Whaling in Brazil and its historical iconography

Abstract

The objective of this study is to analyze iconographies that show the whaling in the Brazilian Colony, dates back to the sixteenth century and had socioeconomic importance in the formation and implementation of people in the cost. This extractivist activity that involved the settlement of large cetaceans was a common scene in coastal areas, such as the Guanabara and Todos os Santos Bays, and Santa Catarina Inlets. In these visual documents we identified the main characteristics of whaling in Brazil: proximity to the coast, slave labor, specialization of work at sea, techniques of capture and processing, and the boats launched in the calm waters of the bays. The whaling iconography produced in Brazil have common elements, recognizable in the redundancy of certain visual arrangements: the chase, the harpooning, the towing, the shredding, the melting, and the storage. The most representative image of fishing is the dramatic moment in which man and animal meet since, in the Basque tradition, being close was paramount.

Keywords

Whaling, Iconography, Whale, Brazil

Introduction

Whaling is an economic, cultural, social, and historical activity in various locations worldwide. There have been many types of interactions between human populations and these cetaceans over the millennia. In the Western world, thought regarding the sea and its beings has been surrounded by traditions and innovations since ancient times. The whale, seen as a mythological being, feared as a sea monster, coveted as a natural resource, has more recently become a modern totem (Cohat, 1992; Kallang, 1993).

The different mentalities and perceptions toward whales are represented in Western iconography. In the history of Medieval Christianity, the whale is considered a symbol of rebirth and renewal in the representations of the biblical story of Jonah and the navigation of St. Brendan (Coelho, 2015). Whales, as representations of monsters, are part of the Latin bestiary in the fifteenth-century maps. An example of this is in the Marine charter, by Olaus Magnus, from 1539; Cosmography, by Sebastian Munster, 1544; and Theatrum orbis terrarum, by Abraham Ortelius, from 1585 (Silver, 2015, p. 264). Between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Netherlands, prosperous in technological innovations, trade, and art, created magnificent engravings with the theme of stranded whales, such as the works of Hendrick Golzius and Jan Saenredam (Silver, 2015, p. 272–275). In the nineteenth century, English Romanticism, with seascape painting, addressed the whaling theme from the production of Joseph Mallord William Turner, John Ward of Hull, Frédéric Martens, and John Wilson Carmichael (Hokanson, 2016).

The study of images produced in the context of world whaling — including maps, drawings, paintings, scrimshaws1, prints — is a fertile field for artistic analysis of the maritime world. Klaus Barthelmess explains that the interest in collections of maritime prints became more intense from the 20s of the twentieth century (Barthelmess, 2009, p. 643). Among the iconographic studies and prints from collection catalogs is the artistic production of whaling nations, such as the Netherlands, England, Germany, France, and the United States (Barthelmess, 2009, p. 644).

In the case of Brazil, little has been studied about the artistic works related to the phenomenon of whaling. Therefore, we are interested in analyzing the representations of whaling activity when this animal was seen as a natural resource of great economic interest due to the use of meat, bacon, bones, fins, tongue, and ambergris2. The visual works selected for this study correspond to four representations in different media and artistic techniques: an oil painting by Leandro Joaquim, dated between 1780 and 1790; an ex-voto in painted carving by an unknown author, dating from the late eighteenth century; a lithograph by Alphonse Beauchamp, and a watercolored lithograph by Hippolyte Taunay, both from the early nineteenth century.

Whaling in Brazil

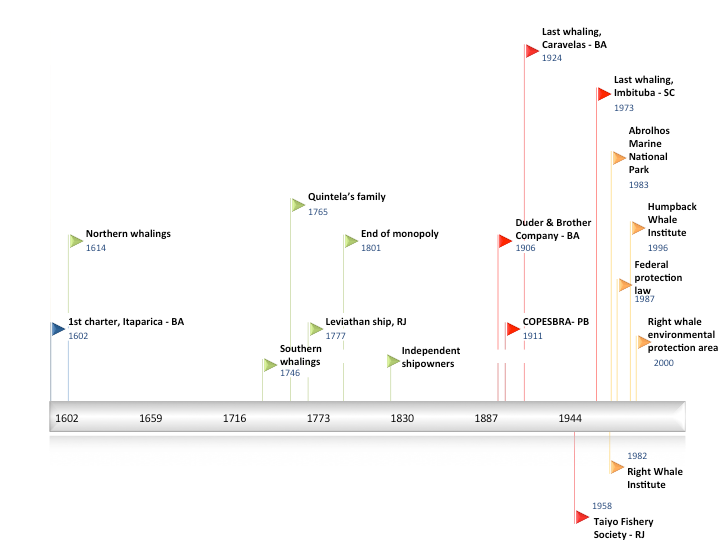

The practice of whaling3 in Brazil dates back to the sixteenth century and had socioeconomic importance in the formation and implementation of people in the territories of Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Santa Catarina. Whaling had greater expression in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the Northeast region; in the South and Southeast, the most significant period dates back to the last quarter of the eighteenth century, under the rule of the Quintela family4. We can establish a chronology for whaling activity in Brazil, separating it into three major periods: monopoly, independent shipowners, and the industrial phase (Figure 1). Our focus in this text comprises analyzing the pictorial representations produced in the first period, referring to the height of fishing through Royal concession.

In the states mentioned above, frames were built5 by the sea, in which stood a series of buildings intended for whaling. The buildings were grouped according to their functionality: buildings for the care of the body and soul, buildings for living, productive buildings, support buildings, and production guard. We highlight the productive building as the "nerve center" of a frame, in the words of Myriam Ellis, which characterized this type of enterprise as the Boiling house, with The Butcher's Workshop and the Furnace Workshop (Ellis, 1969, p. 63). The fat layer of the whales was transformed into whale oil6, used primarily for lighting (Figure 2).

Randall Reeves and Tim Smith identify eleven eras of whaling in the world, classifying them by capture technique, time, and geographical area (Reeves and Smith, 2006). One of these techniques is the Basque type, which, brought by the 'Biscainhos' to Bahia in 1602, was widespread and passed on to other regions of Brazil (Valdés Hansen, 2016). The Basque type of whaling was done with whaleboats near the coast, when they approached the whales and launched the harpoons, the strategy being to harpoon the calf and then the adult animal (Figure 3). This fishing technique did not allow stocks to be renewed or for there to be an efficient use of the raw material, being harshly criticized by José Bonifácio de Andrada, in a work from 1790 (Andrada, 1977).

The population that worked in the whaling stations fulfilled different activities. Free individuals and slaves lived together in these whaling villages. Slave labor was intended for the most arduous and manual services, in dragging the whale and heating the boilers. The activities with a specific specialty — such as cooper, blacksmith, and craftsmen — were salaried. And the functions of the whalers — harpooners, helmsmen, and rowers — earned per whale captured (Ellis, 1971, p. 321).

Whaling was an important activity in Brazil, especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, for the following reasons: generation and supply of energy for public and private lighting, export of products derived from whales, consolidation, and fixation of the population on the coast, construction of vessels, generation of income for the Kingdom, and greater development of cabotage, trade, and communication between the areas of whaling in Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Santa Catarina (Ellis, 1966, p. 432).

Whaling iconography

Undoubtedly, the best-known iconography in Brazil regarding whaling is the painting by the painter from Rio de Janeiro, Leandro Joaquim (1738–1798). The canvas, in an elliptical shape, measures 0.88 m by 1.140 m and is part of a six-panel collection at the Museu Histórico Nacional7 (Figure 4). Whales appear throughout the maritime portion, with a total of eleven whales being represented by the bay.

The artist Leandro Joaquim designed 16 landscape canvases of the city of Rio de Janeiro to decorate the pavilions on the public promenade, commissioned by Viceroy D. Luis de Vasconcelos. The works are dated between 1780 and 1790 (Silva, 2006). Leandro Joaquim inaugurated the landscape painting in Brazil as the main element of representation, in addition to being an excellent miniaturist:

The artist wishes to document the city in its cultural and individual specificities, which demonstrates the not only profane but official character of his painting. The pictorial construction is simultaneously planar and cycloramic, refutes the perspectives, organizing the scene in horizontal bands to the top and to the sides, in a turn by the coastal edge of the city and the bay, which admits a game of reciprocities beyond its urban limits (…) (Carvalho, 2007, p. 35, our translation).

In this framework, it is possible to identify the entire whaling operation8 in Guanabara Bay in the mid-eighteenth century: fishing, removal of captured whales, shredding, and oil calculation for the Whaling station of São Domingos, in the District of Vila Real da Praia Grande, currently Niterói. In the foreground, the island of Villegaignon, the fort with the hoisted flag, and several whaling boats with sails on the mast in great movement. Ahead, vessels with their sails collected and anchored in the bay, which are probably galleons by the nautical architecture.

In the center of the seascape, we see all the stages of whaling: chasing, harpooning, towing, and shredding the cetaceans to the contract factory (Figure 5). During the chase, two whales squirt out water vapor. The presence of open eyes and squirt indicates they are alive. Leandro Joaquim painted the eyes of whales in a curious way and of disproportionate size, with an aspect and position similar to that of fish.

In a central position in the painting, a whale appears with the squirt splashing blood in the air, after being harpooned. Two other whales are in tow and two others, following the scene, are already being shredded. The whalers represented are white men, which indicates that they are a free population, hired on a seasonal basis.

The whales represented present the characteristics of right whales: V-shaped squirt pattern, black skin color, smooth back, without a dorsal fin, and a robust body shape (Instituto de Pesquisas Cananeia, 2013, p. 22). The right whale was the correct whale to kill, hence its English name, for its behavioral characteristics and the quality of the fins, being preferred by whalers. As Felipe Valdés Hansen points out: “On account of its large size, oil production was achieved by cooking the grease, the length of the baleen and floatability of the corpse, while the humpbacks and sperm whales took a back seat and were only caught occasionally (Valdés Hansen, 2016, p. 728)”.

The upper left corner depicts the dismemberment of two whales when enslaved individuals approached in a canoe or entered the shallower waters, equipped with cutting instruments of all sorts. The process begins from the initial cut, separating the head and caudal fin from the body. Soon after, the longitudinal cut opens the belly in two bands. The meat and bacon are removed in cuts transversal to the animal's spine (Figure 6).

At the end of the Frame, two slaves pull the whale using a rope attached to the capstan. The slaves separated the bacon, which they burned in pots in a shed, which would be the frying device. In the next building, the barrels with the already purified oil were stored in the tank house. The representation of the stages of whaling fulfills a didactic role for the public, showing, step by step, each action, as a storyboard.

Regarding the architectural configuration, Maria Augusta Evangelista Fernandes analyzes the remaining structures of the Whaling station of São Domingos and concludes that:

(…) said buildings were designed in Mannerist or Jesuit style, because they present a robust, heavy appearance, of powerful masses, with quadrangular or segmented arch spans in rhythms characteristic of the style. Its architectural structure stands out in the landscape surrounding it, and the severity of its formal aspect is emphasized by the slope structure, resulting in the volume of a pyramid trunk (Fernandes, 2002, p. 57, our translation).

In the background, we see the geological formation of Guanabara Bay with its inselbergs. From left to right, it is possible to see Praia Grande, the Fort of Gragoatá, the island and the Church of Boa Viagem, Jurujuba Bay, Pico, the Fortresses of Santa Cruz and Laje, Barra, and Pai Island (Ellis, 1969, p. 80).

Another elliptical panel by Leandro Joaquim, "Visita de uma Esquadra Inglesa na Baía da Guanabara", presents a configuration similar to the picture of whaling, with the Fort Villegaignon and the view of the mountainous landscape, depicting the whaling station with all its buildings. In the fishing framework, the focus is the whaling operation; the framework of the visit of the English squadron shows the entire trapiche and a rectangular building next to it.

Another iconography of erudite aspect, made for local circulation, but of valuable visual message, is the ex-voto9 existing in the Chapel of the Whaling station of Piedade, on the central coast of Santa Catarina (Comerlato, 1998) (Figure 7). Executed in a devotional character, the work shows us how the fishermen respected the sea and begged the intervention of the Holy protectors in their daily work. The ex-voto was produced in wood cut into volutes and counter-volutes, referring to the religious carving, is small in size, with 43.2 x 42.8 x 1.3 cm (Richter et al., 2016).

The ex-voto follows the Portuguese model, presenting two thirds of the surface with the representation of the miracle and, in the lower third, the presence of the caption, with the parts and their limit delimited by a golden line. Another characteristic that we attribute to the Portuguese model is the way in which the agent of the miracle, in this case Our Lady Of Mercy, was presented in the firmament and enveloped in clouds (Silva, 1981, p. 58). The scene of the disaster is probably painted in oil, and, due to its pictorial quality, we believe it to be of foreign workmanship, given the artistic development in southern Brazil in the second half of the eighteenth century.

In the foreground is the dying whale positioned with its head in front, with a contorted body, a harpoon embedded in its back and a suspended caudal fin. In the middle of the rough sea and marked with ridges of water, on the right portion of the painting, is a person, which the final part of the description indicates to have drowned. In the background, two lifeboats, one on each side in the composition, with men waving. Above the horizon line, the cloud-filled blue sky is crowned by the appearance of the patron saint of the said frame. The caption was written on the support itself, in cursive, on a black background and in white ink, as follows:

Mo que fez N S da Piedade ao Timoneiro Anto Cardoso e a Augusto Frano d Oliveira q sahindo ao mar em lancha de pesca deste anno d 1.765 tendo justamente uma Baleia ao par de outra que lhe deu com tão grande pancada na lancha à quebrou lançando ao mar todos os q estavam nella os quais nadando seis horas em cima d’água sem esperanças de salvação chamaram pela padroeira a N S que lhe foi servidos depressa lhe acudiu a lancha de q: não tinham esperanças algumas e ela salvou toda gente menos um preto que já tinha morrido afogado10.

Thus, we can say that, in addition to whales being the basic raw material for a whaling station, the man-whale relationship did not occur only in the economic sphere but also in the religious, imaginary, and symbolic conception of this whaling population in front of these animals. Even today, we do not know another ex-voto who refers to the whaling universe in Brazil.

The next two images are lithographs produced to illustrate books of encyclopedic content by French writers of the early nineteenth century, relating to the history of Brazil. The first lithograph we will analyze composes the opening of Volume VIII of Alphonse de Beauchamp's book, published in French in 1815 and translated into Portuguese in 182011 (Beauchamp, 1820) (Figure 8).

In the foreground, we see two canoes with a crew of five men in motion, paddling and pointing at the wounded animal. Note that some men are dressed in few garments, a white cloth surrounds their waists in a kind of skirt, with bare breasts. Some wear a turban on their heads; others a top hat. The turban is an haussá inheritance of Islamic devotion brought by enslaved Africans from Central Sudan. According to José Reis, the haussás served the whaling station of Itapuã and others nearby. The author relates the ability of these peoples with white weapons, and may have stood out with harpoons and spears (Reis, 2014, p. 79). The top hat, on the other hand, is part of the clothing of North American whalers.

In the right corner, the interest of the attention of fishermen, we can visualize a harpooned whale, writhing and spraying water. The squirt is a single jet, like that of humpback whales. The place where the harpoon is jammed is the best place for the certain death of a whale, just below the head. In the two whales represented, we see the concern to draw the bulges of the head, the squirt, the texture of the skin, and the pectoral fins similar to those of fish and dorsal fins.

In the left corner in the background, a row of men on the seashore drags a whale to dry land, while others accompany the operation in small canoes on the water. Other huddled men point to a galleon grounded on the shore and another part of the group appears to be heading towards the whale. In a higher plane, buildings appear grouped, next to palm trees and three people, and two buildings contain chimneys.

Because Alphonse de Beauchamp never set foot in Brazil and his first three books are a literal translation of the book History of Brazil, by Robert Southey, a plagiarism denounced by the author himself at the time, we can draw some conclusion about how this engraving was produced (Medeiros, 2010, p. 132; Southey, 1810). First, the fact that each volume begins with an engraving and the whaling theme of Volume VIII drew our attention. According to the author himself, the description of whaling was collected from reports of travelers and informants (Beauchamp, 1820, p. 187–188).

Given the above, the execution of an image depicting whaling was certainly done in Europe, based on the text and other iconographic references. The clothing of the enslaved draws our attention for bringing elements such as the turban and top hat, referring us to the North American whaling reality. The absence, in the lithography, of whaleboats, characteristic of whaling in Brazil, is also noticeable, replaced with monoxile canoes. Finally, the purpose of lithography was to represent the method:

The system and movements which they carried out to catch them, to then transform them into oil, are as follows. The men sail in small boats to catch the whales, and bring them to dry land; when they are sighted, they throw harpoons or grappling hooks and unfurl a lengthy line or rope in armfuls or balls; this causes a rapid movement from the whales which are tormented by the injury and pain; they chase behind them in the boats for as long as it takes until they are bleeding and weak and, sometimes, already dead, they are pulled to the beach, or they come to the coast naturally and with little cost. They are then taken to the houses in which the oil is produced, which are situated close to the beach (Beauchamp, 1820, p. 185–186).

After the opening of the ports and the arrival of the Portuguese court to the Colony, scientific and artistic expeditions were welcomed since they sought to offer a synthesis of the exoticism, the picturesque, and the exuberance of the tropics. Numerous landscape paintings emerge in this context by artists such as Hippolyte Taunay, Jean Baptiste Debret, and Johann Moritz Rugendas. As Ana Maria Belluzzo explains:

Finally, the theme inseparable from the experience of the nineteenth-century traveler is the landscape. With the coming of the Portuguese court to Brazil, especially after independence, professional artists arrive in the country, dilettantes with mastery of drawing. Anchor in Rio de Janeiro passengers of tourist trips around the world. They have an educated vision of the picturesque's aesthetics and seek to enjoy characteristic landscapes (Belluzzo, 1996, p. 18, our translation).

Associated with a man of letters, Ferdinand Denis, Hippolyte Taunay, on his coming to the city of Salvador, executes a watercolor to compose the book Le Brésil, ou Histoire, Moeurs, Usages et Coutumes des Habitans de ce Royaume12, which depicts the most dramatic moment of the whaling operation: the capture (Figure 9). We consider that this engraving was made in the same place depicted, between 1816 and 1822, the year of its publication. We estimate that his observation point was at Morro do Cristo, precisely the place that offers the same viewing angle depicted on the screen. Ferdinand Denis assures that, “The aim of the engravings, which adorn this work, is above all to portray with exactness the nature of the country; Mr. H. Taunay drew on site most of the views of Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, and Pernambuco.” (Gomes Júnior, 2012, p. 113).

In these four years of stay in tropical lands, Ferdinand Denis worked for three years at the French consulate in Bahia (Biblioteca Nacional, 2005, p. 90). In the work entitled Brésil, published in 1837, the author comments that he knew other references from naturalists and travelers who wrote about whales and still poses as an attentive spectator of the whaling effort: “The author of this news saw a whale shredded by iron shovels, with which huge portions of bacon were raised” (Denis, 1980, p. 251).

The engraving is an accurate iconographic document of whaling in eighteenth-century Bahia13. In the foreground, the agony of the harpooned whale is represented with care by the launch of water into the heavens with the beating of the tail, the head in fury, and the spray pouring like a fountain. The scene of the whale harpooning reveals the high specialization required by this type of fishing. The number of fishermen embarked varied between 8 and 10.

In Figure 9, the whaling boat in the foreground draws our attention to detail. The different colored stripe identified the company on the side of the whaling boat. The flag had a different color for each harpooner, marking the possession and right over the harpooned animal. Another singular detail in this iconography is the record of the function of the boy of arms, who is being helped by another: when launching into the sea, he had to dive and close the whale's mouth with an immense rope. This brave feat must have surprised Taunay, who had the man depicted descending amid the waves, which were breaking on the hull of the vessel.

In the background, a lifeboat with two sails on a mast is in an observation position. The equipment is ready, the harpoon from the vessel's bow, the flag that identifies the whaling company in hand. This time, it was not they who succeeded in fishing. In the third plane, in the right corner of the image, the rocky point with the Fort Santo Antônio da Barra and the lighthouse appear. In front of it, the sand cord is covered by vegetation, emphasizing the coconut grove, Taunay and Denis describe the Barra to the fort with a landscape bordered by coconut groves (Taunay and Denis, 1822, p. 55). On the horizon, we see the silhouette of the Island of Itaparica.

Regarding the representation of the whale, there is no concern in detailing its morphological characteristics. The trace of the caudal fin, the size of the body, and the squirt show us it is a whale. Taunay and Denis write that, in Bahia, the whales caught were smaller than those of the North Atlantic, and their baleens were also small, which leads us to assume that they were from humpback whales14 (Taunay, 1822, p. 53–55).

Final Considerations

The uniqueness of each whaling iconography presented here is answered by the contexts of production and circulation of these works. Previous works have certainly influenced the iconography produced in Brazil since they resemble image production from Europe and the United States. The form in which the caudal fins are represented in the diving position, squirt, the harpooning site, head details, the chase, the harpooning, the towing, and the accidents form an iconographic repertoire common to the logbooks15 of whaling ships, scrimshaws, to the drawings of travelers in other North Atlantic whaling areas.

Therefore, the iconographies represented here have common elements, recognizable in the redundancy of certain visual arrangements: the chase, the harpooning, the towing, the shredding, the melting, and the storage. We related the analyzed work and the stage of the whaling operation, signaling its presence in green, as presented in Table 1:

| Leandro Joaquim | Ex-voto | Alphonse de Beauchamp | Hippolyte Taunay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chase | Chase | Chase | Chase |

| Harpooning | Harpooning | Harpooning | Harpooning |

| Towing | Towing | Towing | Towing |

| Flensing | Flensing | Flensing | Flensing |

| Melting | Melting | Melting | Melting |

| Storage | Storage | Storage | Storage |

The most representative image of fishing is the dramatic moment in which man and animal meet since, in the Basque tradition, being close was paramount. This meeting could have two outcomes: either the whale could be victorious or survivor, or the final link would be the glory and triumph of whalers before the largest animals in the South Atlantic.

Endnotes

References

- Afonso, J, 1998. Mar de Baleias e de Baleeiros, Direcção Regional de Cultura, Angra do Heroísmo.

- Andrada e Silva, J. B. de, 1977. Memoria Sobre a pesca das Baleas, e extração de seu Azeite; com algumas reflexões a respeito das nossas Pescarias. Memorias Economicas da Academia Real das Sciencias de Lisboa.1790. Tomo II, (reedição), Fundação Brasileira para a Conservação da Natureza, Rio de Janeiro, pp. 388–412.

- Balbi, A, 1834. Abrégé de Géographie, second ed. Edité par Chez Jules Renouard, Paris, viewed 08 August 2018, https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_7-T5Cz2ElBQC.

- Barthelmess, K, 2009. Basque whaling in pictures, 16th-18Th century. Itsas Memoria. Revista de Estudios Marítimos del País Vasco, Untzi Museoa — Museo Naval, Donostia- San Sebastián, 6: 643–667, viewed 31 August 2018, http://um.gipuzkoakultura.net/itsasmemoria6/643-668_barthelmess.pdf.

- Beauchamp, A. de, 1820. Historia do Brazil desde seu descobrimento em 1500 até 1810: vertida do francez, e accrescentada de muitas notas do tracdutor, offerecida a S.A.R. o serenissimo senhor Dom Pedro de Alcantara, principe do Brazil, Tomo VIII. Na Impressão de J. B. Morando, Lisboa, viewed 13 August 2018, http://www2.senado.gov.br/bdsf/handle/id/520906.

- Belluzzo, A. M., 1996. A propósito do Brasil dos viajantes. Revista USP, São Paulo, 30: 8–19, viewed 12 August 2018, https://www.revistas.usp.br/revusp/article/view/25903/27635

- Biblioteca Nacional, 2005. Iconografia baiana do século XIX na Biblioteca Nacional, Edições Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro.

- Bloch, A. (1982). Enciclopédia Ilustrada do Brasil, Bloch, Rio de Janeiro. vols. 07 e 09.

- Brito, C., Vieira N., Jordão, V., Teixeira, A., 2016. Digging into our whaling past: Addressing the Portuguese influence in the early modern exploitation of whales in the Atlantic. Environmental History in the Making. 7: 33–47, Doi: 10.1007/978-3-319- 41139-2_3.

- Carvalho, A. M. F. M. de., 2007. Da Oficina à Academia: a transição do ensino artístico no Brasil. Porto: Universidade do Porto. Martins, Fausto Sanches (coord.). Artistas e Artífices e a sua mobilidade no mundo de expressão portuguesa. Faculdade de Letras. Departamento de Ciências e Técnicas do Património, p. 31–40, viewed 03 September 2018, http://ler.letras.up.pt/uploads/ficheiros/6110.pdf.

- Cohat, Y., 1992. Vie et mort dês baleines, Gallimard, Paris.

- Coelho, A. F. S., 2015. O imaginário das ilhas atlânticas no universo medieval islâmico-cristão. Dissertação (Mestrado em História do Mediterrâneo Islâmico e Medieval) — Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, viewed 17 September 2018, http://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/24321/1/ulfl207957_tm.pdf.

- Comerlato, F., 1998. Análise espacial das armações catarinenses e suas estruturas remanescentes: um estudo através da Arqueologia Histórica. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) — Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre.

- Denis, F., 1980. Brasil, Ed. Itatiaia, Belo Horizonte/ Ed. da USP, São Paulo.

- Diener, P., 2013. Reflexões sobre a pintura de paisagem no Brasil no século XIX, Perspective, viewed 23 April 2018, http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/5542, DOI: 10.4000/perspective.5542.

- Ellis, M., 1957. Iluminação no Brasil Colonial. Revista do Arquivo Municipal, 173: 145–163.

- Ellis, M., 1966. As Feitorias Baleeiras Meridionais do Brasil Colonial. Tese de livre docência apresentada à Cadeira de História da Civilização Brasileira, Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo.

- Ellis, M., 1969. A baleia no Brasil Colonial, Melhoramentos, São Paulo.

- Ellis, M., 1971. Escravos e assalariados na antiga pesca da baleia (Um capítulo esquecido da história do trabalho no Brasil Colonial). In: Simpósio Nacional dos Professores Universitários de História, 6, Goiânia. Anais do VI Simpósio Nacional dos Professores Universitários de História. Trabalho livre e trabalho escravo. São Paulo: FFLCH-USP, 2011. v. 1, p. 350–351. Respostas às intervenções dos simposistas.

- Fernandes, M. A. E., 2002. O casario histórico da Ponta da Armação, Diretoria de Hidrologia e Navegação, Niterói.

- Figueiredo, B. H. R., 2015. Ex votos do período colonial: uma forma de comunicação entre pessoas e santos (1720–1780), in: Oliveira, J. C. A. de (org.). Ex-votos das Américas: Comunicação e memória social, Quarteto, Salvador, pp. 47–86.

- Figueiredo, J. M., 1996. Introdução ao estudo da indústria baleeira insular, Museu dos Baleeiros, Pico.

- Gilje, P., 2016. To swear like a sailor: Maritime Culture in America, 1750–1850, University of Oklahoma, Normam.

- Gomes Júnior, G. S. 2012. Arte da paisagem e viagem pitoresca: romantismos entre academia e mercado. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 27: 107–230, viewed 8 August 2018, http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbcsoc/v27n79/a07.pdf.

- Hokanson, A., 2016. Turner’s Whaling Pictures. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New York, vol LXXIII, no 4, viewed 12 August, 2018, https://issuu.com/metmuseum/docs/spring_2016_bulletin.

- Instituto de Pesquisas Cananeia, 2013. Guia Ilustrado de Mamíferos Marinhos do Brasil, first ed. Labograf, Cananéia, viewed 9 August 2018, http://ipecpesquisas.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/GUIA_ILUSTRADO.pdf.

- Kalland, A., 1993. Management by totemization: whale symbolsim and the anti-whaling campaign. Arctic, 46: 124–133, viewed 1 August 2018, http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic46-2-124.pdf.

- Lago, P. C. (org.), 2001. Iconografia brasileira: Coleção Itaú — Sala Alfredo Egydio de Souza Aranha, Itaú Cultural, Conta Capa Livraria, São Paulo.

- Lucchesi, M., 2015. Rio 450 anos: uma história do futuro, Fundação da Bilioteca nacional, Rio de Janeiro, viewed 8 August 2018, http://bndigital.bn.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Cat%C3%A1logo-Rio-de-Janeiro-450-Anos-Uma-Hist%C3%B3ria-do-Futuro.pdf.

- Machado, O., Gerlach, G. (orgs.), 2007. São José da terra firme, Floriprint, São José.

- Medeiros, B. F., 2010. Alphonse de Beauchamp e a história do Brasil: escrita da história, querelas historiográficas e leituras do passado no oitocentos. Almanack Braziliense. São Paulo, 11: 131–138, viewed 13 August 2018, http://www.almanack.usp.br/almanack/PDFS/11/almanack.pdf.

- Proulx, J. P., 1986. Whaling in the North Atlantic from earliest times to the mid-19th century, Minister of Supply and Services Canada, Ottawa, viewed 8 August 2018, http://parkscanadahistory.com/series/saah/northatlanticwhaling.pdf.

- Quiroz Larrea, D., 2012. Cazadores tradicionales de ballenas en las costas de Chile (1850–1950), Andros Impresores, Santiago de Chile, viewed 12 August 2018, http://www.cdbp.cl/652/articles-26011_archivo_01.pdf.

- Reeves, R. R., Smith, T. D., 2006. A Taxonomy of World Whaling. Operations and Eras. In: Estes, J. A., Demaster, D. P., Doar, D. F., Williams, T. M., Brownell Jr., R. L. (eds.), Whales, whaling, and ocean ecosystems, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

- Reis, J. J., 2014. Há duzentos anos: a revolta escrava de 1814 na Bahia, Topoi, 15: 68–115, viewed 31 August 2018, http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2237-101X2014000100068&lng=en&nrm=iso.

- Richter, F. A., Althoff, F. R., 2016. Arte Sacra. Patrimônio Catarinense. Inventário de Bens Móveis Sacros — Etapa III, Fundação Catarinense de Cultura, Florianópolis.

- Silva, D. M. D., 2006. Em busca de uma cidade ideal: Representações de poder no Rio de Janeiro do Vice-Reinado. História, imagens e narrativas. 2: 29–44.

- Silva, M. A. M. da, 1981. Ex-votos e orantes no Brasil: leitura museológica, Museu Histórico Nacional, Rio de Janeiro.

- Silver, L., 2015. De Profundis: Linear Leviathans in the Lowlands, in: Spinks, J., Eichberger, D. (Eds.), Religion, the supernatural, and visual culture in early modern Europe: an álbum amicorum for Charles Zica, Brill, Leiden/Boston, pp. 260–282, viewed 13 August 2018, https://issuu.com/uomodellarinascita/docs/smrt_191_religion__the_supernatural.

- Southey, R., 1810. History of Brasil. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme, viewed 13 August 2018, http://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/handle/id/182933.

- Taunay, T. M. H., Denis, F., 1822. Le Brésil ou histoire, moeurs, usages et coutumes des habitans de ce royaume. Ouvrage orné de nombreuses gravures d'après les dessins faits dans le pays par M. H. Taunay, Nepveu, Paris. Tomo 4, viewed 6 August 2018, https://digital.bbm.usp.br/handle/bbm/7127.

- Valdés Hansen, F., 2016. Balleneros vascos en Brasil, Itsas Memoria. Revista de Estudios Marítimos del País Vasco, Untzi Museoa-Museo Naval, Donostia-San Sebastián, 8: 725–740. viewed 7 August 2018, https://itsasmuseoa.eus/wp-content/uploads/pdf/ITSASMEMORIA_8.pdf.