Reconstructing Island Identity: From Stigma and Scars to a Culture of Recognition

Abstract

This study explores the impact of local branding initiatives in the southwestern archipelago of South Korea, focusing on how they transform negative perceptions of islands—often associated with isolation, disconnection, and underdevelopment—into vibrant and engaging communities. Branding, beyond a promotional strategy, serves as a powerful tool for preserving and promoting cultural values, fostering social recognition, and reshaping regional identities.

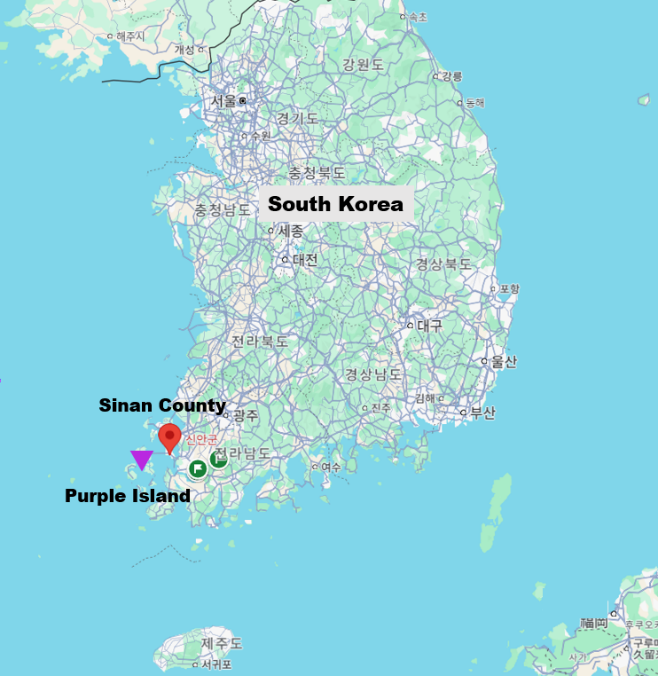

A key case examined is the branding of Purple Island in Shinan County, where both government agencies and local residents actively participated in redefining the island’s image. Through strategic branding efforts, Shinan County has sought to overcome historical stigmas attached to island communities, demonstrating how localized branding can be leveraged to foster broader social recognition and inclusion.

Additionally, this study explores how local residents develop and utilize regional resources to construct a new collective identity, while also analyzing how islanders adopt and consume new images to restore their social identity.

Furthermore, the study underscores the role of narratives and storytelling in shaping island identity. Drawing on Hay’s (2006) concept of place identity, it highlights that islands should not be viewed merely as geographic locations but as deeply intertwined with human experience, culture, and history. By emphasizing the multifaceted nature of island communities, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of how islands transition from marginalized and stigmatized spaces to dynamic cultural and economic hubs through local branding and identity reconstruction.

Keywords

Korea, island, regional identity, place identity, periphery, stigma, ‘One Island One Garden’ Policy, recognition

1. The Duality of Island Perception and Social Stigma

The English word “island” is a compound of “is” (water) and “land” (territory), literally meaning “land surrounded by water.” This etymology reflects the dual nature of islands, encompassing both maritime (water) and terrestrial (land) elements. According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), an island is defined as “a naturally formed area of land surrounded by water.” However, the definition of an island remains ambiguous and relative.

Baldacchino (2005: 247-248) points out that the image of islands is often intertwined with mythical fantasies, stating that “an island can be perceived as a utopian paradise or, conversely, as a gulag-like prison”. This duality is particularly evident in tourism, where islands are often perceived as romantic destinations for leisure, yet not necessarily desirable places to live. The distinction between extraordinary experiences versus everyday lifebecomes apparent—for instance, recreational fishing is seen as enjoyable, while professional fishing is considered difficult, hazardous, and unpleasant.

Scholars analyzing island identityfrequently highlight the inherent duality of islands (Conkling, 2007; Depraetere & Dahl, 2018; Baldacchino, 2020), particularly in terms of isolation versus connectivityand closure versus openness. This dual nature itself defines islandness (Hong & Pungetti, 2012).

Islands are sometimes perceived as bridges of communication, yet at other times as symbols of isolation. This dual perception of islands is closely tied to the way societies perceive the sea. For example, in Korea, during the “Age of the Sea” (10th-13th centuries, Goryeo Dynasty), when maritime activities were thriving, islands functioned as vital hubs of exchange and communication. However, during the “Era of Maritime Prohibition” (14th-19th centuries, Joseon Dynasty), when maritime activities were banned, islands came to symbolize isolation and marginalization.

The sea ban (海禁) policy of the Joseon Dynasty resulted in large-scale forced migration of island residents to the mainland, leaving islands deserted. This was known as the “empty island policy” (空島政策), which was implemented to protect border residents from external threats such as pirate invasions. However, this policy also led to the weakening of Joseon’s maritime capabilitiesover time.

Furthermore, Neo-Confucian ideologyreinforced negative perceptions of maritime activities and seafarers. Korean Confucianism, which originated from Chinese Confucian thought, evolved uniquely in Korea and became the dominant philosophical and ethical system during the Joseon Dynasty. This ideology emphasized agriculture over commerce and industry, leading to social discrimination against merchants, artisans, and fishermen.

Historically, Korea’s economic decline was closely linked to global trade disruptions. For instance, during the late Goryeo period, Korea thrived as a key intermediary in East Asian trade (between the Yuan Dynasty, Goryeo, and Japan). However, the collapse of this trade network due to the global Black Death pandemic and the decline of the Silk Roaddevastated Korea’s economy. When Joseon replaced Goryeo, it prioritized Confucian ideals, disregarded commerce, and pursued a self-sufficient agrarian society. As a result, fishermen and islanders became socially marginalized, viewed as inferior and unworthy of recognition.

In addition to this marginalization, islands in Korea have historically been used as places of exile. During the Goryeo Dynasty (高麗時代, 918–1392) and the Joseon Dynasty (朝鮮時代, 1392–1897), exile was considered the harshest punishment next to execution. It was primarily imposed on political criminals, and the severity of their punishment was determined by the distance between their place of exile and the mainland. Since islands were remote and isolated, locations such as Jeju Island and various islands off the coast of Jeolla Province became common exile sites.

Even in the modern era of globalization and increased international exchange, prejudice, stigma, and discriminationagainst certain regions persist. Throughout history, derogatory language and stereotypes have been used to marginalize specific groups or areas. For instance, in East Asia, slurs such as “Chinky” and “Shrimp Eye” have been used to demean people of Asian descent. Likewise, in Korea, derogatory terms like “Hongeo” (fermented skate) are used to stereotype people from Jeolla Province, reinforcing regional discrimination. Hongeo, a traditional delicacy of Shinan County, has been appropriated as a slur, equating Jeolla residents with the pungent fish.

Another derogatory term, “Jeolladian” ('전라디언', Zoladian), adds “-ian” (a suffix denoting a people group) to “Jeolla,” implying otherness and alienation. Similarly, “Shinan Drip” refers to internet jokes and derogatory remarks about Shinan County, particularly in reference to the 2014 “Shinan Salt Farm Slave Incident”. This case, where disabled workers were subjected to forced labor, abuse, and imprisonment, shocked the nation, reinforcing Shinan’s negative reputation as a lawless, human rights-violating region. The stigma intensified with subsequent events, such as the 2016 large-scale illegal poppy cultivation scandal, leading many to perceive Shinan as a criminal hub beyond government oversight. The opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) is a plant used as a raw material for opium, and in South Korea, it is strictly prohibited from being cultivated for any purpose, including ornamental use, under the Narcotics Control Act.

Although crime statistics do not necessarily indicate a higher crime rate in Shinan than in other regions, sensationalized incidents have cemented the island’s negative image in the public consciousness. Due to its geographical isolation and difficult accessibility, people assume that many more undiscovered crimes occurin Shinan’s remote islands. Consequently, Shinan County has been labeled as a closed and dangerous society, a perception that has severely damaged its regional identity.

Given that Shinan County comprises numerous small islands, concerns about high crime rates in proportion to the population persist. In isolated island societies, rumors and misinformation spread more easily, and tight-knit local networks (regional cartels) can hinder transparency and accountability. This further reinforces the stereotypethat islands are inherently closed-off societies.

Historically, when prejudice, hatred, and discrimination against a marginalized groupare repeated over time, they become structuralized and entrenched. This leads to “social stigmatization,” wherein island residents are socially isolated and excluded from the mainstream. Once stigmatized, islanders become invisible outsiders, treated as people who cannot coexist with the rest of society. As a result, they are forced to live with a damaged and despairing sense of identitywithin isolated, closed communities.

Goffman (1963) argues that stigma is not merely about personal disgrace but a relational concept, wherein individuals or groups are assigned negative identities by society. He suggests that one way to combat stigmais through moral courage—the ability to resist social prejudice and defend one’s self-worth. Despite facing the labeling effectof being perceived negatively by mainlanders, island residents can preserve their identity through moral courageby employing strategies such as passing, resisting, and identification.

Moreover, because stigma is shaped by perceptions rather than objective reality, branding plays a crucial role in overcoming social stigmatization. Self-brandingallows communities to reshape their narrativeand project a positive identityto the outside world.

The following section will examine how Shinan County has leveraged local branding strategies to counteract stigma and reconstruct its regional identity.

2. Image Making of Islands: Transforming from 'Peripheral Island' to 'Angel Island'

Conkling (2007) defines islandnessas “a metaphysical sensation derived from a heightened experience of physical isolation.” This perspective on an island’s sense of placeplays a crucial role in defining its humanistic topography.

For a long time, islands have been perceived as marginal spaces, often viewed from a mainland-centric perspective as isolated, economically underdeveloped, and socially excluded regions. However, a significant turning pointin altering the physical characteristics of islands came with the construction of bridges connecting islands to the mainland. This initiative has revolutionized mobility and logistics for island residents.

In Shinan County, a major infrastructure project aims to connect key islands to the mainland through a network of bridges. Beginning with Shinan Bridge No. 1 (1989), the county has since constructed 13 bridges, including the “Angel Bridge” (2019) and “Chupo Bridge” (2021). When all planned bridges (3 under construction and 6 in the planning stage, totaling 22 bridges) are completed, most islands within Shinan County—excluding the most remote ones—will be interconnected, forming a network known as the “Diamond Islands”. This bridge system has significantly contributed to improving transportation, facilitating the movement of agricultural and marine products, and enhancing mobility for island residents. Reduced logistics costs have led to higher prices for local produce, increased household incomes, and an improved quality of lifeas nationwide accessibility expands.

However, while physical connectivity has improved, the psychological perception of islands as remote and marginal areas persists. Shinan County has long been associated with negative perceptions, further exacerbated by sensationalized media coverage. Reports on the “island slave” incident, illegal drug cultivation, and derogatory references such as “Hongeo” (fermented skate, metaphorically used to mock Jeolla province residents) have reinforced deep-seated prejudices. The legacy of historical isolation policies, including the sea ban (Haijin) and the “empty island policy” that lasted for over 500 years during the Joseon Dynasty, continues to shape contemporary attitudes. Furthermore, negative portrayals of islands in popular culture—particularly in films and television—have solidified the island’s image as an isolated, backward, and closed society. Although the official Shinan County website promotesits rich natural resources, year-round attractions, pristine landscapes, and clean seas, the dominant social narrative continues to depict the region as underdeveloped and economically disadvantaged.

Shinan County, located in Southwestern South Korea, consists of an extensive archipelago originally comprising over 1,000 islands. Historically, these islands operated as disconnected economic and social units, but recent infrastructure developments have linked many islands to the mainland. The county is administratively divided into 14 towns and districts, broadly categorized into four regional zones. Despite its rich cultural heritage, Shinan faces significant challenges due to population decline and economic stagnation. Although designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site (“Korean Tidal Flats”), and home to Dadohae National Park, Ramsar Wetlands, and Slow City initiatives, the rapid outflow of younger generations due to a lack of job opportunities has accelerated regional decline.

One of the most pressing challenges facing contemporary South Korea is regional depopulation and demographic decline. In response, local governments have initiated strategies to revitalize struggling regions. Recognizing the urgent need to redefine its regional image, Shinan County launched ambitious branding efforts to combat negative perceptions and revitalize the local economy. Shinan County is home to the largest number of islands in South Korea, originally consisting of 1,025 islands (including 72 inhabited islands and 953 uninhabited ones), accounting for 25% of all islands in the country. While the official count is 1,025, for branding purposes, the county strategically promotes itself as the “1004 Islands” (천사섬)—a play on the Korean word “cheonsa” (meaning “angel”), creating the brand slogan “Shinan Islands = Angel Islands.”

The “1004 Islands” logo, uniquely incorporating numbers as a symbolic design element, represents the county’s geographical characteristics and ambitious vision for the future. This logo, officially trademarked by the Korean Intellectual Property Office in 2013, is continuously promoted as a key element of Shinan’s branding strategy. The goal of this initiative is to shift the perception of Shinan from a marginalized and stigmatized island region to a positive, recognizable, and inviting destination. The “Angel Island” project aims to highlight the region’s positive attributes through strategic branding, fostering regional revitalization and tourism development. All official signage and promotional materialsin Shinan County have been standardized under the “1004 Islands” brand, reinforcing a unified message. This branding strategy not only attracts external tourists but also fosters a renewed sense of collective identity among local residents. By redefining Shinan’s image from an isolated, impoverished region to a vibrant, fairytale-like destination, this initiative has successfully conveyed a unified and optimistic message to both internal and external audiences.

To further enhance its branding efforts, Shinan County launched the “Colorfull+ Shinan” initiative, which has been officially trademarked. The “Colorfull+ Shinan” brand categorizes the county’s diverse islands into seven distinct colors, symbolizing the region’s cultural diversity and the vibrant floral landscapes of individual islands. This branding initiative aims to raise awareness of Shinan’s unique identity, promoting local agricultural and seafood products, as well as its growing tourism industry. By leveraging color-themed branding, Shinan County seeks to further differentiate itself from other regions while showcasing the richness of its natural and cultural heritage.

The “Angel Island” project and “Colorfull+ Shinan” initiative represent a conscious effort to transform Shinan’s negative image into a vibrant and engaging identity. By focusing on strategic branding, regional revitalization, and cultural storytelling, these initiatives have demonstrated how branding can serve as a powerful tool for reshaping perceptions and fostering local pride. By shifting the dominant narrative from isolation and decline to vibrancy and opportunity, Shinan County’s branding efforts highlight the transformative power of place-based marketingin revitalizing marginalized island communities.

3. A New Vision: Transitioning from Fisheries Policy to “Garden Policy”

As regional depopulation and low economic growth persist, the threat of local extinctionhas become an urgent issue, prompting various regions to actively seek new strategies for regional revitalization. The tourism industryhas been increasingly recognized as a compelling strategy, as it not only generates jobs and incomebut also enhances regional branding and image (Kang, 2024).

Festivals play a key rolein shaping a region’s identityand fostering a positive brand image, ultimately serving as powerful tools for social, cultural, and economic revitalization. Since the introduction of local autonomy in Korea in 1992, regional festivals have been widely adopted as a means for local governments to express their unique characteristics. Festivals serve as platforms for conveying valuable cultural narratives, shaping the direction of regional development, and acting as expressions of regional identity within a short period (Ahn, 2009). By solidifying a region’s identity, festivals promote local resources and strengths, attract more tourists, and contribute to regional revitalization.

| Region | Seafood Type | Festival Period | Region | Seafood Type | Festival Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aphaedo | Octopus | May / Oct | Hongdo | Rockfish | September |

| Imjado | Sandfish | May | Heuksando | Skate | May |

| Croaker | August | black rockfish | September | ||

| Docho-do | Marbled Sole | June | Jido | Butterfish | June |

| Anjwado | King Prawn | September | Shrimp Paste | November |

In essence, festivals enhance the attractiveness and competitiveness of tourist destinations, making them a crucial component of sustainable development. A region derives its identity from its residents, while in turn, residents develop their self-identity through their place of living. The integration of these two elements results in a fully realized regional identity.

Shinan County has long relied on its sea and coastal landscapes as its defining features. While some residents engage in agriculture, fisheries and seafood production remain the county’s primary industries. Accordingly, Shinan has traditionally hosted local seafood festivalsas part of its economic and promotional efforts. For many years, Shinan County organized seasonal and regional seafood festivals, selecting signature seafood products and promoting them through events. These festivals effectively boosted seafood sales and strengthened regional branding. However, in order to overcome deep-rooted negative perceptions, a new regional revitalization strategywas needed. The county began searching for new resources and driving forcesto replace outdated images, leading to the creation of a bold new initiative: the “One Island, One Garden” policyunder the theme “Islands Blooming in All Four Seasons.”

| Region | Flower Type | Festival Period | Region | Flower Type | Festival Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imjado | Red Plum Blossom | February | Jeungdo | Thysanostemon | * |

| Tulip | April | Byeongpungdo | Cockscomb | Sep ~ Oct | |

| Seondo | Narcissus | March | Jido | Lilac | Summer |

| Docho-do | Hydrangea | June | Bigeumdo | Rosa rugosa | * |

| Purple Island (Banwol & Bakji-do) |

Lavender | May | Jaeundo | Calanthe | April |

| Verbena | Jun ~ Aug | Shini-do | Myrica rubra | * | |

| Aster | Sep ~ Oct | Haui-do | Rose of Sharon | * | |

| Aphaedo | Camellia japonica | Dec ~ Jan | Palgeumdo | Rapeseed Flower | April |

| Crocosmia | July | Mulberry | * | ||

| Goido | Azania | November | Hongdo | Daylily | July |

As the name suggests, this policy establishes a garden on each island. Shinan County identified unique themes and floral stories for each inhabited island, transforming them into gardens connected to local festivals. By curating island-specific floral festivals, Shinan was able to rebrand itself and offer diverse seasonal attractions. This initiative enabled the rediscovery of Shinan County, replacing its previously negative reputation with a refreshing new image.

For a regional festival to maintain its authenticity, it must be organized, prepared, and performed by local residents (Ryu, 2003). However, Shinan County, as a remote and underdeveloped island region, lacked major cultural or commercial attractions. Thus, new festival resources had to be discovered and developed. During the color and floral selection process for each island, some criticism and skepticismarose. Ideally, a public discussion should have been held to determine what truly represented the region’s identity. However, given the urgent need to overcome the county’s negative image, local leadership pushed the initiative forward decisively. Over time, local residents began to embrace the policy, recognizing its potential to improve Shinan’s public image. As a result, they enthusiastically supported policymakers, allowing the government to mobilize administrative resources swiftly while encouraging private sector participation. This collaborative approach marked a turning point in Shinan County’s economic revitalization.

Regardless of the specific type of resources used, festivals are fundamentally cultural phenomena. Shinan County reinvented its floral-themed festivalsas a means of strengthening community identity and enhancing resident participation through storytelling. A prime example is the “Purple Island” (Banwoldo and Bakjido), which was once an unknown pair of small islands. Through a purple-themed branding initiative, the islands successfully transformed their image. Inspired by the purple hues of native Balloon flowers (Platycodon grandiflorus) and Self-heal flowers (Prunella vulgaris), residents began cultivating purple-themed crops. Shinan County then reinforced the concept by planting over 1.55 million purple flowers, including French lavender, verbena, and asters, to fully establish Purple Island’s identity. This effort gained global recognitionwhen, in December 2021, the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) recognized Purple Island as one of the “Best Tourism Villages”. The island attracted 380,000 visitors annuallyand was featured on major international media outlets such as CNN Travel and FOX News.

Another notable case is Seondo, also known as “Narcissus Island.” The concept originated from a local elderly woman, nicknamed the “Lady of Narcissus”, who loved growing flowers in her village. After moving back to her hometown with her husband, she dedicated herself to planting daffodils, eventually sharing bulbs with her neighbors. Inspired by her story, Shinan County established the Narcissus Festival, linking it to the island’s scenic beauty and cultural heritage. Today, 17 varieties of narcissus flowers bloom across 14.5 hectares of land, with over 2.08 million bulbs planted. Every March, the festival showcases 10 million blooming daffodils, attracting thousands of visitors.

The most distinctive feature of Shinan County’s “One Island, One Garden” policy is its reflection of each island’s unique identity. This initiative goes beyond floral tourism by integrating color marketing with local cultural characteristics. The policy extends beyond gardensto include cohesive color schemesfor rooftops, murals, clothing, and roads, ensuring a visually unified experience. Previously unused spaceshave now been converted into valuable tourism assets. This movement has expanded into a broader initiative, with Shinan County planning 24 themed gardens across its islands, of which 14 have already been established. The successful completion of the ‘cheonsa’ (Angel) Bridge, which improved accessibility, further enhanced the project’s visibility and promotional impact. The post-pandemic shift in travel trends have also worked in Shinan’s favor. As eco-friendly, wellness tourism gains popularity, outdoor travel has increased, driving interest in hiking, cycling, and nature-based experiences. Shinan County has become a prominent destination for travelers seeking serene, healing environments, further reinforcing its regional branding success.

The success of Shinan County’s floral festivals demonstrates that festivals are not merely cultural events, but key drivers of regional development. Recognizing this, Shinan has begun developing new festivals using local resources, ensuring that they serve as differentiating factors that enhance regional competitiveness. Festivals play a crucial role in place branding, creating economic opportunities, boosting tourism, and generating diverse added-value industries. To truly understand festivals, one must analyze how cultural symbols are formed and how cultural values are created through these events.

While flowers served as the foundation of Shinan’s rebranding, the county’s broader vision prioritized biodiversity conservation and sustainable ecological development. The “Flopia 1004 Islands” initiative, emphasizing Shinan’s environmental assets, has significantly contributed to shaping a positive regional image. Most importantly, this initiative empowered local residents, leading to the formation of Korea’s first Social Cooperative for Garden Tree Cultivation (2023). The cooperative created jobs, supported community-driven garden maintenance, and integrated tourism resources into the local economy. In its first year, the cooperative produced 310,000 tree saplings, saving the county 8.3 billion KRW while generating 1.5 billion KRW in income. In 2024, production increased to 1.38 million saplings, saving 50.6 billion KRW and raising 8 billion KRW in earnings for residents. By fostering organic collaboration between public and private sectors, Shinan County has successfully transformed its image, revitalized its economy, and created a sustainable model for regional tourism and development.

4. Conclusion: Reconstructing Island Identity—From Stigma and Wounds to a Culture of Recognition

The concept of place can refer to a geographical location or to an individual’s sense of belonging or attachment to a specific environment. Anderson (2009) described this as “cultural traces.” Places contain unique imprints shared by the people who inhabit them, and these shared traces play a fundamental role in shaping their collective identity.

“Purple Island” represents the first successful case of island revitalization through color marketing. The combined population of Banwoldo and Bakjido, which constitute Purple Island, is only around 135 residents, a stark contrast to the over 700 residents recorded in the past. However, due to urbanization and industrialization in the 1980s, nearly 80% of the population migrated to the mainland, leaving behind an aging population, most of whom are now in their 60s or older.

In 2019, efforts to transform the entire village with the color purple began. Drawing inspiration from the naturally growing balloon flowers (Platycodon grandiflorus) and self-heal flowers (Prunella vulgaris), which bloom in shades of purple, the community actively participated in planting and cultivating flowersto create an island that blooms in purple hues throughout all four seasons. As part of Shinan County’s “One Island, One Garden” policy, residents directly engage in preparing floral festivalsby planting and maintaining gardens themselves. Regardless of the festival’s commercial success, locals express joy and pride simply from seeing visitors come to their island. Those who have actively participated in festival preparation have witnessed firsthand how the island’s image has transformed. This case study provides insight into the sustainability of small island communities facing population decline and regional extinction.

Recently, storytelling strategies utilizing regional cultural resources have gained recognition as effective tools for shaping local identity. However, the key challenge lies in determining what stories to tell, who should tell them, and how they should be conveyed. Instead of government officials simply painting rooftops, true community engagement requires residents to take an active role in maintaining gardens, dressing in colors corresponding to their village’s theme, and aligning their actions with color marketing strategies. Shinan County’s approach to planning and executing festivals involved the local municipal leader taking on the role of a storyteller, persuasively engaging both internal and external stakeholders. Over time, the floral festival narratives have been embraced and executed by local residents themselves.

As Shinan County overcame its historical disadvantages through floral festivals, the visionary leadership of its local governmentwas complemented by the enthusiastic participation of residents, who managed both their daily livelihoods and festival preparations simultaneously. As festivals continued to enhance the region’s image, residents developed a stronger sense of pride and identity—not only in their island community but also in their active role as festival hosts. This case demonstrates that small-town branding can be an effective strategy for addressing regional extinction, and when residents actively participate, it can also contribute to broader social progress.

The ultimate goal of local branding is to identify and highlight the unique values of a region, solidify its identity, and differentiate it from other regions. However, if the local identity promoted by the government significantly differs from how residents perceive their own region, the branding effort may fail to gain local support, preventing meaningful change. Branding should not be a superficial exercise imposed from the top down; rather, it should be a commitment to preserving and promoting the region’s cultural values. When local resources are discovered and developed, they must be acknowledged, embraced, and actively disseminated by the community for true transformation to occur. Moreover, people from the mainland should no longer view islanders through a lens of prejudice and stigma. Instead, they should recognize island residents as they truly are—people with diverse island cultures and distinct regional identities.

Overcoming Isolation and Stigma: The Recognition of Island Communities

For a long time, island residents, living far from central governance, have been marginalized in policy implementation and excluded from national welfare benefits. Traveling to the mainland requires expensive transportation costs. Logistics expenses increase the cost of living. Healthcare and cultural experiences remain largely inaccessible. Islands have been unfairly stigmatized as hubs of crime and social disorder. For decades, islanders faced discrimination and bore the emotional wounds of social exclusion. However, today, they seek to move beyond past grievances and instead assert themselves as the key players in reshaping their region’s image. No longer passive victims, they actively engage in community-driven transformation.

The Role of Place in Identity Formation

A placeis not merely a physical location; it is where human life unfolds, both existentially and socially. For islanders, place becomes meaningful through their experiences and interactions, shaping their place identity. Simultaneously, their identity is shaped by the unique characteristics of their island environment. This study has examined how local festivals have been strategically employed to reshape the image and identity of islands, shedding light on the politics of identity within these communities.

The image of islands is fluid, evolving with societal and historical transformations. In the past, islands were perceived as spaces of isolation and closure. Today, islands are emerging as centers of communication and openness.

“Angel Island” and “Purple Island”: More Than Just Image Rebranding

The branding of “Angel Island” (Cheonsa-seom) and “Purple Island” (Bora-seom) is not merely a superficial attempt to change an island’s image; it represents a fundamental transformation in economic and social structures. By leveraging branding as a catalyst for economic revitalization, Shinan County has effectively redefined its identity.

Moving forward, sustainable development will require a balanced approach that respects island identity while simultaneously working to overcome historical stigma and marginalization. A strategic image-making process—one that transcends past wounds and cultivates a culture of recognition—will be essential for the long-term prosperity of island communities.

However, above all, island regions are often marginalized in policy-making or treated through a mainland-centric perspective. Therefore, island studies must reflect the voices of island residents and move beyond purely geographical inquiry to become a platform for interdisciplinary and integrative research (Baldacchino, 2006). Furthermore, it is essential to remember that, following the concept of Nissology, islands should be studied “on their own terms” and viewed from the perspective of the islands themselves (Kakazu, 2021).

Endnotes

- The ‘Cheonsa Island’ CI was trademarked and created in 2013. However, after a change in local government following the 2014 election, it was discarded for four years. It was officially reinstated and put back into use in the second half of 2018.

- The Shinan Salt Farm Slave Incident is as follows: Persons with intellectual disabilities, identified as A and B, were employed at a salt farm in Shinan County through a job placement agency. However, they were subjected to harsh physical labor, getting less than five hours of sleep per day. For five years and two months, they were forced to work without receiving any wages, enduring conditions of involuntary servitude. Unable to withstand the abuse, the victims attempted to escape three times, but each attempt ended in failure. Desperate, they secretly wrote a letter and carried it with them until they found an opportunity to send it to their family without being detected. The mother, upon receiving the letter, immediately informed the police, leading to their dramatic rescue. This case became a major social issue at the time, particularly because a cartel-like silence existed among the residents of Shinan County, preventing anyone from reporting the oppressed “island slaves” to the authorities. Instead, their rescue was orchestrated not by the local police but by a missing persons investigation team from Seoul, who conducted an undercover operation to locate and free the victims. This incident significantly contributed to the negative perception of Shinan County. Based on this Salt Farm Slavery Case, the film "The Island: Missing People" was produced in 2016 to depict the tragic reality of forced labor on remote islands.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A6A3A01109908)

References

- Agius, K., Theuma, N., Deidun, A., Camilleri, L., 2019. Small islands as ecotourism destinations: A central Mediterranean perspective. Island Studies Journal, 14(2): 115–136.

- Anderson, J., 2009, Understanding Cultural Geography, Places and Traces, London: 1-240

- Ahn, H.W., 2009, On a Way of Vitalizing Local Festivals of Chung-nam: Focusing on the Successful Elements, Journal of Chungcheong Regional Studies 2(1): 151-175.

- Baldacchino, G., 2005. ‘Islands — Objects of Representation’, Geografiska Annaler, 87(4): 247-251.

- Baldacchino, G., 2006. Islands, island studies, island studies journal. Island Studies Journal, 1(1), 3–18

- Baldacchino, G., 2008. Studying Islands: On Whose Terms? Some Epistemological and Methodological Challenges to the Pursuit of Island Studies, Island Studies Journal, 3(1): 37-56

- Baldacchino, G., Stratford, E., & McMahon, E., 2022. Doing island studies: A methodology primer takes shape. 18th islands of the world conference—islands: Nature and culture(P.94). Book of Abstracts.

- Conkling, P., 2007. On Islanders and Islandness. Geographical Review, 97(2): 191-201.

- Depraetere, C., 2008. The challenge of nissology: A global outlook on the world archipelago — Part I: Scene Setting the World Archipelago, Island Studies Journal, 3(1): 1-16.

- Depraetere, C., 2008. The challenge of nissology: A global outlook on the world archipelago — Part II: The global and scientific vocation of nissology. Island Studies Journal, 3(1): 17–36.

- Goffman, E., 1963, Stigma : notes on the management of spoiled identity, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prentice-Hall. 1-147.

- Grydehøj, A., 2017. A future of island studies. Island Studies Journal, 12(1): 3-16.

- Hay, P., 2006. A phenomenology of islands. Island Studies Journal, 1(1): 19–42.

- Hong, S.K., 2010. Biocultural diversity and traditional ecological knowledge in island regions of Southwestern Korea, Journal of Ecology and Field Biology, 34(2): 137-147.

- Hong, S.K., 2022a. Topical Islandness. Mokpo: Publisher Seom (Korean), pp. 8-14.

- Hong, S.K., 2022b. Changes in the Island Humanistic Topography and the Island Identity due to Global Environmental Changes : Focused on the Ecological-cultural Background and Methodology, Journal of Cultural Exchange and Multicultural Education, 11(2): 417-441.

- Hong, S.K., 2023. Biocultural Diversity and Islandness: On human geographical and typological approaches, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 12(3): 1-13.

- Hong, S.K., Pungetti, G., 2012. Marine and Island Cultures: A unique journey of discovery. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 1(1): 1-2.

- Kang, S-G., 2024. An Experiment in Regional Tourism Collaboration: The Kang Hae-young Project. KOREA TOURISM POLICY Summer, 96: 4-9.

- Kakazu, H. 2012. Island Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities for Okinawa and Other Paci c Islands in a Globalized World; Trafford: London, UK. 1- 297.

- Kakazu, H., 2014. An Introduction to Nissology-Definitions, Approach and Taxonomy-The Journal of Island Studies, 15 : 95-114.

- Kakazu, H., 2021. Nissology: A Study of Island Sustainability focusing on the Islands of Okinawa, NextPublishing Authors Press. 1-315.

- Komppula, R., Lassila, H., 2015. Co-creating tourism services—a multiple case study of methods of customer involvement in tourism. In Tourism and leisure (pp. 287–303). Springer Gabler.

- Ledwell, J., 2002. ‘Afraid of Heights, not Edges: Representations of the Shoreline in Recent Prince Edward Island Poetry and Visual Art’, Presentation to ISISA Islands of the World VII International Conference, University of Prince Edward Island. 1-13.

- Maffi, L., Ellen, W., 2010. Biocultural diversity conservation-A global sourcebook. earthscan, London. Terralingua and IUCN : 1-304.

- McCall, G., 1994. Nissology: The study of islands , The Journal of Pacific Society, 17(2-3):1-13.

- McCall, G., 1997. Nissology; A Debate and Discourse from Below, In Presented at Cultural Heritage in Islands and Small States Conference. Valletta, Malta, 8-10.

- Ryu, J. A., 2003. Festival Anthropology. Sallim Publishing. Korea. 1-94.