Continuing to Live on the Water: The Meaning of Land Residences for Boat Dwellers in Fujian, China

Anthropological Institute, Nanzan University, Japan

Abstract

For boat dwellers, what does it mean to acquire a house on land? Does it mean, as many researchers and government officials in modern countries have assumed, a departure from the “harsh world on the water” to salvation on the “enticing world of the land”? Through presenting an ethnographic study of the history of the lianjiachuan yumin (連家船漁民) living on the sea or rivers in the southern part of Fujian Province, China, this paper aims to explore the reasoning behind their way of life, which cannot be simply reduced to a one-sided move away from a nomadic life on water to settlement on land. The cases of the two families presented in this paper demonstrate that while on the one hand lianjiachuan yumin show a strong interest in acquiring houses on land, but after having acquired them, they are careful to avoid a situation where they are living solely in a residence on land, and instead seek to secure a situation where anyone, both individuals and family members, can live on the water at any time. This coexistence of the seemingly incompatible attitudes of both “the desire to acquire a house” and “the avoidance of continuous and permanent settlement” observed in the lianjiachuan yumin tells us that the world on water allows them to live a diverse way of life, and that it continues to exist as a valuable space for them to find their ways of life.

Keywords

boat dwellers, settlement on land, boats and houses, family history

1.Introduction

1-1. An a priori presupposition: “the world of water is a harsh and miserable place for people to live”

Boat dwellers have the following characteristics: (1) not owning land or buildings directly on land; (2) a single family living together with a small boat as a residence; (3) engaging in gathering the produce of the sea, selling their catch and exchanging it for agricultural produce to make a living; and (4) constantly moving nomadically around a certain area of the sea, never staying in one place for long (Habara, 1963:2-3).

Studies of cultural anthropology and folklore have found that boat dwellers not only in China, but also in regions such as Southeast Asia and Japan, have these characteristics mentioned above that give rise to the possibility of them becoming a target of discrimination and ostracism by land dwellers. Boat dwellers in different locations tend to have similar stories of loss (famine, poverty, conflict, oppression by other peoples, class discrimination, etc.), which have left them with no choice but to leave the land and live on boats (Habara, 1963:6-7; Nimmo, 2005 (1972):14, et al.), and it seems plausible that there is a close cause-and-effect connection between the unequal relations of land and sea dwellers, and the ownership of land and houses, or the lack thereof.

In other words, the two groups do not differ simply in terms of livelihood and lifestyle. Ownership of land and property, as well as the differences between life on land and life on water can often be an indicator that separates ethnic groups, upstanding citizens from the lowly, and the rich ruling classes from the impoverished ruled class. The important thing to note is that the boat dwellers are decidedly on lower end of the spectrum. In this way, the reality of living on the water has negative implications, both in terms of physical space and social position.

Nevertheless, in the process of modernization, a sense of commonality can be seen among boat dwellers throughout Asia as they undergo the experience of settlement on land and the acquisition of houses in some form. Regarding this process of settlement on land, many researchers have made the following points. To summarize these points, boat dwellers have been strongly influenced by changes in occupational practices such as the upsizing of fishing equipment and the spread of a market-based economic system, as well as the plans of government officials, such as the regulation of free movement accompanying the demarcation of borders and territorial waters necessitating forced movement; demands for family registration aimed at securing tax revenue, preventing avoidance of military service, and maintaining security; or reforms to education, welfare, and public health, which assume that people throughout the country belong to a homogenous group. Alongside this, in all areas, groups of boat dwellers with characteristics (1) to (4) mentioned above have been gradually disappearing, and will soon be (or already are) living like any other fisherman, or a life which is indistinguishable from land dwellers (Habara, 1963:8-11; Noguchi, 1992 (1976); Kani, 1970:164-175; Ward, 1985 (1965); Nimmo, 2005 (1972); Kim, 2007:233, et al.).

In light of these circumstances, many researches into the boat dwellers of China have sought to determine how their lives and folk customs have changed as a result of settling on the land (Ōta, 2008; Inazawa, 2016; Naganuma, 2010b;2013; Hu, 2017, et al.). On the other hand, there have been studies showing that the reality of settling on the land is not an easy process. For example, Naganuma Sayaka, focusing on boat dwellers in Guangdong Province who acquired houses about 50 years ago, presents a situation in which land dwellers in the same region in the present day view former boat dwellers as ethnically heterogeneous and refuse to accept them, despite the vocal insistence of the boat dwellers that they are already living in the same way as farmers and residents of urban areas. According to Naganuma, it is the remnants of their old lives on boats that appear in certain aspects of the daily lives of boat dwellers that serve as a basis to distinguish between former boat dwellers and those who have always settled on land (Naganuma, 2010a).

Indeed, while the state may give boat dwellers housing complexes and the same ethnic status at the Han Chinese, and though they may move their living spaces from the sea to the land, they are unable to completely become a true Han family of land dwellers. The appearance of boat dwellers as a sub-ethnic group of the Han family clearly demonstrates the following. Namely that the experience of living on the water in the past will continue to be imprinted as a negative memory that cannot be erased, affecting generations of children and grandchildren as well as those who actually experienced it.

Broadly speaking, there have been two positions in this debate. One simplistic position assumes that settlement on land greatly affects all aspects of life for boat dwellers, while a more critical position states that settlement on land does not have such a profound impact for land settlers other than those boat dwellers who were actually affected. What I would like to focus on here, is the fact that in essence these two perspectives are the same. That is, on the surface, there is the view that (A) as long as they acquire land-based houses, the boat dwellers inevitably shift towards a land-based lifestyle, and “settlement” progresses. Whilst on a deeper level, there is the viewpoint that (B) boat dwellers, who have in some sense been living as dispossessed people, want to leave the water and adapt or assimilate to life on land.

This is evidenced by the fact that, in many studies, staying on boats and continuing to live a nomadic lifestyle even after making the move to land, has been portrayed as a very exceptional thing done only by the poor and elderly who are unable to deal with sudden social change. However, researchers who adopt such an attitude of disregard towards these people are by no means ignoring them; they may in fact deeply feel emotions such as pity and compassion. One such story is that of Kani Hiroaki, who studied boat dwellers in Hong Kong in the 1960s. He spoke out about this in later years as follows. There was a tourist who wanted to take a photo, if, as a result of intensive ongoing land settlement, the curious sight of boat dwellers was nowhere to be seen. The tourist asked whether there would be no boat dwellers left in the near future, and Kani replied “I must say that I don’t think it would be such a bad thing if the boat-dwelling lifestyle were to disappear” (Kani, 1970:164). Indeed, above all for the sake of the boat dwellers themselves, something should be done to finish such pitiable ways of living as theirs.

Here we may notice a presumption that lies deeper than (A) and (B) mentioned earlier, something that bespeaks a more fundamental and less easily shifted perception; namely, that “the world of water is a harsh and miserable place for people to live.” This perception implies that the water is a space cut off from security, prosperity, cultural life, and all things of that nature. Naturally, as its polar opposite, the space of land is assumed to be the solution to all of them.

Because of this presumption, previous studies have a priori presented a very simple portrayal of a movement “from nomadism on the water to settlement on the land”, without even considering debate over the validity of the premise itself. However, upon closer inspection, this portrayal bears all too much similarity with the imagined predictions of modern politicians as they try to promote policies of boat dweller settlement (Ostensibly, such politicians claim that: "Living in a land-based house will not only protect them from the threats of nature, it will also become a shortcut towards accessing the market economy, the education system, and a hygienic and modern lifestyle” Whilst they also imply: "If we tame them, it will be much easier to control and govern them."). In addition, as Tokoro Ikuya points out, this portrayal gives rise to the possibility of viewing that the transition from the former to the latter as an inevitable and irreversible result of events such as the modernization of society and incorporation into a nation state (Tokoro, 1999:140).

On the contrary, this portrayal is synonymous with traditional Chinese thought that regards the people who live a nomadic lifestyle without settled farming in mountainous areas, deserts, grasslands and at the waterside as “barbarians”. It is also synonymous with “baseless ideologies of the superiority of settled peoples” in relation to the entire history of humankind, criticized by Nishida Masaki (1986), and James C. Scott (2013), which see the beginning of human settlement as the basis of the emergence of civilization.

1-2. Observing the people who continue to live on boats: Questioning the meaning of acquiring a house

However, a number of ethnographic descriptions have shown that such activities in real life are not that simple. For example, the Sama-Bajau of the Sulu Islands were active throughout a wide area in the territorial waters of various countries. With the establishment of nation states, they were incorporated into different countries (the Phillipines, Malaysia, and Indonesia), and were subject to various settlement policies as a result. However, the stilted houses built en masse from the 1950s on the coast have not brought them to settlement in a true sense. Rather, for around 10 to 20 years, they live on boats separate from the settlement sites, and engage in fishing, maritime smuggling, and even piracy, whilst boldly crossing between the newly established borders, seemingly leading to great profit (Tokoro, 1999; Nagatsu, 2001).

Furthermore, in Toyoshima, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan, ebune gyōmin (家船漁民: houseboat fishermen) who conducted fishing whilst living on board a boat, are said to have first appeared in the period between the Meiji and Taisho eras, when Japan was about to undergo modernization. People who became ebune gyōmin during this period included not only fishermen who had until that point engaged in fishing whilst owning property and houses on land, but also farmers who had been living a life completely unrelated to fishing. According to Kim Byungchul, this is strongly linked to a conflict over fishing grounds in this area that continued from the end of the Tokugawa period, meaning that Toyoshima was unable to acquire the same degree of access to the sea as neighboring villages, and thus the fishermen of Toyoshima attempted to go out to fish in distant places where such access rights did not apply. As a result, their boats changed to a form that accommodated both fishing and living as a family, and so the ebune gyōmin appeared, relying on boats for the majority of their livelihood and lifestyle (Kim, 2003:53-83).

These examples demonstrate the reality that there are people in many parts of Asia who, though they own (or originally owned) a house on land, either reside on boats living a lifestyle somewhere between nomadism and settlement or refuse to ever settle on land in the first place. In other words, we learn that for boat dwellers, “transition from nomadism on water to settlement on land” is neither inevitable nor irreversible. Most importantly, we learn that in reality living a nomadic lifestyle on the water does not mean existing in a constant state of “not being able to settle on land (for whatever reason), despite wanting to.”

In order to be true to such a reality, we must reject a priori viewpoints that conflate acquisition of houses with settlement on land or assume movement from nomadism on the water to settlement on land, and instead adopt an attitude in which we seriously consider the day-to-day practices of boat dwellers as they relate to living their lives. We must ask what meaning the acquisition of land and houses has for boat dwellers themselves. As we do so, it is important to explore the role that land and houses have in their daily lives through observing specific individual cases.

This paper focuses on two families of lianjiachuan yumin living in the southern part of Fujian Province, China, who have continued to live on boats after acquiring houses on land. We explore the circumstances surrounding the acquisition of houses for each family, the way that this has made the families feel, and how the families live their lives within the dual spaces of land and water. In doing so, we clarify what the acquisition of houses means to the lianjiachuan yumin, and what land and water mean to them in terms of space.

2. Lianjiachuan Yumin at the Mouth of the Jiulong River: Land Residence Acquisition History

2-1. Strained relations with farmers over the boat dwelling lifestyle

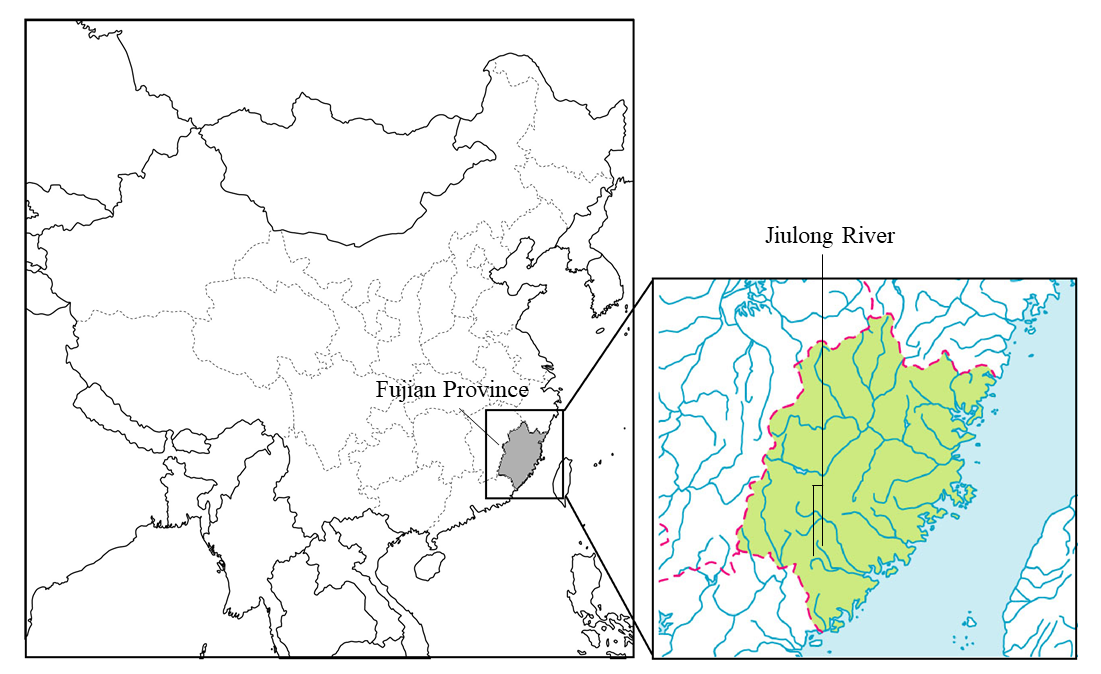

The Jiulong River, on which the lianjiachuan yumin have long resided, is a large river that divides from the mountains in the southwestern part of Fujian Province into northern, western and southern valleys and flows into the Taiwan Strait (Total length: 1,923km; basin area: 14,741km2. It is the second largest river in the province after the Min, which flows into the suburbs of Fuzhou) (Fujian Province Longhai Prefecture Chorography Editing Committee, 1993:6) (Figure 1). Each family of lianjiachuan yumin lives on their own boat in the area from the brackish waters of the Jiulong estuary to the Taiwan Strait. They live their lives catching fish and shellfish to sell in farmers’ markets and at roadsides along the coast, transporting their catch, timber and any daily necessities on the water.

There has been a conflicted and strained relationship between the lianjiachuan yumin and the people living in the rural areas along the coast. For example, farmers have ridiculed the act of living on a ship without land or a house, and the physical characteristics arise as a result. They have referred to lianjiachuan yumin as chuandiren (船底人: people who sleep on boats), or shuiyazi (水鴨仔: ducks), or qutizi (曲蹄仔: bow-legged people). The lianjiachuan yumin have felt something akin to self-abasement in relation to the farmers, to the extent that a marriage between the two groups has been considered utterly unthinkable (Chen, 2007:592; Haidi, 2010: iii) (Figure 2a, 2b).

Nevertheless, the boat-based lives of the lianjiachuan yumin would not be possible without dependence on rural communities for a supply of firewood, water, food and fishing equipment, for shipbuilding, as a place to sell their catch, and to escape typhoons and storms. In reality, they usually live a decentralized life through their boats, with bases in several rural communities dotted along the coast, such that dozens of families connected by paternal blood relations are able to berth their boats there when a typhoon strikes, or for the New Year celebrations and the like. Interestingly, the lianjiachuan yumin claim that there is a paternal origin relationship between themselves and the farmers who share the same names in the rural villages where their harbor bases are located. Despite having no family records or tombstones that show a clear genealogical relationship to each other in a visible form, both sides are able to share a group awareness of “being a member of a certain family who has the founder of a certain village as a common ancestor” (Fujikawa, 2017).

2-2. Collectivization policies and Settlement policies

The lianjiachuan yumin, whilst living an essentially nomadic existence on the water, also became involved in the wave of collectivization policies that developed across the country from the 1950s, after the establishment of the People's Republic of China. They were initially incorporated into various organizations, such as fishermen's associations, mutual assistance groups, junior and senior fishery companies, Fishery Production Brigades of People's Communes, and so on. As collectivization progressed, boats and fishing equipment became the property of these organizations, and income was distributed according to labor. Despite this, the vast majority of lianjiachuan yumin continued to live on boats in their family groups, living nomadic lifestyles dispersed around the mouth of the Jiulong River, engaging in fishing and transportation of goods (Fujikawa, 2013a).

However, as a result of a huge typhoon that hit the Jiulong River area in the summer of 1959, 132 lianjiachuan yumin drowned. 327 fishing vessels were also damaged in the catastrophe, and this became a turning point for lianjiachuan yumin to start acquiring property and houses on the land. To a large extent, this has also been the significance of the relief measures for the lianjiachuan yumin carried out by the local government. First, in 1960, the People’s Government of Longxi County ordered an agricultural production team to offer cultivated land on the banks of the Jiulong River tributary, invested 140,000 yuan, and built two two-story wooden apartment blocks for the Sm (a fictitious name) Fishing Production Brigade of the Sm People’s Commune, to which the lianjiachuan yumin belonged (Zhang, 2009:97-98). Subsequently, in addition to the collective housing, a net factory, shipbuilding factory, ice factory, fishery production factory, and a fishing port were built in the area. Additionally, lianjiachuan yumin who had not received collective housing also gathered in the ports of the various rural communities and berthed their ships, such that these places gradually began to function as bases for living and productive activities for more than 4,000 lianjiachuan yumin (Figure 3a, 3b).

For a long time after the disbandment of People's Communes in 1977, the Sm Fishery Production Brigade was an administrative organization named Sm Fishing Village and was treated the same as a rural area. However since 2003, in the nationwide trend of establishing shequ (社区) in urban areas, its name has been changed to the Sm Fishing Shequ of Longhai (龍海) City, Sm Subdistrict. According to statistics from 2006, the number of residents of the Sm Fishing Shequ is 1,258 households, and 4,544 people; the majority of them are lianjiachuan yumin except for a few married couples where the partner is someone from outside of the group. Sm Fishing Shequ currently has a total of 30 apartment buildings within its bounds, ranging from single-story to seven-story buildings. Lianjiachuan yumin who are unable to get a place there can also purchase or lease a room in a neighboring rural area or town apartment. The above is part of a series of waves of policies of settlement on land that started in earnest in the 1960s. As of 2018, excluding a very small number, about 99% of the families are living on land in some way (The remaining 1% reside on boats, which are described as "small boats" in the residence section of their household registration) (Figure 4).

This paper is based on the author’s own observations during long- and short-term fieldwork conducted intermittently in the period from 2007 to 2018 with Sm Fishing Shequ as a base. For the purposes of privacy protection, in order not to be able to identify individuals, pseudonyms are used for the individuals presented here.

3. The Case of Zang Yagun’s Family: A family living divided between boats on the water and houses on the land

3-1. Living on a Boat and Acquiring a Land Residence

The 1960s: The Boat-Raised Zhang Yagun and Leaving Behind Boats

Zhang Yagun (born 1944), the oldest son in a six-boy, three-girl family led by cast-net fishing parents, began helping with cast-net fishing and looking after his siblings after having turned five years old. He did not go to elementary school, and became a worker to support his family. The second-oldest boy in his family left his parents’ boat after growing up, serving in the People's Liberation Army. After turning twenty, Zhang Yagun moved to a fishing boat of another family that was no longer needed along with the third oldest boy in his family and two of his younger sisters. The four of them began engaging in cast-net fishing on their own.

First Half of the 1970s: Zhang Yagun’s Marriage and Labor Reform

At the age of 26, Zhang Yagun married the lianjiachuan yumin Huang Yajin (born 1951). At the time they belonged to the Lh People's Commune Lh Fishing Production Team. After getting married they moved to a fishing boat of the production team, and Huang Yajin gave birth to their oldest son Zhang Yaqiang in 1971 and their second oldest son Zhang Yaqiang the following year. However, in 1973 Zhang Yagun was falsely charged with a crime due to conflict within the production team, and was sent to farm-based labor reform, or laodong gaizao (労働改造).

Second Half of the 1970s: Housing Unit Acquisition

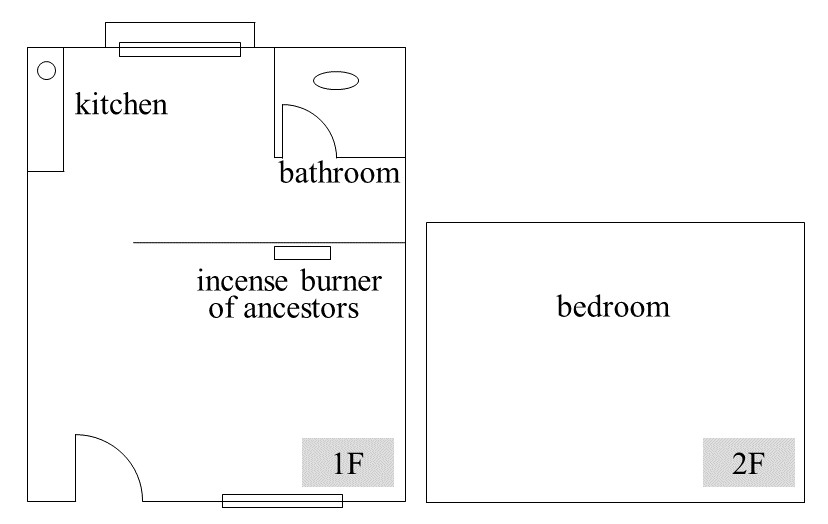

In 1977, when Zhang Yagun was in labor reform, the Lh Fishing Production Team was moved to the Sm Commune Sm Fishing Production Brigade, and its boats moved their berthing hub. At the time in the Sm Fishing Production Brigade housing units were distributed preferentially to older people who had children / grandchildren, and Zhang Yagun’s mother and father acquired the right to use one. His parents, who were in their fifties, announced their retirement and left their fishing boat. Having lost a worker due to his absence, Zhang Yagun’s wife, oldest son, and second oldest son decided to also leave their fishing boat and rent space in this unit. In a unit that was only 30m2, Zhang Yagun’s parents, young three brothers and sister, wife, two suns—a total of nine people—began living together. They built a second floor in this small unit with a board (Figure 5).

First Half of the 1980s: Renting Space in the Housing Unit

After Zhang Yagun had finished his sentence, he was ordered by the production brigade to become the captain of a shipping boat. His job involved going once or twice a day to the waters near Xiamen (厦門) Island and bringing fish caught by lianjiachuan yumin to the brigade's fishery products factory. At night, he would go home to his parents’ housing unit. His wife, Huang Yajin, was assigned to the brigade’s net factory. During the day she would weave nets, and at night return to her in-laws, nephews, niece, and sons to make dinner and the like. Subsequently Zhang Yagun became a crew member of the brigade’s motor sailor. Approximately twenty men and women lived on the boat while engaging in bottom trawl fishing in waters near other provinces. After doing so for four years, Zhang Yagun joined a fishing boat of the brigade, and fished for blue mackerel and squid using lights in the Taiwan Strait. For both of these jobs he would spend three to six months at sea, not returning to the housing unit during that time.

Second Half of the 1980s: From One Housing Unit to Another

During this time a change occurred at the housing unit of Zhang Yagun’s parents: his wife, Huang Yajin, brought her oldest and second-oldest sons to her own parent's housing unit. This was because there were incessant fights between Zhang Yagun’s very young brothers and his sons. Now six people were living at the housing unit of Zhang Yagun’s parents (his parents, three younger brothers, one younger sister), and five people at that of Huang Yajin’s parents (her, her parents and her two sons).

First Half of the 1990s: Building a Boat and Leaving the Housing Unit

In 1989, Zhang Yagun received a loan from a Rural Credit Cooperative, and constructed a shrimp net-fishing boat out of wood. Such boats were popular at the time. Since fishing required three to four people, his wife, oldest son (who had just graduated from high school), and second-oldest son (who had just graduated from a technical school), left the housing unit and began living on their fishing boat. This four-person family slept on this roughly fifteen-meter long, 4.5-meter wide, and 1.8-meter deep boat, and would go to the waters around Xiamen Island to fish shrimps with nets. During this period, their shrimp catches were very good (Figure 6).

Second Half of the 1990s: Purchasing an Apartment

In 1994, Zhang Yagun and his family borrowed money from an acquaintance to purchase a newly built apartment on a bank of the Jiulong River (two hundred thousand RMB). It was a 120m2 apartment with three bedrooms, a living room, kitchen, and bathroom with a shower and toilet. Zhang Yagun and his wife thought that their sons would be unable to marry if they did not have a residence on land, and decided to secure a space for them and their sons’ families to live together in the future. Eventually their shrimp catches took a turn for the worse, and in 2000 Zhang Yagun rented his shrimp fishing boat to another lianjiachuan yumin.

3-2. Life after Acquiring a Land Residence

Zhang Yagun and His Wife: Boat Dwelling

Zhang Yagun and his wife purchased a small used wooden boat (total length of about 7.0m, width of about 2.1m, depth of about 0.85m) and began fishing with it (Figure 7). From the second to eleventh months on the lunar calendar they would catch conger near Xiamen Island, and during the winter catch the likes of yellow croaker and blue mackerel with a gill net. During the summer off-season (1.5 months; violators are fined), at the beginning of the year, on ancestral ritual days, and so on, they would return to their apartment. Other than that, they fish at the fishing grounds, and live a life at the berthing places (usually a space on the water a little distance from the coast where it’s easy to avoid waves, with convenient access to a large port to go to markets on land and maintain a supply of fresh water) created by the gathering of boats of lianjiachuan yumin near to the fishing grounds, eating meals on their boat, maintaining their fishing gear, enjoying entertainment such as poker and Go, and sleeping.

Oldest Son, Zhang Yaqiang, and His Family: Living a Split Life on Boat and Land

Their oldest son, Zhang Yaqiang, married Wang Yazhen, his middle-school classmate from the city, in 1995. In 1997, their child Zhang Yiqi, a boy, was born. After they halted their shrimp fishing business, Zhang Yaqiang and his wife began working at a shoe factory in the city. However, in 2003, saying that boats fit him, he decided to go on a “sand ship” (Figure 8). It was work consisting of going to rivers inside and outside of the province in a large iron boat to excavate and transport sand used for construction. Having a boat operating license, he was hired as vice-captain. He only returned home to his apartment once every month to every six months (excluding the beginning of the year and when the boat was being repaired), staying on the sand ship. Meanwhile, his wife worked at the factory everyday besides Sunday.

Second-Oldest Son, Zhang Yaqiang, and His Family: From Boat to Land

Their second-oldest son, Zhang Yaqiang, married Zhang Xiuzhen, a lianjiachuan yumin, in 1996. In 2000, their child, Zhang Weiqi, a boy, was born. After stopping shrimp fishing, Zhang Yaqiang made a living by working as a fresh fish broker. In 2005, construction on a sea floor tunnel near Xiamen Island was beginning, and he received word that a ferry was needed. Having a boat operator's license, he had the shrimp net-fishing boat that had been lent out be returned, and piloting the ship with his wife, works on various jobs including: picking up and transferring workers to construction sites; raising and lowering the anchors of larger ships on construction sites; and chasing away protected Chinese white dolphins (to keep them out of harm’s way).

Unable to leave the site of his job, almost every day (excluding Lunar New Year) they would berth their boat on the ocean to the north of Xiamen Island and sleep on it. His wife, Zhang Xiuzhen, would find time outside of work approximately once a month to see her son at the apartment. In 2010, the sea floor tunnel construction was completed, and Zhang Yaqiang and his wife stopped doing transport boat work. He started working at a machine factory, and his wife at a factory cafeteria.

3-3. House-protecting Deities and the Sense of Unity as an Extended Family

After purchasing an apartment, the family moved the Fozu (佛祖: Goddess of Mercy), Sanping Zushigong (三平祖師公: founder of Sanping temple in Zhangzhou漳州 city), Tian Gong (玉皇大帝: Jade Emperor), and Zao Jun (竈君: Kitchen God) statues and incense burner from their boat to their apartment. They also installed a newly made Tudigong (福徳正神: God of the Soil and the Ground) statue, which they saw as being unrelated to their boat. The family left it to these deities to see to their apartment’s safety, bountiful catches, safety working at water, and family health. Zhang Yagun and his wife as well as the families of their two sons thereby came to have not only the right to live in the same land residence but also a feeling of unity as a yijiahuo (一家伙: one family) protected by these gods.

3-4. The Child-Raising Network: Extending Outside the Family

From 2005 to 2010, Zhang Yagun and his wife, their oldest son, Zhang Yaqiang, and their second-oldest son, Zhang Yaqiang, and his wife continued to live a nomadic boat life, living in their apartment only once every three to sixth months. There were only three people who were able to live out of their apartment: Wang Yazhen, the wife of the oldest son; Zhang Yiqi, the son of the oldest son; and Zhang Weiqi, the son of the second-oldest son. However, there was a major problem: there were no meals provided at kindergarten and elementary school, so children needed to eat lunch at their homes. However, Wang Yazhen, the only adult at the apartment, would leave at 7:00 AM for the factory every morning, and come home at 9:00 PM every night. She was unable to provide meals for them or see that they did their homework. In other words, there was a need for the family to find someone outside of the household who could take care of these two boys.

The family has tried to solve this problem by depending on relatives who live a life based on land. During weekday lunch breaks and after school, Zhang Yiqi would eat at the housing unit of the sister of his grandfather, Zhang Yagun (=FFZy), which was located in the Sm Fishing Shequ. At night, he would return home and wait for his mother. On days off from school, he would go to the company housing of his grandparents on his mother’s side, which was located in an urban area. In addition to eating lunch and dinner there, during his free time he would go to the house of a maternal aunt (=MZe), a high-school teacher who would help him with his homework. Zhang Weiqi was entrusted to the household of the niece (=BeD) of his grandmother, Huang Yajin, and her husband, who owned an apartment in an urban area. While eating and sleeping along with their children, he attended kindergarten and then elementary school, only returning home to his apartment when his parents and grandparents were home (Fujikawa, 2013b).

3-5. The Family’s Split Brought about by Eviction

For Zhang Yagun and his wife, at first the apartment that they purchased in 1992 was meant to be a residence that would allow them to live together as a yijiahuo and expand the family after their children and grandchildren got married. They thought that it was guaranteed that they would be able to use it forever, and therefore decided to pay a large amount of money for it. However, in the beginning of 2008, an urban redevelopment project to build embankments around the estuary of the Juilong River and expand roads was announced, and Zhang Yagun’s family was ordered to leave their apartment. Below I will discuss how their ideal of yijiahuo was shaken by examining the conflicts over housing in Zhang Yagun’s family brought about by this eviction.

The Eviction Order and the Anzhifang Compensation Plan

Several conditions were put in place upon eviction: 1. In accordance with the floor space of the residence that was the individual’s property, one could use for free a unit of a certain size in anzhifang (安置房: housing unit complexes for evicted individuals) in the city; and 2. If one leaves within the specified time frame, one will receive up to a certain amount of money to be applied to renting a residence until the anzhifang are complete. It was therefore decided that Zhang Yagun’s family would receive housing units in an anzhifang with a total floor space of 130m2, and that the city would give them 300 RMB per 1m2 for rent each month until it was complete.

However, there was a problem. They found out that there were only 70m2 and 80m2 anzhifang units. Zhang Yagun’s family originally wanted to have a space in which their eight-person yijiahuo could live together, and this would not be possible with 80m2. They then thought of at the very least getting two units on the same floor in the same anzhifang, which would make it easier to go back and forth between them. With units being assigned via a lottery, the family asked for help from all the connections they could think of, and were able to acquire two units (70m2 and 80m2) on the different floor. While it was not ideal, they thought that when the anzhifang was complete, Zhang Yagun, his wife, and their oldest son and his family would be able to live in the 80m2, and their second-oldest son and his family in the 70m2. However, they had to shoulder the roughly two hundred thousand RMB required for interior work as well as the sixty thousand RMB for their extra 20m2 in space.

Zhang Yagun’s family members became angry that they were being forced to move into two separate spaces that were smaller than the apartment they had previously purchased for two hundred thousand RMB, and also that they had to spend two hundred sixty-thousand RMB, which was a large sum. However, they did seem to have accepted the deal to avoid the worst situation of having to live far away from one another.

An Unexpected Split

While continuing to talk about things with one another, Zhang Yagun’s family began preparing to rent a temporary residence until the anzhifang was complete. Unable to rent a large space, the family decided to search for two properties near the Sm Fishing Shequ. In the end, Zhang Yagun, his wife, and their oldest son and his family (five people) rented part of a farming house, and their second-oldest son and his family (three people) decided to rent an older condominium that Zhang Yagun’s young brother, Zhang Jiacuhn, had purchased for his son, who was planning to get married.

The farming house rental consisted of a living room and bedroom, totaling 30m2. The kitchen was outside in the rear garden, simple, and not very usable. Zhang Yagun’s family shrine temporarily moved here. In contrast, the condominium rented by their second-oldest son’s family was spacious (120m2), with two bedrooms, a luxurious living room, highly usable kitchen, and bathroom that included a shower. Furthermore, it was also furnished and was more pleasant to live in than their previous one. The altar for Guandi(関帝: Guan Yu) and Tudigong of the previous owner was still installed in the condominium. At Huang Yajin’s recommendation, the second-oldest son and his wife carried out rituals for these deities only when they themselves were present in the condominium.

Subsequently, it became clear that Zhang Jiachun and his family—the owners of the condominium—did not really like their property. Zhang Yaqiang and his wife, having heard this, began contacting them in secret. Then they agreed to sell the 70m2 anzhifang in which they had planned to live to Zhang Jiacuhn’s son, and purchase the condominium from Zhang Jiacuhn. They covered the difference between the expensive condominium and the anzhifang unit by borrowing money from the family of Zhang Yaqiang’s wife.

The Residence and Deities’ Split

Upon finally hearing that Zhang Yaqiang and his wife were going to purchase the condominium, Zhang Yagun’s wife, Huang Yajin, became angry. Her dream was to have the eight of them live as yijiahuo in a single home. She could not understand why just Zhang Yaqiang and his family were going to live separately despite having made financial preparations as an extended family to live in the same anzhifang building, even if they could not live in the same unit. On the other hand, Zhang Yaqiang and his wife thought that since it was impossible for the eight of them to live in the same space at the anzhifang, purchasing the condominium would change nothing. Furthermore, Zhang Yaqiang’s condominium was easily accessible from the anzhifang, only three minutes away by foot. They wanted Haung Yajin to be happy that they had acquired a better residence. While Zhang Yagun's family continued to engage in discussions when everyone was on land, no one backed down for over a half of a year. In the end, though, Huang Yajin gave in, and permitted Zhang Yaqiang’s family to live in the condominium on condition that they would eat together at the annual seasonal festivals as a yijiahuo and that they would frequently visit each other's homes.

In the end, the anzhifang was completed in 2013, four years after the eviction order (Figure 9). Zhang Yagun, his wife, and their oldest son and his family (five people) lived in an 80m2 anzhifang unit, and their second-oldest son and his family (three people) lived in the condominium. While the eight-person yijiahuo continued in principle be one, the deities that had protected the family’s residence were divided between two homes.

The Inheritance of New Residences and The Possibility of A Further Split

In fact, Zhang Yagun and his wife own another residence. It is a single room (about 30m2) on the 3rd floor of a three-story apartment building that was distributed to Yagun’s parents by the then Sm Fishery Production Brigade in 1977. In the reforms and liberalization of 1990, this apartment was to be sold to the residents at a special low price of 4,200 yuan. However, Yagun’s parents voluntarily retired from all labor when they initially received the apartment (though healthy and in their 50s), and they had no savings, so Yagun’s wife Yajin decided to lend them 10,000 yuan to cover the costs of remodeling and purchase, under the name of their eldest son Yagun. Subsequently, Yagun’s parents lived there.

However, by 2017 Yagun’s parents had both died in close succession, and Yagun and his wife inherited the apartment. In the parents’ later years, their eldest son Yagun and his wife Yajin would take intermittent breaks from fishing to care for them, and the fact that the parents had originally owned the apartment was a deciding factor in the inheritance. Yagun and his wife received the apartment, and took breaks from fishing to renovate it, constructing a self-made mezzanine floor with wooden boards and ladders, transforming it into a room with a space for guests, kitchen, toilet, shower room, and bedroom (on the mezzanine). Presently, no one lives there, but Yagun and his wife may live there after retiring, and as they plan to hand over the anzhifang to their son Yiqi when he gets married, there is agreement among the family that Yagun and his wife can live in this apartment.

In this way, for Yagun’s family the inheritance of apartments that occurred in 2018 represents an increased possibility of the yijiahuo, which now constitutes three couples and their unmarried children (a total of 8 people), each living separately among three houses.

3-6. Land Residence Functions

As of spring 2018, Yagun and his wife have purchased a second-hand wooden ship one size larger than their previous one, and spend their lives on board, fishing with gill nets and longlines. Their eldest son is sand boat sailing in and around Fujian Province, and his wife works in a factory. Zhang Yiqi, the son of their eldest son, attends a vocational school in Xiamen that has a dormitory. In other words, the 80m2 anzhifang serves only as a place for the eldest son’s wife to spend the night. Their second son’s son Zhang Weiqi goes to high school from his parents’ place, and the condominium is the space where the three members of the second son’s family eat and sleep. Below we focus on Yagun and his wife who continue to live on the ship now, overviewing the way the houses are used and their functions.

Use of Land Residence

Zhang Yagun and his wife return to the harbor of the Sm Fishing Shequ only during the summer fishing off-season and for the four annual ancestral festivals, the Dragon Boat Festival, Lunar New Year, and so on. In fact, they almost never return to the anzhifang of their oldest son, where originally they were going to live in, primarily because it is difficult to ascend and descend four flights of stairs, and the kitchen is small and electric stove isn’t very usable.

So, where do Zhang Yagun and his wife “go home” to? When they berth their boat in the harbor, they bring freshly caught fish to their second-oldest son’s condominium. First, they take a bath and wash their hair. This is because on the boat, with there being little fresh water and no place reserved for bathing, they can only wipe their bodies with a towel, although they may be able to somehow wash their hair. After cleaning themselves and making lunch, they eat with their second-oldest son and his family. After eating, they take a nap separately using the living room sofa.

Boat Dwelling in the Harbor

After waking up from their nap they return to their boat and work on repairing nets, attaching weights to fishing lines, and installation of needles for longlines. While not working they might visit the boats of other lianjiachuan yumin to play poker or Go. They also have stores bring rice and propane to their boat, and make non-perishable food (sausage, pickles) on their boat (Figure 10). They even bring the bedding used by their family at the anzhifang and condominium to the boat for washing because it is easier to do on a boat than in a small household wash basin. Many lianjiachuan yumin who are living a life based on land impatiently wait for many boats to return to the harbor and liven up the place. When siblings, children, or friends return, they cheerily visit the boats and help out in fishing-related work while enjoying conversation.

In the evening, Zhang Yagun and his wife choose a place to eat dinner. When they eat on their fishing boat, they invite their grandchild to eat with them. When they eat on land, they bring food prepared on the boat to their second-oldest son's condominium, where it is cooked and eaten together. After dinner, Zhang Yagun and his wife return to their boat with their flashlights and charged batteries to sleep. They say that this is because boats, while cold in the winter, are cooler and more pleasant than land residences during the summer. Also, they’re scared about having thieves steal their fishing gear at night.

Sleeping on Land Only Several Days a Year

Zhang Yagun and his wife only sleep in a land residence around two nights a year. When a typhoon comes while they are docked in the harbor, they only spend one night at their second-oldest son’s condominium. In years with no particular problems, they might not even sleep on land at all. In other words, even if they return to the harbor of the Sm Fishing Shequ, they basically spend all of their time on their boat. This is just like how they do everything on their boat at the berthing spot in the ocean while fishing near Xiamen Island.

Land Residence Functions

For Zhang Yagun’s family, land residences function as spaces (1) to enshrine deities that protect their yijiahuo, (2) to store large household goods, clothing, and food, and (3) for securing a place for a very limited number of their family members to sleep. Also, (4) during the Lunar New Year and other important seasonal festivals the family gathers at one of their residences on land. Thus, it appears that for this family, comprised of many people who live on boats, land residences serve as a node that connects their yijiahuo.

Zhang Yagun’s family worked hard to acquire their residences on land. However, the functions that it performs for them do not mean that they have settled on land: their fluid lives have continued while straddling between land and boat for the approximately twenty years since their first acquired a land residence.

4.The Case of Ou Yaquan: Building a New Fishing Vessel Suitable for Retirement

4-1. The History of the Couples in Relation to Housing

The Ship-based Life of a Family of Four, and Their Sons’ Independence

From the 1980s, Ou Yaquan (born 1948) and his wife Zhang Yazhi (born 1954), along with their two sons who voluntarily dropped out of elementary school, piloted three boats of varying sizes and went out to fish the estuary of the Jiulong River, catching eels and anchovies with fixed flow nets. When their sons grew up and got married, they each lived in apartments purchased by Yaquan and his wife in Sm Fishing Shequ. The eldest son got a job at a paper mill, and the second son attaches net lifters and the like to large fishing boats.

On this occasion, Yaquan and his wife stopped fixed flow net fishing because it required at least three workers, purchased a small wooden fishing boat (total length of about 9.8m, width of about 2.9m, depth of about 0.9m) and started hook net fishing with two people, continuing to fish whilst living on board.

Disposing of A Fishing Boat, and Purchasing A Larger One

In October of 2017, Yaquan and his wife decided to scrap their fishing boat. This was because the fishing boat which they had been using for 18 years was in violation of age restrictions on boats, and so it became impossible for them to renew their fishing vessel certification and boat license for becoming old aged. They were also able to receive compensation if they submitted evidence to the agency concerned that the boat had been scrapped. This policy of providing compensations was originally part of national maritime protection policy comprising measures that relied on government efforts that were supposed to alleviate the rapid increase in the fishing population by encouraging fishing vessel disposal incentive schemes and limiting the age at which licenses could be renewed, essentially prompting fishermen to retire. This was in addition to a fishing boat disposal incentive system developed for the purpose of gradually reducing the number of old-fashioned wooden fishing vessels, which were considered highly likely to destroy the environment (with little concern as to whether this was in fact true).

However, contrary to the aims of the government, Yaquan and his wife promptly used the compensation granted to construct a new wooden fishing boat that was a size bigger than the previous one. In the same way as before, they registered the boat as a temporary fishing vessel, and continued to live as a couple on the boat, fishing at the Jiulong River estuary when the waves were calm, and returning to the port at Sm Fishing Shequ for important festivals such as the summer vacation season, ancestral religious festivals, Dragon Boat Festival, New Year, and also for periods of continued bad weather.

Rejecting Life in Apartment Blocks, and Continuing with a Boat-based Life

There is a reason as to why Yaquan and his wife built a larger fishing boat than the previous one they discarded. The couple, who continue to live on a boat, do in fact have a residence on the land that they should be living in. It is located on the top floor of a 5-story multi-family residential building made of reinforced concrete in the Sm Fishing Shequ that the couple had previously purchased for their second son when he decided to marry. The second son lives in this apartment block with his wife and son who is an elementary school student. The son tells Yaquan and his wife "If you stop fishing, we can live here together."

A few years ago, on one occasion their eldest son and second son consulted and applied to live in a low-rent housing for people with low incomes in Longhai City on behalf of Yaquan and his wife; however, this ended in failure as they did not meet the conditions. The second son, whilst assuming that he and his family will live together with Yaquan and his wife, anticipates that the space will be too small for five people once his own son has grown up. He has set up a hut assembled from tin plating on the rooftop of the apartment building, expanding the area of the house, and securing a space for Yaquan and his wife to live. (Similar methods are adopted by many families of lianjiachuan yumin; a privilege illegally afforded only to those who live on the top floor of a building) (Figure 11).

However, Yaquan and his wife do not like the hut. In particular, his wife Zhang Yazhi says “It’s hard to get up the stairs all the way to the roof, and the tin hut is in direct sunlight so it will get hot in the summer.” They insist that they “want to carry on living on the boat as much as possible, even after stopping fishing.” (The couple intend to be taken care of in the second son 's apartment if they ever feel inconvenienced by living on the boat because they are old and struggling physically.)

It was under these circumstances that the previously mentioned plan to scrap their fishing boat arose. The second son proposed the following to Yaquan and his wife: “If you plan to keep living on a boat for at least ten years, I will give you the money. Let's build a ship that’s convenient for two people to live in.” The construction cost of the completed fishing boat was just under RMB 30,000. The boat is superior to the previous one, with glass paint applied to its surface for the purpose of preservation. At present, apart from when they return to the harbor at Sm Fishing Shequ to visit their sons, or friends and family who live on land, or to go to various markets and parks, Yaquan and his wife continue to live their lives essentially carrying out most of their meals, laundry, repair of fishing nets, sleep, etc. on the ship.

4-2. A House as A Security for When Shipboard Life Cannot be Continued

Until now, Ou Yaquan and his wife have purchased residences on the land for their two sons in preparation for them getting married, and they have secured a hut that they can live in on the roof of the apartment block where their second son lives. In addition to this, they have also on one occasion sought to gain access to low-cost public housing in order to obtain a space specifically for them. At a glance, it seems that a land-based house would be an attractive prospect for the couple, and worth searching for. Perhaps in a certain sense this understanding is correct. However, when we carefully unravel the circumstances surrounding Yaquan and his wife’s own residence, their choice indicates a movement towards “only moving to a land-based house when they can no longer stay on a boat.” It is essential to be clear that the sheer fact is, the opposite is not the case.

For example, the institutional pressure of renewal of fishing vessel certificates and ship-handling licenses that directly affected Ou Yaquan and his wife in 2017 (whatever the government's plan may have been), in the first instance, would have led to a fundamental crisis for them in continuing their way of life, living on boats and engaging in fishing. However, in reality, it is clear that neither constraint has been the turning point that drove them into retiring from a life of fishing or changing both their living space and living style from boats on the water to units on the land. (Even to the extent of them risking flouting the rules.) Besides, given the fact that building a new fishing boat was based on the assumption that they would continue to live together even after retiring from fishing, at the present time, it seems unlikely that the end of their fishing lives will inevitably lead to the end of their lives on boats, and thus the beginning of their lives on land.

As such, the on-land residential space that they have secured is merely a security to provide for them if they find themselves in a situation in the future where their life on boats cannot be continued; it is neither more nor less than this.

5.What Does Acquiring a House Mean for Lianjiachuan Yumin?

Whilst they have struggled to obtain houses on land, and this has sometimes caused conflict within the family over the ideal way to live in a house, in reality, the family of Zhang Yagun comprises a large proportion of members who do not want to abandon a boat-based life even after acquiring enough houses for their family to live in. Meanwhile, Ou Yaquan and his wife, while acquiring and securing a space on land that they can live in when the time comes, have strived to continue their lives on boats even in the face of institutional pressure. Both cases demonstrate that acquiring a house does not mean the end of a boat-based life, or the start of a way of life that relies on land alone.

In fact, this fluid way of life, repeatedly passing back and forth between the two spaces of land and water, is not particular to the families of Zhang Yagun and Ou Yaquan. According to statistics from 2006, 77.3% of the total working-age population of Sm Fishing Shequ is engaged in work related to the water. This is also due to the fact that younger generations born after the 1960s, having only experienced being raised on land, are entering into a boat-based life anew. In other words, even though 99% of the population has now acquired houses, boats play a larger role than houses in both the lifestyles and livelihoods of many lianjiachuan yumin who continue a nomadic life on boats. If this is the case, we must ask why lianjiachuan yumin have sought houses, and what significance the spaces of land and water have for them.

5-1.The Outcomes of Wanting Houses: Approaching the World of Land, and Subdividing the Functions of a Boat

In reality, it is nonsensical to ask the lianjiachuan yumin why they want to acquire houses. Wanting to move into collective housing provided for settlement; or wanting to purchase collective housing sold off after the reforms and liberalization; or wanting to rent an apartment if you have the cash; or, if you get some savings, wanting to purchase a condominium or apartment; or, if these aren’t possible, wanting to move into low-cost public housing provided for people on low incomes – these are all quite natural desires shared among lianjiachuan yumin, and this is followed through. However, this has all been deeply internalized to such an extent that they can no longer vocalize an answer to the above question.

If this is the case, in order to find a clue as to why this is the case, we need to examine the path through history that the lianjiachuan yumin have taken.

Among lianjiachuan yumin, lore exists that their ancestors fell into poverty and were driven out of their farming village. They also sometimes make self-scathing remarks such as: “I don’t have a land residence so I cannot marry a farmer.” They have lived for generations on small boats facing the danger of drowning, shipwrecks, typhoons, and high waves. From their perspective, being assigned and purchasing housing complex units has seemed to be a way to leave behind lives in which they experience considerable scorn from land dwellers and danger. Even if some people were not assigned a land residence, insofar as they have settlement site on land, in times of emergency they can turn to their relatives and friends, and wait for the danger to pass, and if they simply have their relatives on land watch after their school-age children, these children will be protected from the danger of falling overboard and also be able to advance in school.

That is way the process of policies of settlement on land has been ingrained as a wonderful and joyful memory of acquiring land and a land residence (“Chairman Mao, thank you for the home that’s been my dream for many years!”). In fact, even in situations where uncritical praise for politics is not particularly required, the lianjiachuan yumin express their gratitude.

Land residences have opened new choices on water and land for lianjiachuan yumin. On water, it has become possible for them to leave their families on land and alone seek new workplaces in boats that cross provinces and countries. On land, on the other hand, it has become possible for them to do the same kind of jobs as land dwellers (government jobs, factory jobs, etc.). In this way, the trend toward acquiring a house on land not only divided family members’ work and living spaces into “water” and “land,” but also split up the functions of boats. In the past, boats were places to live in which people carried out the entirety of their lives. The trend toward settlement on land established a system by which lianjiachuan yumin could also enjoy education, social welfare services, medicine, and sanitation if they just drew closer to land. As a result, this has separated birth, education, illness recovery, and death from boats, moving these functions to hospitals, schools, and residences on land.

5-2. A Strong Desire to Acquire Houses, and Avoiding Ongoing Settlement: Is the World of Water a Miserable One?

At first glance, in relation to the situation described above, policies of settlement on land may seem like a timely decision that enabled the lianjiachuan yumin to be released from the pitiable misery of the water, pulling them up onto the alluring space of the land. However, to do so would be to disregard another factor; namely, the fact that the overwhelming majority of people have continued to work on the water, and their numbers still far surpass those that might be called "the last remnants of a former life on the water" or who have "failed to escape life on the water."

How do we understand this phenomenon? It should be noted that from the perspective of the lianjiachuan yumin themselves, the contempt which has been directed towards them from land dwellers has been due to the fact that they did not own property or houses on land, and not because they lived on ships, or lived an essentially nomadic life, or engaged in work on the water. Their testimonies demonstrate a state of coexisting attitudes that at first glance appear to be incompatible. Among the lianjiachuan yumin, there is both a “strong desire to acquire houses” which has been internalized to such an extent that it can no longer be verbalized, and “an avoidance of ongoing and irreversible settlement on land.” At the practical level, many of the lianjiachuan yumin show a strong interest (bordering on obsession) in having a house that they can occupy on land in some form, regardless of whether it is rented or purchased, simple or luxurious; however, they are only interested in whether or not they have a house in some form, and show a very inconsistent attitude in terms of how to actually use the houses that they have acquired with such passion. That is, the lianjiachuan yumin show complete indifference to how they live in the space of their houses on land.

In this way, we have an image of the lianjiachuan yumin as trying to live a life that spans both sides: going to great lengths to open up the possibilities of living on the land, without setting a clear boundary between the two worlds of land and water, and then also easily overcoming that boundary (or any elements that may appear to be a boundary). This indicates that, for the lianjiachuan yumin, the world of the water is not difficult, impoverished, or miserable.

With this understanding, the reader would do well to remember the examples of Zhang Yagun and Ou Yaquan and their wives. They have continued to live on their boats, whilst raising various seemingly trivial pretexts for doing so, such as “I don’t like climbing up the stairs,” or “the kitchen is narrow,” or “the electric stove is difficult to use,” or “the tin hut gets too hot in the summer.” By doing so, they seem to be carefully avoiding living solely in the houses that they supposedly secured on the land. (Indeed, when they reflect calmly on these pretexts, it is impossible for them to definitively explain exactly how a house on land is inferior to a small boat on the water.) Here we can see the important fact that the lianjiachuan yumin may yet want to retain the option to live in the world of water.

As the examples of these two families show, for lianjiachuan yumin, a house is necessary for entering into same life and livelihood as land dwellers, but it is not the case that acquiring one closes off the possibility of living in the water. Whilst they may acquire a house, for individuals, maintaining a ship (and its accompanying ship maneuvering license) or purchasing a new one that guarantees life and livelihood based on nomadism on the water, means that it is always possible to move in both directions. In other words, “if living on a boat isn’t working out, you can turn to a life on the land,” and “if living on land doesn’t go well, you can always go back to living on the water.” Furthermore, for families with multiple members, it is not necessary to fix the living space of everyone in either the land or the water. This means that, whatever the current situation, anyone, at any time is able to maintain a situation in which their life needs are met through living on both the land and the water, if they so desire.

Despite the development of science and technology, the water continues to be a harsh place. This is because it is a place exposed to nature, quite capable of taking human lives. Nevertheless, for individual lianjiachuan yumin and their families, it is not a space that they wish to consign to a distant memory. On the contrary, it is a space worthy of finding a way to live in, a rich space that allows them to live in a variety of ways. Finally, it is important to note that, paradoxically, for the lianjiachuan yumin, whilst the land is something other than the water, exactly like the water, it is a space with the hidden potential to cause difficult situations.

Acknowledgments

My heartfelt appreciation goes to participants of the 5th East Asian Island and Ocean Forum (2017 Matsuyama, Japan) who provided helpful comments and suggestions. Finally, this work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16K16968, and Nanzan University Pache Research Subsidy I-A-2 for the 2018 academic year.

Endnotes

References

- Chen Zhengtong (Ed.), 2007. Min nan hua zhang qiang ci dian, Zhonghua Book Company.

- Fujian sheng Longhai xian di fang zhi bian zuan wei yuan hui (Ed.), 1993, Longhai xian zhi, The Eastern Publishing Co., Ltd.

- Fujikawa Miyoko, 2013a. Lives of Sea Nomads in the Period of Social Change in Modern China. The Annual Report: The Study of the Study of Nonwritten Cultural Materials. 9:231-248.

- Fujikawa Miyoko, 2013b. Suijō no idōseikatsu wo sasaeru rikujō no shinzoku nettowāku: Chūgoku fukkenshō nanbu no suijō kyomin “renkasen gyomin” wo reini. Jisedai jinbun shakai kenkyū 9:231-248.

- Fujikawa Miyoko, 2017. Suijō ni sumau: Chūgoku fukken renkasen gyomin no minzokushi. Fukyosha Publishing Inc.

- Habara Yūkichi, 1963. Hyōkaimin. Iwanami Shoten, Publishers.

- Haidi, 2010, Xiao shuo mei you jin tou (dai xu), In: Fang Daming, Hai ba 3658, Hai feng chu ban she, pp. ⅰ-ⅷ.

- Hu Yanhong, 2017. Konan no suijō kyomin: Taiko gyomin no shinko seikatsu to sono hen'yo. Fukyosha Publishing Inc.

- Inazawa Tsutomu, 2016. Disappearing and Emerging Ethnic Distinctions within the Chinese Boat Community. Tohoku University Press, Sendai.

- Kani Hiroaki, 1970. Honkon no suijō kyomin: Chūgoku shakaishi no danmen. Iwanami Shoten, Publishers.

- Kim, Byungchul, 2007. A comparative study on houseboat fishermen in Asia (1), Journal of the Institute for Asian Studies. 34:233-249.

- Nagatsu Kazufumi, 2001. Umi to kokkyō: Idou wo ikiru sama jin no sekai, In Omoto Keiichi (Eds.), Umi no Ajia3: Shima to hito no dainamizumu, Iwanami Shoten, Publishers, pp. 173-202.

- Naganuma Sayaka, 2010a Kanton no suijō kyomin: Shukō deruta kanzoku no esunishiti to sono hen'yō. Fukyosha Publishing Inc.

- Naganuma Sayaka, 2010b. Gendai chūgoku ni okeru sōzoku shinkō no kanōsei: Kanton shukō deruta no suijō kyomin wo rei ni, In: Konagaya Yuki (Eds.), Chūgoku ni okeru shakai shugiteki kindaika: shūkyō, shōhi, esunishiti, Bensei Shuppan, pp. 277-298.

- Naganuma Sayaka, 2013. Sosen saishi to gendai chūgoku: Religion in Contemporary China, suijō kyomin no aratana girei no kokoromi, In: Kawaguchi Yukihiro (Eds.), Showado, pp. 185-202.

- Nimmo, Harry Alro, 2005. Firipin Surū no kaiyōmin: Bajau shakai no henka, Nishi Shigeto (Trans.), Gendaishokan. (1972 The Sea People of Sulu: A Study of Social Change in the Philippines, Intertex Books.)

- Nishida Masaki, 1986 Jinruishi no naka no teijū kakumei: yūdō to teijū no jinruishi. Shin-yo-sha.

- Noguchi Takenori, 1992. Kaijō hyōkaimin no rikuchi teichaku katei, In: Tanigawa Ken’ichi (Ed.) Hyōkaimin: ebune to Itoman. San-ichi Publishing Co., Ltd. pp. 389-409. (1976 Kaijō hyōkaimin no rikuchi teichaku katei, In: Seijō Gakuen Gojisshūnen Kinen Ronbunshū Henshū Iinkai (Ed.), Seijō Gakuen gojisshūnen kinen ronbunshū Bungaku, Seijō Gakuen, pp. 405-438.

- Ōta Izuru, 2008, renka gyosen kara rikuchi teikyo he: Taiko ryūiki gyomin to gyogyōson no seiritsu, In: Satō Yoshifumi (Eds.), Chūgoku nōson no shinkō to seikatsu: taiko ryūiki shakaishi kōjutsu kirokushū, Kyūko Shoin, pp. 47-67.

- Scott, James C., 2013. Zomia: datsu kokka no sekaishi, In: Jin Satō (Trans.), Misuzu Shobo. (James C. Scott, 2009 The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, Yale University Press.)

- Ward, Barbara E., 1985, “Varieties of the Conscious Model: The Fishermen of South China”, in Through Other Eyes: An Anthropologist’s View of Hong Kong, The Chinese University Press. (1965 “Varieties of the Conscious Model: The Fishermen of South China”, in The Relevance of Models for Social Anthropology, Michael Banton (ed.), Tavistock Publications Ltd. pp. 113-137.) Zhang Shicheng, 2009, Lianjiachuan yumin, private edition.