Maritime Culture of Bantik Ethnic Group From North Sulawesi, Indonesia

Abstract

Indonesia is well known as an archipelagic country on the equator with a huge population and diverse cultures where up to 70% of its area constitutes a maritime continent. This study investigates the maritime culture of Indonesia, a nation comprising 16,771 islands, 1,331 ethnicities, and 4,735 coastal villages, with a particular focus on the Bantik Ethnic Group in North Sulawesi Province. The primary objective of this study is to identify and document maritime cultural elements and local knowledge of the Bantik group, alongside assessing their past and current status. Employing a descriptive analysis through thematic coding of data collected via focus group discussions (FGD), in-depth interviews, field observations, and document analysis, the study reveals that the Bantik has a rich maritime culture rooted in agrarian coastal life and historical ocean connections. However, urbanization poses significant threats to their traditional practices and language, while rural Bantik communities remain largely unaffected by these changes. This research underscores the importance of preserving the Bantik's intrinsic cultural values amidst modern challenges.

Keywords

Bantik ethnic group, Maritime culture, Environmental change, Urbanization

Introduction

Humans and the environment have always interacted in a dynamic relationship where they influence, synergize, complement, and sometimes negate each other. The environment provides the physical landscape for human habitation, offering essential materials for survival as well as spiritual and aesthetic experiences (Costanza et al. 2017; Haines-Young & Potschin 2012; TEEB 2010). Culture acts as a mediator between humans and their environment, meaning that cultural practices, lifestyles, and norms can be significantly influenced by changes in the surrounding ecosystem. Culture encompasses behaviors, knowledge, ideas, beliefs, and norms (Birukou et al. 2013). Historical examples, such as the Ancient Egyptian Kingdom, illustrate this relationship: climate variability around 5000 cal BP led to a transition from wet to dry conditions, which had profoundly impacted on the social and cultural systems of the Egyptian people (Brooks 2006; Welc and Marks 2014). In modern times, the construction of a bridge between Madura Island and Java Island in Indonesia has altered the cultural identity of Madura's inhabitants (Hong et al. 2022). Additionally, urban migration can significantly disrupt local cultural practices by introducing new cultural influences and lifestyles that may overshadow traditional customs. As people move from rural to urban areas, they often adopt the prevailing urban culture, leading to a gradual erosion or complete elimination of their indigenous practices and traditions. This cultural shift can result in the loss of unique cultural identities and heritage, as well as the diminishing use of native languages and traditional knowledge (Weir et al. 2017).

As a vast archipelago, Indonesia offers a fascinating study of coastal communities and their cultures. The country comprises 16,771 islands, 1,331 ethnic groups, and boasts an 81,000 km-long coastline (BIG 2023). Additionally, Indonesia has 4,735 coastal villages that are rich in maritime cultures (BIG 2022). These cultures are expressed through various rituals, advanced fishing technologies such as boats and gear, and marine management institutions, including folklore and oral traditions (Yuliaty et al. 2019). One notable group within this maritime mosaic is the Bajo, known as seafaring nomads. To reinforce its national identity, Indonesia is committed to cultural development, focusing on revitalizing and actualizing cultural values and local wisdom, as well as promoting maritime culture and literature, as outlined in Presidential Regulation No. 18/2020.

The Bantik are considered one of the sub-ethnic Minahasa groups residing on the northeastern coast of Sulawesi Island. However, there is a debate regarding their classification, with some arguing that the Bantik, belongs to the Sangihe tribe due to the close similarities in their languages. Sneddon (1989; 1993) elaborates on this linguistic connection, suggesting that the Bantik language is closely related to the Sangiric language, both of which descend from Proto-Sangiric. Despite this intriguing linguistic relationship, scientific reports on the Bantik are scarce compared to those of other ethnic groups in Sulawesi, such as the Bugis and Minahasa. Notable contributions to the study of the Bantik language have been made by Sneddon (1989; 1993) and Utsumi (2011), who focused on its linguistic aspects.

Furthermore, some studies have focused on the spatial characteristics, development, and planning related to the local cultural heritage of the Bantik (Egam et al. 2015; Egam and Mishima 2014a; 2014b). These studies examine how the physical space and environment influence cultural preservation and development. However, research on the history and maritime cultural aspects of the Bantik tribe remains limited. Given that the Bantik traditionally lived in coastal areas, it is reasonable to assume that maritime elements would have significantly influenced their society, traditions, language, and local knowledge. This maritime influence likely shaped their way of life, from fishing practices to folklore and community rituals, underscoring the need for more comprehensive studies in these areas.

This study aims to identify and document the maritime elements present in the local knowledge and culture of the Bantik ethnic group, as well as to analyze their current status descriptively. By focusing on maritime elements, this research seeks to uncover how the Bantik's coastal environment has influenced their cultural practices, traditions, and societal structures. This study represents the first effort to examine Bantik culture through a maritime lens, offering new insights into the interplay between the Bantik people and their coastal surroundings. Furthermore, this research aligns with the goals outlined in the Medium-Term Development Plan of the Republic of Indonesia 2020-2024 (Presidential Regulation No. 18/2020), emphasizing the importance of cultural preservation and the revitalization of local wisdom, particularly concerning maritime heritage.

Method

The philosophy underlying the traditional practices of the Bantik ethnicity was also examined through the lens of constructivism. This theoretical approach helps to illustrate how the customs, habits, and rituals of the Bantik people are shaped and constructed by their community and belief systems. By using constructivism, the study supports the notion that these cultural practices are not static but are continuously influenced and redefined by the collective experiences and values of the Bantik ethnicity. This perspective provides a deeper understanding of how the Bantik's traditions evolve and maintain their relevance within their cultural context.

Study Site

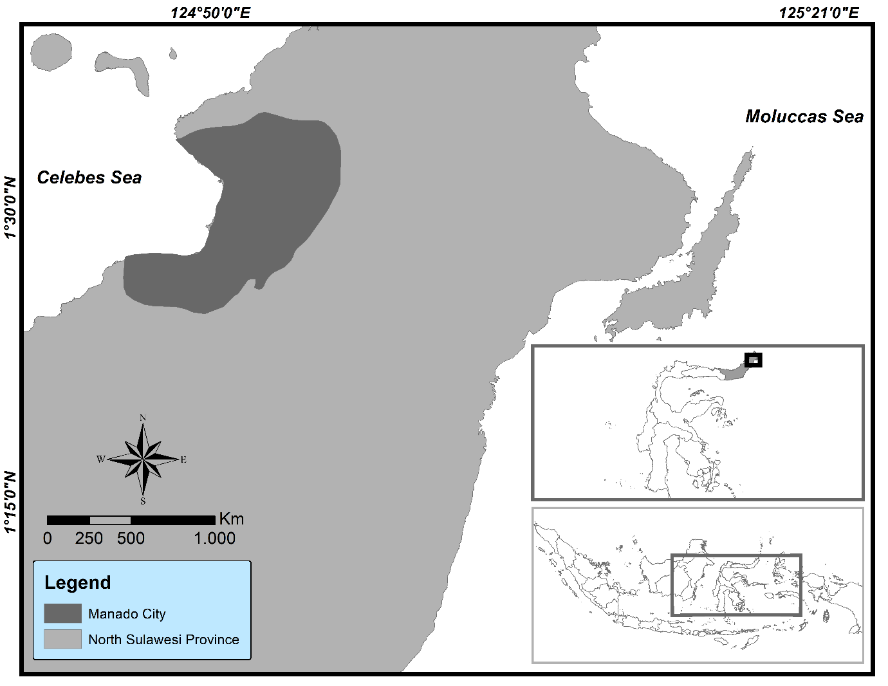

Initially, eleven villages in North Sulawesi were inhabited by the Bantik people: Bengkol, Buha, Singkil, Bailang, Molas, Meras, Malalayang, Kalasey, the Tanamon area (North Tanamon and Central Tanamon villages), Sumoit (also known as Samoiti), and Talawaan. The first ten villages are located in coastal areas, while the last one is inland. Most of these villages fall under the jurisdiction of Manado City, the capital of the province (Figure 1). In contrast, Tanamon belongs to the South Minahasa Regency, Kalasey to the Minahasa Regency, and Talawaan to the North Minahasa Regency. Among these, four villages were the focus of this research: Malalayang, Tanamon, Talawaan, and Molas. Malalayang is situated in the southern part of the city near the business district, which has led to landscape changes due to urban development. Compared to Malalayang, Molas is in the northern part and is a less populated, growing area (BPS 2023a; 2023b). This area has become famous for its diving centers due to its proximity to Bunaken Island, one of the world's premier diving spots. Talawaan, also known as Talawaan Bantik, is a rural inland village. Tanamon, located in the southern part of the province, is also rural. Besides the Minahasa tribe, the Bantik people here are influenced by the Bolaang Mongondow people.

Data collection and analysis

We employed a qualitative research design to gather detailed information on the language, culture, and traditional ceremonies of the Bantik people, particularly those with a maritime cultural perspective. The data collection methods included focus group discussions (FGD), in-depth interviews, field observations, and document analysis. To interpret the findings from the empirical data and literature review, we utilized a descriptive analysis approach through thematic coding, adapted from the model proposed by Miles and Huberman (2014). This approach allowed us to systematically categorize and analyze the data, uncovering patterns and themes that comprehensively understand of the Bantik's maritime cultural elements.

The focus group discussion (FGD) was conducted once in May 2023, with fifteen Bantik individuals invited to participate based on recommendations from traditional leaders. These participants represented various Bantik villages, primarily from Manado City, and came from diverse backgrounds, including heads of traditional institutions, priests, fishermen, government officials, and retired employees. Among the participants was one woman, notable for her previous career as a swimming athlete. Additionally, a linguistic lecturer was invited to serve as a resource person and presented their most recent research on the community's use of the Bantik language, sharing valuable insights despite the unpublished data. This diverse group provided a rich array of perspectives and experiences, contributing significantly to the depth and breadth of the discussion.

During the interviews, participants were asked a series of open-ended questions designed to elicit detailed information about their knowledge of the sea, including terms or language used to describe marine objects or events, and coastal areas. The scope of the questions also extended to documenting Bantik history and cultural events. Interviewees were selected based on specific criteria: they had to have lived in the area for over 30 years, be over 50 years old, and be fluent or at least passive speakers of the Bantik language. Among the interviewees was a particularly notable participant, a man aged 90 years old, whose extensive experience and knowledge provided invaluable insights. Additionally, another interviewee was a leader of The Bantik Indigenous Community Alliance and the nephew of Wolter Mongisidi, a national hero from the Bantik community. This selection ensured the interviews captured a rich and authentic representation of the Bantik people's maritime knowledge and cultural heritage.

The observation technique was employed to closely examine the environment and social dynamics at the study sites. This involved visiting four specific villages: the Malalayang area, Molas, the Tanamon area, and Talawaan. During these visits, detailed observations were made regarding the physical landscape, community interactions, and daily activities of the residents. This hands-on approach allowed for an in-depth understanding of how the environment influences social behaviors and cultural practices within these Bantik communities. The collected observational data provided crucial context and complemented the information gathered through other research methods.

Results and Discussion

The Bantik People

The origins of the Bantik people remain ambiguous and are shrouded in mystery. Various legends offer differing accounts of their beginnings, distinguishing them from other local communities, such as the Minahasan people in the northern part of Sulawesi Island. According to the elders, the Bantik were traditionally a nomadic group. They could to relocate en masse to new territories or split into smaller groups for migration. Their movements were not confined to land; they also ventured across the sea to different areas during their journeys. This nomadic lifestyle contributed to their rich cultural tapestry and the unique maritime elements integral to their identity.

An old story narrates that the ancestor of the Bantik people was a man whose mother was from heaven and whose father was from earth (Schmidtmuller 1852). Graafland detailed this tale in 1869 (Sumolang 2010). However, such stories are common throughout Indonesia, similar to the Javanese legend of Jaka Tarub and Nawang Wulan, the Minahasan tales of Mamanua and Lumaluindung, or the Tolaki myth of Oheo and Anawaingguluri from Southeast Sulawesi (Rohim 2013). In the Bantik version, Utahagi, a daughter of Toar and Lumimuut, descended from heaven with her sisters to bathe in Mandolang. She married Kasimbaha and bore a child named Tambaga. Due to Kasimbaha violating a prohibition by pulling out a strand of white hair from Utahagi's head, she returned to heaven. After a great effort, Kasimbaha and Tambaga ascended to heaven to reunite with Utahagi. Kasimbaha stayed in heaven, but Tambaga returned to earth, married, and had children, whom the Bantik people consider their ancestors. Through this story, the Bantik people establish their genealogy, aligning themselves as descendants of the gods, akin to other Minahasan groups (Sumolang 2010). Graafland also mentions that in ancient times, the Bantik people lived in Malalayang (Minanga), characterized by an Alifuru house system that was pagan, chaotic, savage, and rude.

Another story is closely related to the marine world (Sumolang 2010). The ancestors of the Bantik people, known as the Pondaigi family, were a group of adventurers and nomads in the land of Malesung. They initially inhabited the Wulur Mahatus and Pontak mountain areas (Pontaka) in the southern part of Minahasa. Over time, they dispersed into seven groups (Na Tahede Su Pitu Tindalren). Despite their dispersal, these groups maintained contact, often visiting each other, and some even reunited to form larger groups. One notable large group from Mandolrang, led by Opo Gohung, joined other Bantik groups led by Opo Mananegehelrangi in the Lonu settlement in the land of Buol-Tolitoli after the sinking of Panimbulran Island (The Sunken Island) in Talaud. This unified group produced several generations of kingdoms. One prominent king, Sulru Bentuku Si Damopolri, also known as Madika Bondik Lro Minu, reigned over a period when the group dispersed once more into nine groups (Na Tahede Su Siou Tindalren). Four of these nine groups from the original Lonu settlement (now Buol District) eventually returned to Malesung Land and the Porodisa Islands (Sangihe). Sangihe Island, formerly known as Tampunganglawo Land, was connected to a series of small islands, including Lipaeng, Kawaluso, Matutuang, Memanu, Komboleng, Kawio, Marore, Marulung (Balut), and Sahenganeng (Saranggani) at the northernmost tip of the northwest. The Bantik tribe's former settlement, Kaluwulang, was situated between Napong Ehise (white shoal) and Marulung Island. However, due to the sinking of the northwestern part, the Bantik tribe temporarily fled to the Talaud mainland and then migrated to the west coast along the coast of North Sulawesi. Some members moved to South Mindanao, while those physically weaker remained in Talaud.

Another argument explains why the Bantik people settled in coastal areas, as recounted in one of Minahasa's historical accounts involving the Watu Pinabetengan (Pinabetengan Stone). This stone holds significant cultural importance as the gathering place where the ancestral leaders of the Minahasa tribes would convene to deliberate and resolve issues. According to the story, leaders of all sub-tribes, including the Bantik, were summoned to discuss the division of territories. However, the Bantik people arrived late to the meeting because they were preoccupied with chasing away pirates from the sea. As a result of their tardiness, they were allocated the coastal areas for their territory. This narrative highlights the Bantik's historical role in maritime defense and their longstanding connection to the coastal regions they inhabit.

Maritime Context in Bantik Culture

Despite the Bantik people's history, which intertwines land and sea, their language and practices reflect a deep connection to marine customs. For instance, the Bantik language includes the word matambung, which signifies their ancestor as a conqueror of the sea. This perspective is heavily influenced by their origin stories and the conditions of the coastal villages they inhabit. Historically, the sea was viewed as a battlefield, and the coastline served as a crucial defense area fortified with bamboo fences. This martial perspective on the sea underscores the Bantik's identity as guardians of the ocean. Their maritime heritage is not only a testament to their ancestral valor but also a reflection of their enduring role in protecting and navigating the coastal waters where they have lived for generations.

Moreover, valuable maritime knowledge can still be gleaned from the current Bantik community. This knowledge can be categorized into several distinct areas: marine management systems, knowledge of nature as well as natural product usage, and taboos. The marine management system encompasses the hierarchical structure of rulers and the organized approach to fishing and conservation efforts. It includes understanding the territorial divisions and the rules governing marine resource use, ensuring sustainable practices that have been passed down through generations. Natural product usage refers to the ways in which the Bantik utilize marine resources for various purposes, such as food, medicine, and tools. This includes their expertise in harvesting and processing marine plants and animals, showcasing their deep connection and sustainable practices with the natural environment. Taboos represent the cultural and spiritual beliefs that govern what can and cannot be done in the marine context. These taboos are rooted in the Bantik's ancestral traditions and are essential for maintaining harmony between the community and their marine environment, reflecting a deep respect for the natural world and its resources.

The Bantik people have distinct terms for different parts of the ocean, referring to them as sulaudo and sulaudo bidu. The term sulaudo translates to the ocean and specifically describes the coastal region, extending from the shoreline outwards but covering a distance of less than one kilometer, typically up to the edge of the coral reef. On the other hand, sulaudo bidu, which means blue ocean, denotes the vast expanse of the ocean that lies beyond the coastal region and reaches into the open sea.

In Bantik culture, both sulaudo and sulaudo bidu are believed to be governed by deities. The God who rules the ocean is known as Tangihiang, while Makabarang, rules the land. Traditionally, these divine names could not be spoken freely; one had to obtain permission before mentioning them. The supreme deity, often called Mabuduata, signifies the Almighty of the universe. This term, Mabuduata, continues to be used in contemporary times, especially in songs (such as Yopo Mabuduata) and prayers during formal and informal gatherings. This practice is particularly prevalent among the Bantik people, who are predominantly Christian. For instance, a prayer might include the use of Mabuduata in the following manner (Lumempouw 2016):

“Oh… mabuduata bampung naka bereng rangi botimbow tana?”

'Oh God, the ruler and creator of the heavens above, the earth and beneath, the earth's floor.'

The tradition of thanksgiving and asking for protection from the almighty also exists in a ritual called gocefa. This ritual is believed to predate the Bantik people's embrace of Christianity. Before the ritual begins, participants gather offerings of agricultural products such as coconuts, corn, sweet potatoes, and bananas, placing them into a small bamboo raft. The ceremony is led by a spiritual leader who prays and sings sacrificial songs alongside the elders and Kabasaran Bantik dancers. As evening approaches, a torch is lit, placed on the raft, and set adrift at sea while the surrounding lights are extinguished. Despite its rich cultural significance, this ritual has not garnered much attention in recent times and is rarely performed.

Mapane kurabe translates to "to guard the ocean." According to local legends, the Bantik people settled along the coast because they were tasked with protecting the Minahasa region from pirates originating from Mindanao and other areas. Renowned for their combat skills, the Bantiks are celebrated as battlefield heroes. Historically, they served as troops for the Bolaang Mongondow kingdom, defending land and sea from invaders. The heroism of the Bantik people is also immortalized in the folklore of Matansing. As a child, Matansing was cared for by supernatural spirits. Upon reaching adulthood, he returned to his parents and emerged as an extraordinary warrior. One of the most famous tales recounts Matansing single-handedly defeating the royal troops of Banten by killing their king. At the end of his life, Matansing ascended to heaven, becoming a deity.

Matumbang refers to the coastal livelihood of the Bantik people, who eat predominantly fish and other seafood. In practice known as sulaudo bidu, the Bantik use a sekai (boat) and sometimes spend one or two days in a haki (temporal refuge). A haki is not only a temporary shelter but also serves as a fish aggregating device (FAD). Another method for catching fish involves trap fishing gear, which comes in two types: kore and soloso (floating net cage). The kore is positioned in coastal areas or river mouths, while the soloso is set up on reefs. Field observations reveal that the fishing tools used by the Bantik people are identical to those employed by the fishermen from the Sangihe tribe. They also share the same terminology for fishing gear, such as rarape or darape, which means gillnet. This commonality in tools and terms underscores the cultural and practical connections between these coastal communities.

Hahangen refers to the practice of protecting marine resources, which involves releasing small fish back into the ocean to ensure their populations can thrive and sustain the ecosystem. Unfortunately, the concept of hahangen has not been fully understood or embraced recently, particularly among the younger generation. This decline in practice may be attributed to changes in the village landscape, shifts in livelihoods, and evolving social interactions, which have all contributed to a disconnect from traditional practices. Another protective measure in place is the prohibition against catching sharks (gorango). This rule could be translated to safeguard the species and maintain the balance of the marine environment. Together, these practices reflect a long-standing cultural emphasis on conservation, although their continued effectiveness depends on the community's adherence and understanding.

The Bantiks are knowledgeable about various forms of marine and coastal life. Like other coastal communities, they use these biota for food, medicine, and other essential purposes. For instance, in Tanamon village, the leaves of the taledei or bayhops plant (Ipomea pes-caprae) are used to treat stomachaches and are also used in saunas for women after childbirth. Another plant, the Ficus tree, known locally as tagalolo, is used to treat fevers. This tree has broader applications in traditional medicine and cuisine in places such as China and Papua New Guinea (Deli et al. 2022; Lansky et al. 2008). Additionally, the Bantik people use mangrove (pahapa) bark to soak fishing nets for about a week to strengthen them. This practice demonstrates their deep understanding of and reliance on coastal resources for various aspects of daily life.

The maritime culture of the Bantik people is also reflected in their traditional song and dance known as Mahambak. This dance is divided into two types: traditional Mahambak and Mahambak imbasan. The traditional Mahambak dance follows a more conventional and historical style, while the Mahambak imbasan features more varied and dynamic dance movements, showcasing an evolution in the performance. Both forms of the dance are typically accompanied by songs and the musical instrument tambor, a type of drum that sets the rhythm and enhances the cultural expression. Among the many Mahambak songs, one particular lyric stands out as it narrates the life and experiences at sea, encapsulating the maritime heritage and the close relationship the Bantik people have with the ocean. This lyric serves as a poetic and melodic representation of their daily lives, challenges, and the deep-seated respect they hold for the sea:

Sakaeng mabihing bihing

Sakaeng mabihing bihing

Tasimasiko ɾampange tuanditungkoko

Babaetete muntia mbanti’

Kakadea kamasi koken

Uduman takauduman

Kamadaɾung ɾaodo bae e be (sung by Ester Damo)

According to the participants' description, this song is commonly performed in the traditional Mahambak dance. The lyrics vividly portray the experience of sailing in a boat, which rocks and tilts with the movement of the waves. This imagery captures the daily experiences and struggles faced by those who depend on the sea. Additionally, the song speaks of a Bantik treasure, a pearl lying at the bottom of the sea, symbolizing hidden wealth and mystery. This pearl represents not just material value but also the cultural and historical richness of the Bantik people. Despite the allure of this treasure, the lyrics underscore the unfathomable depth of the sea, highlighting the significant challenges and dangers inherent in maritime life. Through this song, the Bantik convey their respect for the sea's power and the resilience required to navigate its unpredictability.

The Bantik people observe certain taboos and prohibitions rooted in their cultural traditions and beliefs. One significant taboo is the prohibition against going to the sea when a person in the village has passed away. This ban is a way for the community to show respect for the deceased and to support the grieving family. It reflects the community’s collective mourning and commitment to being present and offering help to the bereaved family during their sorrow. However, there is an exception to this rule: if someone is already on a boat when they learn of the death, they must continue their journey and are forbidden from turning back. This specific aspect of the taboo emphasizes the importance of moving forward once a journey has begun, perhaps symbolizing respect for the sea and its own set of rules. In modern times, this particular taboo is not as strictly observed as it once was, indicating a shift in cultural practices and possibly the influence of changing societal norms. Another taboo among the Bantik involves sighting presumably sailing snails (nautilus shells). When someone encounters one of these snails, they must immediately return home to avoid any potential danger or bad luck. This belief highlights the Bantik's respect for natural signs and omens, suggesting that these encounters are seen as warnings that must be heeded to ensure personal safety. These taboos illustrate the Bantik people's deep connection to their environment and their belief in the importance of adhering to traditional practices for the well-being of the community.

What is the role of Bantik women in maritime culture? Observations have noted the absence of female fishermen among the Bantik people. The role of women appears to be more supportive and domestic rather than directly involved in fishing activities. This pattern has been documented in existing literature, which describes Bantik women typically staying on the coastal shorelines. There, they engage in culinary activities such as operating stalls that sell snacks, like fried bananas, or running small shops along the coast, particularly in the Malalayang district (Lamadirisi 2017). Based on these observations, it was initially assumed that there might be a cultural or traditional prohibition preventing women from participating in maritime activities, similar to prohibitions observed among Sangihe women. However, further verification with female participants revealed that this assumption was incorrect. Women reported that they are not restricted from fishing activities and often participate in them during their leisure time with friends. This participation, however, does not constitute their primary occupation. Instead, it is a supplementary activity to enhance their household food supply. The fish they catch are typically cooked and consumed with their families, indicating that while women engage in fishing, it is more for personal and family sustenance than a professional endeavor. Thus, it can be inferred that while Bantik women may not be professional fishermen, they do contribute to their maritime culture through both support roles on the shore and occasional participation in fishing for their families.

Agricultural versus Maritime Society

The Bantik people have a diverse range of livelihoods beyond just relying on the ocean. They are engaged in agriculture, cultivating various crops such as rice, coconut, clove, corn, vegetables, and fruit trees. The farming practices and land tenure systems among the Bantik were significantly influenced by the Dutch during the early 19th century up until the early 2000s, farming was the primary means of livelihood for the Bantik community in Molas, surpassing both fishing and hunting in importance (Walker et al. 2000). In the village of Tanamon, farmers outnumber fishermen, with only about 25% of the population engaged in fishing. This trend reflects a broader pattern within Bantik society. An interviewee from Malalayang village explained that when the population was smaller, and there was abundant land available, the Bantik people primarily focused on farming. Fishing was considered a supplementary activity, undertaken particularly during periods of calm and pleasant weather. Interestingly, there is one Bantik village, Talawaan Bantik, where no fishing activities occur. This is due to its inland location, far from the coastal areas, making farming the sole livelihood option for its residents. While fishing plays a role in the Bantik's way of life, it is generally secondary to agriculture.

In general, Bantik people living in rural areas engage more in farming than fishing. This trend is due to the availability of land for agricultural activities, which has traditionally been a primary source of livelihood for the rural Bantik communities. In contrast, Bantik people in urban areas experience a more diverse set of occupations due to the dynamic and shifting structure of urban communities. In cities, people have access to a broader range of job opportunities beyond farming and fishing, such as trade, services, and other forms of employment. Despite this diversity, the ocean remains essential to the Bantik community’s cultural and economic life. The deep connection between land and sea in Bantik culture is evident in their culinary practices and traditions. This relationship is highlighted by a focus group discussion (FGD) participant who explained: "When we harvest paddy (mei), we will go fishing to eat fish (kina) with the new rice (kang)." This practice illustrates the harmonious interaction between farming and fishing, showing how both land-based and sea-based resources are integral to their way of life and cultural identity.

Environmental Changes and Urban Development

The coastal areas of Manado, home to the Bantik people, have undergone significant changes over the past 30 years. Up until the late 1980s, the coastal region of Manado city featured natural shorelines dominated by sandy beaches (Rondonuwu et al. 2023). While some concrete buildings, particularly houses, had been erected along the coast, a stretch of sandy flat land still existed behind these neighborhoods. This area was used for various fishing-related activities, such as mooring boats, drying fishing nets, and providing a play space for children. However, a transformation began at the end of the 1980s with reclamation projects, followed by road construction in the early 1990s. These developments marked the beginning of a significant shift in the landscape. Gradually, commercial structures started to emerge on the reclaimed land, including shop buildings, shopping malls, restaurants, and hotels for tourism purposes combined with the climate variability that impacts the water resources in the region (Solihuddin et al. 2024), especially with several cases occurring in a small island (Kepel et al. 2023; Kompas 2023; Liputan6 2023). This urbanization altered the coastal environment, replacing the natural sandy beaches with man-made infrastructure. As a result, the coastal areas of Manado have evolved from natural, community-oriented spaces into bustling urban zones with various commercial and recreational facilities.

Malalayang, located just a few kilometers from the city center of Manado, where rapid changes happen, has also experienced significant shifting due to urban development. The traditional spaces used by the Bantik community for daily activities were encroached upon by these new developments. The settlement patterns of the Bantik people in this area have been altered, and there has been a noticeable decline in cultural activities, as identified by Egam & Nishima (2014a). This shift can be attributed to the increasing urbanization and modernization of the region. Additionally, the development in Malalayang has had a profound impact, and the area's growth and modernization have contributed to a decline in the Bantik population (Egam et al. 2015). This demographic change is likely due to factors such as migration, both into and out of the area, and possibly lower birth rates among the Bantik community. The economic landscape has also shifted, with traditional livelihoods like farming and fishing being increasingly supplemented or replaced by other forms of employment. The influx of commercial activities, new businesses, and modern infrastructure has led to changes in the economic activities available to the Bantik people, pushing some to seek new opportunities outside their traditional occupations.

The population of the Bantik people is difficult to determine accurately. As of 2011, the Bantik-speaking population was estimated to be around 10,000 (Utsumi 2011). However, this number has likely fluctuated due to changes in population demographics, particularly in areas like Malalayang village. For instance, in 2008, the Bantik population in Malalayang was recorded at 291 people, making up approximately 30% of the village's population. By 2014, this number had decreased to 250 people, or around 25% (Egam and Mishima 2014b). The trend of decline continued into 2020. In the Malalayang sub-district, which comprises nine villages, including Malalayang village, the Bantik people constituted only about 6% of the total population (Monoarfa et al. 2021). This decrease can be attributed to various factors, including intermarriage between Bantik individuals and people from other ethnic groups, such as Minahasa, Sangihe, and others across Indonesia. This intermarriage trend has further diluted the distinct Bantik population. Moreover, the Bantik have a traditional unspoken rule regarding marriage, which prohibits them from marrying within their community. This custom is still prevalent, especially in rural areas where strong kinship ties remain. As a result, the population has become more integrated with other ethnic groups over time. Additionally, changes in their living environment and economic pressures have compelled many Bantik people to sell their land and relocate. This phenomenon was already observed in Molas in the early 2000s when the area was proposed for tourism development (Walker et al. 2000). The increasing commercialization and development in their traditional areas have forced many Bantik to move to other regions, further contributing to the decline in their population in their original settlements. These factors combined have led to a significant reduction in the Bantik population over the years, and this trend is likely to continue unless there are substantial efforts to preserve their cultural and demographic identity.

Along with the declining native population, the number of local Bantik language speakers is also decreasing and is considered endangered. A local survey by Najoan et al. (in press com) found that in Manado and surrounding areas, the active speakers are aged 40 or older. The younger generation is usually considered passive speakers. However, few Bantik villages still speak Bantik in their daily life. In Tanamon, a village around 100 km from Manado, people, including the young generation, speak this tribal language daily. As a comment from the FGD participant from Molas, "Around 70% of Bantiks still speak the language in my village. Sometimes, we conduct a religious (Christian) service in Bantik." Generally, as a group of ethnicities, the language is still used actively in cultural events held once a year, at family gatherings, or other ceremonies such as funerals.

Bantik Community Strengths

Despite the challenges facing the Bantik community, they possess several strengths rooted in their cultural values and traditions. The Bantik community adheres to three core values: Hintakinang, Hintalunang, and Hinggirondang. Hintakinang emphasizes unity and mutual support. It represents the idea that the Bantik people are of one heart, working together and supporting each other in good deeds. This sense of solidarity helps the community stay resilient in adversity. Hintalunang focuses on the importance of helping one another. This value underscores the belief in assisting others, with the understanding that such actions have significance both in the present and the hereafter. It encourages a sense of duty and responsibility within the community to provide aid and support whenever needed. Hinggirondang embodies compassion and empathy. It highlights the importance of showing kindness and care to others. This value is especially evident during significant community events such as weddings and funerals. For instance, during funerals, particularly those of elders, traditional practices are observed, and the Bantik language is used in a ritual known as mabenu. This practice not only honors the deceased but also reinforces the community’s cultural heritage. Moreover, at the end of speeches during these occasions, a phrase is often recited: “Mangudang gudang bo mapia paname" which translates to "live long and prosperous." This phrase encapsulates the community's wish for longevity and prosperity, reflecting their optimistic outlook and mutual well-wishing. These values and traditions are integral to the Bantik community's identity and provide a source of strength and cohesion. They help the Bantik people maintain a strong sense of community and cultural continuity despite their various modern challenges.

The Bantik ethnic group proudly claims a national hero among their ranks: Robert Wolter Mongisidi. Recognized for his contributions and bravery, Mongisidi was posthumously honored as a national hero in 1973. His legacy is crucial in fostering unity and pride within the Bantik community. To honor his memory and celebrate their cultural heritage, the Bantik people hold an annual festival on September 5th, the anniversary of Mongisidi's death. This event serves multiple purposes: commemorating the hero’s sacrifice, reinforcing cultural values, and fostering unity among the Bantik people. The festival is a vibrant display of gratitude, joy, and community spirit, featuring various traditional songs and dances. Two prominent dances performed during the festival are the Mahambak dance and the war dance known as Kabasaran or Upasa. The Mahambak dance is a ceremonial dance symbolizing joy and thanksgiving. In contrast, the Kabasaran or Upasa dance is a traditional war dance that showcases bravery and strength, reflecting the community’s historical martial traditions. Additionally, the festival includes Bantik language song competitions, which preserve and promote the use of the Bantik language among younger generations. These competitions not only celebrate linguistic heritage but also encourage transmitting cultural knowledge and values. The annual festival dedicated to Robert Wolter Mongisidi is a vital cultural event for the Bantik people. It strengthens communal bonds, celebrates their rich heritage, and ensures that the legacy of their national hero and their cultural traditions are passed down through the generations.

Conclusion

Bantik is considered one of the sub-ethnic Minahasa groups living on the northeastern coast of Sulawesi Island, which is also close to the Sangihe tribe in terms of language. In general, Bantik people are agrarians who live in the coastline. Therefore, their culture and knowledge, to some extent, are closely related to maritime activities and the values relevant to Indonesia's policies as a big archipelago country. The Bantik group and the ocean's relationship cannot be separated from their history and ancestors. Their maritime knowledge could classified as marine management system (territory division and the rulers), knowledge of nature or environment, natural product usage, and taboo. Furthermore, the maritime aspect is also identified in song and dance, Mahambak.

Today, Bantik people in urban areas face community shifting due to environmental changes and urban development. The change could be observed in livelihood diversification, decreasing the Bantik native population and speakers. In contrast, the Bantik community in rural areas has not changed much. Despite the existing challenge, Bantik has strengths as a group. This strength must be sustainably maintained, so that Bantik’s intrinsic value as a group will be passed to generations.

Acknowledgments

This study was part of research titled "Ethno Maritime Strategy for Revitalizing Endangered Languages in Coastal Communities in North Sulawesi" in 2023, funded by the Research Organization of Political, Social, and Humanities Sciences (OR IPSH), National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), grant number DIPA-124.01.1.690502/2023. The authors thank Dr. Sjanne Walangarei for the support and all the informants and related parties for their contributions.

References

- BIG. (2022) ‘Affirmation of Indonesian island status’, https://sipulau.big.go.id/news/5 (Accessed: 1 July 2024)

- BIG. (2023) ‘One Map Policy’, Demnas. https://tanahair.indonesia.go.id/demnas/#/ (Accessed: 1 July 2024)

- Birukou, A., Blanzieri, E. et al. (2013) ‘A formal definition of culture’, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5574-1_1

- BPS. (2023a) ‘Bunaken Sub-district in figures 2023’ Central Bureau of Statistics, Manado City.

- BPS. (2023b) ‘Bunaken Sub-district in figures 2023’ Central Bureau of Statistics, Manado City.

- Brooks, N. (2006) ‘Cultural responses to aridity in the Middle Holocene and increased social complexity’, Quaternary International, 151(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2006.01.013

- Costanza, R. et al. (2017) ‘Twenty years of ecosystem services: How far have we come and how far do we still need to go?’, Ecosystem Services (Vol. 28). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.09.008

- Deli, J. et al. (2022) ‘Ficus septica exudate, a traditional medicine used in Papua New Guinea for treating infected cutaneous ulcers: in vitro evaluation and clinical efficacy assessment by cluster randomised trial. Phytomedicine, 99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154026

- Egam, P. P., & Mishima, N. (2014a) ‘Local cultural heritage sites and spatial planning for the Bantik Ethnic community in Indonesia’, Journal of Engineering, Project, and Production Management, 4(2), 60–73. https://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/local-cultural-heritage-sites-spatial-planning/docview/1541848218/se-2?accountid=10344

- Egam, P. P., & Mishima, N. (2014b) ’Spatial development of local Bantik Community in Malalayang, Indonesia’, Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.17265/1934-7359/2014.03.010

- Egam, P. P. et al. (2015) ‘Spatial characteristics of Bantik ethnic community in Indonesia’, Lowland Technology International, 17(2). https://doi.org/10.14247/lti.17.2_121

- Haines-Young, R., & Potschin, M. (2012) ‘The links between biodiversity, ecosystem services and human well-being’, Ecosystem Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511750458.007

- Hong, S. K., Kim, J. E., & Hong, S. J. (2022) ‘Changes and chaos in islands and seascapes: In perspective of climate, ecosystem and islandness’, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2022.11.1.01

- Kepel, T. L. et al. (2023) ‘Water security In Tunda Island, Banten Indonesia: Potency & threat’, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2023.12.1.01

- Kompas. (2023) ‘Warga Pulau Siladen Keluhkan Ketersediaan Air Bersih’, Regional Berita Daerah. https://www.kompas.tv/regional/403116/warga-pulau-siladen-keluhkan-ketersediaan-air-bersih (Accessed: 25 April 2024)

- Lamadirisi, M. (2017) ’Diversifikasi okupasi (studi sosiologis terhadap masyarakat di pesisir Pantai Malalayang, Kota Manado)’. Jurnal Civic Education: Media Kajian Pancasila Dan Kewarganegaraan, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.36412/ce.v1i2.504

- Lansky, E. P. et al. (2008) ‘Ficus spp. (fig): Ethnobotany and potential as anticancer and anti-inflammatory agents’, Journal of Ethnopharmacology (Vol. 119, Issue 2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2008.06.025

- Liputan6. (2023, October 13) ‘Kemarau panjang, sejumlah warga di Manado mulai kesulitan air bersih’. Regional Sulawesi. https://www.liputan6.com/regional/read/5421268/kemarau-panjang-sejumlah-warga-di-manado-mulai-kesulitan-air-bersih

- Lumempouw, F. (2016) ‘Penggunaan bahasa dalam proses pembuatan rumah tradisional sebagai pengungkap pola pikir kelompok Etnik Bantik di Minahasa (suatu kajian linguistik antropologi)’, Kajian Linguistik, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.35796/kaling.3.3.2016.12337

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, M. A. (2014) ’Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook’, In Zeitschrift fur Personalforschung (2nd Ecition, Issue 4). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Monoarfa, A. et al. (2021) ’Analisis kawasan strategis sosial budaya di Kota Manado’, SPASIAL.

- Rohim. (2013) ’Motif cerita bidadari: Sebuah telaah bandingan cerita rakyat Nusantara’, Ceudah, 3(1), 26–38. https://jurnalbba.kemdikbud.go.id/index.php/ceudah/article/view/23

- Rondonuwu, D. M. et al. (2023) ’Spatial pattern dynamics of sea and shoreline reclamation on the coast of Manado City, Indonesia’, Advances in Water Science, 34(2).

- Schmidtmuller. (1852) ‘Bantik’sche sage’, Zeitschrift Der Deutschen MorgenläNdischen Gesellschaft, 6(4), 536–538. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43359172

- Sneddon, J. N. (1989) ‘The North Sulawesi microgroups: In search of higher level connections’, http://sealang.net/archives/nusa/pdf/nusa-v31-p83-107.pdf

- Sneddon, J. N. (1993) ‘The drift towards final open syllables in Sulawesi Languages’, Oceanic Linguistics, 32(1). https://doi.org/10.2307/3623095

- Solihuddin, T. et al. (2024) ‘Assessment of a small island’s groundwater resilience under the pressure of anthropogenic and natural stresses on Tunda Island, Indonesia’, Environmental Earth Sciences, 83(12), 380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-024-11649-4

- Sumolang, S. (2010) ‘History of Bantik’, KURE, 5(5), 51–56.

- TEEB. (2010) ‘Mainstreaming the economics of nature: A synthesis of the approach, conclusions and recommendations of TEEB’, Environment.

- Utsumi, A. (2011) ‘Reduplication in the Bantik Language. In Asian and African Languages and Linguistics’ (Issue 6).

- Walker, J. L. et al. (2000) ‘Impacts during project anticipation in Molas, Indonesia: Implications for social impact assessment’, Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 20(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-9255(99)00040-2

- Weir, T. et al. (2017) ‘Social and cultural issues raised by climate change in Pacific Island countries: An overview’, Regional Environmental Change, 17(4). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-1012-5

- Welc, F., & Marks, L. (2014) ‘Climate change at the end of the Old Kingdom in Egypt around 4200BP: New geoarchaeological evidence’. Quaternary International, 324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2013.07.035

- Yuliaty, C. et al. (2019) ‘Sosial budaya masyarakat maritim’, Amafrad Press.