Changes and Chaos in Islands and Seascapes: In Perspective of Climate, Ecosystem and Islandness

Abstract

Besides the great burden that has been placed on the world by the COVID-19 pandemic, radical climate change is causing natural disasters in every corner of the world. According to the IPCC’s most recent report, rising global temperatures already have very negative impacts beyond our expectation. The main cause of this lies in human activities that drive global population growth, ongoing urbanization, excessive use of natural resources, and so on. Every minute, the environment in islands and oceans is changing in different directions and angles. This forum is to have an in-depth discussion on how climate crisis including pandemic and climate change and sprawling development by humans etc., can affect cultures and ecosystem in islands and seascapes and which direction identity of islands will be heading in the future. For this matter, the theme of this forum is fixed as “Changes and Chaos in Islands and Seascapes”.

Keywords

climate change, COVID-19, ecosystem, islandness, island culture, pandemic, seascape

Introduction: Climate and islandness

The 8th East Asian Island and Ocean Forum (EAIOF) was held at the Institution for Marine and Island Cultures (IMIC) at Mokpo National University on 11th Dec, 2021. The main theme was ‘Changes and Chaos in Islands and Seascapes’, the agenda for the humanities of the island. The forum was held under the themes of Part 1 Changes in Marine Culture and Islandness, Part 2 Coexistence of Nature and Humans, Part 3 Island and Communities on the Border, and Part 4 Sustainable Tourism and Contents (see Appendix).

Climate change is a phenomenon that has raised increasing awareness as it is becoming more severe and its effects more obvious. Residents living in coastal areas have to keep an eye on recent sea-level rises as it threatens the livelihood of many of them (Pittman, 2017). The second part of the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the United Nations (UN) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), published under the title “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation & Vulnerability”, gives a dire warning (IPCC AR6, 2022). The report states that, in spite of the efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions declared in the 2015 Paris Climate agreement, it is estimated that a 1.5℃ global temperature rise will already be reached in 2040, 10 years earlier than as anticipated in the 2015 standard. Moreover, the report points to an increase in the IPCC’s projection of the earth’s average sea-level rise. Whereas in the 2013 Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC AR5, 2013) it was expected to reach 0.19m, the updated estimate is 0.20m. If this continued at this pace, the earth’s average sea-level rise would reach 0.28~1.01m by the end of the current century, implying for example the submergence of Venice in Italy. The Korean Hydrographic and Oceanographic Agency operating under the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries analyzed the coastal tide station data of the last 30 years (1989~2018) and concluded that South Korea’s annual sea-level rise was 2.97mm. However, this number might become higher given the IPCC’s projections in its AR6 (IPCC AR6, 2022).

Islands present themselves in different ways based on how human activities make use of the various resources available in the natural ecosystem and how the overall lifestyle of island communities has taken form. This coins the concept of islandness which draws attention to the attributes of an island affecting its community and culture (Philip and Jonathan, 2017; Hong, 2022b). Researchers studying islands are always aware of the identity and insularity of islands.

According to the definition of islandness given in Conkling (2007), the perception of islands is basically based on the concept of ‘Insularity’ which in turn is based on ‘Isolation’. The concept of islands has been long perceived as that of a small landmass surrounded by seawater and existing as an isolated form in the open sea (Conkling, 2007). However, perceptions have changed after western countries started to actively discuss the multifaceted identity of islands. Aspects such as the geography, traffic and governance of islands and their socioeconomic stands have already overcome the physical limitation of isolation (Jackson, 2008). Moreover, the perspectives on islands have change rapidly due to globalization and urbanization.

Islands are places of isolation but, at the same time, they are gates that lead to the open sea (Hong, 2022a). “Islandness1 is a metaphysical sensation that derives from the heightened experience that accompanies physical isolation (Conkling, 2007).” The perception and view regarding ‘placeness’ (a sense of place) has become an important direction point to define ‘Humanities Topography’2. To organize physical, psychological and perceptional phenomena for existence, life, place, vitality and changes in islands, it is necessary to give shape to islands in both tangible and intangible forms and structures.

Our research direction is to grasp the interactions between the daily lives of islanders and their surrounding environment in a macroscopic and diachronic view on the use of resources in islands and seas. Understanding islandness is key to organize the existence and life in islands, space, vitality and changes in physical, psychological and perceptional phenomena and to study overall change in islands in giving shape and restructuring tangible and intangible forms and structures.

Island vegetation and changes in forest culture

Since South Korea is a peninsular country surrounded by the sea on three sides, it not only shows many climatic attributes of the contact between continent and ocean but also significant climatic characteristics. Compared to the more northern located Seoul-Incheon metropolitan area and Gangwondo Province that are strongly impacted by Siberian northwestern wind in midwinter, the southern part of the country experiences higher temperatures due to a warm oceanic climate. These climatic variations, as well as differences that exist at a more local scale, result in the formation of unique ecosystems and vegetation cultures in different regions along the coastline.

Vegetation in the Korean peninsula is classified into three zones: evergreen forest zone, deciduous forest zone and mixed forest zone. Island areas in the southwestern sea and the southern sea, which have relatively warm oceanic climates, can be defined as warm temperature vegetation zones where many evergreen plants are distributed. According to Burrows (1990), vegetation is defined as ‘a collection of all kinds of plants on earth’. Vegetation exists in great variety on earth since it depends on local climates and soils.

Therefore, by observing vegetation types and their distribution characteristics in a particular region, we can indirectly get an understanding of the climate conditions and soil properties in that region. Plants in rivers, in grasslands, in coastal sand dunes, and other landscapes are all vegetation. In terms of biochemistry, vegetation transfers solar energy into biomass and forms the basis of all food chains in natural ecosystems. Since vegetation impacts the energy balance between the surface of the earth and its own atmospheric boundary layer, it plays an important role in climate regulation. Furthermore, vegetation provides habitats and food for wildlife and socio-economic-environmental services for humans, both directly (e.g., lumber) and indirectly (e.g., watershed protection). In forest ecosystems, vegetation can also slow down the velocity of rivers, which can help mitigate the erosion of soil and prevent landslides.

Vegetation provides spiritual, cultural and aesthetic experiences to people. More practically, it also provides people with resources necessary for living, such as food, cellulose, shelter, medicine and fuel. These kind of natural resources utilizable to humans are produced in the metabolic process of green plants, which also generates oxygen that people need to live. As plant roots grow, mechanical and chemical weathering of rocks and roads occurs causing cracks. Vegetation is helpful for slowing down the flow of water, reducing soil erosion, and reducing the amount of pollutants ending up in waterways. Overall, vegetation is closely related to human beings’ lives.

Vegetation may differ depending on where it is located, either in coastal areas, islands, or inland. Vegetation in Namhae-Gun in Gyeongsangnam-Do Province (Gun and Do correspond to each County and Province) and Wando-gun, Goheung-Gun and Yeosu-si in Jeollanam-do Province (‘si’ corresponds to City) is mostly evergreen broad-leaved forest. In coastal areas, trees are often intentionally planted to form windbreak forests, while in the mostly mountainous inland areas evergreen broad-leaved forests have formed naturally in vegetation communities with tall-tree species like Castanopsis sieboldii, Quercus acuta, Machilus thunbergii, Neolitsea sericea and Camellia japonica mixed with shrub-layer tree species such as Eurya emarginata and Pittosporum tobira.

Also, evergreen broad-leaved trees can be found mixed together with Pinus densiflora (red pine) or Pinus thunbergii (black pine) depending on altitude and slopes. Vegetation in Heuksando island and Hongdo Island is dominated by evergreen broad-leaved trees but in some places communities of pine trees can be found depending on altitude and slopes. Except for Heuksando and Hongdo, islands in Sinan-gun have vegetation that is classified as secondary forest with mixtures of Pinus rigida (pitch pine) and Pinus thunbergii (black pine). The plantation activities, which have been going on for about 30 to 40 years, have already begun to be supplemented by various plant species through natural succession.

Among broad-leaved trees, especially oak species are considered good materials to make coals. It is known that Mongolian oak and other oak trees were used to make coals in central districts such as Gangwon-do Province, Chungcheongbuk-do Province and Northern Gyeonggi-do Province. However, also traces of several charcoal kilns can be found in deep forest in Gageodo island, Heuksan-myeon, Sinan-gun, Jeollanam-do. According to its residents, charcoal was made and sold on this island during the Japanese colonial period.

In Japan, coppices are seen as the general source to make charcoals. Most of the time, deciduous broadleaf tree such as Quercus accutissima, Quercus serrata, Prunus sargentii and Celtis sinensis were used for this purpose. However, in Kyushu and islands surrounding this region in Japan, sometimes evergreen broad-leaved trees such as Quercus myrsinaefolia were used as the source for charcoals. In South Korea, evergreen broad-leaved trees, including evergreen oak trees such as Quercus acuta and Quercus glauca, are mostly found in Sinan-gun, Jeollanam-do Province. These trees were known to be used for charcoals.

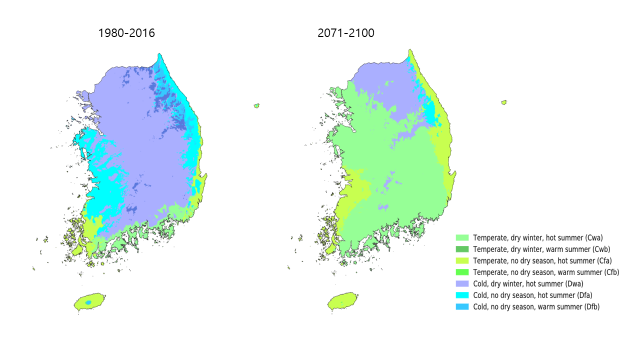

According to the AR6 report (IPCC AR6, 2022), the speed at which the global average temperature is expected to rise by 1.5℃ is faster than originally anticipated as it is expected to reach this level by 2040. According to the Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for South Korea (Figure 1), the warm temperature front is expected to move further north and have passed the central region by the last quarter of the 21st century (Beck et al., 2018).

When we bring Korean vegetation into this projection, it is clear that broad-leaved trees dominating in the central region will move up north and reach all the way to the lowlands of the central region. Furthermore, in areas where we can still find mixed forests with evergreen broad-leaved trees and pine trees together, forests are expected to change into only evergreen forest. In the southern Jeollanam-do Province, the inflow of subtropical plants will make vegetation communities particularly different from present times.

In their report on the changes in vegetation in Heuksando island, Sinan-gun due to climate change, Cho & Kim (2018) expressed the expectation that, within 10 to 20 years, the distribution of Castanopsis sieboldii, Machilus thunbergii, and Quercus acuta will increase in areas with evergreen broad-leaved trees and pine trees (Pinus thunbergii and Pinus densiflora) as dominant communities or mixed forests, leading to an increasing distribution of Castanopsis sieboldii communities and Machilus thunbergii communities in the end. Characteristics of vegetation can differ depending on two major factors: a natural factor and an anthropogenic factor. Unlike urban vegetation, island vegetation is mostly untouched and strongly affected by climate change. A change in vegetation structure affects the biological diversity of animal species, such as the birds, mammals and insects living in an island. With the expectation of the climate becoming subtropical, the question is what will the lives of islanders in Jeollanam-do Province be like in 30~40 years? Terrestrial ecosystems may change slowly compared to marine ecosystems and fishing-grounded environments due to climate change, but still the effects are likely to become visible sooner than we hope.

(Beck, H.E., Zimmermann, N. E., McVicar, T. R., Vergopolan, N., Berg, A., & Wood, E. F. — "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Nature Scientific Data.DOI: 10.1038/sdata.2018.214.)

Changes in seaweed ecosystems and livelihood

Climate change is affecting our lives deeply. Natural disasters caused by climate change are becoming more frequent and also the damage they cause is increasing. The Korean Peninsula is exposed to various natural disasters, such as sea-level rise, typhoons, droughts, and floods. In particular, this can wreak havoc on people who make a living in coastal areas. The location and size of fishery areas and the diversity of fish are changing, and also coastal ecosystems utilized for seaweed harvesting and aquaculture are changing rapidly (Kim, 2019).

Recently, satellite images taken by NASA around Sisando island, Goheung County, Jeollanamdo Province, put a lot of attention on the local islanders (Figure 2). The massive scale of their aqua-farms for Saccharina japonica (Laminaria japonica J.E. Areschoug; kelp) and Undaria pinnatifida (sea mustard) play a role that is as important as that of paddy fields on land. Especially, the seaweed farms inhale carbon dioxide and exhale oxygen, which positively impacts global warming.

| Year | Production (M/T) | Price (Thousand Won) |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 1,007,070 | 401,109,401 |

| 2012 | 1,032,450 | 455,456,644 |

| 2013 | 1,139,871 | 457,000,127 |

| 2014 | 1,096,786 | 506,033,392 |

| 2015 | 1,212,690 | 510,267,956 |

| 2016 | 1,395,373 | 661,527,875 |

| 2017 | 1,769,698 | 879,405,282 |

| 2018 | 1,721,821 | 867,124,374 |

| 2019 | 1,851,224 | 891,021,679 |

| 2020 | 1,769,040 | 773,592,063 |

Korea has seasonal and various seafood products and it has accumulated a traditional know-how of recipes based on those products (Table 1; Laver, Gracilarias, Gracilariopsis, chorda, Tangle, Gambling, Sargassum sp., Sargassum fulvellum, Sea mustard, Agar seaweed, Sea staghorn, Hijikia, Green algaes, Seaweed fulvescens, Other seaweeds). The Korean culture considers food to be not only for satisfying hunger but also for maintaining health. This lifestyle attitude towards food has a long history and it is still embedded in the daily life of its people (Kim, 2019). If there is a change in the types of fish being caught, this will impact not only the shape and type of fishing boats but also the availability of food ingredients, which in turn will ask for the adjustment or abandonment of traditional recipes.

Aquafarming (or aquaculture) of seaweed such as Gelidium amansil is not very common. There are just a few seaweed aqua-farms but none for Gelidium amansil. If habitats for seaweeds like this are disappearing due to climate change, access to food that is common today will soon no longer exist in the country. As such, it is obvious that as climate change worsens, people will undergo unprecedented changes in their daily lives. If changes are gradual and not so strong, there would be time for people to adjust to it, but if not, the impact and ripple effect of climate change would reveal itself rather abruptly.

Changing islands, traditional knowledge and islandness

Ecological functions and socioeconomic roles of forests are not only very important subjects in ecology (including forestry). They also play an important role in taking an eco-cultural view on human day-life. They are crucial aspects when discussing proper conservation and use of forests in the context of improving the relations between utilization and restoration of forest ecosystems (Hong, 2022b). For example, coastal forests play a role not only as windbreak forests but also as a traditionally important ecological resource by providing timbers necessary to build a boat for fishermen. Moreover, windbreak forests have also had a traditional ecological function as sacred ritual places for villages. Whether forests in islands these days play a traditional role as they used to do in the past remains a question.

Urbanization of islands often takes place fast. In general, an island that gets connected to the mainland and other islands is likely to experience an increase in the number of tourists because of the improved connectivity. At the same time, the better connections make that more and more islanders commute to neighboring cities.

Except for some islands where natural succession was enabled to play a role in forming vegetation zones and ecosystems, most island vegetation in Korea consists of planted forests. There has been an impact on vegetation due to various cultural activities that involve forest use. Especially, as more tourists visit an island, more cultural forest resources (e.g. fisherman’s forest, windbreak forest, old giant tree etc.) that were traditionally preserved are transformed and no longer used for their original purpose.

Changes in islandness begin with the change in the lives of the people who use island resources and come into contact with the space (Conkling, 2007). How to use forest resources differs from that in the past and, as the sacredness of islands and the eco-cultural property of island wonder disappears, the identity of islands changes. Windbreak forests to prevent harm from tsunamis and storms in coastal villages in the past now have become seawalls. Likewise, sacred forests where rituals for a big catch festival were performed have become deserted places.

Black pine (Pinus thunbergii) and also tall trees such as sawleaf zelkova (Zelkova serrata), hackberry (Celtis sinensis) and camphor trees (Cinnamomum camphora) were often traditionally planted in island villages, but now they are surrounded by unknown exotic plants and degraded into elements of a recreational garden. The prototype of the forest, which contained the traditional knowledge of the islanders in the past, is gradually disappearing, and the island’s ecological culture, which has maintained its own uniqueness and independence, is being standardized in the direction of urbanization. Changes in island ecosystems due to development come fast and have serious impacts. It is warranted to state that development is another threat to islands and islandness besides the threat already posed by climate change.

Closing

In a spatiotemporal perspective, natural vegetation changes depending on climate and soil. However, recent developments in islands show that changes in vegetation can take place rapidly, even at a faster rate than expected due to climate change. The formation of large-scale parks and the introduction of exotic ornamental plants are often in the opposite direction compared to the structures of the vegetation community and biodiversity seen in changes caused by natural succession like ‘ecological miracles’.

This kind of island development, against the background of recent sudden extreme weather events and seasonal uncertainty in the flow of changing island ecosystems in the oceanic climate zone that surrounds the Southwest Sea, is worsening island vulnerability.

This increase in ‘island vulnerability’ threatens both island culture and islandness, which have been closely connected to the traditional use of forests to adapt to the climate (Campbell, 2019). Islandness is formed and transformed from a ‘sense of place’, a space of activity for the islanders’ lives, livelihoods and rituals (Jackson, 2008; Philip & Jonathan 2017).

Island vegetation is a unique natural resource representing the social-economic-environmental capital of an island and also reflecting the ‘sense of place of islanders’ who have preserved that vegetation. The phenomenon of ‘changing islandness’ is the phenomenon that the now-fading island’s sacred forests, fishermen’s forests, and various other vegetation uses are gradually disappearing amid disturbances caused by tourism, urbanization, or general neglect in vegetation management.

According to the results of the National Marine Ecosystem Comprehensive Survey, released by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries in 2020, rising sea temperatures make marine animals move their habitat northwards (The Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, 2020). In the East Sea, the average annual water temperature was 16℃ in 1970 but increased to 17.2℃ in 2017. Such temperature rises undoubtedly lead to decreasing numbers of cold-water species and increasing numbers of warm-water species, according to changing currents. As the location and size of fishery activities change and species keep changing, this strongly impacts the movement of fishermen and the amount of fish they catch.

Our daily lives are changing more rapidly than we know, but everything including humans has its own capacity to manage and deal with changes. For instance, humans have indigestion when they eat more than they can digest, and this could make them want to find a digestive medicine. Luckily, if they find an effective medicine, they don’t have to suffer for long and they can recover quickly. However, if they do not have or cannot find an effective medicine, they have to endure the indigestion. Similarly, in the light of climate change, it is necessary to start with small efforts so that our daily lives are not changed to the extent that it becomes painful due to the climate crisis. Earth is an essential element for human survival. Let’s keep in mind that human beings need the Earth to survive, but the Earth doesn’t necessarily need human beings.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Humanities Korea Plus (HK+) Project of the National Research Foundation of Korea (2020S1A6A3A01109908).

Endnotes

References

- Beck, H.E., Zimmermann, N.E., McVicar, T.R., Vergopolan, N., Berg, A., & Wood, E.F. Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Nature Scientific Data. DOI: 10.1038/sdata.2018.214.

- Burrows, C.J. 1990. The nature of vegetation and kinds of vegetation change. In: Processes of Vegetation Change. Springer. pp.1-22.

- Campbell, J. 2019. Islandness-Vulnerability and Resilience in Oceania. Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures. 3(1), 85-97.

- Cho, Y.-J. Cho and H.-S. Kim. 2018. A Study on the Vegetation Succession of Daeheuksan Island. Journal of National Park Research, 9(3), pp. 352-364.

- Conkling, P. 2007. On Islanders and Islandness. Geographical Review 97(2): 191-201.

- Hong, S.J. 2022. Change and chaos of social composition and identity of port city culture as multicultural: Focusing on the cases of Malacca and Mokpo. In: 2021 Presentation materials for the Multicultural Symposium on Strengthening Coexistence Capabilities (25th Jan. 2022, Asan Research Institute, Soon Chun Hyang University.

- Hong, S.K. 2022a. Tropical Islandness. Mokpo: Publisher Seom (Korean), pp. 8-14.

- Hong, S.K. 2022b. Changes in the Island Humanistic Topography and the Island Identity due to Global Environmental Changes: Focused on the Ecological-cultural Background and Methodology. Cultural Exchange and Multicultural Education, 11(2): 417-441. DOI: 10.30974/kaice.2022.11.2.17.

- Institution for Marine and Island Cultures, 2020. Island Humanities; Change of Humanities Topography, and Sustainability. HK+2 Type Basic Humanities Research Plan. National Research Foundation.

- IPCC AR6, 2022. Climate Change 2021: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. (https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-ii/)

- IPCC AR5, 2013. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/).

- Jackson, R.E. 2008. Islands on the Edge: Exploring Islandness and Development in Four Australian Case Studies. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Tasmania.

- Kim, J.E. 2019. Traditional ecological knowledge and sustainability of ecosystem services on islands: A case study of Shinan County, Jeollanamdo, Republic of Korea. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 8(1), pp.28-35.

- Merli, P. 2010. Antonio Gramsci, Prison notebooks, International Journal of Cultural Policy, 16(1), 53-55, DOI: 10.1080/10286630902971603

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, 2020. National Marine Ecosystem Comprehensive Survey.

- Philip V. & Jonathan T. 2017. Doing islandness: a non-representational approach to an island’s sense of place. Cultural Geographies 20(2): 225-242.

- Pittman, S. J. 2017. Seascape Ecology. Wiley. 528p.