Useful Plants of the Alangan Mangyan of Halcon Range, Mindoro Island, Philippines

Institute of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines Los Baños, College, 4031 Laguna, Philippines ecvillanueva4@up.edu.ph

Institute of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines Los Baños, College, 4031 Laguna, Philippines iebuot@up.edu.ph

Abstract

Quantitative studies on plant use by the local people have been slowly growing in the Philippines, yet the application of this field has not been fully utilized in a Philippine setting. This study documented the useful plants of the Alangan Mangyan community in Paitan, Naujan, Mindoro Island, Philippines. Based from the face-to-face interview of 60 key informant interviews, this study recorded 199 local names of plants classified into different uses. Results showed that there were more cultivated than wild plant species for food, fodder, medicine, and firewood use categories, while more wild than cultivated species were recorded for construction and timber use categories. While being cultivators of their swidden farms, it was also observed that they did not completely abandon foraging in the forests, as they identify useful plants from their forests. Moreover, the present knowledge on the use of plants is reflective of the changing subsistence strategies over time due to population pressure and influence of the outside social environment. The Alangan knowledge on plant use is vital in biodiversity conservation of the island. Thus, this knowledge must be considered in the formation of inclusive local policies to safeguard the sustainability of their practices. Intergenerational transmission of their knowledge on plant use is also critical in preserving the Alangan culture.

Keywords

Alangan Mangyan, plant use categories, subsistence strategies, shifting cultivation

1. Introduction

People evolved from the beginning how to interact with nature particularly with plants in terms of their utilization. Ethnobotany, a study that deals with the interaction of indigenous peoples with plants, has been significant in the discovery of medicine, food, textile products, pigment and dyes, as well as in conservation and sustainable use of forest resources (Harshberger, 1896; Balick and Cox, 1996). This field has also been crucial in documentation of the indigenous knowledge particularly on plant uses (Balick and Cox, 1996). Ethnobotany is one of the emerging disciplines that investigates the intersection of nature and culture systems (Pretty et al., 2009; Hong, 2013).

Plant-human interaction has been very evident with our indigenous peoples, especially in the Philippines where there are many indigenous groups from the north to the south of the archipelago. Studies about the Philippine ethnobotany were widely conducted in the Philippine indigenous groups, some of which include Ifugao (Conklin, 1967), Bontoc (Bodner and Gereau, 1988), Ayta (Fox, 1952), Hanunoo (Conklin, 1955), and Tasaday people (Yen and Gutierrez, 1974). These studies, being qualitative in nature, provided well-detailed accounts on the ethnobotanical uses of plants. Moreover, studies focusing mainly on ethnomedicinal accounts were also conducted in the country (Balangcod and Balangcod, 2011; Raterta et al., 2014; Olowa and Demayo, 2015; Fajardo et al., 2017). Information on plant uses have been very valuable in the contributing knowledge on medicine and conservation (Pei, 2013).

One of indigenous groups in the Philippines is the Alangan, the native inhabitants in Halcon Range of Mindoro Island, Philippines. These people are horticulturists who progressed from foragers in the forests to cultivators of root crops (Mandia, 2004). The Alangan, together with the seven other indigenous groups in Mindoro Island, are collectively called Mangyan, a term that is used to define the indigenous people living in Mindoro. As the main and the oldest users of the natural resources of the forests of Halcon Range, it is important to know how these people have used the plant resources of Mt. Halcon.

To date, existing studies about plant use of the Alangan were qualitative in nature (Mandia, 2004; Caringal and Guarde, 2015). Quantitative approaches in ethnobotany has been recently growing (Phillips and Gentry, 1993a,b; Oliveira et al., 2007; Lucena et al., 2007; Albuquerque et al., 2011; Lucena et al., 2013) as these have been found to be useful in addressing issues on sustainable use and conservation (Pei et al., 2009). Though there were few studies of quantified plant uses in the Philippines (Abe and Ohtani, 2013; Ong and Kim, 2014), these were all focused on medicinal plants and were not fully utilized in the context of conservation. This study is a quantitative assessment of the plant use patterns of the Alangan people of Mt. Ilong, Halcon Range.

The objectives of the study were as follows: (1) to determine the useful plants of the Alangan Mangyan community at the foothold of Mt. Ilong in Paitan, Naujan, Oriental Mindoro; (2) to document the distribution of plant per use categories; and (3) to analyze how the current knowledge on plant use reflect the subsistence strategies of the Alangan people.

2. Study Area and Methods

Study Area

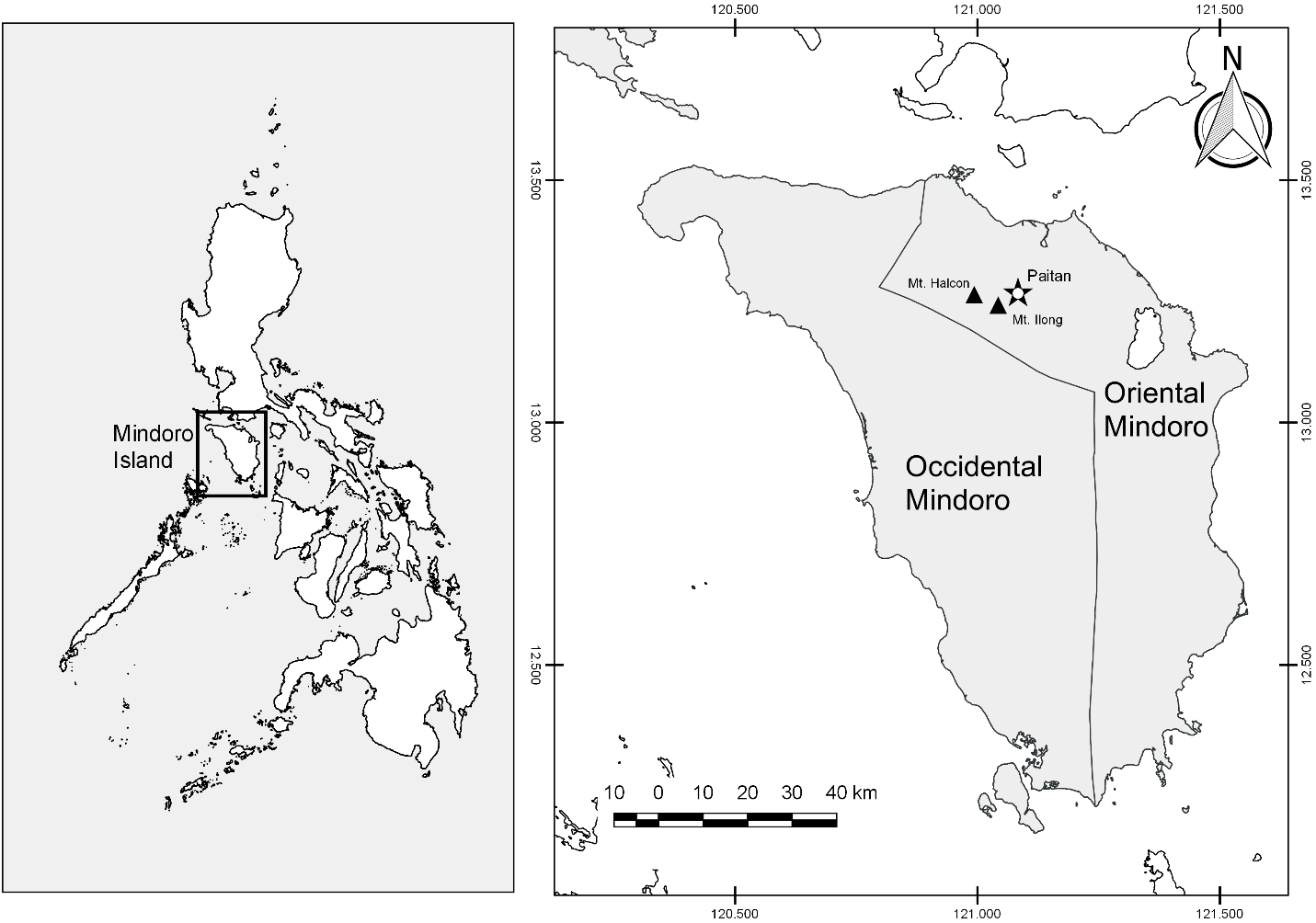

Paitan is a barangay in the municipality of Naujan, Oriental Mindoro (Figure 1). It is a lowland settlement near the foothold of the Halcon Range, particularly Mt. Ilong. This settlement in Paitan was described by Mandia (2004) as a more acculturated community compared to other settlements in the upland area, with some houses made of concrete and galvanized roofs. As of 2015, the population recorded in Brgy. Paitan is 1,519 (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2010), and is composed of 292 households. The annual growth rate of Brgy. Paitan from 2010-2015 is 1.30%, a rate that is lower compared with the growth rate of the province of Oriental Mindoro (1.38%) and of the Philippines as a whole (1.72%).

3. Methodology

A prior informed consent was secured from Samahan ng Nagkakaisang Mangyan Alangan (SANAMA), a people’s organization representing the Alangan Mangyan. The researcher also asked consent from the barangay chairman of Paitan, Naujan, Oriental Mindoro.

In this research, survey questionnaire (written in Filipino) was used as a means of gathering the necessary data. The samples were obtained using systematic random sampling. The material was administered as a face-to-face interview and divided into two parts: socio-demographic profile of the household and knowledge on the use of plants found in the Halcon Range (Appendix A). The semi-structured survey is written in Filipino. The informants were asked to free-list all the plant that they know. After providing an initial list of plants, the informants were asked how they use these resources, whether which part is for food, firewood, medicine, construction, and others to extract more information on plants and their use.

The heads of the household served as the informants in this study. In case the household head was not available, any adult (18 years old and above) in the family who can answer the questions was chosen as informant. Since the aim is to measure knowledge of plant use of the people quantitatively, the informants came from varying age groups, gender, and occupation, most of which being involved in swidden farming.

Moreover, key informant interviews were also conducted with the elders or tribal leaders to further verify the data. Guided tours were also utilized, where the researchers walked with the informants in the vegetation to record their comment and identifications of the plants.

4. Results

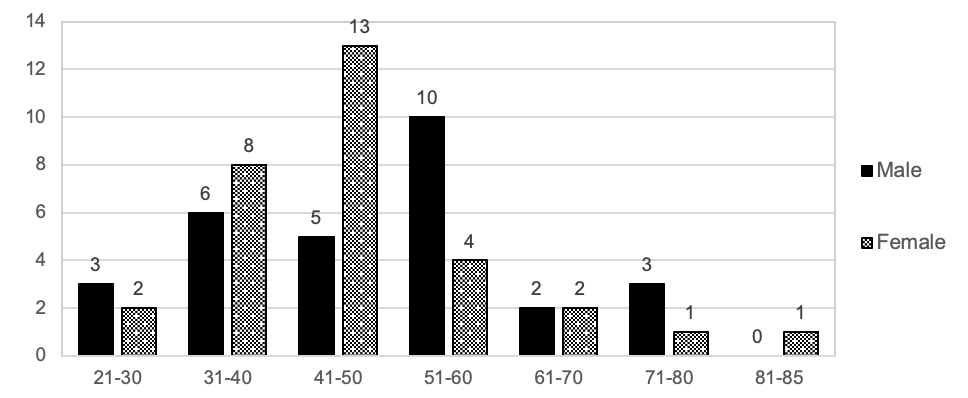

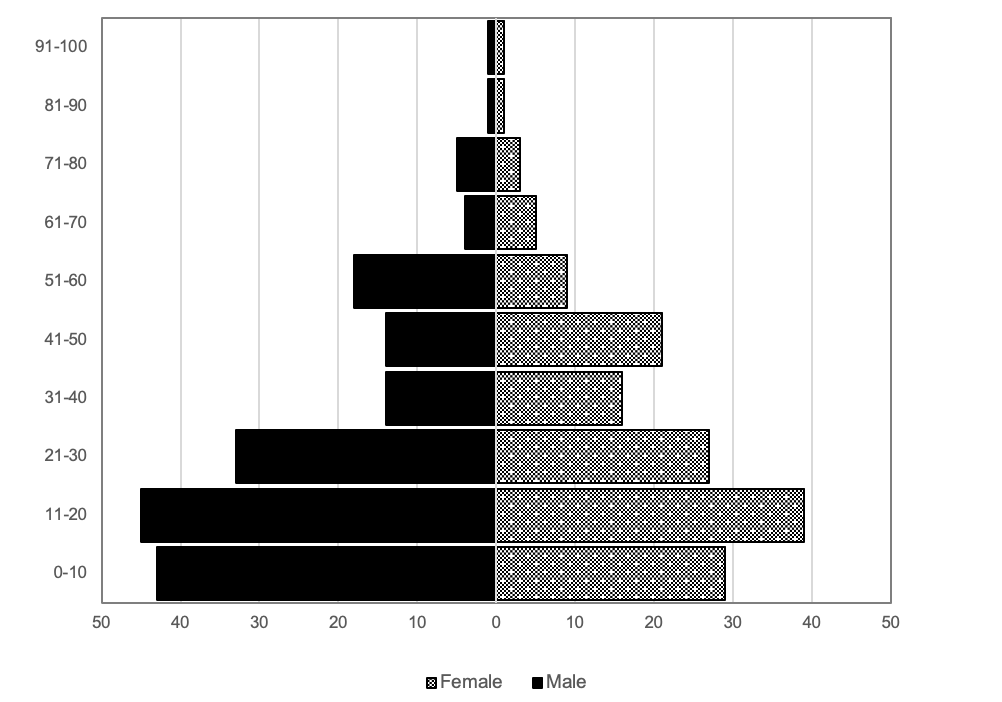

The 60 informants from this survey were composed of 29 male and 31 female respondents. Among these informants, 26.43% were from Sitio Bagong Buhay, 14.23% from Sitio Guna, 13.22% from Sitio Bayanan, and 7.12% from Sitio Bagong Pook. The age and gender distribution of the informants is summarized in Figure 2. The age pyramid of the household members of the informants is shown in Figure 3. Among these informants, 84.33% had a family member involved in swidden farming (kaingin).

Majority of the informants range from 31-60 years old. The graph above shows that highest number of male informants age were at around 51-60 years old, while the highest number of female informants range from 41-50 years old. The average number of years of education (counting from primary year or Grade 1 onwards) was 4.43 years for male informants, and 7.10 years for female informants.

The informants came from varying occupations, majority of which were farmers (55.0%). The rest were composed of housewives (25%), hired workers (6.7%), barangay officials/workers (6.7%), unemployed individuals (3.3%), NGO worker (1.7%) and gardener (1.7%).

The age pyramid of the informants (Figure 3) shows that the composition of their households were young, with the youngest age groups comprising the bottom of the pyramid.

The Useful Plants of the Alangan People

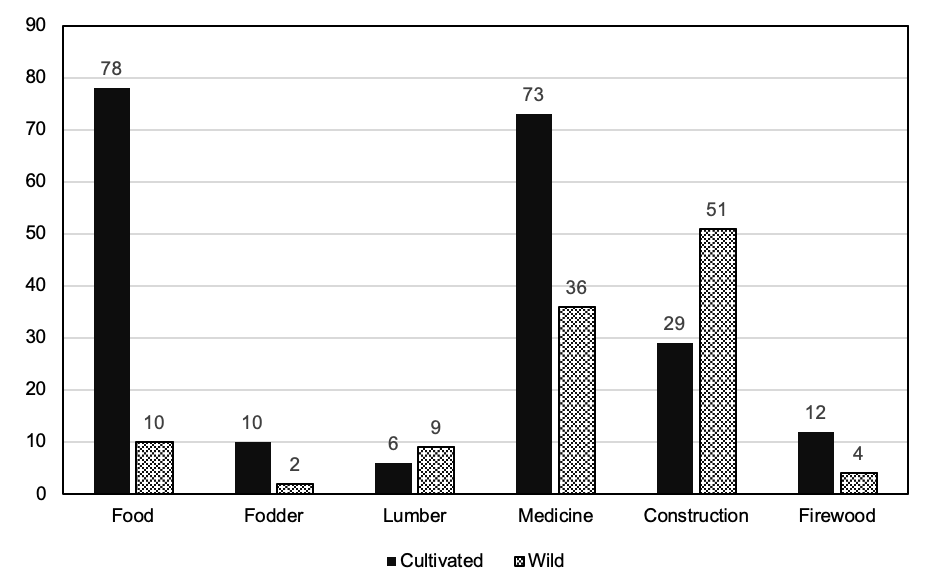

A total of 199 plant names was reported during the interview and were classified according to use categories (Food, Fodder, Lumber, Medicine, Ornamental, Construction, Firewood/Charcoal, Insecticide/Insect Repellant, Cash Crop, and Cultural). Note that except for cultural use, the rest of the recorded uses can be classified as provisioning ecosystem services (MEA, 2005). Figure 4 shows the distribution of plant names per use category, differentiating both wild and cultivated plants.

The graph shows that the people had more knowledge on food and medicinal plants. It was also noticeable that for food, fodder, medicine, and firewood, there were more cultivated than wild plants reported. For lumber and construction, there were more known wild plants than cultivated ones. To further give light to the distribution of plants per use category, the floristics summary per use category is shown in Table 1, indicating the number of identified families, genera, and species per use category.

| Use Categories | Families | Genera | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food | 34 | 61 | 74 |

| Fodder | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Medicine | 44 | 74 | 77 |

| Construction | 28 | 45 | 52 |

| Lumber | 7 | 11 | 14 |

| Cash crop | 20 | 25 | 25 |

| Handicraft | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Pesticide/Insect Deterrent | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Ornamental | 10 | 9 | 9 |

| Cultural | 8 | 9 | 9 |

The Alangan people used a wide variety of species for different use categories. The highest number of families, genera and species were recorded from medicine, food, and construction categories (Table 2). Information on its uses, growth habit, plant part used, and habitat is also shown in this table.

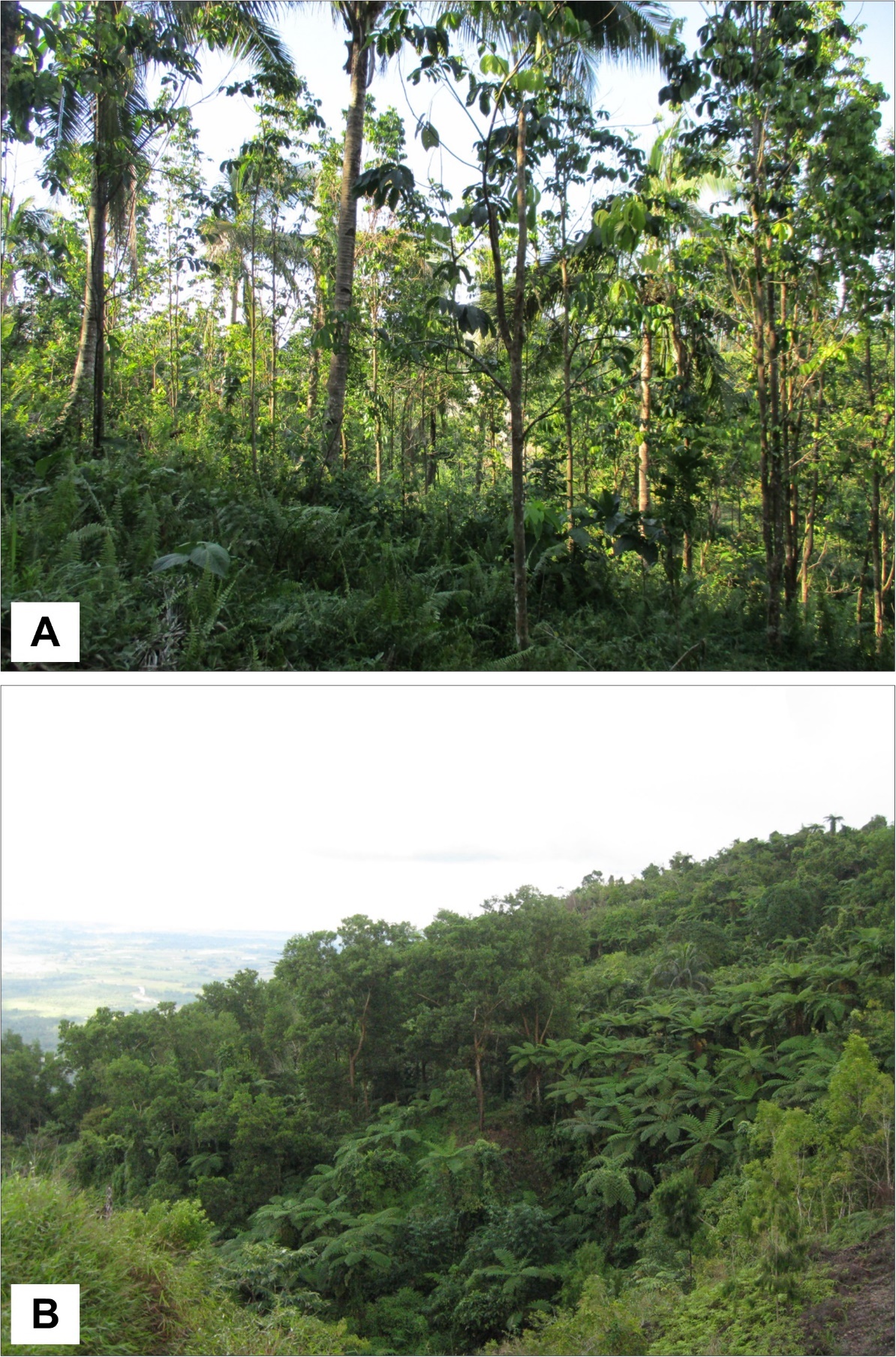

The Alangan people utilized a variety of cultivated and wild plants as food sources. They cultivated plants either in their swidden farms (Figure 5.A) or homegardens. The major carbohydrate source of the Alangan people were “root crops”, which mostly belong to families Araceae and Dioscoreaceae. One notable plant from the forest, namu (Dioscorea hispida), is a semi-cultivated one consumed during times of famine. Although this plant was poisonous, the tubers can be consumed with proper preparation to make it edible (Mandia, 2004). The tubers were sliced thinly and soaked in water in a wooden container overnight, washed and soaked again overnight. Aside from root crops, a few grains (Poaceae) were also added in their diet as carbohydrate sources, such as corn and rice. A few legumes (Fabaceae) were also planted and consumed, which can be considered as good protein sources.

They planted common vegetables for consumption, mostly coming from Family Cucurbitaceae and some solanaceous vegetables. A few leafy vegetables were also reported to be part of their diet, such as mustasa (Brassica juncea), pechay (Brassica rapa), kangkong (Ipomoea aquatica), and malunggay (Moringa oleifera) (Appendix A).

Fruit trees were also cultivated in their swidden farms, and these were usually being sold as cash crops as well (Appendix A). These trees include avocado (Persea Americana), duhat (Syzygium cumini), durian (Durio zibethinus), calamansi (×Citrufortunella microcarpa), jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), sinturis (Citrus reticulata), uloy (Artocarpus odoratissimus), coconut (Cocos nucifera), guyabano (Annona muricata) and papaya (Carica papaya). Also included in this use categories were condiments, and these plants are easily gathered from their homegardens, such as luya (Zingiber officinale), luyang dilaw (Curcuma longa), bawang (Allium sativum), samoro (Ocimum basilicum), kalamias (Averrhoa bilimbi), paminta (Piper nigrum), tanglad (Cymbopogon citratus), and sili (Capsicum anuum).

There were also a variety of plants that were reported to have medicinal properties (Appendix B). These medicinal plants have different forms of preparation and can be used in treating a variety of illnesses. Their homegardens served as most accessible source of medicinal plants, helpful in times of emergency. Some medicinal plants were also obtained from their swidden farms and forests.

Construction plants refer to those plants that are used for building houses, either for pillars, walls, roofs, flooring, or even fences. Cordages used in building houses were also included under this category. Most of the plants that were used for house construction were woody trees. Some of the notable construction plants were members of Family Dipterocarpaceae, Lauraceae, and Fabaceae (Appendix A). Majority of the trees that fall under the construction category were generally gathered from forests and were also used as sources of lumber. Some other species used by the Alangan people can be found in the swidden farms, and these include a few wild woody trees (a combination of native and exotic trees), fruit trees, species of bamboo (Bambusoideae), and cogon (Imperata cylindrica). For cordage, the Alangan used some forest shrubs such as tibanwa (Dracaena angustifolia), uway (Calamus/Daemonorps spp.), hagnaya (Stenochlaena palustris), nito (Lygodium spp.), banban (Donax canniformis), ulango (Pandanus radicans), and balingway (Flagellaria indica) (Appendix A).

Some plants were also utilized as sources of charcoal and firewood (Table 1). These were all woody plants useful in building fire for cooking. These firewood sources were mainly composed of fruit trees such as avocado (Persea americana), guyabano (Annona muricata), kalamansi (x Citrufortunella microcarpa), kape (Coffea canephora), lanzones (Lansium parasiticum), mangga (Mangifera indica), nangka (Artocarpus heterophyllus), niyog (Cocos nucifera), rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum), santol (Sandoricum koetjape), and sinturis (Citrus reticulata). The other plants that are used as firewood include batino (Alstonia macrophylla Wall ex G.Don), ipil-ipil (Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Witt), mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla),kawayan (Bambusoideae), and saransok (Melastoma polyanthum Brum.f.). The Alangan also used to weaved baskets and containers either used or sold in the market. Some of the plant materials that they use come from balingway (Flagellaria indica L.), different species of kawayan (Bambusoideae), nito (Lygodium sp.), uway, and yantok (Calamus/Daemonorps spp.).

The Alangan practiced chewing betel nut, (Areca catechu), which has always been an important part of their culture. The betel nut (locally known as bunga) is usually mixed with apog (lime), mam-in (Piper betle), and tabako/sadiwa (Nicotiana tabacum). These four ingredients, when mixed, is collectively called as nganga. A few plants were also used in making their costumes, such as anongo (Ficus sp.), which is used in making abayan, nito (Lygodium sp.) and uway (Calamus/Daemonorops spp.), which can be used in making yakis.

5. Discussion

Patterns in Plant Use Categories

The results from Tables 1 and Appendix A showed that the Alangan people of Brgy. Paitan, Naujan, Oriental Mindoro were able to utilize a wide variety of plants — both wild and cultivated types — from the forest (Figure 5.B), their swidden farms (Figure 5.A), up to their own homegardens. Some of these plants were recounted to have multiple uses. The floristic diversity per use category was summarized in Table 1, showing the highest species number from medicine, food, and construction categories.

There were some ethnobotanical studies that quantified the number of species per use category. Cunha and Albuquerque (2006) conducted a quantitative ethnobotanical study of tree and shrub species in northern Brazil. It was found out in their study that the use categories with most number of species were related to obtaining wood, such as house construction, firewood and charcoal production, which is very similar to how the Alangan people made use of their plant resources at the Halcon Range. Another study by Torre-Cuadros and Islebe (2003) assessed the TEK of the Maya people in northern Quintana Roo (southeastern Mexico). The most common uses of plants were construction, medicine, crafts, and food. Moreover, a study in Central Western Spain, Iberian Peninsula analyzed the floristic diversity of plant use (Gonzales et al., 2013). The use categories with highest recorded number of plants were medicine, food, industry, and handicraft. An ethnobotanical study in Eastern Tanzania (Luoga et al., 2000), found out that the major plant use categories of Kwere and Zigua tribes include charcoal, firewood, medicine, and poles.

The major plant use categories in the Alangan context was relatively similar with other indigenous people in the world. For food and medicine categories, most of the species that were reported by the Alangan informants were readily accessible as these can mostly be found in their swidden farms and homegardens. Furthermore, members of this use categories were mostly composed of cultivated plants making these plants more available than the wild plants from the forest area.

High diversity of cultivated crops in various habitat types reduces the pressure on wild plant resources, leading to a more sustainable forest use (Pei et al., 2009). Furthermore, cultivation of these various plants in such as homegardens and swidden farms provides subsistence at least in their basic needs (Soemarwoto, 1987) such as food and medicine. It also provides additional income for the people.

The food plants of the Alangan share relative similarity with food plants used by other indigenous peoples in the Philippines, like the Ayta (Fox, 1952), Hanunoo Mangyan (Conklin, 1955), and the Bontoc people (Bodner and Gereau, 1988). It is worth noting, moreover, that these groups, including the Alangan Mangyan, share the same subsistence strategy as swidden cultivators, and thus having relatively similar and diverse staple crops, fruits and vegetables. Aroids such as gabi (Colocasia esculenta) and root crops such as kamote (Ipomoea batatas) are some of the common and widely used staple crops in the kaingin farms of the indigenous peoples in the Philippines (Matthews et al., 2012; Pardales, 1997; Caringal and Guarde, 2015). Fruits and vegetables of different species were also similar and cultivated alongside with these crops.

There were a variety of plants that were utilized for construction purposes (Appendix A), and whether trees or shrubs, these were all woody in nature. For this use category, there were more wild species utilized than from cultivated ones. This only shows that the Alangan people were dependent on the forest for some resources, at least in terms of the woody species for construction purposes.

As shifting cultivators, it is only natural that the Alangan people know a lot about their cultivated plants. While they were mainly utilizing plants from their swidden farms, the Alangan people of Paitan preferred to obtain some local flora from the forests. This only means that they did not completely abandon their nature as foragers, as they were still able to name some useful plants from their forests. Perhaps, as they interacted with nature, they tried as much as possible to cultivate some plants of daily importance but retained the nature harvesting practice for some plants which they do not need for everyday use.

Evolution of Subsistence Strategies in the Alangan Context

It has been attested that the forest has better protection when the traditional practices is well-maintained (Pei et al., 2009). However, in the context of changing environment, it is evident that the subsistence strategies of the Alangan people have gradually evolved over time. As an adaptive response to the changing environmental and socio-economic conditions, the traditional ecological knowledge of the indigenous people can also change (Gomez-Baggethun and Reyes-Garcia, 2013).

In the Aytas of Pampanga, Philippines, for example, in an ethnobotanical survey by Ragragio et al. (2013), it was observed that there was a decrease in their knowledge of useful plants, as compared from the earlier study of Fox (1952). The authors argued that this happened as contributed by some factors, including the displacement of the people and acculturation, as well as loss of forest cover due to the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo.

In the Alangan setting, it can be seen from the results of this study (Appendices A and B) that the knowledge on plant use of the Alangan people is more than a byproduct of the oral culture that is passed from generation to generation. For instance, it was observed that in the case of plants categorized as medicine, there were plants found in their homegardens that are not naturally growing in their forest. They make use of these medicinal plants the same way with the lowlanders. These people somehow managed to plant these species for an easier access to herbal medicine in times of emergency. Some of the local health workers were able to gain knowledge through the trainings and seminars that they attend to. The older people and traditional healers, meanwhile, remain knowledgeable on forest plants.

The Alangan people in Paitan were able to adapt the culture of the lowlanders. The Alangan culture should not be considered as an isolated system: these people interacted with the lowlanders with their cultures. These practices should not be seen as static, but rather as dynamic which is evolving as a response to the changing conditions (Wiersum 1997; Soemarwoto, 1986).

However, this influence from the outside social environment can cut both ways. Indigenous knowledge can be achieved by accepting new knowledge and disregard some components that were less suitable in their everyday living. This change can only be considered healthy if they are able to apply their own knowledge (Gomez-Baggethun and Reyes-Garcia, 2013); otherwise, the influence will result to the detriment of their own culture.

An evidence of this adaptation in the Alangan context was documented by Caringal and Guarde (2015) in their study in Paitan and Bualao, another Alangan community in the upland of the Alangan Valley. The Alangan people were able to develop a food security strategy called himalay, a practice where they glean leftover rice grains upon harvest on the land of the lowlanders. This adaptation is not an old one, as the Mangyans in general once inhabited the plains and the coastal areas of Mindoro Island. They migrated to the forest and mountain areas as lowlanders began settling in the island circa 50 years ago. As they developed this rice gleaning practice, they retained knowledge on several varieties of their staple upland root crops such as kamuti (Ipomoea batatas) and gabi (Colocasia esculenta), which they cultivate in their swidden farms.

The changing patterns in the food subsistence practices of the Alangan is a likeness of the theory of Esther Boserup (1965), which states that the increasing population leads to a more intensified agricultural production. The population of Brgy. Paitan is gradually growing at an annual growth rate of 1.3% from 2010-2015 (PSA, 2010; 2015). To meet the needs of their people, the traditional clearing-fallowing cycle was less observed in their swidden farms. Recently, their practice is slowly transforming into a more permanent form of agriculture (Mandia, 2004). During the interview with the key informants, from the previously reported fallow period of 5-10 years (Mandia, 2004), the resting period for the swidden farms was shortened to three years. It is worth noting, moreover, that the harvest in their farms is not primarily for consumption but for trade to help secure lowland goods (Quiaoit, 1997).

This shortening of the fallow period among swidden farms has been a trend in the Philippines (Lasco et al., 2001) and in Southeast Asia (Rasul and Thapa, 2003). This trend was also observed in the swidden farms of Hanunuo Mangyan in Bulalacao, Oriental Mindoro (Gascon, 1998). From 10-15 years (as reported by Conklin, 1955), fallow period was shortened to 1-3 years. This practice was described as unsustainable, as it can result to lower soil fertility and increased erosion rates (Dressler et al., 2017).

Given this situation, if their present agroforest lands cannot meet the needs of the people, there is a possibility of an increasing demand for agroforest lands in the future, leading to encroachment to the upper slopes of the forest area. This scenario, however, remains a possibility as the forests of the Halcon Range remain to play an integral part of the Alangan people. They consider the mountains as sacred and have a deep respect for their lands. In fact, the Alangan word kubat means “world”, and this term has a double connotation. Kubat also means “forest”, which implies that the world is forest for them (Schult, 2001). As one of the key informants have stated: Kung gagamitin mo siya [ang kalikasan] gagamitin ka rin nito. Kung iingatan mo ang kalikasan, iingatan ka rin nito (If you dominate over nature, it will also make use of you. If you will take care of nature, it will also take care of you.). Their understanding of the forest-people interaction and culture of valuing the forest is deeply rooted and can play a crucial role in the protection of their lands.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study was able to collect information on the use of plants by the Alangan people of Halcon Range, Mindoro Island, Philippines. Results showed that plants remain an important component of their life by providing their necessities such as food, medicine, and house construction, just like in other indigenous communities worldwide. The Alangans have many plants easily domesticated in their swidden farms but some periodically needed plants are still harvested from the nearby forest. The use of these plants is reflective of their evolving subsistence strategies. They are gradually moving to a more permanent form of agriculture, which can be attributed to increasing population pressure. The transition from shifting cultivation to permanent agriculture only shows the dynamic adaptation of the Alangan culture through time.

While other influences such as acculturation and population pressure are inevitable in the Alangan community in Paitan, Naujan, Oriental Mindoro, their traditional ecological knowledge, particularly on the use of plants can play a vital part in conserving biodiversity of Mindoro. Therefore, in creating local policies to safeguard the sustainability of their agricultural practices, a close collaboration between the local government units (LGU’s) and indigenous community is highly recommended.

Moreover, intergenerational transmission of the knowledge on the use of plants and values on the importance of the forest ecosystem is recommended by teaching the younger generation of Alangan people on their culture and the use of plants. This study also gives light on the potential of homegardens for in situ conservation of plant species from their forest. As this study primarily dealt with provisioning ecosystem services from plants, it would also be interesting to document and quantify how these people perceive other ecosystem services.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of the MS Thesis of the first author. The researchers would like to express their gratitude the following: [1] AM Caringal and [2] Mangyan Heritage Center (MHC) for providing valuable references and logistical assistance during the conduct of this study; [2] SANAMA for their assistance and allowing the researchers to have this study conducted in their community; [3] UPLB School of Environmental Science and Management and Institute of Biological Sciences for providing facilities for the researchers; [4] the Department of Science and Technology - Science Education Institute (DOST-SEI) for providing financial support for the conduct of this study through the Accelerated Science and Technology Human Resource Development Program (ASTHRDP); and [5] the National Research Council of the Philippines (NRCP) for providing grant for this research.

References

- Abe, R. and Ohtani, K., 2013 An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants and traditional therapies on Batan Island, the Philippines, J. Ethnopharmacol., 145(2): 554-565 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.029.

- Albuquerque, U.P., Soldati, G.T., Sieber, S.S., Medeiros, P.M., Sá, J.C. and de Souza, L.C., 2011. Rapid ethnobotanical diagnosis of the Fulni-ô Indigenous lands: Floristic survey and local conservation priorities of medicinal plants. Environ. Dev. Sustain., 13: 277-292. 10.1007/s10668-010-9261-9

- Balangcod, T.D. and Balangcod, A.K. 2011. Ethnomedicinal knowledge of plants and healthcare practices among the Kalanguya tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, Philippines. Indian J. Tradit. Know., 10(2): 227-238.

- Balick, M.J. and Cox, P.A. 1996. Plants, people, and culture: the science of ethnobotany. Scientific American Library. 228pp.

- Bodner, C.C. and Gereau, R.E., 1988. A contribution to Bontoc ethnobotany. Econ. Bot, 42: 307-369. 10.1007/BF02860159

- Boserup, E., 1965. The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change under Population Pressure. London: Transaction Publishers.

- Caringal, A.M. and Guarde, J.A.D., 2015. Nature farming and himalaynization: Food subsistence strategies by the Mangyan Alangan Tribe of Mindoro, Philippines. Asia Life Sci., 24(2): 601-627.

- Conklin, h.c., 1955. The Relation of the Hanunóo Culture to the Plant World. Dissertation. Yale University.

- Conklin, H.C. 1967. Ifugao ethnobotany 1905–4965: The 1911 Beyer-Merrill report in perspective. Econ. Bot., 21(3): 243-272.

- Conservation International Philippines, Department of Environment and Natural Resources-Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau, and Haribon Foundation for the Conservation of Nature, 2006. Priority Sites for Conservation in the Philippines: Key Biodiversity Areas. Quezon City, Philippines: Conservation International Philippines. Accessed on 20 May 2015 from http://www.conservation.org/global/philippines/publications/Pages/Priority-Sites-for-Conservation-Key-Biodiversity-Areas.aspx.

- Cunha, L.V.F. and Albuquerque, U.P., 2006. Quantitative Ethnobotany in an Atlantic Forest Fragment of Northeastern Brazil – Implications to Conservation. Environ. Monit. Assess., 114: 1-25. 10.1007/s10661-006-1074-9

- Dressler, W.H., Wilson, D., Clendenning, J., Cramb, R., Keenan, R., Mahanty, S., Brunn, T.B., Mertz, O. and Lasco, R.D., 2017. The impact of swidden decline on livelihoods and ecosystem services in Southeast Asia: A review of the evidence from 1990 to 2015. Ambio, 46: 291-310. 10.1007/s13280-016-0836-z

- Fajardo, W.T., Cancino, L.T., Dudang, E.B., De Vera, I.A., Pambid, R.M. and Junio, A.D. 2017. Ethnobotanical Study of Traditional Medicinal Plants Used by Indigenous Sambal-Bolinao of Pangasinan, Philippines. Pangasinan State University Journal of Natural And Applied Sciences, 1(1): 45-55.

- Fox, r.b., 1952. The Pinatubo Negritoes: Their useful plants and material culture. Philipp. J. Sci,, 81(3-4): 173-414.

- Gascon, C.N., 1998. Sustainability indicators of the Hanunuo Mangyan Agroforestry Systems, Sitio Dangkalan, Bulalacao, Oriental Mindoro, Philippines. Dissertation. University of the Philippines Los Baños.

- Gomez-Baggethun, E. and Reyes-Garcia, V., 2013. Reinterpreting Change in Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Hum. Ecol., 41: 643-647. 10.1007/s10745-013-9577-9

- González, J.A., García-Barriuso, M., Ramírez-Rodríguez, R., Bernardos, S. and Amich, F., 2013. Ethnobotanical Resources Management in the Arribes del Duero Natural Park (Central Western Iberian Peninsula): Relationships between Plant Use and Plant Diversity, Ecological Analysis, and Conservation. Hum. Ecol., 41: 615-630. 10.1007/s10745-013-9603-y

- Harshberger, J.W. 1896. Purposes of ethnobotany. Botanical Gazette, 21(3): 146-154

- Hong, S.K. 2013. Biocultural diversity conservation for island and islanders: Necessity, goal and activity. J. Mar. Island Cult., 3: 102-106. 10.1016/j.imic.2013.11.004

- Hoogerbrugge, I. and Fresco, L.O. 1993. Homegarden Systems: Agricultural Characteristics and Challenges. International Institute for Environment and Development Gatekeeper Series No. 39. Wageningen, Wangeningen Agricultural University.

- Lasco, R.D. and Pulhin, J.M. 2001. Secondary forests in the Philippines: Formation and transformation in the 20th century. J Trop For Sci., 13(4): 652-670.

- Lucena, R.F.P., Araújo, E.L. and Albuquerque, U.P., 2007. Does the local availability of woody Caatinga plants (Northeastern Brazil) explain their use value? Econ. Bot 61(4): 347-361. 10.1663/0013-0001(2007)61[347:DTLAOW]2.0.CO;2

- Lucena, R.F.P., Lucena, C.M., Araújo, E.L., Alves, Â.G.C. and Albuquerque, U.P., 2013. Conservation priorities of useful plants from different techniques of collection and analysis of ethnobotanical data. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc., 85(1): 169-186. 10.1590/S0001-37652013005000013

- Luoga, E.J., Witkowski, E.T.F. and Balkwill, K., 2000. Differential Utilization and Ethnobotany of Trees in Kitulanghalo Forest and Surrounding Communal Lands, Eastern Tanzania. Econ. Bot 54: 328-343. 10.1007/BF02864785

- Mandia, E.H. 2004. The Alangan Mangyan of Mt. Halcon, Oriental Mindoro: Their Ethnobotany. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 32: 96-117.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. Island Press, Washington, DC.

- Mindoro Biodiversity Conservation Foundation, Inc. 2012. Mount Halcon Conservation and Management Plan. Accessed on 26 November 2016 from http://mbcfi.org.ph/media/Technical_Reports/1_%20Mt_Halcon _Conservation_Management_Plan.pdf

- Oliveira, R.L.C., Lins Neto, E.M.F., Araújo, E.L. and Albuquerque, U.P., 2007. Conservation priorities and population structure of woody medicinal plants in an area of Caatinga vegetation (Pernambuco State, NE Brazil). Environ. Monit. Assess., 132: 189-206. 10.1007/s10661-006-9528-7

- Olowa, L. and Demayo, C.G. 2015. Ethnobotanical uses of medicinal plants among the Muslim Maranaos in Iligan City, Philippines. Advances in Environmental Biology, 9(27): 204-215.

- Pei, S. 2013. Ethnobotany and the sustainable use of biodiversity. Plant Diversity and Resources, 35(4): 401-406.

- Pei, S., Zhang, G. and Huai, H. 2009. Application of traditional knowledge in forest management: Ethnobotanical indicators of sustainable forest use. Forest Ecol. Manag., 257: 2017-2021. 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.01.003

- Philippine Statistics Authority, 2010. 2010 Census of Population and Housing. Accessed on 1 April 2017 from http://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/attachments/hsd/pressrelease/MIMAROPA.pdf

- Philippine Statistics Authority (2015). 2015 Census of Population and Housing. Accessed on 1 April 2017 from https://www.psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/attachments/hsd/pressrelease/R04B.xlsx

- Phillips, O. and Gentry, A.H., 1993a. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru I. Statistical hypotheses tests with a new quantitative technique. Econ. Bot., 47(1): 15-32. 10.1007/BF02862203

- Phillips, O. and Gentry, A.H., 1993b. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru II. Additional hypothesis testing in quantitative ethnobotany. Econ. Bot., 47(1): 33-43. 10.1007/BF02862204

- Pretty, J., Adams, B., Berkes, F., Athayde, S.F., Dudley, N., Hunn, E., Maffi, L., Rapport, D., Robbins, P., Sterling, E., Stolton, S., Tsing, A., Vintinner, E. and Pilgrim, S. 2009. The intersections of biological diversity and cultural diversity: Towards integration. Conserv. Soc., 7(2): 100-112.

- Quiaoit, J.S., 1997. The changing patterns in the man-land relationship of the Alangan Mangyan of Oriental Mindoro. Master’s Thesis. Xavier University, Cagayan de Oro.

- Ragragio, E.M., Zayas, C.N. and Obico, J.J.A., 2013. Useful plants of selected Ayta communities from Porac, Pampanga, twenty years after the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo. Philipp. J. Sci., 142: 169-181.

- Raterta, R., De Guzman, G.Q. and Alejandro, G.J.D. 2014. Assessment, inventory and ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Batan and Sabtang Island (Batanes Group of Islands, Philippines). International Journal of Pure and Applied Bioscience, 2(4): 147-154.

- Rasul, G. and Thapa, G.B., 2003. Shifting cultivation in the mountains of South and Southeast Asia: Regional patterns and factors influencing the change. Land Degrad. Dev., 14(5): 495-508. 10.1002/ldr.570

- Schult, V., 2001. Deforestation and Mangyan in Mindoro. Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints, 49(2): 151-175.

- Soemarwoto, O. 1986. Homegardens: a traditional agroforestry system with a promising future. In Steppler, HA and Nair, PKR (eds) Agroforestry: A decade of development. Nairobi: International Council for Research in Agroforestry: 157-170

- Torre-Cuadros, M.D.L.A. and Islebe, G.A., 2003. Traditional ecological knowledge and use of vegetation in Southeastern Mexico: a case study from Solferino, Quintana Roo. Biodivers. Conserv., 12: 2455-2476. 10.1023/A:102586101

- Wiersum, K.F., 1997. Indigenous exploitation and management of tropical forest resources: an evolutionary continuum in forest-people interactions. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ., 63: 1-16. 10.1016/S0167-8809(96)01124-3 Yen, D.E. and Gutierrez, H.G. 1974. The ethnobotany of the Tasaday: The useful plants. Philipp. J. Sci., 103(2): 75-140.

| Family/Species | Local/English Common Name | Growth Habit | Uses | Parts Used | Habitat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achariaceae | |||||

| Pangium edule Reinw. | kulilis | tree | Construction | stem | forest |

| Acoraceae | |||||

| Amaranthaceae | |||||

| Aerva lanata (L.) Schult | agad-agad | herb | Medicine | flower, leaf | homegarden |

| Amaranthus spinosus L./ A. cruentus L. | uray | herb | Medicine | leaf, root | homegarden |

| Amaryllidaceae | |||||

| Allium sativum L. | bawang | herb | Food, Medicine | bulb | homegarden |

| Anacardiaceae | |||||

| Mangifera indica L. | mangga | tree | Medicine, Food, Cash crop, Firewood | fruit | homegarden, swidden farm |

| Spondias pinnata (L. f.) Kurz | libas | tree | Food | fruit | forest |

| Annonaceae | |||||

| Annona muricata L. | guyabano | tree | Medicine, Food, Cash crop, Firewood | leaf, shoot, bark | homegarden, swidden farm |

| Cananga odorata (Lam.) Hook.f. and Thomson | ilang-ilang | tree | Construction | stem | swidden farm |

| Arecaceae | |||||

| Cocos nucifera L. | niyog | tree | Food, Construction, Lumber, Medicine, Fodder, Firewood, Cash crop | fruit, stem | homegarden, swidden farms |

| Asparagaceae | |||||

| Dracaena angustifolia (Medik.) N.E.Br. | tibanwa | shrub | Construction, Medicine | bark, leaf | forest |

| Aspleniaceae | |||||

| Asplenium nidus L. | pakpak-lawin | herb | Ornamental | forest, homegarden | |

| Asteraceae | |||||

| Ageratum conyzoides (L.) L. | bugasnay | herb | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Artemisia vulgaris L. | kamarya | herb | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Blumea balsamifera (L.) DC. | sambong | shrub | Medicinal | leaf | homegarden |

| Chromolaena odorata (L.) R.M.King and H.Rob | hagonoy | shrub | Pesticide | leaf | homegarden |

| Chrysanthemum indicum L. | mansanilya | herb | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Mikania cordata (Burm.f.) B.L.Rob. | uting | herb | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Tagetes erecta L. | amarilyo | herb | Ornamental | flower | homegarden |

| Athyriaceae | |||||

| Diplazium esculentum (Retz.) Sw. | pako | herb | Food, Fodder | leaf | swidden farms |

| Balsaminaceae | |||||

| Impatiens balsamina L. | kamantigue | herb | Medicine, Ornamental | fruit | homegarden |

| Blechnaceae | |||||

| Stenochlaena palustris (Burm. f.) Bedd. | hagnaya | herb | Food, Construction | leaf | forest |

| Boraginaceae | |||||

| Heliotropium indicum L. | aritis-aritisan | herb | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Brassicaceae | |||||

| Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. | mustasa | herb | Food | leaf | homegarden |

| Brassica rapa L. | pechay | herb | Food | leaf | homegarden |

| Raphanus raphanistrum subsp. sativus (L.) Domin | labanos | herb | Food | root | homegarden |

| Bromeliaceae | |||||

| Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. | pinya | herb | Food, Medicine | fruit, young leaf | swidden farm, homegarden |

| Burseraceae | |||||

| Canarium sp. | sahing | tree | Medicine | resin | forest |

| Cannabaceae | |||||

| Trema orientalis (L.) Blume | anadyong | tree | Medicine | bark | homegarden |

| Capparidaceae | |||||

| Capparis zeylanica | dawa | shrub (liana) | Food | fruit | swidden farms |

| Caricaceae | |||||

| Carica papaya L. | papaya | tree | Food, Medicine, Cash crop | fruit, leaf, stem, sap | swidden farms, homegarden |

| Clusiaceae | |||||

| Garcinia brevirostris Scheff. | basal | tree | Construction | stem | forest |

| Garcinia sp. L. | bagyuan | tree | Construction | stem | swidden farm |

| Combretaceae | |||||

| Combretum indicum (L.) DeFilipps. | niyog-niyogan | shrub | Medicine | fruit | homegarden |

| Convolvulaceae | |||||

| Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. | kangkong | herb | Food | leaf | homegarden |

| Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. | kamote | herb | Food, Cash crop, Fodder | root, shoot | swidden farm, homegarden |

| Ipomoea sp. L. | kamoteng amlay | herb | Food | root | forest |

| Merremia peltata (L.) Merr. | bulakan | herb (vine) | Medicine | shoot | swidden farm |

| Crassulaceae | |||||

| Bryophyllum pinnatum (Lam.) Pers. | kataka-taka | herb | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Cucurbitaceae | |||||

| Benincasa hispida (Thunb.) Cogn. | kundol | herb | Food | fruit | homegarden |

| Cucumis sativus L. | pipino | herb (vine) | Food | fruit | homegarden |

| Cucurbita maxima Duchesne | kalabasa | herb (vine) | Food, Cash crop | fruit | swidden farms |

| Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. | tabayag/upo | herb (vine) | Food, Cash crop | fruit | homegarden, swidden farm |

| Luffa acutangula (L.) Roxb. | patola | herb (vine) | Food | fruit | swidden farms, homegarden |

| Momordica charantia L. | ampalaya | herb (vine) | Food, Medicine, Cash crop | fruit | homegarden, swidden farm |

| Momordica sp. | ampalayang ligaw | herb (vine) | Medicine, Food | fruit | forest |

| Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw. | sayote | herb (vine) | Food | fruit | homegarden |

| Cunoniaceae | |||||

| Weinmannia hutchinsonii Merr. | talaki | tree | Construction | stem | forest |

| Dioscoreaceae | |||||

| Dioscorea alata L. | ube | herb | Food, Cash crop | root | swidden farms |

| Dioscorea divaricata Blanco | labey | herb | Food | stem | swidden farm |

| Dioscorea hispida Dennst. | namu | herb | Food | root | forest |

| Dipterocarpaceae | |||||

| Dipterocarpus grandiflorus (Blanco) Blanco | apitong | tree | Construction, Lumber | stem | forest |

| Shorea contorta S.Vidal | lawaan | tree | Construction, Lumber | stem | forest |

| Shorea negrosensis Foxw. | lawaang pula | tree | Construction, Lumber | stem | forest, swidden farm |

| Shorea polysperma Merr. | tangile | tree | Construction, Lumber | stem | forest |

| Euphorbiaceae | |||||

| Codiaeum variegatum (L.) Rumph. ex A.Juss | San Francisco | shrub | Ornamental | leaf | homegarden |

| Euphorbia hirta L. | tawa-tawa | herb | Medicine | whole plant | homegarden |

| Jatropha curcas L. | tuba | tree | Medicine | leaf, bark | homegarden, swidden farm |

| Macaranga bicolor Müll.Arg. | amilig | tree | Construction | stem | forest |

| Manihot esculenta Crantz | balinghoy | shrub | Food, Fodder, Cash crop, Medicine | root, leaf | swidden farms, homegarden |

| Fabaceae | |||||

| Acacia mangium Willd. | mangyum | tree | Construction, Lumber, Medicine | leaf, stem | forest |

| Caesalpinia sappan L. | sibukaw | tree | Medicine | bark | forest, homegarden |

| Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp. | kadyos | herb | Food | fruit | swidden farms |

| Derris elliptica (Wall.) Benth. | tubli | herb (vine) | Pesticide | root | homegarden |

| Falcataria moluccana (Miq.) Barneby and J.W.Grimes | palakata | tree | Construction, Lumber | stem | swidden farm, forest |

| Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp. | kakawate | tree | Construction, Medicine, Fodder | stem | swidden farm, homegarden |

| Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Witt | ipil-ipil | tree | Firewood | stem | homegarden, swidden farm |

| Mimosa pudica L. | makahiya | herb | Medicine | root | homegarden |

| Phaseolus lunatus L. | patani | herb (vine) | Food | fruit | swidden farms, homegarden |

| Phaseolus vulgaris L. | sitaw | herb (vine) | Food, Cash crop | fruit | swidden farm, garden |

| Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC. | kalamismis/gabay | herb (vine) | Food | fruit | swidden farms |

| Pterocarpus indicus Willd. | narra | tree | Construction, Lumber | stem | forest |

| Senna alata (L.) Roxb. | akapulko | tree | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Sesbania grandiflora (L.) Pers. | katuray | tree | Food | fruit | homegarden |

| Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. | kibal | herb (vine) | Food | fruit | homegarden |

| Hypericaceae | |||||

| Cratoxylum sumatranum (Jack) Blume | baksilay | tree | Construction | stem | swidden farm |

| Lamiaceae | |||||

| Clerodendrum macrostegium Schauer | balitungtong | tree | Construction | stem | swidden farm |

| Gmelina arborea Roxb. | gmelina | tree | Construction | stem | swidden farm |

| Mentha spp. | herba buena | herb | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | samoro | herb | Food, Medicine | leaf | homegarden, swidden farm |

| Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng | oregano | herb | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Vitex negundo L. | lagundi | shrub | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Lauraceae | |||||

| Cinnamomum mercadoi S. Vidal | kalingag | tree | Construction, Medicine | stem, bark | forest |

| Litsea sp. Lam. | magurilaw | tree | Construction, Lumber | stem | forest |

| Persea americana Mill. | avocado | tree | Food, Medicine, Firewood | fruit, leaf, bark, stem | swidden farms, homegarden |

| Phoebe sterculioides (Elmer) Merr. | kaburo | tree | Construction, Lumber | stem | forest |

| Lecythidaceae | |||||

| Barringtonia acutangula subsp. acutangula (L.) Gaertn. | tipalang | tree | Construction, Medicine | stem, bark | forest |

| Lycopodiaceae | |||||

| Huperzia phlegmaria (L.) Rothm. | salanggumay | herb | Ornamental | homegarden | |

| Lygodiaceae | |||||

| Lygodium sp. Sw. | nito | shrub (liana) | Construction, Handicraft, Cultural | stem | forest |

| Malvaceae | |||||

| Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench | okra | herb | Food, Cash crop | Fruit | swidden farms, homegarden |

| Corchorus olitorius L. | saluyot | shrub | Food | leaf | homegarden |

| Diplodiscus paniculatus Turcz. | balugo | tree | Medicine | leaf | forest |

| Durio zibethinus L. | durian | tree | Food | Fruit | swidden farms |

| Hibiscus sp. | gumamela | shrub | Food, Medicine, Ornamental | flower | homegarden |

| Sterculia sp. L. | balinad | tree | Construction | stem | forest |

| Theobroma cacao L. | cacao | tree | Food, Medicine, Cash crop | fruit, seed | homegarden, swidden farms |

| Marantaceae | |||||

| Donax canniformis (G.Forst.) K.Schum. | banban | shrub | Construction | stem | forest |

| Maranta arundinacea L. | urado | herb | Food | stem | forest |

| Melastomataceae | |||||

| Melastoma malabathricum L. | saransok | shrub | Firewood | stem | swidden farm |

| Meliaceae | |||||

| Lansium parasiticum (Osbeck) K.C. Sanhi and Bennet | lanzones | tree | Food, Cash crop, Construction, Medicine, Firewood | fruit, stem | swidden farm, homegarden |

| Sandoricum koetjape (Burm.f.) Merr. | santol | tree | Food, Firewood | fruit, stem | homegarden |

| Swietenia macrophylla King | mahogany | tree | Construction, Lumber, Medicine, Firewood | stem, bark | swidden farm, forest, homegarden |

| Toona calantas Merr. and Rolfe | kalantas | tree | Lumber, Lumber | stem | forest |

| Menispermaceae | |||||

| Anamirta cocculus (L.) Wight and Arn. | bayati | shrub (liana) | Pesticide | seed | homegarden |

| Tinospora glabra (Burm.f.) Merr. | makabuhay | shrub (liana) | Medicine | stem | forest, homegarden |

| Moraceae | |||||

| Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson ex F.A.Zorn) Fosberg | kamansi/rimas | tree | Food | Fruit | swidden farms, homegarden |

| Artocarpus blancoi (Elmer) Merr. | antipolo | tree | Construction | stem | forest |

| Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. | nangka | tree | Food, Cash crop, Construction, Firewood | fruit, stem | swidden farms, homegarden |

| Artocarpus odoratissimus Blanco | marang/uloy | tree | Food, Construction | Fruit | swidden farms |

| Ficus sp. | anongo | tree | Cultural | bark | forest, swidden area |

| Ficus sp. | balite | tree | Construction, Medicine | bark, root, stem | forest |

| Moringaceae | |||||

| Moringa oleifera Lam. | malunggay | tree | Food, Medicine, Cash crop | leaves | homegarden |

| Musaceae | |||||

| Musa spp. | saging | herb | Food, Medicine, Cash crop, Fodder | fruit, leaf, sap | swidden farms, homegarden |

| Myrtaceae | |||||

| Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | eucalyptus | tree | Construction | stem | swidden farm |

| Psidium guajava L. | bayabas | shrub | Medicine | fruit, leaf | homegarden, swidden farm |

| Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels | duhat | tree | Food, Medicine | fruit, bark | swidden farms |

| Tristaniopsis decorticata (Merr.) Peter G.Wilson and J.T.Waterh. | bunglas | tree | Construction | stem | forest |

| Orchidaceae | Orchids | herb | Ornamental | homegarden, forest | |

| Oxalidaceae | |||||

| Averrhoa bilimbi L. | kalamias | tree | Food | fruit | homegarden |

| Pandanaceae | |||||

| Pandanus radicans Blanco | ulango | shrub | Construction, Cultural | leaf | riverside |

| Phyllantaceae | |||||

| Antidesma bunius (L.) Spreng. | bignay | tree | Medicine | stem | forest |

| Sauropus villosus (Blanco) Merr. | bangrat | tree | Construction | stem | swidden farm |

| Piperaceae | |||||

| Piper betle L. | mam-in | herb | Medicine, Cultural | leaf | forest, homegarden, swidden farms |

| Piper nigrum L. | paminta | herb | Food | fruit | swidden farms |

| Poaceae | |||||

| Bambusoideae | kawayan | shrub | Food, Construction, Firewood, Handicraft | stem | forest, swidden farm |

| Coix lacryma-jobi L. | adlay/tigbi | herb | Food | fruit | swidden farms |

| Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf. | tanglad | herb | Food, Medicine | leaf | homegarden, swidden farm |

| Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn. | parag-is | herb | Medicine | root | homegarden |

| Flagellaria indica L. | balingway | shrub (liana) | Construction, Handicraft | stem | forest |

| Gigantochloa sp. Kurz ex Munro | bolo | shrub | Construction | stem | forest, swidden farm |

| Imperata cylindrica (L.) Raeusch. | cogon | herb | Construction, Medicine | root, leaf | swidden farm |

| Oryza sativa L. | palay | herb | Food | fruit | rice field |

| Saccharum officinarum L. | tubo | shrub | Food, Medicine | stem | homegarden, swidden farm |

| Schizostachyum brachycladum (Kurz) Kurz | buho | tree | Construction | stem | swidden farm |

| Setaria italica (L.) P.Beauv. | bikaka | herb | Medicine | fruit | homegarden |

| Zea mays L. | mais | herb | Food | fruit | swidden farms |

| Polygalaceae | |||||

| Xanthophyllum bracteatum Chodat | kangmun | tree | Construction | stem | forest |

| Rhamnaceae | |||||

| Alphitonia zizyphoides (Sol. Ex Spreng.) A.Gray | tangulay | tree | Construction, Lumber, Medicine | stem, bark | swidden farm, forest |

| Rosaceae | |||||

| Rosa spp. | rosas | shrub | Ornamental | flower | homegarden |

| Rubiaceae | |||||

| Coffea canephora Pierre ex A.Froehner | kape | tree | Food, Construction, Firewood, Cash crop | stem, seed | swidden farm |

| Gardenia jasminoides J.Ellis | rosal | shrub | Ornamental | flower | homegarden |

| Ixora sp. | santan | shrub | Ornamental | homegarden | |

| Rutaceae | |||||

| Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle | dayap | tree | Food, Medicine | fruit | homegarden |

| Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr. | lukban | tree | Food, Medicine | fruit | homegarden |

| Citrus reticulata Blanco | sinturis | tree | Food, Firewood | fruit, stem | swidden farms |

| x Citrufortunella microcarpa (Bunge) Wijnands | kalamansi | tree | Food, Medicine, Cash crop, Firewood | fruit | swidden farms, homegarden |

| Sapindaceae | |||||

| Nephelium lappaceum L. | rambutan | tree | Food, Cash crop, Firewood | fruit | swidden farms |

| Sapotaceae | |||||

| Chrysophyllum cainito L. | kaimito | tree | Food, Medicine | fruit, leaf | homegarden |

| Solanaceae | |||||

| Capsicum anuum L. | sili | herb | Medicine | homegarden | |

| Nicotiana tabacum L. | tabako/sadiwa | herb | Cultural, Pesticide | leaf | swidden farm, homegarden |

| Solanum americanum Mill. | barakway/unti-an | herb | Food, Medicine | leaf | swidden farm, homegarden |

| Solanum lycopersicum L. | kamatis | herb | Food | fruit | homegarden |

| Solanum melongena L. | talong | herb | Food, Cash crop | fruit | swidden farm, homegarden |

| Theaceae | |||||

| Ehretia microphylla Lam. | tsaang gubat | tree | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Urticaceae | |||||

| Elatostema sp. | taba-taba/ambubuway | tree | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Poikilospermum suaveolens (Blume) Merr. | anopol | tree | Medicine | stem | forest |

| Verbenaceae | |||||

| Premna odorata Blanco | alagaw | shrub | Medicine | leaf | homegarden |

| Zingiberaceae | |||||

| Alpinia galanga (L.) Willd. | tagibulog | herb | Medicine, Cultural | stem | forest |

| Alpinia purpurata (Vieill.) K.Schum. | luyang pula/itim | herb | Medicine | stem | forest |

| Curcuma longa L. | luyang dilaw | herb | Food, Cash crop, Medicine | srem | homegarden, swidden farm |

| Kaempferia galanga L. | kusor | herb | Medicine | stem, leaf | homegarden |

| Zingiber officinale Roscoe | luya | herb | Food, Cash crop, Medicine | stem | homegarden, swidden farm |

| [unidentified] | aram | Construction | swidden farm | ||

| [unidentified] | mangume | tree | Construction | stem | swidden farm |

| [unidentified] | ilupakon | tree | Construction | stem | forest |

| [unidentified] | inggiw | Construction | stem | forest | |

| [unidentified] | pakpak | tree | Construction | stem | forest |

| [unidentified] | talwan | Construction | stem | forest | |

| [unidentified] | batoryon | Medicine | stem | forest | |

| [unidentified] | dawuy | Medicine | sap | forest | |

| [unidentified] | guta | Medicine | bark | forest | |

| [unidentified] | lawuy | Food, Medicine | root | forest | |

| [unidentified] | salugim | tree | Medicine, Construction | stem | forest |

| [unidentified] | aribagraw | Medicine | leaf | homegarden | |

| [unidentified] | gita | tree | Medicine | sap | homegarden |

| [unidentified] | sanduk-sandukan | herb | Medicine | homegarden | |

| [unidentified] | taka-taka | Medicine | homegarden | ||

| [unidentified] | anigyaw | tree | Construction | stem | forest |

| [unidentified] | anlaway | tree | Construction | stem | riverside |

| [unidentified] | apilan | Food, Medicine | stem | swidden farm | |

| [unidentified] | lusong | Handicraft | stem | forest | |

| [unidentified] | marayaw | Cultural | |||

| [unidentified] | pagsibar | Medicine | leaf | swidden farm | |

| [unidentified] | singapor | Food | fruit | ||

| [unidentified] | atsiba | Medicine | homegarden | ||

| [unidentified] | bakus kabayo | Construction | stem | riverside |

| Botanical Name/family | Local Name | Part/s Used | Medical Use/s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acoraceae | |||

| Acorus calamus L. | lubidan/dusol | stem | for stomachache |

| Amaranthaceae | |||

| Amaranthus spinosus L./ A. cruentus L. | uray | root | abortive |

| Anacardiaceae | |||

| Mangifera indica L. | mangga | bark | for stomachache |

| Annonaceae | |||

| Annona muricata L. | guyabano | leaf/shoot, bark | directly applied for headache and stomachache (leaf/shoot); bark as a decoction for diarrhea |

| Apocynaceae | |||

| Voacanga globosa (Blanco) Merr. | aliwas | leaf | For strangury/stomachache |

| Jasminum sambac/Ervatamia pandacaqui | kampupot | sap | for wounds |

| Alstonia macrophylla Wall. ex G.Don | batino | bark | decoction to alleviate fever |

| Araceae | |||

| Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott | gabi | leaf | poulticed and applied on wound to stop bleeding; also used in treating athlete's foot |

| Arecaceae | |||

| Areca catechu L. | bunga | stem; fruit | for usog; fruit used as a purgative |

| Cocos nucifera L. | niyog | seed | juice (endosperm) used to treat UTI |

| Asparagaceae | |||

| Dracaena angustifolia (Medik.) Roxb. | tibanwa | bark, leaf | for fracture (bark); leaf heated and applied to affected area for body pain |

| Asteraceae | |||

| Ageratum conyzoides (L.) L. | bugasnay | leaf | pound, heated and directly applied to wound to stop bleeding; also for diarrhea |

| Artemisia vulgaris L. | kamarya | leaf | decoction for stomach pains; can also be applied directly on stomach |

| Blumea balsamifera (L.) DC. | sambong | leaf | decoction for cough, kidney ailments, hyperacidity; leaf can also be directly applied to alleviate fever |

| Chrysanthemum indicum L. | mansanilya | leaf | decoction for flatulence |

| Mikania cordata (Burm.f.) B.L.Rob. | uting | leaf | poultice applied to wounds |

| Balsaminaceae | |||

| Impatiens balsamina L. | kamantigue | fruit | crushed and placed on the stomach for the mother for the infant come out from the womb |

| Boraginaceae | |||

| Ehretia microphylla Lam. | tsaang gubat | leaf | used to treat stomach pains; purgative in children |

| Heliotropium indicum L. | aritis-aritisan | leaf | heated and extracted for asthma and cough |

| Bromeliaceae | |||

| Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. | pinya | young leaf | for boils |

| Burseraceae | |||

| Canarium sp. | sahing | sap | sap is chewed for binat |

| Caricaceae | |||

| Carica papaya L. | papaya | leaf, sap | leaf is directly applied on wounds to stop bleeding; sap is used to stop milk production when weaning |

| Combretaceae | |||

| Combretum indicum (L.) DeFilipps. | niyog-niyogan | root | decoction used to treat UTI |

| Convolvulaceae | |||

| Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. | kamoteng baging | shoot | increase blood level |

| Crassulaceae | |||

| Bryophyllum pinnatum (Lam.) Pers. | kataka-taka | leaf | directly applied for headache; can also be extracted for burns and bee sting |

| Cucurbitaceae | |||

| Momordica sp. | ampalayang ligaw | fruit | for diabetes |

| Momordica charantia L. | ampalaya | fruit | anti-diabetes |

| Euphorbiaceae | |||

| Manihot esculenta Crantz. | balinghoy | leaf | whipped on the stomach as a cure against flatulence |

| Euphorbia hirta L. | tawa-tawa | flower | for dengue |

| Jatropha curcas L. | tuba | leaf | directly applied to fracture |

| Fabaceae | |||

| Caesalpinia sappan L. | sibukaw | bark | prepared as decoction to increase blood levels; used as a massage for fracture |

| Senna alata (L.) Roxb. | akapulko | leaf | applied to wounds; for fungal skin diseases |

| Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp. | kakawate | leaf | extract to treat scabies; also for headache |

| Mimosa pudica L. | makahiya | root | decoction for urinary problems |

| Caesalpinia sappan L. | sibukaw | bark | for fracture |

| Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp. | kakawate | leaf | extract to treat scabies; also for headache |

| Lamiaceae | |||

| Mentha spp. | herba buena | leaf | used to treat cough of newborn babies; also for body pain and stomachache |

| Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng | oregano | leaf | extract/decoction used for cough, colds, stomach pains, bronchitis |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | samoro | leaf | decoction for diarrhea, vomiting and headache |

| Cinnamomum mercadoi S.Vidal | kalingag | bark | decoction for stomachache and bleeding |

| Vitex negundo L. | lagundi | leaf | decoction for cough, fever and asthma |

| Lauraceae | |||

| Persea americana Mill. | avocado | leaf, bark | decoction for stomach pains, diarrhea and vomiting |

| Malvaceae | |||

| Diplodiscus paniculatus Turcz. | balugo | leaf | leaf directly applied for fever and headache |

| Theobroma cacao L. | cacao | leaf | for headache |

| Hibiscus sp. | gumamela | flower | for boils |

| Meliaceae | |||

| Lansium parasiticum (Osbeck) K.C. Sanhi and Bennet | lanzones | bark | for diarrhea |

| Swietenia macrophylla King | mahogany | bark | decoction for stomach pains |

| Menispermaceae | |||

| Tinospora glabra (Burm.f.) Merr. | makabuhay | stem | decoction for cough and stomachache |

| Moraceae | |||

| Ficus sp. | balite | bark | bark directly applied for fracture and sprain |

| Moringaceae | |||

| Moringa oleifera Lam. | malunggay | leaf | increases blood levels |

| Musaceae | |||

| Musa spp. | saging | leaf, sap | leaf directly applied to forehead to alleviate fever; sap is used to treat oral thrush |

| Myrtaceae | |||

| Psidium guajava L. | bayabas | leaf | for wound cleaning, diarrhea and stomach ache |

| Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels | duhat | bark | decoction for diarrhea |

| Phyllantaceae | |||

| Antidesma bunius (L.) Spreng. | bignay | bark | decoction for body pains |

| Piperaceae | |||

| Piper betle L. | mam-in | leaf | directly applied for fever, pambuga*; poultice is also mixed with lime for stomachache and cough |

| Poaceae | |||

| Setaria italica (L.) P.Beauv. | bikaka* | root | for stomachache |

| Imperata cylindrica (L.) Raeusch. | cogon | root | for strangury |

| Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn. | parag-is | root | decoction for strangury |

| Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf. | tanglad | leaf | used as a bath to remove binat**; decoction used for fever, cough, urinary problems; also lowers blood pressure |

| Saccharum officinarum L. | tubo | stem | heated and extracted to treat neck pains |

| Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf. | tanglad | leaf | used as a bath to remove binat**; decoction used for fever, cough, urinary problems; also lowers blood pressure |

| Saccharum officinarum L. | tubo | stem | heated and extracted to treat neck pains |

| Rhamnaceae | |||

| Alphitonia zizyphoides (Sol. ex Spreng.) A.Gray | tangulay | bark | for cough |

| Rutaceae | |||

| Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle | dayap | fruit | for asthma and cough, used as a luop*** |

| Citrus microcarpa | kalamansi | fruit, leaf | for cough; leaf is crushed and smelled to cure diziness |

| Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr. | lukban | leaf | decoction used against binat** |

| x Citrufortunella microcarpa | kalamansi | fruit, leaf | for cough; leaf is crushed and smelled to cure diziness |

| Sapotaceae | |||

| Chrysophyllum cainito L. | kaimito | bark, leaf | for diarrhea |

| Solanaceae | |||

| Solanum americanum Mill. | barakway/unti-an | fruit, leaf | for rabies |

| Capsicum anuum L. | sili | leaf | extracted or applied as poultice for wounds and boils |

| Solanum nigrum L. | barakway/unti-an | leaf | decoction/eaten as raw for dog bite |

| Urticaceae | |||

| Elatostema sp. | taba-taba/ambubuway | leaf | for strangury |

| Poikilospermum suaveolens (Blume) Merr. | anopol | stem | for eye diseases |

| Verbenaceae | |||

| Premna odorata Blanco | alagaw | leaf | taken as a decoction for cough |

| Zingiberaceae | |||

| Alpinia purpurata (Vieill.) K.Schum. | luyang pula/itim | rhizome | used as a contraceptive |

| Alpinia galanga (L.) Willd. | tagibulog | root | for stomachache |

| Curcuma longa L. | luyang dilaw | rhizome | extract for cough, flatulence, fever, asthma; can also be mixed with kalamansi and lime to treat skin diseases |

| Kaempferia galanga L. | kusor | leaf | extract for cough and stomachache |

| Zingiber officinale Roscoe | luya | rhizome | for fever, stomachache, sore throat, cough; pambuga against balis**** |

| Curcuma longa L. | luyang dilaw | rhizome | extract for cough, flatulence, fever, asthma; can also be mixed with kalamansi and lime to treat skin diseases |

| [unknown] | batoryon | fruit | for body pains |

| [unknown] | dawuy | sap | for mouthsore |

| [unknown] | guta | bark | for fever and stomachache, bark directly applied while warm |

| [unknown] | lawuy | root | burned; used as a purgative |

| [unknown] | salugim | mast/bark? | for balis**** |

| [unknown] | aribagraw | leaf | directly applied to head for fever and headache |

| [unknown] | gita | sap | for stomachache |

| [unknown] | sanduk-sandukan | leaf | directly applied for stomachache |

| [unknown] | taka-taka | leaf | leaf directly applied to forehead to alleviate fever |

* Buga (pambuga) is a practice wherein the plant part is being chewed by the healer and then will be spitted to the patient.

** Binat is a local term for relapse.

*** Luop is a practice wherein the plant part is burned and the patient is exposed to the smoke.

**** Balis or usog is a condition wherein a person (usually an infant or a child becomes distressed/afflicted, which is believed to be caused by meeting a stranger. There is no equivalent term in Western medicine for these words.