Ecotourism and World Natural Heritage: Its influence on islands in Japan

Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Kagoshima University, Japan

Faculty of Law, Economics and Humanities, Kagoshima University, Japan kuwahara@leh.kagoshima-u.ac.jp

Abstract

The article discusses the influence of World Natural Heritage registration on ecotourism by looking at the cases of Yakushima as the first World Natural Heritage site and Ogasawara as an advanced region of ecotourism in Japan, and also the Amami Islands and Iriomote Islands where various efforts have been taken toward the registration of World Natural Heritage.

Keywords

Ecotourism Yakushima Ogasawara Iriomotejima Amami Oshima World Natural Heritage

Introduction

Ecotourism in Japan started for the first time in the Ogasawara Islands as a form of whale watching in 1988, and was introduced further into Japan in the 1990s. In 1991, a survey on resources for ecotourism undertaken by the Ministry of the Environment was the first approach that took up ecotourism as a national initiative (Kaizu, 2008: 91). While ecotourism in foreign countries had its background in the Stockholm conference of 1972 and/or sustainable development theory, in Japan it was introduced with the aim of regional development and/or the promotion of natural experiences (ibid: 91). Further, Japanese ecotourism has been deeply related with World Natural Heritage, thus, in the registered or candidate areas for World Natural Heritage, aspects of regional development and environmental protection have often been the focus of the argument.

The Ministry of Environment chose five areas (Shiretoko, Tateyama, Okunikko, Hachijojima and Yakushima) as a model area and initiated research on the promotion of nature-experience activities. The Ministry made specific proposals such as utilization and promotion, and the improvement of facilities according to each area’s actual condition to make it possible to have guided tours such as the observation of wild animals in nature parks and experiences that bring people into contact with nature.

The two-year survey by the Ministry of the Environment clarified that a way to balance regional development with the preservation of the natural environment was absolutely necessary for the proper promotion of nature experience activities. As one of its points, the survey focused on ecotourism and studied the conditions and directions for its domestic promotion.1

In this way, the Japanese approach to ecotourism that is different from overseas is connected to World Natural Heritage and shows a further development. Yakushima Island, where the first World Natural Heritage site in Japan was registered in 1993, shows a very successful case of ecotourism not only domestically but also globally, and thus it can be seen that Japanese ecotourism has a strong tendency to utilize the name value found with World Natural Heritage.

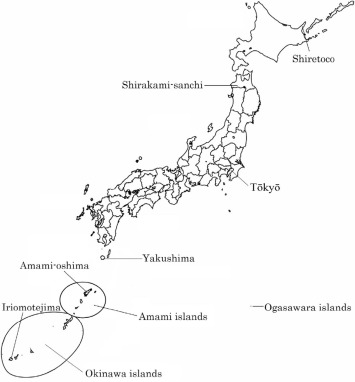

Currently, Japanese World Natural Heritage sites that are registered by UNESCO comprise four areas, that is, Yakushima (1993), Shirakami-sanchi (1993), Shiretoko (2005) and the Ogasawara Islands (2011). The candidate locations are Amami-Oshima, Tokunoshima Island, Yanbaru area of northern Okinawa Island and Iriomotejima Island (Fig. 1).

From the above description, we can see that Japanese ecotourism started from islands, and the ratio of island areas as World Natural Heritage sites is high. In this study, we look at Amami Oshima together with the other three islands that are advanced regions for ecotourism and discuss ecotourism in relation to World Natural Heritage. That is, how ecotourism and World Natural Heritage started in each island, and how such move affected each island. Finally, we will discuss the issues and prospects of the “Amami-Ryukyu” World Natural Heritage candidate site from the viewpoint of the registered World Natural Heritage areas. Our paper is based on data collected during our own fieldwork in Amami Oshima, and from earlier studies on Yakushima, Ogasawara and Iriomotejima.

Ecotourism promoted by World Natural Heritage registration

Ogasawara Islands

The first commercial whale watching in Japan was in Hahajima in the Ogasawara Islands in the year of 20th anniversary in 1988 of Ogasawara’s reversion to Japanese administration in 1968. Members of the Ogasawara Commerce and Industry administration made an inspection of whale watching in Maui Island of Hawai’i as part of a regional development project and this created an opportunity for initiating whale watching in the Ogasawara Islands.2

Historically, the Ogasawara Islands were known as uninhabited islands until 1830. Around that time, whaling was very popular in Europe and the United States. In Ogasawara, Chichijima’s Futami Bay was a natural port and attracted westerners to stay as a supply base of fuel and water for whaling ships (Morita, 1999: 42). Since then, the Ogasawara Islands have had a long history of whaling, which had been practiced in the coastal waters until just before whale watching was started in 1988. However, it was said that Ogasawara people felt bewilderment in realizing that whales had suddenly become an object of watching (Morita, 1999: 42–43, Ishihara et al., 2010: 12–13).

Meanwhile, a new approach to whale watching made steady progress, and the Ogasawara Whale Watching Association was established in 1989. Some researchers also belonged to the Association and engaged in whale research that was entrusted to the Ogasawara Village administration. Self-imposed rules for whale watching were made in 1992, and the 4th International Conference for Dolphins and Whales was held in 1994.3 Thus, the Association was established not only for receiving tourists, but also for playing a role as a research organization (Morita, 1999: 43).

Whales, which had long been the object of catching were utilized as a tourism resource, and Ogasawara’s tourism business saw a great turning point. “Promotion for Ecotourism” was decided as one of the basic policies for the tourism promotion plan for islands in 2000, and full scale efforts were undertaken. The purpose of Ogasawara’s ecotourism is clearly stated in the basic policies. That is, for tourists to get to know the history and culture of Ogasawara which were nurtured by nature, and for the islanders to develop the islands to live well while protecting the irreplaceable nature of the Ogasawara Islands (Zaidan Hojin Nihon Kotsu Kosha, 2005: 1). To realize the above goals, Ogasawara Ecotourism Promotion Committee was established in June 2002.

In May 2003, the Ogasawara Islands became a candidate site for World Natural Heritage together with Shiretoko and the Ryukyu Islands4 in the review meeting set up by the Ministry of Environment.5 By this time, the decrease of endemic and rare species by invasive species and the deterioration of the natural environment were known and the Ministry started the “Promotion Plan for Nature Regeneration of Ogasawara” (Suzuki, 2010). Since an oceanic island such as Ogasawara is vulnerable to invasive species, the concept of World Natural Heritage was introduced as a way to protect the unique ecological system of Ogasawara, and an attempt for registration was initiated (ibid).

On the other hand, the idea and practice of Ogasawara’s ecotourism was introduced and promoted by the Tokyo Metropolitan government with a top-down policy (Ishihara et al., 2010). At the initial stage, the promotion of Ogasawara’s ecotourism was advocated by the Tokyo Metropolitan government (Nakai, 2002). However, considering the fact that the Whale Watching Association was established before that, ecotourism in Ogasawara has been well-balanced in private and public sectors compared with the other ecotourism promoting areas and World Natural Heritage sites. For example, the Ogasawara Tourism Association lay down self-imposed rules for the touristic use of Minamijima Island in 2000, and required tourists to be accompanied by a guide (Ishihara et al., 2010). The Tokyo Metropolitan government concluded an agreement with Ogasawara on “Tokyo Government version ecotourism”, thus, the training program and preparation of rules for registered guides were initiated by the Tokyo Metropolitan government in 2002 (Suzuki, 2010). However, self-imposed rules were limited mostly to specific animal and plant species that were clearly visible to tourists (ibid). In 2005, the Ogasawara Ecotourism Association was established with 16 organizations (Akiyama, 2008), and from 2011, with the Ogasawara land area guide registry system, 23 registered guides were engaged in the business by April 2015.

The Ministry of Environment put effort into organizing an environmental database and promoted the dissemination and enlightenment for the prevention of the spread of alien species by information disclosure. The Tokyo Metropolitan government conducted the monitoring research of Ogasawara’s Minamijima from 2000, and started a revegetation project (Zaidan Hojin Nihon Kotsu Kosha, 2005: 9–11). Suzuki (2010) points out that the movement that aimed at registration for World Natural Heritage was activated as a means to protect the unique ecosystem of Ogasawara. On the other hand, Ishihara et al. (2010) says that Ogasawara aimed for registration as World Natural Heritage by introducing ecotourism as a means for regional development. Also, on the idea and practice of ecotourism, Ishihara et al. state that ecotourism on Minamijima Island was led by the Tokyo Metropolitan government consistently from the beginning (ibid: 14).

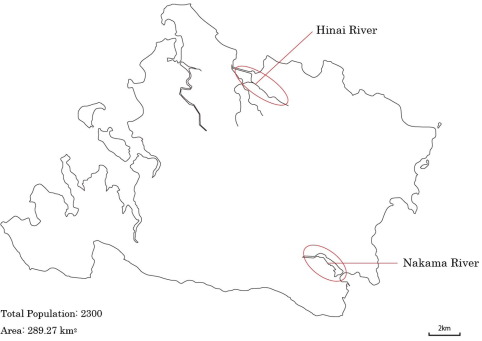

In 2000, the Ogasawara Tourism Association set up a “self-imposed rule” for the tourism use of Minamijima Island, which is located south of Chichijima Island (Fig. 2), and obligated tourists to accompany a guide, and to specify the nature of the observation. In the background of its introduction, there was a governor’s statement at the press conference where it was mentioned that there was a possibility of a ban to enter the island as a conservation measure after the governor had inspected the island and saw the destruction of vegetation. In the aftermath, setting up the rules was made (ibid: 14). However, the reason that the Ogasawara Tourism Association set up the self-imposed rules seems to be not confined to the above remarks.

In 1996, the Ogasawara village administration and Nature Conservation Society of Japan conducted collaborate research on the measures for tourism of Minamijima Island, and made rules for the use of the island. Also, they conducted an enlightenment activity and made a proposal for recovering vegetation and monitoring. The self-imposed rules were said to be made by being based on the above research (Ichinoki and Shumiya, 2007: 76, Nakai, 2002: 37).

The self-imposed rules for tourism were set up by Ogasawara Village in 2001, and at the time there was a ban on entering Minamijima Island outside the maximum number of permitted tourist per day (one hundred tourists), the number of tourist per guide, and the time for entering the island (two hours) (Ichinoki and Shumiya, 2007: 76). The following year, the Tokyo Metropolitan government concluded an agreement of “Metropolitan Tokyo version ecotourism” with Ogasawara Village, and the training of Tokyo Metropolitan Nature guides and upgrading of clear rules were made with this agreement.

The roles of certified guides were to make a commentary for a better understanding of nature and to guide tourists to keep to the rules (ibid 2007: 76). Suzuki points out that the self-imposed rules, except those for Minamijima Island, were mostly confined to certain species of plants and animals, and did not reach out to tourists or the scientific community (Suzuki, 2010: 63).

In 2005, seventeen organizations, including administrative agencies and civilian organizations that relate to Ogasawara, set up an “Ogasawara Ecotourism Meeting” to promote ecotourism. On 29th January 2007, Ogasawara was registered to the provisional list of World Natural Heritage as a candidate site. On 24th June 2011, Ogasawara’s registration into the World Natural Heritage list was decided and the Ogasawara Islands became the fourth World Natural Heritage site in Japan.

Iriomotejima Island

Iriomotejima Island in Okinawa prefecture is the place where ecotourism was first introduced in Japan. The Environment Agency (Current Ministry of the Environment) conducted research called “The Research on Investigating the Measures for Promoting Tourism Use such as Ecotourism in Okinawa”, which aimed to propose an idea for ecotourism in Iriomotejima Island.6

Iriomote Island’ s tourism at that time was showing an increase in the number of tourists as a result of nationwide diving “booms” since the mid-1980s. The number of those who immigrated to the island to run diving shops was increasing according to its demand (Sato, 2008: 28). On the other hand, there were local people who were critical of such tourism. The Association for Digging up Iriomotejima Island, which started in 1985, was set up by young people of the islands who had been acting to revitalize the island from the 1970s together with those researchers who were involved with the Iriomotejima Islands. They recognized that for the people of Iriomotejima Island, the aim to live independently without relying on large companies was to promote ecotourism (Ishigaki, 2000: 55). Thus, the members of the Association for Digging up Iriomotejima Island and those researchers who were involved in the Research on the Measures for Promoting the Experience of Activities in a Natural Environment by Environmental Agency held a discussion on ecotourism. This became a direct opportunity for the establishment of the Iriomotejima Island Ecotourism Association in 1996 (Matsutaka, 1998: 20, Sato, 2008: 29).

Here, we take up the case of the use of nature in Iriomotejima Island tourism in the 1990s, and examine how it was actually related to ecotourism. The most well known nature related tourism of Iriomotejima Island is the river canoe experience, and it started spreading from the early to mid 1990s. Yanagida (2012) sees that the opportunity of the spread is related to the establishment of the Iriomotejima Island Ecotourism Association. As part of the initial business, people agreed to the promotion of eco-tours and developed tour programs accordingly (ibid: 118). However, in the early 2000s, some new tourism businesses were not necessarily intended to do ecotourism, but tended to relate to their own interpretation of tourism. Yanagida pointed out as the cause the weakening influence of the association on the canoe business people (ibid: 121). A new organizational move that was associated with the increase of canoes tourisms seems to be related to that weakening influence.

The Hinai River basin is the most popular place for canoe tourism and it was designated as a national forest and its use for commercial purposes was prohibited (Fig. 3). However, the area was converted into a Natural Recreation Forest because of the continuous increase in users by the commercial activities of canoe tourist agents. The Forestry Agency asked them to organize a major management body of this area and, thus, the Iriomote Canoe Union was established as an independent organization in 1999. The union tried to reduce environmental loading and to share profits among the canoe agents, and made a regulation that allowed seven tourists per guide, twice a day, and up to fourteen tourists (Yanagida, 2012: 121). Yanagida points out that the number restriction per canoe agent cannot suppress an increase of visitors when the number of canoe agents themselves increased and that the rule should be revised (ibid: 123). There are multiple cases of similar environmental issues at times of tour “booms”. According to Okuda (2007), the main reason for this is because some administrators, researchers and environmental education agents strongly pushed the promotive activities of ecotourism. Okuda even says that the current situation has become a cause of environmental destruction (ibid: 85).

While there is successive criticism of this, the progress of Iriomotejima Island went well from the viewpoint of the Environment Agency. In 1994, the Guidebook of Iriomotejima Ecotourism was published, and the next year, the Iriomotejima Wildlife Conservation Center was established. Since then, various promotion projects such as lecture meetings and monitoring tours were held one after another, and Iriomotejima was positioned as a model area for ecotourism.

Ecotourism as a product of World Natural Heritage

Yakushima Island

Yakushima is an island with 90% of its total land area as forest, out of which about 80% is national forest.7 Historically Yakushima’s cedar, called Yakusugi, was found in the deep mountain areas and was the object of worship, and people used the trees of domestic woodlands for their daily life (Haraguchi, 1996: 40).

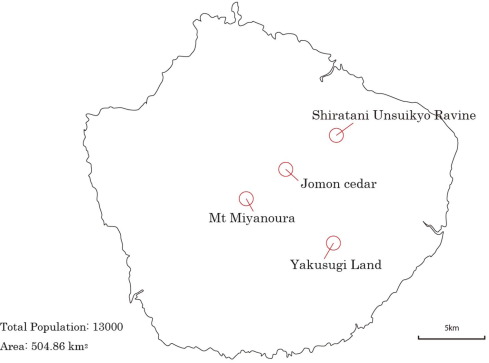

From the middle of the Edo period (mid-18th century), Yakusugi was paid as an annual tribute to the Satsuma domain, and thus full-scale logging began on a large scale (Kanetaka and Karolin, 2011: 68). Since the Meiji era, forestry was initiated. After the Second World War, Yakushima experienced a flowering of its timber industry during a time of high economic growth. However, in the 1970s, there was a change in governmental forestry policy with a shift toward the protection of nature and national land conservation. Yakusugi Land and Shiratani Unsuikyo were set up as natural recreation forests (Fig. 4). Thus, there could be seen a move toward the use of forest resources as a tourism resource (Kichira et al., 1998: 33; Nakashima, 1998; Kanetaka and Karolin, 2011).

When forestry was thriving, most of Yakusima’s forestry officers were from outside the island.8 The initial guide industry in Yakushima was that of those who settled down in Yakushima and were knowledgeable about the forest. The Yakushima Guide Association was the first Yakushima’s guide organization and was set up in 1989 (Setoguchi et al., 2004: 603).

The popular tourism in Yakushima in those days was mass tourism and visitors went around the major tourist spots by guided bus. Those guides who were acting independently came together to deal with large tourist groups (Nakajima, 2010: 253–254, Setoguchi et al., 2004: 603). Around 1990, Yakushima actively promoted tourism development by utilizing the natural environment (Fujiki, 2004: 99). In October 1990, Kamiyaku Town announced the Utilization Plan of Forest Land, which had the regional image concept of “Super Nature Yakushima”. The plan was aimed the new community development that was centered on the reconsideration of forest resources and regional development with the basic concept of the creation of forest culture based on the close relationship between the forest, water and humans (Yagi, 1997: 21).

The Kagoshima Prefectural government worked out a Master Plan for the Yakushima Environmental Culture Village Scheme in November 1992 and attempted a new regional development that realized the symbiosis of nature and humans through environmental learning.9 The following year, the Yakushima Environmental Culture Foundation, as the main organization for the scheme, was established by Kagoshima Prefecture, Kamiyaku Town and Yaku Town. Then, on 11th December 1993, Yakushima was registered as Japan’s first World Natural Heritage Site.10 From the viewpoint of the four evaluation categories in the registration, the natural beauty of the landscape of the huge Yakusugi natural forest and the island ecology of the marked vertical distribution of vegetation were seen as noticeable universal values.11

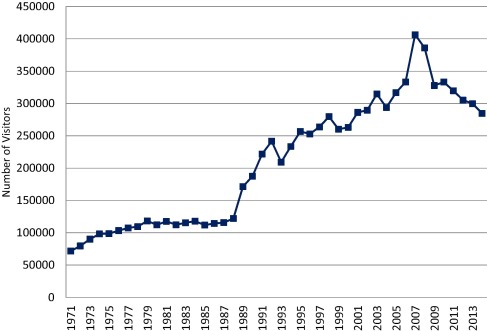

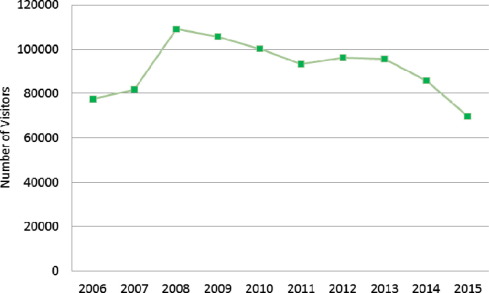

The registration of World Natural Heritage in 1993 had a great impact on Yakushima, such as an increase in the number of tourists and a demand for guides (Figs. 5, 6 and 7), thus, the islanders also became interested in the work of tour guides. Thereafter appeared full-time eco-tour guides. More outsiders came to Yakushima to work as guides. However, various problems arose by an increase of tourists who aimed to see Jomonsugi, the largest and oldest cedar tree in Japan. Concerns were raised by residents about environmental pollution and with the tourist use of holy mountain areas. The issue of the quality of guides also arose (Kanetaka and Karolin, 2011: 71). To solve these issues, the Yakushima Ecotourism Promotion Council established a registration system for Yakushima guides in 2006 and has been trying to improve the quality of guided tours and to make a cooperation among them.

Amami Oshima

In the Amami Islands, which once experienced a tourist “boom” as the southernmost islands until Okinawa’s reversion to Japan in 1972, the major tourism resource until 1980s was the marine area with its subtropical climate. According to the Amami Islands Tourism Guidebook, published by Amami Islands Tourism Bureau in 1988, sea bathing, camping on the beach, diving, fishing and other marine sports were the main leisure attractions. Besides, circular tours that go around important scenic spots and cultural tourism targeting traditional events and historical ruins were indicated as tourist attractions. In Amami Oshima, Mt. Yuwan-dake and the mangrove forest were introduced as scenic spots (Fig. 8), but compared to the sea, mountains and forests were not considered as important in terms of tourism resources.

It was after 1990 that tourism resources that made use of land areas, which are equivalent to ecotourism sites now, came to grab people’s attention. This opportunity was brought to attention by a local cameraman who made a tourism poster with a picture that he took at Kinsakubaru forest (Fig. 9). In those days, mountains and forests were stereotypically regarded as not the target of tourism because those areas were seen as dangerous with poisonous snakes called habu. Thus, the poster was first of its kind as a tourism poster with its image of a forest. After that, such local people who became guides as a regular business appeared. According to our survey, it was around the early 1990s that Kinsakubaru and the mangrove forest were under full-scale use as tourist destinations by a tourist agent called Island Service, which was found to have already been undertaking tours in the form of an “outdoor experience” (Fig. 10).

In this way, it was a private travel agency that used “forests” as a tourism product to market as a tourist commodity, and then mainland travel agencies also sent tourist to Amami Oshima focusing on Amami’s nature. After that, the administrations also came to realize that land area tourism resources were worthwhile to the tourism industry (Kuwahara and Song, 2016).

In May 2003, Amami and Okinawa became the candidate sites of World Natural Heritage together with Shiretoko and Ogasawara in the Internal Meeting on the Candidate Sites of World Natural Heritage under the name of “Amami-Ryukyu”. In that same period, various administrative efforts were made. For example, the Kagoshima prefectural office and the Amami Islands Wide Area Affairs Association made the “Amami Islands Nature Symbiotic Society Plan” in September 2003. The Amami Islands Wide Area Affairs Association also started the “Amami Islands’ Important Ecological Areas Investigation Project” from fiscal 2003. Thus, Amami’s ecotourism started together with the efforts for World Natural Heritage. According to administrative officers, it was since the “Amami Musium” scheme in 2004 that the concept of ecotourism was actively used.

In this way, there existed a kind of ecotourism under the name of outdoor tours and nature experience tourism in the 1990s and they had been practiced in the private sector. Thus, since Amami became a candidate site for World Natural Heritage, the administration came to highlight the word “ecotourism” and has promoted it accordingly. In consequence, Amami’s ecotourism is deeply related to its World Natural Heritage registration, and the administration has carried out the promotion of ecotourism and the institutionalization of eco-tour guides in a required form for the registration of World Natural Heritage.

Discussion

Ecotourism and World Natural Heritage

Firstly, we would like to show how ecotourism started and how it is related to World Natural Heritage, and clarify the characteristics of each island.

In the Ogasawara Islands where whaling was practiced in the past, the first whale watching was started as a way of further development of the use of whales by following the example of Hawaii’s Maui Island where the conversion from whaling to whale watching ecotourism was successfully made. It was the time before the central administration in Tokyo took any action on ecotourism, and Ogasawara’s case could be the one that showed the introduction of ecotourism from the idea of local government and nongovernmental organizations. To establish whale watching, the establishment of associations and rulemaking were achieved early, and followed by the administration. Ogasawara village decided that the promotion of ecotourism was one of the basic policies for the tourism promotion plan and started a fully-fledged effort from the year 2000. The issue of Ogasawara’s World Natural Heritage registration appeared around that time. The opinions over Ogasawara’s World Natural Heritage registration were divided into two, that is, the one for protecting the unique ecosystem and the other for regional promotion. In 2011, Ogasawara was chosen as the fourth site for World Natural Heritage registration in Japan.

In Iriomotejima Island, since the reversion to Japanese administration in 1972, tourism based on sea resources such as diving and other marine sports were popular. Some of the local residents who were worried about the influx of capital from the mainland as a result of the resort law enacted in 1987 had recognized the needs for the promotion of ecotourism. On the one hand, even when viewed from the entire movement centered on the Environment Agency, Iriomotejima Island, where the basic survey for the promotion of ecotourism started in the early stages, was placed as a model area for ecotourism. The argument for ecotourism by such people in different positions such as local young people and the non-local researchers became a direct opportunity for the establishment of the association. In this way, though the action toward organizing ecotourism was quick, the various issues on the use of nature remained unsolved. So, nature in Iriomotejima Island seems to have been protected by external forces such as the construction and development of ecotourism related systems under World Natural Heritage registration.

In Yakushima, 90% of the total land area is forest, which was a holy place for the islanders and important resources for their daily life in the past. The history of the use of Yakusugi goes back to the Edo period, and the peak of deforestation was in 1960s, but in the 1970s, reconsideration of Yakusugi from industrial resources to the object of protection and as a source for regional promotion began. Thus, a change was brought in regarding the use of the forest. The guide business in Yakushima was initiated by non-local forestry workers who were familiar with the forest and guided tour in the forest until the 1980s. However, in the 1990s, the consciousness of ecotourism seems to have started to arise after the registration for World Natural Heritage in 1993. Until then, most of those who were engaged in the guide business were non-local people. However, local residents also came to turn their eyes to the guide business because of the increase of tourists and the demand for guides by World Natural Heritage registration. Yakushima’s ecotourism was thus boosted as a product of World Natural Heritage.

Finally, in Amami Oshima, the tourism of sea areas such as diving and fishing was popular as a result of a past remote island “boom”. Currently, the mangrove forest which has been placed as an object for eco-tours in Amami Oshima was a mere scenic spot until the 1980s, and the nature of land areas was seldom treated as a tourism resource. The time when Amami people became interested in the mountains and forests was in the 1990s, and most of those people were local and young who U-turned from mainland cities. They regularly went to forests for nature observation as their hobby. Some of them were even engaged in the guide business and made several tour courses to provide to those tourists who want to experience the natural environment. People of the local Wild Bird Society often guided the people from mainland to the forest. Some of them even made guiding their principal profession, and thus the current period of ecotourism started. The administration came to notice the value of nature, and thus, Amami’s land area came to be used full-scale as a tourism resources. Especially, after Amami became a candidate site for World Natural Heritage in 2003, ecotourism was actively accepted as the way for environment consciousness, management and conservation. The word and consciousness of ecotourism in Amami Oshima can be said to have been added on to what was originally there.

Eco-tour guide and World Natural Heritage

The existence of guides is important in ecotourism because the guides play a major role for the improvement of quality and minimizing the influence of eco-tours against nature. Here, we discuss how the guides are organized in each island, and whether or not self-imposed rules exist. Also, we examine the characteristics of the organization of guides in each island, and whether or not changes in guide activity can be seen in the efforts for the registration of World Natural Heritage.

In the case of Ogasawara, such organizations as Ogasawara Whale Watching Association (1989), Ogasawara Village Tourism Association (1974) and Ogasawara Ecotourism Council are positioned as the organizations related to guides. The Ogasawara Whale Watching Association has self-imposed rules for whale watching and swimming with dolphins, and has named its twenty-one members on its website. And, six field guides businesses, as well as accommodation and eating establishments were introduced on the website as cooperating with the association.12 On the tour-guide list of the Ogasawara Village Tourism Association, there are sixty-one guide businesses that are related to sea and land area resources, out of which there are twenty-five dolphin swimming and whale watching guide businesses and twenty-six forest guide businesses.13 The guide businesses that had registered for both Whale Watching Association and Tourism Association amounted to twenty.

As an effort for the registration of World Natural Heritage, a new guide system was started. That is, the Ogasawara Ecotourism Association established a registration system for Ogasawara Land Area Guides in 2011.14 To compare with sea area guides, the administration became actively involved with the land area guides who had not been well managed until this time.

The number of the registered guides is twenty-four (twenty businesses) including more than half (fifteen businesses) of the forest and mountain guides of the Ogasawara Village Tourism Association, and the aim of the administration to organize the guides in the wake of the World Natural Heritage registration seems to have been achieved to a certain extent. However, it needs to be verified whether or not the council and guide system are functioning properly, and how much influence they have on tourism.

In Iriomotejima Island, there are such associations as Taketomijima Tourism Association (1981), Iriomotejima Ecotourism Association (1996) and Iriomote Canoe Union (1999). To count from the lists of each association, there are thirty-eight guide businesses in the Taketomi Town Tourism Association, and thirty-five guide businesses in the Iriomote Canoe Union. The number of members who belong to both the Iriomote Canoe Union and the Taketomi Town Tourism Association is only twelve guide businesses.

On the other hand, the case of the members of the Tourism Association who are doing canoe guides without joining the Canoe Union is twelve businesses, out of which six guide businesses are found to be practicing guide businesses and independent from the union.15 As mentioned above in the case of Iriomotejima, the union has a self-imposed rule that limits the number of tourists up to fourteen people a day that a guide can bring on a tour. Also, those guides who use the most popular course of canoe tourism for commercial purpose are required to join the union (Yanagida, 2012: 121).

Thus, the Iriomotejima Ecotourism Association was established as the first ecotourism organization in Japan, but after twenty years, the current situation is that the move toward the institutionalization of guides is still slow. The reason seems to be in the weakened influence of the association by breaking up the canoe businesses that organized the union independently from the tourism association. According to a member of the Association, though six guide business groups and forty-two people are registered as members, the members who are engaged in the guide business are about ten to fifteen people. As a category of business, the land area guides such as those who specialize in trekking and mangrove canoeing is said to make up an overwhelming majority.

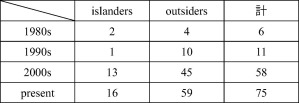

In Yakushima, the Ecotourism Promotion Council (2004) initiated the Yakushima Guide Registration System in 2006, and altogether seventy-five guides are registered,16 out of whom sixteen guides are from Yakushima, and fifty-nine are from outside the island. So, we can see that Yakushima’s guides are mostly outsiders and thus externalized. The I-turn guides are from various places, such as nine from Tokyo, eight from Osaka and five from Kanagawa prefecture. Most of the guides choose land areas such as mountains and forests as their sites for eco-tours.

In Yakushima, one hundred and forty-five guides were registered on the list of the Yakushima Tourism Association in 1999, out of whom only sixty guides have been registered on the list of the Yakushima Guides of Ecotourism Promotion Council.17

In Amami Oshima, forty-nine guides were registered on the list of the Eco-tour Guide Liaison Council in 2008, out of whom twenty-five guides were from Amami Oshima, and thus the characteristic of Amami Oshima’s guides is that they are mostly localized in comparison with the other three islands.18 In the guide section of the membership list of the Amami Oshima Tourism Association of 1992, six guide businesses were registered, out of which four guide businesses were registered to the Guide Liaison Council at the same time.19 The organization of land area guide in Amami Oshima was set up in an effort to promote World Natural Heritage registration, and before that, there was no action taken by the guides toward the establishment of their own association. But, among them, there can be seen cooperation, sharing information, and portioning out the work with each other.

What World Natural Heritage has brought

Non-local people who lived in Yakushima to work in forestry were able to reach deep into the forest, and were aware of the value from early on (more so than local people). People familiar with the mountains such as mountain climbers also came to Yakushima in the early years, while local residents were not aware of the value of nature. However, this situation underwent a complete change by the significant event of World Natural Heritage registration. Looking back at the process toward the registration of World Natural Heritage, it can be seen that local residents were not a large part of it, since there was no precedent case before.

After registration, the nature of Yakushima became known not only to domestic Japan, but also to overseas, and a lot of people came to visit Yakushima. Thus, Yakushima people began to feel the value of their island, and their attachment to the island increased. On the other hand, because of a rapid increase of tourists, unpleasant events between local residents and tourists often happened, and also the complaints against the non-local guides who brought the tourists deep inside the island arose from the local residents. This kind of experience seems to have further deepened the recognition of the value of the island.

In the case of the Ogasawara Islands, whale watching was started as the first example of eco-tourism about twenty years before the registration of World Natural Heritage, and the islands had been placed as an advanced area of ecotourism. Not simply did ecotourism start early, but in their efforts toward it, ecotourism had been practiced intimately with the local residents. In Ogasawara, whaling had been seen through the ages, and the people have been intimately associated with the sea and whales.

Ogasawara people established a Whale Watching Association at once and worked together with researchers not only for the promotion of tourism, but also as a research organization. Furthermore, since there were many research projects on various kinds of nature, many researchers’ visits, many symposia and monitoring tours, local residents seem to have had more opportunities to experience ecotourism on the island.

In the Ogasawara Islands, a sudden increase of tourists could not be seen because the only access to the islands is by boat, which takes about twenty-five hours from Tokyo, and the travel cost is quite high. Since there was less friction between local residents and the tourists, than in some other locations, Ogasawara’s World Natural Heritage registration didn’t change the people’s consciousness about the islands, rather, they are getting used to it through the efforts related to ecotourism, which has increased year after year.

In Iriomotejima Island, research on the promotion of ecotourism was undertaken at an early stage and it was similar to that of the Ogasawara Islands. However, there were many I-turn people because of diving “booms”, and there some of characteristics different to those of Yakushima and the Ogasawara Islands can be seen. Especially, since their work after they immigrated to the islands was mainly in the tourism business, they even established the canoe union themselves, and they had less of a relationship with local people and less opportunities for mutual understanding in the use of nature.

Though the local young people contributed to the establishment of the Ecotourism Association, the impact was insignificant. In such a situation, the institutionalization of eco-tour guides didn’t proceed and environmental issues arose, such as the considerable destruction of nature by ecotourism that has been pointed out by some researchers. Miyauchi (2003) shows the evaluation of ecotourism by local residents from his questionnaire survey. Those who thought that ecotourism contributed to the tourism of the islands were most common. However, to the questions whether or not the local people worked proactively on ecotourism, or they contributed to the development and revitalization of the island, much greater answers were “not for sure” (Miyauchi, 2003: 114).

Under these conditions, the idea of World Natural Heritage registration emerged, and Iriomotejima people came to face with issues of ecotourism again. In their efforts for the registration of World Natural Heritage, the opportunities to renew the understanding of the value of their island would increase for those who are not engaged in tourism business.

In Amami Oshima, various efforts toward the registration of World Natural Heritage have been made by the Ministry of Environment and the Amami Islands Wide Area Affairs Association from 2003. Recently, researchers are focusing on biodiversity and conducting more studies. Furthermore, they are making efforts to give back the research results to the local residents by having various opportunities to report in cooperation with the administration. The impact of these outreach and enlightenment activities are gradually spreading among the islanders, and thus greatly changing the recognition of Amami people. The land area guides of 1990s were born and raised on the island, and it was always after they had an experience of leaving the island to go to college or get a job that they realized the value of their island and returned home.

In the 1980s when the development called “Amashin” was flourishing, though they had been appealing the importance of nature, they couldn’t get the sympathy of the people. However, the importance of the island first noticed by them seem to have been gradually shared by local people because of effort toward the registration of World Natural Heritage. Thus, the fact that the Amami Islands has become a candidate for World Natural Heritage registration seems to be a very big event from Amami’s historical viewpoint in the sense that it gave an opportunity for the people to renew their understanding of the value of their islands.

Conclusion

To sum up, in the Ogasawara Islands, private sector and administration have made a well-balanced effort for the promotion of ecotourism in comparison with the other three islands where ecotourism has been promoted or World Natural Heritage was registered. And also, because of the restrictions on access which takes twenty-five hours by boat from Tokyo, tourists could be confined to highly motivated tourists, and thus the impact on nature brought by World Natural Heritage registration seems to be relatively low.

In Iriomotejima Island, ecotourism was practiced in an early stage, but the management of environment preservation and the institutionalization of ecotourism were not enough, and thus, it can be highly estimated that the current problems could be solved by registration of World Natural Heritage.

Yakushima seems to be the place where the ripple effect of World Natural Heritage registration is the largest of the four islands. In Yakushima, it can be said that ecotourism has been boosted and promoted as a product of World Natural Heritage registration.

Finally, Amami Oshima is the case where the concept of ecotourism was introduced after the possible story of World Natural Heritage. Amami Oshima seems to be relatively in a dominant position in its effort toward the registration, because the island is in a position capable of learning a lot from the cases of Yakushima and the Ogasawara Islands.

Thus, we can point out two things. Firstly, both Yakushima and Ogasawara are World Natural Heritage sites and the most advanced in ecotourism of the four islands, while both Iriomotejima and Amami Oshima are candidate sites of World Natural Heritage registration, although there is still room for improvement in ecotourism.

Secondly, Yakushima and Amami Oshima are places where World Natural Heritage registration has a strong impact in the sense that it has greatly changed the people’s understanding of their islands, while in Ogasawara and Iriomotejima Islands, its impact seems to be relatively small.

Endnotes

- Zaidan Hojin Kokuritsu Koen Kyokai & Zaidan Hojin Shizen Kankyo Kenkyu Senta, 1993: 3.

- Zaidan Hojin Nihon Kotsu Kosha, 2005: 27–30.

- Ogasawara Whale Watching Association: http://www.owa1989.com/owa/aboutus.

- Later, the name changed to “Amami-Ryukyu”.

- See the website: http://www.env.go.jp/nature/isan/kento/.

- Zaidan Hojin Kokuritsu Koen Kyokai & Zaidan Hojin Shizen Kankyo Kenkyu Senta, 1993: 3.

- Kyushu Forest Management Bureau: http://www.rinya.maff.go.jp/kyusyu/yakusima/sub3.html.

- Kumamoto Regional Forestry Office controlled the all Kyushu area and many people came from Kumamoto and Miyazaki as a worker. When there was a labor shortage, islanders were rarely hired, but most of the workers were outsiders.

- Yakushima Environmental Culture Foundation-Yakushima Environmental Culture Plan:http://www.yakushima.or.jp/static/concept.php

- Yakushima World Natural Heritage Center: https://www.env.go.jp/park/yakushima/ywhcc/wh/toroku.htm.

- Japanese World Natural Heritage–Yakushima: http://www.env.go.jp/nature/isan/worldheritage/yakushima/uiversal/index.html.

- Ogasawara Whale Watching Association: http://www.owa1989.com/member/ship.

- Ogasawara Village Tourism Association Tour guide list:: http://www.ogasawaramura.com/play/.

- Ogasawara Village Office registered guide list: http://www.vill.ogasawara.tokyo.jp/registration_guide/.

- Taketomi Town Tourism Association member list: http://www.painusima.com/memberlist, Iriomote Canoe Union member list: http://www.iriomote-canoe.com/members/index.html.

- Yakshima Ecotourism promotion Council-Yakushima Guide Directory: http://www.yakushima-eco.com/yakushima_fl/guide_meikan/00_all.html.

- Yakushima Tourism Association-Guide List:: http://yakukan.jp/play/guide.html.

- Amami Islands Tourism & Local Product Association – Guide Directory: http://www.goontoamami.jp/world/guide/amami.

- Amami Oshima Tourism Association-Member List: http://amami-kankou.com/member/.

References

- Akiyama, 2008 Tomoyuki Akiyama A study on the ecotourism model for facilitating the independence of islanders in Ogasawara. Rikkyo Bijinesu Dezain Kenkyu, 5 (2008), pp. 245-258

- Amami Islands Tourism & Local Product Association – Guide Directory Amami Islands Tourism & Local Product Association – Guide Directory: http://www.goontoamami.jp/world/guide/amami.

- Amami Oshima Tourism Association-Member List Amami Oshima Tourism Association-Member List: http://amami-kankou.com/member.

- Fujiki, 2004 Miho Fujiki Anthropology of ecotourism: a case of Yakushima Island. Minzoku-Shakai Kenkyu, 3 (2004), pp. 85-128. (in Japanese)

- Hagino, 2015 Makoto Hagino The impact of tourism recession on Yakushima and donation: a fate of island tourism. Amami News Lett., 39 (2015), pp. 14-19. (in Japanese)

- Haraguchi, 1996 Izumi Haraguchi Monopoly system of Yakusugi under the administration of Satsuma Domain: a socio-historical study on the development of Yakusugi. Kagoshima University Nansei-chiiki Kenkyu Shiryo Senta Hokoku Tokubetu-go, 6 (1996), pp. 40-44. (in Japanese)

- Ichinoki and Shumiya, 2007 Shigeo Ichinoki, Takeharu Shumiya A study on the situation of the utilization of tourism and the effects of the rules of touristic utilization in Minamijima Island of the Ogasawara Islands. Ogasawara Kenkyu Nenpo, 30 (2007), pp. 75-87. (in Japanese)

- Iriomote Canoe Union member list Iriomote Canoe Union member list: http://www.iriomote-canoe.com/members/index.html.

- Ishigaki, 2000 Kinsei Ishigaki Thinking island revitalization from Iriomotejima Island. Chiiki Kaihatsu, 425 (2000), pp. 52-60. (in Japanese)

- Ishihara et al., 2010 Shun Ishihara, Wataru Kosaka, Kayo Morimoto Trial and error of regional society over the ecotourism of Ogasawara Islands: a matter of “Nanto rule”. Ogasawara Kenkyu Nenpo, 33 (2010), pp. 7-25. (in Japanese)

- Japanese World Natural Heritage–Yakushima Japanese World Natural Heritage–Yakushima: http://www.env.go.jp/nature/isan/worldheritage/yakushima/uiversal/index.html.

- Kaizu, 2008 Yurie Kaizu A discussion on the agendas of Island ecotourism. Chikyu Kankyo, 13 (1) (2008), pp. 89-100. (in Japanese)

- Kanetaka and Karolin, 2011 Fumika Kanetaka, Frank Karolin The development of tourism industry in Yakushima and its spatial characteristics. Kankyo Kagaku Kenkyu, 6 (2011), pp. 65-82. (in Japanese)

- Kichira et al., 1998 Kesayoshi Kichira, Kunihiro Hirata, Hironori Baba Utilizing of forest in the Island of Yakushima (1) historical fluctuations in the management and utilization of Yakusugi (Cryptomeria japonica). Kagoshima Daigaku Nogakubu Gakujutsu Hokoku, 48 (1998), pp. 31-39. (in Japanese)

- Kuwahara and Song, 2016 Sueo Kuwahara, Dajeong Song Tourism in the Amami Islands. Key. Kawai, Ryuta Terada, Sueo Kuwahara (Eds.), The Amami Islands: Culture, Society, Industry and Nature, Kagoshima University Research Center for the Pacific Islands (2016), pp. 50-62

- Matsutaka, 1998 Akihiro Matsutaka A discussion on ecotourism: from the cases of Iriomotejima, Zamami-mura, Yakushima. Okinawa Daigaku Chiiki Kenkyusho Nenpo, 10 (1998), pp. 11-32. (in Japanese)

- Ministry of the Environment Ministry of the Environment “Japan’s World Natural Heritage” http://www.env.go.jp/nature/isan/worldheritage/index.html.

- Miyauchi, 2003 Hisamitsu Miyauchi A basic study on ecotourism in Okinawa prefecture. Human Sci., 11 (2003), pp. 83-121. (in Japanese)

- Morita, 1999 Yuichi Morita Those who think about ecotourism: initiative and future outlook in Ogasawara. Shima, 45 (2) (1999), pp. 41-49. (in Japanese)

- Nakai, 2002 Tatsuro Nakai Ecotourism for the earth: initiative and agenda in Ogasawara. Chiri Kagaku, 57 (3) (2002), pp. 187-193. (in Japanese)

- Nakashima, 1998 Naruhisa Nakashima Environment Folklore of Yakushima: Development of Forest and the Struggle of Gods. Akashi Shoten, Tokyo (1998). (in Japanese)

- Nakajima, 2010 Naruhisa Nakajima Environmental Folklore of Yakushima Island: Development of forest and disputes of gods. Akashi Shoten, Tokyo (2010). (in Japanese)

- Ogasawara Village Office registered guide list Ogasawara Village Office registered guide list: http://www.vill.ogasawara.tokyo.jp/registration_guide/.

- Ogasawara Village Tourism Association Tour guide list Ogasawara Village Tourism Association Tour guide list:: http://www.ogasawaramura.com/play.

- Ogasawara Whale Watching Association Ogasawara Whale Watching Association: http://www.owa1989.com/owa/aboutus.

- Okuda, 2007 Natsuki. Okuda Current situation and issues of ecotourism in Japan: field research in Iriomotejima. Chiiki Kenkyu, 3 (2007), pp. 83-116. (in Japanese)

- Sato, 2008 Yoshinobu Sato The influence of the sightseeing development in case of island development. Nagasaki Wesleyan University Chiiki Sogo Kenkyusho Kenkyu Kiyo, 6 (1) (2008), pp. 25-32

- Setoguchi et al., 2004 Masaaki Setoguchi, Akio Shimomura, Hiromu Ito, Ryohei Ono, Yoichi Kumagai A study on the development of “ecotour-guide” in Yakushima Island. Jpn. Inst. Landscape Archit., 67 (5) (2004), pp. 601-604

- Suzuki, 2010 Koshiro Suzuki World Heritage as a politics. Kanko Kagaku Kenkyu, 3 (2010), pp. 57-69. (in Japanese)

- Taketomi Town Tourism Association member list Taketomi Town Tourism Association member list: http://www.painusima.com/memberlist.

- Yakushima Ecotourism Promotion Council-Yakushima Guide Directory Yakushima Ecotourism Promotion Council-Yakushima Guide Directory: http://www.yakushima-eco.com/yakushima_fl/guide_meikan/00_all.html.

- Yakushima Environmental Culture Foundation-Yakushima Environmental Culture Plan Yakushima Environmental Culture Foundation-Yakushima Environmental Culture Plan: http://www.yakushima.or.jp/static/concept.php.

- Yakshima Ecotourism promotion Council-Yakushima Guide Directory Yakshima Ecotourism promotion Council-Yakushima Guide Directory: http://www.yakushima-eco.com/yakushima_fl/guide_meikan/00_all.html.

- Yakushima Tourism Association-Guide List Yakushima Tourism Association-Guide List:: http://yakukan.jp/play/guide.html.

- Yakushima World Natural Heritage Center Yakushima World Natural Heritage Center: https://www.env.go.jp/park/yakushima/ywhcc/wh/toroku.htm.

- Yanagida, 2012 Risa Yanagida A study on the establishment o Iriomotejima canoe tourism business and its development. Mejiro University General Science Studies, 8 (2012), pp. 113-125. (in Japanese)

- Yagi, 1997 Tadashi Yagi The development and environment of World Heritage Yakushima. Minami Nihon Bunka, 30 (1997), pp. 11-50. (in Japanese)

- Zaidan Hojin Kokuritsu Koen Kyokai, 1993 Zaidan Hojin Kokuritsu Koen Kyokai, Zaidan Hojin Shizen Kankyo Kenkyu Senta 1993 2002 A research report on the promotion of the way for nature experience activities, Tokyo: Zaidan Hojin Kokuritsu Koen Kyokai & Zaidan Hojin Shizen Kankyo Kenkyu Senta (in Japanese).

- Zaidan Hojin Nihon Kotsu Kosha, 2005 Zaidan Hojin Nihon Kotsu Kosha 2005 2004 Ecotourism promotion model project of Ogasawara area, Tokyo: Zaidan Hojin Nihon Kotsu Kosha.