Elaborating the Aquapelagic Imaginary: Catalina Island, Tourism and Mermaid Iconography

University of Technology Sydney, Australia prhshima@gmail.com

Abstract

This article revisits and updates a discussion of the cultural function and prominence of the mermaid in 20th and 21st century Catalina Island (California) that originally appeared in the journal Contemporary Legend in 2013. Drawing on recent critical-theoretical work on the concept of the aquapelago and of the aquapelagic imaginary, I examine the manner in which the deployment of mermaid imagery on Catalina island is related to the location’s orientation to coastal and marine tourism. In particular, I examine the interplay between the conscious deployment of iconography and broader patterns of social use, examining the manner in which the local aquapelagic imaginary has been developed as a cultural asset in the island’s destination branding and more general representation of place.

Keywords

Catalina Island, aquapelagic imaginary, tourism, mermaids

The Aquapelago and the Aquapelagic Imaginary

The concept of the aquapelago was developed in the early 2010s by authors associated with the journal Shima to refer to terrestrial and marine spaces integrated by human livelihood activities (see Shima aquapelago anthology, n.d.). A key aspect of the concept is that the aquapelago is not a physical-geographical entity (such as an archipelago or peninsula) but rather a socio-cultural-economic one generated in a particular space in a particular period.1 As such, the aquapelago is constituted by human interaction with (and within) littoral and aquatic environments, perceived through subjective and social experience and subsequently represented and elaborated through culture. The concept of the “aquapelagic imaginary” is a more recent development and, in its initial iterations, referred to the manner in which folkloric figures such as the mermaid can be considered to reflect communities’ “engagements with their aquapelagic locales” in a manner that reflects upon and transcends “perceptions of the limits of human presence in and experience of aquatic spaces” (Hayward, 2018: 1-2). As Greenwood and Hayward (forthcoming 2020) discuss, the aquapelagic imaginary can be understood as a subset of a broader “social imaginary” that operates as a historically determined and “enabling but not fully explicable symbolic matrix within which a people imagine and act as world-making collective agents” (Gaonkar, 2002: 1). Like all social entities the social and aquapelagic imaginaries are premised on individual subjective experiences. In the modern era, in particular, they are “carried in modes of address, stories, symbols, and the like” in public culture that “are imaginary in a double sense: they exist by virtue of representation or implicit understandings… and they are the means by which individuals understand their identities and their place in the world” in particular locales at particular times (Gaonkar, 2002: 4).

In the contemporary era, the field of popular culture constituted by audio-visual media, print media and the internet (etc.) acts as an arena for various expressions of the social imaginary. Within this, various folkloric figures, motifs and tropes appear as manifestations of what the Russian Laboratory of Theoretical Folkloristics (2104) has termed media-lore. Popular culture intersects and overlaps with other more functional practices, such as advertising and public relations, and social media in various ways. Rather than perceiving the former as separate spheres, we can understand them as dialogic, cross-referential systems. In certain instances, such as the representation of island, coastal and marine locales, these forms can manifest the aquapelagic imaginary. As this article demonstrates, the promotion of Catalina Island within tourism discourse and allied popular cultural practices has been heavily premised on a vision of the island’s coastal and marine locale as an integrated and highly facilitated leisure space. Unsurprisingly in this regard, the marketing and destination branding of the island has deployed traditional aquapelagic motifs in modern media-loric contexts. Indeed, as I have argued elsewhere (Hayward, 2012) mermaids have become such a prominent motif in destination branding and vernacular culture that they can be considered as a local intangible heritage asset.

Catalina Island

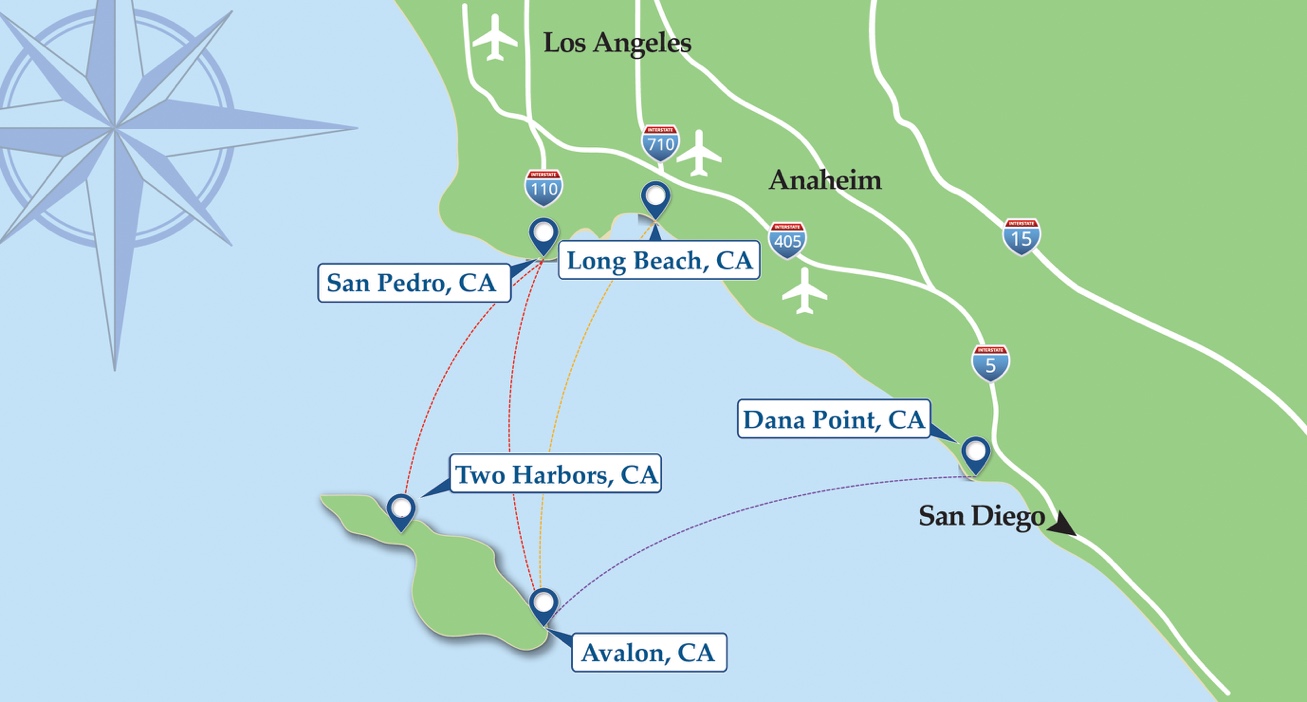

Catalina Island, located 75 kilometres (47 miles) south-west of Los Angeles (Fig. 1), has a permanent population of c4000 residents, mainly concentrated around the east coast port of Avalon. The island’s principal industry is tourism, with over 1 million tourists visiting per year (Catalina Island CC&VB, 2019a). Archaeological research suggests that human inhabitation of the island dates back to around 5,000 BCE. At time of initial European exploration of the region in the 16th Century the island was home to an indigenous community known as the Pimugan (although it is unclear as to what relationship this population had to earlier inhabitants).2 The island was claimed for Spain in 1542 but this was largely notional, with the indigenous islanders’ main interaction with westerners commencing in the early 1800s when Russians and Americans began to frequent the area to harvest and trade for sea otter pelts. The Pimugan population was rapidly depleted by introduced diseases and traditional livelihood patterns were so severely impacted that remaining indigenous families relocated to the mainland in the 1820s. While Catalina Island was included within Mexico when it proclaimed its independence from Spain in 1821, minimal development occurred until California and its offshore islands were acquired by the United States in 1848. In 1864 concerns over the number of squatters moving on to the island led the US Government to expel all residents, aside from a few ranchers, and to establish a military garrison to ensure stability. By the late 1800s Catalina was increasingly visited by tourists travelling from the Californian coast on yachts during the summer season and the island’s first hotel was established in Avalon in 1887. Avalon’s tourism facilities gradually increased in size and scale until they were damaged by a major fire in 1915. In 1919 the chewing gum millionaire William Wrigley Junior acquired control over the island and established a range of facilities that formed the basis of the island’s subsequent operation as a tourist attraction, capitalising on its coastal reefs, abundant marine life, safe anchorages and beaches.

Mermaid Imagery on Catalina Island

Mermaid imagery3 developed on Catalina in the early 20th Century as both a local manifestation of general western traditions associated with marine locales and as a result of the island’s use as a centre for film production. One of the earliest recorded examples of mermaid branding has been identified by local historian Chuck Liddell as the name of one of the island’s first glass-bottomed rowboats used to show tourists the local reefscape - ‘The Mermaid’, c1910 (personal communication, October 2013). Subsequent early uses took the forms of logos, art and craftwork of various kinds. Around the same time, Catalina’s proximity to Hollywood saw it used as the location for a number of film productions, some of which featured mermaids and related aquatic females. Along with the popularity of English language translations of Hans Christian Andersen’s acclaimed short story ‘Den lille Havfrue’ (1837) in the United States, the mermaid’s profile in popular culture was significantly boosted through the career of specialist swimmer, diver and film actress Annette Kellerman, who performed in live aquatic cabarets before appearing in her first mermaid-themed vehicles, The Mermaid and The Siren of the Sea in 1911 (directors unknown). She followed these with Neptune’s Daughter (Herbert Brenon, 1914), which was shot in Bermuda with additional scenes filmed around Catalina, and Queen of the Sea (John Adolfi, 1918). The success of these films prompted a series of similar productions, several of which were shot wholly or in part on the shores of Catalina Island, including The Sea Maiden (Rollin Sturgeon, 1913)4 and Sirens of the Sea (Allen Holubar, 1917).5

While there is no information on the specific decision-making process involved, the choice of a mermaid image to adorn the entrance to the island’s biggest and most prestigious building, the Casino, which opened in 1929 (see Moore, 2002), can be seen to reflect and be informed by the mermaid’s previously described popular cultural currency and by Avalon’s orientation to aquatic tourism. Despite its name, the Casino was an entertainment (rather than gambling) venue and was designed and decorated on a lavish scale at a cost of over $2 million. The mermaid image (Fig. 2) and other Casino murals were designed by Russian-American artist and interior designer John Gabriel Beckman. At Wrigley’s request, the murals had an aquatic theme and Beckman explored the coastline in glass bottom boats to gain inspiration from the island’s reefs and kelp forests (Moore, 2002: 47). The mermaid image above the Casino’s entrance was completed as a painted mural in 1929 and offered a striking revision of standard mermaid imagery. Rather than commencing the lower fish half of its subject’s physique around the navel, Beckman’s stylised Art Deco image commences the fishtail at the mermaid’s upper thighs, showing a dark triangle above, suggesting an anatomical aspect eschewed in the more standard mermaid figure. As the central image above the Casino’s entrance, within a suite of highly stylised representations of marine flora and fauna that has been labelled “Aquarium Deco” (ADG, nd), the mermaid mural is manifestly modern in a manner that reflected a particular period of liberalism in American popular culture, and in Hollywood in particular, that was significantly reversed in the 1930s.6

As a result of its exposure to the elements, the mural gradually deteriorated until a locally funded initiative brought Beckman back to the island to work with ceramicist Richard Keit to render the image in tile, in the form it appears today. Media reports of the opening of the restored mural, such as that extracted below, emphasise the image’s iconic status on the island and the impact of the restoration:

Before the restoration, years of decay caused by the salty island air eating away at the painted surface of the entrance had transformed Beckman's beautiful mermaid into a grotesque green goddess. When the mural was unveiled again last summer, however, the mermaid seemed to exude an exotic serenity that drew an emotional response from the 400 in attendance, including William Wrigley, president of the Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co., and president of the Santa Catalina Island Co., which owns the Casino. Wrigley's grandfather, William Wrigley Jr., had built the Casino and commissioned the original murals. "The restoration is absolutely everything I expected and perhaps more," Wrigley says. (Henson, 1987: online)

Established as a key—and increasingly iconic—figure in Avalon through its prominence on the Casino’s façade, the mermaid was also associated with Catalina through a series of subsequent popular cultural phenomena. While the cinematic vogue for mermaids declined in the 1930s and 1940s, similar associations were promulgated by the female swimming stars who performed in venues such as the Aquacade theatre constructed on an artificial site (known as Treasure Island) in San Francisco Harbour in 1940 as part of the Golden Gate International Exhibition.7 One of the most celebrated female aquatic performers of the time was Esther Williams, who first attracted attention by her performances at the Aquacade and went on to appear in a series of films that showcased her aquatic abilities (such as Thrill of a Romance [Richard Thorpe, 1945]). In 1947 Williams attracted publicity for herself and Catalina Island by participating in and winning a swimming race over the 42 kilometres (26 miles) between Catalina and Long Beach. Her association with the island was commemorated in 2019 with an exhibition of her life and work at the Catalina Island Museum entitled ‘The Swimming Queen of the Big Screen’.8

American cinema returned to mermaids in the late 1940s with Mr Peabody and the Mermaid (Irving Pichel, 1948) and a number of subsequent films, including the comedy feature The Glass Bottom Boat (Frank Tashlin, 1965), which was set around Avalon Bay and starred Doris Day as the daughter of a tour boat operator who entertains his customers by swimming around dressed as a mermaid. Two years later Catalina Caper (Lee Sholem, 1967) introduced a comic crime narrative set on the island with an animated title sequence depicting a curvaceous red-haired mermaid attracting the attention of a scuba diver. Fittingly enough, given the media history sketched above, the first Catalina Island Film Festival, held in 1979, was promoted by a mermaid-themed poster. A further loop between cinematic representations, Catalina Island and the mermaid mural that adorns the Casino’s entrance was forged by the Disney Corporation, which launched The Little Mermaid: Ariel’s Beginning (Peggy Holmes, 2008) at the Casino in August 2008.9

Local Catalina images

While many of the earliest visual and nomenclative references to mermaids on the island were ephemeral and have only been preserved in photographs and/or personal recollections, the contemporary visual landscape of the island offers a range of (extant) mermaid images. Along with displays of standard mermaid souvenir product (of the type sold in other US coastal locations) there are a number of images with more specific local relevance. Variations on Beckmann’s iconic Casino mermaid image have been particularly prominent, such as the poster for Catalina’s 2000 Blues festival (Fig. 3), which modernises the iconic Casino mermaid through her association with a Fender electric guitar.

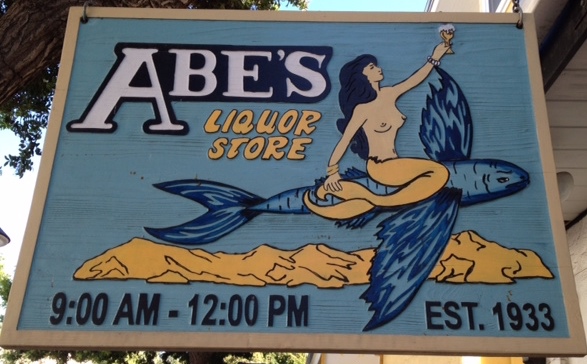

A number of local images also draw on other features of the Casino’s murals in patterns of serial association. The Casino also features a small image of a young female figure riding a flying fish (a species commonly associated with the island) (Fig 4). While not a mermaid, the female figure has a clear resemblance to the main mermaid mural image reproduced in Fig. 2 (above).

Fig. 5 adapts the Casino image to promote a liquor store by showing a mermaid holding a glass aloft while riding a flying fish soaring over a representation of the island.10

The patterns of image association and reference described above represent a local vernacular practice, playing with both local referent icons (such as the Casino murals) and more general western mermaid imagery. While not so visible as the public images reproduced above, a number of homes and rental apartments also feature mermaid themed murals, artworks and artefacts. One rental property, named La Casa Sirena (The Mermaid House) declares its design theme on its promotional webpage: “La Casa Sirena features Catalina and Mermaid-themed décor, offering fun for the whole family… as the name suggests, there are plenty of mermaids to be found!”. The property’s webpage shows photographs of the apartment’s interior liberally decorated with mermaid images, including tiled renditions of both John William Waterhouse’s well-known painting ‘A Mermaid’ (1901) and Beckman’s Casino figure.11

Mermaid associations are not only limited to interior décor. The Aurora Hotel and Spa,12 for instance, promotes its “signature massage” in the following terms:

Make sure and book Aurora's signature massage, the Mermaid's Kiss. It is a blend of Swedish, deep tissue and Reiki massage styles combined with Thai stretching and body work that will remind your body what it means to truly relax. (nd, online13)

While the above-mentioned massage might be considered as a performance activity, another facet of Catalina’s engagement with mermaid imagery and associations is more significant for its engagement with the aquatic environment. Over the last decade, as a local manifestation of an international trend, several operators have offered packages that allow customers (usually young girls) to swim, dive and be photographed around the island in mermaid costumes. Along with Bryn Starr’s Mermaid Island Tours, Virginia Hankins activity as a character known as ‘Catalina Mermaid’ offers a significant engagement and representation of the aquapelagic space of the island. Her Facebook page describes her as “a swimming mermaid character based in the city of Avalon, California USA on Santa Catalina Island… She resides under the famous Avalon Casino building and enjoys swimming with SCUBA divers who enjoy diving the Channel Islands”. While the residency referred to is humorous, Hankins’ persona draws on a family connection with the region:

My love of Santa Catalina Island goes back to my childhood and the history of the last three generations of my family… I remember being on the pier with my father waiting for the boat back to the mainland and being absolutely mesmerized by flying fish leaping in the water under the silver light of a full moon. It was surreal to me; I had never seen anything more magical in my life at that point. (Personal communication, November 2013)

Hankins has been notable for her attachment to the locale and her attempts to promote respect for local aquatic ecology:

To me the Channel Islands, and particularly Catalina Island, are the jewel box of the ocean… I looked around at other professional mermaids in the world and noticed that they were normally "Mermaid (insert name of actress here)." Exceedingly few had any ecological tie in to their oceans or characters… I could easily be "Mermaid Virginia" but how would that benefit the very place that I wanted children to see? "Catalina Mermaid," however, puts the place on the lips of the children... By tying positive emotions to facts and real places Catalina Mermaid promotes eco-tourism by inspiring them to visit and sparking an open curiosity. (ibid)

The range of ideas and associations brought to Hankins’ work is epitomised by her Facebook profile image (Fig. 6), which restages Beckmann’s iconic Casino image in the very kelp forests that the artist explored by glass bottomed boat in the late 1920s to gain inspiration.

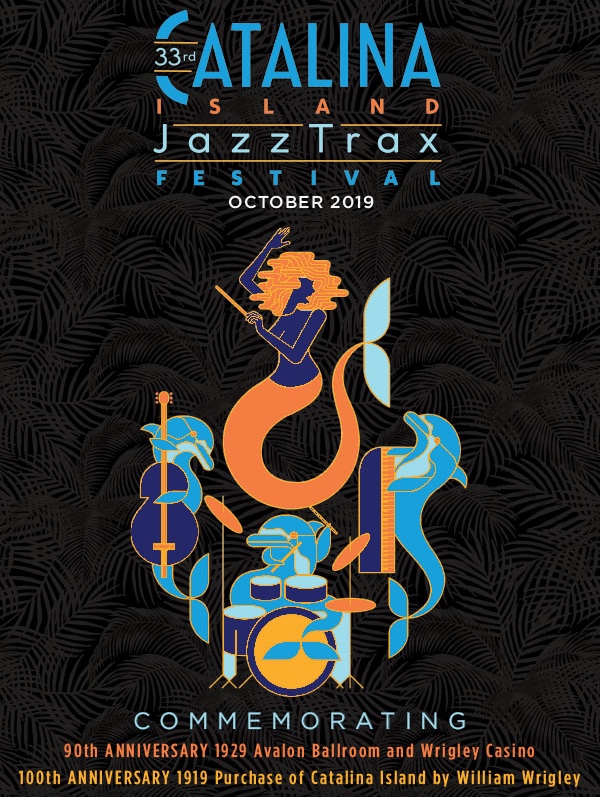

The year 2019 provided an opportunity to celebrate of the island’s tourism history—and its use of mermaid imagery—being the 100th anniversary of Wrigley’s purchase of the island and the 90th anniversary of the opening of the Casino. A variety of events were organised that deployed mermaid imagery in ways that related to the island’s and the Casino’s history. One notable image that drew on imagery from the Casino’s “Aquarium Deco” designs and the live music played there during its heyday in the 1930s-1950s was used to promote the 33rd Catalina Jazztrax Festival (Fig. 7). Referred to in associated publicity as “Ms. Mermaid Conductor and her Merry Little Band of Dolphins”, the image placed the mermaid in command of the musical entertainment offered by her fellow denizens of the Bay in a light-hearted, cross-species assemblage.

One of the most novel deployments of the mermaid image on the island to date has provided a different socio-cultural articulation of Catalina’s aquapelagic imaginary. In 2016 the Catalina Island Museum publicised an “accumulative community project” to celebrate the Mexican Día de los Muertos (‘Day of the Dead’) festival. Using what the event’s promotional poster described as a “Catalina twist,” the project involved the representation of a mermaid in skeletal form (Fig. 8) as the island’s entry into the Big Draw LA competition.15 Through its combination of a traditional Mexican calavera (decorated skull), an upper human skeleton and a mermaid fishtail, the striking image, designed by museum director Julie Perlin Lee and artist David Lee, invites comparison to similar images of the sirena produced by various Mexican and American artists in recent years16 that are very different to those of the western mermaid.

The choice of the image performed a valuable function in highlighting the Mexican presence on Catalina Island. As discussed in the Introduction to this chapter, the United States acquired Catalina Island, together with mainland California, from Mexico in 1848. The contemporary Mexican presence dates back from the 1920s, when Mexicans were brought in to establish resort facilities and subsequently work at them. In the post-War period the continuing population of Mexican-Americans was added to by illegal immigrants who have mainly found low-paid employment in service industries.17 Despite occasional attempts to identify and deport illegal residents, the Mexican/Hispanic population of the island is now well-established and comprises over 50% of the local population, with many originating from Jalisco state, on Mexico’s mid-west coast (Contreras, 2007: online). The blending of Catalina Island’s tradition of depicting Western-style mermaids with Mexican festival imagery links the former to the tradition of sirena imagery in Mexican culture, in general, and to traditions and modern innovations in Jalisco state, in particular.18 While Catalina’s Mexican/Hispanic population have primarily provided labour to support the island’s aquapelagic tourism, rather than being active in cultural production, the Big Draw sirena suggests a different imagination of the mermaid and what and who she represents.19

Conclusion

The mermaid has been a prominent motif for Catalina Island’s tourism industry for over ninety years. Her associations are rich and complex. Her status as an established folkloric figure suggests a pre-industrialised past, remote from the hustle and bustle of contemporary Los Angeles and San Diego, and her mythical status as a denizen of the deep suggests an organic oceanic space that can be can easily accessed from the California coast. The aquapelagic imaginary operates in a dual form in this context. It exists as an aggregate of representations (and of the paradigms and assumptions that underlie these) and as a means of asserting a particular perspective that serves the needs and aspirations of those involved in developing local resources. From the design of Wrigley’s Casino in 1929 through to re-articulations of mermaids and related aquatic imagery in more recent visual material, there is a continuous tradition of cultural production that elaborates the aquapelagic imaginary on and around the island. The dialogic, cross-fertilising involved in this practice escapes the bounds of functionality (of the mermaid as a purely logo-centric entity) and generates a diverse range of interpretations. These multiple reversionings both contribute to the figure’s canon and provides a modern imagination of a particular aquapelagic space. The impetus behind the manifestation of the aquapelagic imaginary on Catalina Island may be significantly different to well-established folkloric practices such as the association and symbolism between ningyo no miira (mermaid-like) artefacts, temples, sacred sites and pilgrimage and tourist routes around Lake Biwa in Japan (Suwa, 2018) but, it nevertheless, shares a common aspect. Like the Japanese region, the sign and symbolic resonance of the mermaid have been aggregated with places and practices around Catalina in a manner that assembles these as a cultural land-/seascape. Through the reproduction of signs and re-enactment of associations, the aquapelagic space of Catalina generated as a tourism livelihood activity is invested with broader cultural associations, manifesting the aquapelagic imaginary in a modern and highly commercialised context. Unlike Lake Biwa’s ningyo no miira artefacts, whose ancient materiality is key to their significance, Catalina’s key evocations of local aquapelagism adorn the Casino façade, domestic interiors, Catalina Mermaid’s Facebook page, the ephemeral media of event posters and similar artefacts. Media-lore articulated in these contexts thereby provides a modern manifestation of the aquapelagic imaginary just as active and vital as more traditional uses.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Alan Barlow, Gail Fornasiere, Virginia Hankins, Chuck Liddell and Wendy Teeter for their assistance with research for this article and to Rosa and Amelia Coyle-Hayward for accompanying me on fieldwork.

Endnotes

References

- ADG (American Design Guild) (undated). Hall of Fame: John Gabriel Beckman. https://adg.org/awards/hall-of-fame/john-gabriel-beckman/.

- Andersen, H.C., 1837. Den lille Havfrue. Copenhagen: C.A. Reitzel. (Unattributed) English translation (as ‘The Little Mermaid’) archived online by Project Gutenberg: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/27200/27200-h/27200-h.htm#li_mermaid.

- Catalina Island Chamber of Commerce & Visitors Bureau, 2019a. Catalina Island Visitor Statistics. https://www.catalinachamber.com/community-information/catalina-visitor-statistics/.

- Catalina Island Chamber of Commerce & Visitors Bureau, 2019a. Esther Williams: The Swimming Queen of the Big Screen. https://www.catalinachamber.com/event/esther-williams%3A-the-swimming-queen-of-the-big-screen-exhibition/557/.

- Catalina Mermaid, 2013. Facebook page. https://www.facebook.com/CatalinaMermaid.

- Contreras, A.F., 2007. Mexican Workers Provide a Resort Island’s ‘Backbone’. New York Times May 22. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/22/us/22avalon.html.

- Gaonkar, D.P. (2002) ‘Towards New Imaginaries’, Popular Culture v4 (1). 1-19.

- Greenwood, F. and Hayward, P., forthcoming 2020. Ningen: The context and generation of media-lore concerning a giant, sub-Antarctic, aquatic humanoid. Shima 14 (1).

- Hayward, P, 2012. Aquapelagos and Aquapelagic Assemblages. Shima 6 (1). 1-10.

- Hayward, P, 2013. Englamoured: Mermaid iconography as a contemporary heritage asset for Catalina Island. Contemporary Legend series 3 (3). 39-62.

- Hayward, P, 2017. Making a Splash: Mermaids (and Mermen) in 20th and 21st Century Audiovisual Media. New Barnet: John Libbey & Co.

- Hayward, P, 2018. Mermaids, Mercultures and the Aquapelagic Imaginary. Shima 13 (1). 2-11.

- Henson, S, 1987. A Second Life: Restoring a 57-Year-Old Mural on Santa Catalina Island Was a Labor of Love, Science and Art. Los Angeles Times, January 29: http://articles.latimes.com/1987-01-25 /magazine/tm-5604_1_murals.

- Kerr, S.L. and Hawley, G.M., 2002. Population replacement on the southern Channel Islands: New evidence from San Nicolas Island. Proceedings of the Fifth California Islands Symposium. 546-554.

- La Casa Sirena (undated). Catalina Island Vacation Rentals - La Casa Sirena. http:// www.catalinavacations.com/bre/properties/Bahia-Vista--A05/.

- Mermaid Shelly. 2011. Catalina Island. A Mermaid’s Journey. http://mermaidshelly.blogspot.com.au/2011/02/catalina-island.html.

- Moore, P.A., 2002. The Casino. Avalon: Catalina Island Museum Society.

- Russian Laboratory of Theoretical Folkloristics, 2104. Conference on Mechanisms of Cultural Memory: From Folk-Lore to Media-Lore. RANEPA website: http://www.ranepa.ru/eng/activities/item/604-cultural-memory.html.

- Shima, n.d. Aquapelago Anthology. https://www.shimajournal.org/anthologies.php#aquapelago.

- Suwa, J, 2012. Shima and Aquapelagic Assemblages. Shima 6 (1). 12-18.

- Suwa, J, 2018. Ningyo Legends, Enshrined Islands and the Animation of an Aquapelagic Assemblage around Biwako. Shima 12 (2). 67-81.