The role of fishing material culture in communities’ sense of place as an added-value in management of coastal areas

East Carolina University, 163 Flanagan, Alumni Lane, East Carolina University, Greenville 27858, USA

University of West Florida, 207 East Main Street, Pensacola, FL 32502, USA

Khakzads11@sturdents.ecu.edu

skhakzad@uwf.edu

Interim Director Institute for Coastal Science and Policy, 205 Flanagan, Alumni Lane, East Carolina University, Greenville 27858, USA Griffithd@ecu.edu

Abstract

Fishing communities in many places around the world are facing significant challenges due to new policies and environmental developments. While it is imperative to ensure sustainability of natural resources, many policies may overlook the contribution of fisheries to the sociocultural well-being of coastal communities. Authors address the problem of valuing the sociocultural benefits of fishing by exploring the role of fishing landscapes and traditional working waterfronts in maintaining sense of place in fishing communities. The paper explores how sense of place contributes to understanding the relationship between fishing and cultural-ecosystem services, drawing on case studies from four U.S. fishing communities in Brunswick County, North Carolina. Through semi-structured and in-depth interviews with fishing communities members, resident photography and sites visits, this paper outlines how fishing contributes to sense of place in terms of place-attachment and cultural-social memory. By understanding the relationship between fishers’ sense of place, and the physical environment in fishing communities in Brunswick County, the authors identify the complexity and interrelated elements that shape the relationship between fishermen and their cultural landscape. The paper suggests that realizing the value of fishing cultural landscape can encourage policies that promote preservation of fishing cultural heritage for the sociocultural benefit of communities.

Keywords

Fishing culture, Fishing communities, Sense of place

Introduction

With boats, fish houses, ship yards, crafts, traditions and other elements related to fishing (Barrett, 1992), commercial fishermen have not only intervened in the natural environment over centuries in the coastal areas, but also have established identity and place attachment. Place attachments are connections to certain physical and social settings that provide different types of social and psychological benefits (Brown et al., 2003). Places are characterized by the physical setting, as well as the range of human activities and social processes that are carried out there (Stedman, 2003).

Fishermen and their material culture are a part of a maritime cultural landscape and traditional working waterfront (Davise, 2001; Inscoe, 2006). These places assist in understanding the culture of fishermen and the meaning of this heritage in fishermen’s everyday life (Ford, 2011; Ransley, 2011). However, due to the changes in the use of resources and land/sea-use regulations and policies (Hoyle et al., 1988), along with development and climate change, fishing towns are in decline; in many places development has taken over and gentrification has occurred (Jepson et al., 2005; Coperthwaite, 2006). The result has been the loss of maritime cultural heritage such as fishing material culture, traditional waterfronts, and maritime cultural landscape. Based on my research, I suggest that maritime cultural heritage is a public good that, if conserved, can slow or prevent the loss of social value and well-being associated with commercial fishing (Duran et al., 2015; Brown, 2004). Wellbeing has several dimensions and attributes such as job stability and satisfaction, identity, sustainability and attachment to place (Altman, 1993; (Hausmann et al., 2015; García-Quijano, et al., 2015).

Some studies argue that fisheries policy does not adequately consider social dimensions of fishing communities (Symes and Phillipson, 2009; Steelman and Wallace, 2001; Symes, 2005; Bradshaw et al., 2001; Pollnac et al., 2006; Worm et al., 2009). Others have highlighted the importance of social and cultural contexts of fishing (Griffith, 1999; Urquhart et al., 2014), suggesting that fishing is not just an occupation (Brookfield et al., 2005; Jacob et al., 2005; Nuttall, 2000; García-Quijano, et al., 2015), but also a highly satisfying way of life that which defines fishers’ identity. Fishing communities can be the site for the creation of deep-rooted place attachments, adding social value to the economic value of fishing (Jentoft, 2000; Marsden and Hines, 2008).

It has been noted that to sustain fishing communities new perspectives and methods are needed that highlight the wide range of cultural and social values that are generated by marine fishing activities (FAO, 2016; Chapin et al., 2012; Colburn and Jepson. 2012; Kofinas and Chapin, 2009; Johnson et al., 2014). This study investigates how place attachment is strongly linked to material cultural and the cultural landscape. There are three major components of place: the physical form, activity, and meaning. Place is a space imbued with meanings (Relph, 1976). This paper reports on the significance of traditional fishing working waterfronts and their material culture for the fishermen in preserving sense of community and place attachment as attribute of social wellbeing in fishing communities for their sustainability. “Cultural significance means aesthetic, historic, scientific, social or spiritual value for past, present or future generations. Cultural significance is embodied in the place itself, its fabric, setting, use, associations, meanings, records, related places and related objects. Places may have a range of values for different individuals or groups.” (Australia ICOMOS, 2000, Article 1.2; ICOMOS – ISCEAH – ICOMOS Ethical Statement”, 2016).

Considering that heritage is “that part of the past which we select in the present for contemporary purposes, be they economic, cultural, political, or social” (Graham, 2002: 17), this research provides an inventory of valuable commercial fishing cultural heritage in the targeted communities, and investigates and explores the value and role of this heritage in the fishing communities place attachment. This Research explores the proposition that fishermen’s sense of place and attachment to their community is influenced by the amount and quality of fishing material culture and built heritage. This study explores the proposition that there is direct correlation between community sense of place and their amount and quality of heritage and traditional working waterfronts preservation.

The justifications for this research are: (1) although it has been acknowledged that achieving sustainable fisheries is feasible through integrating management and policies across biological, social and economic dimensions (FCR, 2000; Forst, 2009), sociocultural values of commercial fishing have mainly been underappreciated in coastal management (Urquhart et al., 2014); (2) several fishing communities are in decline or in danger of becoming extinct due to several natural and anthropogenic causes, which will result in loss of part of the living history and authentic heritage; and (3) by extinction of fishing communities, many related cultural heritage will be abolished and replaced with new urban development, which results in loss of part of human cultural heritage (Jacob and Witman, 2006). Highlighting the values of fishing cultural heritage helps to promote policies to ensure the continued existence of this tradition as well its associated cultural heritage (Act of 2005; Act of 2009).

To preserve the long legacy of commercial fishing and seafood businesses, several studies regarding tangible and intangible fishing heritage have been conducted in the US, along the coast and also in North Carolina (NC Sea Grant, 2007; http://www.wateraccessus.com/cslist.cfm; Griffith and Mirabilio, 2012). However, no formal studies have previously been conducted to assess the sociocultural role of fishing heritage in fishing communities in southeastern North Carolina. Therefore, in recognition of the dramatic collapse of fish and commercial fishing in this area, this paper studies the role of communities’ cultural heritage in place attachment of four existing and active fishing communities in Brunswick County. The communities of Southport, Varnamtown, Holden Beach and Shallotte have been observed and compared with each other in order to evaluate their quantity and quality of fishing cultural heritage, and the role of heritage in preserving sense of place attachment in the members of these fishing communities. Better understanding of fishing cultural heritage in southeastern NC will help demonstrate how the use-values as well as non-use-values of cultural heritage can benefit people and incorporate in communities’ sense of place as an attribute of wellbeing (Potschin and Haines-Young, 2012; Milcu et al., 2013). This study will shed light on cultural heritage as non-market goods (MEA, 2005) and their significant role in people’s life.

The following section reviews the literature on sense of place and explores its contribution to understanding fishing communities.

Background

Fishing heritage and the traditional waterfront

Fishing involves certain human adaptations and behaviors, which necessitates the development of certain cultural characteristics (McGoodwin, 2001). These adaptations require exploiting particular marine ecosystems with whatever technologies a group of people have access to or can develop at a particular time (FAO, 2013). These technologies, the use of the land and sea, and human behavior inevitably create cultural material (Fisheries heritage website; Ome, 2007–8; Malpas, 2008; Crist, 2004; Robertson et al., 2005).

Although fish are often considered as the primary source of livelihood, multiple ecologic-socio-cultural-economic components of this way of life create value out of such factors as sense of place (ICSF, 2011; Acott and Urquhart, 2014), identity, and pride (Felt, 1995; Pollnac, 1988Brookfield et al., 2005; Van Ginkel, 2001; Nuttall, 2000; Tango-Lowy and Robertson, 1999; Claesson et al., 2005). Several studies on fishermen in the coastal areas have demonstrated that tangible and intangible cultural values associated with fishing are of high value for fishermen (Van Ginkel, 2001; Nuttall, 2000; Pinder, 2003; Chan et al., 2012; Acott and Urquhart, 2014; Bradley et al., 2009; EH, 2007). The previous studies showed that there is major public interest in conserving fishing cultural heritage, and fishing communities can and do benefit socially and economically from their cultural heritage (Claesson et al., 2005).

Sense of place and place attachment

In the field of social science, many studies have been conducted on how places are socially constructed, the role of place in identity and how people become attached to place (Low and Altman, 1992; Relph, 1976; Creswell, 2004; Gieseking, 2014). Sense of place covers a range of ideas including place attachment, place identity, place dependence and place meanings (Relph, 1976; Tuan, 1977; Proshansky et al., 1983; Low and Altman, 1992; Creswell, 2004; Farnum et al., 2005; Lawrence, 1990; Kaltenborn, 1998). Place attachment is concerned with the emotional attachments that people form with places (Hernandez et al., 2007). Place identity is associated with the meanings that people attribute to places through their experiences, memories and beliefs about a place (Nora, 1984–1992; Tuan, 1974; Harvey, 1993; Anderson, 2015; Harvey, 1996; Nora, 1984–1992; Halbwachs and Coser, 1992). Place dependence is associated with how well a place is suited to the needs or activity of an individual group (Hunziker et al., 2007). Sense of place attachment depends on the strength of emotional meanings that groups of people and individuals associate with a place and a particular setting (Relph, 1976; Gieseking, 2014; Hummon, 1992; Stedman, 2003). Places are defined by physical and natural environment, and material reality (Casakin and Bernardo, 2012; Stedman, 2003) combined with the meanings that people associate with them. (Jorgensen and Stedman, 2001; Stedman, 2003).

Place attachment is also associated with well-being. Evaluation of the sociocultural significance of these places is a way to market the vernacular, simulate the authentic, and invent or preserve heritage and tradition (Harvey, 1993).

Attributes of sense of place for investigating the role of fishing heritage in communities’ place attachment

Previous studies regarding sense of place (Connerton, 1989; Shackel, 2006), recommend some attributes in regards to the values of fishing material culture and cultural entities regarding place attachment, place identity and sociocultural memory. In the discussion that follows, these attributes are assessed in relation to the cultural material and physical entities existing in fishing communities in Brunswick County in order to evaluate the non-market values of fishing heritage in these communities. Table 1 shows these attributes, which have been used in the present research for shaping the interview questions in order to evaluate the significance of material culture in the mentioned fishing communities.

| Non-market benefit | Attributes | Sub-attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Sense of place | Place attachment | Connection with the sea |

| Connection with the environment | ||

| Place identity | Fishing as a way of life Contribution of fishing in shaping community identity |

|

| Fishing influences place character through special materials, tools, symbols, decoration, buildings, etc. | ||

| Place memory | Memory of the past fishing activities | |

| Memory of the past traditional fishing places |

Commercial fishing communities in Eastern North Carolina

For over 200 years, North Carolina’s coast supported a successful commercial fishing industry and communities of citizens who relied on the industry for their livelihood (NC Grant, 2007). Brunswick County, which was formed in 1764, has a long history of fishing in the ocean, bays, sounds, rivers, and lakes (Provincial Archives of Brunswick website). It was named for the colonial port of Brunswick Town (now in ruins). The European merchants who settled here traded fish, among other commodities, and participated in other activities related to fishing, such as ship-building (Lee, 1980; Special staff of writers, 1919).

Brunswick County still has a large number of fishing communities. Fishing activities are linked to material culture such as boats, fish houses, ship yards, crafts, as well as rituals, cuisine, and traditions related to fishing and seafaring. These remains are a part of ongoing life tradition and are considered as cultural resources. However, due to the changes in the use of resources and land/sea-use regulation and policies, development and climate change, many of these sites are endangered. This suggests that some management of these resources may be necessary.

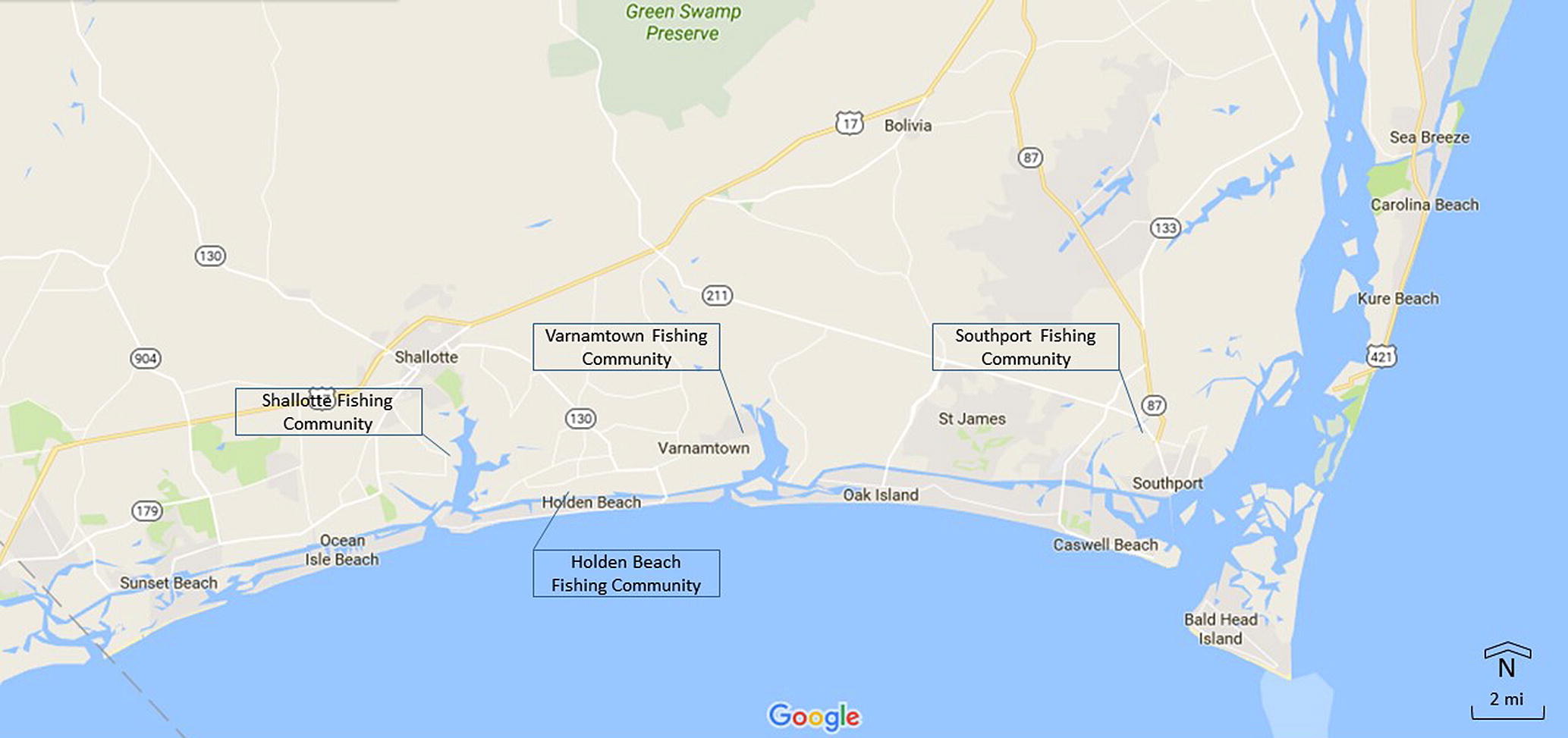

Archival and literature review, followed by site observation, showed that there are still several fishing communities and towns in Brunswick County, among which four have been selected here for closer analysis: Varnamtown, Shallotte, Southport and Holden Beach [Fig. 1].

Case studies

In order to understand the way that fishing cultural heritage influences fishing communities in North Carolina, a case study approach was adopted to explore the social wellbeing variables in a range of different fishing communities with different amount and state of cultural heritage in the southeastern counties of NC. Case studies are not meant to be representative of wider sociocultural phenomena but can instruct us about relationships among cultural heritage and specific human behaviors, perceptions, and activities. They are not, that is, surveys, censuses, or other types of inquiry that strive to represent larger populations, but trade quantitative representativeness for qualitative depth.

In the four areas, after site observation and based on their different socioeconomic conditions, four fishing, shrimping, and oystering communities were selected. Varnamtown has been chosen as the most vivid and active community and due to its reputation for fishing. However, a decline in commercial fishing can be noticed in the area. Holden beach also was chosen due to the fact that there is an ongoing fishing community and the community is trying to preserve commercial fishing. Southport was chosen due to its importance as a former fishing community which is now more of a tourist destination with remnants of commercial fishing remaining around its single fish house. Shallotte was chosen because it was known as a fishing community with two fish houses still active, but in decline.

Methodology

The study benefited from interviews with fishermen in different communities with different levels of fishing cultural heritage presence and preservation. The interviews included open-ended and closed questions. Open-ended questions are those questions that solicit additional information from the inquirer. By definition, they are broad and require more than one or two word responses, or a series of choices. Close questions are those that can be answered by either “yes” or “no”, a number on a scale, or some other simple response. The units of analyses are the fishing communities. The responses were analyzed with qualitative and quantitative methods.

To gain an understanding of the contribution of fishing to sense of place, an inventory was made regarding the physical characteristics and activities associated with fishing that contributed to a sense of place. Elements such as commercial fishing boats in the harbor, building type, presence of fishing gear and facilities in each community were recorded. The cultural values of these elements were assessed based on the criteria mentioned in National Registered Criteria (“How to Request and Submit a Study List Application”, 2016). In addition, according to North Carolina Division of Cultural Resources, individual buildings, sites, areas or objects which are studied by the Preservation Commission and judged to have historical, architectural, archaeological, or cultural value, and that the community believes the property deserves recognition and protection can be designated as Local District or Local Landmark, depending on their cultural, historical, architectural and archaeological values (“A Comparison of the National Register with Local Historic Designations”, 2016). This information was used, together with the data collected from the interviews, to explore the significance of fishing material cultural and built heritage in place attachment, place identity and place memory in shaping sense of place among fishermen.

In the design of interview questions the attributes of sense of place from Table 1 were used to inquire if and how different fishing material cultures and build heritage contribute to different sub-attributes of place attachment, place identity and place memory. In addition the questions were designed to direct the interviewees to talk about their level of satisfaction with their job, their interest in keeping fishing as their main occupation, and the future generation’s occupation choices. Previous studies showed that one constraint on the survival of fishing communities is the reluctance of the new generation to pursue fishing as their main occupation (Piriz, 2000). The answers to these questions helped further to analyze the correlation between the amount and state of existing material culture and the state of fishing in these communities. Since fishing as a traditional activity helps shape fishing heritage and the cultural landscape, in addition to livelihood (Nuttall, 2000), the interviewees were asked to state what types of material culture or/and heritage sites and buildings are important to them as items that depict fishing communities and sense of place, fishing activities and fishing characteristics, and fishermen’s memories. These statements were gathered through a combination of in-depth interview and photo elicitation. By applying content analysis, these data were analyzed to identify the items of cultural heritage significance for the fishing communities. In addition, the values associated to the cultural heritage items were categorized based on different heritage values for the fishing communities’ members. Also, the correlation between the quantity of fishing heritage site and fishermen willingness to stay in their present location regardless of their occupation was investigated.

For the purpose of assessing place attachment and place memory in the member of local communities, I handed out cameras to residents to take photographs of places they deemed important to their sense of identity and place, a method known widely as ‘resident-employed photography’ (Stedman et al., 2004)or ‘photovoice’ (Wang and Burris, 1997). To interpret the photographs, in-depth interviews are critical because they allow both researchers and participants to “better elucidate the content of the photo and the degree to which it represents sociocultural and ecological phenomena, and how these combine in potentially unique ways” (Stedman et al., 2004, p. 586). Visual approaches to data collection are beginning to gain traction in both tourism (Kerstetter and Bricker, 2009) and outdoor recreation context (Dorwart et al., 2010). The photos and interview text are analyzed using a process known as categorical aggregation, a series of techniques using labels, codes, and categories to organize qualitative data (Dewalt and Dewalt, 2002; Henderson, 1991; Mascarenhas and Scarce, 2004; Spradley, 1980).

The first step of analysis is to determine places of importance. The second step is to determine the meanings and experiences behind each of these place categories, using interviews as descriptive guides. Important meanings and experiences from photos and interviews should be indicated by the photographer. This method of inquiry allows participants to identify places that hold values and meaning for them and to explain that meaning in present fishermen life rather than responding to researcher’s prompts about place (Amsden et al., 2010).

A spatial analysis also was conducted in order to identify variables that can define the level of importance of fish houses based on their location, function, and access. Some results from interviews, in addition to direct observation of these locations were applied for this analysis.

The preliminary locations of the fishing harbors and fish houses were selected based on the literature and existing data from North Carolina Sea Grant reports (Jepson et al., 2005). The key informants were selected based on pre-studies and knowledge about the locations of the fish houses and fishing harbors. First each known fish house was visited in the case study areas. The fish house owners were interviewed. The rest of sampling was done using the snowball method, where participants recommended other potential informants (Babbie, 2010).

Results

Results from interviews

Forty three available members of fishing communities in four areas including Varnamtown, Shallotte, Holden Beach and Southport participated in the interview. They are engaged in seafood sales, boat repair and construction, fishing (fishing, oystering and shrimping), processing and packing, and a net shop. Except for a few, most of them have always been engaged in the fishing business since they were very young, as part of a family business. Many of them have finished high school and a few have had some college.

There are three active fish houses in Varnamtown, two in Shallotte (one specifically is an oyster house), only one fish/ice house in Southport, and three fish houses and one seafood market in Holden beach. Varnamtown also has a few places where people sell seafood directly from their homes. This is an evidence of the population’s attachment to marine resources. The fish houses in Varnamtown, Shallotte and Holden beach have market places adjacent to them which are in regular contact with public, and some of them also send out of state. But the fish house in Southport is a wholesale fish house that buys from local fishermen who land at its dock and sells both locally and nationally. Some seafood markets in Holden Beach and Oak Island buy from the fish house in Southport too. Other buildings around the current fish house in Southport were originally fish houses, but they have been transformed into seafood restaurants. Surprisingly, these restaurants do not get their seafood from the local fish house.

In Varnamtown and Shallotte, their main catch is shrimp and oyster, while in Southport and Holden Beach different types of fish in addition to shrimp and oyster are caught. They usually work with two to five crew on a boat. Some work with family members, and some not.

Fishermen are quite satisfied with fishing and some in Southport claim that during last year (since 2014) there have been more fish, and one should know where to fish. They describe fishing a hard and risky work with long hours at sea and far from family. However, they like it and enjoy doing it, because of excitement, anticipation and surprise; being out on the ocean and the connection with water; and independence. Some have no other skills to do other jobs.

Some fishermen mentioned that they changed their gears and/or adapted their boats for new fishing conditions, or switched to catch other types of fish due to the changes in regulations, and seasonal and natural factors. Some sell their catch locally at a certain fish house, but some go further from Pamlico Sound to the Gulf of Mexico. One person from Shallotte, who is very successful in his business, stated that he has always looked at the market and condition and tried to change and adapt to the situation.

They consider fishing as their way of life, continuos family vocation and a tradition that should be preserved. For most of them it is important to continue fishing as their main occupation. All people who were interviewed in Varnamtown stated that it is a strong fishing community where everybody in it is connected to fishing in one way or another. This fact, about Varnamtown, has also been confirmed by fishermen from other locations as well. The majority of interviews from Shallotte said that the fishing community is not as strong as it was before and it is a vanishing community. In Southport, fishermen have a great sense of attachment toward Southport. For many, the old waterfront is a highly valued memory. For example Kenneth Fex says:

“This place holds the tradition. The whole waterfront: the maritime museum, the Old American Fish Company, the name of Frying Pan, the tower in the sea, all show history and I have memories from my childhood and youth here.”

Another interviewee (Trey X) says:

“The waterfront here holds memories of fishermen and their families. The dock here reminds me of my youth and my memories of that time.”

In Varnamtown they stated that although outsiders might not completely understand the hardship of commercial fishing, they interact with the wider community on a regular basis and they believe that they usually receive the respect and attention that they deserve. In Shallotte, they believe that they are connected with the wider community who are not in fishing, but outsiders do not have a complete understanding of their job and its hardships. In Southport fishermen are not socializing with the newcomers to the area. In Holden Beach fishermen have a good relationship with outsiders and consider them important for their business.

In Varnamtown, the Oyster Festival is a social activity held every year. This activity brings many different people together, which is a good opportunity to learn about marine resources, commercial fishing, fishermen and their tradition as well (“PEOPLE AND PLACES: Coastwatch”, 2016). In addition, fishermen in Varnamtown, usually, gather at the three fish houses at the dock and there is one picnic area and Garlands Seafood where many said they gather. They stated that fishermen are well connected through phones and radios, and they enjoy a sense of solidarity that exists among them.

In Shallotte the opinions were different. Fishermen at Larry Holden’s stated that there is no network among them and they would not share information about the location of fish and good catch. By contrast, the fishermen at Lloyd’s Oyster House and the Inlet View Restaurant feel there is a good network among them, and that they share information about the fish and their catch. Their usual gathering locations are the restaurant, net shop, or Lloyd’s oyster house.

According to the interviews, commercial fishing contributes strongly to the character of Varnamtown. It is obvious from the fish houses, fishing boats at the dock, the fishing gears laying around, as well as decoration motifs at houses in the town. People believe that, with the loss of fishing in Varnamtown, developers will take over and the area will lose its identity as a fishing community. For them, and also most other interviewees in other fishing communities, the existence of fish house is not only a symbolic sign, but also a material manifestation of their fishing community. The boat rail in Varnamtown and Gordon net shop in Shallotte are the last of their kind in Brunswick County. Most interviewees, in all four communities, believe that the fish houses and some structures associated with fishing should be preserved as historical landmarks or areas, and become part museums, even if the fishing stops completely. This is important because these waterfronts show parts of the history of this area and its people1.

In Shallotte, members of fishing community had different views about the character of the area. Some stated that fishing played a great role in shaping the character of the area before, but now is gone. On the contrary, the fishermen around the oyster house believe that the character still exists and can be seen in fish houses, docks, boats, and the net shop. As in Varnumtown, they believe that if fishing stops, people would leave and development would take over. One reason that they consider caused decline in fishing in Shallotte is that the river in Shallot is no longerdeep enough for the bigger boats to get to the two fish houses there. Some of the fishermen stated that even the inlet is not suitable to pass through.

In Holden Beach, fishermen’s memories of traditional fishing related mostly to Southport. For them Southport has been the representation of a perfect fishing town. In addition to Southport, Old Ferry Fish House and the Holden Beach waterfront also convey strong memories related to commercial fishing.

Most people prefer to keep fishing as their primary occupation, even though some combine it with other work and some stated that they are not willing to switch to other jobs, even if they found it more profitable. But mainly they see no future in fishing and there are different points of view in encouraging younger generation to get into fishing. Those who encourage future generation to be engaged in commercial fishing, see the profession not as the primary way of livelihood. They would like to see that the legacy of commercial fishing will be transferred to future generation, but they feel that it will not be enough to make a living.

Some think that tourism can bring some benefit to them, and are willing to consider the options of getting involved in tourism. Some are willing to explain their work to visitors, some stated that they can arrange for short trips, showing visitors how commercial fishing is done. But several fishermen were against the idea of getting involved in tourism and they see tourists as disruption to their work.

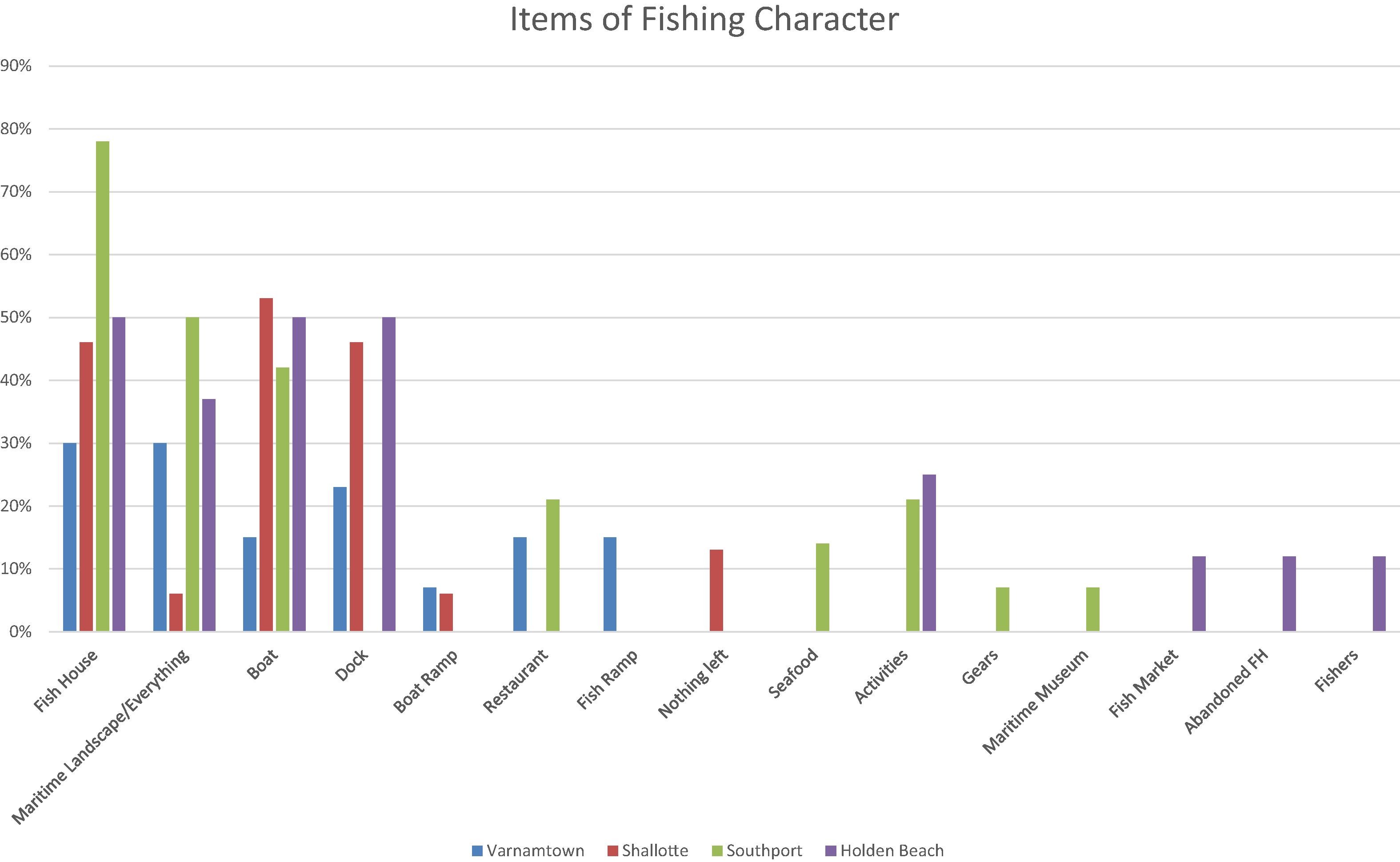

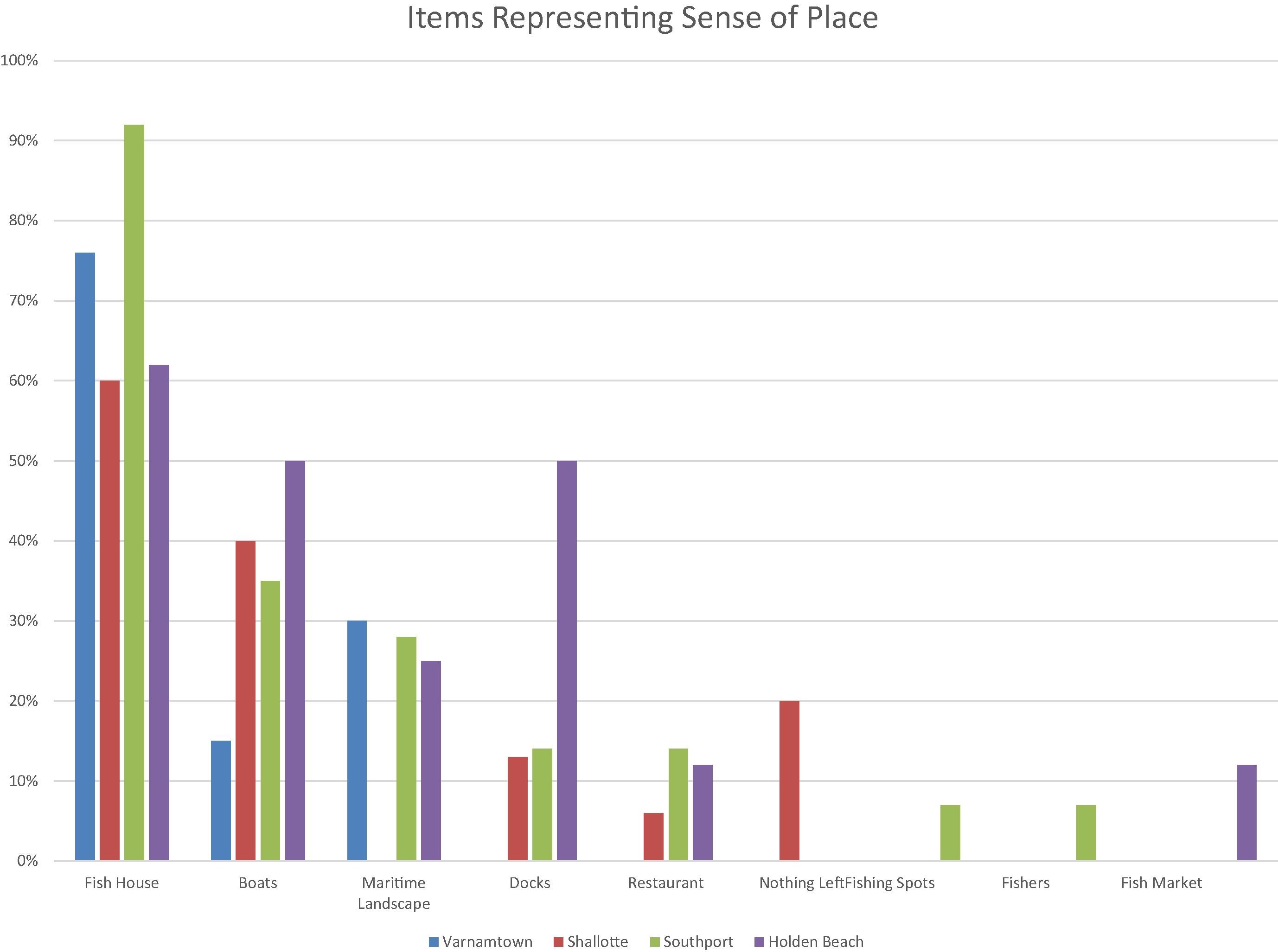

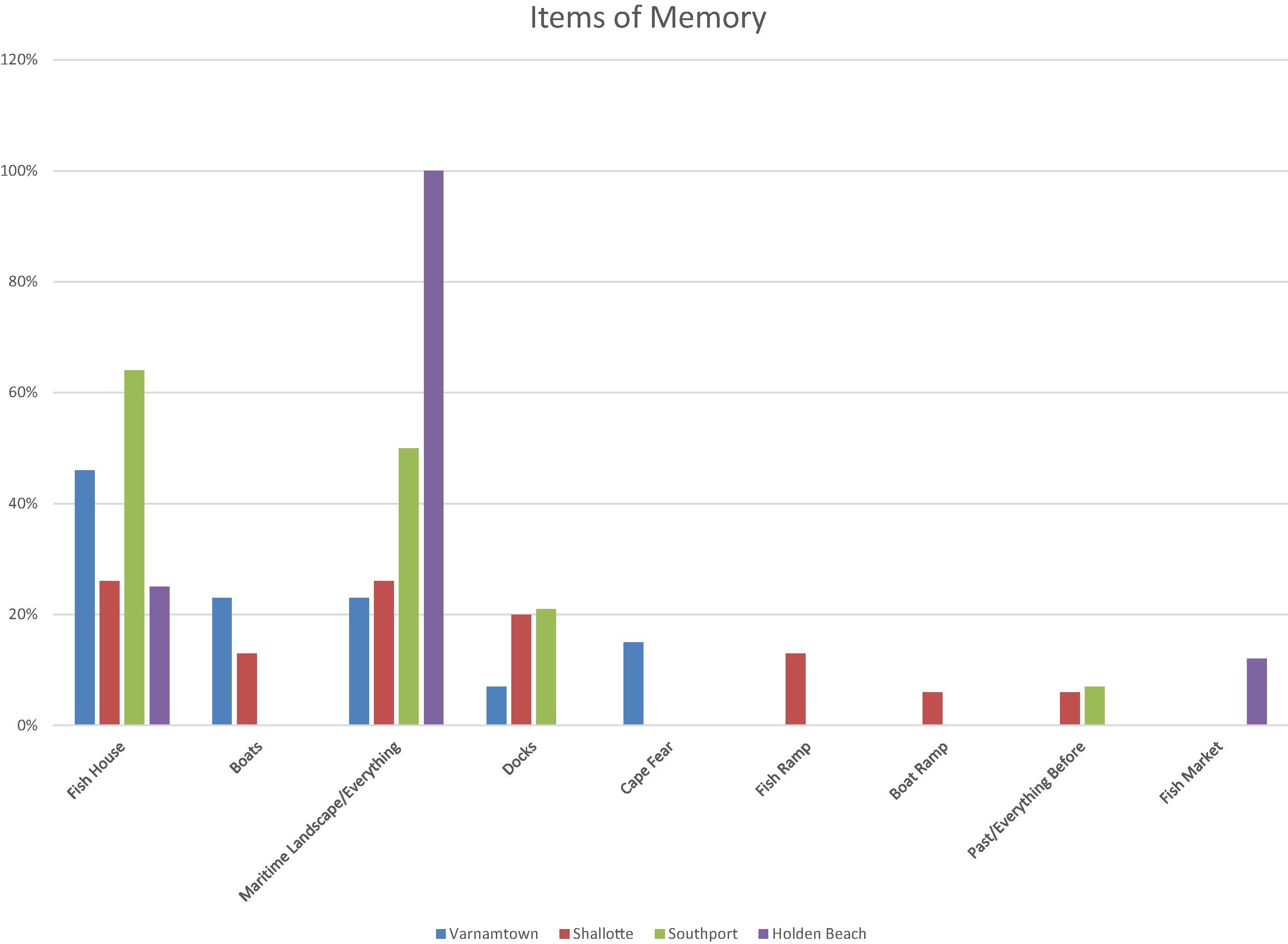

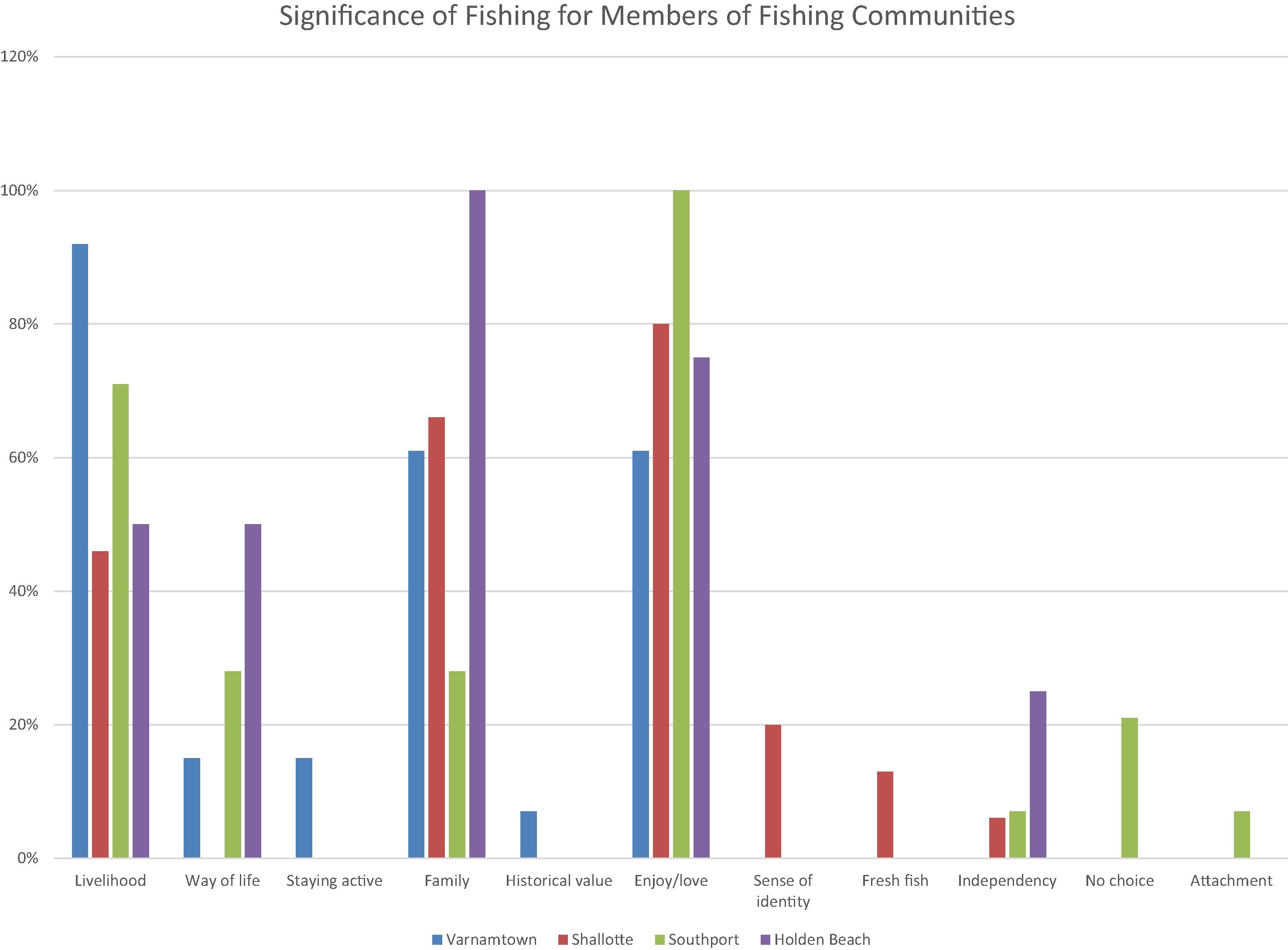

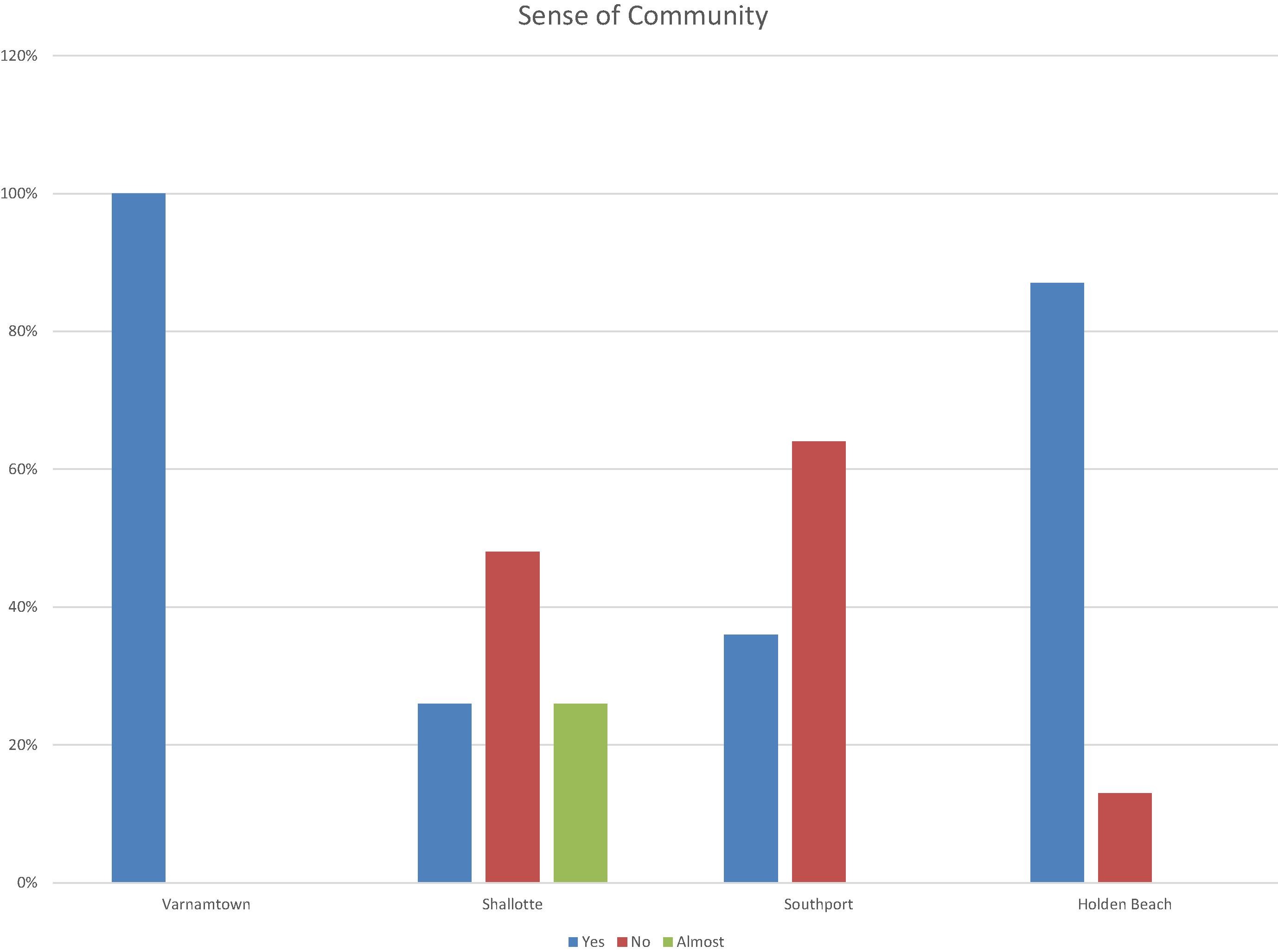

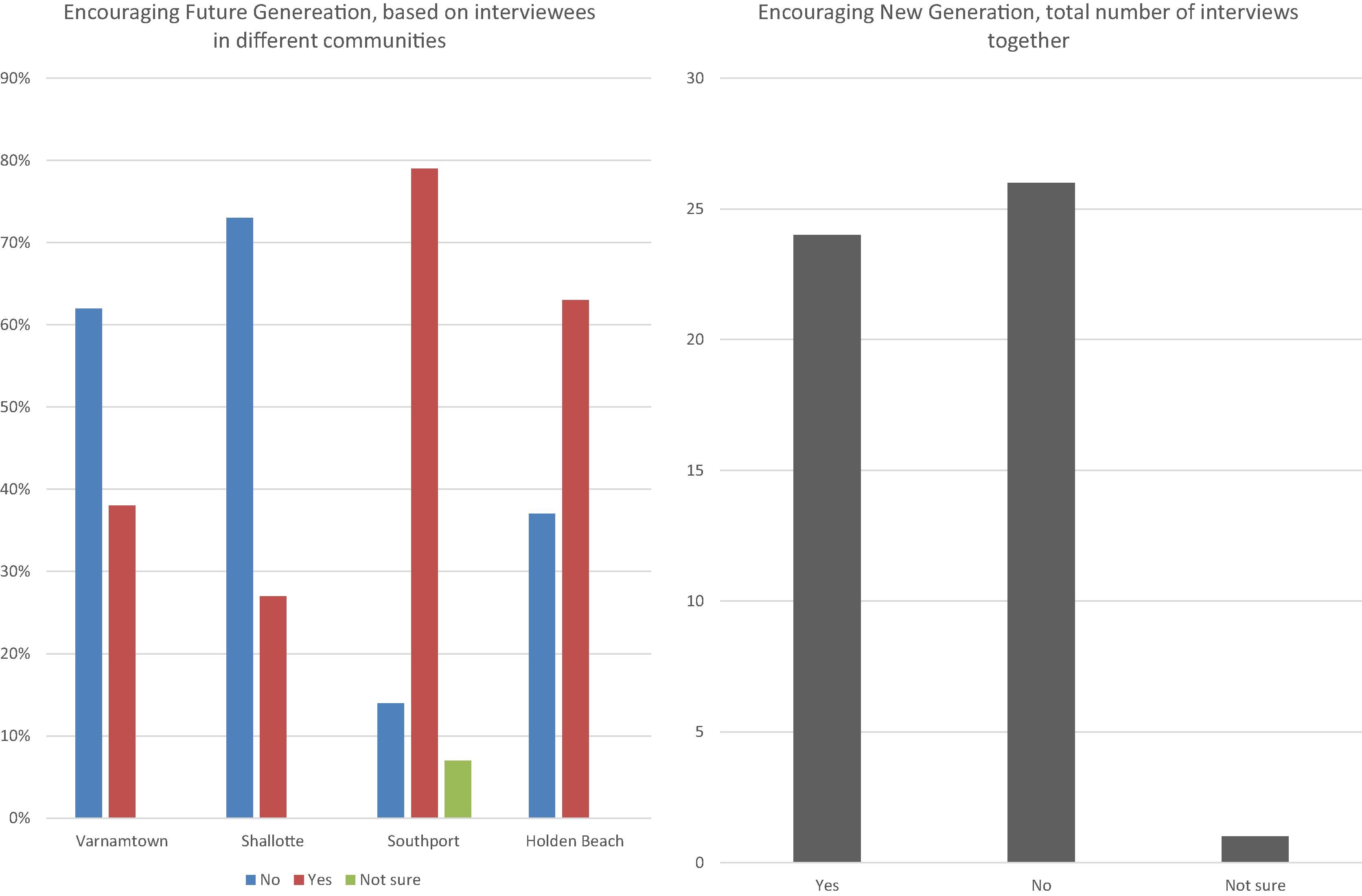

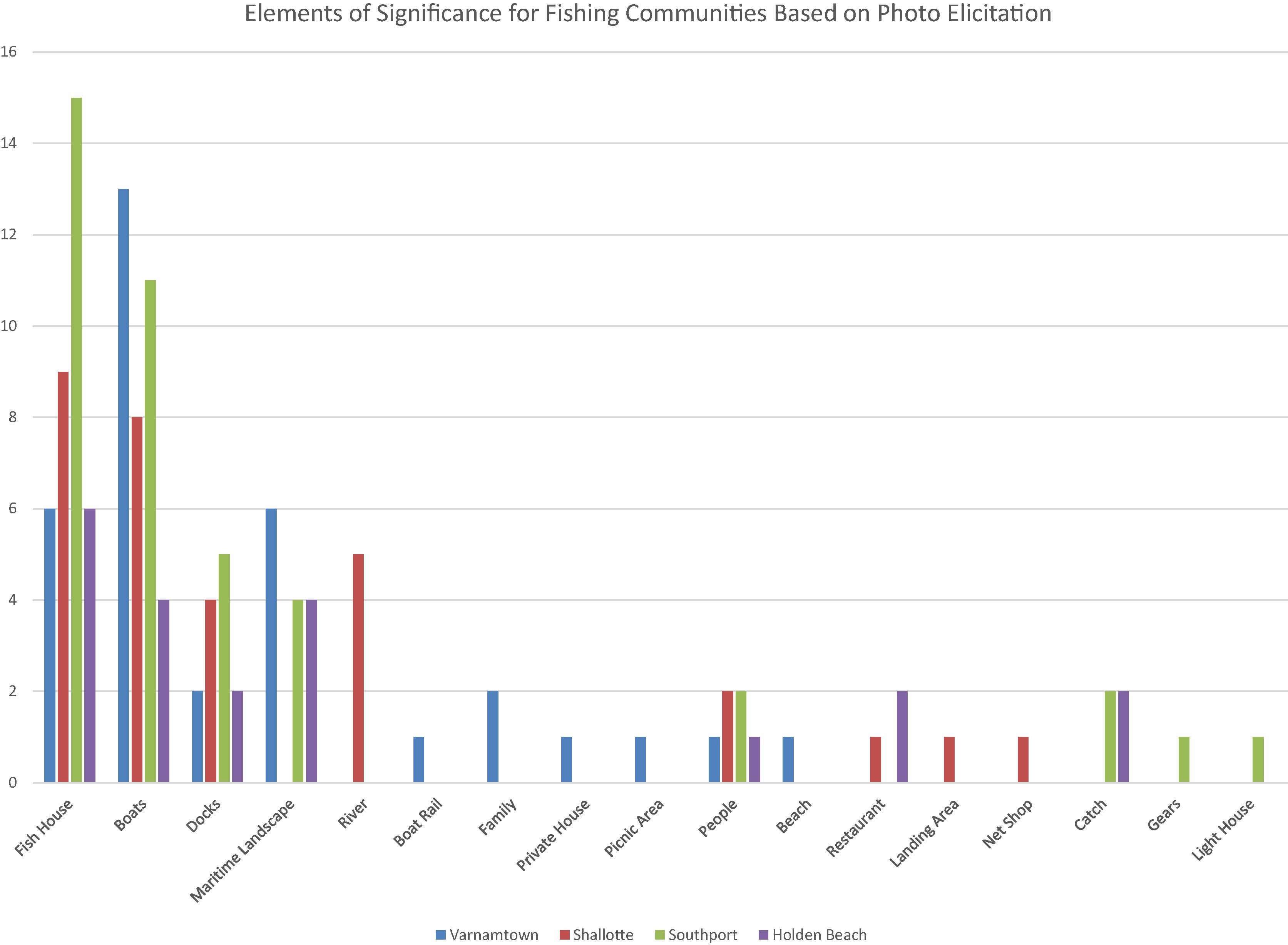

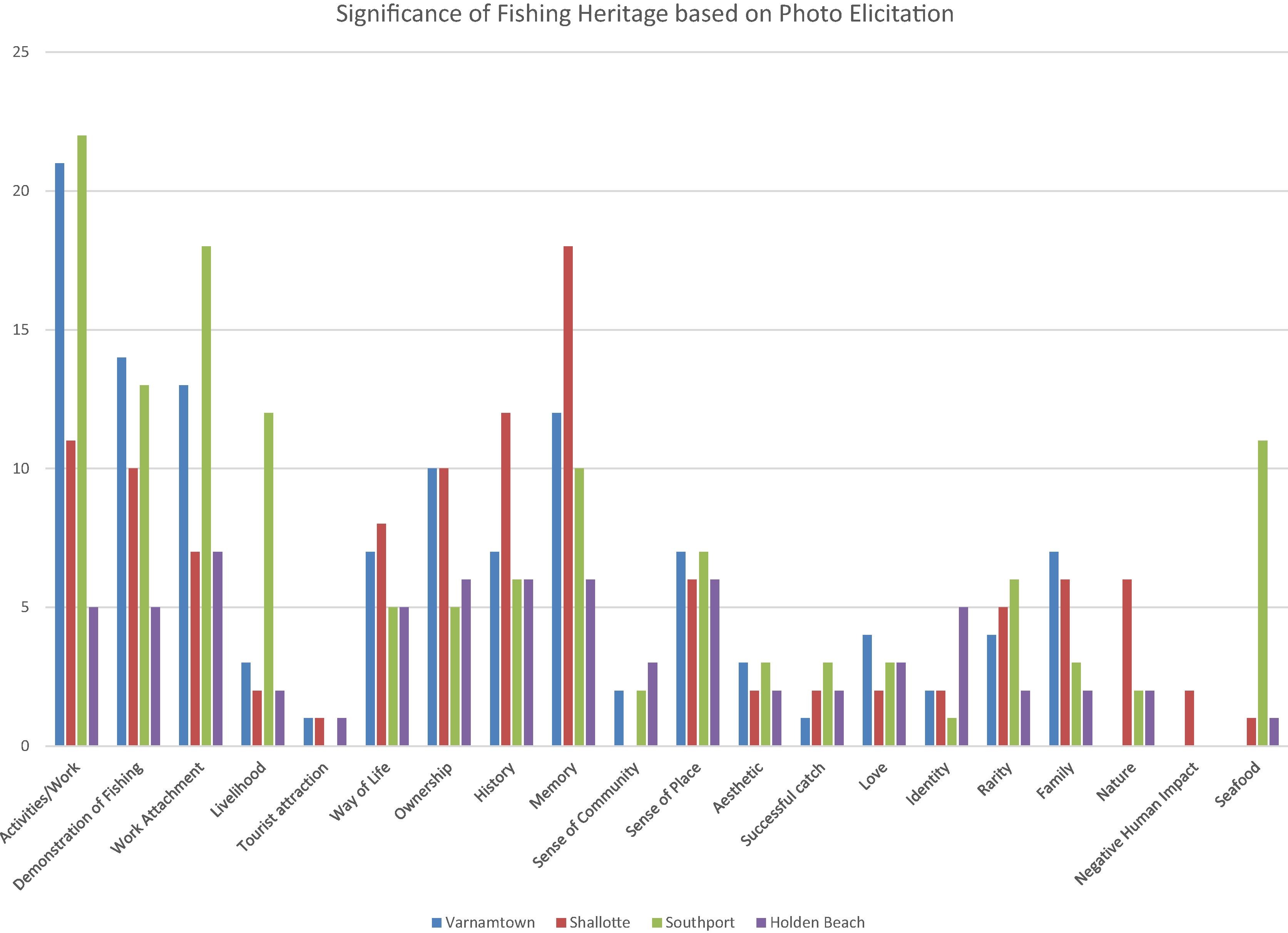

The results of interviews are summarized in the following charts. Figs. 2–6 show the items of fishing character, fishing memory, items representing sense of place, significance of fishing for the communities, and existing sense of community among the members of fishing communities. In general, the interviewees stated that fish houses and fishing maritime landscape including boats and docks are the most significant aspects of build environment for them. Enjoyment was stated as one of the main reasons that the fishermen continue fishing. Fig. 7 demonstrate how many of older members of fishing communities encourage new generation to engage in commercial fishing as their main occupation for future. It is noticeable that in different communities, the level of encouragement varies. In Varnamtown and Holden Beach majority of interviewees indicated that they would encourage the new generation to pick fishing as their main career or side-career, but in Southport and Shallotte it was the opposite.

Results from photo elicitation

The photo elicitation combined with in-depth interviews about the pictures that they have taken showed strong concordance with the results from the first set of interviews. Conducting photo elicitation among members of fishing communities highlighted three main items that are of significance for this fishing community: fish houses, boats, docks and maritime landscape. Members of fishing communities, also, highlighted significance and values that they associate with commercial fishing [Figs. 8 and 9].

According to the photo elicitation, boats, either fishermen’s own boats or fishing boats in general have one the highest level of significance for fishing communities. They are associated the boat with fishing traditions, memories and their identity, with their livelihood and daily activities and life. For example for Alex, a fisherman from Beacon Fish House, boats are important and he states that:

“I would take a picture of the wooden boats that come in full of shrimp. That shows the whole industry. They are reminder of the old fishing and shrimping that fading away, they are showing the work and tradition.” [Photo. 01]

However, boats are moveable objects. Among the fixed (immoveable) items that shape the maritime landscape, fish houses are the most mentioned items of cultural heritage values. Based on photo elicitation, fish houses are in the highest level of importance for fishing communities. According to the interviews fish houses are the most significant elements of memory, sense of place and fishing character in fishing communities. They consider fish houses as buildings that represent fishing and seafood industry. Fish houses represent a place where they work, sell seafood, and sometimes it represents a place where their life have shaped around it with their families and friends working in them.

One of the fishermen in Varnamtown states that:

“I took a picture of fish houses, because I work here. Any of them is history. All of them are the same to me. All we have the same occupation. It shows hard work and a lot of fun, talking while working, telling a lot of lies.”

Jay Robinson, the owner of Beacon Seafood states:

“I took a picture of my building [Beacon Fish House]. It is the only thing that has not been changed in my life. I spend 90% of my time here. I am very satisfied with my life and career.” [Photo. 02]

Mr. Garland and his wife Jackie, who own the Garland Seafood took a picture in front of their own fish house. He states that:

“I would take a picture of my wife and me at our fish house, because we have worked here all our life together. It is full of memory.” [Photo. 03]

Those who took photos from the whole landscape, mentioned several reason for that, stating the aesthetic values of the fishing landscape, as well as the importance of documenting a part of history and a traditional activity that is fading away.

Ronald Galloway from Beacon Seafood states that he would take an aerial picture of the area around Varnamtown fishing docks:

“I would take an aerial photo of all the area around here. You could see the general area, you could look what are happening, and you could see everything.”

He also took a picture of the dock and boats tied up at the fishing house dock and stated:

“They are interesting, to show people where we work, what we do. In future they will see where we were one day. Keep it for keep sake. Everything has been changed and all will be changed in 50 years. It will remind to what it was before.” [Photo. 04]

One site that is particular to Varnamtown is the boat rail. Although this site is the only of its kind in this area, it was not considered as an element of significance, memory or fishing character in the interviews. However, only one person mentioned it in the photo elicitation and took one photo of the site and stated:

“The boat rail is where the boats pull out. It is the only one from Florida to Wancheese. There used to be 15 of them, but now only this one.” [Photo. 05]

In Shallotte, there has been a focus on river as an element of significance for fishing which shows the connection that fishermen feel with the water and natural environment. Fishermen see the docks as an element of significance which shows the fishing activities such as docking, loading and unloading fish.

Mitchel Smith, a fisherman from Shallotte, took a picture of Larry Holden’s seafood and states that:

“This is Larry Holden’s Seafood. This building is important, because it has been there so long and that’s one of the only things left.”

Another photo from the same building has been taken by Gordon Winfree who states:

“Larry Holden’s seafood reminds me of old ways of fishing. He has shrimp boats.” [Photo. 06]

People who suggested the river, and took a picture of the river and the natural environment, were more concerned about the way that the original state of the river has changed and emphasized the negative human impact on the quality of the river. One person also remembered the good old times from the river and the natural environment, when he and his wife sailed on the river.

The unique place in Shallotte is a net-shop. It was mentioned in the interviews and also showed up in the photo elicitation study. For instance, Stanton Smith took a picture of a part of the net-shop building with nets hanging out. He associated the net with the feeling of fishing and water, and states:

“Gordon’s net shop is important, because of what they do. They hang nets and it gives the feeling of fishing and water.” [Photo. 07]

Tatum fish house was mentioned as the sole place in Southport that fishermen can sell their fish and mostly people took picture of that particular fish house [Photo. 08]. This building carries values for many of them since this fish house is the last standing and active fish house in Southport. They consider this building representing fishing character and sense of place in Southport at the moment. For example, Alex Tatum took a picture of the fish house and says:

“Tatum fish house is our landmark in Southport as the last working fish house.”

John Porter states the reason of taking picture of Tatum fish house as:

“Because I sell here, and it is the only one left here.”

Some also took pictures from the buildings that had before been a fish house, and now are restaurants. For example the Old American fish Company, which is a restaurant now, is considered of great value. The building is the oldest fish house in Southport and listed as historical property.

Other elements that are of significance for fishing community at Southport as part of their heritage, are the dock and boats, which are almost in the same level of value for the community.

For them boat is what takes them to the sea and is a vessel which helps them catch food. For example, Chris took a picture of a boat and says:

“Boat, any boat that I go fishing with. It is a vessel to catch fish with.”

Donald Lowe took a picture of his own boat and states:

“Because it is mine and I fish with it.” [Photo. 09]

Trey took a picture of the fishing dock and states:

“The dock here at Southport reminds me of my youth and memories of then. And the time that it was a fishing town.” [Photo. 10]

Their pictures of the boats mostly have a prominent view of the docks, especially the dock at Tatum fish house, as well.

For Southport fishermen, the significance of fishing heritage and the physical remains from traditional fishing are mainly due to the fact that these remains show the fishing activities and their work which is the source of their livelihood. Although, they do not consider Tatum fish house as a historical building since it is a new building, they state that it is of traditional significance because it is the only building that shows the ongoing tradition of fishing and they associate it with old fishing town of Southport and a building that shows the sense of place. The members of Southport fishing community have a strong sense of memory from the past fishing town of Southport.

Many people interviewed took photos of seafood and fish being landed times and interviewees stated that the friendly competition of catching the most and biggest fish has always been a part of tradition in Southport.

The result of photo elicitation from Holden Beach fishing community shows that the elements of fishing heritage that are of the greatest significance for the community in addition to fish houses and boats are maritime landscapes. Although, the observation from Holden Beach reveals a unique fishing community there, most interviewees referred to Varnamtown and Southport and their different buildings as examples of a fishing town and fishing heritage. For example, Frying Pan Tower and Old American Fish Company from Southport were mentioned a few times and they took pictures of these buildings. However, more specifically, in Holden beach, the maritime landscape around Old ferry Seafood was mentioned several times. Anna, one of the owners of Old ferry Seafood, took a photo from the other side of the river towards their fish house and the boats and states:

“The dock and boats here is what everybody takes picture of it. It shows our work. From the other side of the river” [Photo. 11]

One specific site at Holden Beach is an abandoned fish house and a partially submerged boat in front of it. Travis Elliot took a picture of this site and states:

“The old fish house and the boat show the history and the career that is vanishing. It is the memory of people who lived here and worked here as fishermen.”

In addition to the common significance of activity, work and ownership, people feel the value of history, Identity, sense of place and sense of community. They express these feeling through mentioning that their whole life has been shaped around these buildings and their activities, and they are connected to these places through their memories, activities, buildings and boats, and families.

They expressed these feeling through their pictures and their explanations on those pictures. For example, Anna from Old Ferry Seafood took a picture of their fish house and states:

“This building is important to me, because I grew up here and I have so many memories here. I lived here with my husband when we married. I love it here.” [Photo. 12]

Travis Elliot expresses the sense of place and the significance of fishing tradition by taking a picture of the Capt. Pete fish house, where he worked all his life. He states:

“It is the place of fishermen to come. It has been all my life. These buildings are a part of traditional waterfront.”

The in-depth interviews that were conducted after acquiring the photos in these communities highlight fishing heritage and material culture as a way manifestation of the significance of fishing traditions and fishermen’s ways of life to the public. Memory and history are also factors that according to fishermen are part of the significance of the fishing heritage. Sense of attachment and ownership are other factors that made several fishing heritage of value to their owners and they stated the interest in preserving those heritage elements, because they own them [Fig. 10].

Spatial analysis

Boats moves, fish houses don’t! The dependency of fishing sense of place to fish houses…

The results of interviews and photo elicitation from all these four communities show that the most significant building associated with fishing are the fish houses. Fish houses are the linkage between sea and land (Griffith, 1999). Although there is a mutual dependency between fishermen and fish house owners (North Carolina Rural Economic Development Center, 2013), the fish houses have a more dominant role in the shoreline as provider of ice, fuel, storage, packaging and general merchandise. They are the core point of business between the fishermen as provider of fish and buyers (either individual or whole sale.) Yet fish houses are different from each other. A spatial analysis, considering different factors about the fish houses in Brunswick County revealed some major differences among them.

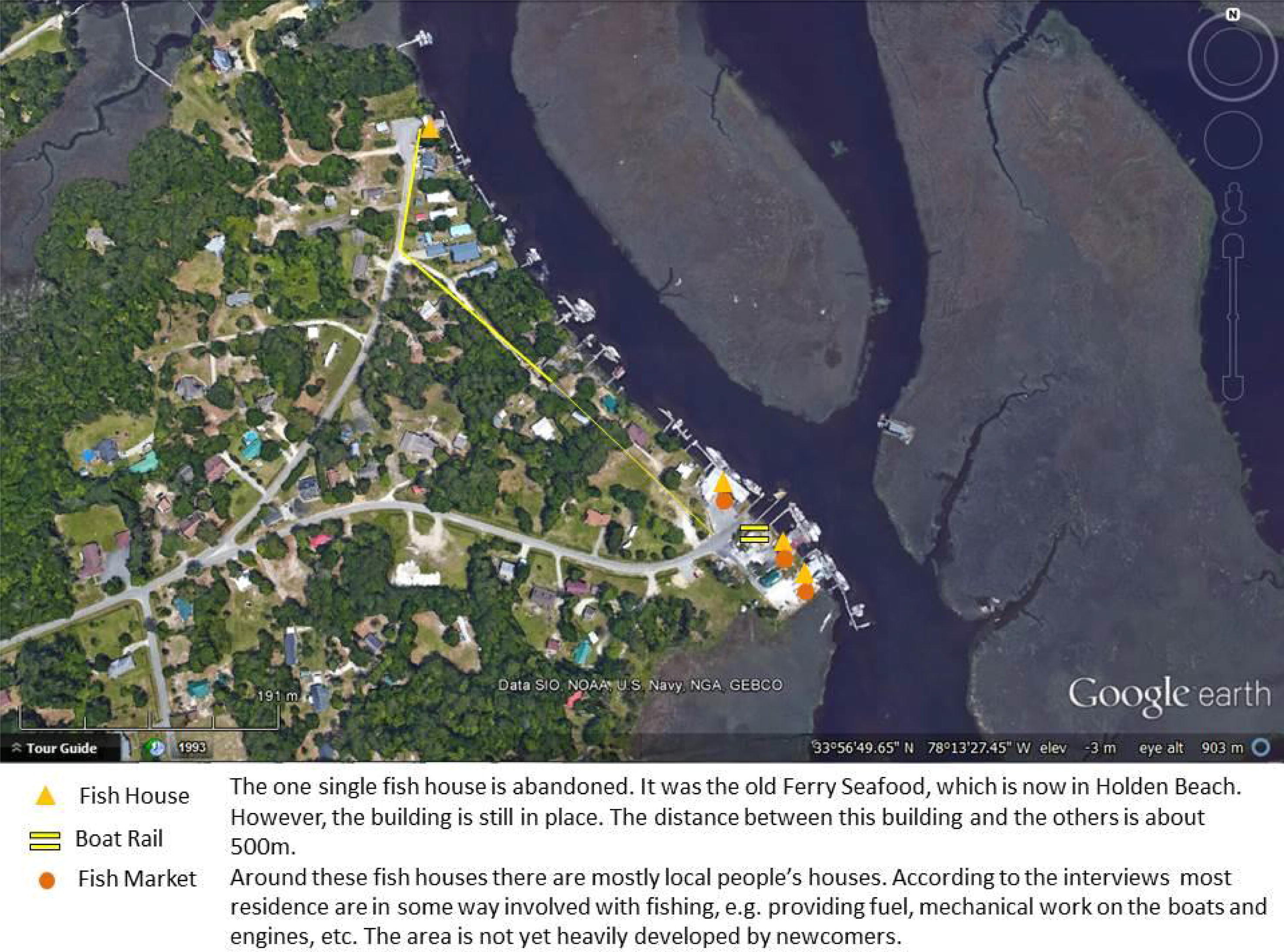

Varnamtown has three fish houses still operating, with fish markets adjacent to them, in addition to a boat rail (the only boat rail in southeastern North Carolina). Furthermore, there is one fish house that has closed, but the building and its dock are still in place. The area around Varnamtown fishing community has not yet been gentrified with new development. Most residents are local people, engaged in fishing related businesses, if not fishing then other services, such as boat repair, providing fuel for fishing boats, packing seafood, and making nets and TEDs for shrimpers. The area is in closer to the inlet and to the ocean, and therefore, more and bigger fishing boats can reach these fish houses. These fish houses are very close to each other and have a good connection with each other [Fig. 10]. Additionally, they enjoy a well-managed distribution of seafood, including imported and locally caught shrimp, not only through wholesale, but also through direct contact with individual customers. Fishermen and fish house owners have a common social-cultural memory from the past and value their fishing tradition.

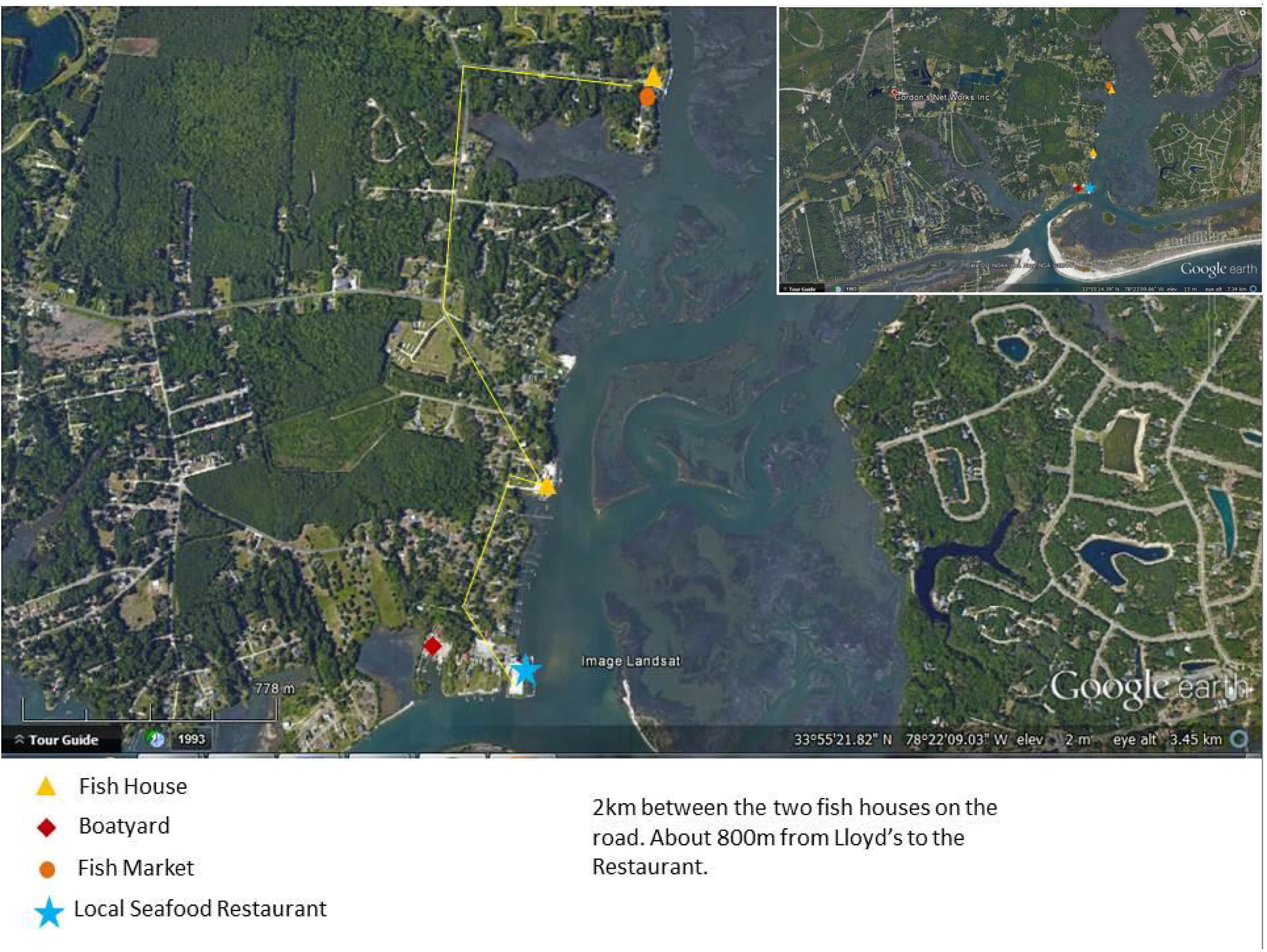

Shallotte is the furthest south commercial fishing community in Brunswick County before Calabash. This area also is the closest of the four communities to the Gordon Net Shop. Although there are several other locations such as S&S Marine that sell nets and provide services for net repair, Gordon net Shop is the only shop in the area whose only activity is net making and repair. The two fish houses in Shallotte are very different in their way of operating and success. The northern one (Holden Seafood and its adjacent seafood market) is to some extent isolated. The area is dominated by new urban development. According to the fishermen, big boats cannot get there anymore, due to the fact that the channel is not being dredged and is not deep enough anymore, and therefore the business have gone down. However, two kilometers down along the same channel, the Lloyd’s Oyster House is operating well [Fig. 11]. The houses around this oyster house are mostly local residents and fewer outsiders live in the surrounded area. Still large untouched natural landscape exists close to this fish house. In addition, the fish house is near a local seafood restaurant and a boat yard. In fact, the fish for the restaurant is partly provided by Lloyd’s. The concentrations of the activities of the oyster house, boat yard and the restaurant, in addition to more local people living in this area and involved in fishing related activities, have provided a stronger sense of place and maritime landscape in this area than in the area around Holden’s Seafood. Lloyd’s Oyster House has a good networking between the suppliers (fishermen) and the buyers. The good contact between fishermen and the oyster house, and the distribution of the fish/oyster to the local restaurants, as well as its vicinity to other fishing related activities are the strong points of Lloyd’s Oyster House. On the contrary, although Holden Seafood has a market as a point of connection with public, its location and lack of networking among fishermen, and difficulties of navigation of big boats in the river, along with growing urban development, have caused its isolation, and reduced its strong sense of place regarding the physical aspects of maritime cultural landscape.

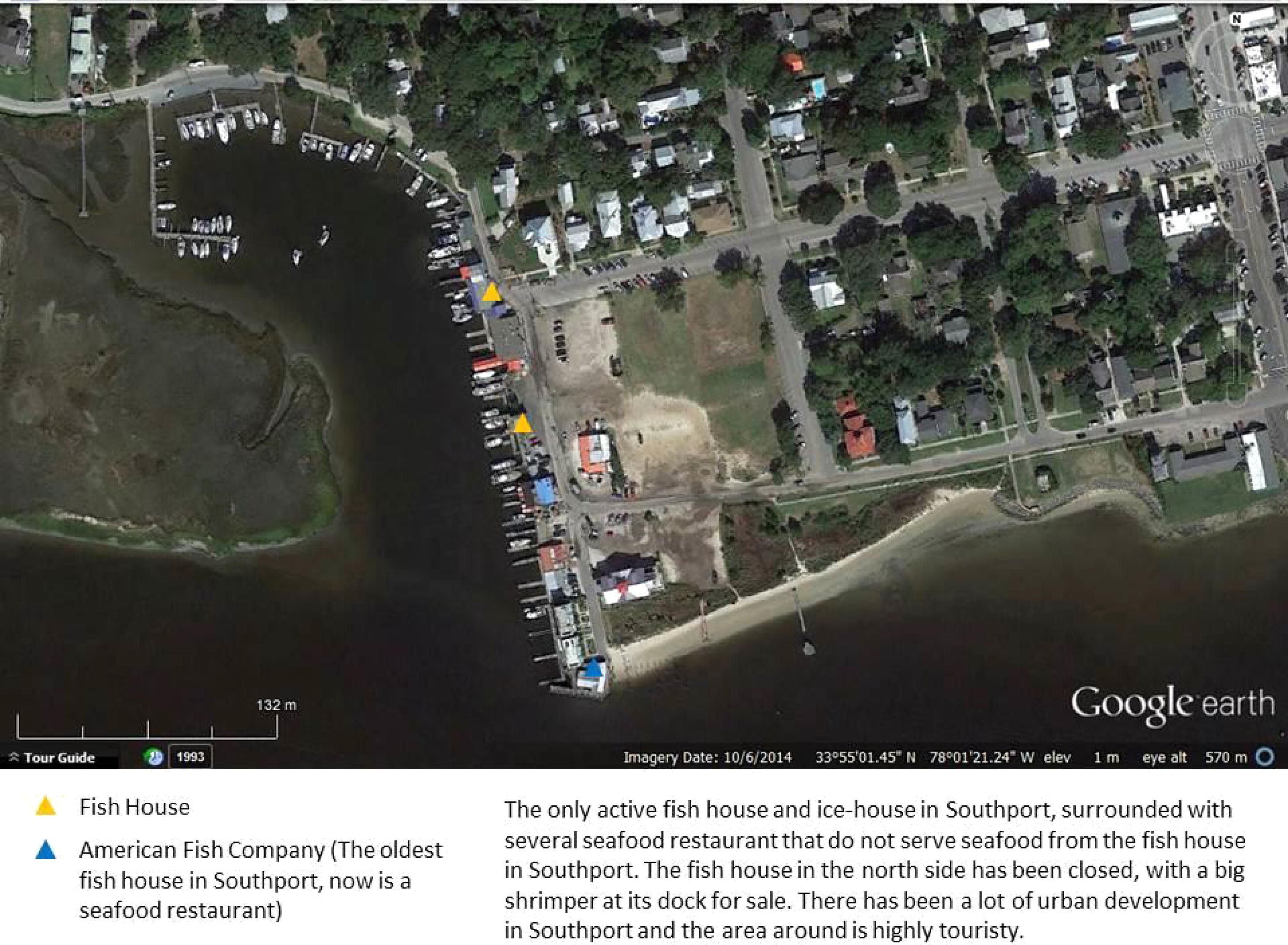

The one operating fish house in Southport is located in the middle of (seafood) restaurants in the touristy part of the town and all around it is urban development. The port is a marina with recreational boats and recreational fishing [Fig. 12]. Although it seems integrated in the town, the fish house is essentially a sanctuary for fishermen. This fish house has only wholesale seafood and conducts no trade with the public, including not providing seafood to neighboring restaurants. However, fishermen have a good network here; they gather here and exchange stories. They are open to outsiders coming to visit and share their stories. There is only one other fish house with a shrimp boat anchored in front of it. However, the building was closed during the one week of our research in Southport, and apparently is not operating on a regular basis.

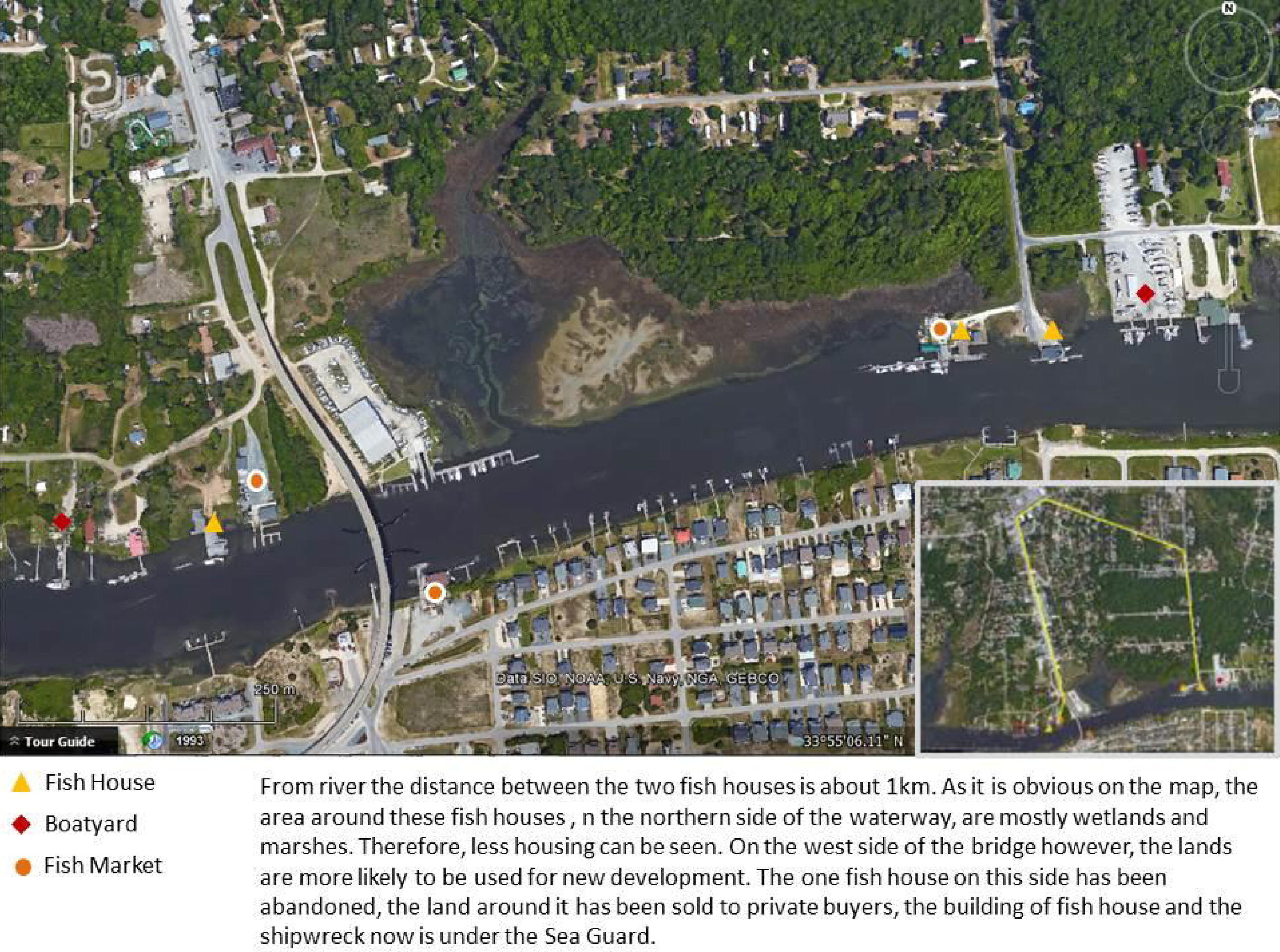

Fish markets, fish houses and docks can be seen in several locations along the shoreline of Intercostal Waterway in the Holden Beach area which provides a sense of active commercial fishing [Fig. 13]. Several shrimp boats were observed during the field work. There are three fish houses in Holden Beach and located about a kilometer from each other along the northern shoreline of the Intracoastal Waterway. They have a strong connection with the public through the fish markets adjacent to them. The owners remember the past fondly. There are a couple of boat yards and docks close by and a famous fish market on the other side of the waterway. They have established a good connection to public through sharing historic pictures, selling shells from the fishing trips, and sharing stories. Fishermen have a good network and most of them are connected to each other. The area around these fish houses are mostly wetlands and marshes. Therefore, less urban development can be seen.

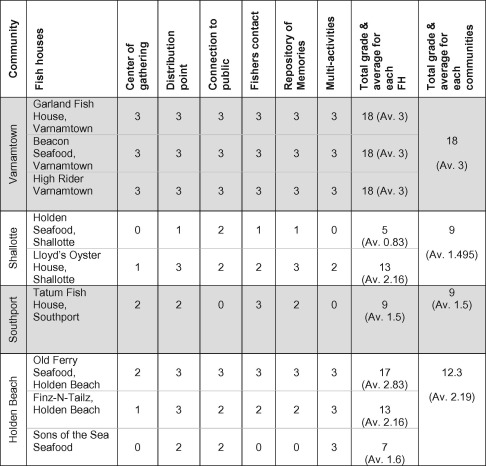

According to the spatial analysis above, some variables can be extracted to assess the state of fish house operation and the maritime landscape around them. These variable are summarized in the following table [Table 2] in relation to each fish house/or groups of fish houses.

|

Based on the interviews that were conducted with members of fishing communities and empirical studies of the activities at fish houses, the table shows an interpretive evaluation of the state of each fish house as well as the total sum in each community. The extracted variables includes social values such as being center of gathering; distribution point; fishers’ connection; connection between fish houses and public; and among fishermen; and repositories of memories. An ordinal level of measurement was used in the interview questions to measure the level of existence of different variables in relation to each fish house. The values are non-existent (0), weak (1), moderate (2) and strong (3). In the interviews designed for this research, the members of fishing communities were asked to grade each of these variables for different fish houses in the area. The higher the grade is, the more values are associated with that particular fish houses. The last Column shows an overall value of each community according to their fish houses. Existence of other activities, such as boatyard, restaurants, and seafood markets, in the nearby area is an added value in shaping a more harmonious maritime landscape which also involves more people and community members in the activities related to fishing.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper created an inventory of the existing traditional fishing communities in Brunswick County and assessed the level of significance of fishing material culture including buildings, sites and boats in shaping sense place among fishermen and demonstrating the character of fishing. Also the results highlighted the specific sites and items that carry the most significance for fishing communities. Continues use of these traditional buildings, sites and items, which are the remains of a fading long traditional activity in this area, and is a part of a changing era, can be used for livelihood promotion through branding their communities as cultural communities in order to promote heritage tourism, education purposes and awareness rising.

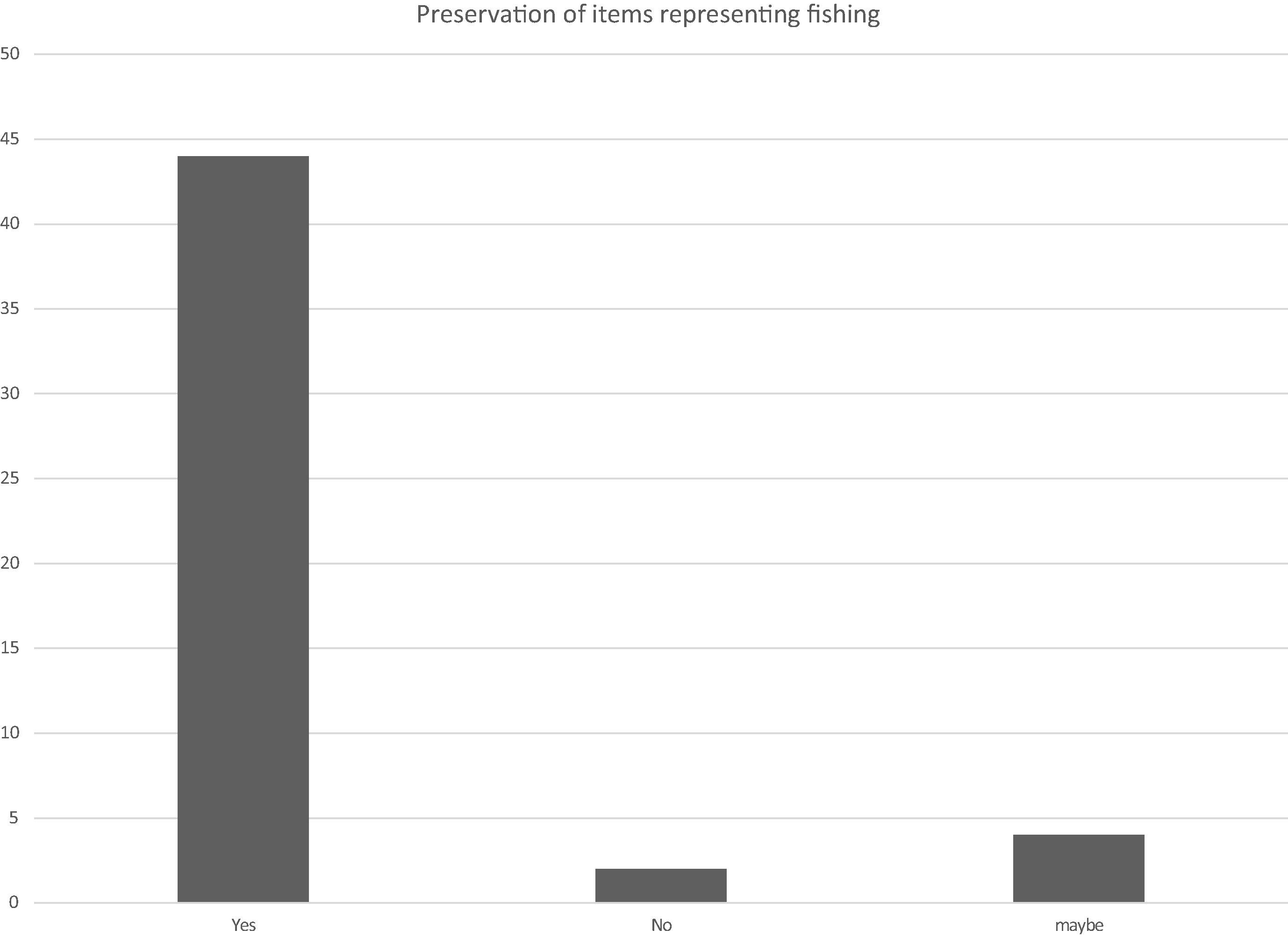

Fishing material culture, including fish houses, boats, docks, etc., are significant for fishermen and their communities in sense that they represent their authentic activities, and they feel these items and places are repositories of history and memory, representing their individual and community’s identity and sense of place. These buildings and sites are landmarks that form their traditional environment. Although, some might not carry historical values, since they help representing their traditional activities, they believe these buildings and sites should be preserved as part of their heritage, for present and for future generations [Fig. 14]. The result highlights the non-market values of fishing cultural heritage as a component of ecosystem services2, where cultural heritage is generally a forgotten and unappreciated aspect of ecosystem services (Milcu et al., 2013; Camarsa et al., 2012; Ash, 2010).

Therefore, there is a need to include not only economic valuation, but also more qualitative evaluation and discourses that reveal how place attachments plays a significant role in individuals and communities’ identities. This directly can improve our understanding of benefit and wellbeing which is an important aspect towards management of coastlines. New approaches, considering different types of resources, including cultural heritage, have the potential to help decision makers design policies or management strategies that can help achieve socially, ecologically, and economically equitable and sustainable outcomes.

Some members of the fishing communities are open to new ideas, if it helps them preserve their original fishing activities. Through this study, the hypothetical option of promoting cultural tourism was introduced to the fishermen. Cultural tourism constitutes tourism highlighting traditional activities without disturbing their authenticity. A majority of fishermen and fish house owners showed interest, at least to explore the possibilities and options. Although, some are pessimistic and feel that tourists might disturb their work, or visitors might not even be interested in what the fishermen do, there are number of people in each community who are interested in pursuing the idea.

Following the field work and the rapid assessment of buildings and sites, this paper concludes that many of these items hold cultural and historical values. They demonstrate a tradition that forms part of the people’s culture. Under the Historic Preservation Criteria, since community members believe some of these properties deserve recognition and protection, they can be designated as Local District or Local Landmark. All the elements of fishing heritage are parts of a maritime cultural landscape and the cultural significance of these properties only can be highlighted through the ensemble value of all these sites. Therefore, the present paper suggest considering a serial cultural nomination and registration for the properties which contribute to shape the fishing character and sense of place. Serial nomination and registration means that places and items that have been considered culturally, traditionally and historically important for the local community will be proposed for registration all together, even though they are in different areas. This is a practice that was promoted by UNESCO for listing World heritage sites (Guidelines for the Preparation of Serial Nominations to the World Heritage List, 2016)3. However, in smaller scales this can be a good strategy for highlighting the values of certain heritage locally, regionally and/or nationally. The fishing areas in Varnamtown and Holden Beach can be considered the core and a start point for formulating Fishing Cultural Landscape as Local Landmark. The fact that adding these areas to the Historic Preservation lists gives more attention to the values of these sites helps not only to promote knowledge and understanding about traditional and commercial fishing, and increase the chances of promoting fishing cultural tourism in this area, but also to develop policies to preserve these areas as operational working waterfront, and to protect and promote associated fishing communities’ tradition and livelihood. All this will help fishing communities to preserve their authentic way of life, their identity and sense of place as part of their sociocultural wellbeing, and add the traditional fishing and their material culture as cultural resources in the management plans of North Carolina coastal area.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to appreciate the supports that they have received from Institute for Coastal Science and Policy and East Carolina University. Many thanks to Nicole Wittig and Jeremy Borrelli for their assistance in collecting data and conducting interviews.

Endnotes

References

- A Comparison of the National Register with Local Historic Designations, 2016 A Comparison of the National Register with Local Historic Designations. Hpo.ncdcr.gov. Retrieved 10 July 2016, from http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/compare.htm. 2016.

- Acott and Urquhart, 2014 T.G. Acott, J. Urquhart Sense of Place and Socio-cultural Values in Fishing Communities Along the English Channel. J. Urquhart, T.J. Acott, D. Symes, M. Zhao (Eds.), Social Issues in Sustainable Fisheries Management (2014)

- Act of 2005, 2005 Act of 2005, Federal Working Waterfront Preservation Act of 2005, accessible at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/senate-bill/1723.

- Act of 2009, 2009 Act of 2009, Keep America’s Waterfront Working Act of 2009, accessible at: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr2548/text.

- Altman, 1993 I. Altman Dialectics, physical environments, and personal relationships. Commun. Monogr., 60 (1993), pp. 26-34

- Amsden et al., 2010 B.L. Amsden, R.C. Stedman, L.E. Kruger The creation and maintenance of sense of place in a tourism-dependent community. Leisure Sci., 33 (1) (2010), pp. 32-51

- Anderson, 2015 J. Anderson Understanding Cultural Geography: Places and Traces. Routledge (2015)

- Ash, 2010 N. Ash Ecosystems and Human Well-being. Island Press, Washington, DC (2010)

- Australia ICOMOS, 2000 Australia ICOMOS, 2000. The Burra Charter: the Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance, with associated Guidelines and Code on the Ethics of Co-existence, accessible at: http://www.bayside.vic.gov.au/documents/BURRA_CHARTER.pdf.

- Babbie, 2010 E. Babbie The Basics of Social Research. Wadsworth Cengage Learning, Belmont, CA, USA (2010)

- Barrett, 1992 Barrett, M.G., 1992. Coastal Zone Planning and Management: Proceedings of the Conference Coastal Management ’92, Integrating Coastal Zone Planning and Management in the Next Century. Organized by de Institution of Civil Engineers and Held in Blackpool on 11–13 May, pp. 56–69.

- Bradley et al., 2009 D. Bradley, J. Bradley, M. Coombes, E. Tranos Sense of Place and Social Capital and the Historic Built Environment. Newcastle University’s Centre for Urban & Regional Development Studies (CURDS), Newcastle University’s International Centre for Cultural Heritage Studies (ICCHS), Bradley Research & Consulting (2009)

- Bradshaw et al., 2001 M.T. Bradshaw, S.A. Richardson, R.G. Sloan Do analysts and auditors use information in accruals?. J. Account. Res., 39 (2001), pp. 45-74, 10.1111/1475-679X.00003

- Brookfield et al., 2005 K. Brookfield, T. Gray, J. Hatchard The concept of fisheries-dependent communities. A comparative analysis of four UK case studies: Shetland, Peterhead, North Shields and Lowestoft. Fish. Res., 72 (2005), pp. 55-69

- Brown, 2004 JE. Brown Economic Values and Cultural Heritage Conservation: Assessing the Use of Stated Preference Techniques for Measuring Changes in Visitor Welfare. Imperial College, London (2004). (Ph.D. dissertation)

- Brown et al., 2003 B. Brown, D. Perkins, G. Brown Place attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: individual and block levels of analysis. J. Environ. Psychol., 23 (3) (2003), pp. 259-271, 10.1016/s0272-4944(02)00117-2

- Camarsa et al., 2012 G. Camarsa, J. Silva, J. Toland, J. Eldridge, T. Hudson, W. Jones, et al.LIFE and Coastal Management. Publications Office, Luxembourg (2012)

- Casakin and Bernardo, 2012 H. Casakin, F. Bernardo The Role of Place Identity in the Perception, Understanding, and Design of Built Environments. Bentham eBooks, Oak Park, Ill (2012)

- Chan et al., 2012 K.M.A. Chan, T. Satterfield, J. Goldstein Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecol. Econ., 74 (2012), pp. 8-18

- Chapin et al., 2012 F.S. Chapin, A.F. Mark, R.A. Mitchell, K.J.M. Dickinson Design principles for social-ecological transformation toward sustainability: lessons from New Zealand sense of place. Ecosphere, 3 (5) (2012), p. 40

- Claesson S. and R.A., 2005 S. Claesson, R.A. Robertson, M. Hall-Arber Fishing Heritage Festivals, Tourism, and Community Development in the Gulf Of Maine. Proceedings of the 2005 Northeastern Recreational Research Symposium, NY (2005), p. 420

- Colburn and Jepson, 2012 L.L. Colburn, M. Jepson Social indicators of gentrification pressure in fishing communities: a context for social impact assessment. Coastal Manag., 40 (2012), pp. 289-300

- Connerton, 1989 P. Connerton How Societies Remember?. Cambridge University Press (1989)

- Coperthwaite, 2006 H. Coperthwaite Maine Working Waterfront Coalition, in a speech during the North Carolina’s Changing Waterfronts: Coastal Access and Traditional Uses. (2006). New Bern

- Creswell, 2004 T. Creswell Place: A Short Introduction. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford (2004)

- Crist, 2004 E. Crist Against the social construction of nature and wilderness. Environ. Ethics, 26 (2004), pp. 5-24

- Davis, 2001 E. Davis Preserving Municipal Waterfronts in Maine for Water-Dependent Uses: tax incentives, zoning, and the balance of growth and preservation. Ocean Coastal Law J., 141 (2001)

- Dewalt and Dewalt, 2002 K. Dewalt, B. Dewalt Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers. AltaMira Press, Lanham, MD (2002)

- Dorwart et al., 2010 C. Dorwart, R. Moore, Y. Leung Visitors’ perceptions of a trail environment and effects on experiences: a model for nature-based recreation experiences. Leisure Sci., 32 (2010), pp. 33-54

- Duran et al., 2015 R. Duran, B. Farizo, M. Vázquez Conservation of maritime cultural heritage: a discrete choice experiment in a European Atlantic Region. Marine Policy, 51 (2015), pp. 356-365, 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.09.023

- EH,, 2007 EH An Asset and a Challenge. Heritage and Regeneration in Coastal Towns, English Heritage (2007)

- FAO, 2013 FAO Fisheries and aquaculture department, Understanding the cultures of fishing communities: a key to fisheries. 2. Cultural characteristics of small-scale fishing communities (2013)

- FAO, 2016 FAO, 2016. 2. Cultural Characteristics of Small-scale Fishing Communities. Fao.org. Retrieved 4 April 2016, from http://www.fao.org/docrep/004/y1290e/y1290e05.htm.

- Farnum et al., 2005 Farnum, J., Hall, T., Kruger, L E., 2005. Sense of Place in Natural Resource Recreation and Tourism: An Evaluation and Assessment of Research Findings. General Technical Report PNW-GTR-660. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station.

- FCR, 2000 FCR An assessment of the socio-economic cost and benefits of integrated coastal zone management. European Commission: 61. Firn Crichton Roberts Ltd, G.S.o.E.S.U.o. Strathclyde (2000)

- Felt and Sinclair, 1995 L.F. Felt, P.R. Sinclair Living on the edge: the Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland. St. John’s, Newfoundland. Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland. Social and Economic Papers no. 21 (1995)

- Ford, 2011 Ford, B. (Ed.), 2011. Introduction. The archaeology of maritime landscapes. Springer, pp. 1–9.

- Forst, 2009 M. Forst The convergence of Integrated Coastal Zone Management and the ecosystems approach. Ocean Coast. Manag., 52 (6) (2009), pp. 294-306, 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2009.03.007

- García-Quijano et al., 2015 C. García-Quijano, J. Poggie, A. Pitchon, M. Del Pozo Coastal Resource Foraging, Life Satisfaction, and Well-Being in Southeastern Puerto Rico. J. Anthropol. Res., 71 (2) (2015), pp. 145-167, 10.3998/jar.0521004.0071.201

- Gieseking et al., 2014 J. Gieseking, W. Mangold, C. Katz, S. Low, S. Saegert The People, Place, and Space Reader. (2014)

- Graham, 2002 B. Graham Heritage as Knowledge: Capital or Culture?. Urban Stud, 39 (5–6) (2002), pp. 1003-1017, 10.1080/00420980220128426

- Griffith, 1999 D. Griffith The Estuary’s Gift. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA (1999)

- Griffith and Mirabilio, 2012 D. Griffith, S. Mirabilio Raising Awareness of Commercial Fishing with Quality Seafood: Best Marketing Practices in South Atlantic Fishing Communities, Survey & Related Findings from the Study: Assessing and Developing Best Practices in Seafood Marketing and Consumption. (2012)

- Guidelines for the Preparation of Serial Nominations to the World Heritage List, 2016 Guidelines for the Preparation of Serial Nominations to the World Heritage List. 2016. Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 15 April 2016, from http://whc.unesco.org/archive/serial-noms.htm.

- Halbwachs and Coser, 1992 M. Halbwachs, L. Coser On Collective Memory. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1992)

- Harvey, 1993 Harvey, D., 1993. From space to place and back again: Reflections on the condition of postmodernity (pp. 3–29). na.

- Harvey, 1996 D. Harvey Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference. Blackwell, Oxford (1996)

- Hausmann et al., 2015 A. Hausmann, R. Slotow, J. Burns, E. Di Minin The ecosystem service of sense of place: benefits for human well-being and biodiversity conservation. Environ. Conserv., 1–11 (2015), 10.1017/s0376892915000314

- Henderson, 1991 K.A. Henderson Dimensions of Choice: A Qualitative Approach to Recreation, Parks, and Leisure Research. Venture Publishing Inc, State College, PA (1991)

- Hernandez et al., 2007 B. Hernandez, M.C. Hidalgo, M.E. Salazar-Laplace, S. Hess Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. J. Environ. Psychol., 27 (2007), pp. 310-319

- How to Request, 2016 How to Request and Submit a Study List Application. 2016. Hpo.ncdcr.gov. Retrieved 10 July 2016, from http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/slhowto.htm.

- Hoyle et al., 1988 B.S. Hoyle, D.A. Pinder, M.S. Husain (Eds.), Revitalizing the Waterfront: International Dimensions of Dockland Redevelopment, Belhaven Press, London (1988)

- Hummon, 1992 D.M. Hummon Community attachment: local sentiment and sense of place. I. Ltman, S.M. Low (Eds.), Place Attachment, Plenum Press, New York (1992)

- Hunziker et al., 2007 M. Hunziker, M. Buchecker, T. Hartig Space and Place–Two Aspects of the Human-Landscape Relationship—In a Changing World. Springer, Netherlands (2007), pp. 47-62

- ICOMOS - ISCEAH - ICOMOS Ethical Statement, 2016 ICOMOS – ISCEAH – ICOMOS Ethical Statement. 2016. Isceah.icomos.org. Retrieved 15 April 2016, from http://isceah.icomos.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=35&Itemid=28.

- ICSF, 2011 ICSF Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries: Towards FAO Guidelines on Marine and Inland Small-scale Fisheries: Report, International Collective in Support of Fishworkers. (2011)

- Inscoe, 2006 D. Inscoe Stakeholder Panel: Identifying Issues and Sharing Perspectives, New Bern. (2006)

- Jacob and Witman, 2006 S. Jacob, J. Witman Human Ecological Sources of Fishing Heritage and Use in and Impact on Coastal Tourism. Proceedings of the 2006 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium (2006)

- Jacob et al., 2005 S. Jacob, M. Jepson, F. Farmer What you see is not always 1252 what you get: aspect dominance as a confounding factor in the 1253 determination of fishing dependent communities. Hum. Organ., 64 (4) (2005), pp. 373-384

- Jentoft, 2000 S. Jentoft The community: a missing link of fisheries management. Marin Policy, 24 (2000), pp. 53-59

- Jepson et al., 2005 M. Jepson, K. Kitner, A. Pitchon, W.W. Perry, B. Stoffle Potential fishing communities in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida: An effort in baseline profiling and mapping. South Atlantic Fishery Management Council, 4055 Faber Place Drive, Ste 201. (2005)

- Johnson et al., 2014 Johnson, T.R., Henry, A., Thompson, C., 2014. In their own word: Fishermen’s Perspectives of Community Resilience, Maine Sea Grant Research-in-Focus Report. Accessible at: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=3&ved=0ahUKEwiFhenenPXLAhVCwj4KHbCuDvsQFggrMAI&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.nmfs.noaa.gov%2Fsfa%2Fmanagement%2Fcouncils%2Ftraining%2F2015%2Fph_in_their_own_words.pdf&usg=AFQjCNH0ojrempQmwOfObj4oXqXe5Vs1sA&sig2=AjsgiOM8lkq9g6K9Ss4TGg.

- Jorgensen and Stedman, 2001 B. Jorgensen, R.C. Stedman Sense of place as an attitude: lakeshore owners’ attitudes toward their properties. J. Environ. Psychol., 21 (2001), pp. 233-248

- Kaltenborn, 1998 B.P. Kaltenborn Effects of sense of place on responses to environmental impacts. Appl. Geogr., 18 (1998), pp. 169-189

- Kerstetter and Bricker, 2009 D. Kerstetter, K. Bricker Exploring Fijian’s sense of place after exposure to tourism development. J. Sustain. Tourism, 17 (6) (2009), pp. 691-708

- Kofinas and Chapin, 2009 G.P. Kofinas, F.S. Chapin Sustaining livelihoods and human well-being during social-ecological change. F. Chapin, G. Kofinas, C. Folke, M. Chapin (Eds.), Principles of Ecosystem Stewardship, Springer, New York (2009)

- Lawrence, 1990 D. Lawrence The built environment and spatial form. Ann. Rev. Anthropol., 19 (1) (1990), pp. 453-505, 10.1146/annurev.anthro.19.1.453

- Lee, 1980 L. Lee The History of Brunswick County, North Carolina. (1980)

- Low and Altman, 1992 S.M. Low, I.I. Altman Place attachment: a conceptual inquiry. I. Altman, S.M. Low (Eds.), Place Attachment, Plenum Press, New York (1992), pp. 1-12

- Malpas, 2008 J. Malpas New media, cultural heritage and the sense of place: mapping the conceptual ground. Int. J. Heritage Stud., 14 (3) (2008), pp. 197-209

- Marsden and Hines, 2008 T. Marsden, F. Hines Unpacking the quest for community: some conceptual parameters. T. Marsden (Ed.), Sustainable Communities: New Spaces for Planning, Participation and Engagement, Elsevier, Oxford (2008)

- Mascarenhas and Scarce, 2004 M. Mascarenhas, R. Scarce “The intention was good”: legitimacy, consensus-based decision making, and the case of forest planning in British Columbia, Canada. Soc. Nat. Resour., 17 (1) (2004), pp. 17-38

- McGoodwin, 2001 J.R. McGoodwin Understanding the Cultures of Fishing Communities: A Key to Fisheries Management and Food Security. FAO (2001), p. 401. Fisheries Technical Paper, Issue

- MEA, 2005 MEA Millennium Ecosystem Assessment: Current State and Trends Assessment. Island Press. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Washington, D.C. (2005)

- Milcu et al., 2013 A.I. Milcu, J. Hanspach, D. Abson, J. Fischer Cultural ecosystem services: a literature review and prospects for future research. Ecol. Soc., 18 (2013), p. 44

- Nora, 1984 Nora, P. (Ed.). (1984–1992). Les lieuxde Mémoire. Paris: Gallimard[Realms of memory. Columbia University Press, New York. 1996–1998.

- NORTH CARO, 2007 North Carolina Waterfront Access Study Committee, Waterfront Access Study Committee Final Report 14 (2007), Available at: http://www.ncseagrant.org/files/WASC_FINAL_web.pdf.

- North Carolina Rural Economic Development Center, 2013 North Carolina Rural Economic Development Center A Supply Chain Analysis of North Carolina Commercial Fishing Industry. (2013)

- Nuttall, 2000 M. Nuttall Crisis, risk and deskillment in north-east Scotland’s fishing industry. D. Symes (Ed.), Fisheries Dependent Regions, Blackwell Science, Oxford (2000), pp. 106-115

- Ome, 2007 Ome, T., 2007-2008. Constructing the Notion of the Maritime Cultural Heritage the Colombian Territory: Tools for the Protection and Conservation of Fresh and Salt Aquatic Surroundings, The United Nations-Nippon Foundation Fellowship Program 2007 – 2008.

- People and Places: Coastwatch, 2016 People and Places: Coastwatch. 2016. Ncseagrant.ncsu.edu. Retrieved 10 July 2016, from https://ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/previous-issues/2014-2/winter-2014/people-and-places-bring-your-own-knives-shucking-at-the-varnamtown-oyster-roast/.

- Pinder, 2003 D. Pinder Seaport decline and cultural heritage sustainability issues in the UK coastal zone. J. Cult. Heritage, 4 (1) (2003), pp. 35-47

- Piriz, 2000 L. Piriz Dependence, modernisation and the coastal fisheries in Sweden. D. Symes (Ed.), Fisheries Dependent Regions, Blackwell Science, Oxford (2000)

- Pollnac, 1988 Richard B. Pollnac Social and cultural characteristics of fishing peoples. Mar. Behav. Physiol., 14 (1988), pp. 23-39

- Pollnac et al., 2006 R.B. Pollnac, S. Abbott-Jamieson, C. Smith, M.L. Miller, P.M. Clay, B. Oles Toward a model for fisheries social impact assessment. Mar. Fish. Rev., 68 (1–4) (2006), pp. 1-18

- Potschin and Haines-Young, 2012 M. Potschin, R. Haines-Young Landscapes, sustainability and the place-based analysis of ecosystem services. Landscape Ecol., 28 (6) (2012), pp. 1053-1065, 10.1007/s10980-012-9756-x

- Proshansky et al., 1983 H.M. Proshansky, A.K. Fabian, R. Kaminoff Place-identity. J. Environ. Psychol., 3 (1983), pp. 57-83

- Ransley, 2011 J. Ransley Maritime communities and traditions. A. Catsambis, B. Ford, D. Hamilton (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology, Oxford University Press, New York, NY (2011)

- Relph, 1976 E. Relph Place and Placelessness. Pion Ltd (1976)

- Robertson et al., 2005 R.A. Robertson, T. Tango-Lowy, E.L. Carlsen Assessment of Tourists and Open Ocean Aquaculture: An Investigation of Isles of Shoals/Rye Harbor and UNH’s Sea Grant Passengers. UNH Sea Grant, College Program, Durham, NH (2005)

- Shackel, 2006 P.A. Shackel Archaeology and Created Memory: Public History in a National Park. Springer Science & Business Media (2006)

- Special staff of writers, 1919 Special staff of writers History of North Carolina. North Carolina Biography, vol. IV, The Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago and New York (1919)

- Spradley, 1980 J. Spradley Participant Observation. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Orlando, FL (1980)

- Stedman, 2003 R.C. Stedman Is it really just a social construction?: the contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Soc. Nat. Resour., 16 (2003), pp. 671-685

- Stedman et al., 2004 R.C. Stedman, T. Beckley, S. Wallace, M. Ambard A picture and 1000 words: using resident-employed photography to understand attachment to high amenity places. J. Leisure Res., 36 (4) (2004), p. 580

- Steelman and Wallace, 2001 T.A. Steelman, R.L. Wallace Property rights and property wrongs: why context matters in fisheries management. Policy Sci., 34 (3–4) (2001), pp. 357-379

- Symes, 2005 D. Symes Altering course: future direction for Europe’s fisheries policy. Fish. Res., 71 (2005), pp. 259-265

- Symes and Phillipson, 2009 D. Symes, J. Phillipson Whatever become of social objectives in fisheries policy?. Fish. Res., 95 (1) (2009), pp. 1-5

- Tango-Lowy and Robertson, 1999 T. Tango-Lowy, R.A. Robertson Assessment of Tourists’ Attitudes Toward Marine Aquaculture: A Preliminary Investigation of UNH’s Sea Grant Discovery Passengers; Bolton Landing, NY. Comp.. Gen. Gerard Kyle (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1999 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium, 1999 April 11-14 (1999). Tech. Rep. NE-269, Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station

- Tuan, 1974 Y.-F. Tuan Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perceptions, Attitudes and Values. (second ed.), Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ (1974)

- Tuan, 1977 Yi.-Fu. Tuan Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis (1977)

- Urquhart et al., 2014 J. Urquhart, T. Acott, D. Symes, M. Zhao Introduction: Social Issues in Sustainable Fisheries Management. Urquhart (Ed.), Social issues in Sustainable Fisheries Management (2014)

- Van Ginkel, 2001 R. Van Ginkel Inshore fishermen: cultural dimensions of a maritime occupation. D. Symes, Phillipson (Eds.), Inshore Fisheries Management, Kluwer, Dordrecht (2001)

- Wang and Burris, 1997 C. Wang, M.A. Burris Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav., 24 (3) (1997), pp. 369-387

- Worm et al., 2009 B. Worm, R. Hilborn, J.K. Baum, T.A. Branch, J.S. Collie, C. Costello, M.J. Fogarty, E.A. Fulton, J.A. Hutchings, S. Jennings, O.P. Jensen Rebuilding global fisheries. Science, 325 (5940) (2009), pp. 578-585

Consulted websites

- California Na, 0000 California Native Americans’ website: http://www.nahc.ca.gov/sp.html#executivesummary.

- Census Viewer, 0000 Census Viewer website: http://censusviewer.com/free-maps-and-data-links/.

- National Regi, 0000 National Register of Historic Places: http://www.nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com/.

- NOAA, 2013 NOAA, Maritime Heritage Program, 2013: http://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/maritime/cultures.html.

- NOOHEROOKA 30, 2013 NOOHEROOKA 300 ECU website, 2013: http://www.ecu.edu/cs-admin/news/nooherooka.cfm.

- North Carolin, 0000 North Carolina Office of State Archaeology: http://www.archaeology.ncdcr.gov/.

- North Carolin, 2007 North Carolina, Sea Grant 2007: http://www.ncseagrant.org/home/coastwatch/coastwatch-articles?task=showArticle&id=441.

- Provincial Ar, 0000 Provincial Archives or New Brunswick: http://archives.gnb.ca/Exhibits/archivalportfolio/TextViewer.aspx?culture=en-CA&myFile=Fisheries.

- The Carolina, 0000 The Carolina Algonkian: http://homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~jmack/algonqin/algonqin.htm.

- Town of Calab, 0000 Town of Calabash NC website: http://www.townofcalabash.net/.

- UNESCO, 0000 UNESCO: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/brasilia/culture/culture-and-development/culture-in-sustainable-development/.