The Maritime Boundary Dispute Between Slovenia and Croatia

Department of International Area & Cultural Studies, Graduate School of Korea Maritime and Ocean University, Busan, South Korea

Department of European Studies, Korea Maritime and Ocean University Busan, South Korea jms@kmou.ac.kr

Division of Global Maritime Studies, Korea Maritime and Ocean University Busan, South Korea

Abstract

Following the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1991, Slovenia and Croatia became independent nations. As the border between two nations had never been determined in details before 1991, several parts of the border, both on land and at sea, were disputed. After years of failed attempts to peacefully resolve the dispute and reach an agreeable solution on their own, the two Republics submitted their dispute to arbitration on November 4th, 2009. The first half of the paper presents past internal efforts to resolve the dispute with assertions from both sides. The latter part analyzes and interprets the final award issued by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), on June 29th, 2017. The PCA issued a ruling on the border: Ruling on the disputed areas of land border, drawing the border in the Gulf of Piran (or Savudrija/Piran), and made a determination of Slovenia’s ‘Junction to the High Sea.’ The PCA’s determination with respect to the land boundary was decided by the principle of uti possidetis, which doesn’t address the irreconcilable confrontation of arguments from both sides. The determination on the boundary with respect to the Bay of Piran (or Savudrija/Piran) was determined on the basis of uti possidetis and effectivités, as well. The determination of Slovenia’s ‘Junction to the High Sea’ was decided by applying international law, equity and the principle of good neighborly relations. The PCA’s determinations on the maritime boundary and Slovenia’s ‘Junction to the High Sea’ are welcomed by Slovenia but rejected by Croatia.

Keywords

Slovenia, Croatia, maritime boundary dispute, junction to the High Seas, the Bay of Piran, Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA)

Introduction

“Borders exclude and include, they are functional and symbolic at once, they help us to construct national, regional, local and European identities, they generate conflicts between people at various levels of interaction – and sometimes they even generate conflicts within people” (Andersen, 2011: 15). The topic of border disputes is a complex one, involving a variety of different aspects, which makes them notoriously difficult to resolve. International law still does not contain a clear, prioritized set of norms. Disputes often flare up after they become linked with important economic or social interests. Such areas may also be subject of historically based claims, cultural factors or demands for self-determination by their inhabitants (The Carter Center, 2010: VI).

From the 1950s, the delimitation of maritime zones is one of the main topics of international law. The period could be characterized by the tendencies of coastal countries to enforce sovereignty over increasingly larger sea areas. Maritime territorial disputes, to a great extent, threaten peace and stability all over the world. In Europe, the problem of demarcation has become even more pressing after the collapse of multinational states, such as Yugoslavia, where maritime boundaries were yet to be determined (Grbec, 2002: 255).

From the need to determine the boundary and Slovenian junction to the High Seas, the maritime border dispute between Croatia and Slovenia came to light soon after the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1991. After years of failed attempts to peacefully resolve the dispute and reach an agreeable solution on their own, the two Republics submitted their dispute to Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) on November 4th, 2009. Despite few unresolved issues along the land boundary, the fiercest and most important issues of dispute were all directly, or indirectly, connected with the Bay of Piran (or Savudrija/Piran) and Slovenia’s ‘Junction to the High Seas.’ Almost eight years later, on June 29th, 2017, the PCA issued the Final Award and determined the course of the maritime and land boundary between Slovenia and Croatia, and Slovenia’s ‘Junction to the High Sea’ (The Hague, 2017a).

Attempts at dispute resolution before entering the PCA process

Following the World War II, the area from north of Trieste to the Mirna River in the south, was part of the Free Territory of Trieste. In 1954, the Territory was dissolved. The area was provisionally divided between Yugoslavia and Italy. The division was made final by the Treaty of Osimo in 1975 (Gojkošek et al., 2017: 280-283). In accordance with a basic international law, succession or the disintegration of countries has no influence on the validity of treaties and the provisions that determine state border or territorial regimes. The border with Italy thus could not be changed (Grbec, 2002: 261). The federal government of Yugoslavia had successfully covered the internal conflicts between Slovenia and Croatia.

When Slovenia and Croatia both proclaimed their independence on June 25th, 1991, they simultaneously declared their mutual recognition, and that there were no outstanding territorial claims between them. Roughly one year after independence, countries jointly formed commission to demarcate their 670 km long shared land boundary, which brought to life several disputed points (Blake et al., 1996: 19).

The Brioni Declaration stipulated on July 7th, 1991, that the countries were committed to respecting the status quo of the existing border situation of June 25th, 1991. Despite the fact that maritime border between countries had never been officially determined, when it came to the question of control over the Piran Bay, a proclamation of the regional park and their protection, as well as investment planning, and regulation works on the Dragonja River, a leading role belonged to the municipality of Piran (Mihelič, 2007: 148). Respect of the territorial status quo, and particularly the principle uti possidetis juris, was also the course of events recommended by the Arbitration Commission of the International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia, in 1992 (Sancin, 2010: 94).

The history of efforts to peacefully resolve the border dispute between States first started in 1992, with the formation of the first working groups to deal with the border issues. The following year, the two countries established a Mixed Diplomatic Commission for Establishment and Demarcation of Slovenia-Croatia Border and Final Treaty on State Border. The Diplomatic Commission managed to resolve 15 out of 19 remaining land boundary issues, however, it was unable to find an exactable solution in the area of Dragonja River (the course of which has direct impact on the course of maritime border in Piran Bay) or an acceptable solution for the maritime delimitation (Drenik, 2009: 2). In 1995, both Slovenia and Croatia recognized the legitimacy of their claims regarding unresolved land border issues to respecting the status quo on the day of their independence, however failed to recognized legitimacy of each other’s maritime delimitation claims. In 1998, after a last unsuccessful meeting, the Diplomatic Commission completed its work, and the border dispute moved to the political arenas of both States.

The dispute appeared to have reached an acceptable solution in 2001, when the Prime Ministers of Slovenia and Croatia, managed to define the entire land and maritime border, and signed an agreement known as Drnovšek-Račan agreement. In the agreement, both parties agreed that Slovenia would receive about 80 percent of the Bay of Piran and a substantial portion of waters outside the bay (about 150 km2) and that the disputed terrestrial area south of the Dragonja River was to become part of Croatia (Mackelworth et al., 2013: 114). Both parties also agreed that a special two nautical mile long corridor in ‘a certain shape of a chimney’ would be formed and would have status of the High Seas, and that both ‘the chimney’ and ‘water tower’ would not be subject to sovereignty of either state. This solution would, at the same time, ensure open access to international waters for Slovenia and a territorial maritime border with Italy for Croatia (Durnik and Zupan, 2007: 83). Following its unanimous endorsement from the day before, Slovenian and Croatian governments initialed the Drnovšek-Račan agreement on the July 20th, 2001. Nevertheless, little more than one year later, in September 2002, the Croatian Prime Minster in letter addressed to Prime Minister of Slovenia, explained that Croatia could no longer pursue the conclusion of the agreement, and that its prior initialing had no legal effect (Sancin, 2010: 97).

In 2005, after a number of incidents along the ‘border’, the countries signed the Brioni Declaration to help avoid incidents. The purpose of the declaration was not about solving the border issues, but to ensure respect for the status quo as at June 25th, 1991, and to prevent further incidents. In July 2007, Slovenia proposed for the border dispute to be resolved through conciliation proceedings before the Court of Conciliation and Arbitration of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), which was rejected by Croatia. The following month, Croatia proposed that countries should resolved the maritime part of the dispute through the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), located in Hamburg. However, this proposal was rejected by Slovenia, since Slovenia insisted on a comprehensive solution of all disputed areas (Drenik, 2009: 2).

In August 2007, the Prime Ministers of both countries reached an informal agreement, the so-called Bled Agreement, which envisaged the submission of the dispute to an international judicial body. The countries appointed a Slovenian-Croatian team of legal experts, with the task of drafting a special agreement for submission of the dispute to arbitration in the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Since the team was unable to make any substantial progress, Slovenia officially concluded the negotiations in March 2009.

A major turning point occurred just before Slovenian parliamentary elections in September, 2008, when Slovenia decided to block the accession negotiations of Croatia with the European Union. The reason for this decision came from the belief that some Croatian actions in this pre-accession process constituted prejudices to the detriment of Slovenia, with regard to the final resolution of the border dispute. In order to lift their opposition, Slovenia wanted assurances from Croatia that it will eliminate all prejudices. In January 2009, the EU Commissioner for Enlargement, Mr. Olli Rehn, opened a new round of negotiations. After several proposals and amendments, he was unable to prepare an acceptable proposal for both parties. In June 2009, Croatia decided to withdraw from further talks. In the following month, however, both Prime Ministers agreed on further negotiations on the basis of three principles: Firstly, the withdrawal of Croatian prejudices in the pre-accession process; secondly, Slovenian consent to Croatia’s continuation of the pre-accession process where the obstacles were prejudices to the resolution of the border dispute; and, thirdly, the need to reach an agreement on the resolution of the border dispute. In September 2009, the Croatian Prime Minster sent a written statement to the Council of European Union, in which she declared that no document, map, nor any other unilateral act adopted after June 25th, 1991 would have any legal effect on the final settlement of the border dispute. Slovenia withdrew its opposition and the two Prime Ministers agreed on the previously rejected second proposal from Commissioner Rehn. On November 4th, 2009, the Prime Ministers of Slovenia and Croatia signed the Arbitration Agreement, which was afterwards ratified by both States (Sancin, 2010: 98-100).

Arbitration Process and Confrontation of Arguments

The arbitration process between Slovenia and Croatia was launched on January 17th, 2012, in Brussels. The European Commission established a list of candidates from which both parties, a by common agreement, appointed three members including the President of the Arbitral Tribunal. In addition, each party appointed a further member to the Arbitral Tribunal (European Commission, 2012), as would be shown later, in order to protect their country’s interests. On April 13th, 2012, the Arbitral Tribunal held its first procedural meeting with the representatives of both governments, and decided on the procedural framework for arbitration. In February 2013, parties submitted their first and written pleadings (Memorials), followed by second ones in November 2013, concerning the dispute between the two countries. The final arguments of both parties were presented in two week-long hearings, where appointed representatives from both states pleaded their cases on the disputed areas. The hearings, which were not open to the public, were conducted in two rounds and concluded on June 13th, 2014 (The Hague, 2014). The task of the Arbitral Tribunal was to determine “the course of the maritime and land boundary between the Republic of Slovenia and the Republic of Croatia” (Arbitration Agreement, 2009).

Croatia argued that the course of the land and maritime boundary must be determined first, and solely by application of international law. The stressed that only after this had been determined could the Arbitral Tribunal consider Slovenia’s contact to the High Sea, and the regime for the use of the relevant maritime areas (The Hague, 2014). However, almost five years prior the hearing Drenik (2009: 4) explained that the Article 3 (4) of Arbitral agreement clearly states that “The Arbitral Tribunal has the power to interpret the present Agreement”, which means that the court is not bound by the order of points a) the course of the maritime and land boundary between the Republic of Slovenia and the Republic of Croatia, b) Slovenia’s junction to the High Sea and, c) the regime for the use of the relevant maritime areas in Article 3 (1), and could start with point b) and determine Slovenian junction to High Seas before determining land and maritime boundaries. This was also confirmed during the negotiations, by the European Commission. ‘Slovenia’s junction to High Sea’ and ‘the regime for the use of the relevant maritime areas’ were to be determined by the application of ‘international law, equity and the principle of good neighborly relations.’ According to Croatia’s view, ‘equity and the principle of good neighborly relations’ were only to supplement ‘international law’ and should not be contrary to it.

Slovenia stressed that its vital interest is its direct geographical contact, to the High Sea (junction), which should be determined in accordance with Article 4 (b) of the Arbitration Agreement1. On numerous occasions since 1993, Slovenia clearly expressed that junction to the High Sea was its vital primary interest on numerous occasions since 1993, and was also an absolutely essential condition for Slovenia to sign and ratify the Arbitration Agreement. From the Slovenian point of view, Croatia’s vital interest was its accession to the European Union, which was accomplished after the adoption of the Arbitration Agreement. Therefore, this argument is unique by virtue of the task of the Tribunal and application of the law.

Croatia, on the other hand, contended that despite the fierce pressure of a Slovenian EU accession veto, they insisted that its maritime boundary was to be determined only by application of existing international law. As well as firmly maintaining the view throughout the negations and the hearings, that the term ‘junction’ did not amount to territorial contact with the High Sea, Croatia also claimed that their vital interest in the negotiations were not limited to EU membership, but were mainly focused to the preservation of its territorial integrity, and that they had never agreed to the notion that its territorial sea right could be determined in any other way than by the strict application of Article 152 of the 1982 United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS). As well as they stated that the maritime boundary was thus to be determined from the mouth of the Dragonja River where the land boundary terminus was located, by application of an equidistant line through the Bay of Savudrija/Piran (which were territorial waters, not internal waters) and beyond, up to the Osimo Treaty territorial sea boundary line with Italy. According to Croatia, the waters of the Bay have to be delimited between countries without regard regardless of their status.

Slovenia, however, claimed the entire territory of the Bay of Piran to be its internal waters, since it is considered an area of historical significance and was under Slovenian jurisdiction in the former Yugoslavia. The bay also maintained the status as internal waters after both countries proclaimed their independence. Therefore, based on the application of uti possidetis juris the whole bay belonged to Slovenia. “To the extent Croatia has occasionally patrolled a narrow strip along its coast, this could be dealt with by the regime.” Slovenia stressed that in accordance to the second sentence of Article 15, the “coastal concavity and the cut-off effect of the Istrian peninsula and Cape Savudrija, security, navigation, and Slovenia’s enjoyment of territorial sea and continental shelf right as a republic of the former Yugoslavia” must be taken into account as unique circumstances (The Hague, 2014). Slovenia argued that ‘maritime delimitation’, ‘junction’ and ‘regime’ referred to in Article 3 (1) (a), (b) and (c) in the Agreement, were distinct issues of the task, and that the Tribunal was obliged to comply with this to its full extent.

Alternatively, Croatia claimed that ‘junction’ and ‘regime’ could not affect the course of the boundary. According to Croatian view, ‘junction’ was limited exclusively to matters of maritime access and communications, if any existed at all. Slovenia’s interpretation of ‘junction’, however, was that the junction as a line joining Slovenia’s territorial sea to the High Sea, does not separate Slovenia from the High Seas by Croatia’s territorial sea or by potential an exclusive economic zone in the future. Croatia claimed that as a coastal state it has legitimate interests regarding navigation, security and defense concerns. As well, they pointed out, they also continue to have all the right of maritime entitlements, in the area southwards of Point 5 (45° 12.3’) of the 1975 Osimo Treaty line, which was excluded from any determinations by the Tribunal (The Hague, 2014). As argued by Vidas (2009: 36-37), the only way for Slovenia to be territorially connected to the High Sea, is, if Croatia should relinquish its territorial sea area situated north of point 5. This would basically require Croatia to transform part of its territorial sea into High Seas. Slovenia emphasized that the ‘regime’ they proposed was consistent with the UNCLOS, and “it would involve confirmation that the maritime regime to the south of Slovenia’s junction would remain High Seas, a regime which is consistent with Slovenia’s claim to a continental shelf,” starting at Slovenia’s ‘junction’ down to 45°10′ parallel of latitude. Slovenia also claimed 12 nautical miles of territorial sea, and that their historic fishing area right off the coast of Istria, now in Croatia’s territorial seas, were to be preserved (The Hague, 2014: 4).

Wiretap Scandal

On July 10th, 2015, after more than three years from the first procedural meeting with both countries, the Arbitral Tribunal informed both parties, that they could expect a final decision in December 2015 (The Hague, 2015a). When it already looked likely that the dispute would finally be resolved, a wiretap scandal placed the entire procedure into question. On July 22th, 2015, Croatian the newspaper Večernji list (2015) published illegally obtained audio tapes (acting on information first leaked in a Serbian tabloid) of traced telephone conversations between Jernej Sekolec, Slovene judge of the Arbitral Tribunal, and Simona Drenik, the representative of Slovenia’s Foreign Ministry before the court. According to Večernji list, contact took place during two telephone conversations on November 15th, 2014 and January 11th, 2015. The conversations included discussion on how to best present materials supporting Slovenian claims and influence the other members of the Arbitration Tribunal to rule in Slovenia’s favor. In addition, Sekolec disclosed deliberations of the Tribunal to Drenik, including that Slovenia would get what it wanted when it came to the demarcation of the maritime border, including that Slovenia would get at least two thirds of the Gulf of Piran. It was also mentioned that the demarcation of the land border was still undetermined, however, and that Slovenia might have to be more lenient in this regard (Večernji list, 2015).

Following these revelations, Sekolec and Drenik both resigned after the Slovenian Prime Minister demanded that they take responsibility for the scandal and announced that the Slovenian Government had not been aware of their communications (RTV Slovenia, 2015a). Slovenia acted fast, and on July 28th appointed French national Judge Ronny Abraham, President of the International Court of Justice, as a replacement for arbitrator Sekolec, however Judge Abraham resigned on August 3rd (The Hague, 2015b).

In the meantime, on July 27th after the meeting with political parties represented in the Croatian Parliament, the Prime Minister of Croatia announced that Croatia was irrevocably withdrawing from the arbitration (RTV Slovenia, 2015b). On July 30th, 2015, Budislav Vukas appointed arbitrator by Croatia, officially resigned, and the following day Croatia formally announced to the Tribunal that due to the scandal it could not further continue the process and was therefore terminating the Arbitration (The Hague, 2015b). On August 13th, 2015, Slovenia, in formal statements to the Tribunal, objected to Croatia’s termination of the agreement, and expressed that the Tribunal had the power and the duty to continue the proceedings. Slovenia also argued that Croatia could not terminate the Arbitration Agreement, since it had already achieved its vital interest and joined the EU through the operation of Article 9 of the Arbitration Agreement. Slovenia had refrained from appointing another member of the Arbitral Tribunal in order to preserve the integrity, independence and impartiality of the Tribunal, and the ongoing proceedings. They requested that the President of the Arbitration Tribunal replace Judge Abraham, and appoint a new member of the Arbitration Tribunal.

Croatia, however, ignored the invitation to appoint a replacement arbitrator (The Hague, 2015c). On September 25th, 2015, the Tribunal announced that it was reconstituted by the appointment of H.E. Mr. Rolf Einer Fife, a Norwegian national, and Professor Nicolas Michel, a Swiss national (The Hague, 2015d). In a letter from the European Commission sent to Slovenian and Croatian Prime Ministers, President Jean Claude Juncker and First Vice-President Frans Timmermans expressed support for the continuation of the work of the arbitral tribunal and their satisfaction at the appointment of two new arbitrators. While Slovenia welcomed the position of the European Commission, Croatia replied that they had withdrawn from arbitration and did not intend to comment further on moves of the Tribunal, nor participate in its work. They further stated that Croatia did not feel obliged to adopt, or to respond to any decision of the Tribunal (RTV Slovenia, 2015c). Croatia’s formal position was that it was entitled to terminate the Arbitration Agreement, since Slovenia “engaged in one or more material breaches of the Arbitration Agreement within the meaning of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, such that the impartiality and integrity of the arbitral proceedings has been irrevocably damaged, giving rise to a manifest violation of the rights of Croatia” (The Hague, 2016b).

In December 2015, the Tribunal set dates for further submission regarding questions arising from the aforementioned wiretap scandal and its intention to hold a hearing on these matters (The Hague, 2015e). Croatia, however, did not file any written submission, nor attend the scheduled hearing on March 17th, 2016. Slovenia, on the other hand, filed a written submission and addressed the Arbitral Tribunal at the hearing. Slovenia stressed that the Tribunal should complete its mandate and render an award, since the Arbitration Agreement was based on a quid pro quo, and while Croatia’s accession to the EU had been achieved, the Tribunal’s determination of Slovenia’s junction to the High Seas was still outstanding. “Slovenia elaborated that there was no impediment preventing the Tribunal from fulfilling its duty, and that the Tribunal possessed the tools to remedy the effects of any wrongdoing that may have occurred, in order to attain the object and purpose of the Arbitration Agreement. In particular, Slovenia suggested that the resignation of those involved in the events, the appointment of new arbitrators, and the critical inspection of the official record of the arbitration by the Tribunal constituted adequate means of redressing the purported breach of the Arbitration Agreement. If any additional reparation was sought, the only appropriate remedy for such non-material damages under international law would be a declaration of the wrongfulness of Slovenia’s conduct by the Tribunal” (The Hague, 2016a). Despite the absence of Croatia, the Tribunal decided that it is able and required to continue the proceedings, however the Tribunal expressed regret that Croatia did not explain its concerns more fully (The Hague, 2016b).

All further considerations by the Tribunal regarding the territorial and maritime border dispute remained suspended until June 30th, 2016, when the Tribunal issued a unanimous Partial Award concerning the legal implications of the matters set out by Croatia as their response to the wiretap scandal (The Hague, 2016a; The Hague, 2016b). “In its Partial Award, the Tribunal holds that Slovenia, by engaging in ex parte contacts with the arbitrator originally appointed by it, acted in violation of provisions of the Arbitration Agreement. However, these violations were not of such a nature as to entitle Croatia to terminate the Arbitration Agreement, nor do they affect the Tribunal’s ability, in its current composition, to render a final award independently and impartially” (The Hague, 2016b).

Tribunal’s Final Award

The Tribunal unanimously issued the Final Award on June 29th, 2017, and determined the course of the maritime and land boundary between Slovenia and Croatia, Slovenia’s ‘Junction to the High Sea’ and the regime for the use of the relevant maritime areas. Hereinafter we focus on the maritime determination of the boundary, while taking into the account only land issues related to the maritime determination.

The Bay of Piran (or Savudrija/Pran)

“The historic reason for the border dispute lies in changes of borders of the Municipality of Piran. Its cadaster borders were the result of miscellaneous use of land by various local communities”. (Pipan, 2008: 334)

The Tribunal concludes that the Bay of Piran had the status of Yugoslav internal waters prior to the dissolution of Yugoslavia and remained so after 1991. Therefore, the delimitation must be made on the basis of uti possidetis juris. Since there had been no formal division of the bay prior to the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the Tribunal considered that the delimitation must be made on the ground of the effectivités at the date of independence, especially with regard to the fisheries regulation and police patrols in the Bay of Piran. The Tribunal observes that during the whole period from 1962 to 1991 Slovenia alone organized the management of the fishing reserve in the area. They also noted that Slovenia was more active in their efforts to address the risk of pollution in the area. Regarding the police patrols, the Tribunal recognized that the local police of the Slovenian city, Koper, patrolled the area with two vessels, and that Slovenian police were more active in the Bay than their Croatian counterparts in response to accidents.

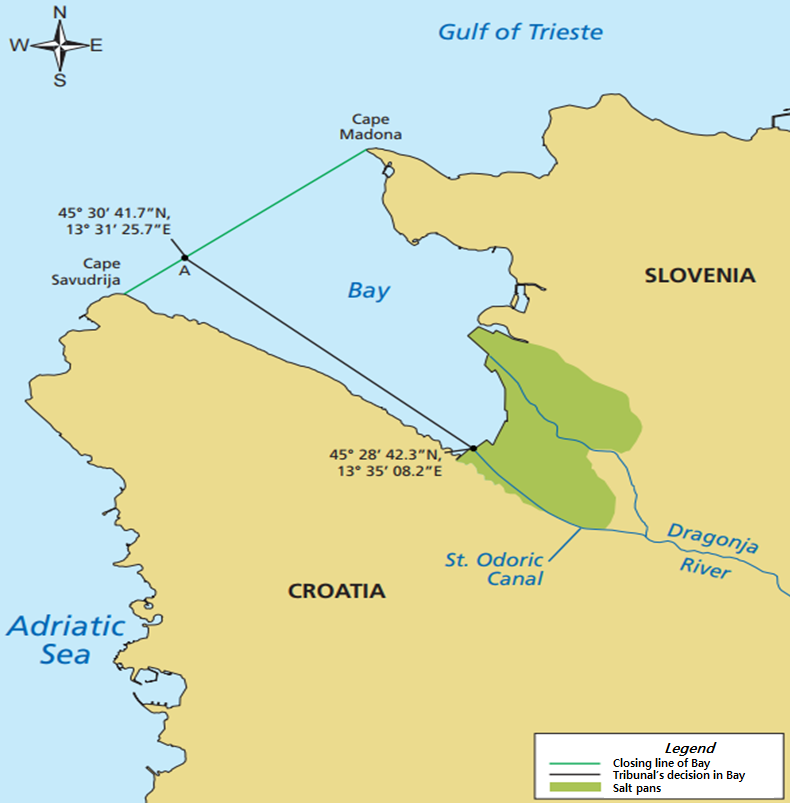

Based on these points, the Tribunal decided to split the Bay of Piran, from the mouth of the river Dragonja to point A on the closing line of the Bay (Figure 2), which is a distance from Cape Madona that is three times the distance from point A, to Cape Savudrija (The Hague, 2017a: 6-9; The Hague, 2017b: 3). The Tribunal decided and that the maritime border should be a straight line that connects the land border at the mouth of the Dragonja River to the point at the end of the gulf, which is three times closer to Croatia than to the Slovenian side, thereby awarding Slovenia 75% of the gulf.

The Territorial Sea

The territorial sea between the countries was delimitated in accordance with Article 15 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, and the settled jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice concerning the delimitation of territorial seas. The Tribunal observes that International law calls for the application of an equidistance line, unless another line is required by special circumstances. The Tribunal concludes that the equidistance line must be modified in a way to consider features of the coastal configuration as a special circumstance for delimitation.

The Tribunal observes that it is necessary to accommodate two principles: The first principle is the natural prolongation of the land territory into the sea, and the second is in the words of ICJ, that “the effects of incidental special feature from which unjustifiable difference of treatment could result” (The Hague, 2017a: 10). The Tribunal considers that features of the coastal configuration produce an adverse effect if the strict equidistance line is used, and do constitute a special circumstance. The coastline of Croatia turns sharply southward around Cape Savudrija, so the Croatian basepoints which control the equidistance line are located on a very small stretch of coast where the general (north-facing) direction is different from the general (southwest-facing) direction of the much greater part of the Croatian coastline, which deflects the equidistance line very significantly towards the north (The Hague, 2017a: 10-11).

Therefore, the equidistance line must be adjusted in favor of Slovenia in order to attenuate the ‘boxing in’ effect that results from the geographic configuration of the area. The determined maritime boundary between the two Republics starts at Point A on the closing line of the Bay of Piran and ends at Point B of the Osimo Treaty line, as indicated in Figure 3 (The Hague, 2017a: 12).

Slovenia’s ‘Junction to the High Sea’

Slovenia’s ‘junction to the High Sea’ was determined in accordance with international law, equity and the principle of good neighborly relations as laid down by Arbitration Agreement. The two Republics argued the meaning of the word ‘junction’. While Slovenia interpreted ‘junction to the High Sea’ as a direct geographical contact to the High Sea, Croatia argued that the term ‘junction’ did not amount to territorial contact with the High Sea (The Hague, 2017a: 13).

The Tribunal determines that “the core meaning of ‘junction’ is the place where two or more things come together or join” and that in the present case the word ‘junction’ stands for physical location that connects Slovenia’s territorial sea with the area beyond the territorial seas of Italy and Croatia. Turning to the geographical location of that connection between Slovenia’s territorial sea and the ‘High Sea’, the Tribunal observes that there is presently no place where Slovenian’s territorial sea is immediately adjacent to the area in which the applicable legal regime preserves the freedoms referred in UNCLOS Article 58 and Article 87 (The Hague, 2017a: 13-14; The Hague, 2017b: 3). The Tribunal thus determines that Slovenia’s junction to the High Sea must be established by creating an area in Croatian territorial waters where “ships and aircraft enjoy essentially the same rights of access to and from Slovenia as they enjoy on the high seas.” The established Junction Area is approximately 2.5 NM wide and connects Slovenia’s territorial sea with High Sea as indicated in Figure 4 (The Hague, 2017a: 15).

Furthermore, the Tribunal determines the regime that is going to apply to the Junction Area: In order to guarantee Slovenia’s uninterrupted and complete access from and to the “High Sea”, and to protect the integrity of Croatia’s territorial sea, the Tribunal recommends a special regime unlike any other previously established under UNCLOS (The Hague, 2017b: 3). The Tribunal determines “the content and scope of the freedom of communication” and “guarantees of, and limitations to, the freedom of communication” (The Hague, 2017a: 16-17).

Conclusion

Since the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1991, the formation of six independent states has created new issues, such as the emergence of groups of ethnic minorities within their respective borders (Gojkos, et al., 2017: 278). The ethnic conflict among the once-same citizens has seen further escalation with the matter of redrawing new frontiers among the recently-independent nations. In general, border disputes in the sea are much more complicated than border disputes on land, where the principle of uti possidetis applies, because they require consideration of a variety of precedents and circumstances, including the principle of effectivitos. Regarding the maritime territorial dispute between Croatia and Slovenia, both of whom became independent after the breakup of Yugoslavia, the article has presented the efforts to resolve disputes between the two countries and analyzed the principles and laws applied in the course of the PCI ruling.

The PCA’s determination with respect to the land boundary was decided by the principle of uti possidetis, which does not address the irreconcilable confrontation of arguments from both sides. The determination on the boundary with respect to the Bay of Piran (or Savudrija/Piran) was determined on the basis of uti possidetis, and effectivités at the date of independence, especially with regard to the fisheries regulation and police patrols in the Bay of Piran. The determination of Slovenia’s ‘Junction to the High Sea’ was determined by applying international law, equity and the principle of good neighborly relations. With accordance to freedom of communication referred in UNCLOS Article 58 and 87, the Tribunal determines Slovenia’s ‘junction to the High Sea’ must be established by creating an area in Croatian territorial seas in which “ships and aircraft enjoy essentially the same rights of access to and from Slovenia as they enjoy on the high seas.” Furthermore, the Tribunal determines “the content and scope of the freedom of communication” and “guarantees of, and limitations to, the freedom of communication” (The Hague, 2017a: 16-17).

The PCA’s determinations on the maritime boundary and Slovenia’s “Junction to the High Sea” are welcomed by Slovenia but rejected by Croatia. On 29 December 29th, 2017, Slovenia started implementing the arbitration ruling but only at sea, while Croatia continued to oppose it (RTV Slovenia, 2017).

As with the case of China's absolute rejection of the PCI decisions in China and the Philippines (Lee Jung-tae, 2016), the reality is, that the PCI's rulings on Croatia and Slovenia are not currently fully legally binding due to Croatia's opposition. But the parties to the dispute have an obligation under international law to negotiate faithfully to resolve the dispute. It is hopeful that a peaceful resolution to this dispute may be found. Therefore, it is very important to analyze the laws and the principles of the PCI's ruling on the disputed areas of the land border, the drawing of the border in the Gulf of Piran (or Savudrija/Piran), and the determination of Slovenia's ‘Junction to the High Sea’. This is because it is essential that the maritime territorial dispute be resolved through consultation among the parties and arbitration at the ICJ and PCA, rather than through military engagement.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2018S1A6A3A01081098).

Endnotes

References

- Andersen, Dorte Jagetic. 2011. Life in the Shadows of Geopolitics: Everyday Practices and Public Discourse at the Croatian-Slovenian border. Centre for International Border Research working paper series. WP23/2011. Belfast.

- Blake, Gerald. Topalović, Duško. Schofield, Clive. 1996. The maritime boundaries of the Adriatic Sea. International Boundaries Research Unit, Durham.

- Drenik, Simona. 2009. Arbitražni sporazum: potek pogajanj in dosežene rešitve. Pravna praksa, 28.45: 2-5.

- Durnik, Mitja and Zupan, Marjeta. 2007. Borderline dispute between Slovenia and Croatia in the post Yugoslav era: solutions, obstacles and possible therapy. CEU Political Science Journal, 2.1: 72-89.

- Gojkošek, Matjaž․Jeong, Moon-Soo․Chung, Chin-Sung, 2017. The Dissolution of Yugoslavia and the Emergence of a New Ethnic Minorities, Cultural Interaction Studies of Sea Port Cities, no.17, 277-320.

- Grbec, Mitja. 2002. Razmejitev morskih pasov v mednarodnem pravu : določitev meje na morju med Republiko Slovenijo in Republiko Hrvaško, Pravnik, Vol. 57, No. 4-5: 255-272.

- Lee, Jung Tae. 2016, China's the Construction of Artificial Islands in the South China Sea and PCA Ruling. Korea Political Science Society, vol. 24, no.4. 163-186.

- Mackelworth, Peter, Draško Holcer, Jelena Jovanović and Caterina Fortuna. 2010. Marine conservation and accession: the future for the Croatian Adriatic. Environmental management 47.4: 644-655.

- Mihelič, Darja. 2007. Ribič, kje zdaj tvoja barka plava? : Piransko ribolovno območje skozi čas. Založba Annales, Koper.

- Pipan, Primož. 2008. Border dispute between Croatia and Slovenia along the lower reaches of the Dragonja River. Acta geographica Slovenica 48.2: 331-356.

- Sancin, Vasilka. 2010. Slovenia-Croatia Border Dispute: From »Drnovšek-Račan« to »PahorKosor« Agreement. European Perspectives. Journal on European Perspectives of the Western Balkans, 2.2: 93-111.

- Vidas, Davor. 2009. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the European Union and the Rule of Law: What is going on in the Adriatic Sea? The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 24.1: 1-66.

- Arbitration Agreement. 2009. Arbitration Agreement between the Government of the Republic of Slovenia and the Government of the Republic of Croatia. 4 November 2009, Stockholm. Retrieved Oct. 2019 at: https://jusmundi.com/fr/document/other/en-arbitration-between-the-republic-of-croatia-and-the-republic-of-slovenia-arbitration-agreement-wednesday-4th-november-2009#other_document_6731

- European Commission. 2012. Press release: Launch of the arbitration process between Slovenia and Croatia. Retrieved May 2019 at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP12-25_en.htm?locale=hr

- RTV Slovenia. 2015a. Slovenija išče novega arbitra. Imenovati ga mora v 15 dneh. Radiotelevizija Slovenija (RTV Slovenia), Ljubljana. Retrieved May 2019 at: http://www.rtvslo.si/slovenija/slovenija-isce-novega-arbitra-imenovati-ga-mora-v-15dneh/370240

- RTV Slovenia. 2015b. Hrvaška odstopa od arbitraže, Haag pa želi pojasnila. Radiotelevizija Slovenija (RTV Slovenia), Ljubljana. Retrieved May 2019 at: http://www.rtvslo.si/svet/hrvaska-odstopa-od-arbitraze-haag-pa-zeli-pojasnilaslovenije/370496

- RTV Slovenia. 2015c. Cerar pozdravlja podporo nadaljevanju arbitraže iz Bruslja; Milanović: "Hrvaška je izstopila". Radiotelevizija Slovenija (RTV Slovenia), Ljubljana. Retrieved May 2019 at: http://www.rtvslo.si/evropska-unija/cerar-pozdravlja-podporonadaljevanju-arbitraze-iz-bruslja-milanovic-hrvaska-je-izstopila/375291

- RTV Slovenia. 2017. Hrvaška policija ribičem svetovala lovljenje še naprej. Radiotelevizija Slovenija (RTV Slovenia), Ljubljana. Retrieved Oct. 2019 at: https://www.rtvslo.si/slovenija/hrvaska-policija-ribicem-svetovala-lovljenje-se-naprej/441677

- The Carter Center. 2010. Approaches to Solving territorial conflicts: sources, situations, scenarios and suggestions. Carter Center, Mimeo.

- The Hague. 2014. Press release, 17 June 2014: Conclusion of Hearing in the Arbitration between the Republic of Croatia and the Republic of Slovenia. Permanent Court of Arbitration, Hague.

- The Hague. 2015a. Press release, 10 July 2015: Arbitral Tribunal Schedules Issuance of Award. Permanent Court of Arbitration, Hague.

- The Hague. 2015b. Press release, 5 August 2015: Republic of Croatia notifies its intention to terminate the Arbitration Agreement – Judge Ronny Abraham resigns from the Arbitral Tribunal. Permanent Court of Arbitration, Hague.

- The Hague. 2015c. Press release, 19 August 2015: Slovenia demands continuation of arbitration proceedings – Arbitral Tribunal clarifies further procedural steps. Permanent Court of Arbitration, Hague.

- The Hague. 2015d. Press release, 25 September 2015: Tribunal reconstituted by appointment of Norwegian and Swiss arbitrators, H.E. Mr. Rolf Fifeand and Professor Nicolas Michel. Permanent Court of Arbitration, Hague.

- The Hague. 2015e. Press release, 2 December 2015: Tribunal sets dates for further submissions. Permanent Court of Arbitration, Hague.

- The Hague. 2016a. Press release, 18 March 2016: Conclusion of Hearing in the Arbitration between the Republic of Croatia and the Republic of Slovenia. Permanent Court of Arbitration, Hague.

- The Hague. 2016b. Press release, 30 June 2016: Tribunal Issues Partial Award: Arbitration between Croatia and Slovenia to Continue. Permanent Court of Arbitration, Hague.

- The Hague. 2017a. Press release, 29 June 2017: Tribunal Determines Land and Maritime Boundaries in Final Award (long version). Permanent Court of Arbitration, Hague.

- The Hague. 2017b. Press release, 29 June 2017: Tribunal Determines Land and Maritime Boundaries in Final Award (short version). Permanent Court of Arbitration, Hague.

- UNCLOS. 1982. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

- Večernji list. 2015. EKSKLUZIVNO Donosimo audiosnimku razgovora arbitra i slovenske predstavnice! Poslušajte! Večernji list, Zagreb. Retrieved May 2019 at: http://www.vecernji.hr/hrvatska/ekskluzivno-donosimo-razgovor-arbitra-i-slovenskestrane-poslusajte-snimke-1015908