Ballina’s Big Prawn, local fishing heritage and place branding

Abstract

The Big Prawn statue erected in Ballina, on the north coast of the Australian state of New South Wales, in 1989 belongs to a genre of roadside ‘big things’ that commenced in Australia in the 1960s. The statue has come to be a prominent — if frequently contentious — landmark within the town and an icon of it for tourists. Its symbolism reflects Ballina’s status as a coastal location with a small fishing fleet and dedicated harbour and magnifies that aspect as a projection of the town to both visitors and a general social media public. As such, the Big Prawn has both a cultural ‘life of its own’ and a relationship to Australia’s national circuit of roadside big things and with other symbols of Ballina mobilised by the town council and its tourism promotion. The article provides a history of the development, prominence and impact of the Big Prawn in cultural media, its relation to cultural debates about aesthetics and heritage in Australia and the manner in which its sign can be understood to operate within a coastal location heavily dependent on tourism income.

Keywords

Ballina, Big Prawn, emblems, iconography, fishing heritage

Introduction

It’s pretty clear, even from 100m away, that there’s no throwing this shrimp on the barbie1 — the concrete and fibreglass prawn stands at nine meters tall, 20-something meters wide and weighs 35 tonne, making it one cracker of a crustacean. (‘Blonde Ambition’, 2016)

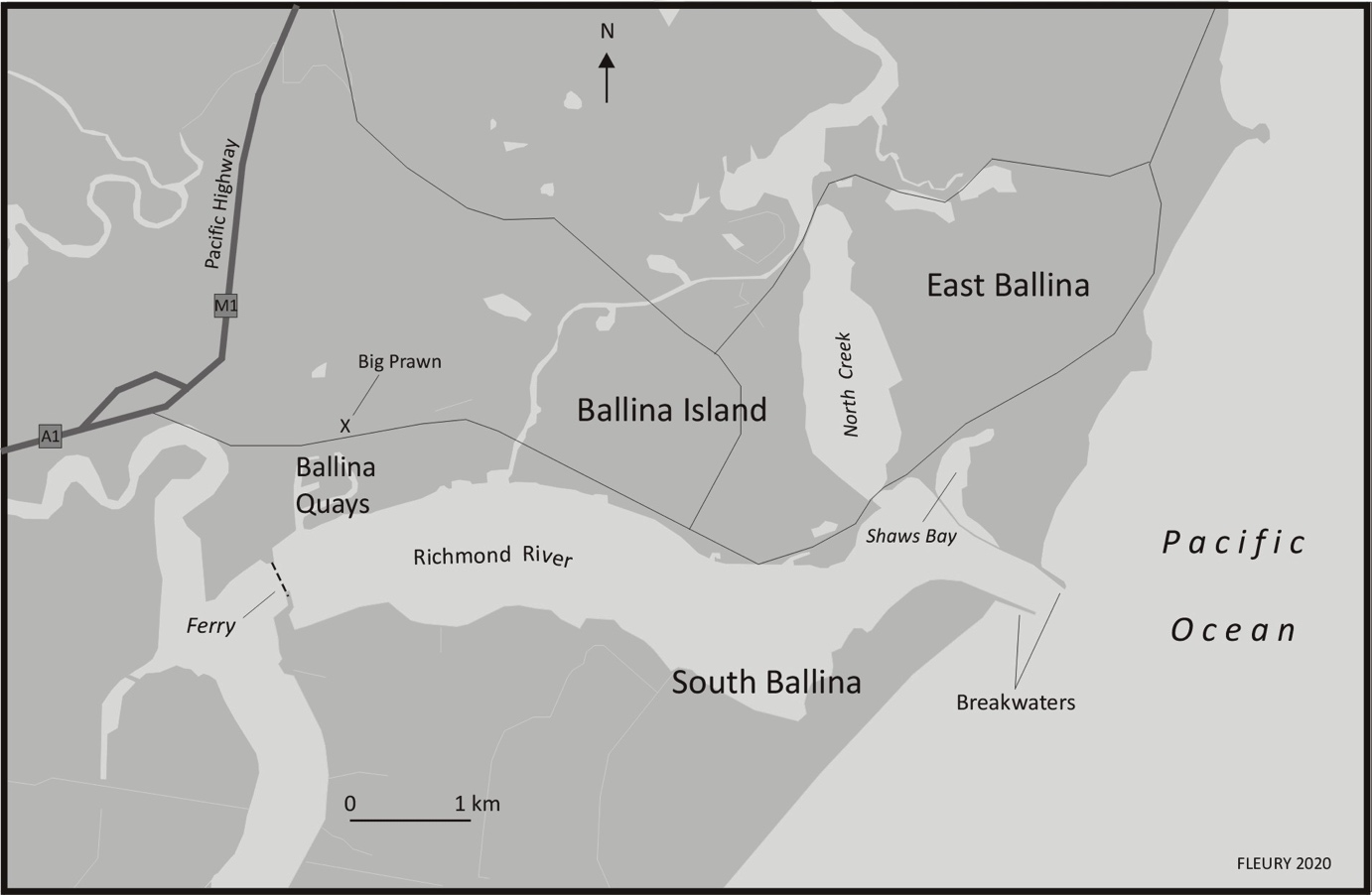

Ballina is a small town in far north New South Wales, Australia (current population c27,000), located at the mouth of the Richmond River and the Pacific Ocean.2 The town was established in the 1830s by European settlers and its development involved various acts of violence and the dispossession of the indigenous Bundjalung clan who lived around the river estuary. The town has a small fishing fleet that operates from a harbour close to the town centre (Figure 1) and has become known for the quality of the prawns that have been caught and retailed locally since prawning operations began in the late 1940s (White, 2015). Tourism visitation to the region increased steadily since the initial establishment of a road route between Sydney and Brisbane in 1909 and a series of improvements to (what became known as) The Pacific Highway, including the sealing of the entire route in 1958. The Pacific Highway ran through the western section of the town until 2011, when a bypass was built, substantially reducing traffic flows through the town’s western section whilst allowing easy access on and off the highway. Tourism now provides Australian $245 million to the local economy (Ballina Shire Council, 2019: online) and the area has also become known as an attractive retirement destination with a number of retirement estates and residential care facilities. Since 1989 it has also been known for the Big Prawn (henceforth referred to as the BP), a visually unmissable roadside ornament on its western access road that has become something of a (controversial) emblem for the area. The BP first appeared in 1989 when a small, retail block opened with a concrete and fibre-glass statue of the head and middle tail portion of a gigantic prawn fixed over a second storey, rectangular, glass-fronted viewing area,3 its head protruding over the front carpark and its truncated tail dropping down behind the building (Figure 2). While unusual, the BP, a massively scaled-up representation of a boiled (and thereby pink-coloured) Black tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon), is an example of a genre of giant objects constructed as roadside attractions across Australia since the 1960s. The first examples of this phenomenon were a large dinosaur (named ‘Ploddy’) installed at the Australian Reptile Park in Somersby (New South Wales) in 1963 (Markwell & Cushing, 2010: 89–93), and the Big Banana at Coffs Harbour, constructed in 1964. The latter is a significant precursor to Ballina’s BP in that it opened to a highly mixed local reception but went on to become an accepted symbol of the area and a regular roadside stopover for highway travellers (Leiper, 1997).

While eye-catching roadside attractions are relatively common internationally, and were pioneered in the United States (Hollis, 1999; Genovese, 2006), many US examples do not have the same close relation to and promotional focus on locality and local product that is evident in Australia. The history and cultural significance of large Australian roadside attractions (such as the BP) in the late 20th century was explored by Ruth Barcan in her detailed study ‘Big Things: Consumer Totemism and Serial Monumentality’ (1996). Referring to the national network of “big things” that developed in the 1980s and early-mid 1990s, she asserted that the “plethora” of them “can be seen to contribute to a sanguine myth of Australian nationhood: Australia as a cornucopia, a land of abundance” (1996: 31). This claim supported by the relationship of big things to local commodity specialisms. The Big Banana, for instance, symbolises the concentration of banana plantations around Coffs Harbour while the Big Merino indicates Goulburn’s claim to be the “fine wool capital of the world” (VisitNSW, n.d.). As Barcan neatly characterises, these roadside structures “stand in metonymic relation to the region they represent; that is, they function as a part standing in for the whole [and] are markers that have themselves become sites” (1996: 31–32) and are, “in the short-hand way of tourist iconography”, “a fascinating blend of place-makers, architecture, popular art and advertising” (1996: 34). With regard to tourists’ engagements with such “big things” she draws on Cultural Studies’ address to the textual plays that late 20th century cultural artefacts engaged in and the knowing parodies involved in upscaling everyday material artefacts to gigantic dimensions. Indeed, she contends, more generally, that patrons of such attractions are “post-tourists” who engage “in a knowing and sometimes whimsical play of signifiers” along their routes (1996: 37). Stockwell and Carlisle (2003) have also contended that the specifically Australian quality of sardonic, anti-authoritarianism known as larrikinism underpins the big things in a manner that offends establishment tastes:

It is a form of low art, a form of trash culture… City planners and the upper middle class tend to denigrate these structures so at odds with their images of beautiful cities, so blatantly bastions of commercialism and so big that they run the risk of obscuring and obliterating real art… Big things are criticised as ugly, kitsch, tacky and giving a wrong impression of a town.

Complementing these approaches, Cushing (2007: 21) characterised the Pacific Highway as a “known and appreciated travel corridor that featured “a rich variety of signs of place” through which it “signposted the passage through space” (2007: 21). In the light of continuing upgrades to the route that included the bypassing of established roadside amenities and attractions, she contended that “the formal recognition and promotion of the heritage significance of the bypassed sections of the highway could protect this heritage resource” and help bypassed towns “salvage” the local economies depleted by declining volume of visitors. In this regard, she identified that environmental impact studies (EISs) uniformly ignored cultural heritage aspects, identifying that in the case of the IES conducted on the route of the Ballina bypass “just three items of European heritage were mentioned, two residential buildings and one railway embankment”, completely ignoring the BP, which she describes as a “well known and well loved” structure that helps to give the Pacific Highway its character and interest in the area (2007: 24).

A different perspective has been provided by Kent Watson, from the web-based organisation Monument Australia, whose website identifies that it is concerned to identify and preserve monuments and memorials that “reflect important values within the community that should be documented and preserved”. Without specifying his aesthetic criteria, Watson has described many roadside big things as “blights on the landscape” despite the local purpose behind them:

Some communities erect some 'big' structures to emphasise something about their place, such as its agricultural or pastoral produce. I am sure communities had good reasons to build them, and that they serve some purpose, but just as a personal opinion I think they are as intrusive as roadside advertising signs. (Mercer, 2017)

The status of such roadside attractions is not just a matter of casual subject debate but, rather, a significant factor with regard to the maintenance and future of such structures, the majority of which were not designed and constructed with longevity as a major concern. The deterioration and decay of many roadside big things and the question as to who is responsible for their upkeep (or demolition and removal) began to attract attention in the early 21st century as many were starting to show signs of ageing. An article published online in Australia’s Tourism News in 2010 entitled ‘Australia’s Big Things left to rot by state tourism’ opened with the question “Is it time to face the fact that Australia’s big things are a big tourism fail?” The article recalled that once big things “were the iconic moments of a trip around Australia” but now, with many falling into disrepair, characterised that:

When the icon goes bad, there’s often not much local councils or tourism bodies can do to save it. The big things cost a lot of money to maintain... Many are privately owned giving councils no control over the standard of their icon. Where they are owned by the public, many towns can not afford to keep up the maintenance without extra financial support. In a choice between fixing a 10 metre vegetable replica and fixing a pot-holed road, the road will always win. (Australia’s Tourism News, 2010)

Engaging with these perspectives, and complementing them with opinions voiced by members of the local community and local businesses, this article considers the manner in which the BP operates and interacts in the public sphere with a variety of other symbols of Ballina. The BP’s success in establishing itself as a high profile visual motif, and one that is often regarded as iconic of Ballina itself, derives, in large part, from its photogeneity. In the last two decades in particular, the use of social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram, blogs and YouTube by travellers to record the sights/sites encountered during their travels have given it particular prominence. User generated content of quirky and/or attractive features on these media outlets is far more frequent and socially ‘organic’ than locally-managed public relations campaigns and provides a visual discourse that operates outside of promotional strategies and, thereby, needs to be considered by council or tourism marketing bodies, either through engaging with such discourse or consciously seeking to produce alternative images. At a local level, the sculpture has attracted controversy and, in recent years, has been modified and relocated in a manner that has enhanced its prominence in Ballina’s streetscape and in social media. Through its active development and negotiation, the BP has become a popular cultural icon of the town, the (cooked) crustacean representing a locale, a livelihood tradition and a local culinary delicacy.

Developing the Ballina site

The BP was conceived by two property developers, Attila and Louis Moknay, through their company LA Developments, as another in the series of large roadside attractions reflecting local industries that they had commenced with the Big Merino at Goulburn and the Big Oyster at Taree. In order to ensure verisimilitude, the Moknays employed James Martin, a sculptor based at the University of South Australia, to design the giant tiger prawn. The eventual design was for a sculpture 30,000 times larger than a real prawn that was 9 metres tall and weighed 40 tons. LA Development’s planning application to mount the sculpture on a roadside retail block named Ballina Transit Centre was approved by Ballina Council in 1988 on the grounds that the BP would be useful in promoting the town despite both local opposition (with 163 public objections being lodged) and the advice of council staff that the scale and height would be out of character with the predominantly single-story residential area around it (Ballina Shire Advocate, 2009: online). One aspect that was not immediately apparent in the application, but which attracted local criticism when the business opened, was that patrons could climb inside the head and look out through its large perspex eyes. In daytimes this was a relatively unobtrusive exercise but after sunset the illuminated nature of the interior made the prawn’s eyes glow brightly and be visible when viewed from outside, a feature that not every local resident found appealing and that some found downright “creepy” (ABC, 1991). Despite such issues the BP became an accepted part of the urban and roadside landscape in the 1990s and 2000s until it — and the commercial block it graced — fell into disrepair and disuse in the early 2010s, being fenced off and covered in graffiti (Mr Agm65, 2012). This deterioration occurred at the same time as the completion of work on the bypass that would divert the Pacific Highway (route M1) away from the town (Figure 1) — where it ran directly past the BP. The opening of the bypass in November 2011 was correctly predicted to substantially reduce the volume of noisy freight traffic travelling through residential neighbourhoods but also to reduce the number of car travellers stopping for rest and refreshments. This placed the BP in a similar position to other bypassed roadside attractions raised by Cushing (2007) and Australian Tourism News (2010) (as discussed above). Keen to redevelop the site, the property’s (then) owner, businessman Santo Pennisi, applied to Ballina Council to dismantle and scrap the BP in 2009, unwittingly setting off a public battle about the BP’s future that was exacerbated by Ballina Council’s approval of the proposal and by the mayor, Philip Silver’s, reluctance to support its retention and his expressing a preference for “a small, stylish pelican in the centre of town, along the lines of the Little Mermaid in Copenhagen” as a replacement attraction (Moorton, 2009).

Local media responses to the prospect of the BP’s removal were prompt and creative. The Daily Examiner (serving the Clarence Valley area, to the south of Ballina) sought responses from its readers via a Facebook post as to whether the Clarence Valley should have a giant attraction and what that might be. Intervening in an unexpected manner, Yamba’s Chamber of Commerce president Bev Mansfield wrote a letter to the newspaper that identified her coastal town (located 105 kilometres south of Ballina) as the BP’s rightful “home” and declared:

I have always wanted to get it here - with much opposition of course and no money to do so - but on the headland… How wonderful it would look… Maybe it would bring luck to the trawler men… Who knows? (Stevens, 2012)

Fanning some local rivalry, the newspaper contacted Ballina Chamber of Commerce chair Peter Carmont who reaffirmed local support for maintaining the structure and dismissed the rival bid:

It is something that is an icon in Ballina and everyone who drives along the Pacific Highway through Ballina remembers the Big Prawn… To say that it should be moved to Yamba when its been at Ballina for decades... they should have dealt with that a long time ago. Ballina has always been the home of the Big Prawn and we intend it to stay that way and as a chamber we pushed for it to stay. (Stevens, 2012)

Rumours also spread that there were plans for it to be moved to the Gold Coast, 110 kilometres north of Ballina, in southern Queensland (Saunders 2017). Local relocations were also suggested, with Ballina councillor Sharon Caldwallader suggesting that it be installed as a water attraction in a location such Shore’s Bay (6 kilometres to the east) (Broadhead, 2009).

Influenced by a social media campaign that attracted over 10,000 supporters and the public advocacy for BP’s retention by media celebrities such as Channel 7 television presenter David Koch (Moorton, 2009), Pennisi did not follow through on his approval and the BP remained on the site while new owners were found. The attractiveness of the site, on a main road in a growing town, attracted the national Bunnings Hardware Group to purchase it (BP and all) in 2017 (Hutchison, 2014). In making the purchase, Bunnings’ managing director John Gillam acknowledged that the BP “is an icon that does provoke a lot of emotion…. we're not going to be the ones who knock it down." (Turnbull, 2011). Turning an obligation into an asset, Bunnings obtained Council approval to modify the structure and invested around $400,000 in completing the prawn’s tail, reinforcing and repainting its body and mounting it on a frame adjacent to the main road, on the entrance to the store’s car park (Figure 3). Bunnings’ general manager property Andrew Marks summarised his company’s intervention by declaring that, “from the beginning it was clear that the Big Prawn was iconic in the region and we have been delighted to provide it with a facelift" (Hutchison, 2014). The completion of the prawn’s body and its elevation above the ground changed it from being an accessible rooftop gimmick to being a free-standing statue visible from 360 degrees across a wider area than its previous location (Figure 2).

The rise in the public profile of and public support for the BP during its period of uncertainty in 2009–2012 led to a related local initiative that aimed to channel that support into a celebration of Ballina’s prawning history and the product itself. This took the form of an annual Prawn Festival, held for the first time in November 2013. Making the connection between the town’s fishing heritage and the event explicit, Nadia Eliott-Burgess from the Ballina Chamber of Commerce, stated: “we've got trawler families here that still risk their life day to day going out through the Ballina bar to go and bring in fresh seafood to distribute through the Northern Rivers and beyond” (Burin, 2013). This aspect was also acknowledged by blogger Red Nomad, who tied the perils of the prawning industry to both the BP the appeal of the coastal location:

After all, watching the Prawn Trawlers head down the Richmond River, across the churning waters of its treacherous Bar and out through its mouth to sea for a night of fishing is one of the joys of walking Ballina’s twin breakwalls. It’s even more exciting watching the trawlers return to cross the bar through a mountainous swell in seas so heavy I’ll never complain about the price of seafood again! (Red Nomad, 2017)

The annual Prawn Festival, held at Missingham Park, was aimed at families, featured food stalls, live entertainment and concluding fireworks and included an innovation in the form of a costumed prawn performer (Figure 44). Intentionally or not, the ‘walking prawn’ has distinct affinities to Japanese yuru-chara - invented anthropomorphised animal mascots for towns and cities that appear on online, on signs and as costumed performers at events (Suter, 2016). But while the walking prawn proved photogenic for visitors it did not subsequently become adopted as promotional character/motif for the town and, indeed, largely faded from public circulation5 after the festival was cancelled after 2017 due to declining numbers and the unreliable weather conditions common in late Spring.

Despite the abandonment of annual prawn festivals, recent Tripadvisor reviews suggest that it is still regarded as an eminently photogenic sight on road trips, averaging a 4/5 rating as an attraction, regularly attracting posts such as: “Good kitsch-value photo op for all things “big” in Australia! Can’t help but smile to see it. Easy to stop and get a quick photo of this seafood icon in Ballina” (Sonia, January 9 2022) and with posters assessing it favourably compared to other Australian roadside big things:

This prawn, unlike the Coffs big banana, the Caboolture big pineapple, the big Mango, the Dubbo big steer, and the pathetic Tweed/Kingscliffe big Avocado and even the Tamworth Big Guitar - is actually huge and an amazingly detailed work of metal art. Well worth the panoramic view of Bunnings just outside downtown Ballina. Go there. Ballina is a very very cool place - just don't tell any of the hipsters. (Alofoz, December 2 2020)

Negative comments have concerned the lack of interpretative signage, leaving visiting unfamiliar with the area with no idea as to why a giant prawn occurs there (e.g. Resign70, February 8 2020); the lack of any supporting attractions (e.g. Carolyn B, January 9 2020 & Jim J, January 6 2020); and the lack of a seafood sales outlet in the immediate proximity6 (Jewel M, November 30 2019). While the BP could undoubtedly be enhanced as a tourist attraction — rather than simply as a photo opportunity spot — that latter function continues to be inscribed in social media, thereby promoting the town and its seafood produce.

Alternative local symbols

While the BP has become a widely recognised icon of Ballina, especially for tourists, it exists in competition with a number of other symbols. Some of these attempt a broader representation of the town and its aquatic heritage. The shire’s coat of arms, adopted in 1977 (Figure 5a), for instance, emphasises its association with the sea by being flanked by seahorses, having a seaweed-like mantling around the shield, and a boat on top of the crown. The central shield has a ground of curving blue and gold bands, suggesting sunlight and water, and a central column that includes a lighthouse, a scallop and a prawn. The complexity of the image — with its use of traditional heraldic elements — has resulted in it being primarily used in internal council contexts with other symbols and logos, principally an elegantly stylised seahorse, being used in public, used over the last decade (Figure 5b).7

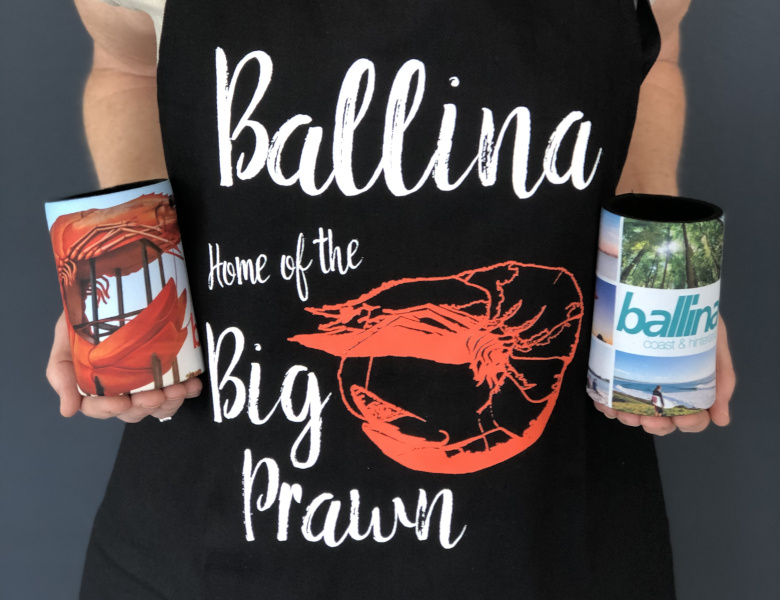

Despite the attractive aquatic imagery deployed in such signs, the prominence of the BP in Ballina’s urban landscape and its multiple reproductions in social media have led it to assume a de facto representative status for the town that has been perpetuated in forms such as tourist souvenirs (Figure 6 — and also see Broadhead, 2010) and short, locally published books about its history (Osborne, 1991, 2013). Research with Ballina residents undertaken in mid-2022 revealed a similar diversity of opinion about the merits of the sculpture to the views outlined above. Negative characterisations included adjectives such as “ugly” and creepy”, while more positive ones emphasised its unpretentious cheeriness and its function as a clear marker of the town — i.e. “when you look up at it you’ve got no doubt where you are, you can’t mistake it.”

Conclusion

There are several notable aspects to the history of the BP since its initial installation in the late 1980s regarding both the heritage of routes’ roadsides at time of significant infra-structural upgrading and of the development and maintenance of local symbols. Symbols originate in various contexts: through official designs and promotions; as a result of commercial developments; and/or through idiosyncracies of personal taste. The extent to which these symbols endure and become accepted by resident communities depends on a range of factors and there are, commonly, diverse opinions about them. Whatever their origins, they remain manipulable in terms of local identities and/or their competition against similar symbols and their material representations (e.g. the so-called “prawn wars” between Ballina and Exmouth [in Western Australia] over whose prawn is best — see unattributed, 2019). In terms of local identity, the BP’s representation of the local prawning industry clearly relates to one aspect of place and local history but does not represent the dominant industry in the area (healthcare and social assistance, which employ 16.6% of the local workforce8). As such, it more obviously promotes the fishing/seafood eating aspect of the area, which is supported by two busy seafood retail outlets, by three fishing equipment stores and various boat equipment and maintenance operations. In terms of the present form of the BP, it obviously has a strong link to the initial roadside attraction that supported it but its extraction from that context has shifted its function to that of an icon that only has a loose connection to the retail operation whose car park in sits within. But this also has the effect of freeing it from its commercial function and allowing it to float over its surrounds as a less determined marker of space. This recalls Barcan’s characterisation of big things more generally, that they “stand in metonymic relation to the region they represent; that is, they function as a part standing in for the whole [and] are markers that have themselves become sites” (1996: 31–32), even if the BP is now primarily glimpsed in passing, or briefly parked alongside in order to be photographed. In this way, the coastal site of Ballina, more broadly, is represented by the inscription of a singular aspect of its fishery that serves to evoke its seaside charms. What is also notable is the disconnect between the BP and the rising recognition of Indigenous heritage in the area in recent decades. While prawns were an element of pre-colonial Indigenous diets, there is nothing in the monumentality of a giant cooked prawn in a car park that evokes the older traditions of the area. Indeed, its massive amplification is more suggestive of the extractivist nature of contemporary fisheries rather than the small-scale marine harvesting traditionally undertaken by indigenous communities. Notably, with current pollution stresses on the Richmond River (Saunders, 2017; Cox, Oeding & Taffs, 2019), its estuary is less conducive to the maturation of immature prawns than it has been historically and the offshore prawn fishery will feel the effects of the related diminution in numbers in subsequent years. In this regard, the BP might stand for a marine “cornucopia” (Barcan, 1996: 1) that is rapidly slipping into history, rendering it as much an object of nostalgia as an indication of what might be available to those who visit the area under the thrall of the giant roadside crustacean.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Kevin Markwell for his comments on an earlier version of this article and to Christian Fleury for providing the map.

Endnotes

References

- ABC TV. 1991, December 8. What's it like being a neighbour of Australia's Big Prawn? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z7aQZznvMXY

- Australia’s Tourism News. 2010. Australia’s Big Things left to rot by state tourism. https://www.thetourismnews.com.au/featuredhomepage/694/

- Ballina Shire Council. 2016. Industry sector of employment. https://profile.id.com.au/ballina/industries

- Ballina Shire Council. 2019. Tourism and hospitality value. https://economy.id.com.au/ballina/tourism-value

- Barcan, R. 1996. Big things: consumer totemism and serial monumentality. LiNQ 23(2), pp. 31–39.

- Blonde Ambition. 2016. The Big Prawn. https://blondeambition.com.au/2016/04/02/the-big-prawn-ballina/

- Broadhead, G. 2009, September 30. Big Prawn Plan floated. Daily Telegraph. https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/lismore/big-prawn-plan-floated/news-story/7304db6c1ca5f7dcd3ecadf310d6d55c

- Broadhead, G. 2010, January 20. Hang on to Big Prawn souvenirs. Daily Telegraph. https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/lismore/hang-on-to-big-prawn-souvenirs/news-story/ae6ad5b0b36fab29ddaa8946ede6ff16

- Burin, 2013, November 15. Home of big prawn welcomes visitors for inaugural festival. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/local/photos/2013/11/15/3892043.htm

- Clarke, A. 2017, September 19. Australia’s ‘big problem’ — what to do with our ageing super-sized statues? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/australias-big-problem-what-to-do-with-our-ageing-super-sized-statues-83424

- Cox, B., Oeding, S. & Taffs, K. 2019. A comparison of macroinvertebrate-based indices for biological assessment of river health: A case example from the sub-tropical Richmond River Catchment in northeast New South Wales, Australia. Ecological Indicators 106, 105479.

- Cushing, N. 2007. The road behind us: The Pacific Highway, Sydney to Brisbane, as a heritage corridor, Historic Environment 20(1), pp. 21–25.

- Discover Ballina. 2020. Souvenirs. https://www.discoverballina.com.au/visit/our-region/souvenirs

- Fleury, C. and Hayward, P. (2021) Riverine Complexity: Islandness, socio-spatial perception and modification around the lower Richmond River (New South Wales, Australia). Island Studies Journal 16 (2), pp. 156–177.

- Genovese, P. 2006. Roadside Florida: The definitive guide to the kingdom of kitsch. Stackpole Books.

- Hollis, T. 1999. Dixie before Disney. University Press of Mississippi.

- Hutchinson, S. 2014, October 4. Bunnings investor catches Ballina’s Big Prawn. Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/property/commercial/bunnings-investor-catches-ballina-s-big-prawn-20141004-jlm1p

- Jambor, C. 2016, March 6. Ballina could soon have its own 'multi-day festival', Northern Star. https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/lismore/ballina-could-soon-have-its-own-multiday-festival/news-story/c17e5435275975cae95046c283ab51af

- Leiper, N. 1997. Big Success, Big Mistake, at Big Banana: Marketing Strategies in Road-Side Attractions and Theme Parks. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 6(3–4), pp. 103–121

- Markwell, K. & Cushing, N. 2010. Snake-bitten: Eric Worrell and the Australian Reptile Park. UNSW Press

- Mercer, Phil. 2017, June 20. Australia’s obsession with ‘big things’. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-39299855

- Moorton, T. 2009, August 13. Big Prawn gets raw deal. Daily Telegraph. https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/lismore/big-prawn-gets-raw-deal/news-story/0a86ef5fd998f7308032e6a040f4563c

- Mr Agm65. 2012. The decline and fall of the Big Prawn. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M3anFlRijrc

- Newscorp. 2009. Ballina's Big Prawn a raw point with townsfolk. Perth Now. https://www.perthnow.com.au/news/nsw/ballinas-big-prawn-a-raw-point-with-townsfolk-ng-e940b7f95de632ba73d9169f8bd69cf3

- Osbourne, R. 1991. Tessa and the Big Prawn. Self-published.

- Osbourne, R. 2013. The tail of the Big Prawn: how Ballina's icon was re-born. Self-published.

- Red Nomad. 2017. The Controversial Crustacean! Big Prawn Ballina, New South Wales. https://www.redzaustralia.com/2013/07/the-controversial-crustacean-big-prawn-ballina-new-south-wales/

- Saunders, M. 2017, October 11. Curious North Coast: Why is the Richmond River so polluted? ABC North Coast. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-10-11/curious-north-coast-richmond-river-pollution/9018602

- Saunders, M. 2017, November 2. Ballina's Big Prawn survives the chop to celebrate local industry. ABC North Coast. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-11-01/big-prawn-still-celebrates-ballina/9102600

- Stevens, R. 2012, September 11. Yamba's bid for Big Prawn: Yamba’s Chamber of Commerce president wants to see Ballina's iconic Big Prawn relocated to the town at the mouth of the Clarence River. Daily Telegraph/Examiner. https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/lismore/yambas-bid-for-big-prawn/news-story/6a995e88e53f2435407658654681a50c

- Stockwell, S., & Carlisle, B. 2003. Big Things: Larrikinism, Low Art and the Land. M/C Journal, 6(5). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2262

- Suter, J. 2016. Who is Hikonyan? The phenomenon of Japanese Yuri-Chara. Sociology Study 6(12), pp. 775–782.

- Tripadvisor (2022). Reviews Big Prawn. https://www.tripadvisor.com.au/Attraction_Review-g528913-d8115622-Reviews-Big_Prawn-Ballina_Ballina_Shire_New_South_Wales.html

- Turnbull, S. 2011, November 7. Long live the Big Prawn. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2011/11/07/3358009.htm

- Unattributed. 2019, February 1. Prawn wars: Who has the best big prawn? Daily Telegraph. https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/lismore/community/prawn-wars-who-has-the-best-big-prawn/news-story/1841d769f65223e9c158fb3cc90593c7

- Visit NSW. n.d. Goulborn: Big Merino. https://www.visitnsw.com/destinations/country-nsw/goulburn-area/goulburn/attractions/big-merino

- White, L. 2015, July 14. Father of Ballina prawn industry Charlie Heynatz passes away. Noosa News. https://www.noosanews.com.au/news/charlie-was-a-pioneer-of-the-ballina-fishing-indus/2704402/