Gaming The Tide: The territorialisation of temporarily exposed English sandbanks for social cricket events

University of Technology Sydney, and Southern Cross University, Australia prhshima@gmail.com

Abstract

Over the last 200 years a number of sandbanks that rise above the surface of the sea or river estuaries for brief periods during low tide points have been site of cricket matches organised by teams based in adjacent coastal areas. The most regular locations for such performances have been the Goodwin Sands (an area of sandbanks located in the English Channel, close to the coast of the English county of Kent) and the Bramble Bank in the Solent. Other locations, such as banks in the River Tamar, have also seen one-off events of this kind. The article identifies these sports occasions as constituting particular forms of temporary territorialisations of space that adapt aspects of the game for the conditions of rapidly changing locations. The annual matches provide an example of the human rendition of spaces as temporary island neighbourhoods, the ephemerality of which is key to their attraction and meaning. Notably, they also involve a return to conventions of traditionally recognised ‘fair play’ in cricket that have significantly diminished in the modern form of the game. In this manner, the temporary spaces of the sandbanks allow for a revival of customs that relate to earlier participatory performance traditions and allow these to be re-affirmed.

Keywords

Goodwin Sands, Bramble Bank, Tamar, cricket, territorialisation

Introduction

In recent years the boundaries of Island Studies have become more fluid, loosening its exclusive focus on areas of land that are always above sea level and including consideration of an intermediate category of areas that are either above sea level at particular times or else are shallow enough to allow the construction of platforms upon them that can be used for strategic and/or residential purposes. Consideration of these areas, usually sandbanks, rocky shoals or coral reefs, has been particularly pertinent to sovereignty and related security issues in areas such as the South China Seas (see Tran, 2014) or areas such as the Minquiers and Écréhous reefs, located between Jersey and France, which Fleury and Johnson have characterised as existing “in a context of immense spatial change with substantial tidal ebbs and flows, and between mainlands and historically contested maritime terrain” (2015: 163). While more mobile 1 and less amenable to permanent construction than the rocky reefs Fleury and Johnson survey, sandbanks are also significant for emerging and subsiding in a manner that softens rigidly delineations of land and sea. In some instances, such as those discussed in this article, sandbanks have historical traditions of human engagement by particular local, regional, national and/or livelihood communities that marks them as social/socialised territories.

Human activities conducted upon and around sandbanks (temporarily exposed or otherwise) align themselves with the concept of the aquapelago, a combined terrestrial and marine space created by human livelihood activity that encompasses area of land and sea and, thereby, intermediate zones between them2. This approach acknowledges the human territorialisation of such spaces, including the incorporation of particular fishing grounds (that are often located above banks or seamounts) as integral parts of human territories that are based on terrestrial locations with access to them (such as the Grand Banks and the island of Newfoundland). There is also increasing acknowledgement that sport and recreational activities can habituate and territorialise areas of the sea, including sea surface features such as particular surf breaks or diving spots (see Nash and Chuk, 2012; Nash 2013). But one topic that has not received prior critical attention concerns human activity on subsurface features that break the surface on infrequent bases, such those exposed at seasonal equinox tides. This article explores this topic by analysing the performance of a particular sport - cricket - on sandbanks located off the English coast. It addresses the significance of this activity both within-itself and as a manifestation of a broader form of ritual territorialisation, a process of (temporarily) rendering shifting sands as places of human significance and engagement. With regard to a different type of coastal location, Suwa (2017) has discussed the manner in which an (otherwise unremarkable and uninhabited) rocky islet in northern Japan named Sakurajima3 is rendered as a shima (i.e. an insular human neighbourhood with particular associations and characteristics) on one day a year by the performance of ritual activities and subsequent celebrations on and around it. His emphasis is on the manner in which human activity makes the place as one with social character and significance that variously subsides and/or lies dormant until reactivated by subsequent performance of that space (in actuality, representation and/or memory). This article follows a similar approach, analysing how social cricket performances produce a particular kind of temporary territory for short durations whose associations accrue to and affect enduring perceptions of particular locations.

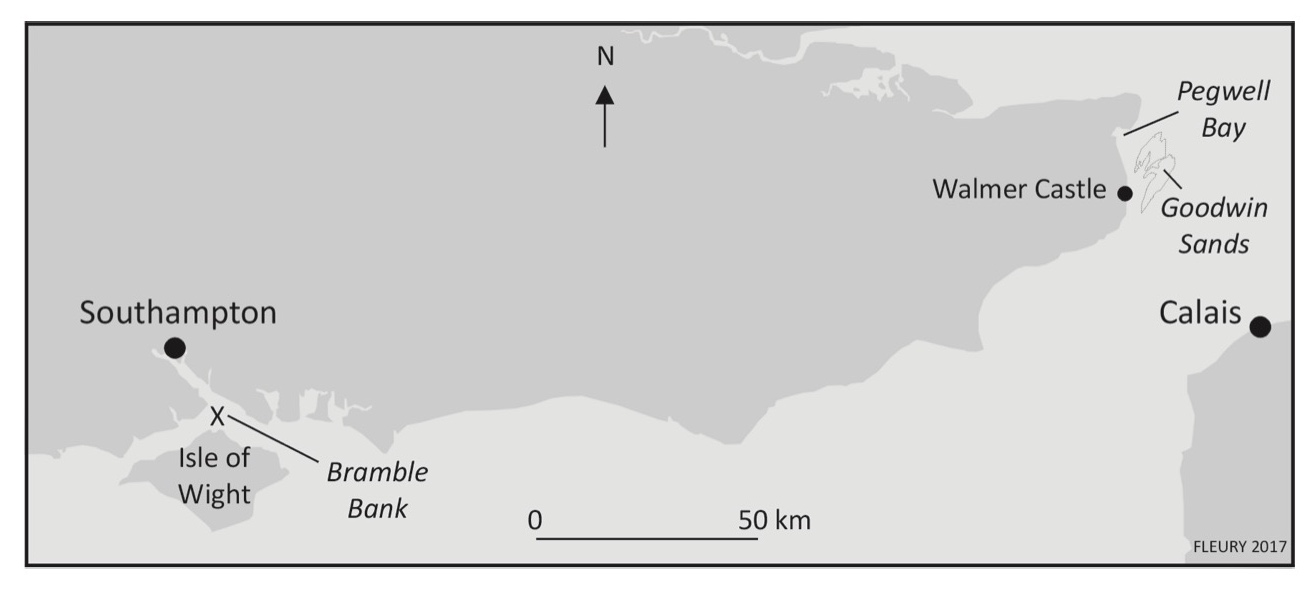

Sandbanks that break the surface of the sea temporarily at seasonal low tides occur at various places around the British Isles (and across the planet more generally). In many locations these attract little attention, or are else visited by boats that have either inadvertently run aground on them or else convey visitors for brief landings for exploration, picnics, photo opportunities etc. But a small group of locations in southern England are also significant for having been regular venues for sporting events. The two main locations of this type have been The Goodwin Sands, a 16 kilometre long area of sandbanks located in the English Channel, close to the coast of the English county of Kent, and the Bramble Bank (also know as The Brambles), a small sandbar in the Solent passage, due north of the port of Cowes on the north shore of the Isle of Wight. In addition, a sandbar in the Tamar River, between Cornwall and Devon, has also been the site of similar activity.

Cricket: The Game and its Cultural Contexts

Cricket is a team sport that developed as a codification of earlier social sports involving the striking of a ball with a wooden bat. It became formalised in the late 1500s in south eastern England, became a prominent national sport in the late 1700s, was diffused to various corners of the British Empire during the 1800s and early 1900s and is now popular throughout the countries of British Commonwealth. While the laws of cricket are notoriously complex,4 the following summary will suffice to contextualise the nature of sandbank cricket discussed below.

Cricket is played between two teams of eleven players and involves each team trying to amass the highest scores by striking a hard ball (of around 230 mm circumference) with a wooden rectangular bat. Unlike baseball, in which a batter stands in a single position until s/he is replaced by a successive batter, in cricket two batters are present on a flat playing area at all times (located at opposite ends of a rectangular strip called the wicket) and scores are accumulated by running between two fixed sets of stumps. The opposing team has eleven players on the playing area at all times, comprising bowlers and fielders. Bowlers each bowl six successive balls that usually bounce off the wicket before reaching the batter5, after which an alternate bowler bowls six balls from the other end. When not bowling, the bowler joins the players “fielding” (i.e. retrieving) the ball after it has been struck. A specialist fielder known as the wicket-keeper stands immediately behind the stumps and attempts to retrieve the ball when the batter misses hitting it and also attempts to catch the ball if the batter has contact with it that does not send it to other areas of the ground. The batter scores by hitting the ball and either running between the wickets until the fielding side retrieves the ball or by hitting the ball off the playing area along the ground (being credited with 4 runs without having to actually run them) or hitting it off the playing area in the air (and thereby being credited with 6 runs). The batter can have their batting period terminated (be “dismissed”) by various means, including having the ball caught in the air after leaving the bat, by missing the ball and allowing it to hit the stumps or by impeding the progress of the ball towards the stumps (an action known as “lbw” – i.e. leg before wicket6). When ten of the eleven players have batted and been dismissed, one team’s “innings” is completed and the other team goes into bat. Essentially, the team that amasses the highest scores (i.e. most runs made) wins the match. The match is adjudicated over by two referees (know as umpires) who aim to ensure that the rules of the game are abided are abided by.

Like all other major sports, cricket is a game played at various levels and with varying degrees of adherence to rules formulated to ensure conformity in the upper echelons of the game. The standard length of the central playing area (the pitch) in all forms of the game is 20.12 metres (22 yards in traditional Imperial measurement) long and the width is 3.05 metres (10 feet) wide. While not specified in the above rules, the overall playing space is usually in the shape of an oval, leading to the overall playing area often being referred to as such. The overall space of the playing area is divided into three areas – the pitch itself, an inner oval, a narrow area around this known as the close-infield, a broader oval area beyond this, known as the infield and the remaining encircling area, known as the outfield. Rule 19.1 specifies that in all cases “the aim shall be to provide the largest playing area, subject to no boundary exceeding 90 yards (82.29 meters) from the centre of the pitch to be used” and Rule 19.2 specifies that the outer perimeter should be marked by a boundary. Law 9 prescribes that, “professional cricket is almost always played on grass” but offers no prescription for non-professional versions of the game (that, nevertheless, tend to be played on grassed surfaces whenever environmental conditions allow).

Unlike some other sports, cricket is a game played in various formats, some formally prescribed – such as the international, five-day long “test” format and two shorter length ones, known as one-day and 20/20 formats7 - and some informal ones that have a flexible number of players and/or other variations. Adaptations of the game that follow the sport’s primary rules occur in various parts of the world and can include varieties in types of surfaces being played on and, on occasion, local revisions to the rules. When flat grass wickets are not available, various types of mats may be employed to attempt to produce level surfaces (such as coconut matting used in some regular cricket locations in Melanesia and Micronesia). There is also the well-established phenomenon of ice cricket, played on frozen lakes in various locations, which has had its own formal tournaments, such as those held in Estonia since the late 2000s.8 There are similarly, specific rules that apply to particular idiosyncrasies of established cricket grounds, such as trees being located within playing areas.9 By and large these aspects occur along with a general adherence to the spatial dimension of the central playing area, prescriptions of the broader playing space, the general structure of the game and a traditional sense of “fair play” formally referred to as “the spirit of the game”. The latter is a concept most commonly associated with an idealized, nostalgic vision of the game as polite “gentleman’s” sport that has been increasingly distant from the more aggressive version of the game played at various levels over the last fifty years. Reflecting - and in reaction to - the latter tendency, the components of the “spirit of the game” were formally enshrined in the preamble to the laws of cricket in 200010 via a number of guidelines for player’s conduct that revolve around notions of fair and polite competition.11

More ad hoc social variations of the cricket involve other factors that can complicate adherence to standard rules and/or modifications of the prescribed dimensions of the central wicket area. In some locations these variations have, themselves, been formalised into highly idiosyncratic versions of the game, such as that occurring in the Trobriand Islands of Papua New Guinea. In the Trobriands the game has been adapted to include a large number of players, the standard inclusion of dancing and chanting on the pitch to motivate teams and a concluding feast (see Kildea and Leach, 1979). One of the most significant informal adaptations is that of beach cricket. As its name suggests, this form is played on area of coastal sand using a variety of types of ball (usually – but not exclusively - rubberised versions of standard cricket balls or tennis balls) and may feature wickets improvised from found materials (drinks coolers or driftwood being common wicket materials). In games played by small numbers of players the standard game is often varied by having a single wicket at which each player takes turns to bat (often until a pre-set total of runs is reached12). The distance from the bowling point (known as the “crease”) and the wicket is often significantly shorter than in standard forms of the game. Unless the sand that is being played on is particularly hard, and will allow the ball to bounce to the batter, the bowler usually bowls the ball through the air. If the game is played close to the sea, particular ad hoc rules may apply (such as a six being scored if the ball is hit into the sea or, conversely that the batter is out if s/he hits the ball into the sea) and fielders may have to use unconventional fielding techniques to reach and retrieve the ball from the water.13

Even noting some of the more unusual variations in the game noted above, such as the ritualistic form of Trobriand cricket or the variety played on frozen lake surfaces, the type of cricket performed on temporarily exposed sandbanks off the English Coast is one of the most idiosyncratic with regard to the standard game and the particular performances of space that take place on the temporary surfaces.

Sandbank Cricket14

a) The Goodwin Sands

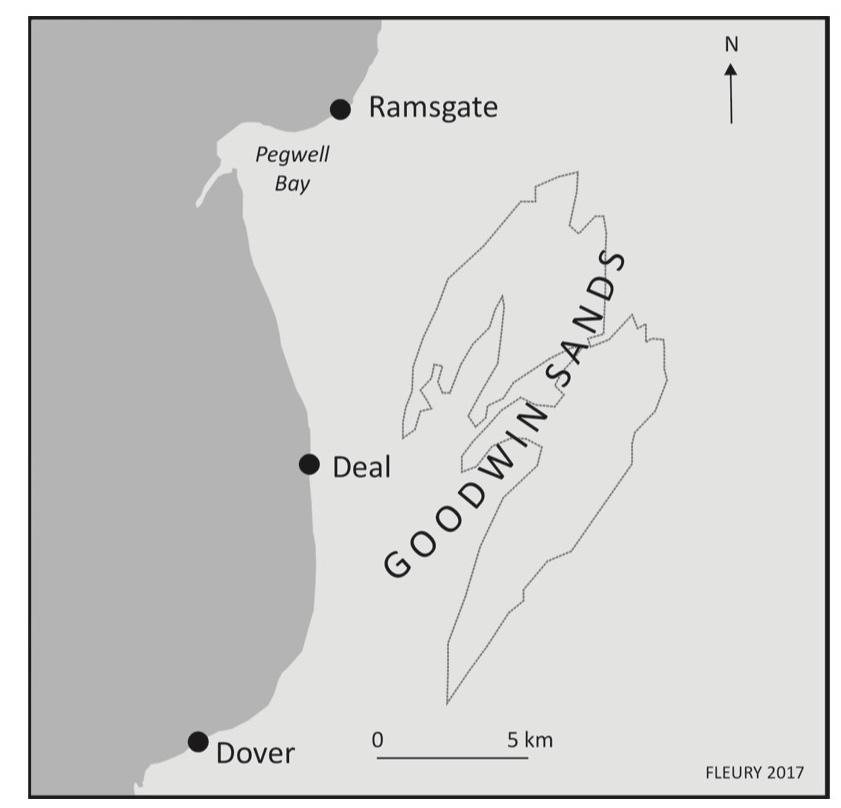

The Goodwin Sands is a large area of shifting sandbanks, about 16 kilometres in length, running roughly parallel to the shore off the east coast of the county of Kent between Pegwell Bay (to the north) and Walmer castle (to the south) (Fig. 1 and 2). Located approximately 10 kilometres from the coast, the sandbanks appear above the surface for brief durations, with the largest areas being exposed for longest periods during Spring and Autumn equinoxes, when tidal variations can be as much as 5 metres feet. This factor has caused the Goodwin Sands to have been a major hazard for shipping in the English Channel over many centuries, with estimates of the number of ships having been wrecked in the area since records began in 1285 varying between 1000 and 3000.15 The most catastrophic event occurred in November 1703. During the so-called ‘Great Storm’, four British Navy battleships were wrecked on the Sands with the loss of 1200 lives. As Bathurst has detailed, the hazardous sandbanks contributed directly to coastal livelihoods during the 1800s, with groups of specialists, including “hovellers16, smugglers, pilots and salvors all working the Sands and all devoting themselves to different aspects of both healthy ships and wrecks” (2005: 42). Since the advent of various modern navigational aids and, most recently, GPS (Global Positioning System) tracking, the number of wrecks has greatly diminished and the sandbanks are more frequently visited by local fishermen or seasonal excursionists.

As previously discussed, cricket became a major national sport in England during the late 1700s and early 1800s, with a particularly strong institutional and player base in the south-east of the country. The first recorded match staged on the Goodwin Sands occurred in summer 1813 and attracted local controversy “as a blasphemy against all those victims of the rapacious sands” (Chamberlain, 2017: online). Another well-known match was organised by Captain K. Martin, deputy harbourmaster at the nearby port of Ramsgate, in 1824. While there appear to be no visual representations of the 1813 and 1824 matches, the renown British landscape painter J.W. Turner attended a subsequent match there and produced a small chalk and watercolour painting of proceedings some time between 1828-1830 (Fig. 3). In typical Turner style, the image is more impressionistic than realist but gives a strong sense of the experience of playing the match in the liminal area between the sand shore and adjacent sea. While indistinct, the image shows an area of flat sand from a slightly elevated position that implies the painter’s position on a raised dune looking down on the playing area, on which nine individuals appear to be playing.

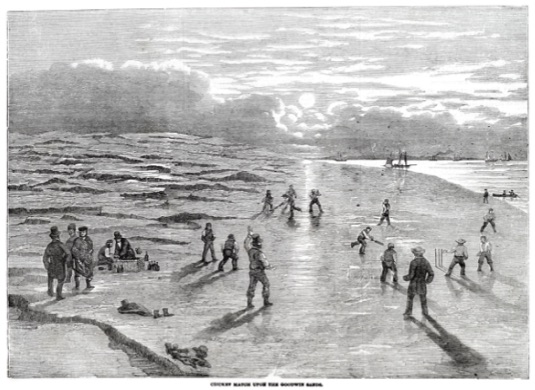

An engraving of a social cricket occasion some 30 years later (Fig. 4) was published alongside a brief item in the Illustrated London News on August 26th 1854 reporting on a game attended by an un-named reporter. The report is significant for its description of the match and of the incongruity of it being played in a location well known for causing loss of life and shipping assets. The description of the fast-moving waterways that striate the banks as the tides shift complements this by underlining the dangers of playing in the location:

“The Goodwins,” which have been from time immemorial associated with peril and destruction, have just been the scene of exhilarating sport. It appears that on the 10th inst a party – got up by Mr. Morris Thompson, Mr. Hammond and others, at Walmer – visited the Sands for the purpose of playing a game of cricket. Captain Pearson and a picked crew of the Spartan, one of the finest luggers on Deal Beach, were selected for the occasion. The day was beautifully calm, and the party (twenty-four in number) arrived, and were safely landed on the Sands at five in the evening. After walking about a quarter of a mile, a place sufficiently high and dry was found; when the match commenced, and continued to nearly sunset, the winning party obtaining fifty-seven runs. The Sands were intersected in every direction with narrow but deep gullies, or, as they are known by the sailors, “swatches,” with swift running streams into which it was dangerous to step. A sad association of ideas crowded the mind on looking over this awfully melancholy place. Here thousands of gallant fellows have been entombed – here millions of property have been engulfed; and here was a picture contrasting vividly with the present scene of pastime. (Unattributed, 1854: 176).

This engraving complements the report by showing a large area of sandbank exposed and a number of individuals (eleven fielders, one bowler and two batsmen) playing beach cricket adjacent to the sea in the company of other men variously standing around, picnicking or arriving by boat (in the rear of the image) and also shows the elevated dune structures suggested by the point-of-composition position in Turner’s earlier painting.

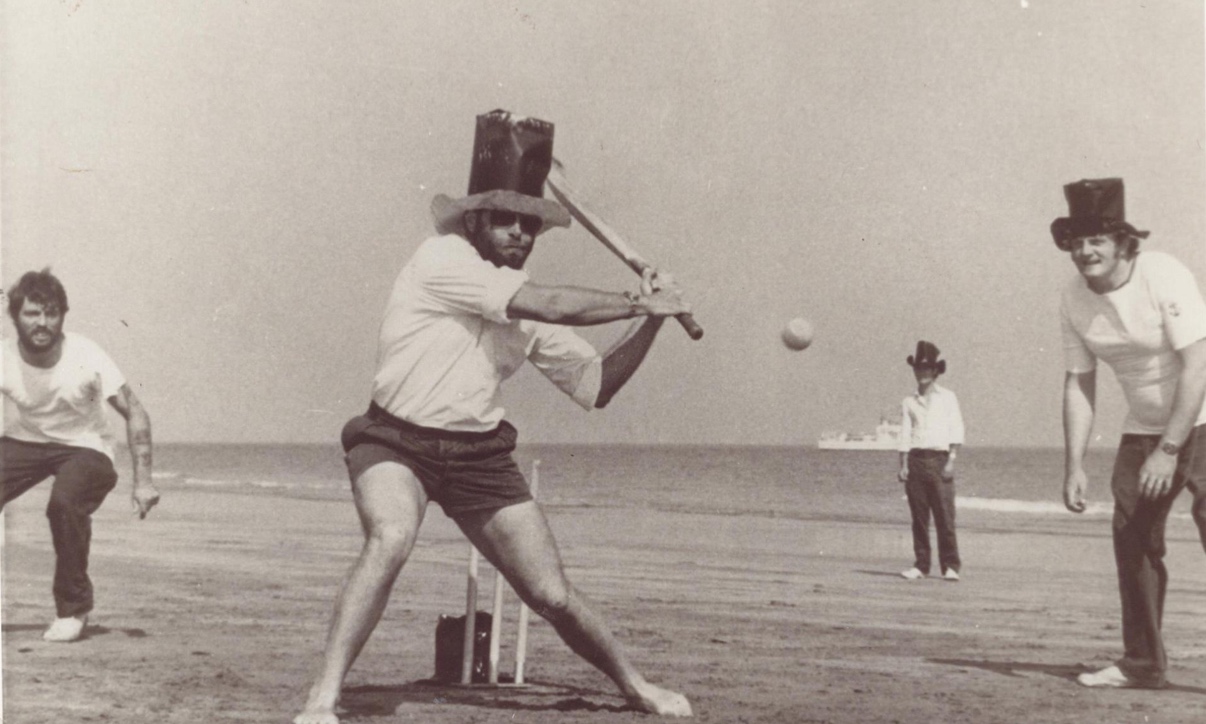

While there is no evidence of cricket being played regularly on the Sands between the late 1800s and mid 1900s, there has been a regular stream of cricket played either in impromptu situations or as staged events over the last 70 years. The former category includes a match staged between crews of the Royal Navy Survey ships HMS Egeria, Echo and Enterprise in 1973 (Fig. 5) informal games played by visitors on trips organised by the British Hovercraft Museum Society in the 1990s and early 2002s (see Seehund, nd: online) and one-off formal charity matches such as that played between a Kent county side and a team from Thanet in 1985.18

Recent media interested in the eccentric – and highly photo/tele-genic – phenomenon has also, unwittingly, inscribed its risky nature into its representations. In July 2006, for instance, the BBC documentary series Coast recruited members of Beltinge village cricket club to travel out to the Sands, clad in the formal cricket uniform of white shirts and trousers, and briefly stage a few cricket sequences for a short item in the series. As one of the Beltinge players later reported:

What followed, however, was real enough. As the tide rose and the Goodwins sank we splashed back to the waiting boat. However, the weight of cricket and television teams with their assorted gear meant that we stuck on the Sands, side-on to the incoming tide. We clambered back into the water, chest-deep, to try and swing the boat round but we were stuck fast. Plan B involved sitting in the boat until we were floated off by the tide… However, a strengthening north-easterly was whipping up waves that broke over the side of the boat, filling it with water and sinking it deeper in the Sands… Eventually, and none too soon, the driver of the boat put out a mayday call. After a wait no doubt shorter than it seemed, the lifeboats arrived, our craft was pulled away and we were transferred to a larger vessel for our return… The BBC lost 100,000 pounds worth of equipment but saved the film. Beltinge lost much of its gear but the BBC has seen to it that we shall start next season with new kit. (2006: online)

b) Bramble Bank

The Bramble Bank is a small individual sandbank, of which roughly 1,500 square metres is briefly exposed above water at optimal equinox tides, located in the Solent passage between the northern tip of the Isle of Wight (to the south) and Southampton Water inlet (to the north) (Fig. 1). Given the markedly lower volume of (large draft) shipping that has historically travelled through the area (at least prior to the development of Southampton as a major port in the 1830s), and its smaller size, the area has nowhere near as large a list of wrecks as The Goodwin Sands. Bit despite modern navigational aids, the awkwardness of its position continues to be a nuisance for shipping, with various ships being temporarily stuck on the sands in recent decades (such as the Queen Elizabeth II which ran aground on the bank in 2008, on her last passage as a Cunard fleet liner, and, more recently, the container ship APL Vanda in 2016).

It is uncertain when cricket was first played on the Bramble Bank, and whether familiarity with the history of playing matches on Goodwin Sands inspired the development of an annual tradition, but it is generally considered that cricket was played on the bank sporadically by sailing enthusiasts from the Island Sailing Club (ISC) at Cowes, on the north of the Isle of Wight (IoW), and that at some time in the 1980s the Royal Southern Yacht Club, at Hamble-le-Rice, on the adjacent mainland, challenged the ISC to a cricket match that went on to become a regular occasion (at least, when tidal conditions have permitted). The in-betweenness of the temporary ground is not insignificant, allowing teams from the island and the Hampshire coast to play on neutral territory, outside the associative and administrative remit of either area. This point was even a matter of discussion in the United Kingdom House of Lords in 2003 during the course of debates around Amendments 236 and 301 of the Licensing Act, when it was identified that the Bramble Bank, home of periodic cricket events, has the unusual status of being outside of national licensing jurisdictions in that:

it is covered by water most of the year. It is not in the city of Southampton or in any of the adjoining councils of New Forest, Eastleigh or Fareham. Neither is it in the area that is covered by Isle of Wight council. (Turner, 2003: online)

When annual tides are at their lowest a small area of sandbank emerges from the sea of sufficient area to allow for a pitch, close-infield and a (varying extent of) infield, allowing for a fairly standard version of the game to be played with around the usual number of players. The number of players is not tightly regulated, as in standard cricket but depends on the number available, with some flexibility being allowed. The only specific rule that has developed for Bramble cricket has been a pragmatic one in that each team takes turn in winning in successive years, with the result known in advance. This ensures that the tournament is a “friendly” one19 and also allows catering arrangements to be made in advance (since the victors entertain the losers at their sailing club after the game has concluded (and specific catering arrangements need to be made). Dependent on weather and conditions a variable number of spectators (primarily non-participating members of the sailing clubs and/or friends and family of the players concerned) observe either from the edges and/or shallow surrounds of the playing area (when the bank is most exposed) or, on the occasion of less-conducive, lower tides, from boats moored around the perimeter. In recent years local and, on occasion, national media crews have often covered the event, with a variety of coverage being available online (most notably, Williams [2012] and Naik [2012]).

In years when the Bank is suitably exposed and when the weather conditions are favourable to landing and playing, the version of the game conforms to the loose conventions of beach cricket, albeit with a standard set of stumps and bails being used and with a standard (hard) ball being bowled. With an average exposure time for the bank of around one hour, the game can accommodate around six or seven overs per side, with these being hurried through (compared to regular competitive cricket) and with there being negligible variations in fielding positions in response to the introduction of different bowlers or batters.20 Humour is generated during play by fielders who either fall over into areas of water or otherwise intentionally dive into them in pursuit of the ball. Some determination has been needed to make the annual event go ahead on particular occasions. In 2008 attempts to play were severely impeded by the depth of water on the bank, although a semblance of a game was attempted, and in 2012 the bank failed to fully arise above the surface and players had to dismount shallow draft boats and climb on to the bank in ankle deep water. A five minute video of the 2012 match available online21 shows a group of around 16 fielders standing around the wicket in close infield positions, their distance from the wicket seemingly determined by the drop-off in depth of the sandbank that results in fielders standing furthest from the wicket being knee-deep in water. Fielding was complicated when the ball drops or was hit into the water, having to be retrieved, and fielders on the outer perimeter are shown struggling through in deeper water in their attempts to retrieve the ball. Similarly the batters’ speed in running between the wickets (and, thereby, accruing runs) was impeded by the depth of water. Waves washing across the wicket also caused an issue in that around 75% of the wicket (a single pole on this occasion) was often underwater, making it difficult for any batter to be clearly bowled out (unless the visible top section was directly hit). Unsurprisingly the batters shown in the video are dismissed through being caught by fielders.

In the case of the Brambles (and the other locations discussed in this article) participating in social sport played in an improbable location that requires planning, resources and general ingenuity to get to and perform on has lead to both a wholehearted embrace of the “Spirit of Cricket,” referred to in Section I, and a willingness to apply this to the adaptation of the standard rules of the game to particular conditions. The following account exemplifies this, with batter (Sir) Robin Knox-Johnson reporting that in 2015 he was “waved out,” by which he meant “the ball landed in the water and a wave picked it up and hit my stumps, so I waded, I thought it was the gentlemanly thing to do” (in Riley, 2016: online). There are several significant aspects to this anecdote. One concerns the player’s willingness to recognise and accept a new method of dismissal (water-born carriage of the cricket ball onto the stumps) and the second, his decision to “wade” off the wicket. The latter term refers to a convention in traditional “gentlemanly” cricket for a player to walk off if s/he perceives that s/he is out (due to being lbw, edging a ball to a fielder etc.) without being instructed to by the umpire. “Wading off” is a gentlemanly extension of this that also involves the impromptu identification of and conformity to a new rule, despite it being to the batter’s disadvantage.

c) The Tamar River, Customary Sports and English Eccentricity

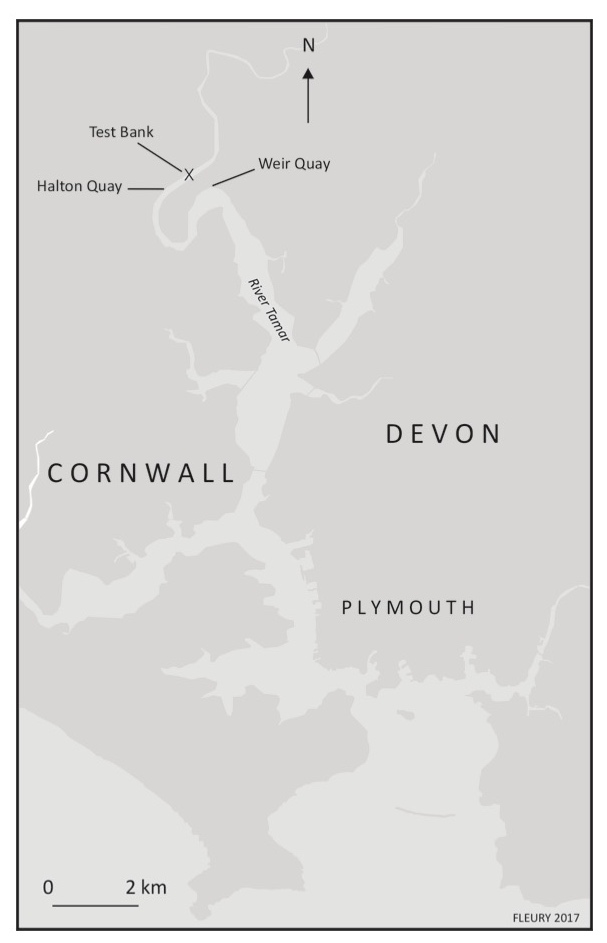

In April 2016 an integrated combination of cricket, traditional morris dancing22 and the singing of patriotic county songs was organised on an exposed bank in the upper reaches of River Tamar (close to Halton Quay). The match was played between the Weir Quay Sailing Club (Devon) and Cargreen Yacht Club (Cornwall). Similarly to the Bramble Bank matches discussed above, cricket occurred on an exposed bank and with fielders standing on its fringes, in shallow water or else stationed on the periphery in boats. The event was enhanced by performances of traditional Cornish and Devon songs to open the proceedings and the appearance of the Cornish Wreckers morris dance troupe “to perform their dances as a blessing to this new surface” (Hinge, 2016: 1).23 After the match a single piper sounded a lament as the participants left the (rapidly submerging) bank. The event had a particular significance in terms of territory and the territorialisation of its bank space in that the Tamar has formed the boundary between the counties of Devon and Cornwall for many centuries, its watery barrier reinforcing senses of difference and, on occasion, rivalry between the counties, an aspect that was reflected in the event’s description as ‘The Tamar Test’.24 The match was made possible by an unusually low tide, of a type usually seen only once a decade or so.25

As in the case of the Brambles bank matches, new rules were devised for the occasion by the event’s instigator, Michael Tucker. These were made available to participants in a souvenir program and included provisions for catches by fielders in boats and for no runs to be scored if batters hit the ball into reeds.26 Similarly to the nature of the Bramble Bank between the IoW and Hampshire mainland noted above, the temporary surfacing of a bank in the space of the Tamar created what can be regarded as a median/neutral ground on which the friendly contest could occur. This aspect was light-heartedly inscribed in a further special rule adopted for the game, namely that the winners would determine the precise constitution of the scones (flour based confections) served after the game, Devonian style traditionally requiring dollops of jam to be placed on cream on the scones and Cornish requiring cream to be added on top of the jam).27

The sense of shared endeavour and the combination of the Tamar event with traditional song, foods and morris dancing underlines the manner in which sandbank cricket is not an isolated, idiosyncratic phenomenon but rather invites comparison to historically well established, eccentric (and often somewhat anarchic) English customary sports events, such as the Cooper’s Hill cheese rolling pursuit in Gloucestershire and the Hallaton Easter hare pie scramble and bottle kicking contest in Leicestershire.28 Participation in these events fosters a significant sense of community belonging and local difference that is enacted via involvement and through adherence to the particularity of its rules and procedures. Media coverage of the event (such as the BBC News item, 2016) both stressed its highly localised nature and framed it within a context of recurrent English eccentricity, similarly to standard coverage of the Bramble Bank matches.29

Conclusion

Interviews and correspondence with various organisers and participants in sandbank cricket matches undertaken during research for this article have identified a common cluster of motivations. These include a sense of playfulness in organising the sports occasions in barely tenable temporary locations, a sense of shared communal enterprise in pulling off the (often complex) logistics and a more general sense of pride at being associated with them. Underlying these is a sense of the opportunistic and the transgressive in staging social events in ephemeral spaces that are usually regarded as hazardous for human transport through such areas. In the case of the Goodwin Sands matches, we can identify an attempted re-signification of the Sands as a leisure site (rather than a ships’ graveyard). In the case of Bramble Bank, the games do not so much re-signify a space as demarcate one in the nether-waters between the IoW and coastal Hampshire. Similarly the ‘Tamar Test’ was staged in a temporary space in between the two counties, allowing for ritualised invocations of both in an affable context. In all three contexts, traditional aspects of the “spirit of cricket” have also been re-affirmed through the modifications required to conduct the game in unconventional locations, allowing the events to contribute to the ongoing heritage of the sport at a local level.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Christian Fleury for providing maps for the article; to John Allen, Rosie Hinge, Jill Trew and Michael Tucker for their assistance with research; and to Jon Sutton for his informative comments on an earlier draft.

Endnotes

References

- Bathurst, B., 2005. The Wreckers. Harper Collins, London.

- BBC News, 2016. River Tamar mudflat cricketers make the most of low tide. BBC News, online at: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-36009247

- Chamberlain, D., 2017. A walk on the sands’. Bygone Kent, online at: http://bygonekent.org.uk/article/a-walk-on-the-sands

- Edmond, R., 2006. Now that’s a real wash-out. Wisden Cricketer November, online at: http://www.espncricinfo.com/wisdencricketer/content/story/263587.html

- Fleury, C. and Johnson, H., 2015. The Minquiers and Écréhous in spatial context: Contemporary issues and cross perspectives on border islands, reefs and rocks. Island Studies Journal 10(2), 163-180.

- Hignell, A., 2002. Rain Stops Play: Cricketing Climates. Routledge, London.

- Hinge, R., 2016. River Tamar: Cricketers for the Day. Weir Quay Yacht Club news report.

- Ice Cricket, 2013. Welcome to the Home of Ice Cricket, online at: http://www.icecricket.co.uk/index.php

- International Cricket Council, 2017. Rules and Regulations- Key Documents, online at: https://www.icc-cricket.com/about/cricket/rules-and-regulations/playing-conditions

- Kildea, G., Leach, J., 1979. Trobriand Cricket: An Indigenous Response to Colonialism (feature-length documentary film).

- Lords (nd). Spirit of Cricket: Preamble to the Laws. MCC, online at: https://www.lords.org/mcc/mcc-spirit-of-cricket/what-is-mcc-spirit-of-cricket/spirit-of-cricket-preamble-to-the-laws/

- Morison, J., Daisley, P., 2000. Hallaton, Hare Pie Scrambling & Bottle Kicking: Facts and Folklore of an Ancient Custom Hallaton Museum Press.

- Nash, J., 2013. Landscape Underwater, Underwater Landscapes: Kangaroo Island Diving Site Names as Elements of Linguistic Landscape. Landscape Research 38(3), 394-400.

- Nash, J., Chuk, T., 2012. ‘In deep water: diving site names on Norfolk Island’, Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 10(4), 301-320.

- Naik, G., 2012. A Cricket Match, in the middle of the sea. Wall Street Journal video report 27th September, online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Les61fEToNo

- Perry, S., 2009. Bramble Bank: Morris Men Dance on the Solent (Photos and Video). On the Wight 23rd August, online at: https://onthewight.com/bramble-bank-morris-men-dance-on-the-solent-photos/

- Pilley, K., 2015. How’s that? The Scots catch on to beach cricket. The Telegraph 4th June, online at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/lifestyle/11651062/Hows-that-The-Scots-catch-on-to-beach-cricket.html

- Practical Boat Owner, 2009. Morris dancers descend on Bramble Bank. Practical Boat Owner 27th August, online at: http://www.pbo.co.uk/news/morris-dancers-descend-on-bramble-bank-10411

- Riley, S., 2016. Yacht Clubs meet for the annual Bramble Bank cricket match... in the middle of the Solent, online at: http://www.royal-southern.co.uk/News-Desk/ID/1037/Yacht-Clubs-meet-for-the-annual-Bramble-Bank-cricket-match-in-the-middle-of-the-Solent

- Russell, S., 2013. Sand bank over a mile off the Great Yarmouth coast is venue for sports challenge. Eastern Daily Press 6th September online at: http://www.edp24.co.uk/news/sand_bank_over_a_mile_off_the_great_yarmouth_coast_is_venue_for_sports_challenge_1_2369520

- Seehund (nd.), “Goodwin Sands’, online at: http://www.seehund.co.uk/html/goodwin_sands.html

- Sharp, C. and MacIlwaine, H.C., 1907. The Morris Book (Volumes 1 and 2), London: Novello and Co.

- Spiers, V., 2016. ‘Cornish Wreckers and cricket in the mud’, Guardian 20th April, online at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/apr/20/morris-dancing-cricket-mud

- Suwa, J., Becoming Island: The Aquapelagic Assemblage of Benten-sai Festivals on Sakurajima, in Sai Village, northern Japan. Shima 11(2). (Forthcoming 2017).

- Tran, G., 2014. Contested Space: National and Micronational Claims to the Spratly/Truong Sa Islands – A Vietnamese Perspective. Shima 8(1), 49-58.

- Turner, A., 2003. Statement to The House of Lords’ Standing Committee D’s discussion of proposed amendments 236 and 301 to the Licensing Bill, online at: https://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmstand/d/st030508/am/30508s02.htm

- Unattributed, 1854. Cricket-match on The Goodwin Sands. Illustrated London News August 26th, 176.

- Williams, J. (2012). Bramble Bank Cricket, online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ya39uYeb8P4

- Word Of Mouth, 2016. It’s scone wrong. Guardian Word of Mouth Blog, online at: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/wordofmouth/poll/2010/may/20/cream-tea-scone-clotted-cream