‘Knot-working’ of traditional music across the globe: A case study of African drumming in Ioujima Island, Japan

Faculty of Law, Economics and Humanities, Kagoshima University, Japan satoru@leh.kagoshima-u.ac.jp

Abstract

The paper explains how a West African drum called djembe has been introduced and settled in Ioujima, a small island in Kagoshima, Japan. The drum and its music were brought in the island by Mamady Keita, who is a world famous djembe drummer from Guinea, in 1990’s. There has been established an international djembe school named ‘Mishima Djembe School’ in the island, and it attracts the musicians domestically and internationally. The music is contributing to revitalize the depopulating and aging island community.

There are several reasons why the island has accepted the music from opposite side of the earth and the music has become an important part of the islanders both culturally and economically. One reason relates to the unique history of djembe music. Another reason is the way the island has accepted and made the best use of the cultural resource to vitalize its social-economy. The events regarding djembe in the island used to be solely managed by the municipal office. However, the music became a joint project of the municipality and a music-related company. What the two stories explain is that transformation from ‘net-working’ to ‘knot-working’ has happened in the music and the islanders’ way of accepting it.

Keywords

West Africa, Ioujima, Djembe, Knot-working, Net-working

Introduction

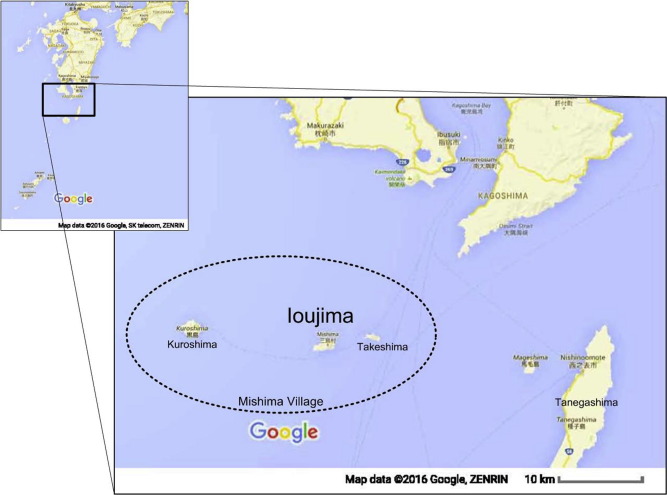

Most of the remote islands in Japan have severe social-economic problems caused by decreasing and aging population. The islanders are struggling to solve the issue. One possible way is to make the use of cultural power such as music, arts and sports. There have already been several successful cases. The paper explains how a West African drum called djembe has been introduced and settled in Ioujima, a small island in Kagoshima, Japan (Fig. 1). The paper tries to figure out the process of success with an approach of ‘knot-working’.

Ioujima is located 110 km south of Kagoshima city. Along with Takeshima and Kuroshima, it makes up Mishima village which literally means ‘three islands village’. The area of the island is 11.65 square kilometers. Its length is 5.5 km from east to west and 4.0 km from north to south.

The paper firstly explains how djembe was accepted and became an important icon in the island focusing on the history. It secondly discusses why djembe, a traditional West African drum, was successful in contributing to the development of the island focusing on the process of nationalization and globalization of djembe and its ensemble music. It finally analyzes the reason behind its success history using the concept of ‘knot-working’.

How djembe music was accepted in a small Japanese island?

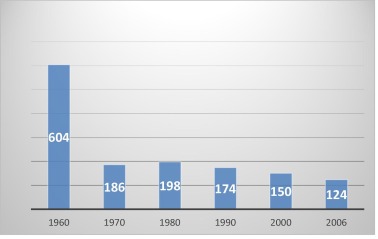

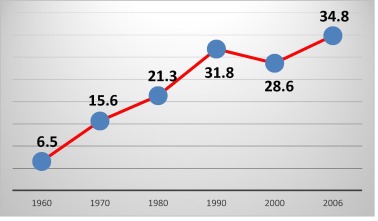

Ioujima used to be much more populated when there was a mining industry since 1868–1964. According to the village web site, its population in 1960 was 604 compared to 124 in 2006 as Fig. 2 shows (Website of Mishima village, 2016). During the period of rapid economic growth in Japan, Yamaha Resort built a resort hotel named ‘Ryoso Ashizuri’ in the island. However, it was closed in 1983. Thanks to the resort hotel, the population was slightly increased from 1970 to 1980 as Fig. 2 shows (Website of Mishima village, 2016). Since then until mid-2000’s, the population has been continuously decreasing. Aging population is also a serious problem as well as decreasing population in the island. The percentage of the population over 65 was only 6.5% and that in 2006 jumped to 34.8% as Fig. 3 (Website of Mishima village, 2016) shows. The economy of the island used to be dependent on and driven by the capitals outside the island. The islanders were forced to figure out their own way of economic development. Since 1990, the municipal government of Mishima village started to utilize culture and sports to attract immigrants and tourists. It started a yacht race named ‘Mishima Cup’ in 1990 which has been held once a year in summer until this year. In 1994, it invited Mamady Keita, who is a world famous djembe player, and his band ‘Sewakan’. He came to Ioujima to teach the children in Mishima village how to play djembe. He is coming to the island almost every year. There also held kabuki shows in the island at the natural rock stage beside the sea in 1996 and 2011. The shows were performed by Kankuro, who is one the most famous kabuki actors in Japan. Although all the three islands are involved in the events, Ioujima plays the most important role especially in the yacht races and djembe relating activities, for the events are mainly held in the island. Thus the municipality government put an enormous effort to revitalize the islands on their own. The change of island development direction may be described as dual paradigm shifts in terms of initiatives and focuses. One is the shift of the initiative in the development from the off-islands capitals such as a mining cooperation and a tourism company to the islanders. Another is the shift of focus in the development from mining and a large scale tourism to a small scale cultural based development.

Among these three new drives based on culture in islands development, or yacht race, djembe, and kabuki, djembe is contributing most to vitalize the economy and society in the island as I describe later. When I illustrate the history of djembe in the island, I need to talk about two key persons, Mamady Keita and Kenichiro Tokuda who has contributed a lot so that the islanders understand and accept the drum music. When Mamady Keita came to the island in 1994, Mr. Tokuda was a young employee of Mishima village municipality hall. He and other young stuffs worked so hard to prepare to invite Mamady and his band, they also begun to learn djembe. They learnt the music to teach the children in the village while Mamady is out of the village. Mamady liked the island and continued to come back. After several visits of Mamady to the island, he admired the talent of Mr. Tokuda and he became the main player in most of the events regarding djembe. Several children, Mr. Tokuda and others in Mishima village visited Mamady’s village in Guinee to learn the culture of the music in 1999. Mamady taught the children djembe because he wanted them to respect their own culture. He tried to do so by showing them how deeply he loves djembe, which is his tribal music.

The relationship between Mamady and Mishima village developed enough to build ‘Mishima Djembe School’ and Mr. Tokuda became the first principal of the school in 2004. In 2014, Mr. Tokuda retired the Mishima village municipality hall and became an independent musician, and he established his own music healing company named ‘Sound Hill’ in Kagoshima city. He is continuing to be a principal and supporting the school.

Now, djembe is one of the most important drives to revitalize the island and its village. Djembe is also an icon of the island and its village. The island and other two islands in the village are regularly inviting elementary and secondly students to study in the island away from their parents for a year or more. The program is named as ‘shiokaze ryugaku’, which literally means ‘study in the islands with sea breeze’. And the said drum school has a program for African drum lovers to stay in the island for short and middle term stay (6 months). Thanks to djembe, one can see young people in the island. If you try to understand why djembe became a successful cultural resource to revitalize the island and its village, you need to comprehend how djembe evolved so that it can be accepted in a remote island with a different culture on one hand. You also need to understand how the relationship of the organizations and people relating to djembe has evolved.

Why djembe?

When you try to understand why djembe was settled down and became an important part of the island and its village, you need to figure out the process how the traditional West African music has evolved. There are several literatures mainly for drummers who want to learn both the technique to play and the cultural background such as Famadou and Thomas (1997) and Keita (2009). The music used to be basically played only by each tribe. And each rhythm used be played for a specific occasion or ritual such as cultivation and circumcision.

Eric (1996) describes djembe from the cultural and political points of view. It was Sekou Toure, the first president of Guinea, who transformed the traditional style. He used the music for both consolidating the national unity and advertising the new nation globally. He combined the different rhythms of various tribe and formed a ballet troop by bringing together the talented musicians and dancers all over the nation. Thus, Sekou Toure used the music for building and strengthening nationalism in Guinea. They played in a limited hours of live performance with various rhythms so that they can perform in a concert hall. The ballet played all over the world and won a lot of fans. The number of djembe players who were not from West Africa had also increased greatly thanks to the popularity of the ballet troop.

The way of teaching djembe with music notes in a Western style was also invented and became popular globally. This nationalization and globalization of the traditional music are one of the reasons why the music is now gaining the popularity. When the music was brought to Ioujima, the music was ready to penetrate in the places which are very different culturally from the original places in West Africa. The traditional music has travelled across the globe from West Africa to a small island in Japan.

Dual ‘knot-workings’

What is happening in the island can be described as ‘knot-working of an African traditional music’. Knot-working is the concept developed by Engeström (2010). He analyzes the formation and development of work teams as the works themselves change. He writes that a work team consisted of several organizations with a fixed center is being replaced by that of a fluid and flexible form whose center constantly change. He calls the team work as ‘knot-working’ where each organization sometimes connects to another, or ‘knot’ and unlace it in other times depending on the given situation. The organization which command or manage the whole team can be different time to time. In the book, he explains that transformation of work-style from ‘net-working’ to ‘knot-working’ is taking place at present due to IT technologies and globalization.

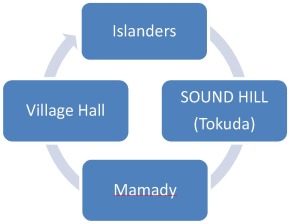

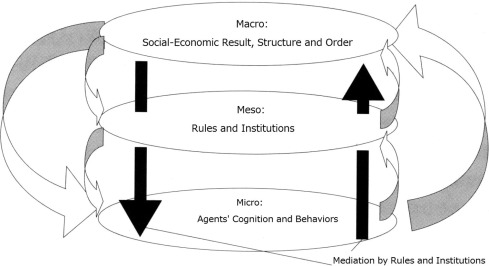

It seems that there happening or emerging dual ‘knot-workings’ in the process djembe became a successful tool in rehabilitating the island and the village community. One ‘knot-working’ is taking place in the djembe music itself. It used be played by each tribe on the specific occasions. The players and listeners used be covered by an ethnic ‘net’. But the networking was transformed to the loosely connected ‘knot-work’ where the players are from different tribe and the listeners are from all over the world. The rhythm played is not strictly connected with rituals and other occasions. Another knot-working is the ‘djembe project’ in the island and its village. All activities relating to djembe used to be initiated and managed by the municipality. Fig. 4 is the image of the net-working in the past. However, the present situation is a collaboration of the municipality and Sound Hill, which is a company of Mr. Tokuda, even though the members involved are overlapped. The municipality hall sometimes connect the ‘knot’ with Mamady. Sound Hill does in other times. Fig. 5 is the image of knot-working. Sometimes the village hall plays the central part, Sound Hill does in other times. The loosely connected set of organizations and people seem to be working well in the djembe project. Thus, the project in Ioujima has been made sustainable thanks to the dual ‘knot-workings’.

Conclusion: agent, rule and outcome

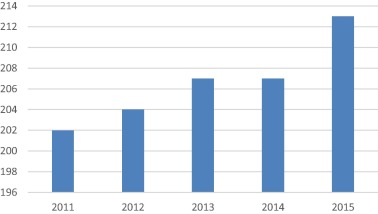

When I summarize the history of djembe and the island which is more than 20 years, I can explain it borrowing the discussion by the Japanese Evolutionary Economics Association (Egashira et. al., 2010). Fig. 6 shows the basic concept of the discussion on the model of ‘micro–macro loop’. The economic agent or a ‘micro’ affects the economic rules and the economic outcome or ‘macro’ will be brought around. Vis-vasa, the performance of outcome affects the rules and behavior of the economic agent. The loop is basically stable with a little bit of fluctuations. However, when the economic circumstances change largely and suddenly, the loop will change. In other word, the behavior of the agents and the rules will change. In Ioujima, there was a serious impact both 1968 and 1983, when the external capital left the island. Many islanders went out of the island and the population started to decrease. In the face of the problem, the islanders and the village hall made the best use of the remote island acts which added culture and other new areas besides infrastructure building. The villagers, or ‘micro, were open and elaborate enough to try different kinds of culture to rehabilitate the village. The ‘macro’, or the outcome was successful in inviting young people to the islands village. The population in Mishima village has been increasing in the last five years as Fig. 7 illustrates (Website of Mishima village, 2016). The Mishima village web page said that they temporally closed the page of immigrants relations section due to excess number of applicants. They definitely came up with a positive loop. As discussed above, the positive loop circulation may not be brought around without the ‘dual knot-workings’.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the support and generosity of Kenichiro Tokuda and the employees in Mishima-mura municipality office without which the present study could not have been completed.

References

- Egashira et al., 2010 S. Egashira, N. Watabe, F. Hashimoto, T. Nishimbe, M. Yoshida (Eds.), Shinka Keizai no Kiso (in Japanese), Nihon Hyoron Syuppannsya (2010)

- Engestroem, 2010 Yrjoe Engestroem From Teams to Knots: Activity-Theoretical Studies of Collaboration and Learning at Work (Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive and Computational Perspectives. Cambridge University Press (2010)

- Eric, 1996 Charry Eric A guide to the Jembe. Percussive Notes, 34 (2) (1996). (http://echarry.web.wesleyan.edu/jembearticle/article.html)

- Famadou and Thomas, 1997 Konate Famadou, Ott Thomas Rythmen und Lieder aus Guinea. Institute fur Didaktik popularer Musik (1997)

- Keita, 2009 Mamady Keita A Life for the Djembe. Book & CD. AFDJ (2009)

- Website of Mishima village, 2016 Website of Mishima village (in Japanese) (31.03.16). http://mishimamura.com.