Insular Peninsularities: Geography, demography and local identity in Sydney’s Northern Beaches and Sutherland Shire

Abstract

In recent years there has been consideration of some peninsular areas as ‘almost-islands’ (presqu'îles, in French usage). Assertion of such status has usually relied on spatial configuration and the nature of transport links and/or border issues between the areas in question and adjacent regions. Bodies of land that are connected to mainlands by narrow isthmuses have been particularly prone to characterisation as ‘almost-islands’ but, to date, factors such as the perceived insularity of particular peninsulas within larger metropolitan areas have not featured as prominently in discussions. This article emphasises the latter with regard to the types of insularity perceived within two areas of Australia’s largest city, Sydney: its Northern Beaches and Sutherland Shire. These areas have been referred to in local and metropolitan media as ‘insular peninsulas’, a term distinctive to Australian English Language usage. Both are also known for their attractive beaches and swimming and surfing opportunities, factors that have contributed to local territorialism and related social tensions. Consideration of these two areas contributes to more general discussions of insular peninsularity by emphasising nuanced gradations involving factors such as socio-cultural homogeneity, local identity and perceived territorial rights.

Keywords

Insular peninsula, almost-islandness, Sydney, Northern Beaches, Sutherland Shire, Cronulla, Manly

Introduction

Over the last two decades Island Studies has addressed the nature of island societies and the factors that determine their internal cohesion and dynamics. Key to its self-justificatory impulse has been a rhetorical dichotomy that has over-emphasised the differences between islands and various types of shoreline locations. An increasing awareness of restrictive nature of this fundamental tenet prompted the journal Shima to publish a special issue (v10 n1) in 2016 addressed to the ‘almost-islandness’ of some coastal locales. The issue’s opening article (Fleury and Raoulx, 2016) set the tone by providing a detailed discussion of the complexities of the French language terms, péninsule and presqu'île. The former is closely similar to the English language term ‘peninsula’ in referring to fingers of land that project into marine or lacustrine spaces. The terms péninsule and peninsula are etymologically alike in deriving from the Latin term paeninsula, a conjunction of the terms paene (almost) and insula (island), but while their initial coinage conveyed the almost-islandness of locations they referred to, this specific association has diminished over time. This decline is highlighted by the development of another French language term specifically coined to restore the sense of particular peninsulas’ almost-islandness, the presqu'île (a compound of the terms presque [almost] and île [isle]). Amongst other uses, Fleury and Raoulx identify a modern application of the term as:

an artefact for promoting particular identities… built on the appeal of an island and its adjacent waters. In this case, the presqu'île is a sort of oxymoron: within the city, accessible, but associated with the sea and with the rêverie of being on an island. (ibid: 19)

Despite some degree of acceptance of peninsular almost-islandness as worthy of consideration within an expanded Island Studies frame, there has been little address to the perception and representation of the artefactual process “for promoting particular identities” (ibid) in particular types of peninsulas. We address this issue here with regard to characterisations of insular peninsularity. The latter term is not one that circulates in Island Studies but is, instead, derived from the colloquial characterisation of places as ‘insular peninsulas’. Google searches reveal this term to have been most commonly used by Sydneysiders (i.e. inhabitants of that Australian city) since the mid-1980s,1 and, in particular, by journalists, bloggers and social media posters referring to two areas, Sutherland Shire and the Northern Beaches.2 While the term lacks any formal definition in any authoritative source,3 it refers to peninsulas whose populations are socially insular due, in substantial part, to their distance from their metropolitan centres and related topographical and/or infrastructural impediments to easy access to other locations.

This article investigates the nature of insular peninsularity within the two areas that have been identified as such in Australian vernacular usage and thereby exemplify the concept. As we go on to identify, Sutherland Shire and the Northern Beaches are distinct in character, particularly with regard to the relatively unproblematic identity and boundaries of the former and the more ambiguous ‘essence’, edges and hinterland of the latter. The discussions that follow combine archival research, socio-historical analysis and auto-ethnography,4 drawing on the first named author’s residence in the Northern Beaches in the period 2016-2019 and the second named author’s long-time residence of Sutherland Shire, our senses of place in these locations and our interactions with other residents.

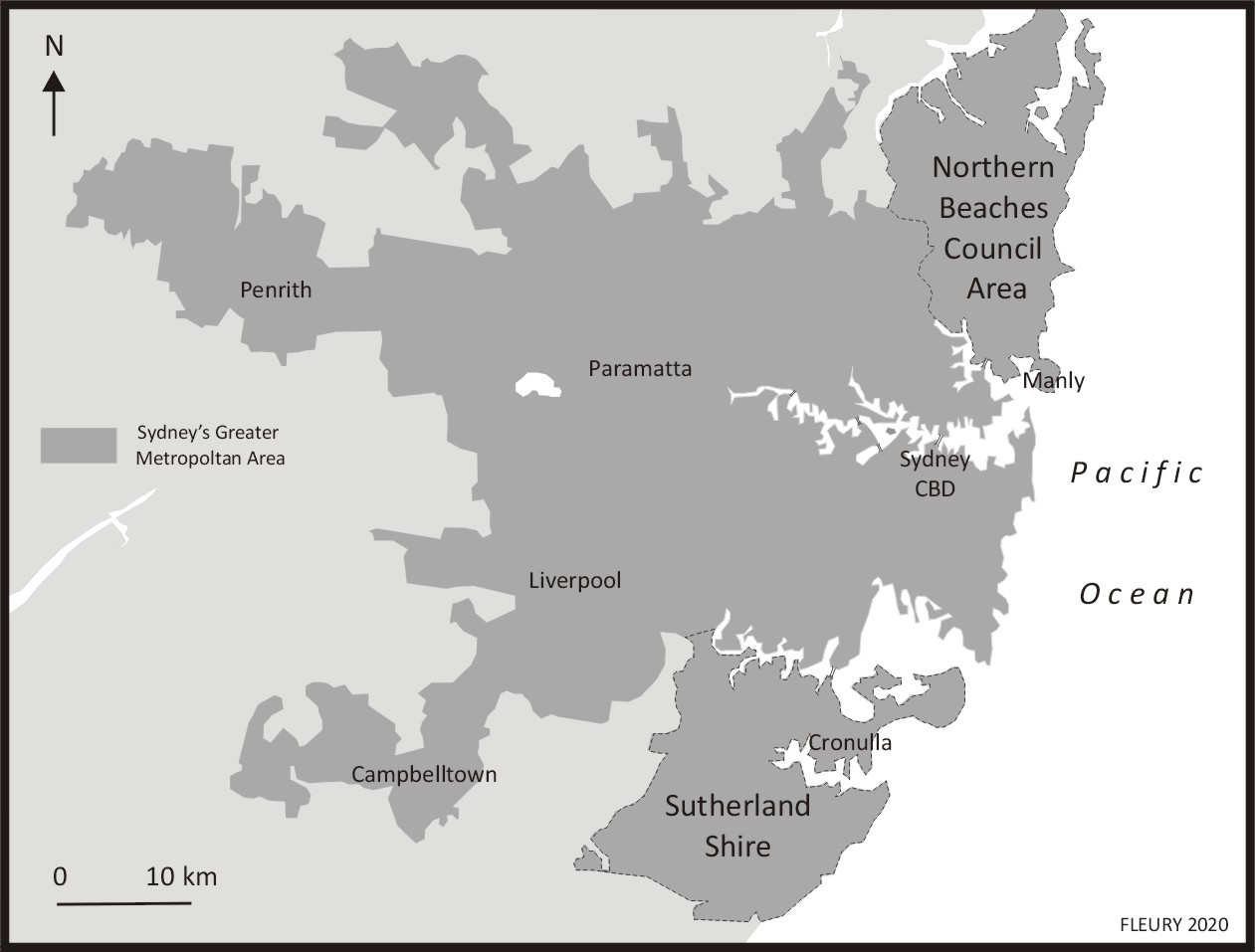

Sydney

Sydney, located on Australia’s eastern (i.e. Pacific) coast (Figure 1), is both the largest city in Australia (with a population of 4,446,805), and is the capital of New South Wales (NSW), Australia’s most populous state (population 7,480,228) (2016 census figures). The city originated as a penal colony established in Sydney Cove in 1788 by the British without the consent of the Indigenous Eora population. The settlement, initially known as Port Jackson, was at the centre of sustained conflict between the settlers and regional Indigenous groups between 1790-1816, with the settlers eventually prevailing, inflicting substantial casualties on Indigenous groups and dispossessing them of large areas of their traditional territories (Connor, 2002). Reflecting its status as the historical epicentre of European settlement, the NSW Parliament, the NSW High Court, other key government offices and its Central Business District remain congregated around Sydney Cove, which also houses the city’s major ferry terminus at Circular Quay. Sydney’s rail hub, Central Station, is located three kilometres south of the Cove.

Northern Beaches

Characterising and Defining the Area

In terms of the discussions that opened this article, there is no discernible tradition of the Northern Beaches, or of parts of it, being referred to as ‘almost an island’ within local discourse. Such a perception is however evident in some tourist perceptions of the south-eastern part of the area, including some that erroneously consider it to be an actual island. Indeed, the first named author of this article has had direct experience of this. An Asian colleague who was visiting Sydney for the first time travelled over to Manly on the ferry from Circular Quay to spend the afternoon with me in Spring 2018. When I met her at the jetty she exclaimed, “this is beautiful, what’s it like living on an island?” After gently disabusing her of her perception, discussion revealed that her characterisation arose from her travelling out from Circular Quay on the port side of the ferry, where, looking north-west in the later stage of the trip, she had seen the receding passage between Dobroyd and Middle Heads (Figure 2) and assumed that it marked the western coast of an island upon which Manly was located. Tourist bloggers such as Sian9 (2011), Basar (n.d.) and Zie (n.d.) have also extoled the virtues of a location they have perceived as ‘Manly Island’. Such characterisations point to one of the key factors in the perception of the Northern Beaches area as distinct from the rest of Sydney. The flooded river valley known as the Middle Passage, which originates as a creek in its northernmost part, winds between rocky hills rising up to 120 metres in height on either side, creating a 6 kilometre long interruption to Sydney’s Lower North Shore and giving the land to its east a peninsular aspect.

The unambiguous geography of the northern Barrenjoey peninsula, commencing at Newport and bounded by Pittwater Bay to its west and the Pacific coast to the east (Figure 2), has also prompted tourism commentators to raise the figure of the island to refer parts of it. The Wikitravel website, for instance, states that the “beachside suburb of Palm Beach backs on to Pittwater, a large southern inlet of Broken Bay, making the locality about as surrounded by water as is possible, without actually being an island” (n.d.: online). Adding a greater degree of complexity to such characterisations, the northern tip of the peninsula comprises an island (Barrenjoey Head) linked to the mainland by a low, narrow sandspit.

While the northern and southern parts of the Northern Beaches area can be considered as peninsular there is a nine kilometre long central section between them that segues into the hinterland of northern Sydney that problematises any characterisation of the Northern Beaches as a (single, unitary) peninsula. Similarly, the presence of a large lagoon at Narrabeen, and two bridges across it, are also perceived as something of an interruption that marks northern and southern areas of the quasi-peninsula. As subsequent discussions identify, the perceived peninsularity of the Northern Beaches arises from a combination of topographical impediments to accessing other areas, particular transport corridors and a related sense of isolation and insularity that is often represented as a defining aspect of the community. A sense of cohesive identity has also been boosted by recent changes in local government boundaries and related branding. Prior to 2016, the Northern Beaches fell within the boundaries of three separate councils, Pittwater, to the north, Warringah in the centre, and Manly, to the south. However, in 2016 the three bodies were merged, with a new authority administering an estimated population of 252,878 spread over 254 square kilometres (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016a) named Northern Beaches Council. While this name sat awkwardly with the inclusion of inland areas such as Frenchs Forest and Terrey Hills within that identity, the Council’s commitment to this branding was confirmed in 2017 by its adoption of a logo that incorporated symbolic references to predominantly coastal phenomena within a pattern that suggests at breaking wave at its upper point and a fish-tail at bottom right (Figure 3).5 But despite the Council’s adoption of a coastal identity and its representative logo, the term ‘Northern Beaches’ is still commonly taken to refer to the beachside suburbs rather than the larger Council area they are now located within.

History, social and infrastructural development

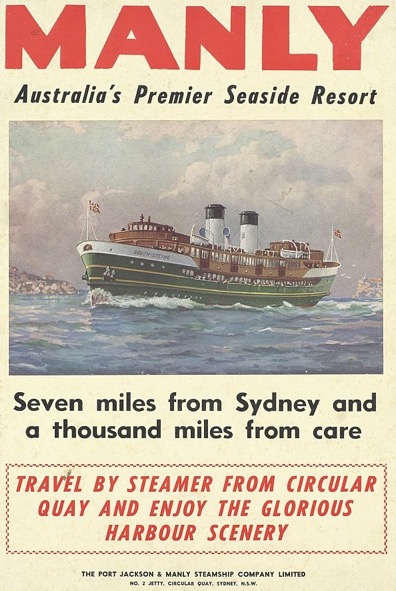

The Northern Beaches area forms part of the traditional lands of the Darramurra-gal nation, an Indigenous group who inhabited the region at the time of European invasion of Australia.6 In 1788 British captain Arthur Phillip encountered a group of Indigenous men and, impressed by their physique and bearing, named the location Manly Cove7 — a term that has subsequently been applied to an area slightly to the east of the actual encounter site. Manly Cove began to be settled by colonists in the early 1800s who were mainly involved in fishing and cattle raising, displacing the clan that had so impressed Phillip. The area underwent a major expansion in the mid-1850s after English entrepreneur Henry Gilbert Smith purchased c. 200 acres between the harbour and surf beaches and erected a wharf on the harbour side and hotels on the harbour and beach sides (Butler and McDonnell, 2011: 349-350). Tourism received a further boost in 1875 when the Port Jackson Steamship Company was established.8 The company provided a regular service between central Sydney and Manly and invested in amenities in Manly to attract patrons. The company’s publicists also penned the evocative and perennial slogan ‘Seven miles from Sydney and a million miles from care’ (Figure 4). The development of Manly as a tourist centre arguably reached its zenith in the early 1930s with the creation of a large, shark-netted, open-water pool and diving tower at Manly Cove. In parallel with these developments, Manly developed as a residential and commercial centre and as the transport hub for the region with the establishment of a tram network that developed in several stages from 1903, running west from Manly Pier, towards the Spit, and north to Narrabeen. This line spurred the development of residential suburbs along its routes9 until it closed in 1939, by which time road-based transport had superseded its operation (McCarthy, 1995). At the northern end of the coast, Palm Beach was established in the 1890s and Avalon in the 1920s.

As identified above, the width of the Middle Passage and the height of the surrounding, steeply rising slopes acted as a deterrent to the construction of a bridge across it until 1924, when a wooden structure was erected across the narrow neck known as the Spit (which a ferry service had operated across since 1834). As residential estates were opened up along the Northern Beaches, traffic increased and a wider bridge was erected in 1958. While this initially enhanced traffic flows it became increasingly congested as a greater volume of commuter vehicles funneled into its approaches. Further delays resulted from the bridge having a divided middle section that is raised at set times to allow water vessels to move between its elevated span. Traffic issues are often perceived as a deterrent for residents of suburbs on either side of the bridge to cross it for other than essential purposes10 (although residents from suburbs further to the west and north-west appear less deterred and substantially increase traffic at weekends and in summer by crossing the Spit or the six-lane bridge at Roseville, on the upper reaches of the Passage, which opened in 1974). These transport issues are part of what Creswell (2010) has described as the “constitution of mobilities” of a community: a phenomenon that includes patterns, rhythms and experiences of movement (and of related stasis) that effect the 43.4% of Northern Beaches’ population that works outside of the council area (id.community, 2016: online).

In the context described above, the ferry services that run between Manly Wharf and the CBD are not simply an incidental form of transport but rather provide a key shared experience for a significant number of residents. As Vannini (2012) has identified, ferry trips serve to define space through the experience of commuting through it and also provide a variety of socio-cultural and/or environmental experiences. In the case of the Northern Beaches, these include patterns of commutes to the ferry wharf, periods of waiting on it for ferries to arrive, boarding of ferries, the duration of the trip itself and then the rhythms of docking and disembarkation. While regular commuters are obviously aware that Northern Beaches is not an island, their ferry experience is closely similar to those that islanders experience when commuting from Staten Island to lower Manhattan (USA) or from Hong Kong’s outer islands to its Central Piers.

One of the major attractions for visitors and for those remaining or buying into the area since the 1850s has been its beach culture, which has been key to its development and identity during the 20th and 21st centuries. While the NSW Government banned swimming in Sydney Harbour and coastal surf beaches in the 1830s (ostensibly on grounds of public decency), it eventually abandoned its policy in 1902-03 due to widespread flouting of the restriction, leading to a boom in aquatic activities in locations such as Bondi Beach and Manly. The world’s first surfing competition (and an associated carnival) was held at Manly in 1908 and board surfing was introduced to Manly in the following year. Manly and the beaches to its immediate north developed a significant local surfing culture from the 1930s on and in 1964 the first World Surfing Championship was held at Manly’s ocean beach, attracting over 60,000 spectators.

As Fiske, Hodge and Turner (1987) have identified, the beach has been a key (and privileged) nexus for Australian masculinity and sporting activities for over a hundred years. The Australian masculinity evident in such settings has been overwhelmingly white and the beach has been a white space par excellence (Morris, 1992). The latter factor has been exaggerated by the pattern of non-European post-War migrants settling away from the coasts of Australian cities, in areas such as the south and southwest of Sydney and in the southeast and west of Melbourne. As a result of such patterns, while the ethnic diversity of Sydney has increased considerably since the 1940s, the population of the Northern Beaches has remained largely British-Irish in origin. This aspect was enshrined in early series of the media product most associated with the area, the TV soap opera Home and Away (1988-present). Set in the fictional community of Summer Bay, with exterior sequences filmed around Palm Beach, the series has been popular internationally for showing the experiences of beach-orientated Australians in an attractive coastal locale. For most of the program’s first two decades its cast were overwhelmingly Euro-Australian, until objections were raised by cast members (Wilkins, 2012). While minor adjustments have been made, the show continues to promote a vision of Australia that accords with the demographic profile of its production locale.

The homogeneity and sense of insular community in the Northern Beaches has resulted in periodic manifestations of antipathy to outsiders. Whereas this tendency is less marked in Manly, which is heavily reliant on and aflush with tourists all-year around, beachside suburbs to its north have seen regular assertions of localism, particularly by young males intent on limiting what they perceive as the overcrowding of ‘their’ prized surf beaches. This is a common international tendency (Scott, 2003) that has manifested itself in various forms around the Northern Beaches, such as graffiti, verbal harassment and, on occasion, violence,11 but has not, to date, resulted in the large-scale conflicts that occurred in Cronulla in 2005 (discussed further below). Violence has also been a problem internally, particularly at certain times in the 1970s-1990s, with regard to young men, drugs and alcohol, issues of public order and the sexual harassment and/or assault of women (see, for instance, Young’s insider account, 1998). A series of investigative media reports on the period have sought to expose these issues (e.g. Murphy, 2009 and the ABC TV series Barrenjoey Road, 2018) while others have concentrated on violence at particular venues such as Manly’s Steyne hotel (Buchanan, 2009).

There is also evidence of broader types of antipathy to outsiders. Indeed, the first instance of the term ‘insular peninsula’ we have uncovered refers to acts of vandalism at Avalon Baptist Church in 1985 and threats made against the church’s US pastor John Hirt concerning his congregation’s support for refugees. These prompted Hirt to assert that the racist National Action group had infiltrated what he referred to as “the insular peninsula” (Gerish, 1985: 7). But while National Action, founded in 1982, was intermittently active across Sydney in the 1980s and early 1990s there is no indication that it was particularly prominent in the Northern Beaches (Sewell, 1995). Analyses of federal election voting patterns in 1980s-present in the federal seats of McKellar (comprising the northern and central section of the Northern Beaches) and Manly-Warringah (the south) also show that fringe right wing parties have gained little traction.12 That said, two recent, long-term Liberal incumbents, Bronwyn Bishop (McKellar, 1994-2016) and Tony Abbott (Manly-Warringah, 1994-2019), were strongly conservative and overtly supportive of traditional white Australian values. But while the views of these two MPs may be perceived to reflect the predominant political complexion of the area, centrist independent candidate Zali Steggall’s victory over Abbott in Manly-Warringah in 2019 represented a repudiation of Abbot’s extreme social conservatism. The latter reflects the more progressive social orientation of the constituency area, which has seen novel developments such as an increasingly visible Brazilian community over the last five years (Kimmorley, 2017). State election results show a similar pattern to federal voting patterns across the two of the three Northern Beaches constituencies, Wakehurst and Pittwater with Manly being distinct by virtue of electing centrist independents Peter Macdonald (1991-1999) and David Barr (1999-2007) before returning to the Liberals. Overall, this pattern confirms research conducted by Forest and Dunn (2007: 709) that identified a low level of ‘classic’ racism in the Northern Beaches but a greater aversion to multiculturalism and cultural change in general.

While the previous paragraphs introduced the term ‘insular peninsula’ in a critical context, it is more commonly used by locals with ironic affection to acknowledge their strong sense of locality and their attachment to place. There is also a level of self-consciousness about the cozy and economically privileged insularity that prevails in many parts of the Northern Beaches. Such aspects are also inscribed within locally produced commodities. Modus Operandi Brewing Company (based in Mona Vale), for instance, produces an ‘Insular Peninsula’ series of craft beers, which they promote as dedicated to “all things weird and wonderful about the Northern Beaches”. The term is also often used in a positive manner in local real estate and tourism promotion, such as the following (markedly overblown) characterisation published in the Manly Daily:

They call it the insular peninsula, and for good reason. The northern beaches of Sydney may as well have a passport checkpoint on the Spit Bridge. Head north of the snarling, filthy city and you enter a better version of Sydney. The northern beaches has the lowest obesity rate in Australia, an above average median taxable income and takes up eight of RP Data’s 10 most expensive suburbs in Sydney. Add to that the fact that the ocean makes it a few degrees warmer in winter and cooler in summer, and you have it — paradise. (Dengate, 2014: online)

Presumably unintentionally, the author effectively re-states the pitch of the Port Jackson and Manly Steamship Company’s ‘seven miles from Sydney and a thousand miles from care’ campaign. The subjective perception of the Northern Beaches as a peninsula and its promotion as such recalls the previously discussed “artefact” of naming French peninsulas as presqu'îles in order to increase their attractiveness to visitors and property purchasers. In these manners, the geography of the Northern Beaches area and its natural assets provide fertile ground for a community that is as willing to acknowledge its insular peninsularity as external reporters are to repeat that characterisation.

A similar — albeit differently nuanced — sensibility is evident in the Barrenjoey peninsula, whose homogeneity and insularity within the Northern Beaches both exemplifies the region’s characteristics and constitutes an actual insular peninsula within a more figurative one. The most distinct attributes of the cluster of suburbs between Newport and Palm Beach are their affluence, related high property values and limited accessibility by public transport. The local community’s assertion of its insular peninsularity is notably more discrete than the larger region’s. One example is a car sticker that first circulated in the 1990s and continues to be seen on local vehicles (Figure 5).13 Unaccompanied by any slogan, the image is primarily recognisable by residents of the Barrenjoey peninsula, as it comprises a rendition of its cartographical outline. Like the broader Northern Beaches identity, residents of the Barrenjoey peninsula have a degree of self-consciousness about the area’s affluence and exclusivity, as was ably parodied in the short film series Avalon Now (2015-) directed by local film makers Bruce Walters and Felix Williamson.

One of the most telling indications of a desire to maintain insularity was the local response to the NSW Government’s 2014 ‘Northern Beaches Transport Action Plan’ (NBTAP), which set out to address the area’s transport issues. Amongst the various projects proposed was the construction of a rail link from central Sydney to Manly and up north along the Northern Beaches and the construction of a motorway tunnel that would bypass Spit Bridge. Despite being launched by a NSW Government headed by Manly MP Mike Baird, the report’s emphasis on increasing the ease of transport between the beaches and the city resulted in a mixed response in the Northern Beaches, with many perceiving these new transport options as likely to undermine the geographical and infrastructural factors that created the area’s cherished insularity.

There are various ways of interpreting negative responses to elements of the NBTAP. To use a framework that has become increasingly prominent in recent years, the proposals were seen locally to have the potential to lead to ‘over-tourism’ (see Seraphin, Gladkikh and vo Than [eds], 2020),14 whereby key sites are crowded in manners that impede locals’ everyday inhabitation of their locale. With particular regard to the proposed rail link, Manly mayor Jean Hay was a vocal opponent of the proposal on these grounds (Kay, 2015: online). While over-tourism is increasingly regarded as a legitimate and pressing concern for locals in destinations as diverse as Venice or The Galápagos, Avila’s 2016 discussion of local opposition to the construction of a Northern Beaches rail line approached the response from a different angle. His thesis argued that proposals for increased transport access are often opposed by “local elites” who balance the ease with which they might access other areas of the city with the ease that residents of other areas of the city might access theirs. In the case of the affluent, culturally homogenous Northern Beaches, Avila identifies concerns over access by non-locals as part of a process by which “racism and xenophobia relate to and strengthen (and are strengthened by) elite localism” and which manifest themselves through “denying the rail access to ‘troublesome’ suburbanites” (2016: 40). Whether such a characterisation is accurate or not, such issues appear to have had a far lower profile in local debates about the proposed motorway tunnel, with both former Australian Prime Minister Abbott and his opponent, centrist socially-progressive Steggall, being supportive of the tunnel proposal during their 2019 election campaigns. While there has been some local opposition to the tunnel it has tended to centre on environmental or logistical aspects rather than social impacts. At time of writing, the rail link project appears to have been shelved indefinitely whereas the development of the tunnel is proceeding (Laird, 2020).

Sutherland Shire

Characterising and Defining the Area

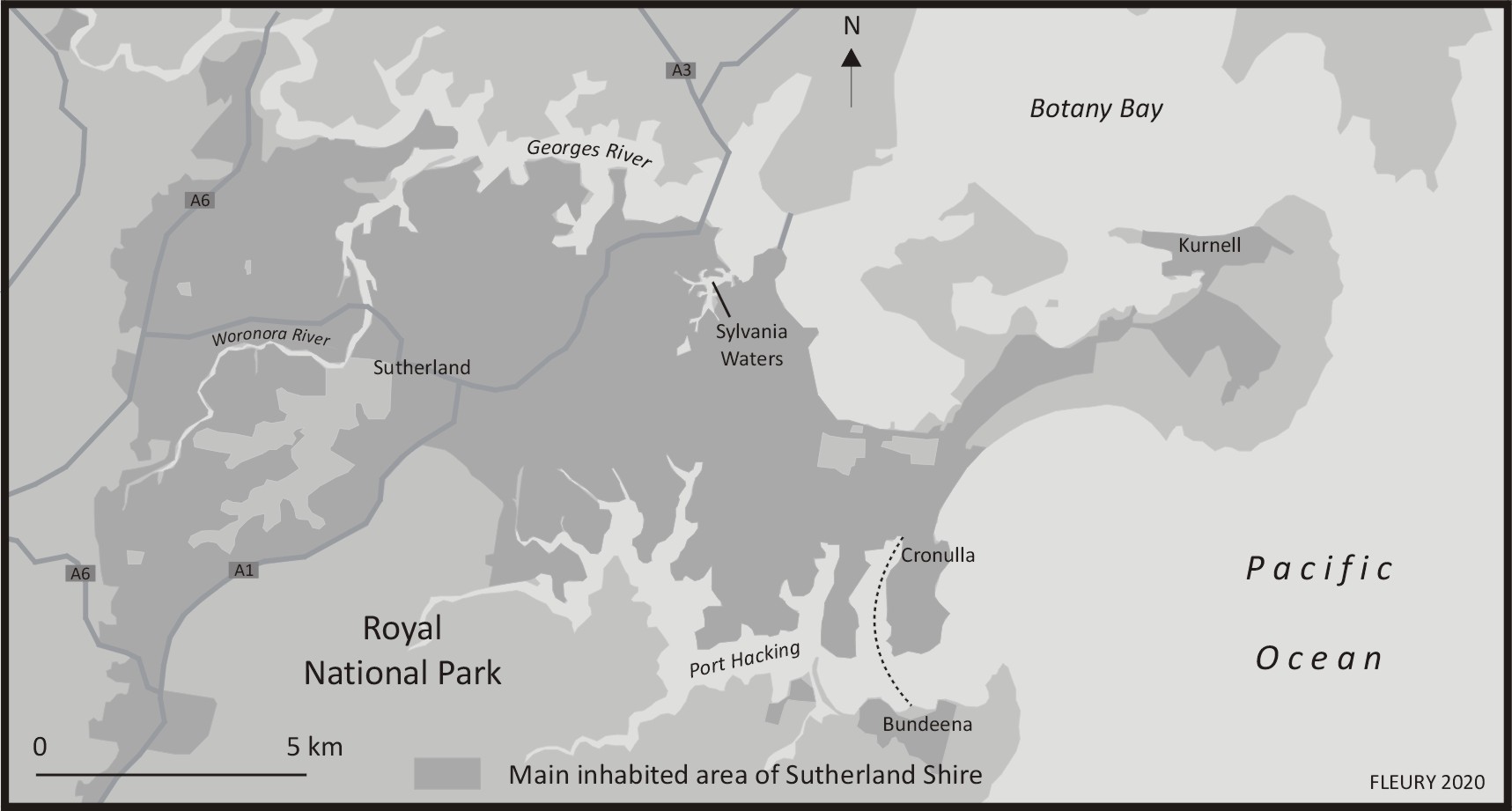

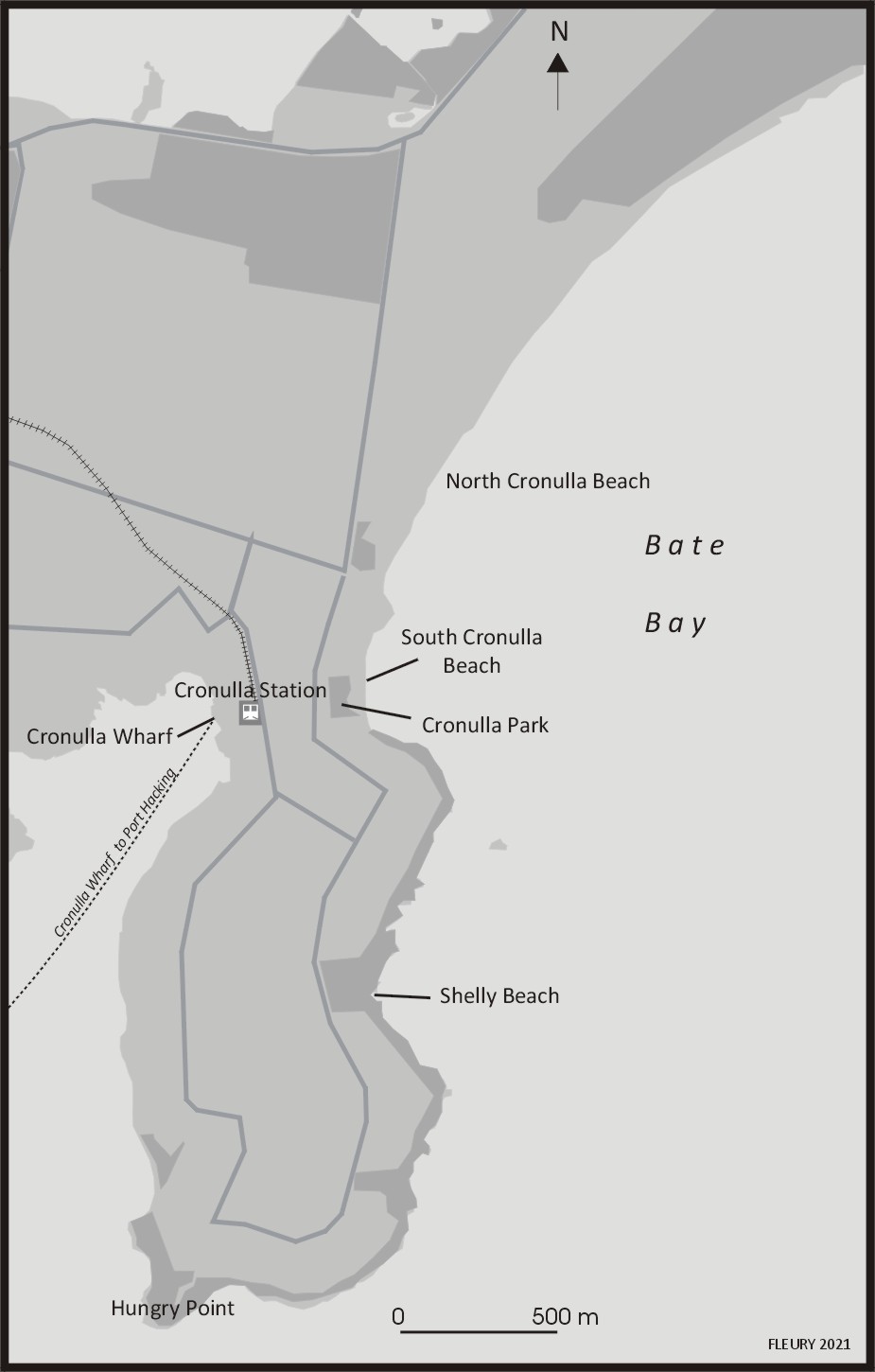

Sutherland Shire was established as a local government area in 1906 and has an estimated population of 218,464 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016b), the majority of whom inhabit the peninsula area bounded by the Port Hacking inlet (to the south) and Botany Bay and Georges River (to the north) and the adjacent area to the west around the lower reaches of the Woronora River (Figure 6). The remainder of the Shire’s population live in small settlements located at Bundeena, Malanbar and Wurrumbul (on the south shore of Port Hacking inlet) and at Waterfall, on the far south-western edge of the Royal National Park. Bundeena and Warumbul are only directly accessible from the central peninsula via a passenger ferry service from Cronulla (or a long, looping road link that heads south through the national park before cutting back north to access) and Warumbul is also only accessible by a road route through the national park. As a result, the latter three settlements (together with Waterfall) are not usually considered as parts of the central entity known as ‘The Shire’ and the latter term will be used to refer to the populated peninsula area shown in Figure 6 (rather than the larger local government territory).

There is much debate about the origins of the name Sutherland. One theory is that the area took its appellation from Forbes Sutherland, a sailor on Captain Cook’s ship Endeavour, who died and was buried at Kurnell in 1770, with a nearby promontory being named after him. Another is that the location of The Shire — relative to Sydney — led it to be named ‘Souther(n)land’; while another traces it to the Minister of Lands, John Sutherland who named the area in the 1870s. In 1905 the ‘Local Government (Shires) Act’ was passed by the NSW Parliament, requiring lands not under the control of existing municipalities to be allocated to councils and in the following year. Sutherland Shire was proclaimed and a provisional council nominated. ‘Shire’ is an antiquated English word often used interchangeably with the term ‘county’ and, in an Australian context, evokes “a non-metropolitan, rural or semi-rural local government area exhibiting a rustic culture” (Watt, 2014: 2). Though often used in a derogatory manner, residents of The Shire embrace the appellation as a point of difference from other Sydneysiders. Rather than separate villages or suburban enclaves, residents of the 42 suburbs of The Shire have tended to perceive themselves as a single entity, with many united in their desire to preserve the area from succumbing to the urban bustle of Sydney.15 This was no more apparent than in 1993, when the NSW Government proposed removing the suffix ‘Shire’ from the official name of the area. Outraged, lobby groups and local elected officials, such as the then mayor, Ian Swords, petitioned against its removal on the basis that the designation was “an essential part of the area’s identity” (Watt 2014: 225). Their campaign forced the Local Government minister, Gerry Peacocke, to retract the proposal and allow the appellation to remain (Local Government Focus, 2011).

History, society and infrastructural development

It is with a sense of civic pride that Sutherland Shire Council lays claim to an “iconic episode in the story of Australia” in using the title ‘Birthplace of the Modern Nation’ on its website, in memorabilia and in digital heritage collections (Nugent, 2008: 198). For it was in The Shire, at a place now known as the Kurnell Peninsula, that Lieutenant James Cook first landed on Australian soil on 29th April 1770 and encountered Indigenous Australians for the first time. The Indigenous inhabitants were the Gweagal, a clan of the Dharawal Indigenous people who inhabited a large area south of Botany Bay that extended to Jervis Bay on the NSW south coast, west past Camden and down to Goulburn, near the state’s border with the Australian Capital Territory (Watt, 2014: 11). The Gweagal had been using Botany Bay’s fish and shellfish resources for an extended period before the arrival of the British. As the site of first contact, the Shire carries a historical burden for colonial Australia’s past treatment of Indigenous Australians. This is no more apparent than in recent debate about the iconic encounter and the proposed $50 million redevelopment of the Meeting Place Precinct (formerly known as Captain Cook’s Landing Place Reserve) at Kamay Botany Bay National Park to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Cook’s arrival (Nelson, 2018). Considered by some as an attempt to sanitise the clash between Cook and Indigenous warriors into a “meeting of two cultures” (Nelson, 2018), the redevelopment involves construction of a visitor centre with retail and exhibition spaces, cafe, picnic and BBQ pavilions, arrival monuments and a new ferry wharf (Crone and Bangawarra, 2020). At the same time there have also been calls for the removal of Cook’s head from the Sutherland Shire Council logo (Figure 7) and its replacement with a symbol of the local Dharawal people (Trembath, 2020). These debates highlight the centrality of The Shire in continuing processes of nation-building and the importance of place in shaping cultural narratives.

Initial pioneers in The Shire established small settlements and pushed Indigenous people to the south and west of their traditional territories. While early attempts to establish industries such as coalmining and a whaling station proved unsuccessful, many settlers found work as timber-getters, orchardists, market gardeners, poultry farmers, railway workers, fishermen and oyster farmers (Ashton, Cornwall and Salt, 2006: 3). After the First World War, greater mobility, including privately owned cars, attracted holidaymakers and visitors to newly established hotels and guesthouses in the area, but the area’s relative isolation continued to appeal to those without social power and/or those living outside of socially accepted norms. Remote from central Sydney, illegal stills, unlicenced nightclubs serving alcohol and illegal gambling and sporting venues operated with a level of impunity and underworld figures were frequent visitors to the area. The area’s isolation was significantly modified by the opening of a branch rail line that linked Cronulla to Sutherland and connected it to the greater Sydney rail network in 1939. The Shire’s population subsequently increased by 510% (from 28,000 to 143,000) between 1947 and 1968 (Watt, 2014: 3). Many of the new arrivals were young, low-income families of Anglo-Celtic heritage who bought land during the post-war housing boom to realise ‘the Great Australian Dream’ of home ownership in an area that was then regarded as separate from metropolitan Sydney. Contemporary depictions of The Shire in tourism brochures and real estate advertisements market a lifestyle address replete with surf beaches, golf courses, recreational waterways and parks. Today, many of the initial low-cost fibro and tile shacks have been replaced by modern concrete developments with commanding views across The Shire’s 19 beaches and 200km stretch of waterways and bays.

Insularity

The Sutherland Shire local government area is one of the least ethnically diverse areas of Sydney (Norquay and Drozdzewski, 2017), with 77.7% of residents born in Australia and the most common ancestries English 27.6%, Australian 26.3%, Irish 9.5%, Scottish 6.9% and Italian 3.2% (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016). Unlike other pockets of Sydney, lower population mobility in The Shire has contributed to its homogeneity (Johnstone, 2013). The Sutherland Shire’s reputation for insularity is also the subject of academic research (Barclay and West, 2006: 76) and local historian Bruce Watt has referred to the area as “almost an island” (2012: 9).

There is one particular material and conceptual barrier between Sutherland Shire and the greater Sydney region that looms large in local consciousness. Over the course of the second named author’s 30-year residence in The Shire, it has been common to tease outsiders by asking whether their passport was stamped at Tom Uglys Bridge — a steel truss structure erected in 1929 that connects the St George area to the north, at Blakehurst, and the Sutherland Shire to the south, at Sylvania.16 Today, the designation Tom Uglys Bridge refers to two vehicle carriageways, the original now listed on the NSW State Heritage Register and a duplicate bridge constructed in 1987 to enhance traffic flows. While not the only gateway into The Shire, (the Captain Cook and Alford’s Point bridges, constructed in 1965 and 1973 respectively, being the other crossings by road), Tom Uglys has a physical and symbolic presence that demarcates space and acts as a steel sentinel promising to keep ‘undesirables’ out. The bridges are significant for the fortress mentality that is so often associated with residents of this locale. As discussed further below, in December 2005, following the Cronulla riots that gripped southern Sydney, Tom Uglys, Captain Cook and Alford’s Point Bridges were transformed into literal checkpoints where police blockades restricted in-bound traffic and car boot searches were conducted. Bridges typically open up forms of access and overcome natural boundaries by connecting “two impossible points” but, in The Shire, bridges more closely resemble “border-technologies” (Bishop, 2008: 174) where the bridge, rather being than a pathway of mobility, becomes a boundary marker separating the spaces it was designed to connect.

Among non-residents, the term ‘insular peninsula’ is often used to describe the perceived self-sufficient isolation of inhabitants of The Shire in a derogatory manner that often ascribes a parochial mentality and narrowness of outlook to residents. However, locals tend to conceive the Shire more positively. Indeed, Watt (2014: 4) asserts that there has a tendency for locals to regard the area as ‘God’s country,’ evoking its resemblance to a prelapsarian Edenic ‘paradise’ — a new ‘Arcadia’ unspoiled by industrialisation and urban malaise (Ashton, Cornwall and Salt 2006: 248). Such epithets are not without basis. Indeed, the rich biodiversity of The Shire is a testament to conservationists who have fought to protect the area from agricultural development, rapid urbanisation and short-term interests (Ashton, Cornwall and Salt, 2006: 13). Most notable among The Shire’s green spaces is the Royal National Park, established in 1879, where remnants of ancient Aboriginal habitation can still be found in rock shelters, rock carvings and cave paintings (Neve, 1971). The Royal National Park has been described as a ‘living museum’ and some of the original plant species collected in 1770 by botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander survive today at Kamay Botany Bay National Park.

Specific areas of The Shire also reveal pockets of insularity within the broader peninsula. Sylvania Waters (Figure 8), a suburb located at the eastern end of the Georges River, is a prestige Finger Island Canal Estate (FICE) development built in the 1960s. The estate was modelled on similar developments in Florida (Hayward and Fleury, 2016: 29-32) and was constructed using reclaimed parcels of land from the surrounding Gwawley Bay. The project was only the second of its kind in Australia, having been preceded by Surfers Paradise in 1959. In order to construct the estate, mangrove swamps were reclaimed and an 8km retaining wall was built to encase the proposed 800 homes, half of them with water frontages. Home designs required prior approval by the developer and Council and were inspired by (so-called) Cape Cod and Colonial-style homesteads as well as contemporary architecture. As Hayward and Fleury (2016: 36-37) have identified, FICEs are designed to be exclusionary and insular, constituting enclaves within broader social spaces, and the result was a lavish and exclusive Shire address — the only one of its kind in Sydney where “your boat is on the same level as your car” (sylvaniawaters.com: online). In 1992, the area was the setting of Australia’s first reality television program Sylvania Waters, co-produced by the ABC and BBC. The 12-part series followed a nouveaux riche blended family in the Baker-Donaher clan of 48 Macintyre Crescent, whose domestic squabbles and brassy characters attracted international media attention. A legacy of the show was that Sylvania Waters became regarded as the ‘soap-opera suburb’ and its limited public transport options only strengthened the area’s perceived insularity (Stapleton, 2017).

Sutherland Shire encompasses two federal electoral divisions, the seats of Hughes and Cook, that for decades have been dominated by conservative party politicians. Named after former Prime Minister Billy Hughes, the seat of Hughes covers 369 sq km of the Sutherland Shire and part of neighbouring Liverpool City Council. When it was formed in 1955 the seat was held by Labor but for nearly a quarter of a century it has been held by the Liberal Party. According to election analysts, the changing demography of voters in the area from trade-qualified workers in state owned corporations and utilities to those largely self-employed has been responsible for the declining Labor vote in this seat (Green, 2019). Extreme right wing parties gained a small slice of the vote in the late 1990s but have declined in subsequent years. One potential reason for this is that former Liberal member Craig Kelly, who has held the seat of Hughes since 2010, is known for his extreme right-wing views and climate change denialism. Smaller in size, the electoral division of Cook spans 94 sq km, including parts of Sutherland Shire (Cronulla, Kurnell, Caringbah, Miranda and Sylvania) and areas north of the Georges River (Blakehurst, Monterey, Sans Souci and Sandringham). From 1906 until the redistribution of electoral boundaries in 1955, Cook was a Labor stronghold. It was not until 1969 when the modified division of Cook was established that the seat fell to the Liberal Party and has remained a safe Liberal seat since 1975. Extreme right wing parties gained a small but significant vote in the 1990s, with the Reclaim Australia Party polling 3.96% in 1996 and One Nation polling in third place in 1998 and 2001 (with 8.32% and 5.97% respectively) but have declined in subsequent years. The current sitting member for Cook is the Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, first elected in 2007, whose conservatism and ‘family values’ have been enshrined in national politics, as discussed further in the conclusion. As in federal politics, the Liberal Party has dominated State election results in Sutherland Shire across the four constituencies, Cronulla, Miranda, Heathcote and Holsworthy. Despite a brief spike of support for One Nation in 1999 (gaining 7.6% in Cronulla and 7.2% in Miranda), only Miranda and Holsworthy stood One Nation candidates in 2019 (gaining 7.1% and 8.1% of votes, respectively). Overall, federal and state results point to the dominance of the Liberal party and mainstream players in both Federal and State politics in the Sutherland Shire.

Beaches and related youth subculture

Cronulla is the main beach area in The Shire (Figure 9) and is central to its social and recreational activities (Norquay and Drozdzewski, 2017: 91). Much like Sydney’s Northern Beaches, Cronulla draws locals and tourists alike with its 5km stretch of white sand and is the only Sydney beach accessible by train. The post-war Baby Boomer generation skewed the demographic of The Shire and in 1966 almost 42% cent of the Shire’s 134,058 people were under the age of 20 years (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). By day, Shire youth were drawn to Cronulla’s sand and surf and, by night, they congregated at the North Cronulla Surf Lifesaving Club to drink and watch live entertainment. By the early 1960s surfing had become so popular that the Council was forced to impose a licensing system on board riders and separate surfers and bathers in a “spatial reorganization of the beach” (Ashton, Cornwall and Salt, 2006: 177). Violent clashes between rival teenage subcultures were not uncommon in the 1960s and often resulted from territorial disputes between local surfers and groups of youths from outside the Shire. Police crackdowns on gangs of hooligans at Cronulla made local news reports in 1963 and, in the following year, the state member for Cronulla, Ian Griffith, raised in Parliament the problem of youth brawling at seaside venues. Ashton, Cornwall and Salt have asserted that territorialism was “entrenched” at Cronulla beach and those ‘bankies’, ‘towners’ or ‘billies’, predominately from Sydney’s Western Suburbs, who had been travelling to Cronulla beach since the train line was extended in 1939, were not welcome by locals (206: 190). Respectability and social order were perceived to be under threat with the newly established surf culture closely associated with youth delinquency, promiscuity and the promotion of a hedonist lifestyle. This culture was profiled in Gabrielle Carey and Kathy Lette’s 1979 novella Puberty Blues (adapted eponymously as a film and then TV series, in 1982 and 2012 respectively). Cronulla Beach was also the setting for Channel Ten’s reality television series The Shire (2012), which drew frequent comparisons to MTV’s Jersey Shore (2009-2012), and featured lusty young people lying on beaches in scanty attire. The series was controversial among locals, particularly with Sutherland Shire Mayor, Carol Provan, who responded to a promotional clip for the series by telling journalists that she would “install a boom gate at the border of the region to stop production of the show when it begins filming” (unattributed, 2012: online), sparking a spirited discussion on the Daily Telegraph’s Facebook page (2012). The series was made but Provan’s comments point to The Shire’s sensitivity and reputation for insularity and, in the context of the television series, to the beach as a site of social exclusion.

The Cronulla riots

The beach’s prominence as a motif in national iconography was emphasised in the opening ceremony of the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games when the stadium floor transformed into a beach, replete with aquatic fauna. A national fascination with beach culture is not surprising given more than 90% of Australians live along the country’s coastal fringes (Barclay and West, 2006: 75-6) and beaches have dominated Australian tourism campaigns since the 1980s. As previously discussed with regard to the Northern Beaches, the beach is identified as the site of foundation myths for Anglo-Australia that privilege whiteness, maleness and hegemonic interests. In such accounts, the beach stands as a material and imaginary stage where anxieties about Australian culture, national identity, belonging and social exclusion are performed and contested (Lems, Gifford and Wilding, 2016). These theoretical considerations came into sharp focus in the Summer of 2005.

On 11 December 2005, violent scenes unfolded at Cronulla when an estimated 5,000 people attended a rally to ‘reclaim the beach’ after months of simmering tensions between Caucasian Australians and young men reported to be of Middle Eastern appearance from Sydney's western suburbs. In the weeks before the riots, locals complained to police and on talkback radio of loutish behaviour at the beach including a series of assaults on surfers, lifeguards and racially and sexually motivated slurs and threats against female beachgoers (Barclay and West, 2006: 77). Police had received intelligence that both Caucasian males and men of Middle Eastern appearance were planning to converge at Cronulla Beach on 11th December (NSW Police, 2006: 35). The nearby Cronulla Police Station had 92 officers on duty and another 68 on standby (ibid: 38). From 8am that day, crowds began to gather at Dunningham Park and North Cronulla Surf Life Saving Club and became increasingly rowdy. Young men carried cases of beer down the main road into Cronulla on their way to the beach and some wore tee shirts that read ‘You flew here, we grew here’. What started as a typical summer’s day with backyard family barbecues, surfers cresting waves and revellers spilling out of local cafes, restaurants and pubs, became an alcohol-fuelled clash between angry youths. In a place where locals often remark on the degrees of affinity between residents (‘everyone knows everyone’), it was clear that opportunists (or what locals call ‘blow ins’), several of whom were later identified as members of the ultra-nationalist Australia First Party and the Patriotic Youth League, descended on Cronulla to heighten racial tensions (Hartley and Green, 2006: 344). When a rumour spread that men of Middle Eastern appearance were soon to arrive at Cronulla Railway Station, a 10-minute walk from Dunningham Park, a large crowd ran to the station and footage of the ensuing assault of two men and of police wielding batons was broadcast internationally (NSW Police 2006: 41). In all, 26 people were treated for injuries and 16 arrested and charged with 42 offences including “malicious damage, assaulting a police officer, affray, offensive conduct, resisting arrest and numerous driving offences” (Watt, 2016: 236).

On the evening of the riot and the following night, groups of men of Middle Eastern appearance congregated in large numbers at Cronulla and the beachside suburbs of Maroubra and Brighton-Le-Sands, attacking people and property in what the police report determined to be a “well-planned and coordinated” reprisal and with further violent acts occurring the following day (NSW Police, 2006: 9). While the reprisal attacks occurred simultaneously at key locations in Sydney and were “unprecedented in public disorder anywhere in Australia” (NSW Police, 2006: 49) they received less media attention than the Cronulla riot itself (Watt, 2016: 236). To restore order, police erected barricades and locked down the Shire to locals. The second named author’s family were driving home via the newly opened Woronora Bridge and were stopped by police who checked the addresses on our driver’s licences before letting us through. Though we had joked for years about fortressing the Shire, the literal barricading of outsiders — even for public safety reasons — was a frightening development and, as Watt describes, local tourism suffered in the post-riot climate (2016: 236).

In critical analysis of the Cronulla riots, various geo-political events have been causally linked, including the September 11 terrorist attacks in the United States in 2001, an ensuing moral panic about a Muslim terrorist threat in Australia (Johns, Noble and Harris, 2017) and the bombing of Paddy’s Bar in Bali, which was targeted at Australian patrons, in October 2002. Others have argued that national debates about asylum seekers and the demonising of the Muslim ‘Other’ precipitated the violence at Cronulla (Poynting, 2006) and/or attribute a marked “strain of racism in the Australian national identity” in the period (Barclay and West, 2006: 75) arising from increasing political conservatism in Australia under the influence of then Prime Minister John Howard and Pauline Hanson, the leader of Australia’s far-right party One Nation. For Norquay and Drozdzewski (2017), news coverage of the Cronulla riots “substantially impacted the community’s identity, leading many to believe residents of Cronulla and, by extension, those of the entire Sutherland Shire, were racist”. Representations of The Shire as “white, insular and privileged” deflected the image of racism from other, more affluent and predominantly white areas of Sydney (2017: 103). Indeed, The Shire’s insularity and socio-cultural homogeneity appeared to magnify an event that became pluralised (as ‘the Riots’) and that were dubbed “Australia’s worst race riots” (O’Riordan, 2005).

A series of local reconciliation initiatives took place in the wake of the riots. Senior members of the Cronulla beach surfing community, including some of those who took part in the violence, issued a written public apology after two days of talks with representatives from Sydney’s Lebanese Muslim community (Unattributed, 2006: online). Stars of the sporting field also joined forces to condemn the violence. The well-known Canterbury Bulldogs Rugby League player, Hazem El-Masri, who is of Lebanese background, and Jason Stevens, the ex- Cronulla Sharks player and Cronulla local, denounced the violence in public statements. In 2009, local MPs, surf lifesavers from The Shire and young people from the Muslim community in Bankstown walked the Kokoda Trail in Papua New Guinea (the site of a bloody battleground at which 600 Australians lost their lives during the Second World War) in an attempt to heal the rift. Tensions have now dissipated somewhat and there have been no significant recurrences of racially motivated violence between groups of youths in the area since.

Conclusion

During the global COVID-19 crisis Sydney (and NSW in general) remained largely free of the virus from winter through to mid-summer 2020 until an outbreak occurred around Avalon in mid-December that led to the whole of the Northern Beaches Council area being placed into lockdown. This prompted a fresh mobilisation of the figure of the insular peninsula in the media, with headlines such as “The ‘insular peninsula’: Reason Sydney cluster may not be as worrying as it might otherwise have been” (news.com.au, 2020: online) and items identifying the area’s insularity as an asset in a public health crisis. The aforementioned report also quoted Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s statement that “[t]hose of you who know Sydney will know that the peninsula is a very cohesive community that tends to stick to itself” (ibid). As MP for Sydney’s other insular peninsula, Morrison was well-aware of the paradigm he was mobilising. As this article has identified, the perceived insular peninsularities of The Shire and the Northern Beaches do not so much arise from their being paradigmatic almost-islands, connected to larger adjacent land areas by narrow isthmuses (such as Gibraltar, Newfoundland’s Avalon or Egypt’s Sinai) rather than a combination of relative peninsular isolation (in terms of transport access routes), demographic homogeneity and local perceptions of/identification with insularity. Perceived threats to the homogeneity (and to more general social stability) of these areas can manifest themselves in periodic and localised hostility towards outsiders. But, as the second section of this article outlined, in the Cronulla riots of 2005 the area served as a rallying point for broader metropolitan and national tensions that were enacted in Sutherland’s insular peninsula. This parallels the manner in which both areas have been perceived by conservative Australians and related media outlets to represent a more socio-culturally homogenous (i.e. predominantly white) Australian past and, therefore, as standing for that past in a manner that merits protection. This symbolic function facilitates the projection of racist and/or exclusionary attitudes on to the areas despite patterns of demographic change within them. It is obviously significant that the insular peninsulas have provided Australia with two recent prime ministers, Tony Abbott (2013-15) and Scott Morrison (2019-), who have been outspoken in their support of conservative anglophone values. But while they may have been nourished by homogenous electorates, it is also significant that they — and Craig Kelly, the MP for Hughes — are increasingly out-of-step with local and national attitudes to topics such as Indigenous rights and climate change. As previously discussed, Abbott was voted out in favour of a progressive independent candidate in the 2019 elections, reflecting the increasing socially progressive politics of Manly-Warringah, and — despite Morrison’s sustained support for him — Kelly was persuaded to leave the Liberal party in 2021 and now sits as an independent.

It is useful to return to Fleury and Raoulx’s characterisation that several new, urban peninsular developments (such as Presqu’île Rollet in Rouen) have characterised themselves as presqu'îles in order to give themselves the “appeal of an island and its adjacent waters” while remaining “within the city, accessible, but associated with the sea and with the rêverie of being on an island” (2016: 19). The marketing of these inner-city areas thereby identifies metropolitan centrality and accessibility as key selling points. By contrast, Sydney’s two insular peninsulas are neither central nor particularly accessible. Indeed, their very distancing from the city (as celebrated in Figure 4) is key to their identities. In a period of metropolitan sprawl and rapid development, cities and neighbourhoods are changing in manners that undermine longer-term senses of local character and identity. The insular peninsulas — distanced from the city centre and located on finite, water-hemmed areas — are thereby distinct for being outside of cycles of regeneration that see new populations move in and transform areas. The peninsulas’ beaches remain unchanging assets and the coastlines that define them provide clear boundaries. In this manner, almost islandness is an important factor but not the key one in determining the insular nature of their communities. Similarly, there are degrees of insularity within each peninsula resulting from the particular desirabilities and related property values of either engineered environments, such as the Sylvania Waters FICE, or natural locales such as the Barrenjoey peninsula. In this manner, insularity operates in tiers, enacted differently in each location but within an encompassing peninsular context.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Peter Doyle, Brent Keogh, Susie Khamis, Greg McDonald, Alex Mesker, and Carl Zimring for their various assistances and/or comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Endnotes

Bibliography

- ABC News (2009) Riot police called in as Australia Day celebrations turn ugly, ABC News 26th January: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2009-01-26/riot-police-called-in-as-australia-day/273828

- ABC TV (2018) Barrenjoey Road (Australian TV documentary series)

- Adams, T.E, Holman Jones, S and Ellis, C (2015) Autoethnography: Understanding Qualitative Research, New York: Oxford University Press

- Ashton, P, Cornwall, J, and Salt, A (2006) Sutherland Shire: A History, Sydney: UNSW Press

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016a) ‘Northern Beaches (A)’: https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/LGA15990 — accessed 18th September 2020

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016b) ‘Sutherland Shire (A)’: https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/LGA17150 — accessed 18th December 2020

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020) ‘Sutherland Shire (A)’: Population and Dwellings in LGAs — New South Wales: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/2106.01966?OpenDocument — accessed 30th September 2020

- Avila, J (2016) ‘Elite Localism and Inequality: Understanding affluent community opposition to rail network expansion within the political economy of Sydney’, Bachelors Honours thesis, University of Sydney

- Barclay, R and West, P (2006) Racism or Patriotism? An eyewitness account of the Cronulla demonstration of 11 December 2005, People and Place, v14 n1: 75-85

- Basar, B (n.d.) ‘Manly Island, Sydney’, Opus: https://www.opus.travel/@burcu/manly-island-sydney

- Bishop, P (2008) Bridge, London: Reaktion Books

- Bursill, L, Jacobs, M, Lennis, D, Timbery-Beller, B and Ryan, M (2001) Dharawal: The story of the Dharawal speaking people of Southern Sydney, Jannali: Kurranulla Aboriginal Corporation

- Carey, G and Lette, K (1979) Puberty Blues, Sydney: McPhee Gribble

- Channel 10 (2012) The Shire (Australian reality TV series)

- Cresswell, T (2010) ‘Towards a Politics of Mobility’, Environment & Planning D n28: 17 — 31

- Crone and Bangawarra (2020) ‘Kamay Botany Bay National Park, Kurnell Stage 2 Master Plan Proposal Design Summary Report’, NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/parks-reserves-and-protected-areas/park-management/community-engagement/kamay-botany-bay-national-park-public-consultation/major-infrastructure-works

- Cross, H (2019) ‘Guringay voices heard as City of Sydney removes references to Ku-ring-gai/Guringai’, National Indigenous Times 20th December: https://nit.com.au/guringay-voices-heard-as-city-of-sydney-removes-references-to-ku-ring-gai-guringai/

- Daily Telegraph (2012) ‘Is the reality TV show The Shire tacky or just a bit of fun?’, Daily Telegraph Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/dailytelegraph/posts/is-the-reality-tv-show-the-shire-tacky-or-just-a-bit-of-fun/393281740683181/ — accessed 12th December 2020

- Dengate, C (2014) ‘Which of the seven tribes of the northern beaches do you belong to?’, Manly Daily 14th June: https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/newslocal/northern-beaches/which-of-the-seven-tribes-of-the-northern-beaches-do-you-belong-to/news-story/5f3a34039ed4c6e993b2e23e0aff8e2e

- Domain (2015-) Avalon Now (Australian web video comedy series)

- Dunphy, M.J (1935) ‘Narrow Neck and Blue Mountains National Park’, The Katoomba Daily 31st October: 4

- Ellis, C (2009) Revision: Autoethnographic Reflections on Life and Work, Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press

- Fiske, J, Hodge B, and Turner G (2016) Myths of Oz: Reading Australian Popular Culture (Kindle edition), New York: Routledge

- Fleury, C and Raoulx, B (2016) ‘Toponymy, Taxonomy and Place: the concepts of presqu’île and péninsule’, Shima v10 n1: 8-20

- 465 Productions (for MTV) (2009-2012) Jersey Shore (Australian reality TV series)

- Gerish, G (1985) ‘Activist target of racist attacks’, Tharunka n3: 7

- Green, A (2019) ‘Hughes, Sydney Southern Suburbs’, ABC Live Election Blog: https://www.abc.net.au/news/elections/federal/2019/guide/hughes

- Harris, A (2012) ‘Sutherland mayor Carol Provan launches attack on producers of The Shire reality TV show’, Daily Telegraph, 20th March: https://www.adelaidenow.com.au/entertainment/celebrity/sutherland-mayor-carol-provan-launches-attack-on-producers-of-the-shire-reality-tv-show/news-story/aff75218ea727abe5d8f852985d5fdd8?sv=1054d5115466b6eaaa93dad92cab366c

- Hartley, J and Green, J (2006) The public sphere on the beach, European Journal of Cultural Studies v9 n3: 341-362

- Hayward, P and Fleury, C (2016) ‘Absolute Waterfrontage: Road Networked Artificial Islands and Finger Island Canal Estates on Australia’s Gold Coast’, Urban Island Studies 2: 25-49

- Hayward, P and Fleury, C (2020) ‘Bounded by heritage and the Tamar: Cornwall as “almost an island”’, Island Studies Journal v15 n1: 223-236

- id.community (2016) ‘Northern Beaches Council area: Residents' place of work’, Northern Beaches Council: https://profile.id.com.au/northern-beaches/residents

- Johns, A, Noble, G and Harris, A (2017) ‘After Cronulla: “Where the Bloody Hell are we now?”’, Journal of Intercultural Studies v38 n3: 249-25

- Johnstone, T (2013) Cricketers Pitch for Top Properties, Sydney Morning Herald 28th April 2013: https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/cricketers-pitch-for-top-properties-20130427-2ilay.html

- Kay, B (2015) ‘Manly Mayor Jean Hay fires up over suggested train line for northern beaches’, Daily Telegraph July 23d: https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/newslocal/northern-beaches/manly-mayor-jean-hay-fires-up-over-suggested-train-line-for-northern-beaches/news-story/b521b734ca1b6ca9d133303a2d4a9e64

- Kimmorley, S (2017) ‘Suddenly, Sydney is the new home for the next generation of Brazilians’, Business Insider 19th May: https://www.businessinsider.com.au/suddenly-sydney-is-the-new-home-for-the-next-generation-of-brazilians-2017-5

- Laird, P (2020) ‘Is another huge and costly road project really Sydney's best option right now?, UoW Media 19th May: https://www.uow.edu.au/media/2020/is-another-huge-and-costly-road-project-really-sydneys-best-option-right-now.php

- Lems, A, Gifford, S and Wilding, R (2015) ‘New myths of Oz: the Australian beach and the negotiation of national belonging by refugee background youth,’ Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies v30 n1: 32–44

- Local Government Focus (2011) ‘Why Southerland Shire is not a city’: https://www.lgfocus.com.au/editions/2011-02/why-sutherland-shire-is-not-a-city.php

- McCarthy, K (1995) The Manly Lines of the Sydney Tramway System, Transit Press

- Morris, M (1992) ‘On the Beach’, in Grosberg, L, Nelson, C and Treichler, P (eds) Cultural Studies, New York: Routledge: 450-478

- Murphy, D (2011) ‘Paradise lost: Northern Beaches Dirty Secrets Exposed’, Sydney Morning Herald 29th January: https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/paradise-lost-northern-beaches-dirty-secret-20110128-1a8e0.html

- Nelson T (2018) ‘Rewriting the narrative: Confronting Australia’s past in order to determine our future’, NEW: Emerging scholars in Australian Indigenous Studies, Sydney: UTS ePress

- New South Wales Government (1997) ‘Environmental Planning Policy #50 — Canal Estate Development’: https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/whole/html/inforce/1998-03-13/epi-1997-0596

- New South Wales Government (2014) ‘Northern Beaches Transport Action Plan’: https://friendsofmonavale.weebly.com/uploads/5/5/6/4/55647135/northern_beaches_transport_action_plan.pdf

- Norquay, M and Drozdzewski, D (2017) ‘Stereotyping the Shire: Assigning White Privilege to Place and Identity’, Journal of Intercultural Studies v38 n1: 88-107

- NSW Police (2006) ‘Strike Force Neil, Cronulla Riots: Review of the Police Response — Report and Recommendations’: https://www.abc.net.au/mediawatch/transcripts/ep38cronulla1.pdf

- Nugent, M (2008) 'The encounter between Captain Cook and Indigenous people at Botany Bay in 1770 reconsidered', in Veth, P, Sutton, P and Neale. M (eds) Strangers on the Shore: Early Coastal Contacts in Australia, Canberra: National Museum of Australia Press: 198-207

- O'Riordan, B (2005) ‘Race riot turns Sydney's suburbs into battleground’, The Guardian 12th December: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/dec/12/australia.bernardoriordan

- Orford, S (2017) ‘Good things in my neighbourhood’: https://www.liveinthepresent.co.uk/2017/05/good-things-in-my-neighbourhood/ — accessed 18h September 2020

- Patterson, R (2018) ‘Northern Beaches Council spends $320k on new ‘identity’ including logo and website’, Manly Daily 2nd August: https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/technology/northern-beaches-council-spends-320k-on-new-identity-including-logo-and-website/news-story/759f4c1313ddcce6ec787d2402e5ccc1

- Poynting, S (2006) What caused the Cronulla riot? Race and Class n48: 85-92

- Reddit (2016) Posting by u/MrVido and responses: https://www.reddit.com/r/australia/comments/4rzc95/please_help_me_identify_this_weird_bumper_sticker/

- RealSurf Surfers’ Forum (2006) ‘Appeal for help on North Narrabeen assaults’, phpBB: http://forum.realsurf.com/forum/viewtopic.php?t=5718

- Scott, P (2003) ‘We shall fight on the seas and the oceans… We shall: Commodification, localism and violence,’ M/C Journal v6 n1: https://journal.media-culture.org.au/mcjournal/article/view/2138

- Seraphin, H, Gladkikh, T and vo Than, T (eds) (2020) Overtourism: causes, implications and solutions, London: Palgrave Macmillan

- Seven Network (1988-) Home and Away (Australian TV drama series)

- Sewell, B (1995) ‘“Australia full: Asians out! White supremacists in!” A study of the dynamics of the Australian National Action Movement in Australia’, BA Honours thesis Victoria University, Melbourne

- Sian 9 (2011) ‘Manly island?”, Tripadvisor: https://www.tripadvisor.com.au/ShowTopic-g255060-i122-k4370698-Manly_Island-Sydney_New_South_Wales.html

- Southern Star Entertainment (2018) Puberty Blues (Australian TV drama series)

- Stapleton, D (2012-2014) ‘Sylvania Waters: a new lease on life for Sydney’s “soap-opera suburb” built on swampland’, Sydney Morning Herald 20th September: https://www.domain.com.au/news/sylvania-waters-a-new-lease-on-life-for-sydneys-soapopera-suburb-built-on-swampland-20170920-gykll2/

- Sutherland Shire (nd) ‘Kurnell — Birthplace of a modern nation’: https://www.sutherlandshireaustralia.com.au/local-towns/kurnell/

- Sylvania Waterways (2020) ‘History’: http://www.sylvaniawaters.com/history-of-sylvania-waters/

- Trembath M (2020) ‘Sutherland Shire Council to consider changing Captain Cook logo to include Dharawal culture’, The Leader 15th June: https://www.theleader.com.au/story/6791137/council-logo-change-urged/

- Unattributed (2012) ‘Sutherland Mayor Carol Provan launches attack on producers,’ Herald Sun 20th March: https://www.heraldsun.com.au/entertainment/television/sutherland-mayor-carol-provan-launches-attack-on-producers-of-the-shire-reality-tv-show/story-e6frf9ho-1226305384254?sv=1befcf0607ce68f22b5b49690e5266b5

- Unattributed (2003) ‘Taking the Waters’, Sydney Morning Herald 1st March: https://www.smh.com.au/national/taking-the-waters-20030301-gdgcm4.html

- Unattributed (2006) ‘Surfies say sorry, condemn violence’, Sydney Morning Herald 15th December: https://www.smh.com.au/national/surfers-say-sorry-condemn-violence-20051215-gdmmwm.html

- Vannini, P (2012) Ferry Tales: Mobility, Place, and Time on Canada's West Coast, London: Taylor and Francis

- Walters, B and Williamson, F (2015) Avalon Now: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CNXfsXe0bQA

- Watt, B (2012) ‘Towards a Sutherland Shire Narrative’, Sutherland Shire Historical Bulletin v15 n2: 9-13

- Watt, B (2014) The Shire: A Journey Through Time, Sydney: Sutherland Shire

- Wedesweiler, M (2015) ’15 things all Northern Beaches residents know’, Sydney Morning Herald Domain 18th November: https://www.domain.com.au/living/15-things-all-northern-beaches-residents-know-20151117-gky5f6/

- Wikitravel (n.d.) ‘Palm Beach’: https://wikitravel.org/en/Sydney/Palm_Beach — accessed 20th September 2020

- Wilkins, G (2012) ‘Star hits out at Home and Away racism’, Sydney Morning Herald 16th February: https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/tv-and-radio/star-hits-out-at-home-and-away-racism-20120216-1ta23.html

- Wiralleaks (2018) ‘Morton v 1. Information Commissioner 2. Wirral Metropolitan Council’: https://wirralleaks.wordpress.com/tag/insular-peninsula/ — accessed 18th September 2020

- Young, N (1998) Nat’s Nat, Nymboida: Nymboida Press

- Zie, D (n.d.) ‘Manly Island,’ World of Shazie: http://www.worldofshazie.com/manly-island-australia/