Robinson Crusoe’s translation and spreading of marine spirit in pre-modern China

College of Humanities, Shanghai Ocean University, China

Abstract

Western marine literature classics were translated into Pre-modern China, and Robinson Crusoe is one of the most representative. Various Chinese versions were rendered with the political and educational push of the time. The translation and introduction of the noted classic played a key role in the spreading and formation of the Chinese marine spirit, thus profoundly inspiring Chinese readers. The adventure of Robinson on the wild island provided a powerful spiritual impetus for those Chinese with lofty ideals. It is without doubt that the translated novel conforms to the spirit and demand of the time, and voices the inner mind of the Chinese, which is the very reason why it has been loved and accepted by the massive Chinese readers and influenced them so much ever since.

Keywords

Robinson Crusoe, Versions, Educational novel, Adventure novel, Marine spirit

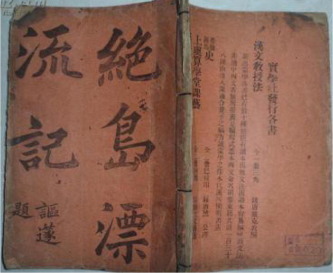

Translated literature in Pre-modern China presented a magnificent view. Most western countries are marine nations; therefore, in western literature most outstanding literary works are shining with the spirit of the sea. Western marine literature classics were translated into Pre-modern China, and Robinson Crusoe is one of the most representative. Robinson Crusoe, the masterpiece of Daniel Defoe is known almost all over the world, and regarded as a realistic marine adventure novel. The book is so well received by the readers for its adventurous plots on the island and readable language for the common Englishmen that wherever there is the Bible, there is a copy of Robinson Crusoe. For these, there are not only many full translated adventure of Robinson Crusoe in Chinese for adults but also lots of Children’s versions. The translation and introduction of the noted classic has played a great impact on the Chinese society. The hero was a man full of intense curiosity for nature and human society, screaming for personality independence, and attempting to verify his enterprising spirit through battles with severe living environment. The marine spirit embodied by Robinson coincided with the anti-feudalism and development of personal freedom of the Chinese people of that time; furthermore, it played a key role in the formation and spreading of the Chinese marine spirit, such as martialism and overseas adventure, etc., thus profoundly inspiring the Chinese readers (see Fig. 1).

Introduction of Defoe and his Robinson Crusoe

Daniel Defoe (1660–1731) was one of the founders of the English realistic novels, and gained the name “the father of the English novels” (Qishen and Zhu, 1981:93). He was born in a merchant family, spent many years in business during his youth, and then became a soldier, having been to Spain, Italy, France, Germany and other places. He also engaged in political activities, actively advocating social reforms. The rich life experience offered the essential ideas and skills for his literary creation (see Fig. 2).

Defoe started the job of writing Robinson Crusoe when he was almost 60, which is his first novel and the best (Anixter, 1981:198). Later, he also wrote in succession Captain Singleton, Moll Flanders and many other novels. But today Defoe is chiefly remembered as the author of Robinson Crusoe. This masterpiece appeared in the year of 1719, and after its publication politicians, economists, preachers, literary historians and critics made comments on it from various perspectives. Robinson Crusoe was based on a real adventure. In 1704, A Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk was marooned on the island of Juan Fernandez in the Atlantic and lived there quite alone for four years. The story of his adventures aroused great public attention and several records of his solitary life on the island appeared in different publications. With the real story as the basis, Defoe created the noted novel. In the book he took the hero’s 28 years living alone on the island as the main clue, narrating the unusual and exhilarating experience by Robinson himself. The story has three sections: The first part is concerned with Robinson’s three sailing experiences away from home; the second specifically describes the ship wreckage that Robinson underwent and the marooning on a lonely island, including his hunting, cave seclusion, engagement in agricultural production, which lasted twenty-eight years. The third part involves that he finally got relieved and returned to England. The second part is the main body of the novel (see Table 1).

| Translator | Version’s name | Press | Publishing time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shen Zufen 沈祖芬 | Jue Dao Piao Liu Ji 绝岛漂流记 | Shanghai Kaiming Bookstore & The Civilized Bookstore 开明书店、文明书店 | 1902 |

| Lin Shu & Zeng Zonggong 林纾、曾宗巩 | Lu Bin Xun Piao Liu Ji 鲁滨孙漂流记 | Shanghai Commercial Press 上海商务印书馆 | 1905/1913/1914/1917 |

| Cong Kan 从龛 | Jue Dao Ying Xiong 绝岛英雄 | GuangYi Bookstore 广益书局 | 1906 |

| Xiao Bo&Hongfu 小波、红绂 | Wu Ren Dao Da Wang 无人岛大王 | Unknown | 1909 |

| Zhou Di 周砥 | Jue Dao Ri Ji 绝岛日记 | Qunyi Publishing House 群益书社 | 1910 |

| Sun Yuxiu 孙毓修 | Jue Dao Piao Liu 绝岛漂流 | Shanghai Commercial Press 上海商务印书馆 | 1910 |

Literature is in essence humanism, always following the tides of the era. Defoe’s works evidently demonstrate the atmosphere of the times – the 18th century, when British society was experiencing great and profound changes. Along with the fast economic development, the British bourgeois of the middle class also grew rapidly. As one of the members of the new class, Robinson was a representative figure in the rising period of capitalism; hence, the novel Robinson Crusoe can be viewed as a miniature of the rising British bourgeoisie. These were the people who had known poverty and hardship, and most of them had obtained their present social status through hard work. They believed in self-restraint, self-reliance and advocated human labor instead of waiting and praying. Though some of them behaved themselves and made every effort to obtain an uneventful life, but more aspired to involve competition, attempt exploration in the outside world, and meet the challenges of the various forces. Robinson was one who specifically and fully embodies the idea. “The significance of Robinson Crusoe is that it records the burgeoning of quite a few intellectual and social traits that latter became the epochal features of Western Man, such as the belief that material improvement is entwined with spiritual advancement, alongside the rise of capitalism, individualism, and European supremacy.” (Li’an, 2007:25–48).

Robinson Crusoe is closely related to the unprecedented Enlightenment Movement in the history of European. The enlighteners emphasized reason (or rationality), equality and science, and advocated universal education. They believed that to establish an ideal society, it was of significance to inspire people’s hearts by resorting to the eternal rationality, and the scientific and cultural knowledge building on it. In the field of literature, the enlighteners held that rationality and reason should be the only and final cause of any human thoughts and activities. They advocated the realistic literature which was judged in terms of its service to humanity. The newly rising literary form, namely, British realistic novels, predominated in that period, which gave a realistic presentation of life of the common English people and the middle class. These novels stress the objective, specific and historical description of reality, and emphasize the reality of the relationship between character and environment. The novelists of this period understood that the job of a novelist was to tell the truth about life as he saw it, so they spoke the truth with an uncompromising courage which explained the achievement of the English novels in the 18th century. These novels created the image of enterprising Englishmen, typical of the English bourgeoisie of that time. Among the pioneers Daniel Defoe was one of those most representative and influential.

Translation of Robinson Crusoe in pre-modern China

The Opium War in 1840 opened the long closed door of the Qing Dynasty with violence. The pre-modern China was invaded and exploited, and meanwhile various western thoughts flooded in. The once stable cultural system began to collapse and the traditional ideology was impacted. After the defeat in the Sino-Japanese War from 1894 to 1895 Chinese intellectuals realized that the most possible and efficient way to save the country was to spiritually enlighten the Chinese people. During the time a surge of translation occurred throughout the whole country. Literary translation, especially novel translation became an obvious trend. Translators hoped to find the secrets to make the country powerful and awake the country people by modeling the western countries. The translations at that time served right to the social need.

The first Chinese version of Robinson Crusoe translated by Shen Zufen nicknamed “the crippled young man of Qiantang” in the late Qing Dynasty, was published by Shanghai Kaiming Bookstore in 1902 with the title of Jue Dao Piao Liu Ji (《绝岛漂流记》).

After the first introduction, several other translators carried on the translation and published other versions on newspapers, such as Robinson Piao Liu Ji Yan Yi (《鲁滨孙漂流记演义》) in The Mainland Report (《大陆报》) under anonymity, The People’s Wail (《民呼时报》) which was a bourgeois paper belonging to the late Qing revolutionary bourgeois published the story of Robinson Crusoe, and the Chongqing paper Guang Yi Newspaper (《广益丛报》) reprinted the story from The Mainland Report.

In addition to newspapers, the story was also published in the form of books. The most famous one is Robinson Piao Liu Ji (《鲁滨孙漂流记》) by Lin Shu and his collaborator Zeng Zonggong. The book was published by Shanghai Commercial Press (上海商务印书馆) in 1905. Since then Lin’s version has been compiled into ShuoBu Series (《说部丛书》) and Lin Yi Novel Series (《林译小说丛书》) and published many times (Tarumoto, 2002:432–433). At the same time there were some other translations such as Jue Dao Ying Xiong (《绝岛英雄》) by Cong Kan in 1906, Wu Ren Dao Da Wang (《无人岛大王》) by Xiao Bo and Hong.

Fu in 1909, and Jue Dao Ri Ji (《绝岛日记》) by Zhou Di in 1910. Among these versions in Pre-modern China, only the Lin’s version is a complete translation of Robinson Crusoe without much abbreviation and retains almost all the contents and structures as the original story, while the second translation is composed of 16 chapters in the traditional Chinese novel form and is translated without telling readers on which version the translation is based. The third is an abridgement from Japanese version and the fourth a work rendered from parts of Robinson Crusoe published in different journals. Lin Shu was a famous translator in pre-modern times. He translated more than 180 foreign novels with elegant and fluent style and opened the Chinese people field of vision and promoted the revolution of Chinese literature. Lin Shu translated foreign novels in order to go with the social thougts of “Learning from the west ” and to serve ” the Movement of Making Political Reform” at the end of the Qing Dynasty.

In China, Robinson Crusoe was regarded as one of the western classics, teenagers’ book and English reading material for readers before the modern times. During the later twentieth century, there were more than fifty versions, including the full translation versions, abridged versions, rewritten versions, English-Chinese bilingual versions and painting versions of Robinson Crusoe for children since it was regarded as an inspirational book besides its adventurous and appealing plots for teenagers to enjoy the growth experience.

The constructing and spreading of Robinson Crusoe’s marine spirit

Robinson Crusoe was introduced into China, being marked as “educational novel” or “adventurous novel “. Then China was undergoing a rough time, full of troubles and disasters, and with the invasion of the foreign powers the Chinese began to be awakened. The effect and influence of Robinson Crusoe’s translation was closely related to the political reality and historical background of China. It was the particularity of the time that determined the reception and reaction of the readers. So in a sense the translation and introduction of Robinson Crusoe was just a tool used for the political reform of the time. In Robinson Crusoe, Defoe traced the growth of Robinson from a naive and artless youth into a shrewd and strong-hearted man, tempered by numerous trails in his eventful life. The realistic account of the successful struggle of Robinson single-handedly against the hostile nature formed the best part of the novel. Robinson is here a real hero: a typical eighteenth-century English middle-class man, with a great capacity for work, inexhaustible energy, courage, patience and persistence in overcoming obstacles, in struggling against the hostile natural environment. He is the very prototype of the empire builder, the pioneer colonist. He toils for the sake of subsistence, and the fruits of his labor are his own. In describing Robinson’s life on the island, Defoe glorified human labor and the Puritan fortitude, which save Robinson from despair and were a source of his pride and happiness.

In the preface of the first Chinese version translated by Shen Zufen, the distinguished publisher Gao Fengqian advocated: “We’ll take the translation as a medicine to cure the sick Chinese, motivating their venture and aspiration, for there are many who believe that the European are superior to us Chinese. Rousseau, the French thinker, once said that among all the textbooks that could play the educating role this one should rank the first. In Japan the book has also been translated into Japanese, with the title of Adventures on Wild Island. Here we borrowed their way of entitling and did the translation based on the original work in order to uplift the young people’s mind in China.” We can see the words “Do not forget national humiliation” written by readers in the left margin of the cover in the book. With obviously strong political purpose, and then labeled with adventurous story to inspire people’s adventurous spirit, the novel was listed among the classic literature works to meet the great demand from readers of all sectors of the Chinese society. On October 27, 1902, the Shanghai paper Universal Gazette (《中外日报》) published an ad for the translated adventurous novel: “The novel, with multiple chapters, is full of amazing and scaring events, which are extremely touching to our heart and help a lot to inspire the people’s mind.”

Also from the ads of various papers and magazines of that time we can see that Robinson Crusoe, designated as “Textbook accredited by the Educational Department”, “Reading materials accredited by the Educational Department”, was used as supplementary teaching materials for elementary and secondary schools. In Lin Shu’s translation, the great author Qian Zhongshu said Lin’s translation was excellent, and his invisibility as the translator guided readers to appreciate the original text and obtained the essence of it (Zhongshu, 1985:26). And on the front cover of the first issue of The Chinese Educational Review (《教育杂志》) in May 1909 were printed words “Enlightening reading materials accredited by the Educational Department” to show the readers that the book was beneficial to children, and suitable for the enlightening reading to the children by teachers. On June, 2, 1909, Tianjin newspaper Ta Kung Pao (《大公报》) carried an ad for books published by the Commercial Press. Of the books labelled as “Enlightening reading materials accredited by the Educational Department” were Robinson Crusoe and other western literary works. The ad specifically indicated the educational role of novels and pointed out novels are used for educational purposes, by which the national spirit can be uplifted. To arouse the spirit of self-criticism and self-innovation among the Chinese people, the translators rewrote and changed the language of racism in the original into the language with national character in the translations by selectively preserving, deleting and adding some information.

Although there were no first-hand materials from elementary and secondary schools testifying the teaching effects, the pre-modern educator, great writer Ye Shengtao’s own recounting was rather convincing.

Diary of June 10, 1912

The second Self-cultivation lesson was concerned about personal independence, and I told the adventures of Robinson on the islands to the students who burst into grinning. Unheard-of stories are always funny, which is a common psychology, especially with children (Ye Shengtao, 1997:16).

Robinson’s firm and indomitable character when faced with difficulties and hardships was just what the Chinese people of that time needed to learn and possess. In such a sense the translation of the novel was the very affirmation of individual heroism in a time when the country was declining and the fate of the whole nation was going down. Its aim was to urge the people to rise and fight, to be patriotic, to venture and cultivate the martial spirit. The translation of Robinson Crusoe dramatically inspired the fighting spirit of the Chinese. With the increasing vigilance, their marine consciousness of was aroused, and they were more alert about possible invasion of foreign powers from the seas, and every minute on guard against the national subjugation and genocide. The adventure of Robinson on the wild island provided a powerful spiritual impetus for those Chinese with lofty ideals. It is without doubt that the translated novel conforms to the spirit and demand of the time, and voices the inner mind of the Chinese, which is the very reason why it has been loved and accepted by the massive Chinese readers and influenced them so much ever since.

References

- Anixter, 1981 A. Anixter English Literature Survey. Beijing People’s Literature Publishing House, Beijing (1981)

- Li’an, 2007 L. Li’an Revamping canonical novel: The case of Robinson Crusoe. Br. Am. Liter. Rev., 6 (1) (2007), pp. 25-48

- Qishen and Zhu, 1981 Y. Qishen, S. Zhu Selected Readings in British Literature. Shanghai Translation Publishing House, Shanghai (1981)

- Shengtao, 1997 Y. Shengtao Ye shengtao diary. Shanxi education publishing house, Taiyuan (1997)

- Tarumoto, 2002 T. Tarumoto The catalog of new additions to the late Qing and early Republic novel. Qilu Publishing House, Jinan (2002)

- Zhongshu, 1985 Q. Zhongshu A Collection of Seven Compositions. Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House, Shanghai (1985)