Doorway to Europe: migration and its impact on island tourism

Abstract

Lampedusa is today best known in relation to migration. The island has confronted one migration crisis after the other for the past three decades, resulting in extensive media coverage. Whereas Lampedusa, a small island in the central Mediterranean region, has an economy mainly based on tourism, its name remains associated with migration, which is believed to negatively impact the island’s image and the performance of its tourism sector. On the other hand, migration has to some extent, put Lampedusa on the map, helping the island gain popularity. The island’s existing tourism model is based on sun, sand, and sea (3S) and is made attractive by its beaches, one of which has ranked as the best beach in the world, as well as by marketing efforts presenting Lampedusa as 'the Caribbean island of the Mediterranean'. However, migration and 3S are camouflaging other resources that are key to the island’s image. Lampedusa has a terrestrial nature reserve as well as a marine protected area that is home to several charismatic marine species, making it an ideal ecotourism destination. These resources can be used not only to depict a more representative image of the island but also to develop a sustainable tourism model that is suitable to a small island.

Keywords

migration, island, image, Mediterranean, ecotourism, protected areas

Introduction

When one speaks of islands in Europe, the image of holidays and sunshine comes to mind (Rigas, 2012). Image has been shown to be an important influence in the selection of vacation destinations (Baloglu and McCleary, 1999; Chaulagain et al., 2019). However, crisis can impact island tourism and destination image (Almeida and Machado, 2019).

Islands in the Mediterranean Sea that represent the external border of the European Union (EU), such as Lampedusa and Lesvos, have faced various crises because of irregular migration (Bernardie-Tahir and Schmoll, 2014) — the movement of persons that takes place outside the laws, regulations, or international agreements governing the entry into or exit from the state of origin, transit or destination (IOM, 2021). Like other European islands, they have become points of transit for irregular migrants and asylum seekers (Bernardie-Tahir and Schmoll, 2014), the latter being individuals seeking international protection (IOM, 2021). Lampedusa in particular has experienced one migration crisis after another (Orsini, 2015). Such crises refer to complex and generally large-scale migration flows that often lead to considerable vulnerabilities for affected communities, and pose serious migration management challenges in the longer term (Tantaruna, 2016). Migrants from Africa have been crossing the sea in the central Mediterranean region to seek international protection or to seek a better future in Europe (Melotti et al., 2018). Such islands have come to represent the doorway to Europe. This has been given symbolic form by the Italian artist Mimmo Paladino’s monument 'Porta di Lampedusa — Porta d'Europa' ('Doorway to Lampedusa — Doorway to Europe'), erected on Lampedusa in 2008 in memory of migrants who lost their lives at sea (Cuttitta, 2014; Salvatori, 2015) (see Figure 1).

Several islands in the Mediterranean region have over the years transformed their economies and become dependent on tourism, which in return produces a domino effect on other smaller economic sectors. However, high levels of migration are feared to degrade an island’s reputation, impacting tourism and thus economy (van't Klooster, 2012; Orsini, 2015; O’Healy, 2016; García-Almeida and Hormiga, 2017; Ivanov and Stavrinoudis, 2018; Melotti, 2018; Tsartas et al., 2020). Because irregular migration to southern European islands draws extraordinary media attention (Bernardie-Tahir and Schmoll, 2014), islands that have been associated with extensive migration have frequently attempted to rebrand themselves (Donovic, 2020).

The relationship between migration and tourism has increasingly come under the spotlight (eg Feng and Page, 2000). However, its influence on tourism destination development and competitiveness through its effect on reputation has received scant attention even if it can provide relevant data-based ideas for various regions (García-Almeida and Hormiga, 2017). While Lampedusa has received much attention in the press and literature with respect to migration crisis and policy, few studies have addressed migration’s impact on island tourism in the Mediterranean region (eg Melotti et al., 2018; Di Matteo, 2019; Tsartas et al., 2020). This article considers the image that operators use to market Lampedusa and local stakeholders’ assessments of how news related to migration impacts the island’s image. This article also studies how tourists perceive the island before and after their visit and the impact of migration on their experience throughout their stay on the island. The article furthermore explores how migration can produce both positive and negative side effects, creating a new niche tourism while simultaneously impacting tourism and governance. In light of attempts by islands to shift to sustainable forms of tourism, this work suggests a new image that better represents the island and its tourism product, an image that must be supported by local and regional authorities as well as by the private sector that plays an important role in the island’s tourism economy.

Area of study

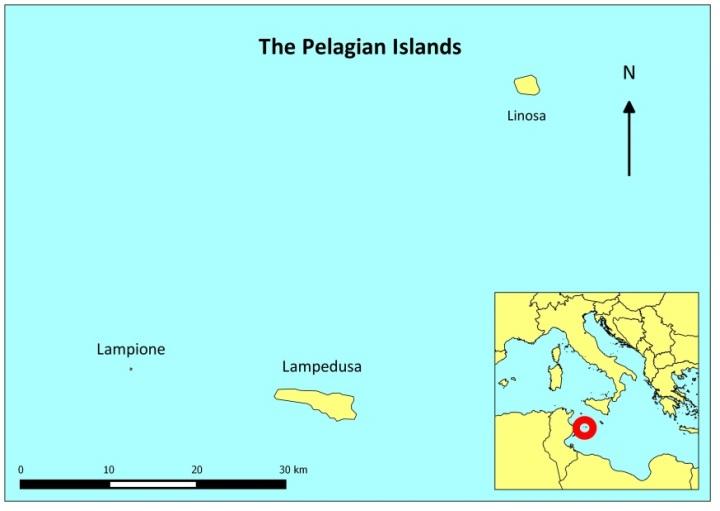

Lampedusa is part of the Pelagian archipelago, which consists of the islands of Lampedusa and Linosa and the uninhabited islet of Lampione (see Figure 2). Positioned in the Strait of Sicily, the Pelagian Islands are closer to Africa than to Sicily itself (O’Healy, 2016). Lampedusa is located at about 130 km from the Tunisian coast and 250 km from the Sicilian coast (La Manna et al., 2014). Lampedusa is roughly triangular in shape, with a surface area of 20.2 km2 (Ferlito et al., 2013), a length of 10 km, and a maximum width of about 4 km. It is characterised by steep cliffs to the north (with heights ranging from 50 m to 133 m) and gentle slopes to the south and southeast (Ferrari, 2006), which are interrupted by a number of valleys (La Mantia et al., 2011). The coastal perimeter of 42.81 km (ISTAT, 2017) is also characterised by inlets, beaches and numerous caves, contributing to the island’s touristic value (SISPlan/IGEAM, 2012).

Lampedusa’s climate is characterised by long, hot, dry summers and very mild winters (Surico, 2020). Precipitation is irregular and low (less than 350 mm/yr and average monthly values rarely exceeding 60 mm) and is mostly concentrated between October and March. The average yearly temperature is about 19 ºC. Temperature range tends to be quite wide: the coldest month is February (9–14 ºC), while the hottest month is August (24–30 ºC) (La Mantia et al., 2011; La Mantia et al., 2013). Furthermore, the island is characterised by constant wind, which is present for around 80% of the entire year (Chamard et al., 1998; Surico, 2020).

Lampedusa is administered by the municipality that is responsible for both Lampedusa and Linosa and forms part of the province of Agrigento in Sicily (Ferlito et al., 2013; O’Healy, 2016). The Pelagian Islands’ total population is 6355, with most living in the main village on the island of Lampedusa, also known as Lampedusa (Comune di Lampedusa e Linosa, 2015). Between 2001 and 2011, the population increased by 7% but those falling within the age range of 0–29 decreased by 8% (Ferrari, 2006; Comune di Lampedusa e Linosa, 2015). Most tourists (85%) visit the archipelago in the summer, with 50,000 reaching the island in August. Tourist arrivals amount to around 130,000 annually. Tourists are primarily attracted to the archipelago by the natural environment as well as by available excursions and services, including accommodation structures and restaurants (Comune di Lampedusa e Linosa, 2015; Surico, 2020).

The Island of Lampedusa has an airport that connects the island to Sicily through daily flights to Palermo and Catania. During the summer period, local consortia organise charter flights to a number of destinations, including Milan, Venice, Turin, Verona, Bologna and Rome (Ravazza and Anselmo, 2010; Lampedusa Pelagie — Informazioni Turistiche, 2020). Two companies offer a circular ferry service stopping at Porto Empedocle (Agrigento, Sicily), Linosa and Lampedusa. The part of the voyage between Porto Empedocle and Linosa takes seven hours whereas the part of the voyage between Linosa and Lampedusa takes a further two hours. The company Liberty Lines links Linosa and Lampedusa through a hydrofoil service which takes one hour. The service runs year round, weather permitting (Agius et al., 2021). In the summer period, the hydrofoil service also operates between Linosa and Porto Empedocle and it takes up to three hours to complete the journey (Domina et al., 2012; Longhi et al., 2006; Nicolini et al., 2008).

Up until around 1990, the fishing sector and bluefish canning industry dominated Lampedusa’s economy and employment for nearly all workers on the island. Over time, several locals abandoned the fishing industry and transitioned to tourism livelihoods; today, most locals obtain their main income from tourism-related activities (Orsini, 2015). Some regard tourism work as the only way to make a living on the island (O’Healy, 2016). The agriculture area in the archipelago accounts for 4.44 ha (Ferlito et al., 2013). Agricultural activity mostly occurs on Linosa and represents a very small share of the local economy. The fishing sector still plays important social and cultural roles on the islands, yet the sector’s economic importance has decreased despite the presence of small companies focusing on canning and packaging of fish products (Comune di Lampedusa e Linosa, 2015).

The Pelagian Archipelago’s natural environment is of outstanding importance. It is closely associated with turtle nesting sites, including the Spiagga dei Conigli on Lampedusa, with an area of 6000 m2 (the largest beach on Lampedusa), and the Spiagga Pozzolana di Ponente on Linosa, with an area of 1100 m2. These sites represent the most-monitored beaches in Italy where the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta carretta) lays its eggs (Piovano et al., 2006). Local flora is of exceptional interest and include 250 flowering plants (Surico, 2020) as well as several endemic plants both on Lampedusa and Linosa (Pasta et al., 2012; Pasta and La Mantia, 2013). The island of Linosa hosts the largest European colony of the seabird Scopoli’s Shearwater (Roatti et al., 2019).

Due to its environmental importance, the archipelago has been subject to a number of designations both at the national level and the EU level through four Natura 2000 sites. The nature reserve on Lampedusa was instituted in 1995, and its management was entrusted to Legambiente Sicilia (Prazzi etal., 2013). The area consists of 3.7 km2, equivalent to 18% of the territory of Lampedusa, and is situated towards the south of the island, between Vallone dell Acqua to the west and Cala Greca to the east. The site is divided into two zones in which different activities and land uses can take place in line with the environmental characteristics and management objectives (Barbagallo, 2003). The entire area lies within the Site of Community Importance (SCI) ITA040002 “Isola di Lampedusa e Lampione”, which covers two-thirds (67.81%) of the land surface of the island of Lampedusa (Sposimo, 2014).

Nearly half of the island of Linosa (49.5%) and the entire territory of Lampione fall within another nature reserve (Fattorini and Dapporto, 2014). This reserve, with an area of 2.65 km2, was established in 1997 and is managed by the Department of Rural and Territorial Development (former Forestry Authority — Azienda Foreste Demaniali) of the Sicilian Region (Sposimo, 2014). Much of the surface of the island of Linosa also falls within the Natura 2000 site SCI ITA04001 “Isola di Linosa”, which extends over an area of 4.35 km2, accounting for 80% of the island (EUR-Lex, 2015).

In 2002, a portion of the waters surrounding the Pelagian Islands was declared a Marine Protected Area (MPA) by the Italian Ministry for the Environment (La Manna et al., 2014). Its management was assigned to the municipality of Lampedusa and Linosa a year later, with the objective of protecting the area’s marine vegetation and fauna, biological resources, and geomorphology. The area covers 41.36 km2 and 46.28 km of coastline (Giardina, 2012). As with all MPAs in Italy, the MPA is managed through a system of zones. The sea area adjacent to the Spiaggia dei Conigli (Rabbit Beach) is one of the three areas that have been designated as Zone A (absolute protection) (Prazzi et al., 2013). The area is also designated as a SCI ITA040014 “Fondali delle Isole Pelagie” (EUR-Lex, 2015).

| Characteristic | Lampedusa | Linosa | Lampione |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density habitants/km² | 293.2 | 79.7 | 0 |

| Permanent population | 5,922 | 433 | 0 |

| Area (km²) | 20.2 | 5.43 | 1.2 |

| Coastline (km) | 42.81 | 11.7 | 0.75 |

| Highest point (m) | 133 (Albero Sole) | 195 (Monte Vulcano) | 36 |

| Tourist arrivals | 124,222 | 10,000 | / |

Methods

Research was conducted between 2013 and 2020, and two study visits were organised to the island in 2013 and 2016. Throughout this period, 35 interviews were held with stakeholders in order to obtain their views on various aspects related to tourism, the image of the island, and migration. Stakeholders interviewed included locals, tourism industry representatives, tourists, government officials and agencies, representatives of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and academics. Two subtypes of strategic informant sampling technique were used to recruit interviewees. The first is expert sampling, which involves the selection of ‘typical’ and ‘representative’ individuals. The second technique used is known as snowball sampling and involves asking an initial set of informants to propose other potential sample members (Finn et al., 2000). In the case of tourists, these were engaged through the organisation of an ecotour. An ecotour defined as “purposeful travel to a natural environment to interact, learn and experience other cultures, and to help local communities economically that work towards conservation and preservation of the ecosystem” (Khan and Su, 2003, p. 118). This ecotour was organised for 11 ecotourists. The trip lasted four nights, and the programme involved various ecotourism activities both in the nature reserves and in the MPA as well as excursions during which tourists could experience local traditions. Table 2 shows the distribution of stakeholders with whom interviews were conducted, while Table 3 shows the distribution of males and females.

Interviews were held face to face during the study visits, but necessary follow-ups or clarifications were done over the phone or via videoconference. This allowed the researcher to obtain information on changes in local government, policies adopted and developments in the field of migration throughout the pandemic. The concurrent use of face to face and online interviews has been used in tourism research (Power et al., 2017) since the use of virtual platforms also permits valid and high-quality interviews (Suryani, 2013). Given that small island societies are often quite divided, with individuals taking an intense interest in others (Baldacchino and Ferreira, 2013), given that local communities can feel uncomfortable or even suspicious in the presence of audio recorders (Parker-Jenkins, 2018), and given that the researcher was unknown to the local community, notes were taken during and immediately after each interview to ensure that an adequate pool of stakeholders agreed to participate in the interviews as well as provided relevant information.

| Count / Percentage | Stakeholders interviewed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affected locals | Tourists | Operators | Academics | Government, agencies, politicians | NGOs | Total interviews | |

| Count | 2 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 35 |

| Percentage | 5.7% | 31.4% | 34.3% | 8.6% | 5.7% | 14.3% | 100% |

| Count / Percentage | Gender | Total interviewees | Total interviews | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Count | 29 | 8 | 37 | 35 |

| Percentage | 78.4% | 21.6% | 100% | |

Interviews were held in Italian not to limit the pool of participants (most locals only speak Italian). Notes were written directly in English but key quotes were written in Italian. No interpretation or translation were required by the researcher. Interviews lasted around 45 minutes and were kept semi-structured and informal. This exploratory approach allowed the researcher to obtain as much information as possible on a topic that has received little attention in literature. No formal questions were prepared, but a checklist of topics derived from the literature review and the research plan was kept at hand to guide the researcher throughout the interview. There is a gap in the literature not only regarding the impact of migration on the island’s image but also on ecotourism development. Therefore, a series of topics were identified as providing information relevant to the research questions. Issues tackled during the interviews included: (1) the image used by tourism stakeholders, especially operators, to promote the destination; (2) the impact of migration on the island’s image; (2) the impact of migration on tourism and governance; (3) how migration has benefited the island's image; (5) the image of the island from the eyes of tourists before and after their visit; (6) whether the presence of migrants, (if any) impacted tourists’ experiences; and (7) the island’s ecotourism potential as an alternative to mass tourism and as a means to portray a more representative image of the island.

The use of a checklist ensured that a consistent range of topics was covered in each interview (Wearing et al., 2002) and allowed the researcher to ask supplementary questions or to ask the interviewee to explain the answers provided (Veal, 2006). Whilst effort was made to discuss all aspects with the various stakeholders, this technique provided flexibility in asking stakeholders questions that were relevant to them and focusing on their expertise. As per Dooley (2002), data collection through interviews was regarded as completed when experiencing exhaustion of sources, saturation of categories and emergence of patterns.

Once fieldwork was completed, all transcripts were prepared and the key quotes written in Italian were translated. Data collected were analysed manually following the approach adopted by Stoffelen (2019) to analyse tourism data collected from various stakeholders. Pre-coding involved the use of literature to derive starting points for data coding. The first coding step involved reading all transcripts and assigning initial category labels to each transcript separately, resulting in a list of topic labels representing the topics discussed. These were eventually compared, leading to merger, renaming, and deletion of repeated content and reorganisation under overarching themes. The literature review was eventually re-read and expanded, allowing further organisation of the themes and subcategories. This involved the iterated merger, deletion, splitting and creation of codes. The post-coding process involved including notes, observations and informal conversations carried out in the area of study and adding supporting remarks from available policy documents under relevant themes as well as the selection of key quotes on the basis of their representative and illustrative value.

Research ethics considerations were fulfilled through the University Research Ethics Committee (UREC) of the University of Malta.

Results and discussion

Migration has impacted the image of the island

Lampedusa has been marketed by tourism operators as "the tropical island of the Mediterranean" and "the Caribbean island in the Mediterranean" due to its beaches and crystal clear waters. However, this contrasts with the labelling of Lampedusa as the island of migrants. Between 1993 and 2018, just under 220,000 migrants arrived on Lampedusa (Surico, 2020). The surge in migrants in 2011 and the presence of migrants all over the island is believed to have caused a serious dip in tourist arrivals between 2011 and 2012. Tourism has since recovered (Surico, 2020), but the constant migration of third-country nationals has had a tremendous impact on Lampedusa’s image. Local stakeholders regard constant media references to migration, as confirmed by Melotti et al. (2018), and the disproportionate and constant presence of military and police forces on the islands (Kirby, 2016) are threats to attracting tourists. This resonates with findings by O’Healy (2016), who argues that both factors strengthen the link between migration and the islands. Several stakeholders interviewed supported this argument. An operator said, “A major issue on Lampedusa is the image associated with migration. This penalises the island.” Another operator added “Migration is an issue for the island’s image. If one goes on the internet and writes Lampedusa in a search engine, the first images to appear are boats full of migrants and presence of police/military forces. Only after scrolling down do you get to see the beaches.” A politician said, “The image of the island is a problem.” Proof of the problem with migration and its link to Lampedusa lies in the fact that a travel agency promoting holidays on Lampedusa emphasised that migration was a “problem of the past” (Martin, 2016). As outlined by Jauhiainen (2017), the migration situation and the role of the migration centre on the island has changed over the years. Moreover, migrant arrivals have fluctuated, and crises have continued to develop from time to time, as with the onset of the recent pandemic. Operators have nevertheless attempted to dissociate the migration image from the island.

Operators interviewed remarked that, whereas the migration issue did not halt tourism on the island, it had a negative impact. This was confirmed through the organisation of an ecotour to the island and tourists interviewed. When promoting a visit to Lampedusa with individuals who had an interest in islands and who had visited other central Mediterranean islands, some of those approached expressed a lack of interest in visiting the island due to its connotation with migration. Furthermore, on their return from the island, those who joined the ecotour had to rebut arguments linking Lampedusa to migration when encouraging friends and family members to visit the island due to its natural beauty. Similarly, an operator from Lampedusa said, “There have been recent attempts to target the foreign market, but apparently the migration image made operators overseas change their minds.”

While the island’s tourism season coincides with the migration season, the presence of the military on the island was not raised by tourists interviewed. Furthermore, contrary to the claims made, a search in main online search engines failed to include migration-related photos in the top-20 photos, with most photos in fact depicting beaches. Regarding the perceived image of the island as full of migrants, one operator said, “Some visit the island with a bad image of the island in mind. When they come over and see what Lampedusa truly is, they revisit the island.” In fact, tourists interviewed remarked that they saw no migrants on the island and that the news and images associated with the island did not reflect their personal experience. Visitors said they would recommend friends to visit the island. One NGO representative argued that the lack of presence of migrants was because, once migrants arrive on Lampedusa, they are transferred to Sicily.

While there is general agreement that the island has an image problem owing to constant media reports, this does not reflect the everyday scenario on the island, as confirmed by both locals and tourists. Furthermore, migration does not impact tourist experiences throughout their stay on the island. This implies that marketing efforts must be held in conjunction with travel bloggers, journalists, and media houses, the latter of which are considered to be the main culprit behind the false image portrayed for the island. Positive word of mouth through visitors helps fight this false perception as well.

Migration’s impact on ecotourism and governance

In terms of image, ecotourism operators believe that migration not only resulted in an inaccurate image of the island but also concealed its natural resources. One Lampedusa local said, “Journalists do not refer to the positive aspects of the island, such as its nature and history, but refer solely to migration.” A policymaker said, “We cannot continue to report about Lampedusa only in cases of emergency related to migration. We need to value the resources we have. We need to show that Lampedusa is not just about migration.”

Migration has also impacted enforcement of the MPA. Inadequate protection and enforcement were major concerns for NGO representatives from Lampedusa. They argued that local authorities involved in MPA enforcement, such as the coast guard, focused almost all their resources on migration and were thus unable to act against illegal activities within the MPA. The lack of enforcement and the resultant impact on marine life influences marine ecotourism activities. Previous studies have called for better enforcement within the MPA (Papale et al., 2012), but recent surges in migration by small boats, which are abandoned on the beaches and along the coast, have necessitated the coast guard dragging these boats to the harbour, once again shifting attention from enforcement. Local fishers said that several boats belonging to migrants had been abandoned at the sea, not only creating a hazard for fishing equipment such as nets but also damaging the MPA and marine life as fuel and oil end up in the sea.

Locals and operators expressed concern at the fact that the municipality and the mayor were focused on the migration crisis and had little time to spare for the challenges faced by locals, especially those related to tourism. One local said, "Migration is granted overwhelming attention, and the tourism sector is almost abandoned.” These remarks echo those found in the literature (eg O’Healy, 2016). The presumed emphasis on migration has also left an impact on Linosa, with one local saying that the municipality had paid little attention to Linosa since it was so preoccupied with Lampedusa and the migration issue.

On the other hand, one academic said, "The previous mayor has done a good job of managing the migration issue and giving the right image of Lampedusa as an island with a kind heart.” A local politician likewise contradicted the claims, saying, "The Municipality is not interested only in migration policy but also dedicates due resources to tourism. We do tackle the problem of migration, but it is unfair to say that we just take care of migration.” An operator also agreed that one could not just blame the mayor for this issue. Nevertheless, in 2017, the archipelago elected a new mayor, with migration playing a central role in the run-up to the local elections (Cavallaro, 2017). Migration seems to have left an impact on the islands’ politics as well as its image.

To address these challenges, promotional efforts need to focus on a more representative image of the islands and move beyond the emphasis on 3S, granting due attention to the nature reserve and the MPA. Furthermore, the MPA’s management body needs to invest more in enforcement to compensate for the stretched resources of the coast guard. The municipality must send clear messages of support to the tourism sector, including through support for the development of new tourism niches in order to reduce antagonism between migration and tourism. While the lack of attention given to Linosa can be linked to a core-periphery relationship (eg Baldacchino, 2015), migration has left such a heavy impact on the island’s image that many existing island challenges ended up being attributed to it.

Migration: ambivalent results

While islands frequently have altered representations (Baldacchino, 2015), Lampedusa is represented by a small dot that is barely visible on maps depicting the Mediterranean region. Because of the municipality’s limited power and its dependence on higher levels of government, Lampedusa receives limited promotion. Marketing of the island has been associated with particular occurrences, which are not necessarily positive but which attract media attention and thus end up promoting the destination.

Although the island has hosted tourism since the late 1960s, the start of Lampedusa’s tourism boom is frequently dated back to 1986, when two missiles were launched towards the island from Libya. While the missiles fell into the sea and caused no damage, this episode made Lampedusa famous in Italy and around the world, prompting mass tourism (Surico, 2020). Referring to the prior lack of awareness of the destination, one operator said, “Until the 1990s, Lampedusa was not featured on Italian maps. At the time, there were few hotels or apartments, and tourists used to live with locals. Gaddafi put the island on the map. Coverage on television and in newspapers made a big impact on promotion, and those who wanted to be isolated or adventurous started to visit the island.”

Stakeholders believe that migration has placed the island on the map in a similar manner as to with the two infamous missiles. In this regard, some stakeholders believe that the extensive media coverage (both domestically and internationally) devoted to migration indirectly promotes the island and leads to visits by various public figures and journalists. As a result of this increased awareness, tourism to Lampedusa has increased. One local said, “Due to migration, the Prime Minister, the Pope and the President of the Republic visited the island, and this also served to promote the island.” Lampedusa has furthermore received extensive attention because of its humanitarian role. In 2004, Lampedusa was awarded the Gold Medal of Civil Merit by the President of the Republic of Italy (Surico, 2020). Lampedusa is the only local community to have been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, and in 2017, its mayor was awarded the UNESCO Peace Prize for her humanitarian work (Melotti et al., 2018). In addition, several films and documentaries concerning migration have featured Lampedusa and been partly filmed on the island (Jauhiainen, 2017) including the highest-grossing Italian film in Italy to date Quo Vado? (La Repubblica, 2016). While this has further helped to portray an island of migration, it has also helped to promote the island as a tourism destination.

One NGO representative said, “Migration is a coin with two sides. As far as the destination image is concerned, it may be considered a negative thing, but on the other hand there are people who visit the island to pay tribute to the solidarity that locals have been showing towards migrants.” One politician said, “Migration is not just something negative for the island. There are those who visit the island because of the situation. Sensible people visit the island to see the centre and other artefacts related to migration with their own eyes.” The literature echoes stakeholders’ claims that migration has also produced benefits. Various personnel who visit islands in the Mediterranean due to migration crises get to see other elements of the respective islands and plan to return as tourists (Tsartas et al., 2020). Furthermore, it has been claimed that Lampedusa’s image as an “island of peace” has begun influencing its tourism, which is developing beyond 3S tourism to a more responsible niche tourism attentive to nature and cultural landscapes (Melotti et al., 2018).

While migration and the presence of a migrant detention facility along with the military on Lampedusa certainly had an impact, this impact was ambiguous. Hotel owners remarked that the presence of the military on the island was beneficial as officials made use of their services all year round, including in the off season, thus representing a positive economic impact on an island accustomed to the seasonal vagaries of 3S tourism. Surico (2020) recalls how, in some years, the arrival of military staff, journalists, and curious visitors prompted hoteliers and restaurateurs to cut short their winter breaks and operate between January and April when there are normally no tourists at all. Migration has ironically created a new tourism “niche” that includes human rights lawyers, police and army personnel, coast guard workers, journalists and government officials who visit the islands for reasons other than 3S. Melotti (2018, p. 40) writes, “Local community and tourism industry have metabolized migration, which seems to have become a new tourist brand. This gives international visibility, does not frighten tourists any longer and even attracts a new kind of niche tourism.” According to an NGO representative, migration can itself become an attraction. Some stakeholders even suggested that the yard full of boats confiscated from migrants on their arrival to the island could become a new attraction for visitors.

Migration and image problems during the pandemic

Lampedusa has become accustomed to the constant arrival of migrants. However, the arrival of migrants to the island post-March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, has raised tensions anew due to fear among the local population that migrants might introduce the virus to the island, leading to transmission of infection within a community that has limited health services. Furthermore, locals interviewed feared that because some of the migrants arriving on the island tested positive for COVID-19, this would ruin the "COVID-19 free" image that the island had claimed for itself and would thereby endanger the vital summer tourism season. In fact, cases of COVID-19 among migrants were not taken into account when reporting the number of cases on the island, thereby allowing Lampedusa to retain its "COVID-19 free" image until the end of summer (Agius et al., 2021).

In the context of rising tensions, the mayor assured locals that necessary measures were being taken, including that migrants were being tested and that no one was being allowed to leave the migration centre. The situation got out of control when a centre, which had originally been built to house under 100 people, became overcrowded, holding ten times that number and making social distancing impossible (BBC, 2020). Hundreds of migrants were transferred to Sicily, though not before being transferred to a cruise ship serving as an offshore island to quarantine migrants (Baldacchino, 2020). The maintenance of low infection rates on the islands has seemed to back up the decision to move the migrants and has been latched upon by some in the far-right political movement. While the problem was shifted to a larger island (Sicily), this was a political win for the island of Lampedusa, which had lobbied extensively in favour of quarantining migrants on boats left offshore.

While those working in the tourism sector expressed fear of a local contagion due to the arrival of migrants from the South, they were ready to compromise or find a balance between their health and their livelihoods. In fact, operators longed for the resumption of the transport links that had been suspended because of the pandemic and without which tourism could not be restarted. They welcomed tourists from Europe, including from northern Italy, which is the place of origin of most tourists visiting the island, notwithstanding that northern Italy was at the time considered a coronavirus red zone by Italian health authorities. This was also out of necessity as tourism is a major economic sector on which several other sectors depend. Notwithstanding the migration crisis, operators interviewed claimed that they managed to attract a high number of tourists between July and September 2020, without a single case of the virus being imported in this period, thereby bolstering local migration and tourism policies.

From 3S tourism to ecotourism

3S tourism is a leading attribute of island destinations in the Mediterranean (Alipour et al., 2020). This is also the case for Lampedusa (Di Matteo, 2019) due to dependence on domestic tourism that takes place in the summer season. Furthermore, although Lampedusa has few beaches, some of those it does have are outstanding, such as Spiaggia del Conigli, ranked by TripAdvisor as the best beach in Europe and also as the best beach in the world on several occasions (TripAdvisor, 2020). In addition, local operators who are responsible for most promotional efforts (Di Matteo, 2016) have branded Lampedusa as "the tropical island of the Mediterranean" and "the Caribbean island of the Mediterranean". This image is also communicated to travel journalists and bloggers, who subsequently spread this image to prospective visitors. The island thus receives an image associated with migration while operators simultaneously portray the island as a 3S destination. Neither of these representations are authentic or complete portrayals of the destination. Furthermore, the island has no long-term tourism development plan (Di Matteo, 2019). This is one reason why tourism mostly focuses on the summer season, which itself has significant economic and social impacts on the local community. The masses of tourists that exceed 10,000 visitors per week in August (Surico, 2020) place significant pressure on the island’s fragile ecosystem even if the island has managed to avoid the detrimental impacts of mass tourism (Di Matteo, 2019).

Lampedusa island boasts a nature reserve and an MPA that can serve as an ecotourism venue. Several small operators and NGOs interviewed have already started operating in this field, organising excursions such as guided walks and volunteering in the reserve, as well as snorkelling, diving and wildlife watching in the MPA. This form of tourism is suitable for Lampedusa since ecotourism activities, such as bird watching, can be practised not only in the summer season but also outside the summer months. Furthermore, this type of tourism will reduce the impact that large numbers of tourists leave on islands, including social tensions between locals who have to make a living mostly by competing for tourists within a single, brief season.

Apart from failing to portray its natural appeal, Lampedusa has also failed to capitalise on the image that the Pelagian archipelago can offer in terms of the differentiation between islands in the archipelago (Baldacchino, 2015). Whereas the island of Lampedusa is sedimentary, the island of Linosa is volcanic and thus offers different landscapes. This is confirmed by tourists who expressed high satisfaction with excursions conducted on Linosa, including observing volcanic phenomena, cycling, buying local products and snorkelling. Furthermore, the archipelago includes the uninhabited islet of Lampione, which is home to a colony of grey sharks and which is already frequented by ecotourism operators who organise specific excursions targeting this species. Despite its very small size, this islet harbours a rich array of plant and animal species (Cascio and Pasta, 2012). More recently, the endangered Mediterranean monk seal was spotted just off the coast of Lampedusa (ANSA, 2020). By promoting the natural dimension within the archipelago, Lampedusa can increase its competitiveness and counteract the image that commonly associates it with migration and 3S tourism.

It is also important to bear in mind that Lampedusa experienced another form of migration as well: that of the local population. While the island’s population has remained relatively stable over the past two decades, some young people who struggle to see a future for themselves in tourism have chosen to leave the island to study or work in mainland Italy. Work on the island is a major concern for young people (Vietti, 2019). Some have moved semi-permanently or permanently and return to visit relatives and friends from time to time. Emigration of residents from small islands has been linked to lack of job opportunities all year round due to the seasonal nature of tourism and the restructuring, decline or disappearance of traditional economic activities that historically sustained these communities (Peronaci and Luciani, 2015; Cooke and Petersen, 2019).

Ecotourism can help to tackle this challenge faced by locals. This is because ecotourism preserves traditional lifestyles and community livelihoods found in remote areas, including islands with limited income opportunities and poor infrastructural conditions, by providing them with new income opportunities through sources other than mainstream tourism (d’Hauteserre, 2006; Buerkert et al., 2010). This limits youth migration (Neleman and de Castro, 2016). In fact, ecotourism has gained tremendous importance in recent years as an effective instrument for enhancing the well-being of people living near protected areas (Mirsanjari, Molla, Zarekare and Ghorbani, 2013).

Conclusion

Mass tourism operators have been portraying Lampedusa as "the tropical island in the Mediterranean" or "the Caribbean island of the Mediterranean," emphasising 3S tourism. This contrasts with the widespread image of Lampedusa as an island of migration. Local stakeholders believe that migration crises and the constant associated media reports have damaged the island of Lampedusa and contributed to a false picture of the island and of what it can offer visitors. Many travellers are hesitant to visit the island simply because of this image.

Notwithstanding the perceived association with Lampedusa and migration and its impact on tourism, tourist arrivals have continued to grow (ENAC, 2018), and the Pelagian Islands remain sought-after tourist destinations for discerning travellers enticed by the appeal of the islands’ ‘remote’ location, crystal clear waters and unspoiled beaches (O’Healy, 2016). 2011 and 2012 were the only years in which the arrival of migrants influenced tourist arrivals (Di Matteo, 2016; Surico, 2020). Together with responses from tourists and interviewees, this suggests that migration per se had little impact on tourism flows to the island. In fact, while the media presents the island to tourists as a migration hotspot, once on the island tourists experience something different. Tourists who returned from Lampedusa even claimed to have encouraged friends to pay a visit to the island.

While migration has split the local community in terms of the impact on its image, some stakeholders, such as NGOs and policymakers, believe it has also portrayed Lampedusa as an exemplar of solidarity. This has raised the island’s profile through media mentions, visits by public figures and production of films/documentaries featuring the island, and it has indirectly encouraged people to visit the island. Furthermore, combined with those people who visit the island for work related to migration, this has created a new tourism niche that, unlike 3S tourism, provides operators with income during the off season. The succession of migration crises has nevertheless shifted attention and resources to its cause, at times giving locals the impression that authorities have been more interested in migration than in local issues. Resources have also been stretched, impacting local enforcement issues. Migration has become an easy target to blame for various island issues.

The main problem for the destination’s image seems to be the constant reference to Lampedusa in association with the migration crisis in the press and the lack of adequate promotional efforts by the private sector, which focuses on 3S tourism. While tourists who visited the island for an organised ecotour got immersed in the natural environment, confirming that the island can offer much more than 3S and is ideal for practising ecotourism, this aspect is mostly unknown to and undervalued by local stakeholders. The fact that the island is synonymous with 3S tourism among domestic tourists and is labelled as a migration hotspot in the media might explain why its natural resources, including the terrestrial and marine protected areas, which are home to great biodiversity, have remained hidden. Notwithstanding all this, authorities have done little to counter the island’s associations with migration and 3S tourism. Promotional efforts are limited and mostly target domestic markets for 3S. Furthermore, connectivity is limited, and low-cost airlines are available only in the summer period. Lampedusa has also failed to capitalise on the sister island of the archipelago, which can enrich its image and make the product more competitive.

Bearing in mind Lampedusa's size, number of inhabitants, the negative environmental impact of mass tourism and the rich terrestrial and marine natural resources, several stakeholders interviewed believe that the way forward is to move away from existing tourism models based on 3S. Sustainable tourism, including ecotourism, is being proposed as it can be practiced year round and is not concentrated in the summer season. Through ecotourism, Lampedusa can transform its protected areas into a truly sustainable tourism resource that benefits local communities, further supporting their management and protection. The island’s historical and archaeological heritage can further support this type of tourism due to its overlap with ecotourism and the interest of ecotourists in such aspects. Ecotourism can also help offer local communities alternative income opportunities, reducing youth emigration. However, this calls not only for a change in direction in terms of marketing efforts but also for an upskilling and reskilling of operators, including in the field of interpretation and ecotourism; supporting operators, such as those working in the transport sector, to embrace sustainability; and ensuring better connectivity by air all year round from international destinations. This can help the island not only to steer away from being known as the island of migration but also to refrain from projecting itself as a 3S destination. By using its natural resources and the brand of the archipelago, Lampedusa can portray an image which is more representative of the island and attract a form of sustainable tourism towards its shores.

Acknowledgements

I thank Prof. Godfrey Baldacchino for comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

References

- Agius, K., Theuma, N., Deidun, A., 2021. So close yet so far: Island connectivity and ecotourism development in central Mediterranean islands. Case Stud. Transp. Policy. 9(1): 149–160.

- Agius, K., Sindico, F., Sajeva, G., Baldacchino, G., 2021. 'Splendid Isolation': embracing islandness in a global pandemic. Island Stud. J. https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.163.

- Alipour, H., Olya, H.G., Maleki, P., Dalir, S., 2020. Behavioural responses of 3S tourism visitors: Evidence from a Mediterranean Island destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 33, 100624.

- Almeida, A.M.M., Machado, L.P., 2019. Madeira Island: Tourism, Natural Disasters and Destination Image. In: Sequeira, T., Reis, L. (Eds.), Climate Change and Global Development. Contributions to Economics. Springer, Cham, pp. 285–301.

- ANSA, 2020. Monk seal, at risk of extinction, sighted off Lampedusa. Retrieved on November 8, 2020 from http://www.ansamed.info/ansamed/en/news/sections/environment/2020/11/02/monk-seal-at-risk-of-extinction-sighted-off-lampedusa_5e63a68d-8894-455d-918f-239ccd9421bc.html.

- Baldacchino, G., 2015. More than Island Tourism: Branding, Marketing and Logistics. In Baldacchino, G. (Ed.), Archipelago Tourism: Policies and Practices. Ashgate Publishing Ltd, Surrey, pp 1–18.

- Baldacchino, G., 2020. Extra-territorial quarantine in pandemic times.

Political Geogr. In Press. - Baldacchino, G., Ferreira, E.C.D., 2013. Competing notions of diversity in archipelago tourism: transport logistics, official rhetoric and inter-island rivalry in the Azores. Island Stud. J. 8(1): 84–104.

- Baloglu, S., McCleary, K.W., 1999. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 26(4): 868–897.

- Barbagallo, F., 2003. Le Riserve naturali siciliane gestate de Legambiente. Legambiente, Palermo.

- BBC., 2020. Lampedusa: Migrant with coronavirus gives birth in helicopter. Retrieved on October 21, 2020 from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53993465.

- Bernardie-Tahir, N., Schmoll, C., 2014. The uses of islands in the production of the southern European migration border. Island Stud. J. 9(1): 3–6.

- Buerkert, A., Luedeling, E., Dickhoefer, U., Lohrer, K., Mershen, B., Schaeper, W., Nagieb, M., Schlecht, E., 2010. Prospects of mountain ecotourism in Oman: the example of As Sawjarah on Al Jabal al Akhdar. J. Ecotourism. 9(2): 104–116.

- Cascio, P.L., Pasta, S., 2012. Lampione, a paradigmatic case of Mediterranean island bio-diversity. Biodivers. J. 3: 311–330.

- Cavallaro, F., 2017. Lampedusa, sconfitta Giusy Nicolini Il nuovo sindaco Martello: sull’accoglienza deve cambiare tutto. Retrieved on October 19, 2020 from https://www.corriere.it/amministrative-2017/elezioni-comunali/notizie/comunali-lampedusa-nicolini-sconfitta-1fedeeae-4f54-11e7-b3da-d63487cd15a9.shtml.

- Chamard, P., Ciattaglia, L., Di Sarra, A., Grigioni, P., Monteleone, F., Sarao, R., 1998. The ENEA Station for climate observations at Lampedusa. Roma-Italy: Conferenza Nazionale Energia e Ambiente, p.10.

- Chaulagain, S., Wiitala, J., Fu, X., 2019. The impact of country image and destination image on US tourists’ travel intention. J. Dest. Mark. Manage. 12: 1–11.

- Comune di Lampedusa e Linosa. (2015). Piano di Interventi per l’Isola di Lampedusa. Retrieved on October 20, 2020 from http://www.comune.lampedusaelinosa.ag.it/documenti/Lampedusa%20Piano%20Interventi%2020mln%20di%20euro.pdf.

- Cooke, G.B., Petersen, B.K., 2019. A typology of the employment-education-location challenges facing rural island youth. Island Stud. J. 14(1): 101–124.

- Cosenza, G., 2011. I contrasti delle Pelagie: fra turismo di mass, ambientalismo e migranti. In Lorusso, A.M., Violi, P. (Eds.), Efetto Med. Immagini discorsi, luoghi. Fausto Lupetti, Bologna, pp. 285–321.

- Cuttitta, P., 2014. Borderizing the island setting and narratives of the Lampedusa border play. Acme. 13(2): 196–219.

- d’Hauteserre, A.M., 2016. Ecotourism an option in small island destinations?. Tour. Hosp. Res. 16(1): 72–87.

- Di Matteo, G., 2016. Turismo e immigrazione. Lampedusa come laboratorio di sostenibilità sociale. Tesi di Laurea Magistrale, Universita Ca'Foscari Venezia.

- Di Matteo, G., 2019. Immigrazione e turismo in un contesto microinsulare. Sperimentazioni di responsabilita turistica a Lampedusa. In: Salvatori, F. (Ed.), L'apporto della Geografiia tra rivoluzioni e riforme. Atti del XXXII Congresso Geografico Italiano (Roma, 7–10 giugno 2017). A.Ge.I., Roma, pp. 2927–2933.

- Domina, G., Soldano, A., Scafidi, F., Danin, A., 2012. Su alcune piante nuove delle Isole Pelagie (Stretto di Sicilia). Quaderni di Botanica ambientale e applicate. 23: 41–44.

- Donovic, D., 2020. Rebranding Places affected by immigration crisis: The case of Lesvos Island in Greece. Unpublished Master Dissertation, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

- Dooley, L.M., 2002. Case study research and theory building. Adv Dev Hum Resour. 4(3): 335–354.

- ENAC., 2018. Traffic data 2017. Retrieved on October 13, 2020 from https://www.enac.gov.it/sites/default/files/allegati/2018-Ago/ENAC_Traffic_data_2017_en.pdf.

- EUR-Lex., 2015. Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2015/74 of 3 December 2014 adopting an eighth update of the list of sites of Community importance for the Mediterranean biogeographical region (notified under document C(2014) 9098) L18/696. Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved on October 21, 2020 from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32015D0074.

- Fattorini, S., Dapporto, L., 2014. Assessing small island prioritisation using species rarity: the tenebrionid beetles of Italy. J. Integr. Coast. Zone Manag. 14(2): 185–197.

- Feng, K., Page, S.J., 2000. An exploratory study of the tourism, migration-immigration nexus: Travel experiences of Chinese residents in New Zealand. Curr. Issues Tour. 3(3): 246–281.

- Ferlito, F., Gentile, A., La Malfa, S., Prinzivalli, L., Santangelo, T., Sparacio, A., Sparla, S., Sanchez Garcia, S., Cauchi, J., Attard, E., 2013. Winegrowing and winemaking in minor islands of the Mediterranean. Guidelines for Sustainable Vineyard Management. Project Operational Programme Italia-Malta 2007–2013. Promed, pp. 62–71.

- Ferrari, G., 2006. Grotte marine a Lampedusa. Thalassia Salentina. 29(suppl.): 117–138.

- Finn, M., Walton, M., Elliott-White, M., 2000. Tourism and leisure research methods: Data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Pearson education, Essex.

- García-Almeida, D.J., Hormiga, E., 2017. Immigration and the competitiveness of an island tourism destination: a knowledge-based reputation analysis of Lanzarote, Canary Islands. Island Stud. J. 12(1): 207–222.

- Giardina, F., 2012. Itinerari Sommersi nelle isole Pelagie: incontri tra natura, scienza e vita marina. Ministero dell’ Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare.

- ISTAT., 2017. Personal Communication.

- Ivanov, S., Stavrinoudis, T.A., 2018. Impacts of the refugee crisis on the hotel industry: Evidence from four Greek islands. Tour. Manag. 67: 214–223.

- Jauhiainen, J.S., 2017. Asylum Seekers and Irregular Migrants in Lampedusa, Italy, 2017. Department of Geography and Geology, University of Turku, Painosalama Oy, Turku. Retrieved on October 20, 2020 from http://urmi.fi/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Jussi-S.-Jauhiainen_-ASYLUM-SEEKERS-AND-IRREGULAR-MIGRANTS-IN-LAMPEDUSA-ITALY-2017.pdf.

- IOM, 2021. Key Migration Terms. Retrieved on February 6, 2021 from https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms.

- Khan, M.M., Su, K.D., 2003. Service quality expectations of travellers visiting Cheju Island in Korea. J. Ecotourism. 2(2): 114–125.

- Kirby, E.J., 2016. Why tourists are shunning a beautiful Italian islands. Retrieved on October 21, 2020 from https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35540017.

- La Manna, G., Manghi, M., Sara, G., 2014. Monitoring the habitat use of common Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) using passive acoustics in a Mediterranean marine protected area. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 15(2): 327–337.

- La Mantia, T., Carimi, F., Di Lorenzo, R., Pasta, S., 2011. The agricultural heritage of Lampedusa (Pelagie Archipelago, South Italy) and its key role for cultivar and wildlife conservation. Ital. J. Agron. 6(e17): 106–110.

- La Mantia, T., Veca, D.S.L.M., Marchetti, M., Barbera, G., 2013. Preliminary results on the reforestation techniques in the southern Sicily. Italian Journal of Forest and Mountain Environments. 57(3): 261–275.

- La Repubblica., 2016. “Quo vado?” dei record: il film con Zalone è l'italiano più visto di tutti i tempi. Retrieved on February 6, 2021 from https://www.repubblica.it/spettacoli/cinema/2016/01/13/news/_quo_vado_dei_record_il_film_con_checco_zalone_e_il_piu_visto_di_sempre-131173548/.

- Lampedusa Pelagie — Informazioni Turistiche, 2020. Lampedusa Voli Estate 2021. Retrieved on October 20, 2020 from http://www.lampedusapelagie.it/lampedusa-voli/.

- Longhi, G., Conti, F., Bellina, D., Steiner, A., Origoni, F., Freschi, A., Agostini, R., Veloci, V., Scarso, M., Guerra, F., Mander, S., Adami, A., Pilot, L., Fanello, G., Meggiato, S., Rizzi, F., 2006. Piano strategico per lo sviluppo sostenibile delle isole Pelagie. Progetto Pilota per le Isole Minori. Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, Dipartimento per le Politiche di Sviluppo e Coesione, Regione Siciliana, Comune di Lampedusa e Linosa, Università IUAV Venezia, Dipartimento di Urbanistica.

- Martin, I., 2016. Lampedusa travel ad raises eyebrows. No intention to comment insensitively — CEO. Retrieved on October 21, 2020 from https://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20160318/local/lampedusa-travel-ad-raises-eyebrows.606010.

- Melotti, M., 2018. The Mediterranean between Tourism and Migration. Lampedusa and the refugee crisis. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Tourism Dynamics and Trends, p. 40.

- Melotti, M., Ruspini, E., Marra, E., 2018. Migration, tourism and peace: Lampedusa as a social laboratory. Anatolia. 29(2): 215–224.

- Mirsanjari, M.M., Molla, M.A., Zarekare, A., Ghorbani, S., 2013. Environmental impact assessment of ecotourism site’s values. Adv. Environ. Biol. 7: 248–252.

- Neleman, S., de Castro, F., 2016. Between nature and the city: youth and ecotourism in an Amazonian ‘forest town’ on the Brazilian Atlantic Coast. J. Ecotourism, 15(3): 261–284.

- Nicolini, G., Dimarca, A., Casamento, G., Livreri Console, S., 2008. Piano di Gestione “Isole Pelagie”. Retrieved on October 21, 2020 from http://www.artasicilia.eu/old_site/web/pdg_definitivi/definitivi/pdg_isole_pelagie/1_relazioni/ispl_relazione_pdg_conoscitiva.pdf.

- O’Healy, Á., 2016. Imagining Lampedusa. In Ben-Ghiat, R., Hom, S.M. (Eds.), Italian Mobilities. Routledge, pp. 152–174.

- Orsini, G., 2015. Lampedusa: from a fishing island in the middle of the Mediterranean to a tourist destination in the middle of Europe’s external border. Ital Stud. 70(4): 521–536.

- Papale, E., Azzolin, M., Giacoma, C., 2012. Vessel traffic affects bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) behaviour in waters surrounding Lampedusa Island, south Italy. J. Mar. Biolog. 92(8): 1877–1885.

- Parker-Jenkins, M., 2018. Problematising ethnography and case study: reflections on using ethnographic techniques and researcher positioning. Ethnogr. Educ. 13(1): 18–33.

- Pasta, S., La Mantia, T., 2013. Species richness, biogeographic and conservation interest of the vascular flora of the satellite islands of Sicily: patterns, driving forces and threats. In Cardona Pons, E., Estaún Clarisó, I., Comas Casademont, M., Fraga i Arguimbau, P. (Eds.), Islands and plants: preservation and understanding of flora on Mediterranean islands. 2nd Botanical Conference in Menorca, Proceedings and abstracts, Institut Menorqui d’Estudis, Consell Insular de Menorca, Maó. Collecció Recerca. 20: 201–240.

- Pasta, S., La Mantia, T., Rühl, J., 2012. The impact of Pinus halepensis afforestation on Mediterranean spontaneous vegetation: do soil treatment and canopy cover matter?. J. For. Res. 23(4): 517.

- Peronaci, M., Luciani, R., 2015. Anthropic pressures on Egadi Islands. Energia Ambiente e Innovazione. 61(4): 9–11.

- Piovano, S., Nicolini, G., Nannarelli, S., Dominici, A., Lo Valvo, M., Di Marco, S., Giacoma, C., 2006. Analisi delle deposizioni di “Caretta caretta” sui litorali italiani. In Zuffi, M.A.L. (Ed.), Atti del V Congresso Nazionale (Calci (PI), 29 settembre–3 ottobre 2004. Societas herpetologica italica.

- Power, S., Di Domenico, M., Miller, G., 2017. The nature of ethical entrepreneurship in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 65: 36–48.

- Prazzi, E., Nicolini, G., Piovano, S., Giacoma, C., 2013. La spiaggia dei Conigli a Lampedusa: un modello di gestione per la conservazione di Caretta caretta. In Di Tizio, L., Brugnola, L., Cameli, A., Di Francesco, N. (Eds.), Atti Il Congresso SHI Abruzzo Molise “Testuggini e Tartarughe” (Chieti, 27–29 settembre 2013). Ianieri Edizoni, Pescara, pp. 127–133.

- Ravazza, N., Anselmo, S., 2010. Pelagie. Le isole dei paladini. Anselmo Editore, Trapani.

- Rigas, K., 2012. Connecting island regions: A qualitative approach to the European experience. SPOUDAI. 62(3/4): 30–53.

- Roatti, V., Massa, B., Dell'omo, G., 2019. Bill malformation in Scopoli's Shearwater Calonectris diomedea chicks. Mar. Ornithol. 47: 175–178.

- Salvatori, G., 2015. Stone or Sound. Memory and Monuments in Contemporary Public Art. Il Capitale Culturale. Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage. 12: 931–954.

- SISPlan/IGEAM., 2012. Piano di Mobilità Sostenibile interna alle isola: Minori Occidentali. Lampedusa. Screening alla valutazione di incidenza ambientale — Nota tecninca — Lampedusa.

- Sposimo, P. (2014). Progetto per l’eradicazione del ratto nero Rattus rattus nell’Isola di Linosa (Isole Pelagie) e per le azioni di controllo in alcune aree dell’Isola di Lampedusa. Progetto LIFE11 NAT/IT/000093 “Pelagic Birds — Conservation of the main European population of Calonectris diomedea and other pelagic birds on Pelagic Islands. Retrieved on October 21, 2020 from http://www.pelagicbirds.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Eradicazione-dei-Ratti-a-Linosa.pdf.

- Stoffelen, A., 2019. Disentangling the tourism sector’s fragmentation: a hands-on coding/post-coding guide for interview and policy document analysis in tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 22(18): 2197–2210.

- Surico, G., 2020. Lampedusa: dall’agricoltura, alla pesca, al turismo. Firenze University Press, Firenze.

- Suryani, A., 2013. Comparing case study and ethnography as qualitative research approaches. Jurnal Ilmu Komunikasi. 5(1): 117–127.

- Tantaruna, L., 2016. What is a migration crisis and how to address it integrally? Retrieved on February 6, 2021 from https://rosanjose.iom.int/site/en/blog/what-migration-crisis-and-how-address-it-integrally.

- TripAdvisor., 2020. Top 25 Beaches — World. Retrieved on October 18, 2020 from https://www.tripadvisor.com/TravelersChoice-Beaches-cTop-g1.

- Tsartas, P., Kyriakaki, A., Stavrinoudis, T., Despotaki, G., Doumi, M., Sarantakou, E., Tsilimpokos, K., 2020. Refugees and tourism: a case study from the islands of Chios and Lesvos, Greece. Curr. Issues Tour. 23(11): 1311–1327.

- van ‘t Klooster, N.B., 2012. Tourism and Migration “We’re more than just hosts”. Unpublished M.Sc. Thesis Research Master’s programme CASTOR (Cultural Anthropology: Sociocultural Transformations), Utrecht University, The Netherlands.

- Veal, A.J., 2006. Research methods for leisure and tourism: A practical guide. Pearson Education, Essex.

- Vietti, F., 2019. Turisti a Lampedusa. Note sul nesso tra mobilità e patrimonio nel Mediterraneo. Archivio antropologico mediterraneo, Anno XXII, n. 21 (1). Retrieved on October 19, 2020 from http://journals.openedition.org/aam/1252.

- Wearing, S., Cynn, S., Ponting, J., McDonald, M., 2002. Converting environmental concern into ecotourism purchases: A qualitative evaluation of international backpackers in Australia. J. Ecotourism. 1(2–3): 133–148.