Merlionicity: The twenty first century elaboration of a Singaporean symbol

Southern Cross University, Lismore, Australia phayward2010@gmail.com

Abstract

Designed in 1964 as a symbol for the (then) fledgling Singaporean tourism industry that reflected Singapore’s maritime heritage, the Merlion – a figure comprising a lower half fish and upper half lion – has become a widely recognized icon of the modern island-state. But despite its prominence in representations of Singapore, the figure has divided opinion and generated debate amongst Singaporeans. Since the 1980s and increasingly in the 1990s and 2000s, artists, writers and critics have variously re-imagined and modified the Merlion in order to comment on aspects of Singapore’s national project. Prompted by the re-imagination of the Merlion at Singapore’s third Biennale of Arts (2011), this article develops comparisons to similar international symbols and analyses the role and historical trajectory of the Merlion in Singaporean society and the manner in which it has stimulated discussion of the island-state’s identity.

Keywords

Singapore, Merlion, Biennales, Symbolism, Tourism, Spectacularity

Introduction

The nature of symbols and of symbolism has attracted the attention of semioticians since the earliest days of the field. At a general level, symbols are signs that signify objects, entities or qualities to individuals and communities. Peirce (1867/1998) famously identified three types of signs and asserted that that they represent their designata (i.e. that which they designate) through ‘iconicity’ (the resemblance of the sign to aspects of its designatum), through ‘indexicality’ (a direct informational relation to the designatum) and through ‘symbolism’ (a conceptual evocation with no necessarily logical relation between the symbol and its designatum). In an influential study, Morris (1938) asserted that symbols operate within the social sphere through three different types of relationships: to persons, to objects and to other symbols. The stability of these relationships varies dependent on the nature of the symbol and on the nature (and complexity) of the designatum. A √ for example, operates relatively simply, unambiguously signifying a positive response. However, in the case of more complex designata, such as a social group, the relationship between symbols of that population and the population itself is more complex and liable to contestation or disassociation. In established territorial entities, such as cities or states, official civic symbols generally connect with the public on a spectrum ranging from passive disinterest and tolerance through to enthusiastic engagement. In more recently established and/or reconfigured territorial entities that do not have access to obvious heritage symbols, the creation, promotion and promulgation of new symbols is a more problematic project. Moghaddam et al. (2000) proposed the concept of ‘symbolic carriers’ to refer to symbols (such as flags) that represent particular communities and their values. However ancient or timeless they may appear, such symbols have life-spans that include moments of inception, phases of promotion and promulgation and periods of prominence, decline, disavowal and/or obscurity. While not primarily semiotic in orientation – being more concerned with issues of interpretation and critique and the role of artists and writers in pursuing these – this article recognizes the operation of symbols within the frameworks outlined above.

This article specifically addresses the creation of the Merlion as a national symbol for Singapore, initially as a logo for the state’s tourism development authority and then promulgated to be a ‘symbolic carrier’ for the state and its population more generally. In this regard it explores similar ground to Yeoh and Chang’s seminal study of the Merlion’s inception and late twentieth century development and reiterates their central research question in a more contemporary context:

If both tourism and nationalism are strongly productive of iconographic and monumental forms, what then happens when these forces converge and collide? Can a single iconographic form represent the coalescence of both forces and, Janus-faced, become both a recognizable emblem of the nation to the rest of the world and at the same time gain entry and root into the collective psyche of the nation? (2004: p. 31).

As a symbol developed in the earliest phase of Singaporean nation building, the Merlion has accompanied and participated in Singapore’s rapid socio-economic rise and played a prominent role in the development of the state’s spectacular ‘cityscape’ – an urban arena that (it will be argued) reflects the ideology and ambition of Singapore’s dominant People’s Action Party (PAP). The element of spectacularity in Singapore’s civic spaces (and public culture more broadly) is explored in this article with reference to concepts originated by Situationist theorists in the 1950s–60s. The deployment and discussion of these extends and reflects upon a number of Singaporean engagements with Situationist theory over the past decade. The most relevant reference in this case is Debord’s (1967: p. 1) epigrammatic pronouncement that:

The entire life of societies in which modern conditions of production prevail announces itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.

Aside from the sweeping nature of Debord’s (1967) central claim, acceptance of this characterization poses a number of questions about the nature of art (conceived as an incisive form that can illuminate and/or critique aspects of hegemony). As Home (1991: p. 42) concisely summarizes, the Situationists engaged with the concept of art and its effectiveness in a somewhat convoluted manner, rejecting established ‘bourgeois’ art as subsumed within the hegemonic operation of spectacle, calling for ‘real’ art to erupt out of its niches in order to assert itself in new forms that could escape this subsumption. Drawing on the semiotic concepts outlined above, this article analyses recent variants of and cultural engagements with the Merlion with regard to what a number of Singaporean writers have characterized as the spectacularization of Singaporean civic spaces. With particular regard to artistic engagements – and principally those associated with the state’s national Biennales (2006, 2008 and 2011) – the article addresses the extent to which successive creative engagements with the Merlion have modified its symbolic carriage.

Singapore: Tourism development and the Merlion

While the island has had a long history of habitation, Singapore became a fully independent state in 1965. Unlike the colonies that aggregated to form the Malaysian federation, Singapore was established as an ethnically and religiously diverse state, with the majority population (around 75%) being Chinese, with Malay and Indian populations comprising the majority of the remainder and with English as the state’s official language. Since independence, Singapore has been politically dominated by the PAP, which has promoted multiculturalism and religious tolerance as core values (along with a vigorous engagement with international capital). Tourism was identified as a prime area for economic development in the early 1960s, with government formulating the 1963 Tourism Act and establishing the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (now known as the Singapore Tourism Board or STB) in the following year (at a time when tourism to the city was minimal, with visitors numbering less than 10,000 per year). The Act formally gazetted a logo for the tourism board (Fig. 1) and restricted use of the symbol without official clearance.1

The central image of the logo featured a ‘Merlion’, a creature with a lion’s head and fish’s body and tail. This chimeric creature resembles various figures from Asian and European mythologies and more specific images developed within western heraldic practice.2 While the design of the figure is often attributed to Fraser Brunner, curator of the city’s Van Kleef Aquarium and a member of the tourism board’s Souvenir Committee, Lee (2004: p. 99) suggests a more complex and collaborative design process that reflected the strategic nature of the icon. Yeoh and Chan (2004: p. 32) identify the makara, a legendary figure from Malacaccan mythology – upper half elephant, lower half fish – as a model for the new city symbol. The design of a new logo/figure to promote Singapore reflects the manner in which the new island state had no established symbols that could be readily deployed by state agencies.

During the 1960s the Merlion principally existed as an organizational logo, reproduced in stationery, brochures and press advertisements that had little prominence within Singaporean society. This situation changed significantly in the 1970s when the Merlion was materialized in public statuary in a small waterfront park adjacent to the historic Fullerton Hotel. The 8.5 m high fountain statue (Fig. 2) designed by Singaporean artist Kwan Sai Kheong and realized by Singaporean sculptor Lim Nang Seng was officially opened by Prime Minister Lee Kwan Yew in September 1972. While this might be seen as the monumental inscription of a ‘symbolic carrier’ of Singaporean tourism within the cityscape, its manifestation as a thing-in-itself in the cityscape (i.e. as an artifact not functionally tied to the tourist board in the same manner as a logo on a tourism brochure) enabled it to become understood – however partially and problematically – by Singaporeans more generally.

As part of the promotion of the Merlion to Singaporeans and tourists alike, a formal account of the origins of the figure was devised and promulgated by the tourism board that continues to be reiterated as an explanation of the figure’s origins:

The choice of the Merlion as a symbol for Singapore has its roots in history. The Merlion commemorates the ancient name and the legend taken from the ‘Malay Annals’ (literary and historical work from the 15th or 16th century) explaining how Singapore received its present name. In ancient times, Singapore was known as Temasek which is Javanese for the sea. It was then, as it is today, a centre of trade. At the end of the 4th century A.D, Temasek was destroyed by the Siamese, according to some historians, but by the Javanese according to others. As recorded in the legend in the ‘Malay Annals,’ Prince Nila Utama of the Sri Vijaya empire rediscovered the island later in the 11th century A.D. On seeing a strange beast (which he later learnt was a lion) upon his landing he named the island Singapura which is a Sanskrit word for Lion (Singa) City (Pura). The Merlion, with its fish-like body riding the waves of the sea, is symbolic of the ancient city of Temasek. At the same time, its majestic head recalls the legend of the discovery of Singapore by Prince Nila Utama in the 11th century, when Singapore received its present name. (Singapore Tourism Board (nd): online).

This careful attempt to give the Merlion local historical legitimacy and credibility evidences an attempt to inspire respect and acceptance for it, despite the minimal knowledge of or interest in the figure prior to the erection of the statue and the subsequent representations and discussions of its significance.

The Merlion and Singaporean cultural identity

Carriers of all types serve to support particular styles of conduct, to confirm particular attitudes and to express particular relations […]. The point to be emphasized is the subtle power of the pantemporal symbol to carry a heavy cognitive load. (Moghaddam et al., 2000: p. 280).

The attempt to establish traditional Asian credentials for the Merlion symbol detailed above was complemented and extended seven years after the statue’s unveiling by a literary work, written by prominent Singaporean writer and English Literature academic Edwin Thumboo, that associated the Merlion with western mythologies. While the Merlion and its ‘legend’ had been created at a historical moment when Singapore was casting off the shackles of British colonial rule and emphasizing its ‘legitimacy’ in the region, squeezed between the far larger political entities of the Malaysian federation and Indonesia, Thumboo’s well-known poem ‘Ulysses by the Merlion’ was written in 1979, when the city-state was embracing its official English language and the literary traditions developed within it as part of its drive to internationalization. Thumboo’s poem specifically associates Homer’s Odyssey with the Merlion, and concludes with an explanation for the Merlion’s invention in terms of the modern city’s ‘yearning’ for a new image:

They hold the bright, the beautiful

Good ancestral dreams

Within new visions

So shining, urgent

Full of what is now.

A similar vision of Singapore’s potential to draw on residual local culture to form symbols and stories appropriate to a metropolitan present was offered in a subsequent – and very different – literary text, Gwee Li Sui’s graphic novel Myth of the Stone (1993), which opens with caption boxes that proclaim:

Urban worlds, they say, need new myths. If we will hear, the songs that once resounded in leas and tall trees have never truly faded. In that park of tall buildings, in that plantation of green, a quiet soul may still catch the joy of some wondrous thing left pure and free […]. And this is where we may best begin our story, not in some far-off place, but in the compass of a city we can all identify with, in the moments of the child we once were. (1993: p. 1).

In Sui’s (1993) novel, the Merlions feature as one of a number of magical creatures that a child encounters as the mythological past interweaves with the futuristic city-state. In this context the Merlions are sober and wise and on the side of peace and harmony.

The final lines of Thumboo’s (1979) poem – and, albeit more obliquely, Sui’s (1993) novel – reproduce the rhetoric of what has come to be known as ‘The Singapore Story’, i.e. the PAP’s official vision of Singapore developing and flourishing due to its respectful roots in custom and history combined with ‘shining’ ‘new visions’ and an ‘urgent’ pursuit of growth, prosperity and national pride. Tan (2011: p. 74) has described the story as ‘the authoritarian state’s hegemonic exercise of constructing an official history to contextualise its own lead role in Singapore’s survival and success’ and has identified that the state’s role as ‘heroic protagonist’ in the story bears an ‘uncanny resemblance’ to another classic Greek myth that of Narcissus, the self-absorbed, beautiful boy who fell in love with his own reflection and ‘eventually drowned in a moment of complete self-absorption’ (Tan, 2011). Tan goes on to assert:

The Singapore Story presents a postcard-perfect vision of a successful global city with a glistening skyline of ultra-modern international-style architecture, riverfront developments, and monumental temples of cosmopolitan consumerism. Like the water’s surface that presents to Narcissus his pleasing reflection, The Singapore Story serves as a mirror to show spectacular images of the world-class city as a reflection of the PAP government’s heroically proportioned self. (2011: p. 75).

Tan’s (2011) description of state narcissism and its watery reflection are particularly relevant for the first prominent Singaporean critique of the Merlion and the relationship between the design of the symbol and the significance claimed for it by its proponents. Coincidentally or not, this appeared shortly after the tourism board dropped the Merlion as its corporate logo, allowing the symbol a less deterministic carriage.3 Alfian Bin Sa’at’s ‘The Merlion’ (1998) (often understood as a direct riposte to Thumboo’s (1979) verse) offers its critique through the comments of a companion accompanying the poem’s protagonist on a visit to the statue (combined with the poet-protagonist’s reflections on these). The companion’s critique is frank, graphic and iconoclastic:

‘I wish it had paws,’ […]. ‘It’s quite grotesque the way it is, you know, limbless; can you imagine it writhing in the water, like some post-Chernobyl nightmare?’.

Moving from this consideration of its awkward physicality, the poem considers the Merlion’s situation, ‘marooned’ onshore and inserted into a built city environment, constantly emitting water from its mouth:

[…] look at how it tries to purge itself of its aquatic ancestry, in this ceaseless torrent of denial, draining the body of rivers of histories, lymphatic memories.

‘And why does it keep spewing that way? I mean, you know, I mean...’. ‘I know exactly what you mean,’ I said […].

It spews continually if only to ruffle its own reflection in the water; such reminders will only scare a creature so eager to reinvent itself.

The above verses offer an ironic commentary on Singapore as the ‘Narcisstic state’ proposed by Tan (2011) in that the Merlion (created by that same state) is depicted by Sa’at as a figure intent on not glimpsing its reflection in the water and, thereby, not recognizing its own ‘grotesque’ identity. In Sa’at’s (1998) poem the Merlion is characterized as continuously vomiting in a manner that serves to critique its coherence, let alone credibility, as a symbolic carrier. The markedly different positions adopted by Thumboo and Sa’at towards the statue, and the continued prominence of the Merlion in public culture in the 2000s, has made the topic particularly attractive for local writers, to the extent that the Singapore Public Art online database (2009) has characterized that ‘writing a Merlion poem is a rite-of-passage for Singapore’s younger poets’ (2009).4

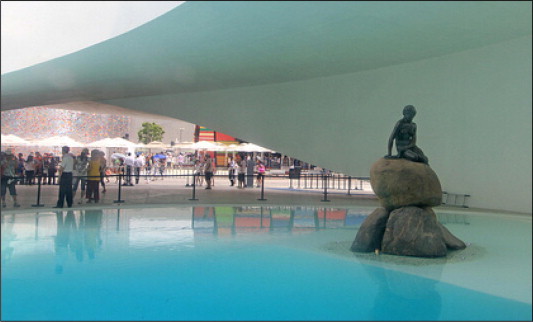

The Merlion’s prominence as a public icon was further boosted by the statue’s relocation to an area of reclaimed land within a dedicated park space overlooking the river in 2002 (Fig. 2) following the construction of the Esplanade Bridge (which blocked views of the Merlion from the river). The move was successful in that the newly created Merlion Park has become a major tourist attraction in its own right (see Goh and Yeoh, 2004). Along with the fountain statue in Merlion Park, the other most spectacular inscription of the Merlion into the tourist fabric of Singapore occurs on Sentosa Island in the form of the Merlion Tower (Fig. 3). The impetus behind the construction of the tower was the desire to create a prominent feature on the city’s skyline, with Marina Bay initially being considered as its erection site. This plan met with mixed responses. Pamelia Lee (head of the tourism board’s Marketing Division from 1978–84 and subsequently a consultant for various tourism bodies), for instance, resisted the scale of the proposed figure, perceiving it as unnecessary, and compared the original Merlion figure to successful counterparts in Europe, arguing that, ‘the Little Mermaid in Copenhagen and the Mannikin Pis in Brussels5 are both famous, yet they are very small’ (2004: p. 102). Despite such discussions of scale, opposition to the proposal for a monumental tower subsided when a less central location was identified in the form of Sentosa Island.

The Merlion Tower on Sentosa (Fig. 3) was designed by Australian sculptor James Martin and was completed in 1995. It stands 37 m high and has an inbuilt network of lights that illuminate the building at night and an apparatus that projects laser beams from the creature’s eyes. In addition to its external monumentality, the Merlion Tower houses an arcade that cross-associates the Merlion figure with a range of aquatic mythologies and a mini-theatre that continually re-screens a short film produced by the US company ACME Filmworks. The film comprises hand-drawn animation with accompanying orchestral music (blending western instrumentation and ‘Asianist’ musical motifs) and narration, relaying the STB’s standard mythical account of the history of Singapore and the Merlion in a cheerful and accessible manner (Fig. 4). Collectively, these – and similar – representations and engagements with the Merlion create a circling system of signs about signs that recall Choy’s description of the city-state in terms of classic Situationist discourse as ‘Sign-apore, a society of the spectacle par excellence’ (2005: 244 – emphasis in original).

The Merlion, Biennales and spectacularity

The first Singapore Biennale was held in 2006 in the same year as two other major events that attracted international attention to the city: meetings of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. The concept of a biannual art event held in (and associated with the promotion of) a particular city originated with the Venice Biennale, first held in 1895. After World War Two the Venice event particularly focused on promoting avant-gardism and, through the contributions of architect Carlo Scarpa in the 1950s and 1960s, the ambitious use of exhibition spaces (see Alloway, 1969). Both of these aspects were influential on the development of subsequent Biennales, which are now held regularly in cities across the globe. These have developed as major international events that attract artists, critics and tourists to their locations, thereby accruing both cultural and economic capital for the state, regional and/or city authorities that support them. While there has been a substantial degree of homogeneity to many of these, resulting from competition to attract prestigious international artists and access a cultural tourist market faced with increasing choices, there is still an important local aspect and significance to such events, particularly in countries in which sociocultural expression has been constrained by various forms of state authoritarianism. As Schneider (2009: p. 1) noted in a perceptive study of the development of Chinese and South Korean Biennales, ‘vast differences exist between these large-scale exhibitions, in terms of presentation, argumentative production of meaning represented through the art works, conceptual framework and their embedding in the histories of nation state and specific local conditions’. She notes a dual orientation and impetus for Biennales in such locations:

[…] firstly, the examination and definition of a contemporary identity, using forms of celebration, encounter, historicization, theorization and global contextualization; secondly, the strengthening of global visibility in order to position cities […] as cultural hubs, thereby attracting visitors, gaining prestige and contributing to the production of cultural values and knowledge. (Schneider, 2009).

Tang’s (2007) analysis of Singapore’s first Biennale (Singapore Biennale 2006) sought to address both these aspects with reference to notions of the spectacle developed by Debord. Tang’s work represents one of the first Singaporean articles to engage with Debord’s concept in a manner that goes beyond the bland characterization of contemporary Singapore as exemplifying the ‘society of the spectacle’ that Debord first identified as characterizing western society in the 1960s. Tang draws on Debord in order to comprehend the rhetoric behind and national support for the first Biennale and to offer a more critical interrogation of its content and local importance. More precisely, she orientates her analysis to a discussion of the manner in which the first Singapore Biennale was a ‘spectacularized’ event organized by a city-state that was increasingly concerned with its own spectacularization:

Debord’s integrated spectacle illuminates Singapore’s materialization in terms of the total abstraction of commodity value, and the appropriation of social activity so that reality is constituted as image since ‘spectacular’ government possesses the means to falsify both production and presentation. Such images, production and presentation reflect a targeted optimism. (Tang, 2007: p. 367).

Within this context she emphasizes that:

The notion of a spectacularized event is distinct from the Debordian integrated spectacle of the everyday, as the latter is both concentrated and diffuse, penetrating all reality […] However, in Singapore’s case, the spectacularization of the Biennale was allied to the integrated spectacle of the tropical island-state. (Tang, 2007: p. ibid)

Attending to the ideological purpose behind the Singapore Government’s support for the Biennale (and the Arts in general) Tang identifies that: ‘In the golden cage of capital where the economy triumphs, art is shoe-horned into performing an aestheticizing function for the state’ (2007).

Her point is not so much that the aesthetic project of art is drained or effaced in such a context but rather that it is cramped and constrained by the institutional ideologies, modes and mechanisms of the state and that its significance is in the way it can exploit faultlines and/or ambiguities within this. There is much in this formulation that applies to the function of art within totalitarian states in general but what marks Singapore’s particular nature is, for her, the deployment of ‘the sentimental register of Singapore’s spectacularization’, which she perceives ‘as clearly meant to invoke the state’s emotive, soft and fuzzy side’ (Tang, 2007).

Of the works discussed in her analysis, one of particular relevance to this article was the contribution of Swiss duo Com&Com (Marcus Gossolt and Johannes Hedinger). Given the careful management of the Merlion logo inscribed within the tourist board’s 1963 enabling Tourism Act (see endnote 1), Com&Com’s use of the image was acceptable to the state by virtue of its deployment within a specific aesthetic framework that appeared relatively innocuous and by virtue of the duo transforming the static Merlion symbol to a more mobile variant, named ‘Mermer’. Founded in 1997, Com&Com have described their early work as: ‘multimedia parodies that ironically deconstruct concepts such as homeland and myth’ within ‘complex communication projects that use targeted participation, provocation, and attention-getting strategies that extend beyond the artistic context to engage society as a whole in a dialog’ (Com&Com, 2011: p. 3).

The particular project that brought Com&Com to the attention of the first Biennale curators occurred in the Swiss town of Romanshorn in 2003 when the duo won a commission to create a public sculpture that could provide the town with an identity symbol. Influenced by Japanese manga and popular culture in general, the duo devised the Mocmoc, an anthropomorphized fish with a unicorn’s horn, and monumentalized it as a 6 m high statue. In a process with distinct parallels to the STB’s invention and dissemination of the Merlion, the ‘kitschy’ and invented nature of the icon generated considerable debate in Romanshorn and in Switzerland more generally. This led to a town referendum on its use that was won by its supporters, with the image now widely used in tourism promotion and related artefacts. Indeed, the Mocmoc has served as what might be termed an ‘ambassadorial mascot’ for the town and a costumed Mocmoc figure (which invites comparison to the ‘walking animations’ that greet visitors to Disneyland) has made official appearances at events such as the 7th Sharjah International Biennale. As a result of their success, Com&Com were invited to produce a work for the 2006 Singapore Biennale. Reinforcing the similarity between their invented entity and the STB’s icon, they animated the Merlion as a figure referred to as ‘Mermer’ and produced a two-part video program production entitled Mocmoc & Mermer The incredible adventures of two friends (Fig. 5). The program represents the figures as decidedly human in aspect, prone to enthusiasm, bickering, reconciliation and – in the penultimate scenes – partying; interacting in Switzerland and Singapore in a seemingly naïve manner that recalls both mainstream children’s TV series (such as The Teletubbies) and more archly ambiguous productions (such as PeeWee’s Playhouse). The pair’s interaction is given a disingenuously philosophical rationale in the duo’s program notes:

The two friends eagerly make their way through the world, observing and trying to understand it. What helps us to see history? What brings us the future? […] Mocmoc and Mermer are constantly searching for the meaning of life and the answers to the questions: Who are we? Where do we come from and where are we going? (2006 – in 2010: online)

In addition to producing the video and a dedicated website (http://www.mocmocmermer.com), the duo also ran workshops in Singaporean schools in which they invited students to represent the figures in contexts familiar to them. The duo’s work with Mermer involved stimulating discussion about the use of an ‘invented’ public symbol through reformulation of its prefabricated aesthetic elements and their symbolic associations. Like their original design and promotion of Mocmoc, this involved the collapsing of the distance between officially sanctioned heritage symbols and popular cultural icons and of the different registers of respect and reverence usually accorded to the former and the less profound (though often no less intense) identification accorded to the latter. In the case of Switzerland, a state with a substantial history of regional identities and a federation dating back to 1848, the collapsing of this distance was arguably more significant than in the case of the duo’s interpretation of Singapore’s Merlion in their Mermer character. Indeed, Tang has characterized Com&Com’s contribution as part of the ‘hefty dose of crowd-pleasing pop’ that dominated the Biennale, marked by a ‘campy humour’ that targeted ‘the viewing body’s situation within a spectacularized event’ (2007: p. 370). But while Mermer may have represented a variant of a figure whose status as a symbolic carrier is still in flux, it offered a type of interpretation that had not previously been attempted by Singaporean artists and preceded the engagements with the Merlion at the third Biennale (Singapore Biennale 2011) discussed below.

Détournement and state sanctioned recontextualization

Our past is full of becoming. One needs only to crack open the shells. Détournement is a game born out of the capacity for devalorization. Only he who is able to devalorize can create new values. And only there where there is something to devalorize, that is, an already established value, can one engage in devalorization. It is up to us to devalorize or to be devalorized according to our ability to reinvest in our own culture. (Jorn, 1959: online)

These comments by Danish artist Asgar Jorn, a high profile member of the European Situationist movement, refer to the broad strategy of devalorization and reappraisal central to détournement, a practice that involved the modification of previously produced cultural artefacts in order to ‘hijack’ their potential meanings. ‘Law’ 2 of the (Situationists’ so-called) Bureau of Public Secrets’ User’s Guide to Détournement specified that:

The distortions introduced in the détourned elements must be as simplified as possible, since the main impact of a détournement is directly related to the conscious or semiconscious recollection of the original contexts of the elements. (Debord and Wolman, 1956)

With regard to the latter prescription, one well-known example of this approach occurred in Copenhagen on 24 April 1964 when Jörgen Nash, a member of the Danish Bauhaus Situationiste group decapitated Edvard Eriksen’s bronze statue of the Little Mermaid,6 commemorating the protagonist of Hans Christian Andersen’s eponymous short story (1836). The statue was commissioned by Carl Jacobsen, owner of the Carlsberg brewing company, in 1909 after he attended a ballet adaptation of the story at the city’s Royal Theatre. Installed on a rock on the foreshore of Copenhagen Harbour in 1913, the statue first became a popular tourist site and, subsequently, a de facto symbol of the city. Nash’s act, and the subsequent provocative poem and ‘misinformational’ articles he wrote about the event, generated a major international media story that – unintentionally – provided highly effective publicity for both the statue (which was subsequently restored) and Copenhagen. Despite a number of subsequent attacks, the 1.25 m statue remains one of Copenhagen’s iconic tourist sites, attracting around 1.5 million visitors a year (Aeppel, 2009), and is present in a range of promotional material for the city. Like Singapore’s Merlion it has been copyrighted and the Eriiksen family has carefully controlled its reproduction.

While much of the Situationists’ early applications of détournement centered on posters and written texts of various kinds, Debord and Wolman’s seminal 1956 User’s Guide to Détournement also contained some speculation on the potential for public architecture and urban spaces to be manipulated:

The architectural complex – which we conceive as the construction of a dynamic environment related to styles of behavior – will probably détourn existing architectural forms, and in any case will make plastic and emotional use of all sorts of detourned objects […] It is said that in his old age D’Annunzio, that pro-fascist swine,7 had the prow of a torpedo boat in his park. Leaving aside his patriotic motives, the idea of such a monument is not without a certain charm […] If détournement were extended to urbanistic realizations, not many people would remain unaffected by an exact reconstruction in one city of an entire neighborhood of another. Life can never be too disorienting: détournement on this level would really spice it up. (Debord and Wolman, 1956)

While the Situationists never expanded their critique/attack on Copenhagen’s seminal mermaid icon into an architectural/spatial détournement of the kind mooted above, a related enterprise was developed by a very different organization 46 years later. Illustrating capitalism’s endless power to assimilate radical gestures, this was facilitated by BIG – The Bjarke Ingels Group – a company employing over 90 architects, builders and theoreticians dedicated to the pursuit of ‘pragmatic utopian architecture’, much of which re-interprets, recontextualizes and ‘revalorizes’ established urban spaces (such as Copehagen’s Battery area) as major commissions supported by metropolitan and state bodies. Ingels explains his approach in the following terms:

Historically the field of architecture has been dominated by two opposing extremes. On one side an avant-garde full of crazy ideas. Originating from philosophy, mysticism or a fascination of the formal potential of computer visualizations they are often so detached from reality that they fail to become something other than eccentric curiosities. On the other side there are well organized corporate consultants that build predictable and boring boxes of high standard. Architecture seems to be entrenched in two equally unfertile fronts: either naively utopian or petrifyingly pragmatic. We believe that there is a third way wedged in the nomansland between the diametrical opposites. Or in the small but very fertile overlap between the two. A pragmatic utopian architecture that takes on the creation of socially, economically and environmentally perfect places as a practical objective. (BIG, 2011: online).

Echoing Debord and Wolman’s (1956) call for détourned ‘urbanistic realizations’, Ingels made a proposal to Copenhagen City to relocate the Little Mermaid statue to the Danish Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai Expo. This proposal met with sustained public protests, including opposition from the right wing Danish People’s Party, who went so far as to propose a new national law to prohibit the statue’s relocation. Despite this response, the City Council supported the proposal and the statue was carefully relocated to China and installed at the Expo in an area constructed to resemble Copenhagen Harbour (Fig. 6). For the duration of the Expo visitors to (the actual) Copenhagen Harbour were presented with a radically different experience of the Little Mermaid statue in the form of a large video screen showing the image of the statue in its Shanghai installation (produced by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei). As Ingels explained it:

The purpose of moving The Little Mermaid is to show that open-mindedness doesn’t necessarily cause you to lose origin or culture […] Typically, national symbols are static – a fortress or a tower, which is unshakable. The perception of a nation with a national symbol so dynamic that it can be moved to China for six months is a great way of showing that Denmark is open-minded and liberal towards the rest of the world. (Ginsberg, 2010).

BIG’s identification of the Little Mermaid as a ‘national symbol’ is notable in that while it is not officially recognized as such and is neither present in the national coat of arms (which shows three lions) nor the national flag (simple white cross on red background) it has, like the Merlion, become a well-recognized national symbol as a result of its prominence in tourism.

As explicitly acknowledged above, BIG’s relocation and recontextualization of the Little Mermaid represented less a détournement of the statue-symbol’s prefabricated aesthetic elements and more what the first edition of the Situationiste International described as its opposite: a pseudo-détournement originated ‘from within old cultural spheres’ as ‘a form of propaganda’ for hegemonic purposes (unattributed, 1958). As such, BIG’s installation conformed to the overall function of the Shanghai Expo, as an event unproblematically dedicated to the promotion of a city and nation states. In the case of Biennales, such as those discussed below, the function of the events is somewhat more complex and has the capacity to support less overtly ‘propagandist’ contributions.

While there appears to have been no causal relationship between the two projects, the idea of physically relocating a monumental icon to another continent for a major international event was proposed in Singapore five years prior to the Little Mermaid’s appearance in China. In 2005 Lim Tzay Chuen, the artist chosen to represent Singapore in the 2005 Venice Biennale, proposed shipping the (substantially larger) Merlion statue to Venice as part of an installation representing contemporary Singapore. While the proposal was given serious consideration by the STB, logistical difficulties and the possibility of damage militated against the proposal.

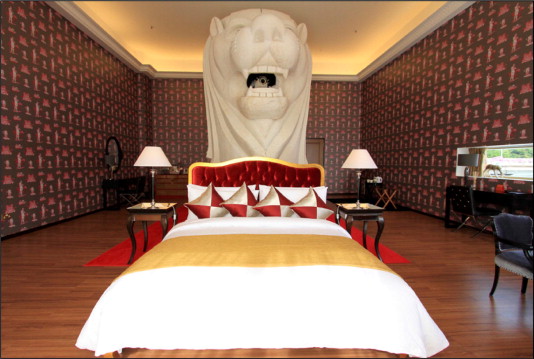

A less risky proposal to recontextualize the Merlion in situ was, however, accepted by the STB for Singapore’s third Biennale (Singapore Biennale 2011).8 The proposal was made by Japanese artist Tatzu Nishi and involved building a (fully functional) hotel room around the main Merlion statue at Merlion Park for the duration of the Biennale (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8). As Biennale curator Matthew Ngui has outlined:

The artwork is essentially a conceptual one, dealing with the alteration of the distance between the sculpture and the public member or visitor and how that affects perception. So in order to gain permission, we had to put across the value of the project in terms of giving a different perspective on the Merlion and appreciating it more up close. The Singapore Tourism Board, the owner of the Merlion, bought into this and were encouraging in their support for the project. The issues of damage would always be there, even if there wasn’t a hotel room around it so the concerns centred more around cutting off the view of the Merlion from the outside and how tourists would take this.9 (p.c. June 2011)

Accompanying the looming presence of the Merlion in the room, the walls were lined with wallpaper designed by the artist that combine two of the most prominent symbols of the island state, the Merlion itself and statuary that celebrate British imperial visionary Sir Stamford Raffles.

The installation’s function as an actual hotel room, available for booking by guests, also raises questions about the experience of an interior space so prominently occupied by a ‘symbolic carrier’ of Singaporean statehood, overshadowing the dreams of those who sleep with it over their bed-head (and overlooking any sexual congresses that may occur in the temporary space).10 Similarly to BIG’s Little Mermaid installation at the 2010 Shanghai Expo, the Merlion Hotel installation is less a détournement of the ‘prefabricated aesthetic elements’ of its referent as an artful celebration that can be seen as propagandist in that it simultaneously acted as a tourism attractor, reaffirmed the liberalism of the Singaporean state (by allowing the temporary modification of an iconic public monument) and further embellished the spectacularity of its cityscape.

Chuen’s installation was successful on a number of levels. Internationally, it proved popular with media outlets that used it as a pretext for enthusiastic travel features on the city, re-inscribing the Merlion as ‘the’ iconic symbol of Singaporean tourism (see for example, Barrett, 2011). In Singapore itself the installation received mainly positive reviews from bloggers and journalists, many of whom understood the public art context and function of the work. En (2011) for example, commented that the ‘Merlion hotel strikes all the right notes in a public art installation: it’s interactive, tongue-in-cheek and nudges our country to poke a little healthy fun at ourselves’. Providing a more sustained analysis, Jusdeananas (2011) asked:

Is it Art? Commerce? An ‘uncanny encounter with a public monument in the intimacy of a hotel room’? A re-imagining of the connections between citizen and symbol? A grandiose declaration of Swingin’ Singapore’s new-found fame as a playground for the rich and ritzy? All of the above? None of the above? Who knows? Which is why I love it. A stroke of genius on Nishi’s part [...] at its most immediate and intelligible, the Merlion Hotel probably serves best as a symptom of the new Singapore. And just what is this new Singapore? Flush (the world’s fastest growing economy as of 2010), fancy (now boasting two fabulously glitzy resorts with the country’s first casinos), and demographically and sociologically evolving at light speed, the population on the whole growing from some 3 million to 5 in the last two decades […] with the number of resident aliens positively ballooning from 0.3 million in 1990 to 1.3 million in 2010. (2011: online)

These characterizations are accurate. Over the last decade in particular, Singapore has increasingly become a city with a marked gap between rich and poor, with researchers such as Dhamani (2008: p. 23) identifying that ‘the consequences of income inequality strongly suggests that rising income disparity could rob Singapore of the very factors – rule of law, order and efficiency – that enabled Singapore to become a vibrant financial hub and technology centre within four decades’. The internationalization of the city both reflects and reinforces this disparity and creates further cultural pressures in that in order to continue to attract tourists and to attract and retain ‘resident aliens’ the city needs to continue to develop a modern culture to rival competitor cities such as New York or Hong Kong. As Wee (2011) has identified, recalling Situationist critiques of the manner in which art has been subsumed into the spectacular manifestation of hegemony:

We live in what appears to be an unprecedented global moment in which the contemporary arts, new museums and biennales have been linked to a commodity reification and a near-frenzied consumerism […] Such developments have transformed the puritanical […] city-state from a purported ‘cultural desert’ into […] what exactly? A ‘Global City for the Arts’? An empty cultural hub where other people’s cultural products flow through, and ‘hip’ capitalism is celebrated? (2011: p. 146)

Rather than the city-state’s original vision of combining South East Asian and colonial-era European values and heritage – as manifest in Thumboo’s ‘Ulysses by the Merlion’ – the new, globalized environment calls for an international visual culture enacted in the public spaces of the city, in architectural features such as The Esplanade Theatres on The Bay and The Marina Bay Sands Towers, and in the playful engagements with national identity symbols that were presented in the cityscape during the 2011 Biennale (Fig. 9). In this way, the reverential cultural conservatism of the 1980s’ and 1990s’ Singapore has been replaced by a pragmatic corporatism that treats Singapore’s past with less reverence and more readily facilitates alternative imaginings of Singapore’s present and future whilst remaining committed to core ideological values.

Singapore futures

While Tatzu Nishi’s Merlion Hotel installation recontextualized the presence and experience of the Merlion in Merlion Park within an aestheticized extension of the ‘logic’ of tourism, Ryf Zaini’s Biennale work provided a very different image. Laying on its side in the grass outside the Singapore Museum of Art, Singaporean artist Zaini’s sculptural installation ‘Disarming the Lion’ (Fig. 10) is a post-Apocalyptic image most readily understandable in science fiction terms. It appears as an archaeological relic from the future, from a time when both the contemporary city-state and its future high-tech version have been superseded and/or destroyed by an unspecified catastrophe. In terms of recent science fiction imagery, the supine metallic Merlion’s flickering visual screens evoke images of the decaying Terminators of James Cameron’s eponymous films (1984, 1991, 2003), robotic life forms lingering on despite their incapacitation, with their eyes betraying the final flickerings of circuitry. In this regard, the work invites comparison to another ‘technologized’ cultural representation of the Merlion, DJ MA2HIKO’s dub-textured electronica track ‘Merlion is Dead’, which features skittering electronic bleeps over gradually accelerating rhythmic patterns that ultimately pare down to an electronic heartbeat that abruptly cuts out, concluding the track with its subject’s death.

The sign accompanying Zaini’s installation identifies the sculpture as referencing ‘the Singapore Merlion, which has been standing watch over Singapore these decades’ and goes on to elaborate that the LCD screens in the creature’s eyes ‘show flashbacks to what it has seen over the years’. Discarded and fragmented, the Merlion’s head recalls the scene from Matt Reeves’ 2008 film Cloverfield, where citizens fleeing the terror of an unknown alien monster devastating Manhattan are startled to see the head of the Statue of Liberty skidding along a street, tossed far from its base on Liberty Island, illustrating the impermanence of even the most celebrated symbols and statuary. While open to a variety of interpretations, the installation’s ‘edge’ is that it tacitly proposes an alternative future to the eternally ‘bigger-better-richer’ history apparently unfolding from Singapore’s economic boom and continuing spectacularization of the city. The symbol, lauded by former prime minister and political architect of late twentieth century Singapore Lee Kuan Yew at the official opening of its harbourside statue in 1972, is implicitly symbolic of a future in which Yew’s paternalistic blueprint for Singaporean governance no longer holds sway and the energies of the city-state find new channels and directions.

Conclusion

One of the fundamental differences between the Situationists’ notion of détournement and the recontextualization of monumental icons and iconic city spaces present in BIG’s Shanghai Expo installation and in the Merlion Hotel installation at the Singapore Biennale 2011 is the former group’s crucial identification of détournement as an intrinsically subversive act. Whatever Debord and Wolman’s (1956) sneaking regard for ‘proto-Fascist’ D’Annunzio’s submarine ‘folly’ in his garden, the radicals involved in the movement would likely not have recognized the aesthetics of the Shanghai and Singapore works as remotely akin to their concept. Indeed, if the Situationist had seen any such resemblance, it would likely have lead to the denunciation of the latter as superficial re-inscriptions of a modern capitalist sign system in the guise of avant-garde public art. Indeed this perspective has some credibility, as the Situationists were not concerned with the form of their ‘art’ but rather its purpose and impact. Neither BIG’s Shanghai Expo installation nor the Biennale’s Merlions (nor Com&Com’s earlier animation of ‘Mermer’) ‘subverted’ on anything but a ‘tolerable’ level. Rather, what they did is emphasize that the monumentality of cultures and their manifestations in particular locales are no longer as fixed as they once appeared. Their engagements put signs ‘into play’ and suggest a way past the ‘stagnancy’ that Lee (2004) identified in the Merlion in the early 2000s. With the possible exception of Zaini’s work, which can be interpreted to symbolize a futuristic, dystopian aftermath to Singapore’s post-economic boom; recent re-imaginations of the Merlion have operated within hegemonic parameters.

In terms of longevity, the fifty-year history of the Merlion pales in significance to the major time spans of national symbols drawn from European and Asian traditions. Yet, in the context of Singapore, which only began to coalesce into anything like its current form 200 years ago (and only achieved independence one year after the Merlion had been adopted by the tourist board), its development has been informed by and intertwines with shifts in cultural awareness and identity debates that can be seen to have established it as a significant expression of Singaporean identity through its very ‘manufactured-ness’. The extent to which this is simply another spectacular distraction to critics intent on achieving reforms in freedoms of expression and democratic participation is open to question, but the symbol’s endurance is testament to its currency as a contemporary heritage form.

Thanks to Rebecca Coyle and Rosa Coyle-Hayward for their field research assistance on this article.

Endnotes

- The Merlion Symbol is to be used in good taste.

- The Merlion Symbol is to be reproduced in full.

- Wordings, graphics or objects are not to block or be superimposed over the design of the Merlion Symbol […].

- in any trademark.

- as part of a logo e.g. in letterhead of the company.

- in association with or in promotion activities which are illegal or likely to debase The Merlion or embarrass the image of STB or Singapore. (STB, 2010)

References

- Aeppel, 2009 Aeppel, T., 2009. In a Mermaid Statue, Danes find something rotten in State of Michigan: small town’s ode to ethnic culture draws call from ’the art police’ over licensing. The Wall Street Journal, July 27. Available from: <http://www.webcitation.org/5iZbZU3o9> (accessed December 2011).

- Andersen, 1836 Andersen, H.C., 1836. The Little Mermaid. Published online at: <http://hca.gilead.org.il/li_merma.html>.

- Barrett, 2011 Barrett, F., 2011. Singapore finds its roar: it’s goodbye sober living and hello gambling, white-knuckle rides and endless partying. Mail on Sunday (UK), May 17. <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/travel/article-1387298/Singapore-City-celebrates-Singapore-Biennale-Merlion-Hotel-art-installation.html#ixzz1hldwOpJQ> (accessed December 2011).

- Beder, 1999 Beder, C., 1999. European times: Copenhagen – invitation to a beheading. The Independent, 15 January. Available from: <http://www.independent.co.uk/news/european-times-copenhagen--invitation-to-a-beheading-1073976.html> (accessed December 2011).

- BIG, 2011 BIG (2011). ‘Info’. <http://flash.big.dk/> (accessed March 2012).

- Com&Com, 2011 Com&Com, 2011. Work documentation 2003–2011. Available from: <http://www.com.ch> (accessed January 2012).

- Debord and Wolman, 1956 Debord, G., Wolman, G., 1956. Mode d’emploi du détournement. Les Livres Nues n8, translation by K. Knabb. Available at: <http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/detourn.htm>.

- Debord, 1967 Debord, G., 1967. La société du spectacle. English translation by Perlman, F. Supiak J. (1977). Available from: the Situationist International Text Library: <http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/pub_contents/4> (accessed November 2011).

- Dhamani, 2008 Dhamani, I., 2008. Economic inequality in Singapore: causes, consequences and policy options. National University of Singapore report.

- En, 2011 En, X.C., 2011. Fancy a stay at the Merlion Hotel? <http://www.augustman.com/2011/02/16/fancy-a-stay-at-the-merlion-hotel/> (accessed January 2012).

- Ginsberg, 2010 Ginsberg, E., 2010. The Mermaid War: how a proposed trip to China for Denmark’s cultural icon divided a nation. Available from: <http://journalism.nyu.edu/publishing/archives/livewire/global/little_mermaid/> (accessed November 2011).

- Home, 1991 S. Home The Assault on Culture: Utopian Currents from Lettrisme to Class War. AK Press, Stirling (1991)

- Jorn, 1959 Jorn, A., 1959. Détourned painting. Available from: <http://www.infopool.org.uk/5901.html> (accessed November 2011).

- Jusdeananas, 2011 Jusdeananas, 2011. The Longue Durée: [Singapore Biennale ’11] At the Merlion Hotel. Available from: <http://jusdeananas.wordpress.com/2011/03/31/singapore-biennale-11-at-the-merlion-hotel/> (accessed December 2011).

- Lee, 2004 P. Lee Singapore, Tourism and Me. Self-published, Singapore (2004)

- Moghaddam et al., 2000 F. Moghaddam, N. Slocum, N. Finkel, et al.Toward a cultural theory of duties. Culture and Psychology, 6 (3) (2000), pp. 275-302

- Morris, 1938 C.W. Morris Foundations of the Theory of Signs. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1938)

- Peirce, 1867/1998 C. Peirce On a new list of categories. C. Edward, E. Moore, M. Fisch, C. Kloesel (Eds.), Writings of Charles S. Peirce, vol. 2, University of Indiana Press, Bloomington (1867/1998), pp. 1867-1871

- Sa’at, 1998 A. Sa’at The Merlion. A. Sa’at (Ed.), One Fierce Hour, Landmark Books, Singapore (1998), pp. 21-22

- Schneider, 2009 Schneider, A., 2009. Architectures of spectacle: facets of the exhibition boom in South Korea and China in the context of the strategy of globalism. Available from: <http://www.springerin.at/dyn/heft_text.php?textid=2167&lang=en> (accessed January 2012).

- Singapore Public Art Online Database, 2009 Singapore Public Art Online Database, 2009. http://www.publicart.sg/?q=Merlion-and-PoetsSingapore Tourism Board website (nd): <https://app.stb.gov.sg/asp/form/form01.asp>.

- Sui, 1993 G.l. Sui Myth of the Stone. East Asia Book Services, Singapore (1993)

- Tan, 2011 K. Tan The narcissistic state and the Singapore story. W. Lim, S. Siddique, T.D. Feng (Eds.), Singapore shifting boundaries: social change in the early 21st century, Asian Urban Lab, New york (2011), pp. 73-83

- Tang, 2007 J. Tang Spectacle’s politics and the Singapore Biennale. Journal of Visual Culture, 6 (3) (2007), pp. 365-377

- Thumboo, 1979 E. Thumboo Ulysses by the Merlion. Heinemann Educational Books, Singapore (1979)

- Unattributed, 1958 Unattributed, 1958. Definitions (translated by A.H.S Boy). Internationale Situationiste, 1, <http://libcom.org/book/export/html/1843>.

- Wee, 2011 C.J.W.-L. Wee The increasing ‘relevance’ of the contemporary arts in Singapore. W. Lim, S. Siddique, T.D. Feng (Eds.), Singapore shifting boundaries: social change in the early 21st century, Asian Urban Lab, Singapore (2011), pp. 146-153

- Yeoh and Chang, 2004 B. Yeoh, T.C. Chang ‘The Rise of the Merlion’: monument and myth in the making of the Singapore story. R. Goh, B. Yeoh (Eds.), Theorizing the Southeast Asian City as Text: Urban Landscapes, Cultural Documents and Interpretative Experiences, World Scientific, Singapore (2004), pp. 29-50