The Modern Colonial Period and the Sea Narrative in the Korean Mythological Work, Samgukyusa (The Retained History of Three Kingdoms): Choi Nam-Seon’s Imagination of the Sea

Sookmyung Women’s University, Korea pyowu@sm.ac.kr

Abstract

Choi Nam-Seon placed critical importance on how the seas were depicted in Korean literary works during the Japanese colonial period. While studying in Japan, Choi majored in geography and history, examining the relationship amongst a nation’s land, history, and culture. Choi’s identification with the child and the sea began ever since he founded the magazine, Sonyeon(Boy), in 1908. In 1927, he reintroduced Samgukyusa (The Retained History of Three Kingdoms) — a representative Korean mythological literary work transported to Japan during the Japanese Invasion of Korea in 1592 — along with a preface. Choi did not merely reintroduce Korea’s native mythological work, but he also went on to directly confront the Tangun Negation Theory and the Monk’s Nonsense Theory claimed by Japan. To go on further, Choi countered the statement that Korea’s geographical shape was one that of a fearful rabbit. Instead, he actively utilized the theory that Korea was shaped like a courageous tiger. Choi approached the marine mythologies within Samgukyusa in two ways. Firstly, he focused on acceptability, in which people from different cultures strove to find a way to live together in peace and harmony through the sea. Secondly, he focused on the marine mythologies which possess the spirit of pioneering – one that endeavored to reach new worlds through the sea.

Keywords

Samgukyusa (The Retained History of Three Kingdoms), Choi Nam-Seon, sea, marine inclusivity, marine challenge

Introduction

During the colonial era in early 20th century, Korea engaged in active combat with Japan in terms not only of politics, but also of culture. Specifically, Japan appropriated geographical knowledge to claim the Korean peninsula’s theory of the peninsula. This was a colonial discourse which equates Korea’s geographical trait — that the peninsula is surrounded by the seas on three sides — with the inferiority of the people of Korea. In addition, Kurakichi Shiratori initiated the discourse that denied Samgukyusa (The Retained History of Three Kingdoms), a representative mythological work of Korea. Shiratori contended that it was a fictitious story, one that could not be believed, for it was written by a Buddhist monk. Furthermore, Imanishi Ryu denied the Tangun mythology, the root of the Korean people and one of the most critical foundations of Samgukyusa. Yukdang Choi Nam-Seon, a modern Korean intellectual, actively began to counter these assertions. In 1906, Choi matriculated in Waseda University, in the School of Secondary Education, majoring in geography and history. As this was his second time to study in Japan, Choi was a colonized subject of Chosun, who experienced two voyages across the seas in the modern era. To cross the sea during the colonial era was a vital experience for the modern intellectual, in the sense that it raised the awareness of his people and the national territory. In other words, Choi was able to objectively understand what it meant to be an individual of a colonized nation. Accordingly, he endeavored to solve the fundamental problem of his colonized nation through a self-awareness of geography and culture. To overcome the negative characteristics claimed by Japan’s theory of the peninsular nation thus became his primary objective.

In order to refute Japan’s colonial discourse, Choi began to actively explore important positive traits of peninsular culture. In direct opposition to Japanese colonial discourse, Choi criticized the claim that the peninsula is the edge of the continent. Instead, he contested that the peninsula is a site which initiates and develops maritime culture, as well as the place of cultural origin and establishment where maritime culture converges and achieves synthesis (Choi Nam-Seon, Haesangdaehansa, 1908). To Choi, in other words, the sea is a space of perfection and authenticity, of liberation where one could open one’s heart to new worlds, of enlightened civilizations, of invigoration and strength, and of endless possibilities (Kim Jin-Yeo, 2006:97). As Choi’s area of persistent interest in mythologies, the sea is an important element to examine. His interest in the sea began in 1908, with “From Sun to Boy” (see Table 1), and continued until “The Sea and the Nation of Chosun” in 1953. In order to confront the Tangun Negation Theory and Monk’s Nonsense Theory in Samgukyusa, Choi reconstituted the memory of the sea in Samgukyusa and thus attempted to establish an autonomous Korean mythology. This paper seeks to investigate how Choi Nam-seon utilizes the Korean mythological work, Samgukyusa, in order to refute Japan’s colonial cultural discourse during the modern era. In particular, this research focuses on the way in which Choi reads maritime imagination within Samgukyusa with the purpose of overcoming the peninsular culture theory.

| Date of Release | Magazine, Press, Newspaper | Literary Works | Type of Work |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1908 | Boy (Magazine) | “From Sun to Boy” | Poem |

| 1908 | Boy (Magazine) | “Cheonmanri Deep Sea” | Poem |

| 1908 | Boy (Magazine) | “Haesangdaehansa” | Prose |

| 1909 | Boy (Magazine) | “Brave Boy on the Sea” | Poem |

| 1909 | Boy (Magazine) | “Three Sides Facing the Sea” | Poem |

| 1909 | Boy (Magazine) | “The Drifting Story of the Giant Country” | Translation |

| 1909 | Boy (Magazine) | “The Poem of Observing the Sea” | Poem |

| 1909 | Boy (Magazine) | Gulliver’s Travels | Translation |

| 1909 | Boy (Magazine) | “The Drifting Story of Robinson’s Unmanned Railway” | Translation |

| 1918 | Youth (Magazine) | “The Sea at the Front” | Poem |

| 1926 | Dongmyungsa (Press) | “Baekpalbeonnoe” | Poem |

| 1929 | Grotesque (Magazine) | “Jang Bo-Go, the Maritime King of the East and Shilla’s Cheonghaejin Ambassador of 1,100 Years Ago” | Prose |

| 1939 | Maeilsinbo (Newspaper) | “Chosun’s Myth — Marriage with the Marine God” | Prose |

| 1953 | Monthly Marine Korea (Magazine) | “The Sea and the Nation of Chosun” | Prose |

| 1953 | Local Government (Magazine) | “Marine and National Life” | Prose |

| 1953 | Seoul Shinmun (Newspaper) | “Ulleungdo and Dokdo” | Prose |

| 1954 | Seoul Shinmun (Newspaper) | “The Dokdo Problem and I” | Prose |

Choi Nam-Seon’s Modern Colonial Awareness of National Territory and Samgukyusa

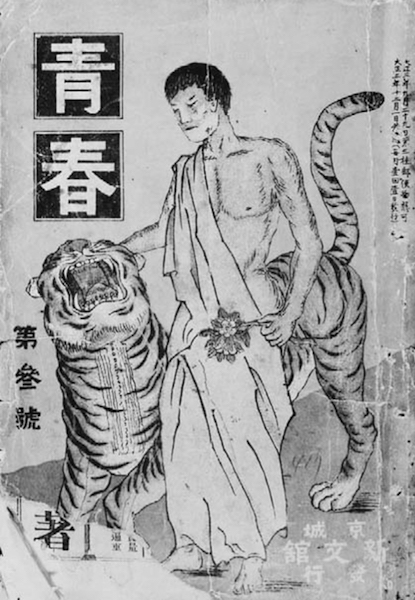

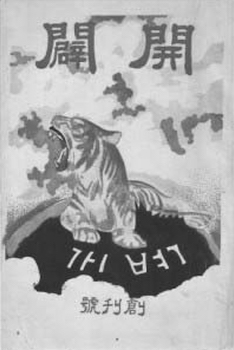

The debate between Japan and Korea regarding the awareness of national territory was instigated by the conflict between Rabbit-Shape Theory and the Tiger-Shape theory. By relegating the geographical form of the Korean peninsula to that of a fearful rabbit, Bunjiro Koto propounded the colonial discourse that might lead Koreans to disdain their own nation. In direct opposition to this, however, Choi Nam-Seon presented a theory that the Korean peninsula takes the form of a tiger in a work titled “Bong-gil's Geographical Study” in the year 1908 (1908:67). Asserting that national awareness can be instilled in a visual, geographical shape, Choi Nam-Seon actively refuted Koto’s claim. To do so, Choi purposely utilized the image of the tiger on the covers of Chungchun(Youth) and Gaebyeok (Beginning), magazines of which he worked on (see Figures 1 and 2). He also personally embarked on a journey traveling across the national territories represented by the tiger image. As such, the travels undertaken by the modern intellectual Choi Nam-Seon were not simply personal, leisurely trips, but deeply significance-laden ones symbolizing the resistance of the Korean people.

Choi Nam-Seon strove to instill meaning unto the notion of traveling ever since the publication of the first issue of Sonyeon in 1908. Not only did Choi claim that traveling was a great source of a true intellect, but he also elevated its notion by referring to it as a virtue of the modern intellectual. The main objectives of his national travels were to vertically visit the mountains of Chosun in person, and to mention the seas in his literary works in a horizontal sense. The cultural idea that language reflects the nation’s spirit was already and profoundly ingrained in Choi’s mentality. That is why he created Culture of Bulham in 1925, which traces the languages of Balk and Tangun. While composing this work, Choi crystallized his thoughts on Tangun that he had first raised in Gyegochajon in 1918. This also became a case in which he began to have interests in Samgukyusa, which presents the story of Tangun. Hence, it was due course that with the magazine, Gyemyung, owned by Gyemyunggurakbu Choi in 1927 published the work Samgukyusa Haeje (Interpretation of Samgukyusa), along with a preface that he added to the complete text of Samgukyusa (Choi Nam-Seon, 2013).

Composed by Ilyeon during the 13th century, Samgukyusa was unable to receive much attention during the Chosun dynasty, in which Buddhism was supressed and Confucianism was extolled. After this work was transported to Japan at the occasion of the Japanese Invasion of Korea of 1592, it had to endure the unfortunate circumstance of being neglected for 400 years. By reintroducing Samgukyusa in the early 1900’s back to Korea, Choi was able to render the work to produce various mythological meanings, just like the magical flute, manpasikjeok, in Samgukyusa. The status and background of Ilyeon, the author of Samgukyusa, bespeak the reason why the emphasis is on Buddhism, Gyeongju, and Shilla. Ilyeon lived between the years of 1206 and 1289. The span of those years includes the time when the Mongolian Empire conquered Goryeo for thirty years. In his early twenties, Monk Ilyeon experienced the excruciating circumstance of watching his country conquered by the Mongolian Empire. In fact, Ilyeon was 26 years of age when he witnessed the onset of the barbaric invasions of the Mongolians – one that would last for thirty years. For Ilyeon, culture was a narrative that expressed the people’s existence. It was through Samgukyusa that Ilyeon purported to present the distinct narrative of the Korean people, which was omitted from Samguksagi (The History of the Three Kingdoms), written by Kim Boo-Sik in 1145. In contrast to the Confucianist rationalism and humanism emphasized by Samguksagi, Samgukyusa directed its focus on Buddhist transcendentalism as well as on mythological and religious worldviews and sanctity. In other words, the overall purpose of Samgukyusa was to enable the Korean people — who were ignorant of their country’s roots and unable to feel national pride after decades of misery under the Mongolian invasions — to experience a sense of affection for their country through narrative.

Upon discovering Samgukyusa in the Japanese imperial library during his stay in Japan, Choi Nam-Seon returned the work to Korea in the form of a reintroduction. While publishing Sonyeon(Boy) in 1908 and Cheongchun(Youth) in 1914, Choi presented symbolic headwords with intensely mythological imaginations, such as the ‘sun,’ ‘child,’ ‘sea,’ ‘mountain,’ and ‘mother’ through various genres, including poetry, prose, and travel essays. It can be said that Choi was the boatman and initiator of intellectuals, for he held numerous interpretive keys for the modern era. There is little surprise for him to be referred to as the Pandora’s box in the modern literary history of Korea.

For Choi Nam-Seon, the formation of the people was a separate issue on its own, and thus a contradictory concept from socialism, nihilism, or cosmopolitanism. In other words, to Choi, national awareness could be raised only when there was an adequate national rival. Through Samgukyusa Haeje (Interpretation of Samgukyusa), Choi focuses on the fact that Samgukyusa presents the untold narrative of the three kingdoms. He further states that Samgukyusa presents incidents far livelier than the newspapers or general news of the present times. Thus, as Ilyeon endeavored, Choi emphasizes the fact that Samgukyusa was not an official historical record of kings and nobles, but instead an actual narrative of the people’s lives. With feelings of great esteem, Choi states that although composing the Samgukyusa was a single incident for Monk Ilyeon, it was, in fact, the greatest achievement that the monk could make in the world. Choi places an important historical meaning upon Samgukyusa, for he claims with relief that the work was not lost to the Koreans permanently. This can be confirmed in his writings on the section called “Dongseogye” in Donga Ilbo, during the time when he presented the Samgukyusa Haejae in 1927. On March 29, 1927, in the article entitled “The Starting Point of Chosun Historical Studies” in Donga Ilbo, Choi stated that the original manuscript of Samgukyusa was a secret resource which could not be discovered even with all the riches of the world; this is to say that even an incomplete reissue was considered priceless. Thus Choi emphasized that it was absolutely necessary to widely circulate Samgukyusa to the public in order to establish the study of Chosun and to rescue the nation. Furthermore, he stressed that Samgukyusa was an important book that should be memorized by every individual in Chosun, and should be taught in every home.

Choi underscored the cultural autonomy of Samgukyusa in order to raise the Korean people’s sense of rivalry regarding their relationship to Japan at the dawn of the modern era. Through narratives, Choi believed, a nation is able to unite its people united in one spirit. Choi declared that each nation’s people share a common psychological condition with their fellow nationals. For Choi, this was ultimately the defining trait of the people, which would then constitute a national character, when expressed. The important mythological truth as regarded by Choi was not a simple fact, but a purposeful belief (Seo Young-Chae, 2005: 101). Claiming that memory was an essential element constituting identity, Choi explained in multiple works that it is necessary to reflect upon histories, however ancient, in order to truly know oneself. Choi, the modern intellectual, defined the essence of Chosun’s culture in three characteristics — namely, globality, the shamanistic trait of Northeast Asia, and peninsularity.

The most notable idea in Choi Nam-Seon’s Tangunron is his claim that Tangun was not merely a political leader, but also a religious and cultural one. In another of his writings regarding Tangun, entitled “Dedication to Tangun – Realize the Heart of Chosun,” Choi states that Tangun is the pioneer of Korea’s national territory, the founder of life, the creator of Chosun’s culture, and the ancestor of every Chosun person in blood, and he also acts as the entrance to Chosun’s doors. Furthermore, Choi states, Tangun is the spirit of Chosun’s religious faith, the holistic personification, and the point of generalization that surpasses the nation as a whole. In other words, for Choi, Chosun was Tangun. Namely, Tangun was the comprehensive existence of culture, idea, and religion (Choi Nam-Seon, 1973: 192). He underscores the importance of culture by stating in many texts: “The people are small, but culture is great. History is short, but culture endures.” In the work The Mythology of Chosun (1930), Choi goes on to say : “Mythology is the religion, philosophy, science, art, and history of the primitive times.” In so doing, Choi emphasizes the fact that these elements are not separate, but in fact the greatest expression of the knowledge of humankind.

The Acceptability of the Sea in Samgukyusa as the Passageway of Different Cultures

Choi Nam-Seon stated that in order for the Korean people to move towards modernization under the Japanese colonial era, it was necessary to achieve psychological independence from Japan and develop a sense of opposition as an autonomous nation. With those means in mind, Choi strove to politically utilize the mythological aspects of Samgukyusa. By dismissing the Monk’s Nonsense Theory that Japanese scholars claimed, Choi purported to establish values as the subject of national pride. As indicated in Table 1, Choi presented various works in which the sea is conveyed as the main subject matter.

For Choi, the awareness of the sea in Samgukyusa is broadly formulated in two ways. The sea is at once a space of inflow where different people could enter through and also a space of acceptability where their cultures may be embraced. Table 2 represents how the myth of the sea within Samgukyusa was a locus where different cultures flowed in, as well as the point where Korea may begin to challenge other nations. Choi’s perception of the sea as the critical, driving force of culture can be witnessed from his early works to his later ones. The underlying context explaining why Choi viewed the sea in this manner can be found in his interests in geography and history. For Choi, the classics, including Homer’s The Odyssey, Lord Byron’s The Sea, Samuel T. Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, William Butler Yeats' Sailing to Byzantium, Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, and James Joyce’s Ulysses, all present the sea as the final order of nature that humans must overcome (Cho Gyu-Ik, 1994: 366).

| Title of Story in Samgukyusa | Marine Hero and Heroine | Simplified Mythic story | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The new marine civilization’s influence and the sea | “Garakgukgi” | Queen Huh | The heroine Queen Huh came to Kaya from India due to her parents’ dream across the sea. |

| “King Talhea” | Seok Talhea | Seok Talhea of the east nation came across the sea to Shilla as an egg and became the King of Shilla. | |

| “The Progenitor of Silla, King Heokgeose” | The Seondosan Holy Mother | The Chinese Seondosan Holy Mother came to Shilla across the east sea and gave birth to the Progenitor of Silla, Heokgeose King. | |

| “Cheyongrang and Manghaesa” | Cheyong | Cheyong, the son of the East Sea Dragon King, came to Shilla and obtained the most beautiful woman as wife. However, the smallpox god slept with his wife. | |

| The challenge posed by the new world and sea | “Surobuin” | Surobuin | The most beautiful Surobuin was kidnapped by the East Sea Dragon and experienced the fantastic marine world. |

| “Yonorang and Saeonyeo" | Yonorang. Saeonyeo | Yonorang and Saeonyeo traveled to Japan by means of moving rocks and became the king and queen. | |

| “King Munmu Bubmin” | King Munmu | King Munmu Bubmin died while fighting against the invasion of the Tang Dynasty and thus became a dragon of the East Sea which protects the nation. | |

| “Queen Jinsung and Geotaji” | Geotaji | Geotaji of Shilla rescued the island people from the attacks of an old fox and thereby marries a beautiful island woman who is the daughter of a dragon. | |

| “Goguryo” | Jumong | While being pursued by his step-brothers, Jumong of Buyeo crossed the sea and built the new nation Goguryo. | |

| “Great King Shinmu, Ryedmjang, Gungpa” | Chang Bo-Go | Chang Bo-Go of Shilla achieves great success in the Tang Dynasty and becomes the king of the sea after returning to Shilla. |

The future Choi Nam-Seon envisioned for his nation involved an awakening from oblivion through the cultural history of determination and challenge. He attempted to achieve this vision through the sea. In his work, The Nation and the People of Chosun (1953), Choi structured his narrative with subtitles, such as “The People Who Lost the Sea,” “The Fight for the Sea of Countries Around the World,” “The Sea and the History of Early Modern Chosun,” and “The Naval Pharmacists of Chosun.” The reason why Choi underscored the geographical view of history can be found from the fact that Chosun was a peninsula and circummarine state. In other words, Chosun was a peninsula surrounded by the seas on three sides. He thus reproved the Korean people for forgetting or neglecting the importance of the seas, even though the nation was surrounded by the seas on three sides. Choi claimed that each nation has its own specific personality. Accordingly, Choi asserts that continental nations must make the most of their continental traits; maritime nations must make the most of their maritime traits; mountainous nations must make the most of their mountainous traits; and peninsular nations must make the most of their peninsular traits. This, indeed, was the only way that each state can truly realize itself as a cultural nation (Choi Nam-Seon, 1993: 56-72).

The numerous mythologies of Shilla in Samgukyusa, such as “Garakgukgi,” “King Talhea,” “Go Jumong,” “Surobuin,” and “Manghaesa and Cheyongrang,” have close associations with the sea. Choi declares that Korea is a nation of a cultural people with a founding history that employs the sea. One must note that Choi refrains from overemphasizing geographical perspectives of history to make his claims on the sea. Instead, he endeavors to search for the sea comprehensively in terms of the historical, cultural, and mythological aspects. In his work, “The Sea and the People of Chosun,” (1953) Choi focuses on the historical and mythological incidents that utilized the sea, among which are Tangun, Talhea of Shilla, and Queen Huh of Kaya. First, in the debate on Tangun, Choi focuses on the fact that Tangun, the son of a god, marries the daughter of the god of water of Biseogap. At the same time, Choi draws attention to the fact that Biseogap is located on the corner where Daedonggang leads to the sea, as well as the fact that Tangun’s sons were sent to Ganghwa Island to establish Samlangseong and Jaecheondan. Another reason why Choi emphasizes this is that, culturally, Ganghwa Island was the strategical foothold that oversaw all things regarding the West Sea. As for Talhea of Shilla, Choi explicates, unlike the Kim clan which began with Kim Al Ji and the Park clan which began with Park Heokgeose, he was from Yongseongguk. This means that Talhea of Shilla was an individual with maritime culture who came from a foreign land in the northeast area. The final dynasty associated with maritime civilization that Choi focuses on is Queen Huh the wife of King Suro of Kaya. As a princess of the Ayuta kingdom of India, she was sent to King Suro because of a divine dream her parents had. Queen Huh thus traveled great distances all the way from India to Kaya as an heiress of maritime civilization. It is said that Queen Huh was equipped with the Pasa Stone Pagoda, numerous treasures, and Buddhism in order to calm the wind.

The belief that Buddhism traveled across the oceans and came directly from India to Kaya before the Common Era can be supported by the fact that it is an autonomous incident overcoming the cultural notion of power, according to which Buddhism was imported to Korea through China. It can be said that Ilyeon composed in various works mythologies where one could infer about Kaya’s propagation of Buddhism. Likewise, Choi Nam-Seon also considers Buddhism as a critically important imaginative foundation to search for Chosun’s mythologies. It is especially noteworthy to consider Ilyeon’s focus on Kaya. This is because it can be used as evidence to directly counter the Imnailbonbuseol Theory which claims that Japan conquered Kaya. Accordingly, Choi’s attention on Queen Huh’s story as a maritime mythology in Samgukyusa may be deemed as a scholarly achievement that overcomes China’s cultural toadyism and discloses the falsehood of Japan’s Imnailbonbuseol Theory. To go on further, Choi contends that the Buddhist culture delivered by Queen Huh contributed to refining Korea’s culture in three specific aspects. Firstly, Koreans were finally able to understand philosophy by accepting Buddhism. Secondly, the introduction of Buddhism provided opportunity to develop Korea’s art comprehensively. Thirdly, Buddhism led the Korean people of a strict feudal society to pursue equality and universality, thereby giving the Koreans courage and opportunities to discover their individual talents. Instilled with such courage, the people of Korea were able to travel to China and the countries bordering western China, and, as a result, were able to freely go back and forth between the continent and the seas.

The Pioneering Spirit of the Sea to Reach New Worlds in Samgukyusa

Choi Nam-Seon continuously endeavors to awaken the Korean people and to configure the future through narratives of the sea. Choi suggests three characteristics regarding Chosun’s oblivion of the sea. The first is that the spirit of grandness disappeared from the people of Chosun. Choi also observes the scarcity of available jobs in a small land, which leads to conflict and tension. As such, the people of Chosun were stricken with poverty. Choi states that Chosun was unable to effectively utilize its trait as a peninsular country, despite the fact that the land was surrounded by the seas on three sides. He indicates that countries such as Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and the Netherlands were able to become rich and powerful because each one effectively used the seas. Another trait regarding Chosun’s oblivion of the sea is that the nation was dominated by the continental China. Choi criticizes that this explains how the culture of Chosun came to submit to powerful nations.

According to Choi, the cultures of four major birthplaces of civilization mentioned in history classes – namely, Egypt, India, China, and Greece – were isolated ones. Instead, the civilization which Choi directs his attention to is the one that the unique ships of the Phoenicians established. Choi asserts: “The history of the world began when the Phoenicians built a unique ship and crossed the Mediterranean Sea for purposes of commerce and colonization. The development of world history was none other than people of various nations, such as Greece, Persia, Rome, and Carthage, navigating, fighting for power, and establishing legacy” (Choi Nam-Seon, 1993: 56-72). He also claims that Greece and Rome respectively were able to establish the Hellenistic world and the first great Roman Empire in history because both utilized the Mediterranean Sea effectively. Choi draws attention to the fact the Battle of Salamis, the Peloponnesian War, and Punic Wars, all took place in the sea as the center stage.

Choi Nam-Seon claims that Chang Bo-Go of the Shilla era and Yi Sun-Sin of the Chosun era should be constructed as the primary figures of Korean mythologies through the sea. Choi also stirs mythological imagination of the sea regarding the southern regions of the world through the work named Heosangjeon, written by Park Ji-Won in the later Chosun era. In so doing, he endows the mythological meaning on the word, “South Chosun,” with critical importance. Choi especially shows a positive stance toward the maritime figure, Chang Bo-Go, in Samgukyusa. He presents the prose work entitled, “Chang Bo-Go, the Maritime King of the East and Shilla’s Cheonghaejin Ambassador of 1,100 Years Ago” in the magazine, Gwaegi, which was first issued in 1929. By focusing on Chang Bo-Go in Samgukyusa, Choi counterargues the negative records of Kim Boo-Sik’s Samguksagi. After examining the records of Chang Bo-Go in the Chinese and Japanese literatures, Choi points out that the former’s commercial powers and influences were extensive. Not only so, Choi also examines how Japan maintained a cordial and hospital manner even after Chang Bo-Go’s death. As a result, Choi was able to confirm how influential Chang Bo-Go’s international characteristics and commercial powers were. It is especially important to note that Chang Bo-Go was the forerunner of maritime culture who unified commerce and religious faith. In order to unify the people of Shilla, Chang Bo-Go established Bubhwawon in Shandong Peninsula and solidified the psychological bond among the Shilla nationals. This may be perceived as a cultural activity comparable to the manner in which the merchants of the Western regions utilized Islamic communities (Yoon Myung Chul, 2012: 83). Subsequently, Choi draws his attention to the fact that there was great upheaval in the seaborne trade business when Chang Bo-Go died.

In his work, “The Sea and the Nation of Chosun” (1953), Choi proposes that Chang Bo-Go in Samgukyusa was the southern region’s ideal source of the original form of culture. Choi locates the ideal world of eastern and western mythologies in distant seas. As such, Choi draws focus on how China imagined Samshinsan and Yeonraedo to be situated in the seas of the eastern region, and how the Greek philosopher, Plato, depicted the enchanted world of Atlantis on the Atlantic Ocean. Likewise, the people of Chosun envisioned their ideal world on the southern seas. This can be perceived as a form of human desire towards the ideal. Choi asserts that for the people of Chosun, “South Chosun” was not merely the fruit of an ideology. The Korean people, he argues, already had a definite memory which delivered numerous cultures and sources of happiness from the southern seas. Choi observes that within this memory there was a figure named Chang Bo-Go from Samgukyusa. Choi emphasizes how in the later Shilla era, Chang Bo-Go, a great man of the seas, established various ports as beachheads of a traffic network, with Wando, Jeollado Province, in the center, connecting China’s Shandong Peninsula Hangzhou Bay and Japan’s Bukguju Haean and Inner Namyang. As the maritime king, Chang Bo-Go had great aspirations for the eastern seas and made great accomplishments through cultural commerce (Choi Nam-Seon, 1993: 56-72). Queen Huh’s arrival to Kaya introduced another nations’ culture across the great bodies of water to Korea. In the same vein, Chang Bo-Go was an individual who ventured outside his country to go across the seas with a pioneering spirit.

Conclusion

As Choi Nam-Seon states, mythologies are more than mythologies, in that they are also religion, philosophy, science, art, and history of the primitive peoples. Ever since he presented his work, “From Sun to Boy,” in 1908, Choi strove to awaken a sense of cultural and historical awareness of the Korean people through the sea. For Choi, the sea was a locus that would awaken the people from oblivion and also an experimental site where they could plan for the future and challenge themselves. Choi stated that the sea should no longer remain as a fearful object for the Korean people. In order to experience a renaissance, it was absolutely necessary for the people of Chosun to have a turning point. Choi clearly indicated that the sea should be the site of the inception. He further emphasized that the people should eradicate their fear of the sea and propounded that a new economic pathway for the people must and can be established through the seas.

Acknowledgements

This Research was supported by the Sookmyung Women's University Research Grants in 2014.

References

- Choi, N.-S., 1953. “The Sea and the Nation of Chosun.” Monthly Marine Korea. 56-72.

- Choi, N.-S., 1908. “Bong-gil's Geographical Study.” SONYEON 1 (1).

- Choi, N.-S., 2013. “New Revised Samgukyusa.” Kyungin Culture.

- Choi, N.-S., 2013. “The Theory of Folk Culture.” Kyungin Culture.

- Eom, T.-U., 2016. “The Chapter “Kiyi” in Samgukyusa, and the ocean.” Journal of North-east Asian Cultures 48. 65-85.

- Ilyeon, 2007. Samgukyusa (The Retained History of Three Kingdoms). Kim, W.-J., trans. Minumsa.

- Jo, K.-I., 1994. Seeking for the Marine Literature. Jipmundang.

- Kim, J.-R., 2006. “The enlightenment space recognition which appears in 'the railroad' and 'the ocean' - The modernity of Choi Nam-sun`s poem.” Comparative Korean Studies 14 (2), 85-106.

- Seo, C.-W., 2012. “A Study of Dualistic Meaning of 'the Sea' in Shilla Folktale: Suro and Cheyong.” Korean Classics Study. 26. 75-103.

- Seo, Y.-C., 2005. “A Way to Myth of Origin.” Modern Korean Literature 6 (2). 96-135.

- Yoon, M.-C., 2012. “The Meeting of Marine History and Future.” Hakyeon Culture. 83.