peoples. The latter include the Maori. These characteristics include, ceremonial exchanges and distributions of goods and property, as well as elaborate carvings to represent their tangible and intangible cultural heritage.

The Maori arrived in New Zealand from Eastern Polynesia about 700 years ago. Historical and ethnographic sources indicate that like the Haida, they also cultivate a rich artistic tangible and intangible heritage. Their master carvers who are only men, are known as tohunga whakairo. From 1840-1891 the Maori were decimated by infectious European diseases (Pool 2011). These affected the mortality rates of the people in far greater numbers than war (specifically the Musket Wars) and the imposition of European systems of rule and law. The lands of the Maori were also ‘confiscated’ and ‘bought’ by the settler government, such that by 1939, very little land was left to the indigenous people (Orange 2001). Since the 1980s, the Maori have been reviving traditional Maori art in the form of carving (whakairo), weaving, group performance, oratory and tattooing. They have also nurtured important intangible cultural heritage in their beliefs and symbolism. Similar to the Haida, there was a strong practice of exchange and distribution among the Maori and the ritual process was guided by the principle of utu (generally described as balance), exhorting participants to continue social obligations so as to maintain social bonds. Of relevance to this paper, is the Maori principle of guardianship or protection of the environment. Master craftsmen, such as George Nuku, whose work is discussed in the article, would be perceived as an individual who promotes the principle of utu (environmental guardianship), while receiving messages from the Gods, as to what and how he should carve.

Engaging several months after the One Ocean Hub and UN Ocean Week webinar, I asked artist and sculptor, Yahgulanaas the following questions (noted in italics). Further on, I combine my consideration of his work with an analysis the interview with the artist.

What (if any) emotions does the sea or ocean evoke for you? And why? He answered:

An undercurrent of anxiety is a new emotion [I now feel] and it is tied directly to the heavy weight imposed by humans.

My next question was, what is your earliest sensory memory of the sea or ocean? To which he stated:

The stretch of open horizon revealing its taut tension against the atmosphere.

Secondly the way the ocean pressed up against our house and trickled into under the floorboards.

For the third question, I wanted to know if, in his view, the sea has an emotive effect on humans and if so, why? To which he added:

A human default seems to be that we are afraid of what we don't understand.

Our complex relationship to the vast surface of these hidden depths is nuanced with awe, fear and hesitation. In stark contrast to our personal sense of the small, the Ocean presents as a generous entity and yet ever mysterious and changeable we express a full range of emotions.

Reflecting on his childhood and the potential impact of a childhood close to the sea, I asked, what did you learn about the role of the sea and nature in peoples’ lives? He answered:

A good life for humans requires a good life for the ocean. Insofar as the Haida are concerned…in our constant efforts to buffer against the caustic embrace of a nation state we persistently express that we are the humans duty bound to defend these waters.

Desiring to know more about Yahgulanaas’ invocation of the sensory in his work, I asked: What is the role of art in evoking human sentiment and senses (touch of sculpture, visual of paintings, scent of wood, sound of poetry) and if its important, why do you think it’s important? To which he answered:

My practice seeks to avoid instructions and rules by using gentle techniques that elicit engagement by observers. Creating space for the observer to find their own relationship encourages a personal connection that is not arbitrated or filter by invested intermediaries.

My last question to him was why had he decided to create Haida Manga? What is unique, valuable and/or important about the genre for our times? He answered:

Haida [is a] merger with Asian manga…During the earlier days, European racism was overt to all. It wasn’t disguised. Cafes had signs “No Dogs, No Indians” etc. Where there wasn’t a sign there was a rule. Indians couldn’t sit with Whites in a cinema. My 92 year-old aunt as a teenager sat out of place and would not move eventually forcing the cinema to run the movie. For her grandfather and other Haida sailors who were part of the pelagic fur seal hunt that followed the herds across the north pacific we learned that Japan was a welcoming place. Hakodate on Hokkaida Island (1891) was a place where Haidas could walk freely amongst others as full human beings. Haida manga is a salute to those types of relationships.

After this, Yahgulanaas referred me to the recent activism of the Gaandlee Guu Jaalang (Daughters of the Rivers), Haida women who upheld Haida law by occupying two ancient villages to stop a pair of luxury resorts from opening during the pandemic and allowing an influx of potentially infected visitors onto their island (Dunphy 2020). Continuing to respond to me, Yahgulanaas said that, “Collaboration and cooperation between indigenous and neo liberal institutions is rare, this type of defensive energy is not the only strategy to protect the Ocean.” Yahgulanaas directs attention to the fact that, in April 2008:

The SGaan Kinghlas–Bowie Seamount and the surrounding area have been designated by both the Haida Nation and the Government of Canada as a protected area… the area was officially designated as a Marine Protected Area (MPA) under Canada’s Oceans Act. The purpose of the MPA is to conserve and protect the unique biodiversity and biological productivity of the area’s marine ecosystem, which includes the SGaan Kinghlas–Bowie, Hodgkins and Davidson seamounts and the surrounding waters, seabed and subsoil. (Council of the Haida Nation and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2019: 1)

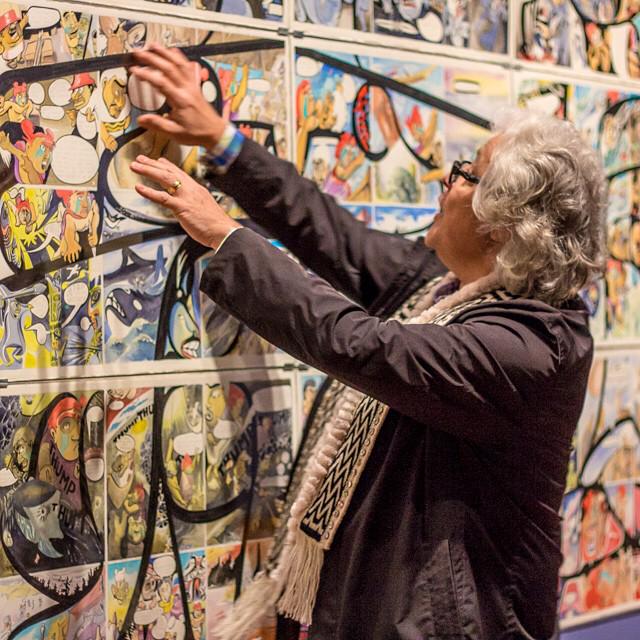

Yahgulanaas has a deep history of environmental activism and political involvement, which is intertwined with his role as member of the Council of the Haida Nation, a nation that has been in the making for more than 10,000 years. His approach to environmental activism is cosmopolitan (it considers Japanese and Haida narrative styles and symbols) and contemporaneous, he uses the manga genre. In his parable of the hummingbird abating a raging fire by carrying drops of water in its tiny beak, Yahgulanaas (2008) conveys a powerful message of how even the least important can effect change in the world and that, other species have a role to play in changing our collective environmental fate. The agency perceived in the hummingbird appears elsewhere in his work. In the much analysed Red: A Haida Manga (Yahgulanaas 2009) several issues and messages emerge that compel a consideration of the depth and richness of the pluriverse to which Escobar has alluded to.

The work depicts the multifaceted and diversely situated nature of the ocean, its holding of sea life and of humanity’s intimate relationship with nature. In this regard, the artist partly articulates Hayward’s aquapelagos in visual form, for Yahgulanaas’ work signals the mutually implicating assemblages of territorial and aquatic spaces, the changeability of the ocean and the agency and mutuality of people and things across time and space. All of this happens in (what on the surface), appears to be a natural world where time marches forward in a linear fashion.

The artist’s work consists of multiple layers. Reflecting on it, Harrison (2016) states that Red showcases the interplay and symbiosis of diverse planetary states and entities -- air, water, humans, plants. The gutter, a usually white border space that imposes order on the comic or written script is displaced and subverted. In indigenous comics (such as the Haida manga), “tensions between indigenous concepts of space and time [find expression]…for the indigenous worldview, the whole is everything and everywhere [the comic is a] visual representation of a worldview for which individual action is always an extension of the greater forces that join all things together.” (Harrison 2016: online). In Red, Yahgulanaas uses a black, undulating ‘border’ that penetrates, flows alongside, serves as a gutter that intervenes in the narrative conveyed.

Reflecting on the work in a recorded interview, Yahgulanaas speaks about the undulating border by saying that, ‘we are living in a huge narrative that even we, cannot comprehend… [in it] there are no vacuous, white [oppressive?] spaces.” (Yahgulanaas 2015: Online). In stating this (and bringing the undulating gutter into his art), he simultaneously alludes to the overlapping of various layers of reality: (1) the incomprehensible universe which we have yet to apprehend (2) the fact of imperial and colonial violence and (3) intertwining of these known and unknown realities.

In Red: A Haida Manga, there is also inscription of clan specific frames usually seen on Haida bentwood ceremonial chests. These frames are filled with storied images that collectively depict both a collapsing of time and the cradling of personal and community stories within the grand and deep time narrative of the clan. The latter is significant to a rethinking of ocean conservation as it encourages the reframing of conservation discourses, shifting perspective from a more western, linear conceptions of time and monoculture narrative, to decentralised, multiple, deep time frames and multicultural perspectives. In my interview with him, Yahgulanaas spoke about the ocean as being part of this incomprehensible (and yet generous) vastness, urging all to approach it (and nature) with awe.

Yahgulanaas also compels us to engage with the specificity of Haida cultural frames, its’ epistemologies and ways of seeing the world, publicly foregrounding these as valuable, contemporary and timeless. The message is not just for ‘outsiders’ but for insiders too, as narrative reconstitutes potentially fractured indigenous identity, allowing indigenes to retell their stories and to reframe such stories, foregrounding values, perspectives, characters and myth that is important to local communities. Thus, Carnes (2020: 142-45) states,

There are definitive ways in which contemporary creators can thwart, and even begin decolonizing, these stories. After all, if decolonization is an embodied practice that must rework societies from the ground up, as many scholars in Indigenous studies argue, then perhaps the first thing we must do is rework the current ways we approach history and historicization to think through multiple histories and various futures for us all.

Indigenous comics offer the most radical example of historical dissidence I have explored thus far precisely because they are not only working to deepen issues of temporality and spatiality but also because, through that work, they are calling into question larger structures of settler dominance and continued Indigenous oppression.

Further reflections on the ‘content’ of Yahgulanaas’ work reveal the questioning of settler dominance in the artist’s play with concealment and revelation. In a Ted talk presentation (Yahgulanaas 2020: Online), the artist tells us that the ancient name of Haida Gwaii itself, means “coming out of concealment”. It is possible perceive a link between the stated ancient name of the people and the hidden presence of the clan frames in Red. The clan frames are concealed in plain sight symbolising the collective wisdom of the Haida as a constant that literally frames and guides evolving stories of conservation in the community. It could be said that the images (the stories within the ‘frames’ included), reflect the status of the Haida and possibly other similarly placed indigenous peoples. In a westernised socioeconomic and political world, the wisdom of indigenous peoples is routinely invisibilized, their worldviews deemed ‘out of place’ and ‘in the past’ and are therefore (conveniently) deemed unworthy of scrutiny and inclusion.

In my interview with him, Yahgulanaas also proposes that the observer must encounter the narrative for themselves. Emotional response to the work cannot be predetermined by the artist. Each person must arrive at the work and take from it that which they consider to be meaningful. In this regard, those who see the work engage in what Norberg-Schulz (1980: 185) calls “creative participation”, which helps to reveal one’s existential purpose.

Non-direction is then, another equally important message to ocean conservationists. It suggests that there is both grand and personal narrative guiding human action and interaction with nature. Presently, secular (and institutionally grounded) interpretations of ocean conservation prevail. The spiritual, mythological and personal connection of human beings to nature is barely acknowledged let alone included in analytic frames. Yahgulanaas’ tale of the hummingbird who witnesses the forest fire and does what it can to remedy the situation offers both spirit and myth, reinstating the value of the spiritual and mythical to conservation.

The artist also challenges what many would consider the ‘normal’ progression of a narrative. In his work, mythology, biology, culture and politics collide and coexist. He seeks to challenge myths and generalisations perpetuated by historical oppressors, specifically the myth of cultural difference, the castigation of hybridity and the silencing of violence perpetrated against indigenous peoples. Reflecting on this, Carnes (2020) states that Red: A Haida Manga among others, “rely on a flexible understanding of how time works, how narratives progress and what it means to tell a story…thus comic forms actually encourage readers to question their own experiences of western, imperial, or heteronormative histories” (Carnes 2020: ii-iii).

Finally, the interview with Yahgulanaas encourages a questioning of the role of humans in the natural environment. The oceans are in our memories eliciting tactile remembrances of the tide creeping in under floorboards. The oceans are also on our shoulders, pressing us down as it were, making us anxious of a watery future that might overwhelm. The ocean is also its own unique entity, its own atmosphere (as Deloughrey says), inducing physical discomfort for humans who need air to survive. Thus, we are not rational beings acting on the oceans and other fragile natural environments to ‘save’ them. We are embodied beings who are irrevocably part of the natural environment. In this regard, ‘saving’ the oceans is an act of actively saving ourselves. This is not an egotistical journey though, we exist in a world where “vibrant materialities” persist, guide, inform and act alongside us, situating us as beings who are part of a still unknown cosmos. Both Yahgulanaas and Nuku encourage other ways of knowing and seeing the earth and its oceans by differently conceptualising and perceiving time, materials and borders. Various layers of meaning and symbolism appear in their work and these subvert existing perceptions of conservation and of ‘accepted’ reality.

To date, the dominant frames for knowing and understanding the aquapelagic are situated in Western concepts of the natural and political. Emphasis is placed on the two hundred nautical miles beyond the national jurisdiction for ocean’s governance, the relevance of biodiversity in the benthic zone, dwindling fish stocks and its implications for coastal livelihoods and the importance of marine biodiversity in estuaries and other shallow waters. While humans definitely feature in these narratives, their unique, culturally influenced and historically shaped interactions (including sensory interactions) with water/the oceans is missing. Humans are often constructed as either foes or victims of ocean management, pawns in a complex game of international development imperatives and conventions for global development. Their fleshly bodies, their embedding in the natural world and their implication in it and shifting temporal frames, is hardly considered.

Yahgulanaas is not the only one invoking transoceanic alliances, temporal shifts and contrapuntal forms of representation. George Nuku, a Maori sculptor who was also part of the panel, makes a strong case for the role of feelings in creativity and in humanity’s relationship with the environment. Presenting his thoughts on different platforms (Nuku 2016a & b), Nuku has expressed that the importance of the tactile in sculpting. Reflecting on an exhibition in the New Zealand ‘room’ in Venice, Nuku said,

For me, making these art works and having these art works is the same feeling as falling in love. If you have an honest, open channel of love, of communication flowing with nature and the world around you, it looks after you in kind. (Nuku 2016b)

Nuku adds that he wants people to, “hear it, feel it [to] watch the polystyrene dancing”, (Nuku 2016a). Talking about his exhibition Bottled Ocean, an exhibition used to educate children about the place of plastic in ocean pollution and in the world, Nuku says the creative process was collaborative, involving ‘slaves of love’ — family committed to seeing the work completed (Nuku 2016b). For him, the most important lesson of the exhibition is that people ‘feel something’ when they see the work.

Engaging with plastic, he says, is acknowledgement that plastic has changed humanity. As a result of this change and the proliferation of plastic in the ocean, humans need to change their relationship with the ocean. Such a change involves ‘mutation’, the radical transformation of a person into something that they were not before. Nuku adds that the media he works with, polystyrene and plexiglass, speak to him and compel particular motifs and that he feels at one with the materials as he works. In this, it can be ascertained that for the artist, there is not only the concern to use one’s art to advance sensory identification but also to personally use art to achieve a form of trans-materiality and trans-temporality. The artist-human is no longer a vulnerable being, but a mutated one capable of reconnection with the ancestral world (Nuku 2016a). Thus, Nuku concedes that he has mutated because of his art. Part of him is plastic, since plastic is everywhere in the world.

Furthermore, for him, although manmade, plastic is sacred, since for the Maori, all things created and of Earth, are sacred. Nuku’s relation to plastic up-ends conventional thought about the material. He treats it as a source of inspiration and as a malleable substance that does not alienate him from his past or future. Like Yahgulanaas, Nuku acknowledges and credits his indigenous roots for his profound relationship with the ocean. The Maori world offers him a different conception of time to what is believed to exist in the Western world.

Mindful of the visible, looming ecological crisis and the diminishment of the oceans, he sees the unfolding story as a call to adapt, which he is doing by engaging with seemingly offensive substances, plastic and remaining rooted in his roots. He says that, Maoris, “…are walking into time backwards. The past is in front of you”, (Nuku 2016b). An earlier reflection of Nuku’s on his past reveals the continued marginalization of indigenous peoples and perspectives,

Throughout all the stages and changes in my life, art has always been a constant desire and companion. Looking back, I can honestly say that it is all self-portraiture, all of it, in all its wealth. I grew up in New Zealand in an environment surrounded by unfulfilled men; I saw Maori political, social and cultural aspirations thwarted or met with utter indifference which eventuates in self-oppression. These challenges eventually pushed me to establish a psychic ultimatum within myself: either to go forth and risk complete failure, or be buried by the misunderstanding at home. (Nuku 2011: 68)

He also articulates the “vibrant materiality” of the Perspex (Nuku 2011: 68-69), saying that,

The perspex is scary right now and has been over the course of the past five years. It is operating on so many different levels-both horizontally and vertically. I will continue to make self-portraiture with perspex. It is as if the perspex communes or communicates with me. I have the sensation or feeling of becoming perspex. The very tip of my spear, the tira, is perspex. The planes, edges and forms are wrestling with the light itself. Its translucency gives me an entirely unprecedented thrustal movement. I say I am becoming fluent in perspex and must make the plastic dance and sing.

Hamilton Faris (2019) argues that ocean activists can develop hydro-ontological frameworks from which to advance climate justice activism. Hamilton Faris considers the performance of two poets from different but similarly affected ecological niches, who in embodied and verbal ways speak to issues in the global climate crisis. Although the poets are objectively exotified and their presence articulated as a trope of islanders vulnerable to climate change, Hamilton Faris argues that they are agents in their own right, articulating an indigenous solidarity by sharing their common plight with the world. The poet sisters are not ventriloquists for the western (created) crisis of nature (Farbotko and Lazarus 2012: 383). They articulate what Susan Sontag (1966) has termed an “aesthetic of disaster” (Hamilton Faris 2019:80) to appeal to the emotional sensibilities (and imperialised nostalgia) of an ostensibly western audience. However, the ‘ritual’ they perform also simultaneously provides “contrapuntal systems of representation…to rupture…scopic regimes even from within them” (2019:81). In responding by facing each other and the world, they “respond self-consciously to their exotified but nonetheless agential position within the eco-cosmopolitan scopic regime” (Hamilton Faris 2019: 81).

Reflecting on the work of both Yahgulanaas and Nuku, I would argue that we have two artists who may appear forced to engage with the environmental documentary gaze and are at risk of being exotified and commoditised as part of a disenfranchised humanity (Hamilton Faris 2019). However, their work is so multivalent and subversive of the colonial/settler regime that it defies easy circumscription and challenges these “scopic regimes even from within them” (Ibid). Both Nuku and Yahgulanaas are engaging hydro-ontologies but they are also working with agential immaterial forms (paper, brush, Perspex) to challenge the very boundaries of humanness. What we can take from their work is that there is no formula, set of targets, indicators that can sufficiently contain the diversity of cultural and sensory engagements with ocean conservation.

The work of Yahgulanaas and Nuku have reached a wide, global and regional audience. Their work is critical to eliciting feeling regarding the oceans, coasts and their conservation. The work is engaged by Haida social groups, by children learning about environmental and ocean conservation, by lovers, women and indigenous people and by a global audience of art appreciators. The ‘reach’ of art and the role of art in all spheres of human existence, is underrated. Reflecting on the value of art, Gablik (1995: 7) says,

The need for a reframing of the modern world-view and its assumptions in order to forecast the next step for society has been recognized in many professional spheres; within the art world, however, it has, as yet, not established correlative. The necessity for art to transform its goals and become accountable in the planetary whole is incompatible with aesthetic attitudes still predicated on the late-modernist assumptions that art has no ‘useful’ role to play in the larger sphere of things. But the fact is that many artists now conceive their roles with a different sense of purpose than current aesthetic models sanction, even though there is as yet no comprehensive theory or framework to encompass what they are doing.

Indicators of Success?

How persuasive is art and the sensory in compelling audience members and ordinary people to give attention to ocean conservation? Reflecting on the webinar event convened by the One Ocean Hub, it is reported that the event reached 8163 people besides any additional advertising done by the individual researchers or members of the event team.

Describing the event, the One Ocean Hub states:

Art, in all its forms, has an important role to play in global decisions about integrated and inclusive ocean governance. Creative practices offer opportunities to share multiple conceptions and values of the sea, providing an outlet for the views of groups that are often under-represented in conventional approaches to ocean science and management.” (One Ocean Hub, Event Report June 2020)

A hundred and sixty-six people registered and 64 percent of those registered eventually attended. Attendees were from Europe (41 percent), North America (32 percent) and Africa (18 percent). The majority of attendees were women (70 percent) and most were academics and researchers, although, seventeen percent were attendees from the public sector (policy sector) and industry/private sector. The cross-section of attendees suggests that art and the sensory are of interest to a wide variety of stakeholders. The attendees had the following to say about the event itself:

It was really interesting to see so many perspectives on the ocean. It would also have been interesting to consider perspectives of Northern Europe and why we have a very different relationship to the ocean to those that live along the coastlines/island communities. We've gone from big sea faring nations to now ones that only seem to see the ocean as a place of recreation along coastlines. How can we change perceptions of the ocean so that it is not seen as a void or 'the other' for those that are landlocked given that the ocean is key to all humanity. Are there artists exploring this/challenging this that could be included in a future event?

One Ocean Hub assembled a wonderful, diverse panel for this event. The event featured great scholars and artists. I feel like we needed more time for discussion as the panelists created such an energetic and generative space where I personally wanted to stay longer. Maybe, it would be possible to extend time of the meeting for the next time. Thank you for organizing!

I thoroughly enjoyed the event- it stretched my horizons and inspired my thinking and creativity. I would love to have seen more graphic/fine art of the ocean- perhaps there are links to these that can be shared?

Highly enjoyable — not your average zoom. Thanks to all for sharing and the effort in presenting this beautiful work.

Asked whether the session was useful to them and in what way, attendees responded that they would like to use information derived from the session to inform future marine policy-making; preparation of funding proposals; exploring the idea of exhibiting for marine conservation education; using art to advance ocean literacy or exploring new marine philosophies. The latter was especially referencing Nuku’s concept of plastic as sacred and therefore deserving of more circumspect use to prevent oceanic pollution. In retrospect my view is that it is not enough to elicit an affective emotional response to the artwork. There is a real risk, of audiences remaining disengaged, maintaining dominant paradigms for ocean conservation, while accommodating an aesthetics of colonisation and the aestheticization of a disenfranchised humanity. There is dire need for more substantive emic analysis of art and its relevance to diverse ways of conserving the oceans.

Conclusion: Seizing the End

Tim Ingold’s (2011) concept of ‘being-in-the-world’ (the purpose of which, Ingold tells us, is to be fully alive), requires attention to, and possibilities for articulating our sensory nature as a species. In 2020, there was greater (one could even say, global) awareness of the value of the sensory. The Coronavirus pandemic forced humans to social distance, mask-up and to virtualise social encounters, depriving many of a range of sensory experiences. SDG 14, its targets and proposed actions are too a-sensory and put too much store in scientific and secular solutions to ocean conservation. Considering ways to ‘be’ in the world, Ingold adds that we should question the sources we use to generate knowledge and action. The aim is not to generate more information but to find alternative narratives to assist in addressing the critical issues of epistemicide and new possibilities for dealing with ecological crisis that we collectively face.

International development paradigms have tended to change incrementally, working with dominant sources of knowledge to produce targets and action points that reaffirm the very inequalities and lack of diversity routinely lamented. The looming climate change and ocean conservation crisis requires new, bold thinking about the place of humans in a changing world. There is urgent need to consider and include the knowledge frames and ways of being in the world that our fellow human beings find valuable and significant. Part of this process involves what Laplantine (2015) calls ‘le sensible’, that which permits and encourages continuous transformation and the sublimation of categorical thought. Embodied and transmaterial experience and expression are part of a larger conversation about how it is that humans are in the world. The discussion presented in this article calls for attention not only to the sensory nature of human beings, but more importantly to alternative ways of experiencing and conserving the aquapelagos. To date, oceans and coasts have been framed as biological assets and response to the contribution of indigenes to global discourses of ocean management have been largely marginalised or perceived as tangential to core, natural science effort to conserve nature. As 2030 is on the horizon, more space should be given to the social sciences, humanities and art in shaping policy dialogue on ocean conservation. Doing so will yield rich insights into the diverse ways in which various constituencies conceive of and engage with the sea. In Carpe Fin (seize the end), Yahgulanaas admits that we are all at the end of an era and possibly at the beginning of another in the story of conservation. By including the complex frames and ontologies that art offers and by considering the profound relationship that all humans have with oceans and coasts, we have a few last chances to more meaningfully seize this end.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas and George Nuku for sharing their art with me and Phil Hayward (University of Technology, Sydney) for his comments and suggestions on this paper. The research conducted for this paper is jointly funded by the UKRI One Ocean Hub and a South African NRF Grant. UID 129962.

References

- African Union. n.d. Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. https://au.int/en/agenda2063/overview accessed 21/09/2020.

- Arias, R.F.Q., 2019. Cultural conception of space and development in the Colombian Amazon. https://www.intechopen.com/books/indigenous-aboriginal-fugitive-and-ethnic-groups-around-the-globe/cultural-conception-of-space-and-development-in-the-colombian-amazon accessed 10/09/2020

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: a political ecology of things, Durham: Duke University Press.

- Boswell, R., 2020. Interview with Michael Yahgulanaas 10/21/2020

- Braidotti, R., 2016. Posthuman Critical Theory, in Banerji, D., Paranjape, M.R. (eds.) Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures. Springer: India. Pp 13-33.

- Carnes, J. May 2020. ‘Historical Dissidence: The Temporalities and Radical Possibilities of American Comics’, PhD Thesis University of Milwaukee.

- Clifford, J., Marcus, G., 1986. Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. UCLA, Berkeley: University Press.

- Council of the Haida Nation and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2019 SGaan Kinghlas–Bowie Seamount Gin siigee tl’a damaan kinggangs gin k’aalaagangs Marine Protected Area Management Plan 2019 https://haidamarineplanning.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/CHN_DFO_SK-BS_Plan_EN_WEB.pdf accessed 10/11/2020

- Deloughrey, E., 2017. Submarine Futures of the Anthropocene. Comp. Lit., 69: 32-43.

- De Sousa Santos, B., 2014. Epistemologies of the South. Justice against Epistemicide. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

- Dunphy, M., 2020. Haida matriarchs oppose luxury fishing lodge re-openings by ‘occupying’ ancient villages, https://www.straight.com/news/haida-matriarchs-oppose-luxury-fishing-lodge-reopenings-by-occupying-ancient-villages Accessed 12/11/2020

- Escobar, A., 2018. Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Duke University Press: Durham, North Carolina.

- Farbotko, C and Lazrus, H. 2012. ‘The first climate refugees? Contesting global narratives of climate change in Tuvalu’, Global Environmental Change 22 (2): 382-390

- Gablik, S.,1995. The Reenchantment of Art New York: Thames & Hudson.

- Gee, K., 2019. ‘The Ocean Perspective’, in: Zaucha J., Gee K. (eds.) Maritime Spatial Planning. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Hamilton Faris, J. 2019. ‘Sisters of Ocean And Ice: On The Hydro-Feminism Of Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner And Aka Niviâna’s Rise: From One Island To Another’, Shima 13(2): 76-99.

- Harrison, R. March 2016. ‘Seeing and Nothingness: Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, Haida Manga, and a Critique of the Gutter’, Canadian Review of Comparative Literature / Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée 43(1): 51-74.

- Hayward, P. 2012. ‘Aquapelagos and Aquapelagic Assemblages,’ Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures 6(1): 1-11.

- Henderson, J., 2019. Oceans without History? Marine Cultural Heritage and the Sustainable Development Agenda, Sustainability 11(5080): 1-22.

- Howes, D., 2003. Sensual Relations: Engaging the Senses in Culture and Social Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Ifesinachi, O-Y., Nelly I. K., Nelson A. F., Uku, M., Elegbede, J., Isa,O., and Ibukun. J. A., 2020. ‘The Blue Economy–Cultural Livelihood–Ecosystem Conservation Triangle: The African Experience’, Front. Mar. Sci. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2020.00586/full accessed 20/09/2020

- Ingold, T., 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. Routledge: London.

- Laplantine, F., 2015. The Life of the Senses: Introduction to Modal Anthropology. Translated by Jamie Furniss. Bloomsbury: London.

- Lovelock, J. 2009. The Vanishing Face of Gaia: A Final Warning, Penguin Books: London.

- Mignolo. W., 2012. Local Histories/global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton University Press

- Neimanis, A., 2012. ‘Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water’ in Nigianni, C., and F. Söderbäck (eds.) Undutiful Daughters: Mobilizing Future Concepts, Bodies and Subjectivities in Feminist Thought and Practice. Palgrave Macmillan: New York.

- No Author. One Ocean Hub Event Report Art for the Ocean, 11 June 2020.

- Nuku, G. 2011. ‘Perspicacité: the art of George Nuku’, World Art, 1:1, 67-73.

- Nuku. G., 2016a. George Nuku Bottled Ocean 2118. https://bestawards.co.nz/spatial/exhibition-temporary-structures/mtg-hawkes-bay-tai-ahuriri/george-nuku-bottled-ocean-2118/ accessed 19/01/2021

- Nuku. G. 2016b. Bottled Ocean 2116. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YKNZmiBKjHs accessed 19/01/2021

- Orange, C. 2001. Illustrated History of the Treaty of Waitangi, Wellington: Bridget Williams Books pp 318-19, in https://teara.govt.nz/en/map/19476/loss-of-maori-land#:~:text=The%201860s%20saw%20confiscations%20of,was%20left%20in%20M%C4%81ori%20ownership. Accessed 06/03/2021.

- Rayner, R., Jolly, C., Gouldman, C. 2019. Ocean Observing and the Blue Economy, Front. Mar. Sci. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2019.00330/full accessed 20/09/2020/

- Rock, J., Sima, E., Knapen, M., 2019. What is the Ocean: A Sea-Change in our Perceptions and Values? Aquat Conserv., pp. 1-8.

- Shulte McMenamin, D., McMenamin, M., 1996. Hypersea: Life on Land. Columbia University Press: New York.

- Staley, A 2017. Identifying the Vā: Space in Contemporary Pasifika Creative Writing. Masters Thesis. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/62661/2017-05-ma-staley.pdf accessed 03/03/2021

- Sontag, S.1966. ‘The Imagination of Disaster’ in her Against interpretation and other essays, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux: 209-225.

- Swain, R.B., 2017. A critical analysis of the Sustainable Development Goals, in Leal Filho, W., Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research (World Sustainability Series), Springer International Publishing: New York.

- Pool, I. 2011. ‘Death rates and life expectancy – effects of Colonisation on Maori, Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/death-rates-and-life-expectancy/page-4#:~:text=Impact%20of%20introduced%20diseases,-Introduced%20diseases%20were&text=This%20influx%20exposed%20M%C4%81ori%20to,had%20no%20immunity%20to%20them. Accessed 06/03/2021.

- Porter, C. 2017. ‘Where Totem Poles are a living Art (and relics rest in peace)’, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/30/world/canada/totem-poles-haida-nation-british-columbia.html#:~:text=Haida%20Gwaii%2C%20this%20cluster%20of,the%20temples%20of%20Angkor%20Wat.&text=Because%20totem%20poles%20were%20intricately,spelled%20the%20end%20of%20poles. Accessed 06/03/2021.

- UCLG 2013. ‘UNESCO Congress of Hangzhou "Culture: Key to Sustainable Development" Key Messages Of UCLG. http://www.agenda21culture.net/sites/default/files/hangzhou_-_position_-_eng.pdf accessed 10/11/2020

- United Nations 2015a. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf accessed 23/09/2020

- United Nations 2015b. Sustainable Development Goal 14. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/oceans/ accessed 23/09/2020

- UNESCO 2013. The Hangzhou Declaration: Placing Culture at the Heart of Sustainable Development Policies. http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/images/FinalHangzhouDeclaration20130517.pdf accessed 12/11/2020

- Vrancken, P., Tsamenyi, M., 2017. The Law of the Sea: The African Union and its Member States. JUTAS: Pretoria.

- World Commission on the Environment and Development. 1987. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf accessed 09/10/2020

- Yahgulanaas, M.N. 2008. Flight of the Hummingbird: A Parable for the Environment. Greystone Books: Vancouver.

- Yahgulanaas, M.N. 2009. Red: A Haida Manga, Douglas & McIntyre: Vancouver.

- Yahgulanaas, M.N. 2015. ‘Art opens windows to the space between ourselves’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u1R_-3wzYEQ accessed 22/02/2021

- Yahgulanaas, M.N. 2020. ‘Art is a verb not a noun: Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas on "Carpe Fin"’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tn9a0mKqAW8 accessed 22/02/2021.