Lessons from Dish for a Hundred Years: Okinawa Longevity, islandness, fudo, and sustainability

Abstract

What lessons have we learned from the changing landscape of the food habitus in Okinawa? This study focuses on the narrative of a centenarian regarding his childhood memories of food. Food is closely related to the environment; hence, inhabitants internalize their environment through food habitus. Okinawa was famous for its longevity, but now, owing to globalization and Americanization, it has lost its prestigious status. Nostalgically remembering the past is not enough to create a sustainable future. We need to notice the importance of the present: the present will be the past when seen from the viewpoint of the future. With such transition of standpoint, the present food habitus should be viewed differently. Our centenarian’s long life resulted from his life on the island. Islandness, or fudo in this study, supported his hundred years of life. However, repeating his life is impossible for us. We can look our past and future in order to observe our present differently. The centenarians’ childhood narratives enabled us to realize this.

Keywords

Okinawa, Longevity, Food, Islandness, Fudo, Sustainability

1. Dish for a hundred years, an installation

On a large screen at an installation booth, an interview movie of Shinfuku-san1, an Okinawan centenarian, is displayed (Fig. 1). He says that he cannot forget the taste of sweet potatoes, which he ate as a child. Despite his age, he had vivid memories of food from childhood.

This is the scenery of an installation that belongs to our serial project “Dish for a hundred Years (100才ごはん),” undertaken in 2018–2020 (Terada, 2022). This project is a transdisciplinary attempt to achieve sustainability. It comprises several activities, including movie-making, screenings, workshops, exhibitions, and other social commitments. The main venue was Okinawa. This study aims to promote the recognition of food and the future of ordinary people, focusing on the food habitus in Okinawa.

Until the early 20th century, Okinawa was famous for its inhabitant’s longevity. In the mid-1980s, it enjoyed the longest life expectancy in Japan worldwide. However, this status suddenly changed, and the rating of the longest life expectancy dropped drastically; at the beginning of the 2000s, the ranking of the number of years a male newborn was expected to live declined to the middle position in the country. This was a huge shock to the Okinawan people. Changes in social circumstances, especially the Americanization of food, are presupposed as causes. What kind of intervention can improve this situation? Increased life expectancies may strengthen social sustainability. Longevity is related to the environment, hence, it is an issue of environmental change. Longevity is a fundamental element of social sustainability. This project aims to rethink ordinary people’s tendencies toward future sustainability by focusing on individual longevity.

2. Shinfuku-san’s narrative of food

The installation focuses on sweet potato as Shinfuku-san’s “dish for a hundred years.” However, this does not mean he ate sweet potatoes to live long. Certainly, when he ate sweet potatoes in his childhood, he did not even imagine that he would live more than a century afterward. At the same time, from a present-day perspective, he has lived for more than a hundred years as a matter of fact. No one knows whether one will live for over a hundred years. Only when they live more than a hundred years and look back their childhood, the dishes they ate can be considered as their “dish for a hundred years.”

Shinfuku-san, whose full name is Tamaki Shinfuku-san (玉城深福)2, celebrated his centenary in September 2016. He lives in Ohgimi(大宜味)village in northern Okinawa Island. In the island, the village is famous for having many centenarians. He lives in his house with his wife, son, and daughter. He continues to work in a shiikwaasa-lime (Citrus depressa) orchard every morning (Fig. 2).

When asked about his memory of food, he immediately answered that he could not forget the taste of sweet potatoes he had eaten during his childhood:

What I remember when I am asked about the best taste of my childhood is certainly the taste of sweet potatoes. We stored sweet potatoes in our storage. It was delicious, especially when they had just started to sprout (because they were a little dehydrated, and hence, the sweetness was condensed). Our family grew sweet potatoes in half the paddy fields. The other half was used for double cropping of rice. I remember the taste. Nowadays, in town, I often see baked sweet potatoes sold in shops. Every time I eat it, it reminds me of my childhood tastes.

The centenarian describes the taste of sweet potato of his childhood well, and his daughter adds, while laughing, that he is so accustomed to baked sweet potato, he never misses a chance to buy it whenever he finds it in a shop. This indicates that the memory of food lasts for a long time, and might even stay be remembered for almost a hundred years.

3. Longevity in Okinawa

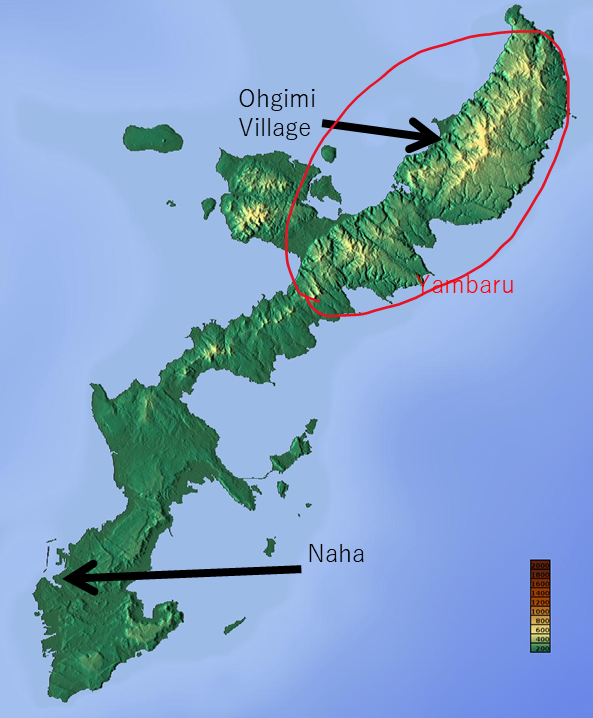

Okinawa is well known for its longevity. In particular, Yambaru, a conventional area to which Ohgimi Village belongs and where Shinfuku-san grew up and lived, is famous as there were many people who lived for over a hundred years.

This Okinawan phenomenon has made scientists worldwide interested. In the 1970s, medical scientists, including Kondo Shoji (近藤正二) of Tohoku University or Alexsander Leaf of the Harvard Medical School (Sakihara, 2000: 44), conducted a survey to thoroughly understand the situation. The National Geographic Society supported the survey of the latter and a comparative analysis between Okinawa and other areas of longevity, such as the Caucasus Mountains, the Hunza Valley of Pakistan, and the foothills of the Andes. In his study, Leaf insisted on the importance of food and emphasized that vegetables and low-fat ingredients play key roles (Vitello, 2013).

In the 2000s, Okinawa was featured as a “blue zone.” The blue zone is the nickname for the place with the greatest number of long-lived people (Buettner, 2008: 25ff.). Gianni Pes, an Italian doctor and medical statistician, and Michael Poulain, a Belgian demographer, declared this name in 2004. Primarily, those scientists thought that it was a “zone” and only Sardinia Island, Italy, deserved it. However, these scientists and other specialists added Okinawa, Loma Linda (California), and Nicoya Peninsula (Costa Rica) later.

Okinawa’s longevity is highlighted in several books and articles. The Willcox brothers and Suzuki, all medical scientists, published two books on the longevity of this island: The Okinawa Program: How the World’s Longest-Lived People Achieve Everlasting Health—and How You Can Too. (Willcox et al., 2001) and The Okinawa Diet Plan: Get Leaner, Live Longer, and Never Feel Hungry (Willcox et al., 2004). The Blue Zones: Lessons for Living Longer from the People Who’ve Lived the Longest features the Okinawa case—especially centenarians in Ohgimi—intensively (Buettner, 2008).

In the course of time, a lot of anthropological investigations were conducted in Okinawa. Their research topics and methods range widely, including the way of life, physical factors, social networks, mental tendencies, nutrition and individual nutrition history, and family conditions. A medical sociologist, Sakihara Seizo (崎原盛造, 2000) argued that food is an important element, but the contributions of other elements are also significan. He believed that the natural environment and social conditions are important in realizing a long life. His field research revealed that social support, rather than family support, is crucial, and a particular personality or mental tendency might lead an individual to live longer. Additionally, cultural values, which evaluate long life as a precious aim, might help motivate people to live long.

Although there are many findings, it is difficult to discuss them. In the books and articles mentioned above, it is indicated—in some cases explicitly and otherwise implicitly—that the true “cause” cannot be addressed. As Suzuki (2001) says, long-lived people do not intend to live for more than a hundred years. This is not a consequence of intention. Longevity is the consequence of a complex pathway; no one can evaluate the true cause of longevity. Therefore, longevity is a product of chance rather than a necessary result.

4. Longevity, islandness, and fudo (風土)

Interestingly, some longevity specialists who conducted field surveys in Okinawa used the term fudo in a report arguing for long life there. The title of an article by Sakihara (2000) reads ‘Longevity of Okinawa, environment, and fudo (「沖縄の気候・風土と長寿」)’ and that of Suzuki Makoto (鈴木信, 2001) reads ‘Lifestyle habit and fudo of Okinawa, the long-life area (「長寿地域沖縄県の風土、生活習慣」)’—both authors are professor emeritus of department of medicine of the Ryukyu University, Okinawa. I think the notion of fudo might have a specific relation with the notion of “islandness,” and it might enrich the argument. Therefore, hereby I introduce the fudo concept to the problem of what is characteristic of island regarding longevity in Okinawa.

Fudo is an East Asian philosophical concept of environment. This word consists of fu (wind) and do (soil). In this usage, wind and soil are metonymies for the natural environment; however, fu has the connotation of something which is perceived by human beings. The wind is invisible and helps us sense air flux, as wind is a human perception. The term “fudo” emphasized this aspect.3

The notion of environment has two aspects: objective and subjective. Natural science presupposes that the environment is objective: it can be measured quantitatively and exists independently from the observer’s subjecthood. But at the same time, in everyday experience, environment is understood as things which cannot be separated from observer’s view. The English term “environment” has these two meanings and is sometimes confusing. In East Asian languages, however, special terms represent the subjective aspect of the surroundings; fudo is one such term.

The word fudo has its roots in ancient Chinese usage, and, throughout history, it has spread out into the “Sinographic” area of East Asia, including Korea and Japan. In the modern and contemporary era, Japanese philosopher Watsuji Tetsuro (和辻哲郎, 1889–1960) and French Philosopher Augustin Berque (1942–) elaborate on it as an ontological and environmental concept (Watsuji, 1935–1962; Berque, 1986; 1988; Terada, 2023a, 2023b).

Although no definite consensus exists on the problem of islandness, it seems that islandness can be interpreted as a phenomenon of fudo, especially when we consider the aspect of islandness in terms of the inhabitants’ life-world. Adam Grydehøj (2018) emphasizes that legibility and human imagination are important in making islandness and says that the “mental islanding” process is often seen in history. In this sense, we can say that thinking of an island as an island is fudo. Alberto del Campo Tejedor and Esteban Ruiz-Ballesteros (2020) argued that rethinking the dichotomy of the physical and objective dimensions of islandness is necessary and that more focus should be given to its lived and experienced dimensions. By declaring the term “relational turn,” they emphasize the importance of the elements that drive the relation. As islandness is a complex social phenomenon, the boundaries between myth and reality, fact and inner imagination, and material and mental elements should be analyzed together. Similarly, as for fudo, Augustin Berque calls his study of fudo mesology (mésologie), namely the study of the middle, the non-dual condition. This indicates that the aim of the study on fudo was the same as the study on islandness.

In their studies, which have the term fudo in the title, Sakihara (2000) and Suzuki (2001) analyzed various topics: climate, temperature, personality, regional illness, social network, history, ingredients, culture, and social stress. As fudo is a complex phenomenon, an interdisciplinary approach is necessary, like that for islandness.

5. Shinfuku-san’s life and Yambaru fudo

Shinfuku-san’s longevity is closely related to Yambaru fudo. His entire life was inseparably connected to this area. In several books which feature the life history of long-lived persons in Ohgimi village, Shinfuku-san recalls his life (Popurasha henshubu, 2011: 56–58; Kinjo, 2023: 32–35). Referring to these oral memoirs and other sources including interviews done by the author, we will examine how his long life and Yambaru fudo are interrelated.

Shinfuku-san was born on May 28, 1916 in Yahabi (or Yakabi, 屋嘉比) hamlet, Takazato settlement, Ohgimi village, where he still lives. Ohgimi village belongs to the northern part of Okinawa island, called “Yambaru (やんばる, 山原).” The two words consist of the term, namely “yama (山, mountain)” and “baru (原, field),” indicating this area is mountainous and the population is mainly found in the seashore (Fig. 3a).

Source: a) http://www.maps-for-free.com/, Creative Commons CC0. b) Google Earth.

From the present “Tokyo-centric” view, Ohgimi village is one of the remotest places in Japan; from Tokyo, it takes around two and a half hours by airplane and one and a half hours by car, five hours in total, to get there. The hamlets of Ohgimi Village are small, and the population density is currently low in this area. In 2016, the Takazato settlement had 135 households and a population of 285. Population density per km2 was 351. The present average population density in Japan is 862, and that of Okinawa is 651; Takazato seems to be too depopulated in Japan. In contrast, when Shinfuku-san was born in 1926, it had 167 households and a population of 893, with a population density of 1,102 (Ohgimisonshi hensan iinkai, 2016: 80). It may be perceived as the most peripheral area in Japan today; however, from a historical perspective, this is not always the case.

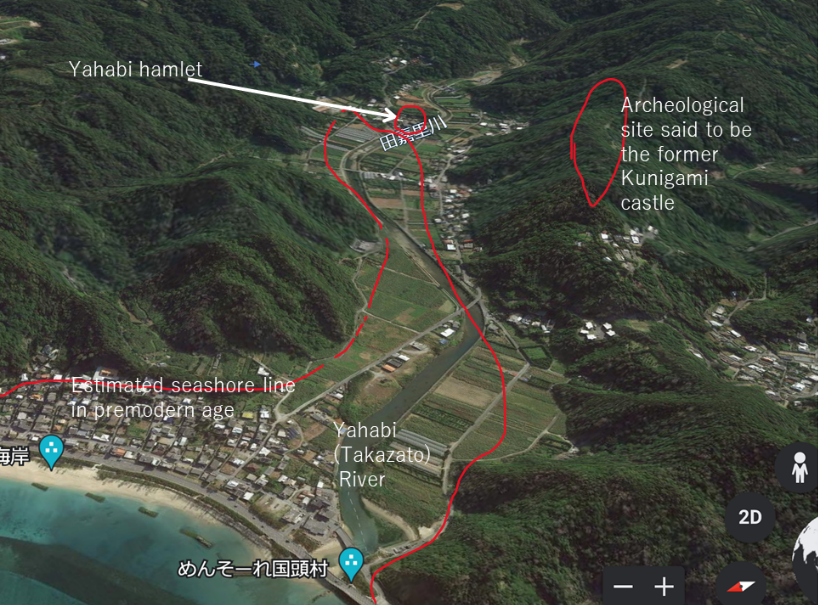

Ohgimi Village has more than a thousand years of history. The first archeological site of hunter-gatherers dates back to the seventh or eighth century AD (Ohgimison kyouikuiinkai, 2010: 3). The name of the Yahabi River Basin, where the Yahabi hamlet exists, appears in the historical record of the Middle Ages. The area belongs to the Kunigami Majiri (国頭間切) district. The name of Yahabi appears in the famous court document Omorosaushi (『おもろさうし』, Collected Omoro Songs, compiled in 1531–1623; Vol. 13–921[176], Vol. 13–927[182], Hokama and Saigo 1972: 318–319, Higuchi 1987: 220).

Between the 14th and 15th centuries, the Yahabi river basin was the home of Kunigami Aji (国頭按司), who ruled a small territory of the northern part of Yambaru, and hence, was a political center there (Ohgimison kyouikuiinkai, 2010: 13–14, Higuchi 1987: 213). At that time, the trade ship connected the Yahabi harbor, which is supposed to have located in the mouth of Yahabi river, with other ports in the Okinawan mainland and neighboring islands, including Amami (奄美) Island (Tsuha et al., 1982) (Fig 3b). Even in the modern period, around the beginning of the twentieth century, lumber and charcoal were exported to other islands by ship. Based on the name of the place, the ship was called “Yambaru-ship (やんばる船)” (Ohgimison kyouikuiinkai, 2010: 19).

The name “Shinfuku” means deep (jp: shin, cn: shēn, 深) happiness (jp: fuku, cn: fú, 福). It consists of two Shinograms and sounds like a Chinese name rather than an indigenous Okinawan or Japanese name. As we discuss in the next section, Chinese culture deeply influences the Okinawan culture. In the early modern era, from around the 15th to 19th centuries, Okinawa—or then Ryukyu—was an independent kingdom. In contrast, after the 19th century, the Japanese government took away its independence, and it was forced to be a part of Japan. Ryukyu kingdom had a close relationship with China by being included in its tributary system (冊封体制). However, Japanification progressed with much contradiction during the later 19th and early 20th centuries. The fact that Shinfuku-san has a Chinese-like name reveals Okinawa’s ambivalence toward China and Japan during modernity.

The Second World War seriously affected Shinfuku-san’s youth and adolescence; the Japanese army conscripted him as a civilian employee, sent him to Bougainville Island in the Pacific, and he experienced hardship during the war. When the war ended in 1945, he returned to Yahabi, his home hamlet, but after a while, he moved to Naha, the capital of Okinawa Prefecture, with leaving his family in the village in order to earn money for his children’s higher education. In Naha he engaged in a transportation business throughout his middle ages. When he retired in the 1970s, he returned to his home hamlet. After returning to the hamlet, he managed the orange and shiikuwasaa lime orchards. The orchards were spread in the mountainous areas around the hamlet and was 0.6 ha (2,000 tsubo). The annual harvest was approximately 10 tons.

Interestingly, in his oral memoir, Shinfuku-san says the idea to have the orange and lime orchards came to him when he worked in Naha in his fifties, namely ten years before his retirement. Then, he realized that he should plant oranges and limes first. Every weekend, he transported young trees with a motorbike from Naha to Yambaru and planted them in his family’s former paddy fields. At that time, as there was no expressway between the south and north, an entire day was necessary for him to return. When he retired, the orange and lime trees in his orchards had grown enough to produce fruit. He was always thinking of keeping his household sustainable.

One reason for Shinfuku-san to consider sustainability of his house economy was that, as he was the eldest son of his parents, he should inherit and keep their compounds there. Yahabi hamlet has a long history. The description in the Omorosaushi indicates that there was—and is still now—an office and house of noro. The Noro was the traditional female priest since ancient times. In the early modern era, they were mobilized by the Ryukyu Kingdom to organize the spiritual order of the people. A noro house in Yahabi must have given Shinfuku-san the impression that the hamlet was closely related to Okinawa’s long tradition for several hundred years. Furthermore, on the top of the mountain facing Yahabi hamlet, there is an archeological castle site (gusuku in the Ryukuan language). The site is said to be a ruin of Kunigami Castle in the 14th and 15th centuries. In the Yahabi hamlet environment, many things connect inhabitants with their deep past. Shinfuku-san is closely related to this through inheritance.

Medical anthropology has revealed that long-living people in Okinawa have a stronger will to live longer than those in other regions of Japan. Sakihara (2000) calls this the element of longevity fudo. Shinfuku-san inherited home and was respected as the family head in his hamlet. When he receives a guest, he sits in front of tokonoma alcohol as a host. In Okinawa, being older leads to respect and admiration. The stability of the hamlet and the family must lead to the stability of individual life. The feeling of a long historical tie between the surroundings must influence his sense of time and stability and lead the way to live long.

6. Sweet Potatoes and traditional food in Okinawa

Shinfuku-san’s “dish for a hundred years” was sweet potato. How does this relate to the fudo phenomenon? Fudo is a phenomenon of the perceived environment. Fudo changes if social and natural physical conditions change. The food habitus is a typical fudo phenomenon. If the geophysical conditions remain the same, the food habitus changes when social conditions and ingredients change. The transition of food followed the same pattern as the transition of fudo.

Additionally, fudo transcends the dichotomy between objectiveness and subjectiveness. Augustin Berque called this structure a trajection (Berque, 1986). Food is a trajective phenomenon; at first, it is an objective outer thing to be eaten, but after digestion, it becomes an inner thing that consists of the subject’s body.

To investigate Okinawan food as a fudo phenomenon, we first examined its characteristics. A historical study revealed the following (Nihonno shokuseikatuzenshu Okinawa henshuuiinkai, 1988: 1):

- Using vegetables, fruits, and seafood in the subtropical ocean climate and using pork meat and lard. The ingredients are often fried or stir-fried.

- Mixed cultural origin: Indigenous elements are influenced by Southeast Asians and Chinese (from the 13th century onward), mainland Japanese (from the 17th century onward), and American culture (after WWII). Ordinary people adopted court cuisines influenced by foreign couture.

- Close relationship between food, communal feast, and religious rituals.

- Differences and Diversity. On the 161 islands of Okinawa, detailed recipes vary according to agriculture, fisheries, annual religious practices, and ritual conditions.

Although the condition of terra is not perfect for agriculture—narrow land, poor soil, drought frequency, and typhoons—agriculture was the basic economy in Okinawa. Fishery was not promoted by the Ryukyu kingdom. “Three main agricultural products” were paddy rice, sugar cane, and sweet potato for a long time. From a statistical perspective, the importance of sweet potatoes is evident. The cultivated area of Okinawa in 1926 was 55,914 chou (町, 55,449 ha). The areas used for sweet potato cultivation were 28,524 chou (50%), 11,049 sugarcane (20%), and paddy rice 8,097 (14%). Other products included wheat, soybean, millet, and vegetables. (Nihonno shokuseikatuzenshu Okinawa henshuuiinkai, 1988: 308)

The dates of sweet potato imports to Okinawa are clear. It was first imported from Luzon Island, Philippines, to China in 1594 and from China to Okinawa in 1605. After its introduction, agricultural production stabilized, and the population increased; in the 15th century, before the introduction of sweet potatoes, Okinawa had 7–8,000 people, whereas in the 18th century, 200,000, and in the early 20th century, 600,000.

At the beginning of the 20th century, sweet potatoes were inseparable from the Okinawan menu. The ordinary menu consists of sweet potatoes, miso soup, stir-fried vegetables, salted sea bass, and tofu (Fig. 4). Pork, fried ingredients, fish cake, and simmered kelp were served on special occasions, such as festivals and religious days. White rice is seldom eaten except in Naha. (Nihonno shokuseikatuzenshu Okinawa henshuuiinkai, 1988: 325–332)

Although all villages have various subsistence practices and their environments and ingredients are diverse, the Okinawa people adopted sweet potatoes as the most basic staple. It was so well adopted that, although it was introduced only in the early 17th century, people in the 20th century might not have thought it was an imported ingredient. As Shinfuku-san’s narrative indicates, it is already embedded in their memory; hence, it has become a part of their identity. Elements already identified as components of one’s identity can be considered fudo. The sweet potato was already fudonized (風土化) at the beginning of the modern era in Okinawa.

7. Changing food habitus in Okinawa: Are the “real” traditional foods not attractive?

Fudo changes as the flux phenomenon of islandness changes. In this section, we investigate two examples of the changing foodscape: changing the position of sweet potatoes and the emergence of new recipes.

First, how has the status of sweet potatoes changed? In the early 20th century, sweet potatoes were identified as fudo in Okinawa. This status had disappeared when the 21st century began, and sweet potatoes rarely appeared in popular contemporary narratives on longevity in the commercialized world.

In the book Recipe from the Most Longest Life Village: Gramma’s Island Dishes (『世界一の長寿村のレシピ: おばあの村の島ごはん』), although it refers to the traditional food of Ohgimi village as the “longevity dishes,” mentions of sweet potato as staple food were not found (Popurasha henshubu, 2011). Instead, it emphasized using vegetables and “balanced” nutrition as the key recipe characteristics for long living.

The village has a restaurant that features the “traditional” dishes as the “Longevity plates (長寿膳)” (Fig. 5). The dish consists of a large plate and five small bowls. Although it contains various vegetables, fruits, and salads, what stands at the center of the plate is not a sweet potato but brown and red rice balls.

This is slightly different from “real” traditional foods. As we have seen in Fig. 4 in the previous section, the main ingredient of the traditional dishes was steamed sweet potato.

However, we cannot see it on the contemporary “longevity plate.” Instead, at the right side of the two rice balls, we can see small purple sweet potato doughnut. The reason steamed sweet potatoes are avoided in the dish is unclear, but it is easily inferred that they are not attractive to present-day consumers. In order to develop the menu, the restaurant had conducted field survey on food habitus of long-lived people in Ohigimi and knows the importance of sweet potatoes well. But to adopt it into contemporary menu as a staple ingredient is not easy for them (Kinjo, 2023: 102–105). They feature sweet potatoes not as a main ingredient but as a kind of sweets or ‘dolce’ in their “Longevity plates.” It can be said that the “longevity plate” is a “re-invention” of traditional food. Not all things in history are transmitted to the future. History is always selectively narrated. If we look back at fudo in the past, its representation may have been invented later.

Second, new recipes completely different from Okinawan tradition appeared. Okinawan food is considered healthy. Consuming vegetables, tofu, and fish has been positively evaluated for good health. Consuming pork is said to promote good health, also. However, recently, as seen in the previous section, the Americanization of food throws a shadow on the Okinawan food habitus. The decline in life expectancy in Okinawa in the late 1990s and the early 2000s is said to have been caused by this phenomenon.

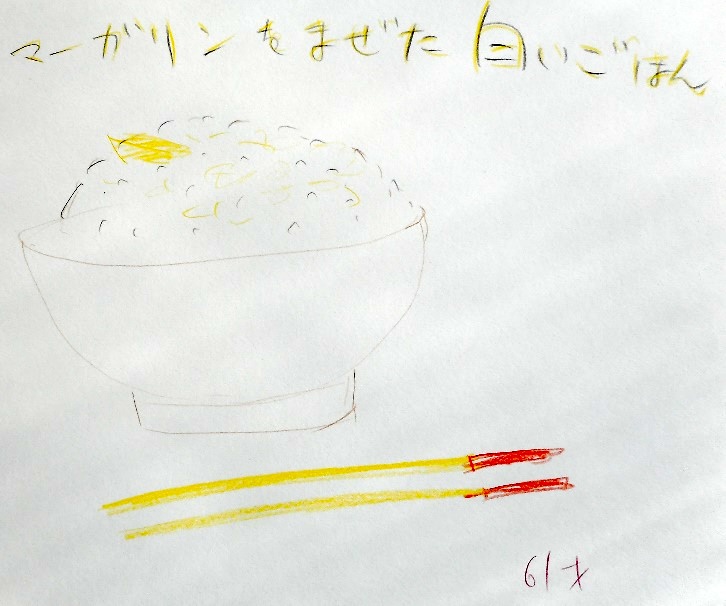

In 2019, we encountered “margarined rice (マーガリンごはん).” When we conducted a workshop in the Takazato settlement and asked residents about the most impressive food in their childhood, a man born in 1958, the man of the “daughter and son generation” to Shinfuku-san, answered that he remembered white rice dressed with margarine most impressively from his childhood. Hearing his answer, other participants at the workshop also agreed with his remark, and someone even said, “‘Margarined rice’ is not only my soul food but also Okinawan.”

Margarine is a spread material made from animal fats or vegetable oils. It was invented as a substitute for butter in the early 19th century in France and is now used worldwide. Originally and normally, it was used as a spread on bread or crackers; however, in Okinawa, it is placed on warm white rice and stirred using a chopstick (Fig. 6).

It is unclear who invented such a use of margarine and when; however, as this menu is not very often found in areas other than Okinawa in Japan, it is thought to be connected to the U.S. occupation of Okinawa from 1945 to 1972. It may be an example of the Americanization of Okinawan food habitus and Okinawanization of the Euro-American food element.

As mentioned previously, one characteristic of Okinawan food culture is pork usage. Okinawan dishes exhaustively use pig meat, blood, skin, organs, and other components, and pig usage in Okinawa is said to be influenced by China. Mainland Japan lacks such knowledge. Lard is effectively used in Okinawan cuisine. In such a background, “margarined rice” must have been invented by Okinawan people.

In the previous section, we saw sweet potatoes had already been fudonized by the early 20th century. Until the early 21st century, “margarined rice” was part of Okinawan everyday food. People in Okinawa know that lards are not good for their health; however, they still say that they love “margarined rice.” If they live a hundred years, is the margarined rice their “dish for a hundred years”?

8. Present food seen from hundred years of future

In the first section, I wrote that the “Dish for a hundred years” project aims to promote people’s recognition of sustainability regarding food habitus. Shinfuku-san’s food habitus is key to this, but although it might have brought him longevity, to have the same habitus as he is impossible for other people. We cannot and should not copy his habitus. Instead of copying his life, how can we find a way to measure plausibility towards a sustainable future?

In this vein, our project defines the term “dish for a hundred years” in a particular way. According to our definition, it refers to a dish people remember as the most impressive/favorite food when they turn a hundred years old. When such a term is used, we may expect the scientific implication that the dish is the cause of longevity, enabling an individual to live for over a hundred years. However, in this project, we avoided viewing longevity as a cause-and-effect relationship but as a consequence of chance instead. This usage can be considered a metaphor.

The human lifespan is complex and difficult to narrate under a cause-effect narrative. If told in this manner, it might oversimplify her/his life. Longevity here is, therefore, acknowledged simply as a problem of a backward narrative to avoid oversimplification.

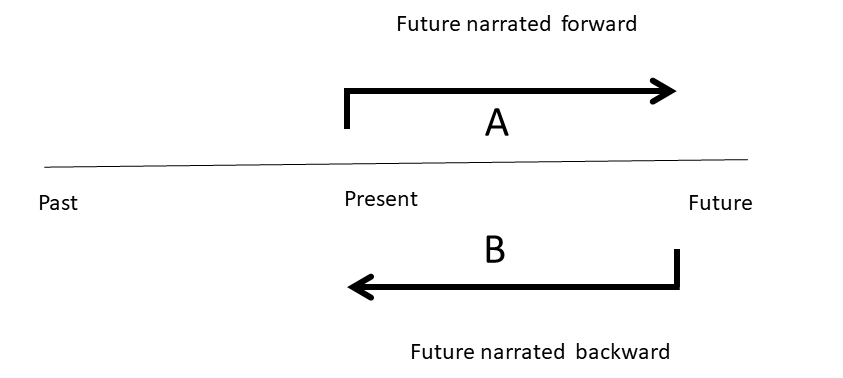

This sense comes from centenarians’ reflections and feelings. For them, their long life was merely a result, and they often narrated their lives as a matter of contingency. When we see long life in this way, we can stand in a position of our future self, which enables us to narrate our entire life in terms of “backcasting.” Normally, we narrate the future from the viewpoint of the present in a forward manner (Arrow A in Fig. 7). In contrast, in backcasting, we transfer the standpoint from the present to the future and from the transported perspective in the future, the future will be narrated. Once the viewpoint is relocated to the future, the future that exists when seen from the present becomes the present, and this change enables transferring the future to the past (arrow B in Fig. 7).

Sustainable sciences advocate the importance of standing in the future. Most notably, the Sustainable Development Goals set by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015 adopted the backcasting method (Robinson, 1990). In sustainability studies, transforming an individual’s mindset is required, and the backcasting method is considered suitable.

Examining our present food habitus from the perspective of our future self may lead us to transform our food habitus in “a future-oriented manner.” To do the same thing as Shinfuku-san is impossible, but to behave in the same way as Shinfuku-san would be possible if Shinfuku-san were in your position or if you were in Shinfuku-san’s position.

In a workshop held in Kyoto, we showed Shinfuku-san’s interview video and asked children to draw an illustration of their favorite food (Fig. 8). We told them that today’s their favorite food becomes their ‘dish for a hundred years,’ if, in the future, they are hundred years old and they remember it then. When you notice that today’s food may sustain your life after a hundred years, you must pay more attention what you eat today. Children drew their favorite food freely. Shinfuku-san’s longevity is based on his island fudo, but by putting it into the backcasting framework, its lesson becomes universalized.

Afterword

While writing this paper, Shinfuku-san passed away at the age of 108 on May 27, 2023. The funeral announcement posted to the Okinawan local newspaper by his family says that he “fulfilled his longevity of heaven’s mandate (天寿を全うした).” The author dedicates this study to his memory with sincere gratitude and respect.

Acknowledgments

The “Dish for a hundred years” project was supported by the FEAST project (Lead: Steven McGreevy) of the Research Institute for Humanity and Natura, the “Fudo”-nization of Advanced technology: How to imagine plausible future of human-computer interdependency” project (Lead: Kumazawa Terukazu) of The Toyota Foundation Research Grant, and JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (JP20H00049, Lead: Tanaka Ueru).

Disclosure and conflicts of interest

The author has no conflict of interest regarding the contents of this paper.

Endnotes

References

- Berque, A., 1986. Le Sauvage et l’artifice : Les Japonais devant la nature. Gallimard : Paris.

- Berque, A., 1988. Fudo no Nippon: Shizento bunka no tsutai (『風土の日本:自然と文化の通態』, Fudo and Japan: Trajectivity between Nature and Culture), trans. by Katsuhide Shinoda. Chikuma Shobo: Tokyo

- Buettner, D., 2008. The Blue Zones: Lessons for living longer from the people who’ve lived the longest. National Geographic: Washington D.C.

- Campo Tejedor, A. and Ruiz-Ballesteros, E., 2020. Fleeing to World’s End today (Floreana, Galápagos): Microislandness in a global changing world. J. of Marine and Island Cultures. 10(1).

- Eminomise, 2023. Website. https://eminomise.com/. Accessed on Jul 31, 2023.

- Grydehøj, A., 2018. Islands as legible geographies: perceiving the islandness of Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland). J. of Marine and Island Cultures, 7(1).

- Higuchi, J., 1987. Janagusuku 1: Sonrakushakai niokeru bunkano juuyousei nituiteno oboegaki (「謝名城1: 村落社会における文化の重要性についての覚え書き」, Janaguzuku 1: Note on importance of cultural aspect in village society),“ Shakaikagaku nenpo (『社会科学年報』, The Annual bulletin of social science). Institute for Social Science, Senshu University, 21.

- Hokama, S., Nobutsuna S., (annotation) 1972. Omorosaushi (『おもろさうし』, Collected omoro songs). Iwanamishoten: Tokyo.

- Kinjo, E, 2023. Obaa tachino daidokoro (『おばあたちの台所:やんばるでつないできた食と暮らしと言葉の記録』, Gramma’s kitchen tales: Documents of life and food in Yambaru). Gurafikkusha: Tokyo.

- Nihonno shokuseikatuzenshu Okinawa henshuuiinkai, 1988. Kikigaki Okinawano shokuji (『聞き書沖縄の食事』, Oral History of Okinawan Food Habitus), Nihonno shokuseikatu senshu (日本の食生活全集, Collected Works of Japanese Food Habitus), Vol. 47. Nousanson bunka kyoukai: Tokyo.

- Ohgimison kyouikuiinkai, 2010. Ohgimison bunkazai kisochousa oyobi rekisi bunka kihon houshin sakutei jigyou houkokusyo (『大宜味村文化財基礎調査及び歴史文化基本方針策定事業報告書』, Report on basic research of Ohgimi village’s cultural heritage and grand design for historical cultural policy). Ohgimison kyouikuiinkai: Okinawa.

- Ohgimisonshi hensan iinkai, 2016. Ohgimisonshi: Shimajima honpen (『大宜味村史: シマジマ 本編』, History of Ohgimi Village: Description of individual hamlets). Ohgimison Yakuba: Ohgimi.

- Okinawaken kyouikutyo, 2020. Okinawakenshi: Kakuron hen (『沖縄県史: 各論編』, History of Okinawa), vol. 9 Minzoku (民俗, Folklore). Okinawaken kyoiku iinkai: Naha.

- Popurasha henshubu, 2011. Sekaiichino choujumurano reshipi: obaano Murano shimagohan (『世界一の長寿村のレシピ: おばあの村の島ごはん』, Recipe from the longest life village: Gramma’s island dishes). Popurasha: Tokyo.

- Robinson, J.B., 1990. Futures under glass: A recipe for people who hate to predict. Futures. 22(8).

- Sakihara, M., 2000. Okinawano kiko fudo to tyouju (「沖縄の気候・風土と長寿」, longevity of Okinawa, environment, and fudo). Nihon junkanki kanri kenkyu kyougikai zassi (『日本循環器管理研究協議会雑誌』, J. of the Japanese Association for Cerebro-cardiovascular Disease Control). 35(1).

- Suzuki, M., 2001. Tyojutiiki Okinawa no fudo seikatsushukan(「長寿地域沖縄の風土,生活習慣」, Life style habit and fudo of Okinawa, the long-life area). Nihon rounen igakukai zasshi (『日本老年医学会雑誌』, Japanese journal of geriatrics). 38(2).

- Terada, M. 2018. 100 Years Old Shinpuku-san in His Shiikwasaa-lime Orchard. Color DVD, 5min.

- Terada, M., 2022. Kioku wo Kashikashi, kanousei wo kenzaika suru: 100sai Gohan to 3sai Gohan wo meguru eizou to insutareishon (「記憶を可視化し、可能性を顕在化する: 「100才ごはん」と「三才ごはん」をめぐる映像とインスタレーション」, Visualizing Memory: About the installation on food scape of hundred years and three years old). In Kondo, Y. and Mallee, H. (ed.), Kankyomondaiwo mieruka suru: Eizo, taiwa, kyoso (Visualizing Environmental Issue: Image, dialogue, and Co-creation). Showado: Kyoto.

- Terada, M., 2023a. Jinshinse no fudogaku: chikyu wo yomu tameno hondana (『人新世の風土学: 地球を〈読む〉ための本棚』, Fudo in the Anthropocene: Finding a new environmental mode between human beings, living things, and things). Showado: Kyoto.

- Terada, M., 2023b. On the Notion of ‘Fudo’: World making and subjecthood. Manuscript for session presentation. SRI (Sustainability Research Innovation Conference) 2023, Panama and online, Jun 29, 2023.

- Tsuha, T., et al., 1982. Okinawa kunigamino sonraku (『沖縄国頭の村落』, Villages in Kunigami, Okinawa), Vol. 1. Shinsei shuppan: Naha.

- Vitello, P., 2013. Alexander Leaf Dies at 92: Linked Diet and Health. The New York Times (Jan 6, 2013). https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/07/us/alexander-leaf-dies-at-92-linked-diet-and-health.html. (Accessed on Jul 31, 2023)

- Willcox, B.J., Willcox, C.D., Suzuki, M., 2001. The Okinawa Program: How the world’s longest-lived people achieve everlasting health, and how you can too. Three Rivers Press: New York.

- Willcox, B.J., Willcox, C.D., Suzuki, M., 2004. The Okinawa Diet Plan: Get leaner, live longer, and never feel hungry. Three Rivers Press: New York.

- Watsuji, T., 1935–1962. Fudo: Ningengaku teki kosatsu (「風土:人間学的考察」, Fudo: An anthropological reflection), in Watsuji, T. Watsuji Tetsuro Zenshu (『和辻哲郎全集』, Complete Works of Tetsuro Watsuji), Vol. 8. Iwanami shoten: Tokyo.