“Much more than a tourism product!”: Insights into the people–sea relationship using photovoice

Abstract

This article presents the results of an exploratory photovoice study aimed at gaining deeper insights into participants' connections with the marine environment living on Andros Island, Greece. Evidence reveals a range of values, largely framed through a relational perspective. The relationship of participants to the sea is strongly characterized by aesthetic appreciation, a strong sense of place and identity, health benefits, connection to nature and others, knowledge about nature and gain of perspective on life. Expressions of emotions are also central in participants’ narratives and provided photographic material. Marine dependency with regards to livelihoods is mainly centered around island’s shipping tradition, and tourism, which is intertwined with the future of the island, while mixed reactions to fishing are noticed. The likely implications of this relation to the marine environment, especially in terms of motivating and engaging citizens in care and marine management, are discussed.

Keywords

emotions, marine and coastal environment, Mediterranean Sea, photovoice, quality of life, values

Introduction

The need to protect our marine environment and deepen our understanding about our connection to the sea is becoming more and more eminent. Challenge 10 of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) calls for creating a wide consensus on understanding the multifaceted contribution of the ocean to our lives and prosperity, while promoting behavioral change and redefining our relationship with the ocean[1]. Similarly, the European Ocean Coalition (EU4Ocean)[2] initiative supported by the European Commission, aims to contribute to ocean literacy and hence, to responsible choices, sustainable management and overall, human wellbeing.

Furthermore, European policies for the management of the marine environment (i.e., Marine Strategy Framework Directive, Maritime Spatial Planning Directive), call for the adoption of an ecosystem approach. To address the complexity and interdependencies inherent in marine ecosystems, a systems approach has gained prominence in the academic discourse (Judd and Lonsdale, 2021), which also recognizes the multifaceted nature of the marine ecosystem services. The concept of ecosystem services links the science of ecosystem processes and functions to changes in human wellbeing (Böhnke-Henrichs et al., 2013). However, exploring their value and importance seems to require a flexible approach in terms of adopted definitions, value concepts and methods. For example, existing classification systems of cultural ecosystem services (CESs) might need to be adapted to the local setting (Gee et al., 2017), while the collaboration of methods from different social sciences might be necessary (Chan et al., 2012). Furthermore, deliberative methods may seem more appropriate for concepts of value which are not pre-formed (Kenter et al., 2016a), and have more social and shared dimensions, rather than individual (Kenter et al., 2016b).

In this challenge of identifying suitable forms of value expression to capture the importance of nature beyond instrumental and intrinsic contexts, relational values offer the perspective to reflect on nature in terms of responsibility and relationships that stem from our interaction with it that make a good life (Chan et al., 2018). This process has brough together diverse academic perspectives across social sciences and humanities and offers ground for qualitative methods (Chan et al., 2018). These could work complementary to quantitative and enable a better understanding about connections between people and nature to inform policies and management strategies.

In this article, we present a participatory non-market valuation method called photovoice, used as an open-ended non-prescriptive way to explore perceptions of the marine and coastal environment from participants living on Andros Island, Greece. By using photovoice and visual data we expected to acquire diverse and inner information (Harper, 2002), as photographs can communicate complex issues in a different way than words. Furthermore, art-based methods can potentially highlight relational values as in Acott et al. (2022). Identifying various connections to a specific environment and place deepens our understanding and makes those connections visible for purposes of marine policy, planning, social transformation and behavioral change. Furthermore, the study adds to the overall limited literature and research on sociocultural dimensions of the marine and coastal environment (Gee et al., 2017; Saunders et al., 2020). It also provides evidence to the limited use of arts-based techniques in the field of social sciences exploring public ocean perceptions (Jefferson et al., 2021), and to the use of photovoice in exploring interactions between people and environments (Bennett and Dearden, 2013). Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, in Greece only Kalaitsidaki et al. (2022) have employed the specific method in a similar context, but with a focus on the urban environment.

In the next sections, we present the case study area and provide an overview of the photovoice research method. Then, the article offers insights into the rich narratives revealed by participants, accompanied by photographic material. Reflections on potential implications of findings are presented in the discussion section, before summarizing key conclusions.

Case Study

Andros island in the Aegean Sea, is an area of 380 km2, having a population of 9,221 people (2011 Census), which reaches 40,000 during summer (NCC, undated). Andros is mainly characterized as a domestic tourism and second-home destination, rather than one of mass tourism (Terkenli and Georgoula, 2022). Furthermore, ecotourism activities, such as hiking, define the island's character, offering a gentle illustration of ‘blue growth’. Overall, apart from tourism, that seems to be in line with the future economic development of the island, other main productive sectors of the island are shipping[3] and farming, while other activities include fishing (mainly small-scale fisheries) and beekeeping (NCC, undated). Most people are employed in the tertiary sector (57,64%), where accommodation and food services employ 10.24%, while 15,48% are employed in the primary sector, where fisheries account to about 0.8%. (EL.STAT, 2011).

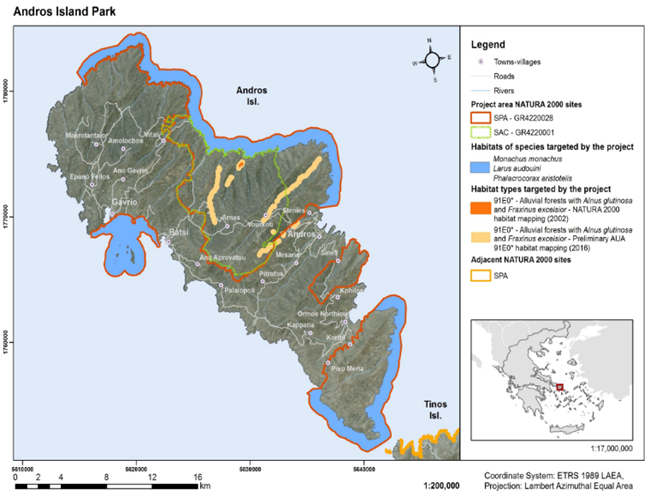

Our study took place during the LIFE Andros Island Park[4] project, that included a wide array of activities for the conservation of the island’s protected areas (Figure 1). Andros’ marine area is one of the most important areas for seabirds (e.g., Mediterranean Shag and Audouin’s Gull), marine mammals (e.g., Mediterranean monk seal), and habitats (e.g., Posidonia beds and reefs[5]). In addition, Andros is characterized by art attractions and a rich cultural heritage and landscape, including archaeological sites and monuments, monasteries, drystone terraces, windmills etc.

Methodology

Visual Research

We employed visual arts-based methods and photography through a participatory photovoice process, where participants were asked to take photos interpret and reflect on them, in a setting that encouraged group discussions (Wang and Burris, 1997).

Researchers have used photography in marine and coastal contexts to document the environment, deepen understanding of values, relationships, and worldviews, highlight changes, raise awareness, create cultural values, and co-produce knowledge (Acott and Urquhart, 2015; Bennett and Dearden, 2013; Khakzad and Griffith, 2016; Simmance et al., 2022; Strand et al., 2022; Thomas et al., 2020). Furthermore, social media and geodetic photos constitute free access secondary data that can be useful in mapping and assessing the importance of human relationships with the environment (Oteros-Rozas et al., 2017).

Creative practice, and visual arts-based methods, demonstrate strengths in offering a different medium, instead of traditional individual or group interviews, to participants of experiencing reality and sharing their insights (Leavy, 2020). In this context, there is potential for deliberative arts-based approaches to knowledge and futures creation for management purposes (Strand et al., 2022), and overall arts to contribute in different ways to coastal and marine sustainability (e.g., by raising awareness, promoting engagement, addressing issues) (Matias et al., 2023). Generally, there is a wide potential for art and science collaboration on environmental issues (Saratsi et al., 2019) and an important role for the methods used in arts and humanities for example, in enabling consideration of CESs (Coates et al., 2014) and understanding of ecosystems’ values alongside most employed methods (Edwards et al., 2016). Finally, initiatives such as the New European Bauhaus[6], endorses art, culture, and creative activities, and calls to “build together a sustainable and inclusive future that is beautiful for our eyes, minds, and souls”.

Research Procedure and Analysis

In total, seven island residents were recruited through snowball sampling, including participants from Chora (1), Gavrio (4), Livadia (1), and Messaria (1). The group consisted of three men and four women, ranging in age from 37 to 65 years. All apart from one were working full-time, and their professions were related to the tertiary sector (other than tourism), while two to the primary. Two workshops were conducted, one in June and another in July 2022. In the initial online workshop, we outlined the goals of the project and provided instructions on capturing photos, complying with photography ethics. the right to withdraw, usage of the provided material, confidentiality concerns, and the signing of consent forms. Additionally, participants were introduced to the central study question: “How does the marine and coastal environment affect your personal quality of life?”

Participants were given two weeks to capture up to ten photos using either a mobile phone or a camera, with periodic check-ins. They also had the option to present older photographs that represented the subject and were asked to write captions and note the location for each image. The participants contributed a total of 33 photographs.

The second workshop took place in Andros, beginning with team-building experiential exercises designed to help participants feel comfortable expressing themselves. These exercises also aimed at engaging those with different learning styles and illustrate the power of habitual thinking, highlighting how quickly people can move from forming assumptions to taking action. Effective listening and experiential activities emphasized the importance of nonverbal communication and listening to understand rather than debating.

After these introductory activities, each participant presented their photographs and accompanying interpretative text to the group. Facilitators posed questions like, “What do we see here?” and “Why did you take this photograph?” Participants were encouraged to interact during individual presentations and engage in collective discussions, sharing experiences, memories, emotions, visions of the future, and commenting on each other's photos.

Finally, participants were asked to reflect on their photovoice experience. They collectively agreed to publicly share their photographic material through a community exhibition at Agadaki Estate in Andros, which began in September 2022 and continued for several months. With participants' consent, we recorded all sessions, including individual narrations and group discussions, then transcribed, organized, and coded the data using NVivo12 software.

Throughout this article, the term 'marine' is used to reflect a holistic view of the sea, encompassing everything from the coastline to the open ocean. Furthermore, the focus of the current study is on the breadth and depth of the qualitative data, and results are meant to be indicative, as they are based on participants’ subjective experiences. Finally, a selection of the images is presented here, along with their provided captions. Pseudonyms have been used for those participants that wished to keep anonymity.

Results

Overall, contributing photos demonstrated participants’ deep caring for the sea, revealing strong relational values but also other intertwined value concepts, following Chan et al. (2018) overview of relationships between these concepts. Photographs also revealed preferences for particular features in the marine environment as seen mostly from the shore, underwater, or at sea. Figure 2 presents examples of different perspectives of viewing the marine environment (e.g., from close, from a distance, with less or more human intervention). Participants approached their ‘subject’ in various ways, for example to document reality, or by adopting a more artistic or symbolic representation. From the 33 photos, 14 photos made a reference to human interaction without showing people, eight photos showed people in or by the sea involved in various activities, while there were seven photos in which human presence was completely absent and mainly depicted “non touristic” shores of “wild beauty” as commented by several participants. Notable is also the presence of tangible cultural elements such as lighthouses, ports, the Venetian castle and tower, fishing and sailing boats, churches, temporary structures (e.g., huts), coastal settlements. Finally, one participant attempted to capture tourism’s negative aspects, while another group of photos included sea life, for example birds, shells, remains of fish and other marine organisms (e.g., crab, urchins).

|

|

| a) Moments of happiness under the water, the hand caresses the sea fields. Location: Apothikes beach. Credits: Sylvia | b) In the fairy tales of time. Location: Batsi. Credits: Dimitra Milaiou |

|

|

| c) Looking from the hut. Location: Blichada beach. Credits: Martha | d) The greatest, the most beautiful time... the time of coming back. Location: On the ferry yesterday, return to Andros. Credits: Sylvia |

Participants’ Perspective on Quality of Life

The photovoice exercise provided a platform for in-depth discussions, enabling us to comprehend how the marine environment affects participants' quality of life. Below, we outline the primary categories that surfaced during the process, as per our analysis.

- Aesthetics and emotional experiences

- Sense of place: identity, belonging, attachment, memories

- Human health, physical and mental

- Connection to nature

- Connection to others

- Knowledge

- Reflection, gain perspective on life and world

Aesthetics and Emotional Experiences

Aesthetic aspects and emotional experiences were among the themes with the most references. Selection of photos is presented in Figure 3. Narratives touched upon the colors of the sea, its vastness, its condition (e.g., calmness), dramatic skies, wild, “captivating shores”, and views “pleasing to the eye”, but also picturesque scenes from the ports of the island. Other expressions of appreciation included for example “the wonders of nature”, “the beauty of simplicity”, “scenes of poetry”, seascapes resembling “Dutch paintings”.

|

|

| a) Wild beauty. Location: Plaka beach. Credits: Georgia | b) Wonderful colours. Location: Lefka beach. Credits: Martha |

|

|

| c) When the blues come together. Location: Chora. Credits: Dimitra Milaiou | d) Winter evening. Location: Chora. Credits: Dimitra Milaiou |

An important part of participants’ narratives made references to emotional experiences. Positive feelings included peace, balance, pleasure, happiness, excitement, inspiration, awe, hope, freedom, love and respect. Other feelings included surprise and curiosity through unexpected encounters (Photo a, Figure 4), as well as feelings of excitement, experiencing special moments for example, the sight of flamingos or the coexistence of river and sea elements (Photos b,c, Figure 4). The relationship between the coast and wellbeing of residents through the prism of emotional experiences was also evident in Severin et al. (2022).

|

|

| a) Fish on the shore: even so the power terrifies. Location: Achla beach. Credits: Sylvia | b) Vori beach. Credits: Costas |

|

|

| c) Pink flamingos. Location: Gavrio. Credits: Costas |

Most references to aesthetics were positive, triggered by photos related to unspoiled, wild, remote seascapes, demonstrating a strong attachment to these places, many of which fell within Natura sites. However, negative references were also made (as in Acott et al., 2022; Buchan et al., 2024a; Kaltenborn et el., 2017), related to interventions for touristic reasons creating cacophony (e.g., beach furniture, beach bars, planting trees not related to the native flora). Other negative feelings emerged by the sea being stormy, tense, unpredictable, hiding risks and stimulating thoughts of nostalgia and worry, related to beloved ones (sailors, captains) traveling overseas, or sadness about these who have passed away on one of these journeys.

An interesting point was made by one participant, with regards to the power of positive emotional human-sea connections, through aesthetic experiences, creating a deep appreciation of the marine environment, instilling environmental conscience, and caring that could mobilize people for its protection.

“when you see something nice you want to have the possibility to continue enjoying it, so you become more sensitive, you acquire an environmental consciousness and you start taking action …to me quality of life and marine environment are synonymous” (Anthony, male, age: 40s)

A similar argument related to aesthetics’ appreciation and its impact, was made by another participant, while justifying her preference towards shooting in an aesthetically pleasing way.

“you may think that my photos are meant to beautify, but I personally like taking photos of beautiful aspects, because by seeing ‘beauty’ when you notice something ugly you will be able to appreciate the true beauty of things” (Dimitra, female, age: 40s)

Sense of Place: Identity, Belonging, Attachment, Memories

Sense of place has been applied more in terrestrial ecosystems followed by marine (mainly coastal) and then freshwater (Duggan et al., 2023). Regarding marine activities, although all participants acknowledged the shipping maritime identity of the island[7], most of them also raised in seafaring families, narratives regarding small-scale fisheries importance differed between them. Participants from the western side of the island argued that Gavrio had always a fishing tradition preserved till today[8]. It was also noted that places on the western side (e.g., Batsi, Gavrio) used to be fishing villages before tourism development and people were mainly engaged in the primary sector. For most participants from Gavrio, the value of fisheries was focused on access to fresh fish (“the sea is wealth”, as Martha (female, age: 30s) emphasized), while a cultural value was also assigned to the activity, demonstrating that fishing is more than an economic activity (Stithou et al., 2022). However, changes over time were also observed, including a decrease in fish population compared to previous years, reduced economic reliance on fisheries, and a growing emphasis on tourism, transforming the character and cultural landscape of these areas.

On the other hand, participants from the eastern side of the island and in particular from Chora and within proximity, did not think that the island has a relatively strong fishing identity[9]. These differences were also evident in participants’ photos, as well as in their narratives regarding dietary habits and fish consumption. Overall, participants emphasized sociocultural variations between east and west related to the history of the island and the different origins of its residents, as well as weather conditions that may favor fishing more on the western side of the island.

Nevertheless, all participants agreed that there is a strong personal occupational identity of people working at the sea[10]. As one participant stressed, even when contemplating retirement, their dream was to continue being by the sea.

“my husband was a sailor and till the last day we spoke before I lose him [he died] while in Brazil, he told me, “I want to come back and buy a boat like the one which is in the middle of Gavrio so I can go fishing”… my brother who works at the sea [mechanic at a ferry] has the same dream” (Georgia, female, age: 60s)

Furthermore, members of sailors/mariners’ family had also developed a special connection to the sea, as explained by one participant whose father died in one of his travels.

“You love and respect the sea differently having grown up in a seafaring family, you understand much more about the hardships and risks, and you realize that it does not make a difference if you are on a big ship or a fishing boat” (Martha, female, age: 30s)

Similarly, as Sylvia (female, age: 60s), who also come from a seafaring family, emphasized that because of that, “the sea is within us”, and that it is not even necessary to have a sea view from home to feel the connection. Relevant references also encompassed the captains' tradition of sounding their horns while passing Andros to greet their loved ones, as well as the 2013 film ‘Little England’[11]. The film captured the shipping culture of Andros, that shaped Andros’ social, family and gender relations, also evident in some of our participants’ narratives.

“when our dad was traveling for long time, over three years, my little sister when the phone rang was shouting ‘its dad!’ instead of ‘the phone is ringing!...as for myself, my dad is still traveling [although he has passed away]” (Dimitra, female, age: 40s)

Participants also used expressions that declare strong place attachment such as, “the island is my whole life” (Costas, male, age: 30s) and deep emotional connection with anthropomorphic references, such as, “the sea is the soul of the island” (Martha, female, age: 30s). Furthermore, a connection to the sea beyond specific locality, as in Buchan et al. (2024a), was strongly expressed by Costas, while justifying his decision to come back to Andros (“I could not live away [from the sea]”). Similarly, another participant characteristically expressed her anticipation every time she arrives in Andros (Photo d, Figure 2) and hence, the strong attachment to the place and the sense of belonging.

Socio-cultural tangible heritage was also strongly related to the place identity. As one participant pointed out:

“when you see these photos [showing ‘Tourlitis’ lighthouse in Chora] you know exactly where that place is” (Dimitra, female, age: 40s)

The two lighthouses, one in Chora and the other in Gavrio, were presented as ‘trademarks’, intertwined with places’ identity. Participants attributed to the lighthouse notions of protection, direction, anticipation of getting reunited with the beloved ones traveling away. They were also perceived as a reference point of departure or return, a geographical point of demarcation between land and sea (i.e., Tourlitis lighthouse in Chora), they also infused a sense of ‘companionship’ by seeing the light on during the night, but also a nostalgic sense of longing for “the trips we have dreamed of” as Dimitra emphasized (Photo c, Figure 5).

Other examples of tangible cultural heritage and build elements that seemed to contribute to place identity and to also show continuity across history on the island, was the Venetian castle in Chora, the nearby memorial statue for the sailors, the old port of Chora, the Venetian tower at the northern side of the island (Figure 5).

|

|

| a) The lighthouses of the trips we dreamed of. Location: Tourlitis lighthouse, Chora. Credits: Dimitra Milaiou | b) Emerald sea. Location: Ateni. Credits: Georgia |

|

|

| c) The castles of lost paradise. Location: Niborio beach, Chora. Credits: Dimitra Milaiou | d) The seagulls are approaching the fishing boat. Location: Kipri. Credits: Georgia |

Many of the places in the photos brought happy memories from participants’ childhood and demonstrated a continuity across generations, as most participants keep on visiting and enjoying the same places till today even with new members of their family. However, as mentioned before, at the same time for certain people, especially for women left behind, the coast has been transformed to “memorial space” of absence or loss as in Pafi et al. (2023: 28). In this case, the sea and the coast were referred to as a place of memory and connection to the absent family member, to such an extent that have also acquired a spiritual dimension, as strongly expressed by a participant.

“knowing that my dad was at the sea [being an oversea sailor], the closest way to ‘reach’ him was to get also in the sea, so no matter in which shore I was, I had always the tension to get into the sea, to swim, to feel connected” (Martha, female, age: 30s)

Physical and Mental Health

Activities intertwined with the lives of participants were swimming, fishing (from the boat, spearfishing), walking, doing water sports, relaxing on the beach (Figure 6). Although physical benefits related to certain activities were acknowledged, being at the sea was strongly commented on by all participants in terms of mental benefits (as in Acott et al., 2022).

“The sea calms me down, relaxes me, whatever you have [worries], if you stay for a while by the sea, it goes away, you forget about it” (Costas, male, age: 30s)

Τhe coast and the sea could work as a “therapeutic landscape” linked to emotional restoration as noted in Severin et al. (2022: 2), while marine sites have a “therapeutic value” contributing to human wellbeing (Bryce et al., 2016: 262), also associated with the sense of freedom. The latter was perceived by one participant who conceived the vastness of the sea as offering numerous pathways to follow.

“to me the sea is connection, you can get on a boat and go wherever you want, wherever there is sea you can go” (Martha, female, age: 30s)

|

|

| a) Balance between life and nature. Location: Gavrio. Credits: Martha | b) Our living memories. Location: Paraporti beach, Chora. Credits: Dimitra Milaiou |

|

|

| c) Always remain a child. Location: Niborio beach, Chora. Credits: Dimitra Milaiou |

Connection to Nature

The psychologically restoring and rejuvenating experiences mentioned above were closely related to the direct ‘personal’ connection to nature involving different senses and experienced in different ways by participants. Examples of sensory experiences included sights, as described above under aesthetics theme, taste (e.g., fresh seafood), touch (e.g., feeling the underwater flora, the sand), sounds (e.g., lulled by the sound of the waves, the sound of seagulls) and the smell of the sea.

“you experience the awakening of the senses when you are in or next to sea water” (Dimitra, female, age: 40s)

“[the sea] invites you, to savour nature…to be close to it so that it becomes part of you, if I could swim all year round, I would do it for sure” (Martha, female, age: 30s)

Martha also added that, “one needs to be receptive to savour nature”, implying a precondition that could potentially be constructed. Another participant linked quality of life and working environment, through his own experience as a beekeeper.

“it’s different to open your window and see concrete and it’s different to see this [Photo a, Figure 7] … what can I say? Nothing compares to it” (Thomas, male, age: 40s)

As a result of a wider acknowledgement of the benefits of being close to nature and the link to wellbeing, Thomas also mentioned local efforts to attract people that work remotely. Furthermore, three of our participants have decided to leave Athens and two to share their lives between Athens and Andros because of the quality of life. Specifically, one participant explained that her decision was related to her wish to have a family and bring up her children on the island. This would offer them the possibility to experience childhood the same way she and her mother did, close to nature harnessing the benefits of this connection (Photo b, Figure 7).

|

|

| a) Morning view from the office. Location: Peza beach. Credits: Thomas | b) Growing up by the sea. Location: Gavrio. Credits: Martha |

Connection to Others

Most of the participants valued the importance of the marine environment in terms of experiencing and building social relationships as in Acott et al. (2022). For example, enjoying the sea was an opportunity to meet up with family and friends, create bonds especially with young family members, but also socialize with other people (examples in Figure 8). This also became obvious through photos depicting familiar persons by/at the sea. Furthermore, it is noted that the importance of social experiences by the sea is also linked to people’s sense of place formation (Poe et al., 2016), showing the ‘overlapping’ benefits of taking joy being at the sea.

|

|

| a) The seas that travel our thoughts. Location: Chalkolimiona beach, Stavropeda. Credits: Dimitra Milaiou | b) Taking a boat trip at the port. Location: Gavrio. Credits: Martha |

Knowledge

Some participants commented that through their interaction with the marine environment and due to their interest and observation, they learned more about nature. Similar benefits related to visits to the natural environment have been reported in Natural England (2017). In our study, examples included mainly certain behaviors of birds, but also knowledge about the presence of important coastal ecosystems (e.g., wetland, sand dunes) and coastal and marine flora (e.g., Achillea maritima, seagrass Posidonia oceanica, endemic to the Mediterranean Sea).

Reflection, Gain Perspective on Life and World

Noticing the interaction between sea and land, the rhythms of nature and human’s existence, provoked various thoughts regarding life values and human presence in the grand scheme of the world and hence, further “relational forms of being” as in Game and Metcalfe (2011: 43). These were mainly demonstrated by two participants. Thoughts were related to the power of nature, the disproportionate footprint that we leave altering in short time the seascape compared to natural processes, as well as a reassessment about what matters in life, as in Severin et al. (2022). That was particularly evident in the following two photos and respective narratives (Figure 9).

“this a very characteristic rock on the beach of Plaka that shows how nature itself interacts …the water with the rock through time, and I think it shows in a very good how many years it has taken for this to be done by nature, in relation to the years we have been here and our impact on respective places” (Martha, female, age: 30s)

“To me this [photo b] is the beauty of simplicity, it is happiness that’s why I have chosen these lyrics as a caption … I think man needs nothing more than this to be happy, a shelter and something to eat” (Sylvia, female, age: 60s)

|

|

| a) Plaka, wild beauty. Location: Plaka beach. Credits: Georgia | b) ‘…all we need is a wave and a house, a little lone house on the shore[12]. Location: Plaka beach. Credits: Sylvia |

Finally, informants were asked to chose a title for the photo exchibition and the “The sea is road” seemed to be favoured by the most. Other suggested titles that demonstrated the emotional connection and relational value to the sea, included “The sea, our world”, “The sea shows us the way”, “The sea is within us”[13], “The embrace of the sea”. The latter revealed a motherly affection and a contrast, how can something so fluid embrace the world, as noted by Dimitra.

Visions of the Future

Regarding the future of the marine environment of Andros, participants expressed non-use bequest values and the wish for future generations to have the chance to experience similar experiences to theirs. One participant attempted to capture this in a photograph with seashells and other marine species collected from a beach in Gavrio (Figure 10).

“I would like that these [findings] excite my children and future generations the same way that excite me…I think my mom instilled this [connection] to me, it’s like a chain” (Martha, female, age: 30s)

|

| Collecting shells on the beach. Let's make sure that future generations find them too. Location: Fanari, Gavrio. Credits: Martha |

Another participant while describing his photo of a well-known beach, where important coastal ecosystems are present in the same area as a beach bar, contested the prevailing economic model of growth that commodifies the coast for tourists’ pleasure, as in Ounanian (2019). He also strongly disapproved of the tourist development without limits and quality standards, and the lack of incentives in promoting the self-sufficiency of the islanders linked through time to their sustainability.

“I can't understand why we must ‘touristize’ everything, all the beautiful beaches … and I am wondering what we will hand over to future generations? because we ‘sell up’ for today, for us to have all these that accompany our civilization … I would like that there are some beaches that future generations can experience the sound of the sea and the seabirds, the smell of the sea, the sense of the stone and the sand, to enjoy the stars without artificial lights” (Anthony, male, age: 40s)

As also found in Severin et al. (2022), for some people tourism may create dis-benefits in reversing the sense of calmness and relaxation and connection to nature that the coast can trigger. Similarly, in Pafi et al. (2023) some members of the local community expressed the need for managing tourism pressure.

Overall, participants agreed that tourism is intertwined with the future of the island. However, it became apparent that they were in favor of a tourist model based on ecotourism, rather than that of mass tourism[14]. They pointed out that an alternative model should be supported by local authorities, based on proper planning, allowed activities and facilities in place, and respect for the environment. One participant also mentioned the need to tackle power imbalances, regarding the distribution of revenues from tourism.

Other points stressed by participants included the need for behavioral change towards environmental protection, to raise awareness about our actions’ impact first across the local society and then across the island’s visitors, to show consideration about future generations, and overall, a shift in social values.

“less attention should be paid to the ephemeral … a shared view that the sea is much more than a tourism product is needed … wealth is what we see, what we feel, what we experience around us and not what is in our pocket” (Anthony, male, age: 40s).

Discussion

The photovoice method provided insights into different dimensions of participants' relationality to the marine environment, mostly related to wellbeing and sense of place (as in Acott et al., 2021). Participants expressed eudaimonic and relational values (Chan et al., 2018), for example, by demonstrating the environment’s positive contribution to their quality of life (e.g., through aesthetics, health, and connections to others, with nature). Furthermore, relational and moral values (Chan et al., 2018) were also revealed, for instance, by emphasizing the need for people to perceive the sea differently (and not only through instrumental lenses related to tourism economic benefits) and to raise awareness about human impact within the local community and among visitors.

The results incite consideration of the potential of relational values, along with instrumental/economic values, to motivate citizens to care about marine sustainability and engage in marine planning and management. In such a context, instilling and fostering such values could be policy tailored. Furthermore, revealing a breadth of relational values fosters ocean literacy, possibly in a more comprehensible way, and contributes to more informative marine management.

“Practice-based place attachments” (Poe et al., 2016: 15) and cultural connections with the ocean/sea and the coast (Pafi et al., 2023; Strand et al., 2022), are linked to caring, ecological/ocean stewardship and willingness to react to unfavorable changes (Pafi et al., 2023; Poe et al., 2016; Strand et al., 2022). Practicing activities, positive emotional connection and sensory experiences of the sea, could be regarded as part of the key dimensions to people’s sense of place (Poe et al., 2016), aligned to the “experiential origins of marine identity” (Buchan et al., 2024a; 16), and potential driving factors of mobilizing citizens to protect the marine environment and engage in its sustainable management (Buchan et al., 2024b; Poe et al., 2016; Whyte, 2019). Furthermore, marine place attachment and dependency, but also values can mobilize participation in marine citizenship (Buchan et al., 2024b).

A shift in culture, including values, frames, and worldviews (Brodie Rudolph et al., 2020), reinforcement of relational values (e.g., of identity[15], social relations, sense of place[16]) (Riechers et al., 2022), and a consideration of positive relational-moral values, could potentially advance transformative change towards sustainability (Chan et al., 2018). Furthermore, emotions, although underrepresented in research studies on ocean perceptions, are among the factors that could be further explored and targeted as drivers of behavior change (Jefferson et al., 2021; Toomey, 2023).

Considering these, it becomes evident the importance of facilitating, preserving, and nurturing a pristine, ‘non-aseptic’ connectedness to the marine ecosystem, while enabling engagement to its management. This is substantiated by acknowledging the importance of relational values for human wellbeing, but also for the potential of achieving sustainability goals, both environmental and social. Regarding the latter, in marine policy frameworks and practices, lacking consideration of social and cultural aspects could raise equity and social justice issues (Bennett et al., 2022; Saunders et al., 2020).

Hence, there is a necessity to incorporate relational values within a participatory framework to inform planning and management[17] acknowledge existing stewardship, but also foster its growth so as to mobilize action and also enable social acceptance ( Kelly et al., 2019; Poe et al., 2016) Overall, transdisciplinary and participatory approaches could enrich our understanding on relational values and on how they can contribute towards marine governance (Riechers et al., 2022).

Participatory photovoice proved to be effective in making visible cultural and relational dimensions of marine ecosystems, to be further explored to inform marine management measures, along with material and tangible benefits (Dias and Armitage, 2021). Moreover, participants expressed positive feedback about the experience, finding it engaging and motivating stewardship. For some, it felt akin to “travelling” through photographs and stories. Finally, everyone concurred with Dimitra’s perspective that it was an opportunity for “sharing thoughts” and instilling a “sense of unity”.

Conclusion

The engagement of this small number of participants in our exploratory study revealed the depth and the polyprismatic dimensions that characterize their connection to the marine environment[18], ranging from instrumental values to a wealth of values beyond instrumental reasoning. These included for example, aesthetic, spiritual, identity connections, health and mental benefits, a place for bonding with others, oneself, nature, for gaining perspective of one’s existence etc. Furthermore, emotional attachment to the marine environment was particularly strong. Participants also expressed the wish for future generations to be able to enjoy the multiple benefits that it can offer.

Finally, although identifying different connections to the marine environment is important, it remains equally important to explore the pathways towards preserving and nurturing these connections, to potentially affect behaviors and motivate participation in marine management.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to all the participants who took part in the study and to the individuals and organisations that helped in the recruiting process. We would like to extend our gratitude to the Municipality of Andros for hosting the workshop, the Agadaki Estate for accommodating the photo exhibition and Panagiotis Loukadis, the estate’s garden keeper. We are also deeply thankful to Aris Tsantiropoulos, Associate Professor in Social Anthropology at the University of Crete, for his guidance and support.

Funding

This research was funded by the LIFE Andros Park project (LIFE16 NAT/GR/000606), implemented with the financial support of the European Union LIFE Instrument and the Green Fund.

Endnotes

References

- Acott, T.G., Willis, C., Ranger, S., Cumming, G., Richardson, P., O’Neill, R., Ford, A., 2022. Coastal transformations and connections: Revealing values through the community voice method. People and Nature 00: 1–12.

- Acott, T.G., Urquhart, J., 2015. People, Place and Fish: Exploring the Cultural Ecosystem Services of Inshore Fishing through Photography. In Warren S. and P. Jones, editors. Creative Economies, Creative Communities: Rethinking Place, Policy and Practice. Ashgate Publishing, Farnham, UK.

- Bennett, N.J., 2022. Mainstreaming Equity and Justice in the Ocean. Frontiers in Marine Science Section Marine Affairs and Policy 9 :873572.

- Bennett, N., Dearden, P., 2013. A Picture of Change: Using Photovoice to Explore Social and Environmental Change in Coastal Communities on the Andaman Coast of Thailand. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability 18(9): 983–1001.

- Böhnke-Henrichs, A., Baulcomb, C., Koss, R., Hussain, S.S., 2013. Typology and indicators of ecosystem services for marine spatial planning and management. Journal of Environmental Management 130: 135–145.

- Brodie Rudolph, T., Ruckelshaus, M., Swilling, M., Allison, E.H., Österblom, H., Gelcich, S., Mbatha, P., 2020. A Transition to Sustainable Ocean Governance. Nature Communications 11 (3600): 1–13.

- Bryce, R., Irvine, K.N., Church, A., Fish, R., Ranger, S., Kenter, J.O., 2016. Subjective well-being indicators for large-scale assessment of cultural ecosystem services. Ecosystem Services 21 Part B: 258–269.

- Buchan, P.M., Glithero, D., McKinley, E., Strand, M., Champion, G., Kochalski, S., Velentza, K., Praptiwi, R.A., Jung, J., Márquez, M.C., Marra, M.V., Abels, L.M., Neilson, A.L., Spavieri, J., Whittey, K.E., Samuel, M.M., Hale, R., Čermák, A., Whyte, D., West, L., Stithou, M., Hegland, T.J., Morris-Webb, E.S., Flander-Putrle, V., Schiefer, P., Sutton, S., Onwubiko, C., Adeoye, O., Akpan, A., Payne, D.L., 2024a. A transdisciplinary co-conceptualisation of marine identity. People and Nature.

- Buchan, P.M., Evans, L.S., Barr, S., Pieraccini, M., 2024b. Thalassophilia and marine identity: Drivers of ‘thick’ marine citizenship. Journal of Environmental Management 352: 120111. 1053

- Chan, K.M.A., Gould, R.K., Pascual, U., 2018. Editorial overview: Relational values: What are they, and what's the fuss about? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 35: A1–A7.

- Chan, K.M.A., Satterfield, T., Goldstein, J., 2012. Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecological Economics 74: 8–18.

- Coates, P., Brady, E., Church, A., Cowell, B., Daniels, S., DeSilvey, C., Fish, R., Holyoak, V., Horell, D., Mackey, S., Pite, R., Stibbe, A., Waters, R., 2014. Arts and Humanities Working Group (AHWG): Final Report. UK National Ecosystem Assessment Follow-on, UNEP-WCMC, LWEC, UK.

- Dias, A.C.E., Armitage, D., 2021. Ecosystems, Communities and Canoes: Using Photovoice to Understand Relationships Among Coastal Environments and Social Wellbeing. In Gustavsson, M., C. S. White, J. Phillipson, and K. Ounanian, editors. Researching People and the Sea. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, London, UK.

- Duggan, J., Cvitanovic, C., van Putten, I., 2023. Measuring sense of place in social-ecological systems: a review of literature and future research needs. Ecosystems and People 19(1): 2162968.

- Edwards, D.M., Collins, T.M., Goto, R., 2016. An arts-led dialogue to elicit shared, plural and cultural values of ecosystems. Ecosystem Services 21: 319–328.

- EL.STAT., 2011. Demographic and economic characteristics. Population, Employment and Cost of Living Statistics Division. Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- Game, A., Metcalfe, A., 2011. “My corner of the world”: Bachelard and Bondi Beach. Emotion, Space and Society 4 (1): 42–50.

- Gee, K., Kannen, A., Adlam, R., Brooks, C., Chapman, M., Cormier, R., Fischer, C., Fletcher, S., Gubbins, M., Shucksmith, R., Shellock. R., 2017. Identifying culturally significant areas for marine spatial planning. Ocean and Coastal Management 136: 139–147.

- Harper, D., 2002. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies 17: 13–26.

- Jefferson, R.L., McKinley, E., Griffin, H., Nimmo, A., Fletcher, S., 2021. Public perceptions of the ocean: lessons for marine conservation from a global research review. Frontiers in Marine Science 8: 711245.

- Judd, A., Lonsdale, J., 2021. Applying systems thinking: The Ecosystem Approach and Natural Capital Approach – Convergent or divergent concepts in marine management? Marine Policy 129: 104517.

- Kalaitsidaki, M., Mantadaki, K., Tsantiropoulos, A., 2022. Picturing the urban environment: using photovoice to bring university students’ views and voices into urban environmental education. In Korfiatis, K., and M. Grace, editors. Current research in biology education. Contributions from biology education research. Springer, Cham, London, UK.

- Kaltenborn, B.P., Linnell, J.D.C., Baggethun, E.G., Lindhjem, H., Thomassen, J., Chan, K.M., 2017. Ecosystem services and cultural values as building blocks for ‘the good life’. A case study in the community of Røst, Lofoten Islands, Norway. Ecological Economics 140: 166–176.

- Kampanis, S.M., Basantis, D., 2015. Η Άνδρος μέσα στο χρόνο (Andros through Time. In Greek). In Mamais, Y., editor. Gutenberg, Athens, Greece.

- Kelly, M.R., Kasinak, J.M., McKinley, E., McLaughlin, C., Vaudrey, J.M., Mattei, J.H., 2023. Conceptualizing the construct of ocean identity. npj Ocean Sustainability 2(17).

- Kelly, R., Fleming, A., Pecl, G.T., Richter, A., Bonn, A., 2019. Social license through citizen science: a tool for marine conservation. Ecology and Society 24(1):16.

- Kenter, J.O., Reed, M.S., Fazey, I., 2016a. The Deliberative Value Formation model. Ecosystem Services 21 Part B: 194–207.

- Kenter, J.O., Jobstvogt, N., Watson, V., Irvine, K.N., Christie, M., Bryce, R., 2016b. The impact of information, value-deliberation and group-based decision making on values for ecosystem services: Integrating deliberative monetary valuation and storytelling. Ecosystem Services 21: 270–290.

- Khakzad, S., Griffith, D., 2016. The role of fishing material culture in communities’ sense of place as an added-value in management of coastal areas. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 5:95–117.

- Leavy, P., 2020. Method meets art: Arts‐based research practice (3rd ed.). Guilford Publications, New York, USA.

- Matias, A., Carrasco, A.R., Pinto, B., Reis, J., 2023. The role of art in coastal and marine sustainability. Cambridge Prisms: Coastal Futures 1:e25.

- Natural England., 2017. Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment: The national survey on people and the natural environment. Headline Report from the 2015–16 survey. Report Version 2. Natural England Joint Report JP022. Natural England and other parties 2017, UK.

- NCC., undated. Διαχειριστικό Σχέδιο για τη ΖΕΠ Άνδρου. (Management Plan for the Special Protection Zone of Andros. In Greek). LIFE10 NAT/GR/000637 ‘ANDROSSPA’ project.

- Oteros-Rozas, E., Martín-López, B., Fagerholm, N., Bieling, C., Plieninger, T., 2018. Using social media photos to explore the relation between cultural ecosystem services and landscape features across five European sites. Ecological Indicators 94 No. Part 2:74–86.

- Ounanian, K., 2019. Not a ‘museum town’: Discussions of authenticity in coastal Denmark. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 17(3): 285–305.

- Pafi, M., Flannery, W., Murtagh, B., 2023. Picturing the coast: unravelling community perceptions of seascapes, Blue Growth and coastal change. Maritime Studies 22: 28.

- Poe, M.R., Donatuto, J., Satterfield, T., 2016. “Sense of Place”: human wellbeing considerations for ecological restoration in Puget Sound. Coastal Management 44 (5): 409–426.

- Riechers, M., Betz, L., Gould, R.K., Loch, T.K., Lam, D.P.M., Lazzari, N., Martín-López, B., Sala, J.E., 2022. Reviewing relational values for future research: insights from the coast. Ecology and Society 27(4):44.

- Saratsi, E., Acott, T., Allinson, E., Edwards, D., Fremantle, C., Fish, R., 2019. Valuing Arts and Arts Research. Valuing Nature Paper VNP22.

- Saunders, F., Gilek, M., Ikanuniece, A., Tafon, R.V., Gee, K., Zaucha, J., 2020. Theorizing Social Sustainability and Justice in Marine Spatial Planning: Democracy, Diversity, and Equity. Sustainability 12 (2560): 1–18.

- Severin, M.I., Raes, F., Notebaert, E., Lambrecht, L., Everaert, G., Buysse, A., 2022. Qualitative Study on Emotions Experienced at the Coast and Their Influence on Well-Being. Frontiers in Psychology 13:902122.

- Simmance, F.A., Simmance, A.B., Kolding, J., Schreckenberg, K., Tompkins, E., Poppy, G., Nagoli, J., 2022. A photovoice assessment for illuminating the role of inland fisheries to livelihoods and the local challenges experienced through the lens of fishers in a climate-driven lake of Malawi. Ambio 51: 700–715.

- Stithou, M., Tsantiropoulos, A., 2022. Fishing cultural heritage, local identity, and implications for maritime spatial planning. Proceedings of the 8th ENVECON Conference ‘Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment’, 2–3 December 2022. Hybrid, Greece. Available at: http://envecon.econ.uth.gr/main/eng/images/8th_conference/8th_ENVECON_proceedings.pdf (Accessed 17/10/2024).

- Stithou, M., Kourantidou, M., Vassilopoulou, V., 2022. Sociocultural ecosystem services of small-scale fisheries: challenges, insights and perspectives for marine resource management and planning. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management 25(3): 22–33.

- Strand M., Rivers, N., Snow, B., 2022. Reimagining Ocean Stewardship: Arts-Based Methods to ‘Hear’ and ‘See’ Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Ocean Management. Frontiers in Marine Science 9:886632.

- Terkenli, T.S., Georgoula, V., 2022. Local perspectives on cultural tourism and cultural sustainability: The case of the Cyclades, Greece.” In C. Ribeiro de Almedia, J. C. Martins, A. R. Concales, S. Quinteiro, and M. L. Gasparini, editors. Handbook of Research on Cultural Tourism and Sustainability. IGI Global: Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA.

- Thomas, M., Roberts, E., Pidgeon, N., Henwood, K., 2020. Using photographs in coastal research and engagement: reflections on two case studies. In M. Gustavsson, C. White, J. Philipsson, and K. Ounanian, editors. Researching people and the sea. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, London, UK.

- Toomey, A.H., 2023. Why facts don't change minds: Insights from cognitive science for the improved communication of conservation research. Biological Conservation 278: 109886.

- Wang C., Burris, M.A., 1997. Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Education and Behavior 24(3):369–387.

- Whyte, D., 2019. Belonging in the Ocean: Surfing, ocean power, and saltwater citizenship in Ireland. Anthropological Notebooks 25: 13–33.