The Impacts of Tourism Development on Community Well-being in Langkawi: The Case of Kampung Padang Puteh, Mukim Kedawang

Department of Forestry Science, Faculty of Agriculture and Food Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia mohamadsyahrulnizamibrahim@gmail.com

Institute for Environment and Development, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia sharinahalim@ukm.edu.my

Department of Environmental Management, Faculty of Environmental Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia m_yusoff@upm.edu.my

Abstract

Tourism has assisted the development of environmental, economic, social and cultural aspects of island communities. While there are some previous studies on the impacts of tourism development across Langkawi, it is necessary to consider the impacts of tourism development on individual island communities. Kampung Padang Puteh, Mukim Kedawang, Langkawi is located on the route between the island’s main tourism attraction areas, Pantai Cenang and Pantai Tengah (which are highly affected by tourism activities). This purpose of this study is to examine the impacts of tourism development with regard to benefits and challenges based on the local community perspective. A combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches was used in this study through a questionnaire to 49 household representatives, and individual interviews that were conducted with 16 selected key informants in Kampung Padang Puteh. Analysis of mean, Spearman’s rho correlation and qualitative approaches were used to interpret the data. The main findings concern community well-being and the benefits and challenges of tourism development impacts for the local community. It was found that the local community have improved their socioeconomic level through employment opportunities, additional income and language skills. While social ties were still good, negative aspects pose challenges. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the extent of community well-being in the midst of tourism development, which is the key element in achieving a sustainable society, particularly for island communities.

Keywords

Tourism development, impacts, community well-being, sustainable, Langkawi

Introduction

Community well-being is a combination of social, economic, environmental, cultural, and political conditions identified by individuals and their communities as crucial for them to flourish and fulfill their potential (Brasher and Wiseman, 2008). Cummins (1997) found that the satisfaction associated with community well-being domain occurs when people achieve satisfaction through education, neighbourhood, service, facilities, social life and social relations. Community satisfaction makes a significant and positive contribution to community members’ perceptions of their own quality of life (Norman et al., 1997). Many factors can directly or indirectly affect community well-being. Equally, one aspect of community well-being can impact on another (Lee and Kim, 2015). For instance, there is a well-established link between economic well-being and health (Burchell, 1998; WHO, 1998), and between community satisfaction and attachment to an area (St John et al., 1986).

Numerous studies have been conducted on the impacts of tourism development on local communities in Langkawi. However, there have been persistent problems at the community level even when actions had been undertaken by local stakeholders to overcome them. Island communities are unique, and pressure and changes threaten their stability. Islands face problems associated with their natural characteristics and their ecosystems are often fragile (Dahl, 1991). Islands have higher vulnerability in term of economic, social and environmental factors, climate change and trade, due to factors outside their control (Briguglio, 2003).

The exploitation of Langkawi’s tourism assets has changed this island into a well-known tourist destination, especially after it was declared a duty-free zone by the Malaysian government in 1987. Economic development in Langkawi was further increased following the establishment of the Langkawi Development Board (LADA) in 1990. LADA is responsible for planning and implementing development in Langkawi. However, both public and private agencies are actively involved in tourism related programs and activities to expedite tourism development on this island and consequently contribute to overall national development (Yussof and Omar 2007). Since the island is gifted with beautiful beaches, beach-related tourism has developed, particularly in Pantai Cenang and Pantai Tengah. Langkawi was also declared by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) as the first geopark in South East Asia in 2007. The recognition of this geopark at a global level has brought in more visitors, researchers and nature enthusiasts. In 2018, tourist arrivals were 3,628,951 with a rise of 28.9% from 2,815,178 in 2011 (Langkawi Development Authority, 2019). The growth in tourist arrivals has spurred a corresponding increase in demand within the tourism service industry. The government, private sectors and local communities have experienced a considerable amount of economic development as a result of the booming tourism industry in Langkawi.

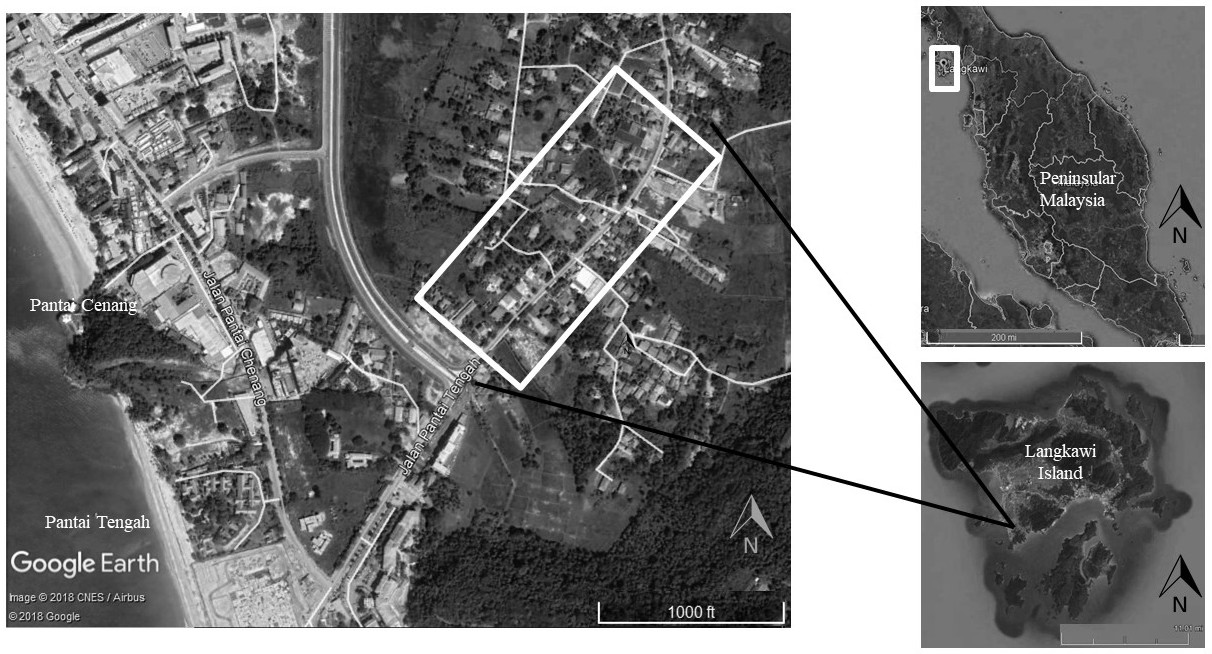

Kampung Padang Puteh, Mukim Kedawang, Langkawi is located on a route that connects the main tourism attraction areas, Pantai Tengah and Pantai Cenang, to the main entry points of Langkawi Island - Langkawi International Airport, Padang Matsirat and Langkawi Jetty Point, Kuah. The village has been affected by tourism development due to the fact that its location is exactly midway between Pantai Tengah and Pantai Cenang, resulting in an ever-expanding number of homestays, motels, hotels, restaurants and food stalls. This village can be recognized as tourism generating region in that it provides the residential base for tourists, is the place where tours begin and end and, in particular, since it allows access to those features of the region which incidentally cause or stimulate temporary outflow (Leiper, 1989).

It can be contended that community well-being in Langkawi has been improved due to the tourism industry (Norizan et al., 2013). The present study examines the impacts of tourism development on community well-being by examining the benefits and challenges involved. The evaluation and analysis of the positive and negative tourism development impact on local communities is based primarily on the perspective of local communities in Langkawi.

Tourism and well-being

Tourism studies have addressed well-being through a wide range of terms partly provided by philosophy and psychology, such as life satisfaction and quality of life (Sirgy et al., 2011; Dolnicar et al., 2012), happiness (Nawijn et al., 2010; Filep and Deery, 2010) and wellness (Bushell and Sheldon, 2009; Kelly, 2012; Voigt and Pforr, 2013). In these studies concepts such as “quality of life, welfare, well-living, living standards, utility, life satisfaction, prosperity, needs fulfillment, development, empowerment, capability expansion, human development, poverty, human poverty, land and, more recently, happiness are often used interchangeably, with well-being without explicit discussion as to their distinctiveness” (McGillivray and Clarke, 2006: 3). Well-being is viewed as the state of people’s life situations (McGillivray, 2007) and some researchers have examined community well-being by using individual attributes such as satisfaction, happiness, quality of life, individual efficacy/agency, and/or social support (Jurowski and Brown, 2001; Andereck et al., 2007; Kersetter and Bricker, 2012). Well-being measurements have progressed to encompass broader dimensions such as social and environmental aspects, and human rights (Sumner, 2006). It is now widely accepted that the concept of well-being is multidimensional: encompassing all aspects of human life (McGillivray, 2007). Theories of sustainability increasingly attempt to embrace notions of utilitarianism in well-being, requiring the development of destinations which create the greatest number of benefits for the greatest number of people within the limits of available resources (Kay Smith and Diekmann, 2017). Christakopolou and Dawson state that “the welfare of a community as a whole requires that these different parts function well and there is a balance between them” (2001: 323).

Tourism can assist in improving quality of life of local community and physical development (Marzuki, 2008). In this regard, the well-being of local communities in Langkawi and Redang Island has been improved by the increase of number of jobs in the tourism industry (Norizan et al., 2013). According to Nurlida Hanim Mohd Salleh et al. (2014), tourism increases the provision of appropriate employment opportunities, encourages tourists to come and spend their money in Langkawi, increases community’s pride in their own culture, provides employment opportunity for the local residents and attracts investors to Langkawi. However, tourism has also caused higher living, property and land costs (Marzuki, 2008). In social aspects, tourism has facilitated the availability of alcohol and has tended to promote drinking among young people as a normal activity, resulting in the lifestyle of local communities changing in line with tourist behaviours (Safura Ismail, 2015).

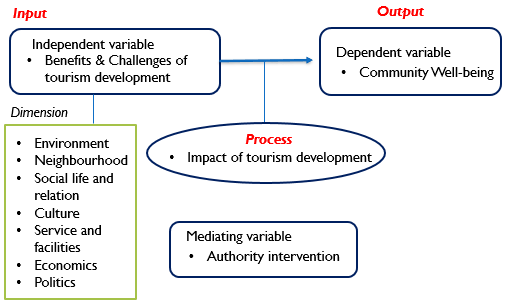

1. Conceptual framework

Based on Figure 1, this study aims to examine the direct and indirect impacts of tourism development on community well-being, with the focus on the benefits and challenges of tourism development that cover the dimension of environment, neighbourhood, social life and relations, culture, services and facilities, economics and politics. Authority intervention is a mediating variable that can affect the process indirectly. In order to achieve the objectives of the study, a thorough review of the existing relevant literature was performed and subsequently, a conceptual framework was developed. The conceptual framework addresses the key objective of this research, which includes all relevant aspects that shape and influence the community well-being. The model was adapted from Andrew and Withey (1976), Cummins (1996), Cummins (1997), Norman et al. (1997) and O’Brian and Lange (1986), which stress on aspects of community life and setting that make up people’s appreciation or dissatisfaction with the neighbourhood area where they live and it also emphasizes aspects of community well-being such as satisfaction with the environment, neighbourhood, social life and relations, services and facilities. This study also utilizes a community well-being concept defined by Brasher and Wiseman (2008) which is a combination of social, economic, environmental, cultural, and political conditions identified by individuals and their communities as essential for them to flourish and fulfill their potential.

2. Research methodology

2.1 Item development

A quantitative and qualitative questionnaire was devised and circulated in Bahasa Malaysia There are four sections in the questionnaire, each representing the benefits of current tourism development (BCTD), challenges of tourism development (CTD), community well-being (CWB) and respondents’ demographic background, together with open-ended questions. Items are adapted, in revised from, from previous studies, namely Andrew and Withey (1976), Brasher and Wiseman (2008), Cummins (1996), Cummins (1997), Norman et al. (1997) and O’Brian and Lange (1986). It is significant that the items closely correspond to the dimension of community well-being in order to make sure the questionnaire is relevant and in line with community well-being. There is a total of 12 items in BCTD that are constructed in a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 “Highly disagree” to 5 “Highly agree” (Igbaria et al. 1995; Fornell et al. 1996; McCool and Martin 1994) and 3 open-ended questions that only applicable to the respondents who recognise the benefits of tourism development for them. In the CTD section there are 15 constructed items, while 8 items in CWB section concern environment, neighbourhood, social life and relation, service and facilities, education, politics, economics and the cultural dimension. The total number of items were adjusted after subsequent validity and reliability tests were taken.

2.1.1 Item validity and reliability

Prior to the dissemination of the questionnaires to the sample population, the questionnaire was content-validated and tested for reliability. For item content validity, the questionnaire was given to experts in area of ethnic studies, community development, social psychology, sustainable livelihood of island and indigenous communities, education and tourism sustainability studies and social work from Institute for Environment and Development (LESTARI), Institute of Ethnic Studies (KITA), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia and the Faculty of Environmental Studies and Faculty of Human Ecology, Universiti Putra Malaysia. The process involved having a team of experts indicate the relevancy of items in a questionnaire (Polit and Beck, 2004). Consequently, the questionnaire was given to a total of 7 experts for them to review the items. A ‘validation format’ of the questionnaire was drafted where a section for the experts’ review was added. The section included a 4-point scale - not relevant, somewhat relevant, relevant and very relevant. An additional column was also added for their comments. 5 out of 7 experts returned the survey, which was sufficient to fulfill the minimum number of experts as recommended by Lynn (1986). The latter approach was used where comments given by the expert were taken into account and the questionnaire items were revised consequently. The different experts have different opinions; hence it is important to tabulate the comments according different questions for kind of consideration. A pilot test was undertaken in coastal villages of Mersing, Johor, namely Kampung Tanjung Resang and Kampung Air Papan. The internal reliability and consistency of questions were tested using Cronbach’s alpha.

Table 1 summarizes the alpha values obtained for BCTD, CTD and CWB items. Cronbach’s alpha values for the three sections have excellent for BCTD, good CTD and questionable for CWB internal consistency (George and Mallery, 2003).

| No. of items | Alpha value | |

|---|---|---|

| Benefits of current tourism development | 12 | 0.919 |

| Challenges of tourism development | 15 | 0.864 |

| Community well-being | 8 | 0.656 |

The Cronbach’s alpha reliability test is a crucial test that assumes each variable is considered as an equivalent test and all correlations between items that are measured are the same in each construct. Table 2 shows that removing item 7 for Community well-being section resulted in an increase in Cronbach’s alpha from 0.656 to 0.720, the highest value rather than removing other items. The highest Cronbach’s alpha value indicates that overall CWB is the most reliable. Thus, item 7 was deleted in pre-tested questionnaire in order to increase the Cronbach’s alpha value.

| Item total statistics | Alpha if item deleted |

|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.611 |

| Item 2 | 0.608 |

| Item 3 | 0.608 |

| Item 4 | 0.604 |

| Item 5 | 0.672 |

| Item 6 | 0.587 |

| Item 7 | 0.720 |

| Item 8 | 0.558 |

2.2 Research area

Kampung Padang Puteh was selected due to its proximity to the international tourism destinations Pantai Tengah and Pantai Cenang, Pantai Tengah being located 1.7 km away and Pantai Cenang 3.5km away. The area has become the main focus for foreign tourist visitation due to the lower price of accommodation and the proximity to beaches compared to other villages such as Kampung Lubok Buaya, Kampung Bohor Tempoyak and Kampung Temoyong. Kampung Padang Puteh, (6°17'25.8"N 99°44'10.4"E) is located in Mukim Kedawang, which is the fifth largest of sub-districts of Langkawi with an area of 50.97 sq. km and is located in the southwest of Langkawi Island. Kampung Padang Puteh comprises three networked villages - Kampung Tasek Anak, Kampung Teluk Baru and Kampung Tanjung Mali. The population of the village is 2,546 and the number of heads of households is 418. A total of 95% of the local community are Malay with the remaining 5% being from other races (such as Chinese, Indian, Thai and others). About 70% of the local community are private employees in the tourism industry, 15% are in business, 0.5% are contractors, 0.5% are engaged in agriculture and fishing and 0.5% are government servants. Most villagers are involved in tourism directly as service operators for hotels, chalets, guest houses, restaurants, cyber cafes, spas, recreation and sea sports centers.

Top-right: Location of Kampung Padang Puteh (Source: Google Inc., 2018).

2.3 Research technique

This study employed a mixed methods approach that combined quantitative and qualitative (face to face interview) approaches. The mixed questionnaire, which included closed-ended and open-ended questions, was distributed to a total of 49 household representatives by stratified sampling technique, while a key informant interview was conducted with village headmen, members of the Village Development and Security Committee (JKKK) and senior villagers, numbering 16 individuals, through non-probability purposive sampling. Mixed method research may be viewed as providing a more complete and deeper understanding of the subject under investigation and having greater scope than either one method (Greene, 2007; Johnson et al., 2007). The quantitative strand can provide statistical power and generalizability while the qualitative element provides meaning, context and depth (Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009). Mixed methods that combine qualitative and quantitative data provide a convenient method of everyday problem solving (Morgan, 2007; Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2010). The number of key informants for nested qualitative sampling is at least 12 participants, which allows detection of moderate effect sizes with 0.80 statistical power at the 5% level of significance (Guest et al., 2006). The voices of key informants often help to attain data saturation, theoretical saturation, and/ or informational redundancy (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2007). For a quantitative approach, about 10% of the 481 families were selected to answer the questionnaire (equivalent to n=49). The criteria for selecting respondents was that they must be above 18 years old or lived at least 10 years old at Kampung Padang Puteh (since they were required to have first knowledge on current situation regard the tourism development at their village). A small sample size that is selected properly is more acceptable than a large sample size that is selected relatively randomly (Neill, 2003). In order to achieve an effective sample, the total number of families or head of household in the village was needed and data was obtained with the assistance of the village headman. As an additional technique, observation was used to support the findings. However, it was still difficult to get the number of respondents as targeted due to time setting where the data collection was taken on weekdays and the villagers were not available.

2.4 Data analysis

The results of the questionnaire were entered into and analyzed by using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 24). Data analyses were performed using descriptive statistics, Spearman’s rho correlation and qualitative analysis. Mean analysis was conducted to measure the strength of the impact of each item relating to the development of tourism industry based on community perceptions. The higher the mean value, the higher the benefits of current tourism development towards the local community in Kampung Padang Puteh and vice versa. Mean analysis performed in this study has also been considered as a measurement tool in previous tourism literature (Andereck et al. 2005; Sirakaya et al. 2001; Jurowski et al. 1997; Pearce 1991). Spearman’s rho was used to measure the strength of association between items of BCTD and CTD for each theme. Qualitative analysis was used to elucidate the significant variables in this study.

3. Results and discussions

3.1 Demographic characteristics

From a total of 49 respondents in the study, 34.7% (n = 17) of them are male and 65.3% (n = 32) are female. The number of female respondents is higher because most of them are available at home on working days, unlike male respondents. Their age ranges from 19 to 69 years old, with a classification of generation based on the development of Malaysian social history (Din, 2005); where 12.2% (n = 6) of them are 19 to 27 years old; 51.0% (n = 25) are 28 to 48 years old and 36.7% (n = 18) are 49 to 69 years old. Most of respondents originated from Kampung Padang Puteh (75.5%) and the rest are from outside (24.5%), however both clusters are currently living in the local community. About 71.4% of respondents are involved directly in tourism sector, while about 28.8% are not involved in income generated from the tourism sector. Most of respondents are self-employed (n=18), while the rest are working in private sectors (n=10); housewives (n=8); others (n=7); government servant (n=4) and retirees (n=2). The demographic backgrounds of respondents are shown in Table 3.

| Demographic background | Frequency, N |

Percentage, % |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 17 | 34.7 |

| Female | 32 | 65.3 | |

| Home ownership status | Own | 41 | 83.7 |

| Rent | 8 | 16.3 | |

| Marital status | Single | 7 | 14.3 |

| Married | 39 | 79.6 | |

| Divorced/widowed | 3 | 6.1 | |

| Age | 19-27 | 6 | 12.2 |

| 28-48 | 25 | 51.0 | |

| 49-69 | 18 | 36.7 | |

| Period of stay in village | Less than 15 years | 3 | 6.1 |

| 15-25 years | 6 | 12.2 | |

| 26-40 years | 16 | 32.7 | |

| 41-69 years | 24 | 49.0 | |

| Monthly income | Below RM1000 | 15 | 30.6 |

| RM1000-RM2000 | 23 | 46.9 | |

| RM2001-4000 | 9 | 18.4 | |

| Above RM4000 | 2 | 4.1 | |

| Level of education | No formal education | 1 | 2.0 |

| Primary education | 10 | 20.4 | |

| Secondary education | 29 | 59.2 | |

| Tertiary education | 9 | 18.4 | |

| Number in household | Children | ||

| No children | 17 | 34.7 | |

| 1-3 persons | 25 | 51.0 | |

| 4-5 persons | 7 | 14.3 | |

| Adult | |||

| 1-2 persons | 23 | 46.9 | |

| 3-5 persons | 22 | 45.0 | |

| 6-8 persons | 4 | 8.1 | |

Table 4 shows the list of selected key informants of Kampung Padang Puteh interviewed in different individual sessions where most of them are senior villagers and have first knowledge on the village.

| Key informant (K) | Gender | Status | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | Male | JKKK member | Managing director of company |

| K2 | Female | Senior villager | Restaurant operator |

| K3 | Female | Senior villager | Housewife |

| K4 | Female | Senior villager | Housewife |

| K5 | Female | Senior villager | Housewife and landlady |

| K6 | Female | Senior villager | Housewife |

| K7 | Female | Senior villager | Housewife and landlady |

| K8 | Male | Senior villager | Fisherman |

| K9 | Male | Senior villager | Fisherman |

| K10 | Female | JKKK member | Government retiree |

| K11 | Male | Senior villager | Gardener |

| K12 | Male | Senior villager and community football coach | Government officer |

| K13 | Female | Senior villager | Hotel housekeeper |

| K14 | Female | Senior villager | Restaurant operator |

| K15 | Female | Senior villager | Housewife |

| K16 | Female | Senior villager and mosque active member | Government retiree |

3.2 Benefits of current tourism development

Table 5 shows the mean and standard deviation of items used for BCTD. Five items from the total 9 items examined scored the highest mean. These items measure community perception on positive tourism impacts through its benefits towards them which are: creating employment opportunities that are capable of generating growth, diversity and economic stability in the village (4.45); providing additional income to the services sector (such as accommodation and transportation) in the village (4.27); improving foreign language skills (such as English, Thai and others) for villagers (4.16); giving the village strategic advantage as located between Pantai Cenang and Pantai Tengah (4.16); and improving the quality of life of the villagers (4.08).

| Items | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Tourism development has created employment opportunities that are capable of generating the growth, diversity and economic stability of the village. | 4.45 | 0.542 |

| 2. | Tourism development has provided additional income to the services sector (such as accommodation, transportation) in the village. | 4.27 | 0.758 |

| 3. | Tourism can improve foreign language skills to villagers. | 4.16 | 0.717 |

| 4. | This village has a positive impact due to its strategic location, located between Pantai Cenang and Pantai Tengah on is the main tourist route. | 4.16 | 0.688 |

| 5. | Tourism has improved the quality of life of the villagers. | 4.08 | 0.786 |

| 6. | Tourist outflow in the village brings more benefits. | 4.02 | 0.661 |

| 7. | Tourism development has provided an opportunity to realize the economic value of a particular production, based on the quality of food products, as well as buildings that are not used and abandoned in the village. | 4.00 | 0.816 |

| 8. | Tourism development has enhanced community relations, especially in bringing closer groups of people living apart from each other. | 3.69 | 0.822 |

| 9. | Tourism development has provided an opportunity to re-evaluate the elements of the village's heritage and environment. | 3.53 | 0.767 |

Tourism development has created employment opportunities that are capable of generating the growth, diversity and economic stability of the village. Mohd Shariff and Tahir (2003) identified clusters of tourists around several restaurants in Langkawi Island, which boosted income and job opportunities for local residents. This shows that tourism and development bring changes to local socio-economic status as well as improving local well-being. Based on a study conducted by Norizan et al. (2013), employment enhances community well-being on Langkawi especially in terms of employment, income and expenses. Community members acknowledge that their well-being has changed after getting job opportunities on the islands. In other words, the tourism industry has stimulated economic growth by providing employment opportunities (Irwana Omar et al., 2014).

Tourism development has provided additional income to the services sector (such as accommodation and transportation) in the village. The local community is likely to view tourism as a tool that reduces unemployment by generating additional business for locals (Gursoy and Rutherford, 2004). The development of an accommodation center has provided opportunities for most of the locals to work in the tourism and service sector (Muhammad Najit Sukemi et al., 2008). Service sectors such as accommodation and food operators are seasonal in term of generation of income. According to Cannas (2012), public holidays represent one of the most common factors that affect tourism. Such holidays may be based on one of, or a combination of, religious, cultural, social and political factors. Although public holidays were mostly single days, more recently they have aggregated with weekends and breaks of longer duration, so that they have an increased influence on the tourism business. With regard to institutionalized causes of seasonality, school and industrial holidays play a more important role than public holidays on shaping tourism. However, providing a monthly room or house rental service is more lucrative than the homestay or chalet business because the operators can get secure monthly income. Most tenants are outsiders who come to work in Pantai Cenang and Pantai Tengah or the nearby area of Langkawi. From the aspect of spending, all respondents spent enough for their families and themselves. Increasing jobs in the tourism industry on Langkawi have enhance the level of spending and ownership, thus enhance the well-being of the community (Norizan et al., 2013).

Tourism has improved the foreign language skills of villagers with basic English language skills being boosted through informal conversations with foreign tourists (since English is the main medium for travelers to communicate with locals). More broadly, residents of Langkawi Island having gained positive experience while interacting with foreign tourists (Marzuki, 2011). Therefore, one of the positive social impacts perceived by Langkawi community is the development of foreign language (Safura Ismail, 2005).

Kampung Padang Puteh can be identify as a tourist generation region and the existence and significance of “push” factors in tourist generation regions have been recognized in causal studies. The generation region is the main location of the tourist industry and the source of potential tourism demand. Accordingly, the major marketing functions of the tourist industry are conducted there: promotion, advertising, wholesaling, and retailing. Underlying the marketing function is the question of why certain regions exhibit a tourist exodus, an issue with commercial and sociological relevance. Apart from that, the villagers find it easy to market small businesses such as street food operations to tourists and residents. Villagers also can market other service products due to its strategic location. Moreover, the village has a number of cheap guest houses where visitors can get low priced accommodation (at around RM20 per night) and this encourages them to stay longer. Transit routes are a vital element in the system since their efficiency and characteristics influence the quality of access to particular destinations and accordingly, they influence the size and direction of tourist flows. Transit routes are the location of the main transport component of the tourist industry (Leiper, 1979). In contrast, a different situation occurs in Kuala Perlis, a transit area for those who want to go to Langkawi Island. Visitors do not spend the night in this area because they only used ferry services to Langkawi. This is especially detrimental to the hotel industry around Kuala Perlis because it has to compete with Langkawi Island (Goh et al., 2014). Basically, challenges or pressures of tourism on the economy in the transit area are significant. However, Kampung Padang Puteh’s operation as a transit area has been a good marketing factor for the villagers, thus enhancing their level of well-being with considerable monthly income which improves their well-being.

Overall, tourism development has enhanced the quality of life of villagers directly and indirectly through improvement of the conditions of the community environment and services and facilities in Kampung Padang Puteh. It seems the local community’s involvement in the tourism industry has increased household income compared to previous traditional employment. Quality of life has been defined "as the satisfaction of an individual's values, goals and needs through the actualization of their abilities or lifestyle" (Emerson, 1985: 282). This definition is consistent with the conceptualization that satisfaction and well-being stems from the degree of fit between an individual's perception of their objective situation and their needs or aspirations (Andrews and Withey, 1976; French et al., 1974). Tourism development in Langkawi Island has contributed to the improvement on the quality of life and overall life condition of its residents (Marzuki, 2011).

Table 6 shows a total number of respondents who perceived BCTD towards them. A total of 45 out of 49 respondents agreed that the tourism development in the village gave benefits to them. From these total number of 45 respondents, about 44.9% of them stated that they received benefit from tourism before the recognition of Langkawi UNESCO Global Geopark (LUGG), indicating that LUGG status was not a vital factor. According to Hamzah and Mohamed (2015), residents in Langkawi Island felt that tourism industry is crucial to their community because the island had obtained its Duty Free Port status in 1 January 1987 and from then on, opportunities for the commercial, business, and service sector has been given to local residents. Duty Free Port status is more familiar to the local community than geopark status.

Similarly, Kuala Teriang villagers also believed that the geopark status did not change the number of tourist arrivals visiting Langkawi as most of tourists come to the island for the shopping and/or its natural attractions rather than Geopark status (Ong et al., 2010). However, this may arise because of their lack of knowledge of geoparks. In fact, the status of geopark has increased their socio-economic levels indirectly and directly. The Geopark also provides space for economic and community development to improve the well-being of local communities and the conservation of natural and socio-cultural heritage (Ibrahim Komoo, 2010).

| Frequency, N |

Percentage, % |

|

|---|---|---|

| Did you get benefit from the tourism development in this village? | ||

| Yes | 45 | 91.80 |

| No | 4 | 8.20 |

| When did you start to get benefit from the tourism development? | ||

| Since the recognition of Langkawi as a geopark. | 20 | 40.80 |

| Before the recognition of Langkawi as geopark | 22 | 44.90 |

| Others (e.g.: after the declaration of Langkawi as Duty Free Island) | 3 | 6.10 |

According to the total of 45 respondents who agree on the benefits of tourism development towards local community, most of them (n=20) believed that tourists were the most beneficial to them compared to others, followed by local entrepreneurs (n = 17); federal government agencies (n = 4); Kedah state government (n = 3); others (e.g. local community) (n = 1); and both local authorities and non-local entrepreneurs (n = 0).

3.2.1 Local community perspectives on the benefit of current tourism development

Tourism development has increased employment opportunities for the local community with numerous accommodation services operating in Langkawi.

In the past… some villagers do not have job, but now, it is not a problem due to many employment opportunities nowadays. (K2)

One of the key informants, K13, who works as a housekeeper, said that previously she and late husband worked as fishers and after her husband passed away, she was offered to work as a housekeeper at her sister's hotel.

It was hard to get money before this. Now, Alhamdulillah (praise to God), with the existence of tourism, there are many job opportunities available now, thankfully - compared to the previous life as a fisher whose income was uncertain and we used to not eat someday because there was no money at all. (K13)

Tourism development has provided additional income to the service sector in the village. Some of accommodation operators said that the income generated from accommodation services (e.g. chalet or homestay) is additional for them because they are already having a principal income to support their family, some of them being public servants or working in private sectors. K5 and K7, who are chalet operators, said;

Some foreign tourists prefer to stay in the chalet in a long period of time which is up over six months, and this indirectly increases existing monthly income.

K2 and K14, who are restaurant operators, said that the presence of foreign tourists is a big advantage for them as service operators especially during international events and school holidays where their service will be used by them.

The local community also have improved their language skills, not only English but also another foreign language such as Japanese. K11 said:

I have spoken English slowly due to having to explain any information in English to foreign tourists who come to stay at my guest house or chalet.

I know how to speak Japanese a little bit because I learn it from my Japanese colleague and tourists during work at the hotel. I taught him (colleague) Bahasa Melayu and he also taught me Japanese language, but only basic communication. (K13)

K1 who is a village headman, said that a basic English class was opened by the Community Development Department (KEMAS) and LADA for the villagers in order to improve their language skills.

The strategic location of the village, which is near to beaches, inclines foreign tourists to stay at guest houses in Kampung Padang Puteh since some of them prefer to walking to the beach area from their accommodation.

Foreign tourists like to stay at the guest house in this village and they are from United States, Australia, Germany, France, Russia and etc. They like to bask at Pantai Cenang and Pantai Tengah. (K16)

There are some foreign tourists who stay for a month at the village for the reason of more privacy and quiet rather than another area. (K8, K9, K13)

Tourism has improved the quality of life of the villagers. Most of key informants said that the situation of the village is much better than before the tourism development occur in Langkawi.

3.3 Challenges of tourism development

Table 7 shows the mean and standard deviation of items used for CTD. Five variables from the total 12 items examined scored the highest mean. These items measure community perception on negative tourism impacts through its challenges towards them: the negative impact of tourists on the younger generation (4.14); the capital required to develop the local tourism sector (which is large and beyond the affordability of local entrepreneurs) (3.71); traffic congestion and noise (3.61); issues with individuals who work with tourism usually not having specialized skills in business and marketing (3.31); and tourism leading to internal investment in business enterprise and job creation where the returns are low (3.20). Meanwhile, the five items recording the lowest mean scores are involve: the population being more likely to move out of this village to other places due to the current impact of tourism development (2.02); tourism causing neighbourliness to be diminished (2.53); local communities finding it difficult to reach the level of product quality and good service as expected by tourists (2.61); villagers feeling uncomfortable living in a village which is a tourism destination (2.61); and local communities and businesses finding it difficult to adapt to the changing environment (2.63).

| Items | Mean | Standard deviation |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Negative cultural effects caused by tourists (such as skimpy dressing and drinking liquor) will affect the younger generation. | 4.14 | 0.913 |

| 2. | The capital required to develop the local tourism sector is large and beyond the affordability of local entrepreneurs. | 3.71 | 0.764 |

| 3. | Tourism development in Langkawi has caused traffic congestion and noise. | 3.61 | 1.017 |

| 4. | Individuals who work with tourism in this village usually do not have specialized skills in business as an effective marketing. | 3.31 | 0.871 |

| 5. | Tourism in this village led to internal investment where there is a business enterprise and job creation but the returns are low. | 3.20 | 1.000 |

| 6. | Local communities find it difficult to sell their products as the village is a tourist transit area. | 2.80 | 0.866 |

| 7. | Tourist traffic in the village brings many problems. | 2.80 | 1.154 |

| 8. | Local communities and businesses find it difficult to adapt to the changing environment. | 2.63 | 0.906 |

| 9. | Villagers feel disturbed by living in a village which is a destination for tourism. | 2.61 | 0.996 |

| 10. | Local communities find it difficult to reach the level of product quality and good service expected by tourists. | 2.61 | 0.812 |

| 11. | Tourism cause neighbourliness to be diminished. | 2.53 | 1.226 |

| 12. | The population is more likely to migrate to other places due to the current impact of tourism development. | 2.02 | 0.878 |

There is a fear that the cultural impact of tourists such as skimpy dressing and drinking liquor will affect the younger generation in the village. The price of alcoholic drinks in Langkawi is cheaper than other places in Malaysia as it is not subject to any tax (Marzuki, 2011). Young people can easily buy alcohol at Pantai Cenang because there are numerous shops where it is available. Overall, the scenario is in line with the findings by Safura Ismail (2015), which studied the social impacts of tourism development on local community in Mukim Kedawang, Langkawi, which showed tourism promoted drinking among teens as a normal activity and caused changes in fashion attire, with locals imitating tourist clothing, and behaviour. This contrasts to Perhentian Island, where the community are not notably influenced by alcohol consumption because the sale of alcoholic products is prohibited, thus limiting the consumption among tourists (Moghavvemi et al., 2016). In response to such issues, patrols were conducted by JKKK members on Saturday nights to deter alcohol and drug consumption and promiscuity in Pantai Cenang and Pantai Tengah. According to the National Anti-Drug Agency (2018), Langkawi is one of the 178 national high-risk areas for drug abuse in Malaysia. While social ills in Langkawi are still at a preventable stage, they might threaten community well-being in the long term.

It is significant that the capital required to develop the local tourism sector is large and beyond the affordability of local entrepreneurs. Developing and organizing rural tourism may require a significant investment either beyond the means of the business owner or greater than justified by potential returns (Lachov et al., 2006). External support to business operators also needs to be considered, encompassing aspects of financial assistance from the government and banks, and the support to obtain start-up capital, raw materials and labor (Norlida Hanim Mohd Salleh et al., 2014). Local community representatives stated that the financial assistance from the government and banks is an important input to boost their businesses. The study conducted by Gunawan (2014) showed that financial factors are important to businesses and financial assistance from commercial banks is also needed to expand or grow business.

Tourism development in Langkawi has caused traffic congestion and noise, particularly from tourists’ motorcycles, that disturbs some villagers and affects their happiness and well-being. This issue is also often debated by residents of Langkawi through local radio station, Langkawi FM. The problem is exacerbated by the village having relatively narrow roads and the high number of visitors causes traffic congestion at particular times. This is supported by Marzuki (2011), who identifies that residents face serious traffic congestion due to the presence of tourists. Several other studies also found that residents perceived that traffic was a major problem created by tourism activities (Long et al., 1990; Keogh, 1989; Prentice, 1993). Tourists have the option of renting cars or motorcycle at Langkawi Island airport, which makes it easy for them to travel about the island (Moghavvemi et al., 2016). Compared to other locations, such as Perhentian Island and Mabul Island, Langkawi Island has high traffic due to its accessibility to vehicle rental services at main points. Additionally, Islam et al. (2014) identified that tourists normally get to Perhentian Island by a speedboat from the mainland port of Kuala Besut and do not utilize cars to move around in that island. As for Mabul Island, tourists are required to get on a boat ride from Semporna to the accommodation area, reducing traffic pressures.

Most individuals working with tourism in the village usually do not have specialized skills in business and marketing, ranked as the fourth highest mean score for CTD variable. Individual rural tourism enterprises normally possess neither the skills nor the resources for effective marketing, a prerequisite for success (Sharpley and Sharpley, 2002). “Training is the process that provides employees with the knowledge and the skills required to operate within the systems and standards set by management” (Sommerville, 2007: 208). Training with specialized skills in business, especially in hospitality, can aid in increasing productivity in the business (Xiao, 2010). Training should be thorough and in-depth and lack of training or poor training brings out high delivery of substandard products and services (Sommerville, 2007).

Tourism in the village has led to business enterprise and job creation where the returns are low. One of the factors may hamper the achievement of rural economic diversification and growth through tourism is inward investment, owing to the small scale and highly seasonal market. During international events and school holidays, the demand for accommodation services is high. Therefore, the price is inflated at these times. The higher prices charged are able to bring multiple benefits for accommodation operators. The large profits are able to cover the cost of maintenance of existing accommodation for several months. Seasonality is “a temporal imbalance in the phenomenon of tourism, which may be expressed in terms of dimensions of such elements as numbers of visitors, expenditure of visitors, traffic on highways and other forms of transportation, employment, and admissions to attractions” (Butler, 1994: 5). Hylleberg (1992) classified the basic causes of seasonality into three different categories - weather (e.g. temperatures); calendar effects (e.g. timing of religious festivals such as Christmas); and timing decisions (e.g. school vacations, industry vacations).

The capital required to develop the local tourism sector is large and beyond the affordability of local entrepreneurs. However, K15 said that the villagers usually get capital from Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM) and TEKUN Nasional loan to start a business such as homestays and guest houses. There are some fortunate villagers who have received compensation for land acquired by the government, especially those who owned land at Pantai Cenang area. Some villagers used the compensation as capital to start a business, especially for a guest house or rental house building. K5 said;

I got compensation from the government with my land which is located at Pantai Cenang area and with that money I started to build rental houses and room [for the] public.

Meanwhile, the K16, a government pensioner did not get any loan or compensation, but instead used her and husband’s retirement income as capital for business. K16 said that there are villagers who pledge their land to get the capital from the bank. Unfortunately, they fail to repay the loan within the stipulated time and finally their land has been resumed by the bank and subsequently purchased by outsiders. While K1 has identified that LADA has offered courses for homestay business in the past, most key informants said that homestay or guest houses operators do not participate in any courses to improve business skills such as hospitality.

The influence of tourists’ cultural behaviour on the younger generation is worrying for villagers.

It is nothing wrong for foreign tourists to drink liquor and wear such that clothes, but why the young generation of this village want to imitate their improper style? (K13)

Young generation have poor self-esteem and easily influenced by negative surrounding. (K5)

There are few young people in this village [who] are Muslim Malay with tattoos. (K3, K12)

Some young people like to go to the bars and nightclub. (K13)

3.4 The relationship between the benefits and challenges of tourism development

The benefits and challenges of tourism development can be arranged into six themes: income generation opportunities; community relation; skills; quality of life; tourist traffic; and cultural and environmental change.

Overall, the BCTD and CTD have a negative relationship through Spearman’s Rank correlation coefficient value result (refer Table 8). In this regard, the answers by respondents do not contradict each other but suggest that the benefits of current tourism development have increased along with the decline of challenges perceived by respondents. However, only one theme, skills, has a weak positive relationship where the villagers’ foreign language skill is increased despite them not having specialized skills in business. Communication is one of the specialized skills required in effective business marketing. The result shows that foreign language skill can be enhanced even without participation in a formal course. Interaction with foreign tourists itself can improve locals’ skills, especially in communication and business. A study conducted by Norlida Hanim et al. (2014) showed that the involvement of local communities in tourism-related business is influenced by income and by encouragement from family. These factors are also assisted by self-confidence, interest and opportunity available. The community stated that being confident is an important stimulus for business and binge prepared to improve the situation when there is a complaint from a customer. Hasani et al., (2016) demonstrated that Malaysian residents can be quite welcoming of tourists not only for the economic benefits (i.e., increased employment opportunities and improved standards of living) but also opportunities for cross-cultural exchange, whereby residents are afforded numerous opportunities to interact with visitors and engage in transformative learning.

Based on Table 8, the quality of life theme shows a correlation significant value. This indicates that the villagers do not feel not disturbed in the village and do not want to migrate from it when the quality of life alters. This clearly shows the strong negative relationship between quality of life theme for both benefits and challenges of tourism development. However, the result of Spearman’s rho correlation is offset against the mean analysis where this item ranked as the least mean score. Most key informants would not think of migrating from their village since they are one of community there.

Comparing the benefits and challenges of the tourism development variable, the mean scores for BCTD have higher value than CTD, which indicates that the local community of Kampung Padang Puteh believed that the tourism brings more benefits than challenges. Siu et al. (2013) noted that when local residents have positive attitudes towards tourism as a whole, they are more inclined to look upon tourists favourably and subsequently support tourism development. This support is strengthened by experiencing personal benefits that improve standards of living. Community benefits have also been found to contribute to residential support for future tourism development (Sharma and Gursoy, 2015). The local community of Langkawi have been quite adaptable to changes, and those residents who were more adaptable to changes indicated that tourism brought more benefits than costs (Kayat, 2002).

| Item for CTD | Income generation opportunities | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism development has created employment opportunities that are capable of generating the growth, diversity and economic stability of the village. | Tourism development has provided additional income to the services sector in the village. | Tourism development has provided an opportunity to realize the economic value of a particular production, based on the quality of food products, as well as buildings that are not used and abandoned in the village. | |

| Income generation opportunities | |||

| Tourism in this village led to internal investment where there is a business enterprise and job creation but the returns are low. | 0.036 | -0.53 | 0.026 |

| The capital required to develop the local tourism sector is large and beyond the affordability of local entrepreneurs. | -0.27 | -0.287* | -0.139 |

| Local communities and businesses find it difficult to adapt to the changing environment. | -0.381** | -0.136 | 0.274 |

| Local communities are difficult to reach the level of product quality and good service as expected by tourists. | -0.306* | -0.274 | -0.274 |

| Item for CTD | Community relation | Skills | Quality of life |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism development has enhanced community relations, especially in bringing closer groups of people living apart from each other. | Tourism can improve foreign language skills to villagers. | Tourism has improved the quality of life of the villagers. | |

| Community relation | |||

| Tourism causes neighbourliness to be diminished. | -0.211 | ||

| Skills | |||

| Individuals who work with tourism in this village usually do not have specialized skills in business as an effective marketing. | 0.066 | ||

| Quality of life | |||

| Villagers feel disturbed by living in this village which is a destination for tourism. | -0.283* | ||

| The population is more likely to move out of this village to other places due to the current impact of tourism development. | -0.368** | ||

| Item for CTD | Tourist traffic | Cultural and environmental changes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| This village has a positive impact due to its strategic location that located between Pantai Cenang and Pantai Tengah which is the main tourist route. | Tourist outflow in the village brings more benefits. | Tourism development has provided an opportunity to re-evaluate the elements of the village's heritage and environment. | |

| Tourist traffic | |||

| Tourist traffic in the village brings many problems as compared to benefits. | -0.175 | -0.063 | |

| Cultural and environmental changes | |||

| The negative cultures by tourists (such as eye-catching dressing style, drinking liquor) will affect the younger generation. | -0.219 | ||

| The tourism development in Langkawi has caused traffic congestion and noise. | -0.570 | ||

* Correlation is significant at α = 0.05.

3.5 The community well-being of Kampung Padang Puteh

Table 9 shows the analysis of CWB indicators that were elucidated through mean score on satisfaction on neighbourhood (4.14); life and social relation (4.08); education (3.98); services and facilities (3.71); culture (3.69); environment (3.59); and politics (3.04).

| Items | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Neighbourhood Are you satisfied with the people who live in this community? |

4.14 | 0.866 |

| 2. | Life and social relation Are you satisfied with the life of your community? |

4.08 | 0.812 |

| 3. | Education Are you satisfied with the education provided to the children in your area? |

3.98 | 0.829 |

| 4. | Services and facilities Are you satisfied with the services and facilities you get in this community? |

3.71 | 0.890 |

| 5. | Culture Are you satisfied with the culture of the community in your village? |

3.69 | 0.822 |

| 6. | Environment Are you satisfied with the environment in your community (air, water, land)? |

3.59 | 1.039 |

| 7. | Politics Are you satisfied with the political representation in your area? |

3.04 | 1.079 |

According to Table 9, the neighbourhood indicator shows the highest mean score, which corresponded with Table 7 where the neighbourhood possesses the second least mean score. This indicates that respondents are very satisfied with the neighbourhood aspect of this village. Most key informants - K2, K4, K5, K6, K7, K8, K9, K10, K11, K14, K15 - stated that the neighbourliness is the same as before and has not changed.

The villagers also have high satisfaction with life and social relations in Kampung Padang Puteh – unlike the situation in Mabul Island, where the local community felt that tourism has the capability to bring some negative effects such as affecting social relationships within it (Moghavvemi et al., 2016). This suggests that life and social relation in Langkawi, particularly Kampung Padang Puteh, is better than Mabul Island. One of the characteristics of island communities is togetherness and the commitment to protecting traditional values on Langkawi is manifest, for instance the commitment to semangat gotong royong – the joint bearing of burdens resulting from social events like weddings, safety matters, funerals and religious occasions (Halim et al., 2011).

According to K1, villagers cooperate to clean the mosque after Solat Jumaat (Friday prayer) which is conducted weekly.

The village community still chooses to work together for preparations for wedding feasts compared to catering services. (K1, K2, K3)

I like to attend the wedding feast. I just came back from the wedding ceremony of one of the neighbours here. (K4)

I am joining the religious class in the mosque and often travel with my ustazah (religious teacher) and classmates. (K7)

I am the head of the Women’s Neighbours’ Association here. We are organizing programs such as sewing and traditional foods classes and majlis tahlil (holy recital program) with the community and the response from the residents is very encouraging. (K10)

Respondents have good satisfaction levels with education provided in the local school. K1, who is also a former head of Parents and Teachers Association (PIBG) of the nearby primary school, stated that financial assistance was given to poor students through the Poor Student Trust Fund (KWAM) and Supplemental Food Plan (RMT). K11 said that a free tuition scheme is provided to the low-income primary school students by the Sultanah Bahiyah Foundation. All young people in the village have fair educational opportunities and poor children receive assistance from the school, which gives them better potential to achieve excellence in education. Quality education is the foundation of good well-being because it is a pointer to life aspects such as employment, income and social status (Economic & Social Research Council, 2014). Most respondents indicate good satisfaction on education at school, however, there are still have some students who did not appreciate the opportunity given to them and they are involved in school truancy and dropout due to factors such as family issues.

The Services and facilities indicator ranked as the fourth highest mean score for CWB. There is a significant positive change in the village in terms of facilities. Tourism development has led to the upgrading of existing roads, including the construction of a new highway. Langkawi’s overall utilities, including public infrastructure and facilities, have been enhanced, benefitting its residents and the tourists who visit (Moghavvemi et al., 2016; Safura Ismail, 2015).

I am happy to see the changes in this village as the road is getting better and now we have a traffic light there. (K14)

In the past, there was no proper paved road and shops, but now the things seem getting better. (K4)

Now, the number of streetlights is increasing and the street is brighter at night. (K12)

Langkawi Municipal Council is providing premises for local community to operate their business at Pantai Cenang. (K10)

Satisfaction with the culture of the village shows as the third least for mean score for CWB. It shows that the respondents are less satisfied with the culture that has changed in this village. Most of key informants said that the young generation today have poor self-esteem and easily affected by social ills. For example, some are involved with drugs, robbery and/or truancy. The local community in Langkawi tend to agree that there are tourists who utilize drugs and that tourism industry has inclined locals to involve themselves in drugs to a greater extent than Perhentian Island and Mabul Island (Moghavvemi et al., 2016). Intermarriage between villagers and foreigners (including tourists and workers) has also increased. According to K8, there are villagers who marry foreigners and after a period of time, are abandoned by their spouses.

I have to take care of my step-grandchildren because they were abandoned by their mother and never returned home. Unfortunately, my step-grandchildren do not want to go to school. (K4)

With regard to the environment aspect, respondents are less satisfied with it. Tourism development also has a direct effect on the environment of a given tourist destination area. The deterioration in the environment includes pollution and noise (Norlida Hanim Md Salleh et al., 2014). Whereas, pollution in the village is mainly due to the local community, the noise nuisance is caused by tourists who ride on motorcycles and talking loudly disturbing the local community. Based on observations, there are some clogged drains and filled with rubbish such as plastic bags, plastic bottles and other materials. Although there are large public garbage bins along the roadside and the waste is collected three times a day by Environment Idaman Sdn. Bhd there is also an illegal dumping area which located at the side of the road where some villagers dump their garbage. Recently, the area has been fenced off by yellow line and warning sign stating "Garbage Disposal Prohibition Area" erected by SWCorp Malaysia. This situation can affect the aesthetic view of village itself and it portray a bad image to the tourists. There is also open burning by some villagers during the day which is against the mission of Langkawi Low Carbon Island’s 2030 project.

The least satisfaction reported by respondents is politics indicator where it indicates only 3.04 for mean score of CWB. The difference of political ideology among the villagers might be a reason why this political indicator is at low value, especially since the 14th Malaysian General Election was getting closer during the data collection. In fact, government intervention is a mediating variable in this study since the JKKK is a political-based organization that plays a vital role in the social environment (Halim et al., 2011).

3.5.1 Cost of living acceptance by villagers in Langkawi

The cost of living for villagers in Kampung Padang Puteh, compared to other locations, is not considered significant and villagers assume that the price of goods is the same as elsewhere. However, they also assume fish sold in the village was expensive than elsewhere due to its location, which is far from fishing centers such as Bukit Malut. As a result, they had to buy fish at the nearby grocer in the village although it is expensive. Five key informants who are housewives complained about fish market prices in the village and they have the same opinion and one said that;

Now, the mackerel priced at RM15 per kg and it is very expensive. (K3, K4, K6, K13. K15)

Additionally, the villagers stated that the prices of goods varied seasonally and were very high during international events such as Le Tour de Langkawi, Langkawi International Maritime and Aerospace Exhibition (LIMA), Langkawi International Regatta, International Paintball and the Langkawi Ironman Triathlon. Due to these international events, the number of both domestic and international tourist arrivals to Langkawi has been increasing significantly. In 2000, Langkawi was visited by 1,810,460 tourists, this increased to 2.3 million in 2008 and 2.4 million in 2010. Tourist arrivals in 2013 recorded 3,410,000 after an increase of 10% from 2012 (nearly 3,059,070). However, tourist arrivals in 2016 recorded 3,634,517 after slightly increase from 2015 which is 3,624,149 (Langkawi Development Authority, 2019). Therefore, services such as homestay and rental vehicles have high demand from tourists and the charges that imposed on tourists are high too. As previous studies have shown, about 47.2% of the Langkawi community say that products are expensive and many say that their income is slightly lower than before tax-exemption, which is not seen as sufficient compensation (Federal Department of Town and Country Planning Peninsular Malaysia, 2002).

3.6 Hopes and aspirations of the local community

The future of the village depends on the local community today. Changes desired by villagers include aspects of services and facilities, culture, environment, economy, life and social relations and education.

A strategic plan for the development of infrastructure needs to be build towards the competitive tourism industry and accepted by outsiders as a safe tourist destination in the world. (K1)

Eradicate immoral activities in this village. (K10)

Environmental conservation needs to be done. Remain it till future and ensure it does not affect with tourism development. (K11)

The village is getting better and existing income can be improved. (K4)

Reduce the number of immigrants because the villagers are not really happy because they are too many in this village. (K9)

Strengthening the relationship of the villagers by organizing various activities for the young and old generation. (K7)

Low cost bus service for tourists and school students to reduce traffic congestion and parking problems. (K14)

Need of government religious schools for young generation. (K5)

Free wireless internet network (Wi-Fi) is better if it is developed in this village. (K3)

Cleanliness can be improved with the cooperation of local communities. (K2)

The role of all parties, including villagers, community leaders and the government and the private sector, is crucial in ensuring that all aspects are attained in order to achieve a better community well-being.

4. Conclusions

Community well-being is an aspect that needs to be emphasized by stakeholders in ensuring that current and future sustainable communities are in line with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The well-being of a community is achieved when their needs are fulfilled through various dimensions, such as environment, economy, education, neighborhood, life and social ties, services and facilities, politics and culture. Tourism is a major sector that contributes to island economic development. Therefore, sustainable tourism development is critical to ensure a healthy and prosperous local community. A first-class environment can help cities, towns or villages to generate higher growth, income, and living standards. To sum up, tourism development brings benefits and challenges on local communities. The lack of understanding of the impacts of tourism development is a factor that causes slow progress for third world countries in tourism development (Moscardo, 2008). Hence, the findings of this study are expected to contribute to understanding the relationship between the impacts of tourism development on the well-being of the community which covers the various aspects that need to be addressed. The findings of this study suggest that the strengthening of government, local community and the private sectors’ cooperation and collaboration to ensure that all proposed plans and programs which stress on community development and social sustainability can be well implemented in Langkawi.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hazani Hussin, Ramlah Saip, Faiszatulamyra Ibrahim and Muhamad Hazwan Alias for assistance with data collection. Special thanks are due to the staff of the Master of Environment programme (MASPUTRA), Faculty of Environmental Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia and Institute for Environment and Development (LESTARI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia for technical assistance and support.

References

- Andereck, K.L, Valentine, K.M, Knopf, R.C and Vogt, C.A (2005) ‘Residents’ perceptions of community Impacts’, Annals of Tourism Research 32(4): 1056–1076

- Andereck, K. L, Valentine, K. M, Vogt, C.A and Knopf, R.C (2007), ‘A cross-cultural analysis of tourism and quality of life perceptions’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, v15 n5: 483–502

- Andrew, F. M and Withey, S. B (1976) Social indicator of well-being, Americans’ Perception of Quality of Life, New York: Plenum Press

- Brasher, K and Wiseman, J (2008) CWB in an unwell world: Trends, challenges, and opportunities, Policy Signpost 1. McCaughey Centre

- Briguglio, L (2003) The vulnerability index and small island developing states: A review of conceptual and methodological issues, AIMS Regional Preparatory Meeting on the Ten Year Review of the Barbados Programme of Action, Online:http://www.um.edu.mt/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/44137/vulnerability_paper_sep03.pdf — accessed 4th March 2018

- Burchell, B, Day, D, Hudson, M, Ladipo, D, Mankelow, R, Nolan, J, Reed, H, Wichert, I.C and Wilkinson, F (1999) Job Insecurity and Work Intensification, York, UK: Joseph Rowntree Foundation

- Bushell, R, & Sheldon, P. J (2009) Wellness and tourism: Mind, body, spirit, place, New York: Cognizant

- Butler, R.W (1980) ‘The concept of a tourist area life cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources’, The Canadian Geographer, v24 n1: 5-12

- Butler, R.W (1994) ‘Seasonality in Tourism: Issues and Problems’, in Seaton, A.V, A (eds) Tourism: The State of the Art, Chichester: Wiley and Sons

- Cannas, R. (2012) ‘An Overview of Tourism Seasonality: Key Concepts and Policies’, Journal of Tourism, Culture and Territorial Development, 40-58

- Christakopoulou, S, & Dawson, J (2001) ‘The community well-being questionnaire: Theoretical context and initial assessment of its reliability and validity’, Social Indicators Research, v56 n3: 321–351

- Cummins, R. A (1996), ‘Assessing Quality of Life’, in Brown R.I, A (eds) Quality of Life for Handicapped People, London: Chapman & Hall: 116-150

- Cummins, R. A (1997) ‘The Domain of Life Satisfaction: An Attempt to Order Chaos’, Social Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences Indicator Research, v38: 303-328

- Dahl, A. L (1991), IUCN/UNEP Island Directory, UNEP Regional Seas Directories and Bibliographies No. 35, Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme

- Deery, M, Jago, L and Fredline, L (2012) ‘Rethinking social impacts of tourism research: A new research agenda’, Tourism Management, v33 n1: 64-73

- Din, H. A. M (2005) ‘Klasifikasi Generasi Di Malaysia’, Tesis Universiti Malaya

- Dolnicar, S, Yanamandram, V and Cliff, K (2012) ‘The contribution of vacations to quality of life’, Annals of Tourism Research, v39 n1: 59–83

- Economic & Social Research Council (2014), ‘The wellbeing effect of education’, UK Research and Innovation: https://esrc.ukri.org/files/news-events-and-publications/evidence-briefings/the-wellbeing-effect-of-education/— accessed 20th November 2018

- Emerson, E. B (1985) ‘Evaluating the impact of deinstitutionalisation on the lives of mentally retarded people’, American Journal of Mental Deficiency, v90: 277-288

- Filep, S (2012) ‘Moving beyond subjective well-being: a tourism critique’, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, v38 n2: 266–274

- Federal Department of Town and Country Planning Peninsular Malaysia (2002), Laporan Teknikal Rancangan Tempatan Daerah Langkawi 2001-2015: 20.0 Penilaian Kesan Sosial

- Flognfeldt, T (2005) ‘The Tourist Route System – Models of Travelling Patterns’, Belgeo: Revue belge de géographie, v1-2: 35-58

- Fornell, C, Johnson, M. D, Anderson, E. W, Cha, J and Bryant, B. E (1996) ‘The American. customer satisfaction index: nature, purpose, and findings’, The Journal of Marketing, 7–18

- French, J. R. P, Rogers, W, and Cobb, S (1974), ‘Adjustment as Person-environment Fit’, in Coelho, G.V, Hamburg, D. A and Adams, J.E (eds.) Coping and adaption, New York: Basic Books: 316-333

- George, D, and Mallery, P (2003), SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference,11.0 update (4th ed.), Boston: Allyn & Bacon

- Goh, H.C, Tan, W.H and Ching, F.E (2014) ‘Border Town Issues in Tourism Development: The Case of Perlis, Malaysia’, GEOGRAFIA Online: Malaysian Journal of Society and Space, v10 n2: 68-79

- Google Inc. (2018), Google Earth (Version 5.1.3533.1731) [Software], Available from https://www.google.com/earth/

- Greene J (2007) Mixed methods in social enquiry, San Francisco: Wiley

- Guest, G, Bunce, A and Johnson, L (2006) ‘How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability’, Field Methods, v18: 59-82

- Gunawan, A.A (2014) ‘Preliminary study of classifying Indonesian entrepreneurs’, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, v115: 243-250

- Gursoy, D and Rutherford, D.G (2014) ‘Host Attitudes Toward Tourism: An Improved Structural Model’, Annals of Tourism Research, v31 n3

- Halim, S. A, Komoo, I, and Omar, M (2011) ‘The Geopark as a Potential Tool for Alleviating Community Marginality’, Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures, v5 n1: 94–113

- Hamzah, A, and Mohamed, N.H (2015) ‘Social Identity and Community Resilience towards Tourism Development in Mabul Island, Semporna Sabah, Malaysia’, International Journal of Built Environment and Sustainability, v2 n4: 330-338

- Hanafiah, M, Abas, S, Jamaluddin, M, and Zulkifly, M (2013), Local community outlook on tourism development in Tioman Island, Hospitality and Tourism: Synergizing Creativity and Innovation in Research, 117

- Hanafiah, M. H, and Hemdi, M. A (2014) ‘Community behaviour and support towards island tourism development’, International Journal of Social, Education, Economics and Management Engineering, v8 n3: 787-791

- Hasani, A, Moghavvemi, S, and Hamzah, A (2016), ‘The Impact of Emotional Solidarity on Residents' Attitude and Tourism Development’, PloS One, v11 n6: e0157624

- Hylleberg, S (1992), Modelling Seasonality, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Ibrahim Komoo (2010) ‘Geopark Sebagai Peraga Pembangunan Lestari Wilayah’, AKADEMIKA v80: 7-16

- Igbaria, M, Guimaraes, T and Davis, G.B (1995), ‘Determinants of microcomputer usage via a structural equation model’, Journal of Management Information System v11 n4: 87–114

- Irwana Omar, S., Ghapar Othman, A and Mohamed, B (2014) ‘The tourism life cycle: an overview of Langkawi Island, Malaysia’, International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, v8 n3: 272–289

- Islam, G.M.N, Yew, T.Z, Noh, K.M and Nor, A.F.M (2014) ‘Community’s Perspectives towards Marine Protected Area in Perhentian Marine Park, Malaysia’, Open Journal of Marine Science, v4: 51-60

- Jurowski, C and Brown, D.O (2001), ‘A comparison of the views of involved versus noninvolved citizens on quality of life and tourism development issues’, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, v25 n4: 355–370

- Jurowski, C, Uysal, M and Williams, D. R (1997) ‘A theoretical analysis of host community resident reactions to tourism’, Journal of Travel Research v36 n2: 3–11

- Kay Smith, M, and Diekmann, A (2017), ‘Tourism and wellbeing’, Annals of Tourism Research, v66: 1-13

- Kayat, K (2002) ‘Power, Social Exchanges and Tourism in Langkawi: Rethink Resident Perceptions’, The International Journal of Tourism Research, v4 n3: 171-191

- Kayat, K and Propst, D. D (2001) ‘Exchanges between residents and tourism development’, Malaysian Management Journal, v5 n1&2: 1-15

- Kelly, C (2012), ‘Wellness tourism: Retreat visitor motivations and experience’, Tourism Recreation Research, v37 n3 : 205–213

- Keogh, B (1989), Social Impacts. In outdoor recreation in Canada, Edited by G. Wall. Toronto: Jogn Wiley & Sons: 233-75

- Kerstetter, D.L and Bricker, K.S (2012) ‘Relationship between carrying capacity of small island tourism destinations and quality of life’ in M. Uysal, R. R. Perdue, & M. J. Sirgy, A (eds) Handbook of tourism and quality of life research: Enhancing the lives of tourists and residents of host communities(International handbooks of quality of life), New York, NY: Springer: 445–462

- Lachov, G, Stoycheva, I and Georgiev, I (2006) ‘Comparative analysis of rural tourism development in some selected European countries’, Trakia Journal of Sciences v4 n4: 44–51

- Langkawi Development Authority (2019), ‘Tourist arrival statistics’, Official Website Langkawi Development Authority: https://www.lada.gov.my/en/information/statistics/tourist-arrival-statistics?style=blue — accessed 4th March 2019

- Lee, T. H (2013) ‘Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development’, Tourism Management, v34: 37-46

- Lee, S. J and Kim, Y (2015), Community Well-Being and Community Development

- Leiper, N (1979) ‘The Framework of Tourism. Towards a Definition of Tourism, Tourist and the Tourism Industry’, Annals of Tourism Research, v6: 2

- Leiper, N (1989), Tourism and Tourism Systems, Occasional Paper No.1, Department of Management Systems, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand

- Long, P.T, Perdue, R and Allen, L (1990) ‘Rural resident tourism perceptions and attitudes by community level of tourism’, Journal of Travel Research, v28: 3-9

- Lynn, M.R (1986) ‘Determination and quantification of content validity’, Nursing Research, v35: 382– 385

- Marzuki, A (2008) ‘Impacts of Tourism Development in Langkawi Island, Malaysia: A Qualitative Approach’, International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Systems, v1 n1: 1–10

- Marzuki, A (2011) ‘Resident Attitudes towards Impacts from Tourism Development in Langkawi Islands, Malaysia’, World Applied Sciences Journal 12 (Special Issue of Tourism and Hospitality), v12: 25-34

- McCool, S. F and Martin, S. T (1994) ‘Community attachment and attitudes toward tourism development’, Journal of Travel Research v32 n3: 29–34

- McGillivray, M (2007), ‘Human Well-being: Issues, Concepts and Measures’, in Mark McGillivray, A (eds) Human Well-Being: Concept and Measurement, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan

- McGillivray, M and Clarke, M (2006), ‘Human Well-being: Concepts and Measures’, in Mark McGillivray and Matthew Clarke, A (eds) Understanding Human Well-Being, Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan

- Moghavvemi, S, Hamzah, A and Paramanathan, T (2016) ‘Resident’s attitude towards tourism contributions to the community and overall effect of tourism developments: a comparison study among residents in langkawi island, perhentian island and mabul island’, Journal of Global and Regional Studies v1: 1-49

- Mohd Bakri, N, Jaafar, M and Mohamad, D (2014), Perceptions of Local Communities on the Economic Impacts of Tourism Development in Langkawi, Malaysia. SHS Web of Conferences 12, 01100