Creative Battle Space: The Sea in Indonesian Newspaper Short Stories

Abstract

The sea has always been a source of inspiration in literature. The sea becomes a creative battleground in literature because it depicts human life full of challenges, difficulties, hopes, and adventures. In literature, the sea becomes a metaphor that helps reveal human life's complexity by showing life's beauty and ferocity. This study aims to advance existing studies to identify unique concepts, ideologies, or discourses relating to the ocean that are hidden in 25 short stories from 2010 to 2021 in Indonesian newspapers. Using an interactive interpretation method, all short stories are analyzed through content analysis techniques to reveal the various creative battle spaces. Through a mixed methods study with a critical approach, this research found four creative battle spaces with their respective subspaces, namely: (1) economic battle space with capitalist and impact of capitalism subspace; (2) moral battle space with action crime and power struggle subspace; (3) inner battle space with serenity, sorrow relief, the battle between reality and desire, and the battle of life subspace; and (4) surrealism idea battle space with the meeting space of two worlds, the endless search, surrealism-economics, and spirituality and imagery subspace.

Keywords

sea, short story, battle space, creative, ideology

Introduction

The ocean(s) is the interconnected system of oceans (Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Southern, and Arctic) on Earth. The Earth's oceans are larger (71%, 361 million km2) than land (29%, 149 million km2). Meanwhile, as a small part of the Earth, out of a total area of approximately 7.81 million km2, Indonesia only has a land area of 2.01 million km2, the remaining 3.25 million km2 is the ocean and 2.55 million km2 of its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (Webb, 2023; Tim Redaksi, https://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laut 2023). The fact that the sea is much larger than the land convinces us that the ocean is still a mystery, and as a result, the activities that humans can do to utilize the sea are still different from the wealth contained therein. Therefore, it is natural that until now, the study, research, or exploration of the ocean has been continuously developed by experts (Orcutt et al., 2003).

It is proven that the ocean is very useful for human life, including as a provider of oxygen, a regulator of the earth's climate, an abundant source of protein, and a place of dependence for millions of living things (Mardatila, 2020; Muñoz et al., 2023). Therefore, the cleanliness of the sea must be maintained. Meanwhile, the ocean is currently filled with plastic waste. To contribute to protecting the ocean, Ita-Nagy et al. (2022) proposed a methodology to estimate plastic release into the ocean. The ocean is also a source of life for fishermen who are not only related to fishing activities but also weather forecasting and so on (Foo et al., 2022). By 2030, the ocean will employ more than 40 million people worldwide (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2016). In the semiotic reading of the anime conducted by Noviana (2020), several Japanese views of the sea are seen as a source of life, prosperity, strength or energy, trust, and beauty. However, despite its beauty, the ocean is also an arena for crimes, such as terrorism, smuggling, drug trafficking, illegal fishing, and so on (Simangunsong & Hutasoit, 2018).

It is also evident that, directly or indirectly, the ocean is beneficial for humans to build their survival and, in the context of this study, useful for authors (writers) to build their works of creation (novels, poems, short stories). Literary works can even use the sea to depict the topography and demography of a region, as Lim (2022) did. Water as an ambivalent element of the sea unites beginning and end, life and death, and becomes an organic space for the soul by looking at the relationship between soul and sea as a lyrical situation in Tyutchev's poetry of the 1850s to 1860s (Kalashnikova, 2019). Meanwhile, Joaquim Nabuco's abolitionist writings present a sea-based account of national development (Feldman, 2023). In addition, literature can be a medium for constructing interculturality and negotiating participants' identities in the setting of ocean voyages (Xu, 2023). In the context of Indonesian literature, Anas et al. (2019) concluded that many Indonesian authors, especially novelists, show human biophilia's love for the marine environment. For example, sea life is used by Motinggo Busje in Penerosan di Bawah Laut (1964), Aspar in Pulau (1976), and Pramoedia Ananta Toer in Gadis Pantai (1987). The same thing also happens in the context of Indonesian poetry—the poets who are very keen on exploring the sea include D. Zawawi Imron, as shown in the book Madura Akulah Lautmu (1978), Bantalku Ombak Selimutku Angin (1996), and Lautmu Tak Habis Gelombang (1996). Meanwhile, in the context of Indonesian, many short stories raise the issue of the sea in their works, both works that have been booked and work that are still scattered in various print and electronic mass media.

The sea, as an essential part of literature (fiction), has been studied by many scholars in Indonesia and the West. In the West, for example, Samuelson (2010) studied the sea in the fictional works of South African author Zoe Wicomb. He argues that in Wicomb's works, the sea is a battleground of meanings and an ‘archive’ that challenges South Africa's national history. In contrast to Samuelson, Staley (2016) studied medieval texts in England with a focus on the sea as a creative battleground to trace the power of ideology in the world of sea trade. Meanwhile, in Indonesia, literary studies related to the existence of the sea have also been carried out, including by Zakaria (2010), Kharisma (2019), and Noviatussa’diyah, Sugiarti, and Andalas (2021). Zakaria (2010) studied the humanities side of the novel Gypsy Laut by Rahmat Ali and its utilization as an alternative learning material for literature appreciation in high school; Kharisma (2019) studied environmental character values in the novel Mata dan Manusia Laut by Okky Madasari; and Noviatussa’diyah, Sugiarti, and Andalas (2021) studied the cultural ecology of the Bajau Tribe in the novel Mata dan Manusia Laut by Okky Madasari. In the study, Anas et al.(2019) revealed that Indonesian literature, especially novels, show human love for the marine environment.

As an enrichment of existing studies, this study examines the sea as a space for creative battle in several Indonesian newspaper short stories over the past decade (2010—2021).1 The core question is how the author plays his creative imagination when looking at the sea-which in Eco's concept (1976) is called a typical code, coded text 'text that can already be read', or coded messages 'messages that have been coded'—and then present these codes in his creation so that it allows aesthetic communication (Segers, 2000) between the text and the reader (Sayuti, 1997). The question—in the system of literary signification and communication—is based on the concept that the coded text (sea) is what, on the one hand, triggers the practical actions of the author in representing ‘certain ideas, ideologies, or discourses’ in the text and on the other hand triggers the practical actions of the reader in the process of interpretation.

Methods

This mixed methods study uses a critical approach (White & Cooper, 2022); an approach characterized by the search for meaning, understanding, and the locus of meaning found, among others, in narrative texts. Therefore, the study data refers to verbal information (signs or codes of words, sentences, expressions) from reading the text according to communication semiotics. The results are descriptive verbal (Yin, 2015). Data was collected from short stories published in the last decade (2010–2021) and published in the Indonesian Newspaper Literature Documentation Center (Redaksi-ruangsastra, 2023). The ruangsastra.com blog, which has been published since 2021, is a substitute for the lakonhidup.com blog, which has been published since 2010. That is why the data in this research were chosen from 2010 to 2021. The last decade was chosen because, among other things, even though National Maritime Day had been coined in 1964, Indonesia's desire to become the world's maritime axis was only driven in this decade, as stated by the 7th President of the Republic of Indonesia in his speech at the East Asia Summit on July 22, 2014 (Humas-Setkab, 2014). Meanwhile, preliminary readings show that in this decade (2010–2021), there are 40 short stories related to the sea. However, not all of these short stories represent the sea as an arena for ideological battles; the sea is only expressed in passing and does not affect the characters leading to the development of the theme. Therefore, objectively, following the objectives of this study, twenty five short stories were determined as a source of data and material for analysis. Twenty-five ocean-related short stories were purposively selected and analyzed using the interactive-interpretation method through content analysis techniques. The content analysis technique aims to reveal the content of messages in a text or document by identifying, classifying, and calculating the frequency of occurrence of specific categories contextually (Krippendorff, 2018).

In critical analysis, frequency counts are not a priority. However, the high frequency of occurrence of texts and contexts contained in short stories can strengthen the meaning construction built by the author to convey certain ideologies. In this case, the text is defined as written communicative material that people can read, understand and comprehend (Krippendorff, 2018). Through these quantitative and qualitative approaches, a comprehensive understanding of the function and meaning of the sea as the creative battle space in short stories will be obtained.

With this technique, the following steps were taken in the study of the ocean as a creative battle space in several Indonesian short stories: (1) selecting and presenting data that represent the ocean; (2) identifying how the text expresses the ocean; (3) calculating the frequency of occurrence of each category; (4) interpreting the expression of the ocean that functions as a space for the battle of ideas; and (5) interpreting various ideas/ideologies that allow readers to infer the meaning of the text. These steps have a pattern of interaction and chronology bound by three keywords: identification, selection-interpretation, and organization (Maykut & Morehouse, 1994).

Twenty-five ocean-related short stories were purposively selected and analyzed using the interactive-interpretation method through content analysis techniques. The content analysis technique aims to reveal the content of messages in a text or document by identifying, classifying, and calculating the frequency of occurrence of specific categories contextually (Krippendorff, 2018).

Results and Discussion

Indonesian Newspaper Short Stories 2010—2021

The sea as a creative battleground has been a theme of interest to literary writers for centuries. The beauty of the sea invites a variety of interpretations for the viewer. As a vast element of nature, it provides various opportunities for writers to create engaging stories.

In literature, the sea is often portrayed as a dangerous and mysterious place full of wonders and surprises. Many authors use these characteristics of the sea as a backdrop to develop dramatic and riveting plots. The sea is often used as a metaphor for the challenges and dangers of human life. Authors use the ocean's unpredictability and stunning beauty to portray the human struggle to overcome obstacles and challenges in life. Authors often explore themes such as the beauty and majesty of the sea, the lives of fishermen, encounters between humans and sea creatures, and stories of s and sailing. In some works, short stories about the sea in Indonesia raise various environmental and sustainability issues. Some authors even highlight the adverse effects of human activities on the sea, such as pollution, damage to coral reefs, and overfishing. The sea is also often portrayed as a creative battleground for authors in literature. Works such as Herman Melville's Moby Dick and Ernest Hemingway's The Old Man and The Sea are prominent examples of the ocean as an attractive creative battle space.

In this study, the research team generally found four creative battle spaces in the twenty-five short stories analyzed. The four spaces of struggle are economy, morality, inner mind, and surrealistic ideas. The following is a description of 25 Indonesian newspaper short stories from 2010 to 2021 that revolve around the sea as a creative battle space created by the author.

| No | Title | Author | Publication | Battle Space |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nelayan Itu Masih Melaut | Muhammad Khambali | Media Indonesia, 22 November 2020 | Economy |

| 2 | Ikan Terbang Kufah | Triyanto Triwikromo | Kompas, 7 November 2010 | Economy |

| 3 | Nelayan dari Pulau Rote Ndao | Fanny J. Poyk | Jawa Pos, 11 February 2021 | Economy |

| 4 | La Asidi Anak Laut | Dul Abdul Rahman | Rakyat Sultra, 11 November 2019 | Economy |

| 5 | Pedang Hijau dari Laut | Kiki Sulistyo | Suara Merdeka, 5 May 2019 | Ekonomi |

| 6 | Pengelana Laut | Linda Christanty | Kompas, 5 January 2020 | Morality |

| 7 | Dari Laut | Dadang Ari Murtono | Kedaulatan Raykat, 15 January 2021 | Morality |

| 8 | Belukar Pantai Sanur | Gde Aryantha Soethama | Kompas, 15 November 2020 | Morality |

| 9 | Pelepah Ikan | Ragdi F Daye. | Koran Tempo, 26 December 2020 | Morality |

| 10 | Tak Sampai Bersampan ke Kampung Kusta | Marhalim ZainI | Jawa Pos, 19 December 2010 | Inner Mind |

| 11 | Ikan-Ikan Tak Lagi Datang ke Rumahmu | Farisal Sikumbang | Republika, 20 December 2020 | Inner Mind |

| 12 | Rumah Bawah Laut | Moh. Rofqil Bazikh | Fajar Makassar, 2 May 2021 | Inner Mind |

| 13 | Menjahit Gelombang | Mezra E Pellondou | Kompas, 22 November 2015 | Inner Mind |

| 14 | Tentang Kita dan Laut | Yetty A. KA | Kompas, 18 August 2019 | Inner Mind |

| 15 | Laut Tak Meminjam, Ia Mencuri | Sasti Gotama | Koran Tempo, 3 October 2020 | Inner Mind |

| 16 | Mengantar Ibu ke Laut | Hendy Pratama | Padang Ekspres, 22 December 2019 | Inner Mind |

| 17 | Balada Si Pelaut | Ilyas Ibrahim Husain | Fajar Makassar, 9 June 2019 | Inner Mind |

| 18 | Ziarah Laut Selatan | Risda Nur Widia | Suara Merdeka, 12 May 2019 | Surrealistic Idea |

| 19 | Perahu Penjemput Arwah | Risda Nur Widia | Kompas, 10 January 2021 | Surrealistic Idea |

| 20 | Kebun Binatang di Dasar Laut | Lamia Putri Damayanti | Koran Tempo, 1 December 2018 | Surrealistic Idea |

| 21 | Jiwa-Jiwa Laut | Livia Hilda | Bali Post, 18 March 2018 | Surrealistic Idea |

| 22 | Dalam Lingkaran Laut | Jemmy Piran | Jawa Pos, 3 September 2017 | Surrealistic Idea |

| 23 | Di Langit, Ayub Melaut | Aveus Har | Koran Tempo, 8 April 2017 | Surrealistic Idea |

| 24 | Bau Laut | Ratih Kumala | Media Indonesia, 9 February 2014 | Surrealistic Idea |

| 25 | Tepi Laut Kadra | Edy Purnomo | Suara Merdeka, 11 April 2021 | Surrealistic Idea |

The battle space in the 25 Indonesian newspaper short stories shows that 5 short stories are in the economic domain, 4 short stories are in the moral domain, 8 short stories are in the inner domain, and 8 short stories are in the domain of surrealistic ideas. It means that the creative battle space created by the short story authors is 20% for the economic realm, 16% for the moral realm, 32% for the inner realm, and 32% for the realm of surrealistic ideas.

In this case, the sea used in the short stories as a space for economic struggle includes the fight between poverty and hope, business battles, and also the fight for survival; the sea used in the short stories as a space for moral fighting includes a space where crime, carelessness, and power struggles occur; the sea used in the short stories as a space for inner work consists of a stretch for relieving sadness, bringing peace, solace, erasing revenge, fighting between reality (helplessness) and desire (to rebel), as well as fighting in choosing a life path, soul mate, and so on; and the sea used in the short stories as a space for fighting surrealist ideas includes a space for connecting the world of life and death, a space for the movement of dead souls, a space for playing with imagination in the myth of the seabed waiter, and a battle arena between human power and God.

Creative Battle Space

The sea is often used in literature as a creative battleground because of its complex nature and potential for conflict. The sea is even used in literature as a metaphor or symbol to symbolize the power and challenges of life. In many literary works, the sea is depicted as a place full of life and unpredictable energy, but it can also be a source of danger and uncontrollable difficulties. In the context of creative struggle, the sea can also be used as a symbol to reflect an unlimited creative state. However, creative combat as a configuration of space and time represented in language and discourse, which facilitates reflexivity and subversiveness, seen by Bakhtin as the defining achievement of modern discourse, is self-limiting and morally ambiguous in its characteristics (Parslow, 2020).

Literature can provide space for various desires, even if they are unreasonable (Britland, 2022). Literature has given space both historical space (Grabarczyk, 2021), political space as well as literary poetic space (Sudibyo et al., 2021), advertising space (Klymentova, 2022), and others. Authors even use literature as their own battle space. Like Roy (2020) has opened a new view of the study of women poets and writers by fighting for literary space for themselves in literary discourse. Literary works where creative expression is poured into a discursive contestation become fields that activate the arena of cultural production (Alario Trigueros, 2019; Yékú, 2020).

An intensive reading of the texts shows that Indonesian newspaper short stories of the last decade (2010—2021) that represent the sea do not merely express the sea as a setting in a narrow context, namely place, but as something broader and more abstract, namely space. Therefore, in these short stories, the narrator (storyteller, characters) or implied author—as conceptualized by Chatman (1980) in the narrative communication situation diagram—generally enters into and confronts a space or atmosphere without barriers. However—because of being in an abstract and barrierless area—thoughts, ideas, ideologies, and actions become free, spread, fight, and intertwine. Meanwhile, the representation of the sea used by the author as a space for expressing these ideas is generally articulated or verbalized from various actual events that are still often reported in newspapers. This kind of thing becomes necessary because that is the nature of newspaper literature (short stories).

In this study, the creative battle spaces found in the twenty-five short stories of Indonesian newspapers are economical, moral, inner mind, and surrealistic ideas battle spaces. Each space is divided into several subspaces, namely: (1) the subspace of capitalism and the impact of capitalism in the economic battle space; (2) the subspace of crime and power struggle in the moral battle space; (3) the subspace of tranquility, solace, the battle between reality and desire, and the battle of life in the inner battle space; and (4) the subspace of the meeting of two worlds, endless search, surrealism-economy, and spirituality and imagery subspace in surrealism idea battle space.

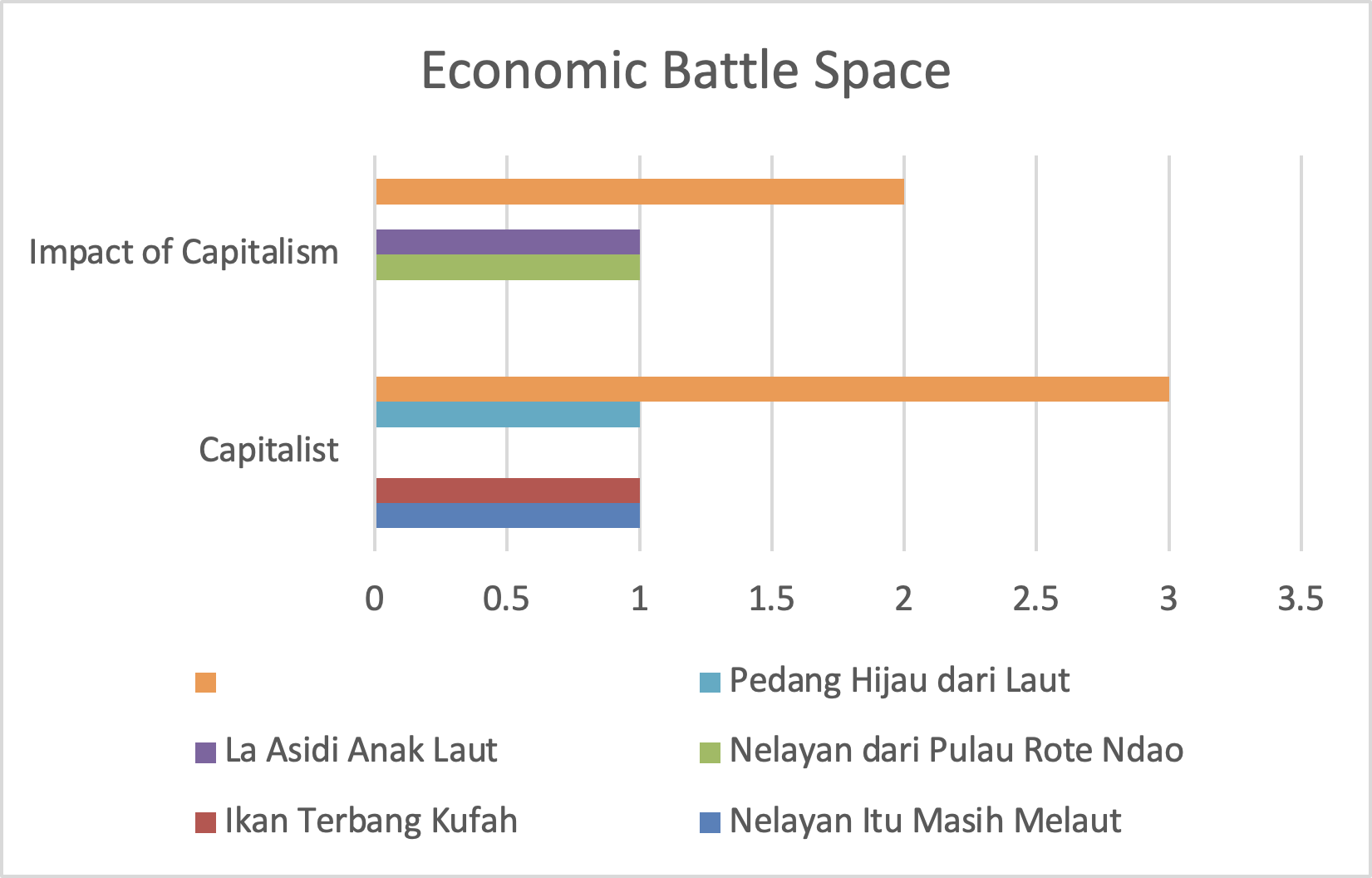

Economic Battle Space

In the economic battle space, there are two subspaces, namely capitalist (60%) and impact of capitalism (40%). The map of short stories in the economic battle space is shown in the following figure.

The discourse that is still developing and continues to be reported today about how capitalism fights (economically) with communalism and leads to the suffering of the people, for example, is nicely raised by Triyanto Triwikromo in ‘Ikan Terbang Kufah’ (Kompas, November 7, 2010). The fight takes place when city people (capitalists) intend to build a resort (hotels and restaurants) on the seafront, on a cape (land jutting into the sea). Although the author (real author) certainly has a particular choice, articulately, this short story does not show its partiality to one thing. The impartiality can be seen in the way his creative expression mixes economic struggles with various discourses about communist remnants (Kiai Siti, a descendant of Seh Muso), the role of kiai (Abu Jenar), and supernatural events (flying fish) in a spatial bond (sea, beach, cape) that does not recognize the distance between fact and fiction. Abu Jenar becomes a spy for the capitalists when they want to build a resort. He bombed the ‘village full of flying fish’. For this reason, although the short story raises questions about the truth of Abu Jenar's story, the implicit reader does not get an answer because the answer lies in the mind of the real reader. From the battle with various discourses in a vast space, the sea does not just appear as a place where events occur; more than that, it seems an arena for parodic criticism.

Although the context differs, something similar can be seen in the short story ‘Pedang Hijau dari Laut’ (Kiki Sulistyo, Suara Merdeka, May 5, 2019). However, if it is a third party, a kiai (Abu Jenar), who plays the role of a capitalist accomplice when he wants to build a resort in a seaside village in the short story ‘Ikan Terbang Kufah (The Flying Fish of Kufa)’, while the one who plays the role of a capitalist accomplice in the short story ‘Pedang Hijau dari Laut (Green Sword from the Sea)’ is a representative of the first party, namely ‘I’ (the narrator) who is assigned by the company where ‘I’ work to infiltrate the coastal area where the ‘big project’ will be built. In addition, the sea as a space for capitalist economic struggle combined with various supernatural events is also made in both short stories. In ‘Ikan Terbang Kufah’, the supernatural (magical) event is ‘a village filled with flying fish’. In contrast, ‘Pedang Hijau dari Laut’ takes the form of a horse-drawn carriage from the sea driven by a large man dressed in green and takes me to the sea from the ‘victory party’ arena on the seafront. As in the short story ‘Ikan Terbang Kufah’, and in ‘Pedang Hijau dari Laut’, the sea is not only used as a place to build events (stories) but also as an arena for criticism, namely comical criticism.

The short story ‘Nelayan dari Pulau Rote Ndao (Fisherman from Rote Ndao Island)’ (Fanny J. Poyk, Jawa Pos, February 11, 2021) also shows the same tendency as the two short stories above. The capitalist (economic) battle in the short story appears when the ruler (mafia) of the sea trade route tricked David (son of Opa John Taka), a small fisherman from Rote Island. David had not returned home from fishing for a year. In the end, he returned home lifeless. Jefry Koek, the ruler of the trade route, reported that Australian police killed David because he was accused of fishing and selling methamphetamine (drugs) in Australia's economic zone. Opa (David's parents) didn't believe it because David was just a tiny fisherman, had a small boat, fished only for food, never made it to Australian territory, and his family was not wealthy. Therefore, despite his disbelief, Opa did not dare to investigate his son's death further because he would face more extensive problems if he did. As a result, Opa's questioning is a question of the heart. This questioning of nature leads the reader to conclude that it was all due to the evil rulers of the sea trade area. It shows that the short story does not merely place the sea as a source of livelihood but also as an arena for the economic struggle that always makes the small people the victims. Like the short stories ‘Ikan Terbang Kufah’ and ‘Pedang Hijau dari Laut’, ‘Nelayan dari Pulau Rote Ndao’ is also understood as a short story that criticizes capitalist behavior.

Capitalist behavior that affects the helplessness of the little people is quite a lot of work in newspaper short stories that make the sea a creative battle space. For example, in the short story ‘Nelayan Itu Masih Melaut (The Fisherman is Still at Sea)’ (Muhammad Khambali, Media Indonesia, November 22, 2020). In this short story, the battle appears when the character Aru Labok is forced to go to sea with Dullah, a poor but diligent fisherman. Circumstances cause Aru Labok's compulsion to go to sea. People on land have been hit by poverty and crime due to the arrival of foreigners (capitalists) who opened nutmeg and clove plantations. By going to sea, Aru Labok hoped to ‘pluck stars above the vast sea’ because, according to Dullah's story, stars are a source of light and the vast sea is a ray of hope. Therefore, he insisted on going to sea with Dullah even though his father strictly forbade it.

Although the context differs, the same battle-about economic impact appears in the short story ‘La Asidi Anak Laut’ (Dul Abdul Rahman, Rakyat Sultra, November 11, 2019). Abdul Rahman tells us that the battle is between the two choices of a fisherman's son, namely ‘to continue working to help his father with the consequences of remaining poor’ or ‘to study at school to achieve success in the future’.

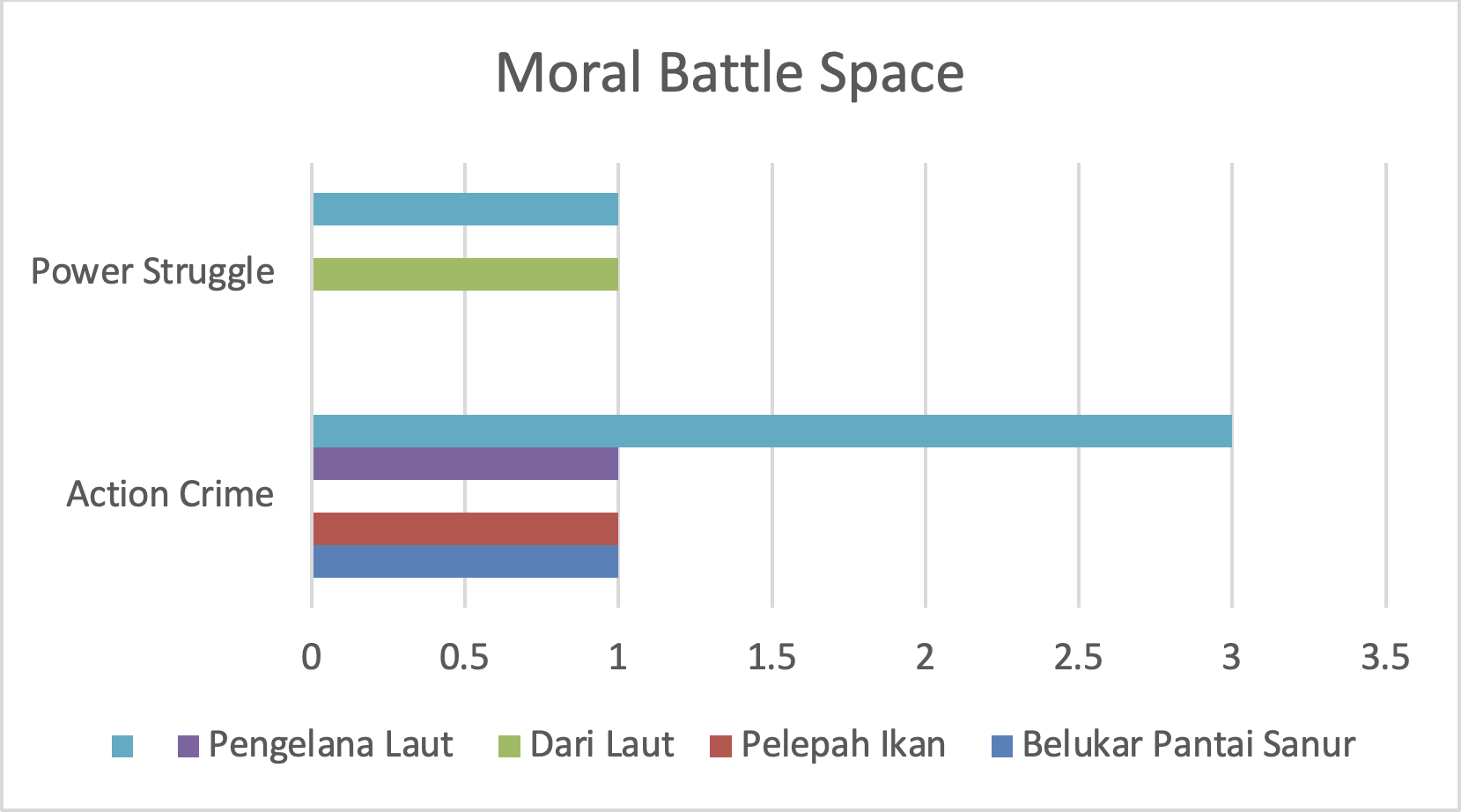

Moral Battle Space

In the moral battle space, there are two subspaces, namely action crime (75%) and power struggle (25%). The map of short stories in the moral battle space is shown in the following figure.

Various crimes that are triggered by multiple problems, such as the economy, and cause many victims can be seen in the short story ‘Pengelana Laut’ (Linda Christanty, Kompas, January 5, 2020). ‘Pengelana Laut’ depicts the sea as a space full of crimes. The sea traveller searches for his missing father by using the sea as his arena because his father was a dolphin keeper. The mysterious disappearance of his father is associated with the emergence of the criminal acts of the dolphin-hunting mafia at sea.

In the short story ‘Belukar Pantai Sanur’ (Gde Aryantha Soethama, Kompas, November 15, 2020), the sea is used as an arena for buying and selling drugs. The short story shows a battle between two pecalang, a traditional guard, and a careless policeman. Meanwhile, in the short story ‘Pelepah Ikan’ (Ragdi F. Daye, Koran Tempo, December 26, 2020), the sea becomes a space for a moral battle between a man (the son of a religious leader called ‘kiaiI’) and a woman who sells fish named Padi Boneh. Padi Boneh, a woman with two children who steals and sells fish at Gauh Market (Padang), is attracted to a man who buys fish. The man could pay any amount for anything he wanted. He did not want to be a kiai, eventually seduced and fucked Padi Boneh.

In the last decade, short fiction in Indonesian newspapers that depict the ocean has not only shown the sea as a site for capitalist ideology fights (business) but also for political ideological struggles (power). However, there are not many short stories with this characterization, which can only be seen in the short story ‘Dari Laut’ (Dadang Ari Murtono, Kedaulatan Rakyat, January 15, 2021). This short story is about the power struggle at the Palembang Palace after Sultan Datuk Iskandar died. It is told that Sutan Sahari suddenly saw Jangkung at sea, able to sail with only two coconuts from the edge of the sea, so he was considered a god or a magic wizard. Therefore, Sutan Sahari then asked Jangkung for help to free Prince Alamsyah (son of Sultan Datuk Iskandar), who, after returning from Mataram, was imprisoned at that time by Prince Sanggar Singgih. Why did Sanggar Singgih imprison Alamsyah? The reason was that Sanggar Singgih, who had married Dewi Malang Rani (the widow of Sultan Datuk Iskandar), could not seize the throne/power (Palembang Palace). However, despite being promised marriage to his daughter, Jangkung was still unwilling to help Sutan Sahari. It happened because when praying for help, Sutan Sahari's prayer contained words that seemed to threaten (and doubt the existence of) God. Therefore, even though he claimed to be able to draw water in a basket, make a pond in a jug, and turn leaves into money, Jangkung simply left.

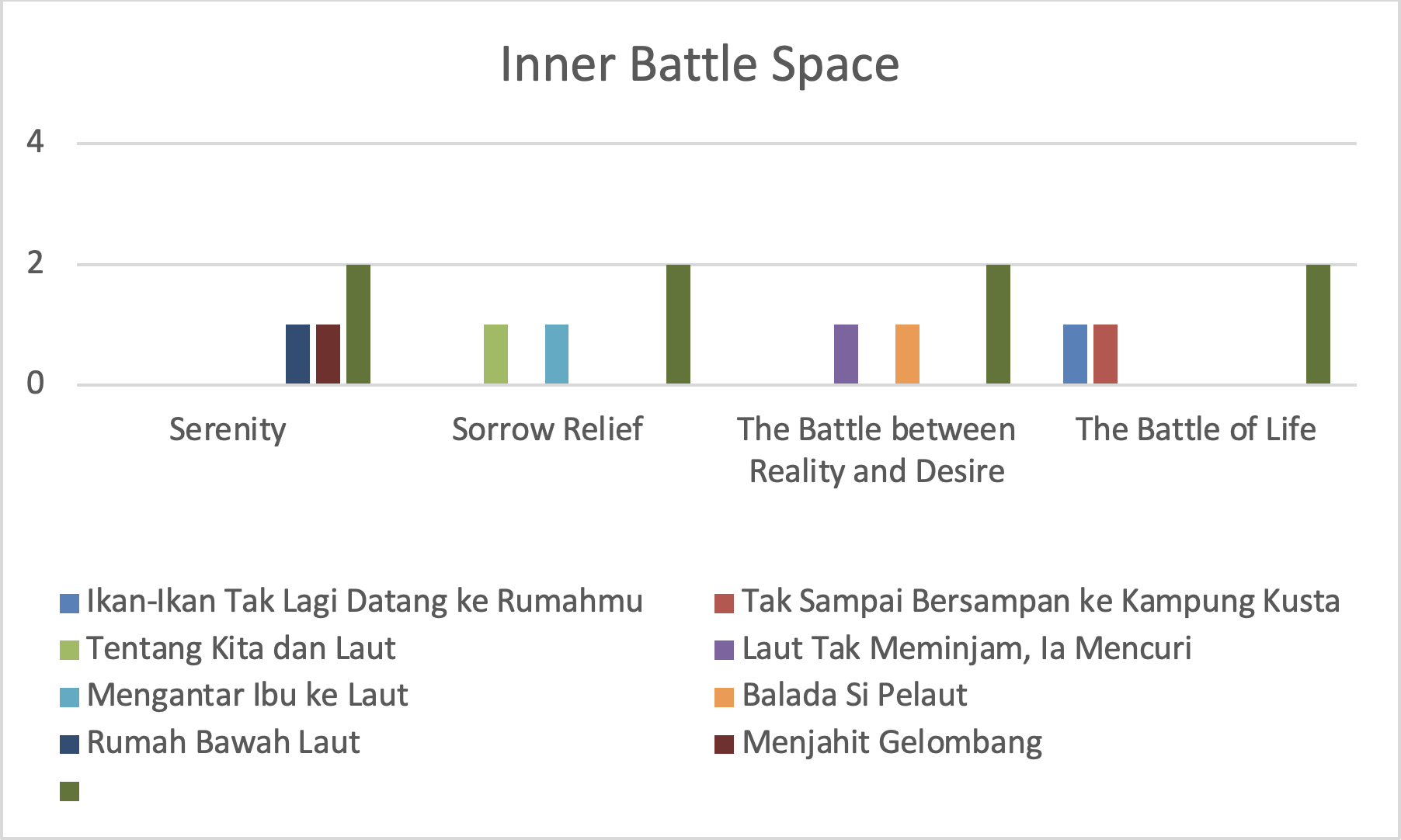

Inner Battle Space

In the inner battle space, there are four subspaces, namely serenity (25%), sorrow relief (25%), the battle between reality and desire (25%), and the battle of life (25%). The map of short stories in the inner battle space is shown in the following figure.

The sea as a space for the inner battle is seen in the short story ‘Ikan-Ikan Tak Lagi Datang ke Rumahmu’ (Farisal Sikumbang, Republika, December 20, 2020). Faisal Sikumbang shows that the fight occurs due to mutual mockery between the merchant profession and the fisherman (sailor) profession. Limah feels proud when her husband is still healthy and makes her happy from the sea. She always bragged about her sailor husband and belittled her son-in-law's job as a merchant. However, she was sad when her husband fell ill and died from working too hard at sea.

Meanwhile, in the short story ‘Rumah Bawah Laut (House Under the Sea)’ (Moh. Rofqil Bazikh, Fajar Makassar, May 2, 2021), the victim is the sea itself due to the crimes of land people who pollute and do not care about the ships of other countries that steal fish in the sea. It tells the story of me, who lives in the wreck of the titanic vessel. The character ‘I’ (along with 52 of his friends) breached the ship until it sank. All his friends could go home, but the character ‘I’ dived to the bottom of the sea. He could understand the language of the fish and made peace with them. The fish tell him that people do not care about the sea and that other countries' ships steal fish. The author's imagination runs wild in this short story. He shows the sea as a symbol of a calmer life than on land.

Short stories representing the sea as a space for women's inner (psychological) battles have also become a severe concern for Indonesian short story writers. This can be seen in the short story ‘Tentang Kita dan Laut (About Us and the Sea)’ (Yetty A. KA., Kompas, August 18, 2019). This short story is about the character ‘I’, who is sick and hospitalized due to seeing her mother's sadness every day because the child she loves so much (M=Mars) has been imperfect (idiot?) since birth. The mother is sorrowful, so she often goes to the sea. Even though ‘I’ hated mom for paying more attention to M than her, somehow, ‘I’ was happy to see mom happy. The author describes the sea as a space to release sadness and gloom.

“... Dan aku tertawa saat melihat kau menjadi ikan. Ekormu, astaga, ekormu yang indah itu meliuk-liuk saat kau melompat dan menari. Aku berani bersumpah kau belum pernah secantik ini sepanjang hidupmu. Untuk itu, kali ini aku tak akan membiarkanmu kembali menjadi perempuan berwajah muram—yang dinginnya minta ampun dan menyakitkan. Aku ingin kau tetap menjadi ikan dan berbahagia selamanya, yang hatinya paling hangat, yang tawanya bermekaran.”

"… And I laughed when I saw you become that fish. Your tail, oh my, that beautiful tail of yours twists and turns as you jump and dance. I swear you've never been so beautiful in your entire life. For that reason, this time, I won't let you go back to being a grim-faced woman--whose coldness is unforgiving and painful. I want you to stay a fish and be happy forever, whose heart is warmest, whose laughter blossoms." (Yetty A. KA., Kompas, 18 August 2019)

The same can be seen in the short story ‘Mengantar Ibu ke Laut (Taking Mother to the Sea)’ (Hendy Pratama, Padang Ekspres, December 22, 2019). The story is told that every time the sun sets, my mother goes to the sea. I (the narrator) took my mother to the sea for the umpteenth time, but then she disappeared somewhere. I regretted having taken my mother to the sea. I also wonder if she was looking for my father (a fisherman), who had been missing at sea for a long time. All I know is that my mother once told me the following.

“... Ibu percaya bahwa laut dapat menenangkan pikiran. Bahkan, bila boleh, ibu ingin hati ini dapat selapang lautan. Supaya penderitaan tidak terasa kian dalam. Kamu pernah disakiti? Nah, kamu juga boleh menjadi lautan.”

“... I believe that the sea can calm the mind. In fact, if I could, I would like my heart to be as wide as the ocean. So that the suffering does not feel deeper. Have you ever been hurt? Well, you too can be the ocean.”

It is evident that the two short stories show the sea not only as the endpoint of a search but also as a space for a woman's (a mother's) inner conflict while confronting the fact that being on the land is no happier than being at sea. Consequently, she desires to ‘merge’ with the sea.

Unlike the two short stories above, the inner battle of women in the short stories ‘Balada Si Pelaut’ (Ilyas Ibrahim Husain, Fajar, June 9, 2019) and ‘Laut Tak Meminjam, Ia Mencuri (The Sea Does Not Borrow, It Steals)’ (Sasti Gotama, Koran Tempo, October 3, 2020) does not happen to a mother, but to a wife. In Ilyas Ibrahim Husain's short story, an inner battle occurs when Soraya cannot meet Agus, her husband, the ship's captain, for five Eid. To cure her longing, they can only meet through video calls. Meanwhile, in Sasti Gotama's short story, the inner battle occurs when I (the wife) is very forced to let my clothes, dresses, and even husband be ‘borrowed’ and then ‘stolen’ by the maid. The character ‘I’ had to be willing; otherwise, all the needs would not be met. But no matter what, the inner voice couldn't compromise. So in the end, with only the husband's white T-shirt-which had not been stolen by the maid, ‘I’ danced in the sea. ‘I’ felt that she was not only ‘borrowed’ but also ‘stolen’ by the sea, just as her husband was borrowed and stolen by the maid.

This is not the case with the short story ‘Menjahit Gelombang’ (Mezra E. Pellondou, Kompas, November 22, 2015). This short story does not make the sea a space for the battle of two worlds (life and death) but as a space for the struggle of love between me (the narrator) and a man (a childhood friend) on a boat on Rote Island, as well as a space for the elimination of a sense of revenge due to the feud between their parents. The author creatively ends the conflict with a kiss.

Another story, ‘Tak Sampai Bersampan ke Kampung Kusta’ (Marhalim Zaini, Jawa Pos, December 19, 2010), tells that the sea is an arena of exile for lepers. People who survive in the exile arena end up dying. Kongkam, a character who still survives, chooses to leave the exile island. He fears facing death, which always looms large in his mind. All this time, he seemed to be so familiar with the door of dying that there was not the slightest fear in him. However, that fear has even overpowered his love for the lover he left behind on the island of exile.

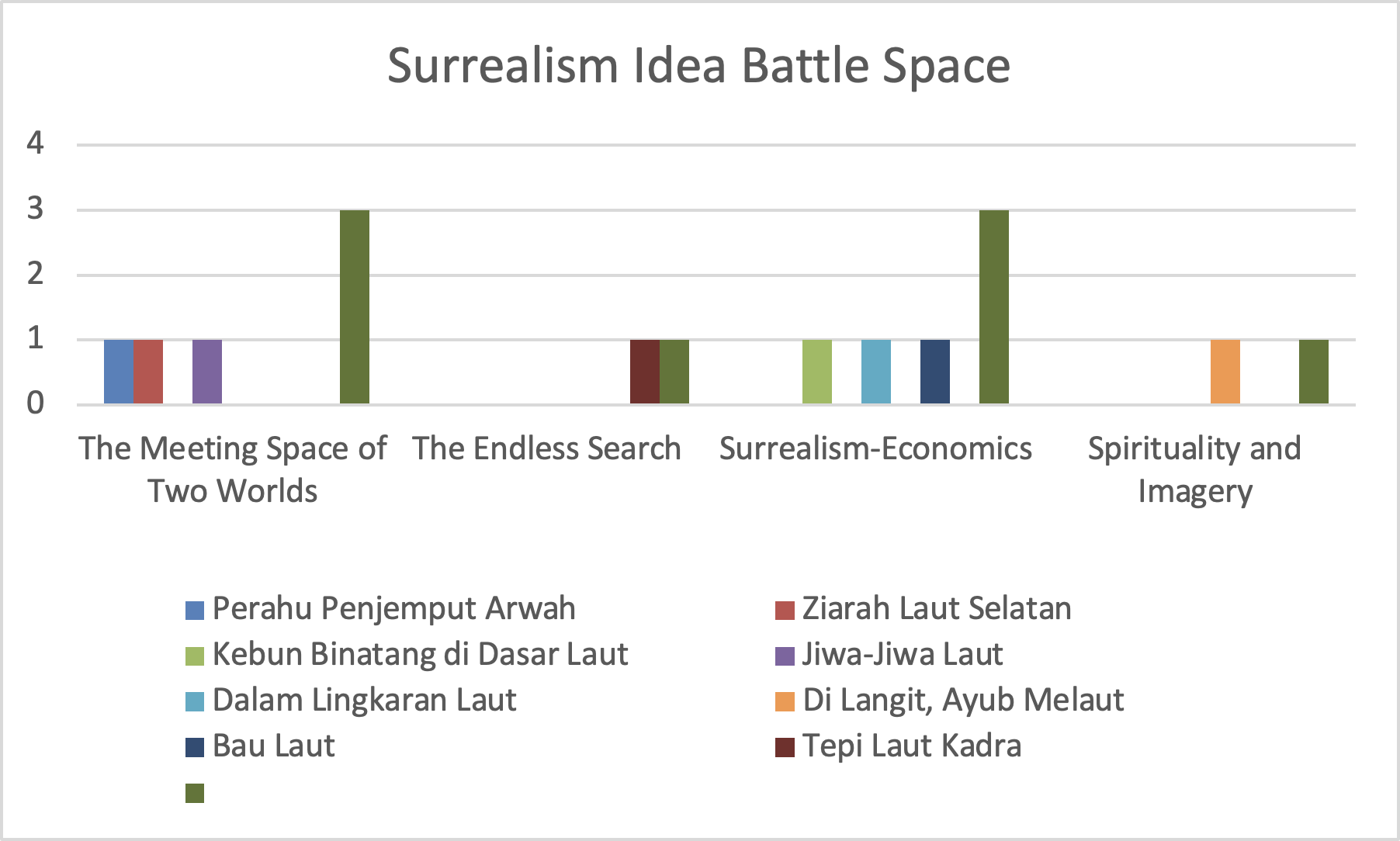

Surrealism Idea Battle Space

There are four subspaces in the battle space of surrealism ideas, namely the meeting of two worlds (38%), the endless search (13%), surrealism-economy (38%), and spirituality and imagery (13%). The map of short stories in the surrealism idea battle space is shown in the following figure.

In the short story ‘Nelayan Itu Masih Melaut’, the victims of crime are not sea people (fishermen) but land people (such as Aru Labok, who ‘hates’ sea work) who are forced to ‘go’ to the sea due to economic struggles on land. It is different from the case in the short story ‘Kebun Binatang di Dasar Laut (Zoo at the Bottom of the Sea)’ (Lamia Putri Damayanti, Koran Tempo, December 1, 2018). In this short story, the victims are the people (children) of the land who are forced to go to the sea due to economic struggles at sea; they are forced (kidnapped) to work. If they are unwilling, they are killed on large fishing vessels owned by capitalists. This event is particularly impressive and satirical (symbolic) because the discourse of capitalist evil is contrasted with the peaceful speech of a surrealistically represented ‘beautiful garden’, the ‘zoo at the bottom of the sea’. Although there have been many murders on the ship and the bodies thrown into the sea, including his own, the event is not considered important. Instead, he is happy and grateful to Koala, an animal he has long wanted to see at the ‘zoo at the bottom of the sea’. Koala's help makes him happy because he can meet friends who have been killed before.

In the short story ‘Dalam Lingkaran Laut (In the Circle of the Sea)’ (Jemmy Piran, Jawa Pos, September 3, 2017), the sea is depicted as a space for imagination about human conspiracies and the myth of the seabed. The author shows it by linking myth, ignorance, and the economy. In this case, the victim is Koli, a fisherman who is simple, without knowledge, and gets a lot of fish when he goes to sea. He is accused of having ‘married’ harin botan (a sea guardian creature in the form of a beautiful woman). In the short story, a battle occurs among the community (fishermen) due to poverty and ignorance; ignorance is seen in the ease with which people (the community) believe in mystical things.

Just as in the short story ‘Dalam Lingkaran Laut’, in the short story ‘Bau Laut’ (Ratih Kumala, Media Indonesia, February 9, 2014), the author, through the narrator, tries to contrast the impact of economic crime with a surreal event (discourse), namely humans (characters) who can live in the depths of the sea as well as on land. In the short story, the impact of economic crime is contested with mythological events (discourse). It can be seen through the fishing community's belief that the character Mencar is ‘married’ to the Mermaid, so he is considered a ‘shaman’ who knows exactly where the fish can be caught.

If the short story ‘Dari Laut’ presents a space for power (political) battles, this is not the case with the short story ‘Di Langit, Ayup Melaut’ (Aveus Har, Koran Tempo, April 8, 2017). This short story shows the sea as a space for spiritual, religious, and magical battles. It is said that Ayup, when paddling his canoe to the sea, feels that the seawater rises and continues to rise to the mega-mega, even to the moon. As usual, he cast his net and caught a lot of fish. Feeling that he had enough, Ayup paddled the canoe, got off, and returned to his hut, and as usual, he taught the children the Koran in his house. One day, he went to sea again, climbed to the mega-mega, touched the moon, and suddenly his canoe and trawler entered the whale's mouth. The whale took him to a place, and unexpectedly there, he could meet, mingle, and even make love with Maleha, his long-dead wife. After that, thanks to the whale's kindness, he went home. However, when he arrived on land, he found that the village had been devastated by the wind and waves. Many people wondered why Ayup was still calmly paddling the canoe and carrying a lot of fish. When asked, Ayup replied that it was all thanks to the whale's help, and he even said he had just met his wife in the sky.

It is clear that in this short story, the author (as well as the narrator) creatively and implicitly places the sea as the arena for the battle between the power of man and the power of God. However, this battle is constructed too formally and dogmatically because everyone understands that God cannot be contrasted with humans: God is the Creator, and humans are His creatures. As the Creator, God can do anything He desires, including taking Ayup to the sky, transforming him into a whale, bringing him together with Maleha, and saving Ayup from danger. Indeed, despite being poor, Job was a pious man. Therefore, if you look closely, in this short story, ideas (spiritual-religious-magical) are brought together in a free, diffuse, and ultimately intertwined way.

In contrast to some of the short stories that have been discussed, the short stories titled ‘Jiwa-Jiwa Laut’ (Livia Hilda, Bali Post, March 18, 2018), ‘Ziarah Laut Selatan’ (Risda Nur Widia, Suara Merdeka, May 12, 2019), and ‘Perahu Penjemput Arwah’ (Risda Nur Widia, Kompas, January 10, 2021) show the sea not only as a place to build stories or events but also as a meeting (battle) space between two worlds, namely the world of life (body) and death (soul). In the short story ‘Jiwa-Jiwa Laut’, the sea is a collection of souls for the dead. If the living (body) is summoned by burning incense, the souls turn into waves that touch the incense burner's feet while at the sea's edge. In the short story ‘Ziarah Laut Selatan’ (Pilgrimage to the South Sea), the sea is the provider of the chariot that takes humans (my character)—when sowing flowers on the beach (Parangtritis)—to meet the souls (spirits) of my father, mother, and grandfather in the depths of the sea. Although the context is different, the same can be seen in the short story ‘Perahu Penjemput Arwah’.

Conclusion

The preceding discussion shows that many Indonesian authors (short story writers) use the sea as a particular tool in constructing their works (short stories). It is evident through the study of newspaper short stories from the last decade (2010–2021). The evidence from this study of 25 short stories cannot be considered to represent the entire repertoire of Indonesian short stories from that period that use the sea to battle certain ideas, notions, and discourses (ideologies). The research team believes that many other short stories have gone unnoticed. However, the study of these short stories can serve as (temporary) evidence that in their works, Indonesian authors have creatively used the sea not only as a setting (place) but also as a space (space) for the battle of ideas (ideology) that criticizes socio-economic issues (capital crime), socio-political (power), spiritual-religious-magical, inner women (psychological), and how the relationship between the two worlds (land-sea, life-death, body-soul) should be.

In the resulting findings, it can be concluded that the authors of Indonesian newspaper short stories have created the ocean into at least four creative battle spaces and several subspaces. These spaces and subspaces include (1) economic battle space with capitalist and impact of capitalism subspaces; (2) moral battle space with action crime and power struggle subspaces; (3) inner battle space dengan serenity, sorrow relief, the battle between reality and desire, and the battle of life subspaces; and (4) surrealism idea battle space with the meeting space of two worlds, the endless search, surrealism-economics, and spirituality and imagery subspaces.

Indonesian short stories that pay attention to the sea (maritime) issue prove that Indonesian literature cares about the latest world issues, namely the issue of environmental ethics. After all, the sea, as part of the overall ecological elements that ensure the survival of human life, must be preserved and kept away from the black stains of the development of Era 4.0. Since our literature is proven to be heading in that direction, it is worthy that our literature (Indonesia) becomes an important part of world literature.

This research is limited to stories about the sea as a creative battleground in only 25 short stories in Indonesian newspapers from 2010 to 2021. Therefore, the findings are limited to only four aspects, namely economic, moral, inner, and surrealistic. Suppose the research material is expanded to other literary works, such as novels and poems, it is believed that unique concepts, ideologies, or discourses related to the ocean will be found more broadly. Thus, future research needs to be enriched with other study materials and supported by other theories.

Endnotes

References

- Alario Trigueros, M. T. (2019). Cuando los otros importantes eran siempre “ellas.” Arenal. Revista de Historia de Las Mujeres, 26(2), 575–605. https://doi.org/10.30827/arenal.v26i2.5580

- Anas, A. A., Ghazali, A. S., Dermawan, T., & Maryaeni. (2019). Ecopsychology and Psychology of Literature: Concretization of Human Biophilia That Loves the Environment in Two Indonesian Novels. The International Journal of Literary Humanities, 17(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.18848/2327-7912/CGP/v17i01/47-59

- Britland, K. (2022). The Queer Poetics of Hester Pulter’s Poem, “Of a Young Lady at Oxford, 1646.” Women’s Writing, 29(3), 382–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/09699082.2021.1971230

- Chatman, S. (1980). Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. Cornell University Press. https://books.google.co.id/books?hl=id&lr=&id=ewrOp9uPjYUC&oi=fnd&pg=PA9&dq=Chatman,+Seymour.+1980.+Story+and+Discourse:+Narrative+Structure+in+Fiction+and+Film.+Ithaca+and+London:+Cornell+University+Press.&ots=p6korZ2NbU&sig=q5dWFOAyBbi2IJwGEI1DOJGCcuQ&r

- Feldman, L. (2023). Do Imaginário Marítimo de Nabuco. Dados, 66(3), 20210106–20212023. https://doi.org/10.1590/dados.2023.66.3.295

- Foo, J., Hamdan, D. D. M., Amirul, S. R., Sapari, S. M., Janoni, N. H., & Jotin, E. (2022). Gender roles in the Anchovies Food Supply Chain — Bagang System in Mempakad Laut, North Borneo, Malaysia. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 11(2), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2022.11.2.07

- Grabarczyk, T. (2021). About the armament of the Polish knights once again. Studia Slavica et Balcanica Petropolitana, 2 (30), 164–169. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu19.2021.211

- Humas-Setkab. (2014). Pidato Presiden Joko Widodo pada Pelantikan Presiden dan Wakil Presiden Republik Indonesia, di Gedung MPR, Senayan, Jakarta, 20 Oktober 2014. Sekretariat-Kabinet.

- Kalashnikova, A. L. (2019). The Soul and the Sea: The Functioning of a Lyrical Situation in Fyodor Tyutchev’s Poetry of the 1850s-1860s. Vestnik Tomskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta. Filologiya, 59, 155–168. https://doi.org/10.17223/19986645/59/9

- Kharisma, T. L. (2019). “Nilai Karakter Cinta Lingkungan pada Novel Mata dan Manusia Laut Karya Okky Madasari.” Prosiding Seminar Nasional Bahasa Dan Sastra Indonesia (SENASBASA)Volume 3, Nomor 2, 991—999. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22219/.v3i2.3273

- Klymentova, O. V. (2022). Religious Advertising in Ukraine: Political and Social Contexts. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 14(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v14.i1.7969

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Inc.

- Lim, H.-S. (2022). Aspects and Background of Records Describing Goryeo as an Island in Medieval Islamic Literature and European Literature. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 11(2), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2022.11.2.05

- Mardatila, A. (2020, November). 5 Manfaat Laut bagi Kehidupan Makhluk Hidup, Produksi Oksigen Lebih Banyak. Www.Merdeka.Com. https://www.merdeka.com/sumut/5-manfaat-laut-laut-bagi-kehidupan-makhluk-hidup-produksi-oksigen-lebih-banyak-kln.html

- Maykut, P. S., & Morehouse, R. E. (1994). Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophic and Practical Guide. Psychology Press.

- Muñoz, M., Reul, A., Guijarro, B., & Hidalgo, M. (2023). Carbon footprint, economic benefits and sustainable fishing: Lessons for the future from the Western Mediterranean. Science of The Total Environment, 865, 160783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160783

- Noviana, F. (2020). Semiotic Study of Japanese Views on Sea in Hayao Miyazaki’s Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea. E3S Web of Conferences, 202, 07038. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202020207038

- Noviatussa’diyah, N., Sugiarti, S., & Andalas, E. F. (2021). Ekologi Budaya Suku Bajau dalam Novel Mata dan Manusia Laut Karya Okky Madasari. BELAJAR BAHASA: Jurnal Ilmiah Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa Dan Sastra Indonesia, 6(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.32528/bb.v6i1.3780

- Orcutt, J., Pomponi, S. A., Agardy, T., Bass, G. F., Doyle, E. H., Garcia, T., Gilman, B., Humphris, S., Koike, I., Lutz, R., Mcnutt, M., Moore, J. N., Iii, W. P., Thiede, J., & Lorandi, V. M. V.-V. (2003). Exploration of the Seas. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10630

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2016). The Ocean Economy in 2030. OECD Publishing.

- Parslow, J. (2020). The Levant, from utopia to chronotopia: an unsettled word for an unsettled region. Contemporary Levant, 5(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/20581831.2020.1710667

- Redaksi-ruangsastra. (2023). Ruang Sastra. https://ruangsastra.com/

- Roy, R. L. (2020). Negotiating Alienation and marginality in the Selected Verses of Indo-Guyanese Poet Mahadai Das. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 12(5). https://doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n5.rioc1s13n3

- Samuelson, M. (2010). Oceanic Histories and Protean Poetics: The Surge of the Sea in Zoë Wicomb’s Fiction. Journal of Southern African Studies, 36(3), 543–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2010.507539

- Sayuti, S. A. (1997). “Pragmatik Sastra.” Widyaparwa No. 49.

- Segers, R. T. (2000). Evaluasi Teks Sastra (Diterjemahkan oleh Suminto A. Sayuti dari buku The Evaluation of Literary Texts (1978)) (Suminto A. Sayuti (ed.)). Adicita Karya Nusa.

- Simangunsong, F., & Hutasoit, I. (2018). A Study of the development of Natuna Regency as a key site on Indonesia’s Outer Border with particular regard to national defense and security issues in the South China Sea. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 7(2), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2018.07.2.04

- Staley, L. (2016). Fictions of the Island: girdling the sea. Postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies, 7(4), 539–550. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41280-016-0028-9

- Sudibyo, S., Dewojati, C., Indrastuti, N. S. K., & Zuliana, R. (2021). Korona dalam Ruang Politik dan Poetik Sastra: Arena Diskursif Karya-karya Fiksi Komunitas Jejak Imaji Yogyakarta Di Era Pandemi. Bakti Budaya, 4(1), 2–19. https://doi.org/10.22146/bakti.1277

- Tim Redaksi. (2023). Laut. Wikipedia. https://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laut

- Webb, P. (2023). Introduction to Oceanography. https://rwu.pressbooks.pub/webboceanography/

- White, R. E., & Cooper, K. (2022). Qualitative Research in the Post-Modern Era: Critical Approaches and Selected Methodologies. Springer Nature.

- Xu, Y. (2023). An ocean of intercultural experiential learning. Sport, Education and Society, 28(1), 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1979952

- Yékú, J. (2020). Deference to Paper: Textuality, Materiality, and Literary Digital Humanities in Africa. Digital Studies/Le Champ Numérique, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.357

- Yin, R. K. (2015). Qualitative Research from Start to Finish. The Guilford Press.

- Zakaria, R. D. (2010). “Kajian Humaniora Novel Gipsi Laut Karya Rahmat Ali dan Pemanfaatannya Sebagai Alternatif Materi Pembelajaran Apresiasi Sastra di SMA” [Universitas Jember]. https://repository.unej.ac.id/handle/123456789/22480