Undoing ‘marginality’: The islands of the Mahakam Delta, East Kalimantan (Indonesia)

Institute Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology, Leiden University, The Netherlands

Law Faculty, Gajah Mada University, Jogyakarta, Indonesia

Abstract

The islands in the delta of the Mahakam River in East Kalimantan have for a very long time been of little interest to anybody. It was a hostile environment for human settlement, exploitable resources were limited and nobody could think of options for alternative forms of land use. The area was classified as ‘marginal or empty land’.

Things started to change dramatically in the 1990’s when the development of shrimp ponds became an attractive option. Land covered with forests of nipa palms and mangrove trees could be converted into highly profitable shrimp ponds. The demand for shrimps was booming and the delta was a kind of new frontier without any government control. Buginese fishermen and investors started to convert the landscape into extensive shrimp ponds. The financial crisis in Southeast Asia at the end of the 1990’s made the export of shrimps in dollars from Indonesia even more profitable because of the enormous inflation of the country’s currency. Over the years new settlements were constructed and informal forms of land rights were established. The spirit of ‘regional autonomy’ after the fall of President Suharto in 1998 contributed to this development.

The discovery in the delta of new fields full of oil and natural gas brought new and powerful actors into the area. As a result of competing claims over land and resources, the formerly ‘marginal and empty lands’ became highly contested. At present the provincial government is trying to take control over the delta islands but the gap between formal and informal forms of management is not easy to overcome.

The article is based on recent field research in the area as part of the East Kalimantan Project within the framework of research collaboration between Indonesia and the Netherlands.

Keywords

Delta Islands, Kalimantan, Mahakam River, Shrimp ponds, Marginal lands

Introduction

In November 2010, just before the start of an international conference about the Mahakam River and watershed the provincial government of East Kalimantan published a press release stating that it had for a long time not given sufficient attention to the islands of the Mahakam Delta. Though it was still officially classified as state forest land, the heavy resource conflicts between local and external fishermen, between shrimp pond owners and an oil company and numerous other stakeholders required serious attention. In addition it was also recognized that a ‘new reality’ had been created in the area beyond just being ‘state forest land’. Numerous migrants had settled in the area, opening the mangrove and nipa forests in order to establish shrimp ponds and ‘Jakarta’ had issued a mining concession to a French company. Local level bureaucrats had made use of the wave decentralization after the fall of President Suharto in May 1998 to issue a variety of documents stating ownership of the land and local recourses irrespective of the lack of agreement from higher level officials, let alone from the central government. Many of them were not even aware of the events happening in the area. The effects of years of neglect of administrative attention came out in the open as a result of numerous conflicts some of which were taken to court. But a large international and interdisciplinary research project certainly played a crucial role in raising awareness about this resource frontier. It was time for chance according to high provincial officials. In the course of the following year the governor of the province installed a special body to manage the Mahakam Delta and launched his ‘Save the Mahakam Delta’ programme. Total E&P Indonesie, the mining company operating in the area was quick to announce its contribution as part of its Corporate Social Responsibility.

What exactly had happened in the Mahakam Delta that provoked this reaction? Why had a neglected area of swampy islands at the mouth of a river, creating a hostile environment for human settlement, been turned into a highly contested area?

In this paper we will discuss the changing perspectives on the islands in the Mahakam Delta, and how their status as marginal islands as the edge of Indonesia’s social and economic life has changed into an area with serious resource conflicts.1

Land classification: delta islands as ‘sleeping land’

Indonesia is a large island state in Southeast Asia comprising more than 17,000 islands. All types of islands are to be found in the archipelago which could be differentiated on the basis of size, geology, flora and fauna, and island cultures. Within the enormous body of biological and socio-cultural knowledge on the country’s islands relatively little attention is paid to delta islands. Most of the islands in the country are formed by processes of volcanic activity or geological movements of plates and shields. Others are formed by elevated coral reefs. In fact not many rivers in Indonesia actually have extended delta’s with the exception of some large rivers on the south coast of Papua, the east coast of Sumatra, and some rivers on Kalimantan, as the Indonesian part of Borneo is generally called. In the case of delta’s there is usually a gradual transition from lowland and peat swamp forests towards these delta islands which are formed as a result of deposits of mud taken by the flow of the river from upstream areas and the tidal movements. The islands are usually overgrown by mangroves and nipa palms, and they have a typical kind of flora and fauna. The islands grow towards the sea while the channels or rivers in between them may vary greatly in depth as a result of the hydraulic dynamics between the discharge of the river and the tidal movement (MacKinnon, 1996; Tomascik, 1997). Because of the fact that there are very low and that they regularly overflow the islands are usually sparsely populated. In spite of their ecological dynamics they are usually referred to as ‘empty land’ or lahan tidur, ‘sleeping land’.

In land use classification systems there is usually a category referring to areas which are apparently of little use. Their names are indicative for their limited value in terms of prevailing perceptions of land use. These lands are referred to by terms as ‘marginal’, ‘empty’, ‘underutilized’, or ‘unproductive’. In some cases countries have developed specific terms to indicate these types of land. In the Philippines an often used term is ‘idle’ as in the case of ‘idle grasslands’. Indonesia has both used the term ‘empty’ land, tahan kosong as well as ‘sleeping’ land, lahan tidur.2 These terms refer to a dominant perception of seeing productive, cultivated land as the ‘real’ destination of land. So a wilderness area was considered as land ‘waiting’ to be cultivated. Many types of lands are classified as marginal lands. These include swamps, mangrove forests, degraded grasslands, or areas with extended dry periods and without any opportunities to exploit its resources. Delta islands in Indonesia were usually also classified as being marginal until relatively recent.

There are various reasons why land may be considered as marginal. It may refer to particular bio-physical characteristics, including low soil fertility, poor drainage, soil salinity or soil shallowness. It may however also refer to completely different characteristics. Land may be marginal because of its geographical location at great distances of markets or centres of economic and agricultural activities. In some cases low historical population density or restrictive tenure arrangements may be the reason why the land was never converted into productive land uses (Wiegeman et al., 2008; Snelder, 2012).

Undoing marginality

For a variety of reasons this marginality can be undone. Interest in new land for cultivation of crops is at present a major cause of conversion of marginal lands into other land use types. This is caused by the high demand for food crops, grazing lands for cattle as well as for the production of biofuel crops, such as oil palms, and jatropha. This demand is a driving force in converting marginal lands of various types into productive lands.

New infrastructure (roads, railways, hydropower dams, harbour facilities) can lead to the integration of isolated areas into mainstream socio-economic activities because of increased accessibility. The same holds for new technology as a result of which new frontiers of resources extraction can be created such as in the case of new mining techniques. Often political decisions redefine the marginal status of certain areas. In some cases border lands, which were for a long time at the edge of nation’s political interests, can be turned into areas of crucial strategic importance for political, military or other reasons.

Changing perspectives or new market opportunities may lead to a redefinition of marginal areas. An interesting case is the ‘value’ of the so-called peat swamp forests in Indonesia. While peat swamp forest were for a long time considered as a hostile environment unsuited for agriculture and other activities apart from biodiversity conservation, the enormous amount of carbon stored into the thick peat layers has now obtained market value in terms of tradable carbon credits through CDM-REDD mechanisms. What used to be an almost useless type of ecosystem, has suddenly obtained market value. And interestingly, the market value only exists as long as the peat swamp forest are not exploited because any form of exploitation (drainage, logging, conversion) will automatically lead to reduction of the amount of carbon stored in the soil. By these mechanisms many marginal areas have lost their status as marginal lands: this change has been caused not so much by changes in the area itself as well as by changing perspectives and new market or technological opportunities.

In the course of this process of undoing marginality conflicts may arise between local populations and external agents with different perceptions of the environment or because of projected alternative forms of land use. Local populations do not consider themselves as marginal, nor do they consider their land as such. On the contrary it is the basis of their existence and livelihood, which they have managed according to their own values and perceptions (Dove, 2008).

Within Indonesia many types of land have been classified as marginal, ‘empty’ or (still) ‘sleeping’. These include the peat swamp forests, zones of mangrove and nipa vegetation, grasslands covered by alang-alang (Imperata cylindrica). Delta islands along the east coast of Sumatra, the west and east coast of Kalimantan as well as along the southern coast of Papua certainly belong to this category of marginal lands. For a long time these islands were of little use because of their being unsuitable for agriculture, and their uninviting habitat. In the colonial history these areas were often classified as ‘pirats’ nets’ because of their inaccessibility, (Map 1).

The Mahakam Delta

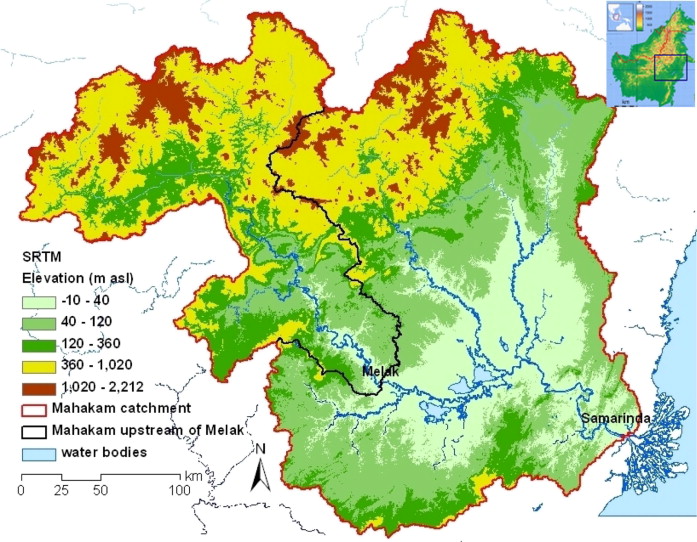

The Mahakam Delta is located at the mouth of the Mahakam River in East Kalimantan. The Mahakam River is one of the largest rivers in Indonesia. It has a length of 980 km and an estimated catchment area of more than 77,800 km2. Before flowing into the Makassar Strait the river has to pass through a relatively narrow strip of land in between two chains of hills separating the Mahakam watershed from the coastal zone (see Map 2). In the middle of the watershed of the Mahakam River there are a number of lakes which play a crucial role in the storage of water during the rainy season while they also catch a lot of sediment caused by erosion as a result of logging and mining operations (MacKinnon, 1996).

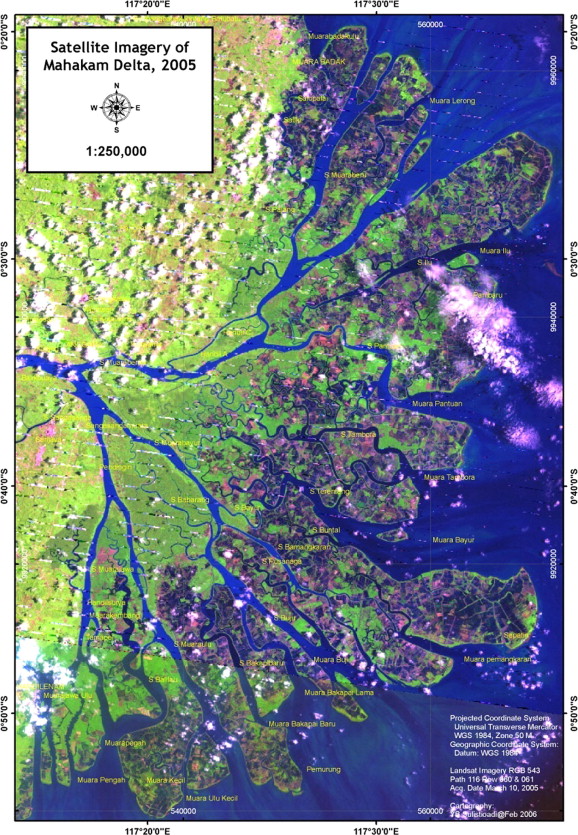

The delta of the Mahakam comprises some 42 islands with a total land surface of about 1100 km2. The islands have been formed in the course of history by the interplay between the sediment carried from the head waters of the Mahakam River to the sea and the tidal movements within the Makassar Strait. Because of their origin the islands are all very flat and muddy. They are mainly covered by nipa palms (Nypa fruticans) and various types of mangroves (Rhizophora spp.). Other species of vegetation are pedada (Sonneratia alba) and nibung (Oncosoerma sp.). Close to the mouth of the river there is also a zone with fresh water forest. Some of the larger islands may also have some other kinds of vegetation. The collection of islands is shaped like a fan. Geomorphologically the delta is divided in three zones, with varying degrees of salinity. These are: the delta plain consisting of small islands separated by tributary channels with mixed fresh and salt water, the delta front which is the fringe immerged during high tide and which is the major area for sediment deposit, and finally the pro-delta, the deeper area bordering the Makassar Strait (Sidik, 2012; Bengen, 2011a,b). The islands expand mainly in eastern direction. The hydrological dynamics between the discharge of the river and the tidal movements have shaped the islands and the channels in between them. Some of the channels are very deep and allow relatively large vessels to enter the delta and sail towards the province capital, Samarinda, located somewhat upstream at the banks of the river. The delta islands are a favourite place for various fish species to feed and spawn. A number of mammals, reptiles and fish eating birds do very well in this type of eco-system. Among them are the probiscus monkey, the large lizard (biawak), and the Brahmini kite and crested goshawk. There are also salt water crocodiles in the delta. In the past and on the elevated parts of land some agriculture was practiced, in particular coconuts, but after the booming of the shrimp ponds, agriculture was abandoned (Chaineau et al., 2010). There are no roads in the delta. All transport has to take place across the water.

The muddy and swampy forest environment on the islands has never been inviting for human settlement. The islands’ forests were of no commercial use compared to the highly valuable diptereocarp species in the interior of the province with all the commercial timber species. That is one of the reasons why the Department of Forestry never paid serious attention to these islands even though the area was classified as state forest land according to the national land use planning agency.

Human settlement

For a very long time the islands were uninhabited. Some Bajau people, usually called sea nomads, were active in the area as fishermen, trading the surplus of fish and other marine products with inland communities. These fishermen basically lived on their boats. Migration to the east coast of Kalimantan was stimulated by political unrest in the island of Sulawesi in the second half of the 19th century. There is some historical reference that during the Dutch colonial times a small settlement called Pemangkaran was established by Bajau and Buginese fishermen where they also planted some coconuts. Just before the Japanese occupation (1942–45) two more fishing villages were founded, Pantuan and Sungaipatin. Dried fish and shrimps, caught from the wild, were bartered with traders from Samarinda for rice, sugar and other products. By the end of the war all main villages had been blazed to ashes and the inhabitants fled to the forest or to the capital town of Samarinda. So in the first years of Indonesian independence the population in the delta was very small and no traders were active anymore. Fishermen had to sell their dried fish directly to the urban markets. Smuggling various products both under colonial rule (Dutch and Japanese) as well as under Indonesian rule has also been part of the livelihood in the delta (Benson et al., 2002, 36). In the early 1950’s there was again political unrest in South Sulawesi. The Indonesian army tried to fight the Darul Islam rebellion under Kahar Muzakar which opposed the central authority of the newly established national government. In 1957 the announcement of the so-called ‘Charter of the Common Struggle’ (Piagam Perjuangan Semesta, or Permesta) in South Sulawesi led to the declaration of a state of war and siege by Jakarta and did put the army in a powerful position (Legge, 1972). Numerous troupes were sent to Sulawesi and many supporters of the rebellion as well as civilian people fled to East Kalimantan where they could live safely and find a better life in the new place. Some joined the Bajau settlements.

The early 1970s is considered as a turning point with the start of the oil exploration. At an earlier stage such exploration had already taken place but it did not yield promising results. Things were about to change. Apart from small scale fishing, there suddenly was a demand for paid labour, as surveyors, security guards, and boat drivers. The second important event was the opening of the first cold storage facility in East Kalimantan in 1974. This increased the opportunity to market successful catches and it even allowed for export to the international market. The success of this first facility invited other Buginese investors to come to the area from South Sulawesi who soon became a kind of middlemen (punggawa) between local fishermen and external traders. Boats became bigger, engines more powerful and the equipment was modernized. In particular trawl fishing became popular until it was completely banned in 1980. As the demand for shrimps in the international market was very big people started to experiment with shrimp ponds. Some Buginese with experience in raising milk fish in ponds in South Sulawesi took up the challenge and started opening up shrimp ponds in the nipa and mangrove forests. This was the start of the process that completely transformed the delta islands. Hundreds of migrants started to come from Sulawesi as labourers in these fish ponds. Villages grew and new settlements were established. The delta had become a true resource frontier with open access as there was hardly any governmental presence.

New economic opportunities attracted new migrants. The massive logging operations in the lowlands of East Kalimantan attracted a new workforce: these were the booming years of the logging industry, legal and illegal. Some of the labourers resigned after a few years of working for the logging companies and tried their luck elsewhere in the province including the delta area. Two oil and gas companies Total E&P Indonesie and Virginia Indonesia Company (VICO) expanded their operations and needed surveyors, boats men and other support staff.

The most crucial activity that has changed the appearance of the delta islands however has been the cultivation of the shrimp ponds. This activity was started in the 1980s by a number of local people who were sponsored by some companies operating from Samarinda which availed of cold storage facilities. A reason for the companies to sponsor the making of shrimp ponds was the decrease of shrimp catches from the sea caused by the ban on the use of trawls. The ponds were constructed in the nipa and mangrove forests. All the trees were cut and the land was cleared. Initially it was done by hand but later powerful excavators were brought in. Small dykes along the edges were constructed. The process required an enormous amount of labour but it turned out to be a profitable business.

The form of aquaculture became absolutely booming with the start of the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and 1998. When the Indonesian rupiah strongly devaluated, the export of shrimps calculated in US dollars became even more profitable. When this rumour spread, numerous Buginese investors entered the area and started to open up more and more ponds. With prices increasing more than tenfold within a period of two years, the scale of land clearing for shrimp ponds increased accordingly. With the enormous profits the Buginese punggawa, also started to built their cold storage facilities within the villages in the delta, thereby passing by the initial traders and investors from Samarinda. Some of the investors became truly big men.

By now more than 70% of the land surface of the delta islands has been converted into shrimp ponds. During the last three decades, the population of the Mahakam Delta has grown to more than 50,000 people (DKP Pro. KALTIM 2008), though it should be mentioned that the subdistricts not only cover the delta islands. They partly cover parts of the mainland as well (Table 1).

| No. | Subdistrict | Population growth | Villages in Mahakam Delta | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2008 | |||

| 1. | Samboja | 22.294 | 30.944 | 35.944 | 51.336 | Muara Sembilang |

| 2. | Muara Jawa | 11.429 | 16.692 | 19.995 | 28.359 | Muara Kembang, Taman Pole, Dondang, Muara Jawa Ilir, Muara Jawa Tengah, Muara Jawa Ulu. |

| 3. | Sanga-Sanga | 9.893 | 10.318 | 11.294 | 15.016 | Sanga-sanga Muara, Pendingin |

| 4. | Anggana | 10.521 | 12.884 | 18.372 | 28.756 | Tani Baru, Kutai Lama, Muara Pantuan, Anggana, Sepatin, Sungai Meriam, Handil Terusan |

| 5. | Muara Badak | 12.583 | 20.793 | 26.450 | 37.583 | Seliki, Muara Badak Ulu, Muara Badak Ilir, Salopalai |

| Total | ||||||

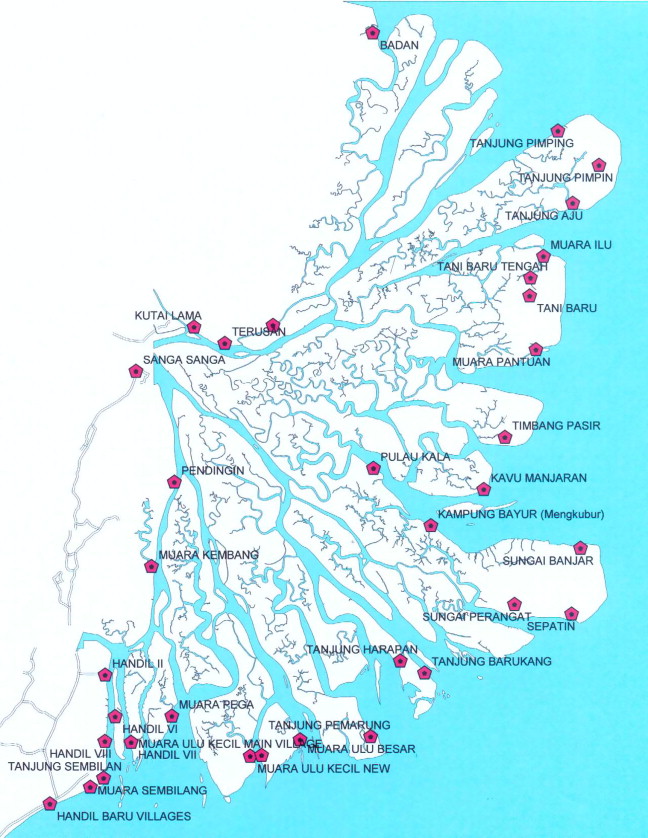

The population lives in villages scattered over the islands. All villages have elevated pathways made of wood. The wooden houses are built on stilts made of mangrove stems. There is very little agriculture around the villages, usually only some coconut palms. Most of the villages are built on the eastern side of the delta with easy access to the open sea. They are built quite densely with little space in between the houses. In the course of time community facilities have been built: there are jetties and bridges across the channels, there are also little shops, schools, and small health clinics.

The delta islands are part of the district (kabupaten) of Kutai Kartanegara, one of the nine districts of the Province of East Kalimantan. Its history goes back a long time. A kingdom was founded in the upper part of the Mahakam River way back in history by warriors from a Javanese kingdom that was founded in the 14th century by King Kartanegara. The centre of power was moved a couple of times before it was moved to present-day Tenggarong, the capital of the district of Kutai Kartanegara. In 1844 Kingdom Kutai Kartenagara was occupied by the Dutch colonial army and the king was forced into an agreement to surrender to the Dutch but without abolishing the kingdom. It was a form of indirect rule, through which the Dutch could take important decisions and have them implemented by local rulers. The first oil was found in 1902 and the kingdom soon after handed out its first mining concession to the Koetai Exploratie Maatschappij (Lindblad, 1989; Magenda, 1991). In the years that followed numerous other oil fields were found in the district before moving into the delta for exploration (Duval, 2012). After Indonesia proclaimed independence in 1945 the kingdom did not ceased to exist. In fact the kingdom still ruled over a large part of the province of East Kalimantan. There was a kind of dual government for some time. The central government in Jakarta however took all authority with respect to oil exploitation and all mining activities, away from the kingdom, as it did all over the country.

In recent years the district of Kutai Kartanegara has become one of the wealthiest in the country because of the income generated from its natural resources. It is very rich in terms of exploitable timber and in terms of oil, natural gas and coal.3 The district itself is divided again in a number of sub-districts (kecamatan) which comprise a number of administrative villages (desa), which may include a number of settlements. The main villages in the delta are Muara Pantuan, Sepatin and Tani Baru (kec. Anggana), Saliki, Handil and Salo Palai (kec. Muara Badak). They are located on the eastern side of the islands close to the Strait of Makassar (see Map 3).

Resource use

The Mahakam Delta has for a long time mainly been exploited for its fishery resources. It is only in more recent years that new forms of exploitation became possible thereby transforming the islands from a natural ecosystem into a completely domesticated landscape. Here we will shortly discuss the major forms of resource use, that is small scale fishing, aquaculture and oil and gas extraction. Finally a few words must also be said about shipping as this also has an impact on the way the delta is used.

- Small scale fishing: The nipa and mangrove forests on the islands with their alluvial soils and the dynamic interaction with the tidal movements have created rich fishing grounds for a large variety of species. The early settlers, in particular the Bajau people, had come to this area to fish for local shrimps, crabs and numerous fish species. They used nets as well as tidal traps and other techniques to catch the fish, which were for their own consumption as well as for selling. They used small wooden boats which were all privately owned.

- Aquaculture: The development of aquaculture was not initiated by local fishermen but by outside investors who also invited migrants from Sulawesi to do the hard work of cutting the trees, making the dikes. The initial settlers never participated in this kind of work as they disliked the work. When the aquaculture turned out to be such a booming business at the end of the 1990s, more migrants came into the area, opening up more shrimp ponds. The harvests from the ponds was for the greater part meant for export to Japan, Taiwan and to Europe. Only a very small portion of the shrimp was consumed domestically. Since 2002 the sector also started to face some problems in terms diseases of the shrimps and reduced harvests.

- Fishing at a larger scale: With the availability of larger ships, with powerful engines and ever larger nets, fishermen from other areas in Kalimantan and Sulawesi started to arrive in the waters of the Mahakam Delta. Though these larger vessels cannot operate close to the islands they do search for fish in the nearby coastal areas and the wider channels in between the islands, thereby limiting the options for the smaller fishermen.

- Oil and gas exploitation: In 1967 the Indonesian Ministry of Mining in Jakarta awarded the Japan Petroleum Exploration a large offshore area of the Mahakam Delta but it failed to discover any oil. In 1970 it passed on the work area to the French company Total E&P Indonesie. Total discovered new fields of oil and gas and over the years drill platforms, pipe lines and all kinds of installations have been built in the Mahakam Delta either on land, in the channels or at sea. The Mahakam Delta has been turned into one of the most profitable mining areas within Indonesia. Total contributes substantial revenues to the national budget of the country through its operations in the Mahakam Delta. Regularly new oil and gas fields are being discovered.

- Transport: The Mahakam Delta is at the mouth of Mahakam River. Its enormous hinterland contains large quantities of timber and in recent years the exploitation of coal for China and India has greatly stimulated the increase of transport in the delta. Daily large cargo vessels are loaded on the banks of the Mahakam River near Samarinda before setting off to distant markets. These ships or large barges and pontoons have to pass through the channels in the Mahakam Delta before they reach the open sea. Because of their size, and their numbers they have a strong impact on the other activities within the delta.

Stakeholders and resource conflicts

Various types of resource use within a single area can fit together well as long the users do not compete for the same resources or as long as one form of exploitation does not have a negative impact on other uses. However if such fortunate conditions are not met, conflicts are likely to occur. Conflicts might emerge about the rights of exploitation and about modes or intensities of operation in particular if there is not a single authority or governmental structure by which (potential) conflicts are managed or even prevented by means of a clear set of rules and regulations. The Mahakam Delta does not have a single governmental structure managing the area. Even though initially the area was primarily classified as state forest land, a lot has happened without the Ministry of Forestry granting permission for such activities (Bourgois et al., 2002).

It basically started with the establishment of the shrimp pond by Buginese migrants. They never even tried to seek permission from the Forestry Department in the district or provincial capital. In the eyes of the people, this land did not belong to anybody, it was ‘empty land’, tanah kosong. And with the complete absence of any representative of the Ministry of Forestry, no voice was heard contradicting this perspective. Once a person had lived for a couple of months in a village in the delta, he could simply go to the village head and ask for a letter stating that he had legally opened up the land to establish a shrimp pond. At the same time the letter proved that he or she is the one who owns the land. With sufficient ‘empty land’ still available the village head issued such a statement giving permission to cultivate the land, ‘izin garap lahan’. This letter is called a surat pernyataan penguasaan tanah (SPPT). Some pond owners who would like to have a stronger security over their land had asked also a signature from the head of the sub-district. Even though all parties involved were aware that this letter was not really an official legal document, it created locally some kind of legal status for the activities undertaken. Such letters could also serve as proof of property in case of selling the land or as collateral. In the course of time a large part of the land in the delta islands got covered by this kind of letters.

Key actors in the Mahakam delta are the Buginese middlemen, punggawa. They were the first people to come to the area with the purpose of opening large shrimp ponds. They were also the one who could invest in such activities. They guided fellow Buginese to areas suitable for shrimp ponds and they applied for titles to that land (Safitri, 2011). They were the initial investors in the area and they have been successful in establishing a wide network with external traders and officials. Within the Buginese community they maintain their position on the basis of patron-client relations that have been characteristic for Buginese communities both in their home land in South Sulawesi as well as in areas to which they migrated. Similar patterns are also found in East Sumatra and along the coast of East Kalimantan. Recent research however also indicates that the traditional patron–client relation which used to be a kind of all-encompassing relation, is gradually turning into a more capitalistic one with less social strings attached (Pelras, 1996, 2000; Vayda, 1996; Timmer, 2010; Lenggono, 2011). In the Mahakam Delta the punggawa did not only become the initial investors, they were the ones to establish cold store facilities in which the shrimps could be stored. They provided capital for the boats, house construction, and they were usually also the ones to open the first stores. Through their external contacts they established good relationships with officials from the (sub)districts and often they were successful in their campaigns for the election of village head. This changing type of relationship is also evident since local shrimp pond owners are faced with diseases, diminishing harvests and reduced prices for the shrimps. Under those circumstances many ‘clients’ have to experience that their ‘patron’ does not act anymore according to their expectations. They are forced to cope with the difficulties themselves.

The situation with respect to the mining operations is radically different. In this case it was the Jakarta-based Ministry of Mining that issued concessions for operations. In doing so it by-passed local authorities. It also by passed the Ministry of Forestry which, just as in the case of the shrimp pond owners, should have been asked for permission before the start of the operations as part of the drilling takes place on state forest land and also pipes and installations are partly constructed on the land. Back up by the central government and being of great importance for national revenues the officially missing permission of the Ministry of Forestry has never greatly hampered the operations (Simarmata, 2012).

As mining operations greatly expanded and with numerous drilling stations, pipes lines and processing installations across the islands and channels, conflicts between the mining company and the shrimp pond owners and fishermen were hard to avoid. And it is exactly here that various legal realities started to clash. In case of conflicts with local shrimp pond owners the mining company argues on the basis of a nationally issued concession against letters issued by a local village head which are not even recognized by the district forestry officials.

However because of vulnerability inherent to its mode of operations (sabotage of installations and pipelines), the mining company has developed a practice of paying compensation in case pipe lines had to pass across the land of shrimp pond owners. The company also pays compensation in case of damage to fishing gear or damage to the dykes of the shrimp ponds. The fishermen complain about pollution of the waters because of oil spills, and the large number of movements of boats. However with the ever expanding shrimp ponds on the one hand and the equally expanding mining operations on the other hand, the claims for compensation rapidly increases. There have also been cases of claims that the company did not want to pay and that were taken to the district level for final decision. And then things started to become really complicated because of the diverging legal realities and power differences between the stakeholders.

The company also complains that the shrimp ponds are not properly constructed. In many cases there hardly exists a so-called green belt between the channels and the dyke of the pond, which implies that waves from the movement of ships immediately hit the dykes of the pond. Because too many mangrove and nipa palms have been cut, the company in close collaboration has started a programme for the replanting of mangroves along the outer edges of the ponds. The company also instructs the boats men to move slowly in narrow channels.

The transport sector both of the industries around Samarinda as well as the ones related to the mining industry has to face increasing complaints from the community because of damage done to riverbank degradation, destruction of inlet constructions or even of fish ponds as a result of collapse of dykes. These effects occur as a result of the waves caused by the movements of ships through the often relatively narrow channels. These impacts may lead to official complaints and companies have to pay compensation to the owners of the shrimp ponds or take preventive measures to ensure that less damage will be done.

The companies in their turn point out to the fact that they have official licenses to sail with large ships through these channels. They also claim that many of the shrimp ponds have been constructed on unsuitable locations and without permission of the competent authorities (Ministry of Forestry) and moreover they point to the fact that most of the shrimp ponds have not maintained a what is called ‘a green belt’ between the pond and the channel which could absorb a large part of the eroding effect of the waves and turbulence caused by the movement of the ships. In some cases dikes are really low and very thin. They may even collapse as a result of waves caused by the wind or the eroding effect of the incoming or outgoing tides. That is the reason why the company in collaboration with the governmental officials has started a programme to ensure smooth operations of the mining company. This programme includes reduction of vessel speed (speedboat, seatruck or rigmove). It also stresses the importance of broadening the green belt between the channel and the shrimp pond and the company has committed itself to fund a rather massive mangrove replanting project with around 5 million seedlings to be planted within a few years. It also promised to construct a new bundwall at a number of locations of about 95 km in total. And finally it aims to assist in the improved construction of water-gates.

By doing so the company hopes to develop better relations with the community and to reduce loss in time and energy in complex complaint procedures which in the end do not solve the problem. It is interesting to see how even in some of the complaint cases, the complicated legal situation is not being solved. Various parties operate on the basis of documents originating from very different institutions. The mining operations take place on the basis an official concession from the highest possible authority in the country. The shrimp pond owners base their claim to legality on a letter handed out by the lowest possible level of the Indonesian administrative system, a village head. And the legality is highly questionable as the official authority over the delta islands’ forest land was never involved in the granting of these rights. However as the issuance of this type of letter has taken place on such a large scale and in fact it has been the foundation of the economic welfare of thousands of people in the area, it is practically impossible to simply discard their these letters as illegal.

The confusion in terms of legality is also obvious in the field. At numerous sites billboards are being put up either in English, Indonesian or in Buginese4 language indicating either to slow down the speed of the boats or ships because there are shrimps ponds ahead while at a very short distance there are also sign posts telling that it is prohibited to construct shrimp ponds at such locations. In addition there are numerous billboards telling people to stay away from installations, that fishing is prohibited, that there are pipe pines beneath or that people have to take care because there are crocodiles.

There is, theoretically, an overwhelming amount of legal instruments, laws, conventions, rules and regulations applicable to the management of natural resources in the Mahakam Delta. They range from articles in the Indonesian constitution (1945), to sectoral laws (in fields like forestry, mining, fishing, water, and spatial planning), to provincial and district’s rules and regulations. In additional there are also relevant international conventions relevant to the area such as the Ramsar Convention (1971) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (1992) to which Indonesia is a signatory (see Simarmata, 2012 for comprehensive overview). Any review however of the actual situation in the delta cannot but come to the conclusion that the implementation of all these legal instruments has been very weak. Not only academic writers have come to that conclusion, also governmental agencies themselves have realized that they have turned a blind eye to the events in the delta in spite of clear evidence that the destruction of the delta’s habitat was happening (Bengen, 2011a,b). On the other hand enterprising individuals people, officials of various departments and private companies have benefitted from this situation. In that sense the Mahakam Delta has been a true resource frontier.

The deplorable situation in the delta and its recognition by government officials finally led to the establishment of a special management team at the provincial level to integrate the core aspects of management of the area. The establishment of this board was announced in October 2011 shortly before the World Delta Summit in Jakarta in November of the same year. The presentation of this initiative was done jointly with a presentation of the activities undertaken by Total E&P Indonesie under its corporate social responsibility (World Delta Summit, 2011). These activities mainly focus on rehabilitation of mangrove forests, and preventive measures to avoid oil spills. Total E&P Indonesie is also strongly in favour of clear spatial planning and zoning of the Mahakam Delta, including some protection zones (Awang Faroek Ishak, 2011a,b; Bengen, 2011a,b). One of the recent regulations is that no local letters, the SPPT letters, may be issued anymore because the area still falls under the jurisdiction of the Forestry Department. While the boundaries of the oil company’s concession are clearly marked, the lands of local people on which they have worked for many years remain unclear. Since then many protest letters have been written to both the provincial and the district government (Safitri, 2011).

Whether or not such initiatives are going to be successful is difficult to say. It will be difficult to undo years of neglect of governmental interference which gave rise to a typical resource frontier type of economy and society even though it differs in one aspect from many other frontier encounters and that is that this delta island frontier was largely uninhabited by an indigenous population. This is one of the reasons why there has never been any resistance from local communities against intruding outsiders. It is also the reason why in an era of increasingly vocal indigenous communities reclaiming traditional land rights, such kinds of encounters do not take place in the delta of the Mahakam (compare e.g. Geiger, 2008).5 Enterprising individuals had ample opportunities to grab land and resources and they were also successful in establishing some form of legitimacy by persuading local village leaders to issue land letters thereby creating a new kind of legal reality that functioned very well under local conditions.

Simarmata (2012) summarizes the key issues of the present situation in terms of legal complexities. First he indicates that legal inconsistencies have greatly contributed to the present situation. Sectoral laws and rules and regulations are often contradictory. Fishing regulations are primarily aimed at protecting small scale fishermen fishing close to the coast (up to three nautical miles). But these regulations conflict with the use of the same area for oil and gas mining because, the latter do not allow any fishing close to mining installations and platforms. Due to a lack of cross referencing between the sector laws and regulations, fishermen and managers of mining operations often get in conflict with one another. Another major source of legal conflicts is the multiplicity of sectors and levels dealing with the Mahakam Delta. Departments of Forestry, of Mining and Fisheries are the most important ones with very different interests and perspectives, ranging initially from lack of interest (Forestry) to extreme interest (Mining) because of the strategic and economic importance of the Mahakam Delta in terms of revenues generated. In terms of governmental levels the situation in Indonesia is complicated as, particular since the fall of President Suharto in May 1998, not all power is vested anymore with the central government in Jakarta. An era of Reformasi of political power has started and a number of laws for regional autonomy have passed. But on top of that, it is in particular the spirit of devolved political power to the regions that has created room to move for local leaders. Instead of waiting for instructions from Jakarta or even from the provincial government, local leaders at the district, sub-district and even the village level are inclined to take on more responsibility than they officially have according to the autonomy laws. An additional complication is also that the degree of regional autonomy is not similar for all sectors. While local level authorities are entitled to deal with forestry and fisheries issues, mining is still part of the jurisdiction of the central authorities. But even within the region, provincial rules and regulations are often not in full accordance with the regulations issued by the lower levels. And, as stated earlier, the Mahakam Delta, as a kind of resource frontier is to some extent characterized by lack of implementation of whatever kind of rules and regulations.

The merits of the margins

Usually river delta’s are densely populated areas due to the abundance of natural resources which attract people, exploiting the resources of the ‘rivers’ hinterland, while at the same time making use of the marine resources and opportunities to trade across the sea. The Mahakam Delta is an exception. The islands in the delta were until very recent uninhabited. The islands constituted a hostile environment for humans and there were few resources to be exploited according to the prevailing perceptions of the environment. The islands were considered as marginal land, or ‘empty land’.

The ‘wake up’ call for the area was the start of the mining exploration and the opening up of the mangrove and nipa forests for shrimp ponds. In spite of the booming economic activities taking place in particular after the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, a part of the Indonesian bureaucracy slept through the alarm clock. As a result of neglecting the ongoing activities, and because of the spirit of time after the fall of President Suharto, new legal realities were created on the islands. Local village heads started to issue so-called ‘land letters’. As a result two different legal realties started to emerge. One is the official paper reality of the delta islands as still being state forest land covered by mangroves and nipa palms and without human habitation, while the other is the on the ground reality of an area largely illegally converted into shrimp ponds, with villages inhabited by thousands of people and a dense network of mining operations, drill platforms, giant installations, and pipelines crossing through the area.

Because the decreasing income from the shrimp ponds in recent years, shrimp farmers are looking for alternative sources of incidental income. In addition to fishing out at sea, claiming compensation from the mining or shipping companies for damage done to their shrimp ponds is another source of income. These conflicts have gradually increased the awareness that the islands in the Mahakam Delta islands are no longer empty or sleeping. They need close supervision, and a regulatory network that will need to solve some of the inconsistencies and internal contradictions on what constitute the legal framework and the perceptions of vested interests.

As yet there seems no end to the exploitable resources as discoveries of new oil and natural gas fields still seem to add to the already available reserves (Beckman, 2003). The government is also taking measures to watch more closely the events in the area by the installation of a new supervisory body.

The recent developments on the islands of the Mahakam Delta also teaches a lesson for other so-called marginal areas, whether they are islands or not. Marginality is not a fixed characteristic of a particular area. It is a specific point of view: an area is only marginal from that perspective. All kinds of factors can change that marginality and turn ‘sleeping land’ into hotspots of economic interests. In addition ‘marginality’ is in terms of types of land classification often a state perspective: the area is marginal from a central political point of view. Local people often do not consider the area as being marginal: it constitutes their basis for economic action and they will grab available opportunities to make the best out of it according to their standards. Also outside actors may see opportunities which may have escaped the attention of sectorial governmental institutions. And if such institutions lack a strong learning attitude, and when denying new realities is no longer an option, the repeated wake-up call may come as an unpleasant surprise with the need of a lot of redressing of complicated situations ahead.

Endnotes

References

- Awang Faroek Ishak, 2011a Awang Faroek Ishak, H. 2011a. Decision of the Governor of East Kalimantan number 660.1/K./2011 on the establishment of Mahakam Delta Management Team, Samarinda, October 2011, (Unofficial Translation).

- Awang Faroek Ishak, 2011b Awang Faroek Ishak, H. 2011b. The East Kalimantan Delta: Opportunity and challenges. From environmental perspective as well as the urgency of integrated management and sustainability. Presention by the Governor of East Kalimantan at the World Delta Summit, Jakarta 21–24, November 2011.

- Beckman, 2003 Beckman, J. 2003. ‘Total expanding Mahakam delta output to increase share of Bontang LNG’. In: Offshore, vol. 63, no. 11.

- Bengen, 2011a Bengen, D.G., Widiarso, D., Ibrahim, M., Suprapto, M.A. 2011. Mangrove Delta Mahakam, Samarinda, P4L.

- Bengen, 2011b Bengen, D.G., M.A. Sardjono and M. Muhdar (2011) Mahakam Delta. A strategic area in the environmental perspective as well as its integrated and sustainable management urgency. BPMIGAS and Total E&P Indonesie.

- Bourgois, 2002 Bourgois, R., et al. 2002. A socio-economic and institutional analysis of Mahakam Delta Stakeholders. Final report to TotalFinaElf. Samarinda (ms.).

- Chaineau et al., 2010 C.H. Chaineau, J. Miné, Suripno The integration of biodiversity conservation with oil and gas exploration in sensitive tropical environments. Biodiversity Conservation, 19 (2010), pp. 587-600

- Dove, 2008 M.R. Dove (Ed.), Southeast Asian Grasslands: Understanding a vernacular landscape, The New York Botanical Garden Press, New York (2008)

- Duval, 2012 Duval, B. 2012. Creative thinking led to 40 years of success in Mahakam, Indonesia. Presentation given at Discovery Thinking at AAPG International Conference and Exhibition, Singapore 16–19, 2012.

- Geiger, 2008 Geiger, D. 2008. Introduction. States, settlers and indigenous communities. In: D. Geiger (ed.) Frontier Encounters. Indigenous Communities and Settlers in Asia and Latin America, pp. 1–75. Copenhagen, IWGIA.

- Legge, 1972 J.D. Legge Sukarno, a Political Biography. Allen Lane Penguin Press, London (1972)

- Lenggono, 2011 Lenggono, P.S., 2011. Ponggawa dan patronase pertembakan di Delta Mahakam: teori pembentukan ekonomi lokal. PhD thesis Bogor Agricultural Institute, Bogor.

- Lindblad, 1989 J.Th. Lindblad The petroleum industry in Indonesia before the second world war. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 25 (2) (1989), pp. 53-77

- MacKinnon, 1996 MacKinnon, K., Hatta, G., Halim, H., Mangalik, A. 1996. The ecology of Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo. [The ecology of Indonesia series, vol. III). Singapore, Periplus Editions.

- Magenda, 1991 B. Magenda East Kalimantan: The decline of a commercial aristocracy. Southeast Asia Study Program, New York (1991)

- Pelras, 1996 C. Pelras The Bugis. Blackwell, Oxford (1996)

- Pelras, 2000 C. Pelras Patron-client ties among the Bugis and Makassarese of South Sulawesi. R. Tol, C. Van Dijk, G. Acciaiolli (Eds.), Authority and enterprise among the peoples of South Sulawesi, Leiden, KITLV Press (2000), pp. 15-54

- Rachman, 2013 Rachman, N.F. 2013. Undoing categorical inequality. Masyarakat adat, agrarian conflicts and struggle for inclusive citizenship in Indonesia. (Presentation given at KITLV, Leiden, 16 June 2013).

- Safitri, 2011 Safitri, M. 2011. Migration and Property in Mangrove Forest. The formation and adaptation of property arrangements of the Buginese in Mahakam Delta, East Kalimantan. Paper presented during the World Delta Summit, Jakarta 21–24, November 2011. (ms.).

- Sidik, 2012 Sidik, A.S. 2012. The changes of mangrove ecosystem in Mahakam Delta, Indonesia. A complex social-environmental pattern of linkages in resources utilization. Paper presentation at Rescopar Scientific Meeting, Universitas Mulawarman. Samarinda, 25–26 February 2009.

- Simarmata, 2012 Simarmata, R. 2012. Indonesian Law and Reality in the Delta. A socio-legal inquiry into laws, local bureaucrats and natural resources management in the Mahakam Delta, East Kalimantan. PhD dissertation. Leiden, Leiden University Press.

- Snelder, 2012 Snelder, D., Persoon, G., 2012. Marginal lands for biofuel feestock production in Southeast Asia. Conflicting views and expectations. JARAK. Leiden (ms.).

- Timmer, 2010 J. Timmer Being seen like the stat. Emulations of legal culture in customary labor and land tenure arrangements in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. American Ethnologist, 37 (4) (2010), pp. 703-712

- Tomascik, 1997 Tomascik, T., Mah, A.J., Nontji, A. Moosa, M.K. 1997. The ecology of the Indonesian seas (part I). [The ecology of Indonesia series, vol. VII]. Singapore, Periplus Editions.

- Vayda, 1996 Vayda, A.P., Sahur, A., 1996 Bugis settlers in East Kalimantan’s Kutai National Park. Their past and present and some possibilities for their future. CIFOR Special Publication. Bogor, CIFOR.

- Wiegeman et al., 2008 K. Wiegeman, K. Hennenberg, U. Fritsche Degraded land and sustainable bioenegry feedstock production. Issue Paper, Darmstadt, Öko-Institut (2008)

- World Delta Summit, 2011 World Delta Summit, 2011 The pulse of delta’s and the fate of our civilization. Conference held in the Balai Sidang Jakarta Convention Center, 21–24 November 2011.