The curious case of Marco Polo from Korčula: An example of invented tradition

Institute for Anthropological Research, Zagreb, Croatia Olga.Orlic@inantro.hr http://www.inantro.hr/?lang=eng&id0=1&id1=9&id2=69&id3=196

Abstract

In this paper the author deals with the claiming of Korčulan identity for Marco Polo as an invented tradition. According to some, the combination of Korčulan archive data, Korčulan family names and some historical facts give the island’s inhabitants the opportunity to question Marco Polo’s “Venetian origin” and attempt to claim that he or his family originated on the island. The author analyzes the attitudes and opinions of local residents concerning the issue and discusses it in the framework of the concept of invented tradition. The contemporary use of Marco Polo name as a symbol for Korčula Island reveals its great potential for tourism.

Keywords

Korčula Island, Marco Polo, Invented tradition, Place marketing

Introduction

Beginning on 22 April, 2011, most of the media outlets in Croatia began reporting the response of the Italian newspaper Corriere della Serra to the news that the former Croatian president, Stjepan Mesić, had publicly proclaimed the Dalmatian (and therefore Croatian) origin of the “world’s first tourist” during the opening ceremonies of the Marco Polo Museum in Yangzou, China. Stella (2011) entitled his article, ‘Ecco Marko Polo, esploratore croato’ (Here is Marko Polo, the Croatian explorer) and appended the following subheading: ‘Se Zagabria ci scippa l’eroe del Milione. L’ex presidente va in Cina e celebra “il viaggiatore di Curzola” che ha avvicinato i due mondi’ (‘Is Zagreb kidnapping the hero of Il Millione’ (Travels of Marco Polo) Ex president had travelled to China and praised “the traveller from Curzola” (Italian name for Korčula Island) who had connected two worlds). Most of the media simply informed the public of the condemning tone of the Italian article and did not enter the debate. Croatian journalist Bešker (2011) commented that the Croatian claims to Marco Polo’s origin were nonsense and lacked historical validation, introducing a tone of mockery. However, he also criticised other statements and ideas expressed in the article. For example, he attacked the assertion that Korčula Island was completely Venetian because the Venetians had ruled the island for several centuries. Scotti (2011), a journalist for La Voce del Popolo, the daily newspaper of the Italians in Istria and Rijeka (Primorje), in an article entitled, ‘E dopo le amebe vennero i Croati (‘And after the amoebae the Croats came’), classified the Croatian claims to Marco Polo’s origin as a “theft of heritage” and even lambasted it as “the usual Croatian practice of stealing the Italian heritage”.

The aim of this paper is to analyse the attitudes of interlocutors from Korčula Island regarding the practice of using the name Marco Polo as a symbol of identity and as a brand name to promote tourism on the island. Marco Polo’s name was and still is used in connection with Korčula Island because of historical data connecting him or, according to some interpretations, his family name with the island (this will be discussed in detail below). I will not engage in the debate over Marco Polo’s “true” place of origin because it is not crucial to the purpose of this paper. Rather, I will focus on analysing islanders’ attitudes toward the usage of this famous name for promotional purposes, a phenomenon I will analyse as a type of “invented tradition” (Hobsbawm and Ranger, 1983). Therefore, I will not advocate any of the viewpoints in the birthplace controversy, especially because there are a dizzying number of claims over the origin of the Polo family, if not of Marco Polo himself. Furthermore, Croatian claims themselves are not homogeneous, as one might expect. Besides Korčula town (Ljubić, 1856: 255–256), Šibenik (Kukuljević Sakcinski, in 1845, according to Ledić, 1996: 69–70) and Blato (on the island of Korčula) (Protić, 1998) have also been suggested as possible places of Marco Polo’s origin. In this paper, I will focus on analysing the attitudes that the inhabitants of Korčula Island, and particularly the inhabitants of the town of Korčula (the island and the town share the same name), have toward Korčulan (island and town) claims to Marco Polo’s heritage. I argue that Marco Polo’s alleged origins in Korčula town can be analysed as a type of “invented tradition” (Hobsbawm and Ranger, 1983) whose truthfulness is not overtly questioned because its tourist potential is considered useful. Hobsbawm and Ranger complicated the concept of tradition(s) by demonstrating that traditions perceived as authentic, genuine and as having passed unchanged from generation to generation are actually often invented and/or constructed in a particular time and place and reshaped to fit the particular needs of the community to which they “belong”, the most famous example being the Scottish kilt.

The term “invented tradition” is used in a broad, but not imprecise sense. It includes both traditions actually invented, constructed and formally instituted and those emerging in a less easily traceable manner within a brief and dateable period – a matter of few years perhaps – and establishing themselves with great rapidity (Hobsbawm, 1983: 1).

Anthropologists who use this concept in their scientific approach are aware that it can become an “occupational hazard” (Jackson, 1989: 129), causing not only disappointment but also eliciting negative responses from the members of the community whose traditions are being deconstructed (Briggs, 1996: 436–438). In the field of Croatian ethnology and cultural anthropology, this is an even more delicate issue because of the basic insideness (Povrzanović Frykman, 2004: 87–90) of most Croatian and Eastern European ethnologists and cultural anthropologists, who are unable to focus their research on exotic and distant Others (Jakubowska, 1993 according to Capo Žmegac et al., 2006: 11). Calling tradition “invented” is often (mis)understood to mean falsified, which further complicates anthropological endeavours (Linnekin, 1991). Because one of the premises of invented traditions is that “where possible, they normally attempt to establish continuity with a suitable historic past” (Hobsbawm, 1983: 1), it is reasonable that the usual praxis is to provide relevant historical data supporting the thesis. In the case of Korčulan claims to Marco Polo’s origin, it should be noted that historians have only verified one fact connecting Marco Polo to Korčula island, namely, that he was captured near the island during a naval battle between Venetian and Genoese naval forces (Foretić, 1940: 70) and was imprisoned on the island for several days before being transferred to the Genoese prison where he dictated the book that made him famous (Gjivoje, 1969: 47–48). However, associating Marco Polo with Korčula Island became more popular after 1922, when Korčula became interested in tourist development. Gjivoje has mentioned that a reckless tourist guide began representing a house registered, at the time of his writings, to a branch of Depolo family as Marco Polo’s house (Gjivoje, 1969: 48). The “archival” argument, usually used by islanders supporting the Korčulan origin thesis, posits that the Depolo family name had existed in various forms, including Polo, Paulovich (Pavlovich), De Polo, Di Polo, and finally Depolo, on island records since the 13th century (Depolo, 1996: 95).

Many authors have discussed the Korčulan (or Dalmatian) origin of Marco Polo (Herceg, 1954; Šparac, 1971; Foretić, 1954). One author even counted all of the journals and newspapers accessible to him that mentioned a connection between Korčula and Marco Polo (Filippi, 2000). In 1996, the Croatian Academy of Arts and Sciences dedicated a scientific conference to “Marco Polo and the Eastern Adriatic in the XIII Century” (Padovan, 1996). At that conference, James A. Gilmore reported on the 1993 Europe-Youth Inaugural Conference held in Wales. On that occasion, Korčulan Mate Depolo, the Croatian representative at the event, opened the conference by staging the meeting of “his famous ancestor” (i.e., Marco Polo) (Gilmore, 1996: 117) with Kublai Khan (played by the representative from Mongolia). Gilmore stressed the necessity of opening an international Marco Polo centre in Korčula, a goal that was realised in 1997 (http://www.korcula.net/mpolo/mpolocentre.htm). Gilmore also emphasised the need to connect the already well-known name of Marco Polo with Korčula and Croatia to increase the number of tourists. Although he doubted the truthfulness of Korčula’s claim, Gilmore made its truth-value irrelevant by comparing it with pilgrimage sites made holy by sometimes unproven traditions, emphasising that “all travellers need a destination, whether it be true or legendary” (Gilmore, 1996: 130–132).

The Korčulan theory has also inspired several literary works, Marylin Sharp’s book, Masterstroke, being one of them (Filippi, 1995). ‘On the trail of Marco Polo’ is the title of a chapter in Marco Polo’s Isle, in which the author describes the island through his own experience as a residential tourist. In this chapter, he describes locals’ attempts to provide evidence supporting the Korčulan origin thesis (Donley, 2005).

The websites dedicated to Korčula Island usually mention Marco Polo and his connection with the island. However, they always mention the conflicting accounts of his origin.

Significantly, Polo is reputed to have been born in Korčula itself, although evidence to support this thesis is at best sketchy. Notwithstanding, Korčula town still boasts Marco Polo’s alleged house of birth. Despite its rather featureless interior, the houses’ tower (loggia) allows for a panoramic vista of Korčula, stretching from east to west. The house is under the protection of the Korčula Town Hall and it will soon be turned into a Museum of Marco Polo. If Marco’s place of birth is somewhat ambiguous, it is certain that he was taken prisoner by the Genoese in the naval battle of Korčula, between the Venetian and Genoese states. (http://www.korculainfo.com/marcopolo/) (see Fig. 1).

The information provided on this website is clearly truthful. The website makes no claim that Marco Polo definitely originated from Korčula, and the only known historical fact connecting Marco Polo, with Korčula island is presented without bias. This excerpt is a teaser to attract visitors (tourists) and does not make overt claims that could potentially draw accusations of dishonesty. Nevertheless, the uncertainty of Marco Polo’s origins does not prevent the use of his name as a recognisable symbol, even a brand. Numerous apartments, tourist agencies, hotels, local products (olive oil, cake, etc.) and festivals, and even a sports web portal have been named after Marco Polo. The story of Marco Polo’s Korčulan origins seems to have gained new impetus after the 1998 decision by the Korčulan Tourist Board, on the occasion of the 700th anniversary of the battle between the Genoese and Venetian fleets near Korčula Island, to stage a re-enactment of the naval battle and of Marco Polo’s capture and imprisonment. Since that occasion, the event has been held annually, becoming a (invented) tradition in its own right. Some authors are right in stating that this occasion was cleverly staged to promote Korčula as a tourist destination (Stipetić, 1998: 9). However, the trend of organising various medievalesque performances in Croatia has a long history. Picokijada in Đurđevac, for example, began in 1968. Such events have become much more popular in the past 15 years, however, and the roster now includes a historical re-enactment and festival called Rapska Fjera on the island of Rab, a knights’ tournament in Gornja Stubica, the staging of the naval battle between the Venetians and the Uskoks in Bakar, etc. Some authors see these examples from the eastern Adriatic coast as a festivalisation of history whose purpose is to establish and represent a Mediterranean character and identity (Škrbić Alempijević and Žabčić Mesarić, 2010).

The tourist activities on Korčula could lead one to conclude that islanders are trying to prove that the Polo family originated from the island, not Marco Polo himself. However, the purpose of these claims is to link the name of Marco Polo with the island, thus creating a sort of unofficial island brand that has yet to undergo the top-down branding process Grydehøy called “branding from above” (Grydehøy, 2008).

Historical background

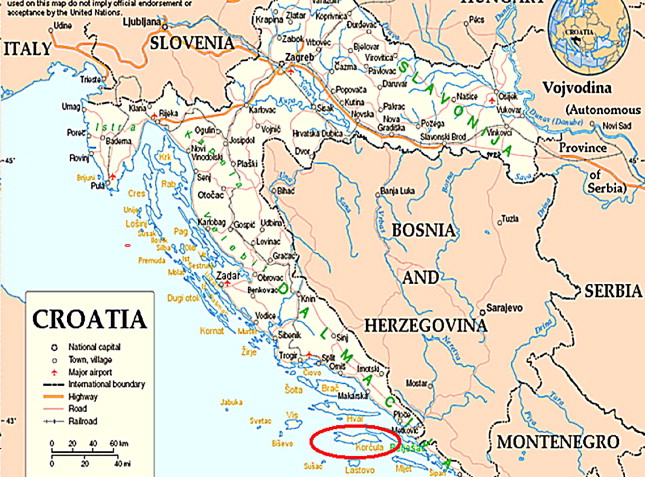

Korčula is an island in the southeast region of the Adriatic Sea (see Fig. 2). The island was colonised by Greeks in the 4th century BC and named Kóρκυρα Mέλαινα (Korkira Melaina, the Black Korkira). According to Apollonius of Rhodes, the Argonauts named the island while passing nearby, supposedly for its abundance of forest (Foretić, 1940: 19). The Romans continued to call the island Corcyra Nigra. After the fall of Roman Empire, the island came under the administration of many rulers. Some of them ruled for generations, such as the Venetians (1420–1797) and the Habsburgs (1815–1918), while others remained on the island only for a brief period (Gjivoje, 1969: 52–53). After World War I, the island was occupied by the Italian regime and later became part of the Kraljevina SHS. During World War II, the island was occupied by the Italians and the Germans, and after 1944 it became the part of FNR Jugoslavija. After the Croatian War of Independence, it became part of the Republic of Croatia. Slavic people began to inhabit the island in the 7th century, and in the 10th century, the Byzantine emperor Constantine Porfirogenetus noted its Croatian name, Kurka or Krkar, in his book De administrando imperio (Foretić, 1940: 28). Today, according to the most recent census, the island has 15,522 inhabitants (Popis stanovništva, kućanstava i stanova u 2011. godini, 2011).

In addition to the alleged Korčulan origin of Marco Polo, the island’s sword dancing tradition (a selected tradition (Williams, 2001 (1961)) and perhaps also a type of invented tradition) has interested anthropologists, ethnographers, ethnochoreologists, musicologists and folklorists (e.g., Vuletić Vukasović, 1891; Ivančan, 1974, 1985; Foretić, 1955, 1974; Palčok, 1974; Lozica, 1999, 2002; Ivancich Dunin, 2001, 2002; Marošević, 2002; Čale Feldman, 2003; Niemčić, 2008 etc.). Two types of sword dances are performed on the island: Moreška (exclusively in Korčula town) and Kumpanija/Kumpanjija/Moštra (performed in the villages of Žrnovo, Pupnat, Blato, Smokvica, Čara and Vela Luka). Sword dance variants were known to have been performed along the eastern Adriatic coast (Marošević, 2002: 113), but only on Korčula Island have they been “preserved”. Sword dances continue to be performed on Korčula and are important symbols of local identity/ies. Although Korčulan sword dances are represented by Korčulans as unique (and the Korčulan variants certainly are), sword dances are known to have existed across Europe (Foretić, 1974: 19; Ivančan, 1985: 372; Forrest, 2001:117), and the globe; variants have even been “discovered” in Mexico (Foretić, 1974: 19; Ivancich Dunin, 2001).

Methodology

In this paper, I will analyse results obtained through the application of qualitative methodological tools. Semi-structured, in-depth interviews and ethnographic observation conducted during field research were used to collect the data. Researchers from the Institute for Anthropological Research conducted field research on Korčula Island in July and September 2008 and February 2009 under the auspices of the “Contemporary transformations of local linguistic communities and cultural diversity” project. The project’s methodology included both qualitative and quantitative procedures, but this paper will analyse only the qualitative results, with one exception (this exception, I believe, significantly contributed to answering the research question).

The researchers who participated in the above-mentioned research project conducted interviews with 107 interlocutors from each of the major settlements on the island (Korčula town, Blato, Vela Luka, Žrnovo, Lumbarda, Smokvica, Čara, Račišće and Pupnat, see Fig. 3). The interlocutors were recruited through the researchers’ social network and later via the snowball method. In situ recruitment was also used, but infrequently. The interviews were semi-structured, and the protocol consisted of several thematic topics that were, if possible, covered during the interview. However, the narrative style of the interlocutors was encouraged whenever possible. All interlocutors gave oral informed consent for the interview and were guaranteed anonymity. The thematic topics included, in addition to personal or (in some cases) family history, questions dedicated to issues such as identity, language, culture, traditions, symbols of local identity, the impact of tourism on daily life on the island, etc.

The goal of the research project was to understand and explain identification processes on the island, the new configurations of which were thought to have been triggered by the Croatian War of Independence and the country’s subsequent sovereignty and by the contemporary context of “European integration”. Tourism, as an important factor in daily life on the island since its emergence in 1898 and its rapid development after WWII (Gjivoje, 1969: 179), also interested the researchers involved in the project. Both within and outside of the context of tourism, the name of Marco Polo was frequently mentioned in the interviews and in informal conversations with the islanders. The impossibility of avoiding the name of Marco Polo and his alleged Korčulan origin intrigued me. This interest triggered my research into the contemporary use of Marco Polo’s name as an invented tradition and an important resource for tourist promotion.

Findings – attitudes toward the (possible) Korčulan origins of Marco Polo

The findings can be divided into three categories that describe interlocutors’ attitudes toward Marco Polo’s supposed Korčulan origin. I have named these three attitudes according to their characteristics: suspicious, advocacy and instrumentalist.

As I have mentioned, Marco Polo was mentioned frequently by our interlocutors during the interviews, especially when discussing symbols of identity connected with the island:

Researcher: What first comes to your mind when Korčula Island is mentioned?

Male Interlocutor, from Balto: Marco Polo.

Female Interlocutor, from Žrnovska Banja but originally from Korčula town: First of all, that it is the town of Marco Polo.

Male Interlocutor, from Korčula town: Look, in Korčula (town) it is quite specific. Korčula as a town has certain symbols… from Marco Polo to Moreška, and now KPK, the Korčulan swimming club. And so on.

Researcher: Is there a symbol of Korčula town?

Female Interlocutor, from Korčula town: Yes there is… Marco Polo and Moreška. This is something that we have and others do not, right?

It appears that, regardless of Marco Polo’s “real” birthplace, his name has become a dominant symbol of the town and the island. This pattern is even more apparent in a survey conducted among the island’s high school students (n = 534). The aim of the survey was to reveal attitudes towards the language varieties (matched-guise test; Lambert et al., 1960/66), but the survey contained several additional open-ended questions. One of these questions prompted participants to name the top three things they associate with Korčula Island. A variety of answers to this non-leading question were expected. The sea, unsurprisingly, took first place; 188 of 534 students associated the sea with Korčula Island. However, Marco Polo was mentioned by 64 students. The Moreška sword dance was also mentioned by 64 students, and the Kumpanija sword dance by 19 students. These results suggest that Marco Polo has become an important symbol of the island.

In the following sections, I will discuss the suspicious, advocacy and instrumentalist approaches in greater detail and demonstrate the differences in inhabitants’ attitudes toward Marco Polo’s connection with Korčula Island and the use of his name as a brand.

Suspicious approach

Interlocutors who took a suspicious approach were doubtful of the supposed Korčulan origin of Marco Polo and/or of the Polo family. Most interlocutors viewed the issue positively even while expressing doubt. Therefore, I decided to label this group “suspicious”. More precisely, this group is “suspicious about the authenticity of Marco Polo’s house” because the majority of interlocutors reported their doubts about the house without referring to the origins of Marco Polo or the Polo family. As a male interlocutor from Korčula town said, “And now, this story about Marco Polo’s house is… It is… It’s a public secret that it is such a lie, and this is terrible!”

The main argument among the suspicious group was that the house had been built long after Marco Polo’s lifetime, which invalidated its connection to the Polo family. Some interlocutors even offered more precise details about the “history of making Marco Polo’s house”:

Male Interlocutor, incomer living in Korčula town: The lady from X, she put a label on the house stating that it is Marco Polo’s house and made a brand out of it… There is no scientific evidence.

Male Interlocutor, from Korčula town: No way. [Laughter] The house was [built] two hundred years later than he was born… The whole of Korčula [town] was [built] two hundred years later.

Male Interlocutor, incomer living in Korčula town: I think the house has nothing to do with it. I think the town had much bigger and smarter building priorities... And the intention of this investor, I tell you, one was our man, the other was a Dutch… They didn’t want to make it their own private house, but public space. And they would have finished it much earlier and decorated it much better… Because, now the town [city council] bought the house.

Some interlocutors even mentioned that the house had been sold to “some Dutch people” by Korčula municipality, only to be repurchased at a higher price. Although this does not necessarily inauthenticate the house, it shows that the house’s tourist potential was recognised (albeit too late) by the local authorities. This group of attitudes expresses suspicion about the house’s authenticity. These interlocutors do not, however, assert that the allegations about Marco Polo’s origins are false.

Advocacy approach

Interlocutors who took the advocacy approach argued for the Korčulan origin of Marco Polo. This group’s attitudes agree with the archival arguments mentioned earlier in the paper. However other documents supporting this thesis were also mentioned.

In the entry for “Marco Polo”, The Croatian encyclopaedia states that the belief that Marco Polo was born in Korčula is based on a 15th century document, according to which the Polo family originated in Dalmatia (Hrvatska enciklopedija 8, 2006:19). The manuscript in question is the “Chronicle of Venetian history since its beginning until 1446”, but another author claims the reference is to “La vite dei dogi” (Depolo 1996: 89).

Male Interlocutor, incomer living in Korčula town: Grounded, yes. … Here the Depolo family exists; this is his supposed origin…

Male Interlocutor, from Korčula town: I told you, there is no concrete certificate, in fact, written proof that he was born in Korčula. ... In any case, there are lots of indications, even the Italians themselves said that Korčula, in fact Dalmatia, that Korčula is Dalmatia… … Encyclopaedia Britannica also says, that here [on Korčula island] there are families with that surname Da Polo…

Intrigued by the final quotation, I investigated this claim by referencing the 1998 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. In the index, the name Marco Polo is accompanied by a bracketed note “(It. expl.), see Polo, Marco” (Encyclopaedia Britannica Index, 1998: 140). As in most encyclopaedias, the entry for Marco Polo summarises basic information about his date and place of birth. Interestingly, although the entry classifies him as a “Venetian merchant”, it states, “b.c. 1254, Venice [Italy] or Curzola, Venetian Dalmatia [now Korčula, Croatia]-d. 8. Jan 1324, Venice”. In explaining how Marco Polo’s book was compiled, this entry classifies the famous battle in which Marco Polo was captured as a “skirmish or battle in the Mediterranean” but does not mention that the naval battle took place near the island of his supposed origin (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9, 1998: 571–573). The entry for Korčula Island states that “Korčula is the reputed birthplace of the traveller Marco Polo in about 1254 and is a popular tourist resort” (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9, 1998: 956). Though this entry remains unaltered in the online Encyclopaedia Britannica, the entry for Marco Polo mentions only one possible birthplace: Venice (Encyclopedia Britannica Online, 2011).

Some interlocutors rationalise the Korčulan origin theory by citing the relationship between centre and periphery at the time of the Venetian Republic. One male interlocutor from Korčula town drew a parallel between the Republic of Venice and the situation in the former Yugoslavia, suggesting that all inhabitants of the Republic of Venice in Marco Polo’s time were considered Venetians:

I have a theory of my own. I was born in X [A city that is today a part of the Republic of Serbia]. It was Yugoslavia at the time. Am I therefore a Yugoslavian? [Long pause, implying negative answer to the question] It is the same with Korčula. At that time, it was under Venice. Venice was not the exclusive name for the town. It was the name of the whole Republic.

Instrumentalist approach

Interlocutors who took an instrumentalist approach did not debate the truthfulness of the story of Marco Polo’s Korčulan origins. Instead, they emphasised and described its active utility for the purposes of tourist marketing.

Female Interlocutor, from Korčula town: It is important to be recognisable… Marco Polo has resurrected in the past ten years!

Male Interlocutor, from Korčula town: Today we have the Marco Polo battle, Marco Polo restaurants, display of the lifestyle from the period of Marco Polo – clothing from the times of Marco Polo, decorating streets in the manner of Marco Polo’s epoch…

Researcher: What do you think about the claim? Is it true or false?

Female Interlocutor, from Korčula town: Well, there certainly is something… There was a battle, and he was captured here in the channel… And that is true, historically documented, right? And now, if he lived here, if his house is here… We will leave this to the historians… [Laughter]

Female Interlocutor, from Lumbarda: It is good, it is not bad... at all. Verona has its Romeo and Juliet... And... But it is unlikely that the evidence will be found… As, as a story for the tourists, it’s OK. I do not think it could be a problem.

Female Interlocutor, from Korčula town: And they will then always state that it was their greatest pleasure to be married in Korčula town, the town of our seaman Marco Polo, famous all over the world.

Male Interlocutor, from Korčula town: But I think that our people, starting with the local authorities, heading towards the Government itself, they are as... In fact, it could have been used much earlier and much better. They even used to say that the house he was born in was not his, that it was not the style of his epoch. How many styles have changed since then? Nobody has seen Our Lady of Međugorje, and Međugorje developed quite a lot because of it… Tourists come in the millions…

Over the past 20 years, Croatia has frequently identified itself as “belonging to Europe” instead of the Balkans and has emphasised the Croatian “contribution to Europe” (Rihtman-Auguštin, 1997: 27). Some interlocutors mention Marco Polo in the context of this discourse.

Female Interlocutor, from Pupnat: Starting from Marco Polo, who made the journey to Asia, to all the people from Korčula who did quite a lot for Europe.

Female Interlocutor, from Korčula town: A lot of people think that we have history and other things that make reasons to show off in Europe. … That we have [created] solid basis for Europe. For example, you have mentioned Marco Polo. Here, to us, he doesn’t mean a thing, but he represents the great name in Europe, for example.

This attitude was common among the interlocutors. It reifies and justifies the use of Marco Polo’s name for the purposes of tourist promotion. The name has become a brand, and people belonging to this group are not seeking irrefutable evidence that will determine the actual truth of Marco Polo’s origins and successfully resolve the issue. Instead, they are using the name as a resource to fulfil their current goals. Some of them are even using the name of Marco Polo to express or even “prove” the European identity of Croatia.

Analysis and concluding remarks

The story of the Korčulan origin of Marco Polo and/or his family can be approached as pure falsification or even as a theft of heritage; as a true fact, the truthfulness of which has yet to be proven; or as an effective means of achieving a goal, regardless of truthfulness. Because the name Marco Polo is verifiably associated with the 1298 naval battle near the island, the combination of historically proven fact and anecdotal evidence of his Korčulan origins creates an efficient means of promoting local tourism. A similar phenomenon has been observed on La Gomera, Canary Islands. Because the Port of San Sebastian was a point of departure for Columbus’ voyage, the island has been nicknamed “La Isla Columbina” (The Island of Columbus) (Macleod, 2004: 42–43). Macleod, however, stresses that the native inhabitants do not use this name, and the term seems to be an attempt by the “colonisers” to promote Spanish heritage (Macleod, 2010: 68). The reaction of these islanders differs from those on Korčula; the inhabitants of Korčula island seem to accept Marco Polo as the symbol of the island, even if they have doubts about his or his family’s origin. The authenticity (in the essentialist sense) of Marco Polo’s or his family’s Korčulan origins does not seem to be of crucial importance to the islanders or tourists. It would, however, be useful to explore tourists’ opinions about these claims and about their experiences at tourist destinations such as Marco Polo’s house. The interlocutors did not insist on objective authenticity, which suggests that “recognition of the toured objects as authentic” was sufficient (Wang, 1999: 351). The interlocutors insisted instead on constructive authenticity, which Wang calls a “social construction, not an objectively measurable quality of what is being visited. Things appear authentic not because they are inherently authentic but because they are constructed as such in terms of points of view, beliefs, perspectives, or powers”. Wang adds that the concepts of object-related authenticity and activity-related authenticity are not related to the toured objects but refer instead to the tourists’ experiences (Wang, 1999: 352). Because tourists have not been included in this research, I am unable to state whether or not tourists view the visiting of Marco Polo’s birthplace (the house, the town or the island) as an existentially authentic experience. Such information could be a valuable addition to the knowledge available on the subject because it could demonstrate to what extent tourists accept invented tradition.

Marco Polo’s house has, however, become an object of the “socially organised” “tourist gaze” (Urry, 2002: 1) in Korčula town, and Marco Polo has become the island’s symbol. By Taere’s definition (R. Teare, in Jafari, Jafari, 2000: 55), “a name, symbol, term, design, or any combination of these used to differentiate products or services from those of competitors” represents a brand. Therefore, it appears that Marco Polo has become an unofficial brand, a brand created through the process of “branding from below” (as opposed to “branding from above”, a term Grydehøy uses when describing the top-down praxis of creating the generic cultural brands of Shetland island (Grydehøy, 2008: 180) and islands in general).

The increasing competitiveness of all types of tourism (Richards 1996: 10) motivates the implementation of place marketing processes on all possible levels to attract tourists. Paliaga (2007: 140) notes that cities worldwide have recognised the importance of branding in increasing a location’s competitiveness. Such practices not only attract investors and tourists but also influence residents. This is the case for the town and island of Korčula. One need not be an expert in marketing and/or advertising to see the advantage of using Marco Polo’s name, especially for tourism purposes. According to instrumentalist approach the main aim is to attract tourists and this is the primary justification for the contemporary use of Marco Polos name on Korčula Island. Simultaneously, Marco Polo’s Korčulan origins are used to affirm Croatia’s Mediterranean-ness within the discourse of European belonging (i.e., not Balkan belonging (Rihtman-Auguštin, 1997: 27)). This attitude is typical in this part of Europe because of the way the Balkans have been imagined (Todorova, 2006), revealing an additional agenda for Korčula’s branding. Croatians declare their Mediterranean-ness to assert their European-ness, or identification with European civilisation. In doing so, they reveal their ascription to Europe-centric definitions of the “real” Europe, which has traditionally been defined by its Greco–Roman legacy, Christianity, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, etc. (Padgen, 2002). Associating itself with Europe seems to be important for Croatia, which only recently gained its sovereignty. Because it is currently in the process of “European integration”, the country desires to avoid being lumped with “the Balkans”.

Williams (2001 (1961): 67) argues that traditions result from processes of selection undertaken by each generation. In this sense, contemporary residents of the town and island of Korčula have chosen the “tradition” of Marco Polo’s Korčulan origins to represent them for broader purposes than tourism alone. I conclude that Korčulan claims to be Marco Polo’s birthplace or to be the origin of the Polo family name are an example of invented tradition. This particular invented tradition has been selected by the present generation of Korčulani (inhabitants of Korčula island/town) to serve their current purposes, whatever these might be.

Describing the first re-enactment of the 1298 battle on 7th September 1998, an anonymous journalist for the Globus magazine summarised the opinions of the Korčulan people: “If Venetians had not attacked Genoese people near Korčula, and if Polo had not defended the land of his ancestors so courageously and was therefore captured, humanity would be deprived of this masterpiece of literature” (Globus, N.N, 1998: 87). According to one of the event organisers, who was also the owner of the Marco Polo Tourist Agency, the event promoted more than just Korčulan tourism:

The aim was not to show that Marco Polo was a born Korčulan because one can only speak of his Korčulan origins. We wanted to mark this great historical event that took place here in the aquatorium of Korčula, and the staging of Marco Polo’s arrival on the island is a part of local patriotic folklore and our wish to symbolically display Polo’s connection with Korčula (Globus, N.N, 1998: 87).

It is impossible to determine whether Marco Polo’s name would have become such a strong symbol of island identity if tourism had not been developed on the island. However, because Korčula island had become one of the most attractive destinations for tourists by the end of 19th century, it is clear that the island profited, at least on a symbolic level, from using this famous name for the purposes of tourist marketing. The results of this research show that Marco Polo’s connection with Korčula Island is widely accepted among the inhabitants of the island and that his name became a strong symbol of island identity. The reasons for this are multiple and are not exclusively related to tourism. For instance, Marco Polo’s name is strongly associated with the idea of European-ness because his achievements correspond to perceived European values. Therefore, connecting Marco Polo’s name to the island seems to be important to a country that is striving to be perceived as a “real European” country. Regardless of the final results of the “search for the origins of Marco Polo”, it seems that Marco Polo has become a Korčulan, at least while his utility lasts. As one male interlocutor from Vela Luka concluded during an interview, “Marco Polo is, in some way, nevertheless a Korčulan, in any case”.

Acknowledgements

This paper represents part of the research project Contemporary transformation of local linguistic communities and cultural diversity, carried out at the Institute for Anthropological Research in Zagreb under the leadership of Professor Anita Sujoldžić. The project was made possible by a grant from the Ministry of Science, Education, and Sports of the Republic of Croatia (MZOŠ RH 196-1962766-2743).

References

- Briggs, 1996 C.L. Briggs The politics of discursive authority in research on “invention of tradition”. Cultural Anthropology, 11 (4) (1986), pp. 435-469

- Čale Feldman, 2003 L. Čale Feldman Morisco, moresca, moreška: agonalni mimetizam i njegove interkulturne jeke. Narodna umjetnost, 40 (2) (2003), pp. 61-80

- Čapo Žmegač et al., 2006 Čapo Žmegač, J., Gulin Zrnić, V., Šantek, G.P., 2006. Etnologija Bliskoga. Poetika i politika suvremenih terenskih istraživanja. In: Čapo Žmegač, J., Gulin Zrnić, V., Šantek, G.P. (Eds.), Etnologija bliskoga: Poetika i politika suvremenih terenskih istraživanja. Institut za etnologiju i folkloristiku, & Naklada Jesenski i Turk, Zagreb, pp. 7–52.

- Depolo, 1996 Depolo, V., 1996. Podrijetlo obitelji Polo i njezine veze s Korčulom. In: Padovan, I. (Ed.), Marko Polo i istočni Jadran u 13. stoljeću. Hrvatska Akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, Zagreb, pp. 89–96.

- Donley, 2005 M. Donley Marco Polo’s Isle. Spencer and Glynn, Otley (2005)

- Forrest, 2001 J. Forrest Rana povijest plesa morris u Engleskoj: primjer za istraživanje europskoga folklornog plesa. Narodna umjetnost, 38 (2) (2001), pp. 117-128

- Foretić, 1940 V. Foretić Otok Korčula u srednjem vijeku do g. 1420. Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, Zagreb (1940)

- Foretić, 1954 V. Foretić Da li je Marko Polo Korčulanin? Mogućnosti. Split, 10 (1954), pp. 683-693

- Foretić, 1955 V. Foretić Prilozi korčulanskoj moreški. Građa za povijest književnosti Hrvatske, 25 (1955), pp. 239-263

- Foretić, 1974 V. Foretić Povijesni prikaz korčulanske moreške. V. Foretić (Ed.), Moreška - korčulanska viteška igra, Radničko kulturno-umjetničko društvo Moreška, Korčula (1974), pp. 5-70

- Gjivoje, 1969 Gjivoje, M., 1969. Otok Korčula, own edition. Korčula.

- Gilmore, 1996 Gilmore, J.A., 1996. Marco Polo and the Europa-Youth Initiative. In: Padovan, I. (Ed.), Marko Polo i istočni Jadran u 13. stoljeću. Hrvatska Akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, Zagreb, pp. 125–133.

- Grydehøy, 2008 A. Grydehøy Branding from above: generic cultural branding in Shetland and other islands. Island Studies Journal, 3 (2) (2008), pp. 175-198

- Herceg, 1954 Herceg, J., 1954. Korčulanin Marko Polo: prvi evropski istraživač Dalekog Istoka. Split: Odbor za proslavu 700-god. Marka Pola.

- Hobsbawm and Ranger, 1983 E. Hobsbawm, T. Ranger The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1983)

- Ivancich Dunin, 2001 E. Ivancich Dunin Oznake u vremenu: kostimi i scenske značajke izvedbi bojevnih mačevnih plesova. Narodna umjetnost, 38 (2) (2001), pp. 163-174

- Ivancich Dunin, 2002 Ivancich Dunin, E. (Ed.), 2002. Proceedings Symposium Moreška: Past and Present (2001-Korčula). Institut za etnologiju i folkloristiku, Zagreb.

- Ivančan, 1974 I. Ivančan Ples i plesni običaji vezani uz morešku. V. Foretić (Ed.), Moreška-Korčulanska Viteška Igra, Radničko kulturno-umjetničko društvo Moreška, Korčula (1974), pp. 93-160

- Ivančan, 1985 I. Ivančan Narodni plesni običaji južne Dalmacije: narodna plesna kultura u Hrvata. Kulturno-prosvjetni sabor Hrvatske, Zagreb (1985)

- Jackson, 1989 J. Jackson Is there a way to talk about making culture without making enemies?. Dialectical Anthropology, 14 (2) (1989), pp. 127-143

- Lambert et al., 1960 W.E. Lambert, R.C. Hodson, R.C. Gardner, S. Fillenbaum Evaluational reactions to spoken languages. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66 (1) (1960), pp. 44-51

- Ledić, 1996 Ledić, G., 1996. Zaboravljene stranice o Marko Polu, Polusu, Paulusu u hrvatskoj bibliografiji. In: Padovan, I. (Ed.), Marko Polo i istočni Jadran u 13. stoljeću. Hrvatska Akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, Zagreb, pp. 69–82.

- Linnekin, 1991 J. Linnekin Cultural invention and the dilemma of authenticity. American Anthropologist, 93 (1991), pp. 446-449

- Lozica, 1999 Lozica, I. 1999. Čarska kumpanija. In: Foretić, M. (Ed.), Zbornik Čare (1). Župni ured Čara, Mjesni odbor Čara & PZ “Pošip” Čara, Čara, pp. 233–263.

- Lozica, 2002 I. Lozica Čarska kumpanija. Poganska baština, Golden marketing, Zagreb (2002)

- Ljubić, 1856 Ljubić, Š., 1856. Dizionario biografico degli uomini illustri della Dalmazia, Vienna. <http://books.google.com/books?id=oXPRAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=hr&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false> (accessed 20 July, 2011).

- Macleod, 2004 D. Macleod Tourism, Globalisation and Cultural Change. An Island Community Perspective. Channel View Publications, Clevedon, Buffalo, Toronto (2004)

- Macleod, 2010 D. Macleod Power, culture and the production of heritage. D. Macleod, J. Carrier (Eds.), Tourism, Culture and Power: Anthropological Insights, Channel View Publications, Ontario, Bristol, Tonawanda (2010), pp. 64-89

- Marošević, 2002 G. Marošević Korčulanska moreška, ruggiero i spagnoletta. Narodna umjetnost, 39 (2) (2002), pp. 111-140

- Niemčić, 2008 I. Niemčić When the stage lights go down: on silenced women’s voices, dance ethnography and its restitution. Narodna umjetnost, 45 (1) (2008), pp. 167-182

- Padgen, 2002 A. Padgen The Idea of Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2002)

- Padovan, 1996 Padovan, I., 1996. ‘Uvod – Otvaranje znanstvenog skupa. In: Padovan, I. (Ed.), Marko Polo i istočni Jadran u 13. stoljeću. Hrvatska Akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, Zagreb, pp. 9–12.

- Palčok, 1974 Z. Palčok Muzika korčulanske moreške. V. Foretić (Ed.), Moreška - korčulanska viteška igra, Radničko kulturno-umjetničko društvo Moreška, Korčula (1974), pp. 161-196

- Paliaga, 2007 Paliaga, M., 2007. Branding & konkurentnost gradova, own edition. Rovinj.

- Povrzanović Frykman, 2004 M. Povrzanović Frykman “Experimental” ethnicity: meetings in the diaspora. Narodna umjetnost, 41 (1) (2004), pp. 83-102

- Protić, 1998 Protić, I.1998. Marko Polo-potomak hrvatskog roda Zmaj.In: Protić, I.Župa Blato, own edition, Blato, pp. 98-102., available at <http://www.korcula.net/mpolo/marko_polo_protic.htm> (accessed on 25th July, 2011).

- Richards, 1996 Richards, G., 1996. Cultural Tourism in Europe. Wallingford, Cab International, Wallingford, or: Atlas 2005. <http://www.tram-research.com/cultural_tourism_in_europe.PDF> (accessed on 25th June, 2011).

- Rihtman-Auguštin, 1997 D. Rihtman-Auguštin Zašto i otkad se grozimo Balkana?. Erasmus – časopis za kulturu demokracije, 19 (1997), pp. 27-35

- Škrbić Alempijević and Žabčić Mesarić, 2010 N. Škrbić Alempijević, R. Žabčić Mesarić Croatian Coastal Festivals and the construction of the Mediterranean. Studia Ethnologica Croatica, 22 (2010), pp. 317-337

- Šparac, 1971 J. Šparac Dokumenti o Korčulaninu Marku Polu. Turistički biro i Turističko društvo Korčula, Korčula (1971)

- Williams, 2001 (1961) R. Williams The Long Revolution. Broadview Press, Canada (2001). (reprint, 2nd Chapter)

- Stipetić, 1998 Stipetić, V., 1998. ‘Sedamsto godina putovanja Marka Pola’ Forum, 9–10.

- Todorova, 2006 M. Todorova Imaginarni Balkan. (second ed.), Biblioteka XX vek & Čigoja štampa, Beograd (2006)

- Urry, 2002 J. Urry The Tourist Gaze. Sage Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi (2002)

- Vuletić Vukasović, 1891 V. Vuletić Vukasović Narodni običaji na otoku Korčuli. Matica Hrvatska, Tisak dioničke tiskare, Zagreb (1891)

- Wang, 1999 N. Wang Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 26 (2) (1999), pp. 349-370

- Globus, 1998 Globus, N.N., 1998. Vol. 405, 11th September 1998, 84–85 and 87.

- The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1998 Safra, J.E., Yannias, C.S. Goulka, J.E. (Eds.), 1998. The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., Chicago, Auckland, London, Manila, Paris, Rome, Seoul, Sydney, Tokyo.

- Jafari, 2000 J. Jafari Encyclopaedia of Tourism. Routledge, London (2000)

- Hrvatska enciklopedija, 2001 Kovačec, A. (Ed.), 2001–2006. Hrvatska enciklopedija. Leksikografski Zavod Miroslav Krleža, Zagreb.

- Popis stanovništva, kućanstava i stanova u 2011. godini, 2011 Popis stanovništva, kućanstava i stanova, 2011, Popis stanovništva, kućanstava i stanova u 2011. godini, 2011 Kontingenti stanovništva po gradovima/općinama <http://www.dzs.hr/Hrv/censuses/census2011/results/htm/H01_01_03/h01_01_03_zup19.html> (accessed on 14th April 2013).

- Filippi, 1995 Filippi, Ž., 1995. Marko Polo u književnim djelima. <http://www.korcula.net/mpolo/filippi_mpolo_lit.htm> (accessed on 15th June 2011.

- Filippi, 2000 Filippi, Ž., 2000. Marko Polo i Korčula u novijim domaćim i stranim časopisima. <http://www.ikorcula.net/marcopolo/Zivan_filippi_Casopisi.htm> (accessed on 3rd July 2011)

- Stella, 2011 Stella, G.A., 2011. Ecco Marko Polo, esploratore croato.

- Se Zagabria, 2011 Se Zagabria ci scippa l’eroe del Milione’, Corriere della Serra, 22nd April 2011. <http://www.corriere.it/esteri/11_aprile_22/per-conquistare-la-cina-marco-polo-diventa-croato-gian-antonio-stella_4857d1de-6ca2-11e0-902f-2f9ba9bc9f1b.shtml> (accessed on 5th June 2011).

- Bešker, 2011 Bešker, I., 2011. Talijani bijesni: Mesiću, Marco Polo je naš! Jutarnji list, 23rd April 2011. <http://www.jutarnji.hr/template/article/article-print.jsp?id=940970> (accessed on 5th June 2011).

- Scotti, 2011 Scotti, G., 2011. E dopo le ameba vennero i Croati. Marko Polić-Pol. La Voce del Popolo. <http://www.edit.hr/lavoce/2011/110429/politica.htm> (accessed on 5th June 2011).

- “Marco Polo”, 2011 “Marco Polo”. Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Online, Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., 2011. 20. May 2011. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/468139/Marco-Polo> (accessed on 15th June 2011).

- “Korčula”, 2011 “Korčula”. Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica Online, Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., 2011. 20 May 2010. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/322146/Korcula> (accessed on 15th June 2011).

Further reading

- http://www.korcula.net/mpolo/mpolocentre.htm, 2011a http://www.korcula.net/mpolo/mpolocentre.htm (accessed on 18th June 2011).

- http://www.korculainfo.com/marcopolo/ http://www.korculainfo.com/marcopolo/ (accessed on 15th June 2011).

- http://www.markopolosport.net/, 2011c http://www.markopolosport.net/ (accessed on 18th June 2011).

- http://hr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Picokijada_-_Legenda_o_picokima, 2011 http://hr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Picokijada_-_Legenda_o_picokima (accessed on 25th July 2011).

- http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/map/profile/croatia.pdf, 0000 http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/map/profile/croatia.pdf.

- http://korcula.net/naselja/kormap3.gif, 0000 http://korcula.net/naselja/kormap3.gif.