Study on Vestiges of Japanese in Fishing Village Language

Pukyong National University, Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, Korea minhoyang@pknu.ac.kr

Abstract

Fishing Village Language means the words that contain life and culture of fishing villages. This category covers vocabularies and expressions related to the environment, tradition, economic and cultural activity, and many other factors. This study analyzes Japanese expressions that are seen in the performance data of Fishing Village Language from the East, West, South, and Jeju Sea surrounding southern Korean Peninsula, which has been surveyed by Everyday Korean Language Project Group of National Institute of Korean Language. Based on the verified findings after analysis, I draw implications as follows. First, the recording and preservation of endangered fishing village language are necessary. In particular, the record and conservation of characteristic traits of fishing areas such as the Yellow Sea, East Sea, South Sea, and the Jeju Sea are important. Second, a purification project on Japanese expressions in fishing village language should be introduced. This will be the foundation for good communication to decrease miscommunications with young generations.

Keywords

Everyday Korean Language Project, Fishing Village Language, Language Contact, Vestiges of Japanese

Introduction

This study organizes and analyzes Japanese expressions that are seen in the performance data of Fishing Village Language from the East, West, South, and Jeju Sea surrounding southern Korean Peninsula, which has been surveyed from 2010 to 2012 by Everyday Korean Language Project Group of National Institute of Korean Language. The survey looks closely into fishing village language, Fishing Village Language, from different perspectives. Data and reports released so far are linear analyses and important data have unfortunately been thrown out. For this reason, I investigate language contact seen in fishing village language, focusing on vestiges of Japanese that have survived in Korean, based on released data. The reason why I focus on the vestiges is that Japanese expressions have frequently been used in fishing not in the other fields. Not only which words have permeated Korean fishing village life but also which meanings they have and how pronunciation or meaning has changed by language contact are investigated. In fact, a large scale of field study like this has significant meaning in terms of accumulating cultural heritage of Korean language and recording not only underlying everyday language but commonly used fishing village language. Based on the data, deeper analysis and contemplation would answer the question of language contact and comprehend the mechanism of following language contact accordingly. The main research questions and verification are as follows: There are vocabularies used in fishing villages, which are related to Japanese influenced by language contact. Regarding the language contact, it is necessary to analyze the type and pattern of Japanese expressions in Korean.

Survey Outline

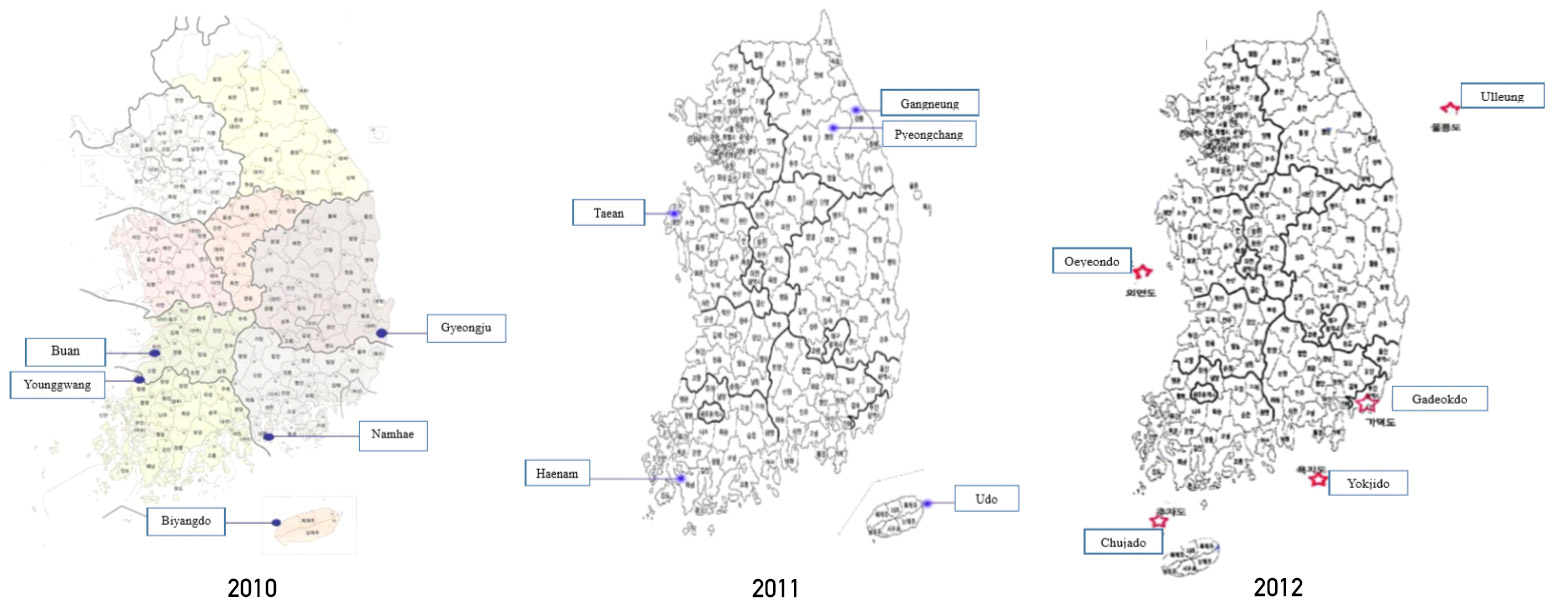

The data used in this study is from Fishing Village Language Project by National Institute of Korean Language; The project looked into twelve regions in four areas as seen in Fig. 1.

| Fishing village language Survey | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|

| The East Sea | Gyeongju | Gangneung, yeongchang | Ulleung |

| The West Sea | Buan, Younggwang | Taean | Oeyeondo |

| The South Sea | Namhae | Haenam | Yokjido, Gadeokdo |

| The Jeju Sea | Biyangdo | Udo | Chujado |

Surveyee

Considering its characteristics, it was difficult for fishing village language Project to strictly apply the surveyee selection standard, NORM: Non-mobile, Older, Rural, Male, which is the typical standard of ethnology or dialectology. Therefore, fishing village language Surveyee selection was conducted in that context; The criteria are as follows. Native person at the age from 50 to 60 in the surveyed region who has lived in the area for more than three generations. In the case of a surveyee over the age of 70, one with poor education; in the case of 50 to 60, one with middle school education is selected.

- Eyesight, hearing, and teeth in good condition

- Regarding oral speech data recording, one with a good speaking ability

Survey Content

Fishing Village Language means the words that contain life and culture of fishing villages. This category covers vocabularies and expressions related to the environment, tradition, economic and cultural activity and many other factors. Recently, the change in the marine ecosystem, rural-urban migration, and the change in economic shape from rapid urbanization of fishing villages have had a huge impact on fishing village language. As a result, words containing traditional culture of fishing village life have died out or been endangered to die out and under the influence of standard language. Therefore, I aim to collect data of basic and essential vocabularies for fishing village life through the survey in depth and detail to organize the data. Based on a questionnaire written to collect vocabularies of fishing village life, which are being lost, survey items are filled in. Items are divided into basic vocabulary and by regional theme; the total number of surveyed vocabularies is 10,919, vocabularies not recorded in Standard Korean Dictionary is 3,380, and vocabularies surveyed by individual theme 2,953.

Basic Vocabulary Item

- Performer

- Environment: Time (Tide, Flux and Reflux, Day), Weather (Wind, Rain, Snow, Sun, Moon, Star, Etc.), Space (Bearing, Sea, Seashore, Terrain)

- Catch of Fish: Fish (Name, Type, State), Shellfish (Name, Type, State), Crab (Name, Type), Marine Plants (Type, State), Etc. (Type, State)

- Fishing Tool and Operation: Net (Name, Type), Fishing (Name, Type), Boat (Name, Type), Other Tools, Fishing Operation (Shellfish, Plants, Net, Boat, Etc.)

- Food: Salted Fish, Others

- Folklore: Ritual (Rite for Boat), Taboo, Proverb, Argot, Song

- Having each individual regional theme set, I aimed to find vocabularies that represent the fishing region.

Individual Theme by Region

- The East Sea: Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do (The process from mending a net to fish market); Gangneung and Pyeongchang, Gangwon-do (From pollack fishing to drying); Ulleung, Gyeongsangbuk-do (From squid fishing to drying)

- The West Sea: Buan, Jeollabuk-do and Younggwang, Jeollanam-do (Salt field); Taean, Chungcheongnam-do (Jayeom: Boiled salt); Oeyeondo, Chungcheongnam-do (Fishing in Oeyeondo)

- The South Sea: Yokjido, Gyeongsangnam-do and Gadeokdo, Busan (Jigging, Mullet fishing)

- The Jeju Sea: Biyangdo (Fishing in Biyangdo); Udo (Ascidians); Chujado (Fishing in Chujado)

Language Contact in Fishing Village Language

It is Sapir and Whorf who are noted scholars who firstly argued the language shapes human thought. Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is a linguistic hypothesis that the way a person comprehends the world and acts in is relevant to the grammatical structure of the language he uses.

For example, time is objective for Europeans and the morning, evening, January, August, summer, and autumn are clearly divided; time is also absolute for them and the division of the past, present, and future is clear. For the Hopi, however, time is not objective but customary and the division of time is not clear. In that sense, they seem to take linguistic relativism position. In other words, the relativity hypothesis holds the idea that “language is thought;” In short, since thought inevitably involves language, the language influences the thought. Looking into fishing village language, it is easy to find out that fishing villagers have been adapting to the terrain, coastal environment, and cultivating related culture as Korea is surrounded by three different seas. In particular, fishery-related Japanese expressions from developed Japan have been brought throughout Japanese colonial era.

The viewpoint to seas was alike and similar thought would be shared. It is a quite interesting point. Follow-up studies should be carried out and dynamic flow of words related to seashore including specialized fishing tools and ship-related terms is notable. Analysis on language contact in fishing village language is as follows.

First, with regard to survey items, I organize vocabularies mentioned as “Japan” or “Japanese” by surveyors and categorize them into types. As a result, a lot of names of fishing tools and operation and catch of fish have been affected by contact of Japanese. For example, most fishing tools and engines of ships used in a challenging fishery environment have been imported from neighboring Japan; many people have been exposed to Japanese. Looking into ecosystems and culture of fishing villages based on expressions related to the village environment and fishery, we can find language contact phenomenon from Japanese. A study like this has hardly been noted but it is considered significantly important to conduct the study for the sake of communication with future generations, cultural understanding of fishing village life, and language purification of marine-related words.

From other aspects, traces of Japanese are easily seen; this represents the fishery environment and culture at that time. In the next section, I will analyze unconsciously-used Japanese expressions among fishing village language by types. This study, however, excludes the name of fish and ascidians to be dealt with separately. Because there are much more vestiges of Japanese regarding names of fish and ascidians, causing the lack of space in this paper, they will be dealt in another paper separately.

Japanese in Simplex

According to the analysis result, there are many borrowings of Japanese expressions. Throughout the colonial era, there are vestiges of Japanese in almost every field in Korea. In many fields except for fishery, however, influence of Japanese has diminished due to the contribution of Korean language Purification by National Institute of Korean Language. On the other hand, there are still many Japanese expressions in the area of fishing village language. Therefore, I proceed with analysis focusing on Japanese in fishing village language, which has hardly had attention. First, I investigate Japanese in simplexes.

Borrowing Pronunciation of Japanese Loanword in fishing village language

This section deals with pronunciation of Japanese loanwords in a simplex. Words in fishing village language that have pronunciation of Japanese loanwords in Korean are as follows.

‘Nairong’ (nylon) is Japanese pronunciation of ‘Naillon;’ it is a word frequently used when speaking of nets and ‘Nora’ stands for the wheel of a boat used to pull a net. According to loanword orthography in Korea, it should be pronounced as ‘Rolleo’ (roller) but fishing villagers pronounce it as ‘Nora.’ One of regional survey items, a word related to salt field, which is a unit to measure salinity of salt water, is pronounced as ‘Bomea’ (Baumé degree) which is from French; it is reasonable to consider it as Japanese loanword pronunciation.

The next case has a form of mixture of Korean and Japanese and it usually uses Japanese loanword. There is ‘Kompas’ (compass) that stands for ‘Nachimban’ and ‘Angka’ (anchor) for ‘Dat.’ The interesting thing is that Japanese expression ‘Angka’ that stands for ‘Dat’ varies from ‘Angka’ to ‘Rangka’ and ‘Engka’ by different regions. It can be called as a language transformation resulted from different dialects by region. ‘Boseun’ (boatswain) and ‘Bosing’ that stand for ‘Gappanjang’ have been spoken as Japanese loanword expressions. ‘Hukkuri’ is from ‘Fukku (hook),’ Japanese loan word, and it is a term for the tip of a net or metal attached to a tip of a fishing tool. Lastly, ‘Gapba’ means a diving suit used in the water; it is a loanword from Japan. Tracing back to the origin, it is from Portuguese ‘capa.’ The original meaning was a cloak shaped raincoat (合羽) and it can be used to mean a good swimmer (河童). Because it has been used for a long time even in Japan, it is hard to recognize if it is a loanword or pure Japanese. It may note that “pure Japanese” does not mean uncontaminated Japanese but general Japanese.

Borrowing of Japanese in fishing village language

There are different Japanese words in fishing village language much more than we may think. First, ‘Senjjo’ (captain) stands for ‘Seonjang’ and the meaning is similar to ‘Gigwanjjo’ to be mentioned in the next section. Simply translated Japanese word has been used to call a captain who navigates a boat or a ship. ‘Aburasasi’ from 油差し is an unfamiliar Japanese expression; it is a term for a tool or a person to lubricate a machine. This expression has broader meaning than the original one. In other words, it came to cover the meaning of a man who assists a captain. The next one is Japanese ‘Tomo’ that stands for Korean ‘Imul;’ which is a term for a prow. A detailed name of plywood on the right side of ‘Tomo’ is called ‘Omokaji.’ This word can indicate a wheel to turn a prow to the right or ‘Uhyeon’ (starboard); it turned out that ‘Omokaji’ has still been used. There is an interesting word. Japanese ‘Ikesu’ (生簀) stands for a place to store a catch of fish as seen in Fig 3. Looking into practical examples, however, Japanese expression ‘Ikesu’ is for a tank with live fish and Korean ‘Eochang’ is for a place with dead fish. Japanese do not prepare a space to store live or dead fish separately; it is a typical example of a word to be divided in meaning after borrowed.

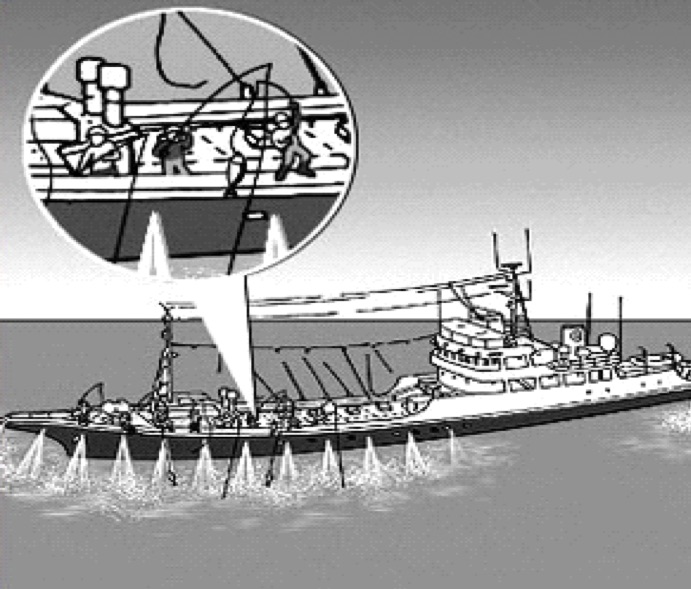

Usage of unfamiliar Japanese is also notable. Among terms used in pollack drying rack field, the upper part of a pollack to be hung is called ‘Ukketori’ (受け取り) which is from Japanese ‘Uketori;’ it is an example transformed from the word ‘Uketoru’ which has the meaning, acceptance, in Japanese. These words form important data that can only be acquired by a practical field study. There is a word ‘Himo’ that indicates the lower part of a net; it is also a Japanese expression. The original pronunciation is ‘Simo’ (下) but it is called ‘Himo’ in Korea; it is a transformation of pronunciation after Japanese is brought to Korea; There are examples similar to this. As seen in Fig. 4, the expression, ‘Chaenakgi,’ used in squid fishing in the East Sea is called ‘Ippondzuri’ (一本釣り) in Japanese. The expression is also used in Korea and there are varietal forms of pronunciation of ‘Ipponsuri,’ ‘Ipponjuri,’ and ‘Iponsuri.’ Dawn is called ‘Asahijji’ in the East Sea and it seems to be a transformation of pronunciation and meaning of Japanese word ‘Asaichi’ that stands for the market held in morning in Japan. Due to the geographical location, there are much more Japanese expressions in the East Sea than the West Sea.

Fishermen would ask where a pollack was caught when talking about a catch of fish. For example, the record that a pollack caught in the region ‘Kusiro’ placed in Hokkaido in Japan is called ‘Gusirokkeo’ is found in oral data. It is also interesting that we can find Japanese word ‘Daburu’ that means ‘duplicate’ in fishing village language. In some sense, the expression ‘Daburu’ is rarely spoken by people not living in fishing villages; considering that ‘Daburi’ has replaced the Korean ‘Jungbok’ in fishing operations, implications of the case are huge.

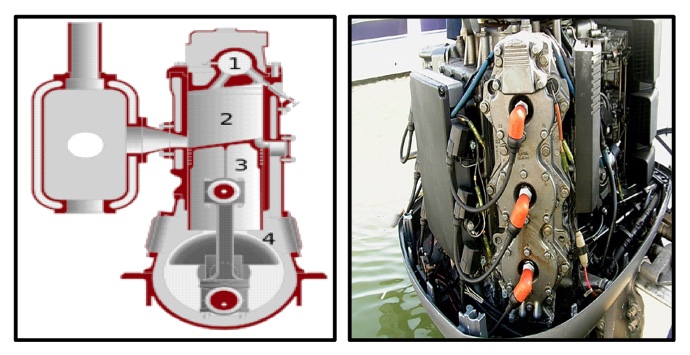

Borrowing Japanese in Specialty in fishing village language

Ship-related terms in fishing village language belong to specialty. Engine is the one of them to use Japanese expressions, which is notable. After World War Two, most engines in ships for fishing in Korea have been made by Japanese ‘YANMAR.’ For the reason, engines in many ships and boats were called ‘Yammaenjin’ and it has become a byword. When speaking of a three cylinder engine, villagers have been using Japanese pronunciation ‘Sankkito,’ 3気筒, in Japanese. In a sense, there are more Japanese expressions in the specialty sector that have been used by fishermen and sailors more than the other fields. There is a similar example of ‘Dataeengine;’ it is a vertical engine usually used in a small boat. This is called Japanese ‘Tate’ meaning vertical, which is also a borrowing. After World War Two, Japanese expressions have been brought to many fields — with no exceptions in the field of fishing tools and related machines. A two-cylinder water-filling ‘Yakidama engine’ is also from Japanese ‘Yakidama.’ As seen in Fig. 5, there is a cylinder head equipped with a ball-shaped combustion chamber made of cast iron where heat in ‘Yakidama’ internal combustion engine ignites. No. 1 in Fig. 5 represents ‘Yakidama’ with a cylinder and an engine at the top and bottom making clattering sound. As above, we found that there are Japanese borrowings in many different sectors in fishing village language.

Borrowing Japanese in Compound

As we have seen the cases of simplex in fishing village language, I aim to investigate borrowing Japanese in compound in this section. In other words, I look into examples of combination in order of Korean and Japanese and the reverse in compounds.

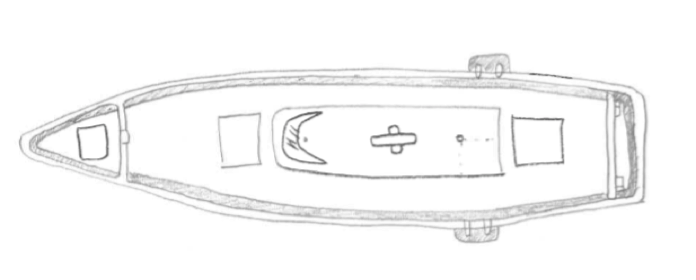

Combination Pattern of Korean and Japanese

Among compounds, the cases of words in order of Korean and Japanese are dealt with. ‘Gigwanjjo’ and ‘Ilbonjo’ are typical examples. A captain of a ship is called ‘Gigwanjang’ in Korean but villagers usually call him ‘Gigwanjjo:’ ‘Gigwan’ is from Korean and ‘jjo’ is from Japanese. A group operating fishery by jigging is called ‘Ilbonjo,’ which corresponds to this pattern. The word is used by combining Korean pronunciation of ‘Ilbon’ with Chinese character ‘jo:’ ‘Ilbon+jo.’ ‘Imul,’ which is one of terms for ship, stands for a prow in Fig. 6; it is called ‘Tomo’ in Japanese. ‘Tomo’ is sometimes solely said but is sometimes used with ‘Imul’ with duplication of meaning. For instance, Korean and Japanese are combined to be ‘ImulTomo.’ There is a quite interesting case where not a word, ‘Gomul,’ which stands for the rearmost part of a ship but a Korean expression ‘Dwi’ is combined with ‘Tomo.’ Technically, Korean ‘Dwi’ and Japanese ‘Tomo’ have opposite meanings; It is reasonable to assume that fishing villagers have made an attempt to facilitate communication by using everyday expressions widely spoken in fishing village life.

Combination Pattern of Japanese and Korean

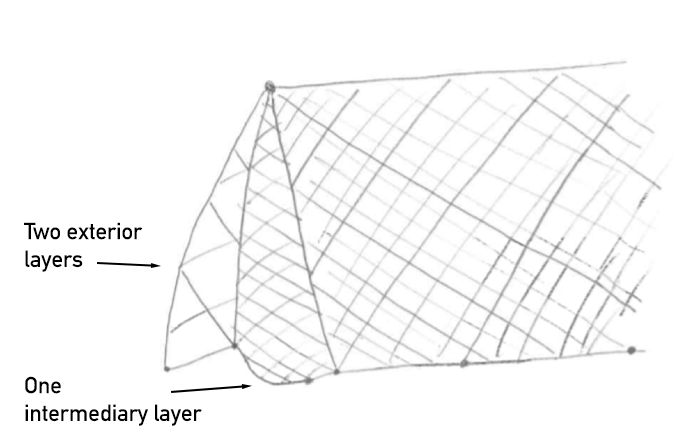

Compounds made up of Japanese and Korean, the reverse of examples above, are as follows. A scoop net, ‘Tteulchae,’ in Korean is called ‘Tama’ in Japanese; the act of scooping is called ‘Damajil,’ combination of ‘Dama’ and ‘jil’ in Korean. There is a similar example, ‘Daraitong,’ which is combination of Japanese ‘Tarai’ (盥) (basin) and Korean ‘tong’ (container). There is a net called ‘Sammai Geumul’ to catch fish by unfolding it, which is one of nets used in a croaker fishing boat. ‘Sammai’ means three layers made up of two exterior layers and one intermediary layer: three in total. It is better in terms of performance in fishing and better at catching shrimps than ‘Jamang,’ a single layered net, and it has larger catching range to be widely used in many regions. Thus, the name of it seems to be a localized Japanese word in Korea. The next compound is ‘Abatjul,’ combination of Japanese ‘Aba’ and Korean ‘jul;’ it helps a net to float in water bound to the guide ropes of a net.

There is ‘Jeonmaseon,’ a small barge, to handle communication between a ship and land or ships or boats. It is usually called ‘Denmaseon.’ There are variants of ‘Tenma’ (伝馬) in pronunciation such as ‘Ttemma’ or ‘Deomma.’ There is a compound, ‘Denmaseon,’ made up of ‘Denma’ and Korean ‘seon.’ However, people hardly realize that the compound is from Japanese and usually assume that it is from the dialect of Gyeongsang-do to indicate a canoe or a raft. For this reason, one would misunderstand that ‘Denma’ is from an original Korean word ‘Ttetmok’ as seen in Fig. 8. It is called folk etymology that the public explain the origin of a word not with historical or linguistic findings but based on accidental similarity of a word form. Many are likely to commit this fallacy with vocabularies including fishing village language. Besides, there are examples of the pattern similar to the above: ‘Dreomtong’ (barrel) to ‘Doramutong,’ ‘Taengk’ (tank) to ‘Tanggo,’ and ‘Waieojul’ (wire string) to ‘Wayajul.’

Conclusion

Korean fishing village language has recently been dying out at a rapid rate. In the circumstance, Everyday Korean Language Project conducted by National Institute of Korean Language was a significant project. Among them, the data containing fishing village language is very important. However, it has rarely been noticed by government institutes or scholars. Given the reality, I observed the phenomenon of language contact and aimed to analyze traces of Japanese in fishing village language in Korea. The findings can be organized in Table 2 below.

| Classification | Content | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese in Simplex | Borrowing Loanword Pronunciation | Japanese Pronunciation | Nairong, Nora, Angka |

| Borrowing Japanese | Japanese Word | Senjjo, Ipponsuri, Daburi | |

| Borrowing Specialty | Ship and Machine | Sankkito, Dataeenjin, Yakidama | |

| Japanese in Compound | Korean + Japanese | Combination of Korean and Japanese | Gigwanjjo, Ilbonjo |

| Japanese + Korean | Combination of Korean and Japanese | Sammai, Denmaseon | |

Although we should use less Japanese expressions for better communication with next generations, investigation on Japanese expressions is necessary to understand the current situation of fishing village language. Based on the verified findings after analysis, I draw implications as follows:

- Record of endangered fishing village language and its preservation

- Purification project on Japanese expressions in fishing village language

- Foundation for good communication to decrease miscommunication with young generations

- Recording and preservation of fishing village language in the East, West, South, and Jeju Sea with regional characteristics

This study leaves much to be desired as follows. Above all, few fishing villages have been investigated; it is necessary to investigate and accumulate data from individual dialect area and entire area of Korea so as to understand the difference by region regarding survey items. Finally, types of fish, a catch of fish, and ascidians not mentioned for lack of space in this paper will be the subject of a follow-up study because looking into the names of fish such as a squid: ‘Ikka’, mackerel: ‘Saba’, and halibut: ‘Karei’ is key to investigation of cultural contact and transformation between Korea and Japan.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017S1A6A3A01079869).

References

- Hong, G., 2013. Study on the Naming Base of Marine Life Words: Focusing on Fishing Villages along the Southern Coast. The Korean Language and Literature, 122, 321-344.

- Kim, J., 2015. Study on the Nomenclature of Naming Wind in Everyday Words used at Fishing Villages. Hanminjok Emunhak, 71, 5-44.

- Kim, J., 2017. A Study of Names Related to Fishery Vocabulary. The Journal of Language & Literature, 69, 55-93.

- Kim, Y., Kim, Y., 2002. Investigation and Research on Japanese Terms used in the Korean Fishing Boats, Journal of Fisheries and Marine Sciences Education 14(1), 79-94.

- Kim, Y., Kim, Y., Kim, J., 2010. Investigation and Research for Japanese Stylish Terms Used in the Korean Fishing Vessels. Journal of Fisheries and Marine Sciences Education, 22(1), 1-10.

- Kim, Y., Park, M., 2012. A Study on Devices of Reducing Foreign Fishermen's Rate of Deserting from Coastal and Offshore Fishing Vessels in Korea. Journal of Fisheries and Marine Sciences Education, 24(2), 263-271.

- Kim, Y., 2012. A Comparative Study on the Foreign Worker's Employment System of Fishing Vessels in Korea and Japan. Journal of Fisheries and Marine Sciences Education, 24(4), 559-573.

- Kim, Y., 2013. Investigation for Purification of Japanese Style Terminology Used in the Korean Fishing Vessels. Journal of Fisheries and Marine Sciences Education, 25(4), 836-847.

- Kowner, R., Daliot-Bul, M., 2008. Japanese: The dialectic relationships between Westerness and Japaneseness as reflected in English loan-words. Globally speaking: motives for adopting English vocabulary in other languages, 250-275.

- Lee, I., 1976. A Socio-linguistics on the Korean fishing village language. The Korean Language and Literature, 72·73, 320-321.

- Loveday, L. J., 1996. Language contact in Japan: A sociolinguistic history. Clarendon Press.

- National Institute of Korean Language. 2010. 2010 Everyday Korean Language Project 1,2,3,4,5. National Institute of Korean Language.

- National Institute of Korean Language. 2011. 2011 Everyday Korean Language Project 1,2,3,4,5. National Institute of Korean Language.

- National Institute of Korean Language. 2012. 2012 Everyday Korean Language Project 1,2,3,4,5. National Institute of Korean Language.

- Park, N., 1989. Language purism in Korea today. The politics of language purism, 54, 113.

- Sa, E. S., 2009. Development of press freedom in South Korea since Japanese colonial rule. Asian Culture and History, 1(2), 3.

- Yang, M., 2008. Sociolinguistic Research on the Usage of Loan-words in Japan, Korean Journal of Japanese Language and Literature, 37, 113-133.

- Yang, M., 2010. A Study on the Use of Loan-words Concerning Shipping in Japanese Dialects: Focus on Southern of Sanriku Area in Japan. Japanese Language Culture, 16, 247-267.