Analysis of the Conditions and Characteristics of Japanese Migrant Fishing Villages in Ulsan

Abstract

This study aimed to explore how Japan expanded its fishery bases in Joseon and colonized and ruled the coastal and offshore areas of Joseon and its fishery industry by analyzing the conditions and characteristics of Japanese migrant fishing villages in Ulsan. This study also examined how the private exchange between Joseon and Japanese people was formed during the colonial era.

There were free-migration fishing villages, such as Sinam, Sejukpo, Ilsanjin, and Jeongja, where Japanese fishermen migrated and settled to make a living and earn personal incomes by catching fish, such as sardines, sole, and cero. In the case of Jeonhari, it was initially an aid-migration fishing village, which was formed as the Shimane Prefecture government offered aid grants to have fishermen migrate and later more Japanese fishermen migrated by their free will. Bangeojin was a migrant fishing village formed based on the combination of free migration and aid migration. The establishment of those migrant fishing villages was managed as part of Japan’s colonial policies as the Japanese government intended to colonize Joseon. The Japanese government aimed to obtain the fishery resources of Joseon, and there was also a strategic intention to have Japanese people migrate to geographically important spots in the Korean peninsula and have a militarily competitive edge.

It was also found that the fish caught in migrant fishing villages were carried to Japan to be used for military food procurement in times of war, as seen in Sinam, Sejukpo, and Bangeojin. The early process of the colonization of Joseon was confirmed through the Association of Japanese People formed in Bangeojin, which gave Japanese people the privilege to engage in commerce in Joseon and supported Japanese settlers, groups, and organizations that aided in the colonization of Joseon. Lastly, this study analyzed how private exchange between Joseon and Japanese people was formed during the colonial era. There were conflicts between Joseon and Japanese people at red-light districts, public baths, and schools. Conversely, the records about the Joseon person hired by a Japanese store owner and a Joseon person who gave considerations to Japanese people showed personal trust and friendly attitude between civilians beyond the relationship between colonizers and the colonized at a governmental level.

Keywords

Migrant fishing village in Ulsan, intrusion, marine products, fishery, colony, Private Exchange

Introduction

The Japanese government began to form Japanese migrant fishing villages after the Russo-Japanese War. Free-migration fishing villages were formed as Japanese fishermen freely migrated to Korea to earn personal incomes and decided to settle while performing fishing activities. On the other hand, aid-migration fishing villages were formed as prefectural governments organized associations and these associations recruited fishermen, as well as farmers, industrialists, and jobless people, and provided them with aid grants with a plan to colonize Joseon. In 1911, there were about 26 aid-migration fishing villages, which accounted for about 46 percent of all migrant fishing villages. The number of aid-migration fishing villages decreased to 10 in 1921, and in areas where they disappeared, free-migration fishing villages appeared. Be it in a free-migration fishing village or an aid-migration fishing village, Japanese migrants were the main agents who put into action Japanese colonial fishery policies and colonialization. This is in line with Takasaki Soji’s1 remark that Japan’s invasion of Joseon was maintained and supported by the “grassroots invasion” and “grassroots colonial rule” by the common people and that the migration of many common people from Japan to Joseon became the foundation of Japan’s ruling the colony.

In Ulsan Bay, Japanese fishery businesses, such as diving apparatus, shark/cero, and eel fishery businesses, dominated and colonized Korean fisheries by using carriers that were in line with the characteristics of each fishery business and using much more advanced techniques than those of Joseon. The Korea-Japan Fishery Agreement of 1908 allowed Japanese fishermen to perform fishing activities with equal status as Korean fishermen in the coastal and inland waters of Korea, enabling Japan to obtain Korean fisheries. The Japanese government dispatched Japanese fishermen to move to migrant fishing villages in Ulsan and other coastal areas in earnest in a bid to solve the problem of the excess fishery population in Japan and tried to dispose of the fish caught in the Korean fisheries due to its perishability. As the Russo-Japanese War was progressing, there was a very high demand for fish for military procurements in Ulsan Bay. Ulsan Bay also served as a base of powered carriers to reach Japanese customers in a short time. Migrant fishing villages in Ulsan attracted many Joseon fishermen nearby and the fish caught in Ulsan Bay was sold to Busan Marine Product Store, causing fish markets for Joseon fishermen to shrink. Bangeojin was the early base of Hayashikane (林兼) Store, which became a fishery conglomerate by catching fish in the waters of Joseon. This was the process in which Japanese people carried out colonial policies.

Consequently, a number of studies were performed on the process in which Joseon’s fishery resources were plundered by Japanese fishery businesses, which intruded into the waters of Joseon. Yoshida Keiichi (吉田敬市, 1954) described general matters ranging from the background of the establishment of migrant fishing villages to the properties, construction, and the characteristics of different types of such villages. Based on this basic analysis, a number of studies on the conditions and characteristics of each migrant fishing village were conducted in Korea and other countries. While the analysis of all those previous studies cannot be presented here due to limited space, this study offers a few examples. Yeo Bak-dong (1994) examined the process in which Okayamamura (岡山村) and Irisamura (入佐村), both typical aid-migration fishing villages, were formed and described the colonial rule in the fishery field by exploring the relationship between Japanese fishermen’s fishing activities and Korean fishermen. Kim Seung (2010) attempted a new categorization of Japanese migrant fishing villages by examining the conditions and economic activities of migrant fishing villages in Busan. Kim Su-hee conducted a study on the effects of the fishery base construction plan for Japanese fishermen on the collective migration of Japanese people (2005a); and another study on the trend of Japanese migrant fishermen and fishery capitalists in relation to mackerel (2005b).

Lastly, Lee Hyun-ho (2008), Park Jeong-seok (2012), and Lee Jeong-hak (2016) conducted studies on Bangeojin. They analyzed the process in which a migrant fishing village was formed in Bangeojin and the structure of the society; examined what Japanese people who lived in Bangeojin remembered about the village; and explained the life of the times through the modern culture and entertainment facilities in Bangeojin.

As seen above, there were a number of studies conducted on the process in which Japanese migrant fishing villages were built on major fishery bases across the country in Korea as Japanese people plundered fishery resources and dominated fishing rights during the colonial rule. Although there were a few studies conducted on Bangeojin, one of the migrant fishing villages in Ulsan, it is difficult to find studies that were conducted on all the migrant fishing villages built in Ulsan from a macroscopic perspective. In addition, most studies on migrant fishing villages pertained to the conditions of migrant fishing villages and migrant fishermen’s fishing activities, while a few studies were conducted on the exchange between Japanese and Joseon people in those villages. Therefore, this study is intended to analyze the conditions and characteristics of migrant fishing villages and the formation of the private exchange between Japanese and Joseon people as the fishing villages were colonized.

Conditions and Characteristics of Japanese Migrant Fishing Villages

Major migrant fishing villages in Ulsan include Sinam (新岩), Sejukpo (細竹浦), Ilsanjin (日山津), Jeonhari (田下里), Jeongja (亭子), and Bangeojin (方魚津). As it is difficult to find historical records on those migrant fishing villages, except for Bangeojin, this chapter intends to analyze the process in which Japan expanded its fishery bases in Joseon and colonized and imperialized them mainly by reviewing historical records, such as Fishery Product Office of the Department of Agriculture, Trade and Industry (農商工部水産局編纂, 1910) and Gyeongsangnam-do (慶尚南道編, 1921), regarding the background of the formation of Japanese migrant fishing villages2, their compositional characteristics, and the local economic activities.

Background of the Establishment of Japanese Migrant Fishing Villages

Sinam was a free-migration fishing village, which was established in 1908 by Moriya Risuke (守谷利助) who was from Mie Prefecture (三重県). Moriya and Ito Shonosuke (伊藤庄之助) visited Joseon together to estimate potential profits in May 1907. Originally from coastal Wakamatsu (若松), Moriya encouraged migration to Joseon and ran only fishery businesses3. Moriya and Ito’s sardine business was successful and they ran dozens of seine-net fish farms. In August 2913, they installed octagonal nets, the first in the Korean peninsula, and operated five fish farms installed with octagonal nets. All fishermen needed for the operation of the fish farms were from Ito’s hometown, Mie Prefecture. Moriya and Ito also purchased paddy fields and farms near their fish farms and taught the Japanese people to grow crops and vegetables for self-sustenance. They also had migrant fishermen perform farming activities on the sideline4. In 1914, they built a soybean paste and soy sauce brewery for their fishery business and had vessel and construction carpenters and stonemasons migrate to Sinam. They built houses, fishing vessels, and gear and crafted utensils for the villagers’ daily use. In December 1915, a school cooperative was formed to educate children of the migrants, and in December 1920, a post office and a police substation were opened to help lay the foundation of the migrant fishing village5.

Sejukpo was also a free-migration fishing village. Around 1899, sole-fishing hand-operated trawl boats from Awaji, Hyogo Prefecture, began to operate with its base in this area. In the same year, brothers Hatakeda and Yutaro (畠田友太郎) migrated to Sejukpo and operated a diving apparatus fishery business and a general store. In the same year, Ookubo Kaichi (大久保鹿一) migrated to Sejukpo to run the general store of Hatakeda. Nakayama Utaro (中山卵太郎) migrated to the village to operate a diving apparatus fishery business in 1910, and Itatani Bo (板谷某), who ran a diving apparatus fishery business, moved to Sejukpo, Ulsan from Busan in 1911. As many as 40 to 50 hand-operated trawl boats from Hyogo Prefecture were engaged in migratory fishery annually, and in 1912, the office of a fishing boat group (出漁團) opened in Sejukpo6.

Ilsanjin was also a free-migration fishing village and it had long been a suitable refuge harbor7. Migratory fishery began in Ilsanjin in 1908 when four fishery businessmen including Shibata Tokumatsu (柴田徳松) came to Ilsanjin and launched a sardine fishery business. In 1909, Inagaki Kojo (稲垣貢蔵) and Higuchi Heijo (樋口平蔵) also migrated to Ilsanjin to run a sardine fishery business. In 1910, the three other fishery businessmen, except Shibata, failed as they had no experience in sardine fishery and moved to Bangeojin. Afterward, Shibata continued to operate fishery businesses and made large profits, ultimately settling in Ilsanjin8.

A typical fishing village, Jeonhari was originally named Jeonhapo (田下浦) in 1672 and was given the current name at the time of an administrative district reform in 19149. Jeonhari was a migrant fishing village formed based on the combination of free migration and aid migration. In 1906, two groups of migrants called Oura Group (大浦組) and Mino Group (美濃組) (about 30 persons in each group) were organized in Shimane Prefecture and migrated to Jeonhari with each group receiving a 600-yen grant from Shimane Prefecture government. Each group ran a communal sardine seine-net fishery business and made large catches. In 1908, they faced a low catch period (大不漁) and were suddenly short of funds. Most returned to their hometowns in Japan. Among the remaining fishery cooperative members, Ishibashi Shinjiro (石橋新二朗) from Oura Group and Derada Reitaro (寺田禮太郎) from Mino Group managed to take over the fishery businesses in the area. They made good catches of fish each year and found the fishery locale to be promising. They decided to settle in Jeonhari and brought their families with them in 1912. It was found that they were living in the village in 192110. Meanwhile, an increasing number of Japanese fishermen migrated to Jeonhari by their free will. In 1921, there were 15 households of Japanese migrants who totaled 45 persons, and all were from Shimane Prefecture.

Jeongja was a free-migration fishing village. Migratory fishery began in Jeongja in 1907 as Wada Kyushichi (和田久七) and another Japanese man migrated there to run the sardine seine-net fishery business. However, they did not make good catches and the Japanese man who migrated with Wada resigned. As Wada continued operating his fishery business, sardine fishery thrived in 1913 and the coastal waters of Jeongja became a major sardine fishing ground. As Jeongja became a temporary anchorage for mackerel net boats during this period, Japanese people came to the area for commercial purposes around 1915. Ueda Kametaro (上田龜太郎) and Poseong Trading House established an abalone canning factory in 1919. By 1921, about 12 households of Japanese migrants had settled in Jeongja11.

Bangeojin was a migrant fishing village formed based on the combination of free migration and aid migration. As the Dong-myeon Office was relocated to Bangeojin in 1925, the area became the center of Dong-myeon12. In 1897, a total of 39 fishermen, including Morimoto Sane (森本實), a fishery business owner from Wakihinase, Okayama (岡山) Prefecture, began sailing to the coastal waters of this area to catch cero. They entered into a contract with Dakada Toragoro (高田寅五郎) to procure supplies from Japan, and Dakada migrated to the fishing village, as well. In 1905, Ariyoshi Kamekichi (有吉亀吉) learned that the coastal waters of Bangeojin was a promising cero fishery locale and migrated with 2-3 persons from Hinasekura, Okayama Prefecture, receiving a 200-yen grant from the prefecture13. After Goda Eikichi (合田榮吉) launched mackerel fishery in Bangeojin, the area became the largest base of mackerel fishery14. In 1909, 100 fishing boats sailed to Bangeojin from Okayama Prefecture, and in the same year, an association of Japanese civilians was organized and an elementary school was established in Bangeojin. In 1910, a test demonstration of mackerel net fishing was successfully operated by the Fisheries Experiment Station, Kagawa (香川) Prefecture. Subsequently, a number of mackerel fishing boats sailed to Bangeojin15. In the same year, a branch office of the Joseon Fishery Cooperative and an office of the fishing boat group of Okayama Prefecture were established there.

An aid-migration fishing village appeared in Bangeojin as the Chikuho (筑豊) Fishery Cooperative of Fukuoka (福岡) Prefecture built 30 houses in the area16. The Fukui Prefecture government built eight houses for migrants and had Japanese fishermen migrate, offering a 100-yen grant for each household. Fishermen from Fukui Prefecture operated three fishing boats with cero drift nets and one fishing boat for diving apparatus fishery. As an increasing number of Japanese fishermen migrated to Bangeojin by their free will, Bangeojin grew to be a large migrant fishing village with a total of 411 households as of 191917. For 20 years beginning from 1915, mackerel businesses rapidly increased and more people migrated to Bangeojin for commercial purposes. In this way, the number of Japanese migrants increased each year in Bangeojin and there were as many as 495 Japanese households in 1921. In the 1930s, modern public institutions were established, Bangeojin Port and a seawall were constructed, Nakabe Ikujiro (中部幾次郎) operated Hayashikane (林兼) Store, and modern cultural and entertainment facilities were built in Bangeojin, making it an important administrative district in the coastal area of Gyeongsangnam-do.

This section presented the background of the establishment of Japanese migrant fishing villages in Ulsan. There were free-migration fishing villages, such as Sinam, Sejukpo, Ilsanjin, and Jeongja, where Japanese fishermen migrated and settled to make a living and earn personal incomes by catching fish, such as sardines, sole, and cero. In contrast, Jeonhari was initially an aid-migration fishing village that was formed as the Shimane Prefecture government offered fishermen grants to migrate to the region. More Japanese fishermen would later migrate to Jeonjari by their free will. In the case of Bangeojin, it was a migrant fishing village formed based on the combination of free migration and aid migration. The establishment of those migrant fishing villages was managed as part of Japan’s colonial policies as the Japanese government intended to colonize Joseon. This shows that the migration of Japanese fishermen was not simply an act of migration but that of colonization. In this respect, Japan needed to build migrant fishing villages which could function as military advance bases in the Korean peninsula in order to implement policies for continental invasion.

Compositional Structures of Migrant Fishing Villages and Their Economic Activities

This section analyzes the regional composition of Japanese migrants residing in migrant fishing villages in Ulsan, their occupational characteristics, and economic activities.

1) Sinam

In 1921, there were a total of 34 migrant households with a population of 220 in Sinam. A population data analysis shows the number of households in relation to the prefecture from which they came, their occupations, as well as the population by gender.18 There were 30 households with 109 males and 96 females from Fukuoka Prefecture, which accounted for the largest group in Sinam. The migrant population from the Fukuoka Prefecture was followed by Mie and Oita (⼤分) Prefectures with two households each, and Fukushima (福島) Prefecture with one household. With regard to occupations, there were 119 fishermen (54%), all from Fukuoka; 47 construction carpenters; 19 shipwrights; and 9 persons engaged in fishery and the operation of general stores. It can be assumed that many construction carpenters migrated to build houses necessary for incoming migrants and shipwrights migrated to build ships necessary for migrants’ fishing activities. In fact, there were eight policemen dispatched from Japan, which is uncommon in other areas. The reason could be that Ulsan was located in a geographically important area to guard the coastal region in the southern East Sea.19

As for economic activities,20 seine-nets were used to catch sardines and cero, and octagonal nets were used to catch croakers and cutlassfish. The employment ratio of Joseon fishermen were higher than that of the Japanese fishermen, and all employed fishermen were provided with free meals. Japanese fishermen were paid more than Joseon fishermen. However, there was a system of giving rewards to Joseon fishermen who were particularly diligent, which was an uncommon system in other migrant fishing villages. Of the caught fish, cero, croakers, and cutlassfish were transported fresh using carriers owned by the businesses to Busan and Japan for sale. Moriya (守谷), a fishery business owner, had fishermen and 20 households cultivate a field of about 990 m2 per household on the sideline on the average. Additionally, he used a field of 112,400 m2 for tenant farming and the tenants were Joseon farmers from 45 households. He collected about 43,200 kg of jujubes (estimated price: 3,600 yen) and about 61,920 kg of rice (estimated price: 12,900 yen) and invested the profits in his fishery business.

From April to September each year, female divers came from Jeju Island in 12 ships to collect oysters, seaweed, etc. According to records, it describes that Joseon and Japanese people always had a good relationship.21 However, in reality, there were conflicts and disputes between them.22 It is assumed that Joseon people would have tried to gotten along with Japanese people to make money as they were hired as fishermen by Japanese business owners.

2) Sejukpo

In 1910, there were 10 households of 69 Japanese migrants in Sejukpo. Although they were engaged in fishery, some of them operated restaurants, general stores, or other stores serving fishermen.23 In 1921, there was a population of 35 migrants from seven households, all from Hyogo Prefecture.

With regard to occupational composition, there were 21 fishery businessmen which accounted for the largest unlike Sinam. Migratory fishing boats came to Sejukpo from August to November each year, and the waters of the village were quite busy with migratory fishing boats. There were nine shipwrights, who constituted the second-largest occupational group in the village, along with three fishermen and two engaged in commerce.

As for economic activities, in 1910, sole and taguri net (pulling the string alternately with both hands) fishing was active. The fish caught were usually sold in Joseon, but sole were transported to Japan. It took 10-14 days for the sole to arrive at Hyogo Prefecture.24 In 1921, abalone and sea cucumbers were caught using diving devices and sole and turbot were caught using small sailing trawl nets (打瀬網).

With regard to the fishermen,25 there were no Japanese and 28 Joseon persons in diving apparatus fish farms, and one Japanese and seven Joseon persons in small sailing trawl net fish farms. Same as in Sinam, more Joseon fishermen were hired than Japanese fishermen. This was probably because it was difficult to have hired Japanese fishermen move to Sejukpo each time. There was a village of Joseon people called Hwangseong-ri near Sejukpo, and many of the residents were hired as fishermen by Japanese migrants. According to records, the residents were in a good relationship with the Japanese migrants, but the records do not describe how the Joseon and Japanese people got along together. It remains difficult to analyze their relationship because related data are insufficient. The branch office of the Joseon Waters Fishery Cooperative was located in Sejukpo. In connection with the cooperative, the Japan-Korea Whaling (日韓捕鯨) company owned some land in Sejukpo.26 As sole caught in the region were carried to Osaka or Kobe, Japan and dried sea cucumbers were sold to merchants in Busan, it can be seen that the fish caught by Japanese migrants were freely traded at fish markets in Busan, taking up the distribution in fish markets of Joseon. Particularly, the office of Joseon Waters Fishery Cooperative in Sejukpo encouraged Japanese fishermen to migrate to Joseon and aided in their settlement.

3) Ilsanjin

In 1910, there were 22 Japanese migrants of two households in Ilsanjin. As the area was a good fishing ground for sardine seine-net fishery, Japanese migrant fishermen from prefectures along the western coast of Japan, such as Shimane, Fukuoka, and Mie Prefectures, performed fishing activities.27 In 1921, there was a population of 31 migrants from nine households and the majority (24 migrants, 77%) was from Mie Prefecture. With regard to occupational composition, the migrants had only two occupations—fishery businessmen and fishermen.

As for economic activities,28 there were only Japanese fishery businessmen and all were engaged in sardine seine-net fish farms. There were seven Japanese migrant fishermen, and 39 Joseon fishermen were hired in and around Ilsan-ri. Japanese fishermen were paid 50-60 won a month per person and the meals were not included. Joseon fishermen were paid 12-16 won a month per person, and business owners paid for their meals. This shows that there was a large wage gap between Joseon and Japanese people particularly in Ilsanjin. The fish caught were steamed and dried by the business owners, and the steamed and dried small anchovies and dried sardines were sold to the Busan Marine Product Store. Beginning in 1935, a lot of sardines were caught in Bangeojin. During the war, the fishery businesses were obliged to supply shark liver oil. About 30 Joseon people including ladies were hired to squeeze the oil and the oil cake factory was operated in Ilsanjin.29

According to the records, it states that Joseon and Japanese people got along in Ilsanjin, same as in other migrant fishing villages. However, according to a news article,30 there was a conflict between Joseon and Japanese people, many of them were injured and dozens of Joseon fishermen were arrested by the police.

4) Jeonhari

The Japanese fishermen who migrated from Shimane Prefecture with aid grants in 1906 faced a low catch period (大不漁) in 1908 and returned to their hometowns in Japan. Afterwards, an increasing number of Japanese fishermen migrated to Jeonhari by their free will. In 1921, there were 45 Japanese migrants of 15 households in Jeonhari, all from Shimane Prefecture. With regard to occupational composition, there were eight fishery businessmen and 17 fishermen, and 20 migrants from seven households—11 males and nine females—were engaged in running general stores and they comprised the largest group with the exception of fishery businessmen and fishermen.

As for economic activities,31 fishermen worked full-time in sardine seine-net fishery. Japanese fishermen were hired from among migrants and their monthly wages were 60 won. Joseon fishermen were hired from among those living in Jeonhari. Joseon fishermen were paid 20 won per person every month in advance and their monthly wages were 14 won with free meals included. In addition, they were paid additional incentives—14 won per person for a good catch. The fish caught were cooked or dried by the business owners and sold to the Busan Marine Industry or other stores in Busan, and there were no sideline jobs.

5) Jeongja

In 1921, there were 51 Japanese migrants of 12 households in Jeongja, and 15 of the migrants were from Yamaguchi Prefecture, accounting for the largest proportion. They were mainly from Mie, Hiroshima, and Kagawa Prefectures. With regard to occupational composition, fishery businessmen occupied the largest percentage—41% (21 persons), 13 persons were engaged in restaurants, 11 in commerce, five in seafood processing, and there was one shipwright.

Similar to nearby Bangeojin, there would have been a number of restaurants for migrant fishermen as well as stores selling ship fittings, fishing gear, and daily necessities, all of which were essential goods.

As for economic activities,32 sardine seine-net fishery was conducted by the family members of fishery businessmen who lived in Jeongja, and Joseon employees were hired from among those living in Jeongja-ri or neighboring villages. They were paid average monthly wages of 10 won with free meals included. Diving fishery without gear (裸潜) was conducted by female divers and all of the 13 female divers were Japanese. Japanese fishermen and female divers were hired from Yamaguchi Prefecture with round-trip travel expenses provided. An employee was paid 14-15 won a month, and a person was paid an additional 25 jeon for 1 gwan gram of abalone. Sardines among the catch were steamed or dried for processing by the business owners and then sold to the Busan Marine Industry or other stores in Busan. Abalone and top shells were sold to Japanese migrant manufacturers. The characteristics of the fishery manufacturing industry were analyzed as follows. Canned abalones were carried to the export port Jina (支那) and top shells and mackerel were carried to Japan to process them into canned food. In addition, 1,500 boxes of canned abalones, top shells, and mackerel were worth 30,000 yen, and the canned products were sold on consignment basis to wholesalers of the Busan Marine Industry. As with other migrant fishing villages such as Ilsanjin and Jeonhari, Japanese fishery businessmen in Jeongja discriminated against Korean fishermen in favor of Japanese fishermen and the wages of the latter were higher than those of Joseon fishermen. It can be said that the Japanese people also weakened fish markets for Joseon fishermen as they sold the catch to the Busan Marine Industry.

6) Bangeojin

In 1910, 47 Japanese migrants of 14 households had already settled in Bangeojin. Ten out of the 14 households were from an migrant group related to the management of Chikuho Fishery Cooperative, Fukuoka Prefecture, and they migrated with the aid from the prefecture government. As they settled in Bangeojin, some ran general stores, brewing facilities, barbershops, restaurants, and inns rather than engaging in fishery. When the Japanese people temporarily staying in Bangeojin were added, there were 60 households, which included about 260 males and 340 females. Of the 340 females, 260 had jobs related to prostitution.33 In 1916, there was a brothel in Bangeojin and more than one fifths of the female population residing in Bangeojin, which was 1507, belonged to the brothel and were engaged in prostitution.34 Of the total of 496 households in 1921, the population was 3,073. Bangeojin was the migrant fishing village with the largest population in Ulsan. The compositional characteristics of the migrants can be analyzed as follows.35

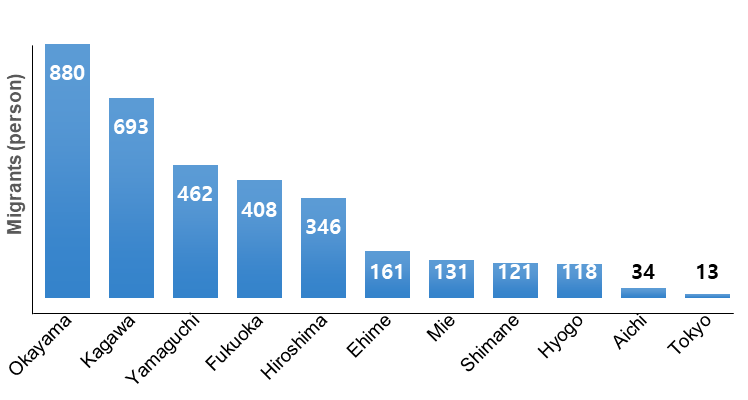

In Bangeojin, there were 145 households of 880 migrants from Okayama Prefecture, which accounted for the largest group. Okayama Prefecture was followed by Kagawa Prefecture with 117 households of 693 migrants. The migrants were mostly from the western coast of Japan, such as Yamaguchi, Hiroshima, and Ehime Prefectures. With regard to occupations, fishery businessmen accounted for 28% and fishermen 21%. Occupations related to fishery took up the largest portion, followed by 446 migrants engaged in commerce and 460 in prostitution. Some migrants also engaged in the billiards business (玉突業), which was rare. This shows that migrants with entertainment businesses flourished in Bangeojin. Those engaged in commerce36 accounted for 15%, which was high compared to other migrant fishing villages. It is assumed that more Japanese people migrated to Bangeojin for commercial purposes, beginning around 1915 after the local mackerel fishery was known to be promising. In the late 1910s when Bangeojin rapidly grew due to the high catch of mackerel, Hayashikane (林兼) entered into a fish purchase contract with the local Japanese fishermen and proprietarily collected their catch, laying the foundation of its growth.37 Around 1918, so many mackerels were caught and some of them were left to go rot due to the shortage of salt. Bangeojin became an outpost of mackerel fishery and even attracted Russian ships and sailors.38

As for economic activities,39 both migratory fishermen and migrants were engaged in mackerel and cero fishery and the total annual catch amounted to about 2 million yen, which was a huge amount of money. The number of Japanese fishermen (1,456) were much higher than Joseon fishermen (490). This is because many Japanese people learned that cero drift nets and mackerel nets were known in Bangeojin and they migrated to Bangeojin. In addition, Hayashikane Store enabled Japanese fishermen to easily migrate to Bangeojin through prepayment contract method. Japanese fishermen were usually hired in the hometowns of fishery businessmen directly by the businessmen or through captains. Joseon fishermen were hired in Ulsan-gun through negotiations with restaurant owners who were Joseon people. With regard to the treatment of the catch and sale methods, cero, mackerel, and horse mackerel were mostly sold fresh to fish carrier owners. They filled the fish carriers with ice and had fishermen transport them on cold storage freight carriers to Kobe, Osaka, Kyoto, Nagoya, and Tokyo. The fish were also supplied to major cities along railroads and major port cities, such as Busan and Moji (門司). In short, Japan colonized Joseon fisheries at Bangeojin by establishing a network based on the fishery invasion actions of Japanese people who migrated by their free will or migrated receiving aid grants, the securing of fishery capital using powered carriers, and the securing of fish through prepayment contract of Hayashikane.

As described above, in this chapter, based on the analysis of the migrant fishing villages in Ulsan, the background of the formation of the migrant fishing villages and the fishing conditions during the colonial period were identified. As the migrant fishing villages built by Japanese people grew and became the central places of communities, the formation of the migrant fishing villages was a part of the colonial policies to colonize Joseon. It was the Japanese government’s intention to have a militarily competitive edge in order to imperialize Joseon.

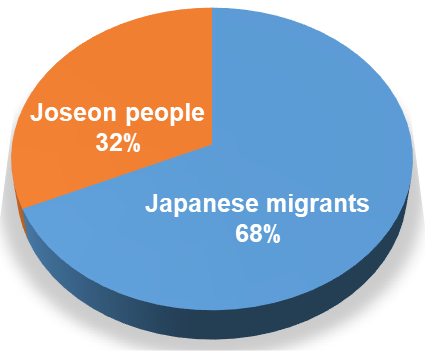

The following figures show the rates of Japanese migrants in the migrant fishing villages in Ulsan and the ratio of Japanese fishermen to Korean fishermen.

Although the Japanese government and Japan’s ministries and prefectures encouraged the migration of Japanese people to Joseon and built migrant fishing villages as a means to colonize Korea, Japanese and Joseon people would have mingled in a cultural space at migrant fishing villages while conflicts and exchanges of cooperation occurred. Chapter Ⅲ explores how private exchange was formed between the Japanese and Joseon people.

Private Exchange between Joseon and Japanese People in Migrant Fishing Villages

This study intended to analyze the type of exchange between the migrant fishing villages in Ulsan and the nearby villages of Joseon people. However, there was a restriction because Gyeongsangnam-do (慶尚南道編, 1921) and some news reports previously mentioned were all historical data that were available with the exception of Bangeojin. When Japanese fishery businessmen hired Korean fishermen living in nearby villages of Joseon people, there were comings and goings between the two villages. Japanese fishermen would have visited a village of Joseon people to hire fishermen. Or, they hired Joseon fishermen in Ulsan-gun by negotiating with restaurant owners who were Joseon people as guarantors. When a ship sailed to catch fish, Japanese and Joseon fishermen worked on the same ship and food was prepared in the ship to serve them meals. Therefore, private exchanges must have occurred. In Sinam and Bangeojin, there were schools, hospitals, and post offices for telegraphs and mail delivery, and Japanese migrants used convenience facilities in their villages. Japanese migrants living in Ilsanjin and Jeonhari went to Bangeojin to use public facilities. In Jeongja, all methods of transportation and communications were inconvenient and the residents depended on the collection and delivery services provided on alternate days by the post office in Ulsan. Japanese migrants living in Ulsan formed financial relationships with customers in Busan when handling finance and distribution funds. These examples show that Japanese migrants led their lives through exchange with Joseon people, such as fishing activities and the use of convenience facilities.

On a winter day in 1929 or 1939, Isono Yoshimatsu (磯野吉松) went mackerel net fishing. On the ship were his father and four Joseon people he had hired. At that time, the monthly wage of a Japanese fisherman was 1 yen and that of a Joseon fisherman was 50 jeon, which was half the wage of a Japanese fisherman. Joseon fishermen were discriminated against in favor of Japanese fishermen.

Conversely, there were personal exchanges based on mutual consideration and trust in relationships between Japanese employers and Joseon employees. For example, Kim Yeong-sik worked at Tanabe (田辺) Store during the Japanese colonial rule. Kim completed elementary school in 1937 and could not attend middle school because he was from a poor family. The homeroom teacher made an arrangement for Kim to work at Tanabe Store. Kim started to work at the store at the age of 12 and worked until 1943. Tanabe Shoji (田辺正二), the store owner, trusted Kim for his sincerity. As Kim got older, Tanabe allowed Kim to take Tanabe’s place at Joseon Military Anti-Communism Guard where Tanabe served as a sentry. While working at the store, Kim officially became a member of the guard post in 1942. At that time, only Japanese people took the position of the head of the guard post, but Kim was promoted to the head and his monthly salary was increased to 30 yen. This case demonstrates the homeroom teacher’s character. The teacher helped a Joseon boy from a poor family who could not go to school by offering a job. In addition, it seems that Tanabe Shoji, the store owner, did not treat the Joseon employee harshly and let Kim take his job out of trust. Seeing that Kim was promoted to the head of the guard post when only Japanese had taken the position, it is observed that there was a private exchange between the Joseon and Japanese people, which was different from the colonial policies planned by the Japanese government.

Meanwhile, there are some records that convey how Koreans gave consideration to the Japanese people.43 When Japan lost the war, Kawasaki Jituo (川崎實雄) did not have rice at home and was unable to prepare a meal. At that time, his mother could not breastfeed her youngest child, who was eight months old, and a Joseon person in the neighborhood44 ground and brought her rice. This incident also shows that Koreans did not see Japanese people as colonizers from the Japanese government and that some human networks were formed at personal levels as humane aspects were mutually shared. However, unlike these mutually friendly attitudes, Joseon people were often ignored and conflicts arose. For example, Joseon boys often took the role of soldiers of the lowest rank when playing pretend military games. In addition, when someone lost their shoes at a public bath, Joseon children were suspected of theft. These incidents reflect the miserable and unequal relationship between colonizers and the colonized during the Japanese colonial rule in everyday life.

How, then, did personal exchange between the Japanese and Joseon people take place in social facilities, such as schools, public baths, and religious facilities?

Not only were Joseon people spatially segregated from Japanese people and lived in their residential districts, but they were also discriminated against in education. In May 1910, Japanese people opened Simsang Elementary School with three classrooms. Although the school admitted both Japanese children and Joseon children, the latter were charged double the tuition fee than that of the Japanese children. Joseon children also had to change their Korean names into Japanese names and wear Japanese-style clothes. It is said that Japanese students only spoke Japanese and played with among themselves and hardly socialized with Joseon students. Some Joseon girls who learned to speak Japanese worked as nannies for Japanese families to support their families.45 This shows not only the economic gap between the Japanese and Joseon people but also the reality of colonizers and the colonized.

There was no public bath culture in Ulsan. In the early days during the Japanese colonial rule, three public baths were built in Bangeojin. When the Japanese people tried to build public baths, Joseon people opposed construction because they did not accept the idea of people taking baths together in the nude. Therefore, it was difficult to initiate the construction.46 As seen here, there was a culture of being mixed together in migrant fishing villages while conflicts occurred. In 1915, the number of public baths increased to nine, including Hayashikane Public Bath. In the 1930s, there were two public baths in Bangeojin and Japanese in fundoshi waiting for their turn to

enter public baths was a scene to watch for Joseon people.47

Religious facilities for the Japanese49 were also constructed in Ulsan. The first Japanese religious facility in Bangeojin was the Pure Land Temple built in 1912. Higashi Hongan-ji was active and the temple formulated a plan to propagate the religion in a bid to assimilate the Joseon people.50

As seen above, Japanese people, who migrated to Joseon as part of Japan’s colonial policy, had a mutually friendly exchange with Joseon people on a private level as they hired Joseon fishermen and store clerks and interacted with Korean people in public life.

Conclusion

This study aimed to explore how Japan expanded its fishery bases in Joseon and colonized and ruled the coastal and offshore areas of Joseon and its fishery industry by analyzing the conditions and characteristics of Japanese migrant fishing villages in Ulsan. This study also examined how the private exchange between Joseon and Japanese people was formed during the colonial era.

There were free-migration fishing villages, such as Sinam, Sejukpo, Ilsanjin, and Jeongja, where Japanese fishermen migrated and settled to make a living and earn personal incomes by catching fish, such as sardines, sole, and cero. In the case of Jeonhari, it was initially an aid-migration fishing village, which was formed as the Shimane Prefecture government offered aid grants to have fishermen migrate and later more Japanese fishermen migrated by their free will. Bangeojin was a migrant fishing village formed based on the combination of free migration and aid migration. The establishment of those migrant fishing villages was managed as part of Japan’s colonial policies as the Japanese government intended to colonize Joseon. The Japanese government aimed to obtain the fishery resources of Joseon, and there was also a strategic intention to have Japanese people migrate to geographically important spots in the Korean peninsula and have a militarily competitive edge.

It can be said Japan weakened fish markets for Joseon fishermen as the fish caught in migrant fishing villages were freely traded and sold at fish markets in Busan and Busan Marine Product Store. It was also found that the fish caught in migrant fishing villages were carried to Japan to be used for military food procurement in times of war, as seen in Sinam, Sejukpo, and Bangeojin. The early process of the colonization of Joseon was confirmed through the Association of Japanese People formed in Bangeojin, which gave Japanese people the privilege to engage in commerce in Joseon and supported Japanese settlers, groups, and organizations that aided in the colonization of Joseon. Lastly, this study analyzed how private exchange between Joseon and Japanese people was formed during the colonial era. There were some disregard toward Joseon children when they played pretend military game and conflicts between Joseon and Japanese people at red-light districts, public baths, and schools. Conversely, the records about the Joseon person hired by a Japanese store owner and a Joseon person who gave considerations to Japanese people showed personal trust and friendly attitude between civilians beyond the relationship between colonizers and the colonized at a governmental level.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017S1A6A3A01079869).

Endnotes

References

- Daehanmaeilshinbo., July 26, 28, 1910. (Lee H. H., 2008. Bangeojin a Japanese Migrant Fishing Village and Trends in Communities. History and the World, 33: 73. Recitation.)

- Fishery Product Office of the Department of Agriculture, Trade and Industry., 1910. Korean Fishery Records, 2: 500-501, 507-508.

- Gyeongsangnam-do., 1921. Migrant Fishing Villages in Gyeongsangnam-do, 123-152.

- Institute of Oriental Studies, Dankook University., 2011. Life and Culture of the People Who Lived in Bangeojin, Ulsan, during the Japanese Colonial Rule. Chaeryun Publishers, 326.

- Kamiya, N., 2018. Modern Era Japanese Fishermen’s Migration to Joseon — Fishery Bases in Southern Joseon, Jangseongpo, Naro Island, Central Bangeojin. Singansa Publishers, 316-319.

- Kim M. J. et al., 2011. Ulsan Development. Ulsan Development Institute, 81.

- Kim, S., 2010. The Construction Process and Current Status of Japanese Migrant Fishing Villages in Busan, a Sea Port City. History and Boundary, 75: 26-27.

- Kim, S.H., 2004. The Organizational Process of Japanese Fishermen in Korea during the Opening Period. Fisheries Research, 20: 46-58.

- Kim, S.H., 2005a. Fishing Base Construction Plan and Japanese Collective Immigration. A Study on the History of Korean-Japanese Relations, 22: 123-155.

- Kim, S.H., 2005b. Mackerel Fisheries in the Japanese Colonial Period and Japanese Migrant Fishing Village. History and Folklore, 20: 165-190.

- Kim S, H., 2007. Jeju Female Divers’ Use of Fish Farms along the Southern Coast during the Japanese Colonial Rule and Conflicts. Region and history, 21: 312.

- Kono, N., 2011. Nakabe Ikujiro’s Management of Hayashikane Store Growth into a Fishery Conglomerate. Dongbang Hakji, 153: 282-294.

- Lee, H.H., 2008. The Bangeojin of Migrant Fishing Villages in the Japanese Colonial Period and the Trend of the Local Community. History and the World, 33: 33, 49.

- Lee J. H., 2016. Walking on the Modern Road of Bangeojin — Bangeojin Modern Cultural Heritage Story. Ulsan Studies Research Center, Ulsan Development Institute, 38.

- Park J. S., 2012. Memory and Trace of Bangeojin, a Japanese Migrant Fishing Village during the Japanese Colonial Rule. Korean Journal of Folk Studies, 30: 52.

- Takasaki, S., 2006. Translated by Lee Gyu-su. Japanese People in Colonial Joseon-Soldiers, Merchants, Geisha- Historical criticism Publishers, 3.

- Ulsan Agricultural and Fishery Product Show and Ulsan Information, 1917

- Ulsan History and Culture Encyclopedia. Folk Culture Encyclopedia.

- Yeo B. D., 2002. Japanese Empire’s ruling of Joseon Fishery and the Formation of Migrant Fishing Villages. Bogosa Publishers, 220.

- Yoshida, K., 1954, History of Joseon Fishery Industry Development. Joseon Waters Society Publishers, 159-174, 247-248.