Developing resilience for small island tourism planning: A qualitative design infusing the sustainability trilogy with three streams of resilience thinking

Abstract

Overlooked connections between sustainable development goals (SDG) and principles of resilience (POR) drive this case study through theoretical ‘Streams of Resilience’ thinking to expose disjuncts in gastronomy, tourism, and domestic development policy on Ly Son Island Vietnam. Grounded approach qualitative methodology supports critique of tourism developments filtered through sustainability-impact trilogy dimensions. Findings suggest that socio-economic and natural ecosystem ‘slow accumulation impacts’ result from internal and external geo-political forces. The critical carrying capacity issues for Ly Son are compounded: first by the internal success of garlic-based agritourism development; and second, Vietnam’s desire to increase ‘on-Island’, investment in tourism infrastructure as a sovereignty response to external influences in a disputed Eastern Sea. Global mobility dilemmas trigger island community and national dialogues that must go beyond sustainable livelihoods to ‘all-around’ resilient ecosystems.

Keywords

Ly Son, Vietnam, island tourism, ecological resilience, garlic, agritourism, sustainability, South China Sea, gastronomy, policy intervention

Introduction

In the context of a pre-Covid-19 tourism environment, the UNWTO (2012:4) celebrated gastronomy as a robust destination development tool, “especially important for rural communities (and islands), struggling with rapid urbanization and shifts away from traditional economic sectors”. Gastronomy allows communities to generate income and employment opportunities locally, providing direct tourism jobs (i.e., tour guides or local chefs) while fueling the economy’s general sectors (i.e., agriculture, retail, services). Gastronomy is an understanding of various social cultures, historical components, literature, philosophy, economic status, religion, and others, in which food is the core subject (Medina et al. 2018). The relationship between gastronomy and tourism is shifting “from being a peripheral concern for destinations to being one of the major reasons tourists visit” (Richards 2015:5).

According to James and Halkier (2016), the tourism perspective invites policymakers to fundamentally connect food and tourism through destination branding, provide new food tourism experiences, and push supermarkets and restaurants to supply local food products. The link between food, territory and tourism is further developed by Tsai (2016), stressing the importance of tourists’ experiencing regional cuisines to create a stronger attachment to destinations. In destination management, food tourism development is an economic opportunity to improve small and medium food and beverage enterprises (Munadjat 2016).

Against the above backdrop, developing food tourism on islands has similarities to mainland tourism. Each face challenging sustainability concerns. Both positive and negative, broad tourism development impacts are well documented (Milano et al. 2019). However, island tourism impacts can outweigh benefits to host communities and ecosystem structures if treated as a myopic economic force (Zhu et al. 2017). Subsequently, the elements that attract tourists to islands make them more vulnerable to tourism forces as capacity issues surface and livelihoods become unsustainable. Sharpley (2020:2) reminds:

It is incumbent on all stakeholders to seek or encourage more sustainable forms of tourism — in contemporary parlance, to act ‘responsibly’ (Fennell 2008; Goodwin 2011) — this should be done ‘without hiding behind the politically acceptable yet… inappropriate banner of sustainable development.

Some researchers (Lew & Cheer 2018; Sroypetch & Caldicott 2018) note that the ideal contemporary community is sustainable and resilient. While the goal of sustainability1 emphasizes conservation and change mitigation, resilience aims at adaptation to change for the betterment of community living (Lew et al. 2016). Resilience refers to “the ability of a system to deal with disruption and change while keeping its basic functions and structure — its identity” (Lerch 2015:12). Or, as Hall (2016:413) notes, resilience is “the capacity of a system to sustain a certain set of services, in the face of disturbance, uncertainty, and change, for a certain set of humans”.

Seven core principles underpin a resilience thinking suite: maintain redundancy and diversity; manage connectivity; manage slow variables and feedbacks; foster complex adaptive systems-thinking; encourage learning; broaden participation; promote polycentric governance systems (Wiese 2016). This range suggests a need to analyse how to manage systems and their priorities and who benefits from them. It is, thus, common to envision a notion of economic resilience, but with inequitable social and environmental systems and a division of services that fall unevenly among the population (Hall 2016; Zhu et al. 2017). Lew and Cheer (2018:319) suggest that the divisions are precarious “depending on how a tourism system is defined”. In challenging the central premise of resilience, Carpenter et al. (2001) reinforce the need to understand what is being resilient (defining the system) and what is it being resilient to (defining the driver of change). Therefore, the fundamental question among this what-who web remains: is tourism “the driver of change or is it the victim of change, or is it both” (Lew & Cheer 2018:320)?

The seminal writing of Holling (1973), around tourism in the contemporary context, aptly help to untangle the web, describing resilience as “a measure of the persistence of systems and their ability to absorb change and disturbance and still maintain the same relationships between populations or state variables” (13). Small and isolated islands and their communities often portray living museums of spatial constraint in a temporal continuum epitomizing resilience. At least “in the sense of retaining their numbers and way of life, although they may suffer varying levels of degradation of their island’s original ecology” (Hall 2012 cited in Butler 2018:116).

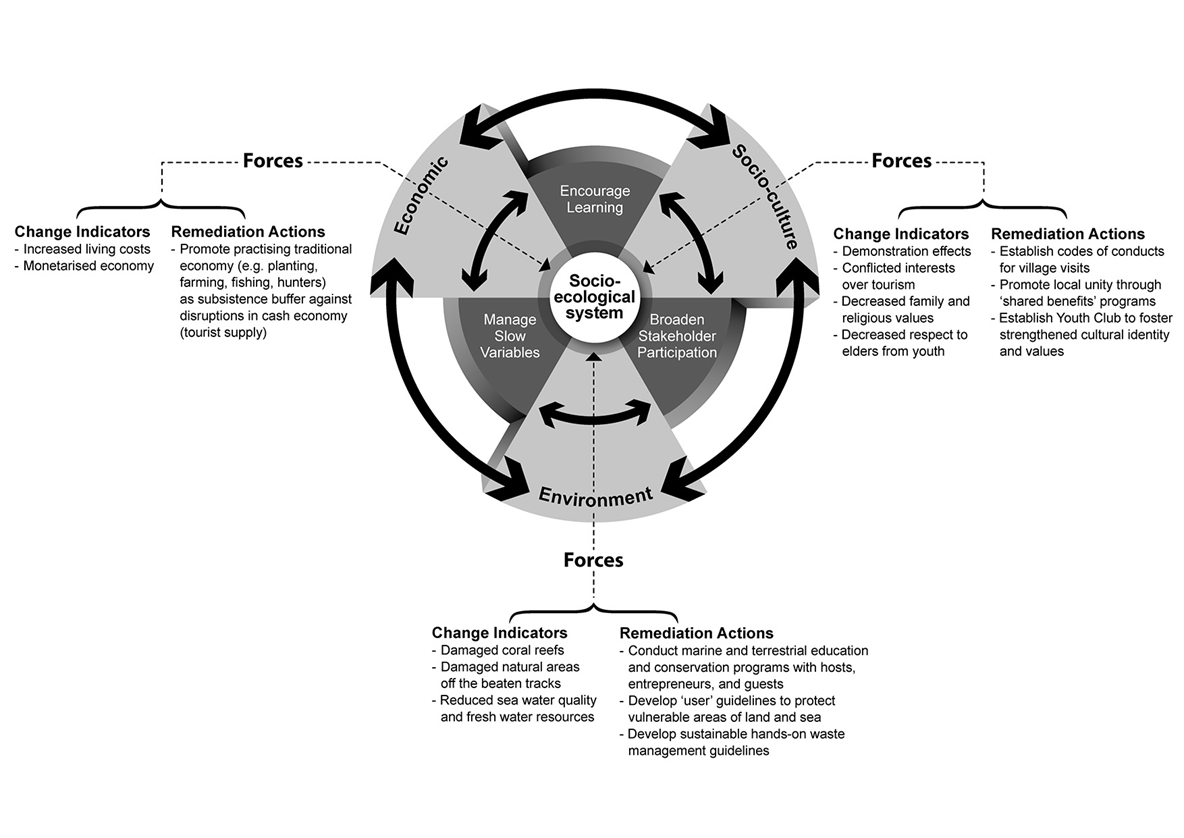

Therefore, the critical connection in thinking between the sustainability trilogy, or triple-bottom-line (TBL) (Elkington 1994) and principles of resilience remains worthy of further consideration. Lew (2014) particularly invites research that encompasses slow change variables to provide a more comprehensive view of resilience. In response, this paper explores the impacts of tourism development on the island destination of Ly Son, Vietnam, through resilience thinking adopting the three-streams framework of Sroypetch and Caldicott (2018) (Figure 1).

Notwithstanding the authors’ acknowledgement to the forementioned suite of resilience thinking streams, herein a prioritizing is proposed; an informed truncation of immediate need through review of Ly Son Islanders’ embrace of three specific foci:

- Encouraging learning among different actors acknowledges both old and new plus scientific and local practices, shared among the various tourism industry stakeholders as the bridge; the infrastructure that builds resilience, and forms the fabric to foundations of sustainable communities (Lew et al. 2016).

- Managing slow variables and feedbacks detect critical variables that may cause the ecosystem to breach a threshold and reform into a different structure (Stockholm Resilience Centre 2015). Developing governance structures that can responsibly react to monitored information is essential as it tests relationships between the State, civil society, and the economic interests through which decisions are made (Börzel & Risse 2005).

- Broadening stakeholder participation support for decision-making through the engagement of external (and perhaps foreign) experience as a valuable supplement to local expertise and a positive way to sustain community development (Sustainability Leaders 2016).

While acknowledged as minimalistic procedures, the three approaches are likewise considered the most accessible and less invasive for LDCs to promote resilience thinking across all community tourism planning and policy development stages. The rest of the paper is structured as follows: First outlined is the literature, namely sustainability’s shortcomings and resilience opportunities, about tourism in particular. Following is the research approach, including the context for the study. After presenting the findings, the discussion draws the local back to global resilience theory as appropriate across three dimensions of stream thinking. Implications for theory and practice are outlined in the conclusion finishing with the study’s limitations.

Literature

For this case study, islands are defined by their small, sometimes micro-geography and relatively undeveloped subset to their sovereign or neighbouring developed continental destinations. Subsequently, developed island nations such as Taiwan, New Zealand, and Singapore are beyond the scope, notwithstanding as sovereign nations, they may well administer such ‘island’ societies. Island tourism, though, is not without problems. Several well-chronicled cases revolve around their geographical location, relatively small populations and areas with reliance on air and sea transport, presenting various opposing forces (see Kokkranikal & Baum 2010). Such influences range through: inflation; increased geological, marine, cultural and historical fragility; locus of local control; and leakage (Sroypetch & Caldicott 2018).

As some commentators (Ratter 2018; Rosalina et al. 2021; Weaver 2017) note, islands and peripheral regions are particularly vulnerable to external influences in all activity forms. They are often highly susceptible because of dependence upon ‘off-island’ agents and their respective agencies, providing services additional to their regional/national governments, continually pursuing different priorities and policies to those of the island population. However, to adapt and thrive in such environments, the collective agency is vital for structural change, an aspect often missing in peripheral communities, making them more vulnerable (Chen et al. 2020). Moreover, it is how islanders adapt to vulnerability characteristics that influence island carrying capacity and critical sustainability.

However, Girardet (2013) asserts that sustainability as a lone concept is unhelpful. While adopted as a guiding principle for collective human action since the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, there is ever more pollution, biodiversity loss, and climate change three decades on. The sustainability concept suffers abuse. Girardet (2013:1) continues, “much damage has been done to the world’s ecosystems already, and urgent solutions need to be found to reverse it” … “rather than just sustaining it in a degraded condition” (Wahl 2017:1). Sustainability itself does not tell us what we are trying to sustain. Indeed, how long is sustainable, and who should benefit? Wahl (2006) suggests that answers lie in the underlying pattern of health, resilience and adaptability, stating such conditions maintain this planet in a balance where life as a whole can flourish. Reed (2007:674) advocates for “living-systems thinking” — a foundation shift in a mental model needed to create a “new” culture. A human culture — healthy, resilient and adaptable — cares for the planet, and it cares for life in the awareness that this is the most effective way to create a thriving future for all of humanity (Wahl 2017). Thus, the concept of resilience is closely related to health. It describes the inherent ability to recover essential vital functions and bounce back from any breakdown, albeit an emergent crisis or slow accumulation.

Islanders, both generational residents and newcomers, governments and tourism agencies often draw upon cultural knowledge and historical practices to create innovation, quality products and educational experiences that contribute to lifestyle and livelihood resilience. However, structural change, including population and tourism growth, shifts in public sector focus, and internal and external power (political) imbalance, can exacerbate tensions and conflicts. Such are often evident within island communities as they struggle for survival in rapid or slow change environments (Kim & Jamal 2015).

Furthermore, the lack of resource diversity on islands often leads to the over-exploitation of limited supply, not least those related to tourism. Economies of an island made up of various commercial undertakings will likely be better equipped to deal with changes and potential shocks and are thus more resilient (Boschma 2015). Likewise, island communities with widespread ICT (information communication technology) adoption advantage over those isolated from such enhancement tools. Interaction and participation through digital technologies often feature as ‘solutions’ to vulnerabilities (Gössling 2021).

The lack of strategic planning is also a challenge in many islands. In some cases, governments do not plan for long-term sustainability, such as climate change. Instead, policy decisions focus on short-term economic benefits over long-term social and environmental concerns without environmental protection or appreciating cultural heritage (Sims 2009; Sroypetch & Caldicott 2018). As a leading example of mature island nations, New Zealand champions change to warn against this paradigm. Prime minister Jacinda Ardern attests, “Economic growth accompanied by worsening social outcomes is not success … It is failure” (McCarthy 2019:1). Ardern advocates using the United Nations’ Global Goals as guiding principles of success, suggesting, “every policy pursued by a government should improve the human welfare of all people in a society” (1). Additionally, large-scale tourism puts severe pressure on communities (not least islands) coping with the influx of tourists when, in peak season, tourists can significantly outnumber the residents in hotspot destinations (Muschter et al. 2021). Such overtourism contributes to shortages of resources like fresh water and electricity supply plus overtaxing waste services and sewage facilities if such infrastructure exists.

Global trends in tourism development indicate that many island economies need tourism but have much to fear from a poorly managed industry (Bangwayo-Skeete & Skeete 2020). The visitor’s experience deteriorates due to the sector’s success (Butler 1980; Cayman Island Department of Tourism 2018). Hence, developing and managing tourism is a significant challenge in island tourism (Kokkranikal & Baum 2010), particularly when singularly viewed as the core economic enabling force. Instead, tourists and hosts as custodians must be part of an interactive biosphere. A contemporary and significant challenge is how communities manage these interacting socio-ecological systems due to tourism disruption. Sroypetch and Caldicott (2018:260) argue those “not yet applying resilience thinking within their tourism policy arrangements are teetering on a precipice”.

Destination policy settings reflect the influence and interplay among different tourism stakeholders (Weiler & Caldicott 2020). Recognizing the complexity of planning and policy processes, Gunderson (2001) explains the context of adaptive socio-ecological systems where positive impacts are more likely to result when strong proactive interactions exist between ecosystems and society. In contrast, Gossling (2003) anticipates adverse effects when the stakeholder interplay’s significance is not well understood; and social-, ecological-, and political-systems operate independent and not least in opposition to each other (Weaver 2017).

In an enduring global effort to lessen development’s oppositional forces and strengthen proactive interactions, all United Nations member states adopted the 2030 agenda for sustainability in 2015 (Stockholm Resilience Centre 2015). It provides a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. At its heart are 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) calling for action by developed and developing countries. Such ambitions “recognize that ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth – all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests” (The United Nations 2018:1). In essence, ‘whole-systems’ thinking (Reed 2007) or simply ‘all-round sustainability’ (Sims 2009) is required.

Notwithstanding such holistic ambitions, tourism impact studies commonly anchor back to the familiar and long-standing sustainability trilogy (TBL) with social, environmental and economic dimensions (Wall & Mathison 2006). The three dimensions act as a core framework for impact analysis on economic viability, ecological preservation and societal wellbeing (Mawhinney 2002). While sustainability is the often mentioned goal of businesses, non-profits and governments, knowing the degree to which an organization or destination is sustainable or pursuing sustainable growth can be challenging (Slaper & Hall 2011). The TBL framework goes beyond the traditional accounting measures of corporate profits, return on investment and shareholder value, to include ecological (environmental and social) dimensions. Recognizably difficult to always assign appropriate means of measurement, the TBL dimensions commonly labelled the three Ps — people, planet and profits — create a simplified win-win-win management tool (Slaper & Hall 2011). In reality, though, there is a fourth P, that being political (Butler 2015) because implementation will only occur if proposed developments and policies are politically acceptable. As such, unanswered questions remain about how best to mitigate tourism impacts on destinations and how communities can change with adaptation through resilience principles. Not to change, not to adapt, is the alternative “slow decline” scenario presenting a “muddle-through” approach with possible worsening impact scenarios (Gittins 2019:1). Resilience planning offers an alternative to the sustainable development paradigm to provide novel perspectives on community development and socio-ecological adjustments to a rapidly changing world. By presenting a coherent interpretation of linked human and environmental processes, a resilience thinking framework aids understanding in local to global terms.

Methodology

The data collection proceeded on Ly Son Island and the Vietnam mainland — Quang Ngai Province — through three data-gathering field trips in 2013, 2014 and 2017, with a final monitor and review visit in 2019. The methods used in the fieldwork were non-participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and informed conversation (Caldicott et al. 2017; Hutchby & Wooffitt 2008; Neuman 2006).

Furthermore, annual socio-economic development reports, policies, strategies, and master plans for tourism development garnered from within the three levels of governments: the central Vietnamese government, Quang Ngai provincial government, and Ly Son Island district government, were reviewed. The study was further guided by Mill & Morrison’s (2002) six touristic destination-mix elements, including attractions, facilities, utilities, infrastructure, transportation, and hospitality services. Table 1 presents an inventory of destination-mix element interests catalogued as natural, cultural, and historical.

| Natural | Cultural | Historic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attractions |

Landforms:

|

Structures:

|

Memorials:

|

| 2. Utilities |

|

||

| 3. Infrastructure |

|

|

|

| 4. Transport |

|

|

|

| Accommodation | Restaurant | ||

| 5. Facilities |

2013:

|

2013:

|

|

| 6. Hospitality Services |

2013 workforce:

|

2017 workforce:

|

|

First, observations focused on how local authorities and Islanders utilize Ly Son’s historical, natural and cultural assets for tourism. Note-taking and photography were the primary means for recording observed data visible to the outsider’s eye (Blix 2015).

Second, key stakeholder interviews provided an insider’s understanding and appreciation of how tourism (and agriculture) impacts the six destination mix elements. Thirty semi-structured and snowballing face-to-face interviews (see Table 2) offered the opportunity for extensive probing to gain information (Neuman 2006). Interviewees represented Ly Son tourists and tourism operators, other residents (fishers, garlic farmers and restauranteurs), and government officials from Central to District levels. The interviews, averaging 30 minutes, concentrated on tourism policies, the strategies and plans for tourism development, and the tourism experiences on the Island. With the participants’ permission, transcribed interview recordings supported thematic analysis.

| Participant (P) | No. | Interviews (IP) | No. | Conversations (CP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National government | 2 | # 1, # 3 | 0 | |

| Local government | 2 | # 7, #8 | 3 | # 1, #2, #6 |

| Fisherman | 3 | #6, #9, #11 | 2 | #17, #20 |

| Tourist operator | 4 | #20, #24, #27, #28 | 3 | #11, #14, #15 |

| Festival organiser | 2 | #2, #4 | 4 | #28, #29, #30, #36 |

| Business owner | 4 | #12, #13, #17, #19 #30 | 10 | #9, #10, #12, #21, #22 #31 #32, #33, #34, #35 |

| Garlic farmer | 4 | #5, #18, #22, #23 #26 | 7 | #13, #16, #18, #19, #24 #25, #27 |

| Ly Son visitor | 7 | #10, #14, #15, #16 #21, #25, #29 | 8 | #3, #4, #5, #7, #8, #23, #26, #37 |

| Total | 30 | 37 |

Finally, 37 informed conversations further unearthed how participants understand and respond to each other through “naturally occurring talk-in-interaction” (Hutchby & Wooffitt 2008:121). The conversational steering (see probing questions below) allowed Islanders to express what they wanted or did not want, with regards to tourism development on their island, and why they held these views:

- What sort of changes have you seen on the Island?

- Has tourism played any part in these changes? If so, how?

- What are the benefits?

- What are the problems that tourism creates?

- What has been your experience with tourism on the Island?

Introducing the Ly Son Island case study

Geographic context

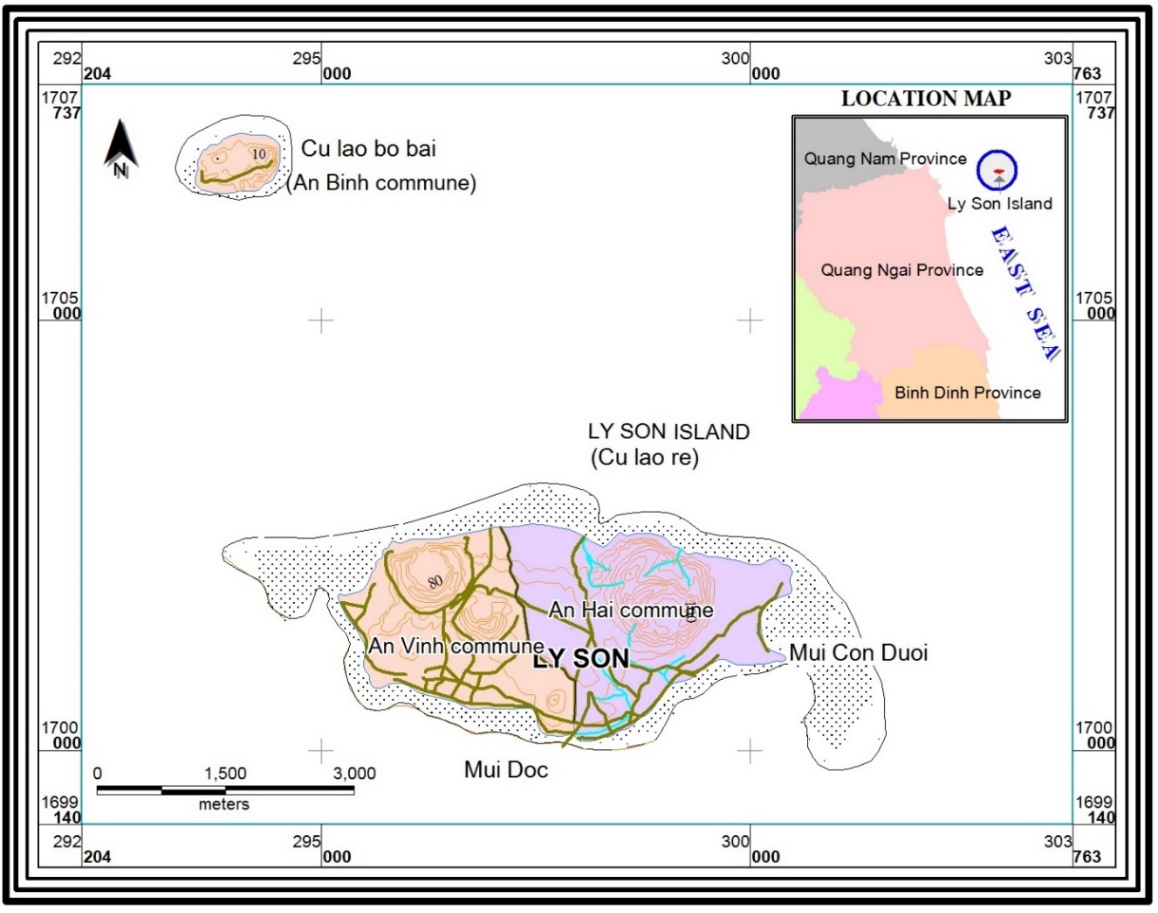

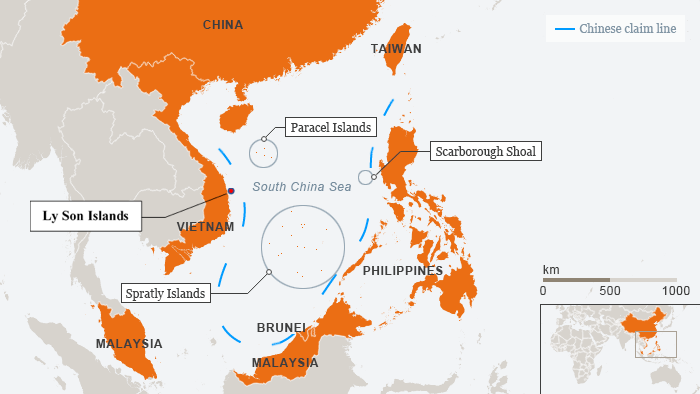

Located along the Indochinese Peninsula’s central coast, Ly Son lies between 109º08 East and 15º23 North. Such coordinates are relevant considering the deeply complicated and intractable South China Sea disputes later discussed. As an island district of Quang Ngai Province of eastern Vietnam (see Figure 2), Ly Son holds strategic rights of security and defence and economic, cultural and environmental significance for the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Vietnam has sovereignty across a significant portion of the Eastern Sea, including a claimed Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of over one million square kilometres. It also claims two major offshore archipelagos: the Paracels (Hoang Sa) and Spratlys (Truong Sa) (Vietnam Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2010). The geo-politics linking resources, geography, and state territoriality to world-power politics displays through such spatial claims is also discussed later.

The Ly Son Islands comprise three islands, Big Island (Ly Son or Dao Lon), Small Island (Dao Be), and Mu Cu Islet (Hon Mu Cu). As the focus of this case study, Ly Son measures just 5.5 kilometres by 2.7 kilometres and has a total landmass of only 11 square kilometres (Tran Thi Mong Nam & Ta Thanh 2000). The majority of the islander population (c.21 000) resides on Big Island in An Vinh and An Hai’s communities. Just 500 persons inhabit An Binh Commune on Small Island, and Mu Cu Islet is uninhabited (www.quangngai.gov.vn).

As a remnant volcano, Big Island (Ly Son) has five prominent craters, with the largest Mount Thoi Loi. Otherwise, the topography is predominantly flat, with an average elevation of 20-30m. The Island has no rivers, and only small streams form during the rainy season. To the northwest of Ly Son, a series of submerged banks support tropical ecosystems that sustain valuable bottom plants species such as rare reef varieties of blue, black, and gold corals, additionally to high-value seafood as abalone and giant clams (Van Hao 2013).

Access to Ly Son is by ferry (Figure 3) across the 20 nautical miles strait from Sa Ky port in the Quang Ngai mainland province.

Historic context

Mainly, Ly Son Islanders belong to Vietnam’s dominant Kinh [Viet] ethnic group, with archaeology indicating a history of human presence over 25,000 years (Nguyen Dang Vu 2013; Pham Thi Ninh n.d.). According to Island family records (gia pha), Ly Son’s current occupation dates to around 1545, when the Islands served as a military base for marines who played an important role in asserting Vietnamese sovereignty of the Eastern Sea (Nguyen Dang Vu 2007). As the Island population grew, inhabitants developed skills as sailors primarily involved in fishing. However, some engaged in salvage operations from the many sunken ships in the area. Subsequently, the Hoang Sa Flotilla charted and monitored sea routes in the region, protecting and affirming Vietnam’s claims over the Eastern Sea. Islander engagement in such past activities displays through their intimate knowledge of and general occupation of the wider South China Sea marine environments.

Contemporary context

Despite tourism growing as an income source for Islanders, marine and terrestrial agriculture’s primary economic activity remains. More than 10% of the population fish regularly. Over 400 boats with capacity reaching deep into the Eastern Sea yield more than 33,000 tons annually (Ly Son District Government 2020). Harvested mackerel, tuna, cuttlefish, shellfish, sea cucumber, seaweed, and sea coral bring substantial income for Islanders (Tran Thi Mong Nam & Ta Thanh 2000). In addition to marine interactions, about 90% of the population is involved in terrestrial agriculture. Garlic farming has long been the most critical land crop for the local community. Ly Son is often referred to as the ‘Kingdom of Garlic’ within Vietnam due to the root delicacy’s unique gastronomic and medicinal qualities (Matsutomo 2020).

While Ly Son remains well-known in Vietnam for its heritage settlement, natural and cultural attractions, its tourism and gastronomic prominence are still developing. The Island’s geological structure of lava rock forms many natural features such as Cau Cave and To Vo Archway, supporting organized and independent tourism activity. Ly Son accommodates nearly 100 historical, religious, and cultural relics and festivals (Nguyen Dang Vu 2007). Many have protection under the provincial and national ‘Certificate of Designation of a Historical and Cultural Relic’ [Di tich lich so van hoa] (Tran 2016).

Ly Son has grown in recent years beyond its domestic tourism appeal to international acclaim with such distinctive cultural features. Domestically, Ly Son’s reputation continues to rely on its natural and cultural heritage maintained through terrestrial (garlic) and marine (seafood) production. Internationally, the South China Sea dispute between several claimants, and the international spotlight this brings to the region, is one aspect leading to broader interests in the Islands (Jenner & Tran Truong 2018; Lam 2020; McRae 2019). In the present day, and the wake of phenomenal global media attention on the area, Ly Son Island is now back at the coalface of sovereign protection (Figure 4).

Findings

Agriculture, garlic, gastronomy-tourism, and their environmental consequences

According to Lee et al. (2015), gastronomic tourism follows food tourism as a journey in regions rich in gastronomic resources to generate recreational experiences or have entertainment purposes. Such food experiences include visits to primary or secondary producers, festivals, fairs, events, cooking demonstrations, food tastings or any food-related activity (Hall & Mitchell 2001). According to tourist operator (IP#20), “although Ly Son is very famous, and popular, among tourists for its seafood, its distinction within traditional food heritage is garlic”. The scientific name is Allium Sativum L — is just one of the many Vietnamese white garlic varieties though its characteristics are significantly different from mainland varieties. A government representative (IP#7) identified the land area primarily under garlic cultivation at around 300 hectares, accounting for approximately 35% of the island (Figure 5). Conferring, a further government representative (IP#8) suggests the annual garlic yield averaging 1500 tons is the most valuable export product for the Islanders.

Ly Son’s ‘Normal’ garlic, with pieces commonly described as pearl-white, is thus often called ‘Pearl’ garlic (toi ngoc). It is generally medium-sized with 12–20 cloves and has a very spicy, fragrant, pungent aroma (Figure 6). However, and most significantly, it is not perceived to cause rancid breath, and this gives the garlic of Ly Son a particular advantage over other varieties. Additionally, the dried garlic can keep from four to five months in tropical weather without sprouting, further benefiting the variety (Ho Huy Cuong 2009).

According to a farmer (IP#5), the essential thing that makes Ly Son garlic less repugnant is soil preparation. Local farmer (IP#23) explains:

Because of the lack of fresh water on the island and the dry ground, we take coral sand from the coast or soil from the foot of the volcano and mix it with ash, manure, and decayed seaweed to spread a fertile layer around 10 cm deep across the fields before seeding.

Farmer (IP#5) further elaborates how a deposit of smooth white sand is spread on the top every couple of seasons, with the old sand layer removed:

This sandy soil is the key factor determining the garlic’s special flavour. The introduced volcanic soil and the coral sand containing high amounts of calcium create a special fertile mix that gives Ly Son’s garlic different flavours. Moreover, the smooth white sand on the top helps protect seeds from the sun, keeps them damp, and provides salt for the plants.

Ly Son farmers water the plants in the early morning and again in the afternoon to help neutralize the salinity (Thong Thien 2014). In the absence of any rivers or streams on the island, the freshwater used for irrigation comes from Big Island’s largest volcano. Ly Son garlic is generally planted in October and harvested in mid-February following, with one planting per year. With advantageous weather conditions, “the 100 m² plots can produce nearly 100 kg of fresh garlic which converts to around 70 kg in dried form” (Government representative IP#3).

Besides ‘Normal’ garlic, there is another extraordinary variety grown. Its name is ‘Rare, Strange Loneliness’ garlic. This variety has one clove, and it is round like an onion. Farmer (CP#24) says:

… the locals call them as ‘A’ garlic [toi mot], ‘Lonely’ garlic [toi co don] or ‘Orphan’ garlic [toi mo coi], and this type only appears in poor seasons when there is low water and, even then, each hectare of arable land only generates about 2 kg.

The scarcity of ‘Lonely’ garlic and “perceptions of its nutritional and health value allow it to reach retail prices on the mainland at 5–7 times the cost of standard garlic; approximately USD50/kg” (Government representative IP#3). Additional to garlic playing an essential and decisive role as a staple economic generator for local Islanders, “its emergent potential, and attractiveness, as a new gastronomic tourism product is recognized” (Government representative IP#1). Tourists observe the process of planting and cultivating garlic and learn of its unique qualities. They also buy fresh garlic and enjoy many traditional garlic-based food dishes. Hence, the Island’s domestic reputation as the ‘Kingdom of Garlic’ is spreading as international tourists increasingly seek to learn and indulge in veganism’s health benefits, and not least of garlic.

Government representative (CP#8) relishes that “Ly Son is becoming a popular gastronomic tourism destination”. Local business owner (IP#19) further elaborates on the root vegetable appeal, suggesting garlic is also one of the main ingredients to embalm meat or fish within the local cuisine style. She exclaims, “when combined with fish source, onion, lemongrass and sugar it makes the beautiful smell when grilling, roasting, frying or sautéing”, a sensation the visitors enjoy. Besides the aroma, the business owner (IP#12) ads, “before cooking, we also put garlic, onion and chilli powder into hot oil to colour our food dishes”. A bowl of garlic, fresh chilli, and fish sources are ever-present on the table in everyday meals. Several restaurant owners openly shared examples of their traditional food dishes, demonstrating the distinctive regional cuisine heritage of Ly Son. By measure, “garlic salad (Figure 7) is very special with residents on the Island and health-seeking tourists because they consider this dish as medicine that helps prevent colds” (Business owner IP#13).

Business owner (IP#12) suggests that fried garlic leaf is like garlic salad, with “locals consuming this dish with a cup of Vietnamese white wine before they go fishing”. The residents on Ly Son Island also use garlic leaves for cooking soup. A tourist operator (IP#27) further describes the preparation of “garlic leaves for cooking fish soup”.

Vietnamese people consider garlic a delicacy and traditional medicine that they claim is good for the liver and the stomach. They suggest that anecdotal evidence links ‘Lonely’ garlic with distinctive medicinal elements that can help reduce high cholesterol levels and high blood pressure. Its further claim is to prevent cold, relieve fever and phlegm, detoxify the body, kill bacteria, facilitate urination, and treat dysentery, indigestion, and constipation. Furthermore, the locals believe ‘Lonely’ garlic can also help prevent blood clot formation, which may cause heart attacks or strokes. Notably, the locals believe this kind of garlic will help prevent cancers. A business owner (CP#31) claimed:

‘Lonely’ garlic can inhibit the development of cancerous cells and prevent free radicals from destroying healthy cells. Believing this, we make a lonely garlic-soaked wine to drink a cup per day with the meal.

Observing and understanding the process of how Ly Son people grow and cultivate garlic is the distinctive feature for fostering new tourism development on the Island. Additionally, learning how they use garlic as the vital ingredient of some unique food dishes and drinks ads strong gastronomic and medical interest for those visitors seeking alternate therapies. Although garlic continues to develop as the pull factor of ‘fresh’ tourism products, unfortunately, the potential for positive tourism impacts also comes with negative garlic production consequences.

Islanders have mined sand from the coastlines for fertilizing their prized crop for many generations. This action’s consequence is visible in the many scared and degraded beaches around the Island. In fact, along with sand mining in shallow coastal waters (Figure 8), garlic growers take the coral and sand from shoal areas up to eight kilometres from the Island. They increasingly import sand from the mainland. If this unchecked extraction continues, the beaches and coral fringes around the Island will cease to exist, undermining the natural tourism appeal. Adverse effects of farming on coastal and small-island environments are well known (Carlson et al. 2019), and Ly Son’s results are particularly poignant. However, these will not smoothly resolve while garlic plays the number one role in locals’ economic welfare.

Notedly, projecting future central government policy for tourism expansion on Ly Son, the district government may need to consider importing sand to reconstruct some beaches. Such a contrary circular practice highlights tourism policy’s disjunct between national and local perspectives, a common phenomenon promoting conflict between stakeholders (Caldicott et al. 2014). The disjunct further demonstrates through mining activities that reportedly impact Big Island’s inshore fishery, seemingly exhibiting a depleting fish habitat. Local fishermen (IP#6), recalls “we now go fishing further from the Island because fish numbers close to shore have severely diminished”. Garlic farming is also reportedly causing additional problems for Islanders. Freshwater supply is limited, and residential, agricultural, and tourism land-use conflict is under duress. The critical issue is that the population density on Ly Son, at 1,856 people/km2, is already relatively high. With most inhabitants involved in agriculture, the juxtaposing phenomenon in Ly Son’s history is placing substantial stress on the Island’s future environmental and social ecology. Government representative (IP#7) advised the area of land for agriculture is allocated at 100m2 per capita, and thus:

… the population density coupled with the agricultural reliance on irrigation contributes to the Island’s water vulnerability. The Thoi Loi Volcano Reservoir reaches its annual draw-down capacity of approximately 20,000 cubic meters.

As a result, Ly Son has already experienced severe freshwater shortages in recent years. The over-exploitation of the natural resources are further indicators of a severe threat to the Big Island’s environmental ecology and a particularly acute situation on the Small Island. Farmer (CP#13) recalls, “before 2012, as Small Island residents, we were often reliant on saved rainwater stored in tanks for our personal and irrigation needs”. Although Islanders collected this water during the rainy season (September to February), they were nearly always without in the dry season. Sometimes, locals buy water from the Big Island. Post-August 2012, and the construction of a desalination station on Small Island, the situation eased. Farmer (CP#13) rejoices that “we no longer worry about this problem for our living purposes, but we still need additional irrigation water for our garlic fields. The extra tourism demands are not helping”.

There are several paradoxes in sustainability on islands — some familiar to tourism destination development studies and some more unusual. The first concern is the sustainability of an island’s traditional ‘subsistence livelihood’ activities and lifestyles (Sroypetch & Caldicott 2018). A growing resident population, and tourism expansion, are causing Ly Son’s traditional livelihood system and the ecosystem that sustains it to become unstable. Second, the Island’s heritage landscape of garlic fields is highly unusual, and this represents a key selling point from a ‘heritage-’ and ‘gastronomy-tourism’ perspective. However, current production systems and proposed expansion are problematic in terms of the environment. Unless areas of cultivation can be reduced, with a subsequent reduction in water and sand mining reliance, break-point pressure will be catastrophic for land and sea ecosystems. Unfortunately, given the lack of evidence to likely central government or private sector subsidies to finance re-orientation of garlic operations to an alternate range of sustainable enterprises, including tourism, residents are expected to continue with the status quo. Garlic farming is a significant economic generator and an emerging mass tourist attraction. However, in apposition, its production processes are harmful to the environment and negatively impact tourism attractiveness.

International geo-politics, domestic economic tourism policy and their environmental consequences

This study found no commercial tourist activity on Ly Son Island before 2000. Reinforcing this point, a systematic analysis of government documents shows that the strategies and policies for Ly Son Island’s socio-economic development between 1975 and 2000 were completely void of any planning for tourism. Post-2000, high-speed ferries were introduced to the Island, significantly improving transportation access. However, during 2000–2009, Island visitors continued to be serviced by only a couple of guesthouses with about 30 rooms combined. At this exploratory stage of destination development (Butler 1980), there were no hotels or restaurants as revealed by the owner of a Ly Son Hotel (Tourist operator IP#28):

… before 2000, most people who travelled to the island were traders coming to buy garlic and government officers conducting government business. There was only the District Guesthouse for accommodating these outsiders to the Island.

For past centuries, Ly Son was commemorated in Vietnam as the Hoang Sa Flotilla’s homeland, and more contemporarily — the ‘Kingdom of Garlic’, each with significant festival status attracting domestic visitors. However, it has also attracted international attention because of the South China Sea (Eastern Sea) disputes2. Each activity brings focus to Ly Son as a destination of the future.

In 2007, as reported by the Ly Son Department of Culture, Sport and Tourism, total tourists travelling to Ly Son Island numbered just 2,112 and among them were 41 internationals (see Table 3). In 2008 this increased to 2,500 (97 internationals), indicating tourism’s minor role in the island’s economic structure. However, between 2009–2019, visitation increased markedly, from 4,515 (92 internationals) to 227,830 (1,600 internationals) respectively.

| Year | Domestic visitors | International visitors | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2,071 | 41 | 2,112 |

| 2008 | 2,403 | 97 | 2,500 |

| 2009 | 4,423 | 92 | 4,515 |

| 2010 | 8,680 | 120 | 8,800 |

| 2011 | 8,155 | 45 | 8,200 |

| 2012 | 8,602 | 98 | 8,700 |

| 2013 | 28,759 | 95 | 28,854 |

| 2014 | 36,239 | 381 | 36,620 |

| 2015 | 100,000 | 950 | 109,500 |

| 2016 | 164,067 | 933 | 165,000 |

| 2018 | 229,089 | 1,231 | 230,320 |

| 2019 | 226,230 | 1,600 | 227,830 |

Ly Son’s district government division officer (IP#8) suggested several reasons. First “is because of international attention following China’s unilateral submission, in 2009, to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)”. Therein, China presented the ‘U-shaped nine-dash line map3’ (Figure 9) claiming significant areas the South China Sea” (see also Gao & Jia 2013; Jenner & Tran Truong 2018; McRae 2019; Zheng 2020).

Second, China’s actions continue to stifle government relations between the two countries and transcend to media documented open tensions between the Chinese military and the Vietnamese fishermen for over a decade (Bangkok Post 2012; SCMP Reporters 2020). According to a government representative (IP#1), “one particular incident occurred on 2 May 2014, when China placed a state-owned drilling rig M/V Hai Yang Shi You 981 in Block 143 inside Vietnam’s EEZ without prior permission”. Subsequently, a Ly Son fisherman (IP#11) relayed that “Chinese ships increasingly attack us with unprovoked regularity”. The media reports small Ly Son fishing boats rammed with crew members beaten up and destroyed equipment (Boykoff 2016; Lau 2020).

Such issues reignited awareness among Vietnamese people how Ly Son Islanders’, who once protected the country’s sovereignty, are today once again defending the country’s territorial integrity (SCMP Reporters 2020). As recalled through the fisherman’s conversation (IP#20), such patriotism abounds, “we are determined to go ahead with offshore fishing and protect our traditional fishing grounds”. After international media exposed the altercations, world attention to Ly Son increased. More people came to know about the Island, and so too, its tourism destination appeal further improved with a 2019 visitation value4 of VND 200 billion or around USD 10 million (www.quangngai.gov.vn).

The rising local tensions and international attention to the sea and islands of Vietnam give rise to the central government instigating several investment projects in the region. Ly Son Island district receives budgets from the central government and Quang Ngai province to boost regional socio-economic development, including tourism. Such significant investment in new infrastructure, including roads, power distribution, water supply, a hospital, schools, produce retailing, and the fishing ports, enhanced and transformed the Island’s face in a short space of time. Government representative (IP#7) advised, “tourism is now the master key in the central, provincial, and district government plans for the future development of Ly Son”.

On 22 January 2013, the Prime Minister issued Decision No. 201/QD-TTg approving The Tourism sector’s master development plan to 2020 combined with a vision of Vietnam in 2030. The bold goals included forming 46 national tourist zones, 41 domestic tourist destinations, seven tourist areas, and 12 tourist cities. Accordingly, the aim was also to develop Ly Son into one of the national tourism destinations with the optimistic target that, by 2025, the Island would become a maritime economic centre. The Decision’s focus is unreservedly on tourism and aquaculture (Vietnamese Government 2013). Furthermore, in Decision No. 163/QD-UBND, Quang Ngai Provincial People’s Committee (2015, 3 June) also approved a ‘Tourism master development plan to 2020 with a vision to 2025 for Ly Son Island’.

While the central master development plan determined Ly Son as one of 41 domestic tourism destinations, the Provincial document identifies more specific and localized economic and social objectives for the Island. Primarily, it paves the way for Ly Son to become a ‘green maritime urban (do thi bien) centre’, one of the most attractive tourism destinations in Quang Ngai Province and the South-Central Coast. Its primary aim is to attract domestic and international visitors (see Ly Son District Government 2015). Through the series of long-term preferential development policies from the three-tiers of government, the 2025 target for Ly Son remains valid (despite Covid-19); an island of growth and a centre of the marine economy with dual drivers of aqua/agri-tourism and leisure tourism (Ly Son District Government 2020; Vietnamese Government 2013).

According to a government representative (IP#7), the investment in infrastructure development “boosts economic growth and aids poverty reduction on the Island, but it is also an integral enabling ingredient for tourism development”. For example, in March 2014, Ly Son still only had one hotel, ten hostels and 12 homestay services with 79 rooms in total. However, as a business owner (IP#17) advised, by October 2018, “numbers have increased rapidly”. Ly Son now has 110 accommodation facilities consisting of six hotels, 47 hostels, one guesthouse and 56 homestay services. Government representative (CP#7) confirmed these establishments are now supplying more than 650 rooms for 2,500–3,000 guests. During the 2019 monitoring visit, personal observation reveals 14 new boutique accommodations with approximately 100 rooms constructed in response to pre-Covid increased demand; though not unexpectantly anecdotal reports suggest this has now slowed due to Covid-19 and the international barriers to travel.

Ly Son’s transition from ‘slow accumulation’ to ‘rapid growth’ now bears critical importance, promoting careful consideration to the Island and its ecosystems’ carrying capacity. Of particular concern are freshwater supplies and environmental degradation of coastal and offshore habitats. Increasing resident populations is exacerbating the already high-density ratio of Ly Son. Coupled with the central government projected future tourist visitation to the Island, Covid-19 withstanding, the actual situation is at a tipping point. For example, the festival organizer (IP#4) told of the traditional practice “…we throw our rubbish directly into the sea”. This behaviour is causing the coastal waters to resemble floating rubbish heaps rather than unspoiled natural beauty inviting of tourism. The pollution observed around the An Hai, and An Vinh communes consisted of lots of plastic bags with rubbish inside floating on the water surface. The waste dumping practice was particularly poignant along the new esplanade road where advisory signs explicitly directed persons to dump through a hole in the sea barrier wall:

‘Attention! Dump rubbish through here — into the water!’ and ‘Do not throw rubbish on the bank — throw to the water’ (Figure 10).

A government representative (IP#8) advised that the district government had received grants around 2014 to invest in waste management. Specifically, they constructed a waste treatment facility to meet Islanders’ demand for disposal of around 30–40 tons of rubbish per day within this area. A government representative (CP#6) confirmed, “we then introduced a rubbish collection and transportation service in 2015 to feed the treatment facility”. However, dumping was still apparent during the 2019 monitoring visit, with locals throwing the rubbish from the morning and night markets directly into the sea.

Moreover, with the government’s planned promotion of tourism, any increased visitation can exacerbate the seriousness of the waste situation. For example, many visitors to islands participate in festivals, which, unfortunately, generate large amounts of solid waste (Marra 2016). This circumstance is acutely apparent in the Ly Son ferry port. As tourism vessels pulled away from the jetty after a recent festival, observed rubbish covered the entire harbour surface (Figure 11). Local festival organizer (IP#2) conceded:

… the present behaviour of festival-goers, resident stallholders, and local boat operators is not something we are proud of. As Ly Son custodians, we need more education on the long-term ramifications and assistance with rubbish management strategies.

Similarly voiced by tourist operator (IP#20), “the domestic waste dumping, coupled with litter discarded directly by tourists, or generated by commercial operators through wider tourism servicing, is threatening the Island”. The accumulative effect of floating and sunken rubbish and untreated effluent discharge from tourism vessels destroys the water quality. Subsequently, marine species’ diversity decays around many developing ports (Chang 2019; Connolly 2019). Such unchecked environmental degradation is likely to worsen without decisive policy intervention (Sroypetch & Caldicott 2018). The current situation in Ly son is harming the local marine environment and adversely affecting the livelihoods of local people through decreased quality and quantity of salable fish stock and the general Island attractiveness for visitors.

Post-2013, and Decision Nos. 201/QD-TTg and 163/QD-UBND, the modernization of Ly Son for tourism developments escalated. A particularly significant event was the Island’s connection to the national power grid in 2014. The Island district government then invested in other tourism enabling infrastructure, including additional electricity distribution, broader roads, new government-sponsored restaurants, and hotels. With the enhanced public utilities, the district government further promotes the Island’s tourism potential in a strengthened effort to attract more businesses investment. Such unbridled ambition exposes the ecological vulnerability giving cause for Island residents and the Island government to confront escalating sustainability issues, not least carrying capacity.

Discussion

Sustainable tourism development means residents’ wellbeing must come first. Unfortunately, in several islands and mainland tourist destinations, the residents now think that tourism performs for tourists at the expense of residents. For example, Chang (2019:1) describes Charting a New Course for Hawaii Tourism as a policy paper that aims “to let lawmakers and the community know about the pressing need to manage better the impact of tourism on the Pacific Aloha State”. As a lesser developed state, Ly Son Island now can learn from and not emulate earlier mistakes made by more extensive and developed island destinations, such as Hawaii and the Cayman Islands.

For example, in the former, Hawaii’s Tourism Association is criticized for overlooking environmental, cultural, and residential issues favouring economic gain (McGough 2021). The latter’s Department of Tourism, clearly concerned that too much development and too many visitors could be self-defeating, sought community input on the draft National Tourism Plan (NTP) 2018–2023 (Cayman Island Department of Tourism 2018; Cayman News 2016). While these developed island nations have a robust indigenous culture, as does Ly Son, to market indigenous culture as an alternative tourism product “can mean walking a fine line between showcasing a Disney-ified past and a true-to-life present” (Clarke 2019:1; Gershon 2021). Instead of such Disneyfication, Palau’s small island state created the Palau Pledge. It holistically promotes responsible tourism with equitable economic, socio-cultural, and environmental goals, emphasizing that tourists are aware of their total ecological footprint (Vogt 2019).

In consideration of all stages of future tourism planning and policy development for the Ly Son community specifically, and to support the Island in its facilitation to national tourism development goals more generally, three resilience thinking forces (see Figure 1) are considered essential:

1) Encourage learning among different actors

Sharing both old and new knowledge and scientific and local practices among the various tourism industry stakeholders is the key to building resilience for sustainable communities. Education is needed to improve Ly Son Islanders’ financial literacy enabling them to participate in business contracts and deals involving government-backed tourism investments. Those who make the deals often keep the money. For tourism benefits to be more equitable and without adverse social and environmental impacts on local lifestyles, Ly Son Islanders need a stronger voice around the national decision-making table. Most importantly, Island residents and business owners should play a more significant role in tourism. Tourism planners could create pathways for Ly Sonders to gain ownership and management of tourism developments through training and funding opportunities.

2) Manage slow variables and feedbacks

Such actions aim to detect critical variables that may cause the ecosystem to breach a threshold and reform into a different structure, i.e., the unchecked extraction of beach sands and accumulative demands for freshwater. Developing governance structures that can responsibly monitor information and respond accordingly is also essential. It is the test of relationships between the State, civil society and the economic interests through which decision-making ultimately steer a society (Börzel & Risse 2005). Subsequently, Ly Son’s future resilience relies on leaders in the government, traditional leaders on the Island, and tourism planners’ ability to harness feedback through a long-term plan for holistic triple-bottom-line (TBL) sustainability guided by traditional values and customs.

3) Broaden stakeholder participations

It is important to note that not all community members participate in making decisions about land use and development priorities in communities. While local village heads are the primary decision-makers for clan lands, district and central governments often have alternative and opposing objectives. This disjunct in policy settings between different scales disrupts traditional values (Caldicott et al. 2014). For example, the Vietnamese central government’s aspiration to expand international visitation continues without considering local populations and infrastructure deficits. If local knowledge and resources are inadequate to support such decision-making, then external (perhaps foreign) experience may provide a helpful supplement. Sroypetch and Caldicott (2018) recommend seeking external professional assistance to complement local knowledge and guide informed decision-making as a positive way to support island community development.

The Ly Son Islanders have already demonstrated, across several centuries, their resilience and capacity to adapt to changed circumstances as the ecological and political environments around them change. However, several paradoxes are acute in the future and beyond sustainability (Graci & Van Vliet 2020). Ly Son does not have its terrestrial and marine activities in balance. On the one hand, garlic is the primary economic driver and an emerging tourism product; on the other hand, its cultivation negatively impacts the environment with a subsequent tourism attractiveness demise. Population increases and tourist visitation to the Island are causing the traditional livelihood system and the natural ecosystem that sustains it to become unstable. In this context, the designation of the ecosystem operating on the Island does not imply sustainability. The Island’s highly unusual garlic fields’ landscape represents the critical selling point of tourism. Still, their continued operation is problematic regarding environmental issues – hence the paradox. Given the lack of any foreseeable subsidies to finance local economic re-orientation to a range of sustainable enterprises, the Islanders are likely to continue the status quo in preference to the path of Sroypetch and Caldicott (2018): ‘monitor forces of change’ and ‘implement remedial actions’.

Preserving natural resources and mitigating the environmental damage from pollution needs to become the ‘new’ consciousness of islanders worldwide. A classic example exhibits the Ly Son short-stop measure of importing mainland sand for agricultural or aesthetic purposes. Rather than treating the cause, the problem may well be transferring environmental and social challenges to mainland supplier communities. Understanding the knowledge gap in the role natural resources play in island tourism and the importance of sustaining and protecting such resources can positively influence how they are used and managed. Consequently, without substantial education, planning, and management of current and necessary changes (Graci & Van Vliet 2020), tourism planning beyond ‘simply growing the numbers’ is not a viable solution for islands.

This study thus uncovers many pressures bearing on islands and their ecosystems. Such pressure may occur first due to internal forces; and second from the island’s geography. In Ly Son’s case, the latter triggers two further external factors of significance: a) the national government’s intent to grow international tourism; and b) its desire to assert a stable and increasing presence in a disputed region. The four factors are envisaged, at a national level, to boost economic and political resilience. However, they manifest as local pressures that endanger ecological viability. Avoiding previously observed presentations from other island communities (see Graci & Van Vliet 2020) requires immediate remedial and ‘resilience thinking’ attention (Sroypetch & Caldicott 2018). Such measures can assist in mitigating changes that international tourism and international politics asserts on local socio-ecological systems.

While acknowledging the seven approaches to resilience thinking, this paper instigates a prioritizing of island communities’ needs and proposes an immediate, though truncated, alignment to three-neglected strands of resilience thinking: encouraging learning; managing slow variables and feedbacks; and, broadening participation. As exhibited in Figure 3, these approaches are considered minimal essentials to injecting resilience thinking beyond the sustainability trilogy into all future tourism planning and policy development for islands.

The study suggests that islands need to develop strategies that reflect operations according to their ecological capacity. Given the potential for environmental impacts from development, any further unfettered degradations will curtail local livelihood activities and quality of life rather than its enhancement (Lew & Cheer 2018). In common with other small and less developed islands, the lack of infrastructure and support for the development of systems concerning access, waste and wastewater management and the protection of the marine environment become barriers to sustainability along with the lack of government support and the need for education and consultation amongst stakeholders (Graci & Van Vliet 2020). Such engagement, inevitably, must transcend local to international boundaries, not least concerning the disputed seas and territorial claims. In fostering solutions, “claimant states cannot escape the need to strike a careful balance between history and present reality of ‘off-island’ sea rights” (Gao & Jia 2013:124).

‘On-Island’, investment in infrastructure, education, capacity building, and leadership is required to overcome the stated issues and implement initiatives to strengthen sustainable tourism in the destination (Gani et al. 2017). In contrast, small-scale niche eco- and gastronomic-tourism experiences that complement island life within the ecological capacity threshold are still viable options for exploration. In the face of current SDGs, ecotourism can potentially resolve some pressing problems. Besides the potential economic benefits of ecotourism, as Weaver (2008) suggests, this type of tourism fosters visitors’ learning experience and appreciation of the natural environment. Island destinations with many natural attractions, such as Ly Son, exhibit many-core ecotourism criteria. Emphasizing nature- and food-based experiences demonstrate care shown to people and the planet, not just (place) profits.

Moreover, islands with well-known or developing gastronomic elements can foster tour packages that combine paddock-to-plate experiences. Several commentators (Dixit & Bristow 2019; Dozier 2012) highlight evidence that gastronomy plays an indispensable role in promoting tourism. In developing gastronomic tourism, Gheorghe et al. (2014:15) suggest tourism strategies can focus on tools to articulate the local product, “their quality, variety, and unique gastronomy” of a territory. Consequently, the formulation of policy and development guidelines that facilitate niche eco-gastronomic tourism products while protecting exceptional natural and cultural environments, is a priority for Ly Son; and an exploratory option for other LDCs.

Conclusion

The World Tourism Organization and Basque Culinary Center (2019) highlight that gastronomy tourism forms an integral part of a territory’s local life. It bears the natural potential to preserve the society while enriching “the visitor experience through establishing a direct connection to the region, its people, culture, and heritage” (6). Such a focus can also shift the Island’s positioning from a domestic festival playground to a niche international acclaim with world-renowned environmental and culinary practices. Such ‘positioning’ changes will allow islands to develop resilient tourist destinations with sustainable futures.

However, adapting to change is usually confronting. Notwithstanding, ignoring the ‘slow accumulation’ pressures on islanders’ livelihoods in any location is perilous. Subsequently, recommendations are for decisive interventions to tourism planning and policy thinking. For small islands, factors impeding resilience are the industry’s management deficiencies, inadequate cohesion among stakeholders, and lack of innovation (Bangwayo-Skeete & Skeete 2020). Hence, responses are preferred not solely directed by national governments but more developed through solid community engagement. Weaver (2017) concurs resolution-based dialectics allow the positive elements of both core and periphery to be identified and combined towards achieving the ideal of resilient tourism communities.

As the Covid-19 pandemic brings a greater emphasis on personal health priorities, gastronomic experiences, such as vegan tourism, is poised for a new wave of growth once people begin travelling again (Rashaad 2021). As governments worldwide seek to revitalize their hard-hit tourism industry and go full circle, the UNWTO (2020) re-advocates gastronomy to have a critical role in enriching the tourism offer and stimulating economic development. The global agency suggests gastronomy is about much more than food. It is emerging as an essential protector of cultural heritage, with the sector helping create opportunities, including jobs, most notably in rural destinations. However, as it stands, “we are using our lands, soils, oceans, and forests in largely unsustainable ways” (UNWTO 2020:1). Subsequently, governments, communities and consumers need to be more careful about using natural resources for production and sensitive about the food chosen for consumption.

In support of such global SDG goals, this study’s findings contribute to the theoretical literature by critically overlaying the sustainability trilogy indicators (economic, socio-cultural and environmental) with three resilience thinking measures. This approach can support island communities, beyond Ly Son, in their further phases of tourism destination planning, policymaking, and practice orientation.

The pragmatic practice implications extend to guiding political and national strategic thinking beyond economic imperatives to retain indigenous culture’s core values and pristine environments. Both require consideration as equals necessary in a balanced social-ecological system. Non-sustainable tourism development brought on by unintended economic and political interventions is not the way to build island capacities. Instead, restoring the equilibrium between environment, culture and economics will bring back and strengthen island, and islanders, resilience against future internal and external shocks.

Echoing New Zealand’s lead, “…when you start looking beyond simple cost-benefit analysis and look at the cost-benefit of human welfare, then you make record investments” (McCarthy 2019:1). By unlocking human potential and growing resilient island communities, indigenous lives and livelihoods will benefit from tourism and tourism practice will contribute to planet conservation. Tourism businesses have found such food-based excursions have a much more significant benefit for the planet than just stuffing people’s stomachs. According to Rashaad (2021:1), well-run tours “can support local communities and benefit the environment”. As Rastegar (2019) reminds, residents’ attitudes can significantly impact the success of tourism development and environmental protection. The three streams of the resilience thinking framework is demonstrably a valuable but flexible tool to analyse wide-ranging variables that determine and shape resident attitudes toward their tourism future. It serves to facilitate the advancement of resilient communities on tourism islands.

While the three ‘streams of resilience’ thinking propositions presented within may be Ly Son explicit, the framework is readily adaptable to many island communities, more implicitly to less developed countries (LDCs). As Hall (2019, 1044) echoed, fundamentally, “there is a need to rethink human-environment relations given the mistaken belief that the exertion of more effort and greater efficiency will alone solve sustainable tourism problems”. According to Reed (2007), shifting from a fragmented worldview to a whole systems mental model is the significant leap our culture must make — “framing and understanding living system interrelationships in an integrated way” (674). Subsequently, and poignantly, in a post-Covid-19 transition, further in-practice engagement is required with the Ly Son community to facilitate a fully monitored resilience thinking program with clear and transparent feedback loops and test the framework across a broader spectrum of island communities.

Endnotes

References

- Bangkok Post 2012, Vietnam, China in new spat over fishermen detentions, Bangkok Post, viewed 12 September, https://www.bangkokpost.com/world/285546/vietnam-china-in-new-spat-over-fishermen-detentions.

- Bangwayo-Skeete, PF & Skeete, RW 2020, ‘Modelling tourism resilience in small island states: a tale of two countries’, Tourism Geographies, pp. 1–22, 10.1080/14616688.2020.1750684.

- Bautista, L 2018, ‘The South China Sea arbitral award: evolving post‐arbitration strategies, implications and challenges’, Asia Politics and Policy, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 178–89, 10.1111/aspp.12398.

- Blix, BH 2015, ‘“Something decent to wear”: performances of being an insider and an outsider in indigenous research’, Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 175–83, 10.1177/1077800414542702.

- Börzel, T & Risse, T 2005, ‘Public-private partnerships: effective and legitimate tools of international governance’, in E Grande & L Pauly, W (eds), Complex Sovereignty. Reconstituting Political Authority in the Twenty-First Century, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, pp. 195–216.

- Boschma, R 2015, ‘Towards an evolutionary perspective on regional resilience’, Regional Studies, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 733–51.

- Boykoff, P 2016, Vietnam fishermen on the front lines of South China Sea fray, Cable News Network (CNN), viewed 14 December, https://edition.cnn.com/2016/05/22/asia/vietnam-fisherman-south-china-sea/index.html.

- Bramwell, B 1994, ‘Rural tourism and sustainable rural tourism’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, vol. 2, no. 1–2, pp. 1–6, 10.1080/09669589409510679.

- Butler, R 2015, ‘Sustainable tourism–the undefinable and unachievable pursued by the unrealistic’, in TV Singh (ed.), Challenges in Tourism Research, Channel View, Bristol, UK, vol. 70, pp. 234–40.

- Butler, R 2018, ‘Sustainable tourism in sensitive in environments: a wolf in sheep’s clothing?’, Sustainability, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 1–11.

- Butler, RW 1980, ‘The concept of a tourist area life cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources’, Canadian Geographer, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 5–12, 10.1111/j.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.x.

- Caldicott, RW, Jenkins, JM & Scherrer, P 2017, ‘The politics of freedom camping policy in Australian communities: understanding the “other” through a taxonomy of caravanning’, paper presented to Institute of Australian Geographers, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 4–9 June.

- Caldicott, RW, Scherrer, P & Jenkins, J 2014, ‘Freedom camping in Australia: current status, key stakeholders and political debate’, Annals of Leisure Research, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 417–42.

- Carlson, RR, Foo, SA & Asner, GP 2019, ‘Land use impacts on coral reef health: a ridge-to-reef perspective’, Frontiers in Marine Science, vol. 6, no. 562, 10.3389/fmars.2019.00562.

- Carpenter, S, Walker, B, Anderies, JM & Abel, N 2001, ‘From metaphor to measurement: resilience of what to do what?’, Ecosystems, vol. 4, pp. 765–81, 10.1007/s10021-001-0045-9.

- Cayman Island Department of Tourism 2018, National tourism plan seeks public consultation, Department of Tourism, viewed 10 October, https://www.visitcaymanislands.com/en-us/ourcayman/news/2018/august/national-tourism-plan-seeks-public-consultation.

- Cayman News 2016, Over-development undermining tourism, CNS Business, viewed 8 June, https://cnsbusiness.com/2016/06/01/over-development-undermining-tourism/.

- Chang, H 2019, In danger of being overrun, some places are trying to manage tourism. Here’s how, Los Angeles Times, viewed 8 October, https://www.latimes.com/travel/story/2019-08-09/overtourism-hawaii-italy-amsterdam.

- Chen, F, Xu, H & Lew, AA 2020, ‘Livelihood resilience in tourism communities: the role of human agency’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 606–24, 10.1080/09669582.2019.1694029.

- Clarke, K 2019, We’re not here to Disney-ify the culture: the challenges of marketing Indigenous tourism, The Hamilton Spectator, viewed 8 October, https://www.thespec.com/news/hamilton-region/2019/10/07/we-re-not-here-to-disney-ify-the-culture-the-challenges-of-marketing-indigenous-tourism.html.

- Connolly, K 2019, A rising tide: ‘overtourism’ and the curse of the cruise ships, The Guardian, viewed 11 October, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/sep/16/a-rising-tide-overtourism-and-the-curse-of-the-cruise-ships.

- Dixit, SK & Bristow, RS 2019, ‘The Routledge handbook of gastronomic tourism’, Tourism Culture & Communication, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 63–4.

- Dozier, B 2012, Gastronomy tourism trend in Australia, Barbra Dozier Blog, viewed 30 December, https://barbradozier.wordpress.com/2012/02/20/gastronomy-tourism-trend-in-australia/.

- Elkington, J 1994, ‘Towards the sustainable corporation: win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development’, California Management Review, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 90–100, 10.2307/41165746.

- Fennell, DA 2008, ‘Responsible tourism: a Kierkegaardian interpretation’, Tourism Recreation Research, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 3–12, 10.1080/02508281.2008.11081285.

- Gani, AA, Awang, KW & Mohamad, A 2017, ‘Exploring the public participation practices in planning for sustainable tourism in Malaysia’, in A Saufi, I Andilolo, N Othman & A Lew (eds), Balancing development and sustainability in tourism destinations, Singapore, pp. 211–9.

- Gao, Z & Jia, BB 2013, ‘The nine-dash line in the South China Sea: history, status, and implications’, The American Journal of International Law, vol. 107, no. 1, pp. 98–123, 10.5305/amerjintelaw.107.1.0098.

- Gershon, L 2021, Disney will remove jungle cruise ride’s colonialist depictions of indigenous Africans, smithsonianmag.com, viewed 16 February, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/disney-overhauls-jungle-cruise-ride-over-racism-180976841/.

- Gheorghe, G, Tudorache, P & Nistoreanu, P 2014, ‘Gastronomic tourism, a new trend for contemporary tourism??’, Cactus Tourism, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 12–21.

- Girardet, H 2013, Sustainability is unhelpful: we need to think about regeneration, The Guardian, viewed 27 April, https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/blog/sustainability-unhelpful-think-regeneration.

- Gittins, R 2019, Change is inevitable. If we embrace it we win; resist it, we lose, Sydney Morning Herald, viewed 23 July, https://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/change-is-inevitable-if-we-embrace-it-we-win-resist-it-we-lose-20190718-p528l8.html.

- Goodwin, H 2011, Taking responsibility for tourism, Goodfellow, Oxford, UK.

- Gossling, S (ed.) 2003, Tourism and development in tropical islands: political ecology perspectives, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK.

- Gössling, S 2021, ‘Tourism, technology and ICT: a critical review of affordances and concessions’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 733–50, 10.1080/09669582.2021.1873353.

- Graci, S & Van Vliet, L 2020, ‘Examining stakeholder perceptions towards sustainable tourism in an island destination. the case of Savusavu, Fiji’, Tourism Planning & Development, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 62–81, 10.1080/21568316.2019.1657933.

- Gunderson, L 2001, ‘Panarchy’, in J Sven Erik & F Brian (eds), Encyclopedia of Ecology, Academic Press, Oxford, pp. 2634–8, 10.1016/b978-008045405-4.00695-9.

- Hall, CM 2016, ‘Putting ecological thinking back into disaster ecology and response to natural disasters: rethinking resilience or business as usual?’, in CM Hall, S Malinen, R Vosslamber & R Wordswoth (eds), Post-disaster management: business, organisational, consumer resilience and the Christchurch earthquakes, Routledge, Abington, UK.

- Hall, CM & Mitchell, R 2001, ‘Wine and food tourism’, in NDR Derrett (ed.), Special Interest Tourism, John Wiley, Brisbane, Qld Australia, pp. 307–25.

- Ho Huy Cuong 2009, Research on restoration of Ly Son garlic (In Vietnamese: Nghien cuu phuc trang giong toi o Ly Son), Agricultural Science Institute for Southern Coastal Central of Vietnam (ASISOV), Binh Dinh, Vietnam.

- Holling, CS 1973, ‘Resilience and stability of ecological systems’, Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, vol. 4, pp. 1–23.

- Hutchby, I & Wooffitt, R 2008, Conversation analysis, Polity Press, Cambridge, UK.

- James, L & Halkier, H 2016, ‘Regional development platforms and related variety: exploring the changing practices of food tourism in North Jutland, Denmark’, European Urban and Regional Studies, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 831–47, 10.1177/0969776414557293.

- Jenner, CJ & Tran Truong, T (eds) 2018, The South China Sea: a crucible of regional cooperation or conflict-making sovereignty claims?, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Kim, S & Jamal, T 2015, ‘The co-evolution of rural tourism and sustainable rural development in Hongdong, Korea: complexity, conflict and local response’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, vol. 23, no. 8–9, pp. 1363–85, 10.1080/09669582.2015.1022181.

- Kokkranikal, J & Baum, T 2010, ‘Tourism and sustainability in the Lakshadweep Islands’, in J Carlsen & R Butler (eds), Island Tourism: Sustainable Perspectives CABI, Cambridge, pp. 1–7.

- Lam, MC 2020, ‘Fishers, monks and cadres: navigating state, religion and the South China Sea in Central Vietnam’, Journal Contemporary Asia, pp. 1–3, 10.1080/00472336.2020.1858442.

- Lau, M 2020, China says Vietnamese fishing boat rammed coastguard ship before sinking, South China Morning Post, viewed 12 September, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3078452/china-says-vietnamese-fishing-boat-rammed-coastguard-ship.

- Lee, K-H, Packer, J & Scott, N 2015, ‘Travel lifestyle preferences and destination activity choices of Slow Food members and non-members’, Tourism Management, vol. 46, pp. 1–10, 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.05.008.

- Lerch, D 2015, Six foundations for building community resilience, Post Carabon Institute, viewed 8 July 2017, http://www.postcarbon.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Six-Foundations-for-Building-Community-Resilience.pdf.

- Lew, A 2014, ‘Scale, change, and resilience in community planning’, Tourism Geographies, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 14–22, 10.1080/14616688.2013.864325.

- Lew, AA & Cheer, J 2018, ‘Lessons learned: globalization, change, and resilience in tourism communities’, in J Cheer & AA Lew (eds), Tourism, Resilience, and Sustainability: Adapting to Social, Political and Economic Change, Routledge, London, UK, pp. 319–23.

- Lew, AA, Ng, PT, Ni, C-c & Wu, T-c 2016, ‘Community sustainability and resilience: similarities, differences and indicators’, Tourism Geographies, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 18–27, 10.1080/14616688.2015.1122664.

- 2015, Decision on approving a Tourism master development plan to 2020 with a vision to 2025 for Ly Son Island (In Vietnamese: Phe duyet quy hoach phat trien du lich dao Ly Son) [No. 163/QD-UBND, dated June 3], by Ly Son District Government.