The Imagination of a Transoceanic Island: From Letter from Okinawa to Okinawa Spy

Abstract

This study examines the methods and aspects of literary representation of the Japanese island Okinawa, focusing on the novels of authors Kim Jeong-han and Kim Soom. Okinawa is noted as a locale that shares a similar history with Korea, as both regions suffered under Japan’s colonial rule. Beyond this, however, Okinawa is also a place that invites broad reflection on the East Asian context of various themes, such as barbarism and violence, perpetration and victimization, and dominance and subjugation. In light of this, Kim Jeong-han and Kim Soom sought to portray Okinawa not merely as a place confined to historical memory, but as a symbolic space that reflects on the contemporary contexts of exclusion, violence, and hatred. This is accomplished by exploring such issues as state violence, gender oppression, and racial discrimination, which persist even in the 21st century. Through Okinawa, the authors aimed to uncover the overlapping structures existing between imperialism and colonialism. They also sought to suggest new possibilities for trans-locality by intersecting and expanding the historical experiences and events rooted in Okinawa into Korea, Japan, and the U.S. The reason Okinawa could serve as a hub of trans-locality lies in its geographical location at the southern tip of the Japanese archipelago and its experience of being an internal colony under Japanese rule. However, the manifold layers of differentiation and the presence of complex others within Okinawa also give it multiple identities, challenging the island to seek out new ways of thinking by constantly traversing, intersecting, and defying boundaries. Therefore, this study assesses how these various experiences, practices, and contemplations formed around Okinawa may offer points of academic inspiration and reflection for East Asia and the world in the future.

Keywords

Okinawa, Korea, Colonialism, Racism, Trans-locality, Literary represention, Trans-locality

Introduction

In modern Japanese history, Okinawa holds a unique position, as it is both part of Japan and yet distinct from it. Before its forced annexation by Japan in 1879 through the Meiji government’s Ryukyu Disposition, Okinawa had maintained its independence as the Ryukyu Kingdom. However, after being incorporated into the modern Japanese state, Okinawa faced economic underdevelopment and social discrimination.

In particular, the Battle of Okinawa during the Pacific War remains one of the most tragic episodes in history. As Japan’s defeat became more apparent, the ruling class began preparing for a grand assault on the mainland to negotiate peace on the condition of preserving the emperor system. This led to Okinawa becoming the only place in Japan to experience ground warfare. As a result, approximately 65,000 mainland soldiers, 200,000 Okinawan soldiers and civilians, and 10,000 Koreans lost their lives(Arasaki, 2005).

In fact, more civilians than soldiers died during the conflict. This is because the Japanese military, regarding Okinawan residents as potential spies for the U.S. military, responded by torturing and massacring them. With the clashes between the Japanese and American forces, along with the massacres carried out by the Japanese military, nearly one-third of Okinawa’s total population lost their lives during the war.

After Japan’s defeat, Okinawa came under the direct control of the U.S. armed forces and was made the U.S.’s military stronghold in East Asia, hosting about 75% of U.S. military bases in Japan. In response to this postwar situation in Okinawa, the Japanese mainland remained consistently indifferent and, at times, even actively discriminated Okinawa(Shindo, 2002). In 1972, Okinawa was returned to the Japanese mainland, but Japan’s contradictory policies, the scars of war, and the tensions of the U.S.-led cold war system still remain to this day. From this perspective, it would be accurate to say that the postwar period has yet to arrive for Okinawa.

The war, defeat, and the aftereffects that Okinawa experienced are, in many ways, fundamentally different from those of the Japanese mainland. In fact, Okinawa’s history and experiences more closely resemble those of colonial Korea. Due to Japan’s forced colonial rule and the burdens of war, both Korea and Okinawa had to endure a shared history of violence and barbarism, including the mobilization of labor and sexual exploitation, the destruction of their respective cultures, and racial discrimination.

In Korean literature, the first figure to insightfully capture the shared colonial legacy between Okinawa and Korea was Yosan Kim Jeong-han (1908–1996). In November 1977, Kim published a short story titled Letters from Okinawa in the magazine Munye Joongang. Based on the historical dispatch of Korean seasonal workers to Okinawa between 1973 and 1976, Kim’s story is imbued with a strong sense of realism and vividness. Furthermore, Okinawa’s complex colonial structure, which is marked by ambivalent feelings that vacillate between sympathy and understanding toward Korea and despising and excluding Korea like the Japanese mainland, clearly highlights the dual colonial issues that Okinawa faces.

In 2024, decades after Kim Jeong-han’s Letters from Okinawa was published, author Kim Soom published Okinawa Spy, a novel that deeply delves into the horrific massacre that occurred on an Okinawan island near the end of the Pacific War. The novel depicts how local Okinawan residents and the Japanese military conspired to falsely accuse a Korean family of junk dealers of being spies, resulting in their brutal massacre. Amidst the ongoing horrors of war, blind power, extreme distrust that permeated the local community, and merciless massacres that manifested as a result, the novel forces readers to once again realize that the biggest victims were the “others.” These “others” were those who were positioned at the lowest rungs of society and who were both ethnically and socially marginalized. In summary, both Kim Jeong-han and Kim Soom’s works bring Okinawa into the realm of Korean literature; they both highlight issues relating to the ambivalent emotions that existed between Okinawa and Korea, as well as the complex structures of discrimination that encompass the mainland Japanese, Okinawan, and Korean societies. In other words, Okinawa, as a site of multilayered historical memory, serves as a bridge between Korea and Japan, as it connects the past and present of both countries, as well as individuals, communities, and functions of the island. Therefore, this study will focus on the possibilities of trans-local connections that Okinawa reconstructs, as explored through these two works.

2. Okinawa as a Hub of Movement and Intersection: Kim Jeong-han’s Letters from Okinawa

Kim Jeong-han’s Letters from Okinawa was published in November 1977 in the magazine Munye Joongang. Set in the Korea of the mid-1970s, the novel unfolds as an epistolary narrative of a young seasonal laborer in Okinawa who writes letters to her mother in Gangwon Province.

Bok-jin, a young woman from a mining village in Gangwon Province, has left her hometown to work as a seasonal laborer on a sugarcane farm on Minamidaito-jima, Okinawa. Through the introduction of a Korean association that recruits poor young people for seasonal work in Japan, Bok-jin and her friends are shipped to Japan like cargo. Hayashi, the owner of the farm where Bok-jin works, was conscripted to a coal mine in Hokkaido during the war and was dispatched to Rabaul just before Japan’s defeat. Having experienced forced labor and military service under the Japanese Empire, Hayashi is empathetic to the plight of Korean women who, like him, hail from a colonized land. Hayashi’s son, Takeo, holds a critical view of Okinawa’s situation, to the point of participating in protests against U.S. military bases on the island. He strongly criticizes not only Japanese imperialism, but also the imperialism and militarism of the U.S. Thus, he expresses both understanding and sympathy for the situation of laborers like Bok-jin. Meanwhile, as Bok-jin learns about the humiliating experiences of forced miners and comfort women during the war, as well as the shameless actions of Korean intellectuals who incited them, she again realizes that the lasting scars from that period still linger in the 1970s in the form of seasonal labor and sex tourism.

This work has been highly praised for its pioneering insight into both the similarities and differences in the colonial legacies experienced by Okinawa and Korea(Cho, 2010; Yim, 2013; Shin; 2019). It is often described as the only exceptional novel in Korean literature that seriously explores Okinawa as a setting(Ha, 2019), and one that raises post-colonial issues within an East Asian context by positioning Okinawa as a place that shares the region’s memories of imperialism and colonization(Lee, 2021).

As previous research has brought to light, the connection between Okinawa, an exotic and unfamiliar remote island, and Korean literature stems from the shared experiences of Okinawa and Korea’s colonial pasts. However, what cannot be overlooked in this work is the mobility of the characters. In conclusion, it is through this mobility that Okinawa and Korea either encounter or elude each other. This ambivalent intersection of encountering and eluding one other ultimately reveals the distance that exists between Okinawa and Korea. To explore this theme further, this study first examines the journey of Hayashi, the elderly Okinawan character.

Hayashi, the owner of the farm where Bok-jin works, once worked as a coal miner at Hokutan in Hokkaido during the war. It is widely recognized that Okinawa is Japan’s southernmost point, while Hokkaido is its northernmost. The distance Hayashi traveled, vertically crossing the entire length of the Japanese archipelago, would have been nearly impossible without the compulsion of wartime mobilization. After returning from Hokkaido to his hometown in Okinawa, he was soon mobilized again, crossing the sea to Rabaul in Papua New Guinea. Simpson Harbor in Rabaul served as the headquarters of the Japanese Navy during its advance into the South Pacific in the Pacific War, and the so-called “Southern Front” was established around this area. In 1944, a large-scale battle took place between U.S. and Japanese forces over Rabaul, making it one of the fiercest battlegrounds between the two nations. In light of this, it can be inferred that Hayashi’s war experience was equally harrowing.

Hayashi returned to his hometown after the war, but his life had already been completely upended. The Battle of Okinawa had not only left the area in ruins, but also led to the land of the Okinawan people being forcibly seized under the pretext of constructing U.S. military bases. Due to these circumstances, Hayashi moved to Minamidaito-jima, a remote island far from Okinawa’s main island, where he continued his life as a sugarcane farmer. Hayashi’s journey, spanning Okinawa, Hokkaido, back to Okinawa, Rabaul, Okinawa again, and finally Minamidaito-jima, symbolizes the harsh reality of the people of Okinawa (which can be likened to Japan’s internal colony), who were forced to endure harsh relocations under the oppressive commands of Imperial Japan. These forced relocations, which threatened the survival of the oppressed, who often teetered on the brink of life and death, were emblematic of the reality of Okinawa, whose autonomy had been completely stripped away.

What is intriguing is that Bok-jin’s father was also conscripted to Hokkaido during the late Japanese colonial period, where he worked as a coal miner. After hearing the story of Bok-jin’s father, Hayashi could not help but express his surprise at their strange connection, as he wonders if he and Bok-jin’s father might have crossed paths in the coal mine. When one recalls that both Hayashi and Bok-jin’s father, who were conscripted to Hokkaido from Okinawa and Korea, respectively, were colonial subjects at that time, one can conclude that these two characters were continually forced to relocate and be reassigned at the demands of the Empire.

However, one important point to note here is that while both Korean seasonal laborers like Bok-jin and Okinawans like Hayashi’s family experienced migration for survival and subsequent discrimination, there was still a clear distinction between the two. For instance, even when Hayashi comprehends Bok-jin’s situation, he would sometimes assert his position as a Japanese subject, seeking to distance himself from being identified with the plight of Koreans.

To confirm this idea, it will be necessary to examine the scene where Hayashi vividly describes the treatment Korean laborers received in the coal mines in Hokkaido. Hayashi recalls that the Japanese showed their contempt by calling the Korean laborers “tako” (octopus) and referring to the Korean dormitories as “takobeya” (octopus barracks). He also remembers how the Korean laborers were beaten severely as if they were dogs, and if they were injured and needed time for treatment, they were abandoned after being insulted severely. By sharing anecdotes that likened Koreans to octopuses, based on the notion that octopuses had empty heads, and alluding to violence inflicted against Koreans as if they were animals, Hayashi, on one hand, expresses sympathy for Koreans, while on the other, reveals a desire to clearly distinguish himself from them. In other words, Hayashi positions himself in a safe zone that Koreans can’t approach. From this position, he is able to portray the horrific tragedies that Koreans have endured, implicitly signaling that Okinawa and Korea stand on entirely different grounds. In this sense, both Hayashi and Bok-jin’s father experienced an ambivalent intersection of encounters and divergences in Hokkaido.

Next, it would be pertinent to focus on Bok-jin’s mobility in the novel. Bok-jin’s account of the journey to Okinawa begins with the following line: “We seasonal laborers, exported from Korea, were carelessly loaded onto the ship like chunks of cargo, alongside other cumbersome baggage.(Kim, 2008)” The journey to Okinawa through Gangwon Province, Seoul, Busan, and then to Minamidaito-jima, as well as the image of young women being treated like cargo, brings to mind the so-called “comfort women” that Bok-jin’s mother feared becoming. In other words, the route and method of transport for young women like Bok-jin essentially replicated the movement of these comfort women. The frequent appearance of comfort women in the work can be interpreted as a way to draw a parallel between the reality of 1970s Korea, which was forced to send seasonal laborers abroad, and the history of forced mobilization during the Japanese colonial period. This passage also suggests that colonialism and postcolonialism perfectly overlap.

The character who points out this structure most clearly is Hayashi’s son, Takeo. He argues that true liberation for Korea has yet to arrive, as South Korean society remains economically dependent on or parasitic to Japan, though colonial rule had already been brought to an end diplomatically. Furthermore, he reminds the reader that the situations of munitions factory workers, comfort women serving the Japanese military during the colonial period, and young Korean women sent abroad to earn money are fundamentally the same. In short, Takeo is revealing the structure in which the processes of forced mobilization and the movement of seasonal laborers are repeated and reproduced. His remarks, made from the perspective of an outsider, deserve close attention as they highlight the contradictions existing within Korean society. This is because state violence, which continued to force young women into earning foreign currency-even after the end of colonial rule and in a manner similar to the forced mobilization taking place during the colonial period-represents a fragment of postcolonialism.

Bok-jin is not the only one who attests to the history of forced labor, which has become a repeating occurrence. This work also includes anecdotes about Korean seasonal laborers sent abroad to earn foreign currency, who do not receive their wages properly and suffer from the burdens of harsh labor. Additionally, this novel presents readers with stories of shops in Okinawa’s villages that skirt the island’s military bases and promote hostess parties and solicit customers. Then, there is the account of “Madam Shanghai,” a former comfort woman for the Japanese military who remains in Okinawa to run a bar and engage in methamphetamine trading. Such scenes remind the reader that seasonal laborers like Bok-jin are ultimately on the same continuum as hostesses and comfort women. Here, the very fact that this Korean woman is referred to as Madam Shanghai suggests a connection between colonialism and mobility. In other words, it is highly suggestive that this person, a Korean, was either forced to travel to Shanghai as a comfort woman for the Japanese military or that a pseudonym replacing her original name was assigned due to her close relationship with people from Shanghai.

The mobility of women such as Bok-jin and Madam Shanghai is shaped by the imposing influence of imperialism, nationalism, and androcentrism, which result in these women being forced to drift perpetually on the margins of society, resembling something akin to a diaspora. This is part of the old literary trope where the suffering of women resulting from the effects of war serves as an allegory for a wounded nation(Kwon, 2005). The positions of Bok-jin and Madam Shanghai also fit this paradigm, and the recurring appearance of colonialism that their existence signifies symbolizes an irreparable part of contemporary Korean history.

3. Doubt, Hatred, and Massacre: Kim Soom’s Okinawa Spy

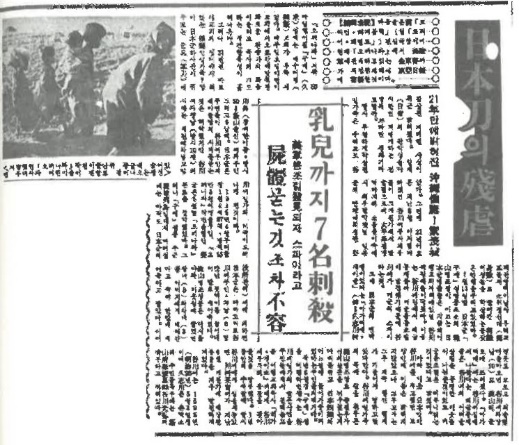

Kim Soom’s Okinawa Spy, published in 2024, is based on an incident that occurred during the Pacific War when Japanese garrison troops massacred 20 Okinawan residents who were accused of being spies. This event took place on the small island of Kumejima, and the victims included Gu Jung-hoe, a Korean.

The novel begins with the killing of nine people at a cattle ranch in the northern village of Kumejima, where Gu Jung-hoe lived, before the deaths of Gu’s family members took place. These people were accused of being spies for the U.S., and were ultimately slaughtered, simply because they had been abducted by U.S. forces and later released. This incident suggests the level of conflict and animosity that was present in Okinawa at that time.

To understand the psychological background of the paranoia surrounding potential spies, it is essential to grasp the circumstances in Okinawa at that time. Okinawa was originally an independent island with a distinct ethnic identity known as the Ryukyu Kingdom, and was wholly separate from the Japanese mainland. When Japan forcibly annexed it, Okinawa was suddenly relegated to the status of a colony, with the populace becoming second-class subjects.

As Okinawa’s geographical location made it suitable for defending the Japanese mainland, a significant number of Japanese troops were stationed there during the Pacific War. Many laborers forcibly brought from Korea, as well as comfort women for the Japanese military, also migrated to Okinawa. In addition to Koreans, Okinawans were also mobilized to augment the capabilities of Japanese forces and aid in militarization. Within this context, a hierarchy began to emerge among the Japanese military, Okinawans, and Koreans. Hierarchies were established between soldiers and civilians, Japanese, Okinawans, and Koreans, men and women, those who were protected and those who were not, and perpetrators and victims. These hierarchies became intertwined, leading to the rapid dissemination of extreme forms of discrimination and hatred(Ikemiya, 1980).

In Okinawa, where only collective madness remained due to the war, people sought out and killed those they perceived as weaker. Among them, Koreans became the easiest targets for massacre, as they were depicted as the most inferior ethnic group, even in Okinawa. For this reason, Okinawans constantly emphasized the differences between themselves and Koreans to avoid being categorized in the same group. In other words, those whose most urgent mission was to prove themselves as subjects of the Empire attempted to protect themselves by discriminating against and despising Koreans(Oh, 2019; Tomiyama, 1995). The desire of Okinawans Hayashi and Takeo to distinguish themselves from Koreans like Bok-jin in Kim Jeong-han’s novel, as discussed earlier, can be said to fit this historical background.

In Kim Soom’s Okinawa Spy, the swift accusation of Koreans being spies is a direct result of ethnic discrimination. The character who oversees the massacre in this work is Kimura, the general officer of the Japanese garrison stationed in Kumejima. Under his orders, soldiers and teenage Okinawan boys, known as “human hunters,” roam throughout the island and brutally kill people. By strictly obeying Kimura’s orders, the Okinawan boys believed they could escape their status as second-class subjects and become respectable subjects of the Empire.

It is quite significant that the boys are referred to by names of animals such as weasels, raccoons, squirrels, and moles. While these names can be viewed as nicknames derived from each boy’s appearance or personality, they can also be interpreted as symbolizing the process of massacre, where humanity is concealed behind the names of animals and a predatory instinct is used to root out spies. The boys, often immature in their judgment, while being instilled with a hero complex and easily swept up in collective madness, thus become dehumanized and monstrous in this way. Furthermore, these boys felt they could free themselves from suspicion of being spies by joining the “human hunters.” This tragic cycle forces them to constantly suspect, hunt down, and kill others to secure their freedom, which embodies the living hell created by war.

In fact, the category of those considered spies was largely predefined. Individuals who picked up U.S. propaganda, women who had been raped by American soldiers, those who had been captured and released by the U.S. military, those who spoke Okinawan dialects, and those who ate better food than the soldiers were all immediately at risk of death if they had even the slightest connection to the U.S. or spoke a language that was difficult for the Japanese military to understand. This situation was largely the result of General Kimura’s position as both the enemy of U.S. and an overseer of the internal colony of Okinawa. While it is understandable for the Japanese to consider the U.S. an enemy during the war, it may seem perplexing to label Japanese citizens, the Okinawans, as spies. However, when examining Okinawa’s status in modern and contemporary Japanese history, this phenomenon can be seen as entirely natural. Given the deep-rooted discrimination and contempt toward Okinawa that had been building up over time, there was widespread suspicion and anxiety among the Japanese military that Okinawans might side with the U.S. by revealing Japan’s military secrets and taking up arms against the Empire. In other words, the Japanese military was under the delusion that “all Okinawans are spies,” which led to the entire region of Okinawa being enveloped in a state of “spy paranoia.”(Oh, 2019) As Okinawans were regarded as potential spies, the slightest suspicion could turn them into victims of an immediate massacre. This forces people to actively root out and report new spies to avoid suspicion of being spies themselves(Tomiyama, 2009). As indicated by its title, Okinawa Spy explores the Japanese military’s paranoia regarding spies while delicately depicting Okinawan residents who were swept up in this atmosphere of paranoia that designated the weak as being spies.

As a consequence of such an atmosphere, the people of Okinawa are continually weighed down by fears and anxieties relating to potential spies, whether they themselves are under suspicion, and who will be targeted next on the small island. This environment naturally becomes one of mutual surveillance in which people continuously suspect and accuse one another. They then realize that the most effective way to ensure their own safety is to find a target that can shield them from the arrows of madness. Just like the aforementioned “human hunters,” people were willing to partake in killings to prove that they were not spies. Notably, the most impactful sacrifice in this novel was that of the family of seven Korean junk dealers.

Although one of these family members takes the form of a Korean junk dealer in the novel, he is clearly based on the historical Gu Jung-hoe. This character lived on the main island of Okinawa and, after marrying an Okinawan woman, moved to Kumejima, where he makes a living collecting junk. He has not been associated with the U.S. military, nor has he ever been detained by them. In other words, there are no elements of his background that could arouse suspicion of him being a spy. If one were to argue otherwise, it is possible that he might have been viewed as a suspicious figure for wandering around the village in search of junk.

In the case of Gu Jung-hoe, surprisingly, it was an Okinawan neighbor who identified him as being a spy. Though he used a Japanese name, everyone in the community knew that he hailed from the Korean Peninsula. One of the residents reported that he was in collusion with the U.S. military, and upon learning this, General Kimura immediately issued his death warrant. The only reason for labeling Gu Jung-hoe as a spy is the fact that he was a Korean. To secure their own lives, Okinawans simply pointed fingers at Koreans as being spies. In Okinawa, even if one was a familiar neighbor, being identified as Korean was enough to make them a target for denunciation at any time. Thus, the Gu Jung-hoe incident vividly illustrates the pervasive colonial atmosphere in Okinawa.

In such a backdrop consisting of suspicion, hatred, and massacre shaped by colonialism and racism, the family of Korean junk dealers struggles desperately to shed their background. In this situation, where blatant discrimination and contempt towards Koreans are rampant, and where even lives are at stake, the eldest son of the junk dealer, Fumio, asks his mother, Fumi, whether he is Korean or not. Fumi responds to her son by saying, “You are Okinawan. An Okinawan Japanese.(Kim, 2024)” Despite Fumio’s father being Korean, she hides her son’s true identity from him by denying his Korean heritage and asserting that he is an Okinawan Japanese.

In fact, this identity crisis was a fundamental aporia for the Korean junk dealer couple. Fumi, an Okinawan woman, dressed like a mainland Japanese woman, spoke Japanese, and laughed and cried like a Japanese woman, yet she could never hide her Okinawan identity. She confessed that the more she tried to dress like a Japanese woman, the more despairingly she realized her identity as an Okinawan. Having been abandoned by a man from the Japanese mainland in her youth, Fumi later married a Korean, had children, and chose to live in Okinawa. Fumi, who is now married to a Korean, and Fumio, the eldest son who dislikes Koreans and does not want to identify as one, represent the situation of overlapping discrimination that exists among Japanese, Okinawans, and Koreans.

On the other hand, the Korean junk dealer believes that if he has any faults, they stem solely from the fact that he is Korean. Forced to feel ashamed and guilty about being a stranger migrating to and living on the island, where Okinawans make up the majority, he ironically tried to ignore and avoid other Koreans. This is in stark contrast to how he treated Okinawans. Whenever a Korean walked by, he would deliberately lower his head to avoid making eye contact. He would also walk around anxious that a fellow Korean might speak to him, due to his obvious Korean appearance. This Korean junk dealer’s psychological state is the result of internalizing the ethnic hierarchy prevalent in Okinawa. Because of this, he places himself as a target of contempt and discrimination, fearing that his identity might be revealed externally.

This couple, consisting of a Korean man and an Okinawan woman, sensed a kinship with each other as outsiders living within the Japanese Empire. At the same time, however, they were burdened with the task of imitating Japanese and being identified with imperial Japan. The fact that this task ultimately ended in failure is evident in the outcome of their family being labeled as spies and their entire household being murdered.

The last point to mention is the timing of the family’s murder. Following the Japanese Emperor’s declaration of surrender, General Kimura must have known of Japan’s defeat. However, he continued the massacres even after, stating, “No one can end this war before I die.(Kim, 2024)” The murder of the Korean junk dealer’s family also took place on August 20, five days after the surrender. As a result of General Kimura continuing the war on his own even after Japan’s surrender, 20 innocent people were sacrificed on Kumejima. The relentless spy hunts that showed no signs of ceasing even after Japan’s defeat are not confined to the story within this work. They are a stark reminder of the hate crimes that repeatedly occur in modern society in various forms. In addition, this story also serves as a reminder that the targets of such hate crimes have always been those who were pushed to the margins of society.

4. Conclusion

This study examined the methods and aspects of literary representation of Okinawa, focusing on the novels by the authors Kim Jeong-han and Kim Soom. The modern history of the Korean Peninsula passed through the common spatiotemporal context of East Asia. This includes the periods of Japanese colonial rule and subjugation, war and liberation, and the ensuing Cold War and modernization, when the peninsula underwent the process of being incorporated into the U.S.-led Cold War order. Okinawa, as a frontier where the hardships of East Asia’s modernity and its subsequent traumas are deeply etched, serves as a mirror reflecting the historical tragedies of the Korean Peninsula.

The way in which Okinawa traverses the sea to connect with Korean literature is highly significant. Okinawa, serving as a literary setting in Kim Jeong-han’s A Letter from Okinawa and Kim Soom’s Okinawa Spy, is not merely confined to being a historical site where the contradictions of colonialism are concentrated. Okinawa is expanded into a symbolic space that prompts reflection on the numerous contemporary contexts of exclusion and hatred, encompassing such issues as state violence, gender oppression, and racial discrimination. Most importantly, both works are based on real events, such as Korea’s export of laborers and the massacre of ethnic Koreans. In these works, Okinawa is not merely a fictional space across the sea, but is reproduced as a concrete site where individual lives are intertwined.

In this way, Okinawa breaks down the boundaries between nation-states and represents how modern and contemporary East Asian history intersects. As a frontier at the southernmost edge of the Japanese archipelago and an internal colony of Japan, Okinawa offers new opportunities for recognition and the ascription of meaning based on such experiences, which can also be extended to Korea, mainland Japan, and East Asia as a whole. In that sense, Okinawa can be defined as a transversal, transactional, translational, and transgressive place (Ong, 1999). Furthermore, Okinawa is very useful as a resistance strategy for reshaping the existing local order and it makes it possible to take a fresh look at the local from a network perspective(Cox, 1998). There are great expectations as to how the various experiences, practices, and contemplations formed around Okinawa will provide points of academic inspiration and reflection for East Asia and the world in the future.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Pukyong national University Industry-university Cooperation Research Fund in 2023 (202312320001).

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2024S1A5A2A01023703).

References

- Arasaki, M. 2005. Modern history of Okinawa. Iwanamishinsyo, Tokyo.

- Cho, J. M. 2010. Postwar Memories of Okinawa. JALALIKA. 45. 327–342. DOI: 10.18631/jalali.2010..45.019

- Cox, K. R. 1998. Spaces of Dependence, Spaces of Engagement and the Politics of Scale, or: Looking for Local Politics, Political Geography 17(1); 1–23.

- Ha, S. I. 2019. Kim Jeong-han’s novel and Asia : Vietnam, Okinawa, South Sea Islands. The Review of Korean Cultural Studies. 68. 101–127. DOI: 10.17329/kcbook.2019.68.68.004

- Ikemiya, K. 1980. War and Okinawa. Iwanami Junior Shinsyo, Tokyo.

- Kano, M. 2011. Think about the postwar history of Okinawa. Iwanamisyoten, Tokyo.

- Kim, J. H. 2008. The complete collection of Kim Jeong-han. Jakgamaul, Busan.

- Kim, S. 2024. Okinawa Spy. Moyosa. Seoul.

- Kwon, M. A. 2005. Fantasy of empire and ethnograpy of "Nambang (southeast Asia)" produced in Korea during Pacific war. The Leaned Society of sanghur’s Literature. 14: 327–361.

- Lee, M. W. 2021. Korean post-colonialism discovered in Okinawa in the 1970s - Based on Kim Jeong-han"s "Letter from Okinawa"(1977). The Korean Literature and Arts. 39. 59–95. DOI: 10.21208/kla.2021.09.39.59

- Oh, S. J. 2019. Between Okinawa and Korea-On the history and narratives of visualizing/invisualizing Koreans. Somyong. Seoul.

- Ong, A. 1999. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality, Uurham: Duke University Press, State of North Carolina.

- Shin, H, S. 2019. Okinawa's dual identity and encountering the viewpoints of discrimination: Focusing on seasonal labourers in the 1970s. Comparative Japanese Studies. 46. 53–70. DOI: 10.31634/cjs.2019.46.053

- Sindo, E. 2002. A divided territory- Another post-war history. Iwanami Gendaibunko, Tokyo.

- Tomiyama, I. 1995. Memories of the Battlefield. Nihon Keizai Hyoronsha, Tokyo.

- Tomiyama, I. 2009 “Spy” : Mobilization and Identity in Wartime Okinawa, SENRI ETHNOLOGICAL STUDIES. 51: 120–132. DOI: 10.15021/00002870

- Yim, S. M. 2013. Transbordering Mass: Okinawa experience of Korean female workers and its literary representation. Journal of Korean Modern Literature. 50: 105–139. DOI: 10.35419/kmlit.2013..50.004