The dynamics and sustainability of Ambon’s smoked tuna trade

Southern Cross University, Lismore, Australia phayward2010@gmail.com

Pattimura University, Ambon, Indonesia

Abstract

This article analyses the contemporary nature of the smoked tuna (ikan asar1) trade in Ambon city (in Maluku province, eastern Indonesia) with particular regard to the operation of its central precinct along Piere Tendean Road, between the outer city suburbs of Galala and Hative Kecil, and the connection between this area and the region’s fishing grounds. The precinct is chosen as a focus since its location has been determined by a complex set of historically determined socio-political forces that are still actively in play. The article’s case study emphasises the dynamic nature of circumstances concerning the supply chain of products in locations experiencing substantial population growth, socio-cultural disruption and/or modernisation. The ‘foodways’ involved in the article’s case study are, thereby, not discrete and/or stable but, rather, volatile ones that have been variously shortcut, diverted and/or disrupted under external pressures of various degrees of magnitude and/or immediacy. The maintenance of the foodways involved has required adaptation, ingenuity and the investment of socio-cultural commitment over and above the simple inducement of commercial opportunity. The food product engendered by this dynamic system is therefore not purely a market commodity (as in a simplistic economic model) but rather a cultural one with distinct attributes and significance that crystallise the intersection of various spheres of human and environmental activity in a spatio-temporal context. In attempting to provide an analysis of Ambonese smoked tuna and its Galala–Hative Kecil precinct – and the context of the Ambonese circumstances that have delivered it – the article also reflects on the sustainability of the trade and the manner in which the dynamic development of the Ambonese population may overwhelm the adaptive potential of its entrepreneurs and patrons.

Keywords

Ambon, Smoked tuna, Foodways, Fisheries, Food heritage, Tourism, Sustainability

Introduction

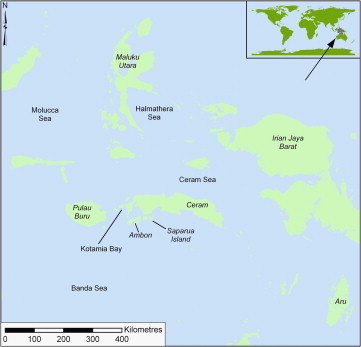

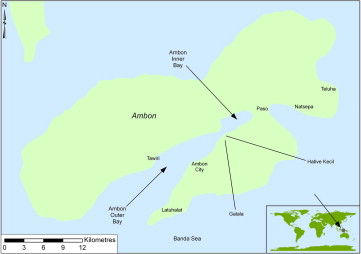

Ambon city is the administrative and economic centre of the Mauluku archipelago, which forms the eastern part of the Indonesian archipelago (see Fig. 1). The region has played a prominent part in regional and global trade networks for over a thousand years (Ellen, 2003: 4–14) through its production of the food spices obtained from clove (Syzgium aromaticum) and nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) trees and, in particular, through the high value of these products in Western Europe in the 12th–19th centuries (ibid: 5). The latter factor also resulted in the forceful intrusion of European powers into the region, with Portugal initially establishing a tenuous colonial presence in Ambon in 1526. The Netherlands displaced Portugal in 1609 and dominated Ambon and the region (albeit with brief periods of English occupation in 1796–1802 and 1810–1814) until the Japanese occupation in 1942 and Indonesian independence in the post-War era. The current population of Ambon city is around 356,000, a substantial increase on its 1980s’ population of c200,000, largely due to migration into the region from the islands of western and central Indonesia (mainly Java and Sulawesi). Along with creating environmental stress on Ambon Bay and its fishery (Fig. 2), the new arrivals significantly modified the religious demographic of the population, which was c65% Christian (a legacy of its long period of European colonisation) and c35% Muslim in the 1980s. By the end of the 1990s the ratio was closer to 50/50. Tensions between Christians and Muslims, who had lived in relative harmony for much of the preceding century, were exacerbated by the low-socio-economic status of many recent Muslim migrants, who lacked socio-economic networking and commercial opportunities on the island, and by the presence of a small number of religious fanatics amongst them. As discussed below, these tensions flared into civil war in Ambon (and in many of the other Maluku islands) in 1999–2002, resulting in widespread destruction of areas of Ambon city and outlying villages and a severe diminution of external trade with (and tourism to) the island and region in general.

From the mid 2000s on a number of central Indonesian Government and provincial initiatives attempted to restore the infrastructure of the island and to re-integrate it into the region. Since 2006 the island has seen a series of major civil works, including the construction of bridges and port facilities and commercial ventures, including high quality hotels such as the Aston, at the beachside village of Netsepa, and the Swiss Belhotel in central Ambon city. For much of the 1980s and 1990s one of the key international tourism events in the city was the annual Darwin-Ambon yacht race, which commenced in 1976 and continued until 1998 (when it was suspended due to Ambon’s political instability2).3 In 2006, as part of its attempt to revive international tourism, Ambonese representatives visited Darwin to encourage Darwin’s Dinah Beach Cruising Yacht Club Association to re-commence the race. Their mission was successful and the event was revived in 2007 and attracted increased entries in successive years. Capitalising on this modest revival in international visitation, provincial authorities announced an event entitled ‘Sail Banda’ to be held in 2010 that aimed to replace the region’s associations with religious conflict with a new set of associations, including stability, natural beauty and cultural attractions. As part of preparation for the event, the provincial authority embarked upon a series of projects designed to ‘spruce up’ the city for anticipated arrivals, including the renovation and decoration of various public areas considered to be potential tourist attractions. One aspect of this initiative was the supply of brightly coloured awnings and other apparatus for clusters of market stalls in particular areas of the island that had coalesced to supply particular food products to customers, such as (various types of) bananas at Passo, rujak (spiced fruit salad) at Netsepa and smoked tuna at Galala–Hative.

While bananas and rujak are commonly sold at stalls across the Indonesian archipelago, smoked tuna is a local Ambonese speciality with a particular commercial history and trajectory in the post-War era. Our method of examining this derives from the contemporary form of foodways research (e.g. Long, 2009; Rath and Assmann, 2010); a research field that perceives the system of production, circulation and consumption of foodstuffs as:

- culturally significant for the individuals and communities involved in various aspects of the system;

- mutable and dynamic; and

- enmeshed within intersecting realms (such as economics, politics, culture, religion, etc.).

Our approach to this involved ethnographic research along the supply chain, examination of historical records (or at least those extant after Ambon’s 1999–2001 crisis) and data collection from fieldwork. Our analysis also amplifies a growing undercurrent to foodways research, namely the issue of the bio-environmental sustainability of particular foods and foodways (and the cultural heritages and identities the latter have created). With particular regard to our address to Galala–Hative Kecil we also borrow a focus from Cultural Geography with regard to conveying and analysing the significance of specific locations within global matrices. While the road we examine is very different to and distant from Doreen Massey’s seminal object of analysis (Kilburn High Road, in London) (1991) we also approach our focal area of Piere Tendean Road with the understanding that, “what gives a place its specificity is not some long internalized history but the fact that it is constructed out of a particular constellation of social relations, meeting and weaving together at a particular [geo-temporal] locus” (Massey, 1991: 68). The context for the particular locus is, to use a termed coined by Philip Hayward, an aquapelagic one; i.e. a socio-geographic space “in which the aquatic spaces between and around a group of islands are utilised and navigated in a manner that is fundamentally interconnected with and essential to the social group’s habitation of land” (2012: 5).

The first section of this article addresses the history and contemporary operation of the fishery that supplies smoked tuna manufacturer/retailers with their ‘raw material’; the subsequent section analyses the history and current status of tuna smoking enterprises in Galala–Hative Kecil; and the Conclusion reflects on issues of heritage and sustainability.

Fishery

While the fishing fleet’s active engagement in Ambon’s smoked tuna trade ceases at the point of its sale of fish to wholesalers or, on occasion, directly to fish smokers; and while this sector only constitutes a fragment of the tuna fleet’s overall market; its operation is a vital part of Ambon’s smoked tuna ‘foodway’. Similarly, the historical changes and stresses the tuna fishery has experienced have directly effected and, indeed, largely determined, the development of the smoked food product. This section consequently provides a historical, spatial, processual and economic overview of Ambonese tuna fishing, with particular regard to the nature and supply of its product to the fish smoking sector.

While fishing of various species of tuna in the offshore waters of Ambon and adjacent islands has long been part of the general subsistence activity of the islands’ inhabitants, most commonly in the form of hand/line fishing; the development of a dedicated local tuna fishery using fishing poles and lines to generate a commercially exploitable volume of fish – and specifically skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis), known locally as cakalang; frigate mackerel (Auxis thazard thazard), known locally as komu; and yellowfin (Thunus albacares), known locally as tatihu – appears to date from the early 1950s.4 The pole and line technique was introduced to the region by Japanese fishing fleets that established themselves in the Celebes, Molucca and Banda seas from the late 1920s on, catching and processing tuna for sale in Japan, initially in the form of katsobushi (a dried tuna product that needed rehydration in soups or stews when consumed) and, by the late 1930s, in canned form (Butcher, 2004: 156–159). The Japanese fishing base in Ambon was established in 1931 and operated until the intensification of the Asia–Pacific War in 1941 and the Japanese invasion of the (then) Dutch West Indies in 1942. While the Japanese fishing fleet’s operations in the region declined during the occupation years, local folkloric accounts commonly attribute its diffusion to Ambonese fishermen to a ‘Dr. Ohara’, attached to the Japanese forces stationed in Ambon city during the wartime occupation period. The small fishing village of Galala (then several kilometres to the east of Ambon city) was the first local centre to specialise in tuna fishing, capitalising on its easy access to baitfish (primarily anchovies and sardines) in the mangrove grounds of inner Ambon Bay, to the north east of the village; to the abundant tuna fishing grounds close to the mouth of the Bay, to the south west; and to the rapidly growing urban population of Ambon city. This proximity gave the village the capacity not only to ‘day fish’ but also mount two or, on occasion, three fishing trips per boat per day. The income derived from this fishery, generated from sales directly from the landing grounds and also through stock transported to Ambon’s central fish market, ensured the village a significant degree of prosperity from the 1960s on that is commemorated in the front walls of Galala’s Presbytarian church on Piere Tendean Road, which combine Ambon’s ubiquitous nutmeg icon with an image of a tuna (Fig. 3). The income arising from the fishery allowed the local fleet to be motorised from an early stage, further enhancing the speed of the supply chain from fishery to consumer. The community’s success also spawned competition based in other ports around Ambon Bay, namely Rumahtiga, Hallong, Lateri and Poka.

The ‘day fishery’ practiced by sailing boats operating in Ambon Bay from Galala and other Bay ports continued until the early 1980s, with boats selling their catch to both papalele (female traders who retail buckets of tuna door-to-door) and retailers who ran stalls at Ambon’s central harbouside market. But the steady rise in Ambon city’s population in the 1960s and 1970s, combined with the development of its port facilities, served to undermine the Bay’s tuna fishery in two principal ways:

- pollution and destruction of the mangrove and seagrass grounds at the inner head of Ambon Bay severely depleted the availability of bait fish and required tuna boats to travel to areas of the outer Bay to obtain these prior to travelling to tuna grounds;

- insufficient local tuna stock to meet market demand required increased travel distances and times to access viable fishing grounds.

Due to these factors, the Ambonese tuna fishery underwent a process of modernisation and strategic refocusing in the 1980s that involved a switch to larger, diesel-powered fishing vessels capable of accessing more distant bait and tuna fisheries and of keeping their catch in cold stores until sufficient stock could be gained in order to ensure a satisfactory return on ship’s operating costs. As a result of this transition, the current Ambonese tuna fishery comprises around 25 boats based at Galala, at Tulehu (on the north west side of the island), at Amahusu (east coast) and at nearby Saparua island to the east. While some of the boats are individually owned, small companies owning 2 or 3 boats are increasingly prominent. Modern tuna boats have a standard design with a long front deck, including central bait holds and a larger catch hold, and an elevated bridge at the rear, used for both steerage and for fish shoal spotting (Fig. 4). The boats vary in tonnage between 25 and 40, with the tonnage being significant in that boats under 30 can be licensed in Ambon while larger boats have to be licensed in Jakarta (increasing costs and administrative difficulties for small boat owners seeking individual licensing). While tuna boats have powerful diesel engines and fuel storage tanks sufficient to sustain lengthy offshore fishing trips, their fishing methods replicate traditional artisanal practices rather than more industrialised ones. One of the first activities on current tuna fishing trips is the provision of baitfish, which are caught by being lured to the surface of the water at night by spotlights project over the boat’s prow and then are caught by being lifted in nets, a technique common across the Asia–Pacific region often referred to by its Japanese name, bouki-ami. The tuna fishing method involves spotters identifying shoals of tuna, usually by observing seagulls congregating above them, manoeuvring the fishing boat into the vicinity and luring the tuna to the front area of the boat by mimicking the appearance of a shoal of baitfish ‘boiling’ in the water. This is accomplished by firing jets of water onto the service from nozzles fixed at the front of the boat and throwing in baitfish to attract tuna. The fishing hooks on the lines attached to the bamboo poles are neither barbed nor baited, enabling the skilled fishing crew to pull the fish aboard and then flick them into the hold without the time-consuming removal and re-baiting of hooks. In addition to this practice, a smaller number of boats based at Waitatiri are involved in the net-scooping of tuna shoals, a practice that also lands immature tuna that is returned to in the conclusion to this article.

In a manner similar to fishing operations in various continents, the profits of individual fishing trips are shared between the captain and crew on a sliding scale with the former attracting around double the share of an average crewman and with the lowest percentage being awarded to bait throwers. The overall profit of individual fishing trips varies according to the volume of fish caught and its relative scarcity or abundance at the time the fish goes to market, where prices are decided by auction. The success of individual fishing boats in competition with others in Ambon, as anywhere else, relies on the skill of the captain and spotters in locating shoals, the skill of the fishermen in catching as many as possible (in the short time when they are attracted by the masquerade of boiling baitfish) and that intangible element of all fishing enterprises, good fortune.5

Research into the state of local the tuna fishery is hampered by the lack of reliable data. Indeed a recent substantial report on the state of Indonesian tuna stocks and fishing methods opened with the characterisation that:

The current understanding of information about tunas of Indonesia may be likened to a doughnut, where the tuna fisheries of the countries to the north, south, east, and west of Indonesia are relatively well-studied, while a gaping “black hole” remains in the waters of Indonesia, hindering the flow of knowledge required for effective management (World Wildlife Fund, 2008: 1)

While the section of the report on the Banda Sea region (see Fig. 1 above) ably illustrates the shortcomings of available data (2008: 66–80) and lacks data on small-scale fishing fleets (such as those discussed above (ibid: 67); it nevertheless identified an c80% decline in regional tuna catch tonnage between 2000 and 2004 (ibid).

Although hard data is limited, experienced captains and crewmembers are aware of two of the most significant aspects of the local tuna fishery over the past decade, the increased duration of sea voyages necessary to secure a large catch and the decrease in the average size of fish caught. Rather than Ambon Bay, the new target locations are substantially further from Ambon’s ports, being in Kotamia Bay, on the far (i.e. west) side of Seram island and off the south west off the coast of Buru island. Even with these new locations, there is a common local perception that the average size of skipjack caught has decreased over the last 10–15 years. While few fishermen are ready to identify over-fishing as the cause of this decline, the local fleet faces increasing competition from fishing boats operating in these locations from Bali and Manado island. In these areas, an accelerated catch – and thereby stock depletion – is being facilitated by the increasing use of a form of fish aggregation device known as rumpons (see Monintja and Mathews, 1999).6 A rumpon comprises a platform made of sago palm trunks, often with a crude shack on top to give overnight shelter to fishermen, moored to the seafloor by an anchor. Bundles of coconut palm leaves are suspended underneath the platform, facilitating the aggregation of micro-organisms and attracting baitfish that, in turn, attract tuna. There are currently 40–50 of these operating off the west coast of Seram and others scattered in other prime tuna locations in the Banda Sea around the islands of southern Maluku. Purse seine fishing has also been identified as another significant threat in South Maluku (p.c., Indonesia Tuna Commission member Mohamed Billahmar, 2011).

The majority of tuna now sold via auctions on Ambon has spent several days on ice after being caught and tends to be smaller in size than was the case in previous decades as a result of aggressive fishing practices that have reduced the number of mature adults available to be caught, meaning that many fish on sale are smaller juveniles that have barely achieved breeding age. Tuna catch is sold on a per fish basis (rather than per kilo) with fish being aggregated into approximate size ranges with appropriate pricing differentials. With particular relevance to the following section, average size skipjack (now around 2–3 k) usually fetch around 20,000 rupiah, with larger fish gaining proportionally greater prices (up to a maximum of 5 k) – although prices can virtually double at times of stock shortage. Retailers at Ambon’s central market, who buy direct from the fishing boats, charge, on average, 35,000 rupiah per 2–3 k skipjack (representing a 75% retail mark-up). These prices are most reliable in peak season (August–October), with more pronounced fluctuations due to shortages in supply liable to occur in the remainder of the year.

Galala/Hative and the smoked tuna trade

In Ambon, as in a variety of other tropical locations, fish smoking involves either split fish, or smaller whole fish, being heated on skewers over burning wood at a sufficient distance above the flames that the fish does not char and grill but rather heats and dries out, providing a ‘meatier’ pre-cooked product that has an increased shelf-life (particularly if cool stored) with a distinct smokey taste. While smoking appears to been used as a domestic preservation technique since time immemorial in Ambon, its first commercial manifestation appears to have been in the form of individual skipjack and fleet tuna smoked by papalele when their daily fresh stock could not be sold (in order to preserve their investment and produce another product variant). More concerted exploitation of smoked fish as a commodity in its own right is more recent, emerging from Galala in the 1980s, when a small number of entrepreneurs began selling smoked skipjack tuna at stalls on Piere Tendean Road and supplying some for sale in Ambon’s central fish market. Two of the earliest entrants into this market were Yanti van Kapele (whose family stall remains in the same location at Galala) and Abraham Sopacua (who now runs a stall further along the road at Hative Kecil). Given that their foray into selling this product occurred at a time when the local fleet were re-orientating to more remote fishing and the area was experiencing an economic downturn as the result of the collapse of Bay fishery, it can be seen as an entrepreneurial venture that aimed to value-add to the lesser volume of tuna being caught and thereby, at least partially, redress the negative economic impact of the stressed local fisheries. Their roadside stalls were supplied from open-fronted barbecues located within the village within a minute’s walk of the road.7 In the case of van Kapele, this is still in operation (Fig. 5) and is located on the foreshore at Galala under a large katapa tree that provides shelter from rain, close to the spot where the original Galala Bay day fishing boats would land their catch.

The smoked fish trade proved sufficiently lucrative to be continued and established a reliable clientele in the 1980s and 1990s. One factor assisting the trade was the rapid increase in local population during the 1980s and 1990s as the (formally adjacent but discrete) fishing villages of Galala and Hative Kecil found themselves absorbed into the outskirts of Ambon city and – despite increased noise and pollution – fortuitously positioned along what became the main arterial road to the outer western suburbs. While Hative Kecil did not support smoked fish stalls in the 1980s or 1990s, some smoked fish was included on sale along with fresh fish at a couple of stalls that operated some 300 m along the road from the Galala stalls. The Hative Kecil stalls sold fresh fish from the local catch adjacent to a (now-abandoned) cold store facility. The significant factor that transformed and expanded the Hative Kecil stalls (Fig. 6) into a micro-precinct for smoked fish retail was one that ably illustrates the wisdom of recent research that acknowledges those “disjunctures in communities and traditions” (Long, 2009: 9) that engender foodways. The disjuncture concerned was one that interrupted the primacy of Ambon’s central market as a fish retail centre for sufficient duration to allow Hative Kecil to capitalise by establishing product outlets and a client familiarity with their location before the central market reasserted its dominance.

In January 1999, a minor dispute between a Muslim and a Christian in Ambon city set off a number of simmering tensions8 and escalated into a riot that pitched Ambonese of differing religious persuasions against each other. Similar incidents occurred in following months throughout the region with churches, mosques and schools being stoned and/or subject to arson or bomb attacks; and with frequent acts of violence being perpetrated against individuals and communities. Conflict intensified in May when Laskar Jihad militia members from western and central Indonesia began to arrive in Ambon and Maluku to support local Muslims,9 leading to armed clashes and escalating deaths that resulted in Indonesian president Abdurrahman Wahid declaring martial law in September. Despite this declaration, conflict continued, without decisive intervention from the Indonesian military, resulting in an estimated 9000 casualties and in excess of 400,000 people being displaced across the province (Schulze, 2002: 57) until the Malino II Declaration in February 2002 put a substantial break on inter-communal friction.

The highly volatile and often violent situation in inner Ambon city substantially deterred customers from visiting the central city area (in which the central market had been wrecked), cutting them off from various food supplies and depriving market holders and primary producers of markets for their goods. As a result, both individual traders and aggregations of traders coalesced at various points on the city fringes, serving customers who could venture to these areas in (relatively) greater safety. It was at this stage that stallholders began to sell fresh fish at roadside stalls on Piere Tendean road. While the intensity of conflict in the city centre subsided by 2001, both damage to the city centre’s infrastructure and justifiable caution ensured a slow recovery for the commercial centre and provided local stallholders with an extended commercial opportunity. The situation in Ambon substantially improved from 2005 on, as the national government enforced a crackdown on religious extremists and directed the removal of Laskar Jihad members from the region. As a result, the fresh fish trade subsided, as local retailers were unable to compete with the product variety and parallel product attraction of the central market. Despite this shift in custom, one distinctive element local traders in Hative Kecil managed to retain was the retail of smoked fish. Initially a side product on fresh fish stalls, smoked tuna grew to be a principal product (by default) as fresh fish sales diminished, and were eventually discontinued. The re-focus on smoked tuna, in turn, required an increase in supply of the product and smoking ovens were established directly behind the stalls and elsewhere in the neighbourhood to supply them. The redefinition of a group of stalls at Hative Kecil as dedicated smoked tuna outlets combined with the continuing activity of the van Kapele’s Galawa stall to make the Galala–Hative area Ambon’s (only) smoked fish ‘micro-precinct’ in the mid-late 2000s.

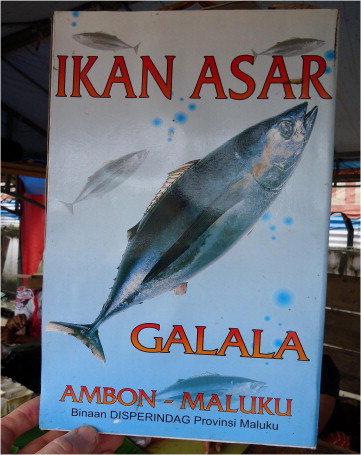

During the peak conflict years, domestic and international tourist visitation to the region all but ceased and it wasn’t until the restabilisation and revitalisation initiative commenced in 2005 that tourism began to revive. The aggregation of the smoked tuna precinct at Galala–Hative during the conflict years now proved fortuitous in that it was located on the road that all departing visitors had to travel on in order to get to Ambon airport from Ambon city. As a result, smoked tuna began to be perceived and (informally) marketed as a distinct culinary speciality of Ambon, with stallholders becoming adept at parcelling and packaging smoked tuna products so as to render them easy carry-on items for domestic Indonesian air travellers.10 The significance of the smoked tuna trade and its particular aggregation at Galala–Hative led the provincial government to endorse the micro-precinct by supplying awnings and promotional packaging (Fig. 7) in the run-up to the 2010 Sail Banda event. This promotion was a successful visual branding exercise for the precinct for visitors, attracting interest in the product, boosting sales and helping visitors promulgate the product’s identity through social networks on their return home.11 The Galala–Hative stalls’ prominence in this activity has also been aided by the lack of any dedicated local food produce stalls at Ambon city airport and, in particular, by the lack of any quality packaged smoked tuna in attractively labelled and/or vacuum-packed form that would be even more attractive and durable as a quality souvenir.

Smoked tuna’s appeal to the Ambonese repeat purchaser, particularly as a higher-cost product than fresh fish, derives from several factors. One is taste and texture, with the firm, ‘meaty’ product retaining its consistency and flavour in curries and other cooked dishes. This quality is also pertinent to its use in/as colo colo, a dish where strips of smoked tuna are dipped into sauce, traditionally a mixture of diced green and red tomatoes, chill and onions marinated in lime juice with basil (and also available with additional soy sauce) which is also on sale at many of the Galala and Hative Kecil street stalls. As the latter suggests, the combination of pre-cooked food and accompanying dip offers a timesaving dish for busy families, particularly those commuting home to the north eastern suburbs or ferrying over to the south shore of Ambon Bay. This itself is an indication of the rapid modernisation of Ambon city, including the rising cost of living and the increased aspirations of many its inhabitants that lead to dual income parental families and diminished time for domestic food preparation. The ubiquity of mobile telephony on Ambon in the early 21st century has also allowed stalls to publicise their operator’s numbers so as to allow customers to pre-order fish to be ready at particular times in order to reduce roadside waiting time and/or parking difficulties (Fig. 8).

Conclusions

During the course of a conversation with the authors conducted next to her smokery on the foreshore at Galala in August 2011, Yanti van Kapele reflected on the decline in affluence of her community since the peak period of the day fishery in the 1960s and 1970s. While acknowledging the limited income generated by smoking purchased skipjack for sale, she characterised it as an important continuation of the village’s tradition as a community defined (at least in the modern context) by its successful exploitation of tuna. Identifying herself as a tradition bearer, she expressed the necessity of passing on her smoking skills and business knowledge to young members of her family so as to ensure the continuance of that tradition. Suitably for such a tradition, the inhabitants of Galala have become traditionalists about their practice. Close to van Kapele’s open-fronted smoking oven lie abandoned and rusted box-like structures, energy-efficient closed system smoking ovens supplied to the community by the Balai Riset Industri (Research Industry Laboratory) of the Indonesian Department of Industry and Trade to modernise their practice and save fuel costs. In recent years an even more radical innovation has been proposed to and rejected by the community, the use of asap cair (aka ‘liquid smoke’). This practice substitutes hot smoking with marinating fish in coconut juice that has boiled in the nut, a process that has been proven to give fish a greater shelf life than smoking. Similarly to the closed oven technology, this practice has not been trialled, let alone introduced.

In van Kapele’s interpretation, the historical roots of Galala as a fishing community are substantially embodied and represented in the material practice of her fish smoking (despite the village’s own absorption into the outer suburbs of Ambon city). In this regard, the presence of the retail micro-precinct along the modern arterial roadway (that Piere Tendean road has itself been incorporated into) similarly constitutes an element of local identity along what is otherwise a generic commuter route. That said, the heritage invoked and sustained by the smoked tuna trade is one that has been constantly in flux within the aquapelagic context of the South Maluku region. With the advent of the commercial exploitation of the day tuna fishery beginning as recently as sixty years ago, and with the introduction of commercial tuna smoking only dating back to the 1980s, the heritage of commercial tuna exploitation goes back, at most, four generations. Indeed the community’s oldest members can recall the years before the day fishery and long before fish smoking became anything more than a domestic storage practice. While fishing is clearly a deep-rooted heritage element of the Galala–Hative community that precedes Ambon’s rapid expansion and modernisation in the post-War era, the smoked tuna trade is a heritage clearly enabled by – rather than resistant to – powerful forces of modernity, urbanity, political instability and touristification. In this sense, our analysis of the current state of smoked tuna trade in Ambon represents the most recent sequence in a fast-moving narrative that may have a dramatic denouement determined by the very energies that initially enabled it.

As previously discussed, due to over-fishing of Ambon Bay, Galala fishermen now have to ply their trade in areas far from their home waters, where they fish in competition with boats from various parts of Ambon and more distant islands, chasing tuna of decreasing sizes in dwindling shoals as FADs make the rapid location and collection of the fish more efficient. Added to these pressures is the highly aggressive practice of scooping entire pockets of tuna biomass with narrow-mesh nets carried out by the Waitatiri fleet, which is destroying the potential for tuna to breed, let alone begin to approach maturity. While skipjack is a fast-growing species that is more resilient to over-fishing than the slower maturing yellowfin, increasingly intensive fishing practices are testing this resilience. Just as the baitfish and tuna shoals of Ambon Bay were pushed to oblivion by previous generations of fishermen; the unsustainable practices of regional fishermen are in danger of rendering the abundant tuna of the South Maluku seas as much a historical memory as abundant shoals of cod are for the elders of the once lucrative Newfoundland fishery. Unhindered by regulatory frameworks and, as importantly, the lack of agencies to enforce the limited regulations and guidelines in place, the ‘success’ of the regional fishing industry may be in the eradication of its core asset. When this is achieved there may well be no skipjack for Yanti van Kapele’s descendants to smoke and the product may no longer be able to represent an earlier heritage of community success.

Research for this article was undertaken in August–September 2011. Thanks to our informants and discussants in Galala–Hatiwa Kecil and to staff at fisheries operations in other locations for their generous assistance and to Craig Proctor for identifying and supplying relevant research literature. Also thanks to Kate Barclay for her constructive critique of an earlier draft of this article.

Endnotes

References

- Bubandt, 2008 N. Bubandt Rumors, pamphlets, and the politics of paranoia in Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Studies (67) (2008), pp. 789-817

- Butcher, 2004 J. Butcher The Closing of the Frontier: A History of the Marine Fisheries of Southeast Asia, c.1850–2000. KITLV Press, Leiden (2004)

- Ellen, 2003 R. Ellen On the Edge of the Banda Zone: Past and Present in the Social Organization of a Moluccan Trading Network. University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu (2003)

- Hayward, 2012 P. Hayward Aquapelagos and Aquapelagic Assemblages. Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures, 6 (1) (2012), pp. 1-11

- Lim, 2008 J.J. Lim Jesus versus Jihad: economic shocks and religious violence in the Indonesian Republic at the turn of the twenty first century. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, 19 (3) (2008), pp. 269-303

- Long, 2009 L. Long Introduction’ (to special issue on ‘Food and Identity in the Americas’). Journal of American Folklore, 112 (483) (2009), pp. 3-10

- Massey, 1991 D. Massey A Global Sense of Space. Marxism Today (1991), pp. 24-29

- Monintja and Mathews, 1999 Monintja, D., Mathews, C., 1999. The skipjack fishery in Eastern Indonesia: distinguishing the effects of increasing effort and deploying rumpon FADs on the stock. Paper presented at Pêche Thonière et Dispositifs de Concentration de Poissons, Caribbean-Martinique (Conference), 15–19 October 1999. <http://www.archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00042/15320/> (accessed November 2011).

- Rath and Assmann, 2010 E. Rath, S. Assmann (Eds.), Japanese Foodways: Past and Present, University of Illinois Press, Champaign (2010)

- Schulze, 2002 K.E. Schulze Laskar Jihad and the conflict in Ambon. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 9 (1) (2002), pp. 57-70

- Turner, 2009 Kathleen Turner Competing Myths of Nationalist Identity: Ideological Perceptions of Conflict in Ambon. Verlag Dr Müller, Indonesia, Saarbrücken (2009)

- World Wildlife Fund, 2008 World Wildlife Fund Getting Off the Hook: Reforming the Tuna Industries of Indonesia and Considerations for Ecosystem-Based Management. World Wildlife Fund, Zeist (2008)