At the edge: Heritage and tourism development in Vietnam’s Con Dao archipelago

Southern Cross University, Military Road, Lismore, Australia prhshima@gmail.com

Southern Cross University, Military Road, Lismore, Australia trangianus@yahoo.com

Abstract

This article outlines the development of Vietnam’s Con Dao archipelago (and Con Son island in particular) as tourism destinations since the formal reunification of Vietnam in 1975. In particular it examines the nature of the area’s two main tourism attractions, Con Son’s prison sites and memorials and the archipelago’s natural environment, and how these have been marketed to and experienced by national and international tourists. This discussion also involves considerations of the concept of thanatourism and how the latter might be understood to operate in a Vietnamese context. The final sections of the article consider development plans and options for the archipelago; how these can be understood within national political contexts; and what problems there might be with their implementation.

Keywords

Con Dao, Con Son, Vietnam, Thanatourism

Introduction

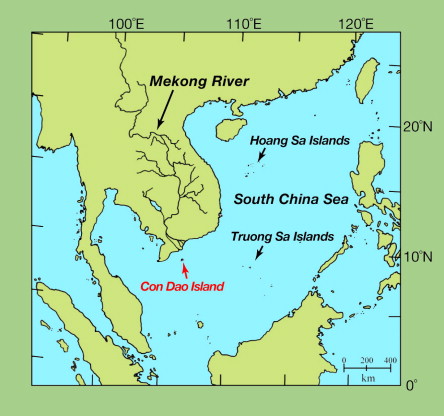

The Con Dao archipelago is situated off the south eastern tip of Vietnam, 230 kilometres south of Ho Chi Minh city, between 106°54 East and 8°34 and 8°49 North (Fig. 1). The archipelago has a total landmass of 75 square kilometres, distributed across 16 islands. The largest and only inhabited island is Con Son (51.5 square kilometres), which has a population of 6800. The majority of the island’s population resides on the south east coast, with smaller settlements on the south coast. The archipelago has a long history of habitation, with recent archaeological finds indicating that humans have visited and/or lived on the islands for over 4000 years (Nguyen et al., 2010). The archipelago’s location on a crucial marine route between East Asia and (present-day) Malaysia and Indonesia has resulted in frequent contact with mariners from various nations. A number of early European travellers to eastern Asia visited the area, with Marco Polo sheltering out a storm in the islands in 1294 (noting in his memoirs that the archipelago was a beautiful and bounteous place). Later, in the 15th and 16th centuries, other European ships visited to obtain fresh water, fruit and meat from the local community. As European powers intensified their interest in East Asia in the 17th and early 18th centuries, they began to seek more a permanent presence in the region. An early manifestation of the latter impulse occurred when the British East India Company established a base on Con Son in 1702. The base operated until 1705, when it was severely damaged during an uprising by Malay soldiers in the Company’s employ and local villagers. Following this incident, the Vietnamese government re-asserted their control over the islands. While historical documentation on the population of the archipelago in the 18th and 19th centuries is scant, an imperial ordinance issued by the Vietnamese King in 1821 noted that two hundred individuals lived on Con Son at this time (including a number of criminals deported from the mainland) and announced incentives for mainlanders to migrate there in order to sustain the settlement (Minh Mang, 1821).

Despite the archipelago’s isolated location at the south eastern extremity of the nation, it played a significant role in the introduction of French influence into Vietnam in the 18th Century and, thereby, to the political upheaval that consumed the region in the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1770 a period of intense conflict commenced between factions in support of the traditional ruling family of Vietnam, the Nguyen Lords, and their rivals, the Tay Son brothers. In 1783 the Nguyen leader Anh negotiated with a French missionary, Pigneau de Behaine, to secure French military assistance to help Anh to regain control over the nation. As part of treaty negotiations signed at Versailles in 1787, Anh promised to cede Con Son to the French and to give them a trading concession in (present-day) Da Nang in return for their support. While the upheavals of the French Revolution disrupted the intended state support for Anh’s cause, de Behaine persuaded a number of French merchants to fund the provision of supplies and mercenaries that began to arrive in 1789. This support aided Anh’s attempts to regain control in a series of campaigns that were successfully completed in 1802. Aside from Con Son’s assignment to France in recognition of its support for the Nguyen cause, some historical accounts identify that the archipelago played another role during the period in that Anh and his retinue took refuge on Hon Ba island (off the south coast of Con Son) in the mid 1770s. There is also a further embellishment to this account that plays a prominent role in local folklore. Legend has it that Anh undertook to send one of his sons to Versailles as a guarantee of good faith in negotiations with France. When his wife, Phi Yen, refused to acquiesce to this he abandoned her. Remaining in the archipelago, she remained true to her husband and, when courted by another man, committed suicide by throwing herself into the sea. In marked contrast to her husband’s reckless engagement with a foreign power, Yen’s steadfast devotion to both son and husband is commemorated in a temple on Con Son island and the story is commemorated in an annual festival, held in October.

The French went on to use their presence and influence in Vietnam to begin a colonial enterprise that intensified in the 1850s, as they took control of the southern third of Vietnam, before going on to colonise the whole country in the following twenty years. French settlement of Con Son occurred in 1861, partly in response to fears that the British would establish a presence there (as the islands were close to the British sphere of influence in [present-day] Malaysia) (Nguyen et al., 2010). Following the arrival of a French warship in the archipelago in late 1861, personnel were dispatched to survey and to subsequently construct basic buildings on Con Son’s south east coast. The arrival of French forces precipitated an uprising by locals and defecting Vietnamese soldiers employed by the French that was eventually defeated, with many locals killed in the conflict. As a result of this, and related food shortages, many Vietnamese left the island soon after, with the population dropping to just over 300 (Nguyen et al., 2010). As conflict and political repression on the mainland intensified, the French used the island to house Vietnamese nationalist prisoners and built facilities that became operational in 1862. These were maintained by the French until their withdrawal from Vietnam in 1954, when the facilities were taken over by the South Vietnamese government and, subsequently, the US military. The prisons operated until 1975, closing shortly before the end of national conflict.

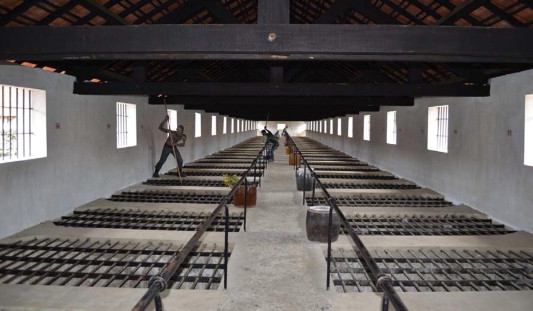

From 1862 through to 1975, a number of prisons operated on Con Son, uniformly under harsh regimes in which torture was commonplace and prisoner deaths were frequent – the current estimate being that around 20,000 prisoners died in captivity on the island over a 113 year period (Nguyen et al., 2012). Following initial ad hoc prison facilities, major complexes were constructed, including the Phu Hai (Bagne I) prison, which opened in 1892, together with an underground mill, in which prisoners worked. The notorious Phu Son (Bagne II) prison opened in 1916 and subsequently housed a succession of prominent Vietnamese communist leaders in a complex that also included an execution room equipped with a guillotine. One of Phu Son’s most prominent features was its so-called ‘tiger-cages’ – tiny cement-walled cells with barred ceilings above which guards patrolled, enabling them to constantly monitor, harass and abuse prisoners (Fig. 2). Torture was routinely administered in Phu Son and in subsequent camps (Management Board Con Dao Relics, 2011; Zinoman, 2001). These practices continued into the US period (see Luce, 2010) and were only significantly modified following US senator Augustus Hawkins’ and staff aide Tom Harkin’s visit to the island in 1969 and a subsequent exposé of the ‘tiger cages’ published in the US magazine Life in July 1970 (Graves, 1970: 2A and Harkin, 1970: 26–30). In the early periods of French colonial operation the prison facilities appear to have housed around 1000 prisoners at any one time. Following the construction of the Phu Hai and Phu Son prison complexes, numbers increased substantially, with precise figures of 3126 in 1939 and 4403 in 1943 being recorded in official records (Nguyen et al., 2012). The intensification of conflict during the 1960s and US support for the Saigon regime resulted in further expansion of facilities and an increase in prisoner numbers to c8,000 in 1967–69 and c10,000 in 1970–73 (Nguyen et al., 2012).

After reunification

Con Son island prison facilities ceased operating in 1975 and in the initial post-War period the majority of Con Son’s residential population (of around 4000) were villagers from traditional island communities or personnel associated with military and government agencies (together with a small group of ex-prisoners who elected to remain in the archipelago). Following a decline in the 1980s, the local population increased after the archipelago’s incorporation into Ba Ria – Vung Tau province in 1991, reaching around 4250 at the end of the decade. With the development of tourism in the 21st Century (discussed further below) Vietnamese citizens from various areas of the country moved to the island to pursue work opportunities with the result that the population currently numbers around 6800.

While Con Son has sustained a continuing population for several centuries, migration to and from the archipelago at various periods has resulted in a situation in which there is a high degree of cultural and linguistic similarity between members of established Con Son island communities and those of the Vietnamese mainland, particularly the far south. While there are a number of distinct folkloric elements to Con Son culture (including the aforementioned Phi Yen festival); there does not (currently) appear to be any pronounced perception of there being a distinct island culture in the archipelago (as opposed to a localised version of a more general Vietnamese one). While this situation merits more sustained analysis as to aspects of individual intangible heritage that may not have been identified and articulated outside of the groups concerned; indigenous socio-cultural distinction has not been asserted in the islands and this element is a relatively indistinct aspect of Con Son’s contemporary society and one that has not been promoted or facilitated by governmental agencies or commercial tourism operators.

In March 1984 wooded areas of Con Son and the outlying islands were declared as preserved national forest areas. This initiative was developed further in 1993 when Con Dao National Park (CDNP) was established, comprising a land area of approximately 60 square kilometres, including substantial areas of Con Son and the total landmass of the uninhabited islands, together with a coastal marine zone of around 140 square kilometres (CDNP, nd: online). CDNP provides protection to areas of tropical forest (both evergreen and deciduous) that are home to a number of species of flora and fauna unique to the archipelago. The park’s coastal zone is also home to abundant variety of marine animals, including turtles and dugongs, and a wide variety of clams are plentiful in coastal waters. While a project to propose Con Dao as UNESCO world cultural and natural heritage site was mooted in 2006 (Unattributed, 2006: online), a formal proposal did not eventuate.1 One aspect of the archipelago’s biodiversity was however recognised in 2014 through the listing of its wetlands as a Ramsar site of international ecological importance2 and the archipelago’s unspoilt natural attractions continue to play a prominent role in tourism promotion.

Since the closure of the prisons, the establishment of the CDNP and the archipelago’s realignment to tourism; Con Son’s socio-economic character has been in flux and subject to definition and redefinition in the light of the economic opportunities open to its community and to external parties investing in its development. The following section identifies those aspects that are most prominent within contemporary tourism and the manner in which their development is variously complementary and antagonistic.

Tourism – an historic overview

During the French prison period a guesthouse operated to accommodate visiting official parties and occasional independent travellers who were permitted to vacation in the archipelago (such the composer Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns, who stayed for a month in 1895 during a visit to Vietnam). A similar establishment also catered for South Vietnamese and US visitors in 1954–75. Formal tourism to Con Son and the Con Dao archipelago began, on a small-scale, in the early 1980s, with the first hotel, the Phi Yen, being established in 1980 in the former French guesthouse building.

The local industry began to develop significantly in the late 1990s with visitors arriving by boat or helicopter from southern Vietnam, and Con Son’s first modern hotel, the Sai Gon -Con Dao hotel, opened in 2000. At this time 98% of tourists were national, with numbers of international visitors not increasing significantly until 2004, following the commencement of regular passenger flights from Ho Chi Minh City. These flights, in turn, spurred developments catering for both international visitors and more affluent Vietnamese. Indeed, the majority of the island’s current hotels have been established in the last five years, including the ATC in 2009 and the Six Senses in 2010. The latter, in particular, marked a particular new orientation for the archipelago’s tourism industry by virtue of being a five star resort operated by the prestigious Six Senses company. The company’s brand image is based on its claims that its hotels are designed and constructed to have a sustainable and environmentally sensitive relation with their locations.3 Positioned on a secluded bay, well away from the island’s prison camp sites, the Con Son Six Senses rapidly attracted the patronage of leading international celebrities such as US actors Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, an aspect that featured prominently in subsequent publicity for the resort.4 International publicity for the island also resulted from the French Koh-Lanta TV series (a Survivor-style program) shooting its 10th season in the archipelago in 2010; and from highly favourable coverage of the archipelago in high-profile publications such as the New York Times5 and The Lonely Planet.6 As a result of these and related infrastructural and amenity developments, international tourism has increased significantly and currently comprises 18.5% of the 90,000 annual visitation (Table 1). However, as discussed in the subsequent section, the histories and rationales for domestic and international visitation to Con Dao are significantly different.

| Year | International visitors | Domestic visitors | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 233 | 10,428 | 10,661 |

| 2002 | 195 | 10,662 | 10,887 |

| 2003 | 141 | 9840 | 9981 |

| 2004 | 450 | 11,350 | 11,800 |

| 2005 | 1102 | 12,698 | 13,800 |

| 2006 | 1202 | 14,573 | 15,775 |

| 2007 | 1756 | 15,811 | 17,567 |

| 2008 | 2576 | 17,607 | 20,183 |

| 2009 | 1980 | 26,245 | 28,225 |

| 2010 | 3793 | 36,530 | 40,323 |

| 2011 | 13,273 | 53,312 | 66,585 |

| 2012 | 13,050 | 68,982 | 82,032 |

| 2013 | 16,669 | 73,331 | 90,000 |

Commemorational tourism

The world we live in is encased in memory projects, undertakings designed to reconstruct versions of the past suitable for a myriad of purposes in the present.(Bodnar, 2001: ix)

John Bodnar’s reflection on “memory projects” appears in his forward to Hue-Tam Ho Tai’s pioneering anthology The Country of Memory: Remaking the Past in Late Socialist Vietnam (2001). Tai’s volume addresses the complexity of post-conflict engagements with the War years and, in particular, diverse social engagements with official memorial sites. Tai outlined the key issues her edited anthology engages with an introduction that states that:

Public memory in present-day Vietnam is characterised as much by confusion as by profusion… In Vietnam, deciding how to remember a century’s worth of historical change is a matter of grave difficulty for a society filled with uncertainty about its future and only just beginning to rethink its past. (ibid:2)

While Tai’s statement is pertinent as both a characterisation of many of the case studies included in her anthology and as a more general assessment of tendencies in late 20th Century Vietnamese culture, it can be argued that some aspects of history and memorialisation are more problematic than others. In the case of the memory and memorialisation of the prisons of Con Son, it is possible to argue that the historical ‘referent’ that is subject to representation is one of the less ambiguous and less complex ones of the post-War period. As the following discussions detail, visits to prison-era sites and memorials have been the cornerstone of tourism in the archipelago since 1975 and are fundamental to the area’s contemporary brand identity.

Domestic tourism to Con Dao appears to have developed in from the late 1970s, initially in the form of self-organised visits to sites of imprisonment and/or demise of relatives, friends and inspirational figures in Vietnam’s extended struggle for national self-determination. The physical remnants of the prisons and their associated grave sites were a key attraction for tourists and the displays subsequently installed within them provided a chilling and vivid representation of the barbaric conditions in which generations of dissidents were held and in which many perished. Visitation to such sites is a common international phenomenon (in both contemporary and historical contexts) that has attracted a number of different descriptors including ‘dark tourism’ (Foley and Lennon, 1996) and ‘thanatourism’ (Seaton, 1996). The phenomenon the authors refer to involves tourists visiting the sites of various types of disaster and atrocity in order to confront and consume aspects of the experiences that can be gleaned from the locations, memorials and/or interpretative facilities that exist at such sites. With regard to human generated historical events, popular sites for such tourism include battlefields, prisons, concentration camps, and sites of notable murders or assassinations etc. One of the most influential studies of the phenomenon was offered by Seaton (1996), who posed the practice as a subset of the broader phenomenon of thanatopsis – a term referring to various types of meditation on death. In an article entitled, ‘From Thanatopsis to Thanatourism: Guided by the Dark’, Seaton characterised the impulse behind thanatourism as “wholly, or partially, motivated by the desire for actual or symbolic encounters with death” (1996: 240). As Stone and Sharpley discuss in their review and critique of characterisations and theorisations of dark-/thana- tourism, there are problems in trying to affix a singular label to the “enormous diversity of dark sites, attractions and experiences” (2008: 278) such as those identified by Seaton (1996). Miles (2002) attempted to address this by trying to distinguish between sites of actual tragic events and sites commemorating these. In his characterisation, the former are ‘darker’ than the latter. As Stone and Sharpley emphasise, a pertinent aspect of Miles’s discussion is his suggestion that:

‘darkest’ tourism emerges where the spatial advantage of a site of death is amplified by either the recentness of events (i.e. within recent living memory of visitors) or where past events are transported in live memory through technology. Importantly, underpinning Miles’ argument is the assumption that a dark tourism experience requires empathy/emotion on the part of the visitor – such empathy is heightened by the spatial–temporal character of the site. (Stone and Sharpley, 2008: 579)

While the focus of Stone and Sharpley’s discussion is (mostly implicitly) a First World one, where “contemporary society”7 is largely understood to be one reflecting western cultural paradigms (and particularly those relating to death and to aspects of “ontological security” [2008: 581]); the authors’ conclusion recognises that:

dark tourism production is multi-faceted, multi-tiered and exists in a variety of social, cultural, geographical, and political contexts… Thus, the demand for such products will no doubt be equally as diverse and fragmented, pointing to the need for further targeted empirical and theoretical analysis. In addition, dark tourists’ motivations will certainly vary according to intensities of meanings for various individuals within social networks. Indeed, an awareness of mortality and the anticipation of death will differ amongst various social and cultural groups. (ibid: 589)

In the case of Vietnamese visits to war heritage sites (such as those that exist in large numbers in central Vietnam, the location for many combat engagements during the 1960s and 1970s) there are various facets to the rationale for and visitors’ experience of the locations. As Bodnar characterises, drawing on various contributions to Tai’s aforementioned anthology, successful memorialisation of War dead in Vietnam has to combine “predictable tropes of patriotism and heroism” with the acknowledgement that there is a deep social attachment to “rituals that signified that the dead would be reborn in an ‘otherworld’ where they would join a community of ancestors” (2001: x); with the latter aspect providing as powerful a point of connection to the past and inspiration for the future as the former. In this manner, the organic linkage of the two can be seen to allow secular and religious memorialisation to reinforce each other, whereas the exclusion of the former from official memorialisation can be problematic. In this regard it is notable that Con Son’s only Buddhist pagoda, Van Son (also known as Nui Mot), combines the two aspects in its daily chants – amplified on loudspeakers for visiting tourists. One section of a chant that the authors recorded in February 2013, sung by superior monk Nguyet Duc, stated explicitly (in translation):

From the offshore island, we celebrate a requiem mass for the fallen heroes and fellow patriots heroically sacrificed in Con Dao prison. We believe that the fallen will watch over and provide guidance toward peace and happiness of present people and future generations.

Domestic tourism to the Con Dao archipelago currently takes various forms, including both individually organised personal/family tourism and visits organised by institutions, including employers that offer their employees a combined national heritage pilgrimage and associated leisure opportunities in convenient proximity. While diverse tourism streams are now operating in Con Dao (such as those catering for the foreign visitation described below) memorial tourism is still the most significant aspect of local tourism and is widely publicised as such in Vietnam. As the Vietnamese operated visitcondao.com website also characterises, many visitors are “Vietnamese war veterans who arrive in groups and receive a warm reception by the local authorities for their past achievements.” (visitcondao.com, nd: online). A recent high-profile example of this type of visitation occurred in July 2013 when 600 former inmates visited the island for a memorial ceremony attended by former Vietnamese vice president Truong My Hoa. The ceremony included a symbolic recognition of the need for the experience of Con Son prisoners to be remembered and commemorated by future generations. As part of the ceremony 21 torches were lit to symbolise the 21 year long campaign of resistance against US forces. These torches were then passed to members of the Vietnam Youth League in attendance, with the president of the League swearing to acknowledge and commemorate the sacrifice of Con Son detainees in the future (see Unattributed, 2013: online).

The prison history commemorated in events such as the 2013 veterans’ ceremony is manifest in a number of material heritage sites that comprise (various combinations) of the following:

- Prison and/or administration buildings (in various states of preservation).

- Displays within prison buildings that attempt to visually represent aspects of prisoner experience.8

- Burial sites.

- Cemeteries.

- Shrines.

- Memorial parks and statues.

- Museum.

The current presentation of these sites reflects two phases of local memorialisation. The first comprised a simple opening-up of the formerly closed prison facilities to public visitation immediately after the cessation of hostilities in 1975, revealing the hidden horrors of incarceration under successive French, South Vietnamese and US administrations. As visitors increased and awareness of the prisons’ significance solidified, a second phase commenced. This involved the maintenance and organisation of prison sites for visitors and the provision of signage and documentation to enhance visitor experience. One significant development of the prison spaces involved the design and installation of sculptures of shackled and emaciated prisoners in old prison buildings. These figures were commissioned from CEFINAR (Vietnam’s Central Fine Arts Company), based on period photos and witness accounts, and were installed in 1995 (and subsequently renovated and added to in 2000). Crowded together, the figures give a starkly effective representation of prisoner experience that is rendered all the more striking by the low-light conditions of the room they are exhibited in, which gives the pale shapes a ghostly style of apparition (Fig. 3). Located within the actual spaces of incarceration these provide, with reference to Miles’s previously discussed framework, one of the ‘darkest’ imaginable thanatouristic experiences.

The distinction between burial sites and cemeteries made in the previously outlined schema results from the difference between the mass burial sites created under the French administration (which, as might be expected, lacked any memorial aspect); and the Hang Duong cemetery site, two kilometres north of Con Son township, which was extensively renovated in 1992 and developed as a national memorial. The two most prominent French period burial grounds are the Bai So Nguoi and Hang Keo sites. The former is a somewhat nondescript sandy area in which an estimated 120 prisoners and Vietnamese guards who rebelled against the French in 1862 were buried.9 The Hang Keo site was the initial French prison cemetery area and is now a tree-filled remembrance space. All the remains from both sites have now been relocated to the Hang Duong cemetery.

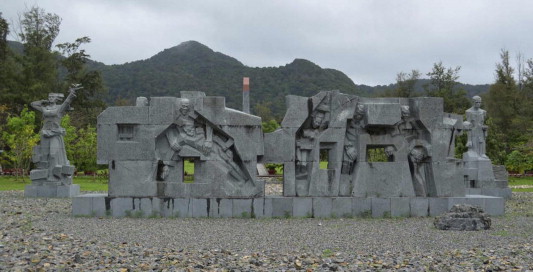

In contrast to the low-key Bai So Nguoi and Hang Keo sites, The Hang Duong cemetery covers an area of 20 hectares within which around 20,000 deceased prisoners have been buried, 712 of whom have been identified and are commemorated with individually named headstones. The cemetery is marked by an entrance facility (including a souvenir shop and café area) and large commemorative sculptures (Fig. 4) together with a central pillar accessed by stone steps that provides information about Con Son’s history. Along with these major memorial edifices, individual graves of particularly revered patriots are also major centres of attraction and visitation – as evidenced by both the fresh bouquets on them and frequent congestion around particular graves at peak visitation times, such as when coach parties arrive. Amongst the most visited graves are those of Le Hong Phong, the second leader of the Vietnamese Communist Party, who died in 1942; nationalist writer and activist Nguyen An Ninh, who died in 1943; and Vietnam’s most celebrated female revolutionary patriot, Vo Thi Sau. Sau was executed by firing squad on Con Son in 1952 after two years of imprisonment during which she actively defied prison rules. Sau was arrested by French authorities at the age of 16 after engaging in guerrilla activities (including grenade attacks on French forces and collaborating Vietnamese officials) and was the first female freedom fighter to have been executed by French forces. Her revolutionary zeal and early death, aged 19, have contributed to a cult-status for her – akin to that of secular revolutionary ‘saint’. There are two distinct pilgrimage sites associated with her, her grave at Hang Duong (Fig. 6) and a temple close to the seawall on the northern side of Con Son township (Fig. 5). While visitors to patriots’ graves routinely bring bouquets of flowers, offerings of rice meals, fruit or wine; Sau’s memorials are also subject to gifts of materials that reflect her youth and femininity (such as lipstick, mirrors, combs etc.) The visitors’ gifts are both marks of respect and also offerings that are made in anticipation of inspiration, guidance and/or good fortune deriving from the secular pilgrimage. One means by which visitors have attempted to gain the latter in recent years has been their attendance at Sau’s tomb between 11 pm and 2am, seen as a propitious time for access to her spirit (Con Dao Green Travel, nd: online).

Sau’s waterfront shrine is located within a small park that also contains statues celebrating human valour and determination in a manner that extends the specific commemorations of death in the cemetery sites into a broader public assertion of triumph over adversity. This results in an effective spatial differentiation between (in Miles’s terms) the ‘darkest’ sites of visitation, in the form of the prison buildings, and a ‘lighter’ memorialisation that exists along the seafront, directly facing out over the pristine bay and islands that lie offshore. In the case of the Phu Hai and Phu Son prison sites, their public entry is situated at the immediate rear of the Saigon-Con Dao hotel. The spatial alignment here is striking. One of the island’s plushest hotels is directly adjacent to one of the island’s darkest sites and directly overlooks the archipelago’s marine environment. This juxtaposition is a vivid symbol of the manner in which Con Son’s tourism has been able to combine (various shades of) thanatourism with engagement with the island’s natural beauty in a relatively stable package that embraces both elements. Indeed, Hang Duong cemetery embodies these aspects in a single site. The sheer scale of the cemetery and its major memorial structures indicate the mass of Vietnamese prisoners killed and interred there. This, and the Vietnamese visitors’ manifestly profound respect for and acts of tribute to the dead would suggest that the site is one of particularly dark thanatourism (in terms of Miles’s previously discussed characterisation). Yet the visitors’ and local population’s uses of the site are far less sombre than such a characterisation might suggest. Exemplifying Stone and Sharpley’s remarks that research into dark tourism requires acknowledgement of potentially “multi-tiered” experiences in different socio-cultural contexts (2008: 589); both local people and tourists use the entrance area and other areas within the graveyard as spaces for socialisation and leisure. This is particularly evident at night. Rather than the mass graveyard being a locked, prohibited and/or ‘spooky’ location after dark – in a manner familiar to western tourists, residents and/or tourism researchers – picnics, informal gatherings and social interactions centred on memorial facilities and/or individual graves are common. The social interactions that occur at Hang Duong represent members of the living community of Vietnamese communing with dead patriots, respecting them by including them and their experiences within the lived present of a Vietnamese society freed from foreign control due to their sacrifice. This affirmative interaction can also be seen to encompass Vietnamese tourists’ broader engagement with the archipelago’s natural heritage, their very access to this and ability to appreciate it being a direct result of successful nationalist struggles that re-unified the nation and allowed Con Dao to be opened up as a destination in which all Vietnamese can explore the nation’s past struggles, as exemplified in Con Son’s history and its natural beauty.

International tourism

As Tai emphasises in the course of her discussion of the memorialisation of Vietnamese history in the twenty-five years following the cessation of hostilities; foreign visitation, and various official and commercial accommodations of this, provide a “complicating factor” in Vietnamese engagements with the past, “allowing international actors as well as domestic ones to play a role in this work of re-vision” (2001:6). As she emphasises, the role these internationals play is complex in that:

The battle sites visited by French tourists are not the same as those that bring back American veterans, to cite but two groups of foreign visitors with their own time-specific memories of “Vietnam”, while others without personal ties to the country are drawn by the “timeless” beauty of its landscape and recreational facilities. (2001: 6)

With regard to Con Dao, which was not the site of any conflict (outside of early insurrections and the daily interaction of prisoners and jailors); the nature of and impetus for war heritage visitation is different in nature to the mainland. Most particularly, it is one in which foreign visitation has not promoted and packaged in a similar manner to mainland battlefields (presumably since the experience of being a foreign guard in a concentration camp is less redeemable than that of supposedly more ‘honest’ battlefield combat).

There are particular advantages and disadvantages to developing dark/thana- tourism for the local communities that host and cater for such visitors (see Austin, 2002). As Best identifies, in her study of tourism on Norfolk Island (2007), the activity is advantageous as it can generate visitation and related income in the wake of events that may have caused material, psychological and/or economic harm to regions and communities and can also “provide local and national governments with incentives to preserve and sustain sites, whilst also educating and entertaining visitors about convict history and heritage” (2007: 32). As she also notes, residents can capitalise on these incentives “by embracing and incorporating them into elements of local history and culture through museum displays, visitation to sites and providing both on and off-site interpretation” (2007: 31). In contrast to the clear economic benefits of such enterprises, Best contends that the thanatouristic memorialisation of particular sites can become problematic by focusing community attention on tragedies in a manner that might be harmful and/or inhibiting. The latter is not of course a necessary consequence of thanatourism, particularly if an area can offer a more diverse portfolio of attractions. With regard to World War Two concentration camp sites, for example; while the shadow of Auschwitz may prove to be deterministic on its location in southern Poland10; tourist visitation to other camp sites, such as Buchenwald, in central Germany, are more easily packaged together with other significant local attractions (such as the historic city of Weimar, known for being a centre of German Enlightenment philosophy and artistic expression in late 17th and early 18th centuries). Indeed, the profound contrast between such sites can generate a complex associative identity for areas that both allows visitors to engage with multiple attractions and enables them to balance and/or salve engagement with tragedy with more traditionally uplifting pursuits.

While Vietnamese tourism to Con Dao has been significantly motivated by heritage visitation to prison sites, there is no evidence that this aspect has been prominent in any marketing of the archipelago to Western tourists. With regard to Con Son town, which forms the geographical centre of the island’s tourism industry, the different nature of foreshore memorialisation and of the prison sites that are set back one block from the waterfront in the area where most hotels are clustered (together with a manifest absence of signs directing tourists from the bay-front to the prison site locations) at very least allows for, and arguably facilitates the overlooking of the darkest sites for non-Vietnamese tourists, particularly given the very different nature of promotion of the archipelago to this market.

Informal interviews conducted by the authors with western tourists on Con Son in 2013 and 2014 indicated a minimal awareness of prison heritage sites (despite some interviews being conducted within 2 min walk to the actual sites concerned). More extensive research of TripAdvisor postings (2012–2014) and other Internet travel blogs similarly demonstrated minimal awareness of and/or visitation to prison sites among western tourists, whose concerns and recommendations mostly concerned beaches, restaurants, hotels, biting insects etc. Indeed the only posting advocating the island’s prison history as a worthwhile attraction found by the authors was made in January 2014:

But there is so much more to do and see on Con Son - we spent 5 days here and filled our days with hikes and moped rides around the island, taking in the museums and the macabre history of the prisons (so important to visit these). (anonymous TripAdvisor posting, January 11th 2014)

While the poster did not specify why visiting these museum and prison sites was “so important”, we may speculate that s/he deemed them a significant facet of the island’s (and, perhaps, country’s) broader history. Despite this apparent lack of awareness and/or interest, it is significant that major tourism sites such as Lonely Planetdo identify aspects of prison heritage as significant elements of the island for visitors. Lonely Planet’s ‘Top things to do in Con Dao Islands’ page, for instance, (significantly written by a Vietnamese contributor) identifies the Revolutionary Museum as the sole museum and gallery attraction on the island and Phu Hai Prison as the sole architectural attraction, stating – with regard to the latter:

The largest of the 11 jails on the island, this prison dates from 1862. Thousands of prisoners were held here, with up to 200 prisoners crammed into each detention building. During the French era all prisoners were kept naked, chained together in rows, with one small box serving as a toilet for hundreds. One can only imagine the squalor and stench. Today, emaciated mannequins that are all too lifelike recreate the era. (Hoang, nd: online)

While the focus on the island’s early French prison period predates and thereby precludes reference to 20th Century history (and, in particular, US administration of the prison); the item is prominently displayed on The Lonely Planet site and thereby publicises the island’s heritage locations. It is however doubtful whether descriptions that emphasise historical “squalor” and “stench” and describe “lifelike” “emaciated mannequins” necessarily prompt international holiday-makers to visit the sites during their vacations. In these regards, the promotion of the archipelago to non-Vietnamese tourists has to reconcile the unambiguously attractive aspects of the region (ie its natural heritage) with aspects that are far less attractive for conventional leisure-orientated tourists, ie the ‘darkest’ forms of historical memorialisation of its prison history. At present there is no evidence of a conscious strategising of this duality in the marketing of the archipelago; rather a convenient default position prevails whereby the lack of extensive English (or other non-Vietnamese) language signage and guide books and/or the lack of local guides with adequate foreign language skills contributes to a far lower ‘visibility’ for prison era history and its memorial sites for foreigners than for Vietnamese visitors. In this manner, the role of international tourists and international tourism enterprises in Con Dao cannot yet be seen to have provided a significant “complication factor” in the maintenance of the archipelago’s prison heritage sites and heritage identity (but may come to do so if the future in the proportion of foreign visitors substantially increases).

Planning for development

In their provocative and insightful study of notions of sustainability in small island developing states, Baldacchino and Kelman (2014) characterised a “long war” waging in the early 21st Century concerning sustainable development, and, as pointedly, concerning the very nature of the latter concept. As they identify:

There are many sides and factions; but the battle-lines are stereotypically drawn between environmental groups and green parties on one hand and big and greedy corporate interests (with governments in their pockets?) on the other — notwithstanding huge disparities and often conflicts within all these groups. (2014: 1)

While this passage serves well as a general characterisation of global tendencies, the situation in Vietnam and, in particular, in Con Dao, is more complex. Planning and processes of approval for development in Con Dao in Vietnam’s post-reunification era have several layers of complexity and shifting “battle-lines” and intersections of special interests. One factor concerns the archipelago’s location at the south of the area known in Vietnam as the Eastern Sea (and more commonly referred to in English as the South China Sea). As a number of Vietnamese rulers have acknowledged,11 continued sustainable population of the islands represents a security measure, firmly binding the islands, and (in a contemporary context) their surrounding marine economic exclusion zones, into the national fabric, and providing credible deterrents from potential rival claims on the area.12 National security concerns consequently inform local planning developments. Con Son’s status as a national heritage site gives it national significance (particularly since many older Vietnamese leaders were imprisoned there) and all development plans related to the national park area, which represents 80% of the archipelago, are formally required to be approved at national government level. Approval for various developments may also have to be obtained from the Vietnamese Border Defence Force and/or national military. As this scenario suggests, local planning in and for Con Dao is a complex process. Similarly, while planning in the non-park areas of Con Son may appear to be somewhat more straightforward, the potential for developments in these areas to impact aspects of the environment and/or security of the broader archipelago also create substantial complications. Along with the nature of planning processes and mechanisms for stakeholder input there is – as might be expected – a broader set of issues concerning tensions between conservationist and developmental impulses, with the notion of sustainable development being the sensitive and disputed point of negotiation between the two. As a result of the latter, a number of independent reports and pilot projects have been undertaken which have had varying and partial impacts on subsequent planning in the archipelago. The main reports and related projects include Ross and Andriani (1998), Asian Development Bank (1999) and Ringer and Robinson (1999). These were, in the main, undertaken in response to the Con Dao District’s 1992 Master Plan for Development, a document that, amongst other items, projected an increase from the 1992 population of c1,800 to 10,000 by 201013 and required consideration of the environmental impacts of such an expansion.

Ringer and Robinson’s report on ‘Ecotourism Management and Environmental Education’ (1999), funded by the World Wide Fund for Nature (an international NGO concerned with eco-system protection) and the Vietnamese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, was based on both original research and a consideration of data and arguments presented in previous research (specifically Ross and Adriani, 1998 and Asian Development Bank, 1999). The report set out to address similar issues to those raised by Baldacchino and Kelman (above) in a particular local context by providing:

Specific recommendations and policies for developing and managing ecotourism and environmental education as tools for sustainable biodiversity conservation in marine and terrestrial areas of CDNP, and for sustainable community development for the people of Con Son island. (Ringer and Robinson, 1999: 1)

Various aspects of both the writers’ characterisations of their project and their “specific recommendations and policies” merit consideration here. The “and” in the final phrase of the above quotation is particularly telling on account of its ambiguity in identifying whether and to what extent “biodiversity conservation” and “sustainable community development” are connected and what “development” aspects of the community are being referred to. The writers’ subsequent itemisation of the intent of their study provides some clarification:

- Develop and promote Con Dao as an ecotourism destination for both foreign and domestic visitors;

- Financially support environmental conservation and education projects in the park and district;

- Provide economic benefits to the community; and

- Promote collaborative partnerships and constructive communication among the various stakeholders involved, including the national, provincial, and district governments, park managers, the police and military, non-government organizations (NGOs), private businesses and tour operators, educational institutions, local residents and visitors to Con Dao. (1999: 4)

Following this schematisation of intent, the authors provide a markedly tentative contention that, “it is hoped that ecotourism and environmental education together will be seen as an effective tool for proactively developing and managing the natural and cultural resources on Con Dao” (our emphases) in “a holistic manner” that is:

- (1)

- Sensitive to local concerns to conserve and protect the island’s significant natural and historic resources.

- (2)

- Supportive of efforts to provide viable economic alternatives for residents.

- (3)

- Sustainable environmentally and socially over the longer term. (1999: 4)

The wishful nature of the authors’ aspirations as to the report’s reception is apparent. This reflects the very real difficulty any Green-orientated development planning has in being able to engage and dialogue with groups interested in short-medium term commercial development initiatives as ends in themselves (let alone military/security interest groups that may prioritise their raison d’être over environmental factors).14 In this manner, while the report contains a number of eminently sensible, practical and well-argued proposals for tightly managed ecotourism projects and amenities; it only implicitly tackles the looming issue of how to address lobbies pushing for major tourism development and related population growth.

One of the crucial aspects to consider in addressing the above is that Ringer and Robinson’s project was specifically commissioned to address the Con Dao National Park (rather than the Con Son community or national and international business interests in the archipelago). The report therefore only partially overlaps with the concerns of the District’s Master Plan; indicating lower-scale and lower-impact development paths designed to increase tourism capacity and economic activity at a more modest scale than envisaged by the District’s planners. The fundamental irreconcilability of carefully considered environmental development plans and the aspirations of commercial interest groups seeking less restricted development is evident in subsequent planning initiatives and, most particularly, in the Vietnamese Ministry of Planning and Investment’s 2011 Social-Economic Development planning vision for Con Dao District (henceforth VMPI, 2011).

The VMPI policy document is notable for both addressing the wide range of concerns outlined in this article and – like Ringer and Robinson’s more tightly focussed report – being primarily aspirational in the manner in that it aims to maintain environmental integrity at the same time as promoting significant economic and population development. Key amongst the policy document’s goals and assertions is the creation of a “special territory zone” status for Con Dao that facilitates the development of “high-class” ecological tourism, resort and historic and cultural attractions (Article 1 Ia). It contends that these developments will allow the archipelago to become an “urban” hub for national and international marine and heritage tourism by 2020 (Article 1 Id). The document identifies a goal of attracting 150,000 tourist visits per year by 2020 (a 65% increase on current figures), which the report identifies as representing an 18–22% annual increase in income generation on Con Son. It also identifies that this will require/result in an increase of the current population of 6725 to between 15,000 and 20,000 by 2020 (Article 1 IIb). Beyond this, the policy statement identifies a further target of 250,000–300,000 tourist visits p.a. by 2030 (a 280–333%) increase on current figures which it envisages as serviced by a population of 30,000 (Article 1 IIb). Directly confronting the issue of environmental impact, rhetorically at least, the document stipulates that planning approval mechanisms will ensure that Con Son’s development areas will be restricted to 15% of the archipelago’s land mass and will operate within a “garden city” complex (Article 1 III). While the latter term is not defined, the document characterises that the archipelago will be “multi-centrally ecological” and “fundamentally connected to natural forest and marine environments” (Article 1 III). Article 2 assigns the responsibility for implementing the development initiative to the People’s Committee of Ba Ria-Vung Province, with Article 3 requiring diverse government ministries and agencies to assist in the implementation. As will be apparent from the above discussion, this is something of a ‘tall order’ in that the logistics of such an operation are barely hinted at.

Conclusion

One of the most significant aspects of the VMPI policy document is the manner in which its vision moves beyond imagining and representing Con Dao (and Con Son, in particular) as continuing to be dominated by prison heritage tourism. Instead, the document envisages the latter as becoming one aspect of an archipelagic tourism destination that interfaces with a broader south east Asian marine region (Article 1 Id).15 This is not an insignificant shift. Writing in 2001, reflecting on the first 25 years of Vietnam’s post–conflict memorialisation, Tai emphasised that one of the problems with manifestations of national public memory in the immediate post-conflict decades was a sense of profound uncertainty about Vietnam’s future (2001: 2). In a similar vein, Bodnar described post-conflict memory projects as serving “a myriad of purposes in the present” (2011: ix). Today, some forty-five years after the national reunification, it is possible to see the VMPI’s policy document as one of a number of official attempts to imagine Vietnam’s future as less constrained by the past than it may have appeared to have been in the late 20th Century. Indeed, we might go further and identify an implicit recognition in the document that national and local heritage is a living and shifting entity that adapts to new contexts that can be manifested in material landscapes in different fashions at different times. Indeed, if Con Son’s prison heritage period can understood to represent a national historical dystopia, the archipelago’s future, as imagined in the VMPI document, is fundamentally a utopian one. In the document’s vision, the archipelago’s history is not an over-determining aspect, in that its memorialisation can co-exist in a utopian, eco-friendly archipelagic ‘garden city’ in which various heritages can be accommodated without compromise. This draws on the integrated nature of thana- and conventional leisure tourism that has characterised domestic Vietnamese visitor experience in Con Dao to date, expanding it to become a signature element of the archipelago as it develops further as a national and international tourism destination. But while there is something undeniably inspirational in this vision, it is unclear how it is to be delivered. In particular, facilitating a projected population increase of around 450% together with a 330% increase in tourist visitation by 2030 in a small urban environment within a national park without negative environmental impact is likely to be a tough project. Although the VMPI policy document acknowledges this (Article 1 V) it gives precious few clues as to how the bodies charged with implementing the policy may fund and deliver the required eco-friendly infrastructural elements. The task for various stakeholders in reacting and adapting to the policy vision is a familiar one, ie managing the projected developments without precipitating environmental, social and cultural damage of the type that will degrade the very locale that it is attempting to exploit. In this regard, the most likely benefit of the VMPI’s utopian vision for the archipelago in 2030 is that problems concerning its implementation will both impede rampant development and encourage various degrees of ecologically-informed planning within the area.16

Thanks to Ilan Kelman for his comments on an initial draft of this article.

Endnotes

References

- Asian Development Bank, 1999 Asian Development Bank, 1999. ‘Draft Coastal and Marine Protected Areas Plan’ (Volume 2 of ADB 5712-REG Coastal and Marine Environmental Management in the South China Sea [East Sea] Phase 2).

- Austin, 2002 N.K. Austin Managing heritage attractions: marketing challenges at sensitive historic sites. Int. J. Tourism Res., 4 (1) (2002), pp. 447-457

- Baldacchino and Kelman, 2014 I. Baldacchino, I. Kelman Critiquing the pursuit of Island Sustainability. Shima: Int. J. Res. Island Cultures, 8 (2) (2014), pp. 1-21

- Bodnar, 2001 J. Bodnar Foreword. Ho Tai (Ed.), The Country of Memory: Remaking the Past in Late Socialist Vietnam, University of California Press, Berkeley (2001), pp. ix-xii

- CDNP, 2014 CDNP (nd) ‘About Con Dao National Park’, online at: <http://www.condaopark.com.vn/en/about.html> (accessed August 7th 2014).

- Con Dao District, 1992 Con Dao District, 1992. 1993–2010 ‘Master Plan’, Con Dao District Planning Office.

- Con Dao Green Travel, 2014 Con Dao Green Travel (nd) ‘Con Dao, vung dat cua tam linh’ (‘Con Dao – the psychical land’): <http://khamphacondao.vn/tin-du-lich/175-con-dao-vung-dat-cua-tam-linh.html> (accessed August 18th 2014).

- Foley et al., 1996 M. Foley, J.J. Lennon JFK and dark tourism: a fascination with assassination. Int. J. Heritage Studies, 2 (4) (1996), pp. 198-211

- Geman, 2011 Geman, K., 2011. ‘Isolated Con Dao Islands’, New York Times May 23rd, online at: <http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2010/05/23/travel/20100523CONDAO.html?_r=0> (accessed August 8th 2014).

- Graves, 1970 R. Graves How they unearthed the tiger cages. Life, 69 (3) (1970), p. 2A

- Harkin, 1970 T. Harkin The tiger cages of con son. Life, 69 (3) (1970), pp. 26-29

- Hayward et al., 2014 P. Hayward, S. Kuwahara Divergent trajectories: environment, heritage and tourism in Tanegashima, Mageshima and Yakushima. J. Marine Island Cultures, 2 (1) (2014), pp. 29-38

- Hoang, 2014 Hoang, V.L. (nd) ‘Architecture: Phu Hai Prison’, in Lonely Planet ‘Top things to do in Con Dao Islands’, online at: <http://www.lonelyplanet.com/vietnam/around-ho-chi-minh-city/con-dao-islands/sights/architecture/phu-hai-prison#ixzz3AKLeT5Ain> (accessed August 8th 2014).

- Lonely Plan, 2012 Lonely Planet, 2012. ‘The World’s best secret Islands’, online at: <http://www.lonelyplanet.com/travel-tips-and-articles/76176> (accessed August 8th 2014).

- Luce, 2010 Luce, T., 2010. ‘The tiger cages of Vietnam’, online at: <http://www.historiansagainstwar.org/resources/torture/luce.html> (accessed August 6th 2014).

- McDaniel, 2013 McDaniel, M., 2013. ‘Sensational Six Senses: Angelina Jolie’s little bit of paradise in Vietnam’, Daily Mail (Australia) February 17th, online at: <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/travel/article-2279950/Con-Dao-Six-Senses-Angelina-Jolies-little-bit-Paradise-Vietnam.html> (accessed August 6th 2014).

- Management Board Con Dao Relics, 2011 Management Board Con Dao Relics So luoc ve khu di tich lich su Con Dao va nhung truyen thuyet (‘A Summary account of Con Dao’s relics and legends’). Culture and Art Publishing house, Ho Chi Minh city (2011)

- Minh Mang, 1821 Minh Mang (King), 1821. ‘Imperial Ordinances of King Minh Mangvon Land Reclamation in Southern Vietnam, Cambodia and Poulo-Condore in the second year of his reign’ – document 7698 in Vietnamese National Archives Centre.

- Nguyen et al., 2012 Nguyen, D.T., 2012. Con Dao tu goc nhin lich su (‘Con Dao from an historical perspective’), Ho Chi Minh Publishing HouseNguyen, Ho Chi Minh city. T.P., Vo, N.M., Nguyen, Q., Khong, D.T., Trinh, M., Tran, T.T, Duong, M.H., Nguyen, T.T, Nguyen, D.C., 2010. Lich su dau tranh cua cac chien si yeu nuoc va cach mang Nha tu Con Dao (1862–1975) (‘The history of patriots and revolutionary fighters in Con Dao prisons (1862 – 1975’), National Political Publishing House, Hanoi.

- Ramsar, 2009 Ramsar, 2009. The Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance, online at: <http://www.ramsar.org/cda/en/ramsar-about-sites/main/ramsar/1-36-55_4000_0_> (accessed August 8th 2014).

- Ross and Andriani, 1998 Ross, M. and Andriani, I.A.D., 1998. Marine Biodiversity Conservation at Con Dao National Park. Institute for Environment and Sustainable Development, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Institute of Oceanography in Nha Trang, and Con Dao National Park.

- Seaton, 1996 A.V. Seaton Guided by the dark: from thanatopsis to thanatourism. Int. J. Heritage Studies, 2 (4) (1996), pp. 234-244

- Schwabe, 2005 Schwabe, A., 2005. ‘Holocaust Tourism: Visiting Auschwitz, The Factory of Death’, Spiegel Online International: <http://www.spiegel.de/international/holocaust-tourism-visiting-auschwitz-the-factory-of-death-a-338815.html> (accessed August 9th 2014).

- Stone and Sharpley, 2008 P. Stone, R. Sharpley Consuming dark tourism: A thanatological perspective. Ann. Tourism Res., 35 (2) (2008), pp. 574-595

- Tran, 2014 H.T.G. Tran Contested space. national and micronational claims to the Spratly/Truong Sa islands – a Vietnamese perspective. Int. J. Res. Island Cultures, 8 (1) (2014), pp. 49-58

- Unattribute, 2006 Unattributed, 2006. ‘Con Dao Vietnam to be combined world heritage’, Footprint Vietnam Travel website: <http://www.footprintsvietnam.com/vietnam_news/news789-06/Con-Dao-to-be-combined-world-heritage.html> (accessed August 17th 2014).

- Unattribute, 2013 Unattributed, 2013. ‘Former Con Dao Prisoners reflect’, Nhan Dan Online 28th July: <http://en.nhandan.org.vn/politics/domestic/item/1895202-former-con-dao-prisoners-reflect.html> (accessed August 16th 2014).

- Vietnamese Ministry of Planning and Investment, 2011 Vietnamese Ministry of Planning and Investment, 2011. ‘Decision on Approval of Overall Planning for Social-Economic Development of Con Dao District, Ba Ria – Vung Tau Province up to 2020, Vision 2030’ (1742/QD-BKHDT).

- Zinoman, 2001 P. Zinoman The Colonial Bastille: A History of Imprisonment in Vietnam 1862–1940. University of California Press, Berkeley (2001)