Island Culture in International Relations: Tri Hita Karana and Bali’s Paradiplomacy

Abstract

This paper explores the involvement of island culture in International Relations studies, particularly with the specific study of Bali Island in Indonesia, with its unique island identity, based on Tri Hita Karana: the three causes of harmony. Three major conceptual frameworks are utilized in this paper: paradiplomacy, islandness, and the implementation of Tri Hita Karana. This paper uses descriptive qualitative methods by collecting primary data with interview with an expert informant and secondary data, by gathering relevant information from academic journals, official websites, and online news media. It suggests that the three aspects of Tri Hita Karana are being implemented in Bali’s paradiplomacy initiatives, highlighting: harmony from spiritual perspectives; harmony in strengthening people-to-people diplomacy; and harmony in preserving the environment as well as achieving sustainable development. Despite the existing challenges, Bali’s approach to paradiplomacy, shaped by Tri Hita Karana and the concept of islandness, serves as an example of how local values can guide international cooperation and connect to global collaboration.

Keywords

Bali, island culture, Indonesia, international relations, paradiplomacy, Tri Hita Karana

1. Introduction

The study of islands (island studies) has evolved as a multidisciplinary field that explores the unique characteristics of island regions, which are often geographically isolated but possess strong cultural and social distinctiveness. The concept of islandness, as discussed by Baldacchino (2008), not only refers to the geographical conditions of an island but also to the subjective perspective held by its inhabitants regarding their identity as a separate entity. Islandness encompasses the understanding of how geographical separation creates unique political, economic, and social dynamics, including interactions with the outside world.

In light of that, islands often face challenges related to resource limitations, economic dependence, and vulnerability to climate change. However, Grydehøj (2017) emphasises that islands should not be seen merely as marginal spaces but as centres of global activity capable of playing significant roles in international relations. Moreover, islands exist under diverse governance structures: some are fully independent states, while others function as subnational entities within larger countries. This makes studying islands intriguing, enabling researchers to see issues through different lenses.

An approach which we can employ is seeing island(er)s as actors that can utilise their connections with the wider world through paradiplomacy. Paradiplomacy, according to Paquin (2020), refers to diplomatic activities conducted by subnational entities such as provinces, cities, or regions, which aim to establish international relations to promote local interests. In the context of islandness, paradiplomacy becomes a crucial tool for islands to overcome their limitations, such as economic dependence on the mainland or vulnerability to environmental changes. Paradiplomacy enables islands to build cross-border cooperation focused on solutions tailored to local needs.

The relationship between islandness and paradiplomacy can be understood as the islands’ efforts to maintain their unique identity while also adopting beneficial global practices. Bartmann (2006) notes that islands are often on the cusp of paradiplomacy, where they engage in global diplomacy without being fully subject to central state authority. These islands, although under national jurisdiction, often seek international partnerships in areas such as tourism, environmental management, and the creative economy to safeguard their interests and enhance the well-being of their populations. Duchacek (1984) adds that paradiplomacy is also a form of decentralisation that gives subnational entities with some governance capacity more room to participate in international relations. Islands with strong identities often use paradiplomacy to strengthen their regional or global image, particularly by emphasising sustainable tourism and technical cooperation in the management of limited natural resources.

This paper explores the case of Bali Island, a province in Indonesia, as a prime example of an island that harnesses paradiplomacy to address its unique challenges and seize global opportunities. As one of the provinces in Indonesia, Bali operates under the state’s regulation, while standing out for its distinctive cultural identity that create memorable experiences for visitors (Listiani et al., 2024). Furthermore, Bali has earned the recognition as a world class tourist destination (Purwanto, 2017); (Lasahido & Bhwana, 2023). Over the years, Bali has used paradiplomacy to establish meaningful international partnerships, particularly in such areas as tourism, a sector for which Bali is well renowned.

What makes Bali interesting to discuss is how its sense of islandness—the strong feeling of identity shaped by its geographical isolation and rich cultural heritage—plays a central role in shaping its paradiplomacy strategies in its international relations. Bali has been long known as a culturally distinct island due to its rich history and majority of Hindu population practicing Balinese customs and traditions, in a largely Muslim country. This paper will discuss how Bali’s island culture influences the way it engages in paradiplomacy, in order to craft strategies that resonate with its local needs while appealing to global audiences.

2. Literature Review

The concept of paradiplomacy, which refers to the diplomatic activities of subnational governments engaging with international actors, has been widely explored in global contexts. Many studies have focused on the role of cities and regions in international relations, particularly within decentralised and federal systems. In Indonesia, this trend is reflected in various studies, some of which have explored Bali’s evolving role in international diplomacy through its subnational initiatives.

Intentilia & Surya Putra (2021) as well as Kencana & Elvianti (2021) explore the practice of paradiplomacy in Denpasar, Bali, through its sister city cooperation with foreign cities such as Mossel Bay, South Africa. Their research highlights how such cooperation helps to address local issues by linking Denpasar with global networks, enhancing areas like tourism, culture, and urban development. This partnership aligns with broader paradigms of paradiplomacy, where subnational entities use international cooperation to navigate globalisation and promote local interests. Those studies provide a framework for understanding Bali's paradiplomacy but focused primarily on the technical aspects of sister city cooperation rather than the island identity’s influence on this process.

Utomo (2022) investigates paradiplomacy as an outcome of state transformation under globalisation. His research provides valuable insights into how Indonesia, as a country, has adapted its foreign policy to accommodate subnational actors like Bali, thus enabling these regions to engage in international cooperation independently of the central government. In conducting paradiplomacy through sister province cooperation, the government of Bali adheres to the regulation provided by the national government. While this study offers a broader perspective on Indonesia’s paradiplomacy, it does not focus specifically on Bali’s unique positioning as an island with distinct cultural and geographical characteristics.

Covarrubias (2018) and Picard (1990) provide anthropological perspectives, discussing how Bali's unique culture and traditions have been central to its interactions with the world, particularly through cultural tourism. Although this work predates contemporary discussions of paradiplomacy, it offers a foundation for understanding how Bali has historically engaged with external actors. The emphasis on Bali’s cultural identity resonates with the concept of islandness and its role in shaping the island’s approach to diplomacy. However, this work does not directly connect these ideas to the mechanisms of modern paradiplomacy. In a more historical context, Picard (1990) also discusses Bali’s cultural performances as tourist attractions, situating them within the broader frame of cultural tourism. His work unveils how Bali's cultural identity has been commodified for international audiences, contributing to its global visibility. While this provides a critical understanding of Bali’s international image, it lacks an exploration of how these cultural elements influence the island’s paradiplomatic engagements.

Other scholars on Indonesian paradiplomacy, such as Surwandono & Maksum (2020), examine the architecture of paradiplomacy in Indonesia, providing a broader understanding of the regulatory framework that governs subnational governments' international relations. While their content analysis offers a valuable perspective on the mechanisms that facilitate paradiplomacy across Indonesia, it does not specifically address how these structures apply to islands, such as Bali. These studies provide comprehensive insights into various aspects of Bali's paradiplomacy. Yet, there remains a significant gap in the literature when it comes to examining how the concept of islandness—the unique geographical and cultural identity of Bali as an island—specifically influences its paradiplomatic strategies. Most current studies focus on technical frameworks, tourism, or cultural exchange, without delving into how Bali’s distinct island identity impacts its international relations. This paper seeks to fill that gap by analysing Bali’s paradiplomacy through the lens of islandness, offering a fresh perspective on how the island leverages its unique status in the global arena.

Bali’s existing paradiplomacy through sister province cooperation has been explored by Intentilia (2024), highlighting the element of tourism and culture as the prominent aspects enshrined in Memoranda of Understanding and Letters of Intent with various external partners. Taken together, these previous studies offer important insights into Bali’s paradiplomacy but also reveal a significant gap. While there is extensive research on Bali’s tourism, there is limited exploration of how the concept of islandness—the intersection of geography, culture, and identity—shapes its paradiplomatic strategies. Most of the existing literature focuses on the technical or structural aspects of Bali’s tourism from political economy aspects, while leaving a gap on more complex factors that stem from its status as an island. Therefore, this paper aims to highlight islandness through Bali’s culture of Tri Hita Karana (THK). Tri means three; Hita means harmony or happiness; and Karana means causes. Hence, THK means “three causes of happiness” (Wiana, 2004, p. 265). This paper examines Bali’s paradiplomacy through the lens of islandness, offering a more holistic understanding of how the island navigates global diplomacy.

3. Tri Hita Karana as Islandness

Bali has a distinct islandness concept derived from the philosophy of Tri Hita Karana (THK). THK was introduced by Dr. I Wayan Merta Suteja in 1966 during Konferensi Daerah I Badan Perjuangan Umat Hindu Bali (Regional Conference I Bali Hindu Struggle Body) organized at Dwijendra College, Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia (Putra, 2025); (Handam et al., 2024). However, the core values of THK have always been integrated with the Balinese people’s way of life since the inception of Hinduism in Bali, and continue to be promoted up to the present (Putra, 2025). This Balinese philosophical framework highlights harmonious relationships between the divine, society, and the environment, through three aspects: Parhyangan (spiritual harmony), Pawongan (social harmony), and Palemahan (environmental harmony). As a concept, Tri Hita Karana operates as a boundary that links diverse sectors such as agriculture, tourism, and governance, and facilitating cooperation among local Balinese communities and external actors (Roth & Sedana, 2015). This flexibility is what enables THK to transcend cultural, spiritual, and environmental domains, making it a powerful tool in both local and global contexts. THK has also been introduced to the global level since the period of the Minister of Tourism (2000-2004) to the United Nations World Tourism Organization in Spain, marking the global acknowledgement of THK as a key value of the society in Bali island (Kanal Bali, 2021).

THK resonates strongly with the concept of islandness, particularly as explored by scholars like Baldacchino (2008), who emphasises the unique social and environmental dynamics of island life. Islandness refers to the distinct characteristics of island communities, including their geographic isolation, intimate connection with the natural environment, and social cohesion. In Bali, THK reinforces these aspects by promoting sustainability within the island's limited ecological boundaries, encouraging a delicate balance between human activities and environmental preservation.

As an island, Bali must navigate limited resources and protect its cultures. Thus, THK provides a framework to maintain equilibrium, aligning with broader theories of Islandness that stress interdependence and environmental fragility (Baldacchino, 2008). Moreover, Foley et al. (2023) argue that islandness embodies a sense of place shaped by the physical geography of islands and the socio-cultural ties of islanders, which THK captures by emphasising harmony with the environment and social cohesion.

THK's emphasis on social harmony also mirrors the resilience often associated with island communities. On islands like Bali, interconnectedness between people, culture, and nature is essential for long-term sustainability. By highlighting these connections, THK supports the maintenance of cultural and environmental practices that are vital for the island’s resilience in the face of external pressures, such as tourism and resource commodification (Lewis & Lewis, 2009). This reflects Hall's (2012) observation that islands face distinct vulnerabilities due to their isolation, but their resilience often stems from strong community ties and an inherent understanding of the delicate balance between human activity and environmental sustainability. By fostering social harmony, THK is expected to help Balinese communities withstand the pressures of modernisation, particularly the increasing demand for land and resources by tourism, while maintaining their cultural and ecological integrity.

Furthermore, THK aligns with the notion of vulnerability and resilience in island contexts (Hall, 2012). Islands are not only vulnerable to environmental and economic pressures but also exhibit a remarkable capacity for resilience through local knowledge and cultural practices. Encontre (1999) also points out that islands often face significant economic challenges due to their heavy dependence on external markets and the lack of diverse economic activities. To address these challenges, it's crucial to strengthen local networks and foster community engagement, as these elements can help mitigate risks and build a more resilient economy. THK serves as both a cultural and governance framework that equips Balinese society with the tools to manage its natural resources sustainably, ensuring resilience against external shocks such as rapid urbanisation, climate change, and tourism development. In this way, THK is presumed to act as a safeguard for Bali's cultural and environmental heritage, which is continually threatened by these global forces.

The relationship between THK and islandness also extends to struggles over development, as explored by Stratford & Wells (2009). Their case study on Tasmania illustrates how development in island contexts often leads to conflicts between preserving local identities and pursuing economic growth. Similarly, in Bali, THK provides a cultural counter-narrative to unchecked development. It serves as a platform for local communities to contest development projects that may jeopardise Bali’s environmental balance, framing these issues not just in economic terms but in terms of cultural and spiritual harmony. THK's role as a boundary concept becomes crucial here, allowing diverse stakeholders—local communities, government agencies, and international organisations—to engage in a dialogue that bridges cultural values and modern development imperatives (Roth & Sedana, 2015).

Additionally, islandness involves a dynamic relationship between isolation and connection, both physically and metaphorically (Foley et al., 2023). THK mirrors this duality by fostering a connection between Bali's local cultural practices and global environmental discourses. For instance, while the concept of Islandness emphasizes isolation, Bali's engagement with global tourism and its role as an international destination brings pressures on its natural resources. THK is anticipated to be the philosophy for Bali island to navigate these pressures, balancing global influences with local sustainability principles.

As both a boundary concept and a tool for local governance, THK helps Bali manage its resources and maintain its cultural identity in the face of globalisation. It also showcases the inherent resilience of island societies, illustrating how cultural frameworks like THK enable islands to confront external pressures while preserving their unique socio-environmental fabric. This dual function of THK—anchoring Bali's islandness while providing a platform for navigating global challenges—highlights the concept's critical role in maintaining the balance between development and sustainability.

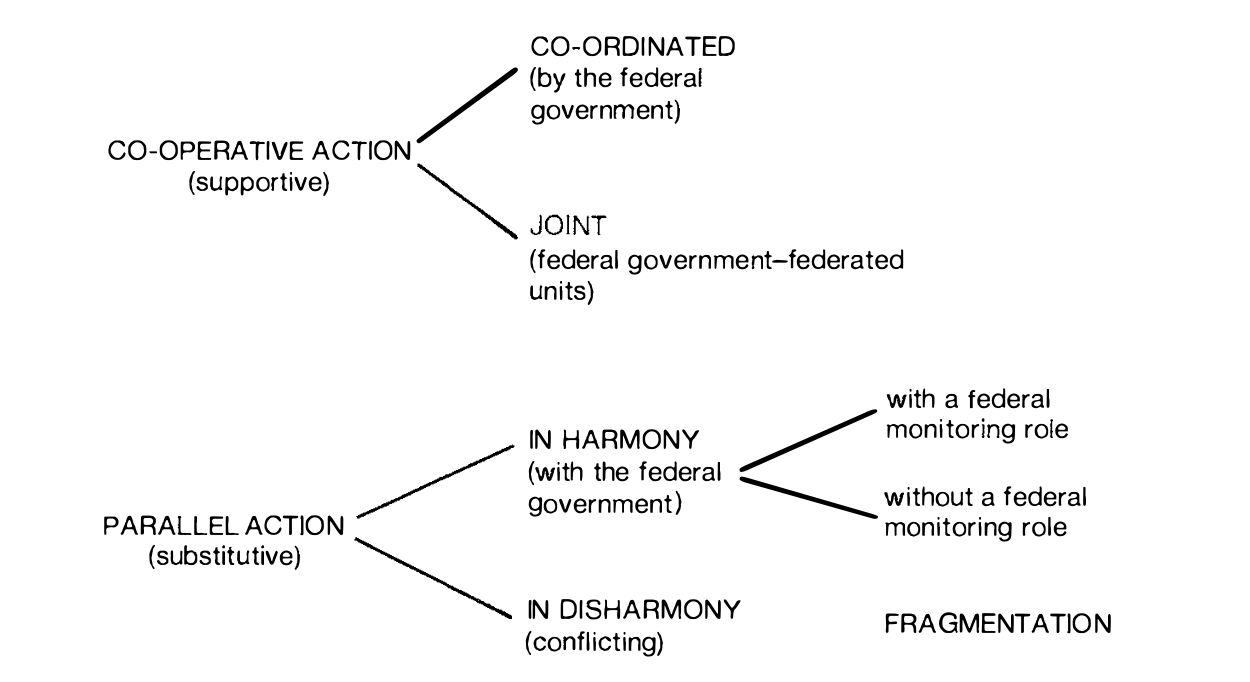

According to Soldatos (1990) four distinct patterns characterize the relationships between regional and national governments. The first, known as the cooperative-coordinated pattern, entails regional participation in international affairs while working in coordination with the national government. The second is the cooperative-joint pattern, suggests that paradiplomacy is integrated into the national foreign policy framework. The third is the parallel-harmony pattern, in which regional governments operate independently within their competencies, while ensuring that their actions align with and do not contradict national foreign policies. Lastly, the parallel-disharmony pattern indicates that the actions taken by a regional government conflict with national and central government policies.

Source: Soldatos (1990)

In this framework, Balinese paradiplomacy aligns with the cooperative-coordinated pattern, where the provincial government collaborates with the Indonesian government to ensure that its diplomatic activities respect Indonesian sovereignty, aligned with the existing regulation. This approach also allows Bali to have the flexibility to pursue its regional interests while maintaining a harmonious relationship with the national government. The following section discusses how Bali incorporates THK within its paradiplomatic blueprint.

3.1. Parhyangan in the Balinese Paradiplomacy

Parhyangan is one of the core principles of Tri Hita Karana. Its focus is on the harmonious relationship between humans and the divine. This spiritual connection plays a vital role in Bali’s paradiplomacy, especially in fostering international relations that are rooted in shared religious and cultural values. Bali’s spiritual diplomacy often intersects with countries and regions that have strong spiritual heritages, creating opportunities for cultural exchanges and deeper international cooperation.

In Bali, the implementation of Parhyangan is depicted in the relationship with God, as the majority of Balinese people are Hindu, with approximately 86,5% in 2024 (Darmawan, 2024). Other than the vital role of religion, the practice of Balinese Hinduism is also influenced by the Balinese customs and traditions, which may differ from the practices of Hindu in other places, such as in India. Nevertheless, the shared heritage and values between Bali and India through Hinduism are portrayed through their paradiplomacy. An example of this is the relationship between Bali and the state of Uttarakhand in India. The spiritual ties between these two regions are evident in their respective identities: Bali is known as the "Island of the Gods," while Uttarakhand is often referred to as the "Land of the Gods." This alignment of spiritual predicates underscores the common religious heritage that serves as the foundation for cooperation between the two regions. Additionally, Bali is a popular tourist destination for many people from India. In 2017, both sides expressed their intention to establish further collaboration, drawing on their rich historical connection and shared values in religion and tradition (Devita, 2017).

This connection is further deepened by the fact that Uttarakhand is considered a holy pilgrimage site for many Balinese Hindus. The cultural and spiritual significance of this location not only enhances Bali's paradiplomacy but also solidifies the role of Parhyangan in shaping the province's foreign relations. Bali’s diplomatic engagement with Uttarakhand is not simply about political or economic interests but is fundamentally rooted in shared spiritual values. This form of paradiplomacy is distinct because it leverages religion as a bridge for creating mutual understanding and cooperation between the two regions, which contributes to achieving harmony between people and the divine (Parhyangan).

Bali’s Parhyangan-based paradiplomacy finds expression in the work of the Ashram Gandhi Puri, a spiritual-based organization that fosters people-to-people diplomacy by building connections between Balinese youth and their counterparts. The Ashram Gandhi Puri has collaborated with Swami Vivekananda Cultural Centre (SVCC) Bali through World Hindi Day 2025. The objective of SVCC Bali is to promote bilateral cultural linkages between Indonesia and India. Ashram Gandhi Puri's director, I Wayan Sari Dika, initiated people-to-people diplomacy with India through enhancing the understanding of Hindi, considering its contribution in literatures, culture, and communication (Admin Atnews, 2025). These efforts highlight how spiritual institutions are at the forefront of Bali’s paradiplomacy, reinforcing Parhyangan as a guiding principle in fostering cultural exchange.

What makes Bali’s case particularly unique is how the principle of Parhyangan connects with the broader concept of islandness. Bali is a Hindu-majority province in Indonesia, which imbues it with a distinct cultural and religious identity compared to the rest of the nation. This religious distinction is not only central to the island’s local governance and social structure, but also shapes how Bali positions itself on the global stage through paradiplomacy. Bali’s islandness—its cultural and geographic singularity—further elevates the role of Parhyangan in its external relations. The island’s spiritual identity becomes a focal point of its paradiplomatic efforts, allowing Bali to build meaningful connections with other regions and countries that share similar spiritual or religious foundations.

Parhyangan in Bali’s paradiplomacy mainly resonates with India, with Hinduism as the core similarity. The latest example can be found through the initiative by the Consulate General of India in Bali, that organized an international conference called “India-Indonesia Cultural Conference 2024” with the theme “Echoes across the Waves: Revisiting the Intersections of India and Indonesia’s shared Cultural Heritage” in September 2024. This conference was also organized to commemorate 75 years of Indonesia-India diplomatic relations (Widyati & Oetomo, 2024). It highlighted the religious and spiritual aspects that connect with the value of Parhyangan. The conference included discussion on multiple sub-topics, including Hindu-Buddhist traditions, where religion and culture intertwine, in both Balinese and Indian society (Consulate General of India Bali, 2024). It is intriguing to explore how common spiritual grounds are being embraced, despite differences in rituals and ceremonial details. Furthermore, follow-up action after this conference involves cooperation among relevant institutions in Bali and India, including with Indonesian Hindu Scholars Association. This conference served as a concrete realization of how international relations and island culture can nurture spiritual harmony. Through these initiatives, Bali’s paradiplomacy goes beyond traditional diplomatic activities, incorporating spiritual and religious exchanges as a central component of its international engagement.

3.2. Pawongan in the Balinese Paradiplomacy

Pawongan, the second principle of Tri Hita Karana, emphasizes the importance of human relationships and communal well-being. In the context of Bali’s paradiplomacy, Pawongan represents the province’s commitment to fostering people-to-people connections and ensuring that its international relationships contribute to the social and economic prosperity of its residents. This aspect of Balinese diplomacy underscores the importance of human capital, community empowerment, and resilience, particularly in a globalized world where international cooperation is crucial for the well-being of local populations. The idea of Pawongan is especially significant when viewed through the lens of islandness, as Bali’s geographic isolation requires strong communal ties and resilience to external challenges.

In terms of Pawongan, Balinese people have certain characteristics that are rooted in their island identities. For example, Balinese women often face the dilemma of balancing household management, work life, and their duties to society. Therefore, they have to navigate, not only double roles, but also social role (desa adat), which create a triple-role situation (Suyadnya, 2009). Balinese island identity is closely related to community-based socialization processes, through banjar (small unit within the village). Pawongan serves as the core value to ensure harmony among people. In the context of international relations, the government of Bali aims to ensure the development of human resources, for instance, through tourism, culture, and education.

Reflections of island culture that relate to human interaction and harmony or Pawongan are illustrated through collaboration with external partners in the annual cultural event hosted by the Government of Bali, called Pesta Kesenian Bali (Bali Arts Festival). This Festival is one of the most prestigious ones in Bali, providing an opportunity for local people and foreigners to come together in the enjoyment of various cultural performances. Bali Arts Festival has been showcasing the arts and cultural aspects of Balinese people and beyond. Organized annually with a different theme, this festival aims to ensure that Balinese arts and culture can be maintained sustainably, despite the current changes and global dynamics (indonesia.go.id, 2019).

Collaboration with government and group of performers from other countries is a reflection of Pawongan, which emphasizes harmony among people. Performers attempted to showcase the uniqueness of different cultures that can collaborate in Bali Arts Festival. Furthermore, this type of collaboration can be a platform for people-to-people interactions to raise awareness and understanding of various cultural heritage. In 2006,15 arts groups from different countries took part in the 28th Bali Arts Festival, including from Japan, South Korea, United States of America, Germany, Canada, United Kingdom, India, Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia. The performances of these overseas groups were appreciated as a positive contribution enriching the diversity of cultural performances in the festival (Suryanto, 2006). The interaction of different people coming from various background is an important part of people-to-people interaction that involve cultural aspects, as part of the implementation of Pawongan.

In 2024, the government of Bali organized Bali World Culture Celebration (BWCC) in the 46th Bali Arts Festival. BWCC, which was started in 2022, is conducted to provide a collaborative platform for nine countries to participate in showcasing their arts performances, including China, USA, and India. This collaboration aims to encourage the young generation to understand the diversity of traditions from different countries, and therefore is expected to ignite collaboration to create something new (Putri, 2024). In addition to that, for the first time, Ukraine arts group participated in Bali Arts Festival 2024, by performing Ukraine’s dances called Tambourine, Hopak, and Pryvit. It is expected that collaboration among people, particularly artists, can create an acculturation of Balinese culture with other cultures. The performance from Ukraine are part of an effort to secure peace and improve inter-cultural understanding (Samudero, 2024).

An excellent example of Pawongan in Bali’s paradiplomacy is its sister province cooperation with Jiangxi Province in China. In 2024, the government of Bali and Jiangxi, China have signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in the occasion of Jiangxi-Bali Economic and Trade Cooperation Fair, formalizing cooperation in the areas of tourism, culture, education, and trade. This partnership highlights the strategic focus on improving the livelihoods of Balinese people by opening new avenues for tourism, trade, economy, culture, and education, which are critical for both economic and social development (Nusa Bali, 2024). This cooperation is a crucial opportunity for Bali to showcase more products and services to Jiangxi. Hence, having trade initiative aligns with the principle of Pawongan, as it directly contributes to the economic well-being of the Balinese people by creating new markets for local products.

In addition to trade, the Pawongan principle is also evident in the scope of education. The interest to learn the Balinese way of life and their unique islandness characteristics can be depicted from the frequent request to study THK. According to Professor I Nyoman Darma Putra, an expert in Bali studies at the Udayana University, there are many summer courses that want to focus on THK subject to learn about Bali. As an example, summer courses with students from China were very delighted to learn about islandness in Bali, particularly about THK. According to the key informant, the interest in learning about THK is essential to connect people-to-people collaboration. THK can be considered as a “knowledge icon” of Bali, highlighting the recognition of Bali’s value at the global level (Putra, 2025). By providing opportunities for students to engage in international learning experiences, Bali’s paradiplomacy reflects a deep commitment to improving the social and intellectual well-being of its people, a key tenet of Pawongan.

Another initiative that highlights Pawongan in Bali’s paradiplomacy is the collaboration with the Hainan Provincial Government of China. In this partnership, Bali and Hainan signed the “One City, One Media” Friendship Agreement, which seeks to enhance media cooperation between the two regions. This agreement aims to foster better communication and information exchange between media practitioners from both provinces, covering both traditional and modern media formats (Intentilia, 2024). The involvement of civil society in this cooperation is significant, as it empowers local media professionals to engage in international communication, share local stories on a global platform, and strengthen ties between Bali and Hainan. This program contributes to the overall resilience of Bali’s communities by enabling the island’s civil society to take an active role in shaping its global narrative, ensuring that Balinese people remain connected and informed in an increasingly interconnected world.

The Pawongan principle also aligns with the concept of resilience, which is an integral part of Bali’s islandness. As an island province, Bali is particularly vulnerable to external shocks, whether they be economic, environmental, or social in nature. The geographic isolation inherent in islandness necessitates a strong emphasis on human relationships and community resilience, as these factors are essential for the island’s survival and prosperity. Through its paradiplomacy efforts, Bali has actively sought to build resilience by fostering international cooperation in areas such as trade, education, and civil society engagement. The partnerships with Jiangxi and Hainan demonstrate how Pawongan drives these efforts, ensuring that the well-being of Bali’s people remains at the forefront of its international relations.

Moreover, by promoting educational exchanges and civil society involvement, Bali’s paradiplomacy seeks to empower its residents, particularly the younger generation. The collaboration with Hainan’s media practitioners enhances Bali’s ability to communicate its cultural values and economic opportunities to a global audience, further strengthening the resilience of the island’s communities. Pawongan plays a crucial role in shaping Bali’s paradiplomacy by emphasizing the importance of human relationships and the well-being of the island’s population. These efforts align with the broader concept of islandness, as they address the unique challenges faced by Bali as an island province and highlight the importance of building strong communal ties and resilience in the face of external pressures.

3.3. Palemahan in the Balinese Paradiplomacy

The third and final principle of Tri Hita Karana, Palemahan, focuses on the harmonious relationship between humans and the natural environment. This concept is closely aligned with the global sustainability agenda, particularly the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which seek to foster economic, social, and environmental well-being. In the context of Bali’s paradiplomacy, Palemahan reflects the province’s commitment to promoting sustainable development, especially through its international partnerships and cooperation. Bali's engagement with the SDGs is exemplified by its focus on sustainable tourism, an area that deeply resonates with Palemahan. Tourism is one of the most significant sectors in Bali’s economy and culture, and it is no surprise that tourism and culture mentioned the most in Bali’s sister province cooperation agreements.

The SDGs most directly connected with tourism in Bali include SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), which promotes entrepreneurship, creativity, and local products, as well as SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), which emphasizes the development of tools to monitor the sustainable impact of tourism. Additionally, SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) highlights the need to protect cultural and natural heritage, an important consideration for Bali, where tourism and culture are intertwined in nearly every aspect of life (Intentilia, 2024). One significant aspect of Bali’s paradiplomacy is its international cooperation to promote sustainable tourism, which directly supports Palemahan. The Balinese government’s sister province cooperation agreements often include commitments to preserving and promoting cultural and natural resources, which is aligned with targets such as SDG 11.4 (protect and safeguard cultural and natural heritage).

To achieve harmony between people and the environment, Bali collaborates with foreign government in tackling various problems, including on the issue of waste management. As an example, the government of Badung, one of the regencies in Bali, received RA-X machine as a grant from the Japanese government. Mayor of Toyama, Japan, and the Acting Regent of Badung witnessed the inauguration of this machine’s operationalization in October 2024. This machine is expected to process organic waste into compost. A representative of Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) highlighted that the operationalization of this machine, with the value of approximately 10 billion rupiah for the machine granted by the Japanese government and 7 billion rupiah for the electricity and infrastructure provided by the government of Badung, can reduce the waste volume and contribute to create compost that can be beneficial to agriculture (Yusuf et al., 2024). Improving the infrastructure on waste management and technological transfer from government abroad is a proof of paradiplomacy strategy of Balinese government that address the environmental aspect, aligned with the value of Palemahan.

During Indonesia’s G20 Presidency in 2022, the Coordinator of the President’s Special Staff and an anthropologist from France mentioned that the philosophy of THK can be used by the States’ leaders to address various global challenges, including the climate crisis. Despite the differences in various countries, it is important to find a common ground facilitated by constructive dialogue, to achieve harmony and peace (Lazuardi & Suryatmojo, 2022). Furthermore, a representative of China also highlighted Bali’s important position at the global level. The President of the People's Republic of China addressed the importance of Bali as a model for internationalization, suggesting that Hainan Province, China, should draw lessons from Bali's advanced practices in this area. There are three major points that can be learned by Hainan Province, China, from Bali’s best practices: (i) relationship between the people and the environment; (ii) development of culture-based tourism; and (iii) tourism village (Bali Tribune, 2023). This acknowledgment underscores Bali's prominent position in global diplomacy and cultural exchange. Such visit and statements emphasize the critical role that cultural diplomacy plays in the framework of Bali’s sister province cooperation. By fostering relationships with international stakeholders and showcasing its unique cultural heritage, Bali not only reinforces its identity on the global stage but also strengthens its collaborative efforts in tourism, education, and sustainable development. These interactions illustrate how paradiplomacy is integral to enhancing Bali's international standing, facilitating knowledge exchange, and promoting mutual understanding, which are essential for successful sister province partnerships.

Bali’s focus on Palemahan is not limited to tourism. Environmental considerations are woven into various aspects of Bali’s international cooperation. Agriculture, health, and the environment, though mentioned less frequently in Bali’s sister province agreements, are also critical to the island’s sustainable development. The focus on sustainable agricultural practices and environmental preservation speaks directly to Palemahan, as these sectors are crucial for maintaining the balance between human activity and the natural world. For example, the mention of sustainable practices in agriculture and the development of science and technology in Bali’s partnerships indicates an awareness of the environmental impact of these activities and the need to integrate sustainability into every facet of international cooperation. In addition, Palemahan aligns with SDG 17, which emphasizes the importance of partnerships to achieve global sustainability goals. Bali’s paradiplomacy often involves multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilize knowledge, technology, and financial resources, in line with SDG 17.16. The global partnerships Bali has fostered, particularly with provinces such as Jiangxi and Hainan, are vital for sharing best practices and resources to address environmental challenges, another key pillar of Palemahan.

At the global level, THK is also being recognized by UNESCO, through its cultural landscape and subak, a cooperative water management system of canals and weirs, which can be traced back to the 9th century. THK accentuates the philosophy of spirit, human world, and nature (UNESCO, no date). It shows that relations between the concept of islandness and THK has been intertwined for a significant period of time. In the agricultural sphere, for instance, THK is employed to guide sustainable practices, framing the use of land and water as both practical and sacred (Roth & Sedana, 2015). In tourism, it has become a hallmark of sustainability, with hotels adopting THK to promote eco-friendly practices that align with global environmental standards, linking modern development with traditional Balinese values (Picard, 1990). As Roth & Sedana (2015) also observe, the political utility of THK also allows policymakers to frame environmental and social challenges as cultural issues, ensuring all policies adhere to cultural sensitivities in their application.

Moreover, Bali’s commitment to sustainable development extends beyond economic growth and environmental preservation; it is also about fostering a broader cultural and ethical responsibility. The preservation of customs, traditions, and the environment are integral to Bali’s identity, and they play a significant role in its international relations. By integrating environmental sustainability into its sister province agreements, Bali is addressing local environmental concerns, as well as contributing to global efforts to combat climate change and environmental degradation. This is particularly important for Bali, an island highly dependent on its natural resources and vulnerable to the impacts of global environmental change.

While this paper primarily explores the link between THK and paradiplomacy as presented in the previous sections, it is also important to recognize the various challenges of THK implementation amidst the globalization. Balinese people struggle to balance economic growth from tourism development with environmental conservation. Critics have questioned whether THK has become merely a “jargon” without tangible implementation. In an interview with key informant Professor I Nyoman Darma Putra, it was highlighted that the primary challenge of implementing THK can be seen from various aspects, namely: waste management (related to Palemahan); the problems of social frictions (related to Pawongan); and then these two issues bring into question the sincerity of implementing spiritual connection (related to Parhyangan) (Putra, 2025). The problem of achieving harmony with the environment (Palemahan) in Bali is, among others, the inadequate waste management system, which poses significant harm to the environment. Waste continues to be the main environmental challenge in Bali (Dinas Lingkungan Hidup dan Kebersihan Kabupaten Badung, 2018); (DetikBali, 2025). In the context of Pawongan (harmony among people) in Bali, conflict and social friction have been increasingly frequent between newcomers and local people, as noted by Suyadnya (2021).

To ensure THK remains relevant, the contextualization of THK understanding needs to aways be updated. Bali should be proud to have THK as a concept that contributes to the global knowledge, focusing not only on human beings, but also on the environment (Putra, 2025). It is essential for Balinese people to preserve and implement THK meaningfully. Additionally, sister province cooperation, as a form of paradiplomacy, can be an important channel for promoting the implementation of THK in Balinese way of life.

4. Conclusion

Bali’s approach to paradiplomacy, guided by the principles of Tri Hita Karana—Parhyangan, Pawongan, and Palemahan—offers a strong foundation for building international relations while also promoting the island’s unique culture and supporting sustainable development. These three interlocking principles shape Bali’s domestic policies and influence its global interactions, allowing this Indonesian province to play an important role in international affairs. In this case, Bali effectively addresses the challenges of working with the global community, highlighting its special geographic, cultural, and spiritual qualities. Despite the current obstacles in the implementation of THK, these values are still relevant in strengthening Bali’s position in the international arena while ensuring that its growth is fair, inclusive, and respectful of the island’s cultural and natural heritage. Through its paradiplomatic efforts, Bali illustrates how local values and the distinct qualities of islandness can be used to tackle global challenges. The global interest in THK is a reflection that this unique value positively represents Bali island and enhance its reputation for international relations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their profound gratitude to Professor I Nyoman Darma Putra of Udayana University for his invaluable insights and contributions as the key informant for this research.

References

- Admin Atnews. (2025, January 11). SVCC Bali—Ashram Gandhi Puri merayakan Hari Hindi Sedunia 2025. Atnews.id. https://atnews.id/portal/news/24040/

- Baldacchino, G. (2008). Studying islands: On whose terms? Some epistemological and methodological challenges to the pursuit of island studies. Island Studies Journal, 3(1), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.214

- Bali Tribune. (2023, February 21). Presiden China instruksikan Provinsi Hainan belajar ke Bali. Balitribune.co.id. https://balitribune.co.id/content/presiden-china-instrusikan-provinsi-hainan-belajar-ke-bali

- Bartmann, B. (2006). In or out: Sub-national island jurisdictions and the antechamber of para-diplomacy. The Round Table, 95(386), 541–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358530600929974

- Consulate General of India Bali. (2024, September 19). Press statement: India Indonesia Cultural Conference 2024 [Official website]. Cgibali.gov.in. https://www.cgibali.gov.in/news_detail/?newsid=329

- Covarrubias, M. (2018). Island of Bali. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315831763

- Darmawan, A. D. (2024, October 20). 86,5% penduduk di Bali beragama Hindu di Bali 2019-2024. Databoks.katadata.co.id. https://databoks.katadata.co.id/demografi/statistik/3f7a042c5684228/86-5-penduduk-di-bali-beragama-hindu

- DetikBali. (2025, January 5). Sampah pantai Bali mengkhawatirkan sampai empat menteri harus turun tangan. Detik.com. https://www.detik.com/bali/berita/d-7717916/sampah-pantai-bali-mengkhawatirkan-sampai-empat-menteri-harus-turun-tangan

- Devita, R. (2017, December 22). Bali diharap jadi “Sister Province” Uttarakhand India. Balipost.com. https://www.balipost.com/news/2017/12/22/32275/Bali-Diharap-Jadi-Sister-of...html

- Dinas Lingkungan Hidup dan Kebersihan Kabupaten Badung. (2018, April 10). Sampah masih jadi isu lingkungan utama di Bali [Official website]. Dislhk.Badungkab.go.id. https://dislhk.badungkab.go.id/artikel/18345-sampah-masih-jadi-isu-lingkungan-utama-di-bali

- Duchacek, I. D. (1984). The international dimension of subnational self-government. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 14(4), 5–31.

- Encontre, P. (1999). The vulnerability and resilience of small island developing states in the context of globalization. Natural Resources Forum, 23(3), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-8947.1999.tb00914.x

- Foley, A., Brinklow, L., Corbett, J., Kelman, I., Klock, C., Moncada, S., & Walshe, R. (2023). Understanding “islandness.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 113(8), 1800–1817.

- Grydehøj, A. (2017). A future of island studies. Island Studies Journal, 12(1), 3–16.

- Hall, C. M. (2012). Island, islandness, vulnerability and resilience. Tourism Recreation Research, 37(2), 177–181.

- Handam, Kartini, D. S., Suwaryo, U., & Muradi. (2024). Actor/agent-structure relations of “Adat government” in Adat Tanjung Benoa village government system, Badung Regency, Bali Province. International Journal of Religion, 5(10), 4329–4340. https://doi.org/10.61707/hqesqc68

- indonesia.go.id. (2019, June 16). Pesta Kesenian Bali: Festival kesenian terlama di Indonesia. Indonesia.go.id. https://indonesia.go.id/kategori/komoditas/824/pesta-kesenian-bali-festival-kesenian-terlama-di-indonesia

- Intentilia, A. A. M. (2024). Identifying cultural diplomacy and sustainable development in sister province cooperation of Bali, Indonesia. Jurnal Kajian Bali (Journal of Bali Studies), 14(2), 373. https://doi.org/10.24843/JKB.2024.v14.i02.p04

- Intentilia, A. A. M., & Surya Putra, A. A. B. N. A. (2021). From local to global: Examining sister city cooperation as paradiplomacy practice in Denpasar City, Bali, Indonesia. Jurnal Bina Praja, 13(2), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.21787/jbp.13.2021.357-367

- Kanal Bali. (2021, February 20). Mantan Menteri Pariwisata RI, Gede Ardika, tutup usia. kumparan.com. https://kumparan.com/kanalbali/mantan-menteri-pariwisata-ri-gede-ardika-tutup-usia-1vDCqjUNPCY/full

- Kencana, I. G. A. M. D., & Elvianti, W. (2021). Affecting factors of sister city cooperation between Denpasar government and Mossel Bay government in 2019. Indonesian Journal of International Relations, 5(2), 264–291.

- Lansing, J. S. (2005). On irrigation and the Balinese state. Current Anthropology, 46(2), 305–308.

- Lasahido, I., & Bhwana, P. G. (2023, January 25). Tripadvisor awarded Bali as the second popular destination in the world. Tempo.co. https://en.tempo.co/read/1683637/tripadvisor-awarded-bali-as-the-second-popular-destination-in-the-world

- Lazuardi, A., & Suryatmojo, H. D. (2022, October 27). Filosofi Bali bisa jadi jawaban bagi KTT G20 capai kesepakatan. antaranews.com. https://www.antaranews.com/berita/3205529/filosofi-bali-bisa-jadi-jawaban-bagi-ktt-g20-capai-kesepakatan

- Lewis, J., & Lewis, B. (2009). Bali’s silent crisis: Desire, tragedy, and transition. Lexington Books.

- Listiani, W., Ningdyah, A. E. M., & Rohaeni, A. J. (2024). Desire to revisit: Memorable experiences drive domestic tourists to return to Bali. Jurnal Kajian Bali (Journal of Bali Studies, 14(1), 147. https://doi.org/10.24843/JKB.2024.v14.i01.p07

- Nusa Bali. (2024, April 25). Bali-Jiangxi tandatangani MoU sister province. nusabali.com. https://www.nusabali.com/berita/165831/bali-jiangxi-tandatangani-mou-sister-province

- Paquin, S. (2020). Paradiplomacy. In T. Balzacq, F. Charillon, & F. Ramel (Eds.), Global diplomacy: An introduction to theory and practice (pp. 49–62). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Picard, M. (1990). “Cultural tourism” in Bali: Cultural performances as tourist attraction. Indonesia, 49, 37–74.

- Purwanto, H. (2017, March 23). Bali named world’s best tourism destination. Antaranews.com. https://en.antaranews.com/news/110069/bali-named-worlds-best-tourism-destination

- Putra, I. N. D. (2025, January 6). Interview [In-person interview].

- Putri, N. M. L. K. (2024, June 23). Kesenian tradisional China ikut tampil di PKB 2024 (Traditional Chinese arts to perform at Bali Arts Festival 2024). detik.com. https://www.detik.com/bali/budaya/d-7403835/kesenian-tradisional-china-ikut-tampil-di-pkb-2024

- Roth, D., & Sedana, G. (2015). Reframing Tri Hita Karana: From ‘Balinese culture’ to politics. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 16(2), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2014.994674

- Samudero, R. S. (2024, July 9). Mengenal budaya Ukraina di Pesta Kesenian Bali 2024 (Get to know Ukrainian culture at Bali Arts Festival 2024). detik.com. https://www.detik.com/bali/budaya/d-7431225/mengenal-budaya-ukraina-di-pesta-kesenian-bali-2024

- Soldatos, P. (1990). An explanatory framework for the study of federated states as foreign-policy actors. In H. J. Michelmann & P. Soldatos (Eds.), Federalism and international relations: The role of subnational units (pp. 34–53). Oxford University Press.

- Stratford, E., & Wells, S. (2009). Spatial anxieties and the changing landscape of an Australian airport. Australian Geographer, 40(1), 69–84.

- Surwandono, S., & Maksum, A. (2020). The architecture of paradiplomacy regime in Indonesia: A content analysis. Global: Jurnal Politik Internasional, 22(1), 77–99.

- Suryanto. (2006, April 4). 15 Grup kesenian asing pentas di Bali (15 foreign art groups perform in Bali). antaranews.com. https://www.antaranews.com/berita/31192/15-grup-kesenian-asing-pentas-di-bali

- Suyadnya, I. W. (2009). Balinese women and identities: Are they trapped in traditions, globalization or both? Masyarakat, Kebudayaan dan Politik, XXII(2), 95–104.

- Suyadnya, I. W. (2021). Tourism gentrification in Bali, Indonesia: A wake-up call for overtourism. Masyarakat: Jurnal Sosiologi, 26(2). https://doi.org/10.7454/MJS.v26i2.12930

- UNESCO. (n.d.). Cultural landscape of Bali Province: The Subak system as a manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana philosophy [Official Website]. whc.unesco.org. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1194/

- Utomo, A. B. (2022). Paradiplomacy as the product of state transformation in the era of globalisation: The case of Indonesia. JANUS NET E-Journal of International Relation, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.26619/1647-7251.13.1.5

- Wiana, I. K. (2004). Menuju Bali Jagadhita: Tri Hita Karana sehari-hari. In I. N. D. Putra (Ed.), Bali Menuju Jagadhita: Aneka Perspektif. Pustaka Bali Post.

- Widyati, P. D. K., & Oetomo, H. R. (2024, September 17). International Cultural Conference 2024, penguatan jalinan hubungan bilateral India-Indonesia. rri.co.id. https://www.cgibali.gov.in/news_detail/?newsid=329

- Yusuf, F., Nampu, R., & Saptiyulda, E. (2024, October 22). Pemkab Badung resmikan mesin pengolah sampah bantuan dari Jepang. antaranews.com. https://www.antaranews.com/berita/4414889/pemkab-badung-resmikan-mesin-pengolah-sampah-bantuan-dari-jepang