Choosing Island Tourist Destinations Among International Tourists: Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior

10.21463/jmic.2025.14.1.03

10.21463/jmic.2025.14.1.03

Abstract

This study applies the extended theory of planned behavior to explain the intention of international tourists to choose island tourist destinations in Vietnam. The research data were collected by a convenient sampling, with a sample size of 316 international tourists. The study employs both qualitative and quantitative research to test the research hypotheses. The results show that the intention to choose island tourist destinations in Vietnam is positively influenced by factors such as attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, sources of information, travel motivation, and destination image. Conversely, the perceived risk factor is evaluated by international tourists as negatively impacting the intention to choose island tourist destinations in Vietnam. The study proposes several managerial implications for island destinations to enhance their attractiveness and increase the intention of international tourists to choose these destinations.

Keywords

TPB, behavioral intention, island tourism, international tourists

Introduction

Customer behavior research is becoming increasingly appealing to scholars in various fields, including tourism (Ulker-Demirel & Ciftci, 2020). Understanding the decision-making process, especially destination choice, is crucial to developing marketing strategies (Lam & Hsu, 2004; Han et al., 2010). Therefore, studying behavioral intentions for destination choice has attracted the attention of many researchers worldwide (Qiu et al., 2018). In the tourism sector, applying TPB in studying tourist behavior attracts many researchers (Jordan et al., 2018). Specifically, TPB has been extensively applied in studies identifying the influence of various factors on the intention to choose tourist destinations (Nga et al., 2023). Although the usefulness of the TPB model in predicting tourist intentions has been demonstrated, many researchers emphasize that its explanatory power is still insufficient (Juschten et al., 2019). Some researchers suggest that other essential constructs related to the specific tourism context should be added to the TPB model to improve its explanatory power (Yuzhanin & Fisher, 2016).

Vietnam, located in Southeast Asia, has three sides bordering the sea, with a coastline of over 3,260 km. Vietnam’s territorial waters cover more than one million square kilometers, three times the land area. Vietnam has over 3,000 islands, including two famous archipelagos: Hoang Sa (Paracel Islands) and Truong Sa (Spratly Islands) (Xu & Thanh, 2020). Vietnam’s beaches are spread from north to south, with many beautiful beaches featuring fine sand and clear water such as Tra Co, Sam Son, Cua Lo, Cua Tung, Lang Co, My Khe, Sa Huynh, Quy Nhon, Nha Trang, Ninh Chu, Mui Ne, Long Hai, Vung Tau, Phu Quoc, etc. Along with the long coastline, Vietnam has a rich system of islands and bays with many famous landscapes such as Co To Island, Bach Long Vy, Cat Ba, Phu Quoc, and many well-known bays such as Ha Long Bay, Lan Ha Bay (Hai Phong), Xuan Dai Bay (Phu Yen), Lang Co Bay (Thua Thien Hue), and Nha Trang Bay (Khanh Hoa) (Ha, 2022). Islands and archipelagos in Vietnam are becoming ideal destinations, attracting international tourists. In addition to common tourist activities such as swimming, sightseeing, water sports, and enjoying seafood, many places have developed unique wetland tourism products to attract visitors (Thanh et al., 2022). The potential for developing island tourism in Vietnam is substantial, but the number of international tourists choosing these destinations remains limited. Promoting the intention or readiness of potential tourists to choose a destination is crucial for sustainable development (Tra et al., 2018). Thus, it is essential to study the factors influencing international tourists’ intentions to choose island destinations in Vietnam. The objective of this study is to apply the extended Theory of Planned Behavior to enhance the explanatory power regarding the intention to choose island destinations in Vietnam. Consequently, the study proposes managerial implications to increase the attractiveness and the intention of international tourists to choose these destinations.

Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

Theoretical framework

Theory of Planned Behavior

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) by Ajzen (1991) was developed and improved from the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). TPB is considered one of the most important theories in social psychology research for predicting human behavior (Dean et al., 2012). According to TPB, three factors influence the intention to perform a behavior including attitude towards the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Ajzen (1991) argued that an individual is likely to perform a specific behavior if they believe that the behavior will lead to a certain outcome that they value. Important referents approve the behavior, and they have the necessary capabilities, resources, and opportunities to perform the behavior. This theory has been used by many researchers in studies related to behavioral intentions in tourism (Joo et al., 2020; Seong & Hong, 2021; Wang et al., 2022; Le et al., 2023).

Behavioral intention

Intention plays a crucial role in predicting consumer behavior and is an important expression in the decision-making process (Bagozzi & Phillips, 1982). Ajzen (1991) found a strong connection between intention and actual behavior, making intention the best predictor of an individual’s actual behavior. Intention is directly influenced by attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 1991). Behavioral intention includes the intention to recommend to others (Twaissi & Al-Kilani, 2015; Zeithaml et al., 1996) and repurchase intention (Twaissi & Al-Kilani, 2015). Many studies have recognized behavioral intention as a mediating variable in the relationship between attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and actual behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1980; Ajzen, 1991; Lam & Hsu, 2004; Lam & Hsu, 2006). The intention to choose a destination is often defined as the degree of readiness to visit a specific destination (Chen et al., 2014).

Tourist destination

According to Rubies (2001), a tourist destination is a geographical location that includes tourism resources, attractions, infrastructure, facilities, service providers, supporting sectors, and management organizations that operate to provide tourists with the experiences they expect. Geographically, a tourist destination is a clearly defined area, such as a country, an island, or a town, where tourists can visit (Huong & Hoan, 2020). These destinations may have distinct political and legal frameworks, utilize marketing plans, and provide tourism products and services to visitors, particularly having a specific brand name (Buhalis, 2000). Tourist destinations are places that visitors visit, offering them experiences of exploring landscapes, people, or cultural elements to meet and potentially create memorable experiences (Agapito et al., 2013). Additionally, tourist destinations provide integrated tourism products and services to facilitate tourist experiences (Buhalis, 2000; Kozak, 2002; Blasco et al., 2014).

Research hypotheses

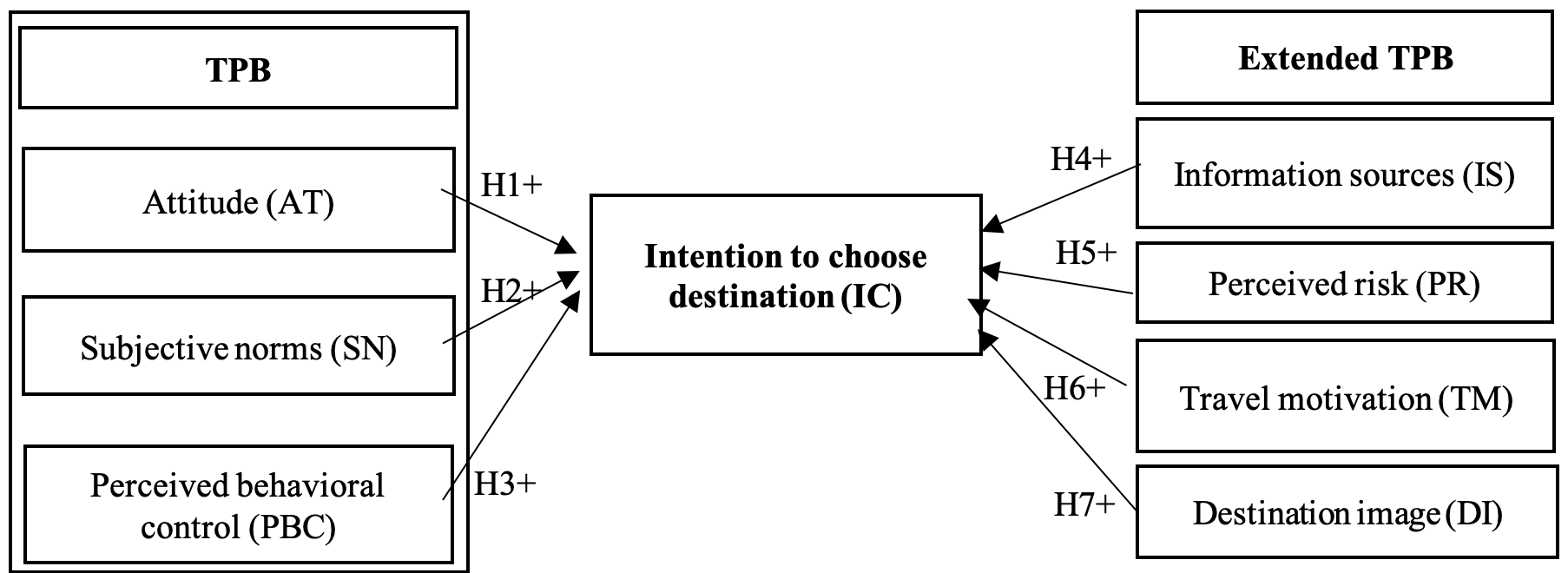

Attitude and intention to choose a destination

Attitude towards a behavior is the degree to which an individual evaluates the performance of a behavior positively or negatively (Ajzen, 1991). Attitude, once formed, persists over time and thus serves as a predictor of an individual’s behavioral intention (Hsu & Huang, 2012). A tourist’s attitude is measured through cognitive, affective, and behavioral components (Soliman, 2019). In practice, most studies on behavioral intention measure attitude primarily through the affective component (Hsu & Huang, 2012). In empirical studies, the influence of attitude on the intention to choose a tourist destination has been shown to vary significantly across different research contexts (Nga et al., 2023). However, the majority of studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between attitude and the intention to choose a tourist destination (Ghaderi et al., 2018; Soliman, 2019; Liang et al., 2019; Ahmad et al., 2020; Han et al., 2020; Hasan et al., 2020; Riestyaningrum et al., 2020; Julina et al., 2021; Chansuk et al., 2022; Lee & Hwang, 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Le et al., 2023). Therefore, the study proposes hypothesis H1: Attitude positively influences the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam.

Subjective norms and intention to choose a destination

Subjective norms refer to the perceived social pressure to perform or not perform a behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen, 1991). When family or friends have a positive attitude towards a specific action, the likelihood of an individual performing that action increases to meet their expectations and vice versa (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1980). In the context of choosing a destination, sources of information and recommendations from those around become social pressures on the behavior of choosing a tourist destination (Cao et al., 2020). Subjective norms are a crucial component that promotes the intention of tourists to choose a destination (Nga et al., 2023). Many researchers have demonstrated the positive influence of subjective norms on the intention to choose a tourist destination (Jordan et al., 2018; Halpenny et al., 2018; Ghaderi et al., 2018; Juschten et al., 2019; Ashraf et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020; Julina et al., 2021; Bayramov, 2022; Chansuk et al., 2022; Lee & Hwang, 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Le et al., 2023). Therefore, the study proposes hypothesis H2: Subjective norms positively impact the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam.

Perceived behavioral control and intention to choose a destination

Perceived behavioral control is defined as an individual’s perception of their ability to perform a specific behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Perceived behavioral control is an important factor in predicting an individual’s future behavior (Bosnjak et al., 2020). In the context of choosing a destination, perceived behavioral control relates to tourists’ perceptions of which destination meets their requirements, the opportunities to travel to that destination, and their self-confidence in the ability to travel to that destination (Jalilvand & Samiei, 2012). Several studies on tourists’ intention to choose a destination have shown that perceived behavioral control is a contributing factor to their intention to choose a destination (Joo et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022). This factor is even considered the most influential factor in the intention to choose a destination (Wang et al., 2018; Zhang & Wang, 2019; Juschten et al., 2019; Ahmad et al., 2020; Ashraf et al., 2019; Joo et al., 2020; Pahrudin et al., 2021; Seong & Hong, 2021; Ran et al., 2021; Chansuk et al., 2022; Lee & Hwang, 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Le et al., 2023). Therefore, the study proposes hypothesis H3: Perceived behavioral control positively influences the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam.

Information sources and intention to choose a destination

Tourism information sources are diverse, including social media, family information, personal experiences, websites of tourism organizations, information from the press and television, travel guidebooks, tourist blogs, etc. (Jacobsen & Munar, 2012). Tourism information sources are a crucial part of influencing tourists’ behavior before a trip, such as planning travel, booking services, and paying for products and services (Hyde, 2008). Information seeking is considered a powerful factor affecting the choice of a tourist destination (Jacobsen & Munar, 2012). Most studies have demonstrated the positive influence of information sources on tourists’ intention to choose a destination (Jacobsen & Munar, 2012; Mutinda & Mayaka, 2012; Kiráľová & Pavlíčeka, 2015; Keshavarzian & Wu, 2017; Matikiti-Manyevere & Kruger, 2019; Joo et al., 2020; Tham et al., 2020; Werenowska & Rzepka, 2020; Pan et al., 2021). Therefore, the study proposes hypothesis H4: Information sources positively affect the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam.

Perceived risk and intention to choose a destination

Perceived risk is defined as the uncertainty that customers may suffer financial, performance, social, or privacy losses when they cannot foresee the consequences of using a service (Bashir & Madhavaiah, 2015). In tourism, perceived risk is seen as tourists’ perception of the negative impact of a travel event exceeding acceptable levels during the trip (Reichel et al., 2007), such as psychological discomfort and anxiety during the purchase and consumption of certain tourism services (Huang et al., 2008). Perceived risk refers to tourists’ concerns about potential loss and adverse impacts during their travel service experience (Fuchs & Reichel, 2011). Many researchers have demonstrated the negative influence of perceived risk on tourists’ intention to choose a destination (Jensen & Svendsen, 2016; Hsieh et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2019; Yeung & Yee, 2020; Godovykh et al., 2020; Seong & Hong, 2021; Rahmafitria et al., 2021; Rather, 2021; Bayramov, 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Le et al., 2023). Therefore, the study proposes hypothesis H5: Perceived risk negatively influences the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam.

Travel motivation and intention to choose a destination

According to Colquitt et al. (2000), motivation is the brain process that provides energy leading to an individual’s behavior and is the main factor explaining individual behavior. Tourists’ motivation stems from a set of personal needs that can be satisfied by visiting a destination or experiencing an attraction (Meng et al., 2008). According to Pizam & Mansfield (1999), tourism motivation is a set of needs that drive a person to engage in tourism activities. The choice of a destination is influenced by various factors, among which tourism motivation is considered the reason guiding tourists’ actions (Mlozi et al., 2013). In empirical studies, the positive influence of tourism motivation on the intention to choose a tourist destination has been demonstrated by many researchers (Rittichainuwat et al., 2008; Huang & Hsu, 2009; Juschten et al., 2019; Soliman, 2019; He & Luo, 2020; Aridayanti et al., 2020; Kumbara et al., 2020; Chi & Phuong, 2022). Hence, the study proposes hypothesis H6: Tourism motivation positively impacts the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam.

Destination image and intention to choose a destination

Destination image is the overall perception of tourists about a destination through a process of receiving information from various sources (Beerli & Martin, 2004). The image of a tourist destination includes tourists’ comments about the destination based on their beliefs, attitudes, and viewpoints; it is a decisive factor in tourists’ behavior (Chen & Tsai, 2007). Destination image influences tourists’ subjective perceptions and behavioral intentions (Tapachai & Waryszak, 2000). A destination with a beautiful and positive image will strongly affect tourists’ future intended actions (Sönmez & Sirakaya, 2002). Most studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between destination image and tourists’ intention to choose a destination (Castro et al., 2007; Huang, 2009; Park et al., 2017; Ashraf et al., 2019; Deng et al., 2021; Ran et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Bayramov, 2022; Lee & Hwang, 2022; Le et al., 2023). The study proposes hypothesis H7: Destination image positively affects the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam.

Based on the literature review and proposed research hypotheses, the research model for factors influencing the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam is established (Figure 1) as follows:

Research Methodology

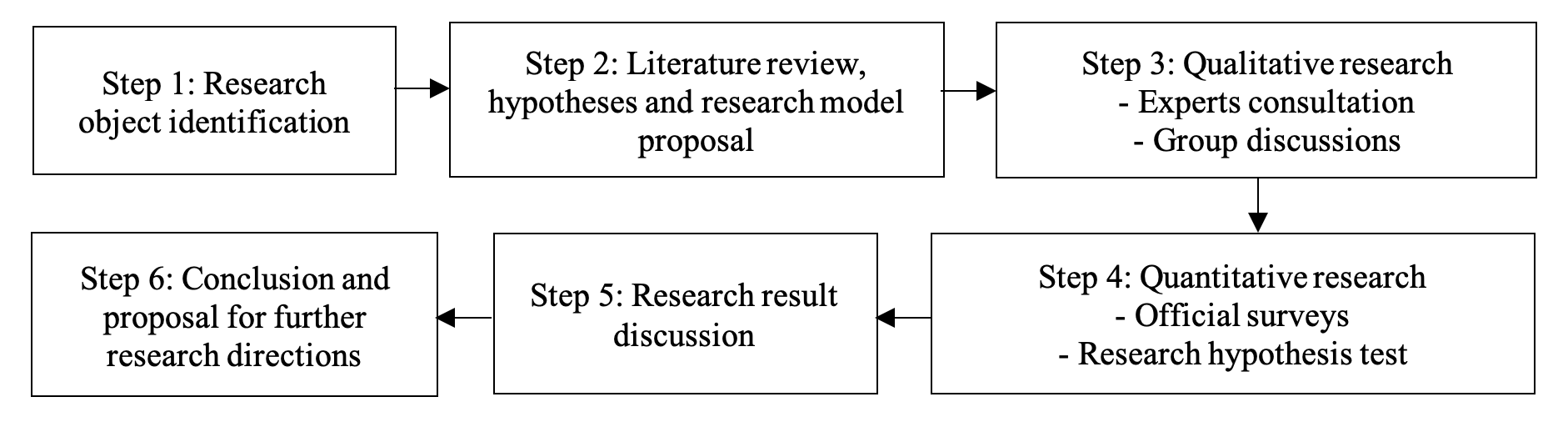

To address the research objectives, the research process is organized in the following order (Figure 2):

Step 1: In this study, the research subjects are identified as the factors influencing the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam.

Step 2: The study reviews the literature related to the Theory of Planned Behavior, behavioral intention, tourist destinations, and empirical studies related to tourists’ destination choice intentions. Based on this review, research hypotheses are developed and a research model is constructed.

Step 3: Qualitative research is used to develop the research scale. A combination of focus group discussions and expert consultations is employed to identify suitable scales for the research model. A focus group discussion is conducted with nine experienced island tourists. Simultaneously, expert consultations are conducted with four tourism experts to identify the measurement variables. The results of the focus group discussions and expert consultations lead to the adjustment and agreement on eight scales with 35 observed variables. The observed variables for each scale are derived from relevant empirical studies: The scales for attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control are adopted from the studies by Chansuk et al. (2022) and Lee & Hwang (2022); the information source scale is adopted from Jacobsen & Munar (2012) and Jalilvand & Samiei (2012); the perceived risk scale is adopted from Pappas (2021) and Seong & Hong (2021); the travel motivation scale is adopted from Mutinda & Mayaka (2012) and Mlozi et al. (2013); the destination image scale is adopted from Qu et al. (2011) and Lee & Hwang (2022); and the destination choice intention scale is adopted from Seong & Hong (2021) and Lee & Hwang (2022).

Step 4: Quantitative research is conducted to test the research hypotheses. The official quantitative research data is collected using a convenience sampling method. The survey subjects are international tourists who have experienced island tourism services at various island destinations in Vietnam. Some notable destinations selected for the survey include Dam Trau Beach (Con Dao), An Bang Beach (Hoi An), Khem Beach (Phu Quoc), My Khe Beach (Da Nang), Nha Trang Beach, Mui Ne Beach (Binh Thuan), and Vung Tau Beach (Ba Ria-Vung Tau). After excluding unsuitable survey responses (lacking reliability), a total of 316 valid survey responses are used for the official quantitative research. The main quantitative analyses used to test the hypotheses include internal consistency reliability testing using Cronbach’s alpha, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and structural equation modeling (SEM).

Step 5: Discussion of research results. Based on the hypothesis testing results, the research team conducts discussions, analyses, and comparisons with related studies to affirm the relevance and novelty of the research findings.

Step 6: Conclusion and suggestions for future research. Summarizing key findings of the study, identifying the research limitations, and proposing directions for future research to address these limitations.

Research Results and Discussion

Research sample characteristics

Based on the statistical results of the sample characteristics (Table 1), the diversity of respondents: gender, age, region of residence, and occupation. The gender structure of the respondents is relatively balanced, with male respondents accounting for 51.27% and female respondents for 47.47%. The age structure of the respondents is quite diverse, with those aged 31 to 45 accounting for the highest percentage (38.92%). The survey results show that tourists from Asia make up a significant proportion (57.59%), followed by tourists from Europe (26.58%) and the Americas (15.83%). Similar to the age structure, the occupation of respondents is diverse, with office employees accounting for the highest percentage (31.01%), followed by those working in the public sector (25.95%), freelancers (21.84%), and managers/executives (21.2%).

| Gender | Frequency | % | Region | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 162 | 51.27 | Asia | 182 | 57.59 |

| Female | 150 | 47.47 | Europe | 84 | 26.58 |

| Other | 4 | 1.26 | Americas | 50 | 15.83 |

| Age | Frequency | % | Occupation | Frequency | % |

| 16–30 | 75 | 23.73 | Manager | 67 | 21.20 |

| 31–45 | 123 | 38.92 | Officer | 98 | 31.01 |

| 46–60 | 75 | 23.73 | Public sector employee | 82 | 25.95 |

| Above 60 | 43 | 13.62 | Freelancer | 69 | 21.84 |

Test the suitability of the research model

The reliability test (Table 2) shows that Cronbach’s alpha values of all the research scales are greater than 0.6 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Additionally, all observed variables have item-total correlation values greater than 0.3 (Nunnally, 1978; Peterson, 1994; Slater, 1995). Therefore, all scales ensure internal reliability.

The EFA analysis achieved a KMO value of 0.911, indicating that it is appropriate (Hair et al., 1998). The Sig. value (Bartlett’s Test) is 0.00 < 0.5, so the observed variables involved in the analysis are correlated with each other in the overall model (Hair et al., 1998). The factor loadings of the observed variables (Table 3) are all > 0.5 (Hair et al., 1998). With Eigenvalues > 1.0 and total variance extracted > 50%. The analysis results formed 8 factors with 35 observed variables, without any variable disruption among the research scales.

| Scale | Cronbach’s alpha | Minimum corrected item-total correlation | Factor loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude (AT) | 0.881 | 0.712 | 0.589 – 0.862 |

| Subjective norms (SN) | 0.897 | 0.759 | 0.768 – 0.865 |

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC) | 0.895 | 0.755 | 0.760 – 0.863 |

| Information sources (IS) | 0.856 | 0.662 | 0.738 – 0.839 |

| Perceived risk (PR) | 0.882 | 0.700 | 0.729 – 0.896 |

| Travel motivation (TM) | 0.901 | 0.772 | 0.808 – 0.864 |

| Destination image (DI) | 0.892 | 0.589 | 0.580 – 0.858 |

| Intention to choose a destination (IC) | 0.837 | 0.632 | 0.594 – 0.742 |

Based on the CFA result in Table 3, the research model is consistent with the market data. The fit of the research model is evaluated through specific indicators as follows: χ2/df = 1.838 ≤ 2; P-value = 0.000 ≤ 0.05; TLI = 0.928 > 0.9; CFI = 0.936 > 0.9; and RMSEA = 0.052 ≤ 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Hair et al., 2014).

| Criteria | CFA result | Comparison index | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | 1.838 | ≤ 2 | Hu & Bentler (1999), Hair et al. (2014) |

| P-value | 0.000 | < 0.05 | |

| TLI | 0.928 | ≥ 0.9 | |

| CFI | 0.936 | ≥ 0.9 | |

| RMSEA | 0.052 | ≤ 0.08 |

The results of the reliability test in Table 4 show that the composite reliability (CR) of all the scales meets the requirement of ≥ 0.7 (Jöreskog, 1971). Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) of the constructs is greater than 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), indicating that the scales achieve convergent validity. Simultaneously, the square root values of the AVE are greater than the correlation values between the constructs (values off the diagonal), which shows that the scales achieve discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Thus, all the scales are suitable for the research hypothesis test.

| CR | AVE | MSV | AT | PR | SN | PBC | IS | DI | TM | IC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 0.882 | 0.652 | 0.457 | 0.807 | |||||||

| PR | 0.886 | 0.662 | 0.139 | -0.303 | 0.814 | ||||||

| SN | 0.898 | 0.688 | 0.374 | 0.531 | -0.234 | 0.829 | |||||

| PBC | 0.896 | 0.683 | 0.405 | 0.539 | -0.281 | 0.502 | 0.826 | ||||

| IS | 0.856 | 0.598 | 0.313 | 0.437 | -0.147 | 0.378 | 0.394 | 0.773 | |||

| DI | 0.894 | 0.550 | 0.447 | 0.668 | -0.320 | 0.414 | 0.449 | 0.295 | 0.742 | ||

| TM | 0.902 | 0.696 | 0.382 | 0.459 | -0.178 | 0.364 | 0.526 | 0.352 | 0.532 | 0.834 | |

| IC | 0.839 | 0.567 | 0.457 | 0.676 | -0.372 | 0.612 | 0.636 | 0.559 | 0.617 | 0.618 | 0.753 |

Test research hypotheses

In social science research, all causal relationships with a 95% confidence level are considered good (Cohen, 1988). Based on the results of the tests in Table 5, all research hypotheses are accepted at the 5% significance level. This indicates that the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam is influenced by factors such as attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, information sources, perceived risk, travel motivation, and destination image. Most factors positively impact the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam. However, perceived risk is evaluated by international tourists as negatively impacting their intention to choose island destinations in Vietnam.

| Relationship | Unstandardized | Estimate | Significance level | Hypothesis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard error S.E | Critical ratio C.R | ||||

| AT → IC | 0.151 | 0.070 | 2.146 | 0.159 | 0.032 | H1: accepted |

| SN → IC | 0.175 | 0.048 | 3.630 | 0.203 | 0.000 | H2: accepted |

| PBC → IC | 0.141 | 0.056 | 2.508 | 0.152 | 0.012 | H3: accepted |

| IS → IC | 0.280 | 0.070 | 4.017 | 0.216 | 0.000 | H4: accepted |

| PR → IC | -0.144 | 0.056 | -2.587 | -0.120 | 0.010 | H5: accepted |

| TM → IC | 0.202 | 0.055 | 3.674 | 0.217 | 0.000 | H6: accepted |

| DI → IC | 0.139 | 0.067 | 2.084 | 0.143 | 0.037 | H7: accepted |

Discussion

The research results demonstrate that the proposed model in this study aligns with Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (1991). Based on the testing outcomes in Table 5, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control positively influence the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam. In the field of tourism, this study’s findings are consistent with research proposed by Ashraf et al. (2019), Ahmad et al. (2020), Julina et al. (2021), Seong & Hong (2021), Chansuk et al. (2022), Lee & Hwang (2022), Wang et al. (2022), and Le et al. (2023). The study results indicate that among the factors in the TPB model, subjective norms are the strongest predictor of the intention to choose island destinations in Vietnam among international tourists. This finding is corroborated by studies such as Hsu & Huang (2012), Jalilvand & Samiei (2012), Meng & Choi (2016), Ashraf et al. (2019), Han et al. (2020), and Julina et al. (2021).

The research has demonstrated the positive influence of information sources on the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam. This suggests that positive information about destinations increases the intention of international tourists to choose them. Indeed, information from promotional activities and tourism promotion affects the intention to choose destinations (Pawaskar & Goel, 2016; Trivedi & Rozia, 2019). Additionally, information on social media platforms strongly influences the behavioral intention to choose destinations among international tourists (Jalilvand & Samiei, 2012; Trivedi & Rozia, 2019). These findings align with studies proposed by Jacobsen & Munar (2012), Mutinda & Mayaka (2012), Keshavarzian & Wu (2017), Joo et al. (2020), Tham et al. (2020), Werenowska & Rzepka (2020), Pan et al. (2021).

Perceived risk negatively influences the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam. This finding implies that as the perceived risk of international tourists towards these destinations increases, their intention to choose them decreases. These findings are consistent with studies proposed by Jensen & Svendsen (2016), Hsieh et al. (2016), Liang et al. (2019), Yeung & Yee (2020), Seong & Hong (2021), Rahmafitria et al. (2021), Rather (2021), Bayramov (2022), Wang et al. (2022), and Le et al. (2023). In reality, island destinations often experience extreme weather phenomena (storms, typhoons, lightning, rain, hurricanes), leading to concerns among international tourists that negatively impact their intention to choose these destinations.

The study findings also indicate that travel motivation positively impacts the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam. This underscores the importance of travel motivation in the intention to choose tourist destinations among international tourists. The research emphasizes that travel motivation directly and strongly influences the behavioral intention to choose destinations (Pawaskar & Goel, 2016). While there are few studies demonstrating the role of travel motivation in the intention to choose destinations among tourists, these findings are consistent with studies by Rittichainuwat et al. (2008), Huang & Hsu (2009), Juschten et al. (2019), Soliman (2019), He & Luo (2020), Aridayanti et al. (2020), Kumbara et al. (2020), and Chi & Phuong (2022).

The study has proven a positive relationship between destination image and the intention to choose island destinations in Vietnam. This indicates that an attractive, unique, and impressive destination image will attract the attention of international tourists, thereby enhancing their intention to choose island destinations in Vietnam. Indeed, a positive destination image influences favorability (Lin et al., 2007; Sönmez & Sirakaya, 2002) and the intention to visit destinations among tourists (Hahm et al., 2018; Tapachai & Waryszak, 2000). The study results further affirm the crucial role of destination image in the intention to choose destinations among tourists. These findings are aligned with studies proposed by Castro et al. (2007), Huang (2009), Park et al. (2017), Ashraf et al. (2019), Deng et al. (2021), Ran et al. (2021), Wang et al. (2021), Bayramov (2022), Lee & Hwang (2022), and Le et al. (2023).

Conclusion

Overall, the research results have achieved its objective of applying the extended Theory of Planned Behavior to demonstrate factors influencing the intention of international tourists to choose island destinations in Vietnam. The study has shown that factors such as attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, information sources, perceived risk, travel motivation, and destination image influence the intention to choose these destinations among international tourists. Particularly, risk perception is negatively perceived by international tourists affecting their intention to choose island destinations in Vietnam.

Theoretical implications

The study emphasizes the importance of Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (1991) in studies related to the intention to choose tourism destinations. This study applied the extended Theory of Planned Behavior to enhance the explanatory power of the intention to choose island destinations in Vietnam among international tourists. Besides attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, the intention to choose these destinations is also explained by factors such as information sources, perceived risk, travel motivation, and destination image. This highlights the need for researchers to consider expanding the Theory of Planned Behavior according to different types of tourism at various destination points to better explain tourists’ destination choices.

Managerial implications

Several managerial implications for island tourism destinations are proposed: First, the study underscores the importance of travel motivation in the intention to choose island destinations among international tourists. Therefore, understanding travel motivation can help destination managers attract international tourists from different market segments. Second, positive information sources contribute to promoting the intention to choose island destinations among international tourists. Hence, destination managers should focus on the quality of destination image promotion programs and positive communication methods on social media platforms targeting international tourists. Third, a favorable destination image enhances the intention to choose island destinations among international tourists. Therefore, destination managers should develop attractive, unique, and impressive destination images to capture the attention of international tourists. Fourth, perceived risk negatively impacts the intention to choose island destinations among international tourists. Hence, destination managers should emphasize building a safe and secure destination image. Particularly, island destinations should develop solutions to cope with extreme weather conditions to reassure international tourists.

Limitations and future research directions

The current study has some limitations that need consideration. The sample size was limited, and the convenience sampling may not provide high representativeness. Besides, the study did not address factors such as individual standards, desired distance, and past behaviors when examining the intention to choose island destinations among international tourists. Therefore, future studies should include these factors to better explain tourists’ destination choices. Additionally, future research should apply the extended Theory of Planned Behavior to different types of tourism at various destination points to enhance the model’s explanatory power.

References

- Agapito, D., Mendes, J., & Valle, P. (2013). Exploring the conceptualization of the sensory dimension of tourist experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(2), 62-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.03.001

- Ahmad, W., Kim, W. G., Anwer, Z., & Zhuang, W. (2020). Schwartz personal values, theory of planned behavior and environmental consciousness: How tourists' visiting intentions towards eco-friendly destinations are shaped? Journal of Business Research, 110, 228-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.040

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Aridayanti, D. A. N., Suryawardani, I. G. A. O., & Wiranatha, A. S. (2020). Millennial Tourists in Bali: Motivation, Satisfaction and Revisit Intention. E-Journal of Tourism, 7(1), 27-36.

- Ashraf, M. S., Hou, F., Kim, W. G., Ahmad, W., & Ashraf, R. U. (2019). Modeling tourists’ visiting intentions toward eco-friendly destinations: Implications for sustainable tourism operators. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(1), 54-71. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2350

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Phillips, L. W. (1982), Representing and testing and testing organizational theories: A holistic construal. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27, 459-489. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392322

- Bashir, I., & Madhavaiah, C. (2015). Consumer attitude and behavioral intention towards Internet banking adoption in India. Journal of Indian Business Research, 7(1), 67-102. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-02-2014-0013

- Bayramov, E. (2022). Modeling travel intention in conflict-ridden destinations: the example of Turkey, 2020–2021. Regional Statistics, 12(02), 75-94.

- Beerli, A., & Martin, J. D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 657-681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.01.010

- Blasco, D., Guia, J. & Prats, L. (2014). Tourism destination zoning in mountain regions: a consumer-based approach. Tourism Geographies, 16(3). 512–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.851267

- Bosnjak, M., Ajzen, I., & Schmidt, P. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: selected recent advances and applications. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 16(3), 352-356. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v16i3.3107

- Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Journal of Tourism Management, 21, 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00095-3

- Cao, J., Zhang, J., Wang, C., Hu, H., & Yu, P. (2020). How far is the ideal destination? Distance desire, ways to explore the antinomy of distance effects in tourist destination choice. Journal of Travel Research, 59(4), 614-630. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519844832

- Castro, C. B., Armario, E. M., & Ruiz, D. M. (2007). The influence of market heterogeneity on the relationship between a destination’s image and tourists’ future behavior. Tourism Management, 28(1), 175-187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.11.013

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Noe, R. A. (2000). Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: a meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 678.

- Chansuk, C., Arreeras, T., Chiangboon, C., Phonmakham, K., Chotikool, N., Buddee, R., ..., & Arreeras, S. (2022). Using factor analyses to understand the post-pandemic travel behavior in domestic tourism through a questionnaire survey. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 16, 100691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2022.100691

- Chen, C. F., & Tsai, D. (2007). How do destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tourism Management, 28(4), 1115-1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.07.007

- Chen, Y. C., Shang, R. A., & Li, M. J. (2014). The effects of perceived relevance of travel blogs’ content on the behavioral intention to visit a tourist destination. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 787-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.019

- Chi, N. T. K., & Phuong, V. H. (2022). Studying tourist intention on city tourism: the role of travel motivation. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(2), 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-03-2021-0042

- Dean, M., Raats, M. M., & Shepherd, R. (2012). The role of self‐identity, past behavior, and their interaction in predicting intention to purchase fresh and processed organic food. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(3), 669-688. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00796.x

- Deng, C. D., Peng, K. L., & Shen, J. H. (2021). Back to a Post-Pandemic city: the impact of media coverage on revisit intention of Macau. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 24(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2021.2002788

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Fishbein, M., & Azjen, I. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-hall.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fuchs, G., & Reichel, A. (2011). An exploratory inquiry into destination risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies of first-time vs. repeat visitors to a highly volatile destination. Tourism Management, 32(2), 266-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.01.012

- Ghaderi, Z., Hatamifar, P., & Henderson, J. C. (2018). Destination selection by smart tourists: the case of Isfahan, Iran. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(4), 385-394. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1444650

- Godovykh, M., Pizam, A., & Bahja, F. (2020). Antecedents and outcomes of health risk perceptions in tourism, following the Covid-19 pandemic. Tourism Review, 76(4), 737–748. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2020-0257

- Ha, N. T. S. (2022). Developing island tourism in Vietnam - current situation and solutions for sustainable development. Journal of Human Resources and Social Sciences, 10, 97-105.

- Hahm, J., Tasci, A. D., & Terry, D. B. (2018). Investigating the interplay among the Olympic Games image, destination image, and country image for four previous hosts. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(6), 755-771. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1421116

- Hair, J. F., Gabriel, M., & Patel, V. (2014). AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2), 44-55.

- Hair, J. F., Tatham, R. L., Anderson, R. E., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis (5th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Halpenny, E., Kono, S., & Moghimehfar, F. (2018). Predicting World Heritage site visitation intentions of North American park visitors. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 9(3), 417-437. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-10-2017-0109

- Han, H., Al-Ansi, A., Chua, B. L., Tariq, B., Radic, A., Park, S. H. (2020). The post-coronavirus world in the international tourism industry: application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to safer destination choices in the case of US outbound tourism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186485

- Han, H., Hsu, L. T. J., & Sheu, C. (2010). Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmentally friendly activities. Tourism Management, 31(3), 325-334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.03.013

- Hasan, K., Abdullah, S. K., Islam, F., & Neela, N. M. (2020). An integrated model for examining tourists’ revisit intention to beach tourism destinations. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 21(6), 716-737. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2020.1740134

- He, X., & Luo, J. M. (2020). Relationship among travel motivation, satisfaction and revisit intention of skiers: A case study on the tourists of Urumqi Silk Road Ski resort. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030056

- Hsieh, C. M., Park, S. H., & McNally, R. (2016). Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to intention to travel to Japan among Taiwanese youth: Investigating the moderating effect of past visit experience. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(5), 717-729. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1167387

- Hsu, C. H. C., & Huang, S. (2012). An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior Model for Tourists. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 36(3), 390–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348010390817

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Huang, J. H., Chuang, S. T., & Lin, Y. R. (2008). Folk religion and tourist intention avoiding tsunami-affected destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(4), 1074-1078.

- Huang, S., & Hsu, C. H. (2009). Effects of travel motivation, experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. Journal of Travel Research, 48(1), 29-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287508328793

- Huang, Y. C. (2009). Examining the antecedents of behavioral intentions in a tourism context. Texas A&M University.

- Huong, N. T. L., & Hoan, P. T. (2020). Measuring effects of Hue tourism destination’s factors on tourists’ revisit intention. Hue University Journal of Science: Economics and Development, 129(5), 41-59. https://doi.org/10.26459/hueunijed.v129i5C.5968

- Hyde, K. F. (2008). Information processing and touring planning theory. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(3), 712-731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.05.001

- Jacobsen, J. K. S., & Munar, A. M. (2012). Tourist information search and destination choice in a digital age. Tourism management perspectives, 1, 39-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2011.12.005

- Jalilvand, M. R., & Samiei, N. (2012). The impact of electronic word of mouth on a tourism destination choice: Testing the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Internet research, 22(5), 591-612. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662241211271563

- Jensen, S., & Svendsen, G. T. (2016). Social trust, safety, and the choice of tourist destination. Business and Management Horizons, 4(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.5296/bmh.v4i1.9232

- Joo, Y., Seok, H., & Nam, Y. (2020). The moderating effect of social media use on sustainable rural tourism: A theory of planned behavior model. Sustainability, 12(10), 4095. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104095

- Jordan, E. J., Bynum Boley, B., Knollenberg, W., & Kline, C. (2018). Predictors of intention to travel to Cuba across three-time horizons: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Travel Research, 57(7), 981-993. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517721370

- Jöreskog, K. G. (1971). Statistical analysis of sets of congeneric tests. Psychometrika, 36(2), 109-133. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291393

- Julina, J., Asnawi, A., & Sihombing, P. R. (2021). The antecedent of intention to visit halal tourism areas using the theory of planned behavior: the moderating effect of religiosity. Journal of Tourism Management Research, 8(2), 127-135.

- Juschten, M., Jiricka-Pürrer, A., Unbehaun, W., & Hössinger, R. (2019). The mountains are calling! An extended TPB model for understanding metropolitan residents’ intentions to visit nearby alpine destinations in summer. Tourism Management, 75, 293-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.05.014

- Keshavarzian, P., & Wu, C. L. (2017). Qualitative research on travelers' destination choice behavior. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(5), 546-556. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2128

- Kiráľová, A., & Pavlíčeka, A. (2015). Development of social media strategies in tourism destinations. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 175, 358-366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.1211

- Kozak, M. (2002). Comparative analysis of tourist motivations by nationality and destinations. Tourism Management, 23(3), 221-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00090-5

- Kumbara, V. B., Afuan, M., & Putra, R. B. (2020). Influence of motivation tourist and tourist experience interest to tourists visit back to tourism in West Sumatra: seeking novelty mediation as a variable. Dinasti International Journal of Digital Business Management, 2(1), 182-194. https://doi.org/10.31933/dijdbm.v2i1.645

- Lam, T., & Hsu, C. H. (2004). Theory of planned behavior: Potential travelers from China. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 28(4), 463-482. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348004267515

- Lam, T., & Hsu, C. H. C. (2006). Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tourism Management, 27(4), 589–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.02.003

- Le, M., Phung, D., Vu, M. Q., Diep, P., Tran, Y., & Nguyen, C. (2023). Antecedents influence choosing tourism destination post-COVID-19: Young people case. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 6(5), 2241-2256. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-04-2022-0146

- Lee, J. S. H., & Hwang, J. (2022). The Determinants of Visit Intention for Chinese Residents in Michigan, United States: An Empirical Analysis Performed Through PLS-SEM. SAGE Open, 12(3), 21582440221120389. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221120389

- Liang, L. J., Choi, H. C., Joppe, M., & Lee, W. (2019). Examining medical tourists' intention to visit a tourist destination: Application of an extended MEDTOUR scale in a cosmetic tourism context. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(6), 772-784. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2303

- Lin, C. H., Morais, D. B., Kerstetter, D. L., & Hou, J. S. (2007). Examining the role of cognitive and affective image in predicting choice across natural, developed, and theme-park destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 183-194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507304049

- Matikiti-Manyevere, R., & Kruger, M. (2019). The role of social media sites in trip planning and destination decision-making processes. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 8(5), 1-10.

- Meng, B., & Choi, K. (2016). Extending the theory of planned behavior: Testing the effects of authentic perception and environmental concerns on the slow-tourist decision-making process. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(6), 528-544. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1020773

- Meng, F., Tepanon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2008). Measuring tourist satisfaction by attribute and motivation: The case of a nature-based resort. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 14(1), 41-56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766707084218

- Mlozi, S., Pesamaa, O., & Haahti, A. (2013). Testing a model of destination attachment-Insights from tourism in Tanzania. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 19(2), 165-181. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.19.2.2

- Mutinda, R., & Mayaka, M. (2012). Application of destination choice model: Factors influencing domestic tourists destination choice among residents of Nairobi, Kenya. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1593-1597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.12.008

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw.

- Nga, V. T. Q., Nhi, M. H., & Quan, L. M. (2023). A systematic literature review of the Theory of Planned Behavior application in tourism destination behavior research. Journal of Science and Technology – The University of Danang, 21(4), 17-26.

- Pahrudin, P., Chen, C. T., & Liu, L. W. (2021). A modified Theory of Planned Behavior: A case of tourist intention to visit a destination post-pandemic COVID-19 in Indonesia. Heliyon, 7(10). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08230

- Pan, X., Rasouli, S., & Timmermans, H. (2021). Investigating tourist destination choice: Effect of destination image from social network members. Tourism Management, 83, 104217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104217

- Pappas, N. (2021). COVID-19: Holiday intentions during a pandemic. Tourism Management, 84, 104287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104287

- Park, S. H., Hsieh, C. M., & Lee, C. K. (2017). Examining Chinese college students’ intention to travel to Japan using the extended theory of planned behavior: Testing destination image and the mediating role of travel constraints. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(1), 113-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1141154

- Pawaskar, R. P., & Goel, M. (2016). Improving the efficacy of destination marketing strategies: A structural equation model for leisure travel. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 9(15), 1-11. DOI: 10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i15/92154

- Peterson, R. A. (1994). A meta-analysis of Cronbach's coefficient alpha. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(2), 381-391. https://doi.org/10.1086/209405

- Pizam, A., & Mansfeld, Y. (1999). Consumer behavior in travel and tourism. Routledge.

- Qiu, R. T., Masiero, L., & Li, G. (2018). The psychological process of travel destination choice. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(6), 691-705. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1435332

- Qu, H., Kim, L. H. & Im, H. (2011). A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tourism Management, 32(3), 465-476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.014

- Rahmafitria, F., Suryadi, K., Oktadiana, H., Putro, H. P. H., & Rosyidie, A. (2021). Applying knowledge, social concern, and perceived risk in planned behavior theory for tourism in the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Review, 76(4), 809-828. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-11-2020-0542

- Ran, L., Zhenpeng, L., Bilgihan, A., & Okumus, F. (2021). Marketing China to US travelers through electronic word-of-mouth and destination image: Taking Beijing as an example. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 27(3), 267-286. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766720987869

- Rather, R. A. (2021). Monitoring the impacts of tourism-based social media, risk perception, and fear on tourist’s attitudes and revisiting behavior in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(23), 3275-3283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1884666

- Reichel, A., Fuchs, G., & Uriely, N. (2007). Perceived risk and the non-institutionalized tourist role: The case of Israeli student ex-backpackers. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 217-226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507299580

- Riestyaningrum, F., Ferdaos, E., & Bayramov, B. (2020). Customer behavior's impact on international tourists' travel intentions due to COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism and Entrepreneurship, 1(4), 231-243. https://doi.org/10.35912/joste.v1i3.367

- Rittichainuwat, B. N., Qu, H., & Mongkhonvanit, C. (2008). Understanding the motivation of travelers on repeat visits to Thailand. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 14(1), 5-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766707084216

- Rubies, E. B. (2001). Improving public-private sectors cooperation in tourism: a new paradigm for destinations. Tourism Review, 56(3), 38-41. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb058369

- Seong, B. H., & Hong, C. Y. (2021). Does risk awareness of COVID-19 affect visits to national parks? Analyzing the tourist decision-making process using the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105081

- Slater, S. F. (1995). Issues in conducting marketing strategy research. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 3(4), 257-270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09652549500000016

- Soliman, M. (2019). Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Tourism Destination Revisit Intention. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, 22(5), 524–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2019.1692755

- Sönmez, S., & Sirakaya, E. (2002). A distorted destination image? The case of Turkey. Journal of Travel Research, 41(2), 185-196. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728702237418

- Tapachai, N., & Waryszak, R. (2000). An examination of the role of beneficial image in tourist destination selection. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 37-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003900105

- Twaissi, N. M., & Al-Kilani, M. H. (2015). The impact of perceived service quality on students’ intentions in higher education in a Jordanian Governmental University. International Business Research, 8(5), 81-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v8n5p81

- Tham, A., Mair, J., & Croy, G. (2020). Social media influence on tourists’ destination choice: Importance of context. Tourism Recreation Research, 45(2), 161-175. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1700655

- Thanh, N. T. H., Thuy, D. T., Bac, D. K., Duy, N. H., & Phuong, V. T. (2022). Tourism development in association with wetland conservation: current status and solutions for sea and islands in Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh University of Education – Journal of Science, 19(1), 147-158.

- Tra, V. T. T., Kien, D. T., & Dat, N. N. (2018). The impact of electronic word-of-mouth on Vietnamese tourists’ intention of destination choice. Journal of Economics and Development, 256, 60-71.

- Trivedi, J., & Rozia, M. I. T. A. L. I. (2019). The impact of social media communication on Indian consumers’ travel decisions. Journal of Communication: Media Watch, 18(5), 5-18.

- Ulker-Demirel, E., & Ciftci, G. (2020). A systematic literature review of the theory of planned behavior in tourism, leisure, and hospitality management research. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 43, 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.04.003

- Wang, L. H., Yeh, S. S., Chen, K. Y., & Huan, T. C. (2022). Tourists’ travel intention: Revisiting the TPB model with age and perceived risk as moderator and attitude as mediator. Tourism Review, 77(3), 877-896. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-07-2021-0334

- Wang, L., Wong, P. P. W., & Zhang, Q. (2021). Travelers’ destination choice among university students in China amid COVID-19: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Tourism Review, 76(4), 749-763. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2020-0269

- Wang, S., Wu, L., & Lee, S. (2018). Role of dispositional aspects of self-identity in the process of planned behavior of outbound travel. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 24(2), 187-199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766717695850

- Werenowska, A., & Rzepka, M. (2020). The role of social media in Generation Y travel decision-making process (case study in Poland). Information, 11(8), 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11080396

- Xu, P. H., & Thanh, V. V. (2020). Discussion on marine tourism in Vietnam at the current time. Scientific Journal of Van Lang University, 21, 37-47.

- Yeung, R. M., & Yee, W. M. (2020). Travel destination choice: does perception of food safety risk matter? British Food Journal, 122(6), 1919-1934. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-09-2018-0631

- Yuzhanin, S., & Fisher, D. (2016). The efficacy of the theory of planned behavior for predicting intentions to choose a travel destination: A review. Tourism Review, 71(2), 135-147. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-11-2015-0055

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299606000203

- Zhang, Y., & Wang, L. (2019). Influence of sustainable development by tourists’ place emotion: Analysis of the multiply mediating effect of attitude. Sustainability, 11(5), 1384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051384