Holistic conservation of bio-cultural diversity in coastal Lebanon: A landscape approach

Landscape Design and Ecosystem Management, Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences, American University of Beirut, P.O. Box 11-0236, Riadh Al Solh, Beirut, Lebanon jm08@aub.edu.lb jalamakhzoumi@gmail.com

Surfaces Design, P.O. Box 13-5545, Chouran, Beirut, Lebanon1 hala@surfacesdesign.com

Agriculture and Urban Planning, Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, University of the Holy Spirit (USEK), P.O. Box 446, Jounieh, Mount Lebanon, Lebanon2 carine.lteif@gmail.com carinelteif@usek.edu.lb

Abstract

Bridging terrestrial and marine ecosystems, Mediterranean coastal littorals are important floral and faunal habitats and an important component of the traditional Mediterranean landscape mosaic. The expanding urban footprint in Mediterranean littorals is increasingly threatening semi-natural sites and agriculture in coastal landscape. This paper proposes a holistic landscape approach to the sustainable planning of coastal littorals arguing that it is more likely to succeed because it is integrative of the concerns for safeguarding environmental resources and conservation of biodiversity but also responsive to socio-economic concerns of securing agricultural livelihood and providing for the cultural needs for open/green spaces by the growing inhabitants of coastal cities. The challenge is to combine protection for the three seemingly disparate activities. The town of Damour on the Mediterranean coast of Lebanon is taken as a case study. The wide coastal, banana cultivated plain makes for an exceptionally verdant landscape and scenic reprieve in an otherwise predominantly urbanized coastline. The methodology of ecological landscape design is applied to secure a holistic reading of the physical setting and propose a holistic, integrative conceptual model for the protection of coastal biodiversity that is ecologically sensitive and in synergy with agricultural and cultural uses.

Keywords

Mediterranean, Coastal landscapes, Biodiversity conservation, Sustainable agriculture, Lebanon

Introduction

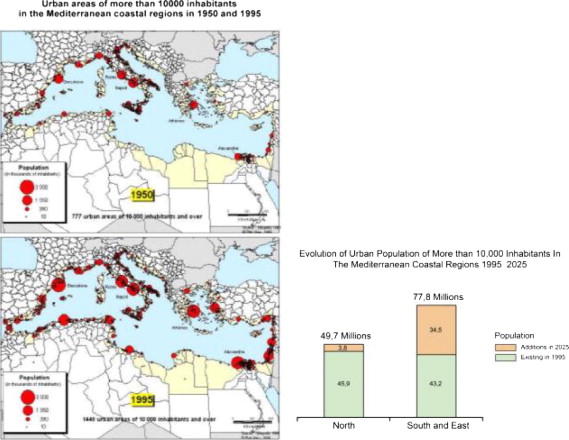

Mediterranean coastal littorals are rapidly urbanizing. Population in urban settlements increased from 285 millions in 1970–427 millions in 2000 and will probably reach 524 millions by 2025 according to Blue Plan trend scenario (Antipolis, 2001). The ecological and environmental impact of population concentration and intensified human activities threaten biodiversity and natural resources and alter local climates. The Mediterranean Sea is also designated as a world ‘biodiversity hot spot’, its flora estimated at 25,000 plant species, 7.8% of the world species, of which 50% are endemic to the region (Myers et al., 2010). The threat to biodiversity is all the more worrying considering that coastal landscapes represent the interface of marine and terrestrial ecosystems and as such are important habitats for wildlife that warrant protection. Historically, coastal landscapes were an integral component of the network of wildlife habitats (riparian, highland, woodlands, orchards), partly natural and partly managed, that characterized the Mediterranean countryside. The impact of urban expansion affects not only natural resources but as well the quality of life in cities. As the urban footprint expands, the inhabitants of the city are distanced from contact with nature, deprived of green and open spaces.

The dual impact of high population concentrations and economic activities on coastal lands, ‘caostalization’, is especially severe in the southern and eastern Mediterranean (Antipolis, 2001) (Fig. 1). With a few exceptions, the countries in the southern and eastern littorals have high rates of population growth, developing economies and weak physical planning. Developing the economy, providing employment, services and infrastructure is generally the priority, not biodiversity conservation and environmental sustainability.

Lebanon in the eastern Mediterranean is in many ways a microcosm of the urbanizing Mediterranean problematic. Although a small country (10,452 square kilometers), high mountains, wide valleys, coastal and inland rivers make for terrain and climatic diversity that harbors a wealth of endangered fauna and flora. Lebanese coastal landscapes are increasingly demonstrating the phenomena of ‘coastalization’; 55% of the country’s 4.4 millions population live in the coastal plain which includes as well the country’s four largest cities and the capital, Beirut. Attempts to assess the damage to environment and natural resources by the state with support from international organizations have resulted in several comprehensive studies of Lebanese coastal environments and the state of biodiversity3. By 2003 the MoE secured a number of Protected Areas, mostly Cedar reserves in the higher altitudes but also two Protected Areas that are littoral and marine, respectively, Tyre Beach Nature Reserve and Palm Island Nature Reserve. Nevertheless, state initiatives are predominantly exclusive to ‘nature’. They fail to incorporate semi-natural and agricultural landscapes in the coast or recognize the bio-cultural diversity of the traditional Mediterranean landscape. The latter is aggravated by the absence of coordination between state agencies that care for the environment and nature conservation and those responsible for agriculture and forestland. Failure to consider the diversity and synergy between natural, managed and cultural landscapes is noted by Naveh (2008) who critiques the ‘ingrained tendency to fragmentize and take apart what is in reality whole and one’, attributing the rift to the divergences between the ‘bio-centric’ approach of scientists the ‘anthropo-centric’ approach of social scientists. The outcome has been a compartmentalized approach, an either or focus on ‘nature’ and the ‘natural’ or ‘culture’ and the ‘cultural’, that undermines ecological integrity and compromises the character of Mediterranean regional landscapes (Makhzoumi et al., 2012).

This paper is a response to the fragmented, piecemeal approach to the bio-cultural diversity characteristic to Mediterranean coastal littorals. Instead the holistic landscape framework is proposed that addresses concern for biodiversity conservation, agriculture and urban development in coastal littorals. Shifting the focus from ‘nature’ to ‘bio-cultural’ conservation, the paper argues, is valid because it responds to the layered and multifunctional structure of traditional landscapes in the region (Makhzoumi, 1997). The holistic landscape approach proposed is interdisciplinary, drawing on continuing research into coastal urban biodiversity (Chmaitelly et al., 2009; Talhouk et al., 2005a), urban agriculture (Lteif, 2010) and the application of the holistic methodological framework of ecological landscape planning (Makhzoumi, 2012, 2000; Makhzoumi and Pungetti, 2008; Makhzoumi and Pungetti, 1999).

Applications of a holistic/landscape approach to bio-cultural diversity conservation

Historical evidence suggests that the expansion of domesticates and agricultural economies across the Mediterranean was accomplished in waves of colonization that came to establish coastal farming enclaves around the Basin (Zeder and Sabloff, 2008). The process involved as well domesticates and domestic technologies by indigenous populations in Mediterranean littorals and the domestication of endemic species. Human environmental impact is especially evident in the islands with the replacement of island endemic species with faunas imported from the mainland. Nevertheless, up to the middle of the twentieth century traditional agricultural practices continued to maintain the high levels of biodiversity characteristic in the region since the Neolithic (ibid). Presently, the spatial and ecological diversity of traditional Mediterranean rural landscapes sustains a diversity of wildlife just as traditional management practices of semi-natural and agricultural landscapes contributes to the high level of endemism (Makhzoumi, 1997).

Traditional rural landscapes the world over are shrinking, threatened by urban and suburban encroachment. In Europe, for example, virtually all semi-natural landscapes are the products of traditional agricultural, hydrological, and silvicultural management regimes. Land-use changes by the expanding footprint of cities and infrastructural networks fragment and eventually replace unique and species-rich habitats. Accepting that urbanization is the dominant pattern of land use change, it becomes necessary to question conventional approaches to biodiversity conservation and the narrow and exclusive focus on ‘nature’ (Bengtsson et al., 2003). Broadening the focus of nature conservation, however, implies accepting the resilience of natural processes that ecosystems have the ability to reorganize after large-scale natural and human-induced disturbances. Spatial resilience in natural ecosystems takes the form of ‘ecological memory’ that is composed of species, their interactions and structures that make ecosystem reorganization possible (ibid). Ecological memory can be found in abandoned sites and disturbed patches everywhere. Above all, the implication is that the prevailing focus on “static reserves” should be complemented with “dynamic reserves”, such as ecological fallows and dynamic successional reserves that are part of ecosystem management mimicking natural disturbance regimes at the landscape level (ibid). Zasada et al. (2010) argues similarly that efficient nature conservation lies not in protecting isolated territorial pockets but by shifting the focus on spatial systems and by incorporating conservation into other territorial policies. And while the focus on ‘territory’ is spatial the focus on ecosystem and process is well aligned with the idea of ‘landscape’ as the “the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors”.4

Other applications of the holistic approach are in conserving urban biodiversity which in essence takes into account the ability of wildlife to adapt to the new stresses, food sources, predators and threats in urban and suburban environments, where they can thrive in close proximity to humans. In turn, urban biodiversity provides socially valuable ecosystem services. Business parks, housing, roads and waterways can enhance biodiversity and encourage species to colonize urban areas by creating ecological corridors and networks to evade obstacles, thereby providing access to favorable habitats. This cultural environment constitutes open spaces that can be cultivated for vegetation and wildlife and provides ready-made laboratories for studying evolution and adaptive processes (Hunter 2007). The focus on dynamic process in urban biodiversity conservation becomes a means to reestablish natural processes in cities, for example through a re-wilding (Diemer et al., 2003). Applied to inactive industrial areas, infrastructural corridors, abandoned orchards and vineyards in suburban lands can be conceptualized as wilderness. Above all, incentives should be created to widen the current biodiversity management paradigm, and actively engage local stewardship associations in adaptive co-management processes of urban parks and surrounding green spaces (Barthel et al., 2005).

Yet another approach looks at agriculture with the aim of shifting the priority from production towards sustainable management and biodiversity conservation (Hunter, 2007; Moore and Margaret, 2005). Urban agriculture is an alternative that can offer advantages to wildlife conservation if less intensive agricultural procedures are adopted in cultivated fields and pasture patches (Sorace, 2001). A landscape framework serves well if used logistically and informatively to recognize and re-appropriate cultural values, for example the visual character and shared identity in a territory, as a value added in sustainable agriculture development (Paolinelli, 2002; Zurayk et al., 2010). Local self-reliance in food production, using nutrients accumulating in our cities, is increasingly regarded as an important aspect of sustainable urban development. Together with initiatives on energy efficiency, high resource productivity and policies for containing sprawl, urban agriculture can contribute considerably towards greener future cities.

The state of coastal landscapes in Lebanon

Lebanon’s Mediterranean coastline is formed by marine sediments and river deposited alluvium with sandy bays and rocky beaches (Fig. 2). Geomorphologic diversity includes sandy beaches (Chekka, Batroun, Jbeil, Maameltein, Ramlet el Bayda, Jnah, Damour, Tyre), coastal cliffs (Ras el Chaqaa, Bayada at Naqoura), rocky capes (Ras Es-Saadiyat, Nabi-Younes, Sarafand) and bays (Jounieh and Naqoura) (ELARD, 2011). Thirteen coastal waterways flow through deep gorges from the mountains westwards into the Mediterranean Sea.

The coastal ecosystem is of the Mediterranean type with a sub-tropical tendency. Human disturbance accounts for the evolution towards a richness of annual and ephemeral plants, found in irregular patches of non-systematic associations. More than half the plants are endemic, surviving at the edge of urbanized areas in between industrial and commercial sites and in agricultural lands (Chmaitelly et al., 2009; Talhouk et al., 2005a,b). Floral diversity in coastal littorals is under threat. A survey of the waterfront in Beirut shows that only 23 families, 81 species, survive compared to 63 families, 330 total species, listed in 1930s (Chmaitelly, 2007). Despite the considerable reduction in coastal floral diversity, the research findings indicate that in term of spatial distribution, rocky and sandy beaches, coastal cliffs, and vacant lots in Beirut continue to serve as wildlife habitats in comparison to managed landscape, respectively 76% and 24% (ibid). The highest floral diversities were recorded in coastal cliffs and fenced vacant plots respectively, 47 and 34 species. The absence of disturbance in these sites encouraged the establishment of mixed plant communities of native species and naturalized garden escapees. Rising land values will gradually leave little open space for spontaneous plants to colonize, which will invariably destroy naturalized coastal habitats and alter the landscape character of the waterfront.

Semi-natural landscapes are spatially associated with coastal agriculture. The reverse, however, is not necessarily true. While spontaneous plants have the ability to establish in the smallest of spaces given the opportunity, agriculture requires relatively large areas to be economically feasible. Historically, agriculture in coastal littorals was extensive, especially in the proximity of coastal towns and cities. Citrus (Citrus sinensis) and mulberry (Morus sp.) orchards in nineteenth century extended to a distance of 4 km south and east of the walled harbor city of Beirut (Davie, 1996). A traveler in 1832 noted the existence of mulberry, carob (Ceratonia siliqua), fig. (Ficus carica), orange and pomegranate (Punica granatum) orchards interspersed with widespread olive groves (Olea europea) (Al Wali, 1993). Mulberry trees dominated because they served for the production of silk destined for exportation (Lteif, 2010).

Demographic shifts during the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) were considerable. Rural population fleeing the countryside sought shelter in coastal cities, settling in informal settlements in urban peripheries on land that was then in active cultivation. The expanding urban footprint since has raised land values, which in turn precludes agricultural uses because they are no longer competitive economically.

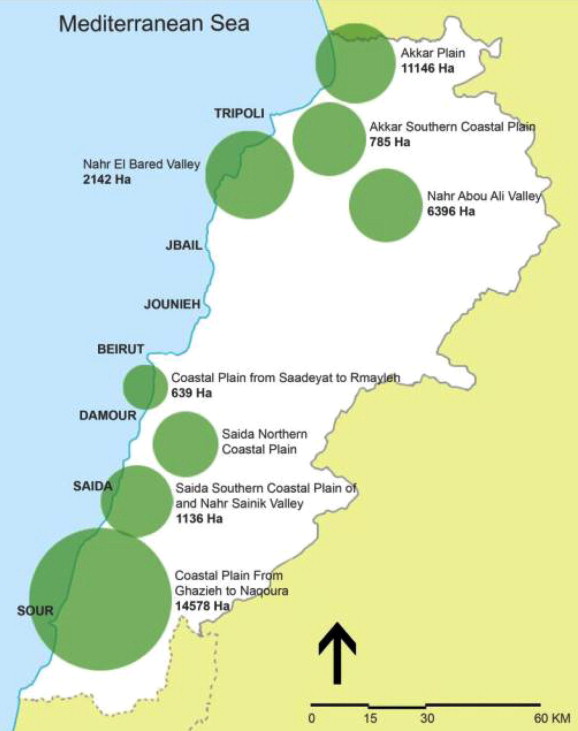

Today, coastal agriculture in Lebanon is limited to eight clusters (Huybrechts, 2004) (Fig. 3). Listed from the extreme north southwards these are: the Akkar Plain; Akkar Southern plain; Abu Ali Valley; Nahr El Bared River Valley; the coastal plain from Saadiyat to Rmayleh (that includes Damour case study); Saida Northern coastal plain and the Nahr el Awali Valley; Saida Southern coastal plain from Saadiyat to the Nahr Sainik Valley; and the wide coastal plain extending from Ghazieh north of Tyre to Naqura, Lebanon’s southern borders. Agricultural production in littoral agricultural zones is dominated by fruit trees, for example, oranges and citrus trees, bananas (Musa sp.) but also strawberries (Fragaria sp.) and table vegetables (Compain, 2004). In most clusters, cultivation of tomatoes and cucumbers is in greenhouses, fruit trees and other vegetables in open fields.

Coastal agriculture in the periphery of cities is increasingly under threat from rising land values. Agricultural lands are at a greater risk from urban encroachment than semi-natural landscapes (ibid). Deterioration of the agriculture sector in Lebanon since the 1970s is another contributing factor to the decline in coastal agriculture. Importation of low-priced agricultural produce from neighboring countries, the degradation of infrastructure, irrigation, production and marketing chains, continue to contribute to the failure of agriculture in Lebanon (Nasr, 2004). This decline is most pronounced in the coastal strip, mainly between Tripoli in the North and Saida in the South, even though this central part plays a key role in supplying fresh produce to the domestic market in cities (ibid).

The urban and suburban and associated uses occupies an almost equal share of the Lebanese coastal plain as agriculture, respectively 40% and 41% of the total area; Natural and semi-natural landscapes are restricted to 19% (ELARD, 2011). Piecemeal replacement of natural and agricultural landscapes by an ever expanding urban footprint disrupts marine and terrestrial ecosystems, degrades natural and semi-natural habitats and compromises coastal biodiversity (Cori, 1999). The threat to coastal landscapes is not limited to urbanization. The coast is the hub for commercial and financial activities; 65% of large industrial zones are in the coastal plain. Additionally, are Lebanon’s four commercial ports; Beirut’s port is the largest in Eastern Mediterranean. Coastal tourism, including marinas and beach resorts, archeological sites are similarly coastal activities (ELARD, 2011). The growing demand on coastal resources aggravates long-term bio-geophysical effects such as sea-level rise, shoreline erosion, sediment deficits and saltwater intrusion into coastal aquifers (ibid). The incremental loss of open coastal landscapes is just as detrimental to the inhabitants of coastal cities. Public access to green areas is a prerequisite to community health, physical and emotional wellbeing. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends 10 m2/capita. The per capita share of green areas in Beirut is <1 m2. Spatial limitations invariably raise land values in cities, which make it costly if at all feasible to appropriate land for parks and green areas.

Having established that coastal open landscapes are threatened, the challenge becomes how to protect these landscapes and address these three seemingly disparate activities, biodiversity conservation, agriculture and the problematic of expanding coastal cities. The case study of Damour is herein discussed to examine the morphology and ecology of open coastal landscapes and demonstrate application of the holistic landscape framework.

The Damour case study

Damour is a coastal town of 8000 inhabitants twenty kilometers south of Beirut. The settlement is located in the foothills of the Lebanon Range, 50 m above sea level. The coastline is 4 km long, a mixture of rocky and sand beaches. The foothills recede leaving a relatively wide cultivated plain. Banana plantation makes up 70% of the coastal plain, extending eastwards to utilize the lower reaches of the Damour River which defines the southern limit of the coastal plain. The extensive area under cultivation has Damour listed as a one of the eight clusters of coastal agriculture identified earlier. Alongside agriculture in the coast and the lower reaches of the river is a cover of degraded scrubland dominated by herbaceous species that occupies 55% of the land cover. In contrast the landscape of the eastern, inland aspect of Damour is of dense scrubland, conifer and oak woodlands that make up 33% of the land cover.

Phoenician, Greek and Roman remains testify to the historical roots. In the 19th century the village was known as a hub for silk production. Mansions of rich industrialists flourished alongside traditional farm houses, silk factories two of which remain constitute Damour’s rich architectural heritage. A more recent built heritage are unfinished concrete structures of apartment houses that speak of the suffering endured by the people of Damour during Lebanon’s civil war and abandonment thereafter. Damour is one of few locations close to the capital city’s metropolitan sprawl still affording a view to the Mediterranean Sea. The scenic setting viewed from the motorway is all the more impressive because of the juxtaposition of sea and verdant plain (Fig. 4).

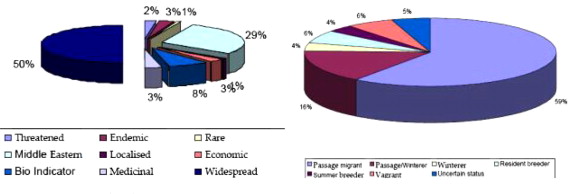

Damour falls within ‘inferior Mediterranean or Thermo-Mediterranean zones’ on calcareous soil and as part of the Carob-Mastic series and of Quercus calliprinos series in the Damour River (El Beyrouthy, 2008). Each series includes specific species, for example in the Carob-Mastic series the tree arrangement takes the form of garrigue, degraded scrubland, composed of the mastic tree (Pistacia lentiscus L.), myrtle (Myrtus communis L.), and less frequently by carob trees (C. siliqua L.) (ibid). Semi-natural associations in the coastal littorals are of garrigues dominated by Calicotome villosa, and in localized areas, of Rhus tripartita. In areas that are more degraded, garrigues of Poterium spinosum L. and Phlomis viscosa are present in rocky places. Inland the advanced scrubland of oaks (Quercus calliprinos Webb.) with or without pine trees (Pinus brutia Ten.) In both series however, carob and mastic shrub and myrtle are relatively abundant (ibid). A survey of the native flora in Damour lists 370 plant species distributed over 71 families, of which 10 are threatened species, 14 endemic, 3 rare, 131 east Mediterranean and 22 economic species (Mehdi, 2004) (Fig. 5).

Coastal agriculture is an integral part of the history and identity of Damour. Nevertheless patterns of production have changed. In the late nineteenth century mulberry trees (Morus sp.) dominated coastal agriculture, the leaves of the tree used to feed the silkworm. The remaining towers of two abandoned silk factories tower over the coastal landscape. A senior resident, owner of a large banana plantation in the Damour River plain, explains that there were four silk factories and that they accounted for accumulated wealth in Damour as well as securing livelihoods in neighboring villages. With the introduction of synthetic silks in the 1930s, the production of silk declined and mulberry cultivation was replaced with orange trees. For two decades, citrus orchards spread across the Damour plain before they too were replaced by banana cultivation (Fig. 6). In the last decade, Damour’s verdant coastal plain and sandy beaches have been targeted as prime, up-market beach resorts. The Maronite Wakf5 owns a large share of the coastal plain in Damour (around 500,000 m2) and rents the land out to agricultural entrepreneurs. The remaining lands are privately owned by the inhabitants of Damour. Banana makes up 15% of Lebanon’s agricultural production. And though banana cultivation is a key export to neighboring Syria and Iraq, it is nevertheless under threat from more profitable economic ventures, namely, high end beach resorts, hotels and chalets. “In ten years, there won’t be a meter square of land left that is not built” laments a Damour banana plantation owner.6

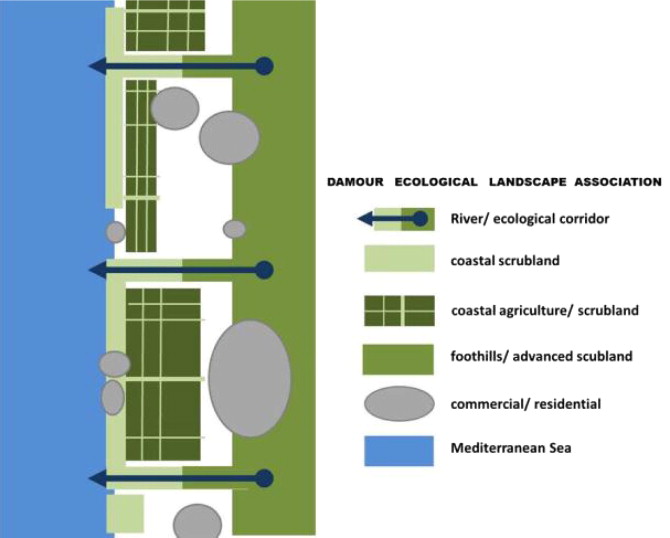

The methodology of ecological landscape planning (Makhzoumi and Pungetti, 1999) was applied to develop a broad and dynamic framework for sustainable future planning and management. The outcome, the holistic landscape conceptual model, is inspired by the landscape mosaic of Damour. The model articulates spatially existing landscape components of Damour, re-conceptualizing them as Ecological Landscape Associations (ELAs) (ibid). While ‘ecological’ implies that each of the components is an ecosystem, whether coastal, riparian, or agricultural, bound together and anchored to their environment through regulatory processes, ‘landscape’ is the external, visual expression of abstract ecosystem, made explicit visually and spatially. The combination of hidden process and explicit spatiality offers several advantages. On the one hand, the model is easier to comprehend by non-scientists, planners, businessmen, farmers and the public at large. On the other, spatial zoning that is responsive to local ecosystems forms a sound basis for initiating an engaging discourse with all stakeholders, proposing legislation and flexibility in phasing sustainable management. And because the ELAs are responsive ecologically, the synergy and complementarity between landscape components (natural, semi-natural, agricultural and urban) is emphasized. As a result, the conceptual model maintains landscape connectivity and ecological integrity as well as recognizing the character and identity of the territory. A schematic representation of the holistic conceptual model for Damour is shown in Fig. 7. The ELAs making up the model include the following five components:

- The Damour Riparian landscape that serves as an ecological corridor linking the foothills to the sea;

- Coastal scrubland, protected semi-natural coastal corridor. The coastal corridor realizes two connections. On the one hand, it maintains the marine/terrestrial ecosystem interface and on the other links the coast via the riparian landscape to inland landscapes of Damour;

- Inland advanced scrubland, or oak and pine in the riparian landscape but also degraded uplands and marginal landscapes on the eastern aspect of Damour;

- Agriculture-scrubland interface, a hybrid landscape that is predominantly agricultural but that includes semi-natural narrow strips that separate the agriculture parcels;

- Contemporary development that includes discontinuous pockets of coastal tourism, defined limits for urban and commercial uses.

As explained earlier, the spatiality of the ELAs encourages the development of strategic guidelines that can ensure ecological integrity and environmental sustainability. To demonstrate, strategic guidelines are herein elaborated for that aim to synergize agriculture and biodiversity conservation. The guidelines are multifaceted, working independently or in tandem. Three are herein elaborated: first, the introduction of native and endemic species as an alternative crop in agriculture; second, a gradual move to integrated pest management that is sustainable environmentally; and third, the gradual introduction of organic agriculture as a viable option.

Native and endemic species are slowly disappearing in coastal landscapes (Talhouk et al., 2005b; Zahreddine et al., 2004). The first set of guidelines is to re-introduce them with the aim of reversing the predominantly monoculture cultivation that dominates in Damour. Banana cultivation can be complemented with native species listed earlier, for example, the carob tree (C. Siliqua) and the mastic tree (P. lentiscus L.) which are productive and of economic benefit to the farmers but also provide structure and mass for wildlife. These trees can be planted to demarcate cadastral boundaries and/or as plantations. Either way, their productivity will enhance the livelihoods of local farmers. Native trees can enhance as well Damour townscape instead of the ubiquitous eucalyptus that was introduced during the French Mandate in the first decades of the twentieth century. The memory of silk production should also be recognized as a bio-cultural heritage of Damour, the tree reintroduced as it has all but disappeared from the landscape.

The second set of guidelines aim for agricultural management that is sustainable environmentally. Presently, farmers use chemical pesticides excessively which has dire effects on environment and biodiversity. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) constitutes a first solution as it is an effective and environmentally sensitive approach to pest management that relies on a combination of common-sense practices. IPM programs use current, comprehensive information on the life cycles of pests and their interaction with the environment. This information, in combination with available pest control methods, is used to manage pest damage by the most economical means, and with the least possible hazard to people, property, and the environment. IPM takes advantage of all appropriate pest management options including, but not limited to, the judicious use of pesticides.7

The third strategy is to initiate the introduction of organic agriculture. Organic agriculture is defined as “a holistic production management system that promotes and enhances agro-ecosystem health, including biodiversity, biological cycles and soil biological activity. It emphasizes the use of management practices in preference to the use of off-farm inputs, taking into account that regional conditions require locally adapted systems”.8 Compared to conventional farming the potential of organic farming to accommodate semi-natural habitats and host 30 more wild species depending on geographic location, aspect and altitude.9 Also see FiBL, 2011, Organic Agriculture and Biosiversity, available at http://www.fibl-shop.org/shop/pdf/1548-biodiversity.pdf. Practices like crop rotation, the use of organic fertilizers, and a reduction of tillage increase the density and richness of soil indigenous organisms like earthworms and arthropods. Organic farmers can become custodians of biodiversity at the genetic level, through the use of locally adapted seeds and breeds, at the species level, through the efficient use of nutrients and energy cycling, and at the ecosystem level, through greater reliance on natural pest control and the preservation of wildlife habitat around cultivated terrains (ibid). Sustainable and ecologically sensitive agricultural practices play an important role by raising public awareness of the landscapes, biodiversity and sustainable environmental practices. Lebanon has witnessed a surge in organic agriculture that appears to be gaining in popularity. There is also the potential of attracting people to alternative tourism related to agricultural production, for example ecotourism and agri-tourism, thus enhancing the livelihood of farming communities.

Conclusion

It is difficult if at all possible to unravel the intertwining of ‘nature’ and ‘culture’ in traditional rural landscapes in Mediterranean littorals. Rather, this paper has argued that biodiversity conservation should be broadened beyond the prevailing focus on ‘nature’ and the ‘natural’ to embrace as well ‘culture’ and the ‘cultural’. And because ‘landscape’ is part ‘nature’ part ‘culture’, tangible and spatially contiguous, a holistic landscape approach has the potential to breach the binary classification integrating biological and cultural concerns for protecting coastal littorals.

The holistic conceptual model proposed for Damour integrates seemingly disparate land uses with the aim of addressing concerns for biodiversity conservation, agriculture and the urbanization in coastal Lebanon. Naveh (1994) favors the term ‘ecodiversity’ to imply maintaining and restoring the dynamic flow equilibrium between biodiversity, ecological, and cultural landscape heterogeneity, as influenced by human land uses that occur at different spatial and temporal scales and with varying intensities.

The underlying logic of the proposed zoning, the spatiality of ELAs and their responsiveness to the existing landscape, is readily appreciated by the local stakeholders, professionals and lay persons alike. As such, the model has the potential to serve as working basis for a participatory discourse that engages local stakeholders in Damour, farmers and religious Wakf, developers and municipal authorities. The discourse is a necessary step to debate the divergent aspirations of stakeholders and a tool to change conventional practices in agriculture and explore alternative, i.e. bottom-up, participatory planning.

Another advantage of the holistic landscape model is its flexibility in phasing implementation of management. Phased in time, the focus can single the development of one component, for example strategic shift of current agricultural practices. Alternatively, two or more components can be selected, to focus on spatial continuity and ecological networking, for example the coastal corridor of semi-natural landscape and Damour River. Flexibility is especially necessary if community-generated planning is to complement physical planning at the national level. Additionally, adopting ‘landscape’ as the spatial basis for planning, has the value added of protecting scenic values of open/green coastal landscapes, a national heritage that is as threatened as biodiversity in coastal Lebanon.

In essence, the model is but an idea and tool. The real challenge, one that is specific to the context of developing countries in the Mediterranean lies in finding alternatives to market driven development that prioritize on short-term economic return rather than long term environmental sustainability. Whether in agriculture, tourism or realty markets, market driven, neoliberal forces undermine public rights (Makhzoumi, 2011). Community inclusive and multi-faceted, the landscape approach proposed has the potential to enhance agricultural livelihoods, through agro-tourism and biodiversity related tourism and as such empower local communities and enable them to become active participants in the planning process.

Endnotes

References

- Antipolis, 2001 Antipolis, S., 2001. “Urban sprawl in the Mediterranean region”. Mediterranean Blue Plan. (http://www.planbleu.org/publications/urbsprawl.pdf/08/03/2012).

- Al Wali, 1993 Al Wali, C., 1993. Bayrut fi Al Tarikh Wal Hadara. Beirut, Dar Al E’lem Lel Malayeen (Arabic).

- Barthel et al., 2005 S. Barthel, J. Colding, T. Elmqvist, C. Folke History and local management of a biodiversity rich, urban cultural landscape. Ecology and Society, 10 (2) (2005), pp. 1-10

- Bengtsson et al., 2003 J. Bengtsson, P. Angelstam, T. Elmqvist, U. Emanuelsson, C. Folke, M. Ihse, F. Moberg, M. Nyström “Reserves, resilience, and dynamic landscapes”. Ambio: Journal of Human Environment, 32 (6) (2003), pp. 389-396

- Chmaitelly, 2007 Chmaitelly H., 2007. “Urban floral diversity in the Eastern Mediterranean: Beirut coastal landscape”. Master of Science Thesis, American University of Beirut (unpublished).

- Chmaitelly et al., 2009 H. Chmaitelly, S. Talhouk, J. Makhzoumi Landscape Approach to the conservation of floral diversity in Mediterranean urban coastal landscapes: Beirut seafront. International Journal of Environnemental Studies, 66 (2) (2009), pp. 167-177

- Compain, 2004 D. Compain Le rôle économique de l’agriculture sur le littoral Libanais. J. Nasr, M. Padilla (Eds.), Interfaces: Agricultures et villes à l’Est et au Sud de la Méditerranée, Delta Publication, Beirut (2004)

- Cori, 1999 B. Cori Spatial dynamics of Mediterranean coastal regions. Journal of Coastal Conservation, 5 (2) (1999), pp. 105-112. http://www.10.1007/BF02802747/13/03/2012

- Davie, 1996 Davie M., 1996. Bayrout Al Qadimat : une ville arabe et sa banlieue à la fin du XVIIIème siècle-National Museum News 3 (http://www.almashriq.hiof.no/lebanon/900/902/MAY-Davie/Bayrout-al-Qadimat.html/13/03/2012).

- Diemer et al., 2003 M. Diemer, M. Held, S. Hofmaeister Urban Wilderness in Central Europe Rewilding at the Urban Fringe. International Journal of Wilderness, 9 (3) (2003)

- ELARD, 2011 ELARD, 2011. “Vulnerability and adaptation of coastal zones”. The European LEADER Association for Rural Development. Study by the Ministry of Environment with support from the UNDP (http://www.moe.gov.lb/ClimateChange/pdf/SNC/d-Coastal%20Zones.pdf/15/03/2012).

- El Beyrouthy, 2008 El Beyrouthy M., 2008. “Contribution à l’ethnopharmacologielibanaise et aux Lamiaceae du Liban”. Université Droit et Santé, Lille2, France (unpublished PhD Thesis).

- Hunter, 2007 P. Hunter The human impact on biological diversity. How species adapt to urban challenges sheds light on evolution and provides clues about conservation. EMBO Reports, 8 (4) (2007), pp. 316-318

- Huybrechts, 2004 E. Huybrechts Enjeux de l’urbanisation des espaces agricoles du littoral Libanais. J. Nasr, M. Padilla (Eds.), Interfaces: Agricultures et villes à l’Est et au Sud de la Méditerranée, Delta Publishers, Lebanon (2004)

- Lteif, 2010 Lteif C., 2010. “Urban Agriculture Landscapes in 21st Century Beirut”. Master of Urban Planning and Policy, American University of Beirut (unpublished).

- Makhzoumi, 1997 J. Makhzoumi The changing role of rural landscapes: olive and carob multi-use tree plantations in the semiarid Mediterranean. Landscape and Urban Planning, 37 (1997), pp. 115-122

- Makhzoumi, 2011 J. Makhzoumi Colonizing mountain, paving sea: Neoliberal politics and the right to landscape in Lebanon. S. Egoz, J. Makhzoumi, G. Pungetti (Eds.), The Right to Landscape: Contesting Landscape and Human Rights, Ashgate, London (2011), pp. 227-242

- Makhzoumi, 2000 J. Makhzoumi Landscape ecology as a foundation for landscape architecture: applications in Malta. Landscape and Urban Planning, 50 (1& 3) (2000), pp. 167-177

- Makhzoumi and Pungetti, 2008 J. Makhzoumi, G. Pungetti Landscape Strategies. I. Vogiatzakis, G. Pungetti, A. Mannion (Eds.), Mediterranean Island Landscapes, Springer-Verlag (2008), pp. 351-375

- Makhzoumi and Pungetti, 1999 J. Makhzoumi, G. Pungetti Ecological Design and Planning: the Mediterranean context. E. & F. N Spon, Routledge, London (1999)

- Makhzoumi et al., 2012 Makhzoumi, J., Talhouk, S.N., Zurayk, R. and Sadek, R. 2012. “Landscape Approach to Bio-Cultural Diversity Conservation in Rural Lebanon”. In J Tiefenbacher (ed.) Nature Conservation: Patterns, Pressures and Prospects. Released online http://www.intechopen.com/articles/show/title/landscape-approach-to-bio-cultural-diversity-conservation-in-rural-lebanon/.

- Mehdi, 2004 Mehdi, S., 2004. “Coastal Area Management Programme” CAMP Lebanon – Damour. (http://www.pap-thecoastcentre.org/pdfs/DAMOUR%20ENGLISH%20REPORT.pdf/15/03/2012).

- Moore and Margaret, 2005 A. Moore, A. Margaret Invertebrate biodiversity in agricultural and urban headwater streams: implications for conservation and management. Ecological Applications, 15 (2005), pp. 1169-1177

- Myers et al., 2010 N. Myers, R.A. Mittermeier, C.G. Mittermeier, G.A.B. Da Fonseca, J. Kent Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, 403 (2010), pp. 853-858

- Nader and Talhouk, 2002 Nader M. and Talhouk S.N., 2002.“Project for the preparation of a Strategic Action Plan for the conservation of biological Diversity in the Mediterranean Region”. Lebanon National Report. (http://www.moe.gov.lb/pdf/Biodiversity/Project%20for%20the%20preparation%20of%20a%20Strategic%20Action%20Plan.pdf/15/03/2012).

- Naveh, 2008 Z. Naveh Forward. I. Vogiatzakis, G. Pungetti, A. Mannion (Eds.), Mediterranean Island Landscapes, Springer-Verlag (2008), pp. 9-11

- Naveh, 1994 Z. Naveh From biodiversity to ecodiversity: a landscape-ecology approach to conservation and restoration. Restoration Ecology, 2 (3) (1994), pp. 180-189

- Nasr, 2004 J. Nasr Introduction. J. Nasr, M. Padilla (Eds.), Interfaces: Agricultures et villes à l’Est et au Sud de la Méditerranée, Delta, Beirut (2004)

- Paolinelli, 2002 Paolinelli G., 2002. “Territorial landscape quality and ecological links in the reorganization of urban and suburban open spaces in Valdinievole in Tuscany”. Newsletter 6, Planning in Ecological Network, Planeco Project. University of L’Aquila, Italy (http://www.planeco.org/planeco/newsletters/pdf/newsletter6.pdf/14/03/2012).

- Sorace, 2001 A. Sorace Value to wildlife of urban-agricultural parks: a case study from Rome urban area. Environmental Management, 28 (4) (2001), pp. 547-560

- Talhouk et al., 2005a S.N. Talhouk, P. Van Breugel, R. Zurayk, A. Al-Khatib, J. Estephan, A. Ghalayini, N. Debian, D. Lychaa “Status and prospects for the conservation of remnant semi-natural carob Ceratoniasiliqua L. populations in Lebanon”. Forest Ecology and Management, 206 (2005), pp. 49-59

- Talhouk et al., 2005b S.N. Talhouk, M. Dardas, M. Dagher, C. Clubbe, S. Jury, R. Zurayk, M. Maunder “Patterns of floristic diversity in semi-natural coastal vegetation of Lebanon and implications for conservation”. Biodiversity and Conservation, 14 (2005), pp. 903-915

- Zasada et al., 2010 Zasada I., Berges R.,Piorr A.,Schelafke N.,Werner A., Toussaint V.,Muller K., 2010. “Modeling approach for response functions on agricultural production, ecological regulation and recreation function. Peri-urban land use relationships – strategies and sustainability assessment tools for urban-rural linkages, integrated project” (http://www.z2.zalf.de/oa/562efdfc-e7ee-45cd-84f9-b8782855a067.pdf/14/03/2012).

- Zahreddine et al., 2004 H. Zahreddine, C. Clubbe, R. Baalbaki, A. Ghalayini, N.S. Talhouk Status of native species in threatened Mediterranean habitats: the case of Pancratium maritimum L. (sea daffodil) in Lebanon. Biological Conservation, 120 (2004), pp. 11-18

- Zeder and Sabloff, 2008 M. Zeder, J. Sabloff Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: origins, diffusion, and impact. PNAS, 105 (33) (2008), pp. 11597-11604