Island Sustainability and Inclusive Development: The Case of Okinawa (Ryukyu) Islands

University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa, Japan

Abstract

Okinawa, the only island prefecture in Japan, hosted the Pacific Leaders Meetings (PALM) three times in the past. The PALM-3 adopted “the Okinawa Initiative on Regional Development Strategies for a More Prosperous and Safer Pacific. Okinawa shares many common development issues with the Pacific island countries/regions including their history and cultural heritages, isolation, fragmentation, resource limitation and vulnerability to natural disasters and outside economic and political impacts beyond their control. As such Okinawa’s situation and experiences can be very useful regarding developing appropriate island models for sustainable and inclusive development.

This paper intends to respond to the challenges and opportunities raised in the PALM Okinawa Island Initiative. Particular focus will be on the roles of island culture, tourism and technologies for sustainable and inclusive development. The paper demonstrates that Okinawa’s champuru culture represents not only cultural diversity but also it empowers the local people through healthy lifestyle and warm yuimaru (mutual help) spirits. Okinawa is the only local prefecture in Japan whose population is still growing. There is a no-nonsensical joke that Okinawans will be the last Japanese to survive in the 25th century if the current depopulation on the mainland continues.

Keywords

Okinawa (Ryukyu) Islands, Pacific leaders meeting (PALM), Champuru culture, sustainable development (SD), sustainable island tourism, carrying capacity of island tourism & the road block, Okinawa’s green technologies, work collaboration

Introduction

Okinawa hosted the Pacific Leaders Meetings (PALM) with heads of fourteen independent and self-governing Pacific Island countries in 2003, 2006 and 2012. The PALM was held every three years since 1997. PALM adopted “the Okinawa Initiative on Regional Development Strategies for a More Prosperous and Safer Pacific.” This initiative emphasized the important role of Okinawa in spearheading and coordinating development and educational relationships among the Pacific islands: “Okinawa shares many common development issues with the Pacific island countries/regions including their small size, isolation, fragmentation, resource limitation and fragility, and vulnerability to natural disasters and outside economic and political impacts beyond their control. As such Okinawa’s situation and experiences can be very useful in terms of developing appropriate models for sustainable island development in this region” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2003:1). This manuscript intends to respond to the challenges and opportunities raised in the PALM Okinawa Island Initiative.

The latest PALM was held in Fukushima Prefecture in May 2018. The PALM Leaders affirmed that long-term efforts to shape their partnership through the PALM process which will be guided by the following shared vision (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2018).

- Maintaining stability through rules-based order : commitment to the respect for sovereignty, rule of law, and peaceful resolution of disputes in accordance with international law;

- Pursuit of enduring prosperity: self-sustained and sustainable economic development underpinned by open markets and facilitation of trade and investment, strengthened connectivity and enhanced resilience of societies;

- Strengthening the flow of and exchanges between peoples: active people-to-people exchanges to enhance mutual understanding, assist development and invigorate economic activities; and,

- Supporting regional cooperation and integration: advancement of robust regional institutions, with a view to greater regional cooperation and integration.

The PALM Leaders reaffirmed their commitment to continuing cooperation towards the universal implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the “SIDS Accelerated Modalities of Action (S.A.M.O.A) Pathway,” the Paris Agreement adopted under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda on Financing for Development. The Leaders acknowledged the efforts by the Pacific Island Forum (PIF) members and regional agencies to progress the region’s implementation of these commitments through the Pacific Roadmap for Sustainable Development. The PALM Leaders also shared the view that efforts to achieve resilient, sustainable and inclusive development will require addressing climate change with a sense of urgency. Given the existential threat and pressing contemporary security challenges that climate change poses to the future of the region, especially for island countries. The Leaders welcomed the accreditation of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) by the Green Climate Fund (GCF) Board, and the accreditation of Secretariat of the Pacific Environmental Program (SPREP) as a Regional Implementing Entity for the GCF and the Adaptation Fund.

Okinawa is also the birthplace of Nissology (the study of islands in Greek). The first meeting of the International Small Island Studies Association (ISISA) was held in Okinawa in 1994 under this author’s chairmanship. Nissology has now become a new field of scientific investigation on a global scale. Following the establishment of ISISA, the Japan Society of Island Studies (JSIS) was created in 1988. There are more than fifty active research and network institutions on Nissology, including Institute of Island Studies (Canada), Islands and Small States Institute (Malta), Small Island Cultures Research Initiative (Australia), International Scientific Council for Island Development (France), Global Islands Network (Germany), Center for Pacific Island Studies (Hawaii), Japan Institute for Pacific Studies, Center for Asia-Pacific Island Studies (Okinawa), Island Institute (U.S.A.), Dicuil Institute of Island Studies (Scotland), Society for Indian Ocean Studies (India), Institute for Islands Development (Estonia), Island Resources Foundation (Virgin Islands) and others.

Why have small islands attracted so many researchers in recent years? One explanation may be that researchers who have been marginalized in mainstream international academic forums for many years began to assert their identity as islanders. Another explanation may stem from the uniqueness and elusiveness of the islands as an object of scientific investigation. Their characteristics are vastly different from island to island. For instance, the Japanese islands named Takara Jima (Treasure Island) and Akuseki To (Evil Stone Island) are located side by side. Their names demonstrate the commonly-held, but contradictory images of islands as both paradise and hell or closure (prison) and openness (utopia). Because of the elusiveness of islands, including their definition and characteristics, mainstream, disciplined scientists have excluded “islandness” as a minor factor from their investigation. It is also true that an approach to island studies requires what Myrdal (1969) called a “multi- or trans-disciplinary approach” which is more complex than the conventional approach of scientific discovery. A comparative study between islands may deepen our understanding of the uniqueness and similarities of the island societies.

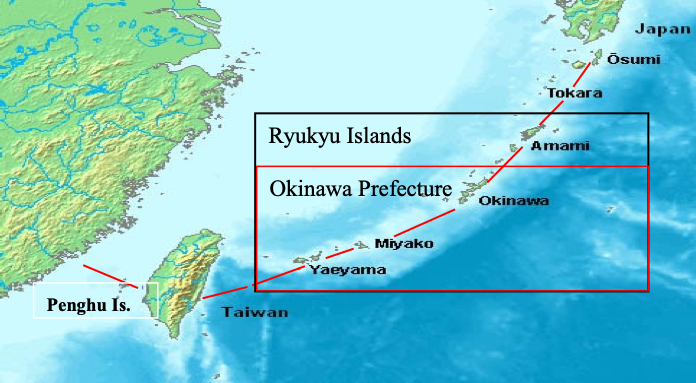

Geography of the Ryukyu Islands and Okinawa

Ryukyu Islands known in Japanese as the Nansei Islands (‘Southwest Islands’) and also known as the Ryukyu Arc (‘Liukiu Bogen’) are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan (Figure 1). The Ryukyu Arc is a reminder of a continental land bridge during glacial periods which spanned from 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago (Koide, 2007). The name “Ryukyu” first appeared in the Chinese history book of Sui in 607 (Kerr, 1958:448-449). The Ryukyu islands extend from the Amami islands to Okinawa’s Yaeyama islands with 174 islands, of which about 50 islands are inhabited. The origin of “Okinawa” is not clear. It literally means “the rope in the open sea.”

The island groups of Amami, Okinawa, Miyako and Yaeyama were subjected to the Ryukyuan Kingdom (1429-1879). The larger are mostly volcanic islands and the smaller ones are mostly coral islands. The largest of the islands is Okinawa. The climate of the islands ranges from the humid subtropical climate in the north to tropical rainforest climate in the south. Precipitation is very high and is affected by the rainy season and typhoons. Except the outlying Daitō Islands, the island chain has two major geologic boundaries, the Tokara Strait between the Tokara and Amami Islands, and the Kerama Gap between the Okinawa and Miyako Islands. The northernmost of the islands, Osumi, and Tokara Islands, fall under the cultural sphere of the Kyushu region of Japan; the people are ethnically Japanese and speak a variation of the Kagoshima dialect. The Amami, Okinawa, Miyako, and Yaeyama Islands have a native population collectively called the Ryukyuans although they cannot communicate easily with their own dialects. Administratively, the Amami island group belongs to Kagoshima Prefecture, while the southern part of the island chain belongs to Okinawa Prefecture.

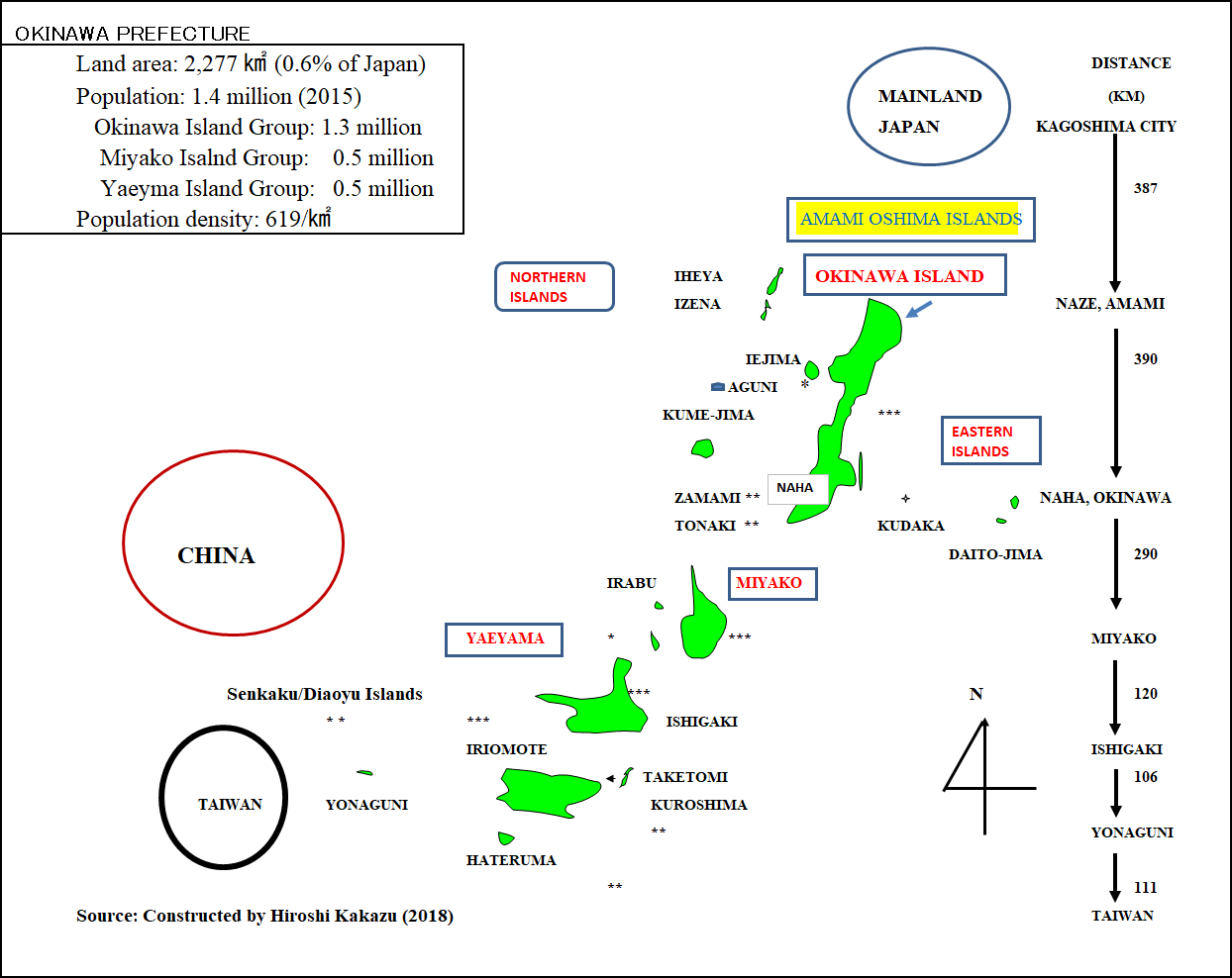

Okinawa is the only Japanese prefecture to lie wholly in the subtropical ocean climatic zone. It is located on the northwestern edge of the Pacific Ocean, just east of the Asian continent, and the southwestern tip of Japan with a total land area of 2,265 square km (874 sq. miles) . It spans a distance of 1,000 kilometers (622 miles) from east to west and 400 kilometers (248 miles) from north to south with 160 islands, of which 39 are inhabited (Figure 2).

The average annual temperature is 22.4 degrees Celsius, and average annual precipitation is 2,037 millimeters. Except for occasional typhoons during the summer, no natural disasters have been reported in recent years. Okinawa, with its abundant flora and fauna, including unique indigenous species such as the Iriomote wildcat, Pryor’s woodpecker and Okinawa rail, has sometimes been called the “Galapagos of the Orient.” There are few economically significant natural resources to be exploited. Currently, the most important natural resources are coral reefs and beaches which attract millions of tourists every year. There are 350 varieties of coral in Okinawa alone accounting for nearly half of the world’s varieties.

Champuru Culture of the Ryukyu Islands

The precise origin of Ryukyuan people is unknown. But historians and archaeologists believe that they migrated from China, Japan, Southeast Asia and Micronesia. The earliest human bones discovered on the Island of Okinawa indicated there were human life about 32,000 years ago. There are many evidences to indicate that the earliest inhabitants of these islands crossed a prehistoric land bridge from modern-day China (Takamiya, 2005). Culture is a way of living that is closely attached to a given land or society, whereas civilization could be considered the institutions and functional apparatus of living that can be utilized universally beyond land and society. These cultural traits are transmitted from generation to generation through the socioeconomic impacts of endogenous as well as exogenous forces, and they change over time.

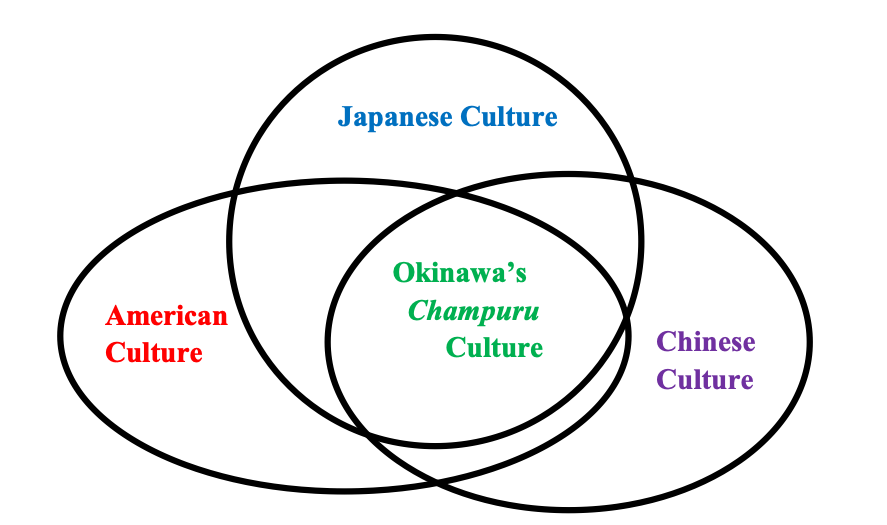

Ryukyu or Okinawa has undergone three major cultural transformations. The first was from 14th to 19th century when the Ryukyu Kingdom was a tributary state of China. The second transformation took place after the Japanese government forcefully dismantled the Ryukyu Kingdom and created Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. Japanese cultural influences actually began much earlier when the Lord of Satsuma invaded the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1609. The third transformation of Okinawa took place after the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. Okinawa fell under direct U.S. military occupation for 27 years, during which it was subject to different institutional systems from that of Japan proper. Additionally, the American way of life penetrated deeply into the island lifestyle. Each external influence served to shape Okinawa’s cultural heritage into a champuru culture, or mixed culture as is schematically depicted in Figure 3.

Chinese Cultural Influences

China played a dominant role in shaping Okinawa’s culture during the period not only in materialistic dimensions such as the introduction of sugarcane and sweet potato cultivations, handicraft and traditional dances which became major assets of Okinawa, but also in the practices of education and spiritual belief systems. Although the Chinese system of education was totally displaced by the Japanese system, particularly after the annexation of Okinawa by mainland Japan in 1879, “ancestor worship” and related rituals are still firmly rooted in Okinawa’s spiritual life. Family altars, tombs, obon, and eisa are all related to ancestor worship which combined with Okinawa’s ancient belief of animism, Buddhism and Taoism. The Chinese zodiac and the lunar calendar system still play important roles in Okinawa’s major rituals and festivals.

The most popular symbol of Okinawa is a lion-dog statue called a shisa (風獅爺 in Kinmen) which was introduced from China around the 14th or 15th century to ward off or deflect bad spirits. Shisa can typically be found at the entrance to main streets, buildings and the roofs of houses. It is unlikely that you can walk along the Okinawan streets without encountering strange looking, ferocious, yet various shaped humorous shisa figures. Similar shisa statues can be seen in Asia and mainland Japan, but the statue fits more comfortably in Okinawa than in any other country in the world because it is an essential part of Okinawa’s spiritual life. The shisa is the best-selling souvenir for tourists. This is a good example that Okinawa’s cultural assets can be commercialized.

Despite a long, pervasive history of Okinawa’s interactions with China, Okinawa does not have its own Chinatown. Contemporary History books tell us about “thirty-six Chinese families” (a term which means “many”) settling in Kume Village, present-day Naha City in the late 14th century (Kerr, 2000). They were mostly specialists in arts, crafts, administration and agriculture. “Of the Chinese customs introduced at this time and taken over into Okinawan life many became so well assimilated to local tradition and custom as to be indistinguishable today, but the origins of others remain traditionally identified with the founding of the village” (Kerr, ibid.). If we think of flourishing Chinatowns in mainland Japan and Southeast Asia, it is a great mystery why there are no remnants of a defined Chinatown. One explanation is Okinawa’s champuru culture totally absorbed Chinese culture.

Japanese Cultural Influences

There is much evidence that Okinawa had socio-cultural, economic exchanges with Japan long before Satsuma’s troops invaded Okinawa in 1609. The Okinawan dialect, for example, is considered to be a part of the Japanese language system (Iha, 2000). The Okinawan dialect contains numerous expressions of old-style Japanese. There are also a lot of common cultural heritages between Okinawa and mainland Japan, including animism and ancestor worship. Okinawans, however, are often distinguished from the mainland Japanese by their physical traits of “hairy, dark, big eyes and friendly smile.”

The Japanese influence on Okinawan culture, however, has become apparent, particularly in the areas of education and socioeconomic systems since the annexation of Okinawa in 1879. After several decades of a “hands off” policy towards new Okinawa prefecture, the Meiji government implemented various unification policies before the annexation. In the name of “modernization” and creating good “imperial subjects,” the old communal practices were abolished, and the Japanese school system was introduced. Introduction of nationwide compulsory education was probably the most important tool to assimilate Okinawa into the Japanese system.

The Japanization of Okinawa reached the peak of its intensity in the 1930s under the rising influence of Japan’s military power. The Standard Japanese Enforcement Movement was instituted in 1939 as a part of the national spiritual mobilization campaign. All school children were expected to speak fluent Japanese from the primary school level. In order to achieve this objective, a pupil who spoke Okinawan dialect or hogen on school premises was punished by means of hogen bura (方言札) or a dialect tag teachers hung on the necks of offending students, which could only be gotten rid of by passing it on to other students slipping into the tabooed language. “The hapless student who was still tagged at the end of the day had to go home earning the badge of humiliation. Sometimes, in desperation, an offender would hit unsuspecting classmates in the hope of eliciting an exclamation, which, naturally would come in dialect rather than in standard Japanese” (Field, 1991:72). I vividly remember that the hogen bura was practiced long after my childhood in the postwar period. It is rather ironic that the Okinawa hogen is becoming popular among young tourists from mainland Japan as well as foreign visitors. There are several classes that teach hogen to visitors.

Most of the Okinawan elite supported the forced assimilation policy, believing that Okinawans were discriminated against by mainlanders because they could not speak proper Japanese. If Okinwans spoke standard Japanese, then they would not suffer discrimination. “Okinawan elites employed to minimize fundamental cultural differences with the mainland” (Smits, 1999:151). According to Masao Higa (2003), the practice instilled in the mind of the younger generation a sense of cultural inferiority. The Late governor of Okinawa Prefecture, Junji Nishime used to say that Okinawans wished to be good Japanese since the late nineteenth century onward, but we could not make it. “There is still a pervasive anxiety about speaking ‘correct’ Japanese. Language is the most elusive, because subtle, traitor. If all visible difference between peoples could be effaced, speech would still threaten to betray cultural difference, to be easily thought to have a genetic, and therefore racial, origin. The waves of programs to eradicate this difference Okinawan prewar continued into the postwar (Field, op. cit.).

Prior to Okinawa’s annexation in 1873, the Japanese Ministry of Education declared that national Okinawans as new “imperial subjects” must follow the national educational policy. The essence of the policy called kokutai (literally nationality) was to install absolute loyalty to the emperor who was a “living god” in all subjects. Okinawa’s schools established the hoanden in particular, which housed the emperor’s photograph and “The Imperial Message on Education.” The Message starts with “Our Imperial Ancestors have founded Our Empire on a basis broad and everlasting and have deeply and firmly implanted virtue. Our subjects ever united in loyalty and filial piety have from generation to generation illustrated the beauty thereof. This is the glory of the fundamental character of Our Empire, and herein also lies the source of Our education…” (Field, 1991:69)

American Cultural Influences

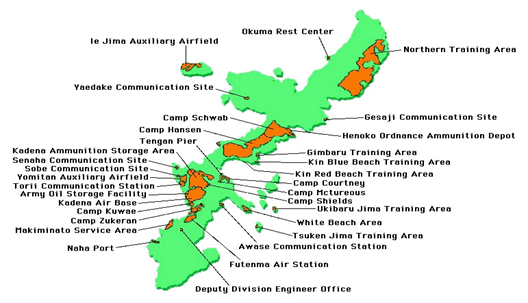

America, or more precisely, the United States Department of Defense at the Pentagon ruled Okinawa for twenty-seven years from 1945-1972. Huge U.S. bases remain, including Kadena Air Base, the largest airbase in the Far East.

Among 32 U.S. military facilities, the Kadena Air Base is the hub of airpower in the Asia Pacific, and home to the Air Force’s largest and world-class combat operations with about 18,000 Americans and 4,000 Japanese employees. The relocation of the Marine Corps Futema Air Station, which is located in a densely populated residential area, to Camp Schwab has been the most controversial issue between the Okinawa Prefectural Government and the Japanese Government (Figure 4).

The American influence on Okinawan culture came mainly through military base activities. American bases gave birth to “Okinawa rock music” which became a brand name of Koza (current Okinawa) city located near Kadena Air Base. The rock music, combined with traditional Ryukyuan music and shimauta (island songs), produced a unique music culture in the postwar period. Okinawan popular singers such as Namie Amuro, Kiroro, Da Pump, Speed, Max, Shokichi Kina, Orange Renge to name a few, gained enormous popularity in Japan and Asia. Namie Amuro in particular, who dominated Japan’s R&B and pop music and culture in the late 1990s and early 2000s, was a product of U.S. bases in Okinawa because her grandfather was a U.S servicemen stationed on the island of Okinawa. Amuro quickly became a commercial success, producing several million-selling records and starting several fashion trends. Her single “Can You Celebrate?” (1997) became Japan’s best-selling single by a solo female artist.

Okinawans also picked up American food habits mainland Japan. The first fast food introduced in Okinawa and Japan was “Papa Burger” with root beer, a product of A&W, long before McDonalds became popular in Japan. Okinawa is still the only place in Japan which houses A&W fast food restaurants. American food culture definitely adversely affected Okinawa’s proud history of world-renown longevity discussed later in this paper.

One of the most important cultural legacies of American occupation of Okinawa may be “anti-war culture.” Since the end of WWII, Okinawa has been the “Keystone of the Pacific” for the defense of the U.S. and Japan. The San Francisco Peace Treaty, concluded between the United States and Japan in 1951, mandated huge military bases on Okinawa. Even after forty-five years of Okinawa’s reversion to Japan, Okinawa still hosts about 70% of all U.S. military bases in Japan although Okinawa is only 0.6% of Japan’s total land area, and the bases are continuously a hot socio-politico-economic issue.

The Peace Memorial Park and Museum, which is a legacy of the U.S. involved Pacific War. The most visible symbol of the park is the Cornerstone of Peace which was unveiled in June 1995 in memory of the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Okinawa and the end of World War II. When US President Bill Clinton visited the Cornerstone of Peace in 2000 he delivered a speech promising efforts to reduce and consolidate US bases in Okinawa, as previously agreed by the US and Japanese governments. The Cornerstone of Peace is inscribed with the names of all those who died, regardless of nationality, civilian or military status. As of June 2015, there were 241,336 names. The breakdowns of the inscription are 149,362 from Okinawa Prefecture; 77,402 from other prefectures of Japan; 14,009 from the USA,; 82 from the UK; 365 from the Republic of Korea; 82 from North Korea; and 34 from Taiwan. A significant aspect of the Battle of Okinawa was the greatest loss of civilian life which far outnumbered the military death toll.

The U.S. bases have been the most controversial socio-political and economic issue since the inception of the U.S. occupation of the island. It is not an exaggeration to say that Okinawa’s daily life has revolved around U.S. bases. Okinawa’s economy has been and is still dependent on U.S. bases. This was the case particularly in the 1950s and 60s. At the same time, however, bases have always been associated with The Battle of Okinawa, which devastated not only the Islands’ properties and priceless cultural assets preserved for centuries, but also implanted a key “cultural cord” into the minds of the islanders, namely nuchidotakara (life is the most precious thing in the world). The anti-base movements have intensified as time has passed not only from the standpoint of anti-war sentiments, but also due to the detrimental consequences of having bases in Okinawa such as environmental pollution and heinous crime committed mostly by the Marines which make up more than sixty percent of the troops stationed on Okinawa. Hamamoto, a Hawaii born UC Davis professor, describes the presence of US bases on Okinawa as “soft colonialism” which, unlike “neo-colonialism” or “postcolonialism”, functions culturally and physiologically to maintain unequal, exploitative political relationship (Hamamoto, 2006).

It is interesting to note here that despite the U.S. occupation of Okinawa, including the use of the U.S. dollar as Okinawa’s legal currency, Okinawa never picked up the custom of tipping. Compared with Hong Kong, Singapore and the South Pacific which were under British and American colonial rules, Okinawa’s overall English proficiency is lower. It also never surpassed that of mainland Japan, which was occupied by the Americans for seven years.

Although the majority of islanders are against the presence of the U.S. bases, they are fully aware of the economic consequences of the base withdrawal. Researchers have just begun to investigate how the presence of U.S. bases, which is an enclave zone in Okinawa, intertwine with the local culture and shaped Okinawa’s lifestyles positively as well as negatively (Yamazato, 2005). It will take time to untangle the complex knots of cultural influence and confluence.

Okinawa: The Real Shangri-La?

Even “traditional” culture is subject to change over time, and quite often it changes without notice by the indigenous people. As we have seen, Okinawan culture has changed gradually, due to external interventions as well as by self-generating endogenous forces. For a small island society, external forces can render significant changes. Okinawan culture, notably music, dance, language and Okinawan food (pork), however, recently have become popular in the Japanese mainland and abroad. Eating pork has been looked down upon in Japanese society for many decades. “The third-party appreciation” of the Okinawan culture has provided the Okinawan people with enormous pride in their culture and identity, and it encouraged the promotion of local cultural activities such as traditional music, dances, karate, arts, healthy foods including pork dishes and even uchinaguchi (Okinawan dialects) which were considered as an inferior language in the past. This is what I call a “cultural virtuous circle.”

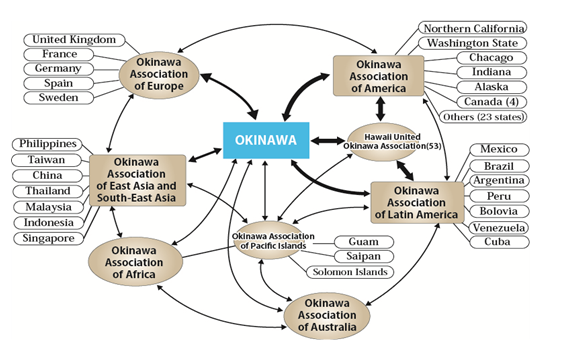

The virtuous circle is typically demonstrated by the activities of overseas Okinawans, or “Uchinanchu” in the local dialect, who migrated to Hawaii, North and South America, Southeast Asia, the South Pacific and other areas (Figure 5). It is estimated that these overseas migrants and their descendants, excluding mainland Japanese, numbered about 400,000 in 2011. In the past, Okinawa quite skillfully balanced her limited land resources, particularly in terms of food production, with population growth. Like many other small islands, out-migration became the primary mechanism for keeping the population of Okinawa at a sustainable level. During the early years of migration, around the turn of last century, people were driven out of Okinawa by conditions of abject poverty and were regarded as “kimin,” or deserters. In contrast, today they have become important catalysts for exchange between Okinawa and the rest of the world. It was only quite recently, however, that they actively organized themselves to enhance their “Uchinanchu identity” beyond national boundaries.

It is interesting to note that the third and fourth generations of emigrants from Okinawa are increasingly more concerned and more appreciative of their ancestors’ culture than their parents and grandparents. This is particularly so when the cultural value and lifestyle of Okinawa is highly appreciated by the world community. This coincides with Lowenthal’s observations on emigrant communities:

Networks of obligation with homelands may persist for generations, as Cook Islanders in New Zealand and Paupans in Australia show. Diaspora communities like Guamanians in California and West Indians in Toronto retain or replicate so much island culture they can be said to replenish rather than diminish the home society. Indeed, emigrants whose education and economic success foster self-awareness assert their land identity more strongly in exile than those at home (Lowenthal, 1998:14).

Yuimaru is an Okinawan dialect that means “reciprocity.” It is the Okinawan concept that is rooted in old work-sharing practices where all villagers cooperated to help each other with financing, planting, constructing houses and irrigations, and harvesting crops. Yuimaru spirit is still vividly alive in Okinawa in various festivals, mutual finance system called moai and community activities. This is a social “safety net” system to prevent individuals or communities from collapsing. The value of yuimaru is also re-evaluated as globalization, or Americanization of lifestyles, a symbol of cut-throat competition and rigid individualism, prevails and affecting adversely Okinawa’s lifestyles of health and sustainability (LOHAS). Okinawa is now a booming tourist resort for mainland Japan. A typical mainlander, who used to blame an Okinawan for his or her backwardness, and easygoing attitude towards work, is reported to say that “every nation and citizen can live in peace. I am very proud of this original Okinawan idea and I would like to diffuse this “yuimaru mind” all over the world.

Okinawa’s comparatively easygoing and time-loose lifestyle is also gaining popularity to ease the various stress and pressures arising from workplaces and complex human relations. “Uchina time” (unpunctual Okinawan time), which was almost totally replaced by “Yamato time” (Japanese time) a long time ago, has also been gradually revived because of a general acceptance of “slow-life” and healing-oriented lifestyle reflecting Japan’s rapidly aging society.

Japanese society is, no doubt, ailing and aging. Japan’s international status has been weakening in the 21st century due largely to its declining relative economic power, aging population, and above all its inward-looking culture and politics. Japan is the least open society among the OECD countries. This character is deeply rooted in its culture and in its racially homogeneous peoples who tend to reject cross-cultures. Despite more than a century of assimilation and Okinawa’s painstaking efforts to be a part of Japan, “Japanese are not capable of accepting Okinawans as full-fledged members of the national family…” (Smits, 1999:151).

As we have seen, however, there are an increasing number of mainlanders who favorably evaluate the Okinawan lifestyle and wish to live in Okinawa in recent years. There has been an interesting phenomenon in population flows in recent years. The indigenous population of Okinawa’s outlying small islands have continuously emigrated to neighboring larger islands, while an increasing number of Japanese mainlanders have been attracted to the leisurely “island lifestyle.” If such a trend in population dynamics continues, we may see the entire population of these islands being replaced by mainlanders in the future. Nobody can predict the socioeconomic impacts of these cultural dynamics (Kakazu, 2006).

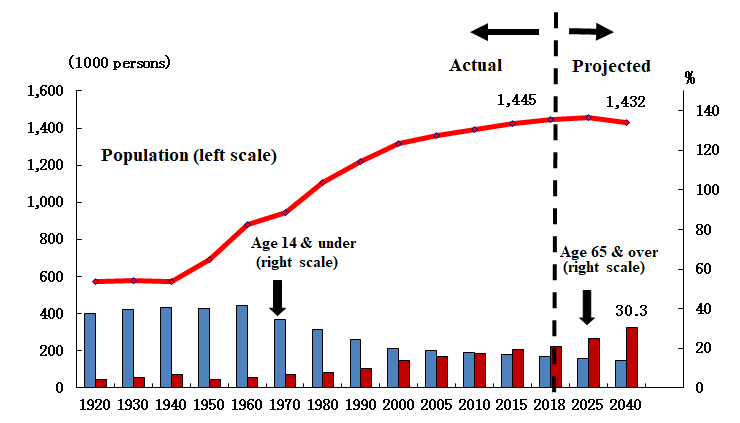

Okinawa’s champuru culture represents not only cultural diversity which is a norm of international society, particularly in the Asia-Pacific, but also it empowers the local people through healthy lifestyle and warm yuimaru spirits. Okinawa is the only local prefecture in Japan whose population is still growing. There is a no nonsensical joke that Okinawans will be the last Japanese to survive in the 25th century if the current depopulation on the mainland continues.

The strength of champuru culture is its resilience and flexibility towards external flexibility. This strength has probably been nourished through its enduring history of ambivalence, war and colonial rule. At the same time, the champuru culture has bred a dependency syndrome culturally as well as economically. Okinawa will play a very important role in contributing to Japan’s future development in the age of Asia-Pacific. I have found an influential Western “Okinawanologist” who argues that:

Japanese history could only be understood in light of the history of Ryukyu…it must not be understood as a ‘minority’ on an ethnical, cultural, or any other sense: Ryukyu and its culture as well as its language form one of two main equal pillars of support, standing side by side, which hold up the Japanese culture. Only the realization of this fact makes it possible to appreciate the immensely rich diversity of Japanese culture. (Kreiner, 2001:15)

Although Okinawan champuru culture is Japan’s “marginal culture in a marginal or peripheral region,” it does contain a spirit of reciprocity or mutual help and sustainability which are also common cultural characteristics in Asia. This is why Asian visitors to Okinawa feel at home when they have discovered the Okinawan mottos: icharibachode (once we meet, we are like brothers and sisters), chimugurisan (someone’s pain is my pain), yuimaru (reciprocity), and nuchidotakara (life is the most precious thing in the world)—developed out of a long, dynamic process of island life. This rich, diverse cultural heritage is today appreciated within and beyond Okinawa, particularly in mainland Japan. It may be appropriate to quote Professor Haruo Misumi: “Okinawa is a place where its art culture has surpassed that of Japan and has grown to the scale encompassing the whole of Asia” (Misumi, undated:1).

A Shangri-la, the land of happy immortals sought by many Chinese as well as European emperors, portrayed in James Hilton’s best-selling book Lost Horizon. Willcox, Willcox and Suzuki used Shangri-la as a metaphor based on a painstaking investigation into Okinawan longevity:

There are more than 400 centenarians in a population of 1.3 million—about 34 per hundred thousand—many of them still healthy, active, and living independently. In the United States, there are only five to ten centenarians per hundred thousand—a huge difference—and most older Americans are in far less robust health. (Willcox, Willcox and Suzuki:1)

Okinawans’ longevity is, no doubt, the product of a complex combination of climate, culture, closely-knit social organizations, food and lifestyle as is shown in the following chart. The above authors have discovered that food culture is particularly important for the healthy life. The most popular Okinawan dishes are the various champuru recipes, notably goya (bitter gourd) champuru. Goya and its products have become best-selling health foods in Japan in recent years.

Okinawa’s Sustainable Economic Development

Characteristics of Island Economies

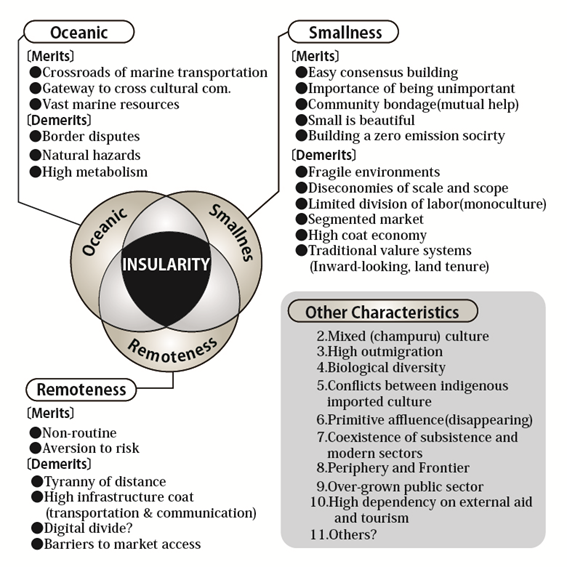

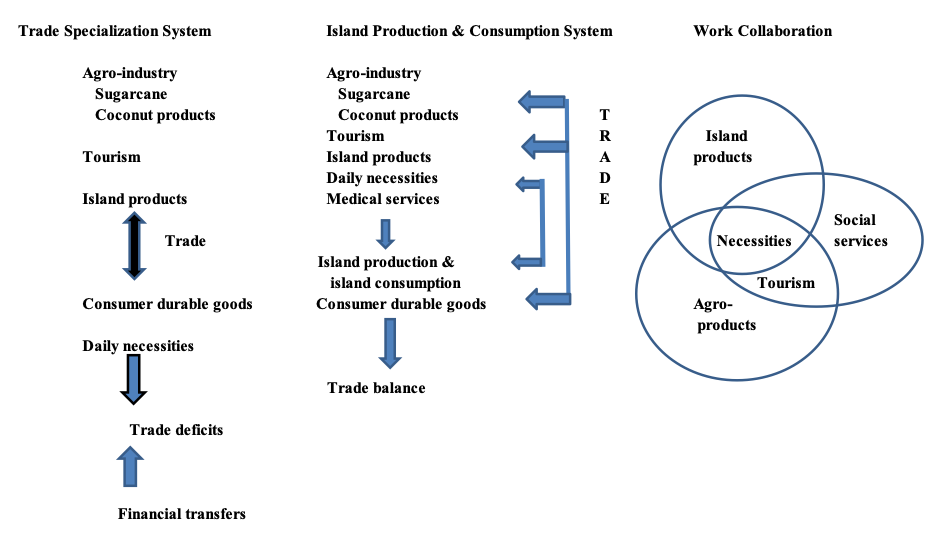

Like many other small island economies, Okinawa’s economy possesses general characteristics that have presented challenges for its economic development: (a) specialized rather than diversified economic activities; (b) a small domestic market; (c) reliance on a limited number of primary products and tourism for export earnings and simultaneous dependency on imports of consumer and capital goods; (d) chronic trade balance deficits; (e) diseconomies of scale; (f) high transportation costs; (g) rising population pressure on a small arable land area, and; (h) a heavy reliance on government expenditures and activities as a major source of income and employment. Unique socio-politico-economic development problems will arise when the “island” is associated with its smallness, isolation and its location at international borders (Kakazu, 1994). The general characteristics, merits and demerits of small islands from the standpoints of socioeconomic development can be summarized in Figure 6.

Although it is true that a small island economy intrinsically endowed with demerits than its merits in conducting sustainable development, there are several characteristics which can be considered as economically advantageous in comparison with larger economies as shown in the figure. Among them are being unimportant in external commercial policy and having more unified national markets, greater flexibility, and perhaps greater potential social cohesion. Prasad (2004) vividly demonstrated that “the importance of being unimportant“ has allowed many small economies to pursue distinctively national policies seeking favorable deals which concede special advantages such as sales of passports (Kiribati, Samoa, FSM), internet domain names (Tuvalu), shipping registries (Vanuatu), fishing rights (Pacific islands), postage stamps (Tuvalu) and military bases (Okinawa, Palau, Marshall Islands). The South Pacific countries also “sell their sovereignty” to other countries to finance their budget or to get foreign aid. The huge expanse of ocean surrounding these island masses may also provide rich marine resources and natural energy which can be tapped for future economic development, as highlighted by the recent dispute regarding Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands and nearby undersea oil and natural gas resources (Kakazu, 2016). Okinawa, for example, is making extensive use of ocean resources through aquaculture, the utilization of deep-sea water for various health products and marine or “blue” tourism such as whale-watching and scuba diving.

Small islands may also have comparative advantages in environment-friendly economic activities such as recycling, reusing, and reducing the environmental hazards. Small islands could become model cases of zero-emission societies. Followings are some lessons small island societies would learn from Okinawa’s experiences of sustainable development.

Population and Employment

Amid declining trend of Japanese population, Okinawa's population increased from 970,000 in 1972 , when Okinawa reverted to Japan, to about 1,445 thousand in 2018 (Figure 7). Okinawa is the only prefecture, which has more than doubled its population since World War II.

Okinawa has experienced very unique patterns of population growth in recent years. Social change turned from negative to positive after 2009. This means that Okinawa has attracted more in-migration, mostly mainlanders than its out-migration. This is particularly true after the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake which occurred on March 11, 2011 in Japan’s northeastern region. Okinawa’s population, however, is projected to peak out in 2015 with 1,458 thousand.

A rapid population increase after reversion, accompanied by a proportionally larger labor force, has generated a continuous labor surplus in Okinawa's job market. Over the post-reversion period (from1972 to the present), the labor force has increased by 2.3% annually. Although local employment has also increased by 2% annually during the period, it has not been enough to absorb the increased labor force. Consequently, the jobless rate jumped from 3% in 1972 to about 5%-9% in recent years, which are about twice as high as Japan proper. The creation of jobs has been the most important economic and political agenda in Okinawa since reversion.

Okinawa's unemployment structure is unique nationally, in the sense that young people (those under age 30) account for 36.2% of the total number of unemployed compared with 28.2% in Japan proper. Young unemployed people have largely been supported by pooled family incomes and by an age-old Yuimaru, or mutual help system. This explains why there is little social unrest despite a high, persistent unemployment rate. There are two types of the unemployed. One type is “the voluntary unemployed,” who resigned jobs voluntarily, have accounted for nearly 60% of the unemployed workers in recent years. This type of self-unemployment is mainly attributable to mismatches between the job seekers or demand and job offers or supply in Okinawa’s labor market. Although tourism is the most promising and growth-oriented industry in Okinawa, the educated younger generation tends to look down on the industry due not only to its relatively low pay, hard work, but also to its low social status compared with the public service sector. This is a general phenomenon in developing island societies where the public service sector dominates economic activities.

In light of weakening family ties and social safety net, also known as “social capital,” growing competition and an aging population, unemployment within Okinawan society will become increasingly more difficult to manage in the future. There is plenty of evidence that unemployment has many far-reaching effects other than loss of income, including psychological harm, loss of work motivation, skill and self-confidence, increase in ailments and morbidity, disruption of family relations and social life, the hardening of social exclusion and gender asymmetries.

Economic Performance and Living Standards

Okinawa's real gross Prefectural product (GPP) has grown on average by 4.2% annually over the post-reversion period (1972-2015). At the same time, however, the growth rate has declined continuously from 9.9% in the 1970s to 3.6% in the 1980s, 1.2% in the 1990s and 1.1% in the first decade of the 21st century. Although Okinawa’s GPP performed better than Japan proper in the post-reversion period, growth rates roughly synchronized with the national average, particularly after the third and fourth development plans.

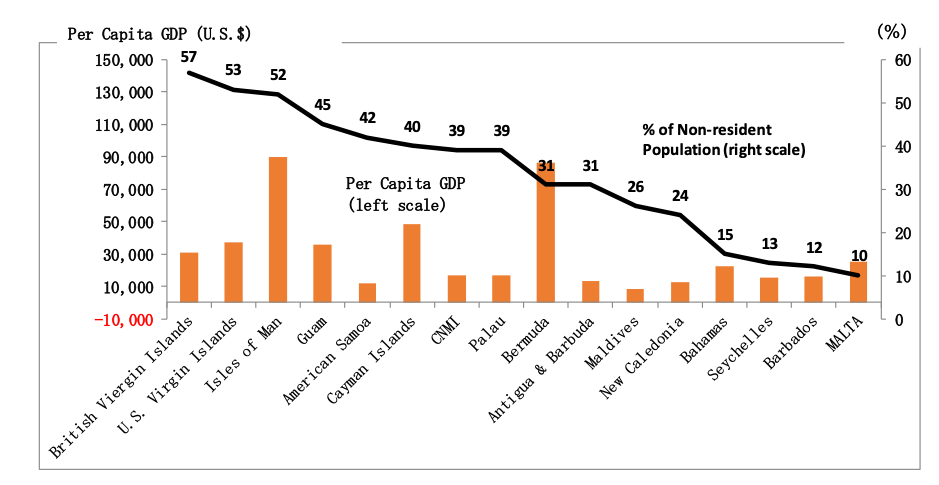

Okinawa’s relatively higher economic growth than Japan proper, particularly during the 1980s, contributed to narrowing the gap (kakusa zessei) in living standards between the Japanese mainland and Okinawa. Okinawa's per capita income (PCI) increased from US$1,877 or 58% of the national Japanese average in 1972, to US$25,000, or 72% of the national average in 2015. The size of the population or GPP is not directly related to the level of per capita income (Figure 8).

It is interesting to note that per capita incomes of “micro” and remote islands are higher than the average per capita income of Okinawa Prefecture and Naha City, the largest municipality in Okinawa by any measures. Kitadaio and Minamidaito islands with population about 1,000 recorded the highest per capita income among Okinawa’s municipalities. Their main industry is large-scale agriculture (sugarcane). The other high-income islands are sustained by tourism and tourism-related industries which are discussed later.

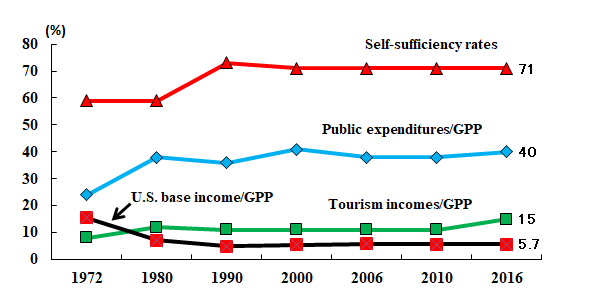

There are three main engines that have contributed to Okinawa’s post-reversion growth rates (Figure 9). Public expenditure is the single most important item, accounting for 30-40% of Okinawa’s GPP in recent years, followed by income generated from tourism (10-11%), and U.S. military base expenditure (5%). Immediately after reversion, public expenditure, mostly in the form of fiscal transfers from the Japanese government, replaced U.S. military expenditures within the local economy as the main engine of growth. The amount of public expenditure, however, has declined in recent years owning to Japan’s increasing public debt. Therefore, public expenditure is not expected to play as an engine of Okinawa’s future growth.

The second important economic growth factor is the tourism industry. The number of visitors to Okinawa has increased more than 15-fold, from 440,000 to over 8 million during the period 1972-2016, which constitutes an annual increase of 5% compared to a GPP growth rate of 2.5% as is fully discussed later.

The relative importance of U.S. military base expenditures, including the wages of civilian employees, base land leases, and base-related expenditures by U.S. forces and their dependents for local products and services, has declined from 15.5% of GPP in 1972 to about 5% in recent years. The U.S. bases, however, still generate 200 billion yen annually, and provide employment for about 9,000 local people. There are always more local job applicants for base employment than jobs available, owing mainly to the lack of stable and attractive job opportunities in the local market. Beyond that, a large chunk of Japanese central government transfers is directly and indirectly related to the maintenance of bases.

Okinawa’s overall self-sufficiency rates defined in the footnote of the above figure improved continuously after reversion until the 1980’s, from about 60% to over 70% in recent years, reflecting diversification and the expansion of the economy. After the collapse of the economic bubble and the ensuing globalization-cum stagnation in the 1990s, sufficiency rates have flattened out. Since the mid-2000s, however, self-sufficiency rates have improved gradually supported by labor-intensive service industry, notably local-oriented tourism, construction activities and ICT-related industries. It should be noted, however, that these domestic supply-oriented industries have expanded as a result of the increased external receipts from central government, tourism and U.S. military expenditures. An increase in the self-sufficiency rate does not necessarily mean self-sustainable development because it can be increased by spending through external borrowing.

The average life expectancy of women in Okinawa is eighty-six years, one of the highest in the world. There are many explanations offered for this longevity, including food, water, climate, easy-going work habits, communalism, and even DNA. However, an in-depth study has not yet been conducted. In recent years Okinawa’s lifestyles of health and sustainability (LOHAS) have attracted retirees from the mainland who wish to spend the rest of their lives in Okinawa.

Not all has been rosy, of course. High economic growth has inevitably been accompanied by environmental degradation, notably air and water pollution, as well as soil erosion that require comprehensive study and the adoption of serious measures. The widening income gap among households as measured by the Gini index is also of concern. A sense of inequality among islanders has been intensifying in recent years. Although the jobless rate improved substantially in recent years, the number of Okinawa’s households on the welfare assistance program has risen sharply in recent years reflecting the increasing number of working poor. More than 40% of full-time workers and about 60% of part-time workers earned less than four million yen and one million yen, respectively, in 2014.

Industrial Structure

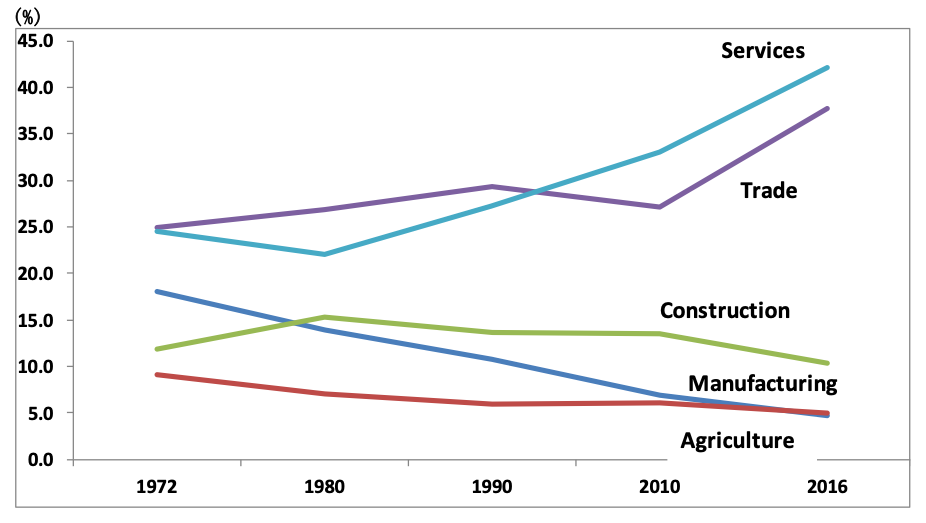

The structure of the Okinawan economy is very similar to that of Hawaii. In both cases, the service industry dominates economic activities. Agriculture, which was the dominant industry during the 1950s, now accounts for only 5.2% in terms of labor force and 1.8% in terms of income (Figure 10). Empirical law discovered by Kuzunets (1965) and others suggests that the agricultural sector tends to generate low incomes in part because of the low-income elasticity of its products compared to those of other sectors; as the cost of producing farm products falls with technological progress, prices tend to fall as well. Moreover, the skills required for traditional agricultural production are fewer and do not demand extensive higher education. Okinawa has followed this pattern more than any of Japan’s other prefectures.

Although Okinawa's agriculture has been diversifying away from traditional sugarcane and pineapple cultivation to flowers and vegetables, such as chrysanthemums, orchids and goya (bitter melon), and tropical fruits such as mangoes, citrus and dragon fruit, the relative contribution to Okinawa's GPP may continue to decline in the future because of increasing international competition, stagnated productivity gains, and aging farm workers.

Okinawa's average monthly wage per manufacturing worker, for example, was US$2,706 for 2012, which was about twice as high as that in Taiwan and Hong Kong, where per worker productivity is higher than in Okinawa. That is to say, the unit labor cost in Okinawa (wage per worker/per worker productivity), which determines international competitiveness, is more than three times higher than those countries mentioned.

Reflecting Okinawa's high cost economic structure, particularly in the manufacturing sector, the income share in the manufacturing sector has declined sharply from 10.9% in 1972 to 4.5% in 2012 which is very low compared with that of Japan proper (18%), Taiwan (27%) and Singapore (15%). It is a historical fact, for any self-sustaining economy, both at the national and regional scales that the income share (GPP) of the manufacturing sector rises to about 30%, and then declines as demand shifts to service-related activities (Kakazu, 2015a). In the case of Okinawa, however, the share never rose above 11% in the past, owing to the fragile industrial structure, coupled with a massive inflow of demand for construction and service-related activities including tourism. There is a consensus amongst policy makers and researchers that the development of a large-scale manufacturing industry in Okinawa is simply not viable, either now or in the future. Okinawa’s island markets are very small, fragmented and far away from major markets; wage and rental rates are far higher than those in neighboring Asian countries; and the level of human resources and technology development are low. At the same time, there is a consensus among policy makers that local resource-oriented, niche industries such as food, particularly health food, tropical fruits and flowers, crafts and tourism-related products have the potential for further development. Moreover, these, agro-products are gradually capturing a niche in the mainland and Asian markets as discussed later.

Trade Imbalance and Sources of External Finance

As a direct result of the narrow range of their resource base and production conditions, small island economies depend upon a few primary products for their export earnings, while importing a wide range of consumer goods as well as capital goods. As a result, most of the small island economies, including Okinawa, have been suffering from chronic deficits in trade balances which have largely been financed by growing inflows of remittances, fiscal transfers or ODA, including military expenditure, and tourism incomes. Remittances by out-migrated workers are the single most important source of national income for many small island economies. Dependency on official transfers, which have contributed to enlarge the public sector and bureaucracy, has been gradually replaced in its importance by tourism incomes in recent years. These trade and finance characteristics are vestiges of colonial heritage and policies. Bertram and Watters characterized these island economies as “MIRAB” economies, where MIgration, Remittance, Aid and resultant urban Bureaucracy become central to the socioeconomic system (Bertram and Watters, 1985). In view of the increasing importance of the tourism industry in these islands, MIRAB should be renamed as MIRABT, where T stands for tourism.

Okinawa also depended heavily on remittances of migrated workers to finance its trade deficits before World War II. The sources to finance the deficits have changed dramatically after the war. The U.S. military expenditure was the most important source of foreign earnings up to Okinawa’s reversion to Japan. After the reversion, however, fiscal transfers from the Japanese government financed about 50% of Okinawa's total external payments, including imports, followed by receipts from exports (37%), tourism (19%) and U.S. base-related expenditures (10%).

A heavy dependency on fiscal expenditures, which are mainly financed by public debts, has been a global issue, particularly after the European sovereign debt crises triggered by Greece. Japan’s cumulated public debt was about 246% of its GDP or $14 trillion in the same year, the largest percentage of any nation in the world. We all know that a continuing accumulation of public debt is not sustainable because it must be paid by future generations by raising taxes, cutting public expenditures or creating hyperinflation by printing more money unless continuous real economic growth is not realized. Okinawa must reduce its high dependency on fiscal expenditure for its sustainable development.

Entrepreneurship and Human Resources development

Despite the various incentives and preferential measures to promote industry over nearly four decades of implementing long-term economic development plans since reversion, the Okinawan economy is still on the long way towards achieving self-reliant or self-sustainable development financing its mounting trade deficits and reducing the high unemployment rate through internally generated economic growth. Economists and policy makers have persistently pointed to the lack of entrepreneurship, that is, the lack of initiative, well-conceived plans, actions, self-assessment and calculated risk-taking on the part of the private business sector. It can only be an idle dream to talk about sustainable development for Okinawa without strategically nurturing entrepreneurs who must play a vital role in this age of mega-competition. Nurturing entrepreneurship is profoundly linked to human resource development. The subject has been a hot topic for many years because Okinawa, with limited natural resource endowments and with small markets, must pursue its development efforts through effective utilization of its relatively abundant human resources. Compared to Japan proper, where the population started to decline in 2008, Okinawa's population is expected to increase until 2025. This effectively means that Okinawa will be a position to supply portions of the labor force for Japan's future development provided, of course, that this labor supply is well-educated and skillfully trained.

One worrying aspect of Okinawa's human resource development, however, is the close to stagnant trend of college enrollment rates (percentage of college and university enrollments against the number of high school graduates) which declined from 21.3% in 1972 to 19.1% in 1980. Although the enrollment rate picked up to 37.3% in 2015, it was much lower than Japan's 51.5%, itself a remarkable improvement from 29% in 1972. Although household affordability for higher education in terms of per capita income increased by more than 5 times during the period, two important reasons for this stagnant trend of college enrollments can be isolated. One is increased cost of higher education, particularly in Okinawa prefecture where seven local universities and two junior colleges accommodate about a half of applicants; the remainder must leave for more expensive mainland colleges.

A recent development, however, is encouraging for Okinawa’s human resources development in science and technology. The Okinawa National College of Technology (ONCT), a professional training college about machinery, information, media and bioresources technologies, was established in 2002 in Nago City. Okinawa was the only prefecture in Japan where such national polytechnic college did not exist until 2002. Another recent development is the establishment of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) which inaugurated in November 2011. The OIST, based on the five basic concepts, namely “Best in the world,” “International,” “Flexible,” “Global network,” and “Collaboration with industry,” will become a leading intellectual hub in Okinawa for the Asia-Pacific region in the fields of bioscience, chemistry, computer and information science, engineering, mathematics and physics. The OIST is totally financed by the Japanese government for at least next ten years. After that it has to earn its operational funds based on its own research and educational reputation and achievements.

Various enterprise incentive systems for improving the quality of human resources are available, including tax breaks, investment tax credit, tax withholding for “Engel” investors, low interest rates, loan guarantee, subsidies for rental facilities, on-the-job training, and wages are available for new venture-type businesses. The Okinawa Employment Promotion Center, for example, subsidies one-third of wages for up to three professional workers for one year.

Diversification of Okinawa’s Agriculture

Food security is particularly important for a small, isolated island economy where a stable supply of food is often interrupted by natural disasters such as drought, typhoons, tsunami and unexpected environmental changes. Quite often, for these small islands, domestic food supply is the last resort for survival when natural disasters occur. This is particularly true for small Pacific islands where islands are fragmented and located far from their major markets. Ironically, however, domestic food supply in these small islands has been neglected for a long time. As is fully discussed later, subsistence agriculture, which has provided basic necessity of foods to indigenous islanders, has been rapidly disappearing in all Pacific islands, including Okinawa. Increasing cheap and subsidized food imports at the expense of traditional food supply have been major issues in terms of food security and nutritional standpoints (Kakazu, 2012a).

Agriculture, which supplies basic foods, was the dominant industry in Okinawa in 1950s, now accounts for 1.2% of Okinawa’s gross Prefectural product (GPP) and 4.5% of total employment in 2014. The importance of agriculture tends to diminish as per capita income rises. This is because the agriculture sector tends to generate low incomes in part because of the low-income elasticities of its products compared to those of other sectors—as the cost of producing farm products fall with technological progress, prices tend to fall. Moreover, the skills required for traditional agricultural production are less highly developed and do not demand extensive education.

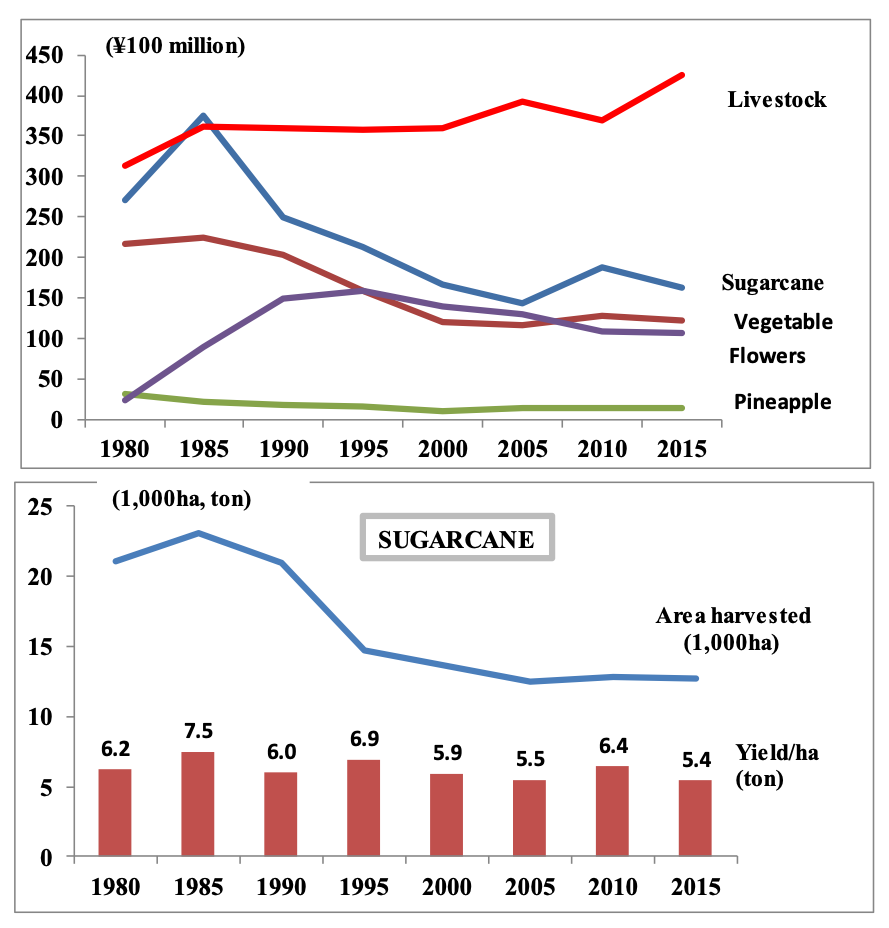

Of Okinawa’s agro-resources, sugarcane has been the most important cash crop, accounting for about 20% of all farm incomes and 50% of cultivated land. Incomes from sugarcane production, however, have declined significantly in recent years as a result of stagnant prices and productivity as well as increased international competition (Figure 11).

The farm gate price of sugarcane, on average, was 21,923 yen ($250) per ton for the 2014 crop year, which was about four times higher than the price per ton in Thailand. Moreover, the per-hectare planted land productivity of sugarcane has remained unchanged for decades. Okinawa's sugar industry has only been surviving through the government’s price support programs. These indicators demonstrate that Okinawa’s sugarcane cultivation will be diminished in the future, even under heavy government subsidy. Because of the declining trend of sugarcane cultivation, Okinawa’s uncultivated farm land has been expanding, particularly on Okinawa Island. Sugarcane, however, is the only cash product in many small, remote islands. Therefore, compensation scheme, such as direct income provision, may be needed to obtain a consensus for pursuing Japan’s possible entry into the TPP.

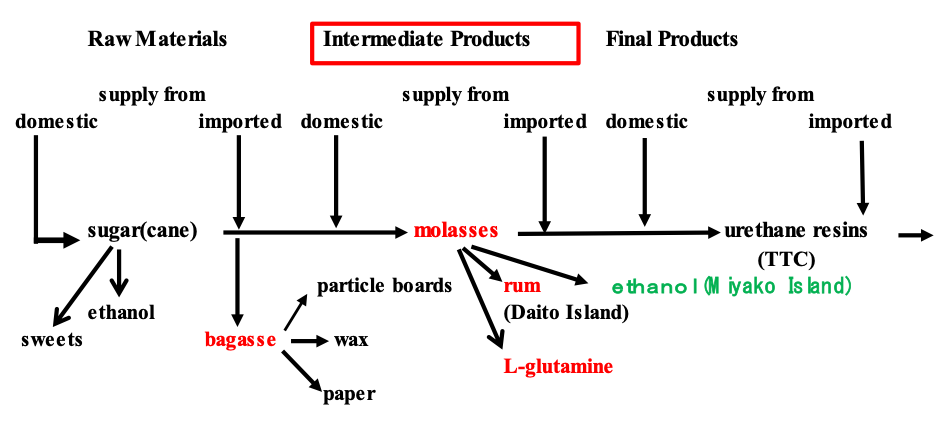

Agro-industry

Local resource-oriented agro-industry or “the sixth industry,” which is a concept of a consolidated package of agriculture, processing agricultural products and sales, is one promising area. Okinawa’s traditional, declining sugarcane has been revalued in recent years because of its high-valued alternative use (Figure 12). Sugar-related inputs such as molasses and bagasse, which in turn can be transformed into urethane resins, particle boards, rum, wax, paper products, sweets and recently ethanol, have been pursued at many remote islands and local research institutes. The urethane products, which were developed by the Tropical Technology Center (TTC) in Okinawa, have an enormous potential for a wide-range of products from pet bottles to home and industrial appliances. These products are decomposable (biodegradable) and therefore can be substituted for environmentally hazardous plastic products if quality and prices are reasonably acceptable to users and consumers.

Miyako Island, which is a major producer of sugarcane, has been designated by the national government to produce ethanol for fuel (Kakazu, 2015a). Islanders are hoping to substitute this renewable and environmentally friendly fuel for gasoline in the future. L-glutamine can also be produced from sugar molasses. Dr. Yutaka Niihara, a hematologist and a former professor at the UCLA Medical School, patented L-glutamine therapy for the treatment of sickle cell disease. It is also used in dietary supplements and is claimed to be useful for a variety of different conditions such as depression, anxiety and insomnia. Pineapple production, another important traditional cash crop in Okinawa, has declined more rapidly than sugarcane for similar reasons. Only fresh pineapple and pineapple wine are holding their own, and this as a result of tourists' consumption. It is an urgent task for the local government to diversify from sugarcane-centered monoculture agriculture into high value-added agro-industry and other diversified cash crops such as flowers, health foods, tropical fruits, vegetables and livestock.

One of promising and emerging agro-industries is coffee. It is not well-known that there are more than thirty coffee growers in Okinawa covering almost all major islands. Many people believe that coffee plants are grown in the “Coffee Belt” which is the area between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. Okinawa is located the northern edge of the Tropics of Cancer. There is already a coffee company named “Nago Coffee” which has been producing and selling various Okinawa brand coffee products including specialty coffee beans, roasting machine, thresher, bread, royal jelly, jam, sweets, tea, coffee cups, etc. Nago Coffee has also a plan to manage café shops. Coffee is location specific. Its flavor and taste differ vastly from region to region, even from farm to farm within any given region. Therefore, Okinawa with diversified island regions has a great potential to develop island specific brand coffee. Coffee plantation will make a good use of Okinawa’s uncultivated farmland which has been expanding in recent years. For the successful development of these resource-based products, several problems must be resolved. One important factor is the size of the market, which in turn, determines the cost of production. As can be typically seen in the case of integrated circuits, the initial unit cost of production is very high. But as the market expands, the cost is reduced approximately to one-half within a decade. Products such as urethane resins require a large segment of the market to compete with plastic products.

The second important consideration is “cost escalation,” which will quite often accompany when local resources are used as raw materials or intermediate inputs. The price of Okinawan sugar, for example, is about four times higher than the international price because of government protection. High sugar cost means high costs for molasses and consequently to produce urethane resins. Here the producers of urethane resins face a dilemma because they are obliged to import molasses in order to compete in the international market.

The third important consideration is a stable supply of raw and intermediate materials with competitive price and quality standards. It's easier said than done. Despite growing uncultivated agricultural lands, Okinawa has supplied only a 40% of its vegetable demand, the rest has been imported due partly to occasional typhoon visits.

It is important to realize that to diversify local products toward more value-added products, domestically produced raw materials must be available at international prices. Unless there are incentives such as subsidies and taxes, which will compensate for the cost disadvantage during the initial stages of production, an Okinawan producer of urethane resins would always choose imported molasses over the costly local alternative. Okinawa’s molasses has price competitiveness now simply because there is not much demand for them.

Health Foods as a Growing Agro-industry

Okinawa is fast becoming a brand name connoting “health and longevity.” Okinawa’s longevity is the product of a complex combination of climate, culture, closely-knit social organizations, foods, and lifestyles. Greek physician Hippocrates said, “let food be your medicine,” so food is the most important factor influencing longevity. “There is certainly strong evidence that some of the compounds in the herbs and medicinal plants regularly consumed by Okinawans have powerful antioxidant and positive hormonal effects, and few ill effects have been associated with using them as foods, condiments, spices, teas, or home remedies.“ (Willcox, et al 2001:5).

Okinawans are accustomed to consuming less salty, mineral-rich foods than mainland Japanese. Okinawa has developed and marketed various health foods such as turmeric (ukon), bitter melon (goya or nigauri) products, naturally processed salt, sea vegetable products (mozuku, umibudo), ostrich meat, and various deep-sea water products to name a few well-known examples (Figure 13). Sales of these health foods have jumped from ¥2 billion in 1995 to over ¥20 billion in 2004 but declined thereafter due largely to intense keen competition. The sales of health foods exceeded the sales of sugar, the most important agricultural cash crop in Okinawa for many years. Sales of health foods have been buoyed by increased attention to Okinawa’s world-renowned longevity, but also by enhanced health-consciousness among Japan’s aging population.

Health foods possess comparative advantages in the uniqueness of resource use and technology which can be developed on a small-scale basis. Furthermore, these products usually require more local inputs, including raw materials and labor, than conventional trading products. The OPG has been promoting “one island, one health food” because each island has its unique medicinal plants and herbs. Of course, there has been keen competition in recent years among health food producers.

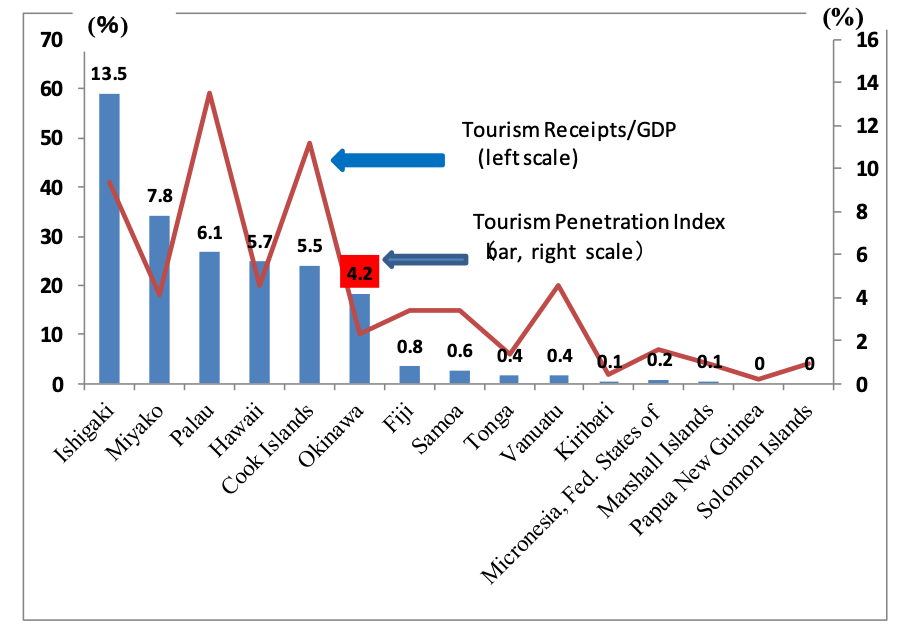

Sustainable Island Tourism

The tourism industry is the main engine to sustain both population and standards of living on small, remote islands. as seen in the following tourism penetration index (Figure 14).

The Roles of Tourism for Small Island Economies

From a global perspective, the growth of tourism has been particularly impressive for small Pacific islands such as Okinawa, Hawaii, Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Within these island economies, external receipts from tourism accounted for about 20% in Okinawa, 60% in Hawaii and CNMI of their respective total current external receipts for recent years. For CNMI, about 70% of the island's economic activities depend on tourism. These small islands have transformed rapidly into tourism dependent economies because: (1) they generally lack any natural resources exploitable for export earnings; (2) their market sizes are too small to develop viable manufacturing industry; (3) tourism-related industries are usually small-scale and labor-intensive; (4) they are endowed with marine resources, particularly beautiful beaches; (5) these islands are either part of, or surrounded by, rich countries such as the United States, Japan and Australia which have well organized transportation networks; (6) their tropical or semi tropical climatic and cultural conditions are complementary with those of rich countries; and (7) these island communities have maintained internal political stability and warm hospitality to visitors (Kakazu, 2011).

Tourists' expenditures are recorded as service receipts in the external balance of payment statistics. Tourism incomes, in effect, are equivalent to exports of not only services but also goods which are sold to non resident tourists. Sales to tourists are directly reflected in local production or imports of goods including agriculture and manufacturing. For small island economies, tourism needs to be conceptualized as a composite industry, not merely a service industry.

In Okinawa, for example, aside from conventional tourism industry such as hotel, travel agents, transportation, souvenirs and travel guides, the industry is deeply and extensively related to local cultures, meals, production sectors, information and communication technology (ICT), various entertainments and sports, transportation, marketing and promotional activities, conventions and preservation of natural and cultural assets. An important difference between commodity exports and service exports through tourism activities is that the former is consumed or stocked in the imported region, while the latter are inseparable from the exporting region where the services are rendered. In this sense, tourism is a package of economic as well as non economic factors. In any country, tourists are mostly welcomed not only because of the income and employment they generate, but also because they are regarded as “cultural catalysts.” Tourism is well-recognized as a peace industry. No country or region has ever adopted a policy to reject genuine tourists unless they are hostile or detrimental to host countries. As we have witnessed in recent years, tourists are most sensitive to their own security. Recent terrorist attacks on NYC (September 11, 2001) and Bali (October 2002), the outbreak of SARS, avian flu and tsunami disaster all scared off potential visitors in America and the Asia-Pacific.

How to sustain Okinawa’s tourism industry?

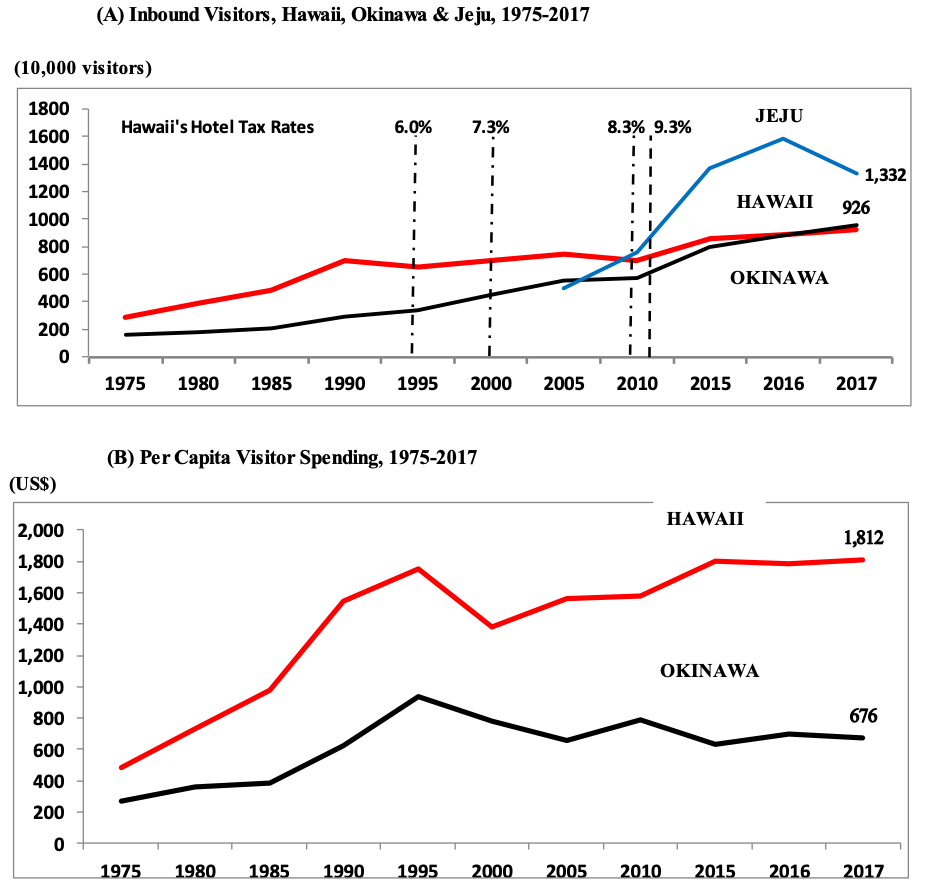

There is no doubt that the visitor industry is Okinawa's most competitive and therefore prospective industry on both domestic and international scales. The number of tourists has expanded about sixteen-fold since reversion mainly as a result of private sector initiatives overtaking Hawaii’s in 2017. Jeju’s tourism grew much faster than Okinawa’s (Figure 15A). The industry generated a value-added income of 564 billion yen ($4.5 billion) or 11% of Okinawa's GPP and about less than 100,000 regular jobs for a wide-range of industries in 2015. If we include all the various tourism-related industries, the impact of tourism on Okinawa's economy would be 1.8 times greater than its direct income effect. It is natural and reasonable, therefore, that we project the future course of Okinawa's development as being based on tourism.

Hawaii's tourist industry can be a good model for Okinawa for two reasons. First, Hawaii's location, resource endowments and population size are comparable to Okinawa's. Second, Hawaii has a long history of tourism development. Okinawa's tourism industry needs to diversify vertically through strengthening intra-industry linkages, and horizontally through geographical linkages, including Okinawa's rural areas and cross-border areas such as the Ryukyu archipelagos, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Shanghai and South Korea. Deepening the structure of tourism is the most effective measure to address the recent declining trend of Okinawa's per capita tourists' consumption. An average tourist in Okinawa spent 70% less than that of a tourist in Hawaii in 2015, reflecting Okinawa’s shorter length of stay (9 days vs 4 days), depreciation of the yen and cheaper visitor services than Hawaii’s (Figure 15B).

“Cheap, Near and Short” has been a recent catchphrase to attract mainland tourists to Okinawa. As a result, despite high hotel-room occupancy rates, per room revenue has declined substantially. Such excessive competition by means of price-cutting may eventually damage tourism in Okinawa. Although the Prefectural government optimistically projected that the per capita tourism spending would increase to ¥109,000 in 2014, the actual figure was only ¥70,000 or less than 36% of the target. It should be noted that a ¥10,000 decrease in per capita spending means a loss of 450,000 visitors in terms of total tourism income. This clearly suggests that the tourism industry, which consumes local resources, should not be a mere numbers game. Okinawa is facing the problem of how to upgrade its tourism industry.

Despite the increasing trend of tourism income, the economy could capture only 40% of total tourists spending through the sale of domestic services and goods. The rest leaked out on imports. There are multi-faceted ways to fill the gap between tourists' spending and the economy's capacity to meet the rising demand. According to the latest tourists’ spending survey, the visitors spent more than 20% of their total spending on Okinawan health meals and about 40% of the respondents enjoyed the meals. Health tourism can be further promoted since Okinawa is well-known for its longevity and health foods. In fact, health food products have been growing so rapidly in Japan’s major markets to the point where an “Okinawa brand” could be established.

Okinawa is located between a rich mainland and a fast-developing Asia, but its visitor industry has thus far been tailored for Japanese without much appeal to its Asian neighbors, particularly Taiwan, Hong Kong, South China and Southeast Asia. Foreign visitors from aforementioned region to Okinawa accounted only for less than 10% of the total tourists in recent years. As our Asian neighbors become richer, their lifestyles will also shift to include spending more money on vacations. For them, Okinawa would be an ideal spot. It can be reached within two hours from Hong Kong and just over one hour from both Taiwan and Shanghai. Okinawa would also be an ideal health resort, a place to relax and recuperate. For promoting visitors from Taiwan, South Korea and Hong Kong, where cumbersome visa applications are required, the Japanese government has recently decided to implement “special Okinawa measures” to ease restrictions on immigration formalities, including group application for tourist visas, extension of the visa period from three to five years, abolition of all visa application fees, and allowing a 72-hour visa-free stays anywhere in Okinawa. Visitors from Taiwan, who make up 40% of the total foreign visitors, are treated very favorably under these new regulations.

Carrying Capacity of Island Tourism & the Road Block

According to the World Tourism Organization (WTO), Sustainable Tourism Development (STD) meets the needs of present tourists and host regions while protecting and enhancing opportunity for the future. It is envisaged as leading to management of all resources in such a way that economic, social, and aesthetic needs can be fulfilled while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biological diversity, and life support systems. We must also add that STD should meet the needs and wants of the local host community in terms of improved living standards and quality of life (QOL). The concept should also satisfy the demands of tourists and the tourism industry and continue to attract them in order to meet the first aim; and, safeguard the environmental resource base for tourism. Therefore, “sustainable tourism in its purest sense is an industry which attempts to make a low impact on the environment and local culture, while helping to generate income, employment, and the conservation of local ecosystems. It is responsible tourism which is both ecologically and culturally sensitive” (Kakazu, 2014:216).

Carrying capacity of island tourism has been widely discussed in recent years (Kakazu, 2011). Social carrying capacity (SCC) of tourist sites can be defined as the socially determined maximum number of tourists which are tolerated by local communities. The SCC is usually analyzed both from the residents and tourists’ standpoints.

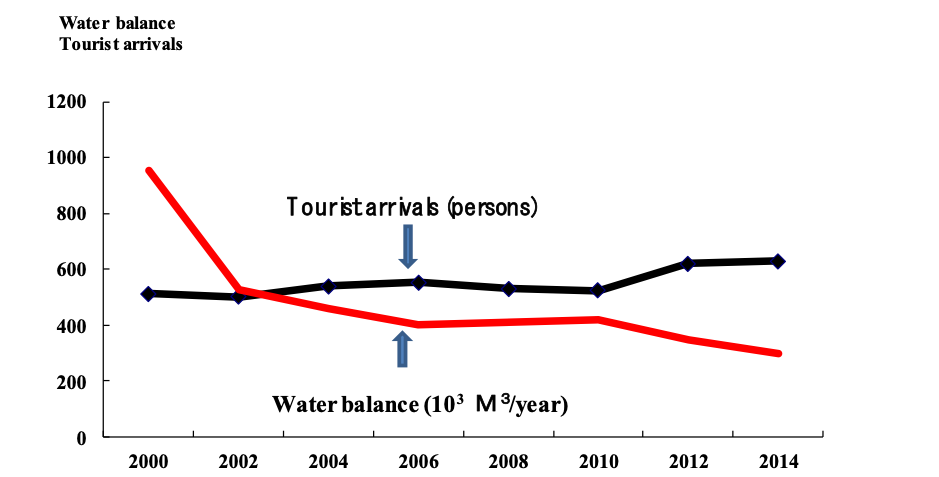

Water supply in terms of quantity and quality has been a serious issue for Okinawa and particularly for small outlying islands. Particularly Miyako Island has been a showcase for occasional water shortage and droughts because of its flat topographical conditions. The island has no river. Thus, groundwater has been a lifeline for about 50,000 islanders. Despite the construction of expensive underground dams, Miyako Island’s water balance has been deteriorating every year due largely to the influx of tourists (Figure 16). It is highly questionable whether the current water supply capacity can meet the future demand (Kakazu, 2012b).

In addition to the increasing demand for water and energy resources as population and tourists increase, the economy’s carrying capacity and environmental disruptions will become serious impediments to future sustainable development. There is already sufficient evidence to suggest that Okinawa’s world-renowned coral reefs are on the verge of extinction due largely to global warming, overfishing and various construction activities. We need to assess whether Okinawa’s small, environmentally fragile islands can sustain their ever-increasing de facto population with their extremely limited capacity of renewable as well as non-renewable resources. Therefore, capacity as well as capability building towards sustainable island development is a crucial issue.

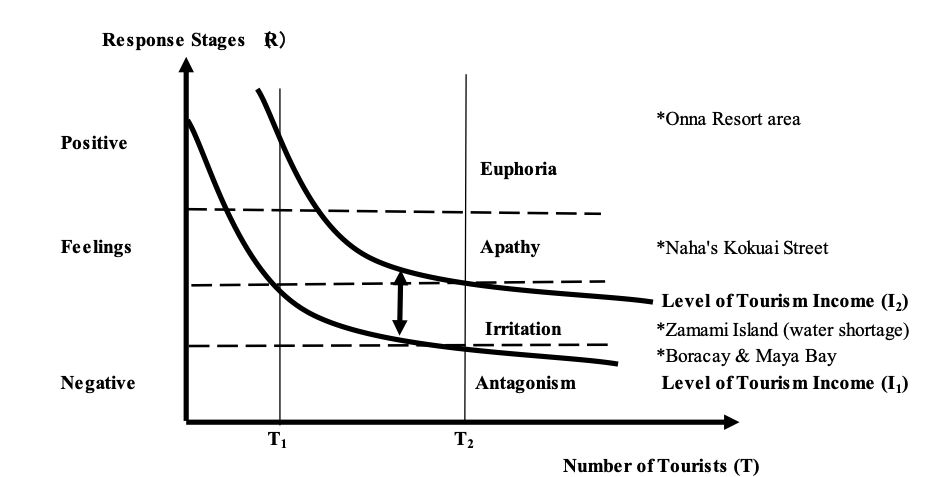

Tourism destination’s the tolerance curve can also be expressed by the so-called “irritation index”, or “Doxey’s Irritation Index taken from its originator (Doxey, 1976). The concept can be depicted in Figure 17.

Euphoria Stage: Tourists are welcome, and hosts are delighted and excited about visitors because they bring income, employment and various vigorous activities. At this stage, tourists are treated as “valuable guests,” and various positive or incentive measures are implemented. Okinawa’s west coast resort area, where population density is relatively low and demand for tourism development is high, will be a typical case of the euphoria stage.

Apathy Stage: When the number of visitors, particularly those repeaters, increases, they are taken for granted, and the hosts become indifferent towards tourists. The hosts will stop to take positive measures to attract more tourists. Kokusai Street in Naha may be reaching this stage.

Irritation Stage: When the number of tourism reaches beyond carrying capacity of the host region, locals get irritated, and sometimes they begin to feel antagonistic towards tourists. Zamami Island, a world-famous diving spot because of its well-known pristine beaches, clean, sparkling water and above all colorful tropical fishes and coral reefs, may be reaching this stage because the island has been suffering from an extreme shortage of drinking water having a surge of tourist scuba-divers in recent years. The island accommodated about 100,000 tourists which are nearly 100 times of the island’s total population. In addition to water shortage, the Zamami local government has been facing a financial crisis to deal with the increasing demand for public services including waste disposals and preserving public facilities.

In contrast to Zamami Island, Taketomi Island, which belongs to the Yaeyama island group, has been considered as Japan’s model case of sustainable tourism (Kakazu, 2015). The island is only 5.42 square kilometers (2.09 sq. mi) with a total population of 351 in 2014. Taketomi is part of Iriomote-Ishigaki National Park, which was established in 1972. Because of its easy access from Ishigaki Island, natural beauty, traditional lifestyle, the island became an extremely popular day-trip destination.