Contest For Seascape: Local Thalassocracies and Sino-Indian Trade Expansion in the Maritime Southeast Asia During the Early Premodern Period

Diponegoro University, Indonesia singgihtrisulistiyono@gmail.com

Diponegoro University, Indonesia

Diponegoro University, Indonesia

Abstract

The focus of this paper is to examine the response of local thalassocracies during the expansion of Indian and Chinese trade to maritime Southeast Asia during the transitional era between the end of the ancient and the beginning of the pre-modern period, with the particular focus on the contesting seascape among local the emporiums. This study is significant to be conducted since the role of local initiatives in international maritime trade during the early maritime relations between India and China is still not widely known. The historical narrative on the part of Southeast Asian people in the maritime trade relations between India and China is still vague. For this purpose, this article will address some of the issues related to the role of local emporium in the contexts of the expansion of the two giants, India and China, to the Southeast Asian maritime world and how sea space contestation occurred not only between India and China but also among local powers that wanted to control international maritime trade relations between India and China.

Keywords

Seascape, Maritime Trade, Sino-Indian Trade Expansion, Maritime Southeast Asia, Silk Road, Thalassocracy

I. Introduction

This article is meant to fill in the vacancy and unclearness on the previous articles concerning the role of local thalassocracies in the history of Southeast Asia in relation to the expansion of international maritime trade between India and China in the Southeast Asian waters during the early centuries AD. Apart from that aspect, this article also focuses on answering the question of connectivity in the international maritime trade which has spurred peoples in Southeast Asia to gain profits and benefit from the booming economy, and in turn, consolidated the contest of seascape among existing political powers. In this case, the perception of seascape has changed from merely ocean areas to the social media which might have an important role in economy, politics, and culture.

Since the Second World War have many scholars conducted historical research on the expansion of maritime trade between India and China in Southeast Asia. Most of those classic studies emphasize the personal roles of individuals from India and China in the international trade via Southeast Asia. It can be observed well in the work of Coedes (first published in 1910), Majumdar (1927), Krom (1926), and Berg (1929). It described in those works that the emergence of Southeast Asia in international maritime trade could not be separated from the central role of Indian Traders’ expansion to the East in the early centuries AD.

Coedes uses the concept of Indianization for describing the process of peaceful propagation of the Indian culture to Southeast Asia. This concept describes the central role of India in the peoples of South East Asia (Coedes, 1975). By investigating the history of Southeast Asia he exposes a dominance role of the Indian culture in many parts of this region. During the course of indianization process the “Sanskrit-culture” including the Indian conception of state, Indian concepts of kingship, the denominations and philosophical teachings of India, the cosmology and mythology of Purânas and the great epics, Hindu or Buddhist cults etc. were spread out to Southeast Asia by using Sanskrit as important medium of communication (Lukas, 2001). The peak of Indian influence is marked by the emergence of Indianized states adopting the model of Indian government administration, culture, and conceptual basis and even symbols. In this context, Coedes emphasizes the important role of colonialization by the Indian priests in the Indianizing process in Southeast Asia (Coedes, 1975). Meanwhile, Majumdar focuses on the colonialization by Indians in Southeast Asia which was not done by the Brahmana but by the Ksatria (soldiers) through Indian conquer (Majumdar, 1927). The same theory is supported by C. C. Berg, who argues that the process of Indianization was a result of conquering and the colonialization of Indian troops in Southeast Asia. Krom has interesting opinion stating that the process of Indianization was the result of the expansion made by Indian traders and the trade colonialization enabled them to marry the local women. Through this process, the Indian culture became dominant among the peoples of Southeast Asia (Majumdar, 1927).

Various opinions have focused on the influence of Indian culture in the construction of Southeast Asian culture that has become trending topics nowadays. Such opinions also presented by some scholars emphasizing more on the roles of the peoples and local culture in the development of civilization in Southeast Asia. Some of the substantially representative examples to be mentioned here are those opinions suggested van Leur (1983) and Bosch (1961) and the young historians, such as Wolters (1967) and Hall (2011). Van Leur analyses that by judging the cultures in the palaces of Southeast Asia, it must have been the result of the activities of the priests (Brahmanas) from India, who were well-educated and highly competent in the culture, art, and religion (Majumdar, 1927). They were asked by local rulers to strengthen their legitimation and authority in line with the grand economic achievement that they acquired following the international trade in their region. The government was based on the concept of the cult of god-king which in turn consolidated and expanded the local political powers. Thereby, the local interest was of significant roles in the process of cultural absorption from India to South East Asia. According to van Leur, the Indian culture was merely the surface; the local cultures were the substantial components (Legge, 2008).

In the first stage, the introduction of Indian culture to South East Asia occurred via the trade media. In the following steps, the local rulers of South East Asia who had been prosperous invited the priests/Brahmana for transmitting religions and cultures from India. In the next period, there was a kind of back-flows of young priests from Southeast Asia to be educated in India and who later developed the Indian religions and cultures in their home region (Legge, 1976). Wolters described these local responses and initiative towards the arrivals and presence of foreign traders in Southeast Asia maritime region. They were able to take these opportunities provided by the global economic growth to nurture their best interest (Wolters, 1967).

Of the various growing opinions, Hall concludes that the early contact of the rulers in Southeast Asian and Indian culture seems rooted in the interest of the local rulers to benefit from the arrivals of Indians, not only in terms of economy but also in terms of religious rituals, administration, and technology to fight against local competitors. By adopting and adapting the Indian culture, could these rulers take the vital roles in the international trade between India and China so that they were able to gain tremendous economic advantages.

This article is more focused on the effort to reconstruct the roles of the local peoples of Southeast Asian within the context of Sino-Indian trade expansion during the early period of pre-modern ages when the seascape contest was taking its role in Southeast Asia. For this reason, this article will prove that the expansion of Sino-Indian trade in Southeast Asia on the one hand has caused widespread Indian cultural influences (Hinduism and Buddhism) in this region, but on the other hand the economic benefits generated by these international trade activities have produced polarization and centrifugal movements in politics. The birth and development of the centers of political power in Southeast Asia were closely related to efforts for controlling economic resources that were increasingly developing in line with the expansion of the Sino-Indian trade. Competition and conflict occurred between centers of political power. Because the sea as a social space was a vital medium in economic activities in the archipelago, it became a contesting arena among emerging kingdoms in the Southeast Asian maritime region. For those reasons, this research addresses a number of issues, including the process of constructing seascape in the Southeast Asian maritime region, the diaspora of the people in Southeast Asia which resulted in a conflict-prone politics based on ethnicity, and a number of seascape competition and conflicts in Southeast Asian maritime region during the pre-modern period.

II. Seascape Construction, Ethnic Formation, and Conflicts

This section narrates the physical maritime region of Southeast Asia as part of the inevitable historical process. As widely known, that Southeast Asia can be divided into two parts; the mainland and the islands or maritime region. At present, the mainland Southeast Asia includes Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, which forms a part of Asia as a continent. The Southeast Asia islands or maritime region (Islands of Southeast Asia or maritime Southeast Asia) include Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, Brunei, and East Timor (Watson, 1997).

The study of seascape and landscape in the archipelago has developed quite rapidly, especially in Europe over the last few decades. These studies concerned the study of substance and theory about spatial arrangements regarding seascape, islands, and archipelago. This kind of study is seen as unique because historically in this kind of area there have been various isolated communities of living things (plants, animals and humans). In various levels they are separated from the mainland community or even separated from other islands. Initially, the concept of seascape means a picture or view to the sea, or a view of an expanse of sea. During the course of time this concept has been broadened to mean the coastal landscape and adjoining areas of open water, including views from land to sea, from sea to land and along the coastline. Seascape refers to the relationship between land and sea which includes marine components, coastlines and land. But now seascape research has also included the fields of maritime history and underwater archeology (Pungetti, 2012; Tapper and Johns, 2008).

Studies of seascape and archipelagos have also grown tremendously in some parts of the world. Sulistiyono has studied the dynamics of the relationship between the inland cultures and the maritime culture in the Indonesian archipelago. Interestingly, this archipelago has not only a maritime culture but also agricultural and feudalistic culture inland. Therefore, there have been latent contests between the maritime and agricultural cultures along the path of history (Sulistiyono and Rochwulaningsih, 2013). Sulistiyono also studied how the Dutch colonial powers at the end of the 19th century had arranged sea and island spatial arrangements to integrate their colonies in the Indonesian archipelago through the reconstruction of trade routes, ports and production areas which were all aimed at exploiting the colony and to face competition with other colonialists, especially England (Sulistiyono, 2003).

An interesting article was written by Hong Seok-Joon, who studies the concept of Zomia in his social study in the territory of Malaysia, with focuses on the main port cities of Malaysia, including the port city of Malacca. Here the concept of Zomia refers to the non-state’ space, which was characterized by the presence of migrant zones and other “escaping people” from the agricultural world/countries which have now been erased by international cooperation. So, the focus of the analysis of this article is and was done by the historical approach, when any state did not fully control the region/seascape. The region was able to provide a social space for the dynamics of the cultural relation of the ethnics, international relationship, and inter-religious relationships in the surrounding areas (Hong, 2016).

In line with globalization, islands, especially small ones, have been attractive for tourism and desired by some communities. Baldacchino conducts a study on the attraction of these islands related to the powers (political states) in the spatial analysis. This study refers to the post-structuralist to put forward the “attraction of the islands” by separating and dismantling the inter-related components of the “islands.” These components were borrowed and adapted from the spatial analysis on powers and the relationship of powers written by Henri Lefebvre on the production of space. In his work entitled The Production of Space, Lefebvre argues that area is a social product; social construction and complex ideologies, based on the values and social production meaning which influence on spatial practices and perception. In his ontological approach, this work offers different criticisms to the representation and life of the islands (Baldacchino, 2012).

Various studies on small islands have also arisen in many parts of the world including the work of Kuwahara (2012). He discussed how the Japanese government which has around 7,000 islands is trying to create equity in development on remote islands by taking case studies of Amami and Okinawa islands. For this reason the Japanese government issued the Remote Islands Development Act. The aim is to eliminate "backwardness" by giving a lot of the state budget for remote island development. In addition to highlighting the historical background of remote islands, he also described the changing role and meaning of the law.

Geographic construction of the islands of Southeast Asia is an interesting study of seascape. Although the basis of geological structure of islands of Southeast Asia has been formed over millions of years ago, in fact the shape and appearance of the islands in Southeast Asia today are relatively new phenomena. This is related to successive changes between glacial and interglacial period when sea levels change alternately with changes in the earth's unstable climate. Dramatic changes to the coastline occurred at the end of the interglacial period which peaked around 7,500 years ago when the sea level rose again and sank the Sunda and Sahul plains lowlands which gave rise to islands of Southeast Asia more or less as it is today. (Oppenheimer, 2012).

The geological formation has made around 80% of the Southeast Asian region are a maritime area. It has become the primary source of the region to participate in the international trade which began to proliferate in the early centuries AD. The richness of minerals as a result of the geological process has also supported the role of this region in the international trade. According to geologists, this region contains gold and copper deposits and other metals as found in Aceh, Sumatra-Meratus, Sunda-Banda, Central Kalimantan, Celebes, East Mindanao, Central Halmahera, and West Papua (van Leeuwen, 2014).

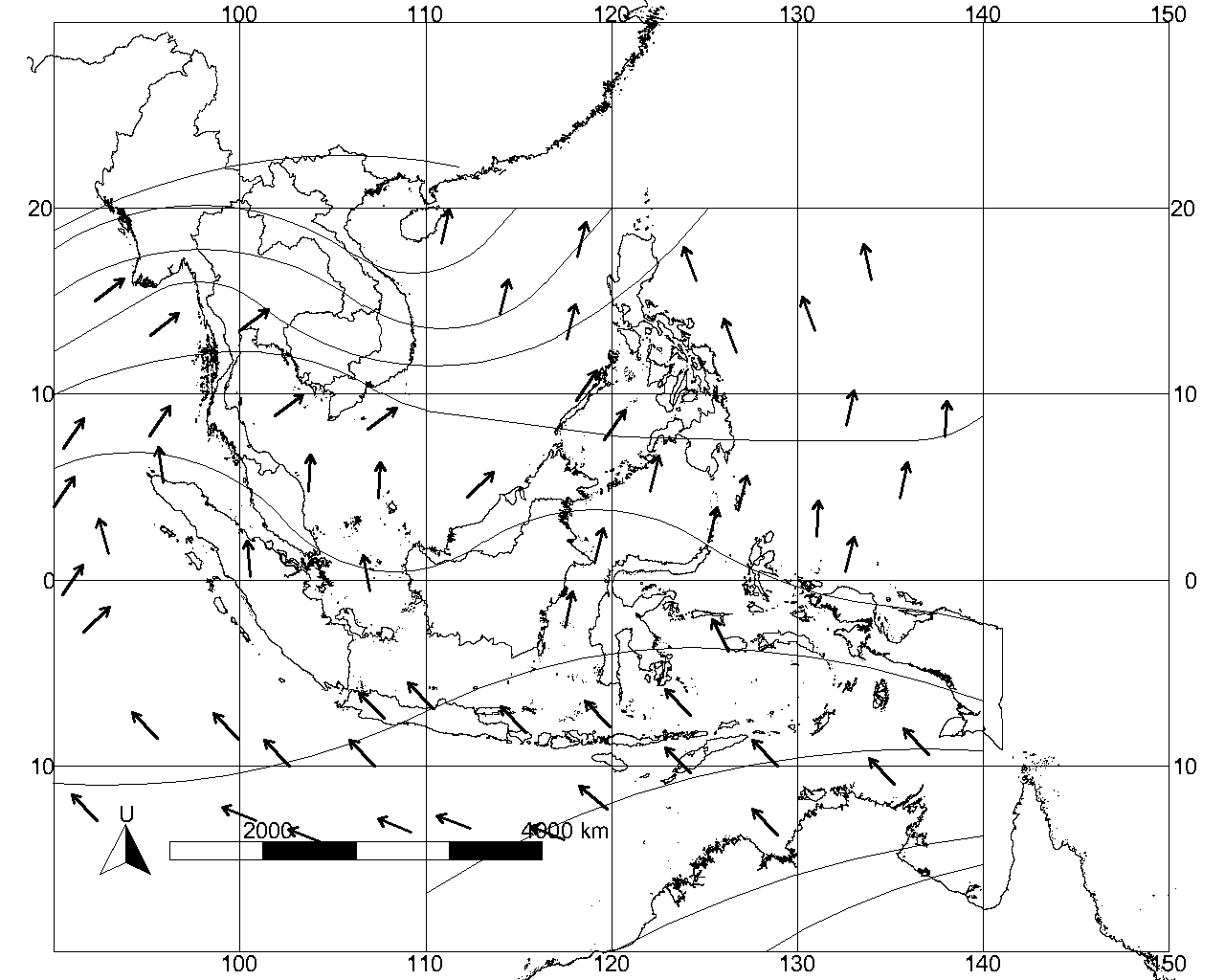

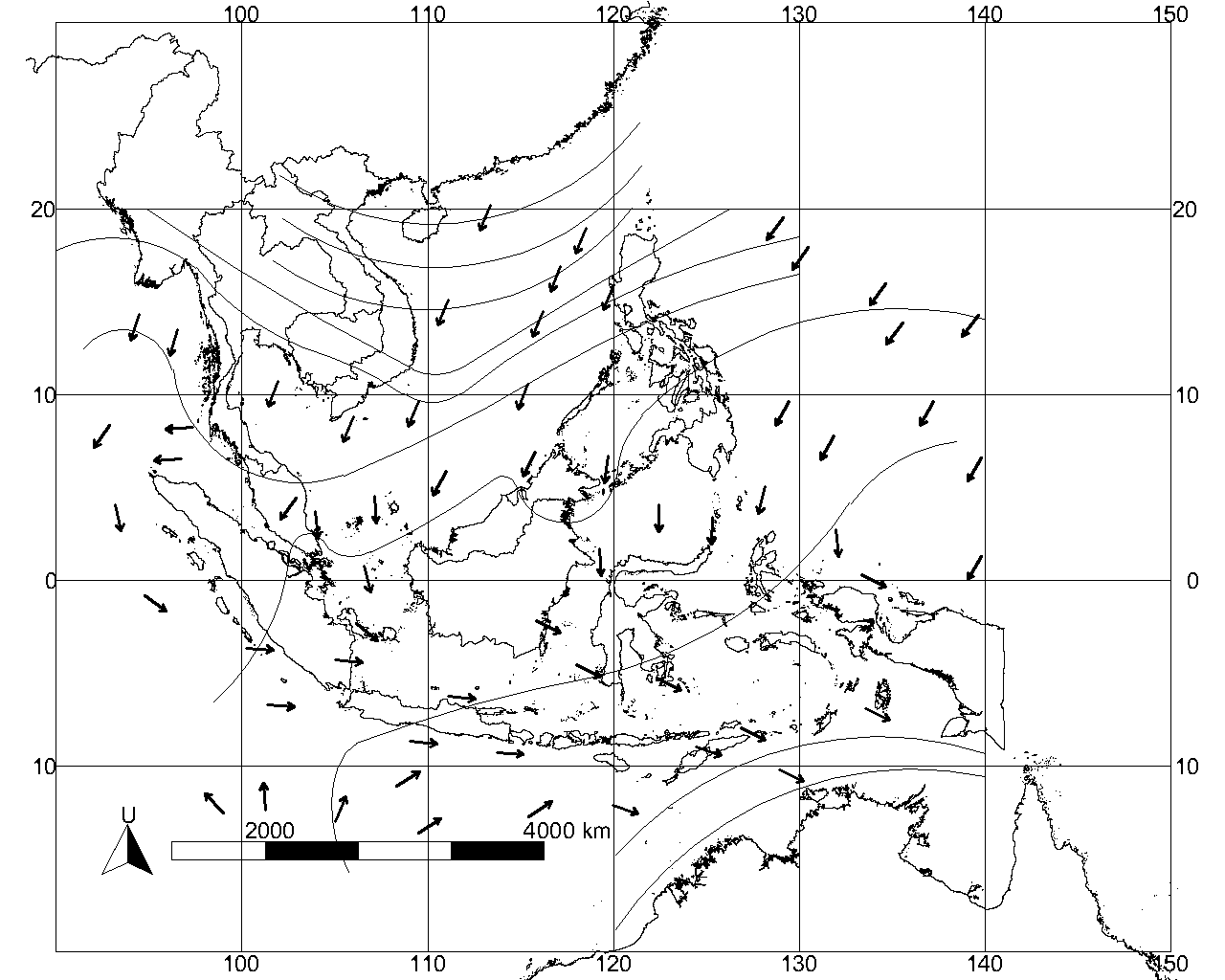

Apart from the geological factors, the geographical factors have also dominantly influenced the development of the various communities inhabiting the archipelagos or the maritime region of Southeast Asia. The geographic location has a significant influence on the climate and in turn becomes a significant factor affecting the history and culture of the communities dwelling in the region. The combination of the astronomic location in the equator and the geographical location between two continents have made this region tropical with the unique monsoon winds that enable inter-island and inter continent sailing (Marine, 1912; Stibbe, 1921). The volcanic activities have also made this region extremely fertile for agriculture, plantation, and forestry. Pepper is widely produced in Aceh, Jambi, Lampung, Banten, and Kalimantan Selatan. Cloves are mainly produced Ternate, Tidore, and Ambon. Nutmegs are produced in Banda, and the Nusa Tenggara islands produce the sandalwood (Kayu Cendana). Many different forestry products are produced in almost every part of the Southeast Asian archipelagos. The monsoon regularly changes its directions, and this has made it possible for human mobility to be carried out about social, cultural, political and economic movements. Figure 1 shows the detail of regular monsoon in Southeast Asia. It is no wonder that this region had become the destinations of migration of different races and ethnic groups since ancient times.

Around 1.3 million years ago, the Homo Pithecus migrated to this region, from Africa and they spread all over the world, including Southeast Asia. Beginning about 120,000 years ago, migrations out of Africa were made by the homo sapiens. They followed the coastline from Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia and to the eastern tip of the Sunda land. They could even cross to the region of Wallace, namely Flores, which was separated by the sea. They originated from the Australia-Melanesian sub-races (Bellwod, 2000). Evidence of their presence can be traced in Wajak, Tulung Agung, East Java, Sarawak and Tabon (Palawan). They developed the Mesolithic (Hoabinhian) culture originating from Hoa Binh, Vietnam (Keates and Pasveer, 2004). This culture has spread out to the entire parts of the Sunda land, and they event used bamboo rafts to cross the sea to Sahul land (Bednarik, 2015; Irwin, 1992:44). They were the ancestors of the natives in Papua and Australia and on the surrounding islands (Gomes et al., 2015).

Archaeological evidence of the seafaring by the Australo-Melanesian sub-race in the Wallace and Sahul regions can be found in the murals of cave walls depicting people on boats can be located in Muna island, Southeast Celebes (Sulawesi Tenggara), and South Celebes (Sulawesi Selatan), the Maluku and Papua (Arifin and Delanghe, 2004). The boats illustrated on the murals found in the caves were not just bamboo rafts, some of the already take the form of dugout canoes (Figure 2). The boats were even equipped with simple oars and sails as their motors.

In addition to the technological achievement in using bamboo rafts, dugout canoes, oars, sails and outriggers seemed to flourish, and they had introduced Astronomy. It can be seen in the illustration of celestial objects or bodies depicted on the cave walls alongside the river Tala (Seram Island in the Maluku) (Salhuteru, 2010)and in a few caves in West Papua, such as Sosorraweru (Figure 3) and Ili Kere Kere caves. There was the possibility that they were able to benefit from the movements of celestial objects for sailing navigation and, possibly for their economic interests for their survival (Arifin and Delanghe, 2004).

The descendants of the Australo-Melanesian sub-race in the western Southeast Asian region were involved in inter-marriages with the newcomers and their offspring, Austro-Asiatic and Austronesia sub-races. These two races were the variants of the Mongoloid Race (Anderson, 1990). Austro-Asiatic people were believed to have originated from the Indo-China region, with languages spoken by the mainland Asia like the Mon-Khmer and Munda. They migrated to the islands of Southeast Asia via ‘the west route,’ through the Malaysian cape, Sumatra, Java, and Borneo/ Kalimantan. They brought the Neolithic culture (Abdullah and Paeni, 2015).

New waves of migrants of the Austronesian-speaking peoples entered the region. These peoples might have been another Mongoloid sub-race inhabiting Taiwan (Formosa) (Bellwood, 2004; Blust, 1984). Through the Philippines, they continued their journeys to the Celebes, Java, Sumatra, Borneo and up to the Malaysian cape. Some of them stayed in mainland Southeast Asia and became the ancestors of the Champ, a small minority inhabiting southern Vietnam. In the later period, the Austronesians also spread to Madagascar island. The migration waves of the Austronesians to the east raced as far as Fiji and Tonga approximately in 1500 BC and moving into the Pacific to inhabit the Polynesian islands, covering an area stretching as far as New Zealand and Hawaii (Cribb, 2001).

This unique demographical history has made islands of Southeast Asia as a single region. Collins has conducted a study by adopting the case of Indonesia, as the most magnificent archipelago in Southeast Asia. He explains that in Indonesian territory alone there are approximately 706 dialects. It means that Indonesia has about 10 percent of the world’s languages totaling around 7,106 (Blum, 2001). The plurality of the cultures becomes the primary and essential factor for the competition and conflicts in many fields, including the politics. Such dynamics have conditioned that more ethnic groups of specific origin have lost their identity and mingled into the more dominant ethnic groups (Andaya, 2008).

III. Contesting the Seascape and the Southeast Asian Capital

This part discusses the roles of the maritime Southeast Asian peoples in the expansion of the Sino-Indian trade in the early centuries. Further, this section also deals with the development of international trade which has supported the changes in the perspective of social space of landscape and seascape, leading to the contests among the existing ethnic-based political units (Lukas, 2001). Before the growth of Chinese maritime trade, contests for the social space among the current political groups were usually based on the living space in the form of dwellings and agricultural land or a hunting area. After the entry into the international trade between China and India, the contests for living space turned to the contest for maritime living space. The seascape as a social space has converted into a highly contested property. For the limited historical records, the changes in perspective and the consequences of the emergence of seascape contests can be interpreted from different historical phenomena narrating the maritime competitions and conflicts in Southeast Asian History.

A. Southeast Asian Capital

1. Strategic Location

The maritime region of Southeast Asia had extraordinary potentials in the maritime trade between China and India, which reached the world’s large trade before the first centuries AD. The potentials include the geographical capital, natural resources, and human resources. Geographically, Southeast Asia is a part of Continental Asia’s sub-region. On the north, it shares borders with East Asia, on the west with South Asia and Bengal Bay and the east with Oceania and the Pacific, on the South, it also shares borders with Australia and the Indian Ocean.

Geographically, Southeast Asia can be divided into mainland Southeast Asia and islands or maritime Southeast Asia. The mainland Southeast Asia is presently consisting of Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, and West Malaysia. Meanwhile islands Southeast Asia or the Malay Archipelago, consisting of Indonesia, Eastern Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines, East Timor, Brunei, Christmas Island, Andaman and Nicobar archipelagos in India, and Cocos Islands (Keeling). This region covers an area of 4.5 million km2, comprising 10.5% of Asia or 3% from the Earth’s total land mass. Its population surpasses 641 million, or approximately 8.5% of the world’s population. It is the third most populated geographical region after South Asia and East Asia.

The geographical location of Southeast Asia is very strategic regarding economy, politics, and culture. This region is the crossing or meeting point of two continents (Asia and Australia) and another two oceans, the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. From the maritime perspective, Southeast Asia surrounded by three vast waters which were vital in the world history, the Indian Ocean, Bengal Bay on the west and the South China Sea on the north and the Pacific Ocean on the east. This strategic geographical position has placed Southeast Asia as the vital entrance in the ancient connections of economic, political and cultural centers, India and China. This strategic position is supported by the monsoon winds that enabled the peoples inhabiting the region to take an essential part of the world’ history.

2. Productive Region

It is undeniable that Southeast Asia has been widely known as a very prosperous area. For the limited written documents, information of their natural resources and the great achievement in maritime trade has been provided by external sources. They called this region the Golden Chersonese, the “Land of Gold”. Apart from that, this region also produces spices, especially pepper, and some forestry products such as the aromatic woods and resin and other products (Wheatley, 1961). These products were not only required by India and the countries situated on its west but also by China.

Knowledge of the golden country has been written by Roman Geographer Ptolemy in the midst of the second century, dubbing the area Yavadvipa and ‘‘the Golden Peninsula,’’ to describe the countries outside India (Hall, 2011). It is not an exaggeration that the Roman geographical knowledge was widely known by the traders from India as there was a close relationship between India and Greece via the aggression of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC (Ray, 2003). Apart from the gold, Southeast Asian archipelago produced agricultural, forestry and plantation products significantly needed by the international world.

3. Human Resources: the Role of Local Agents

The attractive question is: where did the Indians, Greeks, and Romans find out the richness of Eastern Countries. It was duly reasonable that the Malayo-Austronesian inhabiting the region of Southeast Asia did some business activities and journeys, first to India and on to the countries located west of it, up to Madagascar and the eastern coast of Africa. This journey was not merely for migration but later used for maritime trade purposes. The dispersal of the prestigious cultural products, such as decorated gems, pottery, and products made of copper, iron, gold and various spices (especially cinnamon) was the evidence of the maritime trade growth, using the outrigger boats conducted by the Malay trader and sailors.

The Malay merchants expanded their trade from Indian waters up to Africa. One of the products they first traded was cinnamon produced in the Vijaya (Bind Dinh) region and gold mined in the Amarawat region in Vietnam (Hall, 2011). These products were needed in India. Malay supplied cinnamon to India. Cinnamon was a product not only was necessary by India but was also exported, along with Malabar pepper, to Mesopotamia and Mediterranean. The sailors of Southeast Asia were likely built early contacts between Southeast Asia and India at least around the second century BC (Hall, 2011). From the connection and communication between the Indian traders and Malay traders, different information on the richness of the East Country was heard by the Indians, a country producing gold and spices. Thereby, Southeast Asia was not only a region producing items needed by the international trade, but it also had human resources to roam the oceans, as sailors, craftsmen, and leading farmers.

Coedes states that one of the motivating factors to expand by the Indian sailors to the “east world” in the early centuries AD was associated with the Indian market’s loss of gold source from Siberia brought via the silk route. Further Caesar Vespasian of Rome (69-79 AD) also enacted inhibition of gold coin export in bulk outside the country. Consequently, the Indians had to find gold sources in the east, the information of which was obtained from the Malay sailors sailing to India and as far as the eastern coast of Africa. The report was so abundant that it creates a fantasy of ‘golden country’ in Southeast Asia (Coedes, 1975; Tripati, 2017). The opinion of Coedes widely followed by other leading researchers like Hall (1955), Wheatley (1983), Ray (1994), Sen (2003), and Chauduri (1985).

It must have been normal that the Indian traders later tried to expand their maritime trade to the east. It is true that the island of Sumatra, which was also known as Swarnadwipa, produced gold, especially in the inland Jambi (Malay) and Palembang (Srivijaya). Gold also found in southern regions of Vietnam. Apart from gold, Sumatra and other islands in the Indonesian Archipelago (Nusantara) produced other tropical products which were also required by international trade, such as honey, sandalwood, camphor, cloves, pepper, nutmegs and others (Gupta, 1987). Cinnamon was also found in the coastal areas of the South China Sea (Hall, 2011).

In the 2nd century AD, the trade relation between Southeast Asia and India was relatively intensive and so in the 5th century AD. During the period, the influence of international trade had penetrated into social, cultural and religious life of the inhabitants of this region. It can be evidenced by the increasing influence of Hindu and Buddhism (Coedes, 1968). It is understandable that during those centuries, some kingdoms showing external influences (especially India) emerged, such as the Funan Kingdom in present-day Vietnam, Kutai in East Kalimantan, Taruma in West Java, and Kantholi in Sumatra (Hall, 2011). Therefore, in around 5th century AD, trade activities had created influence in the social, cultural and political aspects. It indicates that the trade activities became the driving force for the development of Southeast Asian peoples.

In the meantime, the trade relation of Southeast Asian Islands and China was rather slow. Chinese court recorded more information that the sailors and vessels from Southeast Asia came to China. They were Malay-Austronesia (Kunlun) sailors carrying the typical Malay ships (Kunlunpo) attracted the Chinese (Hall, 2011; Wolters, 1967). China’s concern on Southeast Asian Archipelago, also known as (Nan Yang) was slightly slow (Bentley, 1993). Traditionally, China was more interested in developing its trade with regions located to the west (Central Asia, West Asia, and Europe) via the overland route, it then referred to by scholars as the silk road. China’s attention to the Southeast Asian maritime trade was lacking. They had a relationship with Southeast Asia (particularly with Funan) only when it was related to the trade of West Asia and to secure the territory that it had controlled, Vietnam (Wolters, 1967). So the knowledge of the “South World” or more precisely the south sea world was lacking compared to their knowledge on ‘West World.’ Only after the 5th century and later period did they had enough experience of the south sea world (Groeneveldt, 1960). No Chinese ships regularly sailed to Southeast Asia until the eleventh century. The Persian ships had not reached eastern destinations beyond Ceylon (Sri Lanka) until the 6th century (Hall, 2011).

It was not the Indian or Chinese sailors that first connected the Sino-Indian international trade, but the Malay-Austronesia sailors did. They were able to develop the system of international maritime trade connecting South Asia and East Asia from the Southeast Asian-scale trade for centuries before the AD. Funan kingdom, located on the River Mekong, was established, according to Chinese sources, in the first century AD and was the greatest achievement of the sailors of Southeast Asia, as the connecting agents between China and India via the maritime route (Hall, 2011).

In the initial stages, the Indian ships did not reach Malacca Strait, located on the western coast of Malay peninsula. They disembarked the cargo and transported the shipment via the Genting Land to the Siamese Bay. Only after that, the cargo was shipped to Southern China by following the beach line on the side of Mekong Delta and stayed at Funan port, then the port of Linyi and on to the Red River Delta in northern Vietnam controlled by China, from the early centuries AD up to 10th century AD (Hall, 2011). In addition to the strategic position, with abundant and productive natural resources, Wade (2009) also notes that external factors in the development of Southeast Asia were the collapse of the Silk Route and the changes in China’s foreign trade policies during the era of Song dynasty and Yuan dynasty. The fight against the international trade and the growth of Islam on the west also became another development factor of Southeast Asia (Wade, 2009).

B. Emergence of Centres of Growth

The growth of the maritime trade route between India and Funan through Kra Isthmus gave a new meaning to the maritime system in Southeast Asia, especially the Indonesian Archipelago which already having commercial roots since the Bronze era. The maritime trade system among the economic centers in the region of the western Java Sea and the system of international trade of the Strait of Melaka and the South China Sea began to grow. Peoples of the islands Southeast Asian were becoming actively involved in the maritime trade route.

The route via the Kra Isthmus had encouraged and supported the emporium in the Malay Peninsula, such as Kedah that emerged in the early second century AD. This emporium came into being since trade between China and India was carried out via the Kra Isthmus. Archeological evidence of Kedah or Kataha found on the valley of Lembah Bujang. In this region, some castles, iron furnace cites and brick monuments dating back to the 2nd century were found. In addition to Kedah, the State of Dan Dan located in Kelantan emerged, and these states sent their emissary to China from 530 until 535. Other states include Lang Ya Xiu (Langkasuka) founded in the 2nd century AD, Dan Sun located in the region of Tenasserim (a Myanmar region), Pan Pan located in Pranburi, Po Li or Brunei, and others (Liji, 2012).

This change in the Southeast Asia maritime trade route had made extraordinary influences. The Southeast Asian waters were regularly passed by sailing ships by the traders from India and the Middle East. This region had become a very prosperous area where foreign vessels stopped periodically. Local products were highly demanded by international market which in turn bringing positive effects to the economy of the hinterland of the islands Southeast Asia. The annual changing directions of the monsoon winds had compelled the foreign traders to stay temporarily at the ports to wait for the change in the course of the wind. It had made such transits to develop the existence of coastal cities. The coastal embryotic towns served business needs by providing accommodation suitable to the sailors and traders, food and beverages, storehouses and markets. The activities also supported the development of a political system to regulate the more complex life. The staying foreign traders had also created communication between the local people and the foreign traders. These external traders-built partnerships with the local people, based on both family ties and ethnicity or even business trust. There was frequent specialization based on ethnicity and family. This situation had enabled the local people to absorb foreign cultures by their interest (Hall, 2011).

The changes in the route via the Malacca Strait, and in particular through the Indonesian islands, had made the international trade more efficient. The traders did not only avoid the exhausting land crossing, but they could also obtain substitutions for the products and new products needed by the markets in China and India. Indonesian Archipelago could produce African items such as incense and myrrh, different products of resin, and a variety of perfume and incense sticks. They did not have to bring the things from Africa, but the Indonesian Islands could supply them. Sumatera produced camphor, incense, and different forestry products, and so did Borneo. The spices from the Indonesian islands could replace the Malabar pepper for the markets in China.

The booming international maritime trade encouraged the emergence and growth of economic centers and, at the same time, political centers in the western part of islands Southeast Asia. The Chinese sources provides some information although such information can be hard to interpret, some of the economic and political centres emerging in the Indonesian Archipelago at that time included, among other things, Barus located on the west coast of Sumatra (Drakard, 1989; Irfan, 1983), Ho-ling on the north coast of Central Java, Mo-ho-Sin in Bangka (McKinnon, 1985), Yeh-po-ti on the tip of South Sumatra (Irfan, 1983), Po-Hwang in North Lampung (Irfan, 1983), Ho-lo-tan, later modified to Taruma kingdom on the northern coast of West Java (Wolters, 1967), etc. In the 5th century, the Chinese Emperor informed that there was Ko-ying kingdom located on the Sunda Strait on the island of Sumatra (Hall, 2011). According to the Chinese sources, there were some other states in Southeast Sumatra although their precise locations are still debatable, K’an-to-li and Tu-po respectively, which emerged before Malay (Melayu) and Srivijaya (Sartono, 1992).

The descriptions above provide clear illustrations of changes. First, the difference related to the encounter of seascape had been used as economic space (and the living space of maritime tribes) and landscape having used as living space and production space. It created living space centers in the forms of cities where the economy grew, and concentrations of political powers developed, and they served as the cultural centers and meeting points between the seascape and landscape. That is why the maritime international expansion in Southeast Asia involving China and India had encouraged the urbanization in the Southeast Asia islands. During its peak, this region was one of the most urbanized areas in the world and most of the cities located on the coast (Frank, 1998).

The emergence and growth of the cities as economic, political and cultural centers in line with the emergence of the new social groups based on their professions: merchants, sailors, business owners, craftsmen, artists, religious leaders, politicians, security officers and so on. They were not merely composed of the local inhabitants but also people coming from different regions and other ethnics of the surrounding islands and some ethnics from Southeast Asia alone and even from the distant countries such as China, India, Arab, Persia, and so on. Consequently, it was quite normal that some of the foreigners were appointed as port masters to administer trade affairs at the ports. The arrivals of those foreign traders meant incomes for the local people being the hosts (Curtin, 2002). These cities had become a sort of sailing knots and international trade. In later periods, the coastal cities of islands Southeast Asia became a kind of melting pot. Various social groups having different backgrounds merged on the coastal cities. Palembang, the capital city of Srivijaya Kingdom was a development hub, bearing urban characteristics (Bronson and Wisseman, 1978; Reid, 1988).

The expansion of China and India in Southeast Asian Islands enabled products that were previously of lower economic or commercial values became higher commercial values, which is in economics referred to as vent for surplus (Kurz, 1992). The reasons for the Indian and Chinese in Southeast Asia were mainly to seek for gold. The Indians in Southeast Asia did not the only seeker for gold, but they also encountered a number of commodities long traded in China and the Middle East and various spices and medicine such as pepper, cinnamon, camphor, and other things produced in islands Southeast Asia. The products finally became export substitutes for the trade between India and China.

C. Contesting the Seascape

The increasing role of islands Southeast Asia in international trade gave rise the emergence of greater thalassocracies around the 7th century, Srivijaya and Melayu (Jambi). One thing that attracts our attention was that the development of international maritime trade in the frontier of Southeast Asia certainly had caused some changes in the utilization of seascape as the primary medium of maritime commerce. The sea as a social space became more important as it later possessed profitable economic values and potentials. It does not mean that Southeast Asia was not a developed or civilized region before the expansion of international maritime trade of India and China in the early century AD.1 Thousands of years before, the inhabitants of this region had the traditions of utilizing the sea as a means of exchange, including sailing and trade activities. Therefore, the expansion of the maritime trade between India and China in this region became more attractive to the local communities. As the trade activities provided promising economic advantages, many different political powers were organized to manage and control these maritime trade activities. Indian cultural element was rapidly absorbed by the rulers (political elite) to strengthen their positions internally in front of their communities to face the external competitors. The Chinese sources informed almost all of the country as having adopted the political system and beliefs originating from Indian culture.

Here we can see that the Sino-Indian maritime trade expansion in the islands of Southeast Asia had modified the seascape as a contesting space even further. It was because the international maritime trade had used as the primary exchange. The later development in the international trade had also marked the changes in the view of the previous living space emphasizing the island space or land space to hunt, mix and farm. The inhabitants of islands Southeast Asia who came in waves of migration had created the different ethnic identities. It was only reasonable that the early settlers and the newcomers fought for the living space. On the other hand, they might engage in mutually beneficial cooperation. It was also dependent on the growing interest. At that time, the sea was not yet viewed as an important living space in the life.

The expansion of maritime trade in the Southeast Asia region occurring in the early century AD had supported the shift of view which emphasized more on the seascape as the living space with the more beneficial environment. Through the sea, they could access the benefits of the international trade network and, at the same time, they served as the brokers for the production of local products to be marketed as commodities in the international maritime trade. The emergence of emporiums in Southeast Asia was first related to its strategic location in the maritime trade route between India and China. Therefore, it is reasonably understood that the new emporiums emerging in Southeast Asia were Kedah and Funan. Kedah is and was located in around the Kra Isthmus, and Funan was located between the Kra Isthmus and China. Funan was a transit for Southeast Asia products to be exported to China (Hall, 2011).

After the coastal dwelling centers had evolved under the advancement of sailing and the trade of ‘outside world,’ the ethnic-based local elite tried to organize the economic activities politically. Indian culture, both religions and the political system adopted by the local rulers ‘interest to consolidate the power and strength to continue and perpetuate their power as power had provided extraordinary economic advantages as compared to the previous periods. The chiefdom-based political power was transferred into the kingdom system. The cult of god-king was well implemented to empower the position of a leader or chief in the eye of their followers. At last this power was used to organize the local traders or merchants and the foreign traders, and to improve bargaining of the clan living in the inland regions for supplies of different commodities sold in the international trade. The various products of the region in Southeast Asia islands came from the hinterland, such as gold, pepper, cinnamon, resin, aromatic, etc. The inland areas could be accessed better by the river and the river resulted by the superiority in such areas. The river was a part of the social space contested within the meaning of international maritime trade.

A good example of the contest for the river space can be seen in the history of Taruma kingdom in the western Java. Based on both the Chinese sources and the historical records issued by King Purnavarman, the information shows the early consolidation conducted by the king was achieved through wars, to destroy the palaces of the enemies. It shows that the contests and conquer originated from the inter-tribe and inter-clan competitions within the riverine system of the river Citarum. The rivalry and competitions were meant to build the alliance and the network beneficial to the local rulers (sub-ordinate heads) who were the people entirely faithful and loyal to Purnawarman. The king, on the other side, considered himself as the reincarnation of Vishnu who viewed that the victory and alliance were useful to guarantee the security of the international traders who visited the coastal ports and at the same time to support the local products inland to the emporium under the control of Purnavarman (Hall, 2011).

A different nuance occurred during the era of Funan and Srivijaya. The two kingdoms were established on the grounds of mutual benefits between the ports and the inland region. They needed each other: the hinterland required the ports for their market, the ports depended so much on the inland areas for their supply of commodities and the needs of urban people and the logistics for the ships about to go to the sea. In the case of the countries in Sumatera, the emporium could not entirely repress the people living in the inland areas because of the course natural terrain. Therefore, emporium built a mutual relation (Andaya, 2001). The river was the most important communication and transportation media. But it demanded the development of sailing technology. The technology was indeed not only improved for the river sailing but was also dedicated to ocean sailing. The Srivijaya Kingdom had good vessels to roam the river and international maritime route. The story tells that on his journey to India, I-Tsing travelled on a ship from Srivijaya.

One of the most crucial things that had to be achieved by an emporium for its glory was business networks. Without business networks to other economic centers, an emporium could not obtain the economic benefits. Things became worse if no ships stopped and stayed in the emporium, the state would vanish. It was experienced by Funan in the 5th century AD. It underwent backwardness as the trade route changed when traders from Southeast Asia would directly sail to Canton without stopping in Funan (Hall, 2011). It is understandable that the Southeast Asian emporiums always tried to build networks with international maritime shipping and build other relationship with the other large emporiums. The Koying Kingdom in South Sumatera is said to have good trade relations with Funan in the 3rd century AD. Besides, the kingdom built close relationships with economic centers, China and India (Hall, 2011). For that reason, they had to be able to use the seascape as a vital transportation media for their business interest and to build networks with inland areas, neighboring local and international ports.

We can see the countries emerging in Southeast Asia had tried hard to build relationships with the Chinese Emperor. It was not only connected with the smooth trade with the Chinese tributary trade but also related with the expectation to get political and military protection against their enemies. The more local conflicts occurred, the more they sent representatives and paid homage to China. The delivery represented not only a symbol of freedom on the local scale, but also recognition to the power of China. A country that was under the power or control of another state (subordination) on the local-regional level would not have direct access to send and representative and homage to China. China never directly controlled the islands Southeast Asia countries although they recognized the high power of China, as their protector.

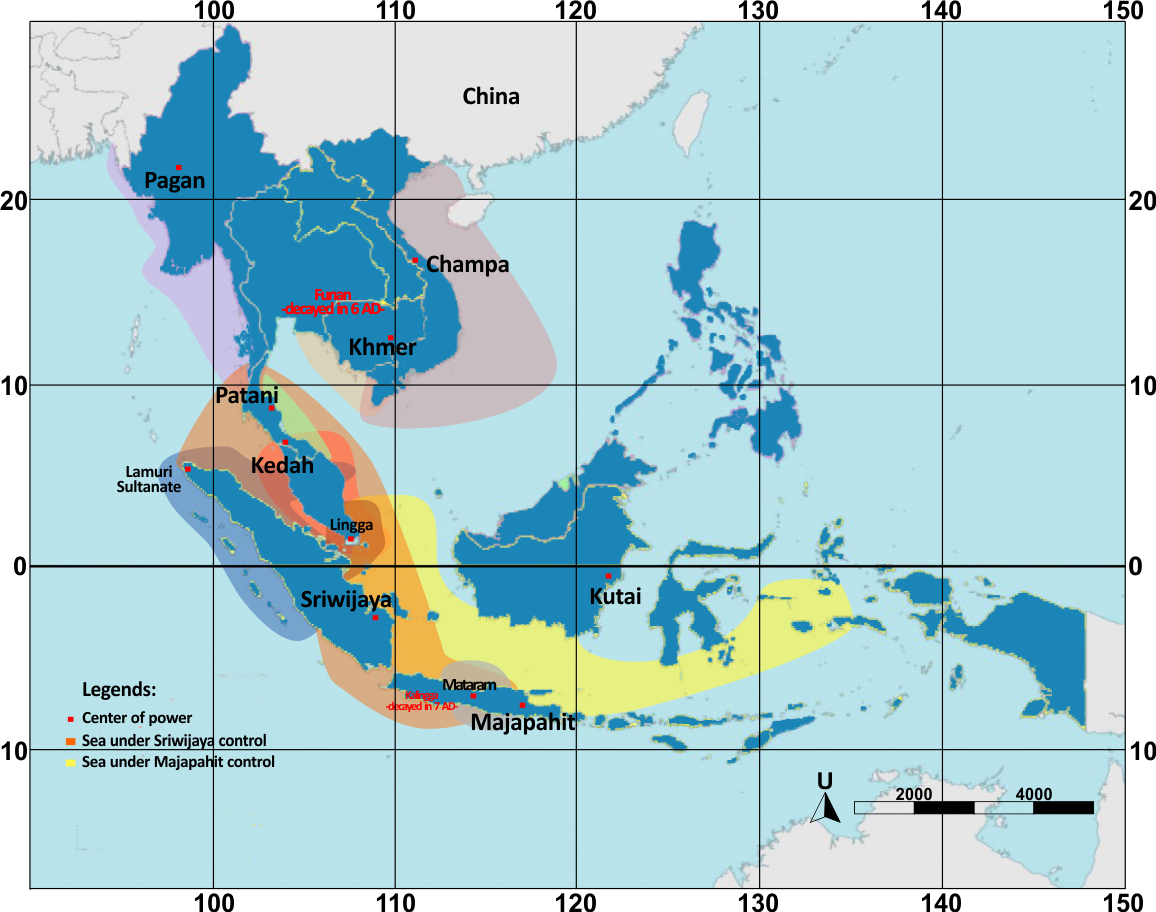

An interesting thing to notice is that the ability of Islands Southeast Asian emporiums to reach their glory was not only determined by its ability to build sailing technology and the control or network with the inner areas or the ports but also determined by its ability to build relationships with other ports. There was a tendency that an ethnic-based emporium, upon being able to consolidate economically, socio-culturally and politically and militarily supported by the great energy (power), would usually conquer the other emporiums, including the riverine system under its control. It can be seen in the conquer series done by the king of Srivijaya, named Sri Jayanasa. The location of the capital city of Srivijaya, Palembang, was not strategic because it was located inland and far from the Strait of Malacca. Figure 3 shows the detail of territorial power in the region during the early modern period. With the power in its possession, Srivijaya tried to seize the seascape being its main economic media. The neighboring regions like Lampung and Bangka were conquered first. These were the producers of commodities and were strategic areas in the Sunda Strait. The next conquer the prosperous and strategic kingdom of Malay (Melayu), located in the traditional trade sailing route India and China. Here, we can see how Srivijaya became an absolute conquering country (Walker, 2004).

Srivijaya later conquered Binanga located on the eastern coast of Sumatera in round 682 AD. More than 20,000 Srivijayan troops were deployed to conquer this strategic region to control the Straits of Malacca and a jumping stone to conquer Kedah in the Malaysian Peninsula. Srivijaya finally conquered Kedah in 685. From Kedah, Srivijaya eventually controlled almost all the southern region of the Malaysian Peninsula and to Ligor (Sitammarat), located in the present day South Thailand. Apart from conquering the seascape zone of the Strait, Srivijaya also tried to seize the Java Sea zone by sending an expedition to Java in 686. Taruma Kingdom in West Java, well known for its riverine system, was finally conquered by Srivijaya. Srivijaya’s conquer continued to Mataram and was able to control Central Java (Irfan, 1983). By a series of these conquers, Srivijaya had won the seascape contest in the Java Sea zone and Strait of Malacca zone which had become the main entrance of the international maritime trade between China and India. Srivijaya became a superpower emporium controlling the seascape of the strategic regions, in perspective of both production and distribution (details of the political centers in Southeast Asia can be seen in Figure 4).

Here we can see that the Srivijaya Kingdom centered on downstream River Musi, was the growing to be a political and military power having absorbed the Indian system. With the young, energetic attitude as a reflection of energy abundance, and based on ethnicity, Srivijaya conquered other emporiums, along with their riverine system. The expedition of Srivijaya’s navy conquered the neighboring emporiums represented a symptom of how the seascape contest was becoming a precious asset within the context of lucrative international maritime trade. These conquer had made Srivijaya the maritime (sea) super kingdom. By controlling the neighboring emporiums and states Srivijaya, which was located downstream, had automatically controlled hinterlands, the riverine tips of each emporium. Conquered countries would certainly lose their control over seascape especially in the context of international trade. Perhaps the conquered emporiums still had a role in building relations with the upstream region, but within the control and subordination of the supra-emporium by giving tribute to Srivijaya.

Srivijaya’s success had been placed and based on its capability of utilizing the existence of the sea, spreading into the region of the Straits of Malacca. The Srivijayans were also the descendants of the Malay-Austronesia race or sub-race who were successfully able to use the sea and seascape as their living space/habitat. They were very mobile, moving from one place to another, from one region of waters to another, seeking marine products to be used for their survival. Here it is clearly seen that the sea has been utilized not only as a production space but also as a medium for shipping and trade which actually provides extraordinary benefits. This also affects the economic life of the community. They not only became collectors of marine products, but also became pirates against traders passing through the Straits of Melaka waters and its vicinity. The existence of pirates in the Straits of Malacca had been reported by the Chinese sources, especially from the trip records of Fa Hien (Wolters, 1967).

Here, the Srivijaya was successfully building relationships with the sea people to keep the seascape secure, as this area was part of Srivijaya’s jurisdiction. Apart from being security agents or protectors, the sea people acted as the pirates for those ships who refused to stop and stay in Srivijaya. These sea people were also used as soldiers by Srivijaya to strengthen its marines. The cooperation between Srivijayan marine and the sea people was a significant power to maintain the security in the Straits of Malacca seascape and the western part of Java Sea zones. Additionally, they were becoming a power that forced the traders to stop and trade at the ports under Srivijaya’s control (Hall, 2011). It means that the control of seascape was the primary key to Srivijaya’s success in consolidating itself as a super emporium in the maritime region of Southeast Asia. It could be done by controlling the ports and the inland areas, cooperating with the sea people, and building its navy to guarantee the security of their emporium.

IV. Concluding Remarks

The study of seascape as a social space using the historical approach shows that space, landscape or seascape, constitutes the result of social construction. In ancient time, when the sea was a forbidden and scary area or a medium for migration, seascape had not become a social space to be contested. When the revolution of international trade route occurred, when people began to use the sea as the media of exchange, the seascape became a significant factor able to generate extraordinary economic advantages. This fact happened in the international trade between China, India, Ancient Near East, and Europe via the Land Silk Route and when it underwent chaos, and the maritime route became very important. Only then did Southeast Asia become more important. The maritime trade in Southeast Asia did not operate among the then countries of Southeast Asia Islands (intra-Asia), but this activity connected China and India. The collapse of the Land Silk Road had encouraged the Indians to use the Malay-Austronesia from Southeast Asia to carry Chinese goods and local products of Southeast Asia; spices, forestry products, and products of mining. For that purpose, they made the region busy with international trade in Southeast Asia. Trade relation between China and India was not only conducted by the people of Southeast Asia, but by the Indians and the Chinese and other nations.

The expansion of Indian traders to the islands Southeast Asia had made the international maritime trade in the region busier. This economic opportunity had urged the local communities to build the political power base to organize the economic activities. Therefore, various thalassocracies were emerging in the islands Southeast Asia. Tribal bases still dominated the emporium/states being established and growing in this period. The cosmopolitan maritime trade made that emporium or state centers heterogeneous regarding the ethnics, races, and cultures. This trade relation had caused the deeper absorbance of Indian Culture by the local peoples of Southeast Asia. The proponents of Indian culture were used by the local rulers to consolidate themselves internally and externally to face their political enemies, the surrounding emporiums.

In the more competitive situation full of inter-state conflicts, the contest for the seascape as a social space was becoming greater. The seascape contested did not only include coastal cities being the center of the emporiums, but also the hinterland as the commodity-producing areas, connected by the riverine system that related upstream and downstream regions as well as the maritime region itself, constituting the media for the traders and sailors to do business. Historically and factually, Srivijaya kingdom located in Southeast Sumatera, with Palembang as its capital city, situated on River Musi, conquered states or emporiums with their riverine system and controlled over the maritime regions of Malacca and the western part of the Java Sea zone. Seascape has become a contested social space in the islands Southeast Asia since the first century AD until present.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a research project entitled ‘Southeast Asian Traders in the Early Modern World: Sources, Maritime Networks and Economic Transformations in the Java Sea Region 1682-1800’ funded by Institute for Research and Community Services [Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat], Diponegoro University.

Endnotes

References

- Abdullah, T., Paeni, M., 2015. Diaspora Melanesia di Nusantara. Directorate of History and Cultural Values, Directorate Gneral of Culture, Ministry of Education and Culture RI, Jakarta.

- Andaya, L., 2008. Leaves of the Same Tree: Trade and Ethnicity in the Straits of Melaka. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu.

- Andaya, L., 2001. The Search for the ‘Origins’ of Melayu. J. Southeast Asian Stud. 32, 315–330.

- Arifin, K., Delanghe, D., 2004. Rock Art in West Papua. UNESCO, Paris.

- Baldacchino, G., 2012. The Lure of the island: A spatial analysis of power relations. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 1, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IMIC.2012.11.003

- Bellwod, P., 2000. Prasejarah Kepulauan Indo-Malaysia. Pustaka Utama, Jakarta.

- Bellwood, P., 2004. The Origins and Dispersals of Agricultural Communities in Southeast Asia, in: Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to History. Routledge, London.

- Bentley, J.H., 1993. Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Berg, C.C., 1929. Hoofdlijnen den Javaanschen Literatuur-Geschiedenis. J. B. Wolters, s-Gravenhage.

- Blum, L.A., 2001. Antirasisme, Multikulturalisme, dan Komunitas Antar-Ras: Tiga Nilai yang Bersifat Mendidik bagi Sebuah Masyarakat Multikultural, in: May, L., Collins-Chobanian, S., Wong, K. (Eds.), Etika Terapan I: Sebuah Pendekatan Multikultural. Tiara Wacana, Yogyakarta.

- Blust, R., 1984. The Austronesian Homeland: A Linguistic Perspective. Asian Perspect. 26, 45–68.

- Bosch, F.D.K., 1961. The Problem of the Hindu Colonisation of Indonesia, in: Selected Studies in Indonesian Archaeology. Martinus Nijhoff, Leiden.

- Bronson, B., Wisseman, J., 1978. Palembang as Srivijaya: The Lateness of Early Cities in Southern Southeast Asia. Asian Perspect. 19.

- Chaudhuri, K.N., 1985. Trade and Civilization in the Indian Ocean: An Economic History from the Rise of Islam to 1750. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Coedes, G., 1975. The Indianized State of Southeast Asia, translated. ed. ANU Press, Canberra.

- Coedes, G., 1968. The Indianised States of Southeast Asia. University of Malaya Press, Kuala Lumpur.

- Cribb, R., 2001. Historical Atlas of Indonesia. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu.

- Curtin, P.D., 2002. Cross-cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Drakard, J., 1989. An Indian Ocean Port: Sources for the Earlier History of Barus. Archipel 37, 53–82. https://doi.org/10.3406/arch.1989.2562

- Frank, A.-G., 1998. ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age. University of California Press, Barkeley, Los Angels, London.

- Gomes, S.M., Bodner, M., Souto, L., Zimmermann, B., Huber, G., Strobl, C., Röck, A.W., Achilli, A., Olivieri, A., Torroni, A., Côrte-Real, F., Parson, W., 2015. Human settlement history between Sunda and Sahul: a focus on East Timor (Timor-Leste) and the Pleistocenic mtDNA diversity. BMC Genomics 16, 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-014-1201-x

- Groeneveldt, W.P., 1960. Historical Notes on Indonesia & Malaya Compiled from Chinese Sources. Bhatara, Jakarta.

- Gupta, A. Das, 1987. The Maritime Trade of Indonesia, 1500-1800, in: Gupta, A. Das, Pearson, M.N. (Eds.), India and the Indian Ocean, 1500-1800. Oxford University Press, Calcutta.

- Hall, D.G.E., 1955. History of South-East Asia. St Martin’s Press, New York.

- Hall, K.R.A., 2011. History of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Trade and Societal Development, 100 – 1500. Rowman & Littlefield, Plymouth.

- Hong, S.-J., 2016. The social formation and cultural identity of Southeast Asian frontier society: Focused on the concept of maritime Zomia as frontier in connection with the ocean and the inland. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 5, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IMIC.2016.05.004

- Irfan, N.K.S., 1983. Kerajaan Sriwijaya. Cambridge University Press, Jakarta.

- Keates, S.G., Pasveer, J., 2004. Notes on the Palaeolithic Find from the Walanae Valley, Southwest Sulawesi, in the Context of the Late Pleistocene of Island Southeast Asia, in: Modern Quaternary Research in Southeast Asia. Taylor and Francis, London.

- Krom, N.J., 1926. Hindoe-Javaansche Geschiedenis. Martinus Nijhoff, s-Gravenhage.

- Kurz, H.D., 1992. Adam Smith on Foregin Trade: A Note on the “Vent-for-Surplus” Argument. Economica 59, 475. https://doi.org/10.2307/2554892

- Kuwahara, S., 2012. The development of small islands in Japan: An historical perspective. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 1, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IMIC.2012.04.004

- Legge, J.D., 2008. The Writing of Southeast Asian History, in: The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Volume One from Early Times to c. 1800. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Legge, J.D., 1976. Southeast Asian History and the Social Sciences, in: Southeast Asian History and Historiography: Essays Presented to D. G. E. Hall. Ithaca-London.

- Liji, L., 2012. Dari Relasi Upeti ke Mitra Strategis: 2000 Tahun Perjalanan Hubungan Tiongkok-Indonesi. Kompas, Jakarta.

- Lukas, H., 2001. Theories of Indianization Exemplified by Selected Case Studies from Indonesia (Insular Southeast Asia) (No. 1), Sudostasien Working Paper. Vienna.

- Majumdar, R.C., 1927. Ancient Indian Colonies in the Far East I. The Punjab Sanskrit, Lahore.

- Marine, M. van, 1912. Afdeeling Hydrographie (1912) Zeemansgids voor den Oost-Indischen Archipel. Muton & Co, s-Gravenhage.

- McKinnon, E.E., 1985. Early Polities in Southern Sumatra: Some Preliminary Observations Based on Archaeological Evidence. Indonesia 40, 1. https://doi.org/10.2307/3350873

- Oppenheimer, S., 2012. Out-of-Africa, the peopling of continents and islands: tracing uniparental gene trees across the map. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 367, 770–84. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0306

- Pungetti, G., 2012. Islands, culture, landscape and seascape. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 1, 51–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IMIC.2012.11.007

- Ray, H.P., 2003. he Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Ray, H.P., 1994. Winds of Change: Buddhism and the Maritime Links of Early South Asi. Oxford University Press, Delhi, New York.

- Reid, A., 1988. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, Vol. I: The lands below the winds. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Salhuteru, M., 2010. Jejak Permukiman Kuno di Kawasan Daerah Aliran Sungai (DAS) Tala. Kapata Arkeol. 6, 101–112. https://doi.org/10.24832/KAPATA.V6I10.134

- Sartono, S., 1992. Kerajaan Melayu Kuno Pra-Sriwijaya di Sumatra. Jambi.

- Sen, T., 2003. Buddhism, Diplomacy and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, 600–1400. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu.

- Stibbe, D.G., 1921. Encyclopedie van Nederlandsch Indië. Martinus Nijhoff, s-Gravenhage.

- Sulistiyono, S.T., 2003. The Java Sea Network: Patterns in the Development of Interregional Shipping and Trade in the Process of National Economic Integration in Indonesia. Leiden University.

- Sulistiyono, S.T., Rochwulaningsih, Y., 2013. Contest for hegemony: The dynamics of inland and maritime cultures relations in the history of Java island, Indonesia. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 2, 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imic.2013.10.002

- Tapper, B., Johns, C., 2008. England’s Historic Seascapes: Historic Seascape Characterisation (HSC). Truro, Cornwall County Council.

- Tripati, S., 2017. Seafaring Archaeology of the East Coast of India and Southeast Asia during the Early Historical Period. Anc. Asia 8. https://doi.org/10.5334/aa.118

- van Bemmelen, 1949. The Geology of Indonesia. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

- van Leeuwen, T., 2014. A Brief History of Mineral Exploration and Mining in Sumatra, in: Proceedings of Sundaland Resources. Palembang.

- van Leur, J.C., 1983. Indonesian Trade and Society, Essays in Asian Social and Economic History. Dordrecht, Amsterdam.

- Wade, G., 2009. An Early Age of Commerce in Southeast Asia, 900–1300 CE. J. Southeast Asian Stud. 40, 221. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022463409000149

- Walker, J.H., 2004. Autonomy, diversity, and dissent: Conceptions of power and sources of action in the Sejarah Melayu (Raffles MS 18). Theory Soc. 33, 213–255. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RYSO.0000023412.88260.c2

- Watson, B.A., 1997. Recreating a vision; Daratan and Kepulauan in historical context. Bijdr. tot taal-, land- en Volkenkd. 153, 483–508. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90003911

- Wheatley, P., 1983. Nagara and Commandery: Origins of the Southeast Asian Urban Traditions. Chicago university Department of Geography, Chicago.

- Wheatley, P., 1961. The Golden Khersonese, Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula before AD 1500. Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Kuala Lumpur.

- Wolters, O.W., 1967. Early Indonesia Commerce: A Study of the Origins of Srivijaya. Cornell University Press, New York.