The development of small islands in Japan: An historical perspective

Kagoshima University, 1-21-30 Korimoto, Kagoshima-shi, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan kuwahara@leh.kagoshima-u.ac.jp

Abstract

Japan is an island country which has nearly 7000 islands, of which only 421 islands are inhabited. Many of the remote (or small) islands had been left underdeveloped since prewar periods. In consequence, the disparity between the remote islands and mainland Japan widened, and thus, Japanese government undertook a development policy of remote islands based of the enactment of Remote Islands Development Act. The aim of the act was to eliminate “backwardness”, and full-fledged development of remote islands was launched by pouring a lot of national budget. The paper gives a brief history of remote islands development in Japan, and explains about the two types of remote islands development acts, and then, takes up the cases of Amami and Okinawa, and discusses about the changing role and meanings that these acts have brought.

Keywords

Remote island, Remote island development act, Amami islands, Okinawa islands

Introduction

Japan, which extends roughly 4000 km from northeast to southwest along the northeastern coast of the Eurasia mainland, comprises five main islands, Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu, and Okinawa, with countless “rito” – remote (or small) islands.1 There is no clear definition of the word “rito”, however, according to the report The Present State of Maritime Security, published by the Japan Coast Guard in 1987, the threshold for inclusion in this category is of having a coast of more than 100 m in circumference. According to this definition, the Japanese archipelago consists of 6852 islands, including the northern territories (the islands of Etorofu, Kunashiri, Shikotan and Habomai), of which 421 are inhabited and more than 90% uninhabited (Nihon Rito-center, 1996: 1–2).

In 1952, 7 years after the end of the war, the Japanese government implemented a development policy for remote islands. Most of the remote islands, which are located predominantly in the western part of Japan, had been left underdeveloped in prewar periods. In consequence, the gap between the remote islands and mainland Japan widened, and thus, the Remote Islands Development Act was enacted. The aim of this act was to “eliminate backwardness” in remote islands, and the act launchd a fully-fledged development policy backed by a substantial national budget (ibid.: 3). However, this act was not applied to the Amami, Okinawa and Ogasawara islands because these islands remained under US military control at this time. Instead, due to the delayed reversion of these islands to Japan, the Special Development Acts were enacted to these islands to reduce the gap in income level between the mainland and these islands.

Thus there have been two types of development act in Japan with regard to its remote islands, reflecting different development policies. The difference of the two acts is in the rate of treasury’s share or subsidy, i.e., the rate of subsidy for Amami, Ogasawara, and Okinawa is much higher than that of the other remote islands.

There are many studies on the promotion and development of Japanese remote islands. However, many of the studies on remote or small islands have been conducted by Nihon Rito Center2 (Japan Remote Islands Center) which was established in 1966 as a foundation under the jurisdiction of Economic Planning Agency of Japan (current Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transportation and Tourism). The center has published its public relations magazine called Shima which started in December 1953. It contains articles on introducing islands, commentary of remote islands act and projects, reports of group activities, events, and so on.3 The center has also published Annual Report of Remote Islands Statistics since 1970. Since the Remote Islands Development Act has been extended every 10 years, many studies tends to focus on analyzing the current situation of remote islands and forecasting the future (Yamaguchi, 2009; Suzuki, 2006; Yokoyama, 2002; Uemura, 2001; Chii, 1996; Ooshiro, 1995; Yamashina, 1992; Uenae, 1985; Kon’no, 1985).

The paper gives a brief history of the development of remote islands in Japan, and discusses on the changing roles that the Remote Islands Development Act has played in Japanese postwar history.

Brief description on Japanese remote islands

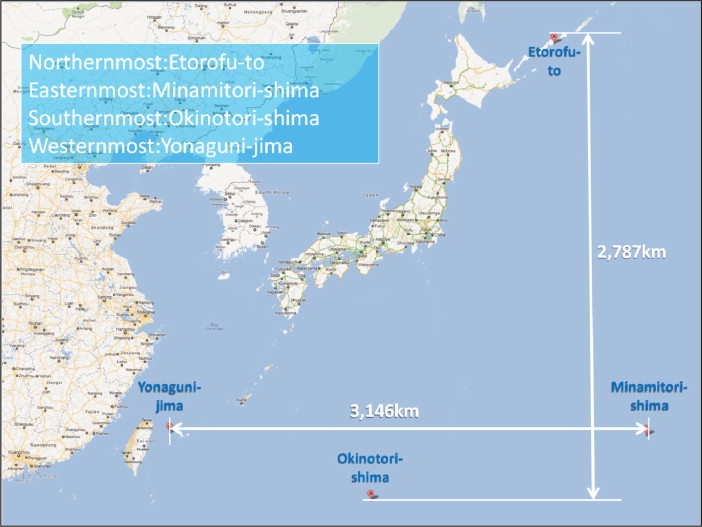

The area of Japan is located between the lines of 120° and 150° east longitude and between 20° and 45° north latitude. The northernmost region of Japan is Etorofu Island, which has been held by Russia and there live no Japanese. Minami-torishima island and Okino-torishima island, which are the easternmost and the southernmost regions of Japan respectively, are off limits of the public. The westernmost region of Japan is Yonagunijima island of Okinawa, which is an inhabited island. The northernmost and the easternmost regions where Japanese are living are both in Hokkaido, Cape Souya the northernmost and Cape Nossapu the easternmost. The southernmost region of Japan is Haterumajima island of Okinawa where about 500 islanders are living (Map 1).

The distance between north and south (from the southernmost Okino-torishima to northernmost Etorofu island) is 2,787 km, whereas the distance between east and west (from the easternmost Minami-torishima to the westernmost Yonagunjima) is 3146 km. Thus Japan is located within the area of about 3,000 km long toward the north, south, east and west.

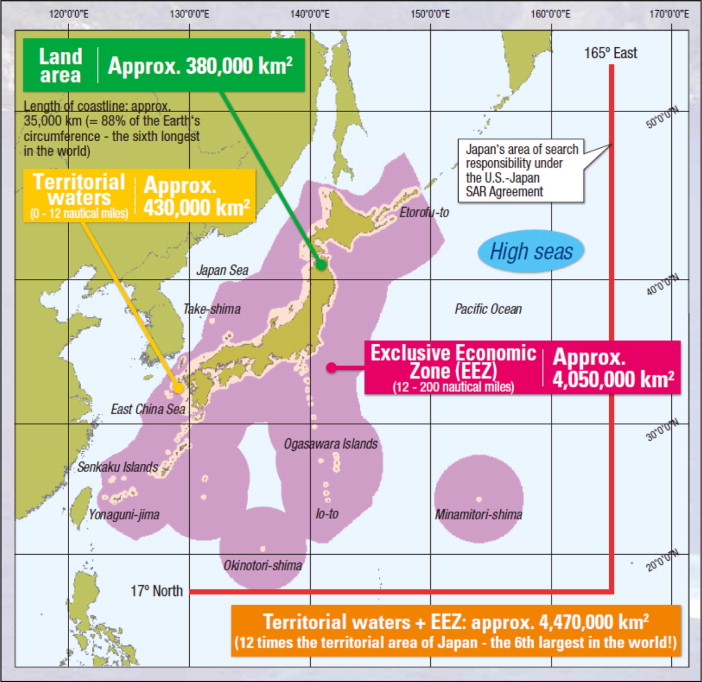

One of the most noticeable roles of the outer islands is the securement of territory. All of the international borders of Japan are on the sea. With these islands being scattered on the outer edge of Japanese territory, the territorial waters and 50% of the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ: a sea area extending up to 200 nautical miles or 370 km) are secured. Thus, despite ranking only 61st in the world in terms of territory (380,000 square kilometers), Japan’s territorial waters and EEZ combined are 12 times as large (4,470,000 square kilometers) as its territorial area, placing it 6th in the world.4 Surrounded on all sides by wide expanses of sea, Japan is a maritime nation that enjoys the extensive right on the ocean water and the benefits of the sea in the form of maritime trade and fishing. However, those waters are also plagued by various problems including marine crime such as smuggling and trafficking, and international disputes over the sovereignty of territorial possessions and maritime resources (Map 2).

The total population of the remote islands (excluding Amami, Okinawa and Ogasawara islands) was 920,000 in 1960, while it decreased to 470,000 in 2000, and the decrease ratio is higher than the nationwide ratio (Nihon Rito-center, 1996: 2–4). Thus it has long been a challenge for Japan to sustain the residential population in the remote islands.

While remote islands are under tough natural conditions, due to being surrounded and isolated by the sea, the natural environment is well preserved and offering distinguished scenery. Thus most of the remote islands are designated as national parks, quasi-national parks or prefectural natural parks. The ratio of natural parks against the total land area is 14% in the nation, whereas that of remote islands is 38%, thus remote islands have rich environmental resources. The great nature of remote islands, which form the peripheral borders in the island nation of Japan, are designated as 13 national parks, 13 quasi-national parks, 14 prefectural natural parks and 35 marine parks (Rito-shinko 30nen-shi Hensan Iinkai, 1999: 300–301). Also, 15 islands are active volcanic islands in these national parks.5 Thus, these remote islands could be viewed as a national asset that has to be well preserved for the future generations.

As mentioned above, out of the 421 inhabited islands in Japan, the area which are the measure for remote island development based on Remote Island Development Act is 261 islands, and the total area (in comparison to the total of whole Japan) is about 5000 square kilometers (14%), and the total population 470,000 (0.8%).

| The number of the remote islands designated to development acts | |

|---|---|

| Remote Islands Development Act | 261 |

| Act on special measures for the development of Ogasawara islands | 2 |

| Act on special measures for the promotion and development of Amami islands | 8 |

| Act on special measures for the promotion and development of Okinawa | 39 |

| Total | 310 |

| (Nihon Rito-center, 2004: 1–3; Nihon Rito-center, 2011) | |

As most of the remote islands are located in the western part of Japan, these areas are susceptible to typhoons. Once hit by a typhoon, regular ship services, which are the lifeline for remote islanders, would be forced to cancel for a few days, and islanders would suffer the damages on ports, facilities of fishing harbor, private houses and public facilities. Also farmlands would be flooded or damaged by seawater.

Historical background of Remote Islands Development Act

Since Maiji era (1868–1912) until the end of the World War II, Japanese government had continued a discriminatory measures and policies against remote islands such as restricting autonomy, voting right, and compulsory education (Rito-shinko 30nen-shi Hensan Iinkai, 1990: 14–15). Due to financial crisis, inflation and economic recession in late 1920, rural areas were impoverished, and thus, Japan proceeded into Sino-Japanese War and the World War II. Due to the wars, Okinawa islands were turned into battlefield, and people in Ogasawara islands were forced to evacuate (ibid.:16). Right after the war, Soviet army moved into the northern territory (Chishima islands) and those islands of Tokara, Izu, Ogasawara, Amami, and Okinawa were put under US military occupation.

Among the islands which were cut off from Japan right after the war, Izu islands were returned to Japan in March 1946, and then, followed by Tokara in 1952, Amami in 1953, Ogasawara in 1968, and Okinawa in 1972. Also, Remote Islands Development Act was enacted in 1953, and followed by the act on Special Measures for the Reconstruction of Amami islands in 1953, the act on Special Measures for the Development of Ogasawara islands in 1969, and the act on Special Measures for the Promotion and Development of Okinawa in 1971. The main policies of these acts were in implementation of public work projects to improve such infrastructures as traffic, industry, life environment, and national land conservation (ibid.).

During postwar time, due to the rapid growth and structural change in Japanese economy, island societies also experienced significant changes. The policy of high economic growth caused the outflow of population from the whole area of remote islands. At the same time, rapid migration occurred from villages to a main city or town in a big island, or from subordinating islands to a main island in the group of islands. Some islands were even deserted. Hachijo-kojima (91 people) of Tokyo became uninhabited in 1969, Gajajima (41 people) of Kagoshima prefecture in 1970, Kazurajima (122 people) of Nagasaki prefecture in 1973, Takashima (38 people) of Shimane prefecture in 1975, and Orishima (112 people) of Nagasaki in 1976 ibid.).

Due to the enhancement of high-speed transportation network and information system, urban people became more nature-oriented, and remote island boom from late 1970s to 1980s brought a lot of tourists to remote islands. UN Convention on the Law of the Sea was ratified and taken effect in 2006, and Japan entered the year of 200 nautical mile economic zones, by which the islands became true asset for the island state of Japan (ibid.).

Enactment of Remote Island Development Act

The governor of Nagasaki prefecture6 called for four other governors of Tokyo, Niigata, Shimane and Kagoshima to discuss about the development of remote islands, and issued a prospectus on Remote Islands Development Act, and carried on campaigns toward the enactment of the act on the development of remote islands in January 1953.7 As a result, the act became law as temporary legislation with a 10 year term limit on 15 July 1953, and issued in public on 22 July 1953. After that, the act was revised and extended five times down to this day (Nihon Rito-center, 2004: 20–21).

Since the enactment of Remote Islands Development Act in 1953, Remote Islands Development Plans were implemented every 10 years. The First Remote Islands Development Plan (1953–1962) was focused on the improvement of fundamental conditions which were necessary for eliminating the backwardness caused by the isolation or remoteness from the mainland and for promotion of industries by developing social infrastructure. Article 1 advocates its purpose as to “develop the economy of islands remote from the mainland, …… through the establishment of measures to improve fundamental conditions which are necessary for eliminating the backwardness caused by their isolation or remoteness from the mainland and to promote their industries” (Rito-shinko Sanjunen-shi Hensan Iin’kai, 1990: 80–81).

The Second Remote Islands Development Plan (1963–1972) summarizes the features of remote islands as being surrounded by the sea, being narrowed, and being isolated, and predicates that these regional conditions affect the economic and social stagnant tendency of remote islands. Also it predicates that these features are to cause great obstacles against regional development. As the basic measures to overcome the present situation such as this, improvement of transportation and telecommunication was considered as the basic measures for eliminating the backwardness. Also the aging of employed population by migrant workers caused low production, low income and low purchasing power or so called “the malignant cycle of poverty” (ibid.: 81).

The Third Remote Islands Development Plan (1973–1982) sets a policy agenda according to character types of remote islands to include various issues of remote islands. This classification breaks 300 islands down into 5 types based on population size, hydrographic conditions, nautical time and distance, the distance from the central city of mainland, and the geographical form of each island.8 The plan also issues strengthening of collaboration between local industries and tourism, and promotion of marine recreation under the guideline for developing industries that try to make the best of geographical conditions of the remote islands (ibid.: 81–83).

The Forth Remote Islands Development Plan (1983–1992) has the subtitle of “for creative vigor of remote islands”. With the perspective on the age of international marine segmentation of the ocean waters since 1977, the plan issued that “remote islands are placed on the situation that they have to undertake an important new role on the use and control of the resources and space of the surrounding sea areas”. Thus the plan referred for the first time to the national role that remote islands had to undertake due to changing international situation. Also it emphasized the creation of “rich and dynamic remote island society by improving the constraint conditions due to their special circumstances”. (ibid.: 83–84)

In July 2002, Remote Islands Development Act was revised and a new remote islands development started based on the amended law from April in 2003. In the amended Remote Islands Development Act which came into force in 2007, not only the viewpoint of “rectifying gaps caused by their isolation or remoteness from the mainland”, but also the direction to revitalize the area were shown by rethinking the gaps between remote islands and mainland as “valuable gaps” because remote islands play an important national role and utilize the resources unique to each local area.

Since Remote Islands Development Act was enacted in 1953, Japanese government and local governments have conducted development measures strongly and steadily, and made considerable achievements in improving remote islands’ basic conditions and industrial infrastructure. The total amount of public works spending related to remote islands development during last 51 years from fiscal year 1953 to 2004 reached to 44,153 billion yen, in which 13,748 billion yen (31%) for fishery infrastructure, 7904 billion yen (18%) for road building, 7757 billion yen (17.5%) for port and harbor, 4903 billion yen (11%) for agriculture and farming, and 2670 billion yen (6%) for seacoast (Nihon Rito-center, 2004: 60).

Act on special measures for the Amami islands

Directly after the end of World War II, the Amami islands were put under the short eight-year period of occupation by Allied Forces’ General headquarters. On January 29th, 1946 a memorandum from the Allied Forces’ Supreme Headquarters placed the Amami islands and Okinawa under the same division of administration. In 1951, The Amami Oshima Reversion Council was formed and as a result of the campaigning on the entire island, Amami Oshima reverted to Japan on December 25th, 1953.

The economy of the Amami islands was completely devastated at the time of the reversion so the Japanese government established the “Special Measures Law for the reconstruction of the Amami islands” in 1954 and implemented the reconstruction. But the average income of the islanders remained less than half of the national average and showed no signs of improvement. So the “Special Measures Law for Development of Amami islands” and the new “Special Measures Law for Promotion and Development of Amami islands” were established in the second and third terms, respectively. The laws have eventually become known by their Japanese abbreviation “Amashin”. In 1994, the revised Amashin Law was established and a ten-year extension to 2003 was enacted.

In this way, the name of the “Special Measures Law for the Amami islands” established in June of 1954 was revised from “Reconstruction” to “Development” and then to “Promotion and Development”. This law has also been revised and has had its term extended every 5 years. But it retains consistent underlying objectives, which are to raise the average income level on the Amami islands to the level of Okinawa and the mainland islands of Japan and to make the Amami islands economically independent.

Almost 1.44 trillion yen for operating expenses have been poured into the islands for the task so far in the 45 years since the Amami islands reverted to Japan. Projects entailing large-scale modifications of the natural landscape such as roads and harbors occupy almost eighty percent of the entire budget (Kuwahara, 2001: 77).

One-third of the Amami islands’ population emigrated during the last 40 years. Most of the people who left were between 14 and 40 years old, which is the prime age range needed in the industries on the islands. As a result, the aging problem has become increasingly serious. The number of persons 65 years old or higher increased by 97.4%. In fact, persons 65 years old or higher occupied 22.9% of the total population of the Amami islands in 1995. This is a significantly high percentage compared to the national average of 14.5% or the Okinawa prefecture average of 19.7% (ibid.).

An ever-increasing number of people have started pointing out that in this intense pursuit to actualize a higher average income and to reach the level of the mainland islands, the very identity of the Amami islands will be lost. They say that it will be the end of the islanders’ independent consciousness as Amamians.

For the Amamians, the half-century since the reversion to Japan has been a period of naively following the policy called Amashin. But more and more people in the Amami islands are awakening to the true opulence of their islands. They are opening their eyes to their exuberant natural environment and culture. They are also trying a diversity of means to make this more widely known.

Act on special measures for Okinawa

Okinawa prefecture consists of 160 islands which are scattered across an oceanic area of 1000 km from east to west and 400 km from north to south. The number of inhabited islands in Okinawa is 48, of which the remote islands under the jurisdiction of Remote Islands Development Act account for 40 except 7 islands which are connected by bridges. The total area of the remote islands under the act comprises 45% of the prefecture’s total area (Ooshiro, 1995: 89).

The population of the inhabited remote islands under the act decreased by 25% from 170,000 in 1955 to 130,000 in 1990, and the percentage of the total population of the prefecture decreased from about 20% in 1955 to 10% in 1990. During the period above, the population of Okinawa prefecture increased 53% from 800,000 to 1,220,000, and most of the increased population concentrated on the South-Central area of mainland Okinawa (ibid.).

While Japanese remote island development policy has been premised on the Remote Islands Development Act, in the case of Okinawa, it has been developed by the act on Special Measures for the Promotion and Development of Okinawa. The Remote Islands Development policy enacted so far has centered on infrastructural development and facilities improvement, the result of which are considerable one but have not, in themselves, solved the problems of the remote islands (ibid.: 94).

Article 1 of the act on the Promotion and Development of Okinawa9 advocates the purpose of this act as to help the self-sustaining development of Okinawa for the promotion of the livelihoods and job security and the improvement of welfare of the people.

In order to develop the social infrastructure, which stagnated during the US period of administration, the First Promotion and Development Plan (1972–1981) actively invested in the public sector and ensured high rate subsidies from the national government. Also in order to create self-sustaining industrial structure, the focus was put on introduction of manufacturing industry. As a result, the gap in social infrastructure between Okinawa and mainland Japan was greatly redressed.

With the exception of sugarcane, the primary industries, producing vegetables, flowers, ornamental plants and livestock, showed a steady increase in the post-Reversion period; while secondary industries, such as the construction business, grew considerably because of the increase in public investment. In the tertiary industry, tourism and related activities showed a considerable increase. The number of tourists and tourism revenue increased from 200,000 visitors and 14,500 million yen revenue in 1971 to 1,930,000 visitors and 197,100 million yen in 1981. The gap in national income per capita between Okinawa and mainland Japan decreased from 56.7% in 1972 to 70.7% in 1981.

The Second Plan (1982–1991) also set out the key policy goals as the rectification of the gap in national income per capita between Okinawa and mainland Japan and development of the basic conditions for self-sustaining development. Particular focus was put on the “promotion and development of industry”. As a result, the development of social infrastructure and tourism industry showed a steady progress. However, the gap in the national income per capita of Okinawa against mainland Japan persisted, remaining at 71.5% in 1990.

In the Third Plan (1992–2001), “development as a distinctive region” was added as a goal in addition to “the rectification of the gap between Okinawa and the mainland” and “development of basic conditions for self-sustaining development”. In order to achieve the economic self-sustainability of Okinawa, a high value was placed on the further development of tourism and resort industry and their related activities through deepening the exchange with Asian regions using Okinawa’s advantage of being the nation’s southernmost region.

The Fourth Plan (2001–2011) removed the word “development”. The national government has conducted the promotion and development of Okinawa by investing 7 trillion yen for the last 30 years since the reversion to Japan. However, the national income per capita of Okinawan people is still the lowest in Japan, at 70% of the national per capita income, and the unemployment rate is still high at 7.9%. While social infrastructure was developed by the government’s promotion policy, the economic self-sustainability of Okinawa that has been a main goal is far from being achieved. Rather, the present situation depends more on government expenditure such as public construction.

More than 1 trillion yen had been poured as the expenditure of remote islands development project, of which 26% was dispersed in Ishigakijima, and 25% in Miyakojima, thus the total of the two covers more than 50% (Ooshiro, 1995: 97).

Changes in Japanese remote islands policy

As we saw above, some changes in the Japanese government’s remote islands policy can be identified across the period. Firstly, a change from development to environmental protection can be pointed out. As Yakushima and Ogasawara islands were registered as World Natural Heritage areas in 1993 and 2011, respectively, remote islands, which had long been viewed as areas necessary for “eliminating the backwardness” or for “rectifying gaps in average income between remote islands and mainland”, came to be viewed as symbolizing biodiversity and environment protection. The biodiversity and unique natural environments of Amami, Okinawa and Ogasawara islands came to be recognized widely, which also brought a significant change in people’s perceptions about remote islands.

Secondly, a shift from security, national defense, economic development, and resources development to the identification of the value of island diversity can be identified. As can be seen in the issue of Northern territory and recent disputes on Takeshima and Senkaku islands, understanding of the importance of remote islands in national security has been markedly enhanced. Through the EEZ, the area of Japan expanded 12 times beyond the national land area, adding rich marine resources to confined national landmass. The EEZ is also important for developing fisheries, marine and seabed resources. At the same time, the importance of protecting biodiversity and diverse natural and cultural environments rather than mere developing resources have come to be recognized.

Thirdly, the history of remote islands development can be viewed as a history of liberation from the concepts of disparity or gap, such as “eliminating the backwardness caused by their isolation or remoteness”. People’s views on remote islands have gradually changed from being symbolic of backwardness to the islands as places to recover human nature, vitality, healing and comfort (Nihon Rito-center, 2004: 192). With the development of the economy, consumers’ needs in urban areas tend to be getting more nature-oriented, health-oriented, handmade-oriented, individual character-oriented, and authenticity-oriented, and as a result, become more diversified. Thus, meeting the diversified needs of consumers leads to regional revitalization (Ooshiro, 1995: 102–103).

Remote islands have increasingly been viewed as a trove of diversity due to the registration of Yakushima and Ogasawara as World Natural Heritage areas. Also, since the music of Okinawa and Amami have become popular in mainland, remote islands become increasingly important as a source of culture (Hayward and Kuwahara, 2008).

Concluding remarks

The Japanese government has promoted development policy by two types of Development Act, i.e., the Remote Islands Development Act and the Act on Special Measures for Promotion and Development for Amami, Ogasawara and Okinawa. Both acts have been revised and extended every 10 years, and played an important role in developing and promoting remote islands to this date.

Japanese remote islands, which are located on the outer border of the national territory, drew less attention before the war. However, immediately after the war, a border issue with Korea over Tsushima island emerged and the importance of the islands in Japanese border issue was reaffirmed (Rito-shinko 30-nen-shi hensan Iinkai, 1999: 5), but it was long after the war that the importance of the islands came to be recognized such as security of Japanese territory, coastal economic zone, marine resources, conservation of natural environment, protection of precious plants and animals, preservation of traditional culture, provision of healing space, and so on.

In the past, measures for promoting remote islands were planned and conducted for the purpose of “eliminating the backwardness caused by their isolation and remoteness from the mainland”. In its amended act in 2002, the national role that remote islands were expected to play such as “securing of national territory” was newly added to the act. As the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea came into effect in 2006, Japan acquired a large Exclusive Economic Zone. By rethinking the gap between mainland and remote islands as a “valuable gap” (Nihon Rito-center, 2004:192), and by taking measures with the best use of local inventiveness, the self-sustaining development of remote islands is to be advanced.

For an island country like Japan, the promotion of remote islands which border on foreign countries can contribute not only to the stabilization of life and improvement of the welfare of people living on those islands, but also to enhance the economic development and benefit of entire people.

Remote islands are blessed with various regional resources such as rich nature, fresh seafood, and rich tradition and culture. They are also precious “healing spaces” which could offer a healthy and affluent life (ibid.: 190). In recent years, with the diversification of values among the people, those who wish for a balanced life are getting increasingly interested in remote islands. Furthermore, exchange between remote islands and the mainland would not only bring an economic effect but also contribute to the vitalization of remote island areas.

Endnotes

References

- Chii, 1996 A. Chii “200 Kairi Jidai to Rito Shinko Hou no Houkou” (The age of 200 nautical mile and the direction of Remote Island Development Act). Shima, 42 (2) (1996), pp. 51-59

- Hayward and Kuwahara, 2008 P. Hayward, S. Kuwahara Transcience and durability: music industry initiatives, Shima Uta and the maintenance of Amami culture. Perfect Beat, 8 (4) (2008), pp. 44-63

- Kon’no, 1985 S. Kon’no “Korekara no Rito Shinko wo kangaeru” (A discussion on the future of remote islands). Kouwan, 62 (5) (1985), pp. 7-16

- Kuwahara, 2001 Kuwahara, S., 2001. “Amami Oshima”. In: Aoyama, T. (Ed.), Beyond Satsuma. Kagoshima University Research Center for the Pacific Islands, pp. 64–77.

- Nihon Rito-center, 1996 Nihon Rito-center, 1996. Rito Shinkou Handobukku (Remote Island Development Handbook). Kokuritsu Insatsukyoku.

- Nihon Rito-center, 2004 Nihon Rito-center, 2004. Rito Shinkou Handobukku (Remote Island Development Handbook). Kokuritsu Insatsukyoku.

- Nihon Rito-center, 2011 Nihon Rito-center, 2011. 2009 Rito Toukei Nenpou (Annual Report on Remote Islands Statistics). Nihon Rito-center.

- Ooshiro, 1995 T. Ooshiro “Rito Shiko Seisaku: Tenkan no Hitsuyousei to Houkou” (Remote island policy: a need of change and direction). Sangyou Sougou Kenkyu, 2 (1995), pp. 87-114

- Rito-shinko Sanjunen-shi Hensan Iin’kai hen, 1990 Rito-shinko Sanjunen-shi Hensan Iin’kai hen, 1990. Rito-shinko Sanjunen-shi Ge (Thirty years’ History of Remote Islands Promotion). Zenkoku Rito-shinko Kyogikai.

- Rito-shinko Sanjunen-shi Hensan Iin’kai hen, 1999 Rito-shinko Sanjunen-shi Hensan Iin’kai hen, 1999. Rito-shinko Sanjunen-shi Jou (Thirty years’ History of Remote Islands Promotion). Zenkoku Rito-shinko Kyogikai.

- Suzuki, 2006 Y. Suzuki “Rito Shinko Hou no Genten to sono Mokuhyo” (The original point of Remote Island Development Act and its goal). Nagasaki Wesleyan Daigaku Gendai Gakubu Kiyo, 4 (1) (2006), pp. 61-67

- Tanaka, 2008 K. Tanaka “Kaiyo Kihon Keikaku to Rito Shinko” (Marine master plan and the development of remote islands). Shima, 54 (1) (2008), pp. 54-64

- Uemura, 2001 S. Uemura “Kagoshima no hito wa hokoreru ka? 21 Seiki no Rito Shinko ni mukete no Kagoshima kara no Ichi-kosatsu” (A discussion from Kagoshima toward the development of remote islands in 21 century). Kagoshima University Research Center For The Pacific Islands Occasional Papers, 35 (2001), pp. 45-57

- Uenae, 1985 T. Uenae “Rito Shinko no Kon’nichi-teki Kadai” (Current issues of the development of remote islands). Kouwan, 62 (5) (1985), pp. 12-16

- Yokoyama, 2002 Yokoyama “Rito Shinko Hou no Kaisei ni tsuite” (On the amendment of Remote Island Development Act). Gyokou, 44 (4) (2002), pp. 28-32

- Yamaguchi, 2009 H. Yamaguchi “Rito Shinko no Genkyo to Kadai” (Current state and issues of the development of remote islands). Chousa to Jouhou, 635 (2009), pp. 1-10

- Yamashina, 1992 Y. Yamashina “Rito Shiko Taisaku no Genjo to Kadai” (Current state and issues on the measures of the development of remote islands). Bouei Daigakkou Kiyo, 64 (1992), pp. 1-49