Conceptual development of the trail methodology for the preservation of intangible maritime heritage: A case for the Adriatic coast and islands

University of Split Croatia, Department of Philosophy, Adriatic Maritime Institute, Kneza Mislava 16, Zagreb 10000, Croatia

Abstract

In the Adriatic, the importance in tourism of the small rowing and sailing boats, like the gajeta and other heritage vessels, is clearly relevant, as icons of heritage boats adorn brochures, logos, and their names are bequested to hotels and restaurants. As a symbol, the gajeta stands for the heritage of the island, and the ethics of the place; these constitute an intangible treasure which highlights the lifestyle of the agriculturalist society. However, the distinct experience of the gajeta, or other local boats as a relevant form of tourist activity, is largely missing in the offerings of local tourist information centers and nature parks where they reside. This paper outlines a heritage trail interpretive strategy, which would create a network supporting small local tourist venues that showcase intangible maritime heritage of the coast and islands. The methodology creates an alterative to what is primarily leisure-based tourism that Adriatic counties like Croatia are experiencing in all but the largest cultural monuments and ecological reserves which provide avenues for community-based ecological management in remote regions.

Keywords

Maritime, Intangible, Heritage, Adriatic, Croatia, Tourism, Gajeta, Falkuša, Community-based management, Adaptive co-management, Experience economy, Integrated rural tourism (IRT)

It is at the local, community level where successful trail networks begin.

Introduction: The concept of a heritage trail

The Croatian coast and islands from the south at the border with Monte Negro to the northern border with Slovenia spans more than 1777 km. Croatia has more than 1200 islands. When the coastlines of the islands and mainland are combined, this 5790 km makes ¼ of the Mediterranean total. 66 islands have settlements of varying sizes, each with a rich cultural diversity that can be found along the way. Different coastal regions and islands have distinct cultural traits that can be seen, in speech, as on the island Vis where the inhabitants of Komiža and Vis town use a different common dialect, and dress and food are also distinctive for each settlement in the archipelago.

The differences in culture can also be found in the varying types of rowing and sailing boats found along the coast, heritage vessels.1 Each locality has developed its own type of distinct watercraft, as with the two types small sailing boats, the gajeta from Murter (Photo 1) and Korčula, the small cargo boat, bracera from Brač (Photo 2), the offshore fishing vessel, falkuša from Komiža (Photo 3), and the utilitarian skiff, batana of Rovinj (Photo 4). There are many more types of vessels that exist and are still being used along the coast, but these are just a few of the more prevalent examples.

This class of vessels represent a form that may be rowed or sailed under varying conditions. The rotund hull shape and double ended design characterize the boats, which range between 5 and 12 meters. These types have been historically family owned which insulated them from transitions in technology and economics that replaced the larger ships of the region. The boats were and are used as multipurpose watercraft with a myriad of function. Of these mentioned here, all but the bracera, exist around the coast and island in great numbers, now with added engines, but performing the same tasks they have done for centuries (Bachich, 1970).

Each one of these vessels represents a craft that has been born from the local environmental conditions, as well as the economic role and purpose the vessel holds within the society. The shapes, materials, and technology that integrated these environmental and societal forms have created a diversity of craft that is unique not only in the Adriatic, but also in many bodies and waterways around the globe.

Presently, there is not one unifying museum in Croatia such as a national museum that represents the maritime cultural resources of the entire country, and undoubtedly this would be difficult with such a broad range of groups to represent accurately. This would also be counter productive to the preservation of intangible heritage. Removing a vessel from its locality would inhibit the intergenerational transition of intangible heritage, which is passed down within the locality of the vessels functional role (Bender, 2014).

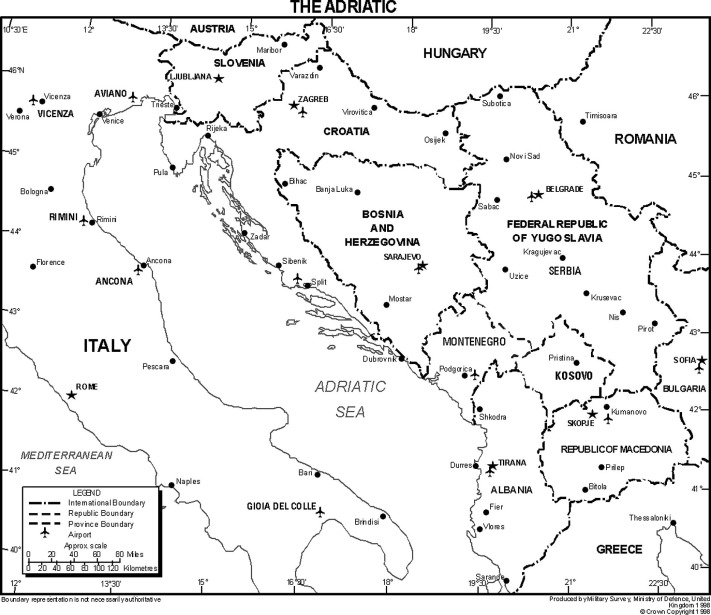

It is for this reason that the Adriatic maritime region would be an excellent candidate for a national theme trail. A string of relevant sites along the coast and in the islands would allow the boats and the associated heritage to be curated by the local inhabitants, who have for centuries have built and operated these vessels in the places where the intangible knowledge, seafaring, and maritime ecology has accumulated (Map 1).

The heritage trail is a methodology that would allow the linking of maritime sites like these areas, which have small fleets of heritage vessels that exist within their locality. The preservation of the vessel, and the cultural heritage surrounding it, combines not only the preservation of artifact, but also the conservation of the environment and relevant trades like blacksmithing, woodworking, and associated arts like poetry, dance, and cuisine where they reside.

In addition, the maritime heritage trail methodology creates access to authentic sites of maritime heritage through an experiential rather that a passive type of observation. The passive observation as in a museum setting is only a one sided affair, which allows the outsider to view objects without engagement from the local community in which they visit. The experiential model would require local providers to create opportunities to experience and participate in events or activities that are informed by local cultural aspects of maritime culture for example a sailing excursion on a historic vessel from the islands. This activity creates an engaging cultural experience for those involved. The experiential tourism would in turn support local heritage preservation though the training in the maritime arts in which these activities are based.

The maritime heritage trail would link sites of coastal and island heritage. This would benefit local groups in several ways. While one historic vessel, or heritage site along the coast would not be considered a proper tourist destination, the heritage minded tourist would more likely be attracted to an experience that could be expanded to an itinerary of heritage sites around the islands, complete with self-guiding resources and community-based infrastructure. By providing a support network, unifying marketing and messaging, and providing training for local groups, a trail network would bring resources into the hands of the often overlooked populations which are in the most need of support. Furthermore, the network would also inspire international cooperation, as it could be expanded in other countries in the Adriatic and Mediterranean.

A network that allows partner organizations access to a larger marketing and branding would help to create an influx of tourism to these sites, many of which are in the process finding ways to support their cultural resources though local preservation programs and cultural tourism. This in turn would place economic value on living heritage. This valuing, symbolically or economically, of heritage is essential for trades and arts to prosper within the society that supports them. The maritime trail would help these organizations to link with one another at the same time provide a means for a heritage tourist economy to thrive in an already busy tourist industry along the coast and island of the Adriatic.

The decentralized approach of the trail methodology would also allow the local organizations the autonomy to build, guide, and prepare their sites respectively of one another, thus following best practices for integrated rural tourism (IRT). Local governance was highlighted in the research of Cawley and Gillmor (2008), who found to be as a key factor for success in IRT. While the coastal maritime region is not necessarily entirely rural, borrowing from the best practices of this community-base structure would allow urban and rural partners equal benefit.

It is important to consider that through the process of bringing in tourists in closer to the local cultural elements, especially in remote islands that there will likely be impacts to the socio-cultural and environmental sustainability of the islands. As Sheldon (2005) points out, there are several necessary approaches to overcome challenges in island tourism many of which echo sentiments of IRT. These include long-term stakeholder-involved planning, empowerment of the island community and culture, and environmental management, as well as visitor, transportation and marketing considerations that eliminate overuse and system stress.

Briedenhann and Wickens (2004) discuss the clustering of activities in rural tourism as an appropriate method. Idealizing this notion could not only capitalize on existing tourism networks, but also expand the types of activities and cultural offerings presented in the islands. Having a centralized leadership structure, or hub that is managed by each of the island’s udrugas or organizations could be a unique opportunity to deliver tours to the islands, harbor cruises, and onshore activities and products, some of which could be the agricultural products produced by the families themselves.

Each site on the heritage trail route could have several activities be prepared for the visitors to participate in during their visit. An indoor museum paired with boat rides, as well as dance and arts would create not only an interesting presentation for visitors, but also provide opportunities for young people to be involved in the planning and preparation of such activities. The practice of sailing, steps of a dance, or notes of a song to be learned, through the process of preparation, the intangible aspects, would be passed down to the younger generation.

Utilizing the maritime heritage trail methodology would be a way to allow tourists to experience living cultural resources of boatbuilding, sailing and fisheries, as well as a way to preserve the local intangible and ecological heritage associated with the vessels that they support. Integrating local parks and preserves would create a connection with the local ecological resources, as well as strengthen the cultural dimensions to the conservation area in which the community is based. This in turn would create opportunities for the heritage vessels to operate in the aquatorium for which the vessels were built, a natural partnership.

The intent of this iteration of the heritage trail would be to unify several rural sites, parks, hotels, and existing tourist infrastructure, in order to pool resources and create a theme that the maritime tourist would recognize at each venue, benefiting the localities that they represent. Being focused on living cultural resources as well as existing heritage craft not only helps to preserve the trades associated with maritime arts, but also helps to unify local coalitions in the common goal of preservation and conservation. Locating the preservation effort within its local environment creates a dimension of ecological integration that would not be present in other localities.

Typology of maritime heritage trails

The use of maritime trails is prevalent in several countries including the United States, specifically with the implementation of maritime trails in Florida, South Carolina, and the Great Lakes region. Many of these trails have the purpose to bring together several elements of marine cultural resource management, specifically shipwrecks and objects, which are deemed to be a part of the cultural resources of the state or the nation. However, other types of trails, paths, walks, and routes come in many themes around the world. There are several thousand such trails that exist in varying forms. Nature trails, harbor walks, and historic routes all share similar attributes, which must be taken into consideration when planning. These factors are the mode in which the visitor travels, the scale of its objectives, and possible integration into local trails (Silbergh et al., 1994).

The US National Parks and the Department of the Interior have declared guidelines that encompass the handling of such sites and built cultural resources; The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties and Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes.2 This document is organized into four parts, preservation, rehabilitation, restoration, and reconstruction. Each section illustrates how to apply these four treatments to cultural landscapes in a way that meets the standards; the cultural landscape approach. National bodies, such as the federal government responsible for management of the trails, must follow these guidelines in order to ensure the highest level of artifact conservation. Integration into the common theme must be met to ensure consistency throughout the distance of the path.

In two particular states, New Jersey and Maine, the maritime trails focus on shore-based maritime artifacts and culture resources with a more social or environmental approach. The New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail retains a network of sites that run along the coast and barrier islands. The wide range of sites include, wildlife refuges, lighthouses, historic marinas, maritime museums, and historic sailing vessels. It also includes areas relevant to living heritage, for example, sailing vessels, shipbuilding, and fisheries sites still in service (Sebold and Leach, 1991). Maine’s Down East Fisheries Trail combines museums, fish hatcheries, and scientific institutes with maritime trade locations and harbors, highlighting the region’s rich history of fishing and aquaculture.

Maine’s Down East Fisheries Trail website states that marine resources sustain the culture and economy of Maine and “the trail builds on these local resources to strengthen community life and the experience of visitors”.3 The combination of a community building exercise, which helps to present the fisheries economy in a positive light, while enhancing the experience of the visitor are social aspects that the Maine and New Jersey trail projects would share in common with the proposed trail for the Adriatic maritime region.

Just as the adoption of similar guidelines used by the US National Parks and partner entities regarding the preservation of cultural landscapes, approved guidelines could be used by member organizations in Adriatic region. While there are no specific guidelines to support the conservation of intangible heritage with regards to trails in the US, the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage presented by UNESCO4 could provide additional direction for the conservation and protection of the aspects of the proposed trail’s intangible treasures.

Artifacts and cultural heritage sites should integrate into the cultural landscape providing the visitor and local providers with the opportunity to not only present local heritage as ‘built’ in the way of preserved, rehabilitated, restored, or reconstructed buildings or objects, but also as living practices that are taught and learned within the local cultural sphere. The combination of these two avenues of tangible and intangible presentation allows the visitor and community members to best experience and preserve the local cultural fabric within the dynamics of this multinational cultural exchange, which is tourism.

Methodology of implementation

Thus far, in the philosophical approach, the creation the trail project can be said to traverse the line between the preservation of local tangible and intangible heritage, and creation of tourist offerings, with the best possible approach formed by having equal emphasis on each side of the equation.

Strengthening local sites and offerings will serve to entice the tourist to visit. For example, during the boat races and festivals on the island Murter, there is a significant draw for tourists to come during these weeks in the fall when the normal tourism has dropped significantly. The role and purpose of the race is primarily for locals to participate, but tourists and photographers come from far and wide to see the magnificent fleets ride the wind. By focusing internally and making a festival to help preserve local intangible knowledge, the people of Murter have also enlivened the town during a slower period, thus lengthening the shoulder season of the tourist economy. To understand this interaction between local inhabitants and extra-local visitors a further discussion is required.

In order to facilitate the development of a heritage trail effectively, a discussion must include what these offerings are, who views them, and how they will be presented and understood by the people who present them. The term tourism was first used in the late 17th century. Since then, tourists have made it a point to visit every place on the globe, some in the name of adventure, others in leisure and even more in the name of academic research, such as the anthropologists and biologists. The ease of mobility and recent inclusion of technology has continued do develop this market making it today a more than 900 billion dollar industry (Fîntîneru et al., 2014).

There has been significant research into the study of tourism. In this thorough review, the Anthropology of Tourism, Stronza (2001) states that the research can be divided into two halves; one that focuses on the impacts of the locals and the other that investigates the origins of tourism itself. This seems to be a common theme, not only the research, but also in the methodology of the creation of the destinations for tourism itself. The focus seems to be entirely one sided. Stronza states “exploring only parts of the two-way encounters between tourists and locals, or between “hosts and guests,” has left us with only half-explanations” (pg. 262). It is with this in mind that the formation of a maritime heritage trail must be created following this dialectic.

Stronza states that the research itself has been somewhat contradictory. In some cases local values diminished, while others were strengthened. Some areas were more robust following influx of tourist economy, while others became dependent on tourists for their livelihood. Stronza shows that there are multiple forces at play not just between tourists and communities, but also between the positive and negative effects of participants and facilitators. While it is not possible to make a one size fits all program on a national level, it is important to build on the current research and examine best practices in the formation of community-based touristic enterprise.

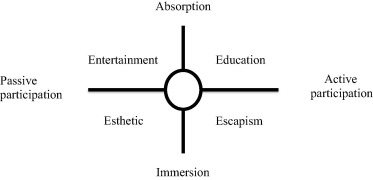

The research of Pine and Gilmore (1998) shows a three level evolution of the interactions between providers and consumers though engagement. The interactions can be said to operate from product, to service, then to experience. Pine and Gilmore concluded by focusing on interactions between providers and participants, engagement and outcomes were more substantial when the providers created an experiential mode for the exchange to take place. With the ‘product,’ the interaction can be cursory just allowing enough exchange to complete the task, while ‘experience’ is a more holistic approach to interaction that happens on multiple levels. Experience is defined in four distinct realms (Fig. 1), and creates value for both provider and customer.

Hayes and MacLeod (2007) employ this insightful methodology to analyze English heritage trails of which a random 10% sample size of the approximately 1300 heritage trails in the UK were evaluated. The conclusion is reached that the heritage trails are being produced and packaged as products rather than services or experiences. Heritage trails have potential to enhance the visitor experience, but are often left short by not using an integrated strategy that employs all aspects framed by the Pine and Gilmore model (Fig. 1).

“Trails that are developed to incorporate both educational and entertaining themes and materials and which immerse the participant in the story have potential to hit the ‘sweet spot’ at the center of the Pine and Gilmore model and become truly compelling experiences rather than being simply functional products.”

(Hayes and MacLeod, 2007, pg. 50)

This type of integrative strategy not only enhances visitor experience, but also bolsters local preservation efforts though the practice of an inclusive experiential program that encompasses several aspects of local lifestyle, culture, and identity. For example an experiential model could include a visit to a local museum, followed by a fishing expedition with local fisherman on a heritage vessel, culminating in the opportunity to eat the fish just caught, and hear local songs, stories, or poetry about the sea. Each of the participants, the tourist and provider, is engaged in the production of the experience. The experiential model creates a proactive approach to changing the relationship in tourism in the local arena from passive providers to active facilitators, which would encourage the preservation of local intangible heritage.

There has been considerable research into the experience model in tourism including Oh et al. (2007) who developed a conceptual model for a quantitative analysis of the experience economy and its impact in a regional setting. Also the work of Morgan et al. (2009) deliver a qualitative analysis of three destinations. These works and others point to best practices as well as methodologies for evaluation that will be critical in the formation and evaluation of the heritage trail as methodology for intangible heritage preservation.

In the formulation of tourist offerings, the destination is key for enticement of the traveler to come to distant places. In the past, this idea of a destination has been inclusive of the ‘products’ that the tourist would like to consume not the ‘experience’. The term destination further expresses representation of a static approach to tourism. Arrival at the destination is a pause in the itinerary, which by all practical purposes is completely dynamic in nature.

To fully understand and engage the traveler, they must be redefined as people in motion. The trail methodology encourages the traveler to see the trail as a continuum of places, events, and experiences, and therefore engage in a deeper manner. These distinctions can further help to eliminate the processes of viewing tourism as a product rather than an experience. The creation of the trail as a functional body in which the tourist is engaged helps to further this production of dynamic tourism rather than static observation. The richness of experience as opposed to passive viewing of an object provides the facilitator opportunities to ‘remember’ parts of intangible heritage and therefore is an act of preservation. Each place itself can be wrapped in experience, whether the hotel, or restaurant, activity, or museum, each part can create authenticity from the very fabric of the cultural existence of the place and its tangible and intangible relics.

In earlier research, Cohen (1979) had already defined the experiential mode of tourism as one of five modes that tourists use to engage the citizenry and environment of foreign lands. Revisiting Cohen’s tourist modality or typology can help to define an appropriate methodology for the creation and collaboration of the trail atmosphere.

The five modes as described by Cohen (1979, pg. 183) are:

- (1)

- Recreational mode

- (2)

- Diversionary mode

- (3)

- Experiential mode

- (4)

- Experimental mode

- (5)

- Existential mode

The recreation mode is most akin to the type of tourism that Croatia experiences on the beaches, bays, and islands at the present moment. Although as Cohen describes the diversionary mode is similar to recreational tourism but has a certain brand of escapist modality for those who wish to come to ‘forget’ the life that they live and enjoy the foreign diversion, through the beach, fun and sun and includes a passive observation of ‘viewed’ culture.

The experiential mode as Cohen describes serves to seek out ‘authenticity’ in the foreign context. Cohen states, it is “the novelty of the other landscapes, life ways, and cultures which chiefly attracts the tourist” (pg. 188). The fourth designation of tourism is experimental. This chiefly describes travelers who are seeking out religious centers and may be for all practical purposes as Cohen describes ‘drifters’ seeking to redefine their own identity though the experience of others.

While the Cohen typology of tourism may help to understand these modes, it is important to note the Pine and Gilmore model of experience includes escapist and entertainment modes in the formulation of the experiential model, and have for the most part synthesized Cohen’s modality into one composite mode of ‘experience’. When the experiential mode is applied to tourism, the traveler and facilitator may use varying degrees of each modality to create or bring to life the mode in which the travelers seeks.

The fifth typology, the existential mode, does not fit as neatly into the Pine and Gilmore characterization. In the Cohen model the existential mode is used to describe travelers who are not seekers, but for all practical purposes are aligned fully in such a way that they identify completely with the group in which they are visiting.

Existential tourism, as Cohen described, is typified by the tourist who returns to visit their home land of seeking out their roots, or as Gonzalez (2008) shows, is someone one who is interested in the skills of an area with the intent on learning those skills so they can be transported back to their home or locality. By looking at a similar example from Spain, and a case study of Japanese tourists coming to learn Flamenco Dance, González found that the emphasis on intangible tourism, allows the tourist to seek out ‘authenticity’ in the local sphere and take the experience back to their home. This ‘transported’ authentic knowledge can then be utilized in local sub-cultures that demand authenticity from its participants.

The employment of these characteristics of an existential tourism model could be used equivocally in the maritime realm, allowing those interested in boats, boat building, and maritime arts to seek out the masters of the trades, which have utility back in the home sphere.

Recent trips by the crews of Croatian heritage vessels, falkuša and gajeta to the large festivals of Brest France 2008, and 2012, as well The Gulf of Morbihan 2015 provides evidence for the capacity crowds which draw of more than 700,000 visitors to these ‘existentially’ motivated celebrations of maritime life from around the planet. Similarly styled events could be fashioned along the maritime heritage trail route with festivals and events that have outreach mechanisms to enliven the authentic heritage that already exist along the coastal waters of the Adriatic drawing spectators and tourist with like minded intentions.

The idea of authenticity is foremost in this typology of tourism reaching the highest degree when the intangible knowledge is learned from an authentic master of the craft of any discipline. The focus in existential tourism shifts from one that is created with the tourist in mind such as tours that highlight local sights and museums, to an internal focus on authentic self-identity, which is attractive for those who are witness to it, or hope to gain experience. The authenticity of the intangible aspects of the culture is then shown in the public realm, thus glorifying the individual authenticity of the local intangible heritage. For example a maritime skills program where participants learn to tie knots from an experienced fisherman or learn woodworking from a master shipwright.

The active participation in the heritage event, as an experience, allows the visitor to take part as a participant observer. The preserved heritage becomes the attraction and the destination is created through the authentic event. The facilitator recreates the knowledge through the presentation, act, or being, the preservation of which is evident by the act itself.

This type of authenticity in tourism is described by MacCannell (1973) relating relevant stages of authenticity as the tourist views or participates in acts or events that increase exposure to normally off limits areas or spaces. The maritime heritage trail would create an 'initiated' tourist who has a special status and thus the ability to access areas that are normally out of view for the standard groups of outsiders.

In effect, tourism with a focus on the authentic acts can be created in and through the creation of the maritime trail. The experiential, and existential tourist can be enticed by the linking several ‘authentic destinations’ around the country. The intangible heritage of a region can be preserved in a global sphere by simply valuing the identity, customs, and culture of a local region in an increasingly homogenous multi-national realm. The uniqueness of place becomes the attraction, and the preservation becomes tied to the economics of the experience for the visitor along a route, engaged in authentic act in sites that are presently involved in the preservation of local intangible heritage.

Considerations in development

There are several important factors to consider in the development of a trail that will serve to unify an experience for visitors along the coast and islands of the Adriatic with a theme of maritime heritage. These factors include the facilitation and governance, scale and method of transportation of trail visitors, and integration into local sites, which include an already successful national and regional park system.

Governance by local stakeholders that can guide the direction and interpretation of the experiences for visitors and planning that is aligned within a national framework integrating to existing facilities, parks, interpretive, centers and hotels are two of the keystone features of trail development (Hayes and MacLeod, 2007; Silbergh et al., 1994). This alignment serves to unify, while the local governance can help to facilitate ownership of the idea within the local context and builds identity of the local culture of that locality. These symbols can be used later in the marketing materials and presentation of the site, and/or region as they are integrated into the international trail system.

Sheldon (2005) also points out that besides long term stake holder involvement in planning and evaluation, a sense of empowerment is critical for success. “Building of cultural pride through story-telling and memory of traditions, and a sense of identity are paramount.(pg. 6)”

The line between governance and planning is however difficult to quantify. Hayes and Macleod (2008) state that with the fragmented nature of trail governance, it is important to have an umbrella organization for what local stakeholders are incapable or unable to achieve on their own. Hayes and Macleold state a governing organization could provide “advocacy to policy makers, advise on best practice, develop umbrella branding, raise public consciousness, undertake benchmarking and develop practical evaluation methodologies” (Hayes and Macleod, 2008, pg.72). This is somewhat contradictory to best practices followed by integrated rural tourism as shown by Cawley and Gillmor (2008) that state, “IRT draws on concepts relating to alternative development in emphasizing a bottom-up approach that involves local stakeholders centrally” (Crawley and Gillmor, 2008, pg. 318). Finding a balance between governance and planning, local and extra-local, through participation from the onset is critical for success.

If local stakeholders are not involved in the initial policy and decision making, then the outcomes will reflect that lack of intrinsic ownership. One remedy for a national governance could be a rotating committee that has local stakeholders who hold office for certain term, while others are elected by the governing body to serve in roles and positions in a decentralized method of national and international governance with quarterly meetings to unify objectives and strategies of implementation in a timely manner.

Another method that has been described to be the balance between the local and extra-local management style is termed adaptive co-management. Berkes (2004) describes this methodology, which is used in community-based conservation (CBC), for the local management of ecological resources in parks and preserves. It is typified by a diligence of members to build and nurture trust though an adaptive methodology that allows stakeholders to evaluate and modify management structures, build on existing partnerships, and employ tactics that utilize the strengths of the entities which are involved in the relationships. This methodology is dynamic, as is the trail. It requires movement and evaluation by the teams involved.

In a Strategy for Theme Trails, Silbergh et al. (1994) outline objectives that a theme trail should achieve as well as seven development strategies the trail, once it is formed, should follow. This thorough outline includes several ideas already mentioned concerning development of rural touristic resources especially to do with the ideas of IRT. Silbergh states the design should “facilitate the discovery (education) and enjoyment (entertainment) of local heritage assets by both local and by visitors” (pg. 125). This objective also relates the emphasis stated in the earlier section by explicitly stating the ‘local’ in the touristic enterprise.

As Silbergh describes, the trail should be planned strategically and integrate local infrastructure, hotels, restaurant, parks, museums, visitor centers, and align with other local trails. For example the immensely popular walk on the walls of Dubrovnik can be integrated to a maritime heritage trail as the maritime theme is expressly relevant since the walls were built to protect from invaders from the land and sea. Marketing materials and economic strategy should be considered from the onset that includes a unifying theme and milestones to achieve in the forecast of economic objectives of traffic and participation.

As with any geographic project the ability to scale is critical. Hayes and Macleod (2008) in a review of management difficulties with large-scale heritage trails found there are several potential pitfalls in the management of the collaborative efforts. The difficulties include the lack of ownership on the local level (Leask and Barriere, 2000), difficulties in the coordination of a variety of stakeholders (Government of South Australia 2002), the management of conflict between different user groups (Murray and Graham, 1997), and the monitoring and evaluation of trails (Leask and Barriere, 2000, Government of South Australia 2002). Each level of scale has a its own unique set of challenges and is compounded by the challenges from above and below in the local, national, or regional arenas. Clear guidelines and objective are critical in the communication with partners and development of unifying strategies. Therefore scaling of the project is an important consideration in the planning phase.

For the Adriatic Maritime Heritage Trail, scale should be set to national levels, then combined with the heritage trails of the countries that share the body of water, making this and international collaboration. National focus would be on uniting site partners and creating a governing body and according administrational development. Locally, spur trails could be proposed and integrated, and local partners would work together to merge into the unifying theme as the traveler goes from one area to the next.

Any mode of transportation should allow visitors to the country to come to all parts of the trail. By car or boat, by foot or bicycle, the traveler to Europe, the Adriatic or the Mediterranean would recognize the trail as a destination. For example, a traveler who has visited the Mare Nostrum Trail which links sites along the Phoenician ring in Syria, Lebanon, Italy and Malta5 could spend additional time in the Adriatic. This would help to facilitate international marketing of heritage tourism by highlighting linked trails in different countries thereby helping the local preservation efforts abroad and locally simultaneously.

In design, the Adriatic Maritime Heritage Trail would be well suited to the already boat-oriented charter guest, which could conceivably be interested in visiting the maritime heritage sites along the coast and islands. Strategic Goals for the Nautical Tourism Development Strategy 2009–2019, states, “attractiveness of contents ashore, cultural offer as an important factor of tourist and nautical offerings” (Republic of Croatia, 2008, pg. 8). It would be of interest to present a further study of the tourists that sail along the coast reviewing their interest and outcomes through their visit. The Croatian Bureau of Statistics stated as cited in Perko et al. (2011) that in 2010 there was 327,631 charter guests and 58,394 arrivals of foreign yachts and boats were registered.6 A short survey of level of interest in local maritime culture would not only gage the level of interest, but also could help shape the route and attractions for visitors.

There are several collections along the coast which represent a large body of cultural resources preserved by maritime museums. They are located in many cities including Split, Dubrovnik, Rijeka. There are also several smaller museums that focus on island specifics, such as the Fisheries Museum on the island of Vis in Komiža, Batana House in Rovinj and a new museum in Betina, dedicated to the gajeta on the island of Murter. Aside from resources that are curated in some form or another, there are the local cultural resources in a network of organizations, trades, and occupations, which vary tremendously, but still fall under the term of maritime heritage. Shipyards, heritage vessels, boatbuilding shops and other represented trades are important, while dance and singing groups, as well as poetry and visual art, all support and have been born from the maritime trades, as art and the trades in island and coastal life are closely linked. The description of the sea in words from the sailors and fisherman, the lament of the song, and the dance of the return are all closely tied to the culture and identity of place and the sea that surrounds them. Combining these aspects in a multifaceted experience for nautical visitors would undoubtedly create a unique voyage for the maritime tourist.

Conclusion

The Adriatic coast and island represents a large body of cultural knowledge and artifacts that are classified as maritime heritage. Merging these artifacts into a string of gems that a tourist could visit along the coast or islands represents a methodology that would allow these unique features of land, landscape, and knowledge to be presented in their environment in which they reside. This methodology allows for the preserving of the heritage from the populations that have built and maintained them in a form of community-based heritage management.

Risks associated with the creation of cultural programs for tourism have been noted by several scholars, including Halewood and Hannam (2001) who point to difficulties and compromise in the presentation of cultural tourism especially to do with the idea of authenticity. Jerome (2008) states that discrepancies in definition of the term authenticity go back to the first official using in the UNESCO World Heritage in Convention of 1977 which outlines guidelines of historic sites. The attributes of the UNESCO’s “authenticity” include aspects of intangible heritage which are much more difficult to define and include; use, function, traditions, language, spirit, and feeling. Community based cultural preservation programs that are managed by the local inhabitants would be one way to help ensure that knowledge base is passed on with the local definition of “authentic” in its various forms. For example, the creation a web based platform that allows boat owners to be in direct contact with tourists could be a possible solution to bridge the gap between tourist and boat owners eliminating the marketing and manipulation of local symbols by outsiders.

Combining the unity of site and existing infrastructure allows for local stakeholders to be inclusive of the process, represented in the governance, and helps to create economic incentive for the younger generations who will be caretakers of the knowledge, art, artifacts and territory in which they reside. Creating a cultural landscape that is inclusive of all aspects of the cultural sphere also includes the land and ecological heritage of the given region.

The proposal for the Adriatic Maritime Heritage Trail would include types of sites such as lighthouses, ships and shipwrecks, museums, and other tangible artifacts around the country, while supporting intangible heritage through locally facilitated cultural preservation programs. In some maritime heritage trails, the sole purpose is to showcase artifact sites, with secondary activities such as restaurants and harbor tours and hotel, the social aspects, to be provided as a parallel, but removed from the trail itself. This is similar to what Hayes and Macleod (2008) conceive of as the product based conceptualization. In this iteration of the maritime heritage trail, a priority of intangible heritage is made with the community-based trail design forefront in the conceptualization. Utilizing this method would put people in the center, and artifacts and museums come to the aid of the story being told, emphasizing the experiential model of touristic development as shown by Pine and Gilmore (1998).

In reviewing nautical tourism, it is clear that the ecological aspects in the Adriatic are the primary attraction for the visitor. Again the Croatian Ministry of the Sea states,“nautical tourists find most attractive the areas under different categories of protection” (Republic of Croatia, 2008, pg. 7). These include various types of parks and preserves as well as local conservation areas and nature monuments. This statement represents an already decided shift in preservation of ecological diversity and has for the last 30 years created a vast number of parks and reserves that entice tourist to visit.

The combination of cultural and ecological heritage creates a more holistic story of the land and people in the environment together. Croatia is unique as many of the nature parks have inhabitants and communities that reside within park boundaries. For example, Kornati, which receives the highest number of nautical visitors per year (ibid, pg. 7), is also home to one of the richest maritime heritage locations along the coast. With several hundred heritage vessels registered, monthly festivals, and local agriculture supported through the use of heritage craft, the Kornati is not only rich in ecological heritage, it is also brimming with the cultural intangible heritage that has been the focus of this paper. Creating avenues to highlight the cultural ecology of specific parks could be another method of this multi-faceted methodology, which would allow all stakeholders to benefit from the creation of a large-scale trail network.

Again borrowing from community-based conservation and adaptive co-management, a multi-faceted park plan could include cultural eco-tours where locals are invited to take part in the interpretation of the parks ecological resources, as well as decision-making processes. For example in Kornati, park staff could allow local guides to do harbor tours in historic craft and discuss the local ecological knowledge and stories of the place, thus merging ecological and maritime heritage and valuing local infrastructure and heritage which in turn elevates status of the individuals involved.

The trail as a combination of these elements, provides the structure and properties that integrate multiple aspects, and when combined together create a truly unique maritime heritage experience. One that the emphasis is not solely on the tourist, tangible artifacts, and ecological treasures, but includes community members and the preservation of intangible and ecological heritage of the region for future generations.

Endnotes

References

- Bachich, 1970 W. Bachich History of the Eastern Adriatic. Croatia: Land, People, Culture, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Ont. (1970)

- Bender, 2014 J. Bender Intangible heritage in the maritime realm: the pedagogy of functional preservation. Nar. Umjet., 1 (51) (2014), pp. 7-28

- Berkes, 2004 F. Berkes Rethinking community-based conservation. Conserv. Biol., 18 (3) (2004), pp. 621-630

- Brandywine Conservancy Environmental Management Agency, 1997 Brandywine Conservancy Environmental Management Agency Community Trails Handbook. Brandywine Conservancy (1997)

- Briedenhann and Wickens, 2004 J. Briedenhann, E. Wickens Tourism routes as a tool for the economic development of rural areas—vibrant hope or impossible dream?. Tourism management, 25 (1) (2004), pp. 71-79

- Cawley and Gillmor, 2008 M. Cawley, D.A. Gillmor Integrated rural tourism: concepts and practice. Ann. Tourism Res., 35 (2) (2008), pp. 316-337

- Cohen, 1979 E. Cohen A phenomenology of tourist experiences. Sociology, 13 (2) (1979), pp. 179-201

- Fîntîneru et al., 2014 A. Fîntîneru, G. Fîntîneru, D.I. Smedescu Analysis of top destinations in tourism, according to volume of receipts during 2001–2011. Analysis, 14 (2) (2014)

- Gonzalez, 2008 M.V. Gonzalez Intangible heritage tourism and identity. Tourism Manage., 29 (4) (2008), pp. 807-810

- Halewood and Hannam, 2001 C. Halewood, K. Hannam Viking heritage tourism: authenticity and commodification. Ann. Tourism Res., 28 (3) (2001), pp. 565-580

- Hayes and MacLeod, 2007 D. Hayes, N. MacLeod Packaging places: designing heritage trails using an experience economy perspective to maximize visitor engagement. J. Vacation Mark., 13 (1) (2007), pp. 45-58

- Hayes and Macleod, 2008 D. Hayes, N. Macleod Putting down routes: an examination of local government cultural policy shaping the development of heritage trails. Manag. Leisure, 13 (2) (2008), pp. 57-73

- Jerome, 2008 P. Jerome An introduction to authenticity in preservation. APT Bulletin, 39 (2/3) (2008), pp. 3-7

- Leask and Barriere, 2000 A. Leask, O. Barriere The development of heritage trails in Scotland. Insights (2000), pp. A117-A123

- MacCannell, 1973 D. MacCannell Staged authenticity: arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. (1973), pp. 589-603

- Morgan et al., 2009 M. Morgan, J. Elbe, J. de Esteban Curiel Has the experience economy arrived? The views of destination managers in three visitor-dependent areas. Int. J. Tourism Res., 11 (2) (2009), pp. 201-216

- Murray and Graham, 1997 M. Murray, B. Graham Exploring the dialectics of route-based tourism: the Camino de Santiago. Tourism Manage., 18.8 (1997), pp. 513-524

- Oh et al., 2007 H. Oh, A.M. Fiore, M. Jeoung Measuring experience economy concepts: tourism applications. J. Travel Res., 46 (2) (2007), pp. 119-132

- Perko et al., 2011 Perko, N., Stupalo, V., Jolić, N., 2011. Impact of nautical vessels on Croatian sea ports capacity. In: 14th International Conference on Transport Science-ICTS 2011.

- Pine and Gilmore, 1998 B.J. Pine, J.H. Gilmore Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev., 76 (1998), pp. 97-105

- Republic of Croatia, 2008 Republic of Croatia Nautical tourism development strategy of the Republic of Croatia 2009–2019. Ministry of the Sea, Transport and Infrastructure, Ministry of Tourism, Zagreb, Croatia (2008)

- Sheldon, 2005 Sheldon, P.J., 2005. The Challenges to Sustainability in Island Tourism. School of Travel Industry Management, University of Hawaii, Occasional Paper 2005–01.

- Sebold and Leach, 1991 K.R. Sebold, S.A. Leach Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail: Southern New Jersey and the Delaware Bay: Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem Counties. US Department of the Interior, National Park Service (1991)

- Silbergh et al., 1994 D. Silbergh, J.M. Fladmark, G. Henry, M. Young A strategy for theme trails. Cultural Tourism: Papers Presented at the Robert Gordon University Heritage Convention 1994, Donhead Publishing Ltd (1994), pp. 123-146

- Stronza, 2001 A. Stronza Anthropology of tourism: forging new ground for ecotourism and other alternatives. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. (2001), pp. 261-283