Negotiating Collaboration Model for the Marine Protected Area in Indonesia: The Case of Gili Balu, West Nusa Tenggara

Abstract

The Gili Balu Marine Protected Area was declared in 2021 and encompasses 5,684 hectares of ocean and eight small islands. The primary goal is to safeguard coral reefs, fish, turtles, and island ecosystems, while the secondary goal is to improve local welfare through sustainable tourism based on conservation and appropriate use of marine resources. However, until 2023, the administration of this area remained inadequate while the multiuser collaboration was still in the early stage and unbalanced in management. As a result, this research aims to develop an appropriate governance model for implementation in Gili Balu while considering the suitability and conditions of local players. The study used a series of stakeholder interviews and focused group discussions to gather actors’ opinions, which were then analyzed using Ostrom’s and Ansell and Gash’s collaborative management schemes. The study discovered that triadic collaboration is a viable model for use in this protected area, addressing three objectives: a) long-term collaboration between business, community, and government, b) effective protection of marine resources, and c) balancing social, economic, and environmental goals. This model might be used in Gili Balu to create an empowering partnership. Nonetheless, the multi-layered state-domination trend in Indonesia’s conservation remains the most significant barrier to successful and long-term co-management.

Keywords

Kenawa, community, marine conservation, collaborative, governance

Introduction

Managing marine protected areas (MPAs) around the world presents the same challenge: diverse sectors rely on coastal, marine, and terrestrial resources with varying goals (Agardy, 1994). However, most of the world’s MPAs are governed in a centralized, top-down fashion, disregarding many people’s interests and racing to achieve national targets that contradict international obligations (Junior et al., 2021). Pursuing quantitative goals frequently leads to the exclusion of quality and social fairness (de Santo, 2013). In the Caribbean, Dalton et al. (2015) discovered that MPA approaches are frequently reproduced from other locations without regard for application to local contexts where actors define MPA management differently.

The effectiveness of MPAs is determined by three indicators: biophysical, socioeconomic, and governance, with governance being the most important and demanding (Margoluis & Salafsky, 1988; Pomeroy et al., 2004; Galacher et al., 2016). The management of humans thus became crucial as Lopes et al. (2013) stated that effective governance necessitates user participation in the management structure, as their absence frequently fails marine protected area management (Lambi et al., 2012). However, some constraints appeared in MPA management as common in the least developed countries, such as Africa and Asia. A Malaysian study discovered that community participation and non-state actors are critical to efficiently administering protected areas, but inter-agency coordination and jurisdictional conflicts impede progress (Islam et al., 2017). Using West Africa as a case, the constraints are limited fisheries management, lack of financial sustainability, the disproportionate role of international NGOs and institutions, and incomplete decentralization and institutional fragmentation (Weigel et al., 2011).

MPA management in Indonesia has progressed since its inception in the Banda Sea in 1977. Despite improvements, issues persist, particularly in reconciling conservation demands with fisheries activity (KKP, 2020). According to Wiadnya et al. (2011) and Amkieltiela et al. (2022), MPA success requires significant efforts, such as increased institutional coordination, enough human and financial resources, and strengthened monitoring and evaluation. The Gili Balu Marine Tourism Park (TWP) in West Sumbawa, Indonesia, is a prime example of a conservation initiative to safeguard marine ecosystems and boost local welfare. The Gili Balu TWP covers 5,684 hectares and includes eight small islands. Its purpose is to conserve coral reefs, fish, turtles, and the entire island environment (DKP NTB, 2022). Even though numerous parties have historically used and maintained the area, the West Nusa Tenggara province government’s management is committed to long-term marine resource conservation. The project also supports activities such as fishing, nature tourism, ecotourism, and small-scale trading, all of which help to achieve conservation aims and increase local community welfare.

A common framework is required to suit all actors’ demands and serve as a conflict resolution tool between actors employing aquatic resources and ecosystems to address the diversity of actors, perspectives, and aims (Agardy et al., 2003). Three years after the Gili Balu TWP was established, the NTB province government, through the Technical Implementation Unit of the Regional Business Service Agency (BLUD), attempted to develop a partnership model incorporating formal government, community, and private sectors. A thorough evaluation was required from the start to determine the potential success of the collaboration and to establish a more extensive network of stakeholders to administer the Gili Balu TWP. As a result, this applied study began with the following question: What is the most effective governance model for the Gili Balu Marine Tourism Park to meet its core and secondary goals? Researchers expect that this study will help develop a collaborative governance model suited for the local context in Gili Balu, making government more effective and meeting the interests of numerous parties without compromising environmental quality.

2. Methods

The study was conducted in the Gili Balu TWP region and its environs as part of a more significant effort better to understand natural resource dynamics and marine protected area regulation. This study was undertaken by PT Amman Mineral Nusa Tenggara and IPB University in 2023. Interviews with actors and a critical examination of existing policies were applied. Analytical methods such as DPSIR (Hendriarianti et al., 2022), Stakeholder Analysis, and Policy Analysis are critical in mapping stakeholder perspectives and attitudes, supporting data depth, and triangulation. The findings, which will be interpretive and descriptive, will likely shed fresh light on sustainable natural resource management.

This research produces a collaborative governance paradigm with three objectives: a) develop a collaboration model between businesses, communities, and governments; b) effectively protect biodiversity and marine resources; and c) balance socioeconomic and ecological interests when implementing sustainable marine ecotourism. The evaluation process included several key elements, the first of which was a description of the area and its resources to grasp the local environment fully. Furthermore, the DPSIR analysis helps identify and evaluate the area’s influencing elements. Stakeholder analysis and engagement are essential for ensuring that all viewpoints are included in the policy review. Benchmarking with conservation area objectives establishes a standard for assessing the effectiveness of current governance, followed by a review and recommendations for improvement.

3. Results

3.1 Description of the area and the resources

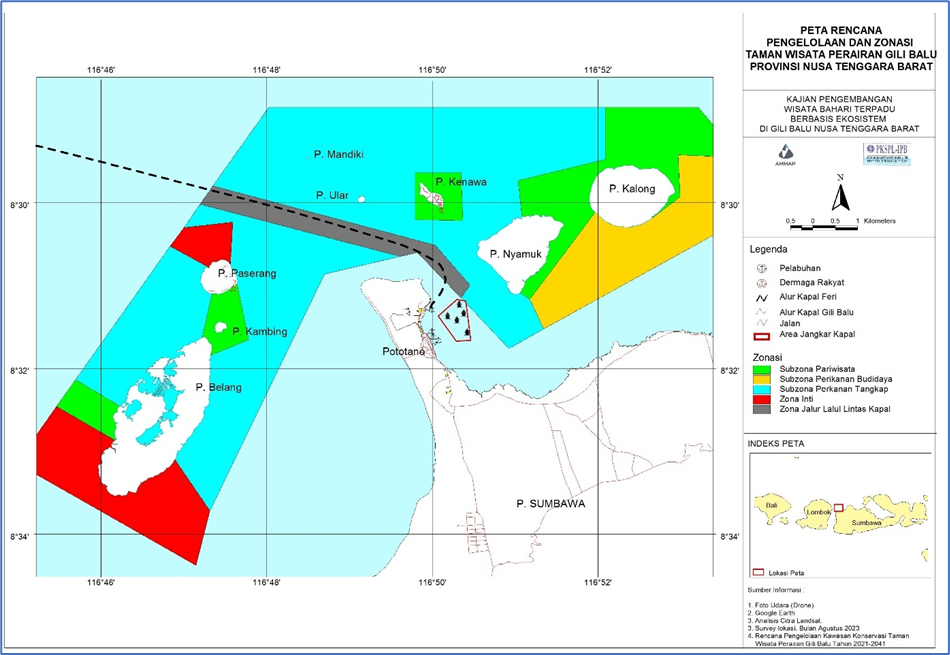

Gili Balu, located in Poto Tano Village, West Sumbawa Regency, West Nusa Tenggara Province, is a water region with high conservation and marine tourism potential. This region was designated as a Protected area in the Gili Balu Waters of West Nusa Tenggara Province in 2021 by the Minister of Marine and Fisheries’ Decree No 74 of 2021 as part of the Marine Tourism Park concept. This area comprises eight small islands: Belang, Kenawa, Paserang, Namo, Kambing, Kalong, Mandiki, and Ular (Figure 1). TWP Gili Balu has a total area of 5,845.67 hectares and is divided into three zones: a) core zone (608.69 hectares), b) limited use zone (4,947.78 hectares), and c) ferry lanes, which cover 289.20 hectares. The legislation also assigns the Regional Government of West Nusa Tenggara Province to manage the Gili Balu Marine Tourism Park (Figure 2).

The coral reef area in the Gili Balu group exemplifies the impact of marine ecosystem conservation. Coral reef ecosystems are in outstanding condition at 21.95%, with 39.02% in good condition, 36.95% in moderate condition, and 2.44% in poor condition. This area contains 44.67% hard coral cover, which is rated as moderate, and 50 coral genera. There are 229 fish species identified, representing 32 reef fish families. The seagrass area in the Gili Balu area is 130.5 hectares, which contributes to biodiversity and ecological functions in the maritime environment as a whole. Mangrove habitats in the Gili Balu area cover 604.8 hectares, providing critical habitat for various species and contributing to the general health of the marine ecosystem.

The Gili Balu area contains three ecosystems: coastal vegetation and mangroves, coral reef, and seagrass. These three ecosystems support a variety of fish, octopuses, sea cucumbers, and turtles. Trees, bushes, and lianas were the dominant species in coastal vegetation habitats. The most of plant types are classified as Fabaceae (10 species) or Asteraceae. The CITES Appendix II category includes three species: dragon fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus), Indian-fig Opuntia (Opuntia ficus-indica), and Vanda orchid (Vanda limbata). At the same time, 38 species are included in the IUCN Red List, including one in the Near Threatened category, one in the Least Concern category—Aegiceras floridum mangrove—and one in the Data Deficient category. The species diversity index (H') of coastal vegetation (mangrove and non-mangrove) in Gili Balu ranges from 0 to 1.882; in other words, it falls into the low to medium category. The density values of existing mangrove vegetation types are seedling level (none), sapling level (1,200 stems/ha), and tree level (1,600 stems/ha).

Gili Balu also has rare marine wildlife such as turtles, sharks, mantas, sea snakes, frogfish, and mantis shrimp, as well as commercially targeted fish like Mackerel tuna, Skipjack tuna, Spanish mackerel, Ray fish, Grouper, Clams, Crabs, Squid, Rabbitfish, and Octopus. This condition is caused by coral reefs, which provide life support. Hard coral cover ranges from 5% to 76%, with an average of more than 19%. This suggests that live coral cover in Gili Balu ranges from modest to good (Giyanto et al., 2017). Meanwhile, nearly all waterways surrounding the eight islands have a high soft coral cover. Gili Balu is home to a variety of coral life forms, including foliose coral (CF), branching Acropora (ACB), branching coral (CB), and rock or massive coral. These coral reefs are found at depths of 4-12 meters.

Approximately 85% of the 203 reef fish species identified were exported worldwide as decorative fish, with the remainder being target fish. According to the IUCN Red List, eight species are endemic and threatened: Apogon komodoensis, Antennarius commersoni, Plotosus lineatus (endemic), Carcharhinus limbatus (vulnerable), and Chaetodon trifascialis, Plectroglyphidodon dickii, Pomacentrus lepidogenys, and Scarus hypselopterus (near threatened).

In general, seagrass coverage ranges from 26% to 54%. Rediscovered seagrass species in Gili Balu waters include Enhalus acoroides, Thalassia hemprichii, Cymodocea rotundata, Cymodocea serrulata, Syringodium isoetifolium, Halophila ovalis, Halodule uninervis, Halodule pinifolia, and Halophila major. The average state of seagrass beds in the Gili Balu area, according to the Seagrass Ecosystem Health Index (IKEL), is moderate to poor. Small schooling fish dominated the seagrass association biota. This area’s biota includes sponges, macroalgae, Caulerpa sp., hard and soft corals, small fish, gastropods, sea cucumbers, jellyfish, starfish, and anemones. Holothuria edulis, sometimes edible sea cucumber, is a biota in short supply due to overfishing.

3.2 Risk and Response

The DPSIR analysis results show that Gili Balu is a site of high-intensity traditional fishing for fish, squid, and octopus. However, there are also damaging fishing practices that employ bombs, potassium cyanide, and coral mining. This causes significant damage to coral reefs, reduces reef fish populations, and influences the catch and income of small-scale fishers near Poto Tano Village. Destructive fishing on Gili Balu harms coral reefs, causing reef fish to relocate or disappear. Ferries frequently anchor in shallow locations with healthy coral reefs, adding to the pressure on the ecosystem. The community is applying an open-closed system for octopus fishing zones and supervising them through Pokmaswas (Community Marine Keepers) to lessen pressure. However, damaging habits continue, compounded by mounds of marine debris on beaches due to insufficient waste disposal facilities and methods. Thus, Gili Balu’s physical, chemical, and biological quality is decreasing due to household, boat, and pollution, endangering humans and marine animals. Institutional and budgetary constraints can jeopardize rehabilitation initiatives. Tourism is perceived as a solution, but if not adequately managed, it affects the ecosystem by increasing debris and water consumption, reducing reinvestment in restoration, and causing a lack of control in sensitive areas.

Unmanaged rubbish and coral reef destruction threaten Gili Balu’s waters, while seagrass and mangroves are reasonably well conserved. This damage makes it more difficult for fishers to catch fish, resulting in lower income, economic stress, a higher risk of stunting in children under five, and an increase in migrant labor, particularly among women. These repercussions have systemic effects on communities, necessitating intentional approaches to reduce the impacts and restore opportunities for families. From the actor’s perspective, there are four driving forces in the establishment and management of the Gili Balu conservation area: a) restoring the carrying capacity of the environment so that fish populations recover by delineating the area as an area of preservation that is monitored from destructive fishing activities; b) restoring fish populations so that they can continue to guarantee sustainable fisheries; and c) meeting the national target for the expansion of marine protected areas of 32.5 million hectares by 2030 as mandated by the Global Biodiversity Framework 2022; and d) creating new types of income from ecosystem services through marine tourism.

DPSIR’s investigation revealed three primary motivations for administering the Gili Balu conservation area: the company’s responsibility to promote environmental management, strengthen local institutions, and contribute to regional growth. The area was previously under intense strain from disruptive fishing and community behavior, resulting in coral reef degradation and diminishing catches. As part of the new ecotourism initiative, the land needs to be rehabilitated through community management. Thanks to the efforts of local residents, Gili Balu’s waters have improved to the point that it will be declared a Protected Area in 2021. In around five years (2016-2021), the waters of Gili Balu transitioned from a region depleted by anthropogenic forces to a local community-managed area. However, with its designation as a Protected Area under state governance and management, collaboration with NGOs, communities, and corporations is required to make the management process more successful and advantageous to all parties (DKP NTB, 2022).

3.3 Actor and Policy Analysis

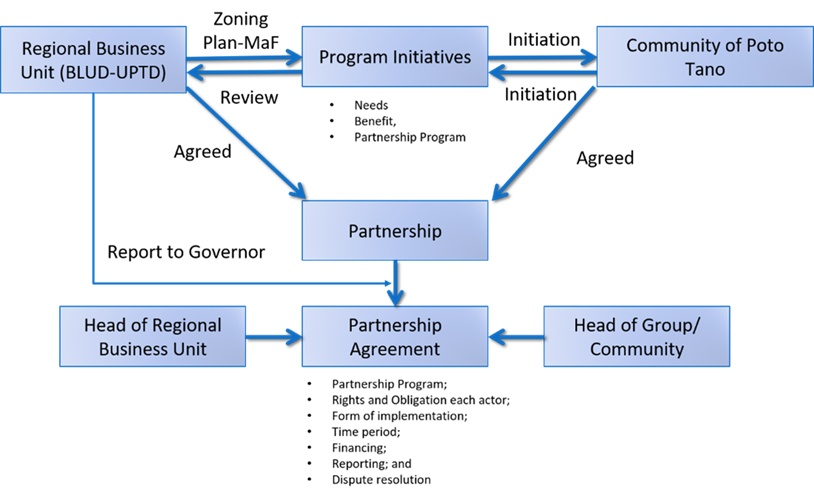

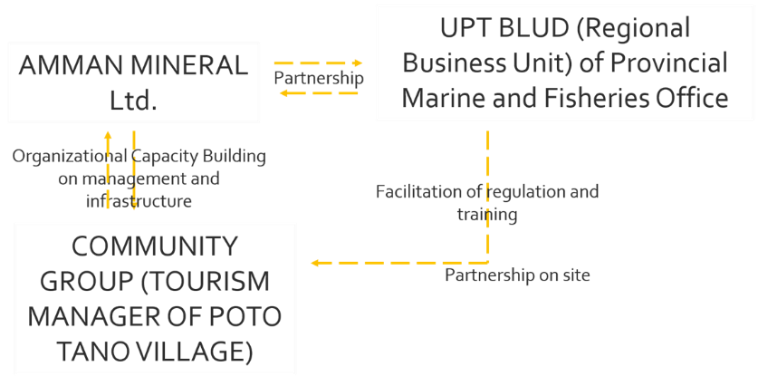

According to the requirements for managing Protected Areas in Indonesia (Permen KP No. 21/2015 on partnerships in protected area management), this possibility is realized through collaboration between the state, communities, and businesses (see Figure 5).

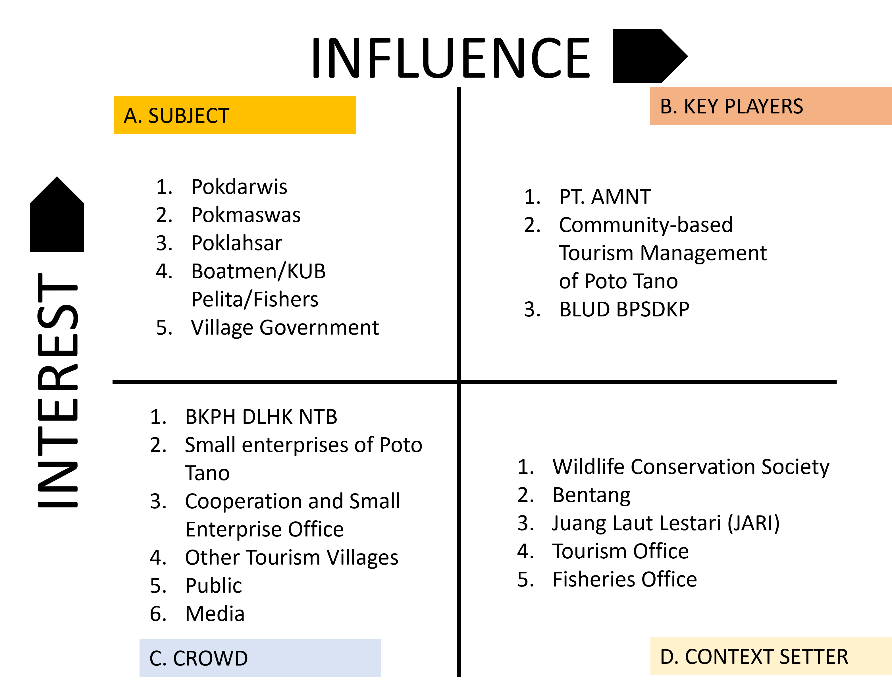

During the field study, numerous actors were identified based on their strengths, weaknesses, roles, and interests in Gili Balu tourism. An actor quadrant was created from these numerous actors to demonstrate each actor’s position and relationship with one another; the findings of this stakeholder study suggest where Collaborative Governance implementation can take place. Twelve actors have different roles and contribute to the management of the Gili Balu area (see Table 1).

| No | Actors | Roles and contributions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Village Government | It has only been active since 2022. It facilitates water protection regulations, boatmen’s contribution agreements for cleanliness, the provision of free MSMEs, and the establishment of tourism village management structures. |

| 2 | Community-based organization for tourism in Poto Tano Village | Formed in 2023, it became a tourism coordination center involving local groups such as Pokdarwis, Poklahsar, and Boatmen. |

| 3 | Community-based Tourism Groups (Pokdarwis) | Playing a role in conservation, tourism, and micro-economy since 2022, working independently without government interference. |

| 4 | Community’s Business Group (Poklahsar) | Now integrated into the Poklahsar Gili Balu Association, the women’s fish processing group produces 15 products for local and regional markets. |

| 5 | Community-based Marine Keeper (Pokmaswas) | Monitoring the area through the Gili Balu Pokmaswas Forum. Monitoring funds come from the boatmen business. |

| 6 | Boatmen/Fishers Group/KUB Pelita | The thriving fisher’s groups are becoming major tourism service providers, shuttling tourists to the islands and contributing greatly to local income. |

| 7 | Tourism Office | It has not been actively involved even though Gili Balu is listed as a strategic area in the tourism plan of West Sumbawa Regency. |

| 8 | Fisheries Office | Focus on training and equipment assistance for fishers and supporting Poklahsar with fish processing units. |

| 9 | Environmental and Forestry Office | There has been no direct intervention regarding Gili Balu, but a governance document for four islands was previously drafted. |

| 10 | Regional Service Office (BLUD) UPTD BPSDKP Sumbawa – West Sumbawa | Established as a BLUD in 2023, it is mandated to manage conservation areas with a focus on licensing, supervision, community partnerships, and awareness. |

| 11 | Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and Juang Laut Lestari (JARI) | - WCS: WCS supports conservation through snorkeling equipment, surveillance, and fisher empowerment. It is active through its partner, BENTANG. - JARI: Works with KUB Pelita, initiated an open-close system for octopus |

| 12 | PT. Amman Mineral Nusa Tenggara | Contribute through institutional capacity building, monitoring of aquatic resources, and supporting tourist park facilities as part of the social impact program. |

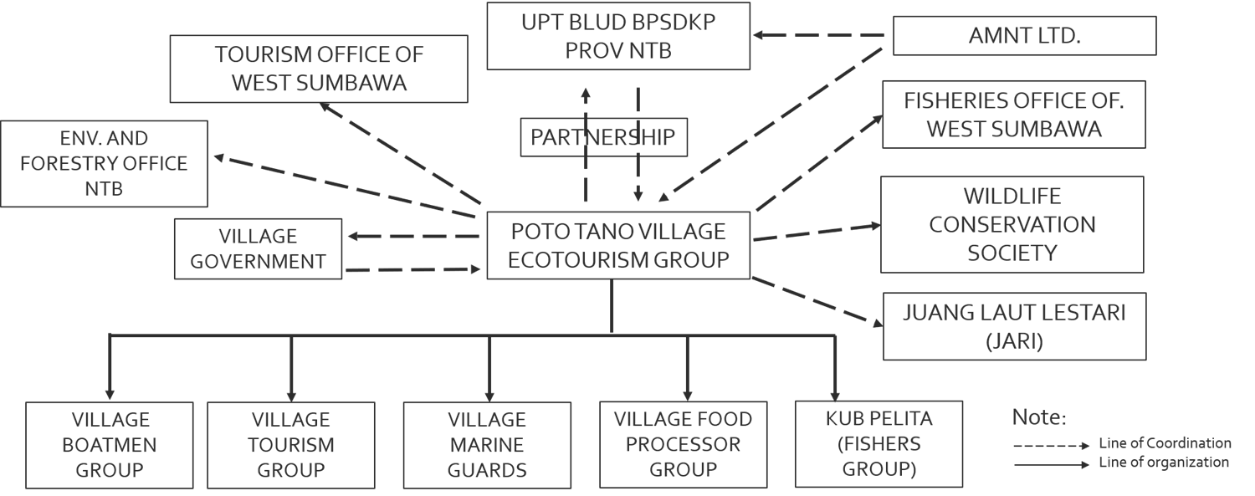

Each of the above actors has varying influence and importance in Gili Balu’s ecosystem-based marine tourism development program (see Figure 6). Actor quadrant B designates three actors as KEY PLAYERS or key actors in the program because they are deeply invested in Gili Balu: PT AMNT, the Tourism Village Manager, and BLUD BPSDKP. All three have their own formal and moral obligations to serve the public. The three roles should not be diminished because doing so will result in an imbalance in management later on. Actors in the second quadrant A will play the roles of Subjects or Actors in joint work and field operations. As indicated in the collaborative governance design above, empowerment naturally positions people and local organizations as the primary implementers.

Actors in Quadrant D provide the background for why Gili Balu tourism needs to be developed. They will serve as facilitators and supporters of the Subject to manage Gili Balu and promote overall well-being. This actor also provides regulatory and policy support, which, despite their low relevance, is sufficient to establish legitimacy at the local level. Quadrant C actors have a modest level of interest and influence. This implies they are more passive, waiting to see how subjects and key participants shape their ecosystems.

4. Discussion

4.1 Collaborative Governance for Gili Balu’s MPA

Collaborative governance is a key community administration and development strategy, particularly in rural areas. It emphasizes the active participation of many stakeholders in achieving common goals through transparent and inclusive processes (Noor et al., 2022). According to De Seve (2007), performance in collaborative governance may be measured using eight indicators: 1) a structured network; 2) commitment to achieving goals; 3) trust between actors; 4) target accuracy; 5) written legality for collaboration; 6) division of responsibilities and responsiveness to problems; 7) information disclosure; and 8) qualified human resources in collaboration.

Collaborative governance encourages ideals such as agreement and participation, resulting in a more effective and efficient management that reflects the interests and objectives of all parties involved without subordination or marginalization (Ostrom, 1990; Ansell & Gash, 2008). This technique also encourages local community empowerment and sustainable resource management, which can contribute to equitable and sustainable development (Emerson et al., 2011). According to Ostrom (1990), co-management of common resources is effective when it fits the eight indicators outlined in the design principles. To achieve these eight principles, actors must negotiate on balancing benefits and costs, decision-making consensus, anticipating free riders, establishing and adhering to sanctions, conflict resolution mechanisms, authority negotiation, and actor equality (Wheler et al., 2024). According to Ostrom et al. (1994), external variables such as the organization’s biophysical or material conditions and rules/norms that interact with other actors influence each actor’s rational decision-making. Finally, the actors or participants in this collaboration will assess the interaction results to determine the outcome, influencing other components of the collaboration framework (Ostrom, 2005).

According to Amsler (2016), collaborative governance is complex since it combines management, politics, and law. The framework’s legitimacy is undeniable, but it presents considerable difficulty in Indonesia, particularly in conservation (Amkieltiela et al., 2022; Syukri et al., 2023). The legislative framework established in Law No. 32 of 2024, which amended Law No. 5 of 1990 on the Conservation of Natural Resources and Ecosystems, states that conservation is the responsibility and obligation of both the government and the people. However, the phrase "and the community" does not suggest that the community has the authority to oversee these activities. Instead, the community may work with the central and regional governments, which are designated as the authoritative owners of designated conservation areas under Article 37 of Law 32/2024.

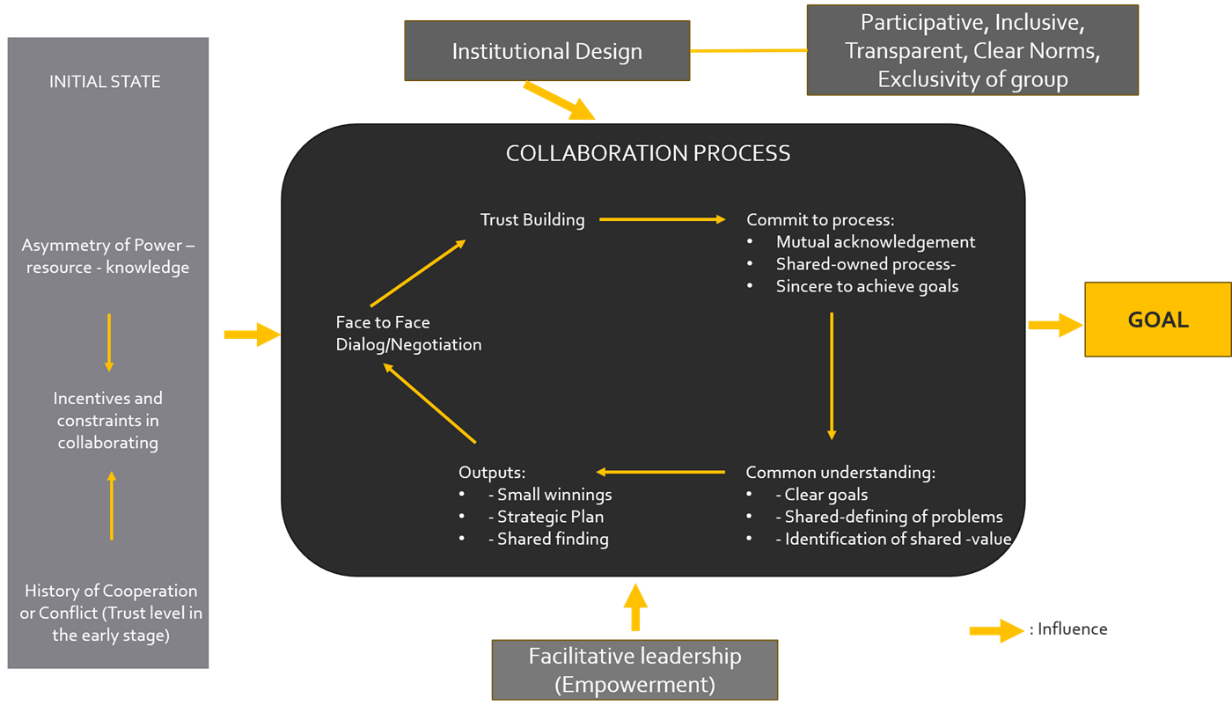

This study uses Ansell & Gash’s (2008) model because it provides a comprehensive framework for establishing effective collaboration and can be applied to Ostrom’s previously mentioned institutional framework (Bryson et al., 2015). Ansell & Gash’s (2008) sequential system comprises the following stages: 1) Understanding the context is critical for recognizing and harmonizing the perspectives of many participants, many of whom have unique histories and interests. This helps to lay a solid foundation for collaboration by ensuring that all parties have a common understanding of the goals and challenges they face; 2) The careful design of institutions allows for the establishment of explicit ground rules and cooperation mechanisms, ensuring that each contribution is valued and no member feels marginalized. The function of facilitative leadership in preserving balance and ensuring the inclusion and transparency of collaborative processes is equally important. Collaborative methods prioritizing communication and discussion can break down barriers and ease decision-making, empowering all stakeholders (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5 depicts the co-management development process, which begins by recognizing past conflict or collaboration at the site level around Gili Balu. This initial stage determines the level of trust placed in the primary actor, BLUD, by other actors, including the community. The findings of this study show a low degree of trust in BLUD due to three factors: a) BLUD’s failure to engage, b) BLUD’s financial difficulty, and c) BLUD personnel’s inability to locate, study, and monitor conservation sites. The second phase is to identify impediments and the potential for collaboration incentives. In this sense, the presence of corporate entities can improve BLUD’s inadequacies and reduce the community’s unfavorable views of the area manager (BLUD).

The next step in the investigation includes identifying inequalities between the parties concerned. Each of the three primary actors recognized as crucial roles has both strengths and shortcomings. BLUD has the legal authority to maintain the conservation area but lacks the requisite resources. The community has experience administering the region but lacks institutional power. Meanwhile, the company has significant funds despite its lack of institutional authority and experience in area management. This analysis demonstrates that all three parties understand the possibility of collaboration, each able to complement the other’s strengths and compensate for their limitations. In the setting of centrally administered common-pool resources, two patterns develop. First, the central authority would require consistent access to exact information about resource users’ adherence to the authority’s norms. Second, central authorities are expected to rely heavily on non-local specialists to provide direction and conduct most monitoring and enforcement actions (McGinnis, 2013).

The government, community, and business world initially agreed upon a triadic collaboration model. This collaboration approach was subsequently broadened by asking more actors from the site to participate in discussion forums led by the three primary actors. The subsequent phase, which forms the foundation of Gili Balu’s collaborative management framework, entails a series of face-to-face dialogues, negotiations, cooperative endeavors, resource sharing, acknowledgment, the cultivation of a shared understanding, and the development of a collaborative work plan aimed at achieving the shared goal of establishing the Gili Balu marine protected area. The entire process in this stage can be described as institutional development carried out by the three primary actors, with universities serving as empowerment facilitators who are not part of the triadic collaborative system.

Meanwhile, on a broader scale, the previously identified actors can be classified as individuals engaged in conservation regarding their significant position and influence in decision-making. Figure 7 depicts the locations and positions of each actor near the Gili Balu TWP. The actor in the center is the topic, and the actors around him are partners. The actors in the Poto Tano Village Tourism Management Group are organizations or community groups that will directly support Gili Balu’s tourism business.

Figure 7 shows that the Poto Tano Village Tourism Group is in charge of coordination and collaborative management, which includes managing other community units. The BLUD shall serve as the regulator, primary controller, and party responsible for setting service rates following applicable rules and considering the principle of community empowerment. External backers include the Village Government, Forestry Office (BKPH), Fisheries Office, Tourism Office, WCS, and JARI. They aim to empower Poto Tano Village Tourism Management through facilitation and coordination.

4.2 Supporting Policies for Partnership in Conservation

Various policies promoting sustainability and conservation have aided Gili Balu’s development as a conservation and tourism destination. Regional Law No. 12/2017 provided the legal framework for this area’s management and zoning, including the designation of conservation zones, limited-use zones, and ferry zones. Local activities and PT AMNT support have helped to boost the policy’s implementation, which has the primary goals of safeguarding biodiversity and promoting sustainable tourism. The Minister of Marine and Fisheries’ Decree No. 74 of 2021 formalized the management of this area, which comprises a protected area of 5,845.67 hectares.

At the local level, the NTB Provincial Fisheries Office and PT AMMAN MINERAL NUSA TENGGARA (PT, AMNT) have made a mutual commitment to manage Gili Balu with contributions from both parties. Specifically, PT AMNT will help to monitor fish habitats and populations, protect and rehabilitate fish habitats and populations, increase human resource capacity, provide and maintain management facilities and infrastructure, and improve area utilization services for sustainable tourism and fishing. This cooperation agreement is outlined in Partnership Agreement Numbers 253/87.2/05/Dislutkan/2022 and 274/PD-RM/AMNT/VI/2022. In order to implement this collaboration, PT AMNT tailors its scope of work to the company’s vision and strategy for the Corporate Social Impact Program.

Another strategy directly related to Gili Balu’s management is the formation of BPSDKP NTB Province as a Regional Business Service Agency (BLUD) BPSDKP starting in 2023. The Governor of West Nusa Tenggara issued Governor Regulation No. 68 of 2023, the Strategic Plan of the Regional Business Service Agency of the Technical Implementation Unit of the West Sumbawa-Sumbawa Regional Office on Marine Resources and Fisheries Management for 2024-2026. This rule was succeeded by Governor rule or Pergub No. 69/2023 on Minimum Service Standards, Pergub No. 70/2023 on BLUD Management Patterns, and Governor Decree No. 539-406/2023 on Determination of BLUD Knowledge Pattern Status. With these provincial-level decisions, BLUD can a) supervise and monitor protected areas; b) develop partnerships and empower communities; and c) increase awareness and give information on the conservation, preservation, and sustainable use of protected areas.

There are three regional policies that are sectoral in nature but related to the existence of areas around Gili Balu: the West Sumbawa Regency Tourism Development Master Plan by the Tourism Office in 2022, Siteplan for Nature Tourism Management in the Pulau Panjang Forest Group Production Forest Utilization Block RTK 73 Paserang Island BKPH Sejorong Mataiyang Brang Rea of West Sumbawa Province in 2018 by BKPH (Forestry Office), and Prioritization of West Sumbawa Capture Fish 2030 by Fisheries Office. The West Sumbawa Regency Tourism Masterplan (Riparkab) designates the Gili Balu coast as a Regency Tourism Destination (DPK) development region as well as a Regency Tourism Strategic region (KSPP). The Riparkab refers to the DPK as Poto Tano Beach, whilst the KSPP refers to Gili Balu and the Poto Tano Area. The Tourism Office will help improve the Gili Balu coastline area and Poto Tano Village regarding institutional and technical tourism guidance and create a marketing network to include Gili Balu on the national tourism agenda and route. However, before that, the Tourism Office is tasked with developing a tourism master plan in collaboration with other stakeholders because once the protected area is designated, management falls under the province’s jurisdiction rather than the regency’s.

Meanwhile, the BKPH 2018 Siteplan Document above indicates that the RTK 73 referred to in this document covers 701.26 ha of production forest on four islands: Paserang Island, Kenawa Island, Namo Island, and Belang Island. This document provides inputs following the public consultation held in West Sumbawa on the plan to develop tourism in the production forest on the four islands. This document provides some input on what can and cannot be built based on forestry regulations. The last document, the prioritization of capture fisheries, is the conceptual roadmap for the capture fisheries’ empowerment program at the regency level, including Poto Tano fishers.

The word and concept of collaborative governance mentioned above have been included in national rules as the Partnership term. The primary source is the Minister of Marine and Fisheries’ Regulation No. 21/2015 on Partnership Management of Marine Protected Areas. This rule allows government agencies that manage marine protected areas to collaborate with third parties to streamline the fulfillment of marine protected area objectives. The norm defines” partnership” as a cooperative arrangement between two or more parties founded on equality, transparency, and mutual benefit. According to the analysis, each actor has strengths and shortcomings, and the partnership serves as a tool to overcome these deficiencies. This relationship is a direct result of the Zoning Plan and Marine Protected Area Management Plan in Gili Balu TPK 2018. This is a formal relationship, as specified in the Partnership Agreement. Under the same regulations, community groups, Indigenous peoples, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), corporations, research institutes, and universities are among the entities invited to partner. The scope of the partnership can be directed at the following types of activities: monitoring of fish habitats and populations, protection and rehabilitation of fish habitats and populations, increasing human resource capacity, increasing community understanding and awareness, socioeconomic strengthening of communities around the area, provision and maintenance of area management facilities and infrastructure, increasing area supervision, development, and research.

Based on these regulations, the Poto Tano Village Tourism Management Group and corporations can become government partners, in this case, BLUD-UPTD-BPSDKP. PT AMNT, as a corporation, has established cooperation with the Marine and Fisheries Office as the parent of BLUD-UPTD-BPSDKP. Meanwhile, BLUD-UPTD has also reached a cooperation agreement with the village community. The Zoning Plan and Management Plan that has been prepared must be socialized in this partnership so that there are proposals if there are changes that include partner aspirations related to area management that will intersect with the needs, benefits, and additional programs that must be included.

4.3 The challenges and paradox in Indonesia’s MPAs

At the operational level, the goal of extending marine protected areas (MPAs) in Indonesia faces substantial challenges in implementing institutions and external influences. The primary ineffectiveness stems from two factors: the concentration of authority on the state to carry out conservation operations and a lack of knowledge, skills, and financial resources to carry out the mission of conservation-related legislation. Amkieltiela et al. (2022) have found that despite the Indonesian government’s lofty goal of expanding marine protected areas, only one-third of MPAs were effective. The study identified several key factors contributing to this situation, including ineffective management, inconsistent zoning plan formulation and implementation, weak monitoring and evaluation systems, complex coordination and communication among government agencies, a lack of collaboration with other stakeholders, and poor other conservation innovations such as OECM. Additionally, Syaprillah et al. (2023) underlined that not all modes of coastal management are just for the community, highlighting that communities continue to be marginalized in the MPA management process.

Bawole et al. (2019) identified the significant barrier to governing MPAs in Papua is the regulations and government entities at the regency, provincial, and central levels. The fundamental problem stems from these institutions’ diverse sectoral interests, frequently resulting in an unwillingness to share resources and authority. These conflicting interests come from various interpretations of legislation, resulting in a lack of cooperation between authorities and financial resources. The difficulties identified by Bawole et al. (2019) are not limited to MPA implementation in Papua; they are common in many other MPAs in Indonesia. The MPA implementations in Indonesia have significant problems due to legislation, authority, human resource capability, funds, and insufficient initiative from MPA managers (Syukri et al., 2024).

The prevailing practice in Indonesia, where the state exercises complete control over conservation activities, is a primary cause of management problems. The state is solely accountable for conservation activities (Law No. 32 of 2024, Article 4). All conservation activities by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) must be licensed or based on state initiatives. To manage each designated conservation area, the state creates an SUOP (Management Organization Unit) that follows national and regional criteria. The bureaucratic-vertical structure inherent in SUOP and the (additional) BLUD system’s responsibility for local revenue results in a one-dimensional operational framework that prioritizes the state’s or local authorities’ interests. The absence of operating finances for SUOP is the most commonly cited rationale for the continuance of multiple threats and disruptions in MPAs. Alternative methods, however, have failed to overcome the gap. In contrast, few attempts at collaboration and multi-stakeholder cooperation exist, although non-state actors may fill the gaps. Since its establishment, SUOP and BLUD, such as Gili Balu, it was very challenging to launch collaborations or partnerships due to inadequate preparation, funding, tools, and resources. Initiatives from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are facilitated through partnership schemes; however, these partners’ positions somehow are not relatively equal. The partnership’s predominant regime is “licensing” rather than “facilitation”, which impedes the implementation of co-management strategies.

The lack of clarity surrounding developing and implementing collaborative planning in Indonesia aligns with Sayer et al.’s (2008) assertion that managing a multi-user landscape is more of a negotiation process than a plan. The findings support the claim that negotiations define efforts to foster collaborative management. According to Batory & Svensson (2019), collaborative management is a fuzzy concept rarely mentioned in policy discussions, but co-management emerges in management, control, or coordination networks. However, Batory and Svensson believe that a constructive collaboration is more likely to emerge from government-led initiatives since it stems from good intentions and generates positive results. This crucial finding, however, does not appear in Indonesian MPA co-management applications, including those in Gili Balu. Bappenas and ICCTF’s evaluation found several weaknesses in the governance of stakeholders and communities in Gili Balu MPA in 2021. The coordination mechanism and active involvement of various parties were minimal, thus preventing the effectiveness of conservation area management (Bappenas and ICCTF, 2021). Similar findings were re-identified in 2023, indicating that the governance problem has not experienced significant improvement. It shows that a more comprehensive and sustainable strategy to strengthen governance capacity and increase the active participation of stakeholders in the management of the Gili Balu marine protected area is still required.

As Ansell & Gash’s scheme (2008) indicated, the collaboration in Gili Balu is still in its early stages. The BLUD has approved a cooperation request from the Poto Tano Village Tourism Management Group. This cooperation was formalized through a legal agreement: Partnership Agreement No. 800/015/BLUD BPSDKP SSB/II/2024 and No. 05/Poto Tano Village Tourism Manager/III/2024. This agreement and a collaborative work plan for tourism development and conservation in TWP Gili Balu, NTB, took effect on March 27, 2024. As the second stage of the collaborative negotiations process was initiated, efforts were made to cultivate trust and positive relationships, facilitated by the University as an external party. However, challenges emerged when opinions diverged regarding determining retribution rates. As the vertical agency overseeing the BLUD, the province sought a tariff application based on the Governor’s norms for tariff setting. However, the community expressed opposition, citing concerns regarding the profit-sharing scheme, which was perceived as potentially diminishing the community’s income. Efforts to practice conservation also experience challenges because every activity in the marine space must obtain a recommendation from the government, even for the ecosystem rehabilitation practices, represented by a letter confirming the suitability of marine space from the central government. This problem is relatively difficult to solve at the site level because the decision-making authority lies with the Ministry (central) and the Region (provincial). It is a simple example of how the government is still in full control of conservation and how the initiative from the non-state is not easy to implement.

5. Conclusions

The Triadic Collaboration is one option for launching the long-term implementation of Gili Balu’s MPA and a vehicle for fostering broader collaboration with more regional actors. When this triadic partnership strategy is used in Gili Balu’s MPA, three benefits are obtained: a) long-term collaboration between business, the community, and government, which reduces the state’s work and financial burden in managing the MPA; b) effective protection of marine resources because it is carried out intensively by the primary users of the waters; and c) balancing social-economic-environmental goals without harming the interests of one party. Collaborative governance enables each actor to participate and contribute to achieving their particular aims while maintaining the collective goal and affirmation of the empowerment mission.

Nonetheless, there are substantial obstacles to synchronizing local government and community decision-making. One of the effects of the triadic partnership is that neither party has a dominant position because the goal is to fill each deficit in each actor. However, the early implementation of collaborative management in Gili Balu is encountering a common issue, as with Indonesia’s MPAs. The state’s complete control over conservation produces an uneven structure among actors, preventing them from working together evenly and filling gaps. Thus, the concept seeks to provide a counter-discourse to traditional MPA administration, in which the state dominates or manages the area entirely. In the co-management paradigm, three key actors must agree on any management decisions. This triadic collaboration necessitates the three key entities’ commitment to respecting each other’s roles, upholding equality among parties, and maintaining the area’s main objectives: protecting aquatic biodiversity and increasing management capacity and welfare in the surrounding community.

References

- Agardy, M.T. (1994). Advances in marine conservation: the role of marine protected areas, Trends Ecol. Evol. 9 (1994) 267–270, https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(94) 90297-6.

- Agardy, T., Bridgewater, P., Crosby, M.P., Day, J., Dayton, P.K, Kenchington, R., Laffoley, D., McConney, P., Murray, P.A., Parks, J.E & Peau, L. (2003). Dangerous targets? Unresolved issues and ideological clashes around marine protected areas. Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 13: 353–367 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.583.

- Amkieltiela, Handayani, C.N., Andradi-Brown, D.A., Estradivari, Ford, A.K., Berger, M., Hakim, A., Muenzel, D.K., Carter, E., Agung, F., Veverka, L., Iqbal, N., Lazuardi, M.E., Fauzi, M.N., Tranter, S.N. & Ahmadia, G.N. (2022). The rapid expansion of Indonesia’s marine protected area requires improvement in management effectiveness. Marine Policy 146 (2022) 105257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105257.

- Amman Mineral Nusa Tenggara & Pusat Kajian Sumberdaya Pesisir dan Lautan IPB University. (2023). Laporan Kajian dan Rencana Implementasi Program Pengembangan Ekowisata (Wisata Bahari) terpadu berbasis Ekosistem di Gili Balu, Kabupaten Sumbawa Barat, NTB. 2023. (in Bahasa Indonesia/Not published)

- Amsler, L.B. (2016). Collaborative Governance: Integrating Management, Politics and Law. Public Administration Review Vol. 76, No. 5 (September/October 2016), pp. 700–711.

- Ansell, C. & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 18:543–571. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- [BAPPENAS] Badan Perencanan Pembangunan Nasional & Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund (ICCTF). (2021). Laporan Triwulan (Quarter 3 Monitoring Report). Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund (ICCTF) and Bappenas.

- Batory, A. & Svensson, S. (2019). The fuzzy concept of collaborative governance: A systematic review of the state of the art. Cent. Eur. J. Public Policy 2019; 13(2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.2478/cejpp-2019-0008.

- Bawole, R., Yulianda, F., Bengen, D.G., Fahrudin, A. & Mudjirahayu. (2011). Governability of marine protected areas: The effect of trade-offs, hybrid patterns, and policy implications in Cenderawasih Bay National Park, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 278 (2019) 012011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/278/1/012011.

- Borrini-Feyerabend G, Kothari A, & Oviedo G. (2004). Indigenous and local communities and protected areas: towards equity and enhanced conservation. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 11. IUCN, Gland Switzerland. 111 p.

- Bryson, J, M., C., B.C. & Stone, M.M. (2015). Designing and Implementing Cross-Sector Collaboration: Needed and Challenging. Public Administration Review, Vol. 75, Iss. 5, pp. 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12432.

- Dalton, T., Forrester, G. & Pollnac, R. (2015). Are Caribbean MPAs making progress toward their goals and objectives? Marine Policy 54 (2015) 69-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2014.12.009.

- de Santo, E.M. (2013). Missing marine protected area (MPA) targets: How the push for quantity over quality undermines sustainability and social justice. Journal of Environmental Management Volume 124, 30 July 2013, Pages 137-146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.01.033.

- De Seve, G.E. (2007). Creating Managed Networks as a Response to Societal Challenges. Journal Spring Providing Cutting-EDGE Knowledge to Government Leaders. The Business of Government, 45, 47–52.

- Dinas Kelautan dan Perikanan Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Barat. (2022). Rencana Pengelolaan Kawasan Konservasi Taman Wisata Perairan Gili Balu Tahun 2021-2041. Dinas Kelautan dan Perikanan Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Barat dengan dukungan Coremap-CTI (Bappenas, ADB and ICCTF). (in Bahasa Indonesia)

- Dinas Kelautan dan Perikanan Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Barat. (2022). Rencana Pengelolaan Kawasan Konservasi Taman Wisata Perairan Gili Balu Tahun 2021-2041. Dinas Kelautan dan Perikanan Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Barat dengan dukungan Coremap-CTI (Bappenas, ADB and ICCTF). (in Bahasa Indonesia)

- Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T. & Balogh, S. (2011). An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. May 2011. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur011.

- Gallacher, J., Simmonds, H., Fellowes, N., Brown, N., Gill, W. Clark, C., Biggs. & Rodwell, L.D. (2016). Evaluating the success of a marine protected area: A systematic review approach. Journal of Environmental Management (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.08.029.

- Giglio, J.V., Moura, R.L., Gibran, F.Z., Rossi, L.C., Banzato, B.M., Corsso, J.T., Pereira-Filho, G.H., & Motta, S.F. (2019). Do managers and stakeholders have congruent perceptions on marine protected area management effectiveness? Ocean and Coastal Management 179 (2019) 104865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.104865.

- Giyanto, Muhammad Abrar, Tri Aryono Hadi, Agus Budiyanto, Muhammad Hafizt, Abdullah Salatalohy, & Marindah Yulia Iswari. (2017). Status Terumbu Karang Indonesia. Jakarta: Puslit Oseanografi - LIPI. ix + 30 hlm.; 17,6 cm x 25 cm Bibliografi: hlm. 25 – 26 ISBN 978-602-6664-09-9.

- Islam, G. M.N., Tai, S.Y., Kusairi, M.N., Ahmad, S., Aswani, F.M.N., Senan, M.K.A.M., & Ahmad, A. (2017). Community perspectives on governance for effective management of marine protected areas in Malaysia. Ocean and Coastal Management 135 (2017) 34-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.11.001.

- Hendriarianti, E., Triwahyuni, A., & Ayudyaningtyas, A.T. (2022). Analisa Driving Force, Pressure, State dan Response Kualitas Air: Studi Kasus di Kabupaten Malang. Seminar Nasional METAVERSE: Peluang dan Tantangan Pendidikan Tinggi di Era Industri 5.0. ITN Malang, 13 Juli 2022.

- Junior, J.G. C. de O, Campos- Silva, J.V, & da Silva Batista, V. (2021). Linking social organization, attitudes, and stakeholder empowerment in MPA governance. Marine Policy 130 (2021) 104543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104543.

- [KKP] Kementerian Kelautan dan Perikanan (Ed.) (2020). Management of Marine Protected Areas in Indonesia: Status and Challenges (pp. 1–342). Kementerian Kelautan dan Perikanan and Yayasan WWF Indonesia. Jakarta, Indonesia. DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.13341476.

- Lambi, C.M., Kimengsi, J.N., Kometa, C.G. & Tata, E.S. (2012). The Management and Challenges of Protected Areas and the Sustenance of Local Livelihoods in Cameroon. Environment and Natural Resources Research. Vol. 2, No. 3; 2012.

- Leleu, K., Alban, F., Pelletier, D., Charbonnel, E., Letourneur, Y. & Boudouresque, C.F. (2012). Fishers’ perception as indicators of the performance of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). Marine Policy 36 (2012) 414-422. https://doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2011.06.002.

- Margoluis, C. & Salafsky, N. (1998). Measure of success: designing, managing and monitoring conservation and development projects. Island Press, Washington D.C., USA. 362.

- McGinnis, M.D. (2013). The IAD Framework in Action: Understanding the Source of the Design Principles in Elinor Ostrom’s Governing the Commons. https://ostromworkshop.indiana.edu/pdf/teaching/applying-iad-to-design-principles.pdf. Accessed January 4th, 2025.

- Noor, M.N., Suaedi, F. & Mardiyanta, A. (2022). Collaborative Governance: Suatu Tinjauan Teoritis dan Praktik. Bildung: Yogyakarta

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press: New York. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511807763.

- Ostrom, E., Gardner, R. & Walker, J. (1994). Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources. The University of Michigan Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

- Pomeroy, R.S., Parks, J.E. & Watson, L.M. (2004). How is your MPA doing? A Guidebook of Natural and Social Indicators for Evaluating Marine Protected Area Management Effectiveness. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK. xvi + 216 pp.

- Sayer, J., Maginnis, S., Buck, L. & Scherr, S. (2008). The Challenge of Assessing Progress of Landscape Initiatives. In: Learning from Landscapes, arborvitae AV Special Edition. International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Gland.

- Syaprillah, A., Zein, Y.A. & Malloy, T.H. (2023). A Social Justice Legitimacy to Protect Coastal Residents. Journal of Human Rights, Culture and Legal System Vol. 3, No. 3 November 2023. DOI: https://doi.org/10.53955/jhcls.v3i3.159.

- Syukri, M., Mawardi, M.S., Amelia, L., Asyah, A.N., & Iswara, M.A. (2024). Balancing Conservation and Community Welfare: Enhancing the Management of Marine Protected Areas in Indonesia. Research Paper No. 308, January 2024. The SMERU Research Institute, AFD, and Union Europeenne.

- Wheeler, B., Williams, O., Meakin, B., Chambers. E., Beresford, P., O’Brien, S., & Robert, B. (2024). Exploring Elinor Ostrom’s principles for collaborative group working within a user-led project: lessons from a collaboration between researcher and user-led organisation. Research Involvement and Engagement (2024) 10:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-024-00548-4

- Wiadnya, D.G.R., Syafaat, R., Susilo, E., Setyohadi, D., Arifin, Z. & Wiryawan, B. (2011). Recent Development of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in Indonesia: Policies and Governance. Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences, 1(12) 608-613, 2011

- Weigel, J.Y.; Féral, F. & Cazalet, B. (eds). (2011). Governance of marine protected areas in least-developed countries: Case studies from West Africa. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 548. Rome, FAO. 2011. 78 pp.