A Consideration of the Characteristics and Historical Background of Japanese Fusion Cuisine Created Through Cross-cultural Exchanges with the West in Port Cities

Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, Pukyong National University, Republic of Korea kongmihe@pknu.ac.kr

Abstract

This study examines the historical facts about the invention and development process of Sukiyaki and Tonkatsu in Japan around the foreign settlements formed by the then Japanese government’s policies to enhance national prosperity and military power and promote a meat-eating culture and the opening of ports, based on the circumstances of the times. The results can be summarized as follows.

- Sukiyaki, well known as a typical fusion dish that combines Japanese traditional cuisine and Western culture, was born with the beef-eating culture that emerged with the cross-cultural exchanges with the West since the 17th-century Edo period. As a beef dish harmonizing Japanese traditional condiments and Western beef, it was first known as “Sukiyaki” in the Kansai region and as “gyu nabe” in the Kanto region, which use similar ingredients but differ in the cooking process and methods. Under the impact of the Kanto Earthquake in 1923, the two terms were integrated into “Sukiyaki,” which is the current name of this type of dish.

- Another Japanese-Western fusion dish, Tonkatsu, born from pork, the main ingredient of the dish, began to be supplied to the Japanese market as a cheaper substitute to beef that was then in short supply due to rising demand. Tonkatsu emerged as part of the Japanese government’s policies to promote a meat-eating culture in order to enhance national prosperity and military power. The supply of pork as military food greatly influenced the spread of Tonkatsu, which came to have its present form during the era of Japanese imperialism.

Keywords

Cross-cultural exchange, Japanese meat, Meiji, Sukiyaki, Tonkatsu, and Food culture

1. Introduction

It was during the 17th-century Edo period under the Tokugawa Shogunate that Western cuisine was first introduced in the process of exchange with Westerners in the foreign settlements at Hirado and Dejima in the port city of Nagasaki. Before the Meiji era, in 1862, steamed beef started to be sold at Irifune-cho (横浜入船町), a foreign settlement in Yokohama, a port city. When the demand for beef increased, the first gyu nabe restaurant opened at Shibatsuyutsuki-cho (芝露月町) early in the Meiji Era. In 1869, a Sukiyaki restaurant started a business at Motomachi (元町), Kobe. Prior to the announcement of the Meiji government’s lifting of the ban on meat eating (1872), a food culture of consuming beef had already being formed around foreign settlements in port cities.

The Meiji government and intellectuals implemented a policy to spread a meat-eating culture to the common people in the process of carrying out a policy for national prosperity and military power enhancement under the perception that they gained while exchanging with Westerners: The Japanese had a smaller build and weaker physical strength.

As part of the process of spreading a meat-eating culture, the Meiji government promoted the popularization of Western cuisine, absorbing Western food culture and modern civilizations. The imperialist policies aiming at modernization based on the acceptance of Western culture and the enhancement of national prosperity and military power that had been implemented since the Meiji era were further strengthened after the Sino-Japanese War. As beef was supplied to the military for soldiers’ meals, there was a shortage of beef in the market. Consequently, pork became popular as a substitute, which brought about a food culture related to pork and the birth of Tonkatsu, another Japanese-Western fusion dish.

The consideration of the meat-eating culture of Japan that seemingly has no relation to its history of invasion leads to the recognition of many aspects of the history of Japan and Korea that the latter should have been vigilant about. The fusion cuisine and meat-eating culture spread all over Japan through military meal service. Therefore, if Koreans had had insight and wisdom to understand the relationship between Japan's military expansion and its imperialist policies and ambition of the invasion of Korea and to proactively respond to it, Korea could have avoided the colonialization by Japan. This kind of insight and wisdom is still needed for Koreans to lead their country in the future. Okada Tetsu (岡田 哲), the author of “The Beginning of the Meiji Era Western Cuisine History: The Birth of Tonkatsu” (明治洋食事始め--とんかつの誕生, 2012), writes that the Meiji government lifted the ban on meat consumption as part of its policy to make its country and military wealthy and strong, thus introducing its praise for beef to promote Western cuisine and the contribution of the common people to the birth of gyu nabe, Sukiyaki, anpan (a sweet roll filled with red bean paste), and Tonkatsu.

Kosuge Keiko (小菅桂子), a Japanese cooking researcher, explains in “Stories about Japanese Western-style Food” (にっぽん洋食物語大全, 1994) how the Japanese introduced Western food and developed it into its own food culture from the invention of various dishes such as Tonkatsu, korokke (a Japanese-style croquette), and kare raisu (curry with rice), to the establishment of table manners. Also, in “The Birth of Kare Raisu” (カレーライスの誕生, 2013), she insists that the introduction of curry and its application to this Japanese-Western fusion dish serves as a historical basis for the acceptance and Japanese-style transformation of Western civilizations in modern Japanese society.

Hashimoto Naoki (橋本直樹) mentions in “What is Japanese Traditional Culture” (日本食の伝統文化とは何か―明日の日本食を語るために, 2013) that the Chinese continent served as a channel for the introduction of foreign food cultures to Japan and that the Japanese established their own culture by accepting advanced cultures through exchanges with China and Korea. In addition, the author discusses the Japanese-Western fusion dishes such as gyu nabe, kare raisu, korokke, and Tonkatsu, which are the results of the Japanese-style transformation of the Western dishes introduced to Japan during the Meiji era.

Cwiertka (2006) focuses on the changes in Japanese cuisine since Japan’s opening of its ports in the 19th century and considers how Japan’s national cuisine developed. These aspects are illustrated in her discussion of the influx of Western culture, urban cuisine, wars, and high economic growth before and after the rise of imperialism and militarism during this period. Against this background, the author investigates the impact of Japanese militarism and the wars and imperialism based on its influence on the modernization of Japanese dining.

Majima Ayu (真嶋亜有) examines the changes in the discourse on meat eating and the development of the livestock industry through military expansion during the Meiji era in “The Modernity of Meat Eating: The Military Demand for Meat and the Characteristics of Viewpoints toward Meat Eating in the Meiji Japan” (肉食という近代一明治期日本における食肉軍事需要と肉食観の特徴一, 2002).

Most Japanese literature pertaining to the topic of these fusion dishes only introduce the development process of the dishes regardless of the historical background such as the then Japanese government’s policy for the enhancement of national prosperity and military power and its imperialist policy. This study, however, intends to maintain its focus on the fact that Sukiyaki and Tonkatsu were invented and developed into representative Japanese-Western fusion dishes in a very systematic and intentional way in accordance with these policies.

Therefore, this study examines the historical facts about the emergence of gyu nabe and Sukiyaki around the foreign settlements of Japanese port cities, which were formed in the wake of the government’s policy for increasing national prosperity and strong military power and the opening of ports based on the consideration of the circumstances of the times. This study also looks at the conflicts that the Japanese society experienced in the process where Western cuisine was popularized among the common people in accordance with the government’s policy after the lifting of the ban on meat consumption of Emperor Meiji. Furthermore, the study examines the birth of Tonkatsu through the spread and acceptance of Western cuisine among the commoners in the course of cross-cultural exchanges.

2. Policies to Enhance National Prosperity and Military Power and Promote a Meat-Eating Culture

The Meiji government embraced Western cultures to recreate Japan into a modern country similar to the Western powers. The state longed to overcome the country’s physical inferiority complex and be on a par with the Westerners in terms of physical stature and condition by promoting meat consumption. Popularizing Western cuisine as part of its policy to spread a meat-eating culture, the Meiji government sought to absorb the Western food culture, along with modern civilization, colonialist, and imperialist policies. The Japanese had maintained a food culture of prohibiting meat consumption for 1,200 years since Emperor Tenmu’s ban on eating meat in 675 under the influence of traditional Buddhist culture. However, in 1872, with the removal of the ban by Emperor Meiji, the government and intellectuals began actively promoting meat consumption to enhance national prosperity and military power.

The meat-eating habit that failed to penetrate Japanese society after the introduction of Buddhism revived during the Sengoku period. At that time, soldiers who were unable to obtain food on the battlefields would steal cattle from farmhouses and eat the meat by seasoning it with the soybean paste that they carried with them (Horio and Yokoyama, 2016).

Also, the Nanban (Portuguese and Spanish) trade and Western missionaries influenced the meat-eating culture of the time. From the mid-16th century, Portuguese missionaries entered Japan to spread Christianity, which led to the rapid increase in the number of Christians in the country. People who converted to Christianity were freed from the taboo against meat eating and started to enjoy European-style meat dishes (Ishige, 2017).

The preference for the Nanban cuisine spread around Kyushu, by Christians, contributing to the spread of meat eating. There is a historical record that the Shimazu Army of Satsuma moved live pigs to battlefields to provide pork to soldiers. Later, however, meat eating was banned again by Toyotomi (Horio and Yokoyama, 2016)

Meanwhile, although the Japanese had raised chickens from ancient times, they had rarely eaten chicken and eggs. Also, as horses had been used as a means of transportation by the upper class and cattle had been indispensable in the lives of farmers, the Japanese generally had not considered procuring meat from them. However, as cattle had not been regarded as significant, as compared to the farmers, by the upper class, they had practiced a conditional meat-eating habit to replenish nutrition, which violated the ban on meat consumption. To consume beef, a Western ingredient, they had cooked it in a Japanese style, seasoning it with soybean paste. Based on the recipes of cooking meat with soybean paste, the gyu nabe was later invented in the Kanto region.

One of the biggest changes in the diet of the Japanese during the Meiji era was the lifting of the ban on the use of four-legged livestock such as cattle and hogs for meat, and the introduction of a meat-eating culture that re-shaped their everyday food culture.

The Meiji government actively absorbed the cultures of the advanced civilizations of Europe and America as part of its movement for the enlightenment of the nation. The movement, which spurred modernization and promoted the development of industries and the growth of production, further sought national prosperity and strong military power. In addition, the Meiji government promoted a meat diet through nutrition education, cooking practice education, and media such as newspapers and magazines for women in order to establish a meat-eating culture in Japanese society. The meat diet was also introduced to the military. The Imperial Army actively introduced a diet combining traditional Japanese foods that the Japanese had been accustomed to before the war period and Western foods and meat, such as cutlets and croquettes, etc.

In 1869, the beef Sukiyaki restaurant Gekkatei (月下亭) opened in Motomachi, a foreign settlement in Kobe, but it did not earn a good reputation. As the commoners lacked recipes for beef, which was introduced to them through the government’s policy to increase national prosperity and military power, they began consuming beef by cooking it using traditional condiments such as soybean paste. As the demand for beef soared and its supply was insufficient, pork, which was cheaper than beef, began to be supplied to the market. In 1900, the Japanese government launched a project to foster hog raising. Subsequently, the Russo-Japanese War, which broke out in 1904, contributed to the popularization of pork. Because beef was in short supply as it was supplied to the military, pork drew attention as a substitute. In the middle of the Meiji era, pork food culture was widely spread in the society and people became acquainted with Western pork cuisine as the pork food culture was created and the fusion dish Tonkatsu was invented.

From the Meiji era, the Japanese government strengthened its imperialist policies implemented since the start of the period aiming at modernization and the enhancement of national prosperity and military power based on the embracement of Western culture after the Sino-Japanese War (Nishikawa, 2010).

However, in the 1860s, the Japanese colonialist militarists came up with a definite theory. In 1875, Japan, which had been involved in the Unyoho issue, entered into the Korean-Japanese Treaty of Friendship February 27, 1876. It can be considered that it has begun to appear in earnest. After the failure in 1884, the Japanese, who favored Joseon, had a definite view, and Fukuzawa published ‘Datsu-A Ron (Theory of Escaping from Asia)’ on Jiji Shinpo’s news on March 16, 1885.

In addition, based on his imperialist ideas (Mitani, 2018), he urged the introduction of policies for increasing national wealth and promoting the progress of civilization (Suzuki, 2009) and emphasized the importance of balanced diet including meat and milk, pointing out that the traditional Japanese diet makes people prone to various diseases.

The removal of the existing ban on meat by Emperor Meiji in 1872 brought about arguments for and against meat eating while the upper class welcomed the lifting of the ban. However, the discourse on the meat diet turned to a political issue through the changes in the social conditions, such as the increased demand for meat from the military in the wake of the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars. In order to secure large quantities of meat in accordance with the increase in armaments, Japan began importing cattle from Korea. The Meiji government placed not only the import of Korean cattle, but also the Korean livestock industry under its administration.

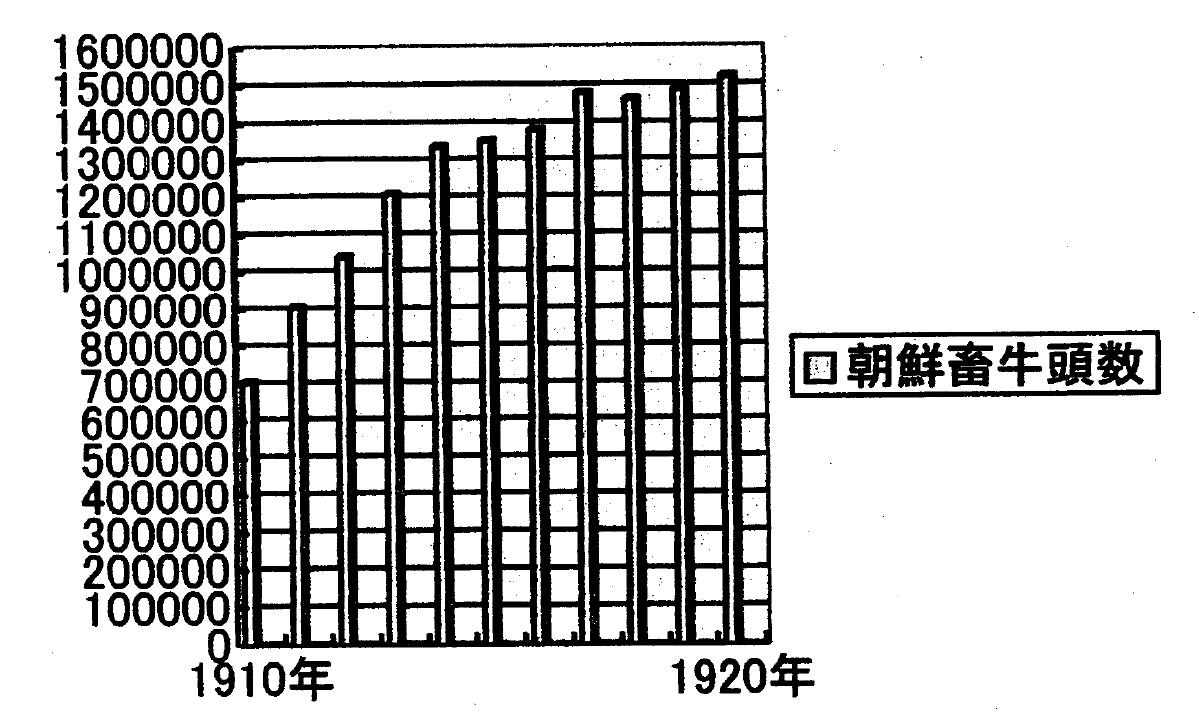

So, the policies related to the import of Korean cattle were actively promoted during the Russo-Japanese War, and the number of imported Korean cattle surged after Japan’s annexation of Korea. In 1910, Japan imported about 0.7 million cattle from Korea, but the number rose to about 0.9 million in 1911, to 1.04 million in 1912, and to 1.21 million in 1923. In short, the number increased by 0.2 million per year (See Figure 2).

That is, in the process of controlling and developing the Korean livestock industry for food supply to Japan, meat eating gained a symbolic meaning of modernity as a product of colonialism (Majima, 2002). With these Japanese historical and political backgrounds taken into consideration, gyu nabe, Sukiyaki, and Tonkatsu can be regarded as Japanese-Western fusion dishes that were born and developed in accordance with the Japanese government's policy to increase national prosperity and military power during the Meiji era that marked the onset of the imperialist period.

| Year | Key Changes | Details |

|---|---|---|

| The 1860’s | The rise of the Seikanron | The Seikanron (Debate on the Invasion of Korea) debate started by the Japanese militarists who sought the enhancement of the national prosperity and military power |

| 1869 | Thick sirloin used for Sukiyaki | The Sukiyaki restaurant Gekkatei (月下亭) opened in Motomachi, a foreign settlement in Kobe |

| 1872 | The lifting of the existing ban on meat eating and the promotion of meat consumption | The removal of the ban on meat eating by Emperor Meiji, which led to the active promotion of meat consumption by the government and intellectuals |

| 1876 | The signing of an unequal treaty | The US-Japan Treaty of 1876, which was an unequal treaty, concluded between the two countries on February 27; the launching of imperialist policies |

| 1884 | The expansion of the Seikanron | After the failure of the Gapsin Coup in Korea, the Seikanron spread among the Japanese who were favorable to Korea |

| 1885 | The rise of the Datsu-A Ron | The imperialist Fukuzawa Yukichi (福澤諭吉) published “Datsu-A Ron (Theory of Escaping from Asia) in Jiji Shinpo (時事新報) on March 16, in which he urged the policy for the improvement of the national prosperity and military power, emphasizing the need for increased meat consumption |

| 1900 | The launching of nationwide pig-raising project | A nationwide pig-raising project launched by the Japanese government as part of its policy to increase the national wealth and military power |

| After 1904 | The supply of pork to the military for meal service | The outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War; Meal service in the military greatly affected the popularization of pork. |

| After 1910 | Meat eating culture as a product of colonialism | The symbolic meaning of modernity attached to meat eating in the process of controlling and developing the Korean livestock industry for food supply to Japan |

3. The Birth of Fusion Cuisine through Cross-Cultural Exchanges with Westerners in Port Cities

3.1. The Birth of Sukiyaki

In the 17th century under the Tokugawa Shogunate, the Japanese were exposed to opportunities to experience Western cuisine, including Portuguese and Spanish (Nanban) cuisine and Dutch (Komo) cuisine1, in foreign settlements at Hirado and Dejima in the port city of Nagasaki. The Nanban and Komo cuisine is regarded as the first Western cuisine introduced to Japan. Western dishes such as cocido2 and picado3 that used both meat and vegetables started to spread among the upper class and merchants of Nagasaki. At this time, onions, potatoes, carrots, pumpkins, red peppers, corn, pomegranates, and strawberries were also introduced to Japan, allowing the Japanese to experience various dishes. Three Japanese cooks called “Dejima kuzuneri” (出島くずねり) were dispatched from the Nagasaki Bugyosho (Magistrate’s Office) to the Dejima Dutch Trading Post. The Dejima kuzuneri had played the role of procuring and preparing food since the Edo period and was the first to introduce Western cuisine to Japan. They learned Western cuisine while performing the job of dishwasher at the Dejima Dutch Trading Post. In 1863, Kusano Joukichi (草野丈吉), one of these cooks, opened Japan’s first western restaurant in Nagasaki (Hiroma, 2014). Kusano received culinary training under the supervision of the Dutch consul general and named his restaurant Ryorintei (良林亭). These cooks who worked in Dejima laid the foundation for the development of Western cuisine in Japan since the Meiji era.

With the opening of ports after the US-Japan Treaty of 1858, Japan began to actively exchange with the US, the UK, France, the Netherlands, Russia, and other Western countries. The cross-cultural exchanges centering on foreign settlements in port cities also created opportunities for Japanese interpreters and government officials who often visited the areas to taste beef. The increase in trade and exchange with foreigners led to a surge in demand for beef, mainly in foreign settlements, resulting in a shortage of beef. At that time, as the cattle-raising livestock industry was not developed in Japan, cattle were imported from Europe, the US, China, and Korea, and was butchered on board ships (Nakazato, 1990). In 1865, beef processing facilities for foreigners were installed in the port city of Yokohama, and in 1866, beef produced in the port city of Kobe began to be supplied to Yokohama and Tokyo. Sukiyaki restaurant was opened in 1869 by Kobe Motomachi, a foreign-born settlement, and the beef Sukiyaki house Gekkatei opened its shop, but its reputation was not good. The Meiji government and intellectuals, thinking that the Japanese were inferior to Westerners in terms of physique and strength, implemented a policy to spread the meat-eating culture to the common people as part of their efforts to enhance the country’s prosperity and military power.

The Japanese government believed that it was necessary to embrace the Western culture and cuisine in order to develop Japan into a modern nation like those of the Western powers and to achieve national prosperity and strong military power. Therefore, the state praised Western cuisine and promoted it nationwide. Western food culture spread among the upper class who first accepted Western foods through cross-cultural exchanges with the West. However, the commoners were still unfamiliar with the meat-eating culture, mainly because of the antipathy against Western culture caused by the Meiji government's radical reform, the influence of Buddhist culture, and the low preference for beef dishes. Repulsion towards eating beef was still felt among the common people.

Kanagaki Robun (假名垣魯文), a journalist from the late Edo period to the early Meiji era who was greatly influenced by Fukuzawa Yukichi (福澤諭吉), promoted meat eating in “Aguranabe (The Beef Eater, 牛店雑談 安愚楽鍋) (Okada, 2012).” Also, Kato Yuichi (加藤祐一), an enlightenment reformer, emphasized the significance of the consumption of meat such as beef and pork.

Under the influence of the government’s policies to establish a wealthy country and strong military power, and promote enlightenment and reform, the early Meiji era (around 1873) saw the increased interest in incorporating beef into Japanese cuisine, such as gyu nabe (the Kanto region) and Sukiyaki (the Kansai region), among the commoners.

In the Kanto region, beef restaurants used venison, wild boar meat, and horsemeat as well as beef. Since the beef at that time was tough and had a strong smell of fat, it was often boiled down using the traditional Japanese condiment soybean paste to remove the odor. That is, gyu nabe was a fusion dish that cooked beef, which had been introduced from Western cuisine, with traditional Japanese condiments such as soybean paste. As the meat quality was improved and various ingredients such as green onions, tofu, and pine mushrooms were added, and the warishita4 (割り下) broth, made with soybean sauce, sugar, anchovy broth, and mirim started to be used to simmer the beef, gyu nabe was further enhanced. On the other hand, residents in the Kansai region employed a different method to prepare Sukiyaki. They first cooked the beef in a pan and seasoned it with sugar and soy sauce. The seasoned meat was then boiled and added to the other ingredients in order, starting from the vegetables as they had the highest moisture content. Sukiyaki was different from gyu nabe, which was made by boiling meat and vegetables at the same time after placing the ingredients in the warishita broth. However, in that the Sukiyaki incorporated beef, a Western ingredient, and was cooked with traditional Japanese condiments, it can be also classified as a fusion dish. It has been presumed that Sukiyaki originated from the Edo period farmers’ habit of cooking fish or tofu on the metal parts of their farming tools such as plows when they got hungry while working. It has been also argued that the farmers used cedar wood boards instead of farming tools to cook their meals. However, it has been widely known that Sukiyaki originated from uosuki5, a dish that was popular in the Kansai region. The fish of uosuki was replaced by meat and the name of the dish also changed to Sukiyaki.

Japanese-Western fusion cuisine, not authentic Western cuisine, emerged from the middle to the late Meiji era. Kawabata Shoko, an authority on culinary arts, states that Japan’s unique fusion cuisine greatly influenced the birth of Western-style Japanese cuisine in “The Development of Western Cuisine (Western-style Japanese Cuisine, or Fusion Cuisine).” From around 1897, the term “Japanese-Western fusion cuisine” began gaining popularity, referring to the cuisine between Japanese cuisine completed during the Edo period and authentic Western cuisine. In 1886, Western cuisine was included in the curriculum of the girls’ schools in Tokyo and culinary education grew more active in these schools at the request of the parents who wanted their daughters to be acquainted with fusion cuisine. When Western cuisine was first introduced to Japan, the Japanese were mainly influenced by cross-cultural exchanges as they learned recipes from Westerners. However, it was the influence of internal exchanges rather than that of cross-cultural exchanges that greatly contributed to the birth of fusion cuisine. Many of Tokyo’s gyu nabe restaurants that were severely devastated by the Kanto Earthquake in 1923 were forced to close. Subsequently, as the Sukiyaki restaurants in the Kansai region were expanded to the Kanto region, the term “gyu nabe” was integrated into “Sukiyaki.” Since then, Sukiyaki has been known as a representative dish of Japanese-Western fusion cuisine around the world.

| Year | Key Changes | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1866 | The supply of beef | Beef produced in the port city of Kobe started to be supplied to Yokohama, Tokyo and other regions |

| 1869 | The opening of the first Sukiyaki restaurant | The Sukiyaki restaurant Gekkatei (月下亭) opened in Motomachi, a foreign settlement in Kobe |

| 1871-1872 | Sukiyaki found on the menus of restaurants | Sukiyaki mentioned in “Aguranabe” (The Beef Eater, 牛店雑談 安愚楽鍋)" by Kanagaki Robun (假名垣魯文), a journalist from the late Edo period to the early Meiji era who was greatly influenced by Fukuzawa Yukichi |

| Around 1873 | Increased interest in gyu nabe (the Kanto region) and Sukiyaki (the Kansai region) | Increased interest in gyu nabe (the Kanto region) and Sukiyaki (the Kansai region), which are the Japanese dishes using beef, among commoners |

| Around 1897 | The coinage of the term “Japanese-Western fusion cuisine” | The term “Japanese-Western fusion cuisine” popularized in Japanese society |

| Around 1923 | The integration of “gyu nabe” into “Sukiyaki” | The closing of most gyu nabe restaurants in Tokyo due to the Kanto Earthquake in 1923; The entrance of Sukiyaki restaurants into the Kanto region, leading to the integration of “gyu nabe” into “Sukiyaki” |

3.2. The Birth of Tonkatsu

In the early Edo period, pigs were introduced to Satsuma6 from China via Ryukyu (the present Okinawa). Satsuma soup (Satsuma jiru), which used pork as the main ingredient, gained popularity among Japanese swordsmen and Rangaku (Dutch or Western Learning) scholars and medical practitioners in the port city of Kyushu, despite the ban on the slaughter of livestock, and even spread to Edo. As the Chinese people living in Nagasaki started to raise pigs, Dejima’s Dutch people processed pork into ham and sausages. Therefore, in Nagasaki and Satsuma, the custom of eating pork was preserved from earlier times.

After the Meiji Restoration, Tsunoda Yonesaburo (角田米三郎) founded the Kyokyusha (協救社) in 1869, and sought to improve the national prosperity and military power by fostering school establishment and railroad construction through pig farming, which promoted the consumption of pork (Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Public Library. 2003). With the popularization of pork in the middle of the Meiji era, the Japanese became acquainted with the Western cuisine for pork, and a food culture related to pork was created. With the soaring demand for beef, which is an essential ingredient of Western cuisine, it became difficult to secure beef due to insufficient supply. Therefore, pork, which was cheaper than beef and the primary ingredient of Tonkatsu, began to be supplied to the market. In 1900, the Japanese government actively fostered pig raising by importing breeding pigs from the US and the UK in order to respond to the shortage of beef, which was supplied to the military for the soldiers’ meals. At the same time, meat eating was promoted as part of the country’s policy for national prosperity and military power increase, which led to the active popularization of pork. Steadily, the common people became more familiar with pork through the spread of Western cuisine, and from 1882 to 1883, demand for pork began to soar in Tokyo. Also, as exchanges with foreigners from different countries increased during this period, the Japanese people began to pay more attention to pork, which established the foundation for the invention of Tonkatsu. Tonkatsu was first made in Japan approximately 60 years after the recipe for horu katsuretsu (ホールクコツトレツ) was introduced to the country in 1872 through “The Western Cuisine Expert” (西洋料理通) written by Kanagaki Robun (仮名垣魯文). “Horuku” means pork and “katsuretsu” means cutlet, which is pork meat attached to the ribs or sirloin covered with flour, not breadcrumbs, and then fried in a frying pan with a small amount of oil. The term “pork katsuretsu,” which has the same meaning as “horuku katsuretsu,” is a combination of “pork” and “katsuretsu,” the Japanese pronunciation of “cutlet.” Pork katsuretsu, the predecessor of Tonkatsu, began to be sold in 1895 at Rengatei (煉瓦亭) in Ginza, Tokyo, and was served with cabbage. Ginza, where this restaurant was located, was close to a foreign settlement in Tsukiji Akashi-cho and the Tonkatsu of this restaurant was popular among regular foreign customers as it was a Western-style dish that they could not taste in their countries. During this time, a number of fusion cuisine restaurants began to open. These restaurants used more than half of the pork that they secured for Western dishes such as pork katsuretsu. The historical records on Tonkatsu and the restaurants that served the dish are as follows.

Nagai Kafu (永井荷風)’s essay “Ginza” (銀座, 1911) refers to the Japanese Tonkatsu served by street vendors (Nagai, 1986). It also writes that new fusion dishes called “Tonkatsu kare” (カツカレー, curry rice with a pork cutlet) and katsudon (カツ丼, rice topped with a pork cutlet) were invented and started to be served in local restaurants in 1918 and in 1921, respectively. Also, in 1921, the Tonkatsu specialty restaurant Oroji (王ろじ) in Shinjuku began to sell the Tonkatsu made by frying thick pork sirloin that was then cut into bite-sized pieces. In 1929, Shimada Shinjiro (島田信二郎), who was working at Ponchiken (ぽんち軒) in Okachimachi (御徒町), Ueno, Tokyo, invented a new type of Tonkatsu. Instead of roasting pork on a Western frying pan with a small amount of oil, he applied a deep frying method in fat, soaking the pork in oil and frying it until it was cooked deep inside. This method made it possible to fully cook 2.5cm-3cm thick meat. Gradually, the pork meat used for Tonkatsu was replaced by the boneless variety that could be eaten with chopsticks, and breadcrumbs were used instead of flour for the batter. In addition, cutlets began to be served cut into small pieces to allow customers to eat the Tonkatsu with chopsticks without knives or forks reminiscent to when they ate Japanese dishes. With the addition of chopped cabbage to the dish, the present Japanese Tonkatsu was completed.

Since then, Tonkatsu was accompanied by the side dish of chopped cabbage, which went well with soybean paste soup and rice. In addition, the chopped cabbage removed the smell of fat, adding freshness to the dish. In 1932, restaurants claiming to be Tonkatsu-specialty restaurants (楽天, 喜田八, 井泉, etc.) opened one by one in Ueno and Asakusa, creating a Tonkatsu craze in Downtown Tokyo. By this time the term “Tonkatsuretsu” was often found in cookbooks and menus. The term “Tonkatsu” was established through the naming evolution from horuku katsuretsu → pork katsuretsu → Tonkatsuretsu → Tonkatsu. The difference between the whole cutlet and the Japanese Pork Cutlet can be seen in the following in Figure 3.

| Whole cutlet | Japanese Pork Cutlet |

|---|---|

| The Western Cuisine Expert: pork | First: beef, chicken Later: pork |

| Meat on bone | Bone-free meat that can be eaten with chopsticks |

| Only flour on the surface and no bread crumbs | Use flour and bread crumbs. |

Tonkatsu, a Japanese fusion dish, was born and developed under the influence of Western cuisine during the time when pig raising was fostered nationwide as part of the Japanese government’s policy for promoting national prosperity and a strong military. The spread of pork as a food for the Japanese military greatly influenced the popularization of Tonkatsu, and the present Tonkatsu was completed in the age of Japanese imperialism. In 1958, after the defeat of Japan, the first store of Wako (和幸), a Japanese chain of Tonkatsu restaurants, was opened. This restaurant used a wire net when frying pork to prevent the batter from becoming soggy and to keep it crispy. It also provided new services, offering free refills of chopped cabbage and soybean paste soup, which intensified competition among Tonkatsu-specialty restaurants.

| Year | Key Changes | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1895 | The birth of pork katsuretsu | Pork katsuretsu, the predecessor of Tonkatsu, started to be sold at Rengatei (煉瓦亭) in Ginza, Tokyo, served with chopped cabbage |

| 1921 | Thick sirloin used for Tonkatsu | The Tonkatsu specialty restaurant Oroji (王ろじ) in Shinjuku began to sell the Tonkatsu made by frying thick pork sirloin and then cut into bite-sized pieces. |

| Around 1929 | The establishment of the current Japanese Tonkatsu style | Ponchiken (ぽんち軒) in Okachimachi, Ueno, Tokyo, invented and started to sell a new type of Tonkatsu.

|

Conclusions

This study examined the historical facts about the emergence and development process of Sukiyaki and Tonkatsu in Japan around the foreign settlements formed by the then Japanese government’s policies to enhance national prosperity and military power and promote a meat-eating culture and the opening of ports, based on the circumstances of the times. It also investigated the historical facts about the birth and evolution of Tonkatsu, a fusion dish created by using pork during the time of beef shortage due to its soaring demand in Japan and in response, the supply of pork to the market as a substitute. The results of the analysis can be summarized as follows.

- The Japanese meat-eating culture was formed based on the government’s policy for increasing national prosperity and strong military power, and it is a culture born when the tradition of banning meat eating changed to the meat-eating promotion policy.

- The meat-eating culture was promoted by the Japanese government to overcome the nation’s physical inferiority complex based on cross-cultural exchanges with Westerners. This was closely related to the government-led embracement of the food culture, scientific knowledge, and the imperialist policies of the West.

- The Japanese common people initially expressed repulsion towards the meat diet and the government policy that promoted meat-eating was initially not very successful. However, the introduction of the meat diet to the military played a major role in spreading the meat-eating culture.

- Sukiyaki, a well-known fusion dish that combines Japanese traditional cuisine and Western food culture, was developed with the introduction of the beef-eating culture through cross-cultural exchanges with the West since the 17th-century Edo period. Sukiyaki is a dish that harmonizes traditional Japanese condiments and beef, the main ingredient of Western cuisine. In the past, it was known as “Sukiyaki” in the Kansai region, and as “gyu nabe” in the Kanto region. Both recipes incorporated similar ingredients but differed in the cooking process and methods. Under the influence of the Kanto Earthquake in 1923, the two terms were integrated into "Sukiyaki." Today, this type of dish is collectively called “Sukiyaki.”

- Another Japanese fusion dish, Tonkatsu, was invented as the difficulty in procuring beef increased due to its surge in demand as well as its shortage. In response, pork, which was cheaper than beef and a main ingredient of Tonkatsu, began to be supplied to the market under the Japanese government’s policy to enhance the national prosperity and military power and to promote meat eating. The spread of pork as food for the Japanese military greatly influenced the popularization of Tonkatsu, and the present Tonkatsu was completed in the age of Japanese imperialism.

- This study shows that the historical background, which entailed the Japanese government’s policy to enhance the national prosperity and strengthen its military power, the embracement of Western culture, the promotion of a meat-eating culture, imperialist policies, and the aggressive wars, are closely related to the birth and development of beef dishes such as Sukiyaki and pork dishes such as Tonkatsu.

- It is not fair to consider that the common people of Japan, who invented and developed Sukiyaki and Tonkatsu, were also closely related to the policies of the Japanese government. They succeeded in creating and developing the internationally known Japanese fusion dishes because they made great efforts to invent their own delicious dishes through research and much trial and error. Their efforts and attitudes provide a good model for Korean cuisine.

This study analyzed the historical backgrounds of Sukiyaki and Tonkatsu, the fusion dishes created through cross-cultural exchanges with Western countries in the port cities of Japan. It was proved that the food culture, which seems to have no relation to the historical facts of the aggressive wars waged by Japan, was closely related to the country’s policy for the promoting national prosperity and strong military power and imperialist policy. However, the successful cases of the invention and development of new and unique fusion cuisine by combining traditional Japanese and Western food cultures through cross-cultural exchanges with the West can serve as a model for Korean cuisine. It is expected that Korea also develops fusion cuisine and products preferred by the world through the acceptance of these models.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017S1A6A3A01079869).

Endnotes

References

- Cwiertka, Katarzyna J., 2006. Modern Japanese Cuisine: Food, Power and National Identity, London:Reaktion Books.

- Fukuzawa Yukichi, Nishiuchi, and Hiroshi Kato. Japanese Studies 40, 377-391.

- Hashimoto, N., 2013. What is the traditional culture of Japanese food - to talk about the Japanese food of tomorrow. Lifestyle culture history selection book, 99–120, 171–173.

- Hiroma, J., 2014. Background of Osaka’s first Western-style hotel opening and food procurement. Osaka Tourism University Tourism Studies Institute Report, Tourism & Tourism No. 19, 38-41.

- Horio, H. and Yokoyama, T., 2016. Food culture of Muromachi, the Azuchimomoyama era. Journal of the natural scientific society of nagoya keizai university 49(1・2), 43-45.

- Ishige, N., 2017. The history of food culture exchange - Japan as an Example. Special Issue Social System Research, 9–12.

- Kosuge, K., 1994. Nippon Western food story fullness. Kodansha.

- Kosuge, K., 2013. The birth of curry and rice. Kodansha Scholarship Library.

- Majima, A., 2002. Characteristics of Meat military demand and carnivorous view in Japan during modern Meiji Period as carnivorous. International Christian University Asian cultural institute 11, 213-230.

- Mitani, T., 2018. Civilization, Westernization, and Modernization: Fukuzawa Yukichi and Maruyama Makoto — Leaders and Critics of Japanese Modernism. Proceedings of the Japan Academy Vol.72, 209-227. Nagai, K., 1986. on Ginza Kaze no Ikko. Iwanami Shoten Iwanami Bunko (original paper July 1911).

- Nakazato, A., 1990. Import of Korean cow in Meiji and Taisho. Bulletin of Historical Geography No. 32, 142-249.

- Nishikawa, Y., 2010. Strategic Culture and War in Japan. Research on Moon International Area Studies No. 13, 3-4.

- Okada, T., 2012. The Meiji Western food Inception -The Birth of the Tonkatsu. Kodansha Scholarship Library, pp.9-245.

- Suzuki, S., 2009. Freedom and Equality in the Enlightenment Thought of Japan in the Meiji Era.

- Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Public Library. 2003. Collection Presentation from Archives of Archives. From the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Architecture No. 3, 1-2.