Creating Islands in Film: The Interplay of Location, Mind and Cinema

Abstract

This article is a comparative study on the representation of islands in cinema and how film viewers make sense of islandscapes by activating cognitive processes and previous knowledge about islands and cinema. I focus on Bergman’s Summer with Monika (1952) and L. Wertmüller’s Swept Away (1974) in order to identify those cognitive processes in films from two different cinematic traditions and times. The concept of island is a domain that includes knowledge about islands, human experiences of islands and dynamic cognitive structures (see Lakoff and Johnson 1980). In this article I integrate those elements to a more comprehensive view of meaning making in cinema that includes several layers. At a cognitive level, image schematic representations can evoke standard metaphors such as island is container or island is support, but additional meanings such as island is paradise and freedom is islandscape emerge. At a discursive level, islands are often situated in the space of the Other versus the Self generally located in the mainland, and this ideological construct is related to a central tenet in the Western worldview: the opposition Nature/Human. Although these films dramatize possible biocentric alternative views such as reinhabitation (Snyder 2013), the dominant anthropocentric worldview is still favored.

Keywords

Island in Cinema, Conceptualization, Embodiment, Image Schemas, Discourse, Reinhabitation, Biocentrism versus Anthropocentrism

Introduction

World creation is a central goal of the mise-en-scène in film, and, as witnesses of the cinema’s fictional environments, the viewers immerse in these worlds via perceptual and cognitive processes used to make sense of reality and, at the same time, by accessing sociocultural and filmic knowledge. The goal of this paper is to analyze two case studies of films set in islands in order to see how those processes participate in the representation of islands in cinema. Also, particular ideological frameworks and generic conventions need to be situated in ecological discourses of the failure to overcome the dichotomic relation between nature and human. I compare two radically different films in terms of location and style. I. Bergman’s (1953) Summer with Monika (Sommaren med Monika) is a black and white film set in some islands of the Stockholm archipelago in Sweden. L. Wertmüller’s, (1974) Swept Away by an Unusual Destiny in the Blue Sea of August (Travolti da un insolito destino nell'azzurro mare d'agosto usually Swept Away) is set in a fictional deserted island in the Italian Mediterranean.

Despite being very different, both films are situated within the genre of the summer film. Summer with Monika is a coming of age film. Both interact with the cultural model of island as a paradise. For instance, Swept Away can be connected to films like Kleiser’s The Blue Lagoon (1980) as they follow the same blueprint: two people who are stranded in an island and learn to survive. Swept Away transfers this story to two middle-aged people who represent opposite poles. Summer with Monika follows the conventions of the coming of age genre found in Swedish cinema of the 50s. In this case, it is set against the desires and dreams of a couple who long to be like those characters they have watched in the movies.

The concept island (represented in small capitals as a conceptual domain rather than a matter of language as it is standard in Cognitive Linguistics, see Lakoff and Johnson 1980) is a construct that involves not only how an island is conceived but also how we experience it. Previous research on how islands are conceptualized have focused on how the relative isolation and distance from the mainland determines their identity and how the islands are related to each other in what Hayward (2012) denominates an aquapelago: a series of islands connected by water rather than separated by it. Omondiagbe et al. (2021) have recently shown how imaginaries of islands misconstrue how islanders perceive their own worldview and how two competing conceptualizations of island are at play. On the one hand, an island’s identity is paradigmatically isolated and singular (see Ronström 2011, 2013, 2021). On the other, islands are spaces that are related and engaged with the world at large and in relation to the mainland (Hay, 2006; Pugh 2018).

An island in general, but particularly in creative works such as a film, is a concept that concrete sensorimotor experiences help us understand. It can have multiple conceptualizations depending on how it is represented on the screen. As Ronström (2021: 271) states “‘the island’ is constituted by the constant and wayward sliding between the physical places we call islands, and all the figures of thought that we attach to such places.” Therefore, I believe it is necessary to relate the way we conceive an island to our own physical experience of them as geographic entities in order to understand how we make sense of their representation in films or in culture at large. An island is a dynamic and complex reality of “mobile, multiple and interconnected relational forms” (Pugh 2018:94).

Summer with Monika is Bergman’s eleventh film and was shot in two main locations: Riddarfjärden, what now is Stadsholmen, Stockholm’s Old Town, and two islands of Stockholm’s archipelago, Ornö and Utö1. Bergman’s Summer Interlude (Sommarlek, 1951) was also set in the islands which was and still is a common second home destination (see Marjavaara 2007). In his youth, Bergman and his family spent their summer vacations in one of the islands of the Stockholm archipelago as he explains in his memoirs The Magic Lantern (Bergman 1987). He gives all kinds of details about his experiences during his teenage years and a particularly relevant story is that of Anna Lindberg, a classmate of his with whom he had a long-term relationship. As Steene says, Summer with Monika can be situated within “the Swedish summer film, which had developed a cluster of visual motifs with placid lakes, glittering waterways, birch trees with filtering sunlight islets in the archipelago or hills and meadows reflected against a sky of obligatory cumulus clouds” (Steene 2011: 12).

Wertmüller’s Swept Away is her ninth film and it was filmed in diverse locations on the island of Sardinia. As in other of her films like Love and Anarchy (Film d'amore e d'anarchia, ovvero: stamattina alle 10, in via dei Fiori, nella nota casa di tolleranza 1973), Wertmüller focuses on the conflicts between city and countryside and also North and South Italy (about the so-called “the Southern Question” in Italian cinema see Verdicchio 2015). In this film, a group of rich intellectuals from Milan travel on a luxury cruise in the Mediterranean. In the first eighteen minutes of the film the wealthy Milanese couples discuss politics and, among them, Raffaella Pavone Lanzetti (Mariangela Melato) is particularly aggressive against what she considers to be the hypocrisy of her communist friends while she talks down to the crew formed by poor Southern Italian fishermen. At some point, she decides to go on an excursion with one of those sailors: Gennarino Carunchio (Giancarlo Giannini) in a small zodiac boat and they get lost. After some days, they reach a deserted island and, on this island, Gennarino becomes insulting and violent towards Raffaella and this abuse turns into an abusive sexual relationship.

By comparing both films, I identify common experiences associated to islands and island life and how films can transform those experiences creatively through the narrative and artistic manipulation of those spaces. These experiences include: the experience of a journey to an island; the experience of being on an island versus in an island and their underlying image schemas; the experience of water and land and their interaction; the dichotomy island versus mainland and island as singular ecosystem; and finally, the human/nature relationship. According to Branigan (2006: 100), “[w]atching a film requires a spectator to make judgements moment by moment and to actively construct models of locale and agency using folk knowledge, expectations, wishes, inferences, heuristics, scripts, metaphors, social schemata, and numerous forms of memory” (Branigan 2006: 100).

In cinema an island is part of what is called in the wide sense of the word, the mise-en-scène. The mise-en-scène includes a great number of constituents of a film such as lighting, costume, set design, etc. As Lefebvre (2006) shows, as part of the mise-en-scène, the landscape is not just a backdrop or ancillary to the action. In its representation, filmmakers use a diversity of camerawork and montage techniques. Since very early in its history, cinematic landscape was a realistic setting for the representation of news, a background suitable to the film action while at the same time it could incorporate the characters’ emotions. Technical innovations are connected to shooting in location. For instance, according to Sitney (1993, 107—8), long shots and aerial cinematography were created in order to capture panoramic shots. Flaherty chose a particular film stock to capture the landscape of Alaska in Nanook of the North (see Sitney 1993, 109; Flaherty 1998 [1922]). The invention of the widescreen and zoom lenses allowed for filmmakers such as Kubrick to fluctuate “from a close-up detail to an extremely long shot, often as the punctuation for the beginning of a scene” as Sitney (1993: 111) says. Sitney also identifies how landscape can represent “oppositional strategies” (1993:116). For instance, he finds those meaningful contrasts in the vertical structures of the mountains versus the flat lands in Monument Valley in J. Ford’s Westerns or the vertical Sicilian cliffs at the beginning of Rossellini’s Paisà (1946) versus the flat marshes of the Po.

It seems unavoidable that when representing a physical space in a film, different cinematographic techniques elicit particular emotional responses in the viewers’ minds. In the context of the embodiment theory, watching a film involves the affordances provided by the images, the other meanings and sensorial experiences granted by the voices, music and soundtrack and the way we structure our perception which is determined by image schemas. Image schemas are recurring patterns resulting from the interaction of the body and the mind and participate in the way people process linguistic and nonlinguistic information (Gibbs and Colston 1995 and 2008). They determine the distribution of the visual elements on the space of the screen. Coëgnarts and Kravanja (2014) have also focused on how screen representation of space in John Ford’s films follows the pattern of a container, that is to say, a basic mental structure of a space surrounded by a boundary. According to Lakoff (2012: 775), cognitive linguistics has shown that abstract concepts are embodied, that is to say, they “draw upon physical experiences.” The embodied cognition thesis informs that concepts can be built on physical experiences of our bodies in the world. Cognitive structures underlying the spatial design of a film play a major role in how we can make sense of the space as it is represented on the screen. Viewers’ dynamic perceptual system integrates the spatial dimension of the image, how we perceive reality and previous knowledge about those images.

The relation between location, storyline and characters can endow the film with verisimilitude as it integrates the local weather and geographic particularities and those features follow viewers’ expectations and stereotypes about both weather and geography. At the same time, islandscapes in cinema can determine the characters’ actions and those actions can be major factors in how the storyline develops. To great extent, cinema supports views of the world by “envisioning the physical interrelatedness of body and habitat” (Heise 2006: 511). Ideas such as “reinhabitation” (see e.g. Snyder 2013) or “bioregionalism” (see Taylor 2000) encapsulate a biocentric view of the world that emphasizes the importance the connection of human beings to their local dwelling and their resources rather than an anthropocentric view.

The conflict between nature and human beings and their connection to the land and identity, property or migration are some of the issues that motivate the dramatic development in cinema. Representations of islandscapes in both films are connected to universal human experiences of islands and underlying views of the world. Viewers can access due to having at their disposal common cognitive processes, ideological frameworks and background knowledge. Each of these elements work at different levels on the viewers’ minds and bodies.

Evoking image schemas: container and support schemas

One experience frequently shown in films located on an island is the explicit representation of arrival and departure from the island. This topic is partly motivated by the role journeys have in film plots. At the same time focusing on the surrounding of a mass of water can evoke on the viewers the isolation and remoteness of islands and islands, as spaces clearly delimitated by a boundary, are conceptualized as a container image schema. Such representations of an island can be achieved by using different cinematographic techniques such as the long shot, an aerial shot or a repetitive image of the coastline. Often, it is explicitly mentioned that the film is set on an island. For instance, in the opening scene of Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (2020 [1948]), we see an aerial view of Manhattan and its coastline while we hear the voice of a narrator who insists in the fact that Manhattan is an island (and a city).

In general, traveling is a common event and many films occur on a train, a boat or a car as in a road movie (see for instance Alfred Hitchcock The Lady Vanishes, 1938; Wes Anderson Darjeeling Limited, 2007; Lars von Trier Europa, 1991; James Cameron Titanic, 1997), but travelling to an island is concomitant to the fact that an island is generally conceived as being at some distance from the mainland (see Hong 2018 on near-shore islands). This separation is an important element in how islands are conceived.

In their remoteness and isolation islands are often depicted as a place difficult to reach or to leave. A Summer with Monika is set in the island of Stockholm’s old neighborhood at the beginning. The city harbor is shown before the title sequences as the sun is rising (0:00:00—0:01:20 see e.g. snapshots in Figure 1) and the early scenes are located in dilapidated neighborhoods of Old Stockholm. At Monika’s urging, Harry agrees to flee from poverty and social pressure, they take Harry’s father’s boat and travel through the channels of the Stockholm archipelago until they arrive at what seems to be an outer island of this archipelago. The shots in this journey are either point of view (POV) shots of the coast, the bridges or long shots of the boat and its passengers in a calm and clear day.

In Swept Away, Gennarino takes Raffaella on an excursion no one else wants to go on and they get lost. At sea, long shots combine with mid-shots and close-ups and contribute to the sense of being lost in the middle of the sea. The boat seems to wander back and forth. The sky changes from bright midday sun to setting sun, cloudy to clear and bright midday. This feeling of being lost at sea simulates the experience of disorientation as one navigates the sea without any reference to a land marker. As they reach the island shore, Raffaella and Gennarino’s boat sinks. This is a major factor for the plot since it gives the characters few options to explore beyond the coastline and find other islands close by. As they reach the island, the same sense of lack of direction and being lost at sea is represented by a series of quick cuts between long shots and close-ups. In some cases, the shots lack continuity. Gennarino’s and Raffaella’s first goal is to find signs of life. By climbing onto the top of the mountain and walking around different areas of the island, they try to find out whether the island is inhabited or not. In this early exploration of the island we already can see that this island has a great diversity of habitats and seascapes.

Monika and Harry arrive to the island for the first time and anchor against a big boulder in a sunny day when the sea is very calm in Summer with Monika (0:39:00). Approximately sixty-one minutes of the film are located in the island and most of this time the scenes are set on the coast. They live in their boat and even when both move apparently inland the camera focuses on ponds and other types of water. On the island, the dialogue is kept to a minimum and both characters are mostly shown doing daily activities such as singing, dancing, grooming themselves, preparing food, walking along the coast and looking at the landscape. The soundtrack is created by animal calls, wind, thunderstorms or waves crashing against the boulders or the boat. Long-shots of the calm seascapes are related to displays of emotions such as happiness and love or of disinhibition and freedom.

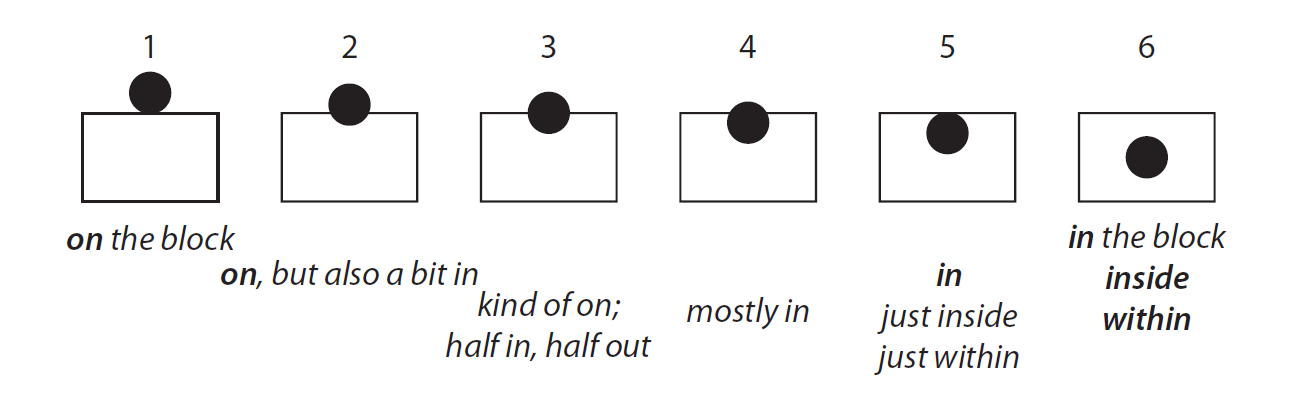

Travelling to an island frames the concept of island as a container and the sea or the coast can be considered a fluctuating boundary of the land the travelers reach (see below about this topic). According to Ronström (2011), islands can be conceived as a support image schema when using the preposition “on” as in on the island or as a container when using the preposition “in” as it is used when referring to islands as political entities (e.g. in Cuba). Further analysis of the polysemic nature of prepositions have shown how “prepositions provide the primary system for describing spatial relations, how we conceive the spatial dimensions of the reality they connect” according to Tyler, Mueller & Ho (2011: 184). Therefore, in can be said to encapsulate the relationship of an item in relation to its location as being in a container while the preposition on can represent among other meanings a surface that supports an item as the image schema support (the book is on the table) or a force that controls an item as in the constraint image schema (the dog goes on the leash see Johnson 1987 and Beitel, Gibbs & Sanders 2001). Some geographical spaces in which on is the preferable preposition are “they are on a beach, “they were found on a mountain,” “London is on the River Thames,” “the clock is on the wall,” “the fly is on the ceiling,” “there is no life on that planet,” “we live on Earth,” “they travel on a train.” This distinction is functional in English, Italian (which also prefers the preposition su in sull’isola) and other languages.

While in language it is possible to distinguished between being on an island (support image schema) and being in Corsica (container), in cinema, both image schemas can be activated in the way the islands appear via camerawork and framing. Island is a container can be understood as viewers identify a spatial reality as an entity surrounded by sea while moving through the island involves the experience of entering into a space. The container image schema is normally evoked by the search for closure through the “Gestalt completion” act. That is to say, we do not need to see the container as a whole, but we can complete it by adding the boundaries suggested by the experience of being within a space (see Hottenroth 1993: 193, 208). The transition from support to container is to great extent natural as both schematic structures are, according to Lindstromberg (2010:720), on a continuum as experiences of an item on a surface that moves into a boundary and it is illustrated in Figure 2 (borrowed from Lindstromberg 2010:720, figure 4.1)

In Summer with Monika the island blends landscapes and seascapes by using longshots where the characters appear immersed in seascape or the focus is on the seascapes. The only moment in the film where the protagonists move towards the interior of the island is the sequence when, dying from hunger, Monika steals a roast beef (see below). The sea in Swept Away is shown to be a space difficult to navigate and, consequently, it is experienced as a boundary since they lack the means to leave the island. In this film, some liminal spaces of water/land interaction are highlighted as some scenes are located on the dunes and the beaches of the island (see below) and contribute to the conceptualization of an island as a composite of sea and land. The continuity sea/land evokes this transient experience of being on an island as a continuous space of land and sea.

Therefore, as container, an island seems to be paradigmatic representation of a piece of land separated from another piece of land. This view of an island is metaphorically productive when referring to a person as isolated or not connected to other people or spaces. In cinema, the dynamics of image schematic structures allows the viewers to engage in the transfer from being in the ample space of sea/land intersection that is brought about by focusing on the connection between both while some images evoke the boundary as it is represented either by the coastline or the sea.

Islandscapes

Water defines the physical limits of an island and it is therefore the first boundary. It can be shown to be uncharted and often dangerous to human life. The Baltic sea in Summer with Monika appears calm and easy to navigate but for most of the film it appears as changeable, stormy, cold and with big waves and dangerous, especially when Monika and Harry return to Stockholm as they are also running out of fuel. Gennarino and Raffaella travel in a zodiac in the middle of the sea, and we have seen how easy is to lose one’s bearings while their lives were at risk due to the lack of water and food. After they see the island, the boat sinks and they reach a rocky area of the island by foot.

Although the sea is stereotypically conceived as a dangerous space or an inhospitable boundary, in Summer with Monika the island and the sea do not appear completely isolated. This span of water is beautiful although quite uninviting and the characters do not generally swim or bathe as it is probably too cold. It is also a space used to move from one place to another. The characters navigate from island to island in the Stockholm archipelago. The duality of isolation while at the same being part of a community of other islands is also conducive to understand other features associated to islands and their inhabitants. This film enacts the concept of aquapelago as the sea can be conceived at the same time as a barrier or a waterway (Hayward 2012). In fact, moving from island to island becomes a regular situation in Bergman’s movies. After he settled in the Fårö island in 1962, most of his films were located there. For instance, in his 1968 film Shame (Skammen), the characters travel via ferry from the island to the main island (Bergman 1968). This connection between islands contrasts with the ending of Shame in which the main characters try to escape the island by boarding a motor boat.

Another geographical space is the coast. The coast is one of the main natural features of the islandscape. As a space delimited by the connection between sea and land, it is essentially a fuzzy boundary. The natural islandscape in Summer with Monika is mostly rocky with some prairies with low brush and trees, but it also lets the viewers enjoy the wide and minimal spaces of the calm sea generally shown in wide long shots, the rough waves breaking against the rocks, the young bodies of the actors (especially Monika) or their progressive sense of despair as they run out of supplies and it is getting colder. In this minimalistic landscape, Bergman stresses the importance of the sky, the waves, the rocks and the water. Transitions between different scenes focus on the reflection of light on water and the pattern they create. For instance, in 0:37:50 the light reflected on water creates patterns on the wall of the boat cabin where Monika and Harry sleep. In 0:39:00 Monika washes up in the sea water. In 0:41:30, the camera focuses on the sandy bottom of the water. In 0:41:45 they walk inland and she stares at her reflection in an inland lake. In 0:41:50 they run on the big boulders of the coastline and Harry throws a rock in the water and the camera pauses on the ripples and reflections of the sun.

In Swept Away, the scenes are set in a diversity of coastal environments: sharp reef areas where they first reach the islands, rocky coastline, long beaches with white sand, dunes with plants, sand banks, and small coves. The rocky coast appears frequently as a place for fishing, preparing food, doing the laundry or sunbathing. At the same time, in those spaces Raffaella's submission process begins. We witness how Gennarino imposes himself on Raffaella due to his skills and knowledge of how to fish or hunt. In these circumstances, he starts a process of repression that Raffaella progressively accepts and comes to internalize as a love relationship.

A key sequence in the process of Raffaella’s submission is the sequence that starts at 01:05:00 and ends at 01:13:00. Both protagonists are in a rocky cove where they fish, cook and eat and at some point, he starts making sexual comments about Raffaella. She feels threatened and starts to run away. The camera follows her as she traverses a small inland lake or river, the beach, large white dunes with beach grass, bushes and trees while Gennarino hits her trying to stop her and Raffaella defends herself. When he finally stops her by laying on top of her, he says that he is not going to molest her because he wants her to fall in love with him. After a quick cut, in the following transition scene (1:13:00—1:13:56), Raffaella sits on the rocky coast both silent and motionless contemplating the waves hitting the boulders (Figure 3). In this scene, the coast is first shown covered with dead algae forming lumps or remains of Mediterranean tape weed (Posidonia oceanica) floating in the water or accumulated on the rocks. As the camera zooms out, the viewers can see those rocks with Posidonia and, in the foreground, Raffaella, sitting holding her knees with her arms. The camera zooms out, focuses on the sea and takes a close-up of the algae-filled water gently lapping the shoreline. With a quick cut, we go to a close-up of Raffaella's face and then to a subjective shot of the sea with Posidonia.

The uninhabited island Wertmüller created has multiple ecosystems of water and land. The habitats are rocky coasts but also sandy beaches in which scenes of violence and sex are set. After the scene just described, Raffaella and Gennarino engage in a long sexual encounter. This sequence starts in the dunes close to the beach at dusk (1:17:00). It continues through the night by the light of a fire. Both the use of the camera, the light and the dialogues follow patterns similar to the stereotypes of romantic love. At the same time, Gennarino does not stop attacking her and demanding her complete submission while the scene moves from the inland dunes to some dunes with views of the sea. In an act of narrative synthesis, in 1:21:00 the camera focuses on both characters lying on the sand dune and, suddenly, in a quick cut, the sea surrounds them and a long shot shows both kissing in the same position in a small cove. Some of the shots in this scene can remind us of the beach scene between Milton Warden (Burt Lancaster) and Karen Holmes (Deborah Kerr), in the Fred Zimmerman film From Here to Eternity (1953). After a quick cut, the next transition scene shows rocks in the middle of the sea at dawn.

In the following scenes Gennarino appears to be infatuated and controls his violence while Raffaella appears to have fallen in love with him. The last love scene occurs again at night on one of those dunes by the sea as both lay by the bonfire (1:31:23). Raffaella seems to have surrendered to Gennarino. Dunes and sand are usually situated in the field of sexuality and eroticism with direct references to other works such as the one mentioned above or to stereotypical scenes of sexuality and eroticism such as the love scene by the bonfire I have just described, or to a couple of scenes in which they stand embracing beside a stormy sea, or later sitting on a dune illuminated by a late-afternoon sun, also joined in an embrace (1:35:00 and 1:36:20).

The islands in these films are endowed with two features: the continuity of water and land and the diversity of ecosystems in a self-contained space. As the filmmakers highlight those features through the use of camerawork, the locations of some particular scenes can provoke additional meanings and, as I show in the next section, the concepts of freedom or paradise typically emerge in those films.

Island as a singular ecosystem: Mainland versus island

As it has often shown (e.g. Arcimaviciene and Baglama, 2018), ideology establishes narratives around dichotomies which define the Self as the Center: powerful, righteous, normative and rational while the Other is all the Self is not: weak, unlawful, exotic and irrational. This opposition has multiple functions, but besides the creation of drama between two opposite views or characters embodying those views, the binary opposition determines the discourse in hegemonic ideologies that identifies the “self” or the “us” against the “them” or “the other.” In consonance with its prototypical conceptualization of island as container and their paradigmatic isolation, islands often have been found to have a particular topography, flora or fauna. Its remoteness and distance caused the endemic nature of some of its flora and fauna (see McQuaid and Greig, 2007 on how changes in this separation could have an influence in life in the island).

This dichotomy is established in the early part of the film and, in the case of Summer with Monika, is the main reason for Monika and Harry to go to the island. As mentioned above, the first thirty-four minutes of Summer with Monika are located in a neighborhood that today is called Stockholm Old Town (Gamla Stan). The cinematography in this part of the film tends to be at a lower angle and a stationary camera. These choices visually represent the oppressive world that motivate the two main characters to leave the city and find an alternative world. In contrast, the camerawork changes completely as the characters travel and then arrive at the island. Bergman uses wide shots of land- and seascapes, long takes that include the characters within the surrounding natural space. As the camerawork highlights the sense of openness of the island and the sea, Monika and Harry express the desire to be like those romantic outcasts in the films they have seen earlier in the film. They are forbidden lovers in a romantic film, Indians in a Western, outlaws. Going to an island is therefore, a logical place to fulfill those dreams as islands are locations for those escapist films (see also Hubner 2007 about the role of cinema in this film). This is explicitly expressed in the dialogue between Monika and Harry in 1:08:20.

Bergman’s camera choice also creates a view of an island as close to nature. Although he favors focusing on the actors and their facial expressions, in this film the camera focuses on transitions of long shots of the rocky shore, meadows, small lakes, trees, birds, waves and plants next to the water, as mentioned above. Monika and Harry are unable to find resources among the harsh conditions of the Baltic islands although they are in a populated area which at that time of the year probably was busy with city people in their summer residences. In this case, the Self is presented as being the industrial city with its abusive treatment of human beings and its poverty while the Other is the couple of outcasts in the island.

This dichotomy Self/Other is first located in the mainland/island opposition, but as the film progresses we can experience how the connection between humans and nature both protagonists experience in the island reflects the conflicts found in the mainland. Perhaps the scene that represents this emmeshing of realities is the act of violence that started while Monika is teaching Harry how to dance. A man climbs onto their boat, throws some of their belongings overboard randomly and sets a fire on the boat. The fight that ensues is quite violent and Monika is close to killing the anonymous aggressor until Harry stops her. The representation of violence transforms what seemed to be until this moment an idyllic world into a reality closer to the world they lived in Stockholm. In the film Shame (Skammen, 1968) Bergmann also represents acts of random violence in what seems to be a meaningless civil war while the sensitive and apparently harmless Jan Rosenberg (Max von Sydow) becomes a ruthless killer.

The first part of Swept Away is located in the environment of a luxury yacht as mentioned above. This part of the film sets up several aspects of the remainder of the film: the sexual tension as the women sunbathe topless on the ship’s deck; the social and political tension: the couples are extremely liberal and discuss political matters from this point of view except Raffaella who is conservative and mostly criticizes the other passengers for their hypocrisy. The Self-Other dichotomy in the first part of the film is reversed during their stay in the island. Thanks to Gennarino’s knowhow and also the abundance of food, they can survive and, this leads to a change in the dichotomy from one of economic power to one of opposition of male versus female.

Nature versus culture

The metaphor island as paradise can be motivated by the distance, remoteness and particular environmental features of an island. In those spaces of freedom from social constraints, the linkage to the natural world is seen as a way to overcome restrictions and oppressions developed by society. The characters in both films enter a natural world represented as being beyond social constraints. Islandscapes in these films are tied to the particularities of their geography, topography, their flora or fauna. As mentioned above, these features can also be deemed as exotic, unusual, and unique to the island.

Among the fauna in Summer with Monika, seagulls are often seen or heard. In one of the first scenes in the island (0:41:40), the camera focuses on a close-up of Monika’s face which appears on screen from the left side while Harry is walking on the background of rocks and puddles and she shouts his name. This image is followed with a quick cut to an image of a seagull flying that appears briefly on screen. This is perhaps the clearest instance in which Monika is related to an animal and can be an audiovisual representation of the metaphor monika is seagull (about this kind of metaphors see Rohdin 2009).

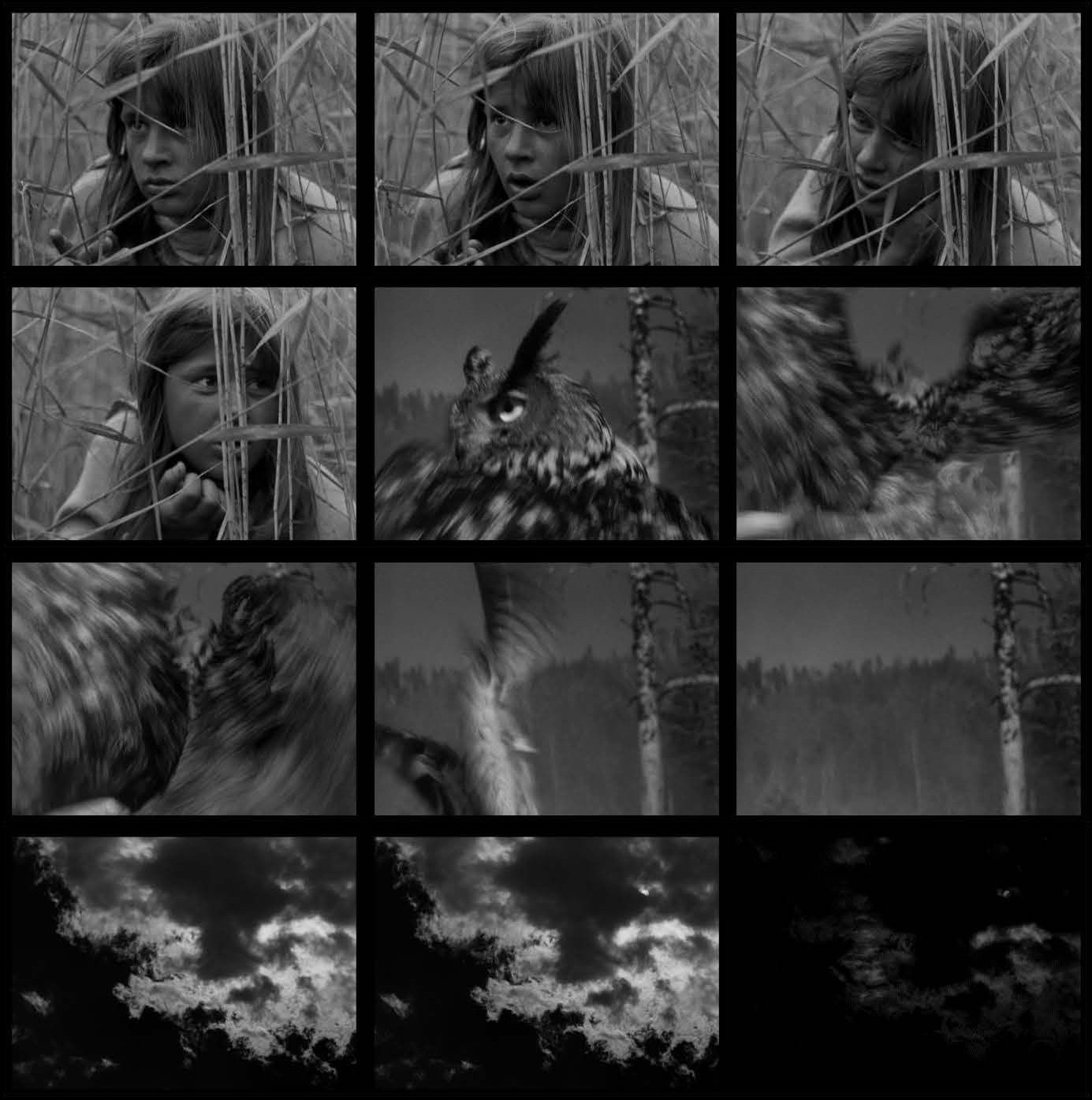

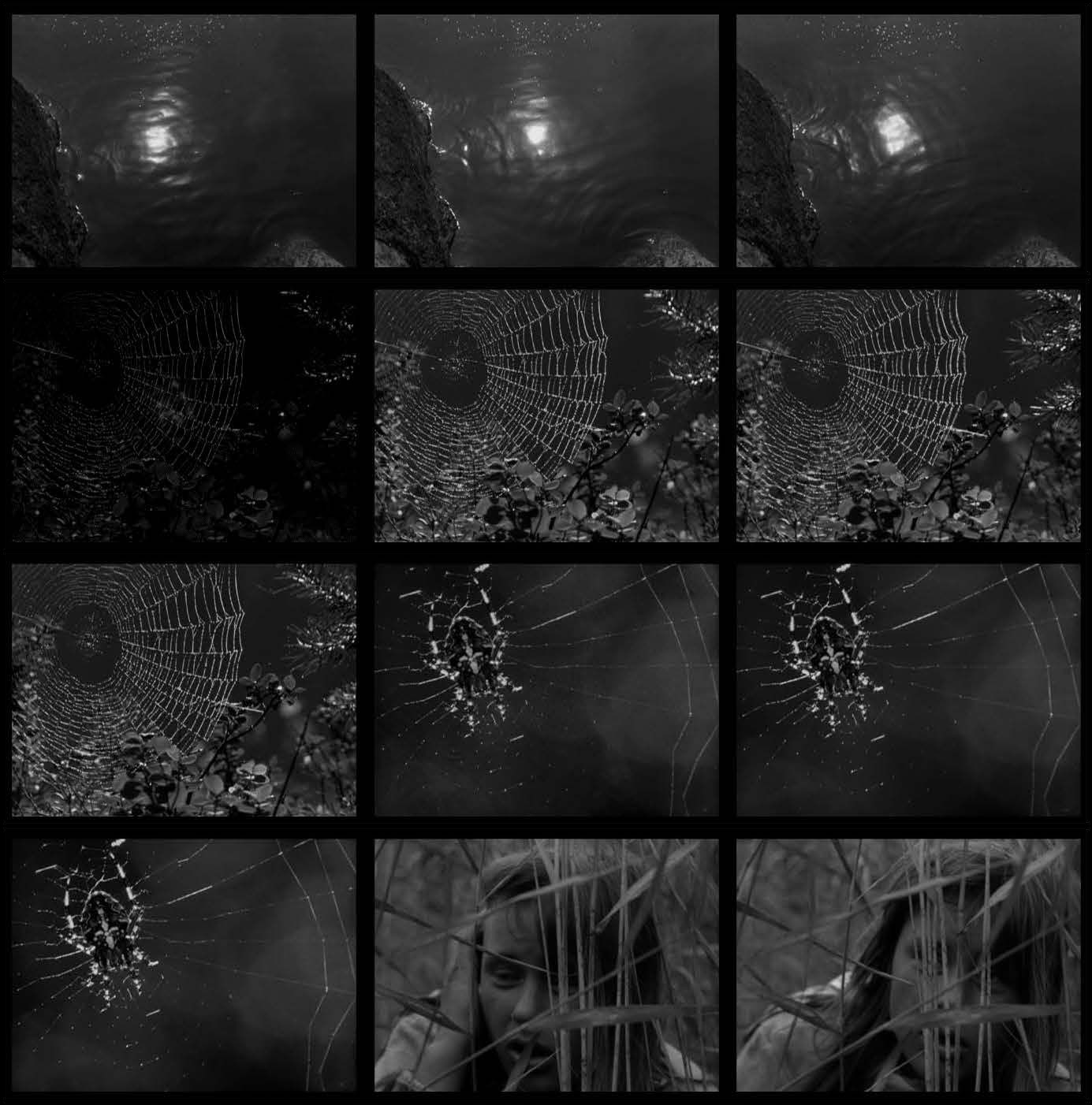

The next sequence in which we see Monika represented with somehow animalistic traits is in one of the last scenes set in the island (1:03:41—1:04:49). As food gets scarce and Monika feels her pregnancy more acutely, she decides they need more substance in their diet and so goes to steal some milk from a farm. After being caught by the owners of the house, she manages to escape and she runs away with a piece of roast meat. In this scene she eats with her hands and crawls or moves low in order not to be caught while she is trying to find Harry. She finally hides in a field of reeds (1:03:41) and, as we can see in the snapshots of this scene in Figure 4, she crouches among the reeds and contemplates with amazement the world around her. In a series of POV inserts we see the back of an owl that turns around and takes flight, a cloud, the moving reflection of the sun in a water puddle, a close-up of a spiderweb and an extreme closeup of the spider in the middle of the web. The images are similar to those in a nature documentary and we can share Monika’s sense of awe. She finally finds Harry and they leave the island (1:05:48). Her dirty appearance, her crawling and eating with her hands, how she stares at the owl, the reeds, and the spider in a spiderweb culminates one of the main story threads of the film: escaping social conventions leads her to a closer relation to nature (see Figures 4, 5 and 6 for snapshots of these scenes).

In Swept Away the relation between human and nature is also connected to the fact that the characters need to survive on a deserted island. Gennarino is seen fishing, holding a lobster, hunting a rabbit, taking an egg from a nest. In this space, both characters are able to survive, but parallel to this capacity to adapt is the transformation of power relations between the two characters.

Return to society

The last act of Summer with Monika starts twenty-six minutes before the end (01:11:00) and Swept Away’s last act starts sixteen minutes before the end when they are rescued by a boat (01:38:25). These last acts narrate the events that happen after leaving the island. If we situate these events as part of the Paradise metaphor, the stories’ return to reality is conflictive for all the characters. Monika and Harry have a baby and attempt to create a new life as a married couple while Harry becomes a regular family provider. Already while they were in the island it seems obvious at some point that for Harry it was imperative to return to society and to become a productive member of society in contrast with Monika’s search for individual freedom and self-affirmation.

In Swept Away, leaving the island and going back to reality is a return to the socio-cultural structures that were manifest in the boat. Raffaella goes back to her husband but she is transformed. Her seriousness and unemotional look contrasts with the loquaciousness and self-assurance she displayed at the beginning. Gennarino, for his part, suddenly realizes the social and cultural distance between both and goes back to his wife.

Conclusion: Islands in the dynamics of cinematic discourse

In sum, the environments created in these films can have several functions. First, it can be an important motivating factor for the characters’ behaviors. Therefore, slight changes in the environment and the relationship of the characters with it can justify their actions. Viewers can perceive such changes as part of how the world works and to great extent they can raise their empathy towards the characters. Changes in the environment adds another layer to our understanding of the plot development. As the characters’ actions are motivated by external factors, the narrative can progress in a more natural form without resorting to other devices such as dialogue, use of other characters or techniques such as flashbacks, inserts or voice-over.

As we have seen for instance in the case of Bergman particular shots and editing have implicit meanings. For instance, the scenes in the city communicate visually the oppressive lives of Monika and Harry in Stockholm. The style changes radically with the arrival to the island and the world created emphasizes the wide horizon, the shapes of the rocks, etc. Both have an expressive and aesthetic purpose and viewers enjoy the beauty of the shore, the waves, the clear waters of the sea, etc. One of the roles of the dramatic meaning of the mise-en-scène is to give the viewers access to the underlying emotional state or thoughts of the characters. Identifying the meaning those islandscapes have and the emotions they represent can be difficult to express in linguistic terms. From a dynamic perspective, a cluster of meanings emerges out of the interaction in the way the mise-en-scène is represented via the use of cinematographic techniques and its role within the plot, the characterization and intertextual references to film and art. Viewers’ own experience and emotional state interact with any of the components of the dynamics of this discourse.

Creating a world engages several layers of the viewers’ mind and their interaction with what is presented on the screen. In this paper, I have shown how our conception of island is based on how space is experienced and conceived by our minds. On the one hand, it can be a container, and, on the other, a support. As a support an island holds entities and this view of an island connects land to its surrounding waterscape. As a container, it can be seen as a space separated from other ones and typically surrounded by a boundary either defined by a body of water or by a coastline. Some of the features of the container schema highlight two additional features of an island: isolation and remoteness which have further implications. Islands are a composite of two entities: the dynamic and fluid world of water with no clear boundaries and the land. Technically speaking the water-land composite can be achieved by focusing on the changeable borders of the beach and also by showing a continuity between sea and land using long wide shots and sometimes from a high angle. Therefore, the sea or the ocean can change meaning as it can either as a way to communicate lands or a barrier that impedes transportation. In this case, other metaphorical meanings associated to seeing sea as boundary or sea as path can emerge such as sea as freedom.

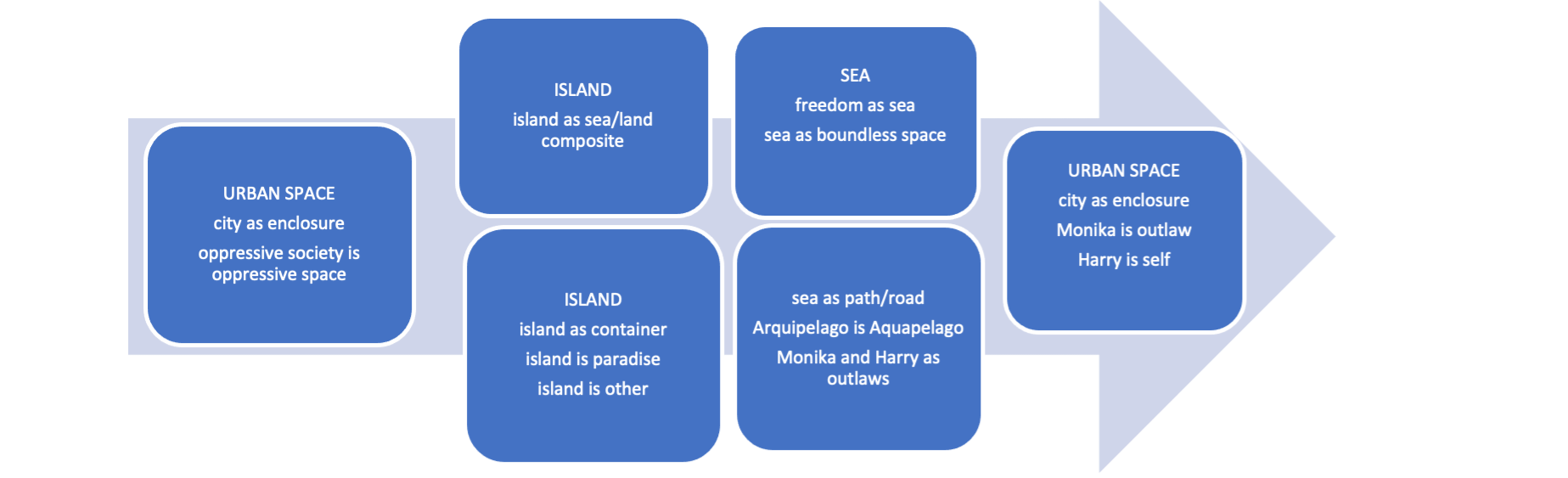

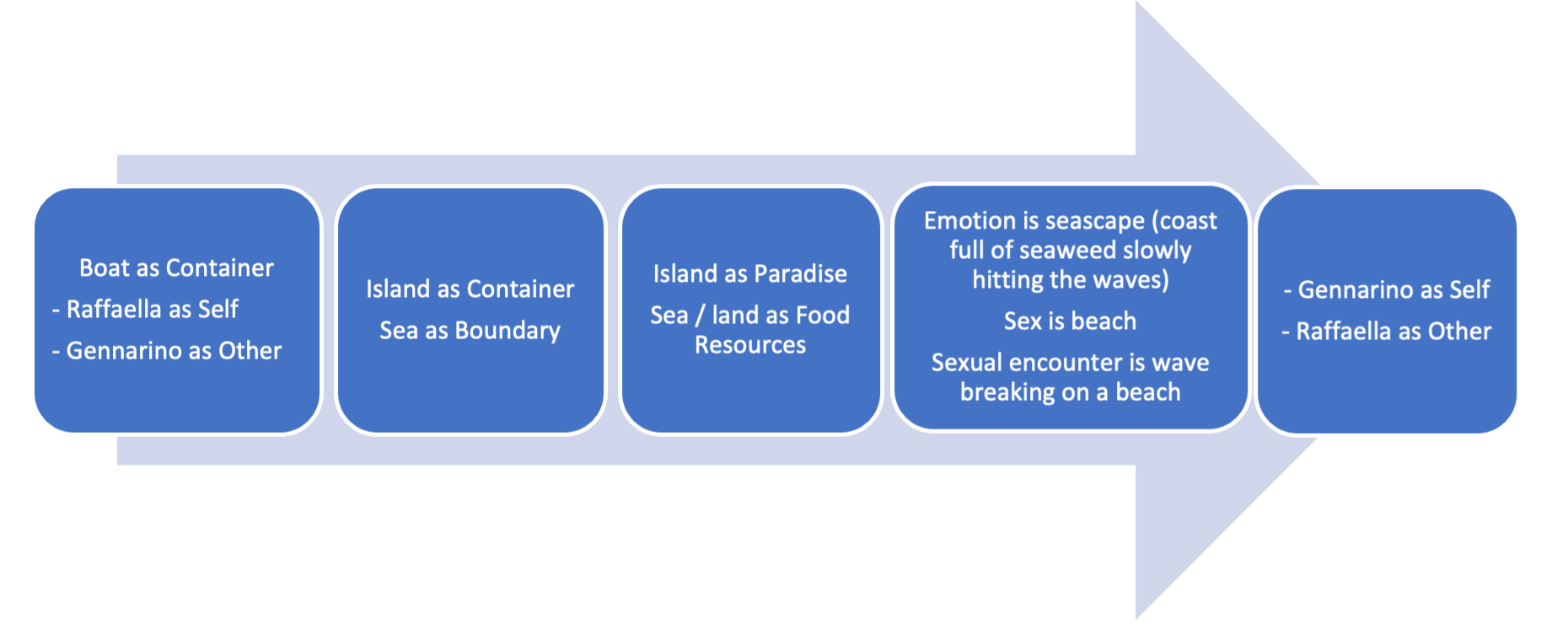

In order to visualize the changes at conceptual level in both films, I represent the dynamics of the island and the sea in both films as they embody different meanings in two figures below. Figure 7 illustrates how in Summer with Monika the urban space remains the same from the beginning to the end, but in the usual fashion of coming of age films the characters have changed through their experience while travelling to the island. In the island setting, the land and the sea change meanings as we move through those spaces following the characters and the framing of the camerawork.

In Figure 8 I have summarized the transition from the boat to the island and the transformation of the characters as well as new meanings associated to the narrative development of the film.

The creative meanings found in Summer with Monika are a combination of the reality of islands as faraway lands and also the idealized views connected to concepts positively evaluated such as love, beauty or youth. Multiple elements can evoke in the viewer the prototypical conception of island as paradise. Another element to bear in mind is the generic conventions of the film. In the case of a coming-of-age or first-love film a location in an island is often related to purity of love, sexuality or idealistic relations between human beings or between human beings and nature. In typical romantic films, the space surrounding the story and the characters reflect the storyline.

From an ideological perspective, separation and remoteness lend the island the additional “not us” space in the oppositional dichotomy that defines the Self against the Other and lays out the foundation of ideologies. The binary view of the world in which opposites confront each other and create tensions and uncertainty is a technique often found in narrative in order to create emotional tension and dramatic situations. Those tensions are often found in the characters as they embody opposite views or in the struggle of human beings against those not considered human. In this anthropocentric view of the world, the environment is both the real struggles the characters encounter and, at the same time, the way the characters change in the face of those struggles. The characters are transformed in their relationship with the environment where they are situated: the deserted island in the Mediterranean and the changeable and rough Baltic sea. Raffaella and Gennarino survive in the deserted island by fishing and hunting and using basic survival techniques. Harry and Monika are not able to find a way to live in the harsh environment of the Stockholm archipelago. Monika’s reluctance to return to Stockholm is visually related to her being more attuned to nature and to her rejection of the abusive world she lived.

Some of the premises these characters live by on the island are related to a biocentric view of the world. According to biocentrism, human beings should be connected to a particular habitat. The self is a transitory state between a self that is past and another self that is “out there” as Snyder (2013:47) says, “[p]art of you is out there waiting to come into you and another part of you is behind you, and the ‘just this’ of the ever-present moment holds all the transitory little selves in its mirror.” As ecological narratives, these islands are realities outside the limits of social conventions. For the young couple in Summer with Monika, they can express freedom and explore new identities. For the couple in Swept Away, living in a deserted island is a return to traditional behaviors, attitudes and gender roles. The characters’ struggle to overcome the dichotomy between humans and nature is dramatized through attitudes, ideas and behaviors that are somehow naïve or virulent. Therefore, although both films narrate a kind of ecological reinhabitation that links closely who the characters are and where they are (cf. Snyder 2013:47), the drama we experience is situated in their failure to integrate both self and place. The anthropocentric framework underlying the experience of the natural environments in those islands inhibits the capacity to adapt beyond standard habits and social expectations.

Endnotes

References

- Anderson, W. (Dir.) 2007. Darjeeling Limited. Fox Searchlight Pictures.

- Arcimaviciene, L., and Baglama, S. H. 2018. Migration, metaphor and myth in media representations: The ideological dichotomy of “Them” and “Us.” SAGE Open, 8(2), 1—13.

- Beitel, D., Gibbs, R. & Sanders, P. 2001. The Embodied Approach to the Polysemy of the Spatial Preposition “On”. Polysemy in Cognition Linguistics. Ed. H. Cuyckens and B. Zawada. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 241—260.

- Bergman, I. (Dir.) 1951. Summer Interlude (Sommarlek) Stockholm: AB Svensk Filmindustri.

- Bergman, I. (Dir.) 1953. Summer with Monika (Sommaren med Monika) Stockholm: AB Svensk Filmindustri.

- Bergman, I. (Dir.) 1968. Shame (Skammen) Stockholm: Cinematograph AB.

- Bergman, I. 1987. The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Branigan, E. 2006. Projecting a Camera: Language-games in Film Theory. New York: Routledge.

- Cameron, J. (Dir.) 1997. Titanic. US: Paramount/20th Century Fox

- Coëgnarts, M., & Kravanja, P. 2014. On the Embodiment of Binary Oppositions in Cinema: The Containment Schema in John Ford's Westerns. Image and Narrative, 15(1), 30—43.

- Dassin, J. 2020 [1948]. The Naked City. Irvington, N.Y: Criterion Collection.

- Flaherty, F. H. (Dir.) 1998 [1922]. Nanook of the North: A story of life and love in the actual Arctic. Irvington, N.Y: Criterion Collection.

- Ford, J. (Dir.) 2007 [1956]. The Searchers. Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Entertainment.

- Gibbs Jr, R. W., and Colston, H. 1995. The cognitive psychological reality of image schemas and their transformations". In Cognitive Linguistics (6): 347—378.

- Gibbs Jr, R. W., and Colston, H. L. 2008. Image schema. In Gibbs Jr., R.W. (Ed.) Cognitive linguistics: Basic readings. De Gruyter Mouton, 239—268.

- Hay, P. 2006. A phenomenology of islands. Island Studies Journal, 1(1), 19—42.

- Hay, P. R. 2013. What the sea portends: A reconsideration of contested island tropes. Island Studies Journal, 8, 209–232.

- Hayward, P. 2012. Aquapelagos and aquapelagic assemblages. Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures, 6(1), 1—11.

- Heise, U. K. 2006. The Hitchhiker's Guide to Ecocriticism. PMLA, 503—516.

- Hitchcock, A. (Dir.) 1938. The Lady Vanishes. M.-G.-M.-Gaumont-British: A Gainsborough Picture.

- Hong, G. 2018. Islands of enclavisation: Eco‐cultural island tourism and the relational geographies of near‐shore islands. Area 52: 47–55.

- Hottenroth, P.-M. 1993. Prepositions and object concepts: a contribution to cognitive semantics, in Zelinsky-Wibbelt, C. (Ed.) The Semantics of Prepositions: From Mental Processing to Natural Language Processing, Berlin/ New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 179–219.

- Hubner, L. 2007. The films of Ingmar Bergman: Illusions of light and darkness. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9780230801387

- Johnson, M. 1987. The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Reason and Imagination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kleiser, R. (Dir.) 1980. The Blue Lagoon, US: Columbia Pictures.

- Lakoff, G. 2012. Explaining Embodied Cognition Results. Topics in Cognitive Science, 4(4), 773–785.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. 1980. Metaphors We Live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lefebvre, M. 2006. Between Setting and Landscape in the Cinema, in Lefebvre, M. (Ed.), Landscape and Film, Abingdon, UK, Taylor & Francis, 19—60.

- Lindstromberg, S. 2010. English prepositions explained: revised edition. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Marjavaara, R. 2007. The displacement myth: Second home tourism in the Stockholm Archipelago. Tourism Geographies, 9(3), 296—317.

- McQuaid, R. W., and Greig, M. 2007. The bridge to Skye, Scotland. In Baldacchino, G. (Ed.) Bridging islands: The impact of fixed links, Charlottetown, P.E.I.: Acorn Press, 189—206.

- Omondiagbe, H., Towns, D., Wood, J., & Bollard, B. 2021. Out of character: Reiterating an island’s imaginaries in the face of a changing identity. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 10(1), 100—117.

- Pugh, J. 2018. Relationality and island studies in the Anthropocene. Island Studies Journal, 13(2), 93–110.

- Rohdin, M. 2009. Multimodal metaphor in classical film theory from the 1920s to the 1950s. Forceville, Ch. and Urios-Aparisi, E. (Eds) Multimodal Metaphor, Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 403—428.

- Ronström, O. 2011. In or on? island words, island worlds: II. Island Studies Journal, 6(2), 227—244.

- Ronström, O. 2013. Finding their place: Islands as locus and focus. Cultural Geographies, 20(2), 153—165.

- Ronström, O. 2021. Remoteness, islands and islandness. Island Studies Journal, 16(2), 270—297.

- Rossellini, R. 1946. Paisà. Rome, Organizzazione Film Internazionali (OFI).

- Sitney, P. A. 1993. Landscape in the cinema: The rhythms of the world and the camera, in Kemal, S. and Gaskell, I. (Eds.) Landscape, Natural Beauty and the Arts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 103—126.

- Snyder, G. 2013. Reinhabitation. Manoa, 25(1), 44—48.

- Steene, B. 2011. Bergman's Landscapes: From Shooting Locations to Metaphors. North-West Passage: Yearly Review of the Centre for Northern Performing Arts Studies. 8, 11—23.

- Taylor, B. 2000. Bioregionalism: an ethics of loyalty to place. Landscape Journal, 19(1—2), 50—72.

- Tyler, A., Mueller, C., & Ho, V. 2011. Applying Cognitive Linguistics to Learning the Semantics of English to, for and at: An Experimental Investigation. Vigo International Journal of Applied Linguistics, (8), 180—205.

- Verdicchio, P. 2015. Blue is the Colour of Forgetting: Mediterranean Re-Orientations in Italian Cinema. Journal of Mediterranean Studies, 24(2), 201–214.

- von Trier, L. (Dir.) 1991. Europa [Zentropa]. Denmark: Nordisk Film, Det Danske Filminstitutet.

- Wertmüller, L. (Dir.) 1973. Love and Anarchy (Film d'amore e d'anarchia, ovvero: stamattina alle 10, in via dei Fiori, nella nota casa di tolleranza). Italy: Prod. Euro.

- Wertmüller, L. (Dir.) 1974. Swept Away by an Unusual Destiny in the Blue Sea of August (Travolti da un insolito destino nell'azzurro mare d'agosto). Italy: Prod. Medusa film.

- Zimmerman, F. (Dir.) 1953. From Here to Eternity. US: Columbia Pictures.