Sakhalin Island in the Soviet and Russian Audiovisual Text

Abstract

Sakhalin is the largest island of the Russian Empire, the USSR, and now of modern Russia. This is why its audiovisual representations encompass various aspects of life, centering on different social problems and combining descriptions and depictions of natural features. The comprehension of this region began with Anton Chekhov, who visited in the late 19th century. Through his own observations, Chekhov presented a unique perspective on the social problems of Sakhalin, which then served as a place of exile. He also brought a collection of photographs (works by Innokenty Pavlovsky among them), depicting everyday scenes of convicts, including their shackling. The visual representation of the local indigenous peoples’ lives and traditions also dates back to the 19th century.

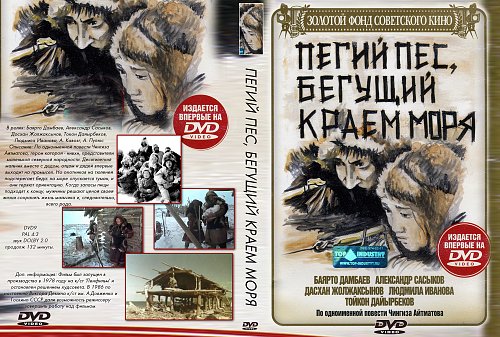

During the Soviet era, Sakhalin saw the production of highly skilled documentary films showcasing the island’s development, natural resources, and tension on the border; it also became the setting for several feature films. Noteworthy among the feature films of the late Soviet period is Karen Gevorkian’s adaptation of the novel, Spotted Dog Running at the Edge of the Sea, by Chingiz Aitmatov. It focuses on the small (about 4,500 individuals) Nivkh people,[1] incorporating documentary footage of their lives into the narrative.

In post-perestroika Russia, the focus shifted in feature films, including those about Sakhalin. Documentaries about the island experienced a resurgence as the state recognized its strategic importance. Numerous professional films were made, highlighting Sakhalin’s natural wealth and the lives of its residents on the edge of the world. And in the early 2000s, a new genre emerged: “people’s videos” created by islanders and travel bloggers. Although lacking a traditional plot, these films simply describe the authors personal encounters with the geographical reality of the island. However, both Soviet and post-Soviet documentaries occasionally revisit the theme of hard labor, as well as the persisting topic of challenges faced by small ethnic groups.

Keywords

Sakhalin, visual representation of the island, documentary photography and films, feature films, image of the island in Russian culture

1. Introduction

1.1 Geography and History

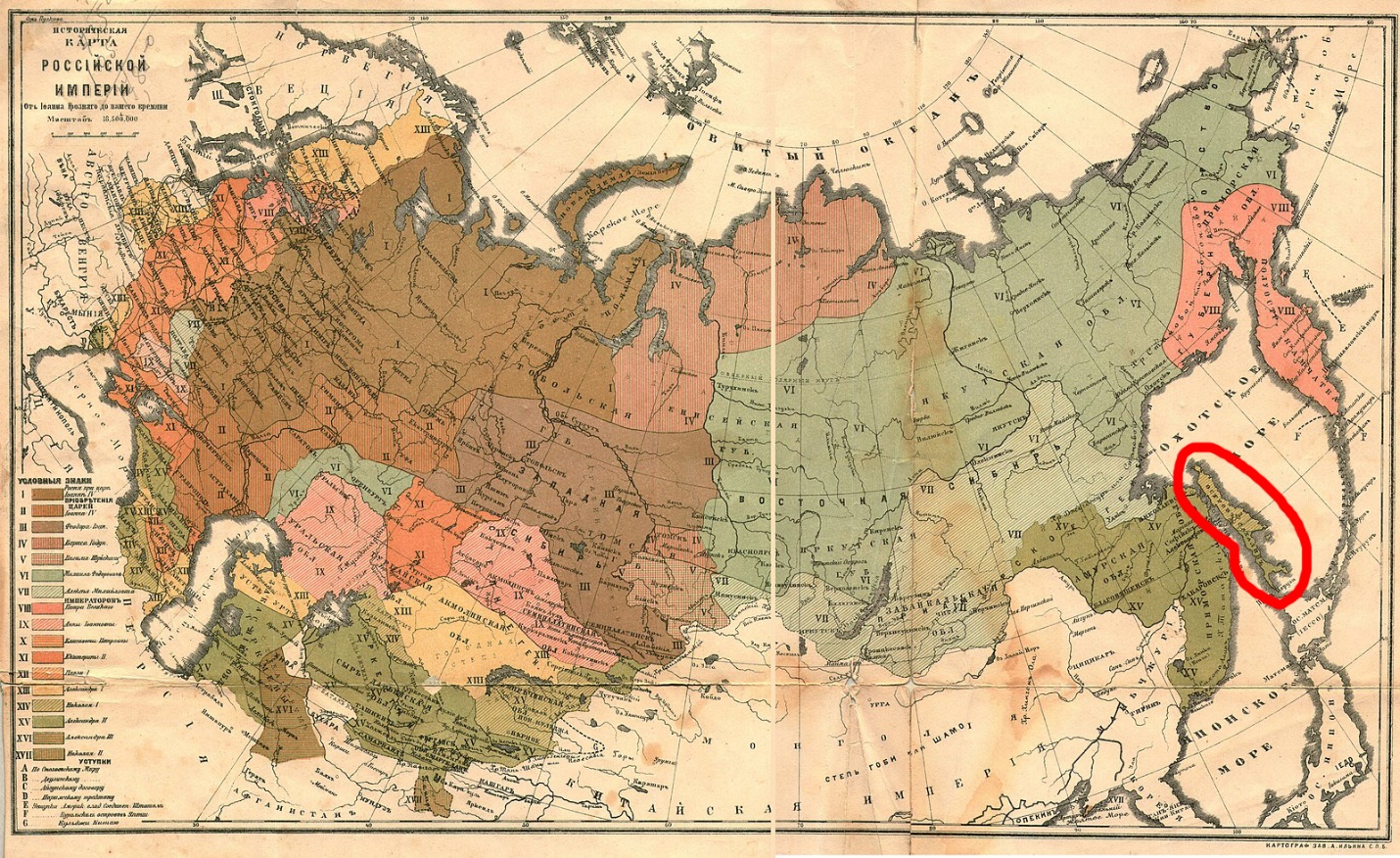

Sakhalin Island, the largest among the islands of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and modern Russia, is a multicultural territory where the cultural and historical discourse of being a “home for resettlers” is periodically contrasted with the local island culture. Although the territory of Sakhalin is equivalent in size to modern-day Czechia, it currently houses only 450,000 people. According to modern estimates, around 5,000 people, predominantly indigenous peoples, lived on the island in 1860, and the first official census, conducted by the writer Anton Chekhov in 1890, recorded as much as 28,000 inhabitants, mainly Russian settlers. Its role in the country’s life, its image, and living conditions have undergone changes throughout different historical periods, creating diverse audiovisual representations that explore various aspects of life and focus on different social issues, alongside descriptions and depictions of its natural features.

Sakhalin had been known long before it came under Russian jurisdiction (1853), as scientific expeditions, including the renowned navigator Ivan (Adam Johann von) Krusenstern (1805), explored its shores and surrounding waters. Initially considered a peninsula due to the inability of early expeditions to circumnavigate it from the north, the notion of Sakhalin as an island began to take hold and became ingrained in cultural understanding. The first images of Sakhalin also emerged. In the early 19th century, “the young Muravyov brothers, future Decembrists, dream of going to Sakhalin, which seems to them an uninhabited island (Robinson’s world!) and establishing an ideal republic called Choka. On the island, the brothers would start all human history anew: there would be no lords, no slaves, no money; they would live for equality, fraternity and freedom” (Lotman, 1994, p. 62; author’s translation).

However, the reality of the island’s development turned out to be far removed from the dreams of these young men who later participated in the December 1825 revolt at Senate Square in an attempt to abolish autocracy and serfdom in Russia.

Here is what Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921), a renowned geographer and anarchist, wrote about Sakhalin’s history:

Although its superficial area entitles it to occupy the first rank amid the islands of the globe, Sakhalin ranks amid the last in suitability for habitation. Novaya Zemlya and New Siberia[2] certainly lay behind it; but not many islands besides. It is, properly speaking, a link between the Japanese archipelago and the Kurilians, and Japan considered it as a part of its territory until the Russians established there, in 1853, their first military post in the southern part of the island. Three years later another post was settled at the Due coal-mines, opposite the mouth of the Amur. Russia thus took possession of the island, and it was explored by a series of scientific expeditions in the course of 1860 to 1867. (Kropotkin, 1906, p. 138)

It is noteworthy that the geographer compared Sakhalin to Novaya Zemlya and New Siberia, both located in the Arctic, beyond the Arctic Circle, with entirely different natural conditions. Sakhalin, covered in forests and lush vegetation, evokes the same sense of impossibility of its exploration as the tundras and polar deserts of the Arctic islands.

1.2 Necessity of the Study

This vast island has significant political importance in the modern history of Northeast Asia. Throughout the twentieth century, pivotal events unfolded on its soil, profoundly impacting the peoples of the three countries—Russia, Japan, and Korea, making it a “melting pot” of geocultural space. These events and images have been meticulously captured through photographs, documentaries, and cinematic works, collectively weaving a fresh visual and conceptual tapestry within the geocultural sphere. This narrative layer influences the interpretation of these processes and the island’s role within both Russian and global contexts, necessitating a special perspective.

1.3 Purpose

This study aims to conduct a comprehensive analysis and modeling of the portrayal of Sakhalin, as depicted in audiovisual texts spanning the eras of the USSR and contemporary Russia. The analysis is contextualized within the backdrop of real historical events, ideological trends, and the evolution of artistic expression in photography and cinematography (encompassing both feature films and documentaries, as well as grassroots content on platforms like YouTube and RuTube). This endeavor involves the parallel examination of events, their varied interpretations, and the construction of visual representations.

1.4 Hypothesis

The depiction of Sakhalin stands as a vital facet of Russian and Soviet cultural identity, influencing its self-definition along the Far Eastern frontiers. Over one and a half centuries, its image has evolved a structured narrative, where new layers of meaning have been superimposed upon the old, while early themes cyclically resurface for renewed contemplation.

The outlined objectives and aims are addressed within the framework of a holistic geocultural paradigm, recognizing that historical and cultural realities are deeply intertwined with geographic landscapes, which are themselves shaped and transformed by cultural influences across both informational and material realms.

2. Theoretical Framework

This study was conducted within the theoretical framework of cultural landscape and geocultural images, built among other things within the framework of semiotic analysis. The cultural landscape is a holistic phenomenon that encompasses the component of nature, the outcomes of human activities, and information—images of localities and spaces, semantics of geographical objects and toponyms—arranged in coherent systems that researchers can represent as a text (similar to culture in cultural studies). In this case, preference was given to audiovisual information, which, in turn, creates symbolic images of Sakhalin in the Russian mentality and integrates it into the country’s cultural landscape as a significant part, rich in emotions and meanings.

2.1 Geography and Culture

The key element in this iconic system is Sakhalin’s geographical position, which has shaped its history, geopolitical role, and representations over the last 150 years. Yuri Lotman, the founder of the Tartu-Moscow Semiotic School and one of the pioneers of cultural semiotics, considered space as one of the fundamental factors organizing not only the geographic and settlement aspects but also the cultural sign system, stating that “in spite of all the differences between the substructures of the semiosphere, these substructures are organized into a general system of coordinates: on the temporal axis into past, present and future, on the spatial axis into internal space, external space and the boundary between them” (Lotman & Shukman, 1990, p. 133). In this case, the geographical space as a semantic “locative” of Sakhalin and its historical development determine a system of cultural codes and constants, unchanging for the Russian mentality over the centuries. The island, as a frontier outpost on the one hand, and its contrast with the mainland on the other, appear within this system as a metacode that encompasses all other meanings and images. Space and place become a framework for creating visual images, highlighting the structures that organize and shape the local culture of Sakhalin and the island’s role in Russia’s geocultural space.

2.2. Geocultural Text as a Concept

Therefore, if we consider the cultural landscape as a text, then Sakhalin and its visual representations form an important chapter within it. The island, essentially, represents the easternmost frontier, which is crucial for Russia’s self-perception, not only as a land of vast territories but also in terms of asserting its development and the consolidation of its borders. Thus, the cycles of settlement and the cycles of comprehending Sakhalin and creating its visual images align closely. Each new wave of development brings a new visual representation, primarily aimed at the mainland. The visual images of Sakhalin are attuned to the external viewer, “connecting” the island to the empire functionally, symbolically, and informatively.

2.3. Imagery structure—Non-Center-of-the-World, Land’s Edge, Insula Firma

Sakhalin is an island with semantics and a place in the cultural landscape atypical of well-developed islands. Traditionally, the island is attributed with the quality of centrality in folk culture. Such a worldview is rooted in the archaic understanding of the island as the primal land, on the one hand, and as a contrast of the ever-changing island to steadfast and immovable mainland, on the other hand (Terebikhin, 2020, p. 109; author’s translation). The archetypal universe is structured in the form of concentric circles, as described by the most authoritative researchers of the mythological worldview. “At its most sacred point lies the miracle stone—the ‘center of the magical coordinates of the world,’ and the miracle island—the last circle before that point” (Denisova, 2009, p. 78; author’s translation)—its “sacred spatial and temporal center” (Toporov, 1993, p. 99; author’s translation). The archetypal island typically features an “green oak tree,” implying the interconnectedness of the island and the world tree—the axis connecting Heaven and Earth. The boundary between the sea and the land is perceived as a liminal space. Islands with such semantics in the Russian cultural landscape are predominantly found in the Russian North.

Certainly, Sakhalin was home to the Nivkhs and Ainu, for whom the island was the center of the world. However, in the figurative system of Russian geoculture, Sakhalin is an Island-on-the-Edge. Perhaps this is due to its relatively late exploration by Russian pioneers, in the post-mythological era. Consequently, Sakhalin lacks the strong mythological significance in Russian culture that the islands of the Russian North possess.

Unlike smaller islands that are geographically distant from the region’s main events and often hold sacred or holy status (Lavrenova, 2020), Sakhalin itself serves as a host landscape for indigenous peoples and for the settlers, who later became the main population.

Despite its geopolitical peripherality, unlike small islands perceived as fragile lands under the sway of water, Sakhalin is Insula Firma in an ontological sense, a self-sufficient entity, solid in many of its manifestations. It possesses ample land for agriculture and abundant mineral resources for industrial development. As a pinnacle of social self-sufficiency, the island boasts its own scientific school, with numerous research institutes operating here. Among them is the Institute of Marine Geology and Geophysics, belonging to the Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, which, incidentally, has its own YouTube channel.[3] Although not highly active, the channel effectively represents the institute’s activities and, more importantly, provides scientific insights into the unique natural landscape of Sakhalin.

However, despite the island’s size, a certain integration between the terrestrial/marine (and aerial) infrastructure and cultures, typically observed on most islands, the dichotomy of land and water still exists. This duality evokes constant contemplation, especially as the largest urban settlements are situated in the coastal zone. Consequently, the literary and visual reflections of Sakhalin are intertwined either with the sea or with the concept of detachment from the mainland.

Russian culture encompasses the concept of Northernness, which shares similarities with the concept of Far Easternness, as illustrated by the quote from Kropotkin above. Both concepts are united by the harshness of natural conditions, even though Sakhalin is located between the 46th and 54th parallels within the temperate monsoon climate zone. Thus, the concept of Far Easternness is supplemented by the imagery of climatic and natural wealth. No wonder that modern video clips about the island often include descriptive phrases such as “This land is harsh but beautiful.”

Temporal modalities in visual representations of Sakhalin are characterized by constant flashbacks. On the one hand, we can speak of “island time,” which differs from continent time due to Sakhalin’s distinct sequence of events and its own unique history, significantly diverging from that of the mainland Russia. The island is “separated” not only by a physical water barrier but also by its self-constructed cultural landscape that emerged during the epoch of resettlement from the mainland. On the other hand, the history of Sakhalin constitutes the history of Russia’s eastern borders, its integration into the country’s cultural landscape, including informational and visual elements.

This study uncovers a range of semantic aspects within the geocultural and corresponding visual representation of Sakhalin: the island as both a mythologized and tangible geographical location, geopolitical collisions within this region, the forced or incentivized movement of substantial groups of people, the impact of state interests on those of the island’s native or settled inhabitants, the exploitation of natural resources for mainland interests, and the ensuing socio-cultural challenges. Visual depictions form an integral part of representing these issues, influencing perceptions in alignment with the prevailing ideology of the time.

Therefore, it is logical to examine visual representations of Sakhalin from a historical perspective and utilize them as a foundation for constructing a comprehensive model of the island’s image.

3. Prison Island (1870–1917)

“There is water all around and trouble in the middle”—this saying became associated with Sakhalin in the second half of the 19th century. In 1853, the Russian flag was raised over Sakhalin for the first time, and in 1869, Tsar Alexander II approved the Committee’s Provision on the Introduction of Katorga Labor (a hard form of penal labor), which officially designated the island as a place of penal servitude and exile. One of the reasons for sending convicts to the island was to utilize their labor in local mines with the aim of developing Sakhalin. Numerous scientific works, including Sharyl Corrado’s dissertation (2010), have examined the history of Sakhalin’s convict labor. One of the most recent monographs on the subject is a book by Andrew Gentes (2021). These studies predominantly provide detailed analyses of the events and their representations from that period.

Sakhalin is shaping into a typical “landscape of fear” (as defined by Yi-Fu Tuan) associated with punishment:

Rulers, from fear that their world might shatter, use force to impose order. For force to be an effective deterrent, people in authority once believed that it must be both severe and visible. The result was the creation of a landscape of punishment… (Tuan, 2013, p. 175)

While Tuan, in his book, focuses on localized places of execution and prisons within the urban landscape, in the case of Sakhalin viewed from mainland Russia, the entire island with a total area of 76,600 km² becomes the “landscape of fear” and the symbol of the penitentiary system. This “landscape of fear” held nationwide significance. According to the memoirs of Polish exile and explorer Bronisław Piłsudski,

The mere mention of the word “Sakhalin” sent shivers of terror through all Russians; it was preferred to be spoken only in hushed tones. When I was sent to this accursed island by God as a political exile, I thought I had ended up in a place where there was no hope, no chance of escape. (Piłsudski, 2017, p. 3; author’s translation)

3.1. Anton Chekhov as a Genius of Place

The documentary and artistic exploration of this frontier began with the renowned Russian writer Anton Chekhov, who purposefully arrived here without official permission and stayed for 94 days, from July 11 to October 13, 1890. He first likened the outline of Sakhalin to that of a sterlet, an image that would later be frequently referenced. Drawing from his personal impressions, Chekhov created a remarkable text that highlighted the social issues of the island, a narrative that subsequent generations will continue to revisit and draw inspiration from. In this manner, Chekhov became a “genius of place,” laying the foundation for future literary and visual portrayals of Sakhalin. In addition to acquainting himself with the island and its inhabitants, he conducted a “population census,” filling out around 10,000 census cards—seven years before the first official census in the Russian Empire (1897). Chekhov succinctly and dispassionately described the unflattering reality and commissioned the taking of photographs, which he later used to illustrate his book. Most of these photos were captured by Innokenty Pavlovsky and portrayed everyday scenes of convicts, their work, shackling, and living conditions (Fig. 2).

It is important to note that Chekhov was not the first to photographically represent the island.

Photographs of Sakhalin generated a cultural myth about the development and adaptation to life on this inhospitable island, and the photographic documentation of Sakhalin was accompanied by a demand for it, both from a journalistic and literary standpoint. Photography during that period, among other things, provided an effective research resource for understanding frontier territories, allowing to record an objective and impartial view of reality, and conveying the flair of the era. Natural objects, cultural artifacts, and human images captured in photographs became key elements in constructing the territory’s image and visualizing it in the absence of written evidence. (Golovneva & Golovnev, 2020, p. 83; author’s translation)

Some photos were sold as postcards, such as those featuring the famous female thief Sonia “Golden Hand,” that became a talisman for swindlers. However, it was Chekhov who first published them in a book, Sakhalin Island (Chekhov, 1967), that became a revelation for Russian readers. After its publication in 1895, administrative inspections were conducted on the island, resulting in certain improvements. These included the abolition of corporal punishment for women, the allocation of public funds for orphanages, and the discontinuation of perpetual exile and life imprisonment.

The photographs of Sakhalin taken by Innokenty Pavlovsky are divided into views and genre categories, aligning with the compositional structure of Anton Chekhov’s book, Sakhalin Island. The initial chapters, up to Chapter 14, provide an overview of populated areas, while subsequent chapters delve into the “specifics, both significant and insignificant, that constitute the lives of convicts.” Notably, there exists a certain correlation between the photographic and literary depictions, with each photograph—with few exceptions—authentically illustrating Chekhov’s text. (Golovneva & Golovnev, 2020, p. 87; author’s translation)

Inspired by Chekhov’s book, the renowned journalist Vlas Doroshevich also journeyed to the penal island in 1897 after extensively studying the art of photography (Bukchin, 2010, pp. 159–162) (Fig. 3). The result was his book, Sakhalin (Doroshevich & Gentes, 2009). Initially published in 1903 by the Ivan Sytin Partnership, it underwent three reprints by the same printing house. In contrast to Chekhov’s book, Doroshevich’s work faced persecution from the authorities: it was removed from libraries, and its sale was prohibited at railroad stations and markets. This is not to say that it was significantly less candid than Chekhov’s text, but the writer attempted to disguise his work as a scientific study, whereas Doroshevich wrote as a journalist, without omitting intricate details.

Surviving photographs of Sakhalin from the late nineteenth century indicate that the visual representation of life on the “convict island” was constructed through the depiction of typical characters’ positions and genre scenes (everyday life and labor of convicts), physical anthropology (“foreign faces” and “criminal visages”), as well as the island’s architectural and natural landscapes, and was influenced by the mode of viewing a “picture” or photo album. (Golovneva & Golovnev 2020, p. 90; author’s translation)

3.2. Indigenous Peoples

In Sakhalin Island, Chekhov also touches on the subject of indigenous peoples, primarily describing their life and customs. Researchers and photographers were also intrigued by them. Sakhalin was originally inhabited by the Nivkh people (formerly known as Gilyaks), Nanai (formerly known as Gold), Evenks, and Uilta (or Oroks); there were also Ainu, who resided on the island until the mid-20th century. Photographers created portraits of these indigenous peoples for research purposes, capturing everyday life, customs, and clothing peculiarities. One of the researchers and photographers was Bronisław Piłsudski, who was initially exiled to Sakhalin due to his political activities against the autocracy. Among his notable achievements were the study of the Ainu language (Piłsudski, 1912), and a unique collection of photographs, which he used in his book, At the Bear Festival of the Sakhalin Ainu (Piłsudski, 1915) (Fig. 4). In 1896, the Sakhalin Regional Museum was established at the Alexandrovsk town military post.

Rather than downplaying or concealing the island’s penal function, the museum portrayed it as rational, productive and scientific. A photography studio was opened to create a collection of photographs, primarily of convicts, but also of other areas of the island, to enhance the museum’s collection. An added benefit in the project of Sakhalin representation was the collection of multiple samples of many of the items, providing objects to exhibit in Khabarovsk or other museums on the Russian mainland. (Corrado, 2010, p. 137)

Such materials became part of a rather extensive visual-anthropological text about the Far East, created by travelers and researchers (Golovnev & Golovneva, 2021).

Interestingly, a collection of photographs from the late 19th century is preserved in the New York Public Library, digitized and available on their website. Unfortunately, the photographer is unknown. The collection is described as follows:

Photos presumably taken around time of Chekhov’s visit and composition of his famous expose Journey to Sakhalin (189_). Remarkable materials from one of Russia’s most notorious penal colonies. Of exceptional interest, in spite of the fading of some of the prints. (The New York Public Library, n.d.)

4. Frontier Island (1917–1995)

4.1. Development of Sakhalin During the First Soviet Five-Year Periods

After the Russian Empire’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, the island was divided into North and South at the 50th parallel, and Japan acquired South Sakhalin, which was designated as Karafuto prefecture. This period introduced a new ethno-social problem for Sakhalin: the forced migration of Koreans to the island for labor purposes.

Only after the end of World War II was the island recaptured by the Soviet army and returned to the Soviet Union, the heir of tsarist Russia.

Soviet North Sakhalin of the 1930s was primarily documented through photographs. Unfortunately, the earliest films from that period are not available online, as they are stored in archives and are only described here based on researchers’ texts.

The portrayal of “territorial development” aligned with the idea of a “new way” is another recurring motif in films of that time. [All of them fit into] the overall ambition of the Cinema Atlas of the USSR state project—the cinematic mapping of territories and the visual expansion of Soviet influence, including the remote areas of the Far East. (…) It is worth noting that the state’s interest in producing and distributing such films had a utilitarian purpose: to inspire resettlement interest among the population and encourage colonization of the outskirts, as well as to attract the attention of Western commercial circles to the natural resources of the USSR. (…) The visual ethnography, prevalent in Soviet travel films of the 1920s–1930s, mirrored the national policy of “korenizatsiia”[4] in the USSR, which was also true for films about the Far East. (Golovnev, 2023, p. 100; author’s translation)

One of the earliest known Soviet films was Across Kamchatka and Sakhalin (Sovkino, 1929), directed by Leonid Vulfov and filmed by Mikhail Leontiev (Sarkisova, 2015), which explores the integration of traditional national communities into Soviet reality.

The silent film Chita—Sakhalin is a cinematic text (frames with intertitles) depicting a Komsomol boat trip from Transbaikalia to Sakhalin Island. It was created using footage shot by Alexey Kusheshvili, a former border guard who became a newsreel cameraman and joined the Far Eastern branch of Sovkino (Soviet Cinema state organization). Kusheshvili independently filmed various events in the Far East, and this material was later edited by director Nikolai Soloviev at the Sovkino central studio and released nationwide. Here is a part of the storyboard from the film, including the intertitles:

(Golovnev, 2023, p. 99; author’s translation)

- Scene:

- The journey along the Amur continues.

- Title:

- PARTICIPANTS OF THE DINGHY TRIP MEET THE SHIPS OF THE AMUR MILITARY FLOTILLA.

- Scene:

- The campaigners, accompanied by gunboats, pass by the Chinese border town of Sakhalian.

- Scene:

- Coastal views of Blagoveshchensk. Soviet border guards welcome the participants. The orchestra plays. More views of Blagoveshchensk.

- Scene:

- Dinghies depart from the Blagoveshchensk pier down the Amur.

- Scene:

- The trip continues in the Khingan Mountains.

- Title:

- ON GUARD OF THE SOVIET COASTS.

- Scene:

- Portraits of the participants in dinghies alternate with shots of warships from the Amur Flotilla.

- Title:

- DISCUSSION OF THE REPORT OF COMRADE STALIN AT THE XVI CONGRESS OF THE PARTY.

- Title:

- NOT ALWAYS ON THE OARS. (…)

- Scene:

- Participants of the dinghy trip depart from the shore.

- Title:

- HAVING DESCENDED INTO THE MOUTH OF THE AMUR AND PASSING THROUGH THE TURBULENT TATAR STRAIT, THE DINGHIES ARRIVED SAFELY ON SAKHALIN.

- Scene:

- The mouth of the Amur, the Tatar Strait, and the boats approaching the shores of Sakhalin.

- Title:

- THE CAMPAIGNERS, HAVING TRAVELED 4 ½ THOUSAND KILOMETERS.

- Scene:

- A group of participants in front of the camera.

- Title:

- WORKING YOUTH, LET US GIVE OUR STRENGTH AND AGILITY, GAINED FROM MILITARY PHYSICAL TRAINING, TO THE THIRD YEAR OF THE FIVE-YEAR PLAN!

Here is the description of the 10-minute film Sakhalin (1939, Far East Newsreel Studio), directed by Nikolai Lytkin.

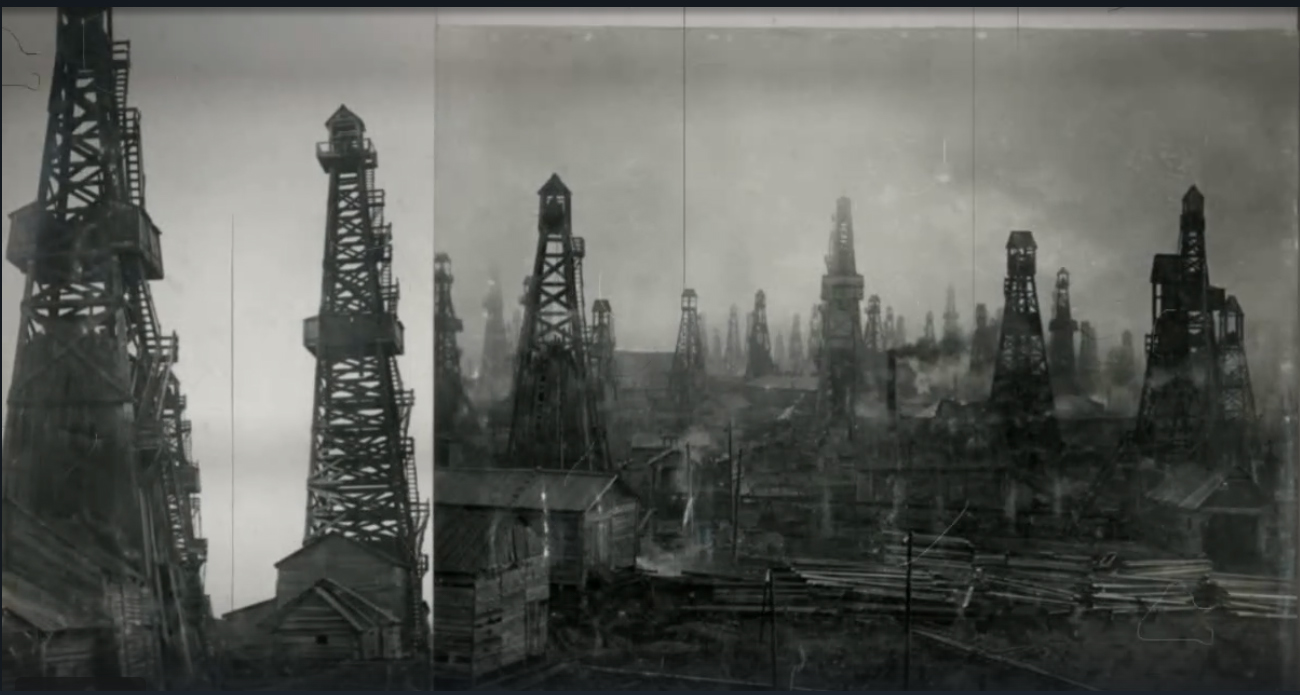

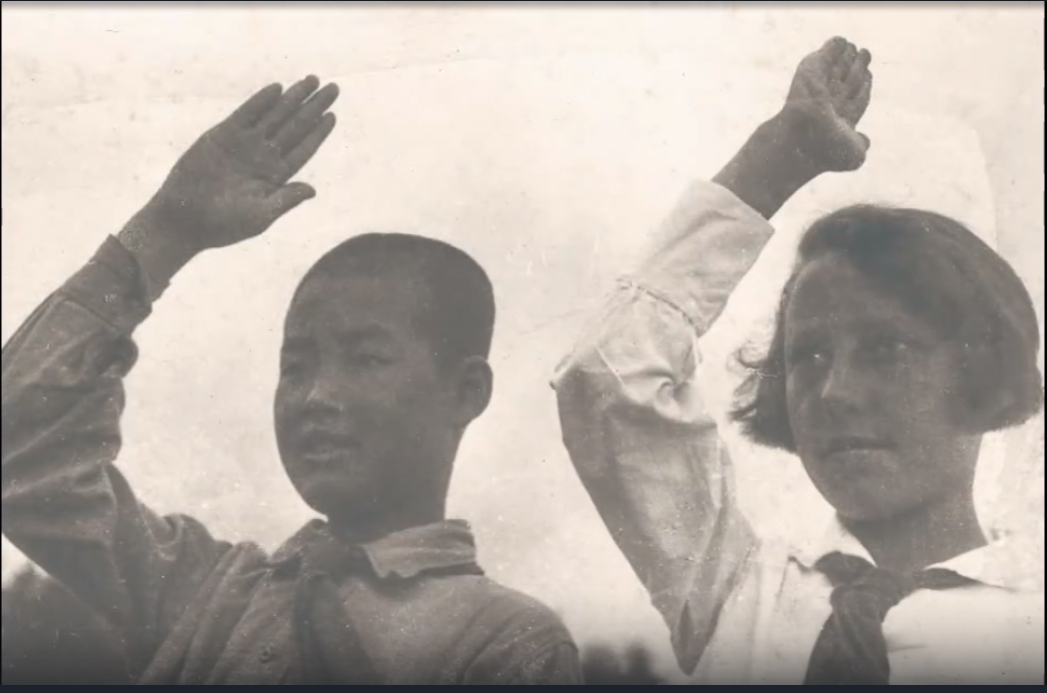

Sakhalin on the geographical map of the USSR. Views of the island’s coastline. A group of towering rock formations known as the Three Brothers in the central part of the island’s western coast in the Tatar Strait. Footage of the taiga. A view of the town of Alexandrovsk-Sakhalinsky. A hydroplane landing on the water’s surface. Passengers descending the stairs from the hydroplane. Bags of printed publications being unloaded from the hydroplane. GAZ automobiles on the town streets. Local residents in the park. The building of the Anton Chekhov Museum, where the writer lived during his visit to Sakhalin in 1890. Photographs of convicts. Pioneers listening to a biographical monologue by a former political prisoner. Pioneers with flowers and portraits of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin welcoming a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. A GAZ car driving through “penal sites” deep into the island, passing by the remains of prisons. Houses of kolkhoznik-resettlers from the central regions of the country. A kolkhoz [collective farm] wheat field, agricultural machinery, ripe wheat ears. Krasnaya Tym oil farm. A sovkhoz [state farm] herd of cows grazing in the pasture and near the farm. Calves in individual cages. Calf-women caring for their young animals. A milkmaid pouring milk from buckets into cans. Views of the Tym River. An ethnographic sketch about the Nivkhs: women hanging animal hides on a homemade dryer by the river, men fishing, Nivkh children having lunch at a table by the river in a kindergarten. Oil derricks of the Okha oil fields. Oilfield workers at work near a drilling rig. Specialists in the laboratory examining oil samples. An airplane with the inscription “Main Fishery” for aerial reconnaissance of fish shoals for Sakhalin fishermen standing by the shore. Fishing vessels at sea. Fishermen pulling nets with fish, unloading fish into the boat. Soldiers from the Sakhalin Border Detachment on patrol duty by the sea shore. (Golovnev, 2020, p. 113; author’s translation)

There were also photo albums. One of the videos on Rutube[5] (Fig. 5, 6) is dedicated to a unique 1937–1938 photo album produced in a limited edition of approximately 10 copies as a gift to the heads of Okha, Nogliki, Tymovskoye, and Alexandrovsk-Sakhalinsk districts. The album includes photographs depicting the development of industry, agriculture, culture, and the lives of indigenous peoples on Sakhalin in the first half of the 1930s.

4.2. The National Question on Post-War Sakhalin

For obvious reasons, the comprehensive visual portrayal of the island began only after World War II. Still, despite the strategic and ideological significance of the island, it did not have its own film studio, unlike other administrative entities. In the Soviet post-war period, there were both highly professional documentaries and feature films about Sakhalin. Some films incorporated the island as part of the plot or were filmed on its territory. The first films shot after 1945 were framed within an ideological context, focusing on the development of new territories, natural resources, and border conflicts. The theme of South Sakhalin “liberated from Japanese oppression” was also emphasized.

Across Sakhalin (1947), a documentary directed by Alexander and Evgeny Alexeevs, provides a comprehensive overview of the region.

It is a sound film, and the voice-over narration provides valuable information alongside the visuals. (…) The narrative takes the audience on a journey through the history of Russian exploration of Sakhalin: Vasily Poyarkov’s campaign in 1643, Nevelsky’s maritime expedition in 1849—which then transitions into a natural-geographical overview and an ethnographic section with a chapter dedicated to the Ainu people. (Golovnev, 2020, p. 28; author’s translation)

The film then says that the Japanese arriving on the island turned the Ainu into slaves.

(Golovnev, 2020, p. 29; author’s translation)

- Announcer:

- “The sacred shavings that guarded the dwellings of the Ainu did not bring them deliverance from slavery. But the Ainu told their children about happiness.”

- Scene:

- Smiling Ainu children.

- Announcer:

- “They knew that in the North of Sakhalin, Russian people have realized the age-old dream of oppressed peoples.”

- Scene:

- The border post separating the territories of Northern (Soviet) and Southern (Japanese) Sakhalin.

- Announcer:

- “On the other side of the boundary post, a new life begins.”

The film ends with a narrative about the Soviet innovations on Sakhalin, highlighting the implementation of the current five-year plan and the establishment of a fishing collective farm. Here, Russian fishermen work alongside Nivkh fishermen.

It should be noted, however, that the Ainu did not reside on Soviet Sakhalin for long. During the repatriation campaign of 1946–1949, they left the island and relocated to Hokkaido alongside the Japanese. Although they were not originally Japanese citizens subject to repatriation, many of the Ainu had been heavily influenced by Japanese culture and propaganda.

Upon their arrival on the islands, the Soviet authorities aimed to transform the social, political, and economic system. However, they faced significant challenges such as a labor shortage for the region’s industry and limited available resources. Initially, the authorities envisioned the swift integration of the Ainu into Soviet society but realized that accomplishing this goal would require substantial resources. Since there were no apparent economic benefits from employing the Ainu in the island’s industry, the Soviet authorities did not prevent them from leaving South Sakhalin. (Din, 2021, p. 94; author’s translation)

Thirty years later, according to the 1979 census, only three people on Sakhalin identified themselves as Ainu. Meanwhile, Koreans were not allowed to leave the island and remained stateless until they were granted citizenship in 1952 (Din, 2014).

4.3. “Our Island!”

The euphoria after the island’s unification under the USSR’s jurisdiction represents a new thematic trend in the visual representations of the postwar era. The 1948 film On the Native Land! (South Sakhalin)[6] (Fig. 7) by the Khabarovsk Newsreel Studio stands as the first comprehensive film to provide a multifaceted overview of recent history and emerging economic trends. The film opens with footage of an airplane carrying voluntary settlers to the island, and a bird’s-eye view of the shore. The voice-over announcer declares, “From all over the country, the Soviet people are coming to Sakhalin. Here it is, this land, distant yet so close, sanctified by the labor and achievements of the Russian people!” The film delves into the history and geopolitical context, highlighting Japan’s blockade of Russian and Soviet ships from Vladivostok to the Pacific Ocean, establishing a “bridgehead for attacking the USSR in the Far East.” Then comes documentary footage of the end of World War II, showing the Soviet offensive in the Far East and the surrender of the Japanese army. The announcer exclaims, “The way to the ocean is open!”

The film showcases the construction of new settlements, the railroad, and celebrates the natural wealth and beauty of the landscape, including rookeries of birds and seals, nurseries of silver-black foxes and American mink. We see the daily lives of sea workers: fishermen, crab catchers, and seaweed miners. The film contrasts the predatory exploitation of nature by the Japanese with the thrifty Soviet economy. It proudly presents the processing of wood into paper at the Poronaysk paper mill (now abandoned) and demonstrates coal mining, emphasizing that miners came here from all over the USSR, reporting their labor successes to Stalin—the first Stalinist five-year plan is implemented on Sakhalin. The Soviet science is not left behind, too: the film highlights exploration of new oil deposits and experimental plots for grain and vegetable cultivation. Young people, coming from the central regions of the country to become collective farmers, harvest their first crops and celebrate housewarming as they move into new homes. The announcer states that the settlers are exempt from all state monetary taxes. The film further depicts a group of new settlers—young teachers from the North Caucasus who came on a “Komsomol ticket”—through Party and Komsomol organizations—to contribute to promising areas of socialist construction. The film concludes with shots of ocean waves and a warship on the horizon, symbolizing the defense of the new Soviet land against the forces of imperialism.

Another significant documentary film in Soviet cinema was Sakhalin Island (1954)[7] by Vasily Katanyan and later renowned director Eldar Ryazanov, marking his creative debut. The film received awards at the Cannes Film Festival (1955), and Ryazanov was subsequently invited to Mosfilm. Sakhalin Island showcases the heroism of Soviet geologists and their exploration of the wild land. It also pays attention to local reindeer herders and highlights the uniqueness of nature, including rookeries of birds and seals. The film features scenes from the Alma-Ata floating crab factory. Along with field shooting, the authors employed the method of “reconstructing the fact” to recount the story of the Pozharsky fishing vessel trapped in the ice. In order to find an ice floe, one of the operators ventured to the Sea of Okhotsk, while two airplanes captured footage of the staged accident: one filmed the overall view, and the other dropped bags with food and “explosives.” This episode exemplifies the mutual support often depicted in Soviet cinematography (Fig. 8). To justify the footage shot on the ship, the film directors portrayed the cameraman as the first person to descend onto the ice floe. However, in reality, we see a mannequin dressed in a half-coat and parachuted down instead (Ryazanov, 1983, pp. 27–28).

Due to the geopolitical rivalry between the USSR and Japan over the territorial belonging of South Sakhalin, the inclusion of ethnographic scenes [in the film] carries political weight, serving as an argument for the formula “our natives, our territories.”

As for the image of a “radiant future,” it was meticulously created through scenes depicting the construction of new cities and towns, the development of mineral resources, and the integration of indigenous peoples and local settlers into their new lives. (Golovnev, 2020, p. 114; author’s translation)

Despite its documentary genre, the film was quite innovative due to its avoidance of the ideological slogans typically found in documentaries of the 1930s and 1940s. It was ultimately saved by documentary filmmaker Leonid Cristi: he personally delivered the reels to the USSR Minister of Culture (Katanyan, 2002, p. 333), who granted Sakhalin Island the green light.

4.4. Anton Chekhov as a Genius of Place: A Flashback

The third episode of Olga Koznova’s documentary series Journey to Chekhov (4 episodes, 1982–1983), Sakhalin Lighthouse[8], created a captivating visual representation of Sakhalin, evoking a sense of a time loop. In this episode, writer Vladimir Lakshin and actor Yury Yakovlev, the cream of the Soviet intelligentsia, engage in a relaxed conversation about the life and work of Anton Chekhov (Fig. 9). The narrative intertwines the story of the great Russian writer’s stay on the prison island with excerpts from his book and contemplations on his personality. In preparation for the journey to Sakhalin, the director immersed himself in all available books on the topic, which, incidentally, painted a vivid picture of Sakhalin as a blossoming land. As the actors walk through the “places of memory” on Sakhalin, they point out that what is now an asphalted ground used to be called Kandalnaya Square (Russian: “kandaly” [кандалы]—shackles), where Chekhov’s time witnessed a stockade—a large courtyard enclosed by six wooden barracks. The visual sequence incorporates archival photos from Chekhov’s collection and the exhibits from his Museum in Alexandrovsk-Sakhalinsky. Notably, the narration unfolds against the backdrop of Soviet Sakhalin, where stone buildings stand tall, and the famous “loaf” UAZ buses traverse the asphalted roads (Fig. 10). The landscape views are accompanied by voice-over quotes from Chekhov, emphasizing the pervasiveness of prejudice in nature and evoking a sense of pity and compassion even for the plants growing here, on this isle of exile. A particularly interesting interview features a woman who is the great-granddaughter of convicts. She recounts how her great-grandmother, along with other female convicts, stood in a row while male convicts were brought forward, and they were all married simultaneously. The episode delves into Chekhov’s subsequent creative path, highlighting how his experience on Sakhalin profoundly influenced his perception of life and his work. The lines from his book, expressing the deep-rooted fear of the Russian people when facing a blind and ruthless judicial system, where one can be sentenced for no reason at all, resonate powerfully in the present. The final shot captures the Sakhalin lighthouse, which Chekhov himself mentioned—a symbolic representation of the penal colony observing the world with its piercing red eye.

Another landmark documentary, Across Sakhalin[9] (1984), is part of the mega-popular Soviet TV show Travelers’ Club hosted by journalist and traveler Yuri Senkevich. The film begins with the depiction of a ferry crossing, connecting the island to the mainland. It explores various themes such as the discovery and development of the island, the period of penal labor, the influence of Chekhov’s book, and the lives of indigenous peoples (we see archival photos, everyday objects of the Nivkh and Ainu people, and archaeological finds from the Paleolithic era displayed at the Museum of Local Lore). The documentary also features footage of a Nivkh holiday, new comfortable houses for the Nivkhs, and scenes from a boarding school where Nivkh children study. A local gamekeeper talks about what and how locals cultivate on the island, and mentions that bears sometimes come into the yards.

4.5. Narrative Films

In the 1960s, the first Sakhalin’s own film studios were established.

The State Historical Archive of the Sakhalin Region is one of the few in the Far East that preserves film documents. To date, the archive holds more than 8,100 storage units. The primary source of film materials for 26 years was the Sakhalin Television Studio, whose initial works were received by the State Archive of the Sakhalin Region (GASO) in 1965. (…) During that time, regional television studios would typically submit their productions to the branch of the Central State Archive of Film, Photo, and Phono Documents (TsGAKFFD) of the RSFSR in the city of Vladimir (since 1992, RGAKFD—Russian State Film and Photo Archive, located in Krasnogorsk, Moscow Region). However, as an exception, the Sakhalin studio was allowed to store film documents locally, considering not only the region’s remoteness but also the high level of expertise among the regional archive specialists. (Ministry of Culture, 2016; author’s translation)

There were also amateur film studios, such as the Sakhalin Trade Union Film Studio (Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk), Film Studio of the Seafarers’ Palace of Culture (Kholmsk), Volna Amateur Film Studio (Nevelsk), Tym People’s Film and Photo Club, Kunashir Film and Photo Club, and the Amateur Studio of the Logging Company (Pervomaisk), etc. The best works of amateur cinematographers were showcased on Sakhalin television and later added to the film collection of GASO (Ministry of Culture, 2016).

Soviet feature films set on Sakhalin are relatively few and span various genres, with most being produced in the 1980s and 1990s. Some films do not primarily focus on Sakhalin but use the island’s remote locations to depict places at the edge of the Earth. Examples include the feature films White Dew (1983) and Thy Will be Done, Lord (1991), which explore themes of life and love.

A notable mention among the late Soviet period feature films is Karen Gevorkian’s ethnographic and philosophical film based on the novel by the iconic Soviet writer Chingiz Aitmatov, Spotted Dog Running at the Edge of the Sea (Fig. 11). The film pays homage to the Nivkh people. Initially, the shooting was halted by Soviet censorship due to its deviation from Soviet ideologized films. However, with the beginning of Perestroika in 1986, the director was given the opportunity to complete the project, and filming concluded in 1991. The film consists of two parts. The first part is documentary episodes capturing Nivkh life: cramped houses, bear hunting, bear ceremonies, dances, and incantations. The second part follows the plot of Aitmatov’s story. A ten-year-old boy goes fishing and seal hunting for the first time with his father, uncle, and grandfather. Trapped in a storm and shrouded in fog, they lose sight of the shore, leaving them unable to return home to their sopka, a knoll resembling a shaggy dog with white spots on its ear and groin. As food and water run out, the men decide to sacrifice their own lives for the survival of the child and the continuation of their lineage. The boy eventually returns to the shore alone.

4.6. Sakhalin Koreans: A Formerly Taboo Subject

In Russian documentaries from earlier years, the Korean question was addressed solely in a positive light, portraying it as a newfound haven for relocated individuals. It was not until the era of Perestroika and the onset of glasnost that the first critical films on this subject emerged. Interestingly, nearly at the same time with Revenge, another foreign documentary was made about Koreans on Sakhalin. Forgotten People: The Sakhalin Koreans (1995), directed by Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, turned out to be very elegiac, too.

The opening sequence pans slowly over the attractive forested hillsides of Sakhalin, but the beauty of the land belies the horror of the stories recounted. As a plaintive soundtrack of classical Korean music sets a melancholy mood, we encounter a litany of harrowing tales: interviewees describe how they were snatched from their families as young men and sent to a distant land to further the imperial Japanese war effort. Their accounts tell of frequent beatings and appalling living conditions, marked by a meager diet, inadequate shelter, and intense cold; former mine laborers detail the dangers of their work and the attendant possibilities of disease, disfigurement, and death. The film captures the recurrent use of animal similes in the interviewees’ self-presentation… In one of the few interviews that tackles these issues head on, a thoughtful young tae kwon do instructor, flanked by two Russian friends, notes that “we consider Russia to be our motherland. Our parents want us to go [to Korea], but we don’t.” (Epstein, 1998)

It should be noted that during the Soviet era, Sakhalin Koreans were predominantly assimilated, and when the opportunity to relocate to South Korea arose after perestroika, only a few took it.

4.7. Perestroika: Documentaries and Feature Films

The era of Perestroika ushered in new themes in Soviet documentary cinema, with films about Sakhalin reflecting this shift—an intense exploration of prevailing issues and future outlooks. An example of a topical perestroika documentary is the 2-part The Free Island of Sakhalin (directed by Alexander Krivoruchko, 1990, Part 1[10], Part 2[11]). It is a collection of disparate short stories, ranging from acute social issues to elegiac portrayals, unified solely by the location and the period (Fig. 12). During perestroika, the island was declared a free economic zone. The movie includes an interview with Boris Yeltsin, Russia’s first president, discussing the concept of the free zone. The innovation, however, brought not only freedom of enterprise, but also a consumerist attitude to nature. Among other things, the film delves into environmental problems, fires, predatory fishing, oil production, decaying military equipment, the challenging living and working conditions of the people, the labor camps that once existed on the island, and renowned travelers. While environmental concerns occasionally surface in the visual narratives of Sakhalin during the Perestroika era (a subject previously considered taboo), they do not serve as a key element in the island’s contemporary image. The theme of prisons and penal servitude resurfaces, bridging Chekhov’s memoirs with the twentieth century, shedding light on the role of Sakhalin within Stalin’s Gulag system. The film mentions the unrealized project to construct a railroad connecting the island with the mainland, which was supposed to be built by prisoners. Certain topics seem to unfold independently, such as meetings with relatives of Sakhalin Koreans and the story of Georgian artist Givi Mantkava, who has been living and creating on the island since 1956. The film also presents opinions from Boris Yeltsin (Fig. 13) and experts regarding the Kuril Islands claimed by Japan, thus reintroducing the theme of the border island, Russia’s frontier in the Pacific Ocean.

During this period, action films and historical tragedies—genres previously labeled as “bourgeois”—found their place among feature films. The 1989 Revenge (Shaken Aimanov Kazakhfilm studio), written by Anatoli Kim and directed by Ermek Shinarbaev, is based on Kim’s Sakhalin stories. This historical drama, belonging to the poetic genre, delves into Korean issues spanning from the Middle Ages to the present. Sakhalin serves as one of the settings in this tale of revenge and hope, where the protagonist, who migrated from Korea, finds solace and builds a house on the shore.

This image of the house was envisioned and materialized as a ship-house. We see the skeletal frame of a house being built on the very shore. The wall supports, rafters, and window openings serve as mere components of the structure, devoid of the burden of substantial construction. This dream house is oriented towards the water, akin to a buoyant vessel, sailing towards the sun. (Yeliseyeva, 2011, p. 42; author’s translation)

The plot of a 1991 action film titled Loaded with Death (directed by Vladimir Plotnikov) revolves around the joint efforts of Russian and American border guards combating a gang of drug traffickers. It signified the shift from confrontation to cooperation between the USSR and the U.S. The movie begins with a scene depicting the escape of a group of prisoners from a maximum security prison. Intelligence identifies a notorious foreign smuggler in the Far East… Through a meticulously planned operation, all the “bad guys” are neutralized. Filming took place in the cities of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk and Korsakov, with maritime scenes shot in Aniva Bay. However, it is worth noting that the geographical reference in the story is imprecise, as according to the script, action takes place somewhere in the Far East. The island of Shikotan, which is not far from Sakhalin, became the filming location for yet another Soviet film about defending the country’s border, The Right to Shoot (1981).

Across Soviet films, spanning from the Revolution to Perestroika, the enduring concept of the earth’s edge, correlated with Far Easternness, is reimagined in a fresh context. In Russian culture, the border with untamed wilderness is not merely a frontier (as in the American context) but a way of life for all territories east of the Ural Mountains. A novel portrayal in films from the 1940s to the 1980s is the domestication and integration of Russia's edge, bringing it closer to the mainland—a transformation credited to Soviet internal and external policies, including the victory over Japan. By the 1990s, during the era of Perestroika, the island’s peripherality began to be viewed as a nexus of social issues accumulated over preceding decades.

5. A Unique Island (1995–2024)

5.1. The Decline of Narrative Film and the Ascendancy of Documentary

In the post-perestroika era, the focus of feature films, including those centered on Sakhalin, shifted towards action. One such example is the crime series Hokkaido Police: Russian Department (2001–2007) based on the novels of Russian author Eduard Vlasov, also known as Kunio Kaminashi (or Kaminasi), who resides in Japan for many years. The plot revolves around Sakhalin and Japanese law enforcement officers combating Japanese and Sakhalin-based mafia.

However, this is so far the end of the history of feature films created on the island. On the other hand, the era of documentary films about Sakhalin is experiencing a resurgence, as this land holds special significance in the country’s strategic plans. Numerous professional films have been produced, capturing the island’s natural wealth and the lives of its inhabitants at the edge of the world. Listing them all would be impossible, but it is worth mentioning a few.

A notable phenomenon in Russian professional documentaries of the 2010s is the corporate film Sakhalin Island[12] (directed by Saida Medvedeva, 2009, commissioned by Sakhalin Energy Investment Company Ltd.[13]), which integrates advertising for the company. The film employs poetic documentary techniques, including costumed feature footages, and commences with the Ainu legend about the genesis of Sakhalin as “the land that looks like waves.” It provides a captivating account of the region’s geology, featuring interviews with Russian and foreign scientists. Footage of the devastation after the earthquakes of 1971, 1995, and 2006 is shown, accompanied by explanations of the ongoing tectonic evolution of the island. The legend about the origin of oil is illustrated through feature footage, followed by comments from scientists and shots of offshore hydrocarbon production platforms. The film also addresses the issue of constructing an oil pipeline that poses a threat to the island’s fragile ecosystem, with discussions involving Sakhalin Energy officials. Furthermore, the documentary explores recent archaeological discoveries—traces of Paleolithic and Upper Neolithic sites, which are believed to have been inhabited by the ancestors of the modern Nivkhs (Fig. 14) — and the spiritual culture of the Ainu. Interviews with representatives of indigenous peoples and footage depicting their daily lives are also included. In the concluding segment, the film optimistically asserts that Sakhalin has successfully implemented a harmonious system of interaction between industrial developments in oil and gas production and transportation, effectively managed by Sakhalin Energy, without compromising the delicate ecology.

5.2. World War II Revisited: A Flashback

This theme has been repeatedly explored in new documentaries of the 21st century. It should be noted that, for the Russian mentality, the victory over Nazi Germany remains the main historical event of national pride and a crucial cultural landmark in the Russian cultural code.

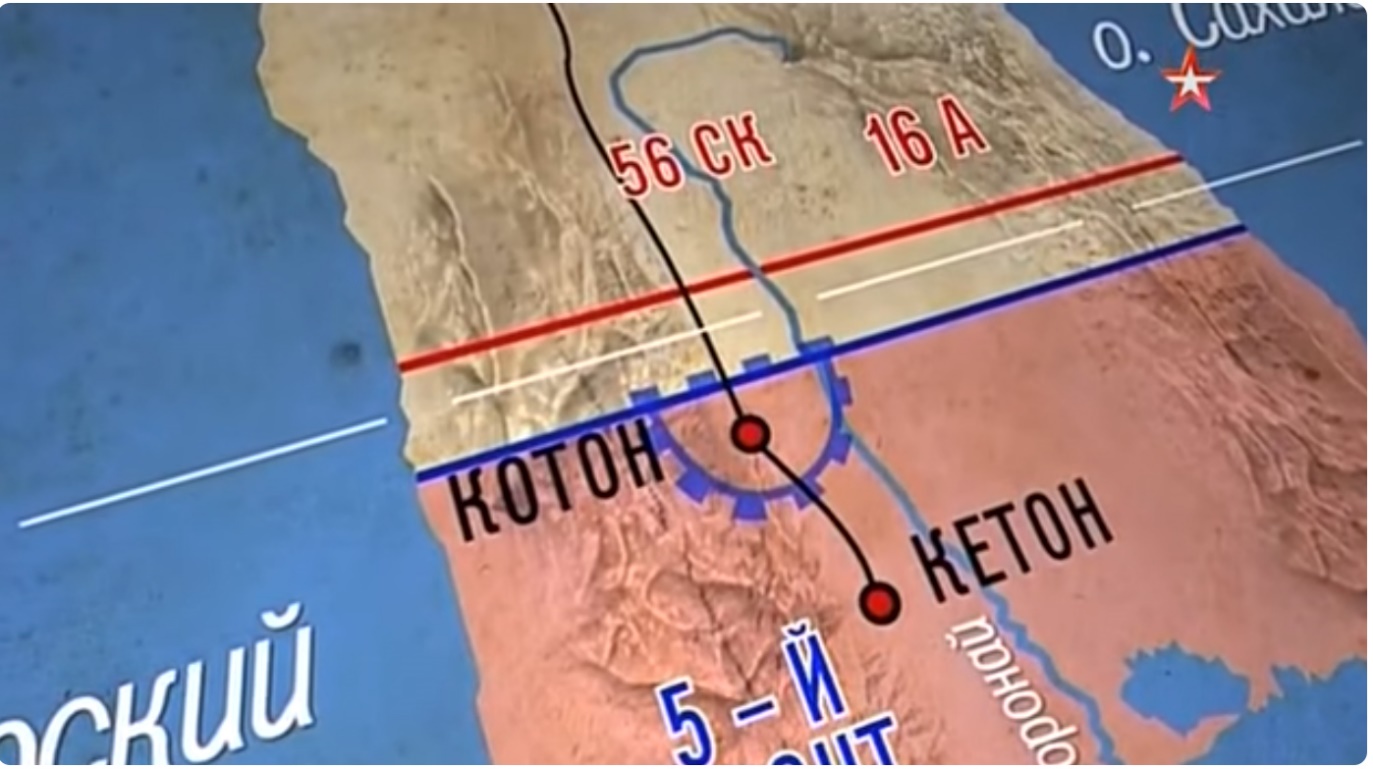

The second episode of the four-part documentary The War After Victory (TV Center channel, 2015) (Fig. 15), released to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Victory, is titled The Battle for Sakhalin.[14] It recounts the war with the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria, and Japanese troops in South Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, with a focus on the signing of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender. The film includes recollections from participants of the operation and showcases documentary footages of World War II battles, although many of them, such as shots of tanks or firing guns, lack a clear visual connection to Sakhalin. There are also feature footages portraying key Soviet army commanders in the region.

Another recently released historical documentary, The Mystery of Cape Anastasia (directed by Alexander Zarchikov, 2023), revolves around the search for a sunken Japanese escort ship in the La Pérouse Strait and the exploration of naval battles off the coast of Sakhalin (only the trailer[15] is available on YouTube). The film is divided into two parts: Devil’s Calls and The Past is Much Closer Than It Seems, and delves into the events of World War II in the Far East, as well as their lasting impact on the island’s cultural landscape. The project involved Sakhalin historians, local researchers, search teams, archaeologists, divers, and sailors, who organized an expedition to locate the remains of the ship. The narrative is enriched with archival footage, animation, and the filmmaker’s narration.

5.3. Lands of Promise and Neglect

During the Russia exhibition-forum held at the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy (VDNKh), the results of The Far East—the Land of Adventures travel contest were announced. The contest received 201 films, 55 of them were from Sakhalin. The short list included six finalists representing the island region. One of the films, Unlimited Possibilities (directed by Evgeny Ivanov, 2023), a short 5-minute film dedicated to Sakhalin, received an award. The film showcases footage of a six-day hike undertaken by former residents of Moscow children’s homes for children with disabilities, who now reside in the Center for Accompanied Living.[16] In this case, the breathtaking views and natural scenery of Sakhalin serve as a backdrop for the remarkable achievements of four young men with cognitive disabilities and their caregivers, who accomplished a challenging route, proving that there are no limitations to their capabilities.

In the early 2000s, a new documentary genre emerged: “people’s videos” and travel blogs. These films lack a strict narrative structure and instead focus on describing the author’s personal experiences and encounters with the geographical and cultural realities of different places. Such video blogs cover both foreign travels and journeys within Russia. Sakhalin occupies a prominent place among these videos, as talented travel enthusiasts who possess camera skills and video editing abilities often visit the island. A search query “travel to Sakhalin” on YouTube yields over two dozen recent full-length vlogs. For instance, Yulia Korneva’s Expeditions channel features a video called Tears of Karafuto. On Sakhalin, 115 Villages are Slated for Liquidation. A “Hermits of Russia” Series Film.[17] In it, Yulia shares her journey through Sakhalin, highlighting the local nature, history, and the prospects of development, as well as the government programs aimed at resettling villagers from rural areas to cities. The film also includes interviews with modern-day “hermits” residing in nearly deserted villages. “Tears of Karafuto” refers to the Japanese artifacts that locals discover at the sites of settlements destroyed after World War II.

The Sakhalin Region is home to more than 100 ghost towns (Danilenko & Povolkovich, 2015) and abandoned industrial sites, attracting modern travel bloggers whose content focuses on “derelict places” and “urban exploration,” as well as illegal treasure hunters. This is particularly prevalent in South Sakhalin, where the Japanese, fleeing in 1945, buried their valuables that they could not take with them. Valuable finds are typically not showcased on YouTube, but the videos do feature various fragments of pottery, bottles, and boxes that are discovered in such locations. An example is the video titled Found a Cache of a Japanese. Karafuto, Sakhalin (Fig. 16).[18]

5.4. Flashbacks...

Themes characteristic of Sakhalin’s last century image occasionally resurface in new formats. For instance, a modern visual format known as “folk visual art” takes the shape of a virtual tour consisting of quotations and photographs and based on the book Sakhalin: Katorga by Vlas Doroshevich.[19]

The issues of late 19th-century convict labor and Stalin’s Gulag on Sakhalin, as well as the challenges faced by the Japanese and Koreans in Soviet Sakhalin, are explored on a new informational level in a popular science lecture by historian Vladimir Staf, along with Reserve project participants, Ekaterina Kozhevina and Maria Perminova. The lecture, organized by the Gulag Museum[20] in 2022, delves into a railroad tunnel project that was intended to connect the island to the mainland but was discontinued after Stalin’s death. Its recorded version, accompanied by photographs, is available on YouTube[21] and the museum’s website.

There are more and more short films of an ethnographic and informational nature. Exemplary here is Oroks: Indigenous People of Sakhalin. Life. History | Facts[22] on Yamal Media YouTube channel, which collected black-and-white ethnographic videos from the early twentieth century, archive photos enhanced with modern technologies, and footage from contemporary exhibitions and folk art festivals. Among other facts, the video tells about a reindeer herding collective farm established in Northern Sakhalin during the 1930s, which later disbanded after perestroika, returning reindeer to the ownership of individual households. The film also mentions the scarcity of modern Oroks and the limited use of their native language in everyday life.

5.5. Community Videos: A Medley of Everyday Life

Since the 2010s, the creation of personal YouTube channels has become a widespread phenomenon, with Sakhalin residents being no exception. These channels have multiplied rapidly. Here are a few examples.

Mikhalych From Sakhalin[23] has 6.7 thousand subscribers and a slogan, “Living in the best place on Earth in the village of Bereznyaki.” The author shares videos on various events from his daily life, such as fishing trips, hill hikes, reports on store prices, updates on public utilities and road conditions, and even nostalgic videos capturing moments of summer and family. The most popular video (with over 1 million views) is titled Emergency on Sakhalin: Couldn’t Reach the Store (Fig. 17).[24] It was filmed after an extraordinary snowfall on Sakhalin in January 2024 and is set to the song Snow is Spinning, released in 1981 and considered a timeless classic akin to the French song Tombe la neige. With the lines, “Snow swirls, flies, and flutters, / Winter sweeps away all that was before you,” the author sets out from his snow-covered house, using two cardboard pieces as makeshift transportation, attempting to reach the store. However, unable to make it, he turns back, playfully diving into the snow and sinking to his shoulders. With great effort, he manages to dig himself out and resurface.

In another Mikhalych’s video clip, Talents of Sakhalin. Meet! Vladimir An!,[25] the title character proudly asserts his authenticity as a Sakhalin Korean while accompanying himself with a guitar song he wrote.

A Different Sakhalin channel[26] features another popular YouTube video (over 200 thousand views)—a lion in the Sakhalin Zoo after a snowfall.[27] The channel positions itself as a source of “news, incidents, and clips from local people,” that is, the author(s) collect and share videos sent by residents. A significant amount of content focuses on criminal incidents (or rather, local mischiefs), accidents recorded on dashcams, landfill sites, traffic jams during snowfall, fishing, and even snow tunnels dug by locals between houses.

Another emerging trend involves films about Sakhalin and the coastal regions of the Far East focusing on seafood collection and subsequent preparation. Channels like Boris Ryabchenkov[28] specialize in videos about fishing and shore gathering, like, for instance, Walking After the Storm: Not Much, but Enough for Lunch[29] (nearly 1 million views). Another example is Collecting Seafood on Sakhalin Island—We Arrived at Low Tide[30] (368 thousand views) by Sakhalin Family Novikovs[31] channel, and others. These videos evoke nostalgic sentiments of foraging, resonating with our modern consciousness, while being transformed into a gastronomic show, which are always popular (Fig. 18).

Investigative films represent a unique genre of “folk art.” For instance, Secret Chronicles channel presents an intriguing format of “historical investigation” in their piece titled How the Whole Soviet City Was Washed Away | The Classified Apocalypse of 1952[32] (2021). This story is about the North Kuril tsunami of 1952, which resulted in the devastating destruction of several settlements in the Sakhalin and Kamchatka regions, with Severo-Kurilsk suffering the greatest loss of life and damage. Although the video lacks documentary footage of the event—which is, naturally, nonexistent and impossible—it takes the form of a podcast accompanied by visuals that complement the narrative.

Another noteworthy trend is Telegram channels of Sakhalin residents, where events and nature are documented through filming. One such channel, SakhFly[33] by Eduard Abramov, focuses on capturing Sakhalin from a quadcopter’s perspective, producing visually stunning clips that no longer require the use of specialized equipment and helicopters as in the past.

There is an interesting project visualizing a famous Soviet song, “Well, what can I tell you about Sakhalin, the weather is great on the island.” This song, performed by the islanders against various landscapes, creates a positive and joyful impression,[34] serving as an unobtrusive advertisement for Sakhalin as a tourist destination.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Periodization and Classification of Visual Narratives

As we can see, the visual representation of Sakhalin in Russian culture can be categorized into three “ages.” Initially, through the efforts of remarkable individuals and the progressive intelligentsia of the late 19th century, the island, once an unexplored promised land, gradually acquired specific characteristics—unfortunately, mostly unattractive ones. Later, during the Soviet era, images of Sakhalin were centrally constructed to reinforce both literal and figurative ideological boundaries. Lastly, these images, especially in recent times, have become part of the phenomenon known as regional cinema. “‘Specific regional theme’ implies that the film’s subject matter should be intertwined with the expression of regional identity. (…) The discussion of regional cinema unveils the unexplored reality and creative potential of the regions” (Kravchenko, 2022, p. 147; author’s translation). Sakhalin’s regional identity is particularly evident in the “people’s videos” and YouTube channels created by local residents. Some key themes persist throughout a century and a half, namely pre-revolutionary penal servitude and ethnographic portrayals of local indigenous peoples. The depiction of Sakhalin has evolved consistently from a “landscape of fear” to a landscape of abundance, with flashback films occasionally resurfacing even amidst the dominance of prosperity, rekindling memories of the region’s stigmas.

6.2. A Model of Imagery Geography

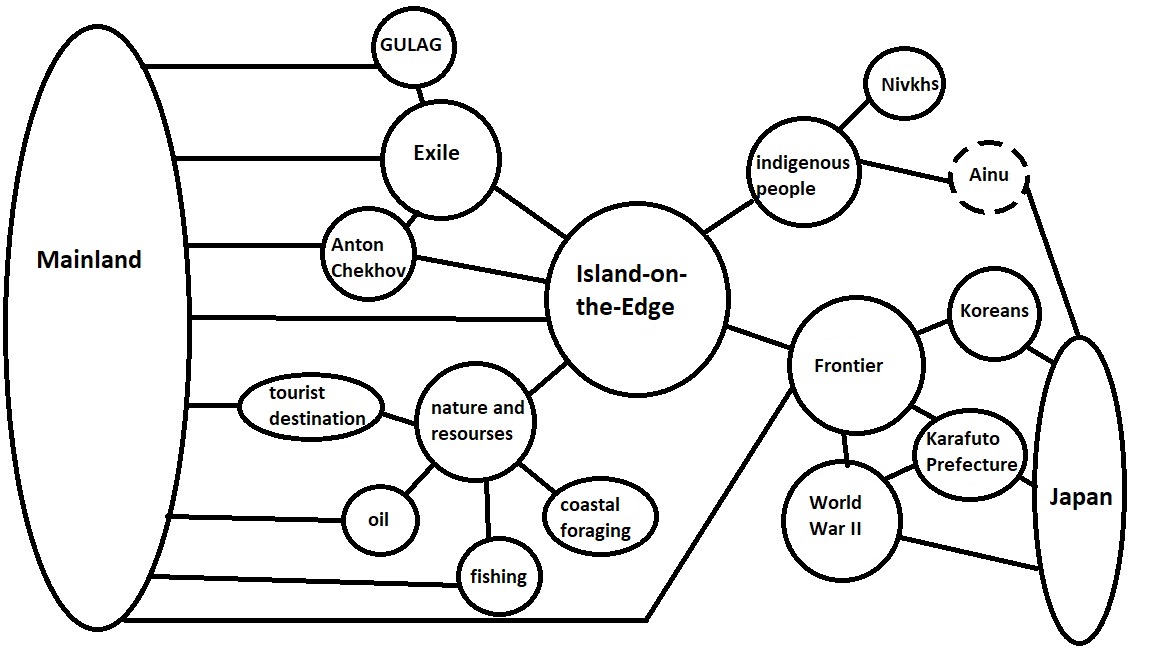

However, the main point of interest lies in the model of a comprehensive geographical image that can be constructed based on the visual images considered above (Fig. 19). This model showcases the meanings that the image of Sakhalin brings to the cultural landscape of Russia.

This model is based on the methodology developed by Russian geographer and cultural critic Dmitry Zamyatin for analyzing cultural landscapes and geographic images (Zamyatin, 2006). Interestingly, the complex image of Sakhalin, derived from analyzing audio-visual materials, encompasses geocultural, geo-historical, geopolitical, geo-social, and geo-economic components.

Sakhalin proper inevitably appears in the semantic paradigm of Island-on-the-Edge, which carries various meanings such as remoteness, detachment, frontier, outpost, and natural wealth.

It is evident that the image of Sakhalin cannot be constructed without considering its ties to the mainland and historical milestones associated with Japan. Many key images linked to the island have their origins in its connection to the mainland. These include exile, frontierism, and natural resources.

The exile of Tsarist times and the Soviet Gulag camps represent the expulsion of prisoners from the mainland, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, their use as labor force for the development of natural resources benefiting the country. The renowned Russian writer Anton Chekhov, often referred to, in contemporary terminology, as a “genius of place” for Sakhalin, is inseparably linked to the island and exile. He was among the first to create the image of the Island-on-the-Edge in Russian culture.

The image of the Frontier Island also emerges from Russia’s interactions with the outside world, primarily with Japan during World War II. The relevance of natural resources and relatively untouched nature to Sakhalin’s image at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries is genetically connected to the country’s economic prospects and demand for these resources as a whole.

The only authentic component of Sakhalin’s image is its indigenous peoples and their mythology. The indigenous population has shaped a kind of “relict cultural landscape” that remains alive today through ancient sanctuaries, fishing grounds, legends, and is visualized in contemporary documentary and feature films. Although the Ainu no longer inhabit the island, they persist in collective memory, photographs of early explorers, and museum exhibitions, forming the basis for visual narratives in documentary films as well.

The semantic range of visual content about Sakhalin is continually expanding, with life narratives shared by ordinary people forming vernacular discourses, in which the once rigid symbolism fades away, allowing everyday life and a genuine appreciation for the homeland to emerge. Contemporary visual images, on the one hand, reflect and, on the other hand, recreate the image of Sakhalin in Russian culture. They bring it “closer” to the mainland, virtually reducing the internal distances within the cultural landscape, and stimulating travel and tourist flows.

6.3 Significance of the Study

This study sheds light on the modern history of Sakhalin depicted in photography and cinema (encompassing both artistic and documentary films, as well as grassroots content on platforms like YouTube and RuTube). Despite the historical and stylistic diversity of these elements, they collectively construct a cohesive narrative where each part intricately connects; the past consistently resurfaces in the context of the present, while modernity imbues fresh significances into the legacies of past epochs. This depiction is not standalone but an integral fragment of Russia’s geocultural sphere, serving as a pivotal aspect of its cultural self-identification and a cornerstone of its geopolitical worldview. The scholarly examination of Sakhalin’s portrayal leads us to grasp the specifics and patterns within this geocultural landscape.

Endnotes

References

- Bukchin, S. V. (2010). Vlas Doroshevich: Sud’ba fel’etonista [Vlas Doroshevich: The fate of the feuilletonist]. Moscow: Agraf.

- Chekhov, A. (1967). The island: A journey to Sakhalin. Washington Square.

- Corrado, S. M. (2010). The “end of the earth”: Sakhalin Island in the Russian imperial imagination, 1849–1906 [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Danilenko, L. V., & Povolkovich, F. A. (2015). Gorod-prizrak kak ob”ekt turistskogo interesa (goroda-prizraki Sakhalinskoy oblasti) [Ghost town as an object of tourist interest (ghost towns of the Sakhalin area)]. Rossiyskie Regiony: Vzglyad v Budushchee, 2 (3), 81–90. Retrieved February 7, 2024, from https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/gorod-prizrak-kak-obekt-turistskogo-interesa-goroda-prizraki-sahalinskoy-oblasti

- Denisova, I. M. (2009). Obrazy ostrova i kamnya v russkoy fol’klornoy traditsii: Poiski semanticheskikh istokov [Images of island and stone in the Russian folklore tradition: In search of semantic origins]. Etnograficeskoe Obozrenie, (5), 76–90.

- Din, Y. I. (2014). Koreytsy Sakhalina v poiskakh identichnosti (1945-1989 gg.) [Sakhalin Koreans in search of their identity (1945–1989)]. Vestnik RGGU. Seriya: Literaturovedenie. Yazykoznanie. Kul’turologiya, (6), 237–249. https://elibrary.ru/shmugl

- Din, Y. I. (2021). “Repatriatsiya” aynov Yuzhnogo Sakhalina posle Vtoroy mirovoy voyny [“Repatriation” of Ainu of South Sakhalin after the Second World War]. Rossiya i ATR, (4), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.24412/1026-8804-2021-4-84-96, https://elibrary.ru/nlbdgb

- Doroshevich, V. M., & Gentes, A. A. (Trans.). (2009). Russia’s penal colony in the Far East: A translation of Vlas Doroshevich’s “Sakhalin”. Anthem Press.

- Epstein, S. J. (1998). A Forgotten People: The Sakhalin Koreans, by Dai-Sil Kim Gibson, 1995. Western Folklore, (57), 77–79. Retrieved February 7, 2024, from https://koreanstudies.com/ks/ksr/ksr99-05.htm

- Gentes, A. A. (2021). Russia’s Sakhalin Penal Colony, 1849–1917: Imperialism and Exile. Routledge, 2021.

- Golovnev, I. A. (2020). Kinodokument kak istoricheskiy istochnik (na materialakh sovetskikh dokumental’nykh fil’mov o Sakhaline) [Film document as a historical source (based on Soviet documentaries about Sakhalin)]. In L. N. Mazur (Ed.), Dokumental’noe nasledie i istoricheskaya nauka [Documentary heritage and historical science] (pp. 111–115). Yekaterinburg: Ural Federal University. Retrieved February 7, 2024, from https://elar.urfu.ru/handle/10995/92891

- Golovnev, I. A. (2020). Kinodokumenty po etnografii aynov v kollektsiyakh muzeev i arkhivov Sakhalina [Documentary films on the ethnic studies of the Ainu people in the collections of Sakhalin museums and archives]. Vestnik Rossiyskogo Fonda Fundamental’nykh Issledovaniy: Gumanitarnye i Obshchestvennye Nauki, (4), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.22204/2587-8956-2020-101-04-24-33, https://elibrary.ru/luqwvw

- Golovnev, I. A. (2023). Dal’niy Vostok v kinodokumentakh A.Z. Kusheshvili [Soviet Far East in the films of Alexey Kusheshvili]. Gumanitarnye Issledovaniya v Vostochnoy Sibiri i na Dal’nem Vostoke, (3), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.24866/1997-2857/2023-3/94-103

- Golovnev, I., & Golovneva, E. (2021). Obrazy Dal’nego Vostoka v vizual’nykh dokumentakh rubezha XIX–XX vv. [Images of the Far East in visual documents of the turn of the 19th–20th centuries]. Saint Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriya.

- Golovneva, E. V., & Golovnev, I. A. (2020). Sakhalin Chekhova: fotograficheskaya fiksatsiya ostrova [Chekhov’s Sakhalin: Photographic fixation of the island]. Praxema, (1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.23951/2312-7899-2020-1-76-92

- Katanyan, V. (2002). Prikosnovenie k idolam [Touching idols]. Moscow: Zakharov.

- Kravchenko, K. A. (2022). Regional’noe kino Rossii: K probleme opredeleniya [Russian regional cinema: The problem of definition]. Paradigma: Filosofsko-Kul’turologicheskiy Al’manakh, (36), 139–149. Retrieved February 7, 2024, from https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/regionalnoe-kino-rossii-k-probleme-opredeleniya. https://elibrary.ru/oezurq

- Kropotkin, P. (1906). V russkikh i frantsuzskikh tyur’makh [In Russian and French Prisons]. Saint Petersburg: Znanie Publishing House. English version retrieved February 7, 2024, from https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/petr-kropotkin-in-russian-and-french-prisons

- Lavrenova, O. A. (2020). “Holy islands” in the cultural landscape of Russia. Lexia. Rivista di semiotica / Journal of Semiotics, (35-36), 353–370. http://dx.doi.org/10.4399/978882553853319.

- Lotman, Yu. M. (1994). Besedy o russkoy kul’ture: Byt i traditsii russkogo dvoryanstva (XVIII—nachalo XIX veka) [Conversations about Russian culture: Life and traditions of the Russian nobility (XVIII—early XIX century)]. Saint Petersburg: Iskusstvo.

- Lotman, Yu. M., & Shukman, A. (Trans.). (1990). Universe of the mind: A semiotic theory of culture. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis. Retrieved XX July, 2024, from https://monoskop.org/images/5/5e/Lotman_Yuri_M_Universe_of_the_Mind_A_Semiotic_Theory_of_Culture_1990.pdf

- Ministry of Culture and Archiving of the Sakhalin Region. (2016, September 30). Vystavka o znakovykh vekhakh v istorii sakhalinskogo kino otkrylas’ v istoricheskom arkhive [An exhibition on significant milestones in the history of Sakhalin cinema opened in the Historical Archive]. Retrieved February 7, 2024, from https://culture.admsakhalin.ru/news/post/2313/

- Piłsudski, B. (1912). Materials for study of the Ainu language and folklore. Cracow.

- Piłsudski, B. (1915). Na medvezh’em prazdnike aynov o. Sakhalina [At the Bear Festival of the Sakhalin Ainu]. Petrograd: V. D. Smirnov’s Publishing House.

- Piłsudski, B. (2017). Gilyaki i ikh pesni [The Gilaks and their songs]. In V. V. Shcheglov (Ed.), Etnograficheskie zapiski Sakhalinskogo oblastnogo kraevedcheskogo muzeya [Ethnographic notes of the Sakhalin Regional Museum of Local Lore] (Vol. 1, pp. 3–13). Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk.

- Ryazanov, E.A. (1983). Nepodvedennye itogi [Unsummarized conclusions]. Moscow: Iskusstvo.

- Sarkisova, O. (2015). Taming the frontier: Aleksandr Litvinov’s expedition films and representations of indigenous minorities in the Far East. Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema, 9 (1), 2–23.

- Terebikhin, N. M. (2020). Metafizika Severa [Metaphysics of the North]. Arkhangelsk.

- The New York Public Library Digital Collections. (n.d.) Sakhalin, the island of exile: Photograph collection of the Russian island penal colony during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Retrieved February 7, 2024, from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/sakhalin-the-island-of-exile-photograph-collection-of-the-russian-island-penal#/?tab=about