Shapes of fishing gears in relation to the tidal flat bio-organisms and habitat types in Daebu Island region, Gyeonggi Bay

City and Nature Institute, Republic of Korea

Institution for Marine and Island Cultures, Mokpo National University, Republic of Korea landskhong@gmail.com

Jeonnam Development Institute, Republic of Korea

Abstract

This is a base research to analyze the evolution of fishing gear shapes in response to the types of marine benthic organisms and ‘getbatang-harvesting tidal flat’ in Daebu Island in Gyeonggi Bay. Daebu Island has variety of relatively well preserved natural coast lines and fishing gears. Hand hoes were divided into two categories, one for manila clam collecting and the other for mud octopus collecting. The ones used to catch mud octopuses are much larger and heavier. Clear distinction of shapes and forms were found even among the hand hoes used for collecting the similar types of catch, depending on the getbatang that they were used on. Also, mud octopus hand hoes varied in shapes and forms depending on the region that they were found in and the sex of the user. Fishing gears of other islands in Gyeonggi Bay, Oi Island, Jangbong Island and Ganghwa–Donggum Island, showed differences as getbatang varies, and each region sometimes had different uses of the same tool from each other. It is necessary that we continue the investigation and analysis on the relationship between the shape of fishing gears, organisms, and getbatang sediment conditions before the traditional fishing gears disappear any further.

Keywords

Daebu Island, Fishing gear, Fishing tools, Getbatang, Tidal flat, Traditional fishing

Introduction

Culture, more specifically the life history and relationship history, of regional communities can vary based on the surrounding environment; in case of fishing villages, differences in the marine and coastal environments can be associated with distinction of marine culture (Ko, 2004; Cho, 2009; Kim, 2010; Je, 2012). There are some cases in which all villages along one coast share the same culture, but one can also find cases where two adjacent villages have completely different, employing completely different sets of fishing gears. This is mainly because they have different ‘Getbatang (a people of Gyeonggi Bay region call tidal flats as getbatang. It not only means ‘tidal flat’ itself, but also includes various characteristics of tidal flats as well)’ where tidal flat is been using by fishermen as harvest area. Because getbatang are different, the marine lives are different, which means that the characteristics of ecosystem (and biodiversity) may also vary, resulting in the evolution of the shapes of fishing gears, and therefore the culture (Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, 2002a,b; Kim, 2010).

Traditionally, biodiversity and cultural diversity have been considered as deeply related (Ramsar Regional Center-East Asia, 2012). Like biodiversity, cultural diversity is systematic (Je, 2012). An island’s landscape possesses variety of cultural resources created by the interactions of organism, nature, and humanity (Hong, 2011). Therefore, numerous tangible and intangible resources that residents of insular regions have created, utilized, and maintained would be great ingredients of cultural diversity (Hong, 2008; Hong et al., 2014).

Such culture is also useful in nature conservation, it contains insightful ecological knowledge passed down for generations. Japanese call traditional marine ecological knowledge ‘satoumi,’ and are putting great efforts into proper organization and handing down of the knowledge (Tsujii and Sasagawa, 2012). This is an effort to not only utilize traditional knowledge and skills of fishing villages in marine management to overcome serious problems in coastal environment of Japan, but also is an attempt to introduce Japanese traditional knowledge to international arena as a new marine management technique. Right now, they are gathering and organizing traditional marine management techniques and culture in regional unit. Japanese government hosted independent seminars and meetings about ‘satoumi’ (Japanese word regarding coastal village) at the 10th Conference of the Parties (COP 10, 2010) to the Convention on Biological Diversity, which was held in Nagoya, Japan.

To humanity, ocean is environment and a culture. People who live in the oceanic environment have lived a life associated with ocean, adapting to the marine environment, as well as creating a resulting culture (Yoon, 2001). Fishermen, whose livelihood is totally dependent upon the tidal ebbs and flows, have extensive and systematic knowledge on tidal flats and marine ecosystem. Their folk knowledge is based on experiences that were accumulated and passed down for generation after a generation. Fishermen’s understanding on tide can be seen on the symbolic representation system of ‘high tide’ (Ju, 2006). Tidal flats of south and west coast of Korea have always been something more than a mere natural environment or a place to earn a living (Ko, 2004). They have been the place of living, sphere of living, and religious and ideological tool used toward fulfillment of the world views that its inhabitants aspire. People formed the property of tidal flats by assigning the concept of their lives and the surrounding environment to them (Cho, 2009). This is a work designed to shed a light to the life and relationship history between people, tidal flats, and organisms that live within tidal flats. We have chosen to study fishing gears as the first step to gathering, organizing, analyzing, preserving, and managing the valuable traditional knowledge about the marine cultural heritages that fishermen have.

Study area and methods

This research study was conducted in the Gyeonggi Bay area, focusing on the relationship between the benthic organisms living in tidal flats and the culture of the region by collecting the fishing gears and conducting investigations on the fishing gears (Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, 2002b). More specifically, the study had been concentrated upon the hand hoes and fishing gears used in digging and turning the sediments.

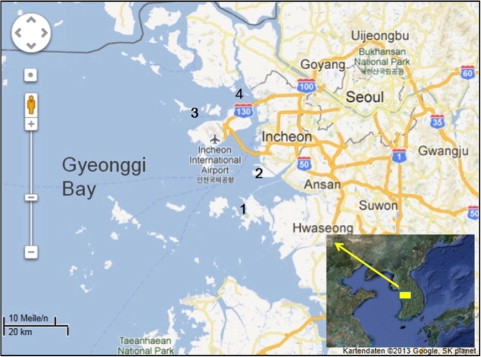

This study was conducted by visiting the fishing villages in Gyeonggi Bay area that are engaged in tidal flat fishing, concentrating mostly on Daebu Island, Ansan City in Gyeonggi Province (Fig. 1). Daebu Island still possesses extensive and rias coastal line, and though it is only a single island, it contains variety of marine environment, which makes it easier to collect multitude of data in one region. In addition, the fishing gears of Oi Island of Gyeonggi Province and Ganghwa-Donggum Island and Jangbong Island of Incheon Metropolitan City in the bay were included.

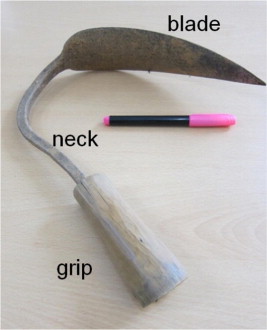

As for the shapes and forms of the hand hoes, the dimensions of blade, neck, and grip (Fig. 2) were measured to analyze the relationship between its form and the getbatang. For the investigation on fishing methods, the sites and/or interviewed the regional resident representatives (2 in Daebu Island, 1 in Ganghwa-Donggum Island) and cultural experts (1 from Gyeonggi Cultural Foundation) had been either visited to gather data. Analysis on getbatang sedimentary environment is not included in this paper.

Results and discussions

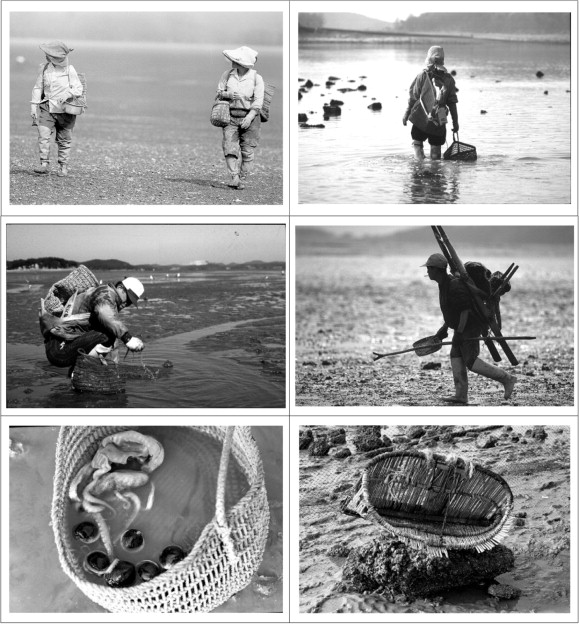

In Korea, harvesting activities on tidal flat are handed down among people as marine culture (Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, 2002a). Fishing gears used in tidal flats are divided into four different categories: (1) collection tools, (2) de-shelling tools, (3) containers, and (4) carrying tools (Fig. 3). As of oyster collection, there is one more category of tools used for water draining after de-shelling.

Collection tools vary by the getbatang and the object of collection, such as manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum), venus clam (Cyclinasinensis), surf clam (Mactrachinensis), hard clam (Meretrix spp.), and mud octopus (Octopus minor). In Daebu Island, it was found that different types of collection tool were used for different getbatang. These fishing gears have evolved and developed to optimize the collecting, using the materials that were available at the time of their development. Hand hoes used in tidal flats (for collection of shellfish) differed from the ones used on field. Collection gears were paired with containers (Fig. 4).

Collection fishing tools

Fishing gears for tidal shell fishes differ by the type of collection species, because the characteristics of getbatang vary by species. Also, some variations are found by the individual users, the blacksmith shop where the gear was made, and the sex of the user. When and if a specific shape of a tool is found to be more effective in collection, it eventually becomes the uniform standard of that region. There are cases where people did not employ any collection tools in gathering clams in shallow area or catching lugworms and mud octopuses under deep sediments. I will not further elaborate on the use of bare hands in this work.

Sharper tools are much easier to use in tidal flats. Collection gears used in mud tidal flats tend to have narrower blade, because the mud would get on the wider blade, making it more difficult to use. After long use, people take their tools to blacksmiths to be sharpened and fixed, and that could also be when the shape of tools can change slightly. Conditions of the tidal flats can also affect which kinds of tools are used. For example, hand hoes vary in shapes by different uses, in such that blade of mud hoes is much sharper and narrower than that of field hoes. These characteristics make it much easier to distinguish one from the other (Fig. 4).Hand hoes used on sandy tidal flats have blades almost as thick as the farming hoes and are even a bit bigger, for they have to be durable enough for scraping the sediment. However, their shapes vary a bit by the amount of rock or pebbles mixed in on sandy tidal flats or the amount of moisture content. Blade of hand hoes used on mud tidal flats is long and curved, forming the perfect angle to make it efficient to turn mud over. Women tend to use specific hand hoes, while men use shovel to catch small octopuses.

Hand hoes

Manila clam hand hoes

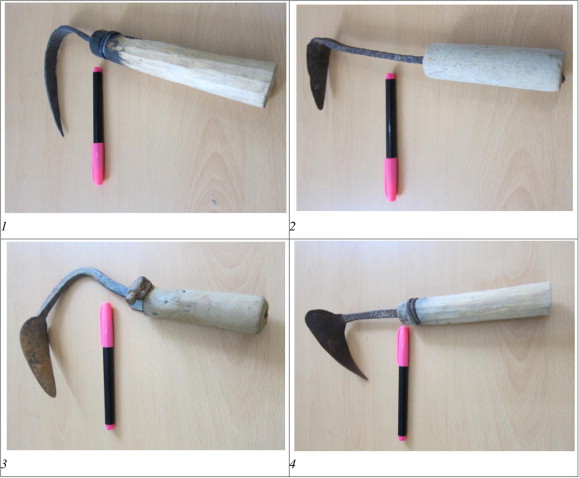

Manila clams are spread from intertidal region to shallow sea. Neither the ultra-fine grained mud tidal flat nor the tidal flats with high sand content are fitting habitats for them. They usually thrive in on sandy or pebbly tidal flats with high mud contents. Therefore, there are multitudes of hand hoe types to be matched with varying characteristics of getbatang. Rock hand hoes are used on tidal flats with a lot of rocks pebbles, for they are convenient for rooting about the rocks (Fig. 5-1). They are strong and narrow as a whole, and the blade and the neck are in an almost identical width and thickness. On the other hand, hand hoes used on sandy tidal flats with high water content have small and narrow blade, so that it would require less amount of strength to use (Fig. 5-2). Even the regular field hand hoes are divided into two different types: ones with blade on only one side, and the ones with blade on both sides. It seems that they reflect the regional characteristics.

The one on Fig. 5-4 is from Daebu Island, and the one on Fig. 5-3 was made in Oi Island. The one with double blades had long and deeply curved neck with short grip (Table 1). In contrast, water hand hoes have longest grip of all hand hoes, and are used to collect water manila clams. Water manila clam are the manila clams living puddles on mud tidal flats. To catch them, one would have to dig under the puddle, so it seems logical to use the hand hoes with longest neck (Table 1).

| Type | Blade length (cm) | Blade width (cm) | Neck length(cm) | Grip length (cm) | Weight (g) | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mudoctopus hand hoe | 1. Hand hoe for men | 34.5 | 8.5 | 20.4 | 21.7 | 1785 | |

| 2. Hand hoe for women | 26.7 | 5.4 | 12.4 | 20.9 | 875 | ||

| 3. Hand hoe from OiIsland | 24.2 | 7.0 | 22.4 | 11.8 | 710 | Blade is in leaf shape, long and curved neck | |

| Manila clam hand hoe | 1. Rock hand hoe | 7.8 | 1.9 | 9.2 | 19.8 | 320 | Neck and blade are in same width |

| 2. Water hand hoe | 13.8 | 5.8 | 11.4 | 16.7 | 225 | Long and straight neck | |

| 3. Hand hoe from OiIsland | 13.2 | 4.6 | 19.7 | 12.3 | 320 | Blade is in leaf shape, long and curved neck | |

| 4. Hand hoe | 10.9 | 3.7 | 17.2 | 11.5 | 240 | ||

Mud octopus hoes

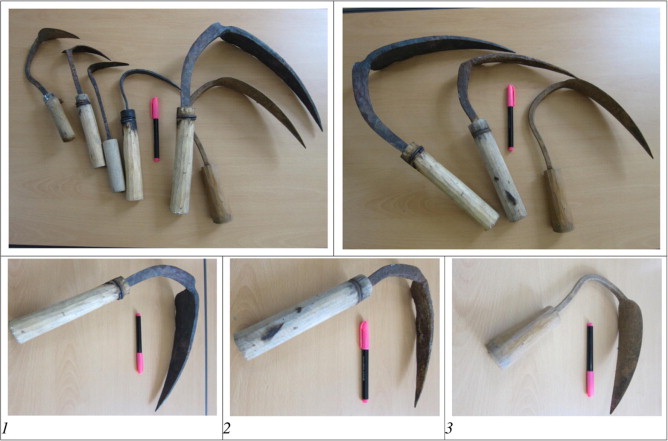

Mud octopus hoes are similar in its use with ‘ssuge (mud hook)’ in that they are used to turn the mud and sand over, rather than dig it. They are the heaviest and largest of the hand hoes used in tidal flats. This is a logical choice, for small octopuses are strong and they usually live in deep tidal flats. The hand hoe used in catching small octopuses naturally need to be the ones that could add the weight, making them the strongest and the heaviest of all hoes. These hoes were usually used by women, but some of them weighted about 2 kg, which seems little too heavy or women’s use. They are much larger than the manila clam hoes and the blade is especially large and long (Table 1). However, double blade hoes have long and curved neck with short grip, just like the manila clam hoes (Fig. 6-1–3).

Razor clam hand hoe

We have not been able to find a razor clam hoe in this research. According to Siheung City History record, (The Compilation Committee for Siheung City History, 2007), razor clam lives in a deep hole, so the blade of razor clam hand hoes is very long. One can scoop a razor clam up from a hole by shoving the long and thin hoe made out of cast iron onto the tidal flat. The mid-section is curved in a circular shape, so that the blade can easily get under the ground. People usually buy the hoes in markets, and people in Jungwang village of Siheung City used ‘ssuge’ instead to catch razor clams.’

Ssuge

In Daebu Island, there is the tool with two strong hooks used to turn ground to catch razor clams and lugworms (Fig. 7). In Ganghwa Island, they are used to collect lugworms living in mud tidal flats with high mud contents (Fig. 8). Ssuges have long blade and short grip because they go deep into the mud and turn the sediments over as they are pulled out. In Ganhwa–Donggum Island, ssuges that are like the one on top left side of the Fig. 8 were mainly used when lugworms were the main catch of the island. However, as the venus clam became the new main catch, the hoes that look like the one in Fig. 8 became much more popular.

Ssuge has been used to catch octopuses only in Daebu Island. In the other areas on the west coast of Korea, fishermen generally use small shovel (Ko, 2009). In Donggum Island, people usually do not use clam hoes. Also, they only use their bare hands or ssuge even when they are catching small octopuses. This culture is the direct result of having an ultra-fine grained tidal flat.

In Jangbong Island, they do not use the word ‘ssuge’. Both ssuge and hand hoe are just called ‘homi’ (hand hoes) such lugworm hand hoe and long hand hoe, and though they were mostly used in catching lugworms in the past, they are now used in catching small octopuses.

Ggalggori (hand rake)

It is a tool with 4–5 thick bent steel tines that is used in collecting shellfishes, such as surf clams and manila clams. People usually hand make these hand rakes. When one scrapes tidal flat with low mud contents using a hand rake, it separates the clams from the sediment (The Compilation Committee for Siheung City History, 2007). There are newly developed hand rakes for the tidal flat ecotourism purpose, but they are too light for long hours of clam collection. Hand rakes used in Gyeonggi Bay area are generally uniform in shape (Fig. 9).

Shovel (spade or small spade)

Mud octopus shovels are mostly used by men, and they have shorter handle and narrower blade than the regular shovels. Local people call it ‘garae’ or ‘jonggarae’. They are used to turn over the sediments of the tidal flats, and not significant differences in shape could be found among the mud octopus shovels in Gyeonggi Bay area (Fig. 10).

Ggeurengi

Ggeurengi are used in collecting hard clams from sandy tidal flats. The clams get caught on the bottom metal part as the fishermen drive ggeurengi over the tidal flat. This bottom part is the most essential part of ggeurengi, and it can be adjusted to suit the specific characteristics of getbatang and the depth of the mud that clams live in. It is a bit difficult to use, so there are not very many people who could use it properly in Daebu Island. The hard clam population is not very high in Daebu Island, so it does not seem to have been the main source of the fishermen’s income, but they are still sold for higher price, so a lot of fishermen envy those who can use ggeurengi (Fig. 11).

Containers

The smaller-mesh baskets are called ‘jongtaegi’ and the larger mesh rucksack ones are called ‘mangtaegi’. One would usually place clams that he/she collected in jongtaegi first, and then later move them into mangtaegi. In the past, both jongtaegi and mangtaegi were made of hay, but since nylon strings were introduced, people started making them with nylon strings, for they last much longer than the ones made out of hay in salt water. Most of the inhabitants could make mangtaegi and jongtaegi, and some would still make them for themselves so that they could make them in the exact size that they desire (Fig. 12).

Jongtaegi

They are used in holding, washing, and carrying the oysters and clams. In the olden days, they were made out of hay strings or kudzu vines, but since after the war, people used more durable materials such as telephone cables (The Compilation Committee for Siheung City History, 2007). Some still use the ones made out of nylon strings, but for the most part, plastic buckets have replaced them (Fig. 12).

Mangtaegi

Like jongtaegi, they were used to be made with organic materials like bamboo, but people mostly use ones made of nylon strings now. They are also used in holding fishes, and though they are originally designed to hold fishes and clams, they are more often used in carrying them (Fig. 12).

Conclusion

A European naturalist once said, “Death of an old African man can compare to destruction of a natural history museum in Europe.” Right now, fishing villages and marine culture of Korea is on to the same path. Even the fishermen in their 50s do not possess the complete knowledge of traditional fishing methods and marine cultures. Nowadays, one would have to find people in their 70s to look for someone who has extensive knowledge over disappearing traditional marine culture. Since these memories and experience are not naturally being passed down to the younger generations, like they used in the olden days, it is crucial to collect and record their knowledge and experiences. Studies on fishing gears have to be much more specific and scientific, for their shapes and forms greatly vary upon ‘getbatang’, region, personal tastes, and the creativity of blacksmith who made them. Since it requires the process of organizing the precious knowledge of individual fishermen, marine culture experts have a big role to play. Culture is not simply limited to human life history (UNESCO, 2008). It is the history of relationship between environment (as well as biological resource), those that live in it, and humanity. For this reason, a motion regarding island biocultural diversity and its traditional ecological knowledge was accepted as IUCN Resolution (IUCN Resolution 5.115) in World Conservation Congress at Jeju in 2012 (Hong et al., 2013). Moreover, its initiative is starting in international networking in Asia–Pacific regions. Cultures and human use on marine biological resource is important information that should be shared with international network for keeping their sustainable conservation. Concept and philosophy regarding ‘bioculture and its diversity’ (Maffi, 2001) and its land(sea)scape (Hong et al., 2014), therefore, are emerging as important issue in both biological diversity and cultural diversity.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted as a part of “National Survey of Tidal Flats in KOREA” of the Ministry of Land, Transport, and Maritime Affairs. This work was also supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant (NRF-2009-361-A00007). We are grateful to local people, especially four persons; Mrs. Inmo Choi, Choonil Choi, Sunggu Jung and Jongsun Kim who live in Daebu Island for talking about their marine and coastal culture and collecting fishing gears.

References

- Cho, 2009 K.M. Cho A consideration on the people’s conceptualization of tidal flat and human life – on the case in Youngsan river basin, Southwest coast and islands. J. Isl. Cult., 33 (2009), pp. 103-139. (In Korean with English abstract)

- Hong et al., 2013 S.-K. Hong, L. Maffi, G. Oviedo, H. Mastuda, J.-E. Kim Island biocultural diversity initiative. e-Bulletin, 7 (1) (2013), pp. 7-9. (cited from INTECOL website, www.intecol.org)

- Hong et al., 2014 Hong, S.-K., Bogaert, J., Min, Q., 2014. Biocultural landscapes. Springer-Verlag, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- Hong, 2011 S.-K. Hong Eco-cultural diversity in island and coastal landscapes: conservation and development. S.K. Hong, J. Wu, J.E. Kim, N. Nakagoshi (Eds.), Landscape Ecology in Asian Cultures, Springer, Tokyo (2011), pp. 11-28

- Hong, 2008 S.-K. Hong What we can do for island culture research? – Ecological imagination and multi-disciplinary communication. J. Isl. Cult., 32 (2008), pp. 123-156. (In Korean with English abstract)

- Je, 2012 J.G. Je Crisis of marine biological resources and seafood culture conservation due to loss of tidal flats. J. Isl. Cult., 40 (2012), pp. 357-374. (In Korean with English abstract)

- Ju, 2006 G.H. Ju Dolsan-divine Golden Net from the God. Dulnyouk, Paju (2006), p. 712

- Kim, 2010 J. Kim Encyclopedia of South Korea’s Tidal Flat Culture. EWHO (2010)

- Ko, 2009 K.-N. Ko Fishing tool and method of common octopus. S.-M. Na, K.-M. Cho, K.-M. Ko, K.-Y. Lee, Y.-S. Lee, J. Kim, S.-I. Hong (Eds.), West Sea and Tidal Flat, Kyungin Publishing, Seoul (2009), pp. 87-110. (In Korean)

- Ko, 2004 K.-M. Ko Fishing tools and methods in estuaries in the Shandong Peninsula. J. Isl. Cult., 33 (2004), pp. 257-315. (In Korean with English abstract)

- Maffi, 2001 L. Maffi On Biocultural Diversity Linking Language, Knowledge, and the Environment. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington (2001), p. 578

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, 2002a Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, 2002. Fishing Gear of Korea. p. 580 (In Korean).

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, 2002b Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, 2002. Korean Maritime Culture 2, the West Sea Area, vol. 1. Institute of Islands Culture, Mokpo National University (Korean).

- Ramsar Regional Center-East Asia, 2012 Ramsar Regional Center-East Asia, 2012. The Changwon Declaration in Action for the Wise Use of Wetlands, Report of the Meeting of the Changwon Declaration Network on Human Well-Being and Wetlands (2009–2011), p. 200.

- The Compilation Committee for Siheung City History, 2007 The Compilation Committee for Siheung City History, 2007. Life and Works of Siheung People in the Coast. Siheung City, History 6, 373 (In Korean).

- Tsujii and Sasagawa, 2012 T. Tsujii, K. Sasagawa Examples of the cultures and technologies of wetlands in Japan relationships with local people and communities. Wetland International (2012), p. 72

- UNESCO, 2008 UNESCO, 2008. Links Between Biological and Cultural Diversity: Concepts, Methods and Experiences. Report of an International Workshop, UNESCO, Paris.

- Yoon, 2001 Yoon, M.C., 2001. Ancient East Asia marine network and cultural exchanges. In: International Symposium, Prospects and Challenges of the 21st Century, East Asia, Marine Life, Culture, Economy, Network Formation Proceedings. pp. 96–120.