The mutual gaze: Host and guest perceptions of socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism: A case study of the Yasawa Islands, Fiji

School of Business, Khon Kaen University (Nong Khai Campus), 112 M.7, T. Nong Kom Koh, Muang, Nong Khai 43000, Thailand srosup@kku.ac.th

Abstract

The mutual gaze enacts both hosts and guests. This paper expands the literature relating to the impact perspective of backpacker tourism. It investigates how hosts and backpackers perceive the socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism on local communities in less-developed countries; specifically the Yasawa Islands of Fiji. The discussion is based on data collected via surveys and a series of interview with hosts and backpackers in 2011. The results suggest that hosts and backpackers significantly perceived the socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism differently. While backpackers are generally neutral in their perceptions regarding their own impacts on the destination, the hosts are notably more aware. This knowledge is fruitful as it can inform destination policymakers in their deliberation on further sustainable tourism practices.

Keywords

Perception, Backpacker tourism, Socio-cultural impacts, Less-developed countries, Fiji

Introduction

While links between “perceptions of tourism” and “stakeholders” have been highlighted in the tourism literature (Moufakkir and Reisinger, 2013, p. xiii), there is a dearth of understanding on tourists’ perceptions of their impacts on visiting destinations. Past studies on tourism impact perceptions have predominantly paid attention to the perceptions of hosts; focussing largely on residents’ perceptions, whilst little emphasis has been on the perceptions of their guests. Challenging that narrow unilateral approach, this paper borrows from the concept of “mutual gaze”, that proposed by Maoz (2006). She notes the importance of recognizing that the gaze, and hence the perception generated is garnered through more than a single lens – only a one-way gaze. Rather, a reciprocal gaze is at play and thus, a “mutual gaze” of tourist to locals, locals to tourists, and tourist to tourists, all have constant influences on perceptions. This mutual gaze contributes to the tourist/host encounter and each gaze has a consequential effect on the other (Maoz, 2006). It is important to therefore incorporate the tourist gaze into tourism impacts literature. Van Winkle and MacKay (2008) pointed out that tourists will not adjust their behaviour in order to diminish their negative impacts on a destination if they are unaware of their own generation of these impacts. As such, the research that investigated how both hosts and tourists think about tourism may be considered as important as it can facilitate how a destination develops towards greater success and sustainability (Moyle et al., 2012).

Within backpacker tourism literature, there is a research gap concerning hosts’ and guests’ perceptions of the impacts of backpacker tourism. According to some researchers (Richards and Wilson, 2004b; Scheyvens, 2002), there is a limited knowledge on the impacts of backpacker tourism on local communities in less developed countries (LDCs). The extant literature on the impacts of backpacker tourism is significantly based on the perspectives of outsiders (researchers and scholars) (Hampton, 2009), whilst the crucial perspectives of hosts and backpackers themselves have been relatively overlooked. Additionally, most of the extant studies have focused on the economic impacts of backpacker tourism whilst other dimensions of impact are still under-explored. This paper reduces the current knowledge gap, shedding light on the understanding of the socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism from the perspectives of both hosts and guests.

The term ‘backpacker’ usually refers to a budget-minded international traveller who generally travels with a rucksack to several destinations, taking longer trip duration than conventional tourists, has a flexible itinerary and often utilize backpacker infrastructure such as public transport and budget accommodation (Loker-Murphy and Pearce, 1995; Sørensen, 2003). Drawing on this definition, “backpacker” as defined in this study is characterized as an international traveller staying in budget accommodation, travelling away from his/her residence for at least one month, and having a flexible and extended travel itinerary.

The exotic “Other” or the authenticity of places and people is a crucial part of backpacking for the development of their cultural knowledge (Cohen, 1982; Desforges, 2000; Elsrud, 2001; Young, 2005). Accordingly, backpackers are inclined to avoid touristy destinations and wander away from the well-trodden tracks (Kontogeorgopoulos, 2003). They believe that the real experience from travelling is gained by practising an “anti-tourist” mode. They therefore avoid, as much as possible, travelling patterns performed by conventional tourists (Loker-Murphy and Pearce, 1995; Welk, 2004). As Maoz (2005) claims, backpackers can empower local communities as they pay attention to the authentic “Other” which encourages them to interact with and patronise locally-owned enterprises. Therefore, the growth of backpacker tourism in such circumstances is beneficial at the local level. Despite the apparent correlation, the context of host–guest encounter in backpacker tourism literature has scarcely been discussed (Hampton, 1998; Scheyvens, 2002; Wilson, 1997).

Host and tourist perceptions of socio-cultural impacts of tourism

A number of previous studies have investigated host perceptions of socio-cultural effects brought by tourism (Besculides et al., 2002; Brunt and Courtney, 1999; Haley et al., 2005; King et al., 1993). Those studies tend to report that hosts are more likely to perceive the socio-cultural impacts as rather negative (Brunt and Courtney, 1999). This supports Kousis (1989) who notes, tourism has often been blamed for the disruption of socio-cultural spheres of the local community. Concerning its positive side, tourism is perceived by hosts as a device for revitalizing cultures (Besculides et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2006), creating more recreation choices for locals (Brunt and Courtney, 1999), providing prospects for women to participate in its informal sector activities (Shah and Gupta, 2000), and increasing residents’ concern on their heritage resources (Andereck et al., 2005). As regards the socio-cultural costs, the issue of crime (robbers and burglars) has been highlighted by a number of scholars as the perceived negative effect of tourism amongst host residents (Belisle and Hoy, 1980; Long et al., 1990; Milman and Pizam, 1988; Pizam and Pokela, 1985). Other researchers found that hosts seem to perceive tourism as leading to an increase in drug use (Andereck et al., 2005; Belisle and Hoy, 1980; Pizam, 1978), alcoholism (Milman and Pizam, 1988; Pizam, 1978), prostitution and sexual permissiveness (Ap, 1990; Ap and Crompton, 1998; Carter and Beeton, 2004).

Amongst a relatively limited research that focuses on the socio-cultural tourism impacts perceived by tourists, Petrosillo et al. (2007) indicate that tourists at an Italian marine protected area are more aware of its negative social effects such as overcrowding at the destination. Similarly, Manning et al. (2000) found that the perceived social tourism impacts amongst visitors in the US Acadia National Park often involve the irritations of crowding caused by other visitors and that these reduce the quality of their tourism experience. Such findings support Farrell and Marion (2001) who indicate that tourists frequently recognise the impacts that directly affect the quality of their tourism experiences. Furthermore, Suntikul (2007) found that tourists who visit Muang Sing Village in Laos express concerns about the development of tourism that may harmfully affect the locals’ way of living. The negative impacts of tourism perceived by tourists are associated with changes in the locals’ lifestyle.

There are a relatively limited number of studies that pay attention to the perceptions of both hosts and tourists towards the impacts of tourism in a single destination or community. The majority of the previous studies have found differences between the perceptions of the two parties (Byrd et al., 2009; Canavan, 2013; Dowling, 1993; Holden, 2010; Holdnak et al., 1993; Ismail et al., 2011; Kavallinis and Pizam, 1994; Lucas, 1979; Puczkó and Rátz, 2000; Sánchez Cañizares et al., 2015; Saremba and Gill, 1991; Simpson, 1999). Amongst the studies that have focus on how hosts and tourists perceive the socio-cultural impacts of tourism, Ismail et al. (2011) found that hosts and tourists significantly perceive the socio-cultural impacts of tourism on the small Malaysian islands differently. The hosts are shown to explicitly express more positive views than their guests on the issues that tourism generates welfare (e.g. more variety in recreational facilities, improves public infrastructure) for their communities. Holden (2010) found different perceptions towards the effects of tourism in the Annapurna Conservation Area in Nepal between hosts (lodge owners and tour guides) and tourists (trekkers). The hosts were more concerned on the socio-cultural effects of tourism than their guests. The social benefits brought to the community perceived by the hosts such as increased educational opportunities for children and improved households’ hygiene and sanitation and helped in revitalizing the local culture. The negative impacts of tourism included introduced begging habits of children, increased drug (Marijuana) usage, and changes in locals’ dress code, hair and lifestyle. In contrast, tourists were concerned more on the economic contribution of tourism to the locals and the environmental issues of the destination.

Canavan (2013) found that whilst tourists in the British Isle of Man pay more attention to the issues of natural surroundings, residents appreciate most the social benefits that tourism brings to the island communities, though residents were worried about the decline in tourist numbers which could lead to a decrease in social welfare facilities (e.g. entertainment facilities) which were provided through tourism. Similarly, Sánchez Cañizares et al. (2015) reveal that hosts (residents and business owners) and tourists on the African island of Sao Vicente evaluated more than half of the tourism impact issues employed in their study differently (out of 17 issues). The results indicate that whilst tourists are satisfied with the tourism services and the environmental condition of the islands, the residents are more doubtful about the support for future tourism development in the area as they are discontented with the negative effects of tourism (crime, shortages of goods and services, absence of shopping spaces and establishments). These studies tend to suggest that hosts are more concerned about the socio-cultural effects of tourism on their society, in both a positive and a negative light, than are their guests.

Impacts of backpacking on hosts

In comparison to international mass tourism, which is actively promoted by national governments in less-developed countries (LDCs), several researchers asserted that backpackers contribute to the significant positive benefits of local economies in developing nations (Cohen, 2006; Hampton, 1998, 2003, 2013; Scheyvens, 2002, 2006; Scheyvens and Russell, 2012; Visser, 2003, 2004). Those studies have verified that backpackers are significant contributors to the grassroots local economy as they tend to stay longer in a destination, consume more locally produced goods and often use local services (e.g. accommodation and transport) than other tourists types, this a high income multiplier is ultimately generated within the destination. Regarding the environmental impact, on the one hand, backpackers are regarded as friendlier travellers to the environment, particularly when compared to conventional mass tourists. On the other hand, with regards to the trait of backpackers seeking out the new, exotic and unspoilt destination, they are inevitably blamed for opening up new tourism tracks for mass tourists (Bradt, 1995; Butler, 1980; Cohen, 1972; Spreitzhofer, 1998; Wheeller, 1991).

In terms of socio-cultural impacts of backpacking, backpackers who are mostly from Western cultures often express a desire to experience the local way of life and to meet “Others” (locals and other travellers) as a prime motivation for their trips (Loker-Murphy and Pearce, 1995; Riley, 1988; Sørensen, 2003; Uriely et al., 2002), they tend to engage more in social relationships with locals than other tourism types (Anderskov, 2002; Loker, 1993; Richards and Wilson, 2004b; Scheyvens, 2002). Consequently, backpackers can facilitate cross-cultural understanding through interactions with their hosts (Aziz, 1999). Moreover, several studies have noted that backpackers are interested in paying respect to other cultures (Paris and Teye, 2010; Young, 2005; Young and Lyons, 2010). Their practices, such as appropriate dressing, learning some local language and culture, and seeking permission before photographing people are documented (Speed, 2008). Backpackers’ interest in local cultures can also revitalize local cultural practices (Scheyvens, 2006). Scheyvens (2002) observes that there are many skilled artisans such as weavers, carvers, and potters who are considerably admired by backpackers. Additionally, a recent study about backpackers’ impacts in the old Chinese town of Li Jiang conducted by Luo et al. (2014) reported that the local residents affirm that backpackers are more beneficial than mass tourists especially in helping to preserve their culture and positively modifying their local life-style. Backpackers are perceived as giving more broad-based value to host regions as they are travelling in more remote areas than ever before. The locals also recognize that backpackers are inclined to develop their understanding of the local community through direct contacts and express that backpackers will then promote first-hand information about the place, thus assisting in the preservation of the traditional culture. Meanwhile, the understanding of mass tourists about themselves and their place is often mistakenly formed by the influence of the tour guides (Luo et al., 2014).

On the contrary, some researchers claimed that the close and sincere contacts of backpackers with local people can create greater socio-cultural harm on the host society. As Butler (1989) notes that long-term travellers (drifters or explorers) can result in greater adverse and longer term effects particularly on the socio-cultural structures of a host’s community than mass tourists. This is due to a higher degree of contact with hosts and a wider penetration into personal and sensitive spaces including homes, sacred places, and traditional ceremonies. In support to Butler’s assertion, Kontogeorgopoulos (2003) found that apart from demonstrating hedonistic and party-oriented behaviour, many backpackers in southern Thailand forget about the conservative local [Thai] attitudes on female nakedness and improper sexual conduct. The lack of awareness and sensitivity amongst those travellers caused considerable resentment in the host communities (Kontogeorgopoulos, 2003). Furthermore, backpackers are often blamed by host residents on their appearance and behaviour, particularly their scanty and improper casual dress, binge drinking, drug use, and overt sexual conduct, all of which can be a violation to the host population and their customs (Aziz, 1999; Cohen, 2003; Mandalia, 1999). For instance, the Indian beaches in Goa, a major attraction amongst backpackers, have a reputation for beach parties, nude swimming, drug availability, sunbathing, and open sex amongst the travellers (Colaabavala, 1974). Consumption of soft drugs is a prominent backpacking experience in some destinations such as Gili Trawangan (Indonesia), Zipolite (Mexico) and Goa (India)1 (Hampton, 2013). Other studies about backpacking in Sydney (e.g. Bondi Beach, Coogee Beach) report similar situations (see Allon and Anderson, 2009; Bushell and Anderson, 2010). Backpackers are also reported as those who are often involved with casual sexual conduct (Aziz, 1999; Berdychevsky et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2009). For instance, Berdychevsky et al. (2010) found that casual sex and other extraordinary sexual behaviours are perceived by backpackers (women Israeli backpackers) as an integral part of their adventure. It is apparent that the impact of backpacker tourism is a contentious subject (Cohen, 2003). The empirical evidence indicates a diverse view amongst the different stakeholders regarding general impacts of backpacker tourism on local communities. This paper therefore aims specifically at the socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism, narrowing the gap in the extant literature. Acknowledging the influences of the mutual gaze on stakeholder perceptions, the paper investigates how hosts and backpackers each perceive the socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism on local communities in the Yasawa Islands, Fiji.

Case study: the Yasawa Group of Islands, Fiji

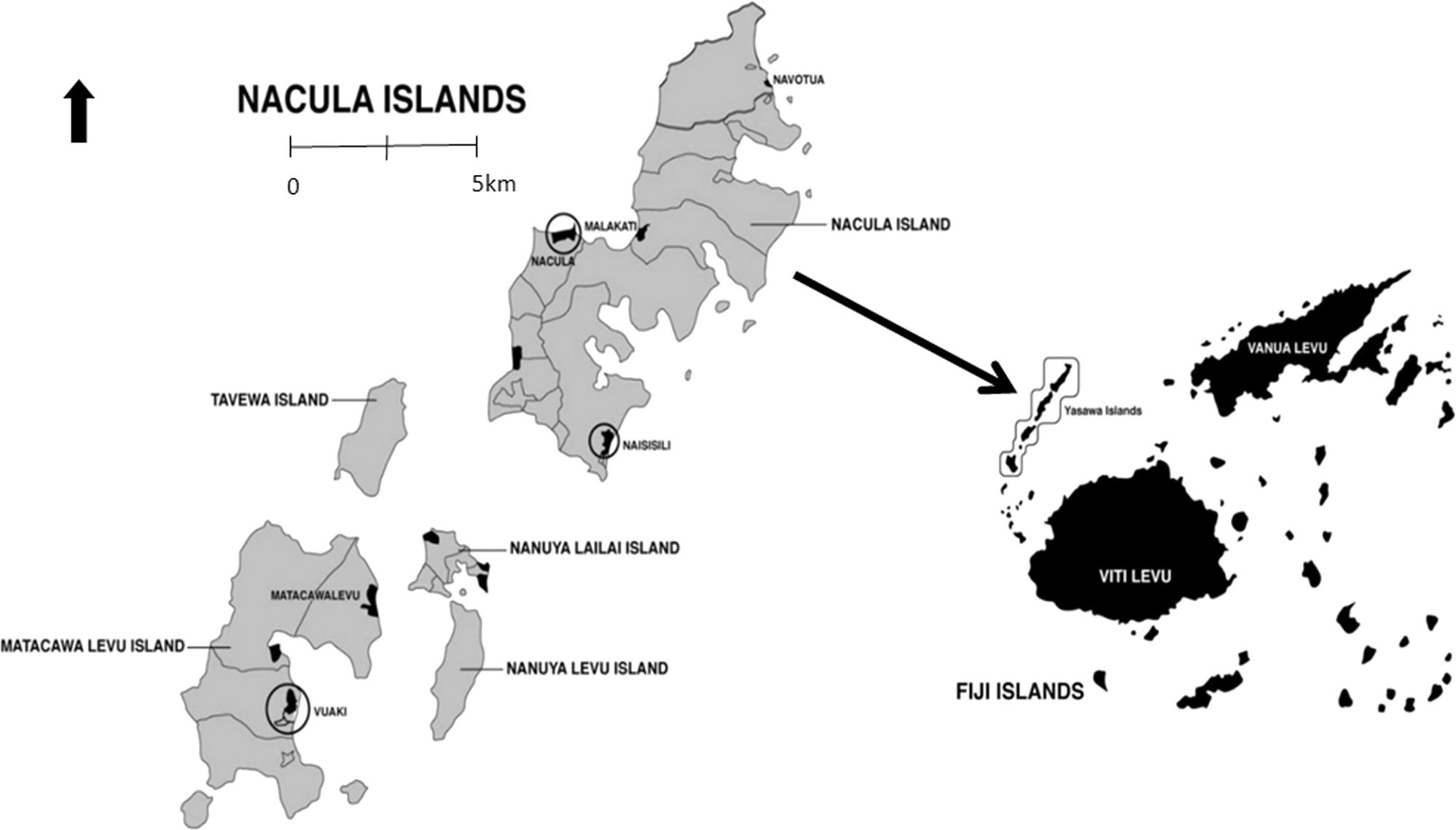

The empirical data on which this paper is based was collected between August and November 2011, from hosts and backpackers in the Nacula district of the Yasawa Group of Islands, Fiji (see Fig. 1). Backpacker tourism is one of the key market segments which have been encouraged by the Fijian Government to attract international travellers (Tourism Fiji, 2011). The Yasawas is one of the most concentrated areas for backpacking in Fiji (Ministry of Tourism and Environment, 2007). The remote Yasawa Islands Group is attractive for its abundant sunshine, white-sandy beaches, turquoise lagoons, spectacular reefs and welcoming friendly locals. Consequently, it is receiving over 545,000 visitors per year, a steep contrast to the 1164 residents (District Office Lautoka/Yasawa, 2011). The development of backpacker tourism is a key economic prospect for the local people on the Islands and has grown over the past two decades (Kerstetter and Bricker, 2009; Scheyvens and Russell, 2012).

The Nacula district was chosen as the study site because it accommodates the majority of the tourism activity as opposed to the other areas of the Yasawas (Awesome Adventures Fiji, 2011–2012). There were nine backpacker resorts operating in the area each with which mostly less than 25 rooms. They are locally owned and offering “all-meals inclusive” packages. Backpackers largely access additional “fee for use” tourist services including entertainment, diving equipment and local boat transport through their resort reception. The activities commonly provided are diving, snorkeling, fishing, trekking, caving, and village visits. Based on local informant advices, the top three most visited villages by backpackers, those of Nacula, Naisisili and Vuaki (circled in Fig. 1), were chosen as data collection sites.

Methods

Most research into perceptions of tourism impacts has employed quantitative approaches. This leads to generalised conclusions and limits the potential to gain a more in-depth understanding of the impacts (Deery et al., 2012; Woosnam, 2011; Zhang et al., 2006). In order to avoid such limitations, a convergent mixed methods research approach was employed in this study more thoroughly addressing the aims of the research.

The study employs structured-questionnaire surveys, semi-structured interviews and informal conversations. Selected members of the host community along with visiting international backpackers were engaged both purposively and by convenience. The host participants included indigenous Fijian villagers, tourism business investors, tourism industry employees, governmental officials and destination policymakers.

To evaluate the perceptions, the surveys employ 16 socio-cultural tourism impact attributes as identified by Ap and Crompton (1998), Hampton (1998), Scheyvens (2002), and Speed (2008). In accordance with previous studies (e.g. Byrd et al., 2009; Haley et al., 2005; Lankford, 1994; Nyaupane and Thapa, 2006; Weaver and Lawton, 2001), sets of 5 Likert scale rating questions (1 = strongly agree; 5 = strongly disagree) was employed in this research for assessing perceptions of tourism impacts. An interview guide, along with audio-recording, was used for the semi-structured interviews. A research diary was used to record the interview conducted through informal conversations.

The surveys and interviews were conducted with different members of hosts (residents, tourism business owners, tourism industry employees, governmental officials and destination policymakers) and backpackers of different regions of origin (North America, Europe, British Isles, Australia and New Zealand, and Asia). Convenience sampling was applied with both hosts and backpackers while further purposive sampling was adopted with the governmental officials in order to draw a sample that was information rich.

The survey of hosts was conducted at community halls, their homes and work places whilst the backpackers were surveyed at backpacker resorts and on the Yasawa Flyer.2 A total of 206 useable questionnaires from the hosts and 390 from backpackers were collected through both researcher-administered and respondent-administered surveying techniques. The survey’s response rate for hosts is 89.6%, and for backpackers is 89.7%. In respect to the interviews, an informal conversation was adopted to ease a relaxed friendly encounter with backpackers and villager hosts. The semi-structured interviewing technique was applied to governmental officials and destination policymakers in order to respect their status as working in more formal organizations.3 Interviews were undertaken post-survey. This enabled the path of interviews to be commonly guided by the survey findings.

Demographic characteristics of respondents

The majority of the host survey respondents were native (indigenous) Fijian (96.6%), their highest education level was high school (73.8%), were male (51%), and were aged 18–30 years (38.8%). About two third of the host respondents were residents4 (63.6%), the rest were tourism industry employees (28.2%), tourism business owners (3.9%), governmental officials (2.4%), and, destination policymakers (1.9%).

The majority of the backpacker survey respondents were female (56.9%), aged 26–35 years (40.5%), were first-time backpackers (54.1%), taking a less than three months backpacking trip (36.4%), and about one third had obtained an undergraduate degree (32.1%). With an average length of stay 8.8 nights in the Yasawas, their average spending in the islands was F$ 1263.80 (or US$ 589.70).

All interviewees had completed the survey beforehand.5 Host interview informants (n = 71/206) characterize 34% of survey respondents and backpacker interview informants (n = 30/390) characterize 8% of survey respondents. Further details about respondent characteristics are represented in Table 1.

| Respondent groups | Surveys (N = 596) |

Interviews (N = 101) |

|---|---|---|

| Host – Residents | 131 | 34 |

| Nacula villager | 54 | 15 |

| Nasisili villager | 52 | 12 |

| Vuaki villager | 25 | 7 |

| Host – Tourism business owners | 8 | 8 |

| Owner operated backpacker resort | 7 | 7 |

| Owner of café | 1 | 1 |

| Host – Tourism industry employees | 58 | 16 |

| Staff at backpacker resort | 57 | 15 |

| Staff at marine transport company | 1 | 1 |

| Host – Governmental officials | 5 | ⁎9 |

| Central organization | 1 | 3 |

| Regional organization | 4 | 5 |

| Local organization | - | 1 |

| Host – Destination policymakers | 4 | 4 |

| Prime Minister’s office | 1 | 1 |

| The village chief | 3 | 3 |

| Guest – Backpackers | 390 | 30 |

| Britain, Ireland and Scotland | 165 | 7 |

| Mainland Europe | 143 | 14 |

| North America | 41 | 6 |

| Australia and New Zealand | 20 | 1 |

| Asia | 18 | 1 |

| Brazil, Israel, South Africa | 3 | 1 |

- ⁎

- See footnote number 5.

Data analysis

The quantitative data collected through surveys was analysed using a range of appropriate descriptive and inferential statistics. The Mann–Whitney U test was employed to assess the significance of differences between hosts and backpackers towards the perceived socio-cultural impact of backpacker tourism. A significant difference is considered to exist if the significance level (p-value) verified is 0.05 or less. Content analysis was employed to analyse the qualitative data collected through interviews. The interpretation of the results of this study employed a quantitative-led analysis technique. While the primary focus is on the survey findings, the interview data are used to explain the survey findings for the meaningful understanding of the research subject (Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009).

Results

Table 2 highlights the way that hosts and backpackers perceive the socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism. The results of the Mann–Whitney U tests indicate that three quarters (12 out of 16) of the socio-cultural impact items are perceived significantly differently between the hosts and those of their backpacker guests. The discussion herein is divided into two parts:

- Part 1): The differences of host and backpacker perceptions of the socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism.

- Part 2): The similarity of host and backpacker perceptions of the socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism.

| Perception of socio-cultural impacts | Hosts | Backpackers | Gap score (b) | Mann–Whitney test | p-value (c) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (a) | SD | Mean (a) | SD | ||||

| Leads to decreases of religious values amongst local people | 2.451 | 1.115 | 3.267 | .786 | 0.816 | 22607.0 | .000 |

| Increases alcohol-drinking amongst local people | 2.234 | 1.198 | 3.018 | .908 | 0.784 | 23617.5 | .000 |

| Decreases respect of local youth for elders | 2.498 | 1.223 | 3.238 | .809 | 0.740 | 25790.0 | .000 |

| Increases social conflicts amongst local people | 2.426 | 1.195 | 3.064 | .820 | 0.638 | 27034.5 | .000 |

| Increases crime in communities | 2.654 | 1.197 | 3.275 | .864 | 0.621 | 27876.5 | .000 |

| Does not create respect amongst backpackers for indigenous customs | 2.966 | 1.086 | 3.576 | .929 | 0.610 | 27883.5 | .000 |

| Leads to decreases of family values and unity amongst local people | 2.663 | 1.107 | 3.264 | .857 | 0.601 | 27395.5 | .000 |

| Helps revitalize indigenous culture | 2.102 | .897 | 2.577 | .841 | 0.475 | 27255.0 | .000 |

| Increases prostitution in communities | 3.863 | 1.103 | 3.436 | .854 | 0.427 | 27911.5 | .000 |

| Increases drug-taking amongst local people | 2.961 | 1.279 | 3.262 | .788 | 0.301 | 36121.0 | .042 |

| Leads to changes in traditional ways of life amongst indigenous people | 2.141 | .952 | 2.397 | .784 | 0.256 | 31409.5 | .000 |

| Encourages learning of local culture amongst indigenous people | 2.151 | .817 | 2.287 | .755 | 0.136 | 34427.0 | .002 |

| Increases casual sex amongst local people | 3.005 | 1.177 | 3.128 | .814 | 0.123 | 38422.0 | .472 |

| Leads to destruction of indigenous culture | 2.829 | 1.207 | 2.956 | .890 | 0.127 | 37821.5 | .260 |

| Increases interaction between indigenous local people and tourists | 1.980 | .773 | 1.967 | .732 | 0.013 | 39776.0 | .908 |

| Encourages learning of local language amongst indigenous people | 2.483 | 1.144 | 2.495 | .814 | 0.012 | 36544.5 | .067 |

- Mean score calculated as an average from a five-point scale (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree).

- Gap score (highest Mean score – lowest Mean score) represents the differences of the average perception between hosts and backpackers.

- Significant differences in the perceptions of hosts and backpackers (significance level (p-value) at 0.05).

The first part is further clustered into three broad themes of the impacts including (a) The negative social behaviours of backpackers; (b) The effects on indigenous culture and custom; and (c) The effects on values and relationships amongst the locals. Each theme involves individual impact items which were selected based on their content richness. For the second part, only two of the four impact items are discussed. Again, each is selected due to the strength in the interview data that best demonstrates the similarity in views between the two respondent groups. Even though, there were no statistically significant differences in perceived impact between hosts and backpackers for the any of the four issues of “leads to destruction of indigenous culture”, “encourages learning of local language amongst indigenous people”, “increases interaction between indigenous local people and tourists”, and, “increases casual sex amongst local people”, the latter two impacts are discussed.

Part 1: the differences of host and backpacker perceptions of the socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism

The negative social behaviours of backpackers

As displayed at Table 2, regarding the issue of backpacker tourism “does not create respect amongst backpackers for indigenous customs”, both hosts and backpackers were neutral in their opinion, neither agreeing nor disagreeing. However, the hosts tended to agree more on this effect than their guest counterparts. Based on the interview data, amongst the hosts who agreed with this issue, Tom (resident, age 37) commented: “Some backpackers don’t respect our customs by wearing inappropriate dress during the village visit6 and while attending the church service. Some also don’t take off their shoes while visiting the village chief’s Bure.7” Additionally, Alesi (Naisisili, age 60) reflected: “Some tourists wearing shorts and hats into the village which those are not allowed. Sadly, there was also a case that a backpacker wearing only a bikini come into our village without asking for the permission to entry”.8 These narrations support previous studies (Jamieson, 1996; Kontogeorgopoulos, 2003; Mandalia, 1999; Noronha, 1999) which suggested that backpackers were not concerned about local norms and customs. In contrast to host views, some backpackers like John (Swedish, age 28) commented: “Backpackers are mostly good tourists especially in terms of giving respect to the local culture. For me, I did follow the code of conduct while visiting the Fijian village”. The researcher similarly observed that most backpackers followed the village protocol during their village visit with just a few of them less respectful. However, the researcher realized that conformist behaviour on the part of the backpackers was highly subject to the tour coordinator’s understanding and respect for local culture. Resort coordinators, who bring tourists into the village, play a vital role in determining the extent of the effect of this issue. This depends upon how well the coordinators are trained in local custom and then how concerned they are to inform their guests about village protocol prior to visiting the village.

With regards the issue of backpacker tourism “increases alcohol-drinking amongst local people”, whereas the backpackers were neutral in their opinion, the hosts agreed with this effect. As regard the views of hosts, Miri (resort staff, age 28) commented: “Backpackers drink every night and they also invite the staff to join. Eventually, many of us [resort staff] are now addicted to the alcohol.” Further, Bill (resident, age 42) reflected: “In the past, we drink only Kava,9 yet, since tourism developed into our place we started drinking alcohol”. Further, Emosi (resident, age 79) reflected: “There is an increase in both Kava and alcohol drinking especially amongst the youths as now they have more power [earned money from working at resorts] to buy such stuff”. These narrations appear to suggest that the introduction of backpacker tourism has brought in an alcohol drinking culture to the host communities. In support of the host opinions, Thomas (American, age 26) expressed his opinion towards drinking behaviour amongst their fellow backpackers: “Young backpackers, especially those aged less than twenty, love partying and drinking. They drink a lot till late at night”. This perception formed through the mutual gaze supports the findings of Jarvis and Peel (2010) who reported that backpackers in Fiji are increasingly associated with young travellers who spend too much time in binge drinking.

Regarding backpacker tourism “increases drug-taking amongst local people”, whereas the backpackers were neutral in their opinion, the hosts tended to agree with this effect when compared to their guests. As regard the views of hosts, Sam (resort staff, age 40) reflected: “About six years ago, a lot of Marijuana were sold here which was initially brought in by the tourists…” Further, Inoke (governmental official, age 40) commented: “Recently, Marijuana was planted in one island within the Yasawas to sell to backpacker resorts”. Moreover, Jon (resort staff, age 40) commented: “During this year, our guests brought Marijuana into the resort and invited us to try”. These narrations seemed to be affirmed by Ana (resident, age 70) who said: “When some locals get their wage from working at the resorts, they go to buy Marijuana from the mainland and then hiding and smoke it in the village”. Here, it tends to suggest that drug (Marijuana) was introduced to the local people by the tourists (including backpackers). These narrations appear to support the earlier studies (Cohen, 2006; Colaabavala, 1974; Dodds et al., 2010; Hampton, 2013; Uriely et al., 2002) which noted that backpacking involves drug-related activities as part of the travel experience.

The effects of backpacker tourism on indigenous culture and custom

In terms of the issue of backpacker tourism “helps revitalise indigenous culture”, both hosts and backpackers agreed with this impact, however, the hosts were more strongly in agreeance with this than were backpackers. Based on the views of hosts, Mosese (governmental official, age 40) described: “Meke10 has been slowly dying out in Fiji. Fortunately, we are now presenting it to entertain the tourists”. Peni (policymaker, age 61) reflected: “Backpacker tourism helps in preserving Bure [traditional Fijian house] as we are trying to build more Bure in the village in order to educate tourists”.11 These views are supported by several backpackers as Julia (Norwegian, age 29) described:

The locals show their culture everyday especially on the Fijian night12 where Fijian songs, dances, food, and Kava ceremony are presented. I think that is a great way to help preserving their culture.

Regarding backpacker tourism “leads to changes in traditional ways of life amongst indigenous people”, although both respondent groups agreed with this impact, hosts agreed more strongly with this than backpackers. As regards the views of hosts, Vini (resident, age 52) commented: “Our way of dressing has been altered especially amongst the females who work at the resorts as they imitate the tourists in wearing modern dresses”. Further, Sera (resident, age 40) commented:

In the past, we don’t need to buy food as we have our own plantations and we go fishing. But now we are committed to working at the resorts [backpacker resorts] and we are more reliant on the tinned-food [imported from the main island].

Moreover, Simone (governmental official, age 40) commented:

In the past, we don’t need to use money as we use Fijian canoe for transportation and we do planting and go fishing….whenever we need the thing that we don’t have, we just say ‘kere kere’13 to our neighbors and they always give it to us with a good heart; but now these things have been changed.

In respect to the backpackers’ views, Ken (British, age 29) commented: “I saw some locals using mobile phone and brand-named stuffs; the more they were attracted by Western culture, the more they forget their own culture”.

Such narrations tend to suggest that the development of backpacker tourism has created both positive and negative effects on the locals. Their culture and custom are impacted through issues of demonstration effect and commercialization in particular. The former tends to occur with the youth of the community who feel discontented with local opportunities and are willing to copy the tourist lifestyle as a way of searching for the alternatives to their own lifestyles (Murphy, 1985).

The effects of backpacker tourism on values and relationships amongst the locals

Regarding the issue of backpacker tourism “leads to decreases of religious values amongst local people”, while backpackers were neutral in their opinion, hosts agreed with this impact. Like many other hosts, Asena (resident, age 58) described:

In Fiji, we work for six days and Sunday is the day for church. But, nowadays many people here don’t practice this custom as they work [at backpacker resorts] almost every day. Then, they go to work instead of going to church.

Based on the researcher’s observation, there were only a few youth attending the church service as many were employed at backpacker resorts; mostly were children and elderly people who attended the service. Regarding the backpacker views, Henry (Canadian, age 20) reflected: “I am not too sure about this impact but as far as I know Fijians have a strong belief in Christianity”. Further, Nancy (Canadian, age 40) commented: “There is no regulations on taking photos for tourists during the service, especially when the congregation members are emotionally engaged in the ceremony; or they just want a donation and then allow tourists in doing anything”. Nancy’s narration implies that while the host community relies on the tourists’ donation, this may lead to a mitigation of the ceremony’s spirituality and originality (Wall and Mathieson, 2006).

Regarding backpacker tourism “decreases respect of local youth for elders”, whereas backpackers were neutral about this effect, the hosts agreed that there is a decrease in respect to elders amongst the younger generations. As Miri (governmental official, age 42) described: “Nowadays, the youth devalue their own culture, particularly the way they hold respect to elders since they have picked up the Western way of expression [influenced by tourists] and showing it to the elders”. This opinion is affirmed by some elderly people such as Tevita (resident, age 79) who reflected: “When I was young I strictly gave respect to the elders; I had to listen and never talk back to them as this is our custom. Sadly, our new generations do it in another way”.

In respect to backpacker tourism “leads to decreases of family values and unity amongst local people”, whereas the backpackers were neither agreed nor disagreed, the hosts agreed with this impact. Based on the views of hosts, Mariana (resident, age 50) expressed:

The relationship amongst family members are lessening especially between fathers and sons. This happens when the son [who works at the resort] does not give the money to the family (according to Fijian custom). Instead, they spend the wage money in buying Kava and cigarettes.

Further, Emma (resident, age 50) described: “According to our custom, all villagers need to help out on the community-related work. Yet, once tourism started here, working at the resorts is the first priority for the locals whilst the community’s obligations come after. This can lead to a decrease in the cohesion amongst us”.

Such narrations, together with the researcher’s observation, the development of backpacker tourism is shown to cause a lessening of the traditional values amongst the hosts. This is particularly evident on the religious aspect, seniority, and the relationships; both within family and the community. Such development; through the introduction of Western culture, has facilitated an extent of individualism within the host communities where otherwise collectivism is highly appreciated and encouraged.

Part 2: the similarity of host and backpacker perceptions of the socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism

In respect to the impact of backpacker tourism “increases interaction between indigenous local people and tourists”, both hosts and backpackers equally agreed with this effect. As regards the views of hosts, Bill (resort staff, age 40) responded: “Tourists like to talk to us [locals]…We normally share our cultures which help widening my knowledge about the world”. Moreover, Kala (resident, age 50) reflected: “In the past, we only interact amongst ourselves but now we are more socialising with the tourists. Our children love to say ‘Bula [Hi]’ and play with them. This helps our children to speak better English”. This is supported by the views of backpackers as Martin (Israeli, age 32) said: “Most of backpackers are young so we are quite friendly and love to interact with the local people and to learn about their culture”. These narrations appear to support the previous studies (Anderskov, 2002; Aramberri, 1991; Loker, 1993; Richards and Wilson, 2004b; Riley, 1988; Scheyvens, 2002) which noted that backpackers are keen to engage in social interactions with the local people.

Regarding the issue of backpacker tourism “increases casual sex amongst local people”, both hosts and backpackers were neutral in their perception about this. However, there were some respondents from both groups who agreed on this impact. In respect to the view of backpackers, Tony (British, age 28) expressed:

I have seen some female backpackers inviting the resort staff [Fijian boys] to join drinking until late at night and then they went out together to the beach for a sexual purpose; this can lead to an increase in casual sexual preferences among the locals.

This incident is also affirmed by the hosts as Casie (resident, age 32) reflected: “This issue is not only the case between the Fijian boy who works at the resort and the foreign tourist, but also between the locals especially those who work in the resorts”. Further, Luke (governmental official, age 40) said: “There are some locals who have followed tourists’ lifestyles in terms of sexual preferences”. This evidence appears to support previous studies (Berdychevsky et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2009) which noted that backpacking often involves encounters of casual sex. The researcher observed that this problem is exacerbated through tourism and the increased exposure to foreign behaviours. The hosts who work in backpacker resorts have a particularly higher tendency to engage in this issue than others. These findings support the work of Ap (1990) and Carter and Beeton (2004) which noted that tourism leads to increase in sexual permissiveness in host destinations.

Conclusion

Appreciating the influences of the mutual gaze of host and guest perceptions the findings presented in this paper indicate that hosts are more likely to agree that backpackers bring both the positive and negative changes to their socio-cultural sphere. For the positive side, the hosts revealed that backpacker tourism aids in the revitalisation of local cultural practices, particularly the preservation of Bure (traditional Fijian house) and Meke (Fijian dances). Unfortunately, backpackers also bring negative changes to the locals, especially in their dress codes, diet, drinking culture, religious value, and personal relationships (to elders, family and the community). In comparison, the backpackers are generally neutral about their own impact upon to the socio-cultural structure of the host communities but at least do not deny about it. The findings of this research are congruent with previous studies (Canavan, 2013; Holden, 2010; Ismail et al., 2011; Puczkó and Rátz, 2000; Sánchez Cañizares et al., 2015) reported that hosts are more concerned with the socio-cultural effects of tourism than were their guests. However, this paper still makes valuable contribution to the literature in respect to perceptions of locals in the less developed country (Fiji). How they gaze upon tourists (backpackers) who mainly come from highly developed countries and vis-à-vis. While it has its particular focus on the tourist’s socio-cultural impact on host societies in a less developed country, more broadly it addresses the call from Maoz (2006) who suggests the significance of the mutual gaze should not be discounted in further research on host and guest encounters.

Based on the researcher’s observation, there were several cases amongst backpacker respondents who were unsure about the effects of backpacker tourism on the socio-cultural dimension and then subsequently rated their responses as “neither agree nor disagree” on the survey. There were also some respondents who noted on the questionnaire survey: “How would I know answers without seeing any evidence?” Possibly, this could be because most of the backpackers travelled on “Island Hopping Packages14” and typically spent only a few nights at different resorts on the different islands within the Yasawa Group. As such, with the respondents constantly on the move nature of trip, this may have influenced the way of their responses (Uysal et al., 1994). In this respect, it appears to suggest that the quest for authenticity amongst backpackers does not essentially lead them to actively search for deep understanding of the local culture. Rather, many seek instant authenticity through superficial experiences provided in a tour package as evidenced in the Yasawas. This phenomenon supports the assertion of several researchers which claimed that the effort in searching for authenticity has been diminished amongst modern day backpackers (Cohen, 2003; Maoz, 2006; O’Reilly, 2006; Richards and Wilson, 2004b).

This paper significantly contributes to the literature by reducing the current gap that exists regarding the impacts of backpacker tourism on local communities in LDCs as identified by Richards and Wilson (2004a) and Scheyvens (2002). The disparity between the views of hosts and backpackers highlighted in this paper also supports Cohen (2003) who notes that the impact of backpacker tourism is rather problematic and controversial amongst different stakeholders. The effort in assessing the views of both hosts and backpackers of the effects of the latter on destinations is therefore considerably fruitful as they can collectively help planners and policymakers to implement sustainable tourism practices and/or to acquire greater success for destinations. The findings reinforce the assertion of Maoz (2006) who highlighted the significance of “mutual gaze” in LDCs where both local and tourist gazes are rather complicated and vigorous.

The findings derived from this study provide a means to aid destination policymakers to develop solutions and/or actions for reinforcing destination sustainability practices for the Yasawa Islands, Fiji. Furthermore, these findings may be useful for those involved in destination planning and management in other locations. Specifically, in developing minimizing strategies to combat adverse impacts of backpacker tourism and maximizing strategies to harvest the benefits associated with such industry. In particular, the learnings from the Fiji backpacker and host populations’ engagement may serve general tourism interests in other destinations broadly but in less developed countries specifically.

This paper is an attempt to widen the scope of backpacking study through the gaze of host–guest encounters between the backpackers (mostly Westerners) and the indigenous hosts in the less developed country in particular. Within the mainly Western scholarship, this paper acknowledges the significance of indigenous knowledge. It allows the voices; views and concerns regarding the introduction of international tourism, of the indigenous peoples to be heard and hopefully to be resolved. Additionally, this paper affirms the advantages of utilizing a combined quantitative–qualitative approach for tourism impact perception studies to understand “why” individuals perceive the impacts of tourism in certain ways rather than simply measuring what individuals perceive.

This research focused on perceptions of hosts and guest towards the impact of backpacker tourism in a Western society, albeit a less developed country. Further work is needed to examine the issues addressed in this paper in other locations, especially in a less developed Eastern society. Based on Reisinger (1994), the impact of tourism varied considerably based on the degree of cultural differences between hosts and guests; thus future research may generate different findings across different countries established upon the disparity between the Western and Eastern host cultures. Nevertheless, it is argued that future research will be enriched through the continued utilization of the matrix of methods and theory combined in this study. Both quantitative and qualitative techniques were crafted around the gaze theory for both hosts and visitors. This approach will enhance a comprehensive understanding of the perceived impacts of tourism and a more nuanced understanding of the subjects – the “Others”.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the University of Otago, New Zealand, under Doctoral Scholarship; Khon Kaen University, Thailand, under PhD Studying Scholarship for Teacher; and the Department of Tourism, University of Otago, under fieldwork and conference funding.

Endnotes

References

- Allon and Anderson, 2009 F. Allon, K. Anderson Intimate encounters: the embodied transnationalism of backpackers and independent travellers. Popul. Space Place, 16 (1) (2009), pp. 11-22

- Andereck et al., 2005 K.L. Andereck, K.M. Valentine, R.C. Knopf, C.A. Vogt Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tourism Res., 32 (4) (2005), pp. 1056-1076, 10.1016/j.annals.2005.03.001

- Anderskov, 2002 C. Anderskov Backpacker Culture: Meaning and Identity Making Processes in the Backpacker Culture among Backpackers in Central America: Ethnography and Social Anthropology. Arhus University, Denmark (2002)

- Ap, 1990 J. Ap Residents’ perceptions research on the social impacts of tourism. Ann. Tourism Res., 17 (4) (1990), pp. 610-616

- Ap and Crompton, 1998 J. Ap, J.L. Crompton Developing and testing a tourism impact scale. J. Travel Res., 37 (2) (1998), pp. 120-130, 10.1177/004728759803700203

- Aquino, 2015 Aquino, M., 2015. Harsh punishments for drug use in Southeast Asia: Proximity of “Golden Triangle” puts governments on alert against drugs. Retrieved March 10, 2015, from <http://goseasia.about.com/od/travelplanning/a/seasia_drugs.htm>.

- Aramberri, 1991 Aramberri, J., 1991. The nature of youth tourism: Motivations, characteristics and requirements. Paper presented at the International Conference on Youth Tourism, New Delhi. Madrid: World Tourism Organisation.

- Awesome Adventures Fiji, 2011–2012 Awesome Adventures Fiji, 2011–2012. Fiji Islands The Yasawas: For alternative travellers South Sea Cruises’ Ferries. Fiji.

- Aziz, 1999 Aziz, H., 1999. Backpackers in the Sinai Focus, University of North London, Tourism Concern.

- Belisle and Hoy, 1980 F.J. Belisle, D.R. Hoy The perceived impact of tourism by residents a case study in Santa Marta, Colombia. Ann. Tourism Res., 7 (1) (1980), pp. 83-101

- Berdychevsky et al., 2010 L. Berdychevsky, Y. Poria, N. Uriely Casual sex and the backpacking experience: the case of Israeli women. N. Carr, Y. Poria (Eds.), Sex and the Sexual During People’s Leisure and Tourism Experiences, Cambridge Scholars, Newcastle, U.K. (2010), pp. 105-118

- Besculides et al., 2002 A. Besculides, M.E. Lee, P.J. McCormick Residents’ perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism. Ann. Tourism Res., 29 (2) (2002), pp. 303-319

- Bradt, 1995 H. Bradt Better to travel cheaply. Independent Sunday, 12 (1995), pp. 49-50

- Brunt and Courtney, 1999 P. Brunt, P. Courtney Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Ann. Tourism Res., 26 (3) (1999), pp. 493-515

- Bushell and Anderson, 2010 R. Bushell, K. Anderson A clash of cultures or definitions? Complexity and backpacker tourism in residential communities. K. Hannam, A. Diekmann (Eds.), Beyond Backpacker Tourism: Mobilities and Experience, Channelview Publications, UK (2010), pp. 291-303

- Butler, 1980 R.W. Butler The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr., 24 (1) (1980), pp. 5-12, 10.1111/j.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.x

- Butler, 1989 R.W. Butler Alternative tourism: pious hope or Trojan horse?. World Leisure Recreation, 31 (4) (1989), pp. 9-17

- Byrd et al., 2009 E.T. Byrd, H.E. Bosley, M.G. Dronberger Comparisons of stakeholder perceptions of tourism impacts in rural eastern North Carolina. Tourism Manag., 30 (5) (2009), pp. 693-703, 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.10.021

- Canavan, 2013 B. Canavan Send more tourists! Stakeholder perceptions of a tourism industry in late stage decline: the case of the Isle of Man. Int. J. Tourism Res., 15 (2) (2013), pp. 105-121

- Carter and Beeton, 2004 R.W. Carter, R.J.S. Beeton A model of cultural change and tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tourism Res., 9 (4) (2004), pp. 423-442

- Cassell, 2005 Cassell, K., 2005. Fiji: A Visitor’s Guide. March 16, 2014, from <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kava>.

- Cohen, 1972 E. Cohen Toward a sociology of international tourism. Soc. Res., 39 (1) (1972), pp. 164-182

- Cohen, 1982 E. Cohen Marginal paradises: Bungalow tourism on the islands of Southern Thailand. Ann. Tourism Res., 9 (2) (1982), pp. 189-228, 10.1016/0160-7383(82)90046-9

- Cohen, 2003 E. Cohen Backpacking: diversity and change. J. Tourism Cultur. Change, 1 (2) (2003), pp. 95-110, 10.1080/14766820308668162

- Cohen, 2006 E. Cohen Pai-a backpacker enclave in transition. Tourism Recreation Res., 31 (3) (2006), pp. 11-27, 10.1080/02508281.2006.11081502

- Colaabavala, 1974 F. Colaabavala Hippie Dharma. Hind Pocket Books, New Delhi (1974)

- Deery et al., 2012 M. Deery, L. Jago, L. Fredline Rethinking social impacts of tourism research: a new research agenda. Tourism Manag., 33 (1) (2012), pp. 64-73, 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.01.026

- Desforges, 2000 L. Desforges Traveling the world: identity and travel biography. Ann. Tourism Res., 27 (4) (2000), pp. 926-945

- District Office Lautoka/Yasawa, 2011 District Office Lautoka/Yasawa Tikina Nacula Development 2010–2015. Lautoka, Fiji (2011)

- Dodds et al., 2010 R. Dodds, S.R. Graci, M. Holmes Does the tourist care? A comparison of tourists in Koh Phi Phi, Thailand and Gili Trawangan, Indonesia. J. Sustainable Tourism, 18 (2) (2010), pp. 207-222, 10.1080/09669580903215162

- Dowling, 1993 R.K. Dowling Tourist and resident perceptions of the environment-tourism relationship in the Gascoyne Region, Western Australia. GeoJ., 29 (3) (1993), pp. 243-251, 10.1007/BF00807043

- Elsrud, 2001 T. Elsrud Risk creation in traveling: backpacker adventure narration. Ann. Tourism Res., 28 (3) (2001), pp. 597-617, 10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00061-X

- Farrell and Marion, 2001 T.A. Farrell, J.L. Marion Identifying and assessing ecotourism visitor impacts at eight protected areas in Costa Rica and Belize. Environ. Conserv., 28 (3) (2001), pp. 215-225

- Haley et al., 2005 A.J. Haley, T. Snaith, G. Miller The social impacts of tourism a case study of Bath, UK. Ann. Tourism Res., 32 (3) (2005), pp. 647-668, 10.1016/j.annals.2004.10.009

- Hampton, 1998 M.P. Hampton Backpacker tourism and economic development. Ann. Tourism Res., 25 (3) (1998), pp. 639-660, 10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00021-8

- Hampton, 2003 M.P. Hampton Entry points for local tourism in developing countries: evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Geografiska Annaler. Series B Human Geography∗∗, 85 (2) (2003), pp. 85-101, 10.1111/1468-0467.00133

- Hampton, 2009 Hampton, M.P., 2009. Researching backpacker tourism: changing narratives. Retrieved 15 October 2013, from University of Kent <https://kar.kent.ac.uk/23111/>.

- Hampton, 2013 Hampton, M.P., 2013. Backpacker tourism and economic development: perspectives from the less developed world (Vol. 38), Routledge, London, New York.

- Holden, 2010 A. Holden Exploring stakeholders’ perceptions of sustainable tourism development in the Annapurna Conservation Area: issues and challenge. Tourism Hospital. Plan. Dev., 7 (4) (2010), pp. 337-351

- Holdnak et al., 1993 A. Holdnak, E. Drogin, A. Graefe, J. Falk A comparison of residential and visitor attitudes toward experiential impacts, environmental conditions and management strategies on the Delaware Inland Bays. Vis. Leisure Bus., 12 (3) (1993), pp. 11-23

- Hughes et al., 2009 K. Hughes, J. Downing, M.A. Bellis, P. Dillon, J. Copeland The sexual behaviour of British backpackers in Australia. Sex. Transm. Infect., 85 (6) (2009), pp. 477-482

- Ismail et al., 2011 F. Ismail, B. King, R. Ihalanayake Host and guest perceptions of tourism impacts in island settings: a Malaysian perspective. J. Carlsen, R. Butler (Eds.), Island Tourism: Sustainable Perspectives, CABI, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, Cambridge, MA (2011), p. 87

- Jamieson, 1996 K. Jamieson Been there, done that: Identity and the overseas experiences of young pakeha New Zealanders. (Unpublished dissertation, Masters of Arts: Social Anthropology). Massey University, Palmerston (1996)

- Jarvis and Peel, 2010 J. Jarvis, V. Peel Flashpacking in Fiji: reframing the ‘global nomad’ in a developing destination. K. Hannam, A. Diekmann (Eds.), Beyond Backpacker Tourism: Mobilities and experiences, Vol. 21, Channel View Publications (2010), pp. 21-39

- Kavallinis and Pizam, 1994 I. Kavallinis, A. Pizam The environmental impacts of tourism— whose responsibility is it anyway? The case study of Mykonos. J. Travel Res., 33 (2) (1994), pp. 26-32, 10.1177/004728759403300205

- Kerstetter and Bricker, 2009 D. Kerstetter, K. Bricker Exploring Fijian’s sense of place after exposure to tourism development. J. Sustainable Tourism, 17 (6) (2009), pp. 691-708, 10.1080/09669580902999196

- King et al., 1993 B. King, A. Pizam, A. Milman Social impacts of tourism: host perceptions. Ann. Tourism Res., 20 (4) (1993), pp. 650-665

- Kontogeorgopoulos, 2003 N. Kontogeorgopoulos Keeping up with the Joneses: tourists, travellers, and the quest for cultural authenticity in southern Thailand. Tourist Stud., 3 (2) (2003), pp. 171-203

- Kousis, 1989 M. Kousis Tourism and the family in a rural Cretan community. Ann. Tourism Res., 16 (3) (1989), pp. 318-332

- Lankford, 1994 S.V. Lankford Attitudes and perceptions toward tourism and rural regional development. J. Travel Res., 32 (3) (1994), pp. 35-43, 10.1177/004728759403200306

- Loker-Murphy and Pearce, 1995 L. Loker-Murphy, P.L. Pearce Young budget travelers: backpackers in Australia. Ann. Tourism Res., 22 (4) (1995), pp. 819-843, 10.1016/0160-7383(95)00026-0

- Loker, 1993 L. Loker The Backpacker Phenomenon II: More Answers to Further Questions. James Cook University of North Queensland (1993)

- Long et al., 1990 P.T. Long, R.R. Perdue, L. Allen Rural resident tourism perceptions and attitudes by community level of tourism. J. Travel Res., 28 (3) (1990), pp. 3-9

- Lucas, 1979 Lucas, R.C., 1979. Perceptions of non-motorized recreational impacts: a review of research findings. Paper Presented at the Recreational Impact on Wildlands. Conference proceedings October 27–29, 1978.

- Luo et al., 2014 Luo, X., Brown, G., Huang, S., 2014. Resident perceptions of backpackers’ impacts: A case study from Lijiang, China. Paper presented at the CAUTHE 2014: Tourism and Hospitality in the Contemporary World: Trends, Changes and Complexity, Australia: Brisbane; School of Tourism, The University of Queensland.

- Mandalia, 1999 S. Mandalia Getting the hump. Focus, 31 (1999), pp. 16-17

- Manning et al., 2000 R.E. Manning, W. Valliere, B. Minteer, B. Wang, C. Jacobi Crowding in parks and outdoor recreation: a theoretical, empirical, and managerial analysis. J. Park Recreation Admin., 18 (4) (2000), pp. 57-72

- Maoz, 2005 D. Maoz Young adult Israeli backpackers in India. C. Noy, E. Cohen (Eds.), Israeli Backpackers and Their Society: A View from Afar, State University of New York Press, Albany (2005), pp. 159-188

- Maoz, 2006 D. Maoz The mutual gaze. Ann. Tourism Res., 33 (1) (2006), pp. 221-239, 10.1016/j.annals.2005.10.010

- Milman and Pizam, 1988 A. Milman, A. Pizam Social impacts of tourism on central florida. Ann. Tourism Res., 15 (2) (1988), pp. 191-204

- Ministry of Tourism and Environment, 2007 Ministry of Tourism and Environment Regional Tourism Strategy Yasawa Islands: Fiji Tourism Development Plan 2007–2016. Department of Tourism, Sustainable Tourism Development Consortium, Suva, Fiji (2007)

- Moufakkir and Reisinger, 2013 O. Moufakkir, Y. Reisinger The Host Gaze in Global Tourism. CABI (2013)

- Moyle et al., 2012 B.D. Moyle, B. Weiler, G. Croy Visitors’ perceptions of tourism impacts Bruny and Magnetic Islands, Australia. J. Travel Res., 52 (3) (2012), pp. 392-406

- Murphy, 1985 P.E. Murphy Tourism: A Community Approach. Methuen, New York (1985)

- Noronha, 1999 Noronha, F., 1999. Culture shocks. In Focus, Spring, 4–5.

- Nyaupane and Thapa, 2006 G.P. Nyaupane, B. Thapa Perceptions of environmental impacts of tourism: a case study at ACAP, Nepal. Int. J. Sustainable Dev. World Ecol., 13 (1) (2006), pp. 51-61, 10.1080/13504500609469661

- O’Reilly, 2006 C.C. O’Reilly From drifter to gap year tourist: mainstreaming backpacker travel. Ann. Tourism Res., 33 (4) (2006), pp. 998-1017, 10.1016/j.annals.2006.04.002

- Paris and Teye, 2010 C.M. Paris, V. Teye Backpacker motivations: A travel career approach. J. Hospit. Market. Manag., 19 (3) (2010), pp. 244-259

- Petrosillo et al., 2007 I. Petrosillo, G. Zurlini, M.E. Corlianò, N. Zaccarelli, M. Dadamo Tourist perception of recreational environment and management in a marine protected area. Landscape Urban Plan., 79 (1) (2007), pp. 29-37

- Pizam, 1978 A. Pizam Tourism’s impacts: the social costs to the destination community as perceived by its residents. J. Travel Res., 16 (4) (1978), pp. 8-12

- Pizam and Pokela, 1985 A. Pizam, J. Pokela The perceived impacts of casino gambling on a community. Ann. Tourism Res., 12 (2) (1985), pp. 147-165

- Puczkó and Rátz, 2000 L. Puczkó, T. Rátz Tourist and resident perceptions of the physical impacts of tourism at Lake Balaton, Hungary: issues for sustainable tourism management. J. Sustainable Tourism, 8 (6) (2000), pp. 458-478, 10.1080/09669580008667380

- Ravuvu, 1983 Ravuvu, A., 1983. Vaka i Taukei: The Fijian Way of Life, Institute of Pacific Studies of the University of the South Pacific.

- Reisinger, 1994 Reisinger, Y., 1994. Social contact between tourists and hosts of different cultural backgrounds. SEATON, AV Tourism: state of art, Wiley, London, pp. 743–754.

- Richards and Wilson, 2004a G. Richards, J. Wilson Travel Writers and Writers who Travel: Nomadic Icons for the Backpacker Subculture?. J. Tourism Cultur. Change, 2 (1) (2004), pp. 46-68

- Richards and Wilson, 2004b G. Richards, J. Wilson The global nomad: motivations and behaviour of independent travellers worldwide. G. Richards, J. Wilson (Eds.), The Global Nomad: Backpacker Travel in Theory and Practice, Channel View Publications, Clevedon (2004), pp. 14-39

- Riley, 1988 P.J. Riley Road culture of international long-term budget travelers. Ann. Tourism Res., 15 (3) (1988), pp. 313-328

- Sánchez Cañizares et al., 2015 S.M. Sánchez Cañizares, A.M. Castillo Canalejo, J.M. Núñez Tabales Stakeholders’ perceptions of tourism development in Cape Verde, Africa. Curr. Issues Tourism (2015), pp. 1-15. (ahead-of-print)

- Saremba and Gill, 1991 J. Saremba, A. Gill Value conflicts in mountain park settings. Ann. Tourism Res., 18 (3) (1991), pp. 455-472, 10.1016/0160-7383(91)90052-D

- Scheyvens, 2002 R. Scheyvens Backpacker tourism and Third World development. Ann. Tourism Res., 29 (1) (2002), pp. 144-164, 10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00030-5

- Scheyvens, 2006 R. Scheyvens Sun, sand, and beach fale: benefiting from backpackers-the Samoan way. Tourism Recreation Res., 31 (3) (2006), pp. 75-86, 10.1080/02508281.2006.11081507

- Scheyvens and Russell, 2012 R. Scheyvens, M. Russell Tourism and poverty alleviation in Fiji: comparing the impacts of small-and large-scale tourism enterprises. J. Sustainable Tourism, 20 (3) (2012), pp. 417-436, 10.1080/09669582.2011.629049

- Shah and Gupta, 2000 Shah, K., Gupta, V., 2000. Tourism, the poor and other stakeholders: Experience in Asia. (0850034590). from Overseas Development Institute and Tourism Concern <http://dirp4.pids.gov.ph/popn_pub/tourism_asia.pdf>.

- Simpson, 1999 F. Simpson Tourist impact in the historic centre of Prague: resident and visitor perceptions of the historic built environment. Geogr. J., 165 (2) (1999), pp. 173-183, 10.2307/3060415

- Sørensen, 2003 A. Sørensen Backpacker ethnography. Ann. Tourism Res., 30 (4) (2003), pp. 847-867, 10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00063-X

- Speed, 2008 C. Speed Are backpackers ethical tourists?. K. Hannam, I. Atelievic (Eds.), Backpacker Tourism: Concepts and Profiles, Channel View Publications, Clevedon (2008), pp. 54-81

- Spreitzhofer, 1998 G. Spreitzhofer Backpacking tourism in south-east Asia. Ann. Tourism Res., 25 (1998), pp. 978-983

- Sroypetch, 2015 Sroypetch, S., 2015. Host and guest perceptions of backpacker tourism impacts on local communities: a case study of the Yasawa group of Islands, Fiji. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.

- Suntikul, 2007 W. Suntikul The effects of tourism development on indigenous populations in Luang Namtha Province, Laos. R. Butler, T. Hinch (Eds.), Tourism and Indigenous Peoples: Issues and Implications, Elsevier, Butterworth-Heinemann (2007), pp. 128-140

- Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009 C. Teddlie, A. Tashakkori Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. SAGE Publications, Los Angeles (2009)

- Tourism Fiji, 2011 Tourism Fiji, 2011. Fiji records best ever international visitor arrival result. Retrieved Febuary 20, 2012, from <http://www.fijime.com/latestnews/march2011/index.html>.

- Uriely et al., 2002 N. Uriely, Y. Yonay, D. Simchai Backpacking experiences: a type and form analysis. Ann. Tourism Res., 29 (2) (2002), pp. 520-538

- Uysal et al., 1994 M. Uysal, C. Jurowski, F.P. Noe, C.D. McDonald Environmental attitude by trip and visitor characteristics: US Virgin Islands National Park. Tourism Manag., 15 (4) (1994), pp. 284-294

- Van Winkle and MacKay, 2008 C.M. Van Winkle, K.J. MacKay Self-serving bias in visitors’ perceptions of the impacts of tourism. J. Leisure Res., 40 (1) (2008), pp. 69-89

- Vava, 1999 Vava, 1999. Zipolite Mexico. Retrieved November 14, 2014, from <http://www.greatvavavoom.com/stories/storyReader$56>.

- Vinodcia, 2011 Vinodci Drugs, Goa: Refrain from these Activities! [VirtualTourist Post discussion group]. Retrieved from http://www.virtualtourist.com/travel/Asia/India/Goa-1098247/Warnings_or_Dangers-Goa-DRUGS-BR-1.html (2011)

- Visser, 2003 G. Visser The local development impacts of backpacker tourism: evidence from the South African experience. Urban Forum, 14 (2) (2003), pp. 264-293, 10.1007/s12132-003-0014-9

- Visser, 2004 G. Visser The developmental impacts of backpacker tourism in South Africa. GeoJ., 60 (3) (2004), pp. 283-299, 10.1023/B:GEJO.0000034735.26184.ae

- Wall and Mathieson, 2006 G. Wall, A. Mathieson Tourism: Change, Impacts, and Opportunities. (second ed.), Pearson Education, Harlow, Eng.; New York (2006)

- Wang et al., 2006 Wang, S., Fu, Y.-Y., Cecil, A.K., Avgoustis, S.H., 2006. Residents’ perceptions of cultural tourism and quality of life-A longitudinal approach. Tourism Today Tourism Today.

- Weaver and Lawton, 2001 D. Weaver, L. Lawton Resident perceptions in the urban-rural fringe. Ann. Tourism Res., 28 (2) (2001), pp. 439-458, 10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00052-9

- Welk, 2004 P. Welk The beaten track: anti-tourism as an element of backpacker identity construction. G. Richards, J. Wilson (Eds.), The Global Nomad: Backpacker Travel in Theory and Practice, Channel View Publications, Clevedon (2004), pp. 77-91

- Wheeller, 1991 B. Wheeller Tourism’s troubled times: responsible tourism is not the answer. Tourism Manag., 12 (2) (1991), pp. 91-96, 10.1016/0261-5177(91)90062-X

- Wilson, 1997 D. Wilson Paradoxes of tourism in Goa. Ann. Tourism Res., 24 (1) (1997), pp. 52-75, 10.1016/S0160-7383(96)00051-5

- Woosnam, 2011 K.M. Woosnam Using emotional solidarity to explain residents’ attitudes about tourism and tourism development. J. Travel Res., 51 (3) (2011), pp. 315-327, 10.1177/0047287511410351

- Young, 2005 T. Young Between a rock and a hard place: backpackers at Uluru. B. West (Ed.), Down the Road: Exploring Backpacker and Independent Travel, Curtin University of Technology (2005), pp. 33-56

- Young and Lyons, 2010 T. Young, K. Lyons ’I travel because I want to learnEllipsis’: backpackers and the conduits of cultural learning. Lifelong Learn. Europe, 15 (3) (2010), pp. 150-158

- Zhang et al., 2006 J. Zhang, R.J. Inbakaran, M.S. Jackson Understanding community attitudes towards tourism and host—Guest interaction in the urban—rural border region. Tourism Geogr., 8 (2) (2006), pp. 182-204, 10.1080/14616680600585455