Beyond the boundaries in the island of Ireland

Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK s.royle@qub.ac.uk

Abstract

The review essay opens with positive attributes of Ireland but then considers that the island has been subject to centuries of bitter dispute and unrest. The historical background to this is outlined, particularly the interactions between Ireland and its neighbouring island, Great Britain, which dominated Irish affairs. One policy adopted by the British was to encourage migration of Protestants into the largely Catholic island in the vain hope that this would reduce unrest. The two islands were then united from 1801 as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland but demands from indigenous Irish Catholics for independence continued, resisted by the Protestant minority who wished to remain inside the UK. After the Great War a solution was imposed that granted most of Ireland independence but left the largely Protestant northeast corner within the UK as Northern Ireland. Reaction to and life with the Irish border are considered and the paper concludes with musings about its future.

Keywords

Ireland, Northern Ireland, Borders, Divided islands

Introduction

Ireland, the world’s twentieth largest island at 84,421 sq km, is situated off the northwest edge of Europe. It is a land of great geological complexity with a considerable variety of environments, including some rich cultivated areas, but the damp, rather cool, climate restricts agricultural opportunities and the island is noted for livestock production and dairying rather than cereals. Famous products traded internationally include Irish whiskey (spelled with an ‘e’, unlike Scotch whisky) and stout, a dark beer manufactured by a number of companies including Guinness. People from Ireland have made a considerable contribution to world affairs. For example, the Nobel Prize for Literature, awarded since 1901, has been won by four Irish writers: William Butler Yeats (1923), George Bernard Shaw (1925), Samuel Beckett (1969) and Seamus Heaney (1995), whilst the fact that James Joyce did not win in the early twentieth century was very controversial. Irish writers of earlier periods such as Oscar Wilde, Oliver Goldsmith, Richard Brinsley Sheridan and Jonathan Swift would surely have been of a status to win such a prize had there have been a competition in their lifetimes. People of the Irish diaspora have also made major contributions, thus 20 of the currently 44 men who have been president of the USA had (or have) Irish ancestry, including Barack Obama who has Irish blood on his mother’s side. Irish music, dancing and other aspects of culture have become world-wide commodities from the musical show Riverdance to the ubiquitous international Irish pub, in which can be enjoyed, one hopes, good craic using that untranslatable Irish word for warm feelings and good fellowship. It is also of positive note to record that the Irish landscape is undeniably beautiful, the island’s characterisation as the ‘Emerald Isle’ conjuring up images of its lush green fields, although the grass grows so well only because it rains a lot and even the greatest lover of Ireland cannot pretend that its weather is pleasant!

On the other hand, beautiful Ireland has had a traumatic history. This can be evidenced by the fact that its population total today remains less than it was at the census in 1841. A famine in the mid- to late-1840s caused by Phytophthora infestans, a disease introduced accidentally from the Americas that blighted the staple crop of potatoes, together with an inadequate and tardy official response to relief, led to a high mortality rate. Limited international emigration had been occurring before the famine (Royle and Ní Laoire, 2006) but during that disaster there was a massive outflow of Irish people and this process continued for generations. Only in the mid-twentieth century did the population of Ireland stop declining. The resultant Irish diaspora means that there are many more people of Irish descent outside Ireland than live within its shores.

Further, Ireland is plagued by disunity, bitter rivalries and contestations that have blighted lives for many centuries. The most recent unrest, the three decades of disturbance known as the ‘Troubles’ from the late-1960s to the late-1990s, caused almost 3500 deaths within Ireland and beyond its shores. Most of the violence was confined to the northeast corner of the island itself (Fig. 1), but it spread to a limited extent to other parts of Ireland and outside it to Great Britain and Europe, particularly to English cities including but not limited to London. The Troubles were intimately related to one of the souvenirs of earlier Irish unrest, that it had become a divided island with an internal international boundary that splits it into two different polities. One is an independent state, the Republic of Ireland; the other, Northern Ireland, is within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the world’s longest official state name, invariably shortened to the UK. Such insular divisions are rare but are found elsewhere in the world as demonstrated in a new book edited by Baldacchino, 2013, Divided Islands. This author wrote the chapter therein on Ireland (Royle, 2013) and is delighted now to have been given the opportunity to follow up that piece by looking in this review essay ‘beyond the boundaries in the island of Ireland’.

Ireland and the ‘curse’ of Great Britain

First it is necessary to reprise something of the history of Ireland, so its political division can be understood. The basic issue is geographical, namely Ireland’s location just west of the much larger island of Great Britain. That location has always provided opportunities for Irish people who for centuries have migrated to Britain for work and residence. However, it has also been seen as Ireland’s ‘curse’ as the nationalist leader Wolff Tone put it in 1798 shortly before he was sentenced to death for leading a rebellion against the British. The English and then, after the Act of Union in 1707 when Scotland joined England and Wales, the British, needed to control Ireland. There was always a fear that Ireland would be used as a stepping stone into Britain for that country’s continental enemies, particularly the French and Spanish. Ireland had to be swept into the arms of England/Britain essentially to keep the latter nation safe. This policy can be traced back to 1169 when King Henry II of England mounted his first invasion of Ireland. Neither Henry nor his successors succeeded in gaining control of all of the island. The fourteenth century saw the depredations of the Black Death, the bubonic plague that killed about one-third of Europe’s population, which rather changed priorities. The following century brought to England the Wars of the Roses, a conflict which meant that Irish affairs were again neglected. The Irish were able to take advantage and pushed back the area under English control to an enclave around Dublin on the east coast known as ‘the Pale’. Then in 1542 England’s puppet Irish parliament in Dublin declared King Henry VIII of England to be also King of Ireland. After this renewal of interest in Ireland, the Pale was extended once more despite risings against the English with their unpopular foreign ways and customs, including the English language.

Ireland proving difficult to subdue militarily, the English decided on a different policy, that of changing Ireland’s population composition by encouraging migration of people into Ireland from England itself, also its tributary state of Wales and a little later, Scotland. This policy was called the ‘Plantation’ and can be dated first to the 1550s, when Queen’s County (now County Laois) was ‘planted’ with such migrants. In the province of Ulster in the north of Ireland, the local lord, Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone who had supported the Spanish in the wars between Spain and England was defeated in 1603 and he and other lords left Ireland. Their lands were issued to settlers from Great Britain to try to forestall further rebellions. This process, the Ulster Plantation, saw up to 80,000 Anglicans and Presbyterians, two significant Protestant sects, move into what had been heretofore largely a Roman Catholic island. These groups are all Christians but there was considerable rivalry between Catholics and Protestants and the Ulster Plantation extended an ethnic division within Ireland that was a significant factor in its later political division, given the different identities and cultures of the religious groups (Graham, 1997). The Ulster Plantation did not officially affect the two eastern Ulster counties of Antrim and Down, but they were settled privately largely through the immigration of Protestants from Scotland. One notable Country Antrim settlement from the early seventeenth century was Belfast, founded in 1603 (chartered 1613) on land granted to Sir Arthur Chichester, Lord Deputy of Ireland. Belfast was laid out within earthen ramparts for its immigrant Protestant population, local Catholics being required to reside outside the defences (Gillespie, 2007).

The aim of the plantation to bring peace failed in that there was an uprising in 1641 and the English reverted to a military strategy. In 1647 there was an unsuccessful campaign, then in 1649 the English parliament sent Oliver Cromwell with his New Model Army to invade Ireland. After a brutal campaign almost all land still owned by Catholics was confiscated. A generation later Irish Catholics were involved in the Jacobite Rebellions, which attempted to restore the Catholic English King James II who had been replaced on the throne by the Protestant William of Orange in 1688. The former king entered Ireland with French assistance, Ireland indeed being a stepping stone into England it was hoped. King William came himself to Ireland to oppose James and there was an encounter in 1690, the Battle of the Boyne. The Protestants won, James fled back to France abandoning his supporters who were finally routed at the Battle of Aughrim in 1691 (Ó Ciardha, 2001). The Battle of the Boyne is still celebrated in Protestant areas of Northern Ireland with marches on 12 July and bonfires the night before (Fig. 2). After the defeat of the Jacobites, Ireland remained as a separately administered state if under the British sovereign and dominated by Great Britain. Local control was through a Protestant ruling class known as the Ascendancy. Resistance continued but was largely conducted through low-key activity led by rural groups such as the Whiteboys.

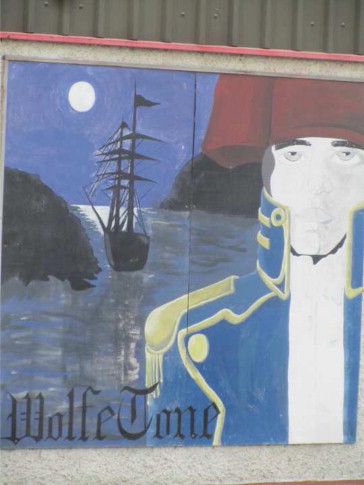

The late-eighteenth century saw liberalisation of trade in Ireland, which created the wealth that led to the fine streets and public buildings in Dublin from the period of Georgian architecture. This era was one of radicalism in Europe inspired by publications such as Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man (1791) as well as the practical examples of the American and French Revolutions. In Ireland radicalism saw protests against the British become more organised than had been the case for many years. In Belfast a body known as the United Irishmen was established, many members and leaders of which were Protestants, especially Presbyterians who also suffered discrimination in Ireland, if not to the same extent as the Catholic underclass. The United Irishmen campaigned for political reform, the establishment of an independent Irish republic and more generally for Catholic rights. Their leader was Wolfe Tone, himself an Anglican, the group most favoured by Ireland’s politics but who nonetheless wrote An Argument on Behalf of the Catholics of Ireland (1791). The United Irishmen and their followers were associated with rebellion. There was a potential French invasion in 1796, which was abandoned only because of poor weather conditions and in 1798, with some rather badly organised French assistance, there was a full-scale rising. This was suppressed with brutality. Wolfe Tone himself was captured on a French ship (Fig. 3) and sentenced to death but actually committed suicide to ‘cheat the hangman’. It was upon his capture that Tone had made his famous declaration that the ‘connection between Ireland and Great Britain [was] the curse of the Irish nation’ (see Moody et al., 2009).

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

After the 1798 rising, the British attempted to clasp Ireland even more closely to try to forestall further trouble. In 1800 the Irish parliament was manoeuvred to vote itself out of office with the British Isles becoming a unitary state in 1801, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Irish members were elected to the Westminster parliament in London. The islands were united officially but many of the traditional indigenous population of Ireland, mainly Roman Catholics, wished to be free from British rule. However, the minority Protestant population (a majority in parts of Ulster) descended from later migrants feared for their privileged position if Ireland were to become independent and they wanted to remain part of the UK. There were many clashes within Ireland between its Protestant and Catholic peoples, especially in Ulster. Belfast was especially troubled, with major disputes occurring on a number of occasions, usually but not always connected with the annual celebrations of the Protestant victory at the Battle of the Boyne. There were deaths in 1813; riots in 1824; attacks in 1828; riots in 1832; mounted troops had to be deployed to restore order in 1835; the army and extra police were brought in 1842; there was gunfire in 1852; riots in 1857; days of serious rioting in August 1864 engendered by a movement to repeal the Act of Union of 1801. Riots occurred again in 1872, 1880 and 1884; whilst in 1886 32 people were killed (Royle, 2011).

This was the era of the Industrial Revolution and the development of the mighty British Empire. Ireland participated in these processes. Belfast in particular became an industrial centre significant for its linen industry and even more for its shipbuilding. Irish people served the empire by making up a disproportionate part of the British army from humble foot soldiers to a number of generals, including the Duke of Wellington – who was not proud of his Irish birth. Ireland also provided many colonial administrators; it is ironic that Ireland, which can certainly be seen as England’s colony, contributed massively to running the British Empire. Ireland itself was rather neglected by Britain in the early-nineteenth century, most notably in the response to the Great Famine (An Gorta Mór in Irish) in the 1840s with official relief efforts being somewhat grudging, poorly organised and late to be applied (Woodham-Smith, 1962).

Towards the end of the century Irish affairs became much more significant in Westminster in that there was agitation for Ireland to be granted what was known as ‘home rule’, a policy supported by one of the major British political parties, the Liberals. Home rule would not have been full independence, but nonetheless, it was a step too far for the Ulster Protestants who opposed it, as did the British Conservative party. Home rule bills were defeated twice, in 1886 and 1893, but a third bill passed in 1914. There would certainly have been resistance in Ulster to Irish home rule – Rome rule (i.e. Roman Catholic) as it was characterised. On 28 September 1912, the last of the signatures to the Ulster Covenant and its associated document for women, the Ulster Declaration, were penned; documents signed by a substantial proportion of the Ulster population – 237,368 men and 234,046 women. In the Declaration, the women promised to ‘associate ourselves with the men of Ulster in their uncompromising opposition’ to home rule. The men signing the Covenant promised to use ‘all means which may be found necessary to defeat’ home rule. (The author first drafted this paragraph precisely 100 years later in Belfast to the sounds of marching bands commemorating the centenary, which were ringing out across the city). The men’s ‘uncompromising opposition’ would certainly have included armed resistance. Weapons had been smuggled into Ulster and a militia established in 1912, the Ulster Volunteers, formed into the Ulster Volunteer Force in 1913. Meanwhile in Dublin an equivalent force of nationalists, the Irish Volunteers, had been formed. Strife seemed certain to result but in the event the third home rule bill was not was not put into operation as the start of the Great War in 1914 led to it being postponed.

Most of the men of the Ulster Volunteer Force joined the British Army and the unit in which most served, the 36th (Ulster) Division, suffered tremendous casualties – 5500 killed, wounded or missing – on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. (This is another anniversary that sees marching bands take to Belfast’s streets). Also in 1916 came another significant event, the Easter Rising in Dublin. This was a rebellion in which nationalists led by Pádraig Pearse and his Irish Volunteers and James Connolly with his Irish Citizen Army occupied buildings in central Dublin on 24 April (Easter Monday, hence the name of the event). At the post office they read a text: ‘We declare the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland, and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies, to be sovereign and indefeasible... We hereby proclaim the Irish Republic as a sovereign independent state’. When the British recovered from their surprise and organised their forces, the group of about 1250 nationalists were considerably outnumbered by their opponents who put down the rebellion quickly and harshly, with a total of 460 deaths occurring amongst the soldiers, police, rebels and civilians. On 29 April Pearse surrendered his remaining forces. Sixteen nationalists were then executed, although one of the leaders, Éamon de Valera, was spared and subsequently became taoiseach (prime minister), then president of Ireland.

Ireland divided

At the end of the Great War in 1918 the British faced a conundrum with regard to Ireland. The third home rule bill had been passed if not put into operation in 1914; the unpopularity of their rule in most of Ireland was perfectly clear from the Easter Rising and the landslide victory of a nationalist party, Sinn Féin (which means ‘ourselves alone’), at the post-war election of 1918. On the other hand, the sacrifices of the Ulster Volunteer Force at the Battle of the Somme had to be taken into account and there was the near certainty of armed resistance if Ulster were pushed into an independent Ireland. Events on the ground caused further problems. The Irish Republic was declared in Dublin once more in 1919 and a fresh, armed campaign of violence, the War of Independence, started. This was countered, rather brutally, by a combined British army and police group known as the Black and Tans. During this strife the UK parliament passed the fourth home rule bill, the Government of Ireland Act in 1920. This act and the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which ended the War of Independence did not set up full independence for what became the Irish Free State – for example the British monarch remained head of state – and it also abolished the Irish Republic declared in 1919. Another feature was the near certainty that partition of Ireland would result. Unicameral parliaments were established in an area to be known as Northern Ireland with a provisional border around six of the nine counties of Ulster as well as another parliament for the remaining 26 Irish counties. There was a proviso that Northern Ireland be permitted to secede from the Irish Free State, which promptly it did on 7 December 1922 one day after that polity was officially established. Northern Ireland retained its sub-national legislature but returned to the UK (which was renamed as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 1927). There then followed a brief but unpleasant civil war in the Free State between competing nationalist groups who were either in favour of the 1921 treaty or against it. The pro-treaty forces won the day but years later, in 1937 Fianna Fail, the anti-treaty party, won an election under Éamon de Valera and a revised constitution that extended Irish independence was adopted. The state was renamed just ‘Ireland’ and the constitution laid claim to all of the island and its surrounding small islands. In 1949 the state of Ireland became a republic and is often now called the Republic of Ireland, for only context alerts one to whether the state or the island is meant when ‘Ireland’ is used alone.

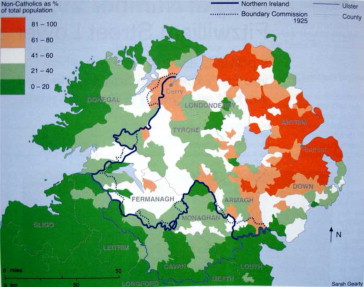

The provisional border of Northern Ireland was the county boundaries of Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry (called ‘Derry’ by nationalists) and Tyrone where they abutted the Irish border counties of Cavan, Donegal, Leitrim, Louth and Monaghan. The sixth Northern Ireland county, Antrim, has no international border. The term ‘Six Counties’ is sometimes used as a synonym for ‘Northern Ireland’ by nationalists who are often reluctant to denote legitimacy to the area by using its official name. These six counties were those with the greatest proportion of Protestants, but they also contained substantial Catholic areas, whilst some border counties in the Free State had smaller numbers of Protestants. It was assumed that a boundary commission would redraw the border to reduce Northern Ireland to an area that was as Protestant as possible using the declaration of religion on the 1911 household census schedules as evidence. There was nothing that could be done about substantial bodies of Catholic populations far from the border such as those in Belfast and the rural area of north Antrim. The Boundary Commission’s work had to be delayed because of the Civil War and it did not convene until 1924. Its deliberations were supposed to be secret but a map was leaked to a newspaper and published. This showed that in addition to territory being transferred to the Free State, there was a proposal to incorporate parts of County Donegal and a small part of County Monaghan within Northern Ireland (Fig. 4). The Irish side had assumed or at least hoped that no territory would be ceded, that all the transfers of land and people would be into the Free State. This potential loss of territory caused embarrassment to Dublin and all sides then agreed to compromise by accepting the 1920 provisional border as the international boundary between the UK and the Irish Free State (Hand, 1969; Anderson and Bort, 1999). This was declared formally in 1925. The Irish border is thus nothing more than a series of country boundaries, which originally delimited local government districts. Its imposition has led to difficulties. Some are minor, in places people have to go into a different state to get from one part of their area to another – thus the Belcoo Concession in County Fermanagh gave free passage across a finger of the Republic of Ireland. At a much more significant scale are the problems relating to the thousands of people who found themselves on the ‘wrong’ side of the border, a situation not unknown in other cases of partition such as that of India in 1947.

Amongst people in the Free State there seemed to be an initial feeling that having a border was illogical and that the feature would be ephemeral. For example, a popular travel book of 1937, Michael Floyd’s The Face of Ireland, stated that:

I suppose Europe can show other borders with as little geographical justification as this one but there at least is generally the division of language, while here the man with the crown over the harp on his hat [i.e. an official from Northern Ireland wearing British and Irish symbols] greets you in as rich a brogue … as the man with the harp only you have just left behind. For Ireland, whatever its political differences is one country; and it is only the arbitrary significance of this dotted line … that impels one to treat of the Six Counties as a separate … entity (Floyd, 1937, p. 87).

A few years later in 1950, a geographer, T.W. Freeman, acknowledged the significance and reality of the border but still not that it might become a fixture across the island:

The ultimate solution [to Ireland’s ‘political tensions’], acceptable to some but not to others, came in the twentieth century, and gave the country two political entities, which, it is already clear, differ so radically in policy and outlook on many social and economic questions that it is hard to see how they may eventually be united (Freeman, 1950, p. 113).

The battered former university library copy of Freeman’s book from which the quote was copied by this author has four comments at this point added by students. Disfiguring a library book is a disgraceful practice to be sure, but at least the comments have utility for they illustrate well Freeman’s phrase about the border being ‘acceptable to some but not to others’. The first comment says about the ‘two political entities’ ‘Who wants them united’, which attracted the response ‘You don’t have to say this, you know’. Then another hand accuses the first writer of being a ‘bigoted Ulsterman’, to which a fourth person wrote ‘every right to be so’. Sadly the contestation did not remain a matter restricted to bored students scribbling in textbooks inside the halls of academe. There were major campaigns of unrest in the 1920s, 1930s and 1950s and then the Troubles themselves from the late 1960s. Many of those involved in the unrest were Catholic nationalists from the ‘wrong’ side of the border, areas such as South Armagh, known unofficially to the British during the Troubles as ‘Bandit Country’. The unrest was about not just the location of the border so much as the validity of there being a border at all.

The Troubles can be traced back to the late 1960s, a time of radical unrest and action throughout Europe when a civil rights movement began in Northern Ireland, stimulated by the realisation that Catholics living there were disadvantaged, an underclass. However, civil rights protests soon escalated into serious unrest with the aim of nationalist (mainly Catholic) paramilitaries being to see the border removed and a united Ireland result; whereas unionist (mainly Protestant) paramilitaries countered them, wishing for the union of Northern Ireland with the rest of the UK to be maintained. After nearly thirty years and almost 3500 deaths the peace process brought the Troubles to an end with the Good Friday or Belfast Agreement of 1998. The Irish government gave up its claim to the whole island of Ireland under the Free State’s 1937 constitution, this being replaced by a recognition that ‘a united Ireland shall be brought about only by peaceful means with the consent of a majority of the people, democratically expressed’. The nationalist groups abandoned the armed struggle. In return, a North-South Ministerial Council was established to deal with areas for co-operation such as transport, tourism and the environment. Further, there is the British-Irish Council with representation from all the polities in the British Isles including the three Crown Dependencies of Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man, the three devolved UK administrations of Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales as well as the Westminster and Dublin parliaments.

Sinn Féin, in recent elections the dominant nationalist party in Northern Ireland and with a past that most assume was linked with the principal nationalist paramilitary organisation, the Irish Republican Army, accepted a place within the devolved government of Northern Ireland. What in other places would be the Prime Minister’s Office is in Northern Ireland the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister. The former always so far has been a unionist from the Democratic Unionist Party and the latter a nationalist from Sinn Féin. Given that the basic issue of there being an Irish border at all with a corner of the island of Ireland remaining under British rule, the underlying cause of the Troubles and all the turbulence that came before has not gone away. One cannot assume that unrest will not return. However, at the time of writing, matters are relatively quiet both on the border and in Northern Ireland generally.

The Irish border

The border has remained fixed; its location has never changed. However, its ‘thickness’, using this term to identify its permeability, has always varied over space and also over time. Some of its length runs along streams or rivers or through loughs but for much of its length the Irish border, that series of county boundaries, has no significant topographical expression, it runs through fields and farms and was crossed by tracks as well as main roads. At times of trouble, especially the time of the Troubles, the border has been more of a barrier, though always permeable. There were watchtowers and fortifications with the British army stationed at various posts along it. Isolated customs posts were not maintained because the safety of the officials was threatened, instead there were frequent mobile vehicle checks, usually on the British side, but sometimes one would be stopped by the Irish authorities. Routes across the border were restricted to officially approved crossings (Fig. 5). Other routes, of which there were many, were barricaded or cut off although locals would frequently restore them or develop other routes, perhaps tracks across fields, for the border was never fenced or barricaded. In the countryside along the border the presence of the feature, Floyd’s dotted line, was in practical terms, except at times when there was a local incident, little more than an inconvenience. Often it was an opportunity for there was smuggling, illegal as well as legal movements of people and goods took place to take advantage of price differentials. Livestock might be taken across border fields to qualify for EU subsidy payments from both states. At times people would come to the North (as Northern Ireland is usually referred to) to shop, at other times prices were lower in the South (the common term for the Republic of Ireland). Tax regimes differed, thus for a long time now there has been lower duty imposed on petrol and diesel in the South and drivers in the North within reasonable reach of the border cross it to fill up their cars, there are few petrol stations left in Northern Ireland within 10 km of the border. The border matters, and not just in political terms, systems are different now. They already were in 1950 when Freemen identified the differences and have become increasingly so as time has moved on. Health, education and judicial provision all change at the border. The currency is different, too. Northern Ireland, as part of the UK, uses still the British pound; the Republic of Ireland whose currency, the punt, was fixed to the pound until 1979, changed to the Euro in 2002. The economies are also different. For decades the North was more prosperous than the South, largely due to the connection with the rest of the UK thanks to transfer payments of various types. Then for a number of years in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries the prosperity of the Republic of Ireland was considerably greater. This was the period when the South was known as the Celtic Tiger and its well-educated, English-speaking workforce prospered in the computer and financial industries, with personal and national prosperity buoyed by a property boom. The 2008 crash took down the house prices and the economy both and the Republic of Ireland is greatly involved in the crisis facing the Eurozone and has had to be bailed out by the European Union. At the time of writing, the North is once again in less financial difficulty, if only because it is itself not within the Eurozone. In short, of the two mid-century comments about the border transcribed above, Floyd’s confident declaration that Ireland is one country and the border of arbitrary significance only, seems less prescient than Freeman’s comment about radical differences between the two political entities. Indeed as he Centre for Cross Border Studies has recently observed quoting a consultant’s report on North/South co-operation on public service provision: ‘80 years of separation have created innumerable individual difficulties and differences between the two systems, many of which are sufficiently profound to present enormous obstacles’ Pollak, September, 2012b. The publication from the Cross Border Centre went on to bemoan the fact that major investment was taking place on rail routes from Dublin to all parts of Ireland except the line to Belfast. So the border is significant.

This is not to say that ‘Northern Ireland is as British as Finchley’, a comparison made in 1981 by the then British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, who was MP for Finchley. For although it is in the UK, Northern Ireland is located on the island of Ireland and that has profound impact upon its people, their lifestyle and cultural practices, border or no border. Traditional Irish music is played and appreciated North and South; Irish cuisine straddles the border, too. People in Belfast pubs drink Guinness as a matter of course, just as they do in Dublin: there is more difference between Dublin and Cork in this regard for in the latter city in the far south of Ireland the domination of Guinness is challenged by the locally-brewed stouts, Murphys and Beamish. Irish whiskey is made by four distilleries, which produce a variety of products; three are located in the South and one in the North. People from the North might go shopping in Dublin; thousands own property and/or go on holiday to County Donegal, the most northerly county in Ireland, even though it is in the ‘South’. Some bodies operate on an all-Ireland basis from the Royal Irish Academy to the Commissioners of Irish Lights (which manages lighthouses all round the island). The island operates its electricity supply on an all-Ireland basis, the Single Energy Market. Many sports including rugby and cricket are organised across the island, international standard players from North and South both turn out for a team called Ireland.

By contrast, there are two international football teams, the one called Ireland represents in this sport just the Republic of Ireland and sometimes plays another international team called Northern Ireland. To further complicate matters, Olympians from Northern Ireland might represent Team Ireland or Team GB dependent upon personal preference or their sport’s organisation – boxing, for example, in which people from Belfast especially have often excelled, is organised on an all-Ireland basis. Golf is to be played in the Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games in 2016; Northern Ireland has three recent winners of majors in this sport: Rory McIlroy, Graham McDowell and Darren Clarke. The last might be rather too old for selection by 2016; the two others would be qualified for and presumably be courted by both the British and Irish teams and even in 2012 to their discomfort they are being hounded by people wishing to know where their allegiance lies. There can be few other areas where a sportsperson qualifies by virtue of the place they were born and live for two different Olympic teams. It must also be unusual for a state agency to supply application forms to its citizens wishing to obtain a passport from a different country but this happens with regard to Irish passports in Northern Ireland as the author observed recently in a Belfast post office.

As to the border itself, at present it is not dominant in the landscape, barely visible in fact. The watchtowers and British army bases have been dismantled, the blockages on the unapproved crossings mostly taken away or at least not restored by the authorities if removed unofficially (Fig. 6). When driving one is sometimes only aware the border has been crossed when a road sign is observed bearing different road numbers and distances in different units: kilometres are used in the South, miles in the North.

The future for the border is unclear. Officially the Republic of Ireland still wishes for Irish unity to take place and the British authorities would not stand against this if there was a clear majority of the Northern Ireland electorate who expressed such a desire. But given the financial costs which would be incurred from Irish unification and the realisation that it would almost certainly be accompanied by violence, there is at least tacit support in some quarters for the status quo to be maintained. Further, the Centre of Cross Border Studies published in August 2012 a statement from an unnamed senior Irish government official who opined that ‘People in the South are utterly happy with its 26 county shape: their mental map is the 26 counties.’ Additionally, there was a report on a telling confrontation on a television program between a young woman and Martin McGuinness, the Sinn Féin Deputy First Minister in the North who was standing for his party in the 2011 election for President of (the Republic of) Ireland. She said to him:

‘As a young Irish person, I am curious as to why you have come down here to this country, with all your baggage, your history, your controversy? And how do you feel you can represent me, as a young Irish person, who knows nothing of the Troubles and who doesn’t want to know anything about it (original emphasis)? (Pollak, August, 2012a)’.

Mr McGuinness won 13.7% of the vote and finished third, results far worse than Sinn Féin gets in Northern Ireland even though about half the votes there are taken by unionist parties and would never be available to Sinn Féin. Northern Ireland may not be as British as Finchley but nor is it as Irish as Dublin, it has instead been seen by travellers and researchers alike as having become ‘a place apart’ (Murphy, 1978; French and Regan, 2000).

References

- Anderson and Bort, 1999 Malcolm Anderson, Eberhard Bort The Irish Border: History, Politics, Culture. Liverpool University Press, Liverpool (1999)

- Baldacchino, 2013 Baldacchino, Godfrey, 2013. The Political Economy of Divided Islands, London: Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming.

- Floyd, 1937 Michael Floyd The Face of Ireland. Batsford, London (1937)

- Freeman, 1950 T.W. Freeman Ireland: Its Physical, Historical, Social and Economic Geography. Methuen, London (1950)

- French and Regan, 2000 French, Susan, Regan, Colm (Eds.), 2000. Northern Ireland: A Place Apart?: Exploring Conflict, Peace and Reconciliation, 80/20 Educating & Acting for a Better World: Bray. Co Wicklow.

- Gillespie, 2007 Raymond Gillespie Early Belfast: The Origins and Growth of an Ulster Town to 1750. Ulster Historical Foundation, Belfast (2007)

- Graham, 1997 Brian J. Graham In Search of Ireland: A Cultural Geography. Routledge, London (1997)

- Hand, 1969 Geoffrey J. Hand Report of the Irish Boundary Commission, 1925. Irish University Press, Shannon (1969)

- Moody et al., 2009 T.W. Moody, R.B. McDowell, C.J. Woods The Writings of Theobald Wolfe Tone, 1763–1798, Volume III: France, the Rhine, Lough Swilly and Death of Tone, January 1797 to November 1798. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2009)

- Murphy, 1978 Dervla Murphy A Place Apart. John Murray, London (1978)

- Ó Ciardha, 2001 Éamonn Ó Ciardha Ireland and the Jacobite Cause, 1685–1766: A Fatal Attachment. Four Courts Press, Dublin (2001)

- Paine, 1791 Paine, Thomas (Ed.), 1791. Rights of Man. J.S. Jordan, London.

- Pollak, 2012a Pollak, Andy, August 2012. ‘Does the South really want the North as part of Ireland?’, Notes from the Next Door Neighbours, 72, <http://www.crossborder.ie/notes-from-the-next-door-neighbours/does-the-south-really-want-the-north-as-part-of-ireland>.

- Pollak, 2012b Pollak, Andy, September 2012. ‘The challenge of turning goodwill into co-operation’, Notes from the Next Door Neighbours, 73, <http://www.crossborder.ie/notes-from-the-next-door-neighbours/the-challenge-of-turning-goodwill-into-cooperation>.

- Royle and Ní Laoire, 2006 S.A. Royle, C. Ní Laoire ‘“Dare the boist’rous main”: the role of the Belfast News Letter in the process of emigration from Ulster to North America, 1760–1800’. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 50 (1) (2006), pp. 56-73

- Royle, 2013 Royle, S.A., 2013. ‘Ireland’. In: G. Baldacchino (Ed.) The Political Economy of Divided Islands, London: Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming.

- Royle, 2011 S.A. Royle Portrait of an Industrial City: ‘Clanging Belfast’, 1750–1914. Ulster Historical Foundation for Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society, Belfast (2011)

- Tone, 1791 Tone, Wolfe, 1791. An Argument on Behalf of the Catholics of Ireland. Society of United Irishman of Belfast, Belfast.

- Woodham-Smith, 1962 Cecil. Woodham-Smith The Great Hunger. H. Hamilton, London (1962)