The Death of the Youngest Lamafa: Love and the Struggle for Survival of Whale Hunters in Lamalera

Abstract

This research aims to understand the sea as a cultural space within the context of the Lamalera fishing community on Lembata Island, Indonesia. The Lamalera community is a fishing community with the privilege of catching whales, dolphins, and manta rays – species that are protected. The human relationship with the marine environment is a complex model, encompassing various aspects such as culture, economy, social, political, and spiritual dimensions. This study reveals cultural practices that have developed around the sea, including myths, customs, fishing traditions, maritime trade, and the utilization of marine resources. Furthermore, this research also identifies the role of the sea in shaping the cultural identity of the Lamalera community, including livelihoods, beliefs, and unique cultural practices. Through an interdisciplinary approach involving history, anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies, this research complements previous studies on the sea as a cultural space. The results of this research show that the Lamalera community has a close and unique relationship with the sea through whale hunting practices and other fishing activities. Their highly intensive interaction with the sea as their sole source of livelihood forms the identity of the Lamalera community as a traditional whale hunting fishing community (aboriginal subsistence whaling).

Keywords

cultural space, fishing community, whale hunters, local wisdom, aboriginal subsistence whaling

1. Introduction

On that day, May 11, 2018, the sea was very calm, the sky clear, and the air crisp. Benyamin Kleka Blikololong (29 years old), a harpooner of whales known as Lamafa, along with nine other Lamalera fishermen, set out to sea as usual. There was no inkling that it would be his last day hunting whales. As usual, they began the day with a prayer together, bid farewell to their families, and walked leisurely towards the beach, to the "naje" – the traditional boat house. The traditional boat "pledang" named Basaudara then glided majestically from the naje, the traditional boat houses lining the shore of Lamalera. Several hours later, in the middle of the Sawu Sea, they spotted a large manta ray swimming. Benyamin, the whale harpooner, prepared his harpoon and stood bravely at the bow of the boat. He gazed at the manta ray dancing. With the instinct of a Lamafa, he stabbed the manta ray while releasing the harpoon and its rope. His body seemed to soar into the sky, then plunged into the sea. It turned out to be Benyamin's final leap. His body never resurfaced until now. After weeks of search and rescue efforts, he was declared missing. Benyamin left behind a wife and two young children, aged 5 and 7.

Ignasius Serang Blikololong (75 years old), the father, stated that Benyamin, his youngest son, was the youngest Lamafa to die at sea in the struggle to provide for his family. Ignasius himself has witnessed more than 30 fishermen who have died at sea. In his memory, the number of people who have died at sea throughout the history of the Lamalera fishing village has reached hundreds. Some of the bodies of the deceased fishermen were found, while others were not.

This narrative illustrates the heavy struggle of traditional Lamalera fishermen in navigating the dangers of the sea and the economic competition on land. The Lamalera settlement is located on rocky cliffs, making it almost impossible for its residents to engage in agriculture (Taum, 2023a). Nature has shaped Lamalera into a community of resilient fishermen: men hunt and catch whales (leva alep), while women sell the catch from village to village (leva peneta) (Taum, 2023b).

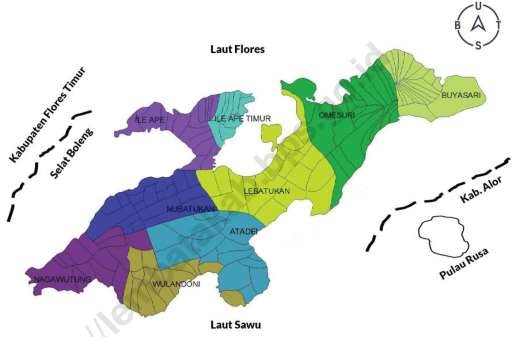

The Lamalera community, comprising approximately 4,000 individuals, resides in the southern part of Lembata Island, dispersed across the villages of Lamalera A, Lamalera B, and several other surrounding villages in the Wulandoni District. According to their origin stories, their ancestors hailed from various regions, including Luwuk in Central Sulawesi, Lepan Batang, the Soge tribe, and Sina Jawa.

Geographically, Lamalera is flanked by two capes, Cape Vovolatu and Cape Nubawutun, at coordinates 51 L 0545725, 9051853 UTM, with an elevation of 26 meters above sea level. Lamalera is a barren area, consisting of large and small rocks. The soil composition, climate, and water sources significantly impact the natural and social environment of the Lamalera community. As described by Fox (1990: 3–4), NTT is one of the islands situated on the Lesser Sunda mountain range, characterized by mountains and highlands. The coastline in Lamalera is steep and rocky, with only a few sandy beaches where the community anchors their boats. The villages are situated on rocky cliffs, making agriculture nearly impossible. The harsh environment has shaped the Lamalera people into resilient fishermen: men hunt and catch whales, while women sell the catch from village to village (fulepenetan). It is almost unimaginable to think of Lamalera without whales. Additionally, Lamalera is known as a center for the spread of Catholicism on Lembata Island, and therefore, various whaling traditions are performed with Catholic rituals and ceremonies.

Given their environmental conditions, the Lamalera people have no other choice but to become tough, brave, and persistent fishermen. Fishing is their survival strategy. Lamalera has a tradition of catching and hunting large and small fish for centuries. They catch dolphins, manta rays, and whales, which are species protected by international law, particularly through the International Whaling Commission (IWC) since 1986. The Indonesian government has included whales and dolphins as protected animals and prohibited their hunting (Government Regulation PP RI Number 7 of 1999 on the Preservation of Plant and Animal Species). In their fishing practices, they perform various rituals and traditional ceremonies to seek assistance from supernatural and preternatural forces.

Lamalera is a fishing village on Lembata Island, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia, which has had a tradition of hunting whales for centuries. They also hunt dolphins, manta rays, and whales, which are species protected internationally, particularly through the International Whaling Commission (IWC) since 1986. The Indonesian government has classified whales and dolphins as protected species and banned their hunting (Government Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia No. 7 of 1999 concerning the Conservation of Plant and Animal Species).

Whale hunting is the practice of hunting whales to obtain products such as meat, oil, and blubber that can be used by humans. This activity is believed to have been practiced since around 3000 BC. Coastal communities have a long history of whale hunting as a source of livelihood and collecting the hunted whale meat. The whaling industry emerged with organized fleets in the 17th century; became a competitive fishing industry in the 18th and 19th centuries; and introduced factory ships and the concept of whaling in the first half of the 20th century. By the late 1930s, more than 50,000 whales were killed annually. In 1986, the International Whaling Commission banned commercial whaling due to the extreme decline in whale populations. Today, whale hunting in Lamalera remains a controversial issue. Some groups advocate for a ban on whale hunting under the guise of conservation. Other groups oppose the ban on whale hunting with their arguments, while environmental groups reject the lifting of the ban.

This research aims to uncover the cultural practices that have developed around the sea in Lamalera, such as myths and legends, customs, fishing traditions, maritime trade, and the use of marine resources. These maritime cultural practices contribute to shaping the cultural identity of a society: livelihoods, beliefs, and unique cultural practices characteristic of Lamalera.

2. Literature Review

The academic study that explores the relationship between humans and the sea, viewing the sea as a cultural space, is a broad field of study that includes the disciplines of history, anthropology, sociology, and culture in general. Some prominent studies include those conducted by Bentley & Ridenthal (2007), Crang (2011), Paine (2014), Strang (2014), Radovanovic (2015), Corsi (2017), Parlangeli (2019), and Yordan (2020).

Jerry H. Bentley and Renate Bridenthal (2007) in their book "Seascapes: Maritime Histories, Littoral Cultures, and Transoceanic Exchanges" combine maritime history with the cultural geography of the sea to understand the impact of transoceanic exchanges on human cultural identity. The availability and types of marine resources accessible to communities, such as fish, mollusks, and coral reefs, will influence their livelihood patterns and consumption patterns. Furthermore, coastal and island communities have cultures closely related to the sea, including fishing traditions, traditional boat-making techniques, myths and legends of the sea, and rituals related to marine life.

Mike Crang and Mark Jayne (2011) reveal in their book "The Cultural Geography of the Sea" that government policies regarding the exploitation of marine resources can also play a crucial role in shaping maritime culture. Fisheries regulation, environmental protection, and traditional fishing rights influence how communities interact with the sea.

In his book "The Sea and Civilization: A Maritime History of the World," Lincoln Paine unveils the history of the sea and its influence on human culture, including art, music, and local traditions related to the sea. Veronica Strang (2014) in her book "The Ocean as a Cultural Landscape" describes the role of the sea in human culture and how the sea has shaped cultural identity and human history worldwide. In an article titled "The Sea as Cultural Space: The Example of the Mediterranean," Bojana Radovanovic (2015) discusses the role of the sea in Mediterranean culture, including art, music, myths, and oral traditions related to the sea. Pietro Corsi (2017) in his book "The Sea in History: The Modern World" describes the history of the function and role of the sea in human life, including in art, music, myths, and local traditions.

Furthermore, in the book "Oceanic Culture History: The Adventure of Human Relationship with the Sea" by Oronzo Parlangeli (2019), the history of human relationships with the sea is discussed, including the role of the sea in art, music, and local traditions worldwide. Yordan Lyutskanov (2020) in an article titled "Black Sea as Literary and Cultural Space: State of the Art and Prospects" discusses the concept of "literary space" developed from various perspectives by scholars in the context of cultural geography and interdisciplinary literary studies.

The sea as a cultural space refers to how people use the sea as a source of inspiration and cultural expression. This involves various practices, such as art, music, myths, legends, religion, and local traditions, related to the sea and everything associated with it, such as marine life, fishing, navigation, and maritime history. The sea is also often a theme in visual arts, such as painting and photography, and in popular culture, such as film and music. Additionally, people often celebrate festivals related to the sea, such as fishermen's festivals or sea-related celebrations in various parts of the world. Overall, the sea as a cultural space is an important aspect of human cultural heritage and continues to be a source of inspiration for communities living in coastal and non-coastal areas worldwide. This study is a case study of the Lamalera community on Lembata Island. This community demonstrates a close relationship with the sea.

The geographic conditions, climate, and access to marine resources play an important role in shaping the cultural identity, livelihoods, and traditions of communities living around the sea (Crang and Mark Jayne, 2011). Lamalera, its fishermen, and the natural environment have a highly complex relationship pattern that forms a distinctive cultural space. Studying the sea as a cultural space helps understand how humans interact with the sea in various aspects of their lives (Paine, 2014). This interaction includes cultural, economic, social, political, and spiritual relationships between humans and the sea.

3. Research Methodology

This research is conducted using a qualitative approach with a focus on Eastern Indonesia, specifically Lamalera, Lembata Regency, East Nusa Tenggara Province. The research is essentially a field study involving the collection of data through direct observation, interviews, and participation in the daily lives of the community related to the sea. Field researchers are useful for observing fishing activities, following fishermen's journeys, and interacting with the fishing community to understand cultural practices related to the sea.

The research design uses document study, interviews, and observation of qualitative data. Descriptively, data is obtained through interviews and observations, related to sources of information about whale hunting traditions practiced by the Lamalera and Lamakera communities in East Nusa Tenggara. Document studies are used as secondary data to complement the primary data obtained in the field.

The object of this research is local wisdom/whale hunting traditions in the Lamalera community and related stakeholders, including the community involved in whale hunting, as well as local and central governments responsible for regulating whale hunting.

Referring to the two forms of data in this research, namely primary and secondary data, the data collection techniques can be grouped into three methods: (a) document study, (b) interviews, and (c) observation. Before collecting data, the research team will first apply for ethical clearance as an integral part of the social humanities research process required by the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN).

4. Findings and Discussion

The understanding of the sea as a cultural space in this research will cover three main aspects: (1) the cultural geography of Lamalera, (2) whale hunting and its traditional rituals, and (3) the sea of Lamalera and traditional knowledge.

4.1 Cultural Geography of Lamalera

According to Cultural Geographers James S. Duncan and David Ley, cultural geography is "the scientific study of regions and places in relation to the distribution and characteristics of culture, as well as the processes that shape them" (Duncan, 1993). Cultural geography is a branch of geography that studies the interaction between culture and the physical environment and its impact on society and the landscape. This concept encompasses various cultural aspects, such as language, religion, customs, arts, and architecture, as well as how these elements shape the identity and characteristics of a region.

The village is located between rocky hills and cliffs. This area is administratively part of Pulau Lembata Regency. Geographically, this area is facing the Sawu Sea. The village of Lamalera is famous for its tradition of whale hunting, known in the Lamalera language as "koteklema."

The sea is a cultural space for the Lamalera community, one of the ethnic groups in the Wulandoni District, Lembata Regency, East Nusa Tenggara Province (Tube, 2017: 1). Their way of life, which depends on the sea (ola nua), reinforces their identity as a maritime community. The Lamalera community rejects the use of the term "whale hunting," preferring to call it "hode knato," which means "taking gifts" or blessings from the sea through the tradition of tuba feda, stabbing whales (koteklema). This tradition is an inherited legacy that has been going on for more than 500 years (Barnes, 1996), since their ancestors inhabited the area. In their expression, "Ammak genna olae, ola kae kode kai," which means "Our ancestors passed down this work, and we will also pass it down."

The Lamalera fishing village is divided into two villages, Lamalera A and Lamalera B. This division of the two fishing villages was carried out by the government in response to the increasing number of people in Lamalera. However, an interesting phenomenon has occurred as a result of this division. The interesting aspect is the movement of people between Lamalera A, located further up the coast, and Lamalera B, located on the beach.

A description of the two villages, Lamalera A and Lamalera B, is as follows. People from Lamalera B, the beach village, who want to go to Lamalera A must pass through a place with a steep cliff called Gripe. There is only one path consisting of stones where people can place their feet to climb or descend. This must be done carefully because there is a cliff next to it. For the local residents who are accustomed to it, there is no difficulty, but it is different for foreigners (Bataona, 2015: 114). It was only in 1998 that the stairs were demolished and a new "Gripe" was built, now in the form of a road that can be traversed by two or four-wheeled vehicles. In the past, Lamalera had a kakang (head of hamente/gemeentehoofd — Dutch language). Since 1950, Lamalera, which has developed more extensively, was divided into two villages, namely Lamalera A (upper), called Tetilefo in the Lamalera language, and Lamalera B (lower), called Lalifatan, one of which is located higher while the other is lower at the edge of the sea. The two villages are separated by a hill called Fung, an area covered with large stones, but there are also a number of houses there.

Notes from Portuguese explorers in the 16th century mention the existence of a community in Lembata that hunted whales using traditional methods (Mustika, 2006). For coastal communities like the Lamalera people, fishing and gathering marine resources are indeed their main daily activities for food and livelihood. The ancestral tradition of tuba feda or traditional fishing reflects how the ancestral heritage is still faithfully practiced and upheld by the fishermen of Lamalera. The majority of the Lamalera community adhere to the Catholic faith.

The sea plays a crucial role in the lives of the Lamalera fishermen on Lembata Island. For this fishing community, the sea is a source of livelihood, transportation, and trade. Therefore, their culture has developed with a very rich knowledge and experience of the sea. They have also developed unique oral traditions, rituals, arts, and music inspired by the sea. The issue to be discussed in this research is related to the sea as a cultural space of the Lamalera community.

Entering the village of Lamalera, two cultural icons are prominently seen, namely the boat house (naje) and the traditional boat (pledang). Naje is a special place used for the protection and storage of Pledang. In Lamalera, naje is located on the beach. Naje is a traditional structure built by the Lamalera community. The function of Naje is not only as a storage place for boats but also as a place to protect the boats from damage and bad weather conditions.

The boats that have been damaged and decayed are stored in the Naje. These boats cannot be discarded, let alone sold as old or scrap items. The boats are highly revered. The ancestral message passed down through generations is firmly upheld by the local community. Boats, especially the peledang (tena lamafaij) used specifically for whale hunting (koteklema), cannot be sold for any reason. Peledang in Lamalera also cannot be brought in from outside the area or taken out of the area.

In Lamalera, the Naje is located on the beach. Around 30 boat houses with woven lontar leaf roofs supported by neat rows of round wooden poles. Without walls, the boat house or peledang, also known as naje, is a place for various activities. Here, residents weave various crafts from lontar leaves, make ropes for fishing gear, and make sampans used for catching small fish. The Naje is also a place to rest during the hot midday sun. The breeze from the Sawu Sea often makes it difficult to keep one's eyes open. Whale hunting or lefa does not take place throughout the year. There is a resting season or lefa bogel. During this time, fishermen search for small fish.

The Lamalera community has a type of traditional boat called peledang or tena lamafa. Peledang is the traditional boat of the Lamalera community. Peledang is a large boat equipped with a sail made of woven gebang leaves. It is about 10 meters long, approximately 2 meters wide, and 1–1.5 meters high. Peledang is equipped with cadik – wooden outriggers on the right and left sides. These outriggers are intended to help protect the crew when the stabbed whale goes into a frenzy and tries to attack.

The Peledang is usually made in October, at the end of the whale hunting season (May-October). The boat-making period is completed by March, and it should be operational by April, so that by May, at the beginning of leva nuang, the sea season, the new boat can already be launched into the sea. The making of peledang begins with the ritual called pau laba ketilo, an event at the traditional house, atamola. All clans are invited to perform worship, pray, and conduct rituals to honor the ancestors, and offer sacrifices to the special equipment that will be used so that the process of making peledang can proceed smoothly.

Inside a Peledang (traditional Lamalera boat) used for hunting whales, the Lamafa occupies the front position as the captain and holder of the traditional harpoon called tempuling used for spearing whales. Inside the boat, he stands in a place called hamma lollo and sits in the kerakki (Alaini, 2018). A Lamafa certainly has great courage and bravery because he risks his life every time he spears a whale. In reality, quite a few Lamafa have lost their lives in the sea during this whale hunting mission. The Lamafa is assisted by his assistant called Breung Alep, rowers called Matros (usually 10 rows) each occupied by a person called Meng. At the back (stern), sits the helmsman called Lama Uri (Taum, 2023b: 202).

The peledang is specially made from the angsana wood (pterocarpus indica), which is still abundantly available in Lembata. According to the figure from the Lelaona Tribe, Martinus Huku, who is also an atamola, to make one boat, it takes about 20 angsana trees, which cost around Rp 300,000-Rp 400,000 per tree. Currently, the estimated price of one Lamalera boat is Rp 50 million-Rp 100 million.

The size of Lamalera's peledang boards is not made arbitrarily. Similarly, the joints between the boards, the sequence of arranging one board with another, must adhere to the customary provisions inherited from ancestors. If violated and technical errors occur in the installation, it is believed to result in a lack of harmony between the bow and stern of the boat. If that happens, it will affect the agility and speed of the boat. Errors in construction can also result in cracks at each joint or gaps in the board joints, making it easy for seawater to enter the boat.

There should be no iron elements, such as nails or bolts, on the body of the peledang. If violated, it is believed that the whale will attack and strike the boat until it breaks into pieces. If a damaged boat is attacked by a whale, it is also believed that there was a mistake in the boat's construction. In one peledang, there are 4–6 rowers led by a Lamafa or spearman.

The peak of peledang making is concluded with the pau soru naka ritual, the return of tools to their place, and a ritual of gratitude because the tools, considered to have a soul, have worked well until the boat is completed.

GA Herridge, a researcher of traditional boats (Lashed-lug beat of the eastern archipelagoes, 1982), classifies Lamalera boats as one of the remnants of the pegged-tying method known in the early Bronze Age Indo-European culture. Lamalera, with all its richness in tradition, has its own charm. This tradition is one of the most unique in the world. Peledang has proven to be a traditional boat capable of exploring the open ocean.

4.2 Whale Fishing and Its Rituals

The tradition of whale fishing by the people of Lamalera Village, Wulandoni District, Lembata Regency, has been going on for a long time, since the ancestors of the Lamalera tribe inhabited the area. The practice of hunting whales began in the 17th or perhaps the 16th century. Portuguese records mention the presence of a community in Lembata engaged in traditional whale hunting.

Whale hunting is carried out by adult male residents of Lamalera who are considered to have the necessary skills (usually, each family delegates one member). Before hunting, they all pray to God for success in the whale hunt. Whale hunting is carried out during the fishing season known as Leva Nuang. The Leva Nuang season usually lasts from May to October. The Leva Nuang season is opened with various traditional and religious ceremonies. Three days before the fishermen officially go out to sea, the Tobo Neme Fatte ceremony is held, which is usually held every April 29th.

This ceremony is attended by the communities of both villages (Teti Levo and Lali Levo or Lamalera A and Lamalera B), along with the landlord (levo alep), customary leaders, community leaders, tribal heads, and boat owners to discuss Ola Nue (earning a living from the sea). It takes place in front of the Chapel of St. Peter and Paul. They offer each other betel nut and betel leaves. The meeting is led by an Ata Mole (wise person). They evaluate the leva activities over the past year, forgive each other for mistakes and inadvertences, and determine the two boats that will go out to sea after the opening Mass of the Leva season on the beach on May 1st (Batafor, 2017).

The fishermen wait for someone to shout "Baleo! Baleo!" This call indicates that a whale has surfaced, which usually occurs between the fishing months of May and October. The hunt can take hours. When the whale is spotted, the boatmen row towards the target whale. The Lamafa then immediately thrusts the harpoon into the heart of the whale, three to four times until the whale becomes exhausted and loses blood. The first thrust can be very dangerous for all crew members because the whale will lunge, writhe in pain, and destroy anything nearby.

The Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus) is the only whale species that the people of Lamalera are allowed to hunt. The Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus) often passes by them as the largest cetacean, but this species is never hunted. Besides aiming to conserve these large marine mammals, tradition states that the Lamalera and Lembata were once saved by a blue whale in the past. Another taboo for them is killing pregnant female sperm whales, whale calves, and mating whales. Sensitivity to these conditions can only be passed down by the sailors in Lamalera.

The tradition of the customary ceremony before Leva Nuang is quite solemn. Three days before the religious mass ceremony, a meeting involving customary leaders, community figures, landlords, boat owners, and the village government is held to discuss preparations and issues related to fishing in the upcoming season (ola nuang) and preparations for the official opening of the fishing season (leva nuang).

The Leva season is initiated with a series of traditional rituals that must be performed. The people of Lamalera believe that all efforts to seek sustenance, to find food, must be done with a pure heart. The Tobu Neme Fatte ceremony is held. Tobu Neme Fatte means sitting together on the beach. This ceremony is a rite to settle tribal and landlord issues before whaling. Its aim is to create a harmonious condition and build a peaceful atmosphere. If there are any wrong words, attitudes, or actions, including disagreements about anything, whether at sea or on land, they must be resolved. All issues must be settled according to tradition before the start of the soul mass and the Leva mass. The parties involved are the tribal landlords of the Wujon and Tufaona tribes, as well as the Lika Telo (three pillars) which include the Bataona, Blikololong, and Lewotukan tribes. During the Tobu Neme Fatte, the previous year's Leva activities are evaluated together, and several rules are agreed upon as guidelines for the upcoming Leva season. At this moment, all community members transparently forgive each other.

In this activity, the tribal landlord of the Wujon tribe, known as Suku Lango Wujon, has higher authority. They have a very important position and responsibility as intermediaries or connectors for the people's messages to be conveye d to their deceased ancestors who reside in a place called Batar on Mount Labalekan.

The Ie Gerek Ceremony at the Whale Stone

The series of traditional ceremonies that begin at Batar is called the Ie Gerek ceremony, which is a ceremony to call the spirit of the whale from a large rock shaped like a whale at a place called Batar. The purpose of this ceremony, which is to call the spirit of the whale, begins from Mount Labalekan because the people of Lamalera believe that whales actually come from the mountain. Whales are the embodiment of ancestors who offer themselves as food for their descendants.

Batar is located on a hill about 1.5 km from the Lamalera village. Batar is believed to be the residence of the ancestors of the Lango Wujon tribe, the landlords in Lamalera. From here, the traditional ritual of whale hunting begins. The place is offered offerings, including burning tobacco, pouring tuak (a traditional alcoholic drink), sprinkling ground corn, and breaking chicken eggs. Traditional verses are also sung from this place, accompanied by the sound of a gong.

A visit to Batar is usually carried out on April 29. Three envoys from the landlords of the Bataona, Blikololong, and Lewotukan tribes, along with other participants, climb Mount Labalekan carrying tuak, betel nut, tobacco, a chicken egg, and a rooster, wearing traditional compang-camping attire. They will meet the spirits of their ancestors Bele Raja Rimu and Bele Jawa Lepang Ina, believed to reside in Igo Lewu. This place is a steep cliff with a large hole. Inside the hole reside the two ancestral spirits, which have transformed into two large snakes (Boli, 2018). They knock on the stone near the hole where the snakes hide while placing betel nut, tobacco, and tuak near the hole. They then recite the following mantra three times. (All mantras in Lamalera language were recorded by Boli, 2018).

Bele Raja Rimu,Bele Jawa Lepang Ina

Kame geje maserum mi grap lame

Ke kide kanukaja

Ke lef,ju fata,de gej lau una koker

De leta duru kalolo di kame

Fe kam gej ma leta di Bele Raja Rimu

No bele Jawa Lepang Ina

Mio begem kpako lolo fai

Ger punga fai,uaj lolo fai,fe kam metej lodo

De ma parafa kide knuka je lef,ju fata”.Oh, Grandfather Raja Rimu and Grandmother Jawa Lepang Ina,

We come here to meet both of you to convey the sorrows and cries of the widows and orphans on the shore, that they are hungry and thirsty.

They have come to the big house to convey all of this. We come here to plead with grandfather and grandmother, may we be given vegetables in moderation such as ferns, rattan leaves to sustain their families, both in the upper village and the lower village.

Shortly after, one of the two snakes inside the hole will come out, lick all the offerings, then raise its head, open its mouth wide to be fed a chicken egg by the leader of the group. At the moment of feeding the chicken egg into the snake's mouth, the leader of the group will recite the following mantra.

“Bele mi juam emu um lawak miuo ke jad kam tuegem ar mi juam dorigen. Fe te tet furu kalolo ta parafa kide knukuja ked a ju lef erra bal brata buk lejo puk da maluf…

Taisa ta ju ta… kam moi mi dor.

"Grandfather and grandmother have received our offerings. And now we will return. However, we hope that grandfather and grandmother will soon follow us, so that together we can bring these modest vegetables to the beach to sustain those who lament day and night due to hunger and thirst. Please join us immediately."

The second ritual is carried out at a location called Rang Gawak. At this place, an offering is made of a rooster, which is hung at the end of two bamboo poles purposely pierced through the rooster's head. After piercing it with a sharp object, the following mantra is recited.

Manuk mo kri kam tojok, fe mo bek lau mai aka,

mo mataj re

Linerh noka lefa lau na, na kre re

Ikaja lau lefa da gejing, fed a tubak aka,fed a para kide knukaja ju lef."O chicken, now you are hung. Your head will be pierced, you will struggle and die. If your feet point towards the sea, it signifies that fish will be obtained.

People will savor it and bring it home to the village, to feed the widows and orphans."

The chicken, after being killed, was roasted on the spot. They then ate together while drinking tuak hastily. From Rang Gawak, the journey continued to the third location called Itok Kawe Lango. Here, the group pulled out alang-alang grass, which was then placed into a buffalo-snout-shaped stone hole.

Next, the group proceeded to the fourth location called Pau Gora. Similar activities were conducted here as in the previous location. The group then moved on to the fifth location called Enaj Snoa. Along the way to this place, the group had to sound a gong to summon the spirits to accompany their journey. The ceremony conducted at this location involved placing offerings such as betel nut, tuak, and rolled tobacco. The leader of the group climbed a large rock while reciting the following mantra.

Taisa, taisa ee…! Taisa to fata ju, tet furu

Kalolo fe ta parafa kide knukaja… Taisa, taisa ee…!Let's all depart…! Let's go to the beach, bringing vegetables For the widows and orphans. Let's all depart…!

After that, the group proceeded to the sixth location, namely Watu Koteklema (a rock shaped like a whale). The leader of the group jumped onto the large rock while waving a branch with alang-alang leaves attached, and recited the following mantra.

Ker ker kerrrrr… Me me me meeeee

Taisa taisa taisaeeee

Moraj lau mai gejing dara ika, gejing dap au para fa kide knukaja!

Ker ker ker kerrrr, me me meeee, ngoa ngoa ngoa ngoaaa…!

Taisa taisa to fata ju ta…!

Ker ker kerrrrr… Me me me meeeee

Ngoa ngoa ngoa ngoaaaaaaa!Ker ker kerrrrr… Me me me meeeee

Let's go, let's all go and take them all to the sea so they become fish.

Ker ker ker kerrrr, me me meeee, ngoa ngoa ngoa ngoaaa…!

On land, on the mountain, make corn, pumpkin, beans abundant for the food of widows and orphans.

Let's go down to the beach.

Ker ker kerrrrr… Me me me meeeee

Ngoa ngoa ngoa ngoaaaaaaa!

The group then proceeded to their sixth destination, Bani Lollo. They descended a footpath through a narrow alley leading to the location of Batan Bala Mai (Naming Bataona). The group was welcomed by elders of the tradition, offered betel leaves, rolled tobacco, and palm wine. Subsequently, the group would recite the following mantra.

“Ina, ama, kaka, waji, kide knuka…

Mi lau mai fe ma teben lau tobi bao nama fatta

Kame tue lau aka, neme tit pnuanes.Mothers, fathers, siblings, children, widows, and orphans, please proceed to the beach and await us at Tobi Bao Nama Fatta. Once we return from the sea, our discussion will continue there."

After delivering the message, the group hurried to the beach, immersing themselves in the sea to cleanse their bodies. Everyone waiting for them on the shore was divided into two groups. The western group was occupied by people from the Bui Pukka to Muko Tena boats, while the eastern part was occupied by people from the Sia Apu to Jawa Tena boats.

Tobo Neme Fate Ceremony

At that time, all the people of Lamalera gathered on the beach and sat in front of the Chapel of St. Peter, which is located on the beach. This place is called Ika Kota Uli because in ancient times it was used as a place to store the bones of whales. The Tobo Neme Fate ceremony was continued by a traditional leader who invited all the people of Lamalera to reflect, examine their inner selves sincerely and willingly, and to confess sins, mistakes, and shortcomings among all the people of Lamalera, as well as the landowners and shareholders (umma alap). If, sincerely and willingly, each of them has expressed all their complaints and shortcomings, then symbolically they will express regret and forgive each other in the form of chewing betel nut together as a sign of peace.

After confessing mistakes and asking for forgiveness and blessings from the Lango Fujjo tribe, landowners, and several traditional elders, they immediately rose to the edge of the sea and offered the following prayer.

O Ama Lera Wulan Dewa Tana Ekan

O Ina Ama, Koda Kefoko

Sukulu, bawaka ikaja da kre besol

Fe dada tubak

Je dai je lef fed a parafa kideknukaja

Ke da je lef

Da erra bal brata, mi da malufO God on high

O spirits of the Ancestors

Let the fish in the sea be lost

Send them here

So that we may catch them

For the widows and orphans

Who lament day and night

Because there is no food

The Tena Leva Ceremony

Upon reaching the shore, four individuals immerse themselves in the sea, as a ritual to call upon the fish. Meanwhile, two spear holders wait on the beach. The ceremony concludes when the four individuals emerge from the sea and gather in front of the Chapel of St. Peter and St. Paul on the beach.

The next day, the boats designated as tenna fulla will be the first to descend into the sea, followed by the entire fleet the day after. All fish caught during this official period are counted as the catch for one year of the sea season (massa leva). After the evaluation discussions are concluded, the activities continue with drinking tuak (local palm wine) and eating jagung titi (a local dish) together involving the entire Lamalera community. They designate one or two boats at the eastern end and one at the western end as the first boats to go out to sea.

The description above shows that the hunting and catching of whales and various protected marine species have passed through a series of traditional ceremonies. These traditions and customs are followed strictly and systematically, and have been passed down for centuries. The traditional hunting of whales is a part of the cultural identity of the Lamalera community.

4.3 The Sea of Lamalera and Traditional Knowledge Systems

Traditional knowledge systems are a collection of knowledge, beliefs, practices, and values passed down from generation to generation within a specific society (Berkes, 1999; Drew, 1998). The environment has shaped Lamalera into a resilient community of fishermen: men hunt and catch whales while women sell them from village to village, a practice known as fulapanetan. This paper will present several traditional knowledge systems of Lamalera, namely the navigation system and the traditional trading system, as well as souvenirs as part of cultural tourism development.

The navigation system is a series of methods, tools, and techniques used to determine the position and direct the movement of an object on the earth's surface, in the sea, in the air, or in outer space. The purpose of the navigation system is to assist an individual or an object in determining their current location, planning a route, and reaching their destination effectively and accurately. The navigation system encompasses various aspects, including distance measurement, direction measurement, and time calculation. The people of Lamalera are familiar with traditional navigation systems in their fishing activities. They have a habit of reading natural signs, which can be interpreted as determining direction, attitude, and even the fate of fishing at sea. These signs include bird sounds, wind direction, and ocean currents.

A bird called 'kollo leva' serves as the first sign for fishermen when they are at sea. The kollo leva bird usually sings at night, as if signaling to the fishermen who will be at sea the next day. These fishermen are very familiar with the sound of this bird. They understand and can interpret its 'message,' whether tomorrow's fishing will be successful or not. Often, fishermen decide not to go to sea if the sound of the kollo leva bird indicates that they will fail.

Wind direction is the second sign that holds significant meaning for Lamalera fishermen. Wind direction can also be read as a sign of luck or misfortune that fishermen will experience at sea. According to Lamalera fishermen's beliefs, if the wind blows strongly from the west, they will definitely decide not to go to sea. This wind is called farra blekku. In such conditions, fishermen believe that fish will also not surface.

Stellar science (astronomy) is also known in Lamalera fishermen's society. If they see the "cross star" (nua tapo), then the star is in the south. Meanwhile, the "seven stars" (wuno pito) are in the east. This knowledge guides them safely back to the village.

The third important indicator is ocean currents. Ocean currents are believed to directly affect fishermen's catches. Ocean currents are called Furs and Enna Ole. If the current at the bottom of the sea is very strong (this is called Furs), they believe that fish will appear on the surface, so their catch will be plentiful. Conversely, if the current above the sea surface is stronger (this is called Enna Ole), the fish will go to the bottom of the sea, so they will return empty-handed. In the traditional navigation system, Lamalera fishermen are familiar with another type of current called Kaju Lolong. This current indicates that there are many fish in that area. If this current appears, the traditional boats will be directed there immediately.

Mount Ile Labalekan serves as the fourth landmark that is also an important directional marker for traditional fishermen. The peak of Ile Labalekan, standing at 5,318 feet, often indicates the direction to the fishermen's village. Traditionally, the whale meat obtained is consumed by the village community and does not exceed the overall livelihood needs socially. Sometimes, the number of whales caught fluctuates according to the availability and needs of the community. If the fishermen encounter problems at sea, they can perform hadek blettu, which involves raising a bamboo pole with blettu on top. Blettu is a traditional hat made of palm leaves that fishermen usually take to sea to avoid the scorching sun. Blettu also serves as a signal that they need assistance because they are in danger. If fishermen from other boats see the hat on top of the bamboo pole, they will approach to provide assistance. Another expression commonly used is hadek klala (Alaini, 2018).

The whale meat obtained from this hunt will be distributed to the entire population according to the extent of the contribution of their family members in the whale hunting process. In addition to the meat, the community also utilizes whale oil as massage oil, medicinal ingredients, and fuel for lamps or torches.

The sea's bounty is also taken by women to the mountainous areas where they barter it for corn, rice, or sweet potatoes. In the past, women had to walk tens of kilometers. Now, bartering is easier with the availability of vehicles. At night, Lamalera Beach is the sound of the Sawu Sea waves that never cease. Lamalera's youth gather during bright moonlit nights on the black sand beach. Amidst the waves, the melodic chant of the lamafa's return can be heard. "Sora taran bala tala lefo rai tai/Tuba bera rai nai ribu lefo gole/Kide ina-fai tuba bera rai nai", which means "The buffalo with ivory horns/Let us journey to the village over there/The whole community longs for your presence/Come, let us go there quickly." This chant accompanies the haul of a 15-meter-long whale. It will feed not only the people of Lamalera but also the people of Lembata.

Barter in Lamalera is done through panetan. In the division of labor, panetan is the main work done by women. This activity takes place between the coastal community of Lamalera and the mountain communities around it. The interaction process between several villages, namely the coastal village and the mountain village whose lives are supported by two relatively different environments, has established a complementary shared economic system. The commodities exchanged are the sea products from the coast and the agricultural products from the mountain area. The barter system meets the basic needs of both communities. The mountain community's protein needs are met by dried fish brought by Lamalera women, while the coastal community's carbohydrate needs are met by harvests from the mountains. Panetan is carried out by bartering pieces of dried fish for corn, rice, tubers, beans, and vegetables. The panetan activity starts early in the morning, with women usually leaving around 3:00 or 4:00 a.m. to walk to nearby villages. The bartering activity is done from house to house. Usually, after they arrive at the neighboring village, they wait for daylight before going to houses to offer their fish.

Unlike panetan, which is done directly to neighboring villages by walking from house to house, regular barter exchanges are also facilitated. There are two barter markets held each week. The first barter market is held every Saturday in Wulandoni, and the second barter market is held every Wednesday in Posiwatu village. The Wulandoni barter market is larger and more active than the Posiwatu barter market. This is where all possible commodities for exchange meet. There are fish, salt, and lime owned by the fishermen, staple foods from the mountain gardens, vegetables, tuak (a traditional alcoholic beverage), betel nuts and leaves, bananas, and many others.

The history of the Wulandoni barter market initially facilitated the exchange of goods among the villagers, specifically the Lamalera fishermen community. However, it has evolved to become a means for almost all villages in the Wulandoni sub-district to conduct trade and transactions. Currently, the Wulandoni barter market is managed by the Wulandoni sub-district government. Based on data obtained by researchers in 2014, there was a disruption in the Wulandoni sub-district due to land disputes. As a result, the traditional market in Wulandoni was moved to Lamalera A village and remains there to this day. From the research analysis, it can be concluded that the Lamalera community has been using mathematical calculations in their barter life. From panetan and barter, it turns out that there are mathematical calculations used by the community in calculating profit, loss, selling price, purchase price, etc. This is known as social arithmetic (Nay, 2023).

For the 3,000 inhabitants of Lamalera, whales are a blessing sent to sustain the life and cultural heritage of the village, which has been passed down through generations and preserved through its traditions and customs. In addition, the community's supplementary livelihoods include weaving ikat textiles and crafting artifacts from the leftover bones of whales, which are unique souvenirs.

The leftover whale bones are crafted into various souvenirs, including carvings, statues, bracelets, necklaces, or rings. Some parts of the whale's body are burned and made into oil for lighting the village or as souvenirs for travelers. Upon reaching the village, guests are greeted by a gateway made of whale bones. As they enter the village and walk through its streets, guests will see a variety of artifacts on either side of the road, some of which adorn the homes of the residents.

Upon entering Lamalera village, visitors are greeted by a row of whale skull bones, and they may also see whale skeletons on the beach in the village. Apart from the meat, whales that are captured also provide whale oil. When a whale is caught, the meat and oil are distributed to the entire village. The whale meat is then sold in the market through barter, exchanged for vegetables and fruits.

This description illustrates that the sea is a rich and important cultural space for the communities of Lamalera and Lamakera. In Lamalera, whale hunting is carried out by adult men who are considered to be competent. Before hunting, they offer prayers to God for success in the hunt. Whale hunting is done using wooden boats called "peledang". A lamafa, who is responsible for spearing the whale, stands at the end of the boat and uses a harpoon called "tempuling" to spear the whale. Whale hunting takes place in May and can last for hours. The fishermen wait for signs of whales surfacing before starting the hunt. Sperm whales (physeter macrocephalus) are the primary target, while blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) are never hunted. This is because there is a prohibition on killing blue whales and pregnant female sperm whales, whale calves, and whales in mating. The whale meat obtained from the hunt is consumed by the villagers and distributed according to the contributions of family members involved in the hunting process. Whale oil is also used as massage oil, medicine, and fuel.

5. Conclusion

The sea plays a crucial role as a cultural space for the Lamalera community. The intensity of interaction between the community of fishermen and the sea is so high that their civilization and identity are largely determined by it. The sea is not only a source of livelihood and cultural identity but also a place to preserve traditions, build spiritual relationships, and conserve nature. Traditional knowledge of sea navigation is passed down from generation to generation to determine the position of boats, wind direction, as well as migration patterns and behavior of whales. This knowledge is a crucial part of their daily lives and strengthens their relationship with the sea. The sea also plays an important role in the beliefs and rituals of the Lamalera community. Before setting out to catch whales, they perform prayers and rituals aimed at success and safety in the hunt. The sea is considered a blessed source of life and is respected through ritual ceremonies.

The death of the youngest lamafa, Benyamin Kleka Blikololong, in his love and struggle to live in Lamalera, clearly demonstrates that the sea is indeed a cultural space that needs attention. In this space, there are humans struggling to live amidst natural limitations and endangered species. Both cannot be ignored. Human suffering must be ended, and rare species need to be protected.

A deep understanding of the sea as a cultural space has led the International Whaling Commission to define whaling in Lamalera as traditional whaling (aboriginal subsistence whaling) that is allowed to be carried out (Brown, 2015). The Indonesian government has classified whales and dolphins as protected species that are prohibited from being hunted (Government Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia No. 7 of 1999 concerning the Conservation of Plant and Animal Species). To date, the Indonesian government has not had regulations on traditional whaling, leading to endless debates on conservation and concerns among the community. The Indonesian government is advised to promptly establish regulations that define what is meant by aboriginal subsistence whaling, considering both positive law and customary law aspects, and how formal regulations allow traditional fishermen to catch protected species.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Productive Innovative Research Funding (RISPRO) from the Education Fund Management Agency (LPDP) under agreement number: 74/IV/KS/05/2023 and 036 Penel./LPPM-USD/V/2023 dated May 8, 2023, regarding the Implementation of Research and Innovation Program for Advanced Indonesia Wave 3 for the research titled "The Sea as a Cultural Space: Exploration, Optimization, and Innovation of Maritime Cultural Heritage Tuba Feda in Lamalera and Lamakera, East Nusa Tenggara." The research team would like to express their gratitude and appreciation to the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN).

Bibliography

- Alaini, Nining Nur, 2018. “Kosakata Budaya Tradisi Penangkapan Koteklema di Lamalera in Novel Suara Samudra, Catatan Dari Lamalera Sebagai Salah Satu Alternatif Pengayaan Kosakata Bahasa Indonesia.” Jurnal Mabasan, Vol. 12, No. 2, Juli—Desember 2018: 122–136

- Barnes, R.H. 1996. Sea Hunters of Indonesia: Fishers and Weavers of Lamalera (Oxford Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology). Oxford-Inggris: Clarendon Press.

- Batafor, E.M.D., Sunarta, I.N. 2017. “Identifikasi Potensi Wisata di Kampung Nelayan Tradisional Desa Lamalera.” Jurnal Destinasi Pariwisata, 5 (1): 66–71.

- Basri, Sri Idawati, 2021. “Lamakera, Desa Pemburu Paus di Pulau Solor” . Kompasiana, 2 Maret 2021.

- Berkes, F. (1999). Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource management. Taylor & Francis.

- Boli, Barnabas, 2018. “Tradisi Penangkapan Ikan Paus Pada Masyarakat Nelayan Lamalera Kabupaten Lembata, Nusa Tenggara Timur.” Jurnal Ilmiah Tarbiyah Umat, 8 (1): 81–98.

- Brown, Taylor Kate 2015. “Hunting whales with rowing boats and spears” in BBC News Magazine, 26 April 2015.

- Brydon, Anne, 2006. “The Predicament of Nature: Keiko the Whale and the Cultural Politics of Whaling in Iceland.” Anthropological Quarterly , Spring, 2006, Vol. 79, No. 2 (Spring, 2006), pp. 225- 260. The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4150998

- Bulbeck, Chilla and Sandra Bowdler, 2008. “The Faroes Grindadráp or Pilot Whale Hunt: The Importance of Its 'Traditional' Status in Debates with Conservationists.” Australian Archaeology, Dec., 2008, No. 67, More Unconsidered Trifles: Papers to Celebrate the Career of Sandra Bowdler (Dec., 2008), pp. 53–60. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40288022

- Corsi, Pietro. 2017. “The Sea in History: The Modern World" Journal of the History of Biology, Vol, 38, Number 1 (March, 2005) DOI 10.1007/s10739-004-6510-5

- Drew, G. (1998). Traditional ecological knowledge in marine resource management. Arctic, 51(3), 279–292.

- Duncan, J. S., & Ley, D. 1993. “Introduction: Between Center and Periphery” In Place/Culture/Representation (pp. 1–30). Routledge.

- Heizer, Robert F., 1943. “A Pacific Eskimo Invention in Whale Hunting in Historic Times”. American Anthropologist, Jan.–Mar., 1943, New Series, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Jan.–Mar., 1943), pp. 120–122. Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/662869

- Kaplan, Sidney. 1953. “Lewis Temple and the Hunting of the Whale.” The New England Quarterly, Mar., 1953, Vol. 26, No. 1 (Mar., 1953), pp. 78–88. The New England Quarterly, Inc.

- Lyutskanov, Yordan 2020. “Black Sea as Literary and Cultural Space: State of the Art and Prospects” in Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies — Volume 6, Issue 2, April 2020 – Pages 119–140. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajms.6-2-2 doi=10.30958/ajms.6-2-2

- Mustika, Putu Liza, 2019. “Perburuan Tradisional Lamalera Bisa Lestari. Dua Langkah Awal Bisa Diambil” in The Conversation. Diundah tanggal 16 Maret 2024 dari https://theconversation.com/perburuan-tradisional-paus-lamalera-bisa-lestari-dua-langkah-awal-yang-bisa-diambil-120892

- Nay, Florianus Aloysius, 2023. “Aspek Etnomatematika Pada Budaya Penangkapan Ikan Paus Masyarakat Lamalera Kabupaten Lembata Nusa Tenggara Timur” in Prosiding Seminar Nasional Etnomatnesia (356–366). ISBN: 978-602-6258-07-6

- Paine, Lincoln. 2014. The Sea and Civilization: A Maritime History of the World. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

- Parlangeli, Oronzo. 2019. Oceanic Culture History: The Adventure of Human Relationship in New Geographical Literature and Maps Vol. 2, No. 17 (June 1959). pp. 261–308. The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers

- Radovanovic, Bojana (2015). The Sea as Cultural Space: The Example of the Mediterranean

- Roberts, Christina, 2010. “Treaty Rights Ignored: Neocolonialism and the Makah Whale Hunt” The Kenyon Review, WINTER 2010, New Series, Vol. 32, No. 1 (WINTER 2010), pp. 78–90. Kenyon College. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40600263

- Steenbrink, Karel. 2006. Orang-Orang Katolik di Indonesia 1808–1942: Pertumbuhan yang Spektakuler Dari Minoritas yang Percaya Diri, Jilid 2. Maumere: Penerbit Ledalero.

- Strang, Veronica. 2014. Water: Nature and Culture. London: Reaktion Books; University of Chicago Press.

- Sujarweni, W. 2018. Metodologi Penelitian. Yogyakarta: Pustaka Baru Press.

- Taum, Alexander Paulus, 2019. “Tradisi Berburu Paus Biru Telah Bergeser di Lamakera” in Media Indonesia, 4 September 2019.

- Taum, Yoseph Yapi, 2023a. “Lamafa: Heroisme yang Tak Bakal Pudar” in Dari Prolog ke Epilog Sehimpunan Esai Sastra. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Lamalera.

- Taum, Yoseph Yapi, 2023b. “Cibta dan Pengkhianatan di Tanah Leluhur: Catatan atas Puisi-puisi Lamaholot Bruno Dasion” in Dari Prolog ke Epilog Sehimpunan Esai Sastra. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Lamalera.

- Tube, Bernardus. 2017. Tradisi Lisan Lia Asa Usu sebagai Potret Jati Diri. Masyarakat Lamalera: Sebuah Kajian Etnopragmatik. Tesis Magister. Yogyakarta: Universitas Sanata Dharma.

- Van Ginkel, Rob, 2004. “The Makah Whale Hunt and Leviathan's Death: Reinventing Tradition and Disputing Authenticity in the Age of Modernity.” Etnofoor, 2004, Vol. 17, No. 1/2, Authenticity (2004), pp. 58–89. Stichting Etnofoor. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/25758069