Commodifying Culture In A Frontier Area: The Utilization of Madurese Culture for Developing Tourism in the Eastern Tip of Java Island, Indonesia

Abstract

This study aimed to analyze the reasons that the Regent of Bondowoso chose Madurese culture to be a tourist destination for Bondowoso Regency, and the impact of the commodification of Madurese culture on the welfare of the Bondowoso community. The theory of commodification and historical method were used in this study. The primary data were collected through participatory observation, interview, and colonial sources (documentation), while secondary data were collected from various sources which include published works, results of related studies, and related government reports. The population was the Madurese community in Bondowoso Regency. The results of the study had proven that Madurese Culture like Kerapan Sapi and Sapi Sonok (cow’s beauty contest) had been contesting in front of the public since the Dutch colonial period, while Ronteg Singo Ulung, Pojien Dance and Petik Kopi ritual had been used as tourism commodities in Bondowoso Regency since 2017. In this importance, the Regent of Bondowoso chose Madurese culture as a lure for tourists; both domestic and foreign tourists. This action was to improve the welfare of the community, as well as generating revenue for the Regional Government and Village Government.

Keywords

Madurese Culture, Commodification, History, Civilization, Heritage, Culture

Introduction

The Covid-19 outbreak that hit the world, has not lessened the enthusiasm of broad countries to improve and continue to develop tourism sector. Tourism is a major asset that supports the economic sector and contribute 9% of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In the past few years, there has been a significant growth which is expected to continue, particularly in developing countries where visitor arrivals are increasing far beyond the world average. Tourism has contributed 29% of worldwide service exports and for many developing countries. It provides a significant source of foreign exchange, and has become a major source. Some studies have confirmed the contribution of this sector to economic growth and many international bodies, convention and communication have formally recognized the importance of the sector as a driver for sustainable development. The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) has predicted that the growth-trend in world tourism will continue with total arrivals reaching for 1.8 billion in 2030. Here, developing countries are among the countries that will experience the highest growth rates (UNWTO 2019).

Countries in the world have competed one another to offer their country's tourist destinations to foreign tourists. Each country offers a unique culture, geographic condition, and natural resources. As an illustration of the various efforts of a country to generate foreign exchange for its economic growth, namely: British Columbia which offers a unique Aboriginal culture (Thimm 2019), Ecuador with its unique Kichwa Anangu community who dedicates the life to the tourist destination of the country (Renkert 2019), Social resources owned by Bidayuh indigenous communities in Malaysia as a tool to attract tourists (Johari and Kunasekaran 2019), India which offers the City of Kolkata and Darjeeling to foreign tourists, especially from England to commemorate British triumph when controlling Indian territory (Bandyopadhyay 2018), the Caribbean offers the existence of the Taino people to attract foreign tourists (Smith and Spencer 2020), and cultural and agricultural ecology of the “Sierra Productiva” in the Peruvian Andes has become a major tourist attraction (Westmont 2020).

Likewise in the Northern area of Sweden which tries to empower the indigenous Sami people to fill opportunities in tourism sector in regards to their community work, namely herding deer (Leu 2019). Besides, the Cyprus empowers women entrepreneurs in rural North Cyprus who develop eco-tourism. This empowerment has an impact on the welfare of women (Ertac and Tanova 2020). Apart from Cyprus, tourism in Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala provides equality and justice in cultural tourism to the Maya Tz'utujil community (Harbor and Hunt 2020), and that the Australia tries to preserve the cultural heritage of the indigenous people in Cairns, Queensland to offer it to foreign tourists (Abascal 2019), while the Iran uses urban regeneration to reduce the attractiveness of the historic city of Birjand as to bring tourists back to the city of Birjand (Lak et al. 2020). Likewise other countries that are not mentioned in this paper will strive for presenting the best efforts for their future tourism.

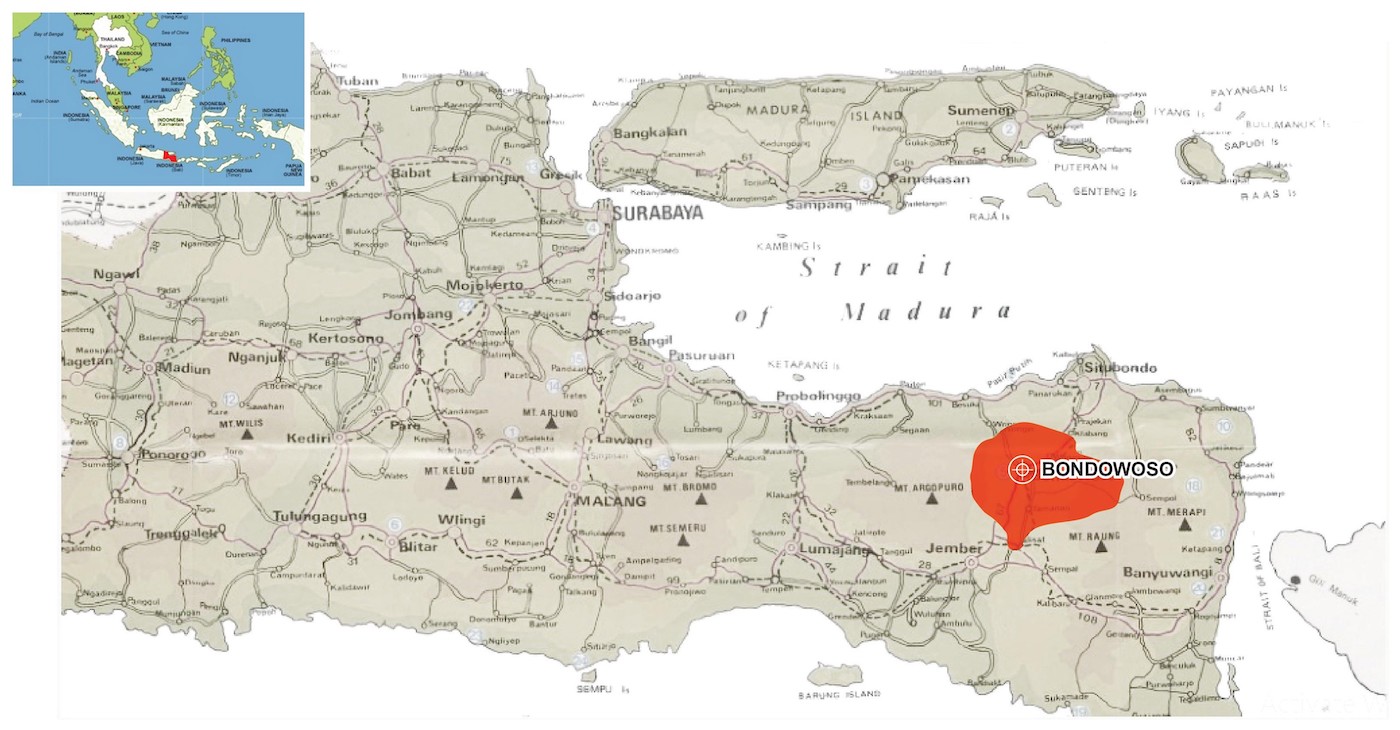

Furthermore, in the context of Indonesia, the government of Indonesia offers many tourist destinations for foreign tourists, such as a beautiful rural atmosphere, a unique cultural heritage, historical heritage, beaches, and others. The encouragement of the President of Indonesia, Joko Widodo to the Regional Government to promote regional tourism to advance the economy of the people has consistently performed. One of them is Bondowoso Regency which strives for maximizing its natural and human resources to create tourist destinations.

Based on the data in the Central Statistics Agency, the 2010 Population Census states that there are 1331 ethnic groups in Indonesia (Center for Statistics 2015). One of the interesting things to offer both domestic and foreign tourists in Bondowoso Regency is the Madurese ethnic group with its unique cultural characteristics. This study chose the spatial scope of Bondowoso Regency which was located in the Eastern Edge of Java, Indonesia. In its historical timeline, Bondowoso Regency had been popular since 1900s with the export of Arabica coffee plants to Europe. Starting in 1894, the Dutch investor Gerard David Birnie had leased land on the highlands of Ijen Bondowoso to the Dutch colonial government. The Ijen Plateau was transformed into an Arabica coffee plantation, and the majority of the population in the Bondowoso Regency area was Madurese ethnic as cause of number of migrants from Madura who worked in some plantations in the Dutch colonial period.

This study aimed to analyze the reasons that the Regent of Bondowoso chose Madurese culture to be a tourist destination for Bondowoso Regency, and the impact of the commodification of Madurese culture on the welfare of the Bondowoso community. This study significantly contribute to the development of cultural studies and history research.

Method

To get a detailed and chronological description on the use of Madurese culture as a vehicle for developing tourism in the Eastern Edge of Java, Indonesia, the author applied the theory of commodification and historical method. Commodification is a process (like capitalism), where objects, qualities, and signs are converted into commodities. It is also something that has a main purpose of selling in the market (Barker 2005). Tester argues that commodification is the process of works of art; both abstract and concrete that are previously sacred works for offering (Tester 2009). With full awareness and careful calculation of artists and consumers, the commodification is produced to fulfill the market needs and sold to people who need it.

The historical method was used to obtain information since when the Madurese culture had contested in front of the public, as well as to criticize whether the commodification of Madurese Culture as the flagship of Bondowoso Regency was detrimental to its people, or (on the contrary) they got benefit from the presence of Madurese culture. There were four stages in the historical method applied in this study, namely: (a) heuristic stage; the stage of collecting data sources, (b) critical stage; the stage of sorting out data, (c) interpretation stage; the stage of analyzing data, and (d) historiography stage; the writing stage (Gottschalk 1986).

In the first stage, sources were divided into two sorts, namely primary and secondary sources. Primary sources were obtained from the Dutch Colonial Archives, the results of interviews with the Regent of Bondowoso Amin Said Husni, the Head of Bondowoso Tourism Office, cultural actors, people who owned Madurese culture in Bondowoso, as well as domestic and foreign tourists. Apart from conducting interview, we also conducted participatory observation. Finally, the secondary sources such as published works, study’s results, and government reports were involved in this study.

The second stage was source criticism. In this stage, we sorted out the data and information which was resulted from the first stage. This stage was completed to obtain valid information related to the historical process of the migration of Madurese people to Bondowoso, the formation of the Madurese community, the birth of the Madurese culture to the efforts made by the Bondowoso Regent to get revenue generating from tourist destinations.

The third stage was interpretation that purposed to analyze information that have been criticized in the second stage, so that we could get conical focused information about the superior culture of Bondowoso Regency that was exploited by the Regent as a vehicle to develop tourism sector in Bondowoso. The final stage was writing down and listing the selection of Madurese culture as the leading culture of Bondowoso Regency to advance tourism sector as well as its impact on society.

Results and Discussion

Migration of Madurese People to Bondowoso Regency

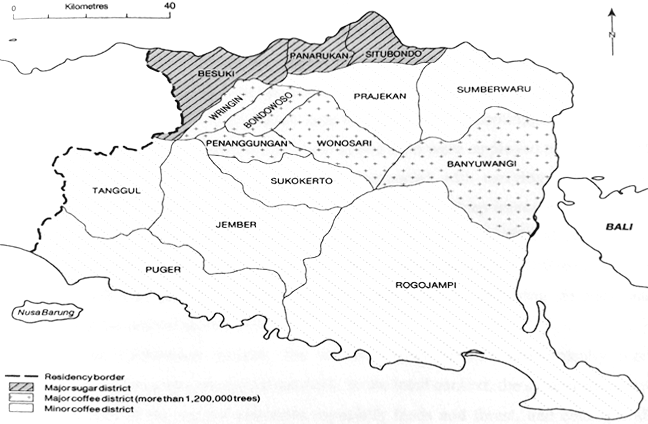

Initially, Bondowoso Regency was part of the Besuki Residency. According to information from Babad Basuki (Komari 2014) that prior to the formation of the Besuki Residency, the Besuki area was opened by Kyai Wirabrata from Tanjung Village in Pamekasan Regency, and this evidence was estimated around the first half of the eighteenth century (Language Center of National Education Department 2002). The high cost of food due to the difficulty of water-flow into the fields had encouraged Kyai Wirabrata to venture into Besuki area. He came to Demung Village and finally created a new hamlet by clearing up the forest to establish rice fields. He was also considered as the forerunner to clearing land in the area of Besuki. Gradually, the area of Besuki had become densely populated as a result of the large number of Madurese and Javanese ethnic who ventured into some areas in Besuki. During the British colonial period, Raffles had founded the Besuki Residency in 1811.

In its beginning of establishment, the Besuki Residency consisted of two afdeelings, namely Besuki Afdeeling and Probolinggo Afdeeling. Yet, in 1820, Panarukan, Bondowoso, and Kraksaan Afdeeling were included in the coverage area of Besuki Residency. In its development, Besuki had experienced rapid progress during the leading period of Regent Ronggo Kiai Suroadikusumo (Mashoed 2004), especially with the presence of Besuki Harbor. The large number and densely population of migrants that populated Besuki had led to an expansion of the area. The Regent Ronggo Kiai Suroadikusumo comprehensively gave instructions to Raden Bagoes Assra (originally from Pamekasan, Madura) to clear up the forest in the southeast area of Besuki. The forest that was successfully cleared up was later named Bondowoso (Soerjadi 1974), and that Raden Bagoes Assra was the first regent (Regent I) of Bondowoso (1819-1830).

The migration of the Madurese to the Bondowoso was more intense, especially by the opening of plantations in some areas in Bondowoso by investors who rented land in Bondowoso in approximately 1894 (Departement van Binnenlandsch Bestuur 1915). In 1928, the shipping company "Bodemeijer" conducted daily shipping from Sumenep to Panarukan. People from Madura and Sapudi who migrated to Bondowoso to get a job on plantations used this shipping traffic. The Dutch colonial government even provided buses that would transport them to Bondowoso, Jember and Banyuwangi (ANRI 1978a). The opening of the Bondowoso area to migrants has resulted number of Madurese settled in Bondowoso Regency.

| Regency | District | Javanese | Madurese | Osing | Other* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bondowoso | Tamanan | 0.5 | 99.3 | - | 0.2 |

| Bondowoso | 0.4 | 99.3 | - | 0.3 | |

| Wonosari | 0.6 | 99.2 | - | 0.2 | |

| Prajekan | 0.7 | 99.1 | - | 0.2 |

The Birth of Madurese Culture and Local Wisdom

The large number of Madurese ethnic who settled in Bondowoso Regency had an impact on the emergence of new cultures by taking along the cultures that had been inherent for Madurese migrants. Van Peursen argues that culture is a human activity in his life which signified his work, feeling, thought, initiatives and creation, so that he concludes that culture is the result of a process of human feeling, initiative and creation (Peursen 1988). The culture brought by migrants from Madura was inseparable from the geographical conditions in the region. Madurese ethnic characteristics are shaped by the ecology of crop and dry field (Kuntowijoyo 2002). The ecology forms a pattern of human settlement, making villages in Madura with no territorial boundaries but rather a mixture of small units (areas) that are formed from kinship principles. Madura has a little sense of village solidarity. The land tenure system does not recognize communal land. Besides, social relations in Madura are centered on individual with nuclear family as its basic unit. The pattern of Madurese socialization is to create individuals who believe in themselves rather than being communal and cooperative individuals.

The ecology of crop (dry field) has caused Madurese Ethnicity to have unique characteristics. This uniqueness can be seen through their behavior; they are more materialistic than Javanese ethnic and speaking loudly due to their geographical area (dry field ecology) with some houses that are set far apart. Madurese ethnic is superior to Javanese ethnic as a result of the some challenges of their lives in Madura. The Madurese ethnic prefers to be thrifty, diligent, and hardworking. Their primary food is corn, and their favorite business is crop cultivation. They have a tendency to raise livestock; not only for their farms, but for "competing" and "kerapan" (bull-fighting and racing) that are regularly conducted and involve amounts of bets.

Some of Madurese ethnic cultures resulted from their ecology are Kerapan Sapi, Sapi Sonok (cow beauty contest), Ronteg Singo Ulung, Pojien Dance, Bersih Desa (village cleaning) Ritual, and Petik Kopi Ritual. These cultural products had also become the local wisdoms of Madurese people who lived in Bondowoso Regency.

Commodification of Madurese Culture as Bargaining Power of Regency Destinations in Bondowoso

There are many strategies that local government can expose their territories. The goal is to promote the existence of a region in the district and to generate revenue that generates for the progress of the region. The Regent of Bondowoso has a unique way to make his area lively with tourists; both domestic and foreign tourists. The method is reviving Madurese culture inherent in the community of Bondowoso. The existence of the area of Ijen Plateau with Blue Fire tourist spots, sulfur stones, and Arabica coffee plantations are used as entry points to promote Madurese ethnic culture as the majority ethnic who settle in Bondowoso Regency. These cultures include Kerapan Sapi, Sapi Sonok (cow beauty contest), Ronteg Singo Ulung, Pojien Dance and Petik Kopi Ritual. These cultures are produced due to the spirit of Madurese community in Bondowoso Regency to revitalize their local wisdom.

Kerapan Sapi

In historical context, this culture had emerged after undergoing a process of adaptation to barren environments, dry agriculture, and primitive farming patterns. Based on some sources, Kerapan Sapi was initiated by Prince Katandur (Syech Ahmad Baidlowi) as the ruler of the Mandaraga Kingdom before the emergence of Majapahit Kingdom. He attempted to prosper his people by increasing agricultural production using cow power. Furthermore, this method was more popular and quickly spread among the community. After harvesting period, there was always a competition similarly called as anangghâlâ (plowing the fields) (Kosim 2007). This Kerapan Sapi was held after the harvest period in the fields which purposed not only to increase food production, but also to increase the maintenance of cow (cattle).

During the Dutch colonial period, cow (cattle) breeding was very important. Madurese people were talented to be cow breeders, because they were motivated by the pleasure of cow fight, Kerapan Sapi and cow (cattle) exhibitions. Up to 1928, the local government of Besuki had provided a premium in cow fair. Cow fight and Kerapan Sapi were frequently held in Bondowoso Regency, and it had become a joy for the people of Bondowoso who were factually Madurese (ANRI 1978b). Usually, the Dutch colonial government held cow fight and Kerapan Sapi in Public Garden of Bondowoso, especially when the coffee and tobacco harvest seasons were over. Besides, the Dutch colonial government usually held these exhibitions to entertain the community of Bondowoso plantation. At the exhibition, cow fight, Kerapan Sapi, and Sapi Sonok (cow beauty contest) were usually held. The evidence that cow (cattle) breeding is greatly important in Bondowoso can be seen from the population below.

| Year | Number of Population |

|---|---|

| 1927 | 181,412 cows |

| 1928 | 194,040 cows |

| 1929 | 194,269 cows |

The increase in the population of cow (cattle) was quite large due to some imports, especially from Madura. There were also quite a lot of cattle slaughtered. This was related to many European ethnicities, especially the Dutch who settled in Bondowoso and consumed beef for their daily food. In 1928, the number of cow being slaughtered were 20,454 cows. As mentioned above, apart from being slaughtered for European to consume, the cattle was also used for Cow Fight, Kerapan Sapi, and Sapi Sonok.

Nowadays, the Kerapan Sapi in Bondowoso is used as a ritual medium to beg for rain as blessing. Usually, the ritual is held in one of the residents' fields followed by approximately 20 participants from some areas surrounding Wringin and Bondowoso. The Kerapan Sapi is no longer presented as in the Dutch colonial era, because the audience abuses it as a gambling event.

Sapi Sonok Contest

Sapi Sonok can be defined as a cow that is dressed as beautiful as possible. All cows who can participate in this event must be female ones. The cows that are contested are formed in pair and are coupled with a tool called Panggonong. The cows are controlled by a jockey; walking slowly to the rhythm of the typical gamelan music. It is the swing and harmony to the beat, and the beauty of the cow will be the point to be marked. In the race arena, there is a 'catwalk' which is prepared completely with a carved gate at the finish line. The cows that have been dressed will set its feet on a wood that has been prepared in the finish line. The following picture is the implementation of Sapi Sonok contest during the Dutch colonial period which was held after the coffee and tobacco harvest period had been completed. The purpose was to entertain the community of Bondowoso whose majority of work was a labor at coffee and tobacco farming. The entertainment was regularly held annually by the Dutch colonial government and supported by investors who rented land for large plantations. The investors had an interest in the exhibition, so that the workers were entertained and happy. Besides, they were more active in working on their plantations.

In the present time, Sapi Sonok contest is no longer available in Bondowoso. It merely remains cattle breeding contest resulted from the artificial insemination (IB). This contest is a form of success for Bondowoso Regency in the livestock sector. Besides, it is also a means of communication between cattle breeders and the process of developing cattle by means of artificial insemination. The cow contests resulted from artificial insemination (cross-breeding cattle) include limusin, simental, brahman and local cattle that had been initiated by people in Bondowoso since 1982. However, Sapi Sonok contest is still held in Madura Island.

Ronteg Singo Ulung

In Indonesia, every region should have a story about the origin of the area. This commitment proves that the community has local wisdom to be presented, so that it will be a pride of their area. Likewise with the story of Ronteg Singo Ulung as an art originated from Blimbing Village, Klabang District, Bondowoso Regency. This art was originally performed at village (local) ceremonies. During its development, Singo Ulung changed its name to Ronteg Singo Ulung which was performed at celebration events, Agustusan, official district events, art events across cities, and art competition at the provincial and national levels (Bhagaskoro 2014).

An oral tradition in the community of Blimbing Village, Bondowoso described that Singo Ulung was a nobleman from Blambangan Banyuwangi who accustomed to wander. Once upon time, during his wander to the west areas, he accidentally arrived at a forest filled with star fruits. Singo Ulung's arrival into the wilderness had attracted the attention of a figure who lived in the forest area, namely Jasiman. It was a habit in traditional society that someone could be viewed as a figure when he has met and examined with various challenges and supernatural powers. This commitment signified whether the man could keep himself properly or not. On the other word, when he was not able to protect and defend himself, he automatically would not be able to protect and defend his people. In broader context (e.g. in traditional societies), a leader would be wise and charismatic when he had a physical and spiritual superiority.

Knowing that Singo Ulung arrived in the area, Jasiman was encouraged to test Singo Ulung's power. By his stick, Jasiman was ready to fight with Singo Ulung armed with a dagger (keris). Then, they got into a fight. The two swordsmen tried their best power to knock their opponents down as fast as possible. Yet, because they were the same (just as powerful), after hours of fighting, no one seemed to have lost. It seemed that the battle was balanced. Then, they stopped fighting, and stared each other with smile. They immediately agreed to be a friend. Singo Ulung was accepted to settle in a forest area. A few moments, they rested under a tree. Singo Ulung asked Jasiman, "What tree is this?" Jasiman replied, “This is a star fruit". Since then, the wilderness area was named Belimbing (Winarni 2019).

The art of Ronteg Singo Ulung has become more interesting because of the attractions in it, such as dancing, jumping over lions, and entering a circle of fire. In the attraction, Ronteg Singo Ulung was accompanied by musical instrument. This is what distinguishes Ronteg Singo Ulung with other arts performance like Singo Barong and Barongsai. Singo Ulung consists of two categories, namely Singo Ulung in the traditional ceremony of “Bersih Desa” and Singo Ulung in the form of Ronteg. The musical instrument used in the Singo Ulung art performance in “Bersih Desa” and Ronteg has a slight difference, namely in the number of musical instruments. Singo players in Ronteg Singo Ulung are usually played by boys with 20-25 years old, while in Ronteg, age is an important factor, because there are always movements that use body strength, such as high-jumps, body flip, and so on (Astuti 2009). The following picture is the art performance of Ronteg Singo Ulung in Bondowoso Regency.

Petik Kopi Ritual

The Indonesians were accustomed to demonstrate rituals in their life during the pre-literacy era. People were able to think intelligently (called as local genius) to interpret the events in their environment. As an illustration, before knowing Hinduism and Buddhism, the Indonesian people could embody something beyond their own strength. They believed that there were other powers that could protect, provide health and guide them through dreams. They also believed in the power of spirits (animism), worship of ancestral spirits (dynamism) by using seven forms of flowers as a medium for offering, so that they could remain protected. The rituals that are available in the community had continued to be maintained along with the presence of Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity. Ball, J. Van (1997) states that the role of ceremony (ritual and ceremonial) is always reminding people on the existence and relationship with their environment. By the existing ceremonies, the community are not only reminded, but rather being accustomed to use and abstract symbols which position in the level of thought for various actual social activities in daily life.

The majority of the economic life of the Bondowoso’s community is supported by coffee plantations, so that the culture that sets in the community is related to rituals and farming on coffee plantations. The ritual performed by coffee farmers in Bondowoso is Petik Kopi ritual which relates to worship on natural rulers and ancestral spirits to appeal for the success of the coffee harvest and the welfare of its people. This cultural commitment is inseparable from the myth for cultural supporters to maintain and preserve harmony in the life of the coffee farming community in Bondowoso Regency. It seems that coffee farmers oblige themselves to perform a ritual before harvesting coffee which purposes to get an abundant coffee harvest and avoid the theft of coffee. Usually, the farmers make a scoop of rice (Tumpeng) accompanied with fried chicken, beef, vegetables, snacks, coffee, and incense brought into their plantations. They also invites Kyai (religious leaders) to lead prayers and end up by having meal together. They also invite their labors to join in. The event is ended with incense burning in their garden. The following picture is a ritual performed by individual coffee farmers in their coffee plantations when harvesting coffee.

The Petik Kopi ritual was chosen by the Regent of Bondowoso, Amin Said Husni, as one of the tourism destinations in Bondowoso Regency. This ritual has been an annual agenda for Bondowoso Regency conducted every July when the coffee harvest be started. The ritual is designed as a public spectacle for tourists who visit Bondowoso. The ritual event is interspersed with the presentation of Madurese culture that sets in its society, such as the performance of Remo Dance, Pojien Dance, and Ronteg Singo Ulung Dance. Besides, the Ritual Petik Kopi is held directly on a plantation owned by one of Bondowoso coffee farmers. Usually, a plantation which locates in the side of the road is chosen, as well as to present a good short coffee plantation as a promotion for the superior product of Bondowoso Regency, namely Arabica Coffee. The ritual begins with a joint-walk between the Regent, farmers, invited guests, tourists, and other people who come into the designated coffee plantation areas. The ceremony begins with a group of prayer led by the Kyai using a bouquet (see Figure 10) and Tumpeng Rice (rice in the form of cone) being paraded to a coffee plantation (see Figure 11).

The Tumpeng Rice is paraded into the coffee plantation. Usually, it is the result of mutual cooperation of coffee farmers. After prayer, the rice is eaten together. Then, the Regent begins picking or harvesting coffee as a sign of the beginning of the coffee harvest. In 2017, Petik Kopi ritual was attended by 22 representatives from European countries that were also members of the SCAE (Specialty Coffee Association of Europa). The ritual in 2017 was the ritual that had invited number of tourists; both domestic and foreign tourist (see Figure 12).

After the ritual Petik Kopi, the local people and tourists who were presenting the ritual were treated to the performance of Madurese culture. The first performance was proceeded with Remo Dance as a heroic dance and as a welcome dance. The dance signified a style and movement in accordance with the local area surrounded by agrarian communities, so that it showed swift movements which become the characteristics of regional movements, namely Pencak Silat. The following figure is the representation of Remo Dance as an initial performance after completing Petik Kopi ritual.

The next event was a performance of Pojien Dance (Praise Dance), a spiritual and mystical art performance. After the Madura’s gamelan music sounded, the Pojien players' actions began to be carried out by climbing bamboo sticks. The Pojien dance was usually held by residents of the Mountain Slopes in Ijen Bondowoso. About 15 meters of bamboo was stuck into the ground. Then, the players took turns to climb the bamboo lively like a monkey. It did not take a long time that the players had managed to reach the top of the bamboo and continued with dancing and striking at the end of the bamboo.

The ability of dancers to climb bamboo without any safety tool carried out in the Pojien Dance performance could not be separated from the rituals performed by the dancers before the show began. They had to do a penance accompanied by reading some prayers in order to successfully and safely climb a 15 meter high bamboo pole. The folk performances that highlighted art and basic beliefs or religions were colored and flourished in the Madura Strait areas (Tjiptoatmodjo 1983). The elements of pre-Hindu, Hindu or Islamic beliefs were evident in certain types of folk performances, especially Pojien Dance. Besides, the elements of pre-Hindu beliefs such as animism and dynamism were also seen in the symptoms of the inclusion of ancestral spirits or supernatural powers in the form of immunity; or in the ability to climb a 15 meter bamboo pole without safety equipment in a trance state (ndadi, in-trance). Pojien dancers would not feel afraid to climb a bamboo without safety equipment for themselves, because they had been already in a state of trance.

Pojien Dance is an art generated from generation to generation of local people who settled in the hillside area. The existence of Pojien Dance is inspired by the agility of the monkey which jumps over bamboo trees. During the colonial era, climbing bamboo was often used to see and watch over the enemy from a distance area. Linguistically, in Madurese terminology, Pojien meant praise, and contained a philosophical meaning that was to praise the majesty of God as well as submitting to the Creator. Pojien dance was often performed and presented during village salvation, harvest season, residents' celebrations, and welcoming guests. This performing art was a combination of Ronteg Singo Ulung Dance and some dances by male dancers with typical Madurese clothes, namely red and white striped shirts and baggy pants over black ankles. The following figure is the attraction of Pojien Dance as it is combined with Ronteg Singo Ulung Dance. Besides, the stages for Pojien Dance performance include:

- The dancers consist of men dancing by following typical Madurese music around a bamboo pole that has been embedded on the ground. It was used as a medium for Pojien dancers to climb bamboo stalks. The dance was complemented by Singo Ulung Ronteg Dance (see Figure 14).

Bamboo being embedded on the ground as a medium for dancers to climb the bamboo (Research Document) - The Pojien dancers dance on bamboo—15 meters in height—without any safety equipment on their bodies. Dancers in this Pojien dance are usually passed down from generation to generation. The dancers did not only practice physical skills but also spiritual "laku". There were prayers that must be read and penance from the dancers of the Pojien Dance, so that the dancers were able to perform the skills of climbing 15 meters of bamboo without any security equipment for their safety. Pojien dancers were climbing the bamboo while dancing. The Pojien dancers were already in a state of trance, so that they did not realize that they were climbing bamboo (see Figure 15).

Pojien Dance (Research Document) - The Pojien dancers climbed the bamboo stick very quickly and reached the top of the bamboo. The position of the Pojien dancer was already in a state of trance, so that he did not feel that he had climbed a 15 meters high of bamboo without security equipment quickly until he reached the peak of the bamboo (see Figure 16).

Pojien Dance (Research Document) - The Pojien dancers climbs the bamboo with 15 meters above the ground while dancing. The position of the bamboo that was stuck in the ground was also without any security equipment. At the top of the bamboo, the Pojien dancer remains in a trance, with no fear of falling from the 15 meter height (see Figure 17).

Pojien Dance (Research Document)

Conclusion

Madurese Culture had possessed a fortune space for Kerapan Sapi, Cow Fight, and Sapi Sonok contest since the Dutch colonial era. The annual event that was held after the completion of coffee and tobacco harvest, was able to provide a means of entertainment for people in the Residency of Besuki which included Besuki, Panarukan, Banyuwangi, Jember, and Bondowoso Regency. They will come in group to Bondowoso Town Square to watch the spectacles organized by the Dutch colonial government and plantation company investors. The event served as a medium for investors to meet their work partners, while the community could watch as well as making a gamble for Kerapan Sapi, Cow Fight, and Sapi Sonok contest.

The success of promoting Madurese culture during the Dutch colonial era was repeated during the period of the Regent Amin Said Husni. The existence of Madurese culture as the superior culture of Bondowoso Regency as offered to both domestic and foreign tourists was an actual and precise thought of the Regent Amin Said Husni. The performance presented in Petik Kopi Ritual as one of Bondowoso tourist destinations was the result of commodification which was indirectly accepted by the Bondowoso community; ranging from Petik Kopi ritual held by farmers sacredly, the performance of Singo Ulung Ronteg which was usually carried out in Bersih Desa, the Pojien Dance which was usually carried out in a sacred manner to praise the majesty of God, were all performed and presented for publics. There was no internal resistance of the people, but remained a common awareness that the ritual Petik Kopi was intended for the benefit and kindness of the community's welfare.

The benefits of Petik Kopi ritual as a medium for tourist destinations are now realized as a means of promotion to vend Arabica coffee products for farmers as well as a promotion for cultural actors. The players who appear in Remo Dance, Singo Ulung Ronteg Dance and Pojien Dance can get extra jobs, because they are indirectly promoted in the ritual of Petik Kopi. However, this ritual which is intended for tourists’ consumption should be done professionally and continuously. This commitment has become a challenge that should be concerned by the Bondowoso Tourism Office, so that the ritual can become a magnet for generating revenue for the community and the Government of Bondowoso Regency.

On the other hand, Madura Island (as a place of the origins for Madurese ethnic migrants who spread to Java region, especially Bondowoso Regency [East Java]), finally received attention from the state with the construction of the SuraMadu (Surabaya-Madura) Bridge. The bridge was completed in 2009 and it was a solution for the state to unravel Madura Island's remoteness from limited transportation connectivity, limited water resources, and karst geology. Several researchers offered post-operational solutions for the bridge. Firstly, offering an industrial ecology concept to create a sustainable green industry in Madura Island region (Widjaya & Tanuwidjaja 2017). Secondly, offering to better understanding on the reality felt by the community on a local scale, where appreciation of the cultural context was paramount (Delphine & Spit 2019). Thirdly, the construction of the bridge has an impact on the decline in ship passengers, resulting in decreased income of traders and public transport drivers operating around the port area. This research helped to predict the number of ship passengers including pedestrians, motorcyclists, and car drivers, which is carried out using the ARIMA Box-Jenkins method (Prastuti et al. 2020). Fourth, SuraMadu Bridge was an industrial bridge, cultural acculturation bridge, and economic acceleration bridge. Obviously, there is modernization and industrialization that will flow smoothly to Madura through this bridge (de Jonge 2011).

The author has a view that there are four districts in Madura Island, namely Bangkalan, Sumenep, Pamekasan and Sampang districts. Each head of region can explore the cultures of the people. Today, the head of regions in Madura Island just offer tourists a historical tourism, architectural tourism, nature tourism and religious tourism which are commonly practiced by many regions in Indonesia. These offers have not been able to attract tourists, both domestic and foreign significantly, even though it has been connected between the Madura mainland and the East Java mainland by SuraMadu Bridge. The uniqueness of Madurese culture that is inherent in its ethnic identity is the culture of Kerapan Sapi, Sapi Sonok or cow beauty contest that can be a magnet for tourists to come to Madura Island. Kerapan Sapi, Sapi Sonok or cow beauty contest can be used as a show that is regularly scheduled as well as being an icon of Madura Island. It is like repeating the glory of Madurese culture in the destination areas of Madurese ethnic migrants, such as Situbondo, Bondowoso, Jember, and Probolinggo in the form of Kerapan Sapi and Sapi Sonok contests that have been contesting in front of the public since the Dutch colonial era. The elements of uniqueness and ingrained in the Madurese ethnic represented in the Kerapan Sapi and Sapi Sonok contest. These cultural activities need a serious attention from the local government on Madura Island, so that the SuraMadu Bridge is more meaningful and prosperous for the people of Madura Island. Therefore, the researchers recommended future research to explore the uniqueness and essence of Kerapan Sapi and Sapi Sonok contest that have been a part of Madurese ethnic in term of professional competition.

Acknowledgments

A great gratitude to the Directorate General of Research and Development Reinforcement of the Ministry of Research and Technology, the National Research and Innovation Agency for supporting this research funding for Doctoral Dissertation Research Grants in the 2019–2020 Fiscal Year. This study is a part of a dissertation entitled "Land Privatization and Socio-Cultural Change in the Regents-chap of Bondowoso Region in 1894-1930" in the Doctoral Program of History, Department of History, Faculty of Humanities, Diponegoro University, Semarang. The author also would like to deliver her gratitude to the Promoter Prof. Dr. Singgih Tri Sulistiyono, M.Hum, and Co-Promoter Prof. Dr. Yety Rochwulaningsih, M.Si who have provided a support for this research as well as the writing of the author’s dissertation.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest in this study.

References

- Abascal, T. E., 2019. Indigenous tourism in Australia: Understanding the link between cultural heritage and intention to participate using the Means-End Chain theory. Journal of Heritage Tourism. 14 (3): 263-281.

- ANRI., 1978a. Memori Serah Jabatan 1921-1930 (Jawa Timur dan Tanah Kerajaan) [Memory of Position Transfer in 1921-1930 East Java and the Kingdom]. Gadjah Mada University Press, Yogyakarta.

- ANRI., 1978b. Memori Serah Jabatan 1921-1930 (Jawa Timur dan Tanah Kerajaan) [Memory of Position Transfer in 1921-1930 East Java and the Kingdom]. Gadjah Mada University Press, Yogyakarta.

- Astuti, S. R., 2009. Kesenian Singo Ulung di Bondowoso: Suatu Kajian Sejarah Seni Pertunjukan [Singo Ulung Performing Arts in Bondowoso: A Study of Performing Arts History]. Vol.10. Patrawidya, Bondowoso.

- Ball, J. Van., 1997. Sejarah dan Pertumbuhan Teori Antropologi Budaya (Hingga Dekade 1970) [History and Development of Cultural Anthropology Theory]. Gramedia, Jakarta.

- Bandyopadhyay, R., 2018. 'Longing for the British Raj': Imperial/colonial nostalgia and tourism. Hospitality and Society. 8 (3): 253-271.

- Barker, C., 2005. Cultural Studies, Teori dan Praktik [Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice]. Kreasi Wacana, Yogyakarta.

- Bhagaskoro, A., 2014. Bentuk komposisi musik pengiring seni pertunjukan ronteg singo ulung di padepokan seni gema buana desa Prajekan Kidul kecamatan Prajekan kabupaten Bondowoso provinsi jawa timur [Form of Instrumental Music on Ronteg Singo Ulung in the Art Studio Gema Buana Prajekan Kidul Village, Prajekan District, Bondowoso Regency East Java Province]. Jurnal Seni Musik. 3 (1): 1-13.

- Bosch, C. J., 1857. Aanteekeningen over de Afdeeling Bondowoso (Residentie Besoeki). Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land, -en Volkenkunde, 6, pp. 469-508.

- Center for Statistics., 2015. Mengulik Data Suku di Indonesia [Identifying the Data of Ethnicity in Indonesia]. https://www.bps.go.id/news/2015/11/18/127/mengulik-data-suku-di-indonesia.html.

- Delphine, Witte, P., Spit, T., 2019. Megaprojects – An Anatomy of Perception Local People’s Perceptions of Megaprojects: The Case of Suramadu, Indonesia. DISP. 55(2): 63-77.

- Departement van Binnenlandsch Bestuur. 1915. Lijst van: Particuliere ondernemingen in nederlandsch-indie op gronden door het gouvernement afgestaan in huur (voor landbouwdoeleinden) en erfpacht 1914. Landsdrukkerij, Batavia.

- Ertac, M., Tanova, C., 2020. Flourishing women through sustainable tourism entrepreneurship. Sustainability. 12: 1-17.

- Gottschalk, L., 1986. Mengerti Sejarah [Understanding History]. Universitas Indonesia Press, Jakarta.

- Hageman Jcz, J., 1863. Aanteekeningen over Nijverheid en Landbouw in Oostelijk- Java. Tijdschrift voor Nijverheid en Landbouw in Nederlandsch Indie, 9, pp. 296-332.

- Harbor, L. C., Hunt, C. A., 2020. Indigenous tourism and cultural justice in a Tz’utujil Maya community, Guatemala. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 29(2-3): 214-233.

- Johari, S., Kunasekaran, P., 2019. Bidayuh community’s social capital development towards sustainable indigenous tourism in Sarawak, Malaysia. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering. 7 (5): 351-353.

- Jonge, Huub de, 2011. Garam, Kekerasan dan Aduan Sapi: Esai-esai tentang Orang Madura dan Kebudayaan Madura [Salt, Violence, and Cow Contest: Essays on Madurese and Its Culture]. LkiS, Yogyakarta.

- Komari., 2014. Babad Basuki dan Bandawasa: Deskripsi, Alih Aksara dan Alih Bahasa [Babad Basuki and Bandawasa: Description, Transliteration, and Translation]. Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia, Jakarta.

- Kosim, M., 2007. Kerapan Sapi; Pesta rakyat Madura (Perspektif historis- normatif) [Kerapan Sapi: Party of Madurese in the Perspective of Normative-Historic]. Karsa: Jurnal Sosial dan Budaya Keislaman. 11: 68-76.

- Kuntowijoyo., 2002. Perubahan Sosial dalam Masyarakat Agraris: Madura 1850-1940 [Social Change in Agrarian Society: Madura 1850-1940]. Mata bangsa, Yogyakarta.

- Lak, A., Gheitasi, M., Timothy, D. J., 2020. Urban regeneration through heritage tourism: Cultural policies and strategic management. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change. 18 (4): 386-403.

- Language Center of National Education Department., 2002. Babad Basuki: Suntingan Teks dan Terjemahan [Babad Basuki: Text Editing and Translation]. Pusat Bahasa Depdiknas, Jakarta.

- Leu, T. C., 2019. Tourism as a livelihood diversification strategy among Sámi indigenous people in Northern Sweden. Acta Borealia. 36 (1): 75-92.

- Widjaya, J. M., Tanuwidjaja, G., 2017, Sustainable Agro-Industrial Ecology Concept of the Madura Island, IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 79(1): 012025.

- Mashoed, 2004. Sejarah dan Budaya Bondowoso [History and Culture of Bondowoso]. Papyrus, Surabaya.

- Nawiyanto. 2007. Environtmental Change In A Frontier Region Of Java: Besuki, 1870-1970. Ph D Thesis. Australian National University, Canberra.

- Peursen, C. A. van., 1988. Strategi Kebudayaan [History of Civilization]. Kanisius, Yogyakarta.

- Prastuti, M., Ulama, B. S. S., Nurindraprasta, P. P., 2020. Forecasting amount of passanger of ships in Madura strait port using ARIMA Box-Jenkins method, Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 1490(1): 012006.

- Renkert, S. R., 2019. Community-owned tourism and degrowth: a case study in the Kichwa Añangu community. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 27 (12): 1893-1908.

- Smith, J., Spencer, A. J., 2020. “No One will be Left Behind?” Taíno indigenous communities in the Caribbean and the road to SDGs 2030. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes. 12 (3): 305-320.

- Soerjadi, R. N., 1974. Sejarah Besuki [History of Besuki]. Tp, Bondowoso.

- Tjiptoatmodjo, S. F. A. 1983. Kota-Kota Pantai di Sekitar Selat Madura (Abad XVII Sampai Medio Abad XIX) [Cities around Madura Straits in XVII to mid XIX Century]. Dissertation. Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta.

- Tester, K., 2009. Immor(t)alitas Media [Immortality of Media]. Juxtapose, Yogyakarta.

- Thimm, T., 2019. Cultural sustainability–A framework for aboriginal tourism in British Columbia. Journal of Heritage Tourism. 14 (3): 205-218.

- UNWTO., 2019. Sustainable Tourism for Development Guidebook. World Tourism Organization, Spain.

- Volkstelling 1930 Vol. 3., 1934. Inheemse Bevolking van Oost Java. Landsdrukkerij, Batavia.

- Westmont, V. C., 2021. Of guinea pigs and tourists: Sustainable development, sustainable tourism, and “local food” in Cusco, Peru. Tourism Planning & Development. 18(1): 45-67.

- Winarni, S.I., 2019. Penggalian nilai-nilai tradisi Singo Ulung sebagai relevansi pembelajaran [Uncovering Traditional Values of Singo Ulung as Learning Relevance]. Jurnal Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra Indonesia. 15 (2): 12-19.